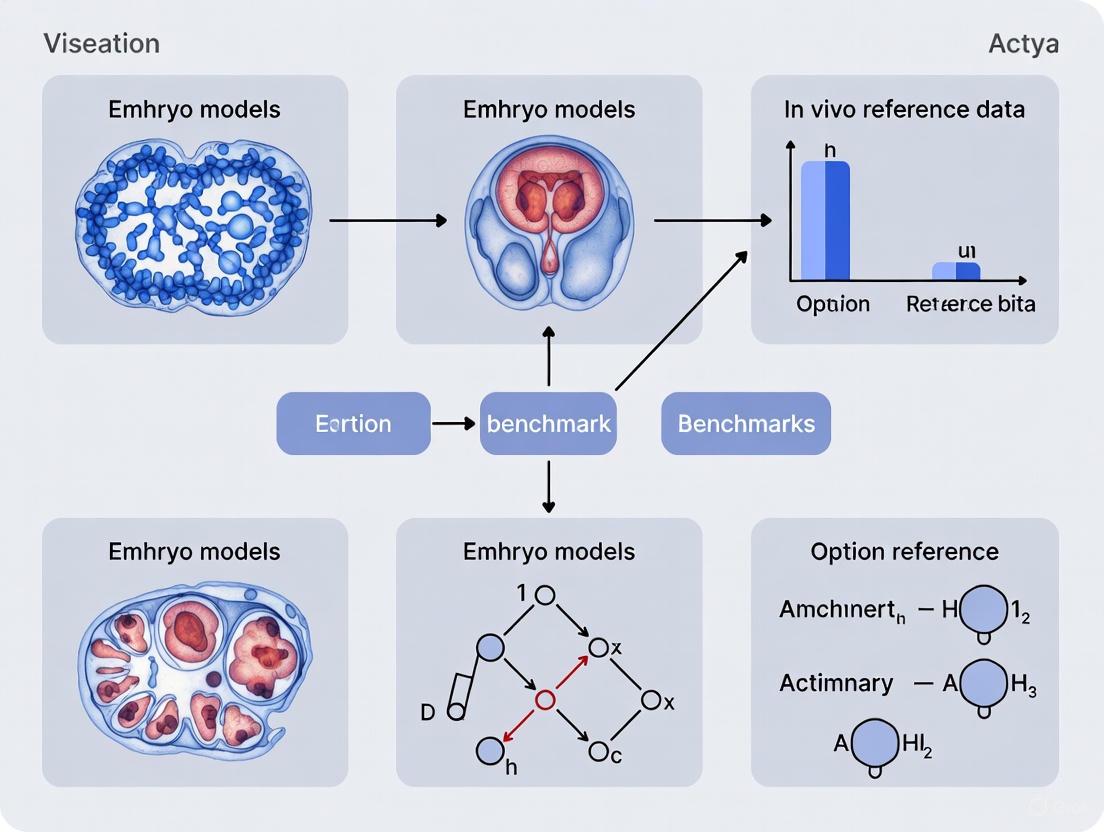

Benchmarking Human Embryo Models: Validating Fidelity Against In Vivo References for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to authenticate stem cell-based human embryo models.

Benchmarking Human Embryo Models: Validating Fidelity Against In Vivo References for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to authenticate stem cell-based human embryo models. It covers the foundational biology of early human development, current methodologies for model generation, and the critical application of single-cell RNA-sequencing reference tools for benchmarking. The content addresses common pitfalls in model validation, outlines optimization strategies, and synthesizes how rigorous benchmarking ensures these models are biologically meaningful for studying developmental disorders, improving assisted reproductive technologies, and conducting teratogen screening.

Understanding the Blueprint: Human Embryogenesis and the Rise of Stem Cell-Based Models

The earliest stages of human development represent a period of remarkable transformation, beginning with a single fertilized egg and progressing to a structured, multi-layered embryo. Understanding these precise developmental milestones is not only fundamental to embryology but also critically important for evaluating the rapidly advancing field of synthetic embryo models. This guide provides a systematic comparison of key embryonic stages against emerging embryo model technologies, offering researchers in developmental biology and drug discovery a structured framework for benchmarking in vitro systems against established in vivo references. The transition from zygote to gastrula encompasses the first three weeks of human development, characterized by precisely timed events of cell division, differentiation, and morphological reorganization that can be quantitatively assessed for model validation [1] [2].

Comparative Timeline of Key Developmental Stages

Table 1: Chronological Stages of Early Human Development from Fertilization to Gastrulation

| Day Post-Fertilization | Carnegie Stage | Developmental Event | Key Morphological Features | Research Imaging Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Fertilization | Formation of diploid zygote | Not accessible for in vivo imaging |

| 2-3 | 2-3 | Cleavage | Division to 2-cell, 4-cell, morula (16+ cells) | Limited to in vitro models [3] |

| 4-5 | 4 | Blastulation | Formation of blastocyst with inner cell mass and trophoblast | Confocal microscopy possible for models [3] |

| 5-7 | 5 | Implantation | Blastocyst hatches and implants into uterine wall | Inaccessible for direct observation in humans |

| 7-12 | 5-6 | Bilaminar Disc | Formation of epiblast and hypoblast layers | Limited to histological reconstruction |

| 13-15 | 6-7 | Primitive Streak | Gastrulation begins; emergence of three germ layers | Ultrasound microscopy possible in animal models [3] |

| 16-21 | 8-9 | Gastrulation | Formation of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm | Live imaging limited to model organisms [3] |

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Developmental Staging Benchmarking

| Developmental Stage | Size Range | Cell Number Estimate | Critical Quality Indicators | Common Abnormalities in Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zygote | 100-150 µm | 1 | Two pronuclei, two polar bodies | Triploidy, fertilization failure |

| Morula | 120-150 µm | 16-32 | Compaction, loss of cell boundaries | Arrested cleavage, fragmentation |

| Blastocyst | 150-200 µm | 100-200 | Distinct inner cell mass, trophectoderm | Collapsed blastocoel, disordered cells |

| Bilaminar Disc | 0.1-0.2 mm | 1,000+ | Defined epiblast and hypoblast layers | Disorganized axial structuring |

| Gastrula | 0.5-1.5 mm | 10,000+ | Primitive streak, three germ layers | Incomplete mesoderm formation |

Experimental Protocols for Developmental Staging

Morphological Assessment of Blastoid Models

Protocol Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the morphological maturity of stem-cell-derived blastocyst models (blastoids) against in vivo benchmarks.

Methodology Details:

- Fix blastoids at day 5-6 of differentiation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes

- Stain with primary antibodies: OCT4 (inner cell mass), CDX2 (trophectoderm), and DAPI (nuclear)

- Image using confocal microscopy with z-stacking at 2µm intervals

- Analyze using image segmentation software to quantify cell numbers per lineage and spatial organization

Validation Metrics:

- Inner cell mass to trophectoderm cell ratio (target: 30:70)

- Blastocoel formation percentage (target: >80% of diameter)

- Polarization of trophectoderm cells (apical-basal orientation)

Recent advances in AI-based classification, such as the deepBlastoid system, have demonstrated the ability to automate this morphological assessment with accuracy surpassing human experts in research settings [4]. This tool uses deep learning to categorize blastoid structures into five quality tiers based on the clarity of inner cell clusters and fluid-filled cavities, enabling high-throughput screening of synthetic models.

Live Imaging of Gastrulation Events

Protocol Objective: To capture dynamic cell movements during gastrulation in experimental models.

Methodology Details:

- Mount embryos/models in fibrin gel for stabilization

- Use genetically encoded fluorescent reporters for germ layer markers: SOX17 (endoderm), BRA (mesoderm), SOX2 (ectoderm)

- Image with light-sheet or spinning disk confocal microscopy every 10-15 minutes for 24-48 hours

- Maintain temperature at 37°C and 5% CO2 throughout imaging

- Track individual cell trajectories using particle image velocimetry (PIV) techniques

Quantitative Analysis:

- Calculate cell velocity vectors and directionality

- Map primitive streak elongation rate (target: 5-10µm/hour)

- Quantify germ layer segregation timing and boundaries

As noted in studies of quantitative in vivo imaging, this approach has been successfully applied to avian and zebrafish embryos to follow extracellular matrix components and cell movements during early heart tube formation, providing reference data for benchmarking human models [3].

Visualization of Developmental Processes

Developmental Pathway from Zygote to Germ Layers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Embryo Model Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Markers | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG antibodies | Inner cell mass characterization | Co-localization verification |

| Lineage Tracing | CellTracker dyes, GFP reporters | Cell fate mapping | Specificity confirmation |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, laminin, fibronectin | Support for 3D culture | Batch-to-batch consistency |

| Metabolic Supplements | Pyruvate, glutamine, lipids | Energy substrate provision | Concentration optimization |

| Signaling Modulators | BMP4, FGF2, WNT agonists | Germ layer differentiation | Temporal precision |

| Fixation Reagents | Paraformaldehyde, methanol | Morphological preservation | Protocol standardization |

Benchmarking AI Applications in Embryo Model Research

The emergence of artificial intelligence tools has created new opportunities for quantifying and classifying embryonic structures, but recent studies highlight important considerations for their application in research settings.

Table 4: Performance Comparison of AI Applications in Embryo Analysis

| AI Application | Reported Performance | Limitations | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| deepBlastoid (blastoid classification) | Surpasses human expert accuracy in morphology assessment [4] | Training on limited dataset (~1,800 images) | High-throughput screening of synthetic models |

| SIL models (IVF embryo selection) | AUC ~60%, Critical error rate ~15% [5] | Poor consistency in ranking (Kendall's W ~0.35) | Limited reliability for precise quality assessment |

| LightGBM (blastocyst yield prediction) | R²: 0.673-0.676, MAE: 0.793-0.809 [6] | Center-specific training data | Cycle-level prediction rather than embryo quality |

Recent research evaluating AI stability in embryo assessment revealed substantial variability, with models showing poor consistency in embryo rank ordering (Kendall's W approximately 0.35) and high critical error rates (approximately 15%) where low-quality embryos were incorrectly top-ranked [5]. This instability, observed even among models with similar predictive accuracies, highlights the importance of rigorous validation when implementing AI tools for embryo model classification.

The precise staging of early human development from zygote to gastrula provides an essential reference framework for evaluating increasingly sophisticated embryo models. By combining traditional morphological assessment with emerging technologies such as AI classification and live imaging, researchers can establish quantitative benchmarks for model fidelity. Current data suggests that while AI tools show promise for high-throughput screening of embryo models, their instability in clinical embryo assessment underscores the need for rigorous validation in research applications. As the field progresses, integrating multiple assessment modalities—morphological, molecular, and functional—will be essential for establishing comprehensive quality standards that accurately reflect in vivo developmental processes.

Despite decades of advances in reproductive medicine, the process of human embryo implantation remains a major barrier to achieving pregnancy, contributing significantly to infertility and early pregnancy loss. Our understanding of this critical developmental stage, often referred to as a "black box," remains limited by both the inability to observe this process in utero and the poor translatability of animal models [7]. For decades, knowledge has relied solely on the Carnegie Collection—a limited set of histological specimens that precludes molecular or chronological analysis [7]. This fundamental knowledge gap has driven the development of alternative research models, each with distinct technical capabilities and ethical considerations that must be carefully benchmarked against in vivo development.

The emergence of extended in vitro embryo culture systems and stem cell-based embryo models offers powerful opportunities to study the dynamic molecular and cellular events of human embryogenesis in real time [7] [8]. These models present researchers with critical choices regarding their appropriate application, fidelity to natural development, and ethical acceptability. This review serves as a comparative guide to these technologies, objectively evaluating their performance against natural embryos and providing the experimental frameworks necessary for informed model selection in basic research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Human Embryo Research Models

Model Classifications and Characteristics

Human embryo research utilizes three primary model systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations for investigating early development.

Natural human embryos derived from IVF represent the gold standard for research but face significant ethical and practical constraints. Research is typically restricted to the first 14 days post-fertilization, a limit based on the emergence of the primitive streak and the completion of implantation [9]. While some ethical frameworks now advocate for extending this period to 28 days to study organ development origins, this remains controversial [9].

Stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs) reconstruct embryonic development using pluripotent stem cells and are categorized as either non-integrated or integrated models. Non-integrated models mimic specific aspects of development, such as the 2D micropatterned colony reflecting gastrulation or the 3D post-implantation amniotic sac embryoid (PASE) [8]. Integrated models contain both embryonic and extra-embryonic cell types and are designed to model the integrated development of the entire early human conceptus [8] [10].

In vitro embryo culture systems enable the extended culture of natural embryos beyond previous limitations, potentially allowing observation of implantation stages previously inaccessible to research [7].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Human Embryo Research Models

| Model Type | Key Features | Developmental Coverage | Ethical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Human Embryos | Derived from IVF; considered the "gold standard" | Pre-implantation to 14 days (legally restricted); some proposals to extend to 28 days | Highest protection level; subject to 14-day rule in most countries [9] |

| Non-integrated Embryo Models | Mimic specific developmental aspects; lack some tissue types | Post-implantation processes (gastrulation, amniotic sac formation) | Lower moral status than natural embryos; not subject to 14-day rule [8] [9] |

| Integrated Embryo Models | Contain embryonic and extra-embryonic cell types; model entire conceptus | Pre- to post-implantation stages; potential for extended development | Currently not granted same status as natural embryos; transfer to uterus prohibited [8] [9] |

| In Vitro Culture Systems | Support development of natural embryos in laboratory setting | Implantation stages and early post-implantation | Subject to same restrictions as natural embryos [7] |

Technical Performance Benchmarking

When evaluating model performance against natural embryogenesis, researchers must consider morphological fidelity, developmental trajectory, and molecular accuracy.

Table 2: Technical Performance Metrics of Embryo Research Models

| Model System | Morphological Fidelity | Developmental Timeline | Lineage Representation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Embryos | Complete anatomical structure | Physiologically accurate | All embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages | Limited availability; ethical restrictions; technical challenges in prolonged culture [7] [9] |

| Micropatterned Colonies | Radial organization of germ layers; lacks 3D architecture | Accelerated development; compressed timeline | Ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm; extra-embryonic cells of unclear origin [8] | Two-dimensionality doesn't reflect in vivo condition; lacks bilateral symmetry and central lumen [8] |

| PASE Embryoids | 3D amniotic sac-like structure; disk-like epiblast | Models post-implantation events | Amniotic ectoderm, epiblast, primitive streak-like cells [8] | Limited extra-embryonic components; incomplete lineage specification |

| Integrated Embryo Models | High structural organization; embryonic and extra-embryonic compartments | Varies by protocol; generally follows natural sequence | Epiblast, trophoblast, hypoblast derivatives [10] | Incomplete extra-embryonic support systems; limited developmental potential [10] |

Functional Application in Research and Drug Development

Different embryo models offer distinct advantages for specific research applications, from basic developmental biology to pharmaceutical testing.

Developmental Process Investigation: Non-integrated models like micropatterned colonies have proven invaluable for studying fundamental mechanisms such as basement membrane assembly and disassembly, with researchers identifying OCT4 as a major regulator of this process [8]. These simplified systems allow precise manipulation of specific developmental events without the complexity of complete embryogenesis.

Disease Modeling and Drug Screening: Integrated embryo models provide platforms for investigating congenital abnormalities, developmental disorders, and infertility-related conditions such as implantation failure [7] [10]. Their scalability enables medium-throughput drug screening that would be impossible using natural embryos.

AI-Enhanced Predictive Modeling: Machine learning approaches are increasingly applied to embryo assessment, with models like FEMI (Foundational IVF Model for Imaging) trained on approximately 18 million time-lapse embryo images to predict ploidy status, blastocyst quality, and developmental milestones [11]. These tools achieve area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) > 0.75 for ploidy prediction using only image data, significantly outpacing benchmark models [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Framework for Embryo Model Evaluation

To enable meaningful comparison across studies, researchers have proposed standardized assessment criteria based on morphological, temporal, and functional benchmarks [7]. This framework allows for consistent evaluation of model performance against natural embryogenesis.

Morphological Criteria include the formation of key embryonic structures such as the primitive streak, amniotic cavity, and bilaminar disc. For integrated models, the presence and organization of extra-embryonic tissues represents a critical benchmark.

Temporal Alignment requires that developmental milestones in model systems occur within timeframes consistent with natural embryogenesis. Significant deviations may indicate aberrant developmental pathways.

Functional Capacity assessment examines whether models recapitulate fundamental developmental processes such as cell differentiation, tissue morphogenesis, and lineage specification observed in natural embryos.

Machine Learning Implementation for Embryo Assessment

Recent advances incorporate artificial intelligence for quantitative embryo evaluation. The development of machine learning models like LightGBM for predicting blastocyst yield demonstrates how AI can enhance predictive accuracy in embryo assessment [6].

Data Preparation: Models are typically trained on thousands of IVF cycles, with datasets randomly split into training and test sets. For example, one study utilized 9,649 cycles with 3,927 (40.7%) producing no usable blastocysts, 3,633 (37.7%) yielding one or two usable blastocysts, and 2,089 cycles (21.6%) resulting in three or more usable blastocysts [6].

Feature Selection: Recursive feature elimination (RFE) identifies optimal predictive features. The LightGBM model identified eight key predictors, with the number of extended culture embryos emerging as the most critical (61.5%), followed by Day 3 embryo metrics including mean cell number (10.1%) and proportion of 8-cell embryos (10.0%) [6].

Model Validation: Performance metrics include R² values (0.67-0.68 for top models vs. 0.59 for linear regression) and mean absolute error (0.79-0.81 vs. 0.94 for linear regression) [6]. The FORTUNE classification system demonstrates how such models can stratify patients into distinct prognostic groups, with chances of obtaining ≥3 euploid blastocysts ranging from 79.8% in very good prognosis groups to 0% in very poor prognosis groups [12].

Protocol for Integrated Embryo Model Generation

The generation of integrated embryo models requires precise coordination of multiple cell types and signaling environments.

Cell Line Preparation: Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), are maintained in defined conditions. Extra-embryonic-like cells may be modified to overexpress specific transcription factors [10].

Self-Organization Induction: Through cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and cortical tension regulation, stem cells self-assemble into structures mimicking post-implantation embryos. XEN cells orient themselves under ES cells, while TS cells position above ES cells, recapitulating natural embryonic architecture [10].

Culture Conditions: Models are typically embedded in ECM-containing media and cultured under precisely controlled physicochemical conditions to support multi-lineage development and morphogenesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Embryo Model Research

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVF Blastocyst Medium | Supports embryo development from blastocyst stage to transfer | Extended embryo culture; implantation studies | Defined formulations with precise amino acids, vitamins, growth factors; controlled pH and osmolality [13] |

| Extracellular Matrix Components | Provide structural support and biochemical cues | 3D model formation; microenvironment studies | Matrigel, collagen, laminin; concentration affects differentiation outcomes [8] |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | Direct lineage specification and morphogenesis | Germ layer patterning; embryonic-extraembryonic interactions | BMP4, WNT, NODAL inhibitors/activators; concentration and timing critical [8] |

| Cell Lineage Markers | Identify and validate cell types | Quality assessment; protocol validation | Immunofluorescence markers for epiblast (OCT4), trophectoderm (CDX2), hypoblast (SOX17) [10] |

| Time-Lapse Imaging Systems | Non-invasive monitoring of development | Morphokinetic analysis; AI model training | EmbryoScope systems; image capture frequency affects data resolution [11] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | Molecular characterization at cellular resolution | Transcriptomic profiling; lineage tracing | scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics; requires cell dissociation or sectioning [10] |

Ethical Frameworks and Regulatory Considerations

The ethical landscape surrounding human embryo research continues to evolve alongside technical capabilities. The foundational "14-day rule" – restricting embryo culture to approximately 14 days post-fertilization – represents a carefully considered but debatable demarcation rather than a rigid moral boundary [9]. Recent proposals advocate extending this limit to 28 days to study critical developmental events including the origins of organ development and congenital abnormalities, while noting that beyond 28 days, research on aborted tissues becomes a viable alternative [9].

Stem cell-based embryo models present distinct ethical considerations. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has established clear guidelines prohibiting the use of any stem cell-based embryo models to attempt pregnancy in humans or animals, or growing them in artificial wombs to viability points [14]. A consensus is emerging that integrated embryo-like structures should not currently be granted the same moral status as natural embryos, though if they pass certain developmental competence tests, they should be subject to similar regulations [9].

For drug development applications, embryo models offer significant advantages in reduced ethical concerns compared to natural embryo research. However, researchers must navigate varying international regulations regarding embryo model research and its applications in pharmaceutical testing [10]. The ethical framework for these technologies continues to develop through multidisciplinary collaboration between scientists, ethicists, and policymakers.

The rapidly advancing field of human embryo modeling presents researchers with an expanding toolkit for investigating early development. Natural embryos remain the gold standard but face significant ethical and practical constraints. Stem cell-based models offer complementary approaches with varying degrees of biological fidelity and ethical complexity. As these technologies continue to evolve, standardized benchmarking against natural embryogenesis will be essential for validating their utility in basic research and drug development.

Future advances will likely focus on enhancing model fidelity through improved recapitulation of embryonic-extraembryonic interactions, spatial organization, and developmental timing. The integration of artificial intelligence with multi-omics technologies promises to unlock deeper insights into developmental mechanisms while improving predictive accuracy for clinical applications. Throughout these technical advances, maintaining thoughtful ethical oversight and public engagement will be essential for responsible progress in this transformative field.

For researchers selecting embryo models, the optimal choice depends fundamentally on the specific scientific question, with each model system offering distinct advantages for particular applications. As these technologies mature, they hold immense promise for illuminating the mysteries of early human development, unraveling the causes of developmental disorders, and creating novel platforms for drug discovery and safety testing.

Stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs) are three-dimensional structures derived from pluripotent stem cells that self-organize to mimic specific aspects of early human embryonic development [15]. These innovative models provide unprecedented opportunities to study developmental processes that are otherwise inaccessible in utero, addressing fundamental questions about human embryogenesis, infertility, early pregnancy loss, and developmental disorders [8] [15]. The field has rapidly evolved to generate models that recapitulate various developmental stages, leading to the emergence of two primary classifications: integrated and non-integrated systems.

Integrated embryo models are designed to contain both embryonic (epiblast-derived) and extra-embryonic (hypoblast and trophoblast-derived) cell lineages, aiming to recapitulate the integrated development of the entire early human conceptus [16] [8]. In contrast, non-integrated models typically consist of epiblast derivatives alone and mimic only specific aspects of embryo development, often lacking complete extra-embryonic lineages [16] [8]. Both systems serve as vital tools for overcoming the ethical and technical limitations associated with human embryo research, while providing scalable platforms for investigating developmental principles and disease mechanisms [17] [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Embryo Model Classifications

| Feature | Integrated Models | Non-Integrated Models |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Contain embryonic and multiple extra-embryonic lineages | Model specific aspects of development without complete extra-embryonic compartments |

| Lineage Composition | Epiblast, trophoblast, and hypoblast derivatives | Primarily epiblast-derived tissues; may include some extra-embryonic cell types |

| Developmental Potential | Model integrated development of entire conceptus | Limited to specific processes or windows of development |

| Regulatory Oversight | Subject to more extensive scientific and ethical review [16] | Generally subject to less stringent oversight [16] |

| Representative Examples | Blastoids, E-assembloids, SEMs, Bilaminoids [16] | Gastruloids, MP colonies, PASE, PTED embryoids [16] [8] |

Quantitative Benchmarking of Model Systems

Lineage Composition and Molecular Fidelity

The utility of embryo models hinges on their molecular, cellular, and structural fidelity to natural human embryos [17]. Recent advances in single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) have enabled rigorous transcriptional benchmarking against integrated reference datasets from human embryos spanning zygote to gastrula stages [17]. These references capture key developmental transitions, including the first lineage branch point where inner cell mass and trophectoderm cells diverge around embryonic day 5 (E5), followed by the bifurcation of ICM cells into epiblast and hypoblast lineages [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Embryo Models Against In Vivo References

| Model Type | Key Marker Expression | Developmental Stage Modeled | Transcriptional Similarity to In Vivo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blastoids | CDX2 (TE), NR2F2 (TE), NANOG (epiblast), GATA4 (hypoblast) [17] | Pre-implantation blastocyst (E5-E7) | High similarity to blastocyst lineages; shows limited developmental potential post-implantation [16] |

| Gastruloids | TBXT (primitive streak), POU5F1 (epiblast), MESP2 (mesoderm) [17] | Post-implantation gastrulation (E14+) | Recapitulates germ layer specification; lacks extra-embryonic support tissues [8] |

| MP Colonies | BMP4-responsive genes, ectoderm/mesoderm/endoderm markers [8] | Early gastrulation (E14) | Represents radial patterning of germ layers; lacks 3D architecture and bilateral symmetry [8] |

| PASE | ISL1 (amnion), GABRP (amnion), epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers [17] [8] | Peri-implantation to early post-implantation (E8-E10) | Forms amniotic sac-like structures; shows lumenogenesis and PS-like structure development [8] |

Functional and Morphological Benchmarking

Beyond transcriptional profiling, functional assessments evaluate the morphological and developmental capabilities of embryo models. Quantitative experimental embryology approaches—including cell addition, removal, and confinement experiments—provide essential metrics for evaluating model performance [18]. For instance, the ability of blastoids to mimic the mechanical properties of natural blastocysts, such as surface tensions governing cell sorting and lineage segregation, represents a critical benchmark [19]. Computational modeling of these physical interactions has revealed how asymmetric segregation of apical domains generates blastomeres with different contractility, ultimately triggering cell sorting into inner and outer positions [19].

Cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and cortical tension have been identified as crucial mechanical determinants in synthetic embryo formation, with differential cadherin expression driving precise cell sorting that defines the basic architecture of developing embryo models [10]. Experimental manipulation of these mechanical properties can enhance the formation efficiency of well-organized synthetic embryos, providing quantitative parameters for optimizing model systems [10].

Experimental Protocols for Model Generation

Generation of Non-Integrated Embryo Models

Micropatterned Colonies (MP Colonies):

- Protocol: Seed human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) on circular micropatterns fabricated on slides with arrays of extracellular matrix (ECM)-coated disks [8]. The ECM drives cell adhesion and defines colony boundaries.

- Induction: Treat with BMP4 to induce self-organization into radial patterns over 3-5 days [8].

- Outcome: Generation of 2D structures with an ectodermal center encircled by mesodermal and endodermal rings, with an outermost ring of extra-embryonic cells of unclear origin [8].

- Validation: Immunostaining for germ layer markers (SOX2 for ectoderm, BRA for mesoderm, SOX17 for endoderm) and analysis of BMP4 response pathways [8].

Gastruloids:

- Protocol: Aggregate hESCs in low-adhesion U-bottom plates to form 3D aggregates [8].

- Induction: Activate Wnt, BMP, and Nodal signaling pathways using CHIR99021, BMP4, and other small molecules to mimic primitive streak patterning [8].

- Outcome: Formation of elongated structures displaying axial organization and representing the three germ layers without extra-embryonic support [8].

- Validation: Single-cell RNA-sequencing to confirm presence of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm populations; trajectory analysis to verify proper lineage relationships [17].

Generation of Integrated Embryo Models

Blastoids:

- Protocol: Aggregate extended pluripotent stem cells (EPS cells) or reprogrammed cells in specialized 3D culture systems [16] [10].

- Lineage Specification: Employ sequential modulation of Hippo, TGF-β, and Wnt signaling pathways to specify trophectoderm, epiblast, and primitive endoderm lineages [16].

- Outcome: Formation of blastocyst-like structures with three founding lineages: epiblast, hypoblast, and trophoblast [16].

- Validation: Immunofluorescence for lineage-specific markers (NANOG for epiblast, GATA6 for hypoblast, CDX2 for trophoblast); transcriptomic comparison to human blastocysts; demonstration of in vitro attachment and outgrowth potential [16] [17].

E-assembloids/SEMs (Structured Embryo Models):

- Protocol: Co-culture hESCs with genetically modified extraembryonic-like cells overexpressing specific transcription factors in a 3D ECM scaffold [10].

- Induction: Utilize tissue-tissue interactions and self-organization principles driven by cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and cortical tension [10].

- Outcome: Formation of post-implantation embryo-like structures with embryonic and extra-embryonic compartments [16] [10].

- Validation: Detailed morphological analysis; scRNA-seq benchmarking against integrated human embryo references; functional tests for developmental potential [17] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Embryo Model Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Embryo Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Sources | Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), extended pluripotent stem cells (EPS cells) [8] [10] | Starting material for generating embryo models; different types offer varying differentiation potentials and applications |

| Signaling Modulators | BMP4, CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), FGF2, TGF-β inhibitors, Nodal/Activin A [8] | Direct lineage specification and patterning by activating or inhibiting key developmental pathways |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, laminin, collagen, synthetic hydrogels [8] [19] | Provide structural support and biochemical cues for 3D organization; influence cell polarity and morphogenesis |

| Culture Systems | Low-adhesion plates, micropatterned surfaces, air-liquid interface cultures, microfluidic devices [8] | Control the physical environment for aggregate formation and self-organization; enable high-throughput production |

| Analytical Tools | Single-cell RNA-sequencing, live-imaging systems, immunofluorescence markers, computational modeling tools [17] [18] [19] | Enable validation and characterization of models at molecular, cellular, and structural levels |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

Embryo model development is governed by conserved signaling pathways that direct lineage specification and morphogenetic events. In integrated models, the interplay between embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues is mediated by BMP, Wnt, Nodal, and FGF signaling pathways, which establish feedback loops necessary for coordinated development [8] [10]. In non-integrated models such as gastruloids, controlled activation of Wnt signaling initiates primitive streak-like patterning, while BMP and Nodal signaling guide germ layer segregation [8].

At the molecular level, transcription factor networks drive lineage commitment: OVOL2 and CDX2 regulate trophectoderm specification; NANOG and POU5F1 maintain pluripotency in epiblast compartments; GATA4 and SOX17 direct hypoblast formation; and TBXT marks primitive streak initiation during gastrulation [17]. Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses have identified additional regulators, including HMGN3 which shows upregulated expression across multiple lineages during post-implantation stages [17].

Stem cell-based embryo models, whether integrated or non-integrated, provide complementary platforms for investigating distinct aspects of human development. Integrated models offer more comprehensive systems for studying the crosstalk between embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues during critical developmental transitions, while non-integrated models allow focused investigation of specific processes such as germ layer patterning and axial organization [16] [8]. Both approaches continue to be refined through rigorous benchmarking against in vivo references, particularly using single-cell transcriptomic atlases that provide high-resolution maps of human embryogenesis [17].

The future of embryo modeling will likely see increased sophistication in model fidelity, integration with microphysiological systems, and application to disease modeling and drug screening [10]. However, these advances must be accompanied by ongoing ethical oversight, as emphasized in recent ISSCR guideline updates that propose all organized 3D human SCBEMs should be subject to appropriate review, have clear scientific rationale, and adhere to defined culture timelines [16] [20] [21]. As the field progresses, quantitative benchmarking against gold-standard references will remain essential for validating new models and ensuring their physiological relevance to human development.

The use of model organisms, particularly the mouse (Mus musculus), is fundamental to biomedical research, providing critical insights into the molecular and cellular mechanisms of human development. Despite significant genetic homology, substantial differences in developmental timing, physiology, and gene regulation exist between these species, creating a "cross-species gap" that can hinder translational research success. In the context of benchmarking embryo models—a rapidly advancing field—understanding these differences becomes paramount for accurate validation and interpretation. This guide objectively compares mouse and human developmental processes, synthesizing current experimental data to highlight critical species-specific differences. By framing these comparisons within a rigorous benchmarking framework, we provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the evidence necessary to critically evaluate model systems and improve the predictive power of preclinical studies.

Fundamental Biological Differences in Development

Developmental Timing and Staging

Mouse and human embryos follow distinct developmental timelines, particularly during key events such as implantation and gastrulation. These temporal differences are crucial for interpreting experimental results from stem cell-derived embryo models.

Table 1: Comparative Developmental Timelines of Key Early Events

| Developmental Event | Mouse Timeline | Human Timeline | Significance for Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implantation | ~E4.5 | ~Day 7-12 | Human models require extended culture to post-implantation stages [17] |

| Gastrulation | ~E6.5-7.5 | ~Day 14-16 | Human gastrulation occurs after embryo culture "14-day rule" limit [17] |

| Blastocyst Formation | ~E3.5 | ~Day 5-6 | Timing is relatively conserved, making blastocyst models more comparable [17] |

| Early Organogenesis | ~E8.5 and beyond | ~Week 3-8 and beyond | Mouse models enable full in vivo study of organogenesis [22] |

Transcriptomic and Regulatory Divergence

Systematic comparisons of gene expression profiles reveal that transcriptional programs, even when producing similar morphological stages, can differ significantly between species.

- Divergent Transcriptional Programs: A comparative analysis of embryonic gene expression found that when directly translating mouse results to human, only one out of three significantly altered genes was shared, with a mean overlap of just 5% (1 in 20 genes) across studies. This indicates that identification of human disease-associated genes by direct inference from mouse gene expression fails to capture the majority of the human signal [23].

- Conservation of Developmental Genes, Divergence of Expression: While the core set of developmental genes is often conserved, their expression patterns can be species-specific. Research in nematodes revealed that over a third of orthologous genes exhibited divergent temporal expression patterns between two morphologically similar species, suggesting that similar developmental outcomes can be achieved through different transcriptional routes [24].

- Epigenetic and Regulatory Landscapes: Studies of the developing mouse visual cortex have reconstructed detailed gene regulatory networks that link transcription factors to downstream targets through accessible chromatin motifs [25]. The degree to which these specific regulatory connections are conserved in human development remains an active area of investigation, with differences likely contributing to species-specific traits.

Experimental Data and Quantitative Comparisons

Direct Functional Assessment of Enhancer Activity

Non-coding regulatory elements, such as enhancers, often exhibit significant species-specificity in their activity. The dual-enSERT (dual-fluorescent enhancer inSERTion) system enables quantitative comparison of human enhancer variants in live mouse embryos [26].

Table 2: In Vivo Analysis of Human Enhancer Variants Using Dual-enSERT

| Enhancer (Gene) | Variant | Associated Condition | Observed Effect in Mouse Model | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZRS (Shh) | 404G>A | Preaxial Polydactyly | Ectopic reporter expression in anterior limb bud | 31-fold stronger expression in anterior hindlimb; Gain-of-function [26] |

| hs737 (EBF3) | 830G>A | Autism Spectrum Disorder | Altered reporter expression in the brain | Reproducible alteration of in vivo enhancer activity [26] |

| OTX2 Enhancer | Rare variants | Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Altered reporter activity in brain | Identified specific variants that disrupt normal activity [26] |

Methodologies for Cross-Species Translation

To systematically address transcriptomic differences, computational tools like the Found In Translation (FIT) model have been developed. FIT leverages public gene expression data to predict human disease-associated genes from mouse experiments [23].

- Experimental Protocol for FIT Model Application:

- Input Data Collection: A new mouse gene expression dataset (disease vs. control) is generated or obtained.

- Compendium Reference: The FIT model draws upon a manually curated compendium of 170 paired human and mouse gene expression datasets across 28 diseases [23].

- Model Prediction: Using a regularized linear model (LASSO), FIT predicts the expected human effect-size per gene by combining the new mouse data with prior knowledge on mouse-human similarities and differences from the training compendium.

- Output and Validation: The model outputs a prioritized list of genes with high predicted relevance to the human condition. In validation studies, FIT increased the overlap of differentially expressed genes with human data by 20-50% compared to direct extrapolation from mouse results [23].

Figure 1: Workflow of the FIT Model for Cross-Species Prediction. The FIT model uses a new mouse experiment and a large compendium of existing paired data to predict genes relevant to the human condition, improving upon direct cross-species extrapolation [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Cross-Species Developmental Studies

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-enSERT System | Cas9-based site-specific dual-fluorescent reporter for quantitative comparison of enhancer variants in live mice [26]. | Testing human enhancer variants linked to polydactyly and autism in mouse embryos. |

| FIT (Found In Translation) Model | Data-driven statistical model predicting human disease genes from mouse gene expression data [23]. | Increasing translational overlap for diseases like sepsis; available at www.mouse2man.org. |

| scRNA-seq / snMultiome | Single-cell transcriptomics and epigenomics for cell-type atlas construction and regulatory network inference [25]. | Mapping developmental trajectories of all major cell types in the mouse visual cortex. |

| StembryoNet (AI Model) | Deep learning model (ResNet18-based) for classifying and predicting outcomes of stem cell-derived embryo models [27]. | Improving selection accuracy of normal vs. abnormal ETiX-embryos based on live imaging. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Non-invasive metabolic profiling of embryo culture medium and intracellular components [28]. | Characterizing dynamic glucose and lipid metabolic profiles during murine preimplantation development. |

The empirical data clearly demonstrate that while mouse models are indispensable for developmental biology, direct extrapolation to human development is fraught with challenges. Significant differences in transcriptional regulation, enhancer function, and developmental timing necessitate a cautious and informed approach. For researchers benchmarking embryo models or investigating developmental mechanisms, a multi-faceted strategy is recommended: First, leverage computational tools like the FIT model to prioritize candidate genes and pathways with higher potential for human relevance. Second, employ advanced functional assays like dual-enSERT to directly test human regulatory elements in a live, whole-animal context when possible. Finally, validate key findings across multiple systems, including human cell-based models and where available, non-human primate data, to build a convincing case for translational relevance. By systematically acknowledging and investigating species-specific differences, the scientific community can more effectively bridge the cross-species gap and accelerate the discovery of mechanisms underlying human development and disease.

Building and Applying Embryo Models: From Protocols to Biomedical Insights

The study of early human development has long been constrained by ethical considerations and the limited availability of human embryos. In response, scientists have developed sophisticated stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs) that replicate specific aspects of embryogenesis. These models serve as powerful tools for investigating infertility, early pregnancy loss, and congenital diseases, while also providing platforms for drug testing and toxicology screening [8] [29]. The usefulness of these models hinges entirely on their fidelity to in vivo development, making rigorous benchmarking against reference human embryo datasets a critical step in their validation [17].

This guide provides an objective comparison of three primary tools in the scientist's toolkit: blastoids, gastruloids, and micropatterned colonies. We compare their performance, applications, and limitations, with a particular focus on their validation against in vivo references, to help researchers select the most appropriate model for their investigative needs.

Blastoids: Modeling the Pre-Implantation Embryo

Blastoids are three-dimensional cellular models that mimic the pre-implantation human blastocyst approximately 5-7 days post-fertilization [29]. They are integrated models, meaning they contain representative cells from both the embryonic epiblast (which forms the embryo proper) and extra-embryonic lineages, specifically the trophectoderm (precursor to the placenta) and hypoblast (primitive endoderm, which forms the yolk sac) [30] [29]. Their primary application lies in studying early lineage specification, blastocyst formation, and the critical process of implantation [30] [29].

Protocols for generating blastoids have evolved rapidly. Early methods used naive human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) forced to aggregate in specialized microwells, with more recent approaches achieving efficiencies greater than 70% [29]. These models have been co-cultured with endometrial cells to create "feto-maternal assembloids," successfully mimicking ICM polarization and implantation events, including endometrial stromal cell fusion [30].

Gastruloids: Modeling Post-Implantation Development and Gastrulation

Gastruloids are three-dimensional models that primarily mimic the post-implantation period, specifically the process of gastrulation—a key developmental stage around day 14-16 in human embryos when the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) are established [8] [31]. Traditionally considered non-integrated models, they typically lack structured extra-embryonic tissues and are instead generated by prompting a single stem cell entity to self-organize and differentiate using chemical and physical triggers [8].

These models are particularly valuable for studying germ layer specification, axial organization, and the emergence of the body plan. A significant advance in this field is the development of microraft array-based technology, which allows for the automated screening and sorting of hundreds to thousands of individual gastruloids, enabling large-scale assays and the dissection of heterogeneity within these complex structures [31].

Micropatterned Colonies: A 2D Platform for Studying Gastrulation

Micropatterned (MP) Colonies are a two-dimensional model system designed to study the spatial patterning events of gastrulation [8]. They are created by confining human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) to circular micropatterns on slides coated with extracellular matrix (ECM). Treatment with Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 (BMP4) induces the cells to self-organize into radial patterns consisting of an ectodermal center, a mesodermal ring, and an endodermal outer layer [8]. A key feature is the formation of a primitive streak (PS)-like structure where cells undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and migrate inwards, mimicking gastrulation [8].

The major strengths of this system are its simplicity, high reproducibility, and ease of imaging. However, its two-dimensionality does not fully reflect the in vivo condition, and it lacks key features like bilateral symmetry and a central lumen that could develop into an amniotic cavity [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Stem Cell-Based Embryo Models

| Feature | Blastoids | Gastruloids | Micropatterned Colonies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Stage Modeled | Pre-implantation blastocyst (∼5-7 days post-fertilization) [29] | Post-implantation gastrulation (∼14+ days) [8] [31] | Post-implantation gastrulation (∼14-16 days) [8] |

| Key Lineages Present | Epiblast, Trophectoderm, Hypoblast [30] [29] | Ectoderm, Mesoderm, Endoderm (three germ layers) [8] | Ectoderm, Mesoderm, Endoderm (three germ layers) [8] |

| Extra-Embryonic Tissues | Integrated (contains both embryonic & extra-embryonic) [29] | Generally non-integrated (may contain trophectoderm-like cells) [8] [31] | Non-integrated (may contain cells of unclear extra-embryonic origin) [8] |

| Morphology | 3D spherical, cavitated structure [30] | 3D aggregates [8] | 2D patterned colonies [8] |

| Primary Applications | Implantation studies, early lineage specification [30] [29] | Germ layer formation, axial patterning, disease modeling [8] [31] | Signaling pathway analysis, spatial patterning, high-content screening [8] |

Benchmarking and Validation Against In Vivo Reference Data

A critical challenge in the field is the accurate authentication of embryo models. Global gene expression profiling via single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has become the gold standard for unbiased validation [17]. A significant recent advancement is the creation of a comprehensive human embryo reference tool that integrates scRNA-seq data from six published human datasets, covering development from the zygote to the gastrula stage [17]. This tool allows researchers to project their SCBEM data onto the in vivo reference to annotate cell identities and assess transcriptional fidelity.

Using such a reference for benchmarking is crucial, as studies have revealed a risk of misannotation of cell lineages in embryo models when relevant human embryo references are not utilized [17]. For instance, when used to analyze published models, this integrated reference has highlighted both significant overlaps with human pre-implantation stage cells and the presence of post-implantation cell clusters not typically seen in native pre-implantation samples, underscoring the models' complexity and the need for careful validation [30] [17].

Table 2: Benchmarking Data and Validation Methods

| Model | Key Benchmarking Metrics | Transcriptomic Fidelity (vs. In Vivo Reference) | Common Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blastoids | Presence of OCT4+ (epiblast), GATA3+ (trophectoderm), SOX17+ (hypoblast) cells; blastocoel cavity formation [30] | Overlap with pre-implantation cell clusters, but with notable variation and differences in composition [30] [17] | Immunofluorescence for lineage markers, scRNA-seq, implantation potential in co-culture [30] [29] |

| Gastruloids | Formation of three germ layers; spatial organization; expression of NOG, KRT7; response to BMP4 signaling [31] | Used to identify model-specific transcriptomes and potential misannotations; requires projection on post-implantation reference [17] | Immunofluorescence, scRNA-seq, automated image analysis of patterning [31] |

| Micropatterned Colonies | Radial organization of germ layers; formation of PS-like structure; EMT and cell migration [8] | Can be projected onto gastrulation-stage reference to validate primitive streak-like and germ layer identities [17] | Immunofluorescence (e.g., Collagen IV for basement membrane), analysis of signaling pathways (BMP, WNT, Nodal) [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Generating Gastruloids and Micropatterned Colonies

The formation of 2D gastruloids or micropatterned colonies begins with the precise patterning of an extracellular matrix (ECM) onto a culture surface. The process involves confining human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) to these defined circular islands, which self-organize and differentiate in response to a key signaling molecule, BMP4 [8] [31].

Protocol for Generating Blastoids

Blastoid generation leverages the self-organization capabilities of naive-state pluripotent stem cells. The process relies on forced aggregation to initiate the formation of a structure that mimics the natural blastocyst [30] [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation with embryo models requires a suite of reliable reagents and platforms. The table below details key materials and their functions as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Naive State hPSCs | Starting cell population with pre-implantation-like pluripotency, crucial for forming integrated models. | Generation of blastoids [30] [29]. |

| Primed/Conventional hPSCs | Starting cell population with post-implantation-like pluripotency. | Formation of gastruloids and micropatterned colonies [8] [31]. |

| AggreWell/U-Bottom Plates | Microwell plates that force cell aggregation, standardizing the size and shape of 3D aggregates. | Generating uniform blastoid and gastruloid precursors [30]. |

| Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 (BMP4) | A key morphogen that triggers signaling cascades for germ layer patterning and trophectoderm-like differentiation. | Inducing spatial patterning in micropatterned colonies and gastruloids [8] [31]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Coating substrate that provides adhesive signals and defines the geometry for 2D model culture. | Creating circular micropatterns for colony formation [8] [31]. |

| GATA3, TFAP2C, GATA6, SOX17 Inducible Systems | Transcription factor overexpression to drive differentiation toward extra-embryonic lineages. | Generating trophoblast-like and hypoblast-like cells for integrated embryoids [32]. |

| Microraft Arrays | Platforms with indexed, releasable microrafts for high-throughput imaging and sorting of individual microtissues. | Automated screening and sorting of gastruloids based on phenotypic features [31]. |

The choice between blastoids, gastruloids, and micropatterned colonies is dictated by the specific research question. Blastoids are unparalleled for studying implantation and early lineage segregation, gastruloids excel at modeling gastrulation and germ layer specification, and micropatterned colonies offer a highly reproducible system for dissecting signaling pathways during patterning events [8] [30] [29].

A paramount consideration in this rapidly advancing field is the ethical framework governing this research. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has established clear guidelines, including the prohibition of transferring any SCBEM to a human or animal uterus or culturing them to the point of potential viability [14] [33]. Adherence to these guidelines is essential for maintaining public trust and ensuring the responsible progression of this transformative science.

As benchmarked model fidelity continues to improve, this toolkit of SCBEMs will profoundly deepen our understanding of human development and disease, paving the way for novel therapeutic interventions in reproductive medicine and beyond.

The emergence of stem cell-based human embryo models represents a transformative development in the study of early human development, offering unprecedented tools for investigating fundamental biological processes, infertility, congenital diseases, and drug testing [8]. These in vitro models are designed to recapitulate specific aspects or entire stages of early human embryogenesis, from the pre-implantation blastocyst to the post-implantation gastrula stage [17] [8]. However, the scientific validity and utility of these models hinge entirely on their fidelity to the in vivo counterparts they aim to emulate [17]. Without rigorous benchmarking against genuine human embryonic reference data, researchers cannot determine whether the cell types, structures, and molecular patterns observed in models accurately reflect natural development or represent artifacts of in vitro culture conditions.

This guide establishes a comprehensive framework for evaluating stem cell-based embryo models against three fundamental criteria: cell-type composition, spatial organization, and functional capacity. The development of integrated analysis tools and reference datasets now enables researchers to move beyond qualitative assessments based on a handful of marker genes to quantitative, unbiased comparisons of entire transcriptional programs and tissue architectures [17] [34]. By implementing the standardized benchmarking approaches detailed in this guide, researchers can authenticate their models with greater confidence, ensure reproducibility across laboratories, and generate biologically meaningful data that advances our understanding of human development.

Benchmarking Criterion 1: Cell-Type Composition

Experimental Protocol: scRNA-Seq and Reference Atlas Integration

The most robust method for authenticating cell-type composition in embryo models involves single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) followed by computational projection onto a comprehensive reference atlas. The protocol below outlines the key steps for this authentication process, adapted from established methodologies [17].

- Step 1: Reference Atlas Construction: Integrate multiple published human scRNA-seq datasets covering developmental stages from zygote to gastrula using a standardized processing pipeline. This includes read mapping and feature counting with the same genome reference (e.g., GRCh38) to minimize batch effects. Employ data integration methods such as fast Mutual Nearest Neighbors (fastMNN) to correct for technical variations between datasets and create a unified transcriptional landscape [17].

- Step 2: Cell Type Annotation: Annotate cell identities in the integrated reference using known lineage-specific markers. For early human development, key lineages include trophectoderm (TE), inner cell mass (ICM), epiblast (EPI), hypoblast, and their derivatives (e.g., cytotrophoblast, syncytiotrophoblast, extravillous trophoblast, amnion, primitive streak, mesoderm, definitive endoderm) [17]. Validate these annotations against available human and non-human primate datasets.

- Step 3: Query Data Processing: Process scRNA-seq data from the embryo model using the same bioinformatic pipeline and reference genome as the reference atlas to ensure technical compatibility.

- Step 4: Projection and Prediction: Project the query data onto the pre-established reference using a stabilized Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Utilize a prediction tool to assign cell identities from the reference to cells in the embryo model based on transcriptional similarity [17].

- Step 5: Quantitative Assessment: Calculate the proportion of cells in the model that confidently map to expected cell types from the reference at the corresponding developmental stage. Identify and investigate any cell populations that project poorly or map to unexpected identities, as these may represent mis-specifications [17].

Key Analytical Tool: The Integrated Human Embryo Transcriptome Reference

The creation of a comprehensive, integrated reference is fundamental to cell-type composition benchmarking. One such resource integrates six publicly available human datasets, encompassing development from zygote to gastrula stages (Carnegie Stage 7) [17]. This unified atlas includes 3,304 early human embryonic cells and provides a continuous transcriptional roadmap of early human development [17].

Table 1: Key Lineage Markers in the Human Embryo Reference Atlas [17]

| Cell Lineage/Type | Key Marker Genes | Developmental Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Morula | DUXA |

Pre-implantation |

| Inner Cell Mass (ICM) | PRSS3 |

Pre-implantation (E5) |

| Epiblast (early) | POU5F1, NANOG, TDGF1 |

Pre- to Post-implantation |

| Epiblast (late) | HMGN3 |

Post-implantation (E9-CS7) |

| Hypoblast (early) | GATA4, SOX17 |

Post-implantation (E5-E10) |

| Hypoblast (late) | FOXA2, HMGN3 |

Post-implantation (E10+) |

| Trophectoderm (TE) | CDX2, NR2F2 |

Pre-implantation (E5) |

| Cytotrophoblast (CTB) | GATA2, GATA3, PPARG |

Post-implantation |

| Primitive Streak | TBXT |

Gastrulation (CS7) |

| Amnion | ISL1, GABRP |

Gastrulation (CS7) |

| Extra-Embryonic Mesoderm | LUM, POSTN |

Gastrulation (CS7) |

This reference tool has demonstrated practical utility by revealing the risk of misannotation in published human embryo models when relevant human references were not used for benchmarking [17]. For instance, models might lack specific late epiblast markers or express unexpected combinations of transcription factors, highlighting deviations from in vivo developmental trajectories.

Benchmarking Criterion 2: Spatial Organization

Experimental Protocol: Spatially Resolved Omics and Multi-Scale Analysis

While transcriptome analysis identifies cell types, assessing their physical arrangement is crucial for evaluating morphological fidelity. Spatially Resolved Omics (SRO) technologies enable molecular profiling while preserving spatial context, allowing for direct comparison of tissue organization between embryo models and natural embryos [34].

- Step 1: Data Acquisition: Generate SRO data from embryo model sections using technologies such as Xenium, MERFISH, or seqFISH. These methods provide transcriptome-wide or targeted gene expression data along with the precise centroid coordinates of each cell [34].

- Step 2: Cell-Type Annotation and Segmentation: Annotate cell types based on the SRO gene expression data, either de novo or by leveraging cell-type signatures from the scRNA-seq reference. Perform cell segmentation to define the boundaries and spatial positions of all cells within the tissue section.

- Step 3: Multi-Scale Spatial Relationship Analysis: Quantify spatial relationships using an analytical framework like CRAWDAD (Cell-type Relationship Analysis Workflow Done Across Distances) [34]. This workflow assesses whether cell types are statistically enriched (colocalized) or depleted (separated) within each other's neighborhoods at various length scales.

- Step 4: Null Model Generation: Create an empirical null background by shuffling cell-type labels within tiles of a grid overlaid on the tissue. The tile size corresponds to the spatial length scale being tested, preserving local spatial structure while randomizing global cell-type relationships [34].

- Step 5: Statistical Testing and Trend Analysis: For a given reference cell type, calculate the observed proportion of neighbor cell types within a defined neighborhood distance (e.g., 50µm). Compare this to the distribution of proportions from the shuffled data using a binomial proportion test, generating a Z-score for each cell-type pair. Repeat this analysis across a series of length scales (e.g., from 100µm to 1000µm) to create a multi-scale spatial relationship profile [34].

Key Analytical Tool: The CRAWDAD Workflow

The CRAWDAD R package provides a standardized method for quantifying cell-type spatial relationships, moving beyond qualitative descriptions [34]. Its utility lies in characterizing relationships at multiple spatial extents, which is critical because some cell types interact at fine, micrometer scales (e.g., for paracrine signaling), while others organize into larger functional tissue units or anatomical structures [34].

Table 2: Interpretation of Multi-Scale Spatial Relationship Trends [34]

| Spatial Trend Pattern | Biological Interpretation | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Monotonic Enrichment | Two cell types are consistently colocalized across all analyzed scales. | Intermixed cell populations, such as supportive stromal and parenchymal cells. |

| Oscillatory Trend | Cell types show separation at fine scales but colocalization at broader scales. | Cell types residing in adjacent but distinct tissue layers or compartments within the same organ. |

| Monotonic Depletion | Two cell types are consistently separated across all analyzed scales. | Mutually exclusive cell populations occupying distinct anatomical regions. |

| Scale-Dependent Relationship | A colocalization or separation relationship is only evident at a specific spatial threshold. | A structured niche environment where interactions are confined to a specific physical range. |

This multi-scale approach is more informative than whole-tissue analysis, as it can reveal, for example, that two cell types form distinct compartments at a fine scale but are part of the same larger structure—a nuance that would be missed by a single-scale analysis [34].

Benchmarking Criterion 3: Function

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Developmental Trajectory and Patterning

Functional benchmarking evaluates a model's capacity to execute developmental programs correctly, including the accurate progression through developmental stages and the establishment of fundamental body axes.

- Step 1: Pseudotime and Trajectory Inference: Using the scRNA-seq data from the model, apply trajectory inference algorithms such as Slingshot to order cells along a pseudotemporal continuum. This pseudotime represents an inferred developmental timeline from less to more differentiated states [17].

- Step 2: Transcription Factor Dynamics Analysis: Identify transcription factors whose expression is dynamically modulated along the inferred pseudotime. Use tools like SCENIC to analyze single-cell regulatory networks and infer transcription factor activity. Compare the timing and sequence of these regulatory events to those in the in vivo reference [17].

- Step 3: Axis Patterning Check: For models extending to gastrulation stages, assess the establishment of the anterior-posterior axis. This can involve imaging for asymmetric expression of patterning genes (e.g., by immunofluorescence or in situ hybridization) or scRNA-seq analysis to identify the presence and correct patterning of primitive streak cell populations [8] [17].

- Step 4: Functional Perturbation Assays: Test the model's response to genetic or chemical perturbations. For example, inhibit a key developmental pathway (e.g., WNT, BMP) and assess whether the model fails to form expected lineages or structures, thereby validating that the model's functional circuitry mirrors that of the natural embryo.

Key Analytical Tool: Trajectory Inference and Regulatory Network Analysis

Applying trajectory inference to the integrated human embryo reference has revealed key transcription factor dynamics along the three primary lineage trajectories (epiblast, hypoblast, and trophectoderm) [17]. For instance, along the epiblast trajectory, pluripotency markers like NANOG and POU5F1 are highly expressed in the pre-implantation epiblast but decrease post-implantation, while HMGN3 shows upregulated expression in later stages [17]. Similar analyses can be performed on embryo models to check if these critical regulatory transitions occur at the correct pseudotemporal point.

Table 3: Key Transcription Factor Dynamics in Early Human Lineages [17]

| Lineage Trajectory | Early-Stage Transcription Factors | Late-Stage Transcription Factors | Trajectory-Specific Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epiblast | DUXA, FOXR1, NANOG, POU5F1 |

HMGN3, VENTX |

ZSCAN10 |

| Hypoblast | DUXA, FOXR1, GATA4, SOX17 |

FOXA2, HMGN3 |

GATA4 |

| Trophectoderm | DUXA, FOXR1, CDX2, NR2F2 |

GATA2, GATA3, PPARG, HMGN3 |

NR2F2 |

Successfully conducting the benchmarking experiments outlined above requires a suite of specialized reagents, datasets, and computational tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Benchmarking Embryo Models

| Tool Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Integrated Human Embryo Transcriptome Atlas [17] | Gold-standard reference for scRNA-seq data projection and cell identity prediction. Covers zygote to gastrula. |

| Cell Lineage Markers | Validated Antibodies for ISL1, GABRP, TBXT, POU5F1 [17] | Immunostaining of tissue sections to validate spatial organization of key lineages (e.g., amnion, primitive streak, epiblast). |

| Spatial Omics Platforms | Xenium, MERFISH, seqFISH [34] | In situ gene expression analysis to map cell types and states within the intact spatial context of the embryo model. |

| Computational Tools | CRAWDAD R Package [34] | Quantifies cell-type spatial relationships (colocalization & separation) across multiple length scales from SRO data. |

| Developmental Inducers | Recombinant BMP4, WNT Agonists [8] | Used to pattern 2D micropatterned colonies and other embryo models to induce germ layer and lineage specification. |

| Trajectory Analysis Software | Slingshot, SCENIC [17] | Infers developmental pseudotime and reconstructs lineage trajectories from scRNA-seq data. |

Stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs) have emerged as transformative tools for studying early human development. Their usefulness in biomedical applications, including infertility research, disease modeling, and teratogen screening, hinges on a critical factor: their fidelity to in vivo human embryos. This guide benchmarks various embryo models against a new, comprehensive human embryo transcriptomic reference, providing an objective comparison of their performance in recapitulating human development. The data reveal that without such rigorous benchmarking, there is a substantial risk of misinterpreting results due to incomplete or inaccurate model systems [17].

A fundamental challenge in human developmental biology is the scarcity and limited accessibility of human embryos for research, compounded by ethical principles and legal regulations, such as the "14-day rule" [17] [8]. While animal models have been invaluable, significant species-specific differences in developmental pathways limit their ability to accurately predict human biology [8] [35].

To overcome these hurdles, researchers have developed a variety of stem cell-based human embryo models. However, the field has lacked an organized, integrated reference dataset to authoritatively determine how well these models mimic actual human development [17]. A universal reference is crucial for the validation and authentication of embryo models, moving beyond the limited verification offered by a handful of lineage markers to an unbiased, global assessment of transcriptional fidelity [17].

A Universal Human Embryo Reference for Model Authentication

Development of the Integrated Transcriptomic Roadmap

A significant advance is the creation of a comprehensive human embryogenesis transcriptome reference. This resource was built by integrating six publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets, creating a high-resolution roadmap of human development from the zygote to the gastrula stage (Carnegie stage 7) [17].

- Scope: The integrated dataset encompasses 3,304 early human embryonic cells, covering pre-implantation embryos, post-implantation blastocysts cultured in 3D, and an in vivo isolated Carnegie stage 7 gastrula [17].

- Standardization: All datasets were reprocessed using a standardized pipeline aligned to the same genome reference to minimize technical batch effects [17].

- Lineage Annotation: The reference provides detailed annotations for all major embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages, from the initial segregation of the inner cell mass and trophectoderm to the later specification of germ layers and specialized tissues like amnion and primordial streak [17].

Table: Key Features of the Integrated Human Embryo Reference

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Developmental Window | Zygote to Carnegie Stage 7 gastrula (approx. day 16-19) |

| Number of Cells | 3,304 individual embryonic cells |

| Data Type | Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) |

| Key Lineages Captured | Epiblast, Trophectoderm, Hypoblast, Primitive Streak, Amnion, Mesoderm, Endoderm, Hematopoietic progenitors |

| Primary Application | Benchmarking and authenticating stem cell-based embryo models |

The Embryogenesis Prediction Tool

To make this reference accessible, researchers created an online early embryogenesis prediction tool. This allows scientists to project their own scRNA-seq data from an embryo model onto the reference map. The tool then annotates the model's cells with predicted identities, providing an objective measure of its accuracy in recapitulating specific developmental stages and lineages [17].

Benchmarking Embryo Models for Teratogen Screening

Teratogen screening is a critical application where the predictive power of embryo models is paramount. Traditional animal models are costly, time-consuming, and can show species-specific responses that do not translate to humans [36] [35]. The following section compares the performance of several human stem cell-based assays, with a focus on how they recapitulate in vivo developmental processes.

Performance Comparison of Teratogen Screening Platforms

Table: Comparison of In Vitro Human Pluripotent Stem Cell (hPSC) Teratogen Screening Platforms

| Assay Platform | Principle / Readout | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastruloids (3D) [37] | Morphology & gene expression (e.g., SOX2, BRA, SOX17) in self-organizing structures | Proof-of-concept (Recapitulates known species-specificities) | Recapitulates gastrulation; medium-throughput; quantifiable; mimics species-specific sensitivity | Early-stage model; requires further validation with larger compound libraries |

| Micropatterned hPST (2D) [38] | Morphometric disruption of mesoendoderm patterns (Brachyury+ cells) | 97% Accuracy (100% Specificity, 93% Sensitivity on 30 compounds) | High-throughput; scalable; simplified morphometric readout | 2D architecture lacks 3D context of development |

| Stem Cell Monolayer [36] | Varies (e.g., metabolomics, immunocytochemistry for pluripotency/differentiation markers) | Varies by endpoint | Amenable to high-throughput screening; focuses on specific processes (e.g., self-renewal) | Disorganized structure; lacks morphogenic context; may miss complex teratogenic effects |

| Human Embryo Reference Tool [17] | Transcriptomic fidelity to in vivo human development | N/A (Benchmark, not an assay) | Unbiased, universal authentication; identifies lineage mis-specification | Does not directly predict teratogenicity; used to validate models for use in screening |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Micropatterned Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Test (µP-hPST)

This assay detects teratogens by their disruption of organized cell differentiation and migration [38].

- Micropatterning: Plate hPSCs (e.g., H9 line) as a confluent monolayer on circular, extracellular matrix-coated micropatterns.

- Mesoderm Induction & Compound Exposure: Culture cells for 3 days in mesoendoderm induction medium, supplemented daily with the test compound at a range of concentrations (e.g., covering IC25 cytotoxicity values and human plasma Cmax).

- Immunostaining: On day 3, fix cells and immunostain for the mesoendoderm marker Brachyury (T).

- Morphometric Analysis: Acquire fluorescent images and quantify morphological features of the T+ patterns (e.g., annular integrity, migration distance). The Lowest Disruption Concentration (LDC) is identified.

- Teratogen Classification: Apply a two-step classification rule based on the LDC and the compound's cytotoxicity thresholds (IC25 for hPSCs and adult human fibroblasts) [38].

Protocol 2: Gastruloid-based Teratogenicity Testing

Gastruloids are 3D aggregates that recapitulate gastrulation-like events [37].

- Gastruloid Generation: Generate mouse or human gastruloids from pluripotent stem cells using established 3D aggregation protocols.

- Compound Exposure: Expose gastruloids to reference compounds with known teratogenic risk during key developmental stages.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Quantitative Morphology: Image gastruloids and measure gross morphological effects, such as significantly reduced elongation or decreased size.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Use fluorescent reporters for genes like SOX2, BRA, and SOX17 to detect multi-lineage differentiation defects and disrupted axial patterning.

- Validation: Compare the responses of mouse and human gastruloids to known species-specific teratogens to validate the model's physiological relevance [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions