Beyond Redundancy: Advanced Strategies for Unraveling Hox Gene Function in Development and Disease

Functional redundancy among Hox genes, resulting from gene duplication events in vertebrate evolution, has long been a significant obstacle in genetic studies, often masking phenotypic consequences in single-gene knockout models.

Beyond Redundancy: Advanced Strategies for Unraveling Hox Gene Function in Development and Disease

Abstract

Functional redundancy among Hox genes, resulting from gene duplication events in vertebrate evolution, has long been a significant obstacle in genetic studies, often masking phenotypic consequences in single-gene knockout models. This article synthesizes current strategies to overcome this challenge, exploring the evolutionary origins of redundancy and detailing advanced methodological approaches, including multi-cluster CRISPR deletions and ecological fitness assays. We examine how researchers are systematically troubleshooting knockout studies by targeting specific paralogous groups and regulatory landscapes. Furthermore, we discuss rigorous validation techniques that demonstrate functional divergence between Hox paralogs, providing crucial insights for developmental biology and revealing new therapeutic targets in HOX-dysregulated diseases such as cancer.

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Hox Gene Redundancy: From Gene Duplication to Functional Overlap

FAQs: Overcoming Functional Redundancy in Hox Gene Research

What is the fundamental challenge of studying Hox gene function, and why does it occur?

The primary challenge is functional redundancy, where the loss of a single Hox gene is often compensated for by other members of the same paralog group. This occurs because vertebrates possess multiple Hox clusters (A, B, C, D) resulting from whole-genome duplications (WGDs), and genes within the same paralog group (e.g., Hoxa5, Hoxb5, Hoxc5) share similar sequences and often overlapping expression patterns and functions [1] [2]. Consequently, single gene knockouts may not reveal a phenotype, masking the gene's true developmental role.

What evolutionary events led to this redundancy in vertebrate Hox genes?

Vertebrate Hox clusters originated from two rounds of whole-genome duplication (1R and 2R) in the early vertebrate lineage. Evidence from cyclostome (hagfish and lamprey) genomes supports that 1R occurred in the vertebrate stem-lineage, while 2R occurred in the gnathostome (jawed vertebrate) stem-lineage after its divergence from cyclostomes [3]. This expanded the ancestral single Hox cluster into the four clusters (A, B, C, D) found in most jawed vertebrates, creating widespread genetic redundancy and increasing evolvability [4] [5].

Table 1: Hox Cluster Duplication Events in Vertebrate Evolution

| Event | Proposed Timing | Genomic Outcome | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1R WGD | Early Cambrian | Single cluster → Two clusters | Inferred ancestral vertebrate karyotype reconstruction [3] |

| 2R WGD | Late Cambrian-Earliest Ordovician | Two clusters → Four clusters (in gnathostomes) | Genome synteny analysis; divergence from cyclostome lineage [3] |

| Teleost-specific WGD | After divergence from sturgeons | Four clusters → Up to eight clusters (e.g., in zebrafish) | Genomic analyses of teleost fishes [4] |

What is the most effective genetic strategy to overcome this redundancy?

Generating compound mutant mice—animals with simultaneous mutations in two or more Hox genes from the same paralog group—is a proven and effective strategy. For example, while single Hoxb5 or Hoxc5 mutants show no overt lung phenotype, and Hoxa5 single mutants do, Hoxa5;Hoxb5 compound mutants display an aggravated lung phenotype, leading to neonatal lethality and revealing specific and redundant roles for Hoxb5 in branching morphogenesis and goblet cell specification [1].

What critical phenotypic data should I analyze in Hox compound mutants?

A multi-faceted phenotypic analysis is crucial. Key endpoints include:

- Viability and Gross Morphology: Note neonatal lethality and overall organ structure [1].

- Histology: Use stains like Hematoxylin and Eosin (general morphology), Alcian blue (goblet cells/mucus), and Weigert (elastic fibers) [1].

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF): Analyze cell proliferation (e.g., phospho-histone H3), apoptosis (e.g., cleaved caspase-3), and cell-type-specific markers (e.g., CC10, pro-SP-C, T1α, PECAM-1) [1].

- Morphometry: Quantify structural complexity using methods like radial alveolar count in the lung [1].

