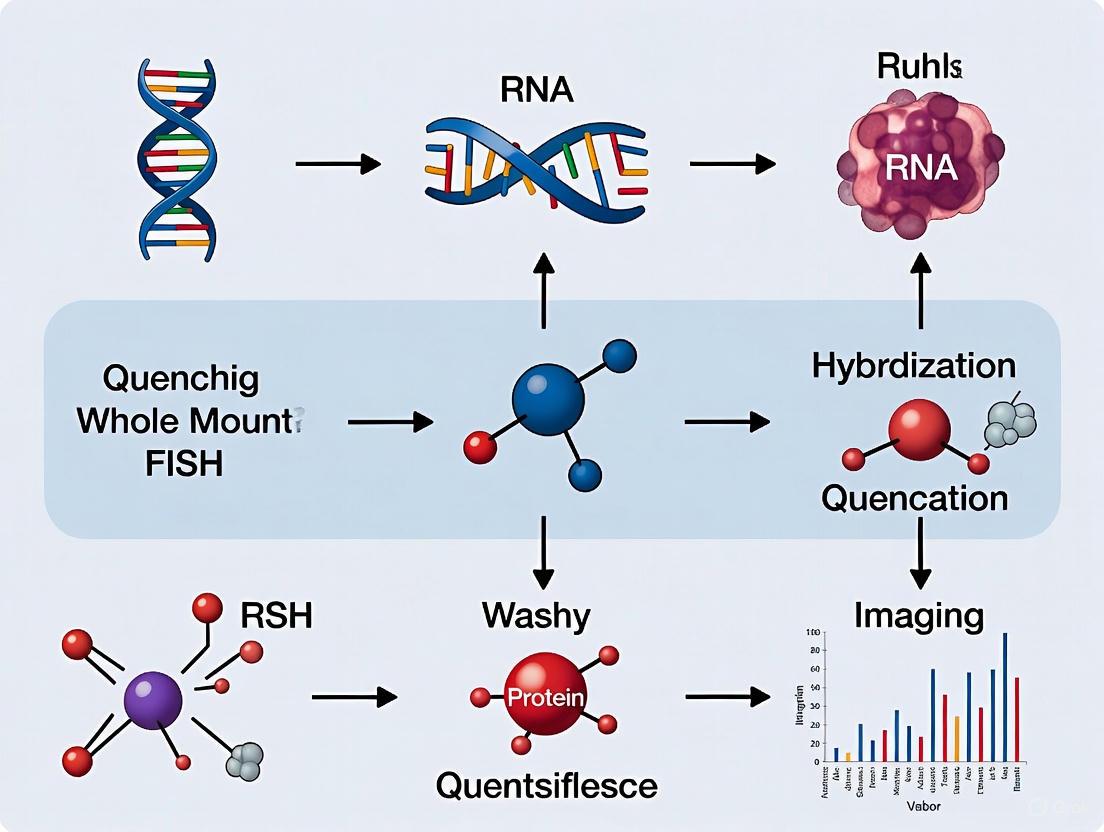

Advanced Strategies for Quenching Autofluorescence in Whole-Mount FISH: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the critical challenge of autofluorescence in whole-mount fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Advanced Strategies for Quenching Autofluorescence in Whole-Mount FISH: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the critical challenge of autofluorescence in whole-mount fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we detail the sources of autofluorescence in various tissues, explore chemical quenching agents like TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher and hydrogen peroxide bleaching, and present integrated optical clearing methods such as LIMPID that combine refractive index matching with autofluorescence reduction. The content includes systematic troubleshooting protocols for common issues like insufficient quenching and signal loss, validated through comparative studies across tissue types and model organisms. By enabling high-resolution, three-dimensional gene expression mapping with improved signal-to-noise ratios, these optimized methodologies significantly enhance the reliability of transcriptional analysis in developmental biology, neuroscience, and drug discovery applications.

Understanding Autofluorescence: Sources, Challenges, and Impact on Whole-Mount FISH Sensitivity

FAQs: Understanding Autofluorescence in Whole Mount FISH

What is autofluorescence and why is it a particular problem for whole mount FISH? Autofluorescence is the natural emission of light by biological structures when excited by specific wavelengths, a phenomenon inherent to cells and tissues [1]. It is problematic for whole mount fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) because the faint, omnipresent background signal can permeate the entire 3D tissue sample, obscuring the specific signals from fluorescently labeled RNA probes and significantly reducing the signal-to-noise ratio [2]. This issue is compounded in thick tissues where the total autofluorescence contribution from all layers can be substantial.

Which biological molecules are the most common sources of interfering autofluorescence? The most common endogenous fluorophores include specific metabolic co-factors, structural proteins, and age-related pigments [1] [3] [4]. Their excitation and emission spectra often overlap with those of popular fluorescent dyes, making them a primary source of interference.

Table 1: Common Sources of Biological Autofluorescence

| Endogenous Fluorophore | Primary Location | Excitation/Emission Peaks (nm) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H [1] | Cytoplasm, Metabolic cofactor | Ex: 340 / Em: 450 | Indicator of cellular metabolic state; only the reduced form (NAD(P)H) fluoresces. |

| Flavins (FAD) [1] | Mitochondria, Metabolic coenzyme | Ex: 380-490 / Em: 520-560 | In an opposite state to NAD(P)H; only the oxidized form (FAD) is fluorescent. |

| Lipofuscin [1] [5] | Lysosomal deposits in postmitotic cells (e.g., neurons, RPE) | Ex: 345-490 / Em: 460-670 | An "age pigment" that accumulates over time; has a very broad emission spectrum. |

| Collagen [1] | Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Ex: 270 / Em: 390 | A key structural protein prevalent in connective tissues, dermis, and around vasculature. |

| Elastin [1] | Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Ex: 350-450 / Em: 420-520 | Often interspersed with collagen, providing tissues with mechanical extensibility. |

| Tryptophan [1] | Proteins (amino acid residue) | Ex: 280 / Em: 350 | An essential amino acid found in most folded proteins. |

| Melanin [1] | Skin, Hair, Eyes (pigment) | Ex: 340-400 / Em: 360-560 | A natural photoprotective pigment; its concentration can vary widely. |

How does tissue fixation contribute to autofluorescence? Aldehyde fixatives like formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, which are commonly used to preserve tissue structure, react with proteins to create fluorescent crosslinks throughout cells and tissues [1]. This chemical reaction introduces a non-biological source of autofluorescence that can be difficult to distinguish from the natural background.

Troubleshooting Guide: Quenching Autofluorescence in Whole Mount FISH

Problem: High Background from Intrinsic Tissue Autofluorescence

Solution 1: Photochemical Bleaching (OMAR) Oxidation-mediated autofluorescence reduction (OMAR) is a photochemical pre-treatment that effectively suppresses autofluorescence prior to FISH protocols [2].

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Following embryo collection or tissue dissection, fix samples with standard fixatives like paraformaldehyde [2].

- OMAR Treatment: Incubate fixed tissues in a solution of 2.5-4.5% hydrogen peroxide in Tris-EDTA buffer, supplemented with SDS or Tween 20 as a detergent [2] [6].

- Irradiation: Expose the sample to high-intensity cold white light (e.g., from high-power LED spotlights or panels delivering up to 20,000 lumens) for several hours. The solution should show bubbles, indicating an active oxidation reaction [2].

- Post-treatment: After bleaching, wash the tissue thoroughly with a buffer such as PBST before proceeding to the permeabilization and RNA-FISH steps [2].

Mechanism: The treatment generates reactive oxygen species that chemically modify fluorescent molecules in the tissue, breaking their conjugated double-bond systems and thereby reducing their ability to fluoresce [2].

Visual Guide: OMAR Experimental Workflow

Solution 2: Chemical Reduction with Borohydride For autofluorescence induced specifically by aldehyde fixatives, chemical reduction can be an effective solution [7] [6].

- Protocol: After fixation and before FISH, treat tissues with a solution of sodium borohydride (e.g., 0.1-1% in buffer) for 30 minutes to 1 hour. This treatment reduces the fluorescent crosslinks created by aldehydes [6].

Problem: Autofluorescence Overwhelming Weak FISH Signals

Solution: Strategic Probe Selection and Optical Clearing Choosing the right probes and combining them with optical clearing can dramatically improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Probe Selection: Opt for fluorescent labels excited in the near-infrared (NIR) range (e.g., Cy7, Alexa Fluor 750). The excitation and emission wavelengths of these dyes fall outside the peaks of most common autofluorophores like NADH, collagen, and lipofuscin, thereby avoiding a significant portion of the background [1].

