A Stepwise Monolayer Protocol for Kidney Organoid Differentiation: Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the stepwise monolayer protocol for differentiating human pluripotent stem cells into kidney organoids.

A Stepwise Monolayer Protocol for Kidney Organoid Differentiation: Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the stepwise monolayer protocol for differentiating human pluripotent stem cells into kidney organoids. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of kidney development that inform the protocol, detailed methodological steps, and key applications in disease modeling and nephrotoxicity screening. It further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, including novel approaches to enhance differentiation efficiency and reduce off-target cells. Finally, it explores validation techniques using single-cell transcriptomics and comparative analyses with other differentiation methods, offering a holistic resource for implementing and advancing this powerful in vitro model system.

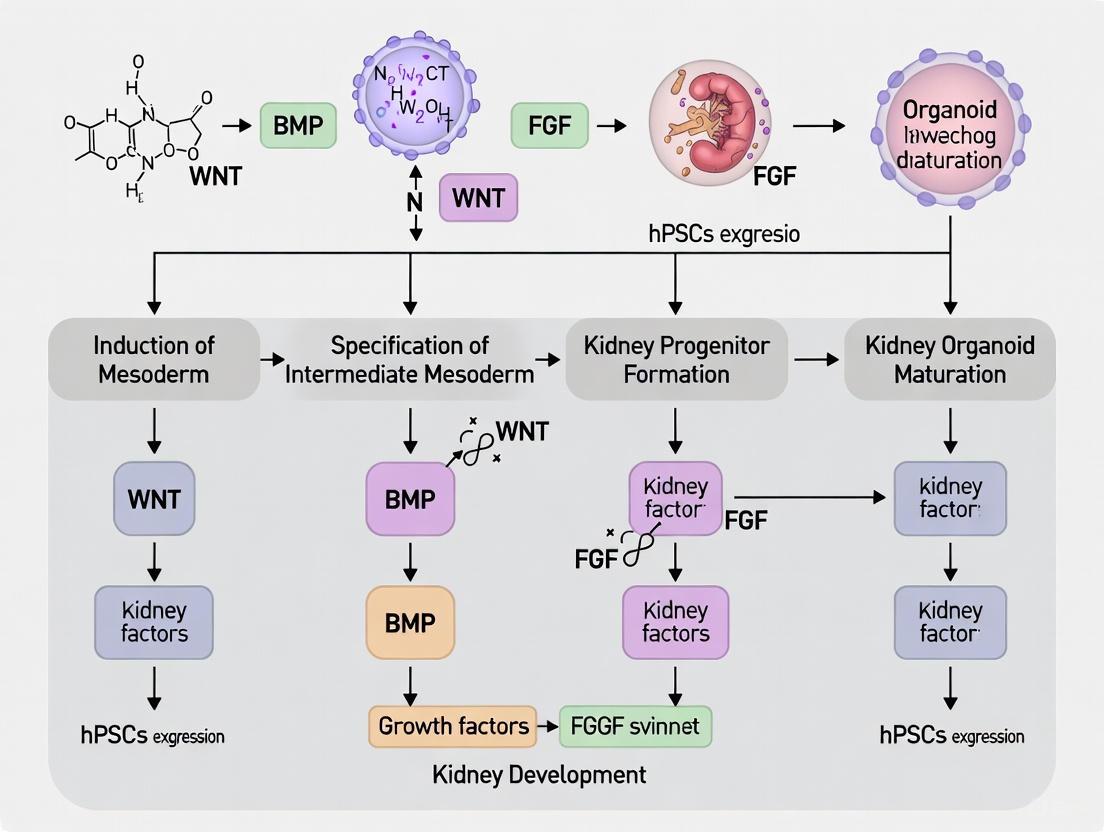

The Blueprint of the Kidney: How Developmental Biology Informs Organoid Differentiation

The in vitro differentiation of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) into kidney organoids requires the precise recapitulation of embryonic developmental stages. This process initiates with the formation of the primitive streak, which gives rise to the three germ layers, followed by the specification of the intermediate mesoderm (IM)—the embryonic precursor to the entire urogenital system [1] [2]. The IM subsequently patterns into the metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric bud, which through reciprocal signaling, generate the complex architecture of the kidney [2]. Mastering the trajectory from primitive streak to IM is therefore a critical, foundational step in protocols for generating kidney organoids for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [1] [2]. This Application Note details the key signaling pathways, provides a optimized, quantitative protocol, and lists essential reagents for the efficient and reproducible derivation of IM from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) in a monolayer culture system.

Key Signaling Pathways in Mesoderm Patterning

The stepwise differentiation from pluripotency to IM is orchestrated by the precise modulation of several conserved signaling pathways, primarily Nodal, WNT, and BMP [1]. The role of these pathways is hierarchical and concentration-dependent.

Nodal Signaling: Nodal, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, is fundamental for mesendoderm formation. Conventional models posit a morphogen gradient where high Nodal activity promotes definitive endoderm, while lower activity specifies mesoderm [1]. Recent protocol optimizations suggest that suppressing Nodal signaling during the mesoderm induction step can enhance the fidelity of IM differentiation [1].

WNT Signaling: WNT signaling is indispensable for the initial induction of the primitive streak and the subsequent formation of mesoderm progenitors [1] [2]. The GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 is commonly used to activate canonical WNT signaling. Its concentration and duration of application must be carefully optimized, as it also plays a role in maintaining posterior mesodermal progenitors [1].

BMP Signaling: Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling acts as a critical patterning cue. During IM specification, lower levels of BMP activity favor IM fate, while higher levels drive cells toward lateral plate mesoderm [1]. The concentration of BMP4 is therefore a key variable in protocol efficiency.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential activation and interaction of these pathways during the transition from pluripotent stem cells to intermediate mesoderm.

Quantitative Comparison of Published IM Induction Protocols

Substantial variability exists in published protocols for generating IM cells from hiPSCs, particularly in the choice of morphogens, small molecules, and their concentrations [1]. The table below summarizes and compares key parameters from several established methods, highlighting the optimized condition.

Table 1: Comparison of Intermediate Mesoderm Induction Protocols

| Protocol Reference | Primitive Streak / Mesoderm Induction (~48-96h) | Intermediate Mesoderm Induction (~48-72h) | Key IM Markers Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Protocol [1] | 3 μM CHIR99021 | 3 μM CHIR99021 + 4 ng/mL BMP4 | OSR1, GATA3, PAX2 |

| Yucer et al., 2017 [1] | 100 ng/mL Activin A + 3 μM CHIR99021 | 100 ng/mL BMP4 + 3 μM CHIR99021 | OSR1, GATA3, PAX2 |

| Knarston et al., 2020 [1] | 3 μM CHIR99021 (96h) | 10 ng/mL BMP4 + 1 μg/mL Heparin + 200 ng/mL FGF9 (72h) | OSR1, LHX1, PAX2 |

| Bejoy et al., 2022 [1] | 100 ng/mL Activin A + 3 μM CHIR99021 | 8 μM CHIR99021 (72h) | PAX8 |

| Gong et al., 2022 [1] | 5 μM CHIR99021 (36h) | 100 ng/mL bFGF + 10 nM Retinoic Acid (72h) | OSR1, PAX2, LHX1 |

The optimized protocol featured in this note demonstrates that a simplified, reproducible system using 3 μM CHIR99021 for mesoderm progenitor induction, followed by a combination of 3 μM CHIR99021 and a low concentration of BMP4 (4 ng/mL) for IM specification, efficiently generates cells expressing the canonical IM marker triad: OSR1, GATA3, and PAX2 [1]. This protocol effectively suppresses high Nodal signaling during the mesoderm step, which more faithfully recapitulates in vivo molecular features [1].

Stepwise Monolayer Protocol for IM Differentiation

This section provides a detailed methodology for the efficient and reproducible differentiation of hiPSCs into IM cells, adapted from the optimized protocol [1].

Materials and Pre-Culture Preparation

- hiPSC Line: UCSD167i-99-1 (or a well-characterated alternative) [1].

- Base Medium: mTeSR1 or mTeSR Plus medium [1].

- Matrigel: hPSC-qualified Matrigel for coating culture vessels [1].

- Small Molecules and Growth Factors:

- CHIR99021 (Tocris), reconstituted in DMSO.

- Recombinant Human BMP4 (R&D Systems), reconstituted as per manufacturer's instructions.

- Equipment: Standard humidified cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2), 6-well Nunclon Delta surface plates [1].

Pre-Culture Preparation: Maintain hiPSCs in an undifferentiated state in feeder-free conditions on Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR1 or mTeSR Plus medium. Culture medium should be replaced daily, and cells should be passaged every 4-6 days at a confluence of 70-80% using a gentle cell dissociation reagent. Ensure cells have a high viability and show no signs of spontaneous differentiation before starting the protocol [1].