Table 2: Phenotypic Severity in Hox5 Paralog Mutants

| Genotype | Viability | Lung Phenotype Severity | Key Phenotypic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Viable | Normal | Normal branching, air space structure, and cell differentiation. |

Hoxb5−/− |

Viable | None reported | No overt lung defects described [1]. |

Hoxc5−/− |

Viable | None reported | No organ defects described [1]. |

Hoxa5−/− |

High neonatal mortality | Severe | Tracheal and lung dysmorphogenesis, emphysema-like phenotype in survivors [1]. |

Hoxa5−/−; Hoxb5−/− |

Lethal at birth | More severe than Hoxa5−/− alone |

Aggravated lung hypoplasia, defects in branching morphogenesis and goblet cell specification [1]. |

Are there new genomic technologies to study Hox gene regulation?

Yes, cutting-edge genomic technologies are essential for probing the complex regulatory landscape of Hox clusters. Key methods include:

- ATAC-seq: To identify open chromatin regions and map accessible cis-regulatory elements genome-wide [6].

- ChIP-seq: To determine the in vivo binding sites of Hox transcription factors and their co-factors, as well as histone modifications that mark active or repressed chromatin states [6].

- Spatial Transcriptomics (e.g., Curio): To map gene expression patterns within the context of the tissue architecture, directly linking Hox gene expression to specific anatomical locations [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating and Analyzing Hox Compound Mutant Mice

This protocol is adapted from research on Hoxa5;Hoxb5 compound mutants [1].

1. Generation of Compound Mutants

- Crossing Strategy: Mate single heterozygous (

Hoxa5+/−andHoxb5+/−) mice to generate double heterozygous (Hoxa5+/−;Hoxb5+/−) animals. Intercross these double heterozygotes to generate embryos of all possible genotypic combinations. - Genotyping: Perform Southern blot analysis or PCR on genomic DNA from experimental animals to identify all genotypes reliably.

2. Tissue Collection and Processing

- Collection: Collect lungs and other relevant tissues from wild-type and mutant embryos at key developmental stages (e.g., E13.5, E15.5, E18.5). Record wet lung and body weights.

- Fixation: Fix tissues in 4% cold paraformaldehyde.

- Embedding and Sectioning: Process fixed tissues through a graded ethanol series, clear in xylene, embed in paraffin, and section at 4 μm thickness.

3. Histological and Molecular Phenotyping

- Standard Staining:

- Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E): For general morphology.

- Alcian Blue: To detect mucus-producing goblet cells.

- Weigert with tartrazine: To visualize elastic fibers.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC):

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate sections.

- Perform antigen retrieval if required.

- Block endogenous peroxidases and apply blocking serum.

- Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., anti-phospho-Histone H3, anti-cleaved caspase-3).

- Incubate with a biotinylated secondary antibody, followed by an avidin-biotin-enzyme complex (ABC).

- Develop with a chromogen like DAB and counterstain.

- Quantitative Analysis:

- For proliferation indices, count pHH3-positive cells and total cell number in multiple random fields.

Protocol: Giemsa Banding (G-banding) for Karyotype Confirmation

G-banding is used for precise chromosomal identification, which is crucial when working with genetic models [7] [8].

Reagents & Equipment:

- Trypsin 2.5% solution (2.5 mL trypsin 10X + 49.5 mL 0.9% NaCl)

- Gurrs Giemsa stain (R66)

- Gurrs 6.8 Buffer

- 0.9% Sodium Chloride (NaCl)

- Acetone

- Coplin jars, forceps, coverslips, 50°C oven

Procedure:

- Set up six Coplin jars with the following solutions:

- Jar 1: 0.125% trypsin/0.9% NaCl mixture

- Jars 2 & 3: 0.9% NaCl for rinsing

- Jar 4: Gurrs Giemsa stain mixed with Gurrs 6.8 buffer and acetone

- Jars 5 & 6: Gurrs 6.8 buffer for rinsing

- Trypsinization: Dip a slide in the trypsin solution (Jar 1) for 10 seconds to 2 minutes. Timing is critical and must be optimized based on trypsin activity.

- Rinsing: Rinse the slide by sequential dipping in the two 0.9% NaCl rinsing jars (Jars 2 & 3).

- Staining: Place the slide in the Giemsa stain (Jar 4) for 5 minutes.

- Final Rinsing: Remove the slide and rinse by sequential dipping in the two Gurrs buffer jars (Jars 5 & 6).

- Drying and Mounting: Air-dry the slide, coverslip with a mounting medium, and dry in a 50°C oven. The slide is now ready for metaphase analysis under a microscope [8].

Visualizing Evolutionary and Experimental Relationships

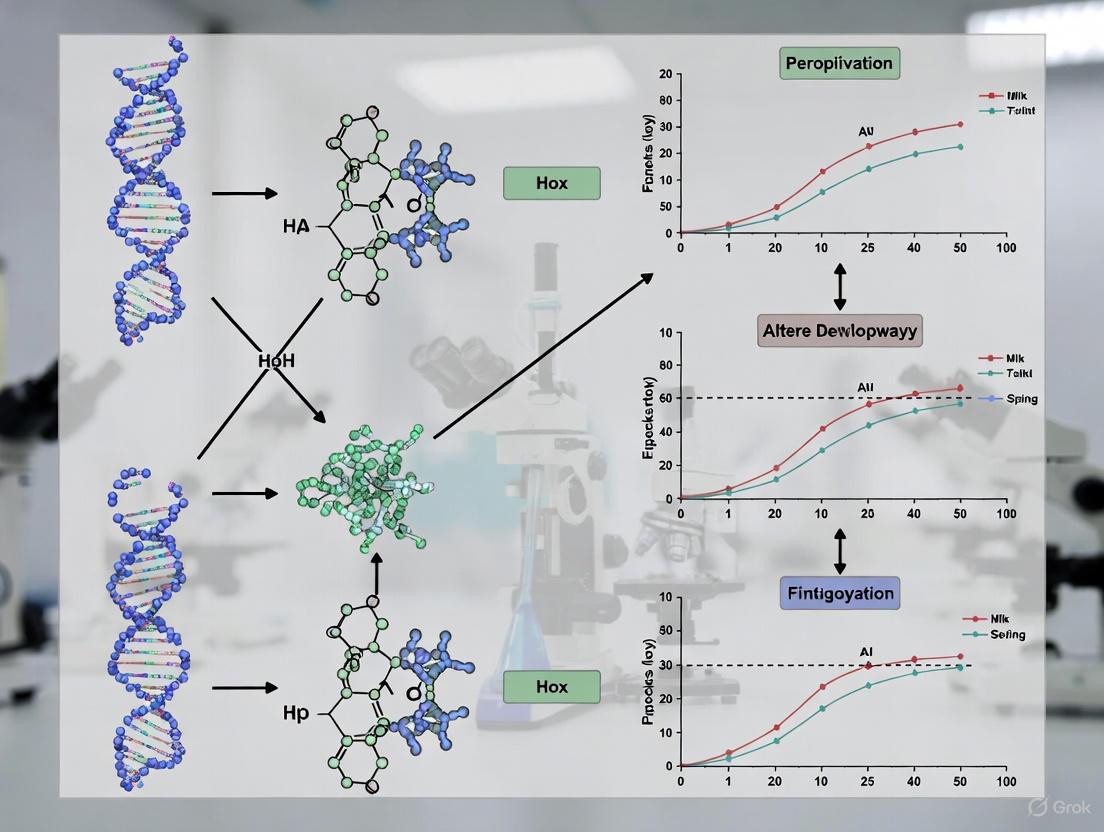

Diagram 1: From Duplication to Experimental Solution

Diagram 2: Tackling Paralogue Redundancy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene Functional Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Mutant Mice | In vivo model to dissect functional redundancy between Hox paralogs. | Hoxa5;Hoxb5 mutants to uncover redundant roles in lung development [1]. |

| Antibodies for IHC/IF | Cell and tissue phenotyping. | Anti-pHH3 (proliferation), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (apoptosis), anti-CC10 (club cells), anti-PECAM-1 (endothelium) [1]. |

| Histological Stains | Visualizing tissue morphology and specific components. | Alcian Blue (acidic mucins), Weigert's stain (elastic fibers) [1]. |

| Giemsa Stain (G-banding) | Chromosome identification and karyotype confirmation. | Verifying chromosomal integrity and identifying large-scale abnormalities in mutant lines [7] [8]. |

| ATAC-seq & ChIP-seq Kits | Profiling chromatin accessibility and transcription factor binding. | Identifying active cis-regulatory elements and Hox gene targets genome-wide [6]. |

FAQs: Understanding Functional Redundancy in Gene Knockout Studies

Q1: Why does knocking out a single Hox gene sometimes fail to produce an observable phenotype?