Optical Clearing: Use refractive index matching solutions like LIMPID (Lipid-preserving index matching for prolonged imaging depth) to render tissues transparent. This reduces light scattering, allowing clearer imaging deeper into the tissue and improving the detection of specific FISH signals [6].

- Application: After FISH staining, mount the tissue in a LIMPID solution containing saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol. This single-step, aqueous clearing method preserves fluorescence and is compatible with FISH probes [6].

Problem: Persistent Lipofuscin Autofluorescence

Understanding the Source: Lipofuscin is an intractable autofluorescent "age pigment" that accumulates in postmitotic cells as intracellular granules from incomplete lysosomal digestion [5]. It has a very broad excitation and emission spectrum, making it particularly difficult to filter out.

- Strategy: Due to its chemical stability, lipofuscin is highly resistant to both chemical and photochemical bleaching methods [5]. The most effective strategy is avoidance.

- Imaging Modalities: If possible, use imaging techniques that are not based on fluorescence, such as bioluminescence imaging, which leaves autofluorophores unstimulated [1].

- Spectral Unmixing: Employ advanced imaging systems that can acquire the full emission spectrum at every pixel. Computational analysis can then be used to "unmix" the specific FISH signal from the characteristic spectral signature of lipofuscin after data acquisition [8] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Autofluorescence Management

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Quenching Autofluorescence

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [2] | Active oxidizing agent in OMAR photochemical bleaching. | Effectively targets a wide range of endogenous fluorophores through an oxidative mechanism. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) [6] | Chemical reducing agent. | Specifically targets and reduces aldehyde-induced fluorescence from fixation. |

| High-Intensity LED Light Source [2] | Provides energy for the OMAR photochemical reaction. | Drives the oxidation process necessary for bleaching; cold light prevents heat damage. |

| HCR v3.0 FISH Probes [2] [9] | Amplifying RNA probes for signal detection. | Provides high signal amplification and low background, improving the signal-to-noise ratio against autofluorescence. |

| LIMPID Clearing Solution [6] | Aqueous refractive index matching medium. | Reduces light scattering, enabling deeper imaging and better signal clarity in whole mounts. |

| Phenol Red-Free Media [1] | Cell culture medium for live-cell preparations. | Eliminates background fluorescence from this common media additive before imaging. |

How Autofluorescence Compromises Signal-to-Noise Ratio in 3D Gene Expression Mapping

FAQ: Understanding the Core Problem

What is autofluorescence and how does it directly impact my 3D gene expression data?

Autofluorescence is background fluorescence emitted naturally by biological tissues or induced by fixation. It is not attributed to your specific FISH probes or antibodies. This background signal acts as a constant source of noise in your images. Because the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is calculated as your specific signal divided by the background noise, autofluorescence directly lowers the SNR [10]. A low SNR can mask the detection of low-abundance RNA transcripts, reduce the dynamic range of your image, and complicate the automated segmentation and analysis of cells in 3D space [11].

Why is autofluorescence a particularly severe problem for whole-mount samples and 3D mapping?

Whole-mount tissues are thick and dense, meaning there is a greater volume of autofluorescent material (e.g., mitochondria, lysosomes, collagen) contributing to background noise compared to thin sections [2] [6]. Furthermore, advanced 3D imaging techniques like confocal microscopy collect light from a very small focal volume, which inherently limits the number of photons collected from your specific probe. When this already low signal is contaminated by autofluorescence, the resulting images can be grainy and lack contrast, making it difficult to achieve high-resolution 3D reconstructions [10].

What are the main types of autofluorescence I need to worry about?

The primary sources are categorized as follows [12] [13] [14]:

- Biological Autofluorescence: Originates from endogenous fluorophores within cells and tissues, including:

- Fixative-Induced Autofluorescence: Caused by aldehyde-based fixatives like formaldehyde and paraformaldehyde. These reagents form fluorescent Schiff bases by reacting with cellular amines and proteins [12] [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Proven Methods to Quench Autofluorescence

Chemical and Photochemical Quenching

Several chemical treatments can effectively reduce or eliminate autofluorescence prior to hybridization.

Table 1: Autofluorescence Quenching Reagents and Protocols

| Method | Mechanism | Example Protocol | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) Treatment | Oxidizes and bleaches endogenous fluorescent pigments [2] [15]. | Incubate fixed tissues in alcoholic or aqueous 6% H₂O₂ solution, often under bright light illumination (OMAR protocol) [2] [15]. | Whole-mount insect tissues, mouse embryonic limb buds, various vertebrate organs [2] [15]. | Alcoholic H₂O₂ better preserves RNA for FISH. Aqueous H₂O₂ may degrade RNA targets [15]. |

| Sudan Black B / Eriochrome Black T | Lipophilic dyes that bind to and quench lipofuscin and other autofluorescent lipids [14]. | Treat fixed and permeabilized tissues with a solution of 0.1-1% Sudan Black B in 70% ethanol for 30-60 minutes [14]. | Tissues with high lipofuscin (e.g., aged neurons, skeletal muscle) [14]. | Sudan Black B fluoresces in the far-red channel; avoid if using fluorophores in this range [14]. |

| Sodium Borohydride | Reduces aldehyde-induced fluorescent Schiff bases to non-fluorescent alcohols [12] [14]. | Treat samples with a fresh solution of 0.1% sodium borohydride in PBS for 10-30 minutes after fixation [14]. | Tissues fixed with aldehydes (formalin, PFA) [12] [14]. | Can have variable effectiveness and may damage some epitopes or tissue morphology [14]. |

| Commercial Reagents (e.g., TrueVIEW) | Ready-to-use solutions that chemically suppress a broad spectrum of autofluorescence [14]. | Follow manufacturer's instructions, typically involving incubation after fixation and permeabilization. | A general-purpose solution for various autofluorescence sources. | Cost may be a factor for large-scale studies. |

Optimized Sample Preparation and Imaging

Preventing autofluorescence is often more effective than trying to remove it later.

- Fixation: Avoid glutaraldehyde, which causes strong autofluorescence. Use paraformaldehyde instead, and for cells, consider chilled ethanol as an alternative [14]. Always use the shortest fixation time required to preserve morphology [14].

- Probe and Fluorophore Selection: If your tissue has high green autofluorescence (e.g., from collagen or NADH), choose fluorophores that emit in the far-red spectrum (e.g., Cy5, Alexa Fluor 647) to maximize separation from the noise [14].

- Optical Clearing: Methods like LIMPID (Lipid-preserving index matching for prolonged imaging depth) use aqueous solutions to render tissues transparent. This reduces light scattering, increases imaging depth, and can improve the effective SNR by allowing more signal photons to be collected [6].

- Microscope Settings: Optimize your pinhole size on a confocal microscope. A very small pinhole reduces background but also sacrifices too much signal. An optimal size maximizes the SNR by balancing signal and background rejection [10].

Experimental Protocol: OMAR for Whole-Mount RNA-FISH

The Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction (OMAR) protocol is a robust method for suppressing autofluorescence in whole-mount samples like embryos and tissues [2].

Workflow: OMAR Autofluorescence Quenching

Step-by-Step Methodology [2]:

Sample Collection and Fixation:

- Collect mouse embryonic limb buds (or your tissue of interest) and fix overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C.

- Dehydrate through a graded methanol series and store at -20°C.

OMAR Photochemical Bleaching:

- Rehydrate the samples.

- Prepare a bleaching solution of 4.5% hydrogen peroxide in a 1:1 mixture of methanol and PBS.

- Place samples in the solution and illuminate with a high-intensity cold white light source (e.g., 20,000 lumen LED panels) for 1-2 hours. The appearance of bubbles indicates an active oxidation reaction.

- Wash the samples thoroughly.

Tissue Permeabilization and Hybridization:

- Permeabilize the bleached tissues with a detergent-based solution (e.g., containing Tween-20).

- Perform whole-mount RNA-FISH using your preferred protocol, such as the sensitive Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) v3.0.

Clearing and Imaging:

- Optically clear the samples using a compatible method like LIMPID [6] or the protocol described in the paper.

- Proceed with 3D image acquisition using confocal or light-sheet microscopy.