Detailed Differentiation Procedure

Day 0: Mesoderm Induction Initiation

- Passage hiPSCs as a single-cell suspension and seed them onto a Matrigel-coated 6-well plate at an optimized density (e.g., 0.5 x 10^6 cells per well) in mTeSR Plus medium supplemented with a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632).

- Allow cells to attach for 24 hours. The target confluency at the start of differentiation should be approximately 90-95%.

Day 1-2: Primitive Streak / Mesoderm Progenitor Specification

- Aspirate the mTeSR Plus medium and replace it with fresh medium containing 3 μM CHIR99021.

- Incubate the cells for 48 hours. During this period, cells should undergo morphological changes and rapidly proliferate, transitioning into TBXT+/MIXL1+ mesoderm progenitors [1].

Day 3-4: Intermediate Mesoderm Specification

- On the morning of Day 3, carefully aspirate the medium containing CHIR99021.

- Replace it with fresh medium supplemented with 3 μM CHIR99021 and 4 ng/mL BMP4.

- Incubate the cells for a further 48 hours [1].

Day 5: Harvest and Analysis

- By Day 5, the cells are ready for harvest and analysis. The differentiated population should express key IM markers (OSR1, GATA3, PAX2) as confirmed by RT-qPCR and immunofluorescence staining [1].

Expected Outcomes and Quality Control

- Morphology: Cells will transition from compact, pluripotent colonies to a more uniform, proliferative monolayer with a distinct mesenchymal appearance.

- Molecular Characterization: Successful differentiation should be confirmed by analyzing the expression of marker genes.

- Downregulation: Pluripotency markers (OCT3/4, NANOG).

- Upregulation: Mesoderm progenitor markers (TBXT, MIXL1) followed by intermediate mesoderm markers (OSR1, GATA3, PAX2).

- Immunofluorescence: Staining should reveal nuclear expression of OSR1, GATA3, and PAX2 proteins in a high percentage of the cell population.

The following diagram provides a simplified overview of this experimental workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A robust and reproducible differentiation protocol relies on high-quality, well-defined reagents. The table below lists the essential materials required for the successful execution of the IM differentiation protocol described herein.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IM Differentiation

| Item | Function / Role in Protocol | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | A GSK3β inhibitor that activates canonical WNT signaling. Critical for inducing primitive streak and mesoderm progenitors, and for maintaining posterior mesoderm during IM specification. [1] | Tocris Bioscience |

| Recombinant Human BMP4 | A morphogen belonging to the TGF-β family. Used at low concentration to pattern mesoderm progenitors towards an intermediate mesoderm fate. [1] | R&D Systems |

| mTeSR1 / Plus Medium | A defined, serum-free culture medium optimized for the maintenance and growth of human pluripotent stem cells. Serves as the base medium for the differentiation protocol. [1] | StemCell Technologies |

| hPSC-qualified Matrigel | A basement membrane matrix extracted from mouse tumors. Used to coat culture vessels to provide a substrate that supports the attachment and growth of hiPSCs in a feeder-free system. [1] | Corning |

| Anti-OSR1 / GATA3 / PAX2 Antibodies | Validated antibodies for immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry. Essential for the molecular characterization and validation of successfully differentiated IM cells. [1] | Various suppliers (e.g., Abcam, R&D Systems) |

Troubleshooting and Protocol Validation

Common challenges during IM differentiation include low efficiency, high cell death, and contamination with off-target cell types. Low efficiency can often be attributed to suboptimal hiPSC quality or passage number; therefore, starting with healthy, high-viability cultures is paramount. Inconsistent WNT activation due to improper CHIR99021 reconstitution or storage can also lead to poor outcomes. High cell death during the initial days can be mitigated by using a ROCK inhibitor during cell passaging and ensuring gentle medium changes.

To validate a successful differentiation, researchers should employ a multi-faceted approach:

- RT-qPCR: Confirm the downregulation of pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG) and the sequential upregulation of TBXT/MIXL1 (mesoderm) followed by OSR1, GATA3, and PAX2 (IM) [1].

- Immunofluorescence: Demonstrate protein-level co-expression of OSR1, GATA3, and PAX2 in a significant proportion of the cell population [1].

- Flow Cytometry: If specific antibodies are available, quantify the percentage of cells positive for IM markers to provide a quantitative measure of protocol efficiency and reproducibility.

For advanced quality control, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) can be employed to comprehensively assess the transcriptional profile of the differentiated population and identify any contaminating off-target cell types. Computational tools like DevKidCC, a classifier trained on human fetal kidney data, can be used to robustly assign cell identity in scRNA-seq datasets and benchmark in vitro-derived IM cells against their in vivo counterparts [3].

The development of the mammalian kidney is orchestrated by a complex, sequential interplay of signaling pathways that guide the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into specialized renal structures. Understanding the precise roles of WNT, FGF, and BMP signaling is crucial for advancing kidney organoid research, particularly in the context of stepwise monolayer differentiation protocols. These pathways regulate key developmental processes including progenitor cell maintenance, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), and nephron patterning [2]. Recapitulating these signaling events in vitro has enabled the generation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), providing powerful models for studying renal development, disease modeling, and drug screening [4] [2]. This application note details the specific roles and experimental manipulation of these pathways in renal patterning, with a focus on practical protocols for kidney organoid differentiation.

Pathway Mechanisms and Functions

WNT Signaling Pathway

The WNT signaling pathway is a phylogenetically conserved system crucial for kidney development, functioning through both canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical branches [5] [6]. The canonical pathway initiates when WNT ligands bind to Frizzled (Fzd) receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, disrupting the β-catenin destruction complex (comprising Axin, APC, GSK3β, and CK1α). This stabilization allows β-catenin to accumulate and translocate to the nucleus, where it associates with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes governing cell fate, proliferation, and differentiation [5]. In contrast, non-canonical pathways (WNT/PCP and WNT/Ca²⁺) regulate cell polarity and migration independently of β-catenin [5].

During kidney development, WNT signaling plays multiple, stage-specific roles. WNT9b and WNT4 are particularly vital for nephron formation, with WNT9b from the ureteric bud inducing nephron progenitor cells in the metanephric mesenchyme, and WNT4 driving the subsequent mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) to form renal vesicles [6] [2]. The pathway's activity must be precisely controlled, as its dysregulation is implicated in kidney disease and fibrosis, wherein sustained activation promotes a reactive process leading to functional decline [7] [6].

FGF Signaling Pathway

The Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) signaling pathway is fundamental to kidney development, primarily regulating survival, proliferation, and branching morphogenesis. Signaling is initiated when FGF ligands bind to FGF receptors (FGFRs), triggering receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation. This activates downstream cascades, including the MAPK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and PLCγ pathways, which coordinate cellular responses such as proliferation, differentiation, and survival [8].

In the developing kidney, FGF signaling exhibits distinct spatial and functional roles. FGF9 and FGF8 are particularly crucial; FGF9, often combined with heparin, supports the survival and maintenance of nephron progenitor cells in the metanephric mesenchyme [4] [2]. Meanwhile, FGF8 promotes the differentiation of these progenitors into renal vesicles [2]. Furthermore, FGF signaling, in concert with GDNF from the metanephric mesenchyme, promotes the repetitive branching of the ureteric bud, which is essential for forming the collecting duct system [2]. In urine-derived renal progenitor cells, FGF2 drives the TGFβ-SMAD2/3 pathway to maintain self-renewal, highlighting its role in progenitor cell maintenance [8].

BMP Signaling Pathway

The Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) pathway, a subset of the TGFβ superfamily, signals through serine/threonine kinase receptors and intracellular SMAD transcription factors (primarily SMAD1/5/8). Ligand binding induces receptor complex formation, phosphorylating SMADs which then complex with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate target gene expression [2].

BMPs are critical for early kidney development, with BMP7 playing a particularly prominent role. It promotes the survival and proliferation of metanephric mesenchyme and nephron progenitor cells, preventing apoptosis [2] [7]. Beyond survival, BMP signaling also influences nephron patterning and segmentation. In adult-derived rat kidney stem cells, BMP7 is part of a defined cocktail that enables self-organization into 3D tubular organoids [2]. The pathway's activity is finely balanced, as it crosstalks with other key pathways like WNT and FGF to coordinate overall kidney morphogenesis.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Renal Patterning

| Pathway | Key Ligands | Receptors/Components | Primary Functions in Kidney Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| WNT | WNT9b, WNT4, WNT11 | Frizzled, LRP5/6, β-catenin, GSK3β | Nephron progenitor induction, MET, tubulogenesis, axis patterning [6] [2] |

| FGF | FGF9, FGF8, FGF2 | FGFR1-4, Heparin | Nephron progenitor maintenance, UB branching, cell survival, proliferation [8] [2] |

| BMP | BMP7, BMP4 | BMPR1/2, SMAD1/5/8 | Metanephric mesenchyme survival, proliferation, nephron patterning [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

Stepwise Monolayer Protocol for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

The generation of kidney organoids via a stepwise monolayer protocol efficiently recapitulates kidney development by directing hPSCs through intermediate mesoderm and metanephric mesenchyme stages. The following protocol, adapted from Morizane et al. and subsequent refinements, is designed for a 24-well plate format [9] [4].