A1: A single Hox gene knockout may not show a phenotype due to functional redundancy with its paralogs. Genes originating from duplication events, especially whole-genome duplications (WGD), are often retained because their proteins participate in multicomponent interactions like transcription factors and signal transduction [9]. When genes are functionally redundant, the presence of a paralog can compensate for the loss of the knocked-out gene, masking its function [1]. For instance, single mutants for Hoxb5 or Hoxc5 show no overt lung phenotype, whereas Hoxa5 mutants do, suggesting Hoxa5 function is less easily rescued but also hinting at potential compensation by other paralogs [1].

Q2: What are the common evolutionary fates of duplicated genes?

A2: After a duplication event, gene copies typically follow one of several paths [9]:

- Nonfunctionalization: The most common fate, where one copy accumulates deleterious mutations and becomes a non-functional pseudogene [9].

- Neofunctionalization: One copy acquires a mutation that gives it a novel, beneficial function, which is then preserved by natural selection [9].

- Subfunctionalization: The ancestral functions of the gene are partitioned between the two duplicates, often through complementary mutations in regulatory elements or protein domains [9] [10].

- Hypofunctionalization: Both copies undergo reduced expression, and the duplicate pair is maintained because the combined output is necessary for a critical function [9].

Q3: How can I experimentally overcome functional redundancy in my Hox gene research?

A3: To address functional redundancy, you must create compound mutants. This involves knocking out multiple paralogous genes simultaneously to uncover their combined roles [1]. For example, while Hoxa5 single mutants have a severe lung phenotype and Hoxb5 single mutants are viable with no reported defects, Hoxa5;Hoxb5 compound mutants display an aggravated lung phenotype, leading to neonatal death and revealing the partial redundant functions of Hoxb5 [1]. This demonstrates that compound mutagenesis is essential to unravel the full contribution of paralogous genes.

Q4: What is the relationship between subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization?

A4: Research suggests that subfunctionalization may act as a transition state to neofunctionalization rather than a terminal fate [10]. By partitioning ancestral functions, subfunctionalization can preserve a duplicate copy in the genome. This provides an evolutionary time window for one copy to accumulate mutations that may lead to a new function, ultimately resulting in neofunctionalization [10]. There is typically no long-term selective pressure to maintain simple genetic redundancy [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating Redundancy in Hox Gene Knockouts

Problem: No Phenotype Observed in Single Hox Gene Knockout

This guide outlines a systematic approach to confirm and investigate functional redundancy.

Step 1: Confirm Redundancy Hypothesis

- Action: Verify the expression patterns of paralogous genes.

- Protocol: Perform RNA in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry on wild-type embryos at relevant developmental stages. Check for overlapping expression domains of the target gene and its paralogs [1].

- Expected Data: Significant overlap in spatiotemporal expression, particularly in the mesenchyme for Hox genes, supports the potential for functional redundancy [1].

Step 2: Design and Generate Compound Mutants

- Action: Cross single mutant lines to generate animals with mutations in multiple paralogous genes.

- Protocol:

- Mate

Hoxa5+/-mice withHoxb5-/-mice to obtain double heterozygous animals (Hoxa5+/-; Hoxb5+/-) [1]. - Intercross the double heterozygotes to generate embryos of all possible genotypic combinations, including the compound homozygous mutants (

Hoxa5-/-; Hoxb5-/-) [1]. - Genotype embryos using Southern blot analysis or PCR [1].

- Mate

Step 3: Phenotypic Characterization of Compound Mutants

- Action: Conduct a detailed morphological and molecular analysis of the compound mutants compared to wild-type and single mutants.

- Protocol:

- Histology: Collect and fix embryonic lungs (e.g., at E18.5). Process for paraffin embedding, section, and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to assess general morphology [1].

- Special Stains:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Use primary antibodies against cell-type-specific markers to assess cell fate specification. Example antibodies include:

- Proliferation/Apoptosis Assays:

Step 4: Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Action: Compare the severity of phenotypes across genotypes.

- Expected Outcome: A more severe phenotype in the compound mutant (e.g.,

Hoxa5-/-; Hoxb5-/-) compared to any single mutant (Hoxa5-/-orHoxb5-/-) confirms partial functional redundancy and reveals the collective role of the paralogs [1].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Evolutionary Fates of Duplicated Genes

| Fate | Description | Key Features | Likelihood in WGD vs. SSD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonfunctionalization | One copy loses function via deleterious mutations and is eventually lost. | Most common fate; returns the locus to a singleton state [9]. | High for both, but overall the most probable outcome. |

| Neofunctionalization | One copy acquires a new, adaptive function. | Generates evolutionary novelty; both copies are retained long-term [9]. | WGD genes are often involved in complex functions (e.g., signaling, development), making this fate significant [11]. |

| Subfunctionalization | Duplicates partition the ancestral gene's sub-functions. | Can be a neutral process that preserves duplicates; may be a transition to neofunctionalization [10]. | Facilitated by WGD due to dosage balance preservation [9]. |

| Hypofunctionalization | Both copies undergo reduced expression, but their combined output is essential. | Maintains duplicates through dosage sharing; expression can diverge in specific tissues [9]. | Common in WGD-derived pairs due to dosage constraints [9]. |

