Best Practices for Storing Fixed Embryos for Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence: A Guide to Preserving Antigenicity and Tissue Integrity

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical aspects of storing fixed embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence (WM-IF).

Best Practices for Storing Fixed Embryos for Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence: A Guide to Preserving Antigenicity and Tissue Integrity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical aspects of storing fixed embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence (WM-IF). It covers foundational principles of how storage conditions impact antigen preservation and tissue morphology, detailed protocols for short and long-term storage of various model organisms, advanced troubleshooting strategies for common issues like high background and signal loss, and validation techniques to ensure staining reproducibility. By synthesizing current methodologies and optimization strategies, this resource aims to empower scientists to achieve consistent, high-quality results in their developmental biology and biomedical research.

The Science of Specimen Preservation: How Storage Impacts Immunofluorescence Outcomes

The Critical Link Between Fixation, Storage, and Epitope Integrity

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Signal and Background Issues

This guide addresses the most common challenges researchers face when storing fixed embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Staining | Over-fixation (epitope masking) [1] [2] [3] | Reduce fixation duration; employ antigen retrieval (HIER) [4]. |

| Inadequate permeabilization [1] [2] | Use methanol/acetone or add a detergent like 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 [5] [2]. | |

| Protein degradation due to under-fixation or delayed fixation [6] [4] | Ensure rapid and adequate fixation; use fresh fixative [6]. | |

| Antigen loss during long-term storage [1] | Use freshly prepared slides; image shortly after processing [1]. | |

| High Background Staining | Insufficient blocking [1] [2] [3] | Increase blocking incubation time; use serum from the secondary antibody host [1] [3]. |

| Antibody concentration too high [1] [2] | Titrate primary and/or secondary antibody to optimal dilution [1]. | |

| Sample autofluorescence [1] [2] [3] | Use unstained controls; avoid glutaraldehyde; use fresh formaldehyde [1]. | |

| Insufficient washing [1] [2] | Increase wash duration and volume between staining steps [1]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Morphology and Preservation Issues

This guide focuses on problems related to the preservation of tissue architecture during fixation and storage.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Tissue Morphology | Fixative penetration issues [6] [4] | Ensure tissue is thin (<10 mm); use fixative volume 50-100x tissue volume [6]. |

| Use of inappropriate fixative for target [7] [5] | Choose cross-linking (e.g., PFA) for structure; precipitating (e.g., TCA) for some epitopes [5]. | |

| Tissue degradation before fixation [4] | Minimize delay between dissection and fixation; consider perfusion fixation [6]. | |

| Loss of Delicate Structures | Over-digestion with protease (e.g., Proteinase K) [8] | Optimize or omit protease digestion; use gentler acid-based permeabilization [8]. |

| Physical damage from harsh processing [8] | Use tailored protocols (e.g., NAFA) for fragile tissues like blastemas [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental impact of fixation on epitope integrity? Fixation is a balancing act. Its primary goal is to preserve tissue morphology and prevent proteolytic degradation by stabilizing biomolecules [7] [6]. However, the process itself can chemically alter proteins. Under-fixation fails to protect antigens, leading to their loss [6] [4]. Conversely, over-fixation, particularly with cross-linking fixatives like formaldehyde, can create excessive molecular cross-links that physically mask the epitope, preventing antibody binding [7] [6] [4].

Q2: How does the choice between PFA and TCA fixatives affect my experiment? The choice significantly impacts your results. Paraformaldehyde (PFA) is a cross-linking fixative that excellently preserves tissue architecture and is optimal for nuclear antigens [7] [5]. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) is a precipitating fixative that denatures and aggregates proteins. It can alter the appearance of subcellular localization and sometimes reveal epitopes that are inaccessible with PFA, making it potentially better for some cytoskeletal or membrane proteins [5]. TCA fixation has been shown to result in larger, more circular nuclei compared to PFA [5].

Q3: What are the best practices for storing fixed embryos before immunostaining? To preserve epitope integrity, fixed samples should be stored in buffered solutions like PBS or TBS, often at 4°C [5]. For long-term storage, transferring fixed tissues to 70% alcohol until processing can help maintain antigenicity [4]. It is crucial to avoid prolonged storage of fixed samples, as antigenicity can fade over time. Samples should be processed and imaged as soon as possible after staining, mounting them with an anti-fade reagent [1].

Q4: How can I "rescue" an epitope that has been masked by over-fixation? Antigen retrieval techniques are designed to reverse the epitope masking caused by fixation. The most common method is Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER), which involves heating tissue sections in a buffer (e.g., citrate pH 6.0 or EDTA pH 8.0) to break cross-links and unwind proteins [4] [9]. An alternative method is Enzymatic-Induced Epitope Retrieval (EIER), which uses proteases like trypsin to digest proteins and expose epitopes [4]. The optimal method and buffer must be determined empirically for each target.

Q5: Why is standardization of fixation protocols so important? Variability in fixation protocols between institutions is a major source of inconsistent and unreliable results [7] [4]. Factors such as fixation time, temperature, pH, and fixative concentration can dramatically affect epitope integrity and staining outcomes. Standardizing these parameters, along with the use of robust positive and negative controls, is essential for achieving reproducible data, especially in clinical and multi-center research settings [7] [4].

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Fixatives for Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence

The following detailed protocol, adapted from a 2024 preprint, allows for the systematic comparison of PFA and TCA fixation on chicken embryos [5].

1. Sample Preparation

- Incubate fertilized chicken eggs at 37°C to the desired Hamburger and Hamilton (HH) stage.

- Dissect embryos and place them onto filter paper in Ringer's Solution.

2. Fixation Methods

- Paraformaldehyde (PFA) Fixation:

- Fix embryos in 4% PFA in 0.2M phosphate buffer for 20 minutes at room temperature [5].

- Post-fixation, wash in Tris-Buffered Saline or Phosphate-Buffered Saline containing 0.1–0.5% Triton X-100 (TBST or PBST).

- Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) Fixation:

- Fix embryos in 2% TCA in PBS for 1–3 hours at room temperature [5].

- Wash in TBST or PBST after fixation.

3. Immunostaining

- Blocking: Incubate embryos in PBST or TBST containing 10% donkey serum for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate in diluted primary antibody (see Table 2 in the preprint for examples) for 72–96 hours at 4°C [5].

- Washing: Wash embryos thoroughly in PBST or TBST.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (e.g., AlexaFluor, diluted 1:500) overnight at 4°C.

- Final Wash: Wash embryos in buffer.

- Post-fixation (for PFA-only): PFA-fixed embryos may be post-fixed with PFA for 1 hour at room temperature to stabilize the signal [5].

4. Mounting and Imaging

- Mount samples in an anti-fade mounting medium.

- Image immediately for optimal results [1].

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from a study comparing PFA and TCA fixation in chicken embryos [5].

| Fixative Type | Fixation Duration | Nuclear Morphology | Optimal For Epitope Localization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4% PFA (Cross-linking) | 20 minutes | Smaller, less circular [5] | Nuclear transcription factors (e.g., SOX9, PAX7) [5] | Excellent tissue preservation; may mask some epitopes requiring antigen retrieval [5] [4]. |

| 2% TCA (Precipitating) | 1-3 hours | Larger, more circular [5] | Cytoskeletal (e.g., Tubulin) & membrane proteins (e.g., Cadherin) [5] | Can alter subcellular localization; may damage delicate structures [5]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents essential for successful fixation and staining, along with their primary functions.

| Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative; preserves tissue architecture by forming methylene bridges between proteins [7] [6]. | Standard fixation for whole-mount embryos; optimal for nuclear antigens [5]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Precipitating fixative; denatures and aggregates proteins via acid-induced coagulation [5]. | Accessing hidden epitopes in cytosolic and membrane proteins [5]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent; permeabilizes cell membranes to allow antibody penetration [5] [2]. | Added to wash buffers (0.1-0.5%) after aldehyde fixation to permeabilize cells [5]. |

| Donkey Serum | Blocking agent; reduces non-specific background staining by saturating reactive sites [5] [3]. | Used at 10% concentration in buffer to block embryos before antibody incubation [5]. |

| Sodium Borohydride | Reducing agent; quenches free aldehyde groups to reduce autofluorescence [2]. | Wash with 0.1% in PBS after aldehyde fixation to lower background [2]. |

| Citrate/EDTA Buffer | Antigen retrieval buffer; reverses formaldehyde-induced cross-links under heat [4] [9]. | Heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) for over-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples [4] [9]. |

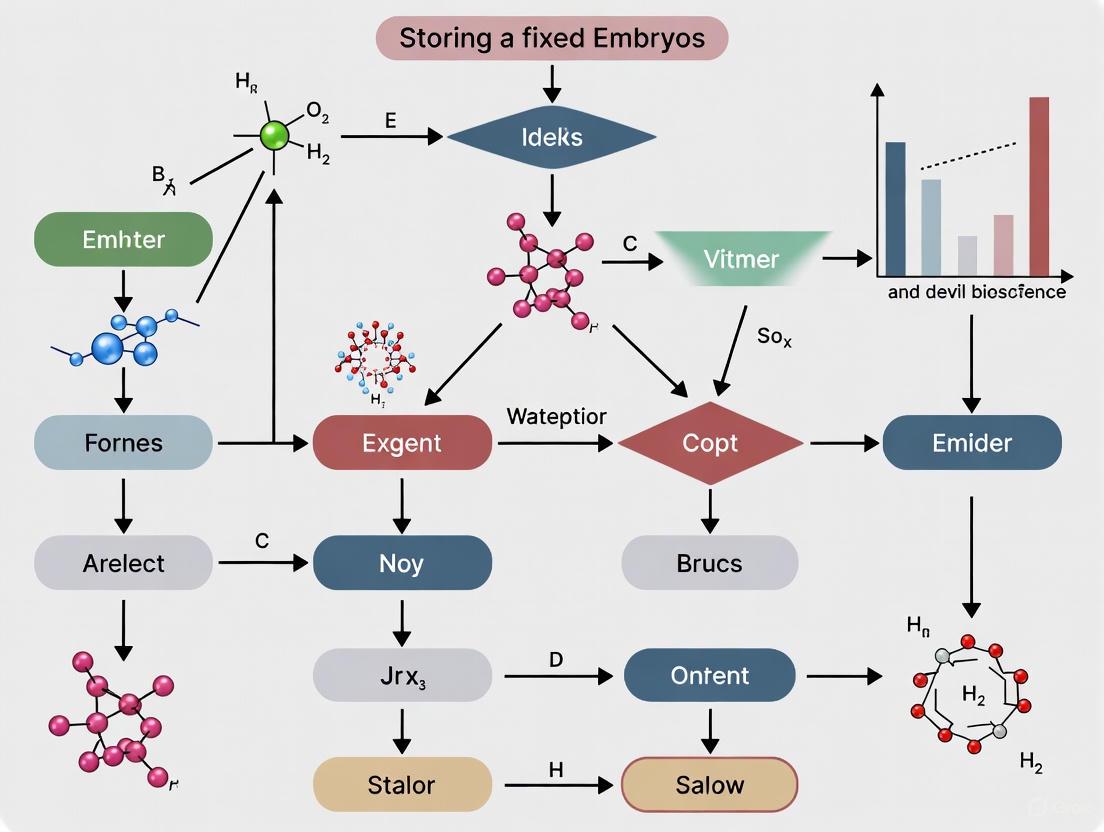

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Fixation and Storage Impact on Epitopes

Fixation Selection Decision Guide

For researchers conducting whole mount immunofluorescence on fixed embryos, proper storage is not merely a matter of sample preservation but a critical determinant of experimental success. Improperly stored samples are susceptible to two primary, interconnected issues that can compromise data integrity: the degradation of protein epitopes and the induction of autofluorescence. Epitope degradation diminishes the specific antibody signal, while autofluorescence increases background noise, collectively destroying the signal-to-noise ratio essential for high-quality imaging. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices to help you safeguard your samples and ensure the reliability of your research outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Storage-Related Issues

Q1: My immunofluorescence images have high background noise, making specific signal difficult to distinguish. Could this be related to how my fixed embryos are stored?

Yes, high background is a frequent consequence of improper storage. A primary cause is autofluorescence, which can be induced or exacerbated by several storage-related factors:

- Fixative-Related Autofluorescence: Using aldehydes like paraformaldehyde (PFA) is standard, but the chemical reactions between aldehydes and amines in proteins can generate fluorescent products. This is particularly problematic with over-fixation or if a "quenching" step is omitted after fixation [10].

- Storage Buffer and Duration: Prolonged storage, especially in buffers containing certain salts or at non-optimal pH, can increase background fluorescence over time. While specific studies on embryo storage duration are limited, the principles of protein and tissue integrity dictate that long-term storage should be approached with caution and validated.

How to Fix It:

- Quenching: After aldehyde fixation, incubate your samples with reagents that quench the unreacted aldehyde groups. Common quenching agents include 100mM glycine or 1% sodium borohydride in PBS [10].

- Optimized Storage Buffer: Store fixed samples in a neutral, isotonic buffer like PBS at 4°C. The addition of a preservative like 0.01% sodium azide can prevent microbial growth. For long-term storage, consider freezing at -20°C in an antifreeze solution, but be aware that freeze-thaw cycles can damage tissue morphology.

- Use Appropriate Controls: Always include a control sample stained only with the secondary antibody. This will help you determine the threshold of background signal specific to your storage conditions [10].

Q2: I am getting a weak or absent specific signal despite using a validated antibody. Could epitope degradation during storage be the cause?

Absolutely. A weak or absent signal often points to epitope degradation or masking. Epitopes are the specific regions on antigens recognized by antibodies. During storage, several processes can negatively impact them:

- Protein Denaturation and Modification: Over time, even fixed proteins can undergo subtle conformational changes or chemical modifications that destroy the antibody-binding site. Inadequate fixation can allow proteolytic enzymes to remain active, gradually degrading the target protein [10].

- Epitope Masking: The fixation process itself can cross-link proteins, potentially burying the epitope and making it inaccessible to the antibody. This is more likely with over-fixation.

How to Fix It:

- Optimize Fixation Protocol: Ensure fixation is sufficient but not excessive. A typical protocol is 10-20 minutes at room temperature with 2%-4% PFA for cell cultures, though tissues like embryos may require longer [10]. Test different fixation times for your specific antigen.

- Antigen Retrieval: For masked epitopes, employ antigen retrieval techniques after storage. This typically involves heating the samples in a buffered solution (e.g., citrate buffer) or using enzymatic digestion (e.g., proteinase K) to break cross-links and reveal hidden epitopes.

- Ensure Proper Permeabilization: If your target is intracellular, antibodies cannot access it without permeabilization. After storage and before staining, permeabilize your embryos with a detergent like 0.1%-0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the best temperature for storing fixed embryos for long-term immunofluorescence studies? A: For short-term storage (days to a few weeks), fixed embryos can typically be kept in PBS at 4°C. For long-term storage (months to years), freezing at -20°C is recommended. However, the optimal protocol can be antigen-dependent. Freezing can cause ice crystal formation that disrupts morphology, so using a cryoprotectant solution is advised. You must empirically test the stability of your specific antigens under your chosen storage conditions.

Q: How does the choice of fixative influence long-term storage and autofluorescence? A: The fixative choice is a critical initial decision that impacts long-term sample quality.

- Aldehydes (PFA/Glutaraldehyde): Provide excellent structural preservation but are a major cause of chemical-induced autofluorescence, which can intensify with storage time. Quenching is essential [10].

- Organic Solvents (Methanol/Acetone): Precipitate proteins and are less likely to cause the same type of autofluorescence as aldehydes. They also permeabilize cells, eliminating the need for a separate permeabilization step. However, they may not preserve certain epitopes or cellular structures as well as PFA and can extract lipid-soluble components [10].

Q: Can I store my stained embryos and re-image them later? What are the risks? A: Yes, but with precautions. Mounted samples should be sealed with nail polish to prevent drying and stored in the dark at -20°C or +4°C [10]. The primary risks are fluorophore bleaching and potential sample degradation over time. For quantitative comparisons, it is best to image all samples within a single experiment using the same imaging settings to minimize variability.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Assessing Autofluorescence in Stored Samples

Purpose: To quantify and identify the level of autofluorescence in fixed embryo samples after different storage conditions.

Materials:

- Fixed embryo samples (stored under various conditions: e.g., 4°C vs. -20°C, different buffers)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Mounting medium with anti-fading agents

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Confocal or fluorescence microscope

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Take a subset of fixed embryos from each storage condition. Do not stain them with any primary or secondary antibodies.

- Mounting: Mount the unstained samples on slides using an anti-fade mounting medium.

- Imaging: Image the samples using the exact same laser lines and detection settings you would use for your actual immunofluorescence experiment.

- Analysis: The signal detected in these unstained samples is the autofluorescence. Compare the intensity and distribution across different storage conditions. This will establish a baseline background for your experiment.

Protocol 2: Validating Epitope Integrity After Storage

Purpose: To confirm that a specific antigen of interest remains detectable and produces a strong signal after a period of storage.

Materials:

- Fixed embryo samples (freshly fixed vs. stored)

- Validated primary antibody against your target

- Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody

- Blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.1-0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS)

- Washing buffer (e.g., PBS Tween-20)

- Counterstain (e.g., DAPI)

- Mounting medium

Method:

- Parallel Staining: Process a freshly fixed embryo and a stored embryo for immunofluorescence simultaneously, using the same antibody solutions and incubation times.

- Standard Staining Procedure:

- Permeabilize and block samples.

- Incubate with primary antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) for 1-2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [10].

- Wash extensively with a buffer like PBS Tween-20 to reduce unspecific binding [10] [11].

- Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Wash extensively again.

- Counterstain with DAPI and mount.

- Analysis: Image both samples with identical microscope settings. A significant reduction in specific signal intensity in the stored sample compared to the fresh control indicates a loss of epitope integrity due to storage.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key reagents used to prevent or mitigate storage-related issues in immunofluorescence.

| Reagent | Function | Example Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [10] | Cross-linking fixative that preserves cellular structure. | Typically used at 2-4%. Over-fixation can increase autofluorescence and mask epitopes. |

| Methanol [10] | Precipitating fixative. | Can be used cold (-20°C). Less associated with chemical autofluorescence but may not preserve all epitopes. |

| Triton X-100 [10] | Non-ionic detergent for permeabilization. | Used at 0.1-0.2% to allow antibody access to intracellular targets after storage. |

| Glycine / Sodium Borohydride [10] | Quenching agents. | Used after aldehyde fixation to reduce autofluorescence by neutralizing unreacted aldehyde groups. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [10] | Blocking agent. | Used at 1-5% to block non-specific antibody binding sites, reducing background. |

| Sodium Azide | Preservative. | Added to storage buffers (e.g., at 0.01%) to inhibit microbial growth during long-term storage at 4°C. |

Visualizing the Impact of Storage on Sample Quality

The following diagram illustrates the two main pathways through which improper storage compromises immunofluorescence results and the key interventions to prevent them.

FAQs: Storage Solutions for Fixed Embryos

Q1: Why is the osmolality of my embryo storage solution increasing over time, and how can I prevent it? Evaporation is a primary cause of rising osmolality, which can impair embryo development. The type of incubator and covering oil used are critical factors. Research shows that using a humidified incubator is significantly better at maintaining stable osmolality over a 7-day culture period compared to a dry incubator. Furthermore, when using a dry incubator, paraffin oil offers superior protection against evaporation for single-step media compared to mineral oil [12]. Ensuring an adequate volume of oil overlay and using culture dishes with designs that minimize evaporation are also effective strategies [13].

Q2: What pH buffer should I use in handling media for procedures outside the incubator? For procedures performed outside a CO₂ incubator, such as embryo transfer or cryopreservation, media containing only bicarbonate buffers are insufficient. Biological zwitterionic buffers, known as "Good's buffers," are essential for stabilizing pH in room air [14]. The table below summarizes common buffers and their properties.

| Buffer Name | pKa at 37°C | Notes on Use with Embryos |

|---|---|---|

| HEPES | 7.31 | Commonly used; provides effective buffering in handling media [14]. |

| MOPS | 6.93 | Appropriate for use near neutral pH [14]. |

| TAPSO | 7.39 | pKa is well-suited for embryonic culture; noted as potentially appropriate [14]. |

| Tris | 7.82 | pKa is relatively high for embryo culture; use with caution [14]. |

Q3: How can the choice of fixative and storage method affect my whole-mount immunofluorescence results? The fixation and storage process is critical for preserving antigenicity and tissue structure.

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) is the most common fixative for whole-mount embryos. However, the protein cross-linking it causes can mask some epitopes. If staining is weak with PFA, methanol can be an alternative fixative that may improve antibody access [15].

- Storage: After fixation, embryos can be stored long-term in 100% methanol at -20°C [16]. For some embryos, such as Drosophila, storage in ethanol at -20°C is also effective [17]. Proper storage prevents degradation and preserves samples for future staining.

Q4: What are the common causes of high background in whole-mount immunofluorescence? High background staining is often due to non-specific antibody binding or tissue autofluorescence. Key solutions include [18] [3] [19]:

- Insufficient blocking: Extend the blocking time or optimize your blocking solution (e.g., using serum from the secondary antibody host).

- Antibody concentration too high: Titrate your primary and secondary antibodies to find the optimal concentration.

- Inadequate washing: Increase the duration and number of washing steps.

- Autofluorescence: Use unstained controls to check for inherent tissue fluorescence. Using fresh aldehyde fixatives and mounting media with anti-fade agents can help reduce this.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Over-fixation with PFA leading to epitope masking. | Switch to methanol fixation or reduce PFA fixation time [15]. |

| Inadequate permeabilization preventing antibody penetration. | Optimize permeabilization agent concentration and incubation time [3]. | |

| Low antigen expression or primary antibody issues. | Use a positive control; validate antibody and increase concentration if needed [18]. | |

| Rising Osmolality | Evaporation due to low-humidity incubation. | Use a humidified incubator and ensure a proper seal on culture dishes [12] [13]. |

| Insufficient or inappropriate oil overlay. | Use paraffin oil, which is heavier and provides better evaporation protection than mineral oil [12]. | |

| High Background Signal | Non-specific antibody binding. | Optimize blocking conditions; include normal serum from the secondary antibody species [19]. |

| Endogenous enzymes or biotin activity. | Quench endogenous peroxidases with H₂O₂ or block endogenous biotin with a commercial kit [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Fixation and Storage of Embryos for Whole-Mount Studies

This protocol, adapted from established methods, details the fixation and storage of zebrafish or similar vertebrate embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence [16].

Materials Needed:

- Embryo wash buffer (e.g., PBS)

- 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile

- 100% Methanol

- Embryo mesh baskets

- 50 mL conical tubes

- Platform shaker (optional)

Procedure:

- Collection and Washing: Collect embryos in a 50 mL conical tube. Remove culture water and wash embryos thoroughly with ice-cold sterile PBS.

- Fixation: Add 25 mL of ice-cold 4% PFA to the tube. Fix embryos for 24 hours at 4°C. If available, perform this step on a gentle rocker to ensure even fixation.

- Post-Fixation Wash: Carefully decant the PFA and wash the embryos three times with sterile PBS, for 7 minutes per wash.

- Dehydration and Storage: Decant the final PBS wash and add 25 mL of 100% methanol. Invert the tube several times. The embryos will sink to the bottom.

- Replace with fresh 100% methanol. Store the embryos at -20°C for up to one year [16].

Note: For immunofluorescence, re-hydrate embryos incrementally through a methanol:PBS series (e.g., 3:1, 1:1, 1:3) before proceeding to staining [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves cellular structure. | Standard for morphology; may mask some epitopes. Use at 4% concentration [15] [16]. |

| Methanol | Precipitating fixative and storage medium. | An alternative to PFA; can improve antibody penetration for some targets [15]. |

| HEPES Buffer | Zwitterionic biological pH buffer. | Used in handling media to stabilize pH outside a CO₂ incubator [14]. |

| Paraffin Oil | Overlay to prevent evaporation. | Superior to mineral oil at reducing media evaporation and osmolality shifts in dry incubators [12]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking agent and protein stabilizer. | Reduces non-specific antibody binding in blocking and antibody dilution buffers [19]. |

Workflow Diagram: Embryo Storage and Staining Pathway

The following diagram outlines the key decision points and steps in the process of preparing and storing embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence.

For researchers working with fixed embryos in whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF), the integrity of your data is directly linked to your sample storage practices. A poorly stored sample can lead to diminished antigenicity, resulting in weak or false-negative signals, wasted resources, and inconclusive experiments. This guide addresses the critical, yet often overlooked, relationship between storage duration, conditions, and the preservation of antigenicity, providing evidence-based troubleshooting and protocols to safeguard your research outcomes.

FAQs on Storage and Antigenicity

Q1: What is the direct impact of long-term slide storage on immunofluorescence signal intensity?

Systematic studies have shown that while optimally fixed tissues are resilient, long-term storage of prepared slides can lead to a slight but significant decrease in IF signal intensity for certain antigens. The most critical factor is not time alone, but the primary antibody itself. Research on tissue microarrays found that four out of twelve antibodies tested showed no significant changes after one year of storage, while eight others exhibited limited decreases detectable by image analysis [20]. The subcellular localization of the antigen (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic/membranous) did not significantly influence its degradation rate [20].

Q2: What is the best way to store prepared slides to preserve antigenicity?

The storage condition plays a key role in preserving signal. The same long-term study compared different storage methods and found that refrigeration at 4°C proved to be the overall best procedure [20]. While storing slides coated with a protective layer of paraffin wax was also tested, no major advantages were found over uncoated slides when combined with optimal storage temperature [20].

Q3: How does the choice of fixative influence how I should store my samples?

The fixative fundamentally alters the tissue's chemical nature, which impacts storage strategy. Paraformaldehyde (PFA) works by creating cross-links between proteins, which generally creates a stable matrix that is resilient to long-term storage when properly prepared [5] [20]. In contrast, Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) fixes by precipitating proteins through acid-induced denaturation and coagulation [5]. This different mechanism does not form the same stable cross-linked network, but its impact on long-term storage stability for whole-mount embryos is less defined and requires further empirical validation.

Q4: Can antigen retrieval reverse the damage caused by prolonged storage?

Yes, effectively. Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) is a powerful technique to restore antigenicity masked by fixation and potentially degraded by storage [20] [21]. The process of heating sections in specific buffers (e.g., citrate pH 6.0 or Tris-EDTA pH 9.0) helps break methylene cross-links formed during formalin/PFA fixation and can often recover epitopes, making them accessible to antibodies once more [21]. The success of this retrieval depends on using the correct buffer pH and heating method optimized for your specific antigen [22] [21].

Key Data and Comparisons

Comparative Analysis of Fixative Impact on Antigenicity

Table 1: Impact of common fixatives on antigen preservation and morphology in embryonic tissues.

| Fixative Agent | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Tissue Morphology | Impact on Antigenicity | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Creates protein-protein cross-links [5]. | Preserves tissue architecture excellently [5]. | Good for a wide range of antigens; optimal for nuclear transcription factors (e.g., SOX9, PAX7) [5] [23]. | Nuclear proteins; general morphology studies [5] [23]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Precipitates proteins via acid denaturation [5]. | Alters morphology; results in larger, more circular nuclei [5] [23]. | Can alter/unmask epitopes; may be superior for some cytoskeletal (Tubulin) and membrane proteins (Cadherins) [5] [23]. | Hidden epitopes; specific cytosolic and membrane targets [5]. |

Impact of Storage Conditions on Signal Detection

Table 2: Effects of long-term slide storage on the detection of various biomarkers.

| Biomarker Type | Storage Duration | Key Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins (IHC/IF) | Up to 1 year | Slight but significant changes for some, but not all, antibodies. No major difference between nuclear and cytoplasmic/membranous antigens [20]. | Test antibody sensitivity to storage. Store slides at 4°C. Use robust antigen retrieval [20]. |

| mRNA (In Situ Hybridization) | Up to 1 year | mRNA can be degraded over time on stored slides, making detection difficult [20]. | For mRNA studies, use freshly cut sections wherever possible. |

| DNA (FISH/CISH) | Up to 1 year | Gene copy number aberrations and chromosomal translocations remain detectable on slides stored for up to one year [20]. | Long-term storage is generally feasible for DNA-based assays. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating Antigen Stability in Stored Samples

Purpose: To systematically test the effect of your storage conditions on the antigenicity of your target proteins in fixed whole-mount embryos.

Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Fix a batch of embryos (e.g., chicken or zebrafish) simultaneously using your standardized PFA protocol to ensure uniformity [5] [22].

- Storage Cohorts: Divide the fixed and washed embryos into several groups. For whole-mount samples, store them in PBS with 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C [22].

- Time-Points: Process a subset of embryos for whole-mount IF at defined intervals (e.g., immediately, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months).

- Staining and Analysis: Perform IF under identical conditions for all time-points. Use consistent imaging parameters and quantify the mean fluorescence intensity of your target antigen relative to a background region.

- Include Controls: Always include a positive control (a freshly fixed and stained sample) to benchmark any signal loss.

Protocol: Heat-Induced Antigen Retrieval (HIER) for Restoring Signal

Purpose: To recover antigenicity that has been masked by fixation or diminished during storage [20] [21].

Materials:

- Sodium citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) or Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) [21].

- Laboratory microwave, pressure cooker, or vegetable steamer.

- Coplin jars or microwaveable slide containers.

Steps:

- Deparaffinize and Rehydrate: If using paraffin-embedded sections, follow standard deparaffinization and rehydration steps.

- Choose Buffer: Select retrieval buffer based on the primary antibody's recommendation. Citrate pH 6.0 and Tris-EDTA pH 9.0 are the most common [21].

- Heat Retrieval:

- Pressure Cooker Method: Bring the buffer to a boil in a pressure cooker. Place slides in the buffer, secure the lid, and once full pressure is reached, time for 3 minutes. Cool rapidly under cold water [21].

- Microwave Method: Place slides in a container with retrieval buffer and heat in a microwave until boiling. Continue heating at a sub-boiling temperature for 20 minutes. Ensure slides do not dry out [21].

- Steamer Method: Place a container with slides and pre-heated buffer in a vegetable steamer for 20 minutes [21].

- Cooling: After heating, allow the slides to cool in the buffer for at least 20-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash and Proceed: Rinse slides with distilled water and proceed with your standard IF protocol [21].

Visual Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for optimizing antigen preservation and detection.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative for preserving tissue morphology and structural epitopes [5]. | Use freshly prepared or freshly thawed aliquots. Aged PFA adversely affects nuclear factor detection [24]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Precipitating fixative that can unmask hidden epitopes for certain proteins [5] [23]. | Alters nuclear and tissue morphology. Ineffective for mRNA visualization via HCR [23]. |

| Sodium Azide | Antimicrobial agent to prevent microbial growth in stored samples [22]. | Add to PBS (e.g., 0.1%) for long-term storage of fixed whole-mount embryos at 4°C [22]. |

| Triton X-100 / Tween-20 | Detergent for tissue permeabilization, allowing antibody penetration [5] [22]. | Increase concentration to 1% for dense tissues like whole-mount retina [22]. |

| Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval Buffers | To break cross-links and unmask antigens lost during fixation or storage [21]. | Citrate (pH 6.0) and Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) are most common. Optimal pH is antigen-dependent [21]. |

| Normal Donkey Serum | Component of blocking solution to reduce non-specific antibody binding [5] [24]. | Use the same species as your secondary antibody host for effective blocking. |

Practical Protocols for Optimal Short and Long-Term Embryo Storage

Purpose and Scope

This Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) outlines the protocols for the handling and initial storage of fixed embryos intended for whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF) research. Proper execution of these steps is critical for preserving tissue morphology, preventing antigen degradation, and ensuring high-quality staining outcomes. This protocol is designed for researchers working with murine and pre-implantation embryo models.

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Post-Fixation Handling and Storage

| Reagent/Material | Function | Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [24] [25] | Primary fixative; cross-links proteins to preserve tissue structure. | Use 1-4% solutions. Prepare fresh or use stocks <7 days old. Store at 4°C [24]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [24] [26] | Isotonic washing and dilution buffer; removes fixative residue. | With or without Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ as required by the protocol [24]. |

| PBS-Glycine [26] | Quenches unreacted aldehydes from PFA fixation to reduce background. | Used post-fixation before proceeding to storage or staining [26]. |

| Sucrose Solution [25] | Cryoprotectant; reduces ice crystal formation during freezing. | Tissues are incubated in sucrose (e.g., 15-30%) after fixation until they sink [25]. |

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (O.C.T.) Compound [25] | Water-soluble embedding medium for cryosectioning. | Used to embed tissues prior to snap-freezing [25]. |

| Isopentane (2-Methylbutane) [25] | Coolant for rapid snap-freezing of samples at ~-176°C. | Pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen; minimizes destructive ice crystals [25]. |

| Fructose-Glycerol Clearing Solution [26] | Mounting medium that improves tissue transparency for imaging. | An alternative to commercial mounting media; preserves fluorescence [26]. |

Procedure

Post-Fixation Quenching and Washing

- Transfer Fixed Embryos: Using fine forceps or a glass pipette, carefully transfer the fixed embryos from the fixative solution into a clean well or watch glass.

- Rinse: Wash the embryos with 1X PBS to remove the bulk of the fixative.

- Quench: Incubate the embryos in a freshly prepared PBS-Glycine solution (e.g., 0.1 M Glycine in PBS) for 15-30 minutes at room temperature to neutralize residual aldehydes [26].

- Final Washes: Perform three 5-minute washes in a sufficient volume of 1X PBS to ensure complete removal of the glycine and any trace fixative.

Initial Storage Setup

The choice of storage method depends on the subsequent experimental workflow.

A Short-Term Storage in PBS

- Application: For samples that will be processed for immunofluorescence within two weeks [27].

- Procedure:

- After the final PBS wash, transfer the embryos to a sterile vial or tube containing 1X PBS.

- Ensure the samples are completely submerged.

- Store at 4°C.

B Short-Term Storage in Ethanol

- Application: For long-term storage of fixed specimens, particularly for histological purposes [27].

- Procedure:

- Dehydrate the fixed and washed embryos through a series of graded ethanol baths (e.g., 50%, 70%, 95%).

- Store the embryos in 70% ethanol at room temperature [27].

C Cryopreservation for Sectioning or Staining

- Application: For optimal preservation of antigenicity and for samples intended for cryosectioning [25].

- Procedure:

- Cryoprotection: After washing, incubate the embryos in a 15-30% sucrose solution in PBS at 4°C until the samples sink (indicating saturation).

- Embedding:

- Place a small amount of O.C.T. compound in a labeled cryomold.

- Transfer the embryo into the O.C.T. and orient it correctly.

- Carefully top up the cryomold with more O.C.T., avoiding air bubbles.

- Snap-Freezing:

- Slowly lower the cryomold into a bath of isopentane pre-cooled by liquid nitrogen until the O.C.T. is completely frozen.

- CRITICAL: Do not submerge the sample directly into liquid nitrogen [25].

- Long-Term Storage:

- Wrap the frozen block in aluminum foil and transfer it to a -80°C freezer for long-term storage.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram summarizes the key decision points and pathways after embryo fixation.

Troubleshooting and FAQs

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Post-Fixation Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Staining [28] [29] [30] | Antigen degradation due to long or improper storage. | For short-term storage in PBS, do not exceed 2 weeks [27]. For long-term, use cryopreservation at -80°C [25]. |

| High Background [28] [29] | Inadequate washing post-fixation; residual aldehydes. | Ensure thorough washing and include a quenching step with glycine after fixation [26]. |

| Poor Tissue Morphology [30] | Ice crystal damage during freezing. | Use adequate cryoprotection (sucrose) and snap-freeze in pre-cooled isopentane, not directly in liquid nitrogen [25]. |

| Tissue Autofluorescence [28] [29] | Autofluorescence induced by aldehyde fixatives. | Avoid glutaraldehyde. Use fresh PFA. A post-fixation wash with sodium borohydride (0.1% in PBS) can reduce this [28] [29]. |

| Sample Deterioration in Storage | Bacterial or enzymatic degradation. | Ensure samples are fully submerged in storage solution. Adding a very low concentration of sodium azide (NaN₃, e.g., 0.0048 μg/mL in 1X buffer) to PBS can prevent microbial growth [26]. CRITICAL: NaN₃ is highly toxic; handle with extreme care [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the purpose of sodium azide in the PBS storage solution? Sodium azide is added to Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) as a preservative to prevent microbial or bacterial growth in stored fixed samples. For tissue planned to be stored in a refrigerator (4°C) for over three weeks, the use of PBS with 0.01% sodium azide is recommended [31].

2. Why is a 30% sucrose solution used prior to freezing samples? Sucrose is used as a cryoprotectant. It helps to protect against freezing artifacts by displacing water within the tissue, which reduces the formation of damaging ice crystals during the freezing process. Specimens are equilibrated in the sucrose solution until they sink to the bottom of the container, indicating full penetration [32] [33].

3. Can I store my fixed embryos directly in PBS, and for how long? Yes, fixed samples can be stored in PBS or PBS-T (PBS with Tween 20) at 2-8°C for extended periods. One protocol specifies storing fixed organoids in PBS-T at 2-8°C for up to one week [33]. Another source indicates that PBS with 0.01% sodium azide should be used for tissue stored for over three weeks at 4°C [31].

4. My immunofluorescence background is high. What could be the cause? High background can result from several factors:

- Inadequate Blocking: Ensure you are using an appropriate blocking buffer, such as one containing 5% serum from the same species as your secondary antibody host, for a sufficient time (30 minutes to 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C) [34] [33].

- Insufficient Washing: Perform multiple thorough washes (e.g., 3x for 10-15 minutes each) with a wash buffer like PBS-T after each antibody incubation step [32] [34].

- Over-fixation: Excessive fixation can mask epitopes and increase non-specific background staining [32].

5. My sample morphology is poor after sectioning. How can I improve this? Poor morphology can often be traced to the fixation and cryoprotection steps:

- Fixation: Use freshly prepared paraformaldehyde (PFA) for optimal results. Under-fixation can lead to poor structural preservation [33].

- Cryoprotection: Ensure complete equilibration in the 30% sucrose solution before attempting to freeze the sample. The tissue should no longer float in the sucrose solution [33].

- Freezing Method: Snap-freezing the sample rapidly helps prevent the formation of ice crystals that disrupt cellular architecture. This can be done using a dry ice/ethanol slurry or isopentane chilled with liquid nitrogen [32] [33].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Contamination | Storage solution lacks preservative. | Add 0.01% sodium azide to PBS for long-term storage (>3 weeks) [31]. |

| High Background Staining | Non-specific antibody binding or insufficient washing. | Optimize blocking conditions (e.g., 5% serum); Increase wash frequency/duration; Titrate primary antibody concentration [32] [34]. |

| Poor Tissue Morphology | Incomplete cryoprotection; Slow freezing. | Equilibrate in 30% sucrose until tissue sinks; Use a snap-freezing method (dry ice/ethanol slurry) [33]. |

| Weak or No Signal | Epitope masked by over-fixation. | Perform antigen retrieval (e.g., heat-induced epitope retrieval with citrate buffer) [32] [33]. |

| Tissue Damage/Loss | Sample not adequately adhered to slide; Rough handling. | Use gelatin-coated slides for better adhesion; Handle samples gently with cut pipette tips [32] [33]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents used in the short-term storage and processing of fixed embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence.

| Reagent | Function | Example Formulation & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Fixative: Cross-links proteins to preserve tissue structure and antigenicity. | 2-4% in PBS. For best results, use freshly prepared from powder or frozen aliquots [33] [26]. |

| PBS with Azide | Storage Buffer: Provides an isotonic environment for storage; azide inhibits microbial growth. | 1X PBS with 0.01% sodium azide. Ideal for refrigerated storage for several weeks [31]. |

| Sucrose | Cryoprotectant: Penetrates tissue and reduces ice crystal formation during freezing. | 30% (w/v) in PBS. Specimens are equilibrated until they sink [33]. |

| Triton X-100 | Detergent / Permeabilization Agent: Creates pores in cell membranes to allow antibody penetration. | Typically used at 0.1-0.5% in blocking or wash buffers [32] [26]. |

| Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking Agent: Used to block non-specific binding sites to reduce background. | Used at 1-5% in incubation buffers [32] [26]. |

| Normal Serum | Blocking Agent: Serum from the host species of the secondary antibody further reduces background. | Commonly used at 1-10% in blocking buffers [32] [34] [33]. |

| Tween 20 | Detergent / Wash Buffer Additive: A mild detergent used in wash buffers to reduce non-specific binding. | Typically used at 0.1% in PBS (PBS-T) for washing steps [33]. |

Experimental Workflow for Embryo Storage & Processing

The following diagram outlines the key steps for the short-term storage, processing, and staining of fixed embryos for whole-mount immunofluorescence.

Cryopreservation is a fundamental technique that uses low temperatures to preserve the structural integrity of living cells and tissues, effectively suspending their metabolic activity for long-term storage. For researchers working with fixed embryos for whole mount immunofluorescence, a robust cryopreservation strategy is essential for maintaining antigen accessibility, cellular morphology, and experimental reproducibility over months to years. This process involves carefully controlled cooling to very low temperatures (typically -80°C to -196°C) to dramatically reduce all biological and chemical reactions. The success of long-term storage depends on three critical factors: the composition of the freezing media, the cooling and warming rates employed, and the optimization of storage temperatures. By implementing proper cryopreservation protocols, researchers can preserve valuable embryonic specimens for future immunofluorescence analyses while minimizing changes to cellular genetics or morphology that might occur with continuous passaging or inadequate storage conditions.

Fundamental Principles of Cryopreservation

The Role of Cryoprotective Agents (CPAs)

Cryoprotective agents are essential components of any freezing media, functioning to protect cells from damage during the freezing process. The primary mechanism of protection involves preventing the formation of intracellular ice crystals that can pierce cell membranes and cause structural damage [35]. CPAs work by replacing water within cells and creating a protective environment that minimizes ice crystal formation. The permeability of embryos to different CPAs varies significantly, which directly influences how these compounds are taken up by cells and ultimately determines their protective efficacy [36]. Commonly used permeable CPAs include:

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): A highly permeable CPA that readily crosses cell membranes but exhibits higher toxicity, particularly at suprazero temperatures [37].

- Ethylene glycol (EG): Demonstrates lower CPA toxicity and often provides higher post-cryopreservation survival compared to DMSO at the same concentration [37].

- Propylene glycol (PG): Another permeable CPA option with intermediate properties.

Non-permeable CPAs include sugars such as sucrose, sorbitol, and trehalose, which function primarily by creating an osmotic gradient that facilitates dehydration before freezing [37]. Research indicates that combinations of permeable and non-permeable CPAs often provide superior post-cryopreservation survival compared to permeable CPAs alone at the same total osmolarity, as they reduce overall CPA toxicity while maintaining protection against lethal ice formation [37].

Temperature Optimization and Rate Changes

The temperatures and rate changes employed during cryopreservation are critical variables that significantly impact specimen survival. The cooling rate determines how water exits cells and ice forms, while the warming rate affects the reversal of these processes. For most cell types, a controlled cooling rate of approximately -1°C/minute is ideal for freezing [38]. However, the warming rate is at least as important, if not more important, in determining ultimate survival of cryopreserved specimens [36]. Rapid warming helps reduce exposure time to the solutes present in freezing media and minimizes damage from ice recrystallization [38].

Storage temperature selection directly affects long-term viability. For optimal long-term performance, storage at liquid nitrogen temperatures (-135°C to -196°C) is recommended [39] [38]. While short-term storage (<1 month) at -80°C may be acceptable, cells kept at this temperature will degrade over time due to transient warming events during freezer access and thermal cycling [38]. This decline in viability is cell-type dependent but inevitable at these higher storage temperatures.

Figure 1: Cryopreservation Workflow for Embryo Storage. This diagram outlines the key stages in the long-term cryopreservation process, from initial preparation through to viability assessment after thawing.

Cryopreservation Protocols for Fixed Embryos

Pre-processing and Fixation Considerations

Proper tissue preparation before cryopreservation is crucial for maintaining specimen quality, particularly for fixed embryos intended for whole mount immunofluorescence. The quality of your starting tissue fundamentally impacts staining results, so always use the freshest tissue possible or ensure appropriate storage conditions for downstream applications [40]. Fixation should be performed with freshly prepared or freshly thawed 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to achieve optimal results. For consistent fixation, incubate embryos in fixative overnight at 4°C on a gentle shaker to ensure homogeneous reaction across the tissue [40].

For embryos destined for frozen tissue sections, post-fixation processing includes incubation in 30% sucrose solution, which acts as a cryoprotectant. This step should be conducted for at least overnight in the refrigerator before embedding in a cryomatrix [40]. It's important to note that tissue should not be stored in sucrose for longer than one week to prevent bacterial or fungal growth and degradation of proteins of interest [40]. For long-term storage of fixed tissue before sectioning, frozen tissue blocks or cryosections should be stored at -20°C or -80°C.

Vitrification Protocol for Embryos

Vitrification represents an advanced cryopreservation method that utilizes high concentrations of CPAs and ultra-rapid cooling to transform cellular solutions into a glassy, non-crystalline state. This technique has proven highly effective for embryo cryopreservation, with studies demonstrating that embryos resulting from vitrified eggs have similar developmental competence as those from fresh eggs when optimized protocols are used [41].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Vitrification Protocol Variables

| Protocol Variable | Short Protocol (45 sec) | Long Protocol (90 sec) | Impact on Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| VS Exposure Time | 45 seconds | 90 seconds | Affects CPA penetration and potential toxicity |

| Blastocyst Formation | 26.5% | 50.8% | Significantly higher with longer exposure [41] |

| Survival Rate | No significant difference | No significant difference | Both protocols showed similar survival |

| Clinical Pregnancy | No significant difference | No significant difference | Comparable outcomes after transfer |

| Recommended Use | Suboptimal for blastocyst development | Preferred for improved blastocyst formation | Long protocol provides better developmental outcomes |

A standardized vitrification protocol for embryos involves the following key steps:

Equilibration: Transfer embryos through a series of equilibration solutions containing increasing concentrations of CPAs. A typical approach involves:

- Basic solution for 1 minute

- Equilibration solution (7.5% ethylene glycol + 7.5% DMSO) for 2 minutes

- Second equilibration solution for another 2 minutes

- Fresh equilibration solution for 5 minutes [41]

Vitrification Solution Exposure: Transfer embryos to vitrification solution (typically 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5M sucrose) in three drops of 10-20 seconds each [41]. Research indicates that longer exposure times (90 seconds total) significantly improve blastocyst formation rates compared to shorter exposures (45 seconds) without compromising survival, fertilization, or pregnancy rates [41].

Loading and Cooling: Load embryos onto specialized vitrification devices (e.g., cryotop, cryomesh) and immediately plunge into liquid nitrogen. The "CPA solution free" method, which involves wicking away excess solution before vitrification, significantly improves cooling and warming rates and enhances post-cryopreservation survival [37].

Slow Freezing Protocol

While vitrification has gained popularity for many applications, controlled slow freezing remains a valuable approach, particularly for certain embryo types. The slow freezing method involves:

CPA Exposure: Embryos are exposed to lower concentrations of CPAs compared to vitrification, typically through a step-wise addition to minimize osmotic shock.

Controlled Cooling: Using a programmable freezer or freezing container, embryos are cooled at a controlled rate of approximately -1°C/minute to between -30°C and -80°C before transfer to liquid nitrogen for storage [38] [35].

Seeding: During the cooling process, the solution is intentionally seeded to initiate extracellular ice crystal formation at a specific temperature, which helps control dehydration.

This method allows for gradual dehydration of cells as extracellular ice forms, minimizing intracellular ice crystal formation. However, comparisons between slow freezing and vitrification generally show superior survival rates with vitrification for most embryo types [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Embryo Cryopreservation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Permeable CPAs | Ethylene Glycol (EG), Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), Propylene Glycol (PG) | Penetrate cell membranes to protect against intracellular ice formation; EG shows lower toxicity [37] |

| Non-permeable CPAs | Sucrose, Sorbitol, Trehalose | Create osmotic gradient for controlled dehydration; reduce required concentration of permeable CPAs [37] |

| Commercial Media | CryoStor CS10, mFreSR, STEMdiff | Pre-formulated, serum-free options providing consistent performance; some are GMP-manufactured for regulatory compliance [38] |

| Permeabilization Agents | D-limonene and heptane mixture | Remove waxy layers for improved CPA penetration; critical for some embryo types [37] |

| Cryoprotective Additives | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Provide additional membrane protection in home-made freezing media; FBS raises concerns about lot-to-lot variability [38] |

Troubleshooting Common Cryopreservation Issues

Low Post-Thaw Survival Rates

Inadequate survival rates following thawing indicate issues with one or more aspects of the cryopreservation process:

Problem: Ice crystal formation during freezing or thawing.

Problem: CPA toxicity evidenced by damaged cellular structures.

- Solution: Optimize CPA exposure times and concentrations. Consider using less toxic CPAs like ethylene glycol instead of DMSO. Implement combination strategies using both permeable and non-permeable CPAs to reduce overall toxic load [37].

Problem: Incomplete permeabilization preventing CPA entry.

- Solution: For challenging specimens, implement permeabilization steps such as brief treatment with D-limonene and heptane mixtures to remove waxy layers [37].

Poor Morphology or Antigen Preservation in Fixed Specimens

When cryopreserved fixed embryos show degraded morphology or poor antigen recognition in immunofluorescence:

Problem: Inadequate or inconsistent fixation before cryopreservation.

- Solution: Use freshly prepared 4% PFA and ensure consistent fixation conditions with gentle agitation. Standardize fixation times across experiments [40].

Problem: Ice crystal damage during freezing disrupting cellular architecture.

- Solution: Implement proper cryoprotection with sucrose infiltration (e.g., 30% sucrose overnight) before freezing for specimens intended for sectioning [40].

Problem: Antigen masking during the freezing process.

- Solution: Incorporate antigen retrieval methods after thawing, such as heating in acidic (sodium citrate, pH 6) or basic buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 9) for 15-20 minutes [40].

Contamination and Storage Failures

Maintaining specimen integrity throughout the storage period is essential for long-term projects:

Problem: Microbial contamination in stored specimens.

- Solution: Include antimicrobial agents like sodium azide in PBS for temporary storage of fixed specimens before freezing. Avoid long-term storage in sucrose solutions which promote microbial growth [40].

Problem: Temperature fluctuations during storage compromising viability.

- Solution: Use temperature monitoring systems with alarms for storage tanks. Ensure proper maintenance of liquid nitrogen levels in storage dewars. For critical samples, consider duplicate storage in separate tanks [39].

Problem: Sample identification errors or mix-ups.

- Solution: Implement comprehensive labeling systems using alcohol- and liquid nitrogen-resistant markers or printed cryo labels. Maintain detailed inventory records of banked specimens [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How long can embryos remain in cryostorage without significant degradation? Embryos can theoretically remain viable indefinitely when stored at proper liquid nitrogen temperatures (-135°C to -196°C), as all metabolic activity is effectively suspended at these temperatures [39]. However, practical storage limits may be influenced by factors such as storage tank maintenance, potential for temperature fluctuations, and legal constraints on storage duration which can extend up to 55 years in some jurisdictions with proper consent [42].

Q2: What concentration of cryoprotectant should I use for embryo cryopreservation? Optimal CPA concentration depends on the specific embryo type and cryopreservation method. For vitrification, final concentrations of 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5M sucrose have been used successfully [41]. However, research indicates that combinations of 39% EG with 9% sorbitol can provide excellent protection with reduced toxicity [37]. Empirical testing is recommended to determine the ideal concentration for specific embryo types.

Q3: Why do some embryos survive cryopreservation while others do not, even from the same batch? Embryo viability post-cryopreservation depends on multiple factors including developmental stage, morphological quality, and genetic background [39] [37]. At the time of freezing, embryos are evaluated for potential viability based on morphology and structural features. Even with careful selection, some embryos may not survive the freezing process due to subtle differences in membrane composition, metabolic state, or structural integrity [39].

Q4: What is the recommended cooling rate for embryo cryopreservation? For slow freezing methods, a controlled rate of approximately -1°C/minute is generally ideal for most cell types [38]. However, for vitrification, ultra-rapid cooling is essential to achieve the glassy state without ice crystal formation. This requires specialized devices or direct plunging into liquid nitrogen after proper CPA equilibration [41] [37].

Q5: How can I improve antibody penetration in cryopreserved fixed embryos for whole mount immunofluorescence? For whole mount immunostaining of cryopreserved embryos, several strategies can enhance antibody penetration: (1) Increase detergent concentration (e.g., 1% Triton-X or Tween-20) during permeabilization; (2) Implement antigen retrieval using heated buffers (70°C for 15 minutes) in Tris-HCl pH 9 or sodium citrate pH 6; (3) For challenging specimens, include a 20-minute treatment with ice-cold acetone at -20°C before antibody incubation [40].

Q6: What quality control measures should I implement for long-term cryostorage? Robust quality control for cryostorage includes: (1) Daily monitoring of storage tank temperatures with alarm systems that alert staff if temperatures rise even a single degree above requirements [39]; (2) Proper labeling systems using liquid nitrogen-resistant markers; (3) Detailed inventory management tracking all samples entering and leaving storage; (4) Regular tank maintenance and backup systems for critical storage units [39] [38].

Implementing optimized long-term cryopreservation strategies for fixed embryos requires careful attention to multiple interdependent factors: the composition and formulation of freezing media, controlled manipulation of temperature rates during cooling and warming, and maintenance of stable ultra-low storage temperatures. The protocols and troubleshooting guides presented here provide a foundation for researchers to preserve embryonic specimens effectively for whole mount immunofluorescence and other downstream applications. By understanding the fundamental principles of cryobiology and applying systematic approaches to protocol optimization and problem-solving, scientists can ensure the long-term viability and experimental utility of valuable embryonic research specimens for months to years, thereby enhancing research reproducibility and enabling longitudinal studies that would otherwise be impossible.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most critical factor for successful long-term storage of fixed embryos? The quality of the initial fixation is paramount. Always use fresh, high-quality fixative (e.g., freshly prepared or thawed 4% PFA) and ensure the fixation time is appropriate for your embryo's size and stage. Poor fixation cannot be reversed and will compromise all downstream applications, including long-term storage [43].

2. I need to pause my experiment after fixation. What is the best way to store my zebrafish embryos? For zebrafish embryos, you can store them in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C for up to two weeks. The sodium azide prevents bacterial and fungal growth. For longer storage, consider proceeding with cryoprotection and freezing. [43]

3. Can I store my fixed mouse embryos in the sucrose solution used for cryoprotection? While embryos must be incubated in sucrose (e.g., 30%) for cryoprotection, you should not store them in this solution for extended periods. Do not exceed one week of storage in sucrose at 4°C, as this can promote microbial growth and degradation of your proteins of interest. For long-term storage, freeze the prepared tissue blocks or cryosections at -20°C or -80°C. [43]

4. My antibody signal is weak after storing my chick embryos. What could have happened? Weak signal can result from epitope degradation during storage. Ensure that the embryos were thoroughly washed after fixation to remove all PFA residues before storage. Also, verify that your storage temperature is consistent and that the embryos were not subjected to multiple freeze-thaw cycles if they were frozen. For some antigens, the fixation method itself (e.g., PFA vs. TCA) can impact accessibility [5].

5. Is it possible to store embryos after a whole-mount nuclear stain for later imaging? Yes, one advantage of whole-mount nuclear staining techniques is that they have minimal impact on the specimen. Embryos stained with dyes like DAPI and imaged in an aqueous buffer can subsequently be processed for paraffin or frozen sectioning and histological staining, making them available for multiple assays. [44]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Tissue Morphology After Storage

| Possible Cause | Solution | Applicable Model Organisms |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or uneven fixation | Ensure fixation is performed on a gentle shaker for homogeneity. Always use fresh PFA. | Zebrafish, Mouse, Chick [43] |

| Microbial contamination during storage | Add 0.1% sodium azide to aqueous storage buffers (e.g., PBS). Avoid long-term storage in sucrose solutions. | Zebrafish, Mouse, Chick [43] |

| Improper cryoprotection before freezing | Infiltrate tissue thoroughly with 30% sucrose until the tissue sinks before embedding and freezing. | Zebrafish, Mouse, Chick [43] |

| Freezer burn or dehydration | Ensure tissue blocks or samples are well-sealed in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound or storage containers to prevent air exposure. | Zebrafish, Mouse, Chick |

Problem: Loss of Antigenicity (Weak or No Antibody Signal) After Storage

| Possible Cause | Solution | Applicable Model Organisms |

|---|---|---|

| Over-fixation | Standardize fixation time and temperature. For zebrafish, test lighter fixation (e.g., 1% PFA) if deyolking is required [45]. For chicken embryos, 20 mins-1 hour at room temperature may be sufficient [46]. | All, but specific timing varies [43] [46] [45] |

| Protein degradation during storage | For fixed samples stored in PBS at 4°C, do not exceed 2 weeks. For long-term storage, use -20°C or -80°C. | Zebrafish, Mouse, Chick [43] |

| Epitope masking by cross-linking | If using PFA, consider optimizing an antigen retrieval step before immunostaining. For whole-mount samples, this can be done by heating in sodium citrate (pH 6) or Tris-HCl (pH 9) buffer [43]. | All |

| Incompatible fixative for the target epitope | If PFA gives poor results, validate an alternative fixative like methanol or Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA). TCA can be particularly effective for some cytoskeletal and membrane proteins [5] [15]. | All, studied in Chick [5] |

Embryo Storage Parameters Table

The following table summarizes key storage parameters for fixed embryos of different model organisms based on experimental goals.

| Organism | Fixation Protocol (for Storage) | Short-Term Storage (Post-Fixation) | Long-Term Storage (Processed Samples) | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | 4% PFA, overnight at 4°C on gentle shaker [43]. For deyolking protocols: 1% PFA, 2h at RT or overnight at 4°C [45]. | PBS + 0.1% Sodium Azide at 4°C for up to 2 weeks [43]. | Cryosections or tissue blocks at -20°C or -80°C [43]. De-yolked embryos can be stored in methanol at -20°C [45]. | Permeabilization is critical. For whole-mount, detergent concentration may be increased to 1% [43]. The yolk can hinder imaging and storage; deyolking is an option [45]. |

| Chick | 4% PFA for 20 minutes to 1 hour at room temperature [46]. | In PBS or PBT (PBS with Triton) at 4°C. | Similar to mouse and zebrafish; embedded blocks or sections at -80°C. | For whole-mount, embryos older than ~6 days are too large for effective reagent penetration and should be dissected [15]. |

| Mouse | 4% PFA, time varies with embryo size (e.g., 1-2 hours for E9.5 to overnight for E15.5). | PBS at 4°C. | Cryosections or tissue blocks at -20°C or -80°C. | Nuclear stain penetration in whole mounts is effective through E15.5; skin maturation thereafter reduces permeability [44]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Fixation to Storage

The diagram below outlines the core decision-making process for handling and storing fixed embryos to ensure sample quality for future immunofluorescence analysis.

Fixation Method Decision Guide

Choosing the correct fixative is a critical first step that influences all subsequent storage and staining outcomes. The following diagram helps guide this decision based on the target protein's localization.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents for the fixation and storage of embryos, along with their primary functions.

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue architecture by creating stable bonds between proteins. | Use freshly prepared or freshly thawed aliquots. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Standard concentration is 4% [43]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Precipitating fixative that denatures and aggregates proteins via acid-induced coagulation. | Can provide better access to some epitopes hidden by PFA cross-linking, especially for cytoskeletal proteins [5]. |

| Sucrose | Cryoprotectant that displaces water in tissues to prevent ice crystal formation during freezing. | Incubate until tissue sinks (often overnight). Do not store tissues in sucrose for >1 week to prevent degradation [43]. |

| Sodium Azide | Antimicrobial agent that inhibits bacterial and fungal growth in aqueous storage buffers. | Use at 0.1% concentration in PBS for short-term storage of fixed samples at 4°C [43]. Handle with care as it is toxic. |

| Triton X-100 or Tween-20 | Detergent used for permeabilization of cell membranes to allow antibody penetration. | For thick whole-mount samples like retina, concentration may be increased to 1% for better penetration [43]. |

| Donkey Serum or BSA | Component of blocking buffer to reduce non-specific antibody binding. | Used at 1-10% in PBS with detergent. Serum should match the species in which the secondary antibody was raised [15] [46]. |

For researchers storing fixed embryos for whole mount immunofluorescence, implementing rigorous quality control (QC) checkpoints is crucial for experimental success. A quality control plan provides a documented framework of specific procedures and standards to ensure consistent and reliable results [47]. Within this framework, visual inspection and pre-staining assessments serve as fundamental, non-destructive testing methods to identify issues before they compromise your data [48] [49]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you maintain the integrity of your fixed embryo samples from storage through to staining.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Pre-Staining Visual Inspection of Fixed Embryos

User Issue: "How do I know if my fixed embryos are still healthy for staining after storage?"

A systematic visual inspection of fixed embryos before proceeding to staining is the first critical defense against experimental failure.

Inspection Procedure:

- Environment Setup: Use a dissection microscope in a clean, well-lit area. Ensure proper lighting (500-1000 lux is often recommended for visual tasks) and a dark background to enhance contrast and visibility of the embryos [49] [50].

- Direct Visual Inspection: Examine the embryos with the naked eye or using magnifying tools for any obvious signs of degradation [48].

- Documentation: Record the appearance of the embryos, including any noted issues, using a standardized checklist to maintain consistency and track sample quality over time [47] [50].

Common Defects & Corrective Actions:

Observed Issue Potential Cause Corrective Action Embryos appear shrunken or crumpled Over-fixation or improper storage solution [51]. For future samples, reduce fixation time. For current samples, proceed with caution as antigenicity may be reduced. Embryos are discolored (brown/yellow) Oxidation or bacterial/fungal contamination during storage. Discard the sample. Ensure fixed embryos are stored in adequate PBS at 4°C and that equipment is sterile [52]. Embryos are fragmented Physical damage during dissection or handling post-fixation. Use gentle pipetting with wide-bore tips. Fixed embryos can be sticky; using PBT (PBS with Triton X-100) during washes can help reduce sticking [53]. Precipitates or crystals on surface Salt precipitation from evaporation of storage buffer. Ensure samples are fully submerged in PBS during storage. Rinse embryos thoroughly with fresh PBS before proceeding [51].

Troubleshooting Weak or No Staining

User Issue: "I followed the protocol, but my signal is weak or non-existent."

This is a common challenge often rooted in sample preparation, antibody handling, or staining conditions.

- Systematic Troubleshooting Table:

Potential Cause Investigation & Solution Inadequate Permeabilization The antibody cannot access intracellular targets. Solution: Increase incubation time with permeabilization agent (e.g., ice-cold methanol or Triton X-100) or increase the detergent concentration in the permeabilization buffer [53] [51]. Antigen Masking from Fixation Over-fixation can cross-link and hide epitopes. Solution: Reduce fixation time or perform an antigen retrieval step. For example, incubate samples in a pre-heated antigen retrieval buffer (e.g., 100 mM Tris, 5% urea, pH 9.5) at 95°C for 10 minutes [51]. Inactive Antibodies Antibodies may have degraded due to improper storage or repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Solution: Aliquot antibodies and store at -20°C or below. Use a new batch or run a positive control to verify antibody activity [51] [54]. Low Antigen Abundance The target protein is not present or is in very low amounts. Solution: Increase sensitivity by increasing primary antibody concentration or incubation time (e.g., overnight at 4°C). Consider using signal amplification systems like tyramide (TSA) [51] [54]. Improper Blocking Non-specific sites are not effectively blocked, leading to high background that obscures signal. Solution: Increase blocking time (up to 1 hour) or change the blocking agent. Common blockers include 1-5% BSA or 10% normal serum from the host species of the secondary antibody [51] [54].

Addressing High Background and Non-Specific Staining

User Issue: "My staining has so much background noise that I can't distinguish the specific signal."

High background often stems from non-specific interactions between the antibodies and the sample.

- Systematic Troubleshooting Table:

Potential Cause Investigation & Solution Insufficient Washing Unbound antibodies or fixative remains in the sample. Solution: Wash samples at least 3 times with PBT (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100) between steps, with gentle agitation for 1 hour per wash [53] [54]. Ineffective Blocking Non-specific binding sites are not saturated. Solution: Extend the blocking incubation period and consider using a different blocking agent, such as a combination of normal serum and BSA [51] [54]. Antibody Concentration Too High The antibody is binding non-specifically. Solution: Titrate the primary and secondary antibodies to find the optimal dilution. Incubating for longer periods with a more dilute antibody can sometimes improve the signal-to-noise ratio [54]. Secondary Antibody Cross-Reactivity The secondary antibody binds non-specifically to the sample. Solution: Always run a secondary-only control (no primary antibody). Use secondary antibodies that are pre-adsorbed against the serum proteins of your sample species [51] [54]. Autofluorescence from Aldehyde Fixatives Residual aldehyde groups can cause background glow. Solution: After fixation and washing, treat samples with a fresh 1% sodium borohydride (NaBH4) solution in PBS to reduce these groups [51].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for successful whole mount immunofluorescence and its associated quality control. Proper preparation and understanding of their function are key.

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | An isotonic, pH-balanced salt solution used for washing tissues and as a base for other solutions. It maintains osmotic balance to prevent damage to the embryos [53] [52]. |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | A cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue architecture and immobilizes antigens by creating chemical bonds between proteins. Fixation time and temperature should be optimized for your specific antigen [53] [52]. |

| PBT (PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100) | A standard wash and dilution buffer. Triton X-100 is a non-ionic detergent that permeabilizes cell membranes, allowing antibodies to enter, and helps reduce stickiness of fixed embryos [53] [52]. |

| Blocking Buffer | A solution containing a protein or serum (e.g., 1-5% BSA or 10% normal serum) used to occupy non-specific binding sites on the tissue, thereby reducing background staining [53] [52] [54]. |