Days -4 to -1: Intermediate Mesoderm Induction

- Seed hPS cells at 1–2 × 10^5 viable cells per well on vitronectin-coated 24-well plates in Essential 8 medium.

- The next day (designated day -4), replace the medium with Advanced RPMI 1640 containing 8 μM CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor that activates WNT signaling).

- Incubate for 3 days, changing the CHIR99021 medium daily, to induce primitive streak and posterior intermediate mesoderm fates.

Day -1: Metanephric Mesenchyme Patterning

- Replace the medium with Advanced RPMI 1640 containing 200 ng/mL FGF9 and 1 μg/mL heparin. Some protocols include 10 ng/mL Activin A at this stage [4].

- Incubate for 24 hours to pattern the cells toward a metanephric mesenchyme identity.

Day 0: 3D Aggregation and Nephron Induction

- On day 0, treat the monolayer cultures with 5 μM CHIR99021 for 1 hour while maintaining FGF9 and heparin.

- Dissociate the cells into single cells and seed them in V-bottom 96-well plates to promote 3D spheroid formation. Cell seeding numbers can be optimized (e.g., 500 to 250,000 cells/well) to influence final organoid composition [4].

- Maintain the 3D spheroids in free-floating culture with continued FGF9 and heparin until day 7 to promote renal vesicle formation.

Days 7-16: Maturation

- From day 7 onwards, culture the organoids in basal medium without growth factors to allow spontaneous differentiation and maturation into various nephron segments [4].

- The organoids should develop visible glomerular-like (PODXL+/WT1+) and tubular-like (LTL+/ECAD+) structures by day 16.

Protocol for Generating Proximal-Biased Kidney Organoids

Recent advances enable the generation of proximal-biased kidney organoids with enhanced maturation of proximal tubule cells, which are crucial for modeling renal reabsorption and nephrotoxicity [10].

- Follow the standard stepwise monolayer protocol through the 3D aggregation stage (Days -4 to 0).

- During early nephrogenesis (e.g., days 1-3 post-aggregation), add a PI3K inhibitor (e.g., LY294002) to the culture medium. This manipulation activates Notch signaling, shifting nephron axial differentiation toward proximal tubule fates.

- Continue culture until maturation (up to day 16). These proximal-biased organoids will exhibit expanded populations of HNF4A⁺/HNF1B⁺ proximal tubule precursor cells and show higher expression of solute carriers (e.g., organic cation and anion transporters). They demonstrate improved functional responses to nephrotoxic injury, including upregulation of injury markers KIM1/HAVCR1 and SOX9, and downregulation of HNF4A [10].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| WNT Pathway Agonists | CHIR99021 | GSK3β inhibitor; activates canonical WNT signaling to induce mesoderm and nephron progenitors [4] | 5-8 μM [4] |

| FGF Signaling Ligands | FGF9, FGF2, FGF8 | Maintains nephron progenitors; promotes UB branching and differentiation [8] [2] | 200 ng/mL [4] |

| BMP Signaling Ligands | BMP7, BMP4 | Supports survival and proliferation of metanephric mesenchyme [2] | Protocol-dependent |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Reagents | Trypsin/EDTA, Accutase | Dissociates monolayer cells for 3D aggregation into spheroids | Cell line-specific |

| Extracellular Matrix | Vitronectin, Matrigel | Provides substrate for monolayer culture and cell attachment | Manufacturer-recommended |

| Basal Media | Advanced RPMI 1640, Essential 8 | Base medium for differentiation and pluripotency maintenance | N/A |

| Signaling Inhibitors | PI3K inhibitors (e.g., LY294002) | Shifts differentiation toward proximal tubule fates in specific protocols [10] | Protocol-dependent |

The precise manipulation of WNT, FGF, and BMP signaling pathways is fundamental to generating kidney organoids that faithfully recapitulate human renal development. The protocols detailed herein provide a foundation for the stepwise differentiation of hPSCs into kidney organoids with emerging cellular complexity and function. Current research focuses on enhancing the maturation and vascularization of these organoids, reducing batch-to-batch variability, and achieving more complete nephron segmentation. Future directions include the integration of these organoids with microfluidic systems to create organ-on-a-chip models, which will further improve their physiological relevance and utility in disease modeling and drug nephrotoxicity screening [2]. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of these signaling manipulations will be paramount for realizing the full translational potential of kidney organoids in regenerative medicine.

Nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) represent a foundational population in kidney development, responsible for generating all the epithelial cells of the nephron, the functional unit of the kidney [11]. These self-renewing cells balance proliferation with differentiation during organogenesis, with their availability being a major determinant of final nephron number at birth [12]. In recent years, the field has made significant advances in deriving induced nephron progenitor-like cells (iNPCs) from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), creating powerful platforms for studying human kidney development, disease modeling, and drug screening [11] [2]. This Application Note details current protocols and mechanistic insights for the efficient generation, expansion, and differentiation of NPCs within the context of kidney organoid research, providing researchers with practical methodologies for leveraging these cells in renal studies.

Nephron Progenitor Cell Fundamentals

NPCs, also known as cap mesenchyme, reside in a specialized niche during kidney development where they receive signals from the ureteric bud and surrounding stroma [12]. They are characterized by the expression of key transcription factors including SIX2, WT1, PAX2, OSR1, and CITED1 [12] [2]. The balance between NPC self-renewal and differentiation is tightly regulated by both signaling pathways and metabolic processes.

- Developmental Significance: NPCs undergo mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) to form all nephron segments except the collecting duct [2]. Their gradual recruitment into forming nephrons follows a stereotyped developmental program [10].

- Metabolic Regulation: Young NPCs (embryonic day 13.5 in mice) demonstrate significantly higher glycolytic flux compared to older NPCs (postnatal day 0), with this high glycolysis rate supporting self-renewal, while inhibition of glycolysis stimulates differentiation [12].

- Transcriptional Control: SIX2 acts as a master regulator maintaining the progenitor state, while a Cited1+/Six2+ subpopulation remains refractory to differentiation signals compared to Cited1-/Six2+ cells that are poised to differentiate [12].

Protocols for NPC Generation and Differentiation

Expansion of hPSC-Derived Induced Nephron Progenitor Cells

Recent protocols have enabled the purification and expansion of hPSC-derived induced nephron progenitor-like cells (iNPCs) in monolayer culture [11].

Table 1: Key Reagents for iNPC Expansion and Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Components | Function | Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Maintenance | mTeSRplus medium, Geltrex | Maintains hiPSCs in primed pluripotent state | [13] |

| Initial Differentiation | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) | Activates WNT signaling; induces posterior primitive streak | [4] |

| Progenitor Patterning | FGF9, Heparin, Activin A | Patterns cells toward intermediate mesoderm | [4] |

| iNPC Expansion Medium | Chemically defined "hNPSR-v2" | Supports long-term iNPC self-renewal and expansion | [11] |

| Nephron Differentiation | Air-liquid interface culture | Promotes 3D nephron organoid formation from iNPCs | [11] |

Stepwise Protocol:

- hPSC Culture: Maintain hiPSCs in essential 8 medium on vitronectin-coated plates [4].

- Primitive Streak Induction: Treat with 8μM CHIR99021 in Advanced RPMI 1640 for 3 days [4].

- Intermediate Mesoderm Commitment: Switch to media containing 200ng/ml FGF9, 1μg/ml heparin, and 10ng/ml activin A for 24 hours [4].

- iNPC Expansion: Purify and expand iNPCs in specialized hNPSR-v2 medium in monolayer culture [11].

- Nephron Organoid Differentiation: Transfer iNPCs to air-liquid interface culture for 21 days to generate nephron organoids with enhanced podocyte maturity and minimal off-target cell types [11].

DMSO Pre-conditioning for Enhanced Differentiation

Pre-treatment of hiPSCs with low-dose dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) enhances subsequent kidney organoid differentiation efficiency [9] [13].

Protocol Details:

- Pre-treatment: Culture hiPSCs in mTeSRplus medium supplemented with 1-2% DMSO for 24 hours prior to differentiation induction [13].

- Mechanism: DMSO alters the expression of pluripotency transcription factors, modifies the epigenetic landscape, and affects colony morphology, priming cells for more efficient differentiation [13].