Table 2: Phenotypic Comparison of Hox5 Paralog Mutants in Mouse Lung Development

| Genotype | Viability | Key Lung Phenotypes | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Viable | Normal branching morphogenesis, air space structure, and goblet cell distribution [1]. | Baseline normal development. |

| Hoxa5-/- | High neonatal mortality | Tracheal and lung dysmorphogenesis; surviving adults show emphysema-like air space enlargement and goblet cell metaplasia [1]. | Hoxa5 plays a unique and critical role, with limited compensation. |

| Hoxb5-/- | Viable | No overt lung phenotype reported in single mutants [1]. | Hoxb5 function is redundant or subtle under baseline conditions. |

| Hoxa5-/-; Hoxb5-/- | Lethal at birth | Aggravated lung phenotype: severe branching defects, goblet cell specification defects, and disrupted postnatal air space structure [1]. | Hoxa5 and Hoxb5 share partially redundant functions during lung morphogenesis. |

Experimental Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Fate of Duplicated Genes Post-WGD

Diagram 2: Hox Gene Redundancy Investigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Hox Gene Redundancy

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example/Target |

|---|---|---|

| Mutant Mouse Lines | In vivo models for studying gene function and genetic interactions. | Hoxa5 and Hoxb5 mutant lines [1]. |

| Primary Antibodies | Detection of specific cell types and processes via IHC/IF. | Pro-SP-C (alveolar type II cells), T1α (alveolar type I cells), CC10 (Clara cells), FOXA2 (endoderm), pHH3 (proliferation), Cleaved Caspase-3 (apoptosis) [1]. |

| Histological Stains | Visualization of tissue morphology and specific components. | Hematoxylin & Eosin (general structure), Alcian Blue (goblet cells/mucus), Weigert's stain (elastic fibers) [1]. |

| Genotyping Tools | Identification of animal genotypes. | Southern blot analysis or PCR protocols [1]. |

| Fixative | Tissue preservation for histological processing. | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [1]. |

FAQs: Addressing Core Challenges in Hox Gene Research

Q1: Why do many single Hox gene knockouts fail to show obvious developmental phenotypes?

A: This occurs primarily due to functional redundancy among Hox paralogs. Genes within the same paralog group share similar protein structures and expression patterns, enabling them to compensate for each other's loss [1] [12]. For instance, in the Hox5 paralog group, Hoxa5 single mutants exhibit significant lung defects, whereas Hoxb5 single mutants show no overt phenotype because Hoxa5 can compensate for its loss [1]. This suggests a threshold level of HOX5 proteins is required for normal development, which can be maintained by remaining paralogs [1].

Q2: What experimental evidence demonstrates functional redundancy between Hox genes?

A: Compound mutant studies provide the strongest evidence. Research on Hoxa5 and Hoxb5 showed that mutants carrying all four mutated alleles died at birth with aggravated lung defects, while single mutants were viable [1]. Similarly, in kidney development, knockout of the entire Hox11 paralog group abolishes kidney development, whereas single or double knockouts show less severe phenotypes [12]. These findings confirm that Hox paralogs share functions during organogenesis [1].

Q3: What advanced methodologies can detect subtle phenotypes in single Hox knockouts?

A: Single-cell, whole-embryo RNA sequencing provides unprecedented resolution. One study profiled over 1.6 million nuclei from 101 mouse embryos, identifying molecular and cellular changes in mutants that previously showed no overt physical abnormalities [13]. This approach can detect composition changes and gene expression differences across 52 cell types, revealing phenotypes that conventional methods miss [13].

Q4: How can researchers overcome redundancy to study Hox gene function?

A: Several strategies exist:

- Generate compound mutants targeting multiple paralogs within the same group [1]

- Use CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis for functional testing in diverse model organisms [14]

- Implement single-cell genomic approaches to identify subtle molecular changes [13]

- Analyze expression patterns to identify paralogs with overlapping domains that may compensate for each other [1]

Q5: Are there documented cases where single Hox knockouts do show clear phenotypes?

A: Yes, some single Hox knockouts produce distinct phenotypes, indicating they have unique, non-redundant functions. For example:

- Hoxa5 single mutants display tracheal and lung dysmorphogenesis with high neonatal mortality [1]

- Hoxa13 mutations cause hand-foot-genital syndrome in humans [12]

- In crustaceans, CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of individual Hox genes like Ubx, abd-A, and Abd-B causes specific homeotic transformations despite the presence of paralogs [14]

Quantitative Data on Hox Knockout Phenotypes

Table 1: Documented Phenotypes in Hox5 Paralog Group Mutants [1]

| Genotype | Viability | Lung Phenotype | Tracheal Phenotype | Other Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Viable | Normal | Normal | None |

| Hoxa5-/- | Neonatal lethality | Emphysema-like, goblet cell metaplasia | Dysmorphogenesis | Diaphragm innervation defects |

| Hoxb5-/- | Viable | No overt defects | Not reported | None reported |

| Hoxa5-/-;Hoxb5-/- | Neonatal lethality | Aggravated defects, impaired branching | Not studied | Not studied |

Table 2: Phenotype Severity Based on Number of Hox Paralogs Inactivated [12]

| Genes Inactivated | Kidney Phenotype | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Single Hox11 gene | Normal development | Full compensation by other paralogs |

| Two Hox11 genes | Kidney hypoplasia | Partial compensation |

| All Hox11 paralogs | No kidney initiation | Complete loss of function |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Hox Redundancy

Protocol 1: Generating and Analyzing Compound Hox Mutants

Application: Systematically testing functional redundancy within Hox paralog groups [1].

Workflow:

- Mouse mating scheme: Cross single heterozygous mutants to obtain double heterozygous animals, then intercross to generate all allelic combinations

- Genotyping: Perform Southern blot analysis or PCR-based genotyping of offspring

- Embryo collection: Collect embryos at critical developmental stages (E13.5, E15.5, E18.5 for lung development studies)

- Phenotypic analysis:

- Measure wet lung/body weight ratios

- Histological staining (H&E for morphology, Alcian Blue for goblet cells)

- Immunohistochemistry for cell type markers (CC10, podoplanin, FOXA2, pro-SP-C)

- Cell proliferation assays (phospho-histone H3 immunostaining)

- Apoptosis assays (cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining)

Key Materials:

- Hox mutant mouse lines (maintain inbred background, e.g., 129/Sv)

- Primary antibodies against relevant markers

- Paraformaldehyde for fixation

- Paraffin embedding equipment

Protocol 2: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Phenotyping Hox Mutants

Application: Detecting subtle molecular and cellular phenotypes in Hox mutants [13].

Workflow:

- Embryo collection: Stage embryos precisely (e.g., E13.5)

- Nuclei isolation: Prepare single-cell or single-nucleus suspensions from whole embryos

- Library preparation: Use combinatorial indexing-based scRNA-seq (e.g., sci-RNA-seq)

- Sequencing: Profile approximately 16,000 nuclei per embryo

- Data analysis:

- Quality control (remove doublets, low-quality cells)

- Cell type identification using reference atlas (e.g., Mouse Organogenesis Cell Atlas)

- Differential abundance testing across cell types

- Pseudobulk analysis for genotype effects

- Trajectory inference for developmental processes

Key Materials:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing reagents

- Computational resources for large-scale data analysis

- Reference datasets for cell type annotation

Protocol 3: CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis in Emerging Model Organisms

Application: Functional testing of Hox genes in diverse evolutionary contexts [14].

Workflow:

- Target selection: Design gRNAs against Hox genes of interest

- CRISPR/Cas9 delivery: Inject Cas9 protein/gRNA complexes into early embryos

- Somatic mutagenesis: Analyze resulting mosaic animals for homeotic transformations

- Phenotypic documentation: Image and characterize limb/specialized appendage transformations

- Validation: Confirm target gene disruption and correlate with expression domains

Key Materials:

- CRISPR/Cas9 reagents (Cas9 protein, synthetic gRNAs)

- Microinjection equipment

- Species-specific rearing facilities

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Hox Redundancy Investigation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Redundancy Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Key Features | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound mutant mice | In vivo functional redundancy testing | Multiple Hox paralogs inactivated | Hoxa5;Hoxb5 double mutants [1] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Gene editing in diverse models | Somatic and germline mutagenesis | Parhyale limb specification studies [14] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Detecting subtle phenotypes | High-resolution molecular profiling | Whole-embryo mutant characterization [13] |

| Hox-specific antibodies | Protein expression analysis | Spatial expression patterns | IHC for Hox protein distribution |

| Primary cell markers | Cell type identification | Tissue-specific markers | CC10 (airway cells), podoplanin (lung epithelium) [1] |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Contextual gene expression | Maintains tissue architecture | Mapping Hox expression domains |

The Principle of Collinearity and Its Role in Axial Patterning and Limb Positioning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the principle of collinearity in Hox gene function, and why is it a source of functional redundancy in knockout studies? The principle of collinearity describes the phenomenon where the order of Hox genes on chromosomes corresponds to both their temporal and spatial expression patterns along the embryo's anterior-posterior axis, as well as the anatomical boundaries of their function [15]. Genes at the 3' end of a cluster are expressed earlier and more anteriorly, while genes at the 5' end are expressed later and more posteriorly. This spatial and temporal organization is crucial for patterning the body plan, including determining the positions where limbs emerge [16] [15].

Functional redundancy arises because the 39 Hox genes in vertebrates are organized into four paralogous groups (A, B, C, D) as a result of genome duplication events [17] [18]. Genes within the same paralogous group (e.g., Hoxa1 and Hoxb1) can have highly similar protein sequences and overlapping expression domains, allowing one paralog to partially or fully compensate for the loss of the other in a standard laboratory knockout experiment [19]. This often results in minimal to no observable phenotypic consequences under controlled lab conditions, masking the gene's true biological function [19].

Q2: In a Hoxa2 knockout mouse, why is the limb positioning normal, and what does this teach us about functional redundancy? While Hoxa2 is crucial for patterning structures within the limb (autopod), its knockout does not typically affect the initial positioning of the limb along the body axis [15]. This is because limb positioning is governed by earlier-acting, more 3' Hox genes that specify the axial level of limb initiation [16] [15]. The Hoxa2 knockout phenotype primarily reveals its role in later patterning events, such as determining the identity of second pharyngeal arch derivatives and the formation of the external ear [20].

This teaches us that functional redundancy can be temporal and spatial. The functions of Hox genes in initial limb field specification are distinct from their later roles in patterning the limb bud itself. Knocking out a single Hox gene involved in later stages does not affect the earlier, redundant functions of other Hox genes that have already established the basic body plan.

Q3: What are the best experimental strategies to overcome the challenge of functional redundancy in Hox gene studies? Overcoming functional redundancy requires moving beyond single-gene knockouts in a standard lab setting. The following table summarizes robust experimental approaches:

Table: Strategies to Overcome Functional Redundancy in Hox Gene Research

| Strategy | Description | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Gene Knockouts | Generating double, triple, or cluster-wide knockouts to eliminate all redundant paralogs [15]. | A progressive reduction in the gene dose of paralogous groups (e.g., Hoxa11 & Hoxd11) leads to proportional, severe limb truncations not seen in single mutants [15]. |

| Ecologically Relevant Fitness Assays (OPAs) | Competing mutant animals against wild-type controls in semi-natural enclosures to measure reproductive success and competitive ability [19]. | Reveals cryptic fitness defects (e.g., in territory acquisition and reproduction) that are completely masked in standard lab housing [19]. |

| Targeting cis-Regulatory Elements | Using CRISPR to delete specific enhancers or super-enhancers that control a gene's expression in a specific tissue [20]. | Disrupts precise spatiotemporal expression without affecting the coding sequence, bypassing redundancy at the protein level. For example, deleting the HIRE1 super-enhancer downregulates Hoxa2 and phenocopies its full knockout [20]. |

| Sensitized Genetic Backgrounds | Introducing a mutation into a background that is already haploinsufficient for a related gene or pathway [20]. | A Hoxa2 haploinsufficient background sensitizes the model, allowing a deletion of the HIRE2 enhancer to produce a microtia phenotype [20]. |

Q4: How can I identify the specific enhancers or super-enhancers regulating a Hox gene in my tissue of interest? Identifying functional enhancers requires a multi-assay approach [20]:

- Epigenetic Profiling: Perform ChIP-seq for histone marks associated with active enhancers (e.g., H3K27ac) on your specific cell population (e.g., cranial neural crest cells).

- Chromatin Accessibility: Use ATAC-seq to map open chromatin regions.

- 3D Chromatin Architecture: Employ Hi-C or Promoter-Capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) to identify physical, long-range interactions between these candidate enhancer regions and their target gene promoters.

- Functional Validation: Confirm the role of identified enhancers using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted deletion in animal models, followed by phenotypic and molecular analysis [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: No Phenotype in Single Hox Gene Knockout

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Functional compensation by paralogs. The most common cause is that one or more paralogous genes (e.g., from another Hox cluster) are compensating for the lost function [19] [15].

- Solution: Generate compound mutants. Consult phylogenetic analyses of Hox clusters to identify all paralogs within the same group and create higher-order knockouts [17] [15].

- Protocol: Breeding Strategy for Double Mutants

- Cross single heterozygous parents for two different paralogous genes (e.g., Hoxa11+/- and Hoxd11+/-).

- Intercross the double heterozygous offspring to generate offspring with all possible genotype combinations.

- Genotype the offspring to identify double homozygous mutants. The expected Mendelian ratio for double homozygotes is 1 in 16.

- Analyze the skeletons of double mutants compared to single mutants and wild-types using Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red staining to reveal skeletal patterning defects [15].

Cause 2: The gene's essential function is only revealed under ecological stress. The laboratory environment does not present the challenges (e.g., competition, foraging) needed to expose the phenotype [19].

- Solution: Implement an Organismal Performance Assay (OPA).

- Protocol: Organismal Performance Assay (OPA) Setup

- Founder Population: Establish seminatural enclosures with a mix of mutant and wild-type control mice (e.g., a 50:50 ratio of Hoxb1A1/A1 homozygotes and matched wild-types) [19].

- Environmental Enrichment: Provide limited and distributed resources (food, water, nesting material) and structures for shelter and territory establishment to encourage natural competitive behaviors.

- Monitoring: Track survival, male territorial ownership, and social dominance over an extended period (e.g., multiple months).

- Fitness Measurement: Genotype all offspring born in the enclosures to determine the relative reproductive success of the mutant allele compared to the wild-type allele [19].

Problem: Incomplete Penetrance or Variable Expressivity in Hox Mutants

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete disruption of gene regulation. A traditional knockout that deletes only the coding region may leave intact a network of redundant enhancers that can still drive sufficient expression for partial function [20].

- Solution: Identify and delete critical tissue-specific super-enhancers.

- Protocol: Validating a Super-Enhancer with CRISPR

- Identification: From your Hi-C and ChIP-seq data, pinpoint a candidate super-enhancer region that shows strong, long-range interaction with your Hox gene's promoter [20].

- Guide RNA Design: Design two gRNAs that flank the enhancer region (e.g., the 175 kb HIRE1 region for Hoxa2) to excise the entire element.

- Delivery: Microinject Cas9 mRNA and the two gRNAs into single-cell embryos.

- Analysis: Analyze the resulting founders (F0) for craniofacial and limb phenotypes. Stabilize the mutation by breeding and analyze Hoxa2 and Hoxa3 expression levels via in situ hybridization or RNA-seq in pharyngeal arch CNCCs [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying Hox Collinearity and Redundancy

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise genome editing for generating knockout mice, deleting specific enhancers, and creating point mutations [20]. | Deletion of the HIRE1 super-enhancer to study its role in Hoxa2 regulation [20]. |

| H3K27ac ChIP-seq | Maps active enhancers and super-enhancers genome-wide by identifying regions with histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation [20]. | Identifying 2,232 putative super-enhancers in cranial neural crest cell subpopulations [20]. |

| Promoter-Capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) | Identifies long-range physical interactions between promoters and distal regulatory elements, providing a shortlist of candidate enhancers for a gene of interest [20]. | Discovering that HIRE1 and HIRE2 establish inter-TAD interactions with the Hoxa2 promoter selectively in pharyngeal arch 2 CNCCs [20]. |

| Sensitized Mouse Strain | A strain with a pre-existing, sensitizing mutation (e.g., haploinsufficiency) that makes the system more vulnerable to a second hit [20]. | Using a Hoxa2 haploinsufficient background to reveal the functional role of the HIRE2 enhancer in ear morphogenesis [20]. |

| Polyclonal Antibody against HOXB1 | Used for immunohistochemistry to visualize HOXB1 protein expression and localization in tissues like the hindbrain [19]. | Verifying that the Hoxb1A1 swap allele leads to correct protein expression in rhombomere 4 [19]. |

Essential Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Hox Gene Regulation and Limb Positioning Signaling Cascade

This diagram illustrates the core genