Beyond Animal Models: Validating Organoid Systems for Predictive Human Development and Disease Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating organoid models against in vivo development.

Beyond Animal Models: Validating Organoid Systems for Predictive Human Development and Disease Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating organoid models against in vivo development. It explores the foundational principles establishing organoids as physiologically relevant systems, details advanced methodological applications from disease modeling to drug screening, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges including reproducibility and maturation, and presents rigorous comparative analyses with traditional models. By synthesizing current evidence and standardization initiatives, this resource aims to guide the confident adoption of organoid technology to enhance the translational predictive power of preclinical research.

Establishing the Basis: Why Organoids Offer a Physiologically Relevant Platform

In the evolving landscape of biological research, organoids have emerged as a transformative technology that bridges the gap between traditional two-dimensional cell cultures and complex in vivo models. These three-dimensional (3D) multicellular, microtissues are derived from stem cells and are designed to closely mimic the complex structure and functionality of human organs like the lung, liver, or brain [1]. Organoids represent a paradigm shift in in vitro modeling, affording researchers a much more physiologically relevant system than traditional two-dimensional cell cultures [2]. The defining characteristics of organoids include their 3D architecture, presence of multiple cell types, representation of the complexity and organization of native tissue, and resemblance of at least some aspects of tissue functionality [1].

The significance of organoid technology is reflected in its growing market impact. According to a report by The Insight Partners, the organoid market is expected to reach $15.01 billion in 2031, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 22.1% from 2023's $3.03 billion [3]. This growth is fueled by increasing recognition of organoids' potential in disease modeling, drug discovery, and personalized medicine. The passing of the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 has further empowered researchers to use innovative non-animal methods, including organoids, for drug testing, potentially transforming the speed and success of bringing safe and effective treatments to market [3].

Stem Cells: The Foundation of Organoid Technology

Pluripotent Stem Cells and Their Differentiation Potential

Organoids can be generated from various stem cell sources, each offering distinct advantages for specific research applications. Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), possess the remarkable capacity to differentiate into any cell type present in an embryo or adult [4]. Takahashi and Yamanaka's groundbreaking 2006 discovery demonstrated that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into iPSCs through the ectopic expression of four transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC), opening new avenues for patient-specific disease modeling [4].

When PSCs are exposed to the right combination of growth factors and signals and provided with a 3D scaffold, they can differentiate into various cell types and self-organize into organoids. This approach has successfully generated organoids resembling multiple tissues, including brain, eyes, kidney, lung, stomach, intestine, inner ear, skin, thyroid, and liver [4]. The differentiation process is guided by specific growth factor combinations that mimic embryonic development. For example, intestinal organoid formation requires signals mediated by the Wnt (WNT) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) protein families to induce posterior endoderm patterning, hindgut, and intestinal morphogenesis [5]. Similarly, brain organoids require factors that promote neural induction and regional specification.

Adult Stem Cells and Tissue-Specific Organoids

In contrast to pluripotent stem cells, adult stem cells (ASCs) are tissue-resident, multipotent cells responsible for maintaining homeostasis in specific organs throughout postnatal life [4]. These cells can only differentiate into cell types from their organ of origin, making them ideal for generating tissue-specific organoids. ASCs reside in specialized microenvironments known as stem cell niches, which regulate their cellular fate through secreted molecules, cell-cell interactions, and physical contact with the extracellular matrix [4].

The first protocol for generating organoids from ASCs was developed using intestinal tissue, where the molecular mechanisms regulating intestinal stem cell turnover are well understood [5]. The Wnt signaling pathway emerged as a key driver of epithelial ASC growth, inducing the secretion of R-spondin-1 protein (RSPO1), the ligand of the leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) expressed in most ASCs [5]. This breakthrough enabled the generation of patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from various tissues, including pancreas, prostate, esophagus, ovary, liver, kidney, and breast [5]. Organoids generated from ASCs or adult tissue fragments more closely resemble the homeostatic and regenerative capacity of the tissue of origin than PSC-derived organoids, making them valuable models for studying diseases such as cancer or neurodegenerative disorders [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Stem Cell Sources for Organoid Generation

| Characteristic | Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) | Tissue-specific stem cells |

| Differentiation Potential | Can differentiate into all cell types from three germ layers | Limited to cell types of their organ of origin |

| Resemblance to Native Tissue | More closely resembles fetal tissue stage [4] | Closely resembles homeostatic and regenerative adult tissue [4] |

| Genetic Stability | Lower genetic stability [4] | Higher genetic stability [4] |

| Primary Applications | Developmental studies, disease modeling, organogenesis [4] | Disease modeling, personalized medicine, cancer research [6] |

| Examples | Brain, kidney, lung organoids [4] | Intestinal, pancreatic, prostate organoids [5] |

Validating Organoid Models Against In Vivo Physiology

Methodological Framework for Physiological Validation

A critical challenge in organoid research is establishing the physiological fidelity of these in vitro models against their in vivo counterparts. A systematic framework for validation utilizes massively parallel single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to compare cell types and states found in vivo with those of in vitro organoid models [7]. This approach enables researchers to identify discrepancies and implement molecular interventions to rationally improve physiological fidelity.

In a landmark study, researchers used scRNA-seq to compare Paneth cells—specialized epithelial cells of the small intestine that support the stem cell niche and produce antimicrobial peptides—in conventional intestinal organoids against their in vivo counterparts [7]. This comparison revealed fundamental gene expression differences in lineage-defining genes, enabling the researchers to nominate and test molecular interventions to enhance Paneth cell physiology in organoids. The resulting improved model demonstrated enhanced antimicrobial activity and niche support function, key characteristics of in vivo Paneth cells [7].

Functional and Structural Validation Approaches

Beyond transcriptomic profiling, comprehensive validation of organoid models requires multidisciplinary approaches including histopathological analysis, functional assays, and drug response testing. Histological comparison involves examining organoid sections through hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry for tissue-specific markers to assess architectural resemblance to native tissue [8]. For example, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tumor organoids show strong correlation of histopathological features with matched patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, with tumor cells in both systems expressing cytokeratin 19, a marker of pancreatic epithelial differentiation [8].

Functional validation includes assessing organoid capabilities that mirror in vivo tissue functions, such as nutrient absorption in intestinal organoids, metabolic activity in hepatic organoids, or synaptic connectivity in brain organoids. For specialized cells like Paneth cells, functional validation involves testing antimicrobial activity through bacterial killing assays and evaluating niche support capability through stem cell maintenance assays [7]. Drug response profiling represents another critical validation parameter, particularly for cancer organoids. Studies have demonstrated a specific relationship between area under the curve values of organoid drug dose response and in vivo tumor growth, irrespective of the drug treatment [8].

Table 2: Multi-Modal Validation of Organoid Physiological Fidelity

| Validation Method | Key Parameters Assessed | Experimental Techniques | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic Profiling | Gene expression patterns, cell type representation | Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), bulk RNA-seq | Identification of gene expression differences in Paneth cells between in vivo and organoid models [7] |

| Histopathological Analysis | Tissue architecture, cellular organization, marker expression | H&E staining, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence | PDAC organoids maintain glandular structures and cytokeratin 19 expression seen in PDX models [8] |

| Functional Assays | Cell-specific functions, metabolic activity, secretory profile | Antimicrobial assays, nutrient absorption tests, metabolite profiling | Enhanced Paneth cells in improved organoid models show increased antimicrobial activity [7] |

| Drug Response Testing | Therapeutic sensitivity, resistance mechanisms, predictive value | Dose-response curves, high-throughput screening | Concordance between PXO and PDX responses to therapeutic drugs observed in pancreatic cancer models [8] |

| Glycomic Analysis | Glycosylation patterns, post-translational modifications | Mass spectrometry, lectin arrays | PXO cultures retain complex glycosylation changes observed in PDX models [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Organoid Generation and Validation

Standardized Workflow for Organoid Culture

The general workflow for organoid culturing and analysis involves multiple standardized steps that ensure reproducibility and physiological relevance. The process begins with 2D preculture, where organoids are derived from either primary cells or induced pluripotent stem cells [1]. The cells are then premixed with an extracellular matrix (ECM) substitute, most commonly Matrigel, and droplets are placed into multi-well plates at room temperature. The plates are transferred to an incubator to form a solid droplet dome, after which media is added for seven or more days to promote cell growth and differentiation into specific tissues [1].

Organoid culture is a long process that may include several steps with different media formulations. During this process, cell health needs to be monitored regularly through imaging to ensure proper development [1]. Before experiments are conducted, organoids require comprehensive characterization to verify appropriate tissue structure and differentiation. High-content imaging allows for monitoring and visualizing organoid growth and differentiation, 3D reconstruction of structures, complex analysis of organoid architecture, cell morphology and viability, and expression of different cell markers [1]. Confocal imaging and 3D analysis of organoids enable visualization and quantitation of the organoids and their constituent cells, with characterization of multiple quantitative descriptors used for studying disease phenotypes and compound effects [1].

Key Signaling Pathways and Growth Factors

Successful organoid culture depends on precise activation or inhibition of key signaling pathways through specific growth factors and inhibitors in the culture medium. The Wnt signaling pathway is fundamental for maintaining stemness and promoting proliferation in many organoid types. Activation is typically achieved through recombinant WNT3A or small molecule inhibitors of GSK3, combined with R-spondin 1 (RSPO1), which enhances Wnt signaling by binding to LGR5 receptors on stem cells [5] [2]. Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling must often be inhibited to prevent differentiation, typically using Noggin, which binds to various BMPs including BMP4 and BMP7, limiting their inhibitory activity on stem cell maintenance [2].

The EGF signaling pathway drives proliferation in many epithelial organoid systems. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) induces proliferative signaling cascades by binding to its receptor EGFR, supporting self-renewal and expansion of adult stem cell populations within organoids [2]. Research has shown that inhibiting EGFR signaling pharmacologically or through EGF depletion can significantly impair organoid proliferation and induce cellular quiescence and differentiation [2]. Additional factors like FGF10, FGF2, and Activin A are employed in specific organoid systems to direct differentiation toward particular lineages [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Organoid Research and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Organoid Culture | Validation Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Geltrex, synthetic hydrogels | Provides 3D structural support, mechanical cues, and biochemical signals for cell growth and organization | Batch-to-batch consistency, growth factor content, polymerization properties [1] |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | R-spondin 1, Noggin, EGF, FGF10, WNT3A | Activates specific signaling pathways for stem cell maintenance, proliferation, and differentiation | Purity, bioactivity, endotoxin levels, performance in organoid growth assays [2] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) | Modulates signaling pathways to enhance stem cell survival, growth, and direct differentiation | Specificity, potency, cytotoxicity, effects on target pathway activity [5] [8] |

| Basal Media Components | Advanced DMEM/F12, B27 supplement, N2 supplement, N-acetylcysteine | Provides nutritional support, hormones, and antioxidants for cell viability and function | Osmolality, pH stability, nutrient composition, support of long-term culture [8] |

| Dissociation Reagents | TrypLE, Accutase, collagenase, dispase | Enables organoid passaging and single-cell isolation for expansion and analysis | Enzymatic activity, cell viability post-dissociation, recovery efficiency [9] |

Current Limitations and Engineering Solutions

Addressing Structural and Functional Gaps

Despite their significant advantages, organoid models face several limitations that affect their physiological relevance and scalability. A primary constraint is the lack of vascularization, which limits organoid size due to inadequate nutrient and oxygen diffusion, leading to necrotic core development when organoids exceed approximately 500 micrometers in diameter [10] [3]. This absence of vascular networks also prevents recapitulation of crucial endothelial cell interactions and blood-tissue barriers present in vivo. Additionally, most organoid protocols are limited to epithelial cells, lacking the full complexity of the tumor microenvironment (TME) including immune cells, fibroblasts, and neural cells [5].

The fetal phenotype of many PSC-derived organoids presents another limitation, as they may not fully represent adult tissue characteristics or adult-onset diseases [3]. This is particularly relevant for disease modeling of conditions that manifest in mature tissues. Issues with reproducibility and standardization also persist, with variability in organoid shape, size, and cell type composition between batches and protocols [3]. A 2023 survey by Molecular Devices revealed that nearly 40% of scientists rely on complex human-relevant models like organoids, with reproducibility and batch-to-batch consistency identified as significant challenges [3].

Engineering Advances for Enhanced Physiological Relevance

Multiple engineering approaches are being developed to address these limitations and enhance organoid functionality. Vascularization strategies include co-culture with endothelial cells, incorporation of mesenchymal cells, and use of microfluidic devices to create perfusable networks [3] [10]. The chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model provides an alternative in vivo system for vascularizing organoids, where inoculation onto the highly vascularized, non-innervated CAM results in extensively vascularized xenografts that maintain histomorphological similarity to original patient tissue [9].

Organoid-on-chip systems combine organoids with microfluidic technology to create dynamic microenvironments that better recapitulate physiologic conditions [10]. These systems incorporate fluid flow, mechanical forces, and electrical stimulation to enhance cellular differentiation and tissue functionality. For example, fluid shear stress in renal organoid-on-chip systems leads to tissue maturation and morphogenesis, including formation of proximal tubule and glomerular compartments [10]. 3D bioprinting and biofabrication techniques enable precise control over organoid size, shape, and cellular composition, allowing creation of more complex and reproducible models [10]. These approaches facilitate the generation of multi-tissue interfaces and incorporation of stromal and immune cells to better mimic native tissue environments.

Organoid technology represents one of the most promising advancements in biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for studying human development, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions. The validation of organoid models against in vivo physiology remains crucial for realizing their full potential in basic and translational research. As systematic validation frameworks using single-cell genomics and other multi-omics approaches become more widespread, the physiological fidelity of organoid models continues to improve [7].

Future developments in organoid technology will likely focus on enhancing complexity through the incorporation of immune and vascular components, improving maturation to adult tissue phenotypes, and increasing scalability and reproducibility through automation and standardization [3] [10]. The integration of organoids with organ-on-chip technology and 3D bioprinting will further advance their applications in drug discovery and personalized medicine [3]. As these technologies evolve, organoids are poised to become indispensable tools for modeling human biology and disease, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective therapies.

Organoid technology represents a transformative advancement in biomedical research, offering in vitro models that closely mimic human physiology. For researchers and drug development professionals, the value of these three-dimensional structures lies in their core capabilities: faithfully preserving native tissue architecture, maintaining cellular diversity, and retaining patient-specific genetics. These advantages position organoids as superior tools for disease modeling, drug discovery, and personalized medicine approaches, effectively bridging the gap between traditional two-dimensional cell cultures and in vivo models [11] [12] [13]. This review systematically examines the experimental evidence validating organoid models against in vivo development and disease processes, providing critical insights for scientists selecting model systems for preclinical research.

Experimental Validation of Tissue Architecture Preservation

The capacity of organoids to recapitulate the complex three-dimensional architecture of native tissues represents a fundamental advantage over traditional two-dimensional cultures. This structural fidelity enables more physiologically relevant studies of cellular behavior, drug penetration, and tissue organization.

Histological and Morphological Evidence

Multiple studies have demonstrated that patient-derived organoids (PDOs) maintain histological features remarkably similar to their tissue of origin. Research on colorectal cancer organoids revealed conservation of characteristic pathological features, including the CK20+/CK7- immunophenotype found in most primary colorectal tumors [14]. Similarly, gliosarcoma organoids (GSOs) preserved the biphasic architecture of original tumors, containing both glial and mesenchymal elements characteristic of this rare glioblastoma variant [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment of Architectural Features in Cancer Organoids

| Organoid Type | Architectural Feature | Similarity to Primary Tissue | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer PDOs | Crypt-villus-like structures | High (96% mutation concordance) | Whole exome sequencing, immunohistochemistry [14] |

| Gliosarcoma Organoids (GSOs) | Biphasic glial and sarcomatous histology | High (key features preserved) | H&E staining, Masson's trichrome, reticulin stains [15] |

| Breast Cancer Organoids | Glandular organization | Moderate to high (variable by subtype) | Histological analysis, drug response profiling [11] |

| Lung Organoids | Airway and alveolar sac structures | High (mimics distinct lung regions) | Air-liquid interface culture, immunofluorescence [12] |

Protocol for Evaluating Architectural Integrity

Standardized methodologies have emerged to quantitatively assess architectural preservation in organoid models:

- Tissue Processing: For gliosarcoma organoids, researchers mechanically minced fresh tumor tissue into approximately 1mm³ pieces without enzymatic digestion to preserve native tissue integrity and cellular composition [15].

- Matrix Embedding: Samples are embedded in appropriate extracellular matrices (e.g., Matrigel, BME, or synthetic hydrogels) to support 3D growth [13].

- Histological Analysis: Organoids are fixed, sectioned, and stained using H&E, Masson's trichrome, or immunohistochemistry for cell-type-specific markers [15].

- Imaging and Quantification: High-resolution confocal microscopy followed by digital image analysis quantifies structural parameters including size, lumen formation, and spatial organization [15].

Conservation of Cellular Diversity

Organoids maintain the heterogeneous cellular composition of their source tissues, encompassing multiple cell types and states present in vivo. This diversity enables more comprehensive studies of cell-cell interactions, differentiation pathways, and disease mechanisms.

Single-Cell Transcriptomic Validation

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has provided unprecedented resolution for validating cellular heterogeneity in organoid models. Comparative analysis of gliosarcoma organoids (GSOs) versus glioblastoma organoids (GBOs) revealed distinct transcriptional programs: GSOs were enriched for fibroblast-like and oligodendrocyte progenitor-like states, while GBOs displayed astrocyte-like differentiation patterns, faithfully reflecting differences in their parent tumors [15].

Brain organoids similarly demonstrate remarkable cellular diversity, containing radial glial cells, intermediate progenitors, deep- and superficial-layer neurons, and in some cases, microglia and other glial cell types [16]. These systems recapitulate the ordered temporal generation of different neuronal subclasses observed in vivo, although the precise laminar organization of the mammalian cortex is not fully replicated [16].

Table 2: Cellular Composition Across Organoid Systems

| Organoid Type | Key Cell Types Identified | Validation Method | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Organoids | Radial glial cells, neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia | scRNA-seq, immunofluorescence, functional assays | Neurodevelopment, disease modeling, drug screening [16] |

| Airway Organoids | Basal cells, ciliated cells, goblet cells, neuroendocrine cells | ALI culture, immunofluorescence, electrophysiology | Respiratory disease modeling, host-pathogen interactions, toxicity testing [17] |

| Intestinal Organoids | Intestinal stem cells, enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells | Histology, mRNA sequencing, functional transport assays | Personalized medicine, regenerative medicine, infection biology [12] [13] |

| Tumor PDOs | Cancer stem cells, differentiated cancer cells, some stromal elements | Flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, drug response | Cancer biology, drug screening, personalized therapy [14] [13] |

Protocol for scRNA-seq of Organoids

The standard workflow for single-cell transcriptomic analysis of organoids includes:

- Organoid Dissociation: Enzymatic (e.g., trypsin, accutase) and/or mechanical dissociation of organoids into single-cell suspensions [15].

- Cell Viability Assessment: Using viability dyes or automated cell counters to ensure >80% viability.

- Single-Cell Partitioning: Loading cells into appropriate scRNA-seq platforms (10X Genomics, Drop-seq, etc.).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Following manufacturer protocols for cDNA synthesis, amplification, and library preparation.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Cell clustering, trajectory inference, and differential expression analysis using tools like Seurat, Scanpy, or Monocle [15].

Maintenance of Patient-Specific Genetics

Perhaps the most significant advantage of patient-derived organoids is their capacity to maintain the genetic landscape of the source tissue, enabling personalized disease modeling and drug response prediction.

Genomic and Transcriptomic Concordance

Comprehensive genomic analyses have demonstrated high concordance between PDOs and their corresponding patient tumors. Whole exome sequencing of colorectal cancer PDOs revealed approximately 96% similarity in mutations of key driver genes when compared to primary tumors [14]. Similarly, patient-derived tumor organoids (PDTOs) recapitulate the genetic diversity among patients, with quantitative mass-spectrometry-based proteome profiles resembling original tumors [11].

In oncology, this genetic fidelity translates to predictive power for treatment response. Studies report approximately 76% accuracy in organoids predicting patient response, with a sensitivity of 0.79 and specificity of 0.75, making PDOs suitable for guiding selection of effective therapeutic approaches personalized to each patient [14].

Table 3: Multi-Omics Validation of Patient-Specific Genetics in Organoids

| Analysis Type | Genetic Feature Preserved | Experimental Evidence | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Somatic mutations, copy number variations | 96% mutation concordance in CRC PDOs [14] | Disease modeling, driver gene identification |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression signatures, subtype classification | Conservation of CMS subtypes in CRC PDOs [14] | Drug response prediction, biomarker discovery |

| Proteomics | Protein expression patterns, signaling pathway activation | MS-based proteomics recapitulated tumor diversity [11] | Targeted therapy validation, signaling studies |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation patterns, chromatin accessibility | Maintenance of segmental DNA methylation during differentiation [11] | Aging studies, developmental biology |

Protocol for Genomic Validation of PDOs

Standardized protocols for genomic validation include:

- DNA/RNA Extraction: Using commercial kits to obtain high-quality nucleic acids from both source tissue and derived organoids.

- Sequencing Library Preparation: Following established protocols for whole genome, whole exome, or transcriptome sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Variant calling using established pipelines (GATK, VarScan) and comparison between tissue and organoid samples.

- Statistical Validation: Calculating concordance rates for mutations, copy number alterations, and gene expression profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful organoid culture requires carefully optimized reagents and materials. The table below details key solutions used in establishing and maintaining organoid cultures.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Organoid Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, BME, synthetic PEG hydrogels | Provides 3D scaffold for growth, mechanical cues | Batch variability, composition definition, clinical translation limitations [13] |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, Wnt3a, FGF10 | Directs differentiation, maintains stemness | Tissue-specific requirements, concentration optimization [13] [17] |

| Pathway Inhibitors/Agonists | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), CHIR99021 (Wnt activator) | Enhances viability, modulates signaling pathways | Concentration-dependent effects, temporal application critical [15] |

| Medium Formulations | Intestinal, cerebral, airway-specific media | Provides nutritional support, hormonal cues | Component stability, osmolarity, pH buffering [13] [17] |

| Dissociation Reagents | Trypsin, accutase, collagenase | Organoid passage, single-cell isolation | Duration optimization, viability impact [13] |

Signaling Pathways in Organoid Development and Culture

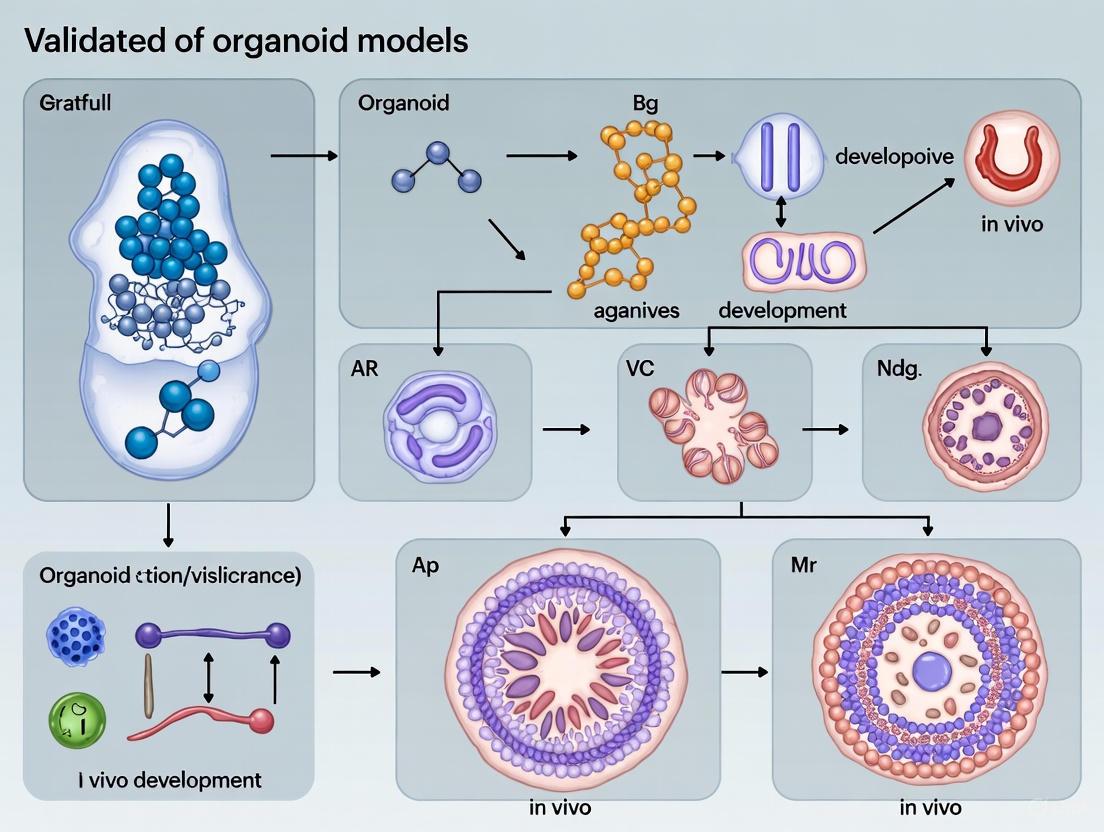

The successful establishment and maintenance of organoids depend on recapitulating key developmental signaling pathways. The diagram below illustrates the core pathways involved in organoid formation and maintenance, particularly for epithelial-derived organoids.

Key Signaling Pathways in Organoid Culture

The Wnt pathway is particularly crucial, with activation through R-spondin and Wnt3a supplementation supporting LGR5+ stem cell maintenance [13]. Interestingly, colorectal cancers with Wnt pathway mutations often grow without requiring exogenous Wnt activation, demonstrating how cancer organoids maintain the pathway alterations of their parent tumors [13]. Similarly, tumors with EGFR mutations can be cultured without EGF supplementation, reflecting their autonomous signaling [13].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Models

Organoids occupy a unique position in the spectrum of preclinical models, offering advantages over both traditional 2D cultures and in vivo models while having their own limitations.

Table 5: Model System Comparison for Drug Development Applications

| Model Characteristic | 2D Cell Cultures | Organoid Models | In Vivo Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Complexity | Low (monolayer) | High (3D structure) | High (native context) |

| Cellular Diversity | Limited (often single cell type) | Moderate to high (multiple cell types) | Complete (all native cells) |

| Genetic Fidelity | Low (genetic drift) | High (maintains patient genetics) | High (patient-derived xenografts) |

| Throughput | High | Moderate to high | Low |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

| Human Relevance | Variable | High (human-derived) | Limited (species differences) |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established | Growing | Established |

| Personalization Potential | Low | High | Moderate |

Organoid technology has firmly established itself as an indispensable tool for biomedical research, offering unprecedented preservation of tissue architecture, cellular diversity, and patient-specific genetics. The experimental data summarized in this review demonstrates that organoids provide a robust platform for modeling human development and disease, drug screening, and advancing personalized medicine. While challenges remain in standardizing protocols, incorporating complete tumor microenvironments, and improving reproducibility, the core advantages of organoid models position them as transformative tools that effectively bridge the gap between traditional in vitro systems and clinical research. For drug development professionals and researchers, organoids offer a physiologically relevant, human-derived model system that accelerates the translation of basic research findings into clinical applications.

Organoids, which are three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures derived from pluripotent or adult stem cells, have emerged as revolutionary tools in biomedical research for their ability to recapitulate the cellular heterogeneity, structure, and function of human organs [18]. These microstructures provide an invaluable platform for studying human biology, offering a more physiologically relevant system than traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures while retaining human genetic material that animal models lack [19]. The capacity of organoids to mimic in vivo conditions has garnered significant attention from regulatory bodies, including the FDA, which has recently approved organoids for drug testing to reduce reliance on animal models [2]. As the organoid market is expected to grow substantially from $3.03 billion in 2023 to $15.01 billion in 2031, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 22.1%, these models are increasingly positioned to bridge the translational gap between basic research and clinical application [3].

However, despite their promising features, organoids remain rudimentary and inherently artificial compared to intact living systems [20]. A significant translational gap persists between in vitro studies and in vivo applications, largely attributed to limitations in current organoid technologies [21]. The critical challenge lies in validating these models against in vivo development to ensure they faithfully replicate the complex biological processes of human organs. Without rigorous validation standards, organoid-based research and drug screening may yield misleading results, ultimately hindering their potential in disease modeling, drug discovery, and personalized medicine. This guide systematically compares organoid performance against traditional models, provides experimental validation protocols, and details essential reagent solutions to support researchers in bridging the in vitro-in vivo gap.

Comparative Analysis: Organoids Versus Traditional Research Models

Performance Metrics Across Model Systems

To objectively evaluate organoids as research tools, it is essential to compare their performance against traditional models—specifically 2D cell lines and patient-derived xenografts (PDX). The table below summarizes key quantitative and qualitative metrics across these systems, highlighting the relative advantages and limitations of each approach for biomedical research and drug development applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Research Models for Biomedical Applications

| Performance Metric | 2D Cell Lines | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low: Single cell type, lacks tissue structure and cell-cell interactions [19] | Moderate: Maintains 3D structure and some tumor microenvironment elements, but human stroma is replaced by mouse cells over time [19] | High: Retains 3D architecture, cellular heterogeneity, and genetic profile of original tissue [19] [18] |

| Success Rate/Establishment Time | High (Nearly 100%), days [19] | Low to moderate (Variable), months [19] | Moderate to high (Varies by organ system), weeks [19] |

| Cost Efficiency | Low cost [19] | High cost: Expensive to maintain and requires ethical oversight [19] | Moderate cost: More affordable than PDX but requires specialized matrices and factors [19] |

| Genetic Stability | Poor: Develops heterogeneity and drifts from original tissue over time [19] | Moderate: Loses primitive heterogeneity with passages; mouse stroma replaces human cells [19] | High: Faithfully maintains genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of original tissue across passages [19] [18] |

| Scalability/Throughput | High: Suitable for high-throughput drug screening [19] | Low: Time-consuming, low throughput [19] | Moderate to high: Improving toward high-throughput applications with automation [3] |

| Personalized Medicine Application | Limited: Represents only a subgroup of original tissue [19] | Moderate: Maintains some patient-specific characteristics but affected by mouse microenvironment [19] | High: Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) enable personalized drug testing and treatment prediction [22] [23] |

| Validation Status | Well-established with known limitations | Established but with recognized species-specific limitations | Emerging: Requires further validation against in vivo biology [20] |

Key Advantages of Organoid Models

The comparative analysis reveals several distinct advantages of organoid models that position them as transformative tools in biomedical research. Organoids retain the 3D structure of original tissues, faithfully summarizing the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity that is often lost in traditional 2D cell cultures [19]. This structural and functional fidelity enables more accurate modeling of human physiology and disease states. Furthermore, organoids provide a human-specific experimental platform that avoids the species-specific limitations inherent in animal models, thereby offering more clinically relevant insights for drug development and disease modeling [19] [3].

Another significant advantage lies in their application for personalized medicine. Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) can be utilized to examine the efficacy of various drugs, specifically tailoring treatments to individual genetic backgrounds and disease profiles [2] [22]. This more personalized approach helps improve treatment effectiveness while minimizing unwanted side effects. The technology also supports gene editing applications through techniques like CRISPR-Cas9, providing opportunities to study tumor gene mutations and disease mechanisms in a human-relevant context [19]. Additionally, organoids can be used to construct comprehensive biobanks, preserving diverse cellular models for research and therapeutic development [19].

Critical Validation Challenges and Experimental Solutions

Key Limitations in Current Organoid Models

Despite their promising applications, organoids face several significant challenges that limit their fidelity and reliability as experimental models. The diagram below illustrates the primary validation challenges and the corresponding experimental solutions being developed to address them.

The core challenges highlighted in the diagram manifest in specific ways that compromise organoid utility. Regarding cell type specification, while organoids contain broad cell types present in native tissues, they demonstrate impaired specification programs. Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses reveal that organoid-derived cells lack refined gene networks observed in endogenous development and show decreased expression of type-defining marker genes across multiple organoid protocols [20]. This suggests pervasive impairment in cell type specification that current protocols cannot fully overcome.

Structural and maturation limitations present another significant hurdle. Organoids typically exhibit a simplified version of native tissue architecture, such as forming ventricular zone-like rosettes instead of proper laminar sheets in neural organoids [20]. Furthermore, organoids often retain a fetal-like phenotype rather than maturing into adult tissue equivalents, limiting their utility for studying adult-onset diseases [3]. The lack of vascularization compounds these issues by restricting nutrient and oxygen diffusion, leading to hypoxic cores and necrosis in larger organoids [20] [3].

Experimental Validation Protocols

To address these challenges and bridge the in vitro-in vivo gap, researchers have developed sophisticated validation methodologies. The table below summarizes key experimental protocols for validating organoid models against in vivo standards, including the specific experimental setup, validation metrics, and purpose for each approach.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Organoid Model Validation

| Validation Method | Experimental Setup | Key Validation Metrics | Purpose/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Single-cell dissociation of organoids followed by RNA sequencing; comparison to primary tissue reference datasets [20] | Cell type diversity, expression of type-defining marker genes, identification of aberrant gene expression patterns [20] | Assessing fidelity of cell type specification; identifying atypical cellular states |

| Machine Learning Morphology Prediction | Convolutional neural networks trained on phase-contrast images from early organoid development to predict later differentiation outcomes [24] | Prediction accuracy (e.g., 79% accuracy for pituitary differentiation at day 40 using day 9 images); Grad-CAM visualization of decisive morphological features [24] | Non-invasive quality assessment; early prediction of organoid developmental potential |

| Immunofluorescence & Spatial Transcriptomics | Antibody staining for cell type-specific markers; spatial transcriptomics to map gene expression in organizational contexts [20] | Presence and distribution of key protein markers; correlation of spatial gene expression with native tissue architecture | Validating structural organization and cellular positioning within organoids |

| Electrophysiological Functional Assays | Multi-electrode arrays or patch clamping to record electrical activity in neural organoids [20] | Neural activity patterns, synaptic function, network synchronization | Assessing functional maturation and physiological relevance of neuronal organoids |

| Vascularization & Perfusion Models | Co-culture with endothelial cells; integration with microfluidic organ-on-chip platforms [3] [23] | Formation of endothelial networks; improved nutrient perfusion; reduction in hypoxic cores | Enhancing organoid size, maturity, and physiological relevance |

The application of these validation protocols has yielded critical insights into organoid biology. For instance, machine learning approaches have demonstrated that surface morphology features such as budding patterns and texture in early organoid development can predict successful differentiation with 79% accuracy, outperforming human assessment particularly at early stages (day 9) [24]. Successful organoids typically show small budding areas with slightly rough surfaces, while failed organoids exhibit smooth or irregularly rough textures often associated with mislocalized neural or retinal cells [24].

Similarly, single-cell RNA sequencing validation has revealed that organoids chronically express cellular stress genes across all cell types, indicating metabolic stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and electron transport dysfunction not typically observed in normal neural development [20]. This chronic stress response may interfere with proper developmental programs, highlighting a critical area for protocol improvement.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Validation

The successful culture and validation of organoids depends critically on a suite of specialized research reagents that support their development and mimic native tissue microenvironments. The table below details essential reagent solutions, their specific functions, and examples of their application in organoid research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Culture and Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Organoid Culture | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| R-spondin 1 | Activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling by binding Lgr5 receptor; supports stem cell self-renewal and proliferation [2] | Essential for long-term expansion of intestinal, mammary, and hepatic organoids; cooperates with Noggin to maintain Lgr5+ stem cell populations [2] |

| Noggin | BMP signaling pathway inhibitor; modulates cell differentiation and coordinates Wnt signaling to activate stem cells [2] | Required for liver organoid culture where BMP suppression is crucial; enables expansion by inhibiting differentiation-promoting BMP signals [2] |

| Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) | Binds EGFR to induce proliferative signaling cascades; supports self-renewal and expansion of adult stem cell populations [2] | Critical for liver, thyroid, gastrointestinal, and brain organoids; depletion leads to cellular quiescence and differentiation rather than proliferation [2] |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides 3D structural support mimicking basal membrane; enables self-organization and polarization of cells [19] [18] | Standard requirement for most organoid cultures; Matrigel is commonly used but research focuses on defined, GMP-grade alternatives [3] |

| Wnt Agonists | Enhance Wnt pathway activation crucial for stem cell maintenance and proliferation in various epithelial tissues [2] | Particularly important for intestinal and colon organoids; required alongside R-spondin for optimal stem cell activity [2] |

| FGF10 & FGF2 | Support branching morphogenesis and proliferation in various organ systems; particularly important for foregut-derived organs [2] | Used in gastric organoid culture alongside EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin 1 to support growth across multiple passages [2] |

The critical importance of these reagents is demonstrated through functional validation assays. For example, bioactivity testing shows that recombinant human R-Spondin 1 induces TCF reporter activity in HEK293 cells with an EC50 of 0.0138-0.0163 µg/mL, while EGF stimulates EGFR reporter cells with approximately 56-fold induction [2]. These quantitative potency measurements are essential for standardizing organoid culture conditions across different laboratories and applications.

Furthermore, proper combination of these factors enables successful establishment of diverse organoid types. Experimental data demonstrates that EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin 1 together maintain intestinal, gastric, and colonic organoid growth through multiple passages and long-term culture processes [2]. The functional synergy between these components—where R-spondin activates Wnt signaling and Noggin inhibits BMP signaling—creates a balanced environment that supports stem cell maintenance while permitting appropriate differentiation.

Organoid technology represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities to model human development and disease in a physiologically relevant context. However, realizing the full potential of these models requires rigorous validation against in vivo benchmarks to ensure they faithfully recapitulate the complex cellular, structural, and functional properties of native tissues. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that while organoids already surpass traditional 2D cultures and animal models in several key metrics—particularly in maintaining human genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity—significant challenges remain in achieving complete physiological fidelity.

The future of organoid validation will likely involve increased integration of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence for quality assessment and prediction [24] [23], multi-omics characterization for comprehensive profiling [20] [23], microfluidic systems for enhanced physiological relevance [3] [23], and automated platforms for improved reproducibility [3]. Additionally, efforts to vascularize organoids and incorporate immune components will be crucial for creating more complete tissue models that better bridge the in vitro-in vivo gap [3] [23]. As these advancements converge, validated organoid models will increasingly accelerate drug discovery, enable more accurate disease modeling, and advance personalized medicine approaches—ultimately fulfilling their promise as transformative tools in biomedical research.

Organoids represent a groundbreaking advancement in biomedical research, offering three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models that remarkably recapitulate the architecture and functionality of human organs. These self-organizing structures, derived from stem cells or tissue-specific progenitors, have emerged as powerful tools bridging the gap between traditional two-dimensional cell cultures and complex in vivo models [25]. The development of organoid technology has revolutionized our approach to studying human development, disease mechanisms, and drug responses, providing unprecedented insights into organ-specific physiology and pathology.

According to a consensus definition endorsed by the hepatic, pancreatic, and biliary Organoid Consortium, organoids are "three-dimensional structures derived from pluripotent stem cells, progenitor, and/or differentiated cells that self-organize through cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions to recapitulate aspects of the native tissue architecture and function in vitro" [26]. This definition highlights the key characteristics that distinguish organoids from other 3D culture systems: their self-organization capacity and ability to mimic native tissue functionality.

The significance of organoid technology was recognized when Nature Methods named it "Method of the Year 2017," reflecting the excitement and promise of this rapidly evolving field [26]. Since the pioneering work on intestinal organoids in 2009, the field has expanded to include models for numerous organs, including brain, liver, kidney, lung, and many others [25] [27]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of brain, intestinal, liver, and cancer organoid systems, focusing on their validation against in vivo development and their applications in biomedical research.

Comparative Analysis of Organoid Systems

Brain Organoids

Generation Strategies and Key Features: Brain organoids are typically generated from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [28]. These organoids mimic various regions of the developing human brain, such as the cortex, midbrain, hippocampus, and cerebellum, through self-organization principles that recapitulate in vivo neurodevelopment [28]. Recent advancements include the development of multi-region brain organoids (MRBOs) that contain interconnected tissues from different brain regions, representing a significant leap forward in modeling the complex organization of the entire brain [29].

The generation of brain organoids typically involves embryoid body formation followed by neural induction and maturation in 3D culture conditions. These structures develop various neuronal subtypes, glial cells, and demonstrate functional neural network activity. Notably, recent models have even shown the formation of rudimentary blood-brain barrier components, enhancing their physiological relevance [29]. One key advantage of brain organoids is their ability to model human-specific aspects of brain development and disorders that cannot be adequately studied in animal models [25].

Validation Against In Vivo Development: Transcriptomic analyses have demonstrated that brain organoids recapitulate key aspects of human fetal brain development, with some models exhibiting up to 80% of the cell type diversity found in early human fetal brains [29]. These organoids have been shown to follow similar developmental trajectories as the human brain, with sequential emergence of specific neuronal subtypes and glial cells. Furthermore, brain organoids have successfully modeled the effects of genetic mutations associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, reproducing pathological features observed in patient brains [28].

Table: Brain Organoid Validation Metrics

| Validation Parameter | Findings | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Diversity | 80% of range of cell types in early fetal brain development [29] | Recapitulates cellular complexity of developing brain |

| Developmental Stage | Resembles 40-day-old human fetal brain [29] | Models early neurodevelopment events |

| Functional Maturation | Production of electrical activity and network responses [29] | Demonstrates functional neuronal properties |

| Blood-Brain Barrier | Early blood-brain barrier formation observed [29] | Includes critical neurovascular components |

| Disease Modeling | Recapitulates features of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington's disease [28] | Validates pathological relevance for neurodegenerative disorders |

Intestinal Organoids

Generation Strategies and Key Features: Intestinal organoids were among the first successfully established organoid systems and represent a well-characterized model for epithelial biology. These organoids can be generated from two main sources: intestinal stem cells isolated from biopsy tissues or pluripotent stem cells directed toward intestinal differentiation [30]. The breakthrough in intestinal organoid culture came with the identification of Lgr5+ stem cells at the base of intestinal crypts and the development of culture conditions containing essential niche factors like EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin [31].

Intestinal organoids form intricate crypt-villus structures containing all the major epithelial cell types found in the native intestine, including enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, and enteroendocrine cells [30]. These organoids exhibit key intestinal functions such as nutrient absorption, mucus secretion, and response to microbial signals. The ability to culture intestinal organoids from human tissue has been particularly valuable for studying patient-specific intestinal diseases and host-microbe interactions.

Validation Against In Vivo Development: Intestinal organoids closely mirror the cellular composition and organization of the native intestinal epithelium. Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses have confirmed that these organoids contain all the expected intestinal epithelial cell lineages with transcriptomic profiles similar to their in vivo counterparts [30]. Importantly, human intestinal organoids have been shown to contain certain cell types, such as motilin+ enteroendocrine cells and BEST4+/OTOP2+ cells, that are found in humans but not in mice, highlighting their value for studying human-specific intestinal biology [31].

Functional validation studies have demonstrated that intestinal organoids respond appropriately to key signaling pathways that regulate intestinal stem cell behavior in vivo, including Wnt, Notch, and BMP signaling [31]. When transplanted into mice, human intestinal organoids form tissue structures that closely resemble human intestinal epithelium, maintaining appropriate regional specificity (small intestinal vs. colonic characteristics) [31].

Liver Organoids

Generation Strategies and Key Features: Liver organoids can be generated through multiple approaches, including from tissue-derived liver cells (hepatocytes or cholangiocytes) or via differentiation of pluripotent stem cells [26]. Early liver organoid systems primarily utilized cholangiocyte organoids derived from biliary epithelial cells, which could be expanded long-term and differentiated toward hepatocyte-like cells [26]. More recent advances have enabled the direct expansion of primary hepatocytes as organoids, better maintaining their mature functional characteristics [26].

Liver organoids typically exhibit key hepatic functions, including albumin secretion, urea production, drug metabolism, and bile acid synthesis [26]. Advanced culture conditions incorporating factors like triiodothyronine (T3) have enabled the generation of more mature hepatocyte organoids (MHOs) with enhanced metabolic capabilities that more closely resemble adult human liver [26]. These improvements have significantly increased the utility of liver organoids for modeling liver diseases, drug screening, and studying liver regeneration.

Validation Against In Vivo Development: Liver organoids derived from adult tissue maintain the genetic and functional characteristics of their tissue of origin, including disease-specific phenotypes when generated from patients with genetic liver disorders [26]. For example, organoids from patients with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency or Alagille syndrome successfully mirror the pathological features observed in these patients [26].

Transcriptomic analyses have demonstrated that advanced liver organoid models closely match the gene expression profiles of primary human hepatocytes, particularly for genes involved in key metabolic pathways [26]. Functional validation studies have shown that liver organoids can perform essential hepatocyte functions at levels comparable to primary hepatocytes, including cytochrome P450 activity, albumin secretion, and LDL uptake [26]. When transplanted into mouse models of liver disease, liver organoids have been shown to integrate into the host liver and provide functional improvement, further validating their physiological relevance [26].

Table: Liver Organoid Functional Validation

| Functional Parameter | Validation Results | Physiological Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin Secretion | Only 2-4 folds lower than primary human hepatocytes [26] | Maintains key synthetic function of hepatocytes |

| Drug Metabolism | CYP450 activity demonstrated [26] | Capable of pharmaceutical compound processing |

| Maturation State | Transcriptome similar to adult liver with T3 supplementation [26] | Recapitulates mature hepatocyte phenotype |

| Disease Modeling | Mirrors pathology of A1AT deficiency and Alagille syndrome [26] | Preserves patient-specific disease phenotypes |

| In Vivo Function | Engraftment and functional improvement in mouse models [26] | Demonstrates physiological relevance |

Cancer Organoids

Generation Strategies and Key Features: Cancer organoids, particularly patient-derived organoids (PDOs), have emerged as powerful tools for modeling tumor biology and advancing precision oncology. These organoids are generated directly from patient tumor samples and can be expanded while preserving the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the original tumor [32] [5]. Cancer organoids have been successfully established from various cancer types, including colorectal, pancreatic, liver, breast, and prostate cancers [32] [33].

Cancer organoids maintain the histological architecture, genetic heterogeneity, and drug response profiles of the tumors from which they are derived [5]. They can be used to model tumor-stroma interactions, particularly when co-cultured with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) or immune cells [33]. Recent advances have enabled high-throughput drug screening using cancer organoids, allowing for the identification of patient-specific therapeutic responses and resistance mechanisms [32].

Validation Against In Vivo Development: Extensive genomic analyses have confirmed that cancer PDOs retain the mutational profiles, copy number variations, and gene expression patterns of their parent tumors, even after extended in vitro culture [5]. This genetic stability makes them valuable models for studying tumor evolution and clonal dynamics.

Multiple studies have demonstrated strong correlation between drug responses in cancer organoids and clinical outcomes in patients, validating their predictive value for treatment selection [32]. For example, in colorectal cancer, organoid drug sensitivity testing has shown high concordance with patient responses to chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies [5]. Cancer organoids have also been shown to maintain tumor-specific features such as hypoxia gradients, metabolic profiles, and stem cell hierarchies that resemble in vivo tumors [33].

Experimental Protocols for Organoid Generation

Brain Organoid Generation Protocol

The generation of multi-region brain organoids (MRBOs) involves a sophisticated multi-step process [29]:

Neural Induction: hPSCs are aggregated into embryoid bodies in low-attachment plates using neural induction media containing TGF-β/NODAL and WNT inhibitors to promote neural ectoderm formation.

Regional Specification: Neural progenitors are patterned toward specific brain regions using region-specific morphogens:

- Forebrain: Combined treatment with WNT and SHH inhibitors

- Midbrain: FGF8 and SHH activation

- Hindbrain: WNT and FGF activation

- Cortical: Sequential treatment with WNT and BMP inhibitors

3D Matrigel Embedding: Patterned neural progenitors are embedded in Matrigel droplets to support 3D organization and expansion.

Tissue Fusion: Separately generated region-specific organoids are combined using biological adhesives to create multi-region complexes that establish functional connections.

Maturation: Fused organoids are maintained in spinning bioreactors or agitated cultures with optimized media to promote neuronal differentiation, synaptogenesis, and network formation over 8-16 weeks.

The entire process takes approximately 10-20 weeks, resulting in organoids containing 6-7 million neurons with emerging regional identities, electrophysiological activity, and rudimentary blood-brain barrier formation [29].

Liver Organoid Generation Protocol

Liver organoids can be generated from either primary tissues or pluripotent stem cells using distinct protocols [26]:

Tissue-Derived Liver Organoids:

- Tissue Dissociation: Human liver biopsies are enzymatically digested to single cells or small clusters using collagenase-based solutions.

Epithelial Cell Enrichment: Hepatocytes or cholangiocytes are isolated using density centrifugation or magnetic-activated cell sorting (for EpCAM+ cells).

3D Culture Setup: Isolated liver cells are embedded in growth factor-reduced Matrigel and cultured in expansion media containing:

- Essential niche factors: EGF, HGF, FGF, R-spondin

- TGF-β pathway inhibition (A83-01)

- cAMP activation (forskolin)

- Wnt pathway activation

Organoid Expansion: Cultures are maintained with weekly passaging, with organoids typically appearing within 1-2 weeks and expanding for several months.

Hepatocyte Differentiation: For cholangiocyte-derived organoids, hepatocyte differentiation is induced by modifying media to include BMP, FGF, and HGF while withdrawing Wnt agonists [26].

PSC-Derived Liver Organoids:

- Definitive Endoderm Induction: hPSCs are directed toward definitive endoderm using Activin A with Wnt3a for 3 days.

Hepatic Endoderm Specification: Cells are treated with BMP4 and FGF2 to induce hepatic endoderm formation (5-7 days).

Hepatoblast Expansion: Hepatic endoderm cells are expanded as 3D organoids in media containing HGF, FGF, and niche factors.

Hepatocyte Maturation: Organoids are matured using advanced media supplements including T3, dexamethasone, and maturation factors to enhance functional characteristics [26].

Signaling Pathways in Organoid Development

The successful generation and maintenance of organoids require precise recapitulation of key developmental signaling pathways. These pathways regulate stem cell self-renewal, lineage specification, and tissue patterning in organoid cultures, mirroring their roles in vivo.

Key Signaling Pathways in Organoid Development

This diagram illustrates the essential signaling pathways active across different organoid systems and their primary functions in organoid development and maintenance. The conservation of these pathways across organoid types highlights their fundamental roles in tissue development and homeostasis.

Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Culture

Table: Essential Reagents for Organoid Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Organoid Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | Advanced DMEM/F12, B-27 Supplement, N-2 Supplement | Provides nutritional base and essential factors for stem cell maintenance |

| Growth Factors | EGF, FGF, HGF, R-spondin, Noggin, Wnt3a | Mimics niche signaling for proliferation and patterning |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, Collagen I, Laminin, dECM scaffolds | Provides 3D structural support and biochemical cues |

| Signaling Inhibitors A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor), LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor) | Controls differentiation and maintains stemness | |

| Differentiation Factors | Activin A, BMP4, FGF4, FGF10, Retinoic Acid | Directs lineage specification and tissue maturation |

| Metabolic Supplements | N-acetylcysteine, B27, N2, Lipid concentrates | Supports energy metabolism and specialized functions |

| Antibiotics | Primocin, Penicillin-Streptomycin, Normocin | Prevents microbial contamination in long-term cultures |

| Dissociation Reagents | Accutase, TrypLE, Dispase, Collagenase | Enables organoid passaging and single-cell applications |

The selection and optimization of culture reagents are critical for successful organoid generation and maintenance. Different organoid types require specific combinations of growth factors and signaling modulators to recapitulate their respective tissue niches [26] [5] [30]. For example, intestinal organoids require Wnt agonists, R-spondin, and Noggin for long-term expansion, while brain organoids need neural induction factors and patterning morphogens [31] [28]. Recent advances include the development of chemically defined matrices as alternatives to animal-derived Matrigel, improving reproducibility and translational potential [5].

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Organoid technology has transformed biomedical research by providing human-relevant models for studying disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. The applications span basic research, drug discovery, and personalized medicine approaches.

Disease Modeling: Organoids have been particularly valuable for modeling human genetic disorders, infectious diseases, and cancer. Brain organoids have successfully recapitulated key pathological features of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease, including protein aggregation, neuronal loss, and synaptic dysfunction [28]. Similarly, liver organoids from patients with genetic metabolic disorders have mirrored disease-specific phenotypes, enabling study of disease mechanisms and drug testing [26]. Cancer PDOs have proven exceptional tools for investigating tumor heterogeneity, drug resistance mechanisms, and tumor-microenvironment interactions [32] [33].

Drug Development and Screening: Organoids have significantly impacted the drug development pipeline by providing more predictive models for efficacy and toxicity testing. The high failure rate of neuropsychiatric drugs (approximately 96% in Phase 1 clinical trials) underscores the limitations of animal models for predicting human responses [29]. Brain organoids offer a human-based system for evaluating neurotoxicity and blood-brain barrier penetration early in drug development. Similarly, liver organoids provide platforms for predicting drug-induced liver injury, a major cause of drug attrition [26]. The capacity for high-throughput screening using organoid arrays has accelerated compound screening and lead optimization processes [32] [5].

Personalized Medicine: Cancer PDOs have emerged as powerful tools for personalized oncology, enabling functional testing of therapeutic responses in patient-specific models. Clinical studies have demonstrated that PDO drug sensitivity testing can predict patient responses to chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies with high accuracy [32]. This approach holds promise for guiding treatment selection and identifying resistance mechanisms in individual patients. Similarly, organoids from patients with genetic disorders allow for personalized drug testing and therapeutic optimization [26] [28].

Organoid technology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, providing unprecedented opportunities to study human biology and disease in physiologically relevant models. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that brain, intestinal, liver, and cancer organoids each offer unique advantages while sharing the common ability to recapitulate key aspects of their corresponding in vivo tissues. Validation studies across multiple organoid systems have consistently shown that these models maintain tissue-specific architecture, cellular heterogeneity, and functional capabilities that closely mirror their native counterparts.

While significant progress has been made in organoid technology, challenges remain in achieving full physiological maturity, incorporating all relevant cell types (particularly vascular and immune components), and enhancing reproducibility across laboratories. Ongoing advances in bioengineering, including organ-on-a-chip platforms, 3D bioprinting, and improved biomaterials, are addressing these limitations and pushing the boundaries of organoid complexity and functionality [32] [5].

As organoid technology continues to evolve, these models are poised to play an increasingly central role in basic research, drug development, and clinical medicine. Their ability to bridge the gap between traditional cell culture and animal models makes them invaluable tools for understanding human biology and disease, ultimately accelerating the development of more effective and personalized therapies.

From Theory to Practice: Advanced Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) for Personalized Therapy Selection

The high failure rate of anticancer drugs in clinical trials, exceeding 85% in some estimates, underscores a critical gap between traditional preclinical models and human pathophysiology [3]. Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) have emerged as transformative three-dimensional (3D) ex vivo models that bridge this translational gap by faithfully retaining the genetic, phenotypic, and functional characteristics of original patient tumors [14] [34]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of PDO performance against established models, detailing experimental protocols and validation data that position PDOs as essential tools for therapy selection within precision oncology frameworks.

The fundamental strength of PDOs lies in their ability to mimic in vivo development and disease states. By conserving the cellular composition and architecture of native tissues, they provide a physiologically relevant platform for assessing drug sensitivity and resistance mechanisms [34]. For drug development professionals, this translates to improved clinical predictivity at the preclinical stage, enabling more reliable go/no-go decisions and reducing late-stage attrition.

Model Comparison: PDOs Versus Alternative Preclinical Platforms

Performance Metrics Across Model Types

Different preclinical models offer varying advantages and limitations for drug development applications. The table below provides a systematic comparison of key performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of preclinical cancer models

| Model Characteristic | 2D Cell Cultures | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Complexity | Low (monolayer) [35] | High (in vivo context) [36] | Moderate to High (3D structure) [14] [37] |

| Genetic Stability | Low (clonal selection) [34] | High [36] | High (long-term culture) [36] [34] |

| Tumor Microenvironment | Absent or limited | Preserved (murine stroma) | Modifiable (co-culture possible) [14] [34] |

| Throughput Capacity | High | Low (costly, time-consuming) [36] [37] | Medium to High [36] |

| Timeline for Establishment | Weeks | 6+ months [38] | 2-3 weeks [38] |

| Clinical Predictive Value | Variable, often poor [34] | High (>90% correlation) [36] | High (76% accuracy) [14] |

| Cost Efficiency | High | Low | Medium [36] |

Validation Against Clinical Responses

The validation of PDOs against actual patient outcomes provides the most compelling evidence for their clinical relevance. The following table summarizes quantitative data from multiple studies across different cancer types.

Table 2: PDO predictive performance across cancer types

| Cancer Type | Therapeutic Class | Correlation with Patient Response | Key Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | Chemotherapy, Targeted therapy | 76% overall accuracy | Sensitivity: 0.79, Specificity: 0.75 | [14] |

| Metastatic CRC | Irinotecan-based chemotherapy | >80% predictive accuracy | Prevented misclassification of potential responders | [35] |

| Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | 111 FDA-approved drugs | High PDO-PDOX concordance | Correlation with clinical outcomes | [39] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Platinum-based therapy | Reliably reflected patient sensitivity | Distinguished sensitive/resistant/refractory cases | [37] |

| Multiple Cancers | Various (PDX-derived organoids) | >90% biological equivalency | High correlation with matched PDX drug response | [36] |

Experimental Protocols for PDO-Based Therapeutic Screening

Core Methodology for PDO Establishment and Drug Screening

The standard workflow for generating and utilizing PDOs in therapy selection involves multiple critical stages, each requiring specific technical expertise and quality control measures.

Tissue Processing and Digestion: Surgical specimens or biopsy materials are washed with PBS and subjected to enzymatic digestion using specialized kits (e.g., human tumor dissociation kit from Miltenyi Biotec) [39]. The resulting cell suspension is filtered through 100-micron strainers to remove large fragments, and viable cells are counted.

Matrix Embedding and Culture: Dissociated cells are embedded in ice-cold extracellular matrix (ECM) substitutes like Matrigel (Corning) or other gelatinous protein mixtures [39] [37]. After polymerization at 37°C, the matrix is overlaid with organoid-specific culture medium. The precise composition varies by cancer type but typically includes:

- Advanced DMEM/F12 as basal medium

- Wnt pathway agonists (e.g., Wnt3A-conditioned medium)

- R-spondin-1 (ligand for LGR5 receptor)

- Noggin (BMP pathway inhibitor)

- Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF)

- N-acetylcysteine (antioxidant)

- A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor)

- Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor, prevents anoikis) [39] [34]

Expansion and Biobanking: Organoids are typically passaged every 1-2 weeks using enzymatic or mechanical dissociation [39]. For long-term storage, organoids are cryopreserved in medium containing 90% FBS and 10% DMSO, maintaining viability and characteristics in liquid nitrogen [39].

Advanced Functional Drug Screening Protocols

High-Throughput Screening Platforms: For comprehensive drug profiling, PDOs are seeded in standardized sizes (350-450μm) into multi-well plates for systematic exposure to therapeutic agents [14]. The Therapeutically-Guided Multidrug Optimization (TGMO) platform enables efficient screening of single agents and combination therapies across concentration gradients [14].

Viability and Response Assessment:

- CellTiter-Glo 3D Assay: Measures ATP content as a viability indicator, with strong correlation to cell numbers (R² = 0.988) [40]

- High-Content Imaging: Automated microscopy coupled with AI-based analysis tools like OrgaExtractor quantifies morphological changes [40]

- Immunohistochemical Analysis: Marker expression (Ki67, CA19-9, CEA, PD-L1) evaluated in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded organoid sections [39]

Combination Therapy Evaluation: PDOs enable systematic optimization of multi-drug regimens. For example, the TGMO platform has been applied to screen combinations of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., regorafenib, vemurafenib, palbociclib, lapatinib) at low doses, achieving up to 88% reduction in PDO viability [14].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for PDO applications

| Reagent/Technology Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel (Corning) [39] | Provides 3D structural support for organoid growth | Lot-to-lot variability requires quality control |

| Culture Medium Additives | Wnt3A, R-spondin-1, Noggin [34], N-acetylcysteine [39] | Maintain stemness and support proliferation | Conditioned media or recombinant proteins |

| Dissociation Reagents | TrypLE (Gibco) [37], Tumor Dissociation Kits (Miltenyi) [39] | Break down organoids for passaging or analysis | Enzymatic composition varies by tissue type |

| Viability Assays | CellTiter-Glo 3D [40] | Quantify metabolic activity/cell viability | Optimized for 3D structures |

| Imaging & Analysis | OrgaExtractor (AI tool) [40], Two-photon microscopy [41] | Automated organoid segmentation and analysis | Enables high-content screening |

| Specialized Media | Advanced DMEM/F12 [39], B-27 Supplement [39] | Base nutrient medium | Formulations specific to organoid cultures |

Key Signaling Pathways in PDO Biology and Therapeutic Targeting

The maintenance and drug response of PDOs are governed by critical signaling pathways that represent both therapeutic targets and essential culture requirements.

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: Serves as a master regulator of stem cell maintenance. In colorectal cancer PDOs, Wnt signaling is essential for long-term culture, often provided via Wnt3A-conditioned medium [34]. Therapeutic targeting of this pathway demonstrates differential effects based on mutational status.

EGFR Signaling: Epidermal Growth Factor receptor signaling drives proliferation in many epithelial cancers. PDOs retain expression of EGFR family members, making them responsive to targeted inhibitors like lapatinib [14].