- Outcome: Treated cells show enhanced expression of the key nephron progenitor marker SIX2 after 9 days of kidney organoid differentiation and improved tubular organoid development [9].

Generating Proximal-Biased Kidney Organoids

Controlling nephron precursor differentiation toward proximal tubule lineages creates organoids with enhanced functionality for disease modeling and toxicity testing [10].

Key Intervention:

- Transient PI3K inhibition during early nephrogenesis activates Notch signaling, shifting nephron axial differentiation toward proximal precursor states [10].

- This protocol generates HNF4A+ proximal tubule precursors that mature to express solute carriers including organic cation and organic anion transporters [10].

- These "proximal-biased" organoids demonstrate improved physiological function and better mimic in vivo injury responses to nephrotoxic compounds [10].

Signaling Pathways Regulating NPC Fate

The balance between NPC self-renewal and differentiation is governed by an intricate network of signaling pathways and metabolic processes.

Table 2: Metabolic and Signaling Regulation of NPC Fate

| Regulatory Mechanism | Effect on NPCs | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| High Glycolytic Flux | Supports self-renewal; younger NPCs have 30% higher ATP levels | Inhibition with YN1 (5-25μM) enhances nephrogenesis in cultured embryonic kidneys [12] |

| FGF/PI3K/Akt Signaling | Maintains progenitor state and proliferation | Inhibition decreases glycolytic flux and promotes differentiation [12] |

| Notch Signaling | Promotes proximal tubule specification | Activated by PI3K inhibition; drives HNF4A+ proximal precursor formation [10] |

| WNT/β-catenin | Regulates balance between self-renewal and differentiation | Required for NPC maintenance and MET induction [2] |

Applications and Validation Models

Nephrotoxicity and Disease Modeling

Kidney organoids derived from NPCs have been widely applied for modeling genetic kidney diseases, nephrotoxicity screening, and studying disease mechanisms [2].

- Cisplatin Toxicity Modeling: Chimeric nephrons generated from progenitor cells demonstrate dose-dependent increases in kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM1/HAVCR1) expression in proximal tubule cells upon cisplatin exposure, mirroring in vivo injury responses [14].

- Genetic Disease Modeling: Organoids enable study of polycystic kidney disease, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, and other genetic disorders using patient-specific iPSCs [2].

- Functional Assessment: Mature organoids exhibit filtration and reabsorption capabilities, with systemically administered fluorescent dextran observed around podocytes and on apical surfaces of proximal tubule cells [14].

In Vivo Integration Models

Neonatal niche injection represents a promising approach for generating long-term viable chimeric nephrons with host urinary tract integration [14].

Protocol Overview:

- Donor Cell Preparation: Isolate renal progenitor cells from E14.5 fetal mice or differentiate from hiPSCs [14].

- Host Preparation: Expose kidneys of neonatal (P0.5-P1.5) mice through a small back incision [14].

- Cell Injection: Inject donor cells under the renal capsule using a 34G Hamilton syringe [14].

- Integration Assessment: Donor cells integrate into host cap mesenchyme within 2 days and form chimeric glomeruli and tubules within 2 weeks [14].

This method achieves 85% survival rate with P1.5 neonates and generates chimeric nephrons that remain viable for over 4 months, with functional filtration and reabsorption capacity [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NPC Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specification | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| hiPSC Lines | LUMCi004-C (female, urine-derived); TISSUi001-A (male, PBMC) | Protocol optimization and differentiation studies | [13] |

| CHIR99021 | 5-8μM in Advanced RPMI 1640 | GSK3β inhibitor for WNT activation and primitive streak induction | [4] |

| FGF9 | 200ng/ml with 1μg/ml heparin | Intermediate mesoderm patterning and nephron progenitor maintenance | [4] |

| DMSO | 1-2% in mTeSRplus for 24h | hiPSC pre-conditioning for enhanced differentiation efficiency | [9] [13] |

| hNPSR-v2 Medium | Chemically defined formulation | Expansion and maintenance of hPSC-derived iNPCs in monolayer | [11] |

| Y-27632 | 10μM | ROCK inhibitor for improving cell survival after passaging | [13] |

NPCs serve as the fundamental building blocks for nephron formation, both in development and in engineered kidney organoids. The protocols detailed in this Application Note provide researchers with robust methodologies for generating, expanding, and differentiating these cells into kidney structures with enhanced maturity and functionality. Recent advances in metabolic conditioning, signaling manipulation, and in vivo integration models have significantly improved the physiological relevance of NPC-derived tissues. As the field continues to evolve, further refinement of these protocols will enable more precise modeling of kidney diseases, more accurate nephrotoxicity screening, and ultimately, progress toward regenerative therapies for kidney disease.

Cellular Composition of a Mature Kidney Organoid

Within the field of regenerative nephrology, the generation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) represents a transformative approach for modeling development, disease, and drug response. A critical benchmark for the success of this technology is the achievement of a mature cellular composition that closely mirrors the complexity of the native kidney. This Application Note details the characteristic cellular makeup of a mature kidney organoid, provides a detailed protocol for its generation via a stepwise monolayer method, and outlines essential quality control measures to validate organoid fidelity for research and drug development applications.

Cellular Census of a Mature Kidney Organoid

A mature kidney organoid is a complex, multi-lineage structure. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has been instrumental in providing a high-resolution census of the cell types present, revealing both on-target renal cells and common off-target populations.

Table 1: Characteristic Cellular Composition of a Mature hPSC-Derived Kidney Organoid

| Cell Type | Key Marker Genes | Approximate Frequency in D29 Organoids | Functional & Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Podocyte-like | NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, PODXL, SYNPO |

14–29% [15] [16] | Forms glomerular-like structures with immature foot processes and apico-basal polarity [17]. |

| Proximal Tubule-like | LTL, LRP2, SLC3A1, CUBN |

Varies by protocol [15] | Exhibits functional uptake capabilities (e.g., albumin endocytosis); expresses injury markers like KIM1 [2] [17]. |

| Distal Tubule-like | ECAD, SLC12A1, GATA3 |

Varies by protocol [15] [16] | Includes thick ascending limb (TAL) characteristics; distinct distal convoluted tubule (DCT) segment is often absent [16]. |

| Nephron Progenitor-like | SIX2, PAX2, OSR1, CITED1 |

Present [9] [16] | Population of progenitor cells maintained in an undifferentiated state, supporting ongoing nephrogenesis. |

| Stromal/Interstitial-like | FOXD1, PDGFRβ, SULT1E1, DKK1 |

Present (Multiple subsets) [4] [16] | Includes mesenchymal, fibroblast, and pericyte-like populations. |

| Endothelial-like | CD31, PECAM1 |

Rare (Sparse and unorganized) [2] [16] | Observed within organoids but typically requires co-culture or in vivo transplantation for maturation and organization. |

| Collecting Duct-like | AQP2, ECAD, GATA3 |

Typically absent unless co-differentiated [18] | Not generated in standard protocols; requires integration of ureteric bud (UB) progenitors for formation [18]. |

| Off-Target Non-Renal | SOX2, STMN2 (Neuronal), MYOG (Muscle), PMEL (Melanocyte) |

10–21% [15] [16] | Undesired cell types reflecting incomplete lineage specification; can be reduced through protocol refinement or transplantation [16]. |

The maturity and transcriptional profile of these organoid cell types are most similar to first and second-trimester human fetal kidney, highlighting an opportunity for further maturation [15] [16]. A key structural limitation of most protocols is the absence of a functional collecting system, though recent advances in co-culturing nephron progenitors with ureteric bud progenitors have successfully generated organoids with integrated, patent collecting ducts [18].

Experimental Protocol: Stepwise Monolayer Differentiation

The following detailed protocol, adapted from established methods [4], directs the differentiation of hPSCs into kidney organoids with a mature cellular composition.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Key Signaling Pathway Modulated |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3β inhibitor; induces primitive streak and posterior intermediate mesoderm. | WNT Activation [4] [2] |

| FGF9 | Supports survival and expansion of nephron progenitor populations. | FGF Signaling [4] [2] |

| Heparin | Co-factor that enhances FGF signaling activity. | FGF Signaling [4] |

| Activin A | Contributes to mesoderm patterning and induction. | TGF-β Signaling [4] |

| Vitronectin | Extracellular matrix coating for monolayer cell culture. | Cell Adhesion & Survival |

| Advanced RPMI 1640 | Basal medium for the initial differentiation phases. | N/A |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part 1: Monolayer Differentiation to Posterior Intermediate Mesoderm (Days -4 to 0)

- Day -4: Seed hPSCs as a monolayer on vitronectin-coated plates in Essential 8 medium.

- Days -4 to -1: Induce primitive streak and IM commitment by replacing the medium with Advanced RPMI 1640 containing 8 µM CHIR99021. Incubate for 72 hours.

- Days -1 to 0: Pattern the IM by treating with Advanced RPMI 1640 containing 200 ng/mL FGF9 and 1 µg/mL heparin. Some protocols also include 10 ng/mL Activin A at this stage [4]. Incubate for 24 hours.

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway interactions during this initial differentiation phase:

Part 2: 3D Spheroid Aggregation and Organoid Maturation (Days 0 to 16)

- Day 0: Pre-treat the PIM-committed monolayer cultures with 5 µM CHIR99021 for 1 hour while maintaining FGF9 and heparin.

- Dissociate the cells into a single-cell suspension.

- Aggregation: Seed the cells into a low-adhesion U-bottom 96-well plate to promote 3D spheroid formation. The number of cells per spheroid (e.g., 8,000) influences the final organoid composition and maturity, with lower numbers often promoting more differentiated structures [4].

- Days 0 to 7: Culture the 3D spheroids in free-floating conditions in medium containing FGF9 and heparin to promote renal vesicle formation.

- Days 7 to 16: Withdraw growth factors to allow for spontaneous differentiation into segmented nephron structures. Maintain organoids in free-floating culture with regular medium changes.

The overall workflow from monolayer to mature organoid is summarized below:

Quality Control and Validation

Rigorous validation of the final organoid's cellular composition is essential for ensuring experimental reproducibility and relevance.

- scRNA-seq Census: Profiling a representative organoid batch via scRNA-seq is the gold standard for comprehensively identifying all cell types, their proportions, and transcriptional maturity compared to human fetal and adult kidney datasets [15] [16].

- Immunofluorescence Confirmation: Validate the presence and spatial organization of key structures using confocal microscopy with antibodies against markers listed in Table 1 (e.g., PODXL for podocytes, LTL for proximal tubules) [4] [2].

- Functional Assays:

- Refinement Strategies: To improve organoid quality:

- Inhibit Off-Target Cells: Adding inhibitors of specific pathways, such as the BDNF-NTRK2 pathway, can reduce neuronal off-target cells by up to 90% without affecting kidney differentiation [15].

- Transplantation: Transplanting organoids under the mouse kidney capsule enhances maturation and vascularization while diminishing off-target cell populations [16].

- Bioengineering: Integration with microfluidic organ-on-chip platforms can improve physiological relevance and maturation through enhanced nutrient delivery and mechanical cues [19] [20].

A Practical Guide to the Stepwise Monolayer Protocol and Its Research Applications

Kidney organoids are three-dimensional (3D) in vitro structures derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These miniaturized organ models recapitulate key aspects of kidney development, architecture, and function, providing an unprecedented platform for studying renal development, disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [21] [2]. The technology has evolved significantly since initial protocols were established in 2014-2015, with current methods enabling generation of organoids containing segmented nephron-like structures including glomerular, proximal tubule, loop of Henle, and distal tubule components [21] [2].

The fundamental principle underlying kidney organoid generation involves stepwise recapitulation of embryonic kidney development in vitro. During mammalian development, the kidney arises from the intermediate mesoderm through reciprocal interactions between two key embryonic progenitors: the metanephric mesenchyme (MM), which gives rise to nephrons, and the ureteric bud (UB), which forms the collecting system [2]. Current differentiation protocols mimic these developmental stages by precisely timing the activation and inhibition of key signaling pathways to direct hPSCs through primitive streak, intermediate mesoderm, and nephron progenitor stages before final maturation into 3D renal tissues [4] [21] [2].

Key Differentiation Protocols

Established Methodologies

Several core protocols form the foundation of kidney organoid generation, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The table below summarizes the principal established methodologies:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Kidney Organoid Differentiation Protocols

| Protocol | Cell Source | Key Signaling Factors | Efficiency of NPC Generation | Organoid Components | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taguchi et al. [21] | Mouse ESC/hiPSCs | BMP4, Activin A, FGF2, CHIR99021, FGF9, Retinoic acid | ~62% SIX2+ NPCs | Wt1/nephrin+ glomeruli; cadherin6+ proximal tubules; E-cadherin+ distal tubules | Pioneering method for kidney reconstruction in vitro | Requires mouse embryonic spinal cord coculture; lower efficiency; immature structures |

| Morizane et al. [21] [2] | hESCs/hiPSCs | CHIR99021, Activin A, FGF9 | 80-90% SIX2+ NPCs | Multi-segmented nephrons: podocytes, proximal tubules, loops of Henle, distal tubules | Chemically defined medium; high efficiency; no coculture required | Line-to-line variability; no collecting duct system |

| Freedman et al. [21] | hESCs/hiPSCs | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibition only) | Not specified | Segmented nephrons with proximal tubules, podocytes, endothelial cells | Simple, low-cost, high-throughput; no FGF2/Activin/BMP | Random organoid size; non-uniform; off-target cells |

| Little's Team [21] | iPSC/hESC | CHIR99021, FGF9 | Not specified | 6-10 nephrons surrounded by endothelial and stromal populations | High cell yield (3-4x static culture); cost-effective | Immature structures |

Recent Protocol Advancements

Recent innovations have addressed several limitations of earlier methods. Scalable production approaches now enable the generation of kidney organoids from hPSCs using a reproducible and affordable system that allows differentiation into different renal cell types. This method forces cell-to-cell contact by generating 3D spheroids through self-aggregation of varying numbers of posterior intermediate mesoderm (PIM)-committed cells (from 500 to 250,000 cells), resulting in organoids with different extents of differentiation and cellular composition [4]. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis has confirmed that this approach generates organoids containing renal endothelial-like, mesenchymal-like, proliferating, podocyte-like, and tubule-like cell populations across all tested conditions [4].

Another significant advancement addresses the integration of collecting systems. A persistent limitation of most kidney organoid protocols has been the absence of collecting ducts, which are essential for establishing a structural mechanism for distal drainage of fluid from nephrons. A recent breakthrough describes an efficient hPSC co-culture system that assembles UB progenitors with nephrogenic mesenchyme to form a network of collecting ducts structurally integrated with nephrons via fusion with the distal tubule [18]. This integration creates organoids with the most representative distribution of nephron segments, including collecting ducts, yet described, achieving a higher state of maturation across all segments [18].

Additionally, pretreatment strategies to enhance differentiation efficiency have emerged. Treatment of hiPSCs with low-dose dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) prior to kidney organoid differentiation using the Morizane stepwise 2D monolayer-based protocol enhances the expression of the key metanephric mesenchyme nephron progenitor marker SIX2 and improves differentiation protocol efficiency toward tubular kidney organoids [9].

Stepwise Monolayer to 3D Culture Protocol

Detailed Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for generating 3D kidney organoids from hPSCs, integrating multiple established protocols:

Stage-Specific Protocol Details

Stage 1: hPSC Culture and Cavitated Spheroid Formation (Days -3 to 0)

Begin with high-quality hPSCs maintained in mTeSR1 medium on Matrigel-coated plates. On Day -3, dissociate cells using ACCUTASE and seed as single cells at 30,000 cells/well in a 6-well plate in mTeSR1 supplemented with CloneR2 (1:10 dilution). After 24 hours (Day -2), overlay cells with cold mTeSR1 containing Matrigel (0.25 mg/mL protein concentration) and incubate for 24 hours. On Day -1, perform a full medium change to mTeSR1 without Matrigel. By Day 0, hPSC colonies should form round, cavitated spheroids of 50-100 µm in size [22].

Stage 2: Primitive Streak and Intermediate Mesoderm Induction (Days 0-4)

On Day 0, initiate differentiation by replacing mTeSR1 with Stage 1 Medium (STEMdiff Kidney Basal Medium + Supplement SG) or Advanced RPMI 1640 with 8 µM CHIR99021. Incubate for 36-40 hours to induce primitive streak formation. On Day 1.5, replace with Stage 2 Medium (STEMdiff Kidney Basal Medium + Supplement DM) or Advanced RPMI 1640 with 200 ng/mL FGF9, 1 µg/mL heparin, and 10 ng/mL activin A. Culture for 2 days, then refresh with fresh Stage 2 Medium and culture for an additional 3 days to promote intermediate mesoderm and early nephron progenitor formation [4] [22].

Stage 3: Nephron Progenitor Expansion (Days 4-7)

Maintain cells in Stage 2 Medium with FGF9 signaling to support nephron progenitor cell expansion. During this period, cells should express key nephron progenitor markers including SIX2, SALl1, WT1, and PAX2. Efficiency of nephron progenitor generation typically reaches 80-90% with optimized protocols [21] [2].

Stage 4: 3D Aggregation and Organoid Maturation (Days 7-16)

On Day 7, dissociate nephron progenitor cell monolayers using ACCUTASE or TrypLE Express Enzyme and aggregate into 3D spheroids. For the scalable approach, seed dissociated single cells in V-bottom 96-well plates to generate 3D spheroids by self-aggregation of 500-250,000 PIM-committed cells per well [4]. Alternatively, use AggreWell plates to generate organoids of uniform size by seeding 5,000 viable cells per microwell [22]. Maintain 3D spheroids in free-floating conditions in differentiation medium without growth factors for organoid maturation until Day 16. During this period, nephron-like structures segment into glomerular, proximal tubule, distal tubule, and loop of Henle compartments [4].

Signaling Pathways in Kidney Organoid Differentiation

The stepwise differentiation of hPSCs into kidney organoids requires precise temporal activation and inhibition of key developmental signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the critical pathways and their roles:

Pathway Functions and Temporal Regulation

WNT/β-catenin signaling serves as the master regulator initiating kidney organoid differentiation. Transient activation using GSK3β inhibitors such as CHIR99021 drives hPSCs toward posterior primitive streak identity, representing the first critical step in renal lineage specification. Subsequent moderate WNT signaling supports intermediate mesoderm formation and later stages of nephrogenesis, demonstrating the pathway's stage-dependent functions [2].

FGF signaling, particularly through FGF9, plays multiple essential roles throughout the differentiation process. Following primitive streak induction, FGF9 promotes patterning of the intermediate mesoderm and subsequently supports maintenance and expansion of nephron progenitor populations. Continued FGF signaling is essential for the formation of renal vesicles and the transition to epithelial structures [4] [2].

BMP signaling contributes to kidney organoid differentiation in a stage-specific manner. Early BMP signaling, particularly with BMP4, supports mesodermal induction, while later BMP7 exposure promotes metanephric mesenchyme survival and proliferation. The precise timing and concentration of BMP exposure must be carefully controlled to avoid off-target effects [21] [2].

Retinoic acid (RA) signaling contributes to anterior-posterior patterning of the intermediate mesoderm, helping to specify the metanephric kidney region versus other intermediate mesoderm derivatives. RA signaling typically occurs during intermediate mesoderm patterning stages in specific protocols [21].

Notch signaling plays a crucial role in nephron segmentation during later organoid maturation stages. This pathway influences the fate specification of different nephron segments, including proximal tubules, distal tubules, and podocytes, ensuring appropriate cellular diversity within the organoid [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Category | Specific Reagent | Function | Example Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | Advanced RPMI 1640; DMEM/F-12; STEMdiff Kidney Basal Medium | Foundation for differentiation media | Morizane et al.; Takasato et al.; Commercial kits |

| WNT Agonists | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) | Induces primitive streak and posterior intermediate mesoderm | All major protocols (1-10 µM) |

| Growth Factors | FGF9; FGF2; Activin A; BMP4; BMP7 | Patterning and maintenance of nephron progenitors | Taguchi et al.; Morizane et al. |

| Enzymes for Dissociation | ACCUTASE; TrypLE Express | Gentle cell dissociation for 2D to 3D transition | Scalable protocol; Commercial kit |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel; Synthetic hydrogels | Support 3D structure and provide biochemical cues | Most protocols; Vascularization studies |

| Cell Aggregation Tools | AggreWell plates; V-bottom plates | Form uniform 3D spheroids | Scalable production; Commercial kit |

| Pluripotency Media | mTeSR1; Essential 8 | Maintain hPSCs before differentiation | Initial culture; Commercial kit |

| Specialized Supplements | Heparin; Recombinant Albumin | Enhance growth factor activity and cell viability | Multiple protocols |

Applications and Future Directions

Kidney organoids have enabled significant advances in disease modeling, particularly for genetic kidney disorders such as polycystic kidney disease (PKD) and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). Patient-derived iPSCs allow creation of organoids that recapitulate disease-specific phenotypes, providing platforms for studying disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds [21] [2].

In drug screening and nephrotoxicity testing, kidney organoids offer a more physiologically relevant alternative to traditional 2D cell cultures. Organoids demonstrate appropriate cellular responses to nephrotoxic compounds and provide human-specific toxicity data that may improve prediction of adverse drug effects in clinical trials [23] [2]. Recent research has highlighted how the differentiation state of organoid models significantly influences their response to toxic compounds, underscoring the importance of maturation level in assay predictivity [24].

For regenerative medicine, kidney organoids represent a promising potential cell source. Transplantation studies have demonstrated engraftment of human kidney organoids into porcine kidneys during ex vivo machine perfusion, with successful in vivo integration and viability assessment [4]. The incorporation of functional collecting systems through UB organoid fusion represents a critical step toward creating organoids with potential for future therapeutic application [18].

Emerging technologies are addressing current limitations in organoid maturation, vascularization, and scalability. Microfluidic systems and bioreactors improve nutrient delivery and enhance organoid maturation and vascular network formation [21] [2]. Deep learning approaches are being developed to predict differentiation outcomes from bright-field images of organoids, potentially improving quality control and selection of optimally differentiated tissues [25]. These innovations collectively advance the field toward more physiologically relevant and clinically applicable kidney organoid technologies.

The generation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) is a groundbreaking technology that recapitulates renal development in vitro, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [26] [27]. The fidelity of this process hinges on precisely timed manipulations of key developmental signaling pathways. This application note details the critical steps of CHIR99021-mediated priming and FGF9-driven maturation, contextualizing them within a stepwise monolayer protocol for kidney organoid differentiation. By providing explicit methodologies and quantitative benchmarks, we aim to empower researchers in reproducibly generating high-quality kidney organoids with minimized off-target cell populations.

Developmental Principles and Signaling Pathways

The directed differentiation of hPSCs into kidney organoids strategically mimics the natural process of kidney embryogenesis, which originates from the intermediate mesoderm (IM) [26]. The goal of the protocol is to first induce a posterior primitive streak population, which subsequently gives rise to the posterior intermediate mesoderm (PIM), the common precursor for both the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) and ureteric bud (UB) [4] [27]. The metanephric mesenchyme contains nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) that will differentiate into the full nephron structure—including glomeruli, proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and distal tubules—while the ureteric bud lineage forms the collecting duct system [4].

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway manipulations that guide hPSCs through these developmental stages toward functional kidney organoids.

The developmental trajectory from hPSCs to kidney organoids involves two major phases. The CHIR99021 priming phase initiates differentiation by inducing a posterior primitive streak fate through WNT activation [27]. The subsequent FGF9-driven maturation phase patterns this primitive streak into posterior intermediate mesoderm and supports the expansion and subsequent differentiation of nephron progenitors [26] [4]. A critical modification to the classic Takasato protocol involves extending the FGF9 treatment to reduce the appearance of off-target chondrocytes, a common challenge in prolonged organoid cultures [28].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol Specifications

The following section outlines the complete, stepwise workflow for generating kidney organoids, from initial cell plating to mature organoid formation. The process integrates both two-dimensional monolayer differentiation and three-dimensional organoid culture.

Comprehensive Stepwise Workflow

The entire procedure, from pluripotent stem cells to mature kidney organoids, is visualized in the following workflow diagram.

Detailed Protocol Specifications

For practical implementation, the following table summarizes the key parameters from established kidney organoid differentiation protocols.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Kidney Organoid Differentiation Protocols

| Differentiation Stage | Treatment | Duration | Key Markers Induced | Protocol Variations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 Priming | 8-10 μM CHIR99021 [4] [29] | 2-4 days [26] [4] | TBX6 (Primitive Streak) [27] | Duration optimized per cell line [27] |

| FGF9-Driven Maturation | 200 ng/ml FGF9 + 1 μg/ml Heparin [4] [29] | 4 days to 1 week+ [28] [26] | OSR1, WT1, HOXD11 (IM) [27] [30] | 1-week extension reduces cartilage [28] |

| 3D Aggregation | Cell dissociation & aggregation | Day 7 [4] [29] | PAX2, LHX1 (Renal Vesicles) [4] | 500-250,000 cells/aggregate [4] |

| Growth Factor Withdrawal | Basal medium without FGF9 | From day 12-16 [4] [29] | PODXL (Podocytes), LTL (Proximal Tubules) [4] | Organoids harvested day 18-25 [28] [29] |

Critical Modifications and Optimizations

CHIR99021 Priming: Inducing Posterior Primitive Streak

The initial priming step is critical for directing hPSCs toward the appropriate mesodermal lineage. This stage requires precise optimization of CHIR99021 concentration and treatment duration, which varies between cell lines [27]. The objective is to achieve a highly efficient induction of late primitive streak cells, which express TBX6, while avoiding lateral plate mesoderm fates. This is typically accomplished using CHIR99021 at 8-10 μM in Advanced RPMI 1640 medium for 2-4 days [4] [29]. The optimal duration must be determined empirically for each hPSC line based on morphological changes and marker expression.

FGF9-Driven Maturation: Patterning and Nephron Formation

Following primitive streak induction, FGF9 signaling is applied to pattern the cells into posterior intermediate mesoderm, characterized by the expression of OSR1, WT1, and HOXD11 [27] [30]. The combination of FGF9 with heparin (200 ng/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively) is typically maintained for approximately 4 days in the monolayer culture protocol [26] [29]. A critical protocol modification involves extending FGF9 treatment for an additional week during the subsequent 3D culture stage. This extended treatment has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the development of off-target chondrocyte populations—a common issue in prolonged organoid cultures—without adversely affecting the development of renal structures [28].

Quality Assessment and Functional Validation

Rigorous quality control is essential for generating reproducible and physiologically relevant kidney organoids. The following criteria and methods should be employed to validate successful differentiation.

Morphological and Molecular Benchmarks

Table 2: Quality Control Criteria for Kidney Organoids

| Assessment Category | Benchmark | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Size & Morphology | ~200 μm or larger diameter [30] | Bright-field microscopy |

| Cell Composition | ~10-20% podocytes (PODXL+), ~40% proximal tubule cells (LTL+), ~10% distal tubule cells (CDH1+) [30] | Immunofluorescence, FACS, scRNA-seq [4] [30] |

| Nephron Segmentation | Presence of segmented nephrons: PODXL+CD31- glomeruli, LTL+ proximal tubules, ECAD+ distal tubules/loops of Henle [4] | Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy |

| Functional Transporters | Expression of PEPTs (apical) and OCTs (basolateral) [30] | qPCR, immunostaining, functional uptake assays |

| Batch Variation | Coefficient of variation <10% for size, morphology, and function between organoids [30] | Quantitative image analysis, functional assays |

Troubleshooting Common Differentiation Issues

- Low Efficiency of IM Induction: Optimize CHIR99021 exposure duration empirically for each cell line. Consider using H9 hESCs or lines maintained in ReproFF2 if persistent issues occur [27].

- Presence of Off-Target Cells: Extend FGF9 treatment during the 3D culture phase by one week to reduce chondrocyte formation [28]. Ensure growth factor concentrations are precise.

- Poor 3D Structure Formation: Confirm cell aggregation is performed using V-bottom or ultra-low attachment plates with an optimal seeding density (e.g., 8,000 cells/aggregate for RV formation) [4] [27].

- Lack of Functional Maturation: Allow sufficient maturation time (up to day 25) after growth factor withdrawal. Consider incorporating flow-induced shear stress or more complex culture conditions to enhance maturation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent | Function | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3β inhibitor; induces WNT signaling to direct hPSCs toward posterior primitive streak fate. [4] [27] | 8-10 μM in Advanced RPMI [4] [29] |

| FGF9 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 9) | Patterns posterior intermediate mesoderm; supports nephron progenitor expansion and inhibits off-target chondrogenesis. [28] [26] | 200 ng/ml with 1 μg/ml Heparin [4] [29] |

| Heparin | Sulfated glycosaminoglycan; enhances FGF9 signaling stability and efficacy. [26] [29] | 1 μg/ml, used concurrently with FGF9 [4] [29] |

| Vitronectin | Recombinant attachment matrix for coating culture vessels; supports hPSC maintenance and monolayer differentiation. | Used for coating plates before hPSC seeding [4] |

| APEL/Advanced RPMI 1640 | Chemically defined, serum-free medium; used as the basal medium for differentiation steps to ensure reproducibility. [29] | Used throughout differentiation protocol [4] [29] |

The precise execution of CHIR99021 priming and FGF9-driven maturation is fundamental to generating high-fidelity kidney organoids from hPSCs. The initial WNT activation establishes the developmental trajectory toward kidney lineages, while sustained FGF9 signaling ensures proper patterning, minimizes off-target differentiation, and promotes the development of complex, segmented nephron structures. By adhering to the detailed protocols, quality controls, and reagent specifications outlined in this application note, researchers can reliably produce kidney organoids suitable for advanced applications in disease modeling, nephrotoxicity screening, and ultimately, regenerative medicine approaches. The continued refinement of these critical steps, particularly regarding prolonged maturation and vascular integration, remains a vital focus for the field.

Within the rapidly advancing field of kidney organoid research, the precise characterization of differentiated nephron segments—podocytes, proximal tubules, and distal segments—stands as a critical benchmark for success. This application note provides a detailed framework for the identification and validation of these essential cell types within kidney organoids generated via stepwise monolayer protocols. By integrating contemporary molecular markers, functional assays, and advanced analytical techniques, researchers can rigorously assess the cellular composition and maturity of their renal models, thereby enhancing the reliability of data generated for developmental studies, disease modeling, and nephrotoxicity screening.

The protocol is framed within a broader thesis on kidney organoid differentiation, which emphasizes recapitulating human kidney development in vitro [31]. This involves the sequential induction of posterior primitive streak, intermediate mesoderm, and ultimately, self-organizing kidney organoids containing multiple renal progenitor populations [31] [27]. The accurate characterization of the resulting nephron segments is paramount for validating this differentiation approach and for its application in translational research.

Molecular Marker Tables for Nephron Segments

Podocyte Markers

Podocytes, highly specialized cells of the glomerular filtration barrier, can be identified using a combination of structural and molecular markers. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies have further refined our understanding of podocyte heterogeneity in health and disease.

Table 1: Key Molecular Markers for Podocyte Characterization

| Marker | Type | Expression/Location | Significance in Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARHGEF26 | Protein/Gene | Significantly downregulated in Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) [32] | Novel potential diagnostic biomarker; decreased expression indicates podocyte injury in DKD [32] |

| Slit Diaphragm Proteins | Protein Complex | Foot processes of podocytes [33] | Key component of the glomerular filter; essential for selective permeability [33] |

| WT1 | Transcription Factor | Podocyte nucleus [27] | Marks podocyte identity and is a critical regulator of podocyte function. |

| SYNPO | Cytoskeletal Protein | Podocyte cell body and foot processes | A structural marker of podocyte maturity and integrity. |

The detection of these markers can be achieved through standard immunofluorescence staining and RNA analysis techniques. Furthermore, functional assessment of podocytes can involve evaluating their response to mechanical stress and molecular signals from their microenvironment, which is crucial for maintaining glomerular health [33].

Proximal Tubule Markers

The proximal tubule is responsible for the reabsorption of the majority of filtrate and is a primary site of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Its cells possess distinct transport capabilities.

Table 2: Key Molecular Markers for Proximal Tubule Characterization

| Marker | Type | Expression/Location | Significance in Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| AQP1 | Channel Protein | Apical/Basolateral Membranes [34] | Facilitates water reabsorption; expressed in proximal tubule and thin descending limb [34] |

| Megalin & Cubilin | Endocytic Receptors | Apical Membrane [31] | Mediate endocytosis of proteins and ligands; evidence of functional maturity in organoids [31] |

| HNF4A | Transcription Factor | Nucleus [34] | Master regulator of proximal tubule cell formation and maturation; essential for AQP1 expression [34] |

| SLC34A1 | Transporter | Apical Membrane | Encodes the sodium-phosphate cotransporter NaPi-IIa; a specific marker for proximal tubule identity. |

A critical demonstration of functional maturity in kidney organoids is the presence of megalin- and cubilin-mediated endocytosis in the proximal tubules [31]. Additionally, the expression of transporters like organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) and copper transporter 1 (CTR1) allows these cells to uptake nephrotoxicants such as cisplatin, leading to specific cell death—a vital assay for nephrotoxicity testing [31].

Distal Nephron Segments

The distal nephron, including the thick ascending limb (TAL), distal convoluted tubule (DCT), and collecting duct, is crucial for fine-tuning electrolyte balance and urine concentration.

Table 3: Key Markers for Distal Nephron Segments

| Segment | Marker | Type | Expression/Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thin Descending Limb | AQP1 [34] | Channel Protein | Apical Membrane |

| Bst1 [34] | Surface Protein | Cell Membrane | |

| Thick Ascending Limb | UMOD | Protein | Apical Membrane/Cytoplasm |

| Distal Convoluted Tubule | NCC | Transporter | Apical Membrane |

| Collecting Duct | AQP2 [27] | Channel Protein | Apical Membrane |

| CDH1 [27] | Adhesion Protein | Basolateral Membrane |

A key developmental insight is the origin of the thin descending limb. Lineage tracing using a Slc34a1eGFPCre line (a proximal tubule marker) has demonstrated that a subset of thin descending limb cells are descendants of proximal tubule cells [34]. This finding is crucial for understanding nephron patterning in organoids.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Immunofluorescence Characterization of Podocytes

Objective: To confirm the presence and structural organization of podocytes within kidney organoids. Materials: Fixed kidney organoid cryosections, blocking buffer (e.g., 5% BSA in PBS), primary antibodies (e.g., against WT1, ARHGEF26, SYNPO), fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies, DAPI, and mounting medium. Workflow:

- Fixation & Sectioning: Fix organoids in 4% PFA for 15-20 minutes at room temperature. Embed in OCT compound and section at 5-10 μm thickness using a cryostat.

- Permeabilization & Blocking: Permeabilize sections with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes. Incubate with blocking buffer for 1 hour to reduce non-specific binding.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate sections with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The following day, wash with PBS and incubate with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

- Imaging & Analysis: Wash thoroughly, counterstain nuclei with DAPI, and mount. Analyze using a confocal microscope. Co-localization of nuclear WT1 with cytoplasmic markers like SYNPO confirms podocyte identity. Notably, reduced ARHGEF26 signal may indicate a diseased state [32].

Functional Assay for Proximal Tubule Maturity

Objective: To validate the functional maturity of proximal tubule cells in organoids by assessing receptor-mediated endocytosis. Materials: Kidney organoids, fluorescently-labeled dextran or albumin (e.g., 10-70 kDa), cell culture medium, live-cell imaging setup or flow cytometer. Workflow:

- Preparation: Transfer organoids to a suitable imaging dish with fresh medium. Allow them to equilibrate in a 37°C incubator for at least 30 minutes.

- Uptake Assay: Add the fluorescent ligand (e.g., 50 μg/mL dextran) to the medium. Incubate for a defined period (e.g., 30-120 minutes) at 37°C.

- Control: Include control organoids incubated at 4°C to inhibit active endocytosis, or pre-treated with a endocytic inhibitor.

- Termination & Analysis:

- For imaging: Wash organoids extensively with cold PBS to remove surface-bound ligand. Fix with 4% PFA and image using confocal microscopy. Co-localization of the fluorescent signal with a proximal tubule marker (e.g., LRP2/megalin) confirms specific uptake [31].

- For flow cytometry: Dissociate organoids into single cells after uptake, wash, and analyze intracellular fluorescence immediately using a flow cytometer. A rightward shift in fluorescence intensity compared to the 4°C control indicates active endocytosis.

Gene Expression Analysis via RT-qPCR

Objective: To quantitatively assess the expression levels of key segment-specific markers. Materials: RNA extraction kit (e.g., TRIzol), DNase I, reverse transcription kit, SYBR Green qPCR master mix, gene-specific primers (e.g., for SIX2, SLC34A1, AQP2, UMOD, etc.), and a real-time PCR instrument. Workflow:

- RNA Extraction: Homogenize pooled organoids or micro-dissected regions in TRIzol. Extract total RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol. Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- cDNA Synthesis: Use 0.5-1 μg of total RNA for reverse transcription using a high-capacity cDNA synthesis kit.

- qPCR Setup: Prepare reactions with SYBR Green master mix, gene-specific primers (validated for efficiency), and cDNA template. Run in technical duplicates/triplicates.

- Data Analysis: Calculate relative gene expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method. Normalize to stable housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, HPRT1). Compare expression across different batches of organoids or against control samples. For instance, validation of ARHGEF26 as a podocyte marker was confirmed using RT-qPCR [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Kidney Organoid Characterization

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) | Starting material for organoid generation | Both ESCs and iPSCs can be used; line-specific differentiation efficiency varies [27]. |

| Slc34a1eGFPCre Mouse Line | Lineage tracing of proximal tubule and its derivatives | Used to demonstrate that thin descending limb cells originate from proximal tubule cells [34]. |

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3β inhibitor; activates Wnt signaling | Used in initial primitive streak induction and later to trigger nephrogenesis from NPCs [27]. |

| FGF9 | Growth Factor | Directs differentiation of primitive streak to intermediate mesoderm [31]. |

| Microfluidic Chip System | Creates a proximal tubule-on-chip model | Enhances transporter expression and polarization for improved nephrotoxicity and drug transport assays [35]. |

| Anti-ARHGEF26 Antibody | Detects a novel podocyte injury marker | Validated via Western blot and immunofluorescence; shows significant downregulation in DKD [32]. |

Workflow Visualization: From Pluripotency to Characterized Organoids

The entire process, from stem cell differentiation to the final characterization of nephron segments, can be summarized in the following workflow. This integrates the differentiation protocol with the specific characterization techniques outlined in this note.

The systematic characterization of podocytes, proximal tubules, and distal segments is indispensable for validating the success of kidney organoid differentiation protocols. By employing the panel of molecular markers, functional assays, and detailed methodologies described in this application note, researchers can robustly quantify the identity, maturity, and functionality of the nephron segments within their models. This rigorous approach not only strengthens the fidelity of in vitro organoids as models of human kidney biology and disease but also paves the way for their standardized application in drug development and regenerative medicine strategies. The integration of novel biomarkers, such as ARHGEF26 for podocytes, and advanced culture systems, like tubule-on-chip models, continues to push the boundaries of what can be achieved with these complex tissues.

The advent of three-dimensional kidney organoid technology represents a paradigm shift in nephrological research, offering an unprecedented in vitro platform that recapitulates key aspects of human kidney development, structure, and function. Derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), these self-organizing structures provide a versatile tool for investigating disease mechanisms, performing high-throughput drug screening, and exploring regenerative medicine applications [2]. The field has progressed significantly since the initial establishment of protocols that direct hPSCs through stages mimicking embryonic kidney development, culminating in organoids containing segmented nephrons with glomerular and tubular structures [2] [36].

The "bench to bedside" translation of this technology is particularly relevant for drug nephrotoxicity screening, which remains a significant challenge in pharmaceutical development. Kidney organoids offer a human-specific, physiologically relevant model that can potentially overcome the limitations of traditional animal models and two-dimensional cell cultures [2]. This Application Note details current methodologies and applications of kidney organoids, with a specific focus on their implementation within drug development pipelines for nephrotoxicity assessment and their use in modeling hereditary kidney diseases, providing researchers with detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to advance their translational research.

Kidney Organoid Differentiation: Core Principles and Protocols

Developmental Biology Informing Differentiation Strategies

The differentiation of hPSCs into kidney organoids strategically recapitulates key stages of embryonic kidney development. The mammalian kidney, the metanephros, arises from the intermediate mesoderm (IM) through reciprocal inductive signaling between two key embryonic tissues: the ureteric bud (UB) and the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) [2]. The UB evolves into the collecting duct system, while the MM contains self-renewing nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) that differentiate into all the epithelial components of the nephron—including the glomerulus, proximal tubule, loop of Henle, and distal tubule—through a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) process [2] [36]. This developmental cascade is orchestrated by precisely timed signaling pathways, with WNT, FGF, and BMP playing particularly critical roles [2].

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Kidney Development and Their In Vitro Recapitulation

| Signaling Pathway | Role in Kidney Development | Commonly Used Agonists/Antagonists in Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| WNT/β-catenin | Induction of posterior primitive streak; MET initiation | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) [2] [4] |

| FGF | NPC proliferation and survival; UB branching | FGF9 [2] [4] |

| BMP | MM survival and proliferation | BMP7 [2] |

| RA | Patterning of the IM | Retinoic Acid |

Established Monolayer-Based Differentiation Protocols

The stepwise 2D monolayer-based protocol, as pioneered by Morizane et al. (2015), provides a robust framework for generating kidney organoids with reduced variability and improved reproducibility [9] [2]. This approach involves directing a confluent monolayer of hPSCs through defined developmental stages by sequential activation and inhibition of key signaling pathways.

Figure 1: Workflow of a stepwise monolayer-based kidney organoid differentiation protocol.

A critical refinement to this protocol involves the pretreatment of hPSCs with low-dose (1-2%) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) prior to differentiation induction. This preconditioning step has been shown to alter the expression of pluripotency transcription factors, modify the epigenetic landscape, and enhance the differentiation efficiency toward nephron progenitor cells, ultimately resulting in kidney organoids with improved tubular formation [9]. The treated cells demonstrate enhanced expression of the key nephron progenitor marker SIX2 after nine days of differentiation [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Organoid Differentiation

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Example | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Base Medium | Advanced RPMI 1640 | Chemically defined basal medium for differentiation [4] |

| WNT Agonist | CHIR99021 (8 µM initial; 5 µM later) | GSK3β inhibitor inducing primitive streak and IM [2] [4] |

| Growth Factors | FGF9 (200 ng/mL) | Supports MM patterning and NPC expansion [2] [4] |

| Chemical Modifier | Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO 1-2%) | Pretreatment to enhance differentiation efficiency [9] |