Key Resources: Hydrogen peroxide, high-intensity LED light source, HCR RNA-FISH probes and amplifiers [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Autofluorescence Management

| Reagent | Function in Autofluorescence Control | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Active ingredient in photochemical (OMAR) and chemical bleaching methods to oxidize fluorescent pigments [2] [15]. | 33% w/v stock, diluted to 4.5-6% in methanol/PBS or aqueous buffer [2] [15]. |

| Sudan Black B | Lipophilic dye used to quench autofluorescence from lipofuscin and other lipids [14]. | 0.1-1% solution in 70% ethanol [14]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Reducing agent used to diminish autofluorescence induced by aldehyde fixation [12] [14]. | 0.1% solution in PBS, prepared fresh [14]. |

| TrueVIEW Autofluorescence Quenching Kit | Commercial ready-to-use solution to suppress broad-spectrum autofluorescence [14]. | Vector Laboratories product # SP-8400 [14]. |

| LIMPID Clearing Solution | Aqueous optical clearing agent that improves SNR and imaging depth via refractive index matching, compatible with FISH [6]. | Home-made solution containing saline-sodium citrate (SSC), urea, and iohexol [6]. |

| CoralLite 594/647 Fluorophores | Fluorophores emitting in the far-red spectrum, chosen to avoid overlap with common autofluorescence in the blue/green range [14]. | Proteintech antibody conjugation kits and conjugated antibodies [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I resolve issues with deep tissue penetration and imaging depth?

A primary challenge in whole-mount FISH is achieving adequate penetration of probes and reagents into thick tissue samples, which is crucial for clear imaging.

Troubleshooting Strategies:

| Challenge | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Probe Penetration | Incomplete tissue permeabilization prevents probes from reaching targets [16]. | Optimize permeabilization by using agents like Triton X-100 or proteinase K; adjust concentration, time, and temperature to balance accessibility with morphology preservation [16]. |

| Weak Signal in Sample Core | Probe molecules cannot diffuse deeply into the tissue, or signal is attenuated/absorbed [17]. | Implement a robust permeabilization protocol combined with optical clearing techniques after hybridization to reduce light scattering and improve signal detection from deep layers [17]. |

| Uneven Signal Distribution | Patchy or uneven permeabilization and denaturation across the sample [16]. | Ensure uniform reagent distribution during processing and avoid air bubbles during mounting. Standardize sample preparation steps to improve reproducibility [16]. |

How can I reduce high background autofluorescence?

Tissue autofluorescence, which can mask specific FISH signals, is a major obstacle in fluorescence-based techniques, especially in whole-mount samples like embryonic tissue [17].

Troubleshooting Strategies:

| Challenge | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Masking Signal | Endogenous biomolecules (e.g., lipids, proteins) in the tissue emit light, creating a high noise floor [17]. | Apply Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction (OMAR) via photochemical bleaching. This protocol maximally suppresses autofluorescence prior to hybridization, eliminating the need for digital post-processing [17]. |

| Non-Specific Signal | Unbound or weakly bound probes are not adequately removed during washing [16]. | Increase the stringency of post-hybridization washes by adjusting temperature and salt concentration. Optimize probe concentration and hybridization time to favor specific binding [16]. |

| Unexpected Fluorescence in Channels | Autofluorescence is often broad-spectrum, appearing in multiple detection channels [17]. | Using OMAR to quench this signal before probe application drastically improves the signal-to-noise ratio, making specific signals more distinct [17]. |

How can I improve quantitative accuracy for transcript counting?

Accurate quantification of gene expression is a key application of FISH, but several factors can introduce inaccuracy.

Troubleshooting Strategies:

| Challenge | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Faded or Variable Signal | Signal degradation due to photobleaching, over-fixation, or over-permeabilization [16]. | Use more photostable fluorophores (e.g., quantum dots, bright organic dyes) and antifade mounting media. Optimize fixation and permeabilization conditions to preserve sample integrity [16] [18]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Runs | Inter-run and inter-operator variability in manual protocols [19]. | Transition to an automated staining platform where possible. Automation standardizes incubation times, temperatures, and washing, leading to high concordance rates and improved reproducibility [19]. |

| Ambiguous Signal Localization | Use of probes that are too long or heavily labeled, causing aggregation and poor resolution [20]. | For single-molecule FISH (smFISH), use sets of short, singly-labeled oligonucleotide probes. This provides a predictable fluorophore count per transcript, enabling semi-automated quantification and resolution of individual mRNA molecules [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the single most effective method to reduce autofluorescence in whole-mount mouse embryos? A: The most effective method is Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction (OMAR). This photochemical bleaching step is performed after fixation and before hybridization. It chemically modifies the molecules responsible for autofluorescence, leading to maximal suppression and eliminating the need for digital image post-processing, which greatly improves the signal-to-noise ratio for accurate quantification [17].

Q: My FISH signal is weak or absent, even though my positive controls work. What should I check? A: Follow this diagnostic path:

- Probe & Target: Verify probe design and labeling efficiency. Ensure the target nucleic acid (DNA/RNA) has been adequately denatured to make it single-stranded and accessible [16].

- Permeabilization: This is a very common culprit. Optimize the concentration and duration of permeabilization agents (e.g., Triton X-100, proteinase K) to allow the probe to reach its target without destroying sample morphology [16].

- Hybridization Conditions: Increase the probe concentration or hybridization time. Ensure the sample does not dry out during hybridization by using a sealed, humidified chamber [16].

Q: How does automated FISH improve quantitative accuracy compared to manual methods? A: Automated platforms significantly enhance quantitative accuracy by eliminating major sources of human error and variability. They provide:

- Consistent Timing and Temperature: Precise control over denaturation, hybridization, and wash steps, which is critical for stringent and reproducible binding [19].

- Standardized Reagent Application: Uniform application of probes and wash buffers across the sample and between runs [19].

- Reduced Inter-operator Variability: The protocol is executed identically every time, leading to highly concordant results (e.g., 98% concordance reported in one validation study) and reliable data for quantitative analysis [19].

Q: Are there specific probe types that are better for precise, single-molecule quantification? A: Yes. For single-molecule FISH (smFISH), the best results are achieved using multiple short oligonucleotide probes (e.g., 20-mers), each tagged with a single fluorophore and designed to collectively span the target mRNA. This approach yields a high and predictable number of fluorophores per transcript, enabling clear discrimination of individual mRNA molecules and semi-automated quantification with image analysis software. This is superior to using a few long, multi-labeled probes which can cause self-quenching and ambiguous signal clusters [20].

Experimental Protocol: OMAR for Whole-Mount RNA-FISH

The following detailed protocol is adapted from an optimized method for whole-mount RNA-FISH on mouse embryonic limb buds, which can be adapted for other tissues and vertebrate embryos [17].

Workflow Diagram: OMAR FISH Protocol

Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Role in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde | Fixative agent that preserves tissue morphology and maintains the integrity of the target nucleic acids [16]. |

| Triton X-100 | A detergent-based permeabilization agent that creates pores in cell membranes, allowing FISH probes to access the interior of the tissue [17] [16]. |

| OMAR Bleaching Reagents | Chemical solutions (e.g., hydrogen peroxide) used in the photochemical bleaching step to oxidize and silence autofluorescent molecules within the tissue [17]. |

| Oligonucleotide FISH Probes | Short, fluorescently-labeled DNA probes designed to bind complementary mRNA sequences. Using multiple probes per transcript increases signal for detection [20]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | A solution that provides the correct salt, pH, and denaturant conditions to facilitate the annealing of the FISH probes to their target mRNA sequences [20] [16]. |

| Mounting Medium with Antifade | A solution to preserve the sample for microscopy. Antifade reagents slow down photobleaching, protecting the fluorescent signal during imaging [16]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Embryo Collection and Fixation: Collect the target tissue (e.g., mouse embryonic limb bud) and immediately fix it in a suitable fixative like 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixation preserves the tissue architecture and immobilizes the RNA targets in situ. The fixation time should be optimized to avoid over-fixation, which can reduce probe accessibility [17] [16].

Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction (OMAR): This is the critical autofluorescence quenching step. Treat the fixed samples with the OMAR bleaching reagents under controlled light exposure. This photochemical reaction effectively reduces the broad-spectrum background fluorescence that plagues whole-mount samples, thereby drastically improving the signal-to-noise ratio for subsequent FISH detection [17].

Permeabilization: Treat the samples with a permeabilization agent, such as Triton X-100. This step is essential for allowing the FISH probes to penetrate deep into the tissue and access the target mRNA. The concentration and duration of this step must be carefully balanced to ensure adequate penetration while preventing morphological damage [17] [16].

Hybridization: Incubate the permeabilized samples with the fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide FISH probes in a hybridization buffer. Use a humidified chamber to prevent evaporation and sample drying, which can cause high, non-specific background. The hybridization time and temperature are key parameters that determine the specificity of probe binding [16].

Post-Hybridization Washes: Perform a series of stringent washes after hybridization. The goal is to remove any excess, unbound probes and to wash away probes that are weakly or non-specifically bound. Adjusting the temperature and salt concentration of these washes is the primary way to control stringency and minimize background [20] [16].

Optical Clearing and Mounting: Subject the samples to an optical clearing protocol. This process reduces light scattering within the tissue, making it more transparent and significantly improving imaging depth and clarity for both 2D and 3D analysis. Mount the cleared samples in an antifade mounting medium for preservation [17].

Imaging and Analysis: Image the samples using a fluorescence microscope capable of 3D image acquisition. The OMAR-treated samples will have low background, allowing for clear detection of specific FISH signals without the need for complex digital post-processing to subtract autofluorescence [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials used in the featured OMAR-FISH protocol and their critical functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| OMAR Bleaching Kit | Critically quenches broad-spectrum tissue autofluorescence, enabling high signal-to-noise imaging without computational correction [17]. |

| Permeabilization Detergent (Triton X-100) | Creates pores in lipid membranes, allowing nucleic acid probes to penetrate deep tissue layers for target access [17] [16]. |

| Single-Molecule FISH Probe Sets | Multiple short, singly-labeled oligonucleotides provide bright, quantifiable signal by binding adjacent sites on a single mRNA molecule [20]. |

| Automated Staining Platform | Standardizes all fluidic and incubation steps, drastically reducing hands-on time and variability while ensuring consistent, high-quality results [19]. |

| Optical Clearing Reagents | Reduces light scattering within the sample, increasing imaging depth and resolution for accurate 3D analysis of whole-mount specimens [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary cause of persistent background fluorescence in aged neuronal tissues, and how can it be managed? Lipofuscin, an autofluorescent material that progressively accumulates in the brain and other tissues with age, is a primary cause of background fluorescence. This accumulation is particularly prominent in postmitotic cells like neurons. In normal aging and conditions like Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (NCL), lipofuscin granules fill the cytosol and can confound immunofluorescence studies.

- Management Strategy: The 3D-LIMPID-FISH method is an optical clearing technique compatible with FISH that uses mild aqueous conditions to preserve tissue structure and lipids while reducing light scattering. It can be combined with bleaching the tissue in H₂O₂ to eliminate autofluorescence [6] [21].

FAQ 2: How do blood components interfere with fluorescence imaging and blood cell analysis? Lipemia, or high lipid content in the blood, can cause significant interference. In sablefish studies, even a 16-18 hour fast was insufficient to reduce blood lipids, leading to visible lipemia and frequent rupture of blood cells during analysis. This can cause artifacts in hematology and possible reagent interference in plasma biochemistry. Furthermore, the choice of anticoagulant can affect blood cell counts, morphology, and leukocyte viability [22] [23].

FAQ 3: Why is organ-specific profiling crucial in whole-mount FISH studies? Gene expression is highly heterogeneous across different tissues and cell types. Quantitative analyses have shown that the abundance of specific mRNAs can vary by orders of magnitude between different anatomical regions. Therefore, profiling specific regions of interest (ROIs) is essential to understand unique cellular functions and avoid averaging out critical, region-specific expression signals [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background Autofluorescence from Lipofuscin

Problem: Strong, speckled autofluorescence in aged or diseased neuronal tissues obscures specific FISH signals. Background: Lipofuscin load increases linearly with age and at a dramatically accelerated rate (11x faster) in certain disease models like CLN1. It is primarily concentrated in the soma of neurons and glia, with stereotyped, layer-specific deposition in regions like the cortex [21].

Solution: Implement a combined approach of optical clearing and chemical bleaching.

- Recommended Protocol: 3D-LIMPID-FISH with Bleaching

- Sample Extraction: Collect your whole-mount tissue sample.

- Fixation: Fix the tissue to preserve morphology and antigenicity.

- Bleaching: Incubate the tissue in H₂O₂ to chemically reduce lipofuscin autofluorescence [6].

- Staining: Perform your standard FISH protocol with HCR probes for high signal-to-noise ratio and linear amplification [6].

- Clearing: Immerse the tissue in the LIMPID solution. This aqueous clearing solution contains saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol. The refractive index can be fine-tuned by adjusting the iohexol percentage to match your objective lens (e.g., 1.515), thereby increasing transparency and reducing aberrations for high-resolution imaging [6].

Table 1: Neuroanatomical Vulnerability to Lipofuscin Accumulation

| Neuroanatomical Region | Lipofuscin Load in 24-month WT | Lipofuscin Load in 7-month PPT1 KO (CLN1) |

|---|---|---|

| Cortex (Layer 5/6a) | High | Very High |

| Thalamus | High | Very High |

| Cerebellar Granule Layer | High | Very High |

| Hippocampal Stratum Pyramidale | Moderate | Very High |

| Ventricular System | Low | Low |

| Fiber Tracts | Low | Low |

Source: Adapted from Lipofuscin Atlas data [21].

Issue 2: Artifacts and Interference from Blood Components

Problem: Lipemia or poor sample preparation leads to ruptured blood cells, hemolysis, and unreliable data in assays or tissue imaging. Background: Blood parameters are sensitive to intrinsic and extrinsic factors like species, diet, and handling. Lipemia can be induced by insufficient fasting, while the choice of anticoagulant can directly impact cell integrity and subsequent functional assays [22] [23].

Solution: Optimize pre-sample handling and anticoagulant selection.

- Recommended Protocol: Blood Collection for Minimized Interference

- Fasting: Prior to blood collection or tissue sampling from blood-rich organs, fast the experimental subjects for 24 to 36 hours. This has been shown to sufficiently reduce blood lipids and prevent lipemia-related artifacts in fish models [22].

- Anticoagulant Selection: Choose an anticoagulant based on your downstream application. A study in rainbow trout found:

- Li-Heparin: Best for preserving hematological count, cell morphology, and minimizing ROS production. It did not negatively affect phagocytosis ability of leukocytes and showed no hemolysis [23].

- K3EDTA: Caused lower leukocyte viability, higher levels of apoptosis, and increased ROS levels compared to other anticoagulants [23].

- ACD-A: Showed intermediate performance and is known to be effective for leukocyte functional studies in other vertebrates [23].

Table 2: Effect of Anticoagulants on Rainbow Trout Blood Parameters

| Parameter | Li-Heparin | K3EDTA | ACD-A |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrocyte/Thrombocyte Count | Reference | Significant differences | Significant differences |

| Hemolysis | None | Present | Present |

| Leukocyte Viability | High | Lower | Intermediate |

| ROS Production in Myeloid Cells | Low | High | Low |

| Impact on Phagocytosis | No negative effect | Not the best choice | Not the best choice |

Source: Data synthesized from [23].

Issue 3: Achieving High-Resolution, Organ-Specific Gene Expression Profiles

Problem: Low-resolution imaging of whole organisms fails to capture critical subcellular or tissue-specific expression patterns.

Background: Conventional low-magnification imaging of whole mount samples sacrifices detail. Quantitative analyses reveal that gene expression can be highly enriched in specific regions; for example, calb1 mRNA is 84 times more abundant in the mouse dentate gyrus (DG) than in the CA3 region [24].

Solution: Employ a smart imaging workflow that combines automated microscopy with feature detection.

- Recommended Protocol: Automated Smart Microscopy for Organ-Zooming

- Sample Mounting: Consistently orient specimens in agarose-filled microplates using 3D-printed orientation tools to standardize data acquisition [25].

- Pre-scan: Acquire low-resolution overview images (e.g., with a 4x objective) of the entire specimen [25].

- Feature Detection: Use algorithms (e.g., in Fiji) to automatically detect the XY-coordinates of your fluorescently labeled region of interest (ROI), such as the pronephros in zebrafish or a hippocampal subregion [25] [24].

- Re-scan: The software sends instructional feedback to the microscope to reposition the high-magnification objective (e.g., 63x oil) over the ROI and acquire a high-resolution z-stack [6] [25]. This "pre-scan/re-scan" procedure allows for the automated capturing of standardized, high-resolution datasets from specific tissues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Tissue-Specific FISH

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| LIMPID Solution | A hydrophilic, aqueous optical clearing agent that enables deep-tissue imaging via refractive index matching. | Clearing whole-mount tissues for 3D FISH; preserves lipids and is compatible with antibody and FISH probes [6]. |

| HCR FISH Probes | Fluorescent in situ hybridization probes that use Hybridization Chain Reaction for linear signal amplification, providing high sensitivity and quantifiability. | Detecting mRNA with single-molecule resolution; ideal for quantifying gene expression in specific ROIs [6]. |

| 3D-Printed Orientation Tools | Creates agarose cavities in microplates for consistent and automated positioning of whole-mount specimens. | Essential for high-throughput, automated imaging of zebrafish embryos or other small model organisms [25]. |

| Li-Heparin Anticoagulant | Preserves blood cell morphology and viability for functional immune assays and minimizes hemolysis. | Collecting blood samples for subsequent flow cytometry or microscopy analysis in fish and other animals with nucleated erythrocytes [23]. |

| "Carrier RNA" | A designed RNA with no sequence homology to the studied organism, used to prevent adsorption of nucleic acids to plastic surfaces. | Critical for accurate RT-qPCR from laser-microdissected samples to avoid loss of ultra-micro quantities of mRNA [24]. |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow 1: 3D-LIMPID-FISH for Whole-Mount Tissues

Diagram Title: 3D-LIMPID-FISH Experimental Workflow

Workflow 2: Smart Imaging for Organ-Specific Profiling

Diagram Title: Automated Smart Imaging Pipeline

Pathway 1: Lipofuscin Accumulation in Aging and Disease

Diagram Title: Lipofuscin Biogenesis and Impact Pathway

Practical Quenching Protocols: Chemical Agents, Optical Clearing, and Integrated Workflows

In whole mount fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), autofluorescence can significantly compromise data interpretation by masking specific signals. This technical support center details the use of three primary quenching agents—TrueBlack Lipofuscin Quencher, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Sudan Black B—to mitigate this issue. The following guides and FAQs provide targeted protocols and troubleshooting advice to help researchers select and optimize the correct quenching method for their experimental context, particularly within whole mount specimens.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents used to quench autofluorescence in fluorescence imaging.

| Reagent Name | Primary Function | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin AF Quencher [26] [27] | Quenches lipofuscin autofluorescence; also reduces background from collagen, elastin, and red blood cells. | Superior to Sudan Black B with less far-red background; can be used before or after immunofluorescence staining; effective on human and aged animal tissues. |

| TrueBlack Plus Lipofuscin AF Quencher [26] | Next-generation lipofuscin quencher. | Even lower far-red background than original TrueBlack; can be used in aqueous buffer, allowing longer incubations for thick tissues without shrinkage. |

| Sudan Black B [26] [28] | Traditionally used to quench lipofuscin autofluorescence. | A lipophilic dye; can introduce uniform non-specific background fluorescence in the red and far-red channels. |

| ReadyProbes Tissue Autofluorescence Quenching Kit [29] | Minimizes autofluorescence from aldehyde fixation, red blood cells, collagen, and elastin. | Does not quench natural pigments or other autofluorescent entities; components must be mixed in a specific order. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [28] | A bleaching agent used to reduce autofluorescence from various sources, including endogenous pigments. | Often used to treat tissues with high levels of endogenous pigments; requires careful optimization of concentration and time to avoid tissue damage. |

Quantitative Data Comparison of Quenching Agents

For informed experimental design, the following table compares critical quantitative data for the featured quenching agents.

| Agent | Recommended Working Concentration / Dilution | Recommended Incubation Time | Key Stability & Safety Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrueBlack (20X in DMF) [26] | 1X (diluted from 20X stock) | Not specified; described as "rapid". | Original formulation. Safety: Contains DMF, which is rapidly absorbed through skin and lungs and may harm the unborn child. Wear personal protective equipment [27]. |

| TrueBlack (30X in DMSO) [26] | 1X (diluted from 30X stock) | Not specified; described as "rapid". | More concentrated; uses DMSO, a less toxic solvent than DMF. |

| TrueBlack Plus [26] | As per manufacturer's instructions. | Can be extended for thick tissues. | Formulated for use in aqueous buffer. |

| Sudan Black B [28] | 0.1% - 0.3% (w/v) in 70% ethanol. | 10 - 30 minutes. | Stable solution can be stored at room temperature for several months. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide [28] | 1% - 3% (v/v) in PBS or distilled water. | 30 minutes to 2 hours; requires optimization. | Unstable; prepare fresh before use. Degrades rapidly in the presence of light, heat, and organic material. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quenching with TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher

This protocol is adapted for use on tissue sections, including whole mount specimens, and can be performed either before or after immunofluorescence or FISH staining [26].

- Preparation of Working Solution: Dilute the TrueBlack stock solution (either 20X in DMF or 30X in DMSO) in the appropriate volume of 70% ethanol to create a 1X working solution. For example, to make 1 mL of 1X solution, use 50 µL of 20X stock with 950 µL of 70% ethanol.

- Application: Apply enough TrueBlack 1X working solution to completely cover the tissue sample.

- Incubation: Incubate at room temperature for the desired time. The process is rapid, but optimal time should be determined empirically (e.g., start with 2-5 minutes). For thick whole mount samples using TrueBlack Plus, longer incubation times are possible as it is compatible with aqueous buffers [26].

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the sample several times with PBS or your chosen buffer to remove the quenching solution.

- Mounting and Imaging: Proceed with mounting the sample and imaging.

Protocol 2: Quenching with Sudan Black B

This traditional method is typically performed after immunofluorescence staining [26] [28].

- Preparation of Staining Solution: Prepare a 0.1% to 0.3% (weight/volume) solution of Sudan Black B in 70% ethanol. Filter the solution if necessary to remove any undissolved particles.

- Application: Cover the stained tissue sample with the Sudan Black B solution.

- Incubation: Incubate at room temperature for 10 to 30 minutes.

- Differentiation and Rinsing: Rinse the sample extensively with 70% ethanol followed by PBS or your chosen buffer to remove excess dye and reduce background.

- Mounting and Imaging: Proceed with mounting the sample and imaging. Be aware that Sudan Black B can introduce non-specific background fluorescence in the red and far-red channels [26].

Protocol 3: Bleaching with Hydrogen Peroxide

This method is useful for reducing autofluorescence from various endogenous pigments, such as those in red blood cells [28].

- Preparation of Working Solution: Prepare a fresh 1% to 3% solution of hydrogen peroxide in PBS or distilled water. Note: Higher concentrations may damage tissue and require extensive optimization.

- Application: Incubate the tissue sample in the hydrogen peroxide solution.

- Incubation: Incubate at room temperature, protected from light, for 30 minutes to 2 hours. Monitor the reduction of autofluorescence closely.

- Termination and Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the sample multiple times with PBS to terminate the reaction and remove all traces of hydrogen peroxide.

- Proceed with Staining: The sample is now ready for subsequent staining procedures.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Can TrueBlack be used to quench autofluorescence from sources other than lipofuscin? Yes. While TrueBlack is exceptionally effective at quenching lipofuscin, it can also reduce general background fluorescence and autofluorescence from other sources, such as collagen, elastin, and red blood cells. However, it may not be as effective for these non-lipofuscin sources as it is for lipofuscin itself [26] [27].

Q2: What is the key difference between TrueBlack and Sudan Black B? The primary difference is in the background signal. TrueBlack quenches lipofuscin fluorescence with far less increase in red and far-red background fluorescence compared to Sudan Black B. This makes TrueBlack a superior choice when using fluorescent dyes in these wavelengths [26].

Q3: I am working with thick whole mount samples. Which quenching agent is best suited for longer incubation times? TrueBlack Plus is specifically designed for this application. It is the only lipofuscin quencher that can be used in aqueous buffer instead of 70% ethanol, which allows for longer incubation times without causing tissue shrinkage [26].

Q4: My negative control (no primary antibody) still shows fluorescence after quenching. What could be the cause? The ReadyProbes Tissue Autofluorescence Quenching Kit product information clarifies that not all autofluorescence is quenched by a single reagent. Their kit, for example, minimizes autofluorescence from aldehyde fixation, red blood cells, collagen, and elastin, but will not quench natural pigments or other autofluorescent entities [29]. It is critical to identify the source of autofluorescence in your specific tissue and choose the quenching method accordingly.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background in Red/Far-Red Channel | Use of Sudan Black B, which fluoresces in these channels [26]. | Switch to TrueBlack or TrueBlack Plus, which offer lower far-red background. |

| Weak Specific Signal After Quenching | Over-quenching; the quenching agent may be causing a decrease in the specific antibody or FISH signal [27]. | Titrate the concentration and incubation time of the quenching agent. Ensure it is compatible with your specific antibodies and probes. |

| Ineffective Quenching | The wrong quenching agent was selected for the source of autofluorescence [29]. | Identify the primary source of autofluorescence in your tissue (e.g., lipofuscin, RBCs, aldehydes) and select a targeted reagent. |

| Tissue Damage or Shrinkage | Use of hydrogen peroxide at too high a concentration or for too long; use of alcohol-based quenchers on delicate whole mounts [26] [28]. | For H₂O₂, optimize concentration and time on test samples. For delicate samples, consider TrueBlack Plus in aqueous buffer. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making pathway for selecting and applying an autofluorescence quenching agent in a whole mount FISH experiment.

Diagram 1: Decision pathway for selecting an autofluorescence quenching method.

The diagram below outlines the core signaling pathway involved in one of the key models used to study cell motility, which is relevant to the zebrafish WHIM syndrome model discussed in the search results [30].

Diagram 2: CXCR4-SDF1 signaling pathway in normal and WHIM mutation contexts.

This technical support guide details the LIMPID (Lipid-preserving Index Matching for Prolonged Imaging Depth) methodology, an advanced optical clearing technique. Framed within a broader thesis on quenching autofluorescence in whole-mount FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) research, this resource provides troubleshooting and procedural support for scientists. LIMPID enables high-resolution three-dimensional imaging of thick tissues by matching refractive indices to reduce light scattering while preserving lipids and fluorescent signals [31] [6] [32]. Its compatibility with RNA FISH, immunohistochemistry, and conventional fluorescence microscopy makes it a versatile tool for researchers and drug development professionals investigating complex 3D gene and protein expression patterns [31] [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents used in the 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol, along with their specific functions.

| Reagent Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Tissue fixation to preserve structure and biomolecules [33]. |

| Urea | A key component of the clearing solution, it contributes to tissue transparency [6] [33]. |

| Nycodenz/Iohexol | A contrast medium that adjusts the refractive index of the LIMPID solution to match that of high-NA objective lenses (e.g., ~1.515) [6] [33]. |

| SSC Buffer | A saline-sodium citrate buffer used in hybridization and washing steps for FISH, and as a base for SSC-LIMPID solutions [33]. |

| Formamide | A component in hybridization buffers that can be added to increase fluorescence intensity in FISH protocols [6]. |

| H2O2 (Hydrogen Peroxide) | Used for chemical bleaching of the tissue to reduce inherent autofluorescence [6]. |

| HCR Probes | Fluorescent in situ hybridization probes that utilize the Hybridization Chain Reaction for signal amplification, allowing for single-molecule RNA detection [6]. |

| DAPI | A fluorescent stain that binds to DNA, used for nuclear counterstaining [33]. |

LIMPID Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core procedural steps for the 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol, from sample preparation to final imaging.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common LIMPID-FISH Issues and Solutions

Problem: Incomplete Tissue Clearing

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Insufficient incubation time in LIMPID solution. Solution: Increase clearing time. Smaller tissues (e.g., stage 20 quail embryos) may clear in 10 minutes, while larger ones (e.g., stage 36 quail brains) may require 24 hours [32].

- Cause 2: Incorrect refractive index of the LIMPID solution. Solution: Calibrate the solution using an Abbe refractometer. Adjust the refractive index by adding Nycodenz powder to increase it (up to ~1.57) or 50% (w/w) urea solution to decrease it (down to ~1.41) to match your objective lens [6] [33].

- Cause 3: The solution has crystallized due to evaporation. Solution: Ensure the solution is stored in a sealed container and avoid heating above 40°C during preparation. If crystals form, gently warm and add a small amount of water to redissolve [33].

Problem: High Background Autofluorescence

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inherent tissue autofluorescence from components like lipofuscin, red blood cells, or collagen. Solution: Incorporate a bleaching step with H₂O₂ during sample preparation [6]. For persistent lipofuscin, consider a specialized quencher like TrueBlack applied before or after immunostaining [34].

- Cause 2: Autofluorescence from aldehyde fixation. Solution: Ensure the concentration and fixation time are optimized. Over-fixation can increase autofluorescence and reduce FISH signals [6].

- Cause 3: Nonspecific binding of probes. Solution: Use HCR probes with split initiator designs for high specificity and low background [6]. Optimize hybridization and wash buffer stringency.

Problem: Weak or Lost FISH Signal

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: RNA degradation. Solution: Ensure all equipment and surfaces are treated with RNase decontamination reagents to prevent RNA degradation [33].

- Cause 2: Over-fixation. Solution: Reduce fixation time or introduce a protease treatment step to free up cross-linked molecules for better probe access [6].

- Cause 3: Probe leakage during clearing. Solution: The protocol is designed to minimize signal loss. However, ensure that the HCR amplification step is performed correctly and that the stained tissue is imaged within a week of amplification to preserve signal integrity [6].

Problem: Bubbles in Tissue or Mounting Medium

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Agitation or rapid mixing of solutions. Solution: During all incubation and mounting steps, handle samples gently to avoid introducing bubbles. If bubbles form during mounting, carefully press them away from the tissue with a fine tool [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of LIMPID Clearing Solution

The LIMPID solution is a key reagent for refractive index matching. The following diagram illustrates the two primary preparation paths.

Protocol: [33]

Prepare Base Solution:

- For H₂O-LIMPID, use 200 g of deionized MilliQ water.

- For SSC-LIMPID (used in FISH-compatible protocols), prepare 200 g of 2x or 5x SSC buffer.

Add Urea: Transfer the 200 g of base solution to a glass beaker. Weigh out 200 g of urea powder and gently add it to the beaker to create a ~50% (w/w) urea solution.

- Add a magnetic stir bar.

- Heat to 60°C with stirring until the urea is fully dissolved and the solution is transparent.

- Cool the solution.

Add Iohexol (Nycodenz): Transfer 300 g of the 50% urea solution to a new beaker. Weigh out 200 g of Nycodenz powder and add it to the beaker (resulting in a 2:3 ratio of iohexol to urea solution).

- Heat to 60°C and stir gently until all powder is dissolved. Note: This can take 3-6 hours.

- To prevent evaporation, wrap the beaker with parafilm. The solution can be left to dissolve overnight at room temperature.

Calibrate Refractive Index (RI):

- Use an Abbe refractometer to measure the RI of a small sample (~50 µL).

- The target RI depends on your microscope objective (e.g., 1.515 for a typical oil immersion lens) [6].

- To increase RI: Add more Nycodenz powder.

- To decrease RI: Add more 50% (w/w) urea solution.

- Use the calibration curve in the supplementary materials of the main protocol for rough estimates [33].

Whole-Mount 3D-LIMPID-FISH Protocol

Procedure: [6]

Sample Extraction and Fixation:

- Extract fresh tissue samples and fix them in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C overnight. Note: Fixation conditions should be optimized for specific tissue sizes and types.

Bleaching (Optional but Recommended):

- To quench tissue autofluorescence, bleach samples in H₂O₂. This step is crucial for improving the signal-to-noise ratio [6].

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH):

- Hybridization: Incubate the fixed tissue with custom-designed HCR FISH probes in a hybridization buffer containing formamide.

- Washing: Remove unbound probes with multiple washes using a dedicated wash buffer.

- Amplification: Initiate the HCR amplification reaction by adding fluorescently labeled hairpin DNA to the tissue. For single-molecule resolution, limit the amplification time (e.g., 2 hours) [6].

Immunohistochemistry (Optional Co-staining):

Optical Clearing with LIMPID:

- Immerse the stained tissue sample in excess LIMPID solution.

- Incubate until the tissue is transparent. The time varies with tissue size (minutes for small embryos to hours for larger tissues) [32].

- The tissue is now ready for imaging.

3D Microscopy:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes LIMPID different from other optical clearing methods? LIMPID is a simple, single-step, aqueous clearing method that preserves lipids. Unlike methods that remove lipids (which can be time-consuming and destroy structures) or use harsh organic solvents (which can shrink tissue and quench fluorescence), LIMPID uses a mild, water-soluble solution to match refractive indices. This preserves fluorescent signals from proteins, genetic reporters, and FISH probes while maintaining tissue morphology [31] [32].

Q2: Is LIMPID compatible with whole-mount tissues from animal models other than mice? Yes. A key advantage of LIMPID-FISH is the ease of creating custom FISH probes. The protocol has been successfully demonstrated with quail embryos, proving its utility for less common animal models where commercial antibody probes may not be readily available [31] [6].

Q3: Do I need a confocal or light-sheet microscope to use LIMPID? No. While LIMPID enables excellent imaging on advanced systems like confocal microscopes, it has also been shown to produce high-quality 3D images using conventional fluorescence microscopes. This makes the technique more accessible to labs without specialized imaging equipment [31].

Q4: What are the primary methods for reducing autofluorescence in whole-mount FISH? Within the LIMPID-FISH workflow, chemical bleaching with H₂O₂ is integrated as a standard step [6]. For particularly stubborn autofluorescence, especially from lipofuscin, additional treatments with dedicated quenching reagents like TrueBlack can be highly effective [34]. Alternatively, advanced photobleaching devices using high-power LEDs have been developed for highly efficient autofluorescence quenching while minimizing tissue damage [35].

Q5: Can the LIMPID protocol be combined with immunohistochemistry? Absolutely. A significant strength of the LIMPID method is its compatibility with co-labeling using antibody-based immunohistochemistry (IHC) and FISH probes. This allows researchers to concurrently visualize protein localization and mRNA expression within the same 3D tissue sample [31] [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Can HCR be combined with immunofluorescence (IF) for simultaneous RNA and protein detection? Yes, HCR provides a unified framework for multiplexed RNA and protein imaging. The amplifiers (e.g., B1, B2, B3 or X1, X2, X3) and amplification buffers are interchangeable between HCR RNA-FISH and HCR IF kits. For a multiplex experiment, you would use a distinct HCR amplifier and fluorophore for each target RNA and each target protein [36] [37] [38].

Q2: What is the key advantage of using HCR over enzyme-based amplification methods like CARD-FISH? HCR offers several key advantages: it is an enzyme-free, isothermal amplification method that provides quantitative signal, preserves subcellular resolution, and enables straightforward multiplexing. Unlike CARD-FISH, which can suffer from signal diffusion and requires lengthy serial staining for multiple targets, HCR allows for simultaneous one-step amplification of all targets without compromising resolution or requiring sample degradation [39].

Q3: How can I reduce high autofluorescence in whole-mount samples before HCR-FISH? The OMAR (Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction) protocol is highly effective. It involves a photochemical bleaching step using high-intensity cold white light (e.g., high-power LED spotlights) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and a basic solution. This treatment significantly reduces or eliminates tissue autofluorescence at the source, prior to hybridization, alleviating the need for extensive digital post-processing [2].

Q4: What are the simplest ways to boost a weak HCR signal? For optimal signal strength, consider the following adjustments:

- Increase Probe Concentration: For HCR v3.0, increasing the probe concentration from 4 nM to 20 nM is recommended [40].

- Extend Incubation Times: Implementing overnight incubations for both probe hybridization and amplification can significantly improve signal, especially in thicker samples [40].

- Use a Boosted Probe: If the target sequence is long enough, ordering a probe set with more initiator pairs (e.g., 30 or more) increases the number of binding sites and enhances signal [36] [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Problem: Poor or No Signal

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Low-abundance target RNA | Use a boosted probe set with more initiator pairs (e.g., 30+ for dHCR imaging) [36]. |

| Inefficient hybridization/amplification | Increase probe concentration to 20 nM (for v3.0) and extend incubation times to overnight [40]. |

| Low signal in autofluorescent samples | Switch to a longer-wavelength fluorophore (e.g., 647 nm or 750 nm) where autofluorescence is typically lower [37]. For ultimate sensitivity, consider HCR Pro [40]. |

| Inefficient sample permeabilization | Optimize permeabilization conditions (e.g., concentration of Triton X-100, time, temperature) to balance probe access with morphology preservation [16]. |

Problem: High Background or Non-Specific Signal

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Sample autofluorescence | Implement the OMAR photochemical bleaching protocol prior to hybridization [2]. |

| Non-specific probe binding | Increase the stringency of post-hybridization washes (e.g., adjust temperature, salt concentration) [16]. |

| Probe adsorption to abiotic particles (in environmental samples) | Modify hybridization buffer recipes and combine with sample pre-treatment methods (e.g., detachment, extraction) developed for complex samples like sediments [41]. |

| Incomplete removal of unbound probes | Ensure stringent post-hybridization washes are performed completely. Avoid shortened wash times [16]. |

Problem: Morphological Distortion or Cell Damage

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Over-fixation | Optimize fixation conditions (e.g., paraformaldehyde concentration and time) to preserve nucleic acid integrity while maintaining morphology [16]. |

| Over-permeabilization | Titrate permeabilization agents (e.g., Triton X-100, proteinase K) to prevent damage to cellular structures [16]. |

Workflow Diagram: Integrated FISH-HCR with Autofluorescence Quenching

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow for combining whole-mount FISH with HCR amplification and autofluorescence quenching.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their functions for implementing integrated FISH-HCR protocols with autofluorescence quenching.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| HCR HiFi Probe Sets | DNA probes designed to bind target mRNA; they contain initiator sequences that trigger the HCR amplification [37]. |

| HCR Gold Amplifiers | Fluorophore-labeled DNA hairpins that self-assemble into amplification polymers upon initiation, providing the detected signal [37]. |

| OMAR Solution (H₂O₂/NaOH) | A chemical mixture used in the photochemical bleaching step to oxidize and reduce endogenous fluorophores responsible for autofluorescence [2]. |

| High-Intensity LED Light Source | A critical hardware component for the OMAR protocol, providing the light energy required to drive the oxidative bleaching reaction [2]. |

| Probe Hybridization & Wash Buffers | Formulated solutions to create optimal conditions for specific probe binding and to remove unbound/non-specifically bound probes, minimizing background [37] [40]. |

| Permeabilization Agent (e.g., Triton X-100) | A detergent that disrupts lipid membranes to allow probes and amplifiers to access intracellular targets [2] [16]. |

| Cellular Counterstains (e.g., DAPI, SR2200) | Fluorescent dyes that label nuclei (DAPI) or cell walls (SR2200) to provide anatomical context and facilitate single-cell analysis [41] [42]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting for Whole-Mount FISH

Q1: How can I reduce high background autofluorescence in my whole-mount embryonic tissues? High background is a common issue, often caused by sample autofluorescence or non-specific probe binding. To resolve this:

- Optimize Wash Stringency: Increase the temperature or reduce the salt concentration in your post-hybridization wash buffers. Using a washing solution containing DMSO and Triton X-100 can improve stringency [43].

- Employ Quenching Techniques: For highly autofluorescent species, specific fluorescence quenching protocols using LED illumination can be effective [44].

- Verify Probe Specificity: Check for any cross-reactivity of your probe with non-target sequences [16].

- Review Fixation: Avoid over-fixation with PFA, as this can increase autofluorescence and reduce target accessibility [16].

Q2: I am getting a weak or absent signal from dense 3D organ samples. What should I do? Poor signal penetration is a key challenge in 3D samples.

- Enhance Permeabilization: Ensure adequate permeabilization by optimizing the concentration, time, and temperature for agents like Triton X-100 or Proteinase K [16].

- Use Signal Amplification: Consider using the Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) FISH technique, which employs fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins to amplify the signal [45] [44].

- Check Clearing Efficacy: For whole-mount samples, ensure your clearing solution (e.g., ScaleS4) has been properly prepared and applied to make the sample transparent for light penetration [43].

- Increase Hybridization Time: A longer hybridization time may be necessary for probes to fully diffuse into thick tissues [16].

Q3: My samples show morphological distortion after the FISH procedure. How can I preserve tissue integrity? This often results from harsh processing conditions.

- Gentle Handling: Use gentler methods for tissue dissection and handling [16].

- Optimize Fixation and Permeabilization: Avoid over-fixation and over-permeabilization, which can damage cell structures. Standardize the timing and concentration of these steps [16].

- Use Humidified Chambers: Prevent sample drying during hybridization and incubation steps by using a properly sealed humidified chamber [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence and Clearing for 3D Organ Imaging

This optimized protocol for adult zebrafish spinal cords can be adapted for other 3D tissues like embryonic tissues and organs [43].

Key Resources

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit anti-GFP | Invitrogen | Cat# A6455 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG | Invitrogen | Cat# A11008 |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#8.18715 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T8787 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | VWR | Cat#VWRC0231 |

| Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | NZYtech | Cat#MB04602 |

| D-Sorbitol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#S6021 |

| Urea | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#U1250 |

Methodology

- Dissection and Fixation: Dissect the target tissue (e.g., spinal cord) and fix immediately in 4% PFA at room temperature [43].

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Permeabilize tissues with a washing solution (1X PBS, 1% DMSO, 0.2% Triton X-100). Block non-specific sites with a whole-mount blocking solution (washing solution supplemented with 1% BSA) [43].

- Antibody Staining: Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., Rabbit anti-GFP at 1:500) diluted in blocking solution, followed by extensive washing. Then incubate with a fluorescently-labeled secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG at 1:500–1,000) [43].

- Nuclear Labeling (Optional): Counterstain nuclei with DAPI or TO-PRO-3 iodide (1:1,000) [43].

- Tissue Clearing:

- Prepare ScaleA2 solution by dissolving urea in Milli-Q water, then adding glycerol and Triton X-100 [43].

- Prepare ScaleS4 solution by separately dissolving D-sorbitol (using gentle microwave heating) and urea (below 30°C) in Milli-Q water. Cool both to room temperature before mixing, then add glycerol, Triton X-100, and DMSO. Store at 4°C [43].

- Immerse the stained samples in ScaleS4 solution until they become transparent [43].

- Mounting and Imaging: Mount the cleared samples in ScaleS4 solution and image using a light sheet or confocal microscope [43].

Protocol 2: Addressing Autofluorescence via Fluorescence Quenching

This method is applicable to autofluorescent tissue sections, including neuronal and organ samples [44].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare tissue sections using standard histological methods.

- Quenching Treatment: Apply an LED illumination-based fluorescence quenching protocol tailored to the specific tissue type. The exact parameters (wavelength, duration) should be optimized for your sample [44].

- Proceed with FISH: After the quenching step, continue with your standard FISH or HCR FISH protocol [44].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling

Whole-Mount FISH & Clearing

Autofluorescence Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Whole-Mount FISH and Autofluorescence Quenching

| Reagent | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue morphology and nucleic acid integrity [43]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent used to permeabilize cell and tissue membranes, allowing probe access [43] [16]. |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Added to washing and clearing solutions to enhance reagent penetration into thick tissues [43]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used in blocking solutions to adsorb to and "block" non-specific binding sites, reducing background [43]. |

| Urea & Glycerol | Key components of Scale clearing solutions; they work together to reduce light scattering and render tissues transparent [43]. |

| D-Sorbitol | A component of the ScaleS4 clearing solution that helps match the refractive index of the tissue to the imaging medium [43]. |

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) Kits | A signal amplification method that uses DNA hairpins to dramatically enhance FISH signal, improving detection [45] [44]. |

| LED Quenching Systems | Specialized systems designed to reduce inherent tissue autofluorescence through targeted illumination prior to FISH staining [44]. |

This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for whole-mount RNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH), with a special emphasis on quenching tissue autofluorescence—a major challenge in fluorescence-based analysis. The following workflows, timetables, and troubleshooting FAQs are designed to help researchers and drug development professionals reliably obtain high-quality results from sample collection to final imaging.

■ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most effective method to reduce tissue autofluorescence before FISH? The most effective pre-treatment method is Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction (OMAR). This photochemical bleaching technique uses a high-intensity cold white light source, such as high-power LED spotlights or LED daylight panels (e.g., 20,000 lumen), to oxidize and bleach autofluorescent compounds in the tissue. This protocol consistently reduces and often eliminates tissue and blood vessel autofluorescence, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio for both whole-mount RNA-FISH and immunofluorescence. It alleviates the need for digital post-processing to remove autofluorescence [2].

Q2: My tissue is not permeabilizing effectively for probe penetration. What should I check? Ineffective permeabilization is often related to the fixation method. First, verify that you are using a detergent-based permeabilization step after the OMAR treatment. Second, ensure your sample is not over-fixed, as this can cause excessive cross-linking that impedes probe entry. The recommended fixation in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 hours at 4°C provides a good balance between tissue morphology preservation and permeability [2] [46].

Q3: What is a critical stop point where I can safely pause my experiment? A critical and safe stopping point is after the sample fixation and methanol dehydration steps. Following fixation and rinses, you can transfer your samples to 100% methanol and store them at -20°C for several weeks without degradation [2].

■ Troubleshooting Guide

The table below outlines common issues encountered during the whole-mount FISH workflow, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Autofluorescence | Incomplete OMAR bleaching; endogenous fluorophores (e.g., from blood vessels) [2]. | Ensure successful oxidation reaction (appearance of bubbles during treatment); validate LED light source efficacy in a test series [2]. |

| Poor or No Target Signal | Ineffective tissue permeabilization; degraded RNA probes; over-fixation [2] [47]. | Optimize detergent-based permeabilization step; check probe integrity and hybridization conditions; avoid prolonged fixation times [2]. |

| Tissue Morphology Damage | Over-digestion during proteinase treatment; physical damage during handling [46]. | Titrate proteinase K concentration and incubation time; handle samples gently with flame-rounded Pasteur pipettes to avoid damage [46]. |

| Uneven Staining or Imaging | Incomplete optical clearing; sample not properly immobilized for imaging [2]. | Follow the optical clearing protocol after RNA-FISH; ensure proper mounting of the sample for 2D and 3D image analysis [2]. |

■ Step-by-Step Protocol & Timetable

The following table provides a complete workflow from embryo collection to imaging, with estimated durations and critical stop points [2].

| Step | Procedure | Duration | Critical Stop Points & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Collection & Fixation | Collect tissue (e.g., mouse embryonic limb buds) and fix immediately in 4% PFA. | ~24 hours | Critical Stop Point: After fixation, samples can be dehydrated in 100% methanol and stored at -20°C for several weeks [2]. |

| 2. OMAR Treatment | Perform photochemical bleaching in a controlled environment using a high-intensity LED light source. | ~4-6 hours | Monitor for the appearance of bubbles, which indicates a successful oxidation reaction [2]. |

| 3. Permeabilization | Treat tissue with a detergent-based solution (e.g., containing Tween-20) to enable probe entry. | ~2-4 hours | Optimization may be required for different tissues. Over-permeabilization can damage morphology [2]. |

| 4. RNA-FISH (HCR) | Hybridize with RNA probes, followed by washes and signal amplification using the HCR v3.0 system. | ~2 days | The HCR system is highly sensitive and reduces the number of embryos needed, aligning with 3R principles [2]. |

| 5. Optical Clearing | Render the sample transparent to reduce light scattering for deep-tissue imaging. | ~1-2 days | This step is crucial for high-quality 2D and 3D image analysis [2]. |

| 6. Imaging & Analysis | Mount samples and perform microscopy (e.g., confocal). Analyze images with software like ImageJ/Fiji or Imaris. | ~1 day | The protocol eliminates the need for post-processing to remove autofluorescence [2]. |

| Total Estimated Time | ~6-7 days |

■ Experimental Workflow Diagram

The diagram below visualizes the key stages of the whole-mount FISH protocol.

■ The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and their functions for the successful execution of the whole-mount FISH protocol with autofluorescence quenching.

| Reagent | Function in the Protocol | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative | Preserves tissue morphology and stabilizes RNA for detection. A 4% solution is standard [2] [46]. |

| OMAR Solutions | Photochemical autofluorescence quenching | Utilizes hydrogen peroxide under high-intensity LED light to oxidize and bleach autofluorescent compounds [2]. |

| Detergents (Tween 20, Triton X-100) | Tissue permeabilization | Creates pores in tissue membranes, allowing FISH probes and amplifiers to enter cells [2]. |

| HCR v3.0 Probes & Amplifiers | RNA target detection and signal amplification | A proprietary, multiplexable system from Molecular Instruments for highly sensitive RNA detection with low background [2]. |

| Methanol | Dehydration and storage | Used for dehydrating samples after fixation. 100% Methanol at -20°C provides a stable medium for long-term sample storage [2]. |

| Optical Clearing Reagents | Tissue transparency | Reduces light scattering for improved deep-tissue imaging, often involving fructose/glycerol-based solutions [2]. |

Troubleshooting Autofluorescence Quenching: Optimization Strategies and Problem Resolution

In whole mount fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) research, autofluorescence presents a significant barrier to accurate signal interpretation. This technical support guide addresses the critical challenge of diagnosing insufficient quenching, a common issue that can compromise experimental validity. Autofluorescence arises from various endogenous sources, including aldehyde fixation, red blood cells, structural elements like collagen and elastin, and lipofuscin granules [29] [34]. When quenching is inadequate, this background signal can obscure specific FISH signals, leading to imaging artifacts and erroneous data analysis. This guide provides researchers with systematic troubleshooting methodologies to identify, address, and prevent these issues, thereby ensuring the reliability of whole mount FISH experiments in drug development and basic research contexts.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Imaging Artifacts and Solutions

Problem: Persistent Background Fluorescence After Quenching

Description: Researchers observe broad-spectrum background fluorescence that interferes with signal detection, even after standard quenching protocols.

Diagnosis:

- Identify the source of autofluorescence by examining emission spectra.

- Aldehyde-induced fluorescence from fixation typically appears in blue-green wavelengths [34].

- Lipofuscin displays broad emission from green to far-red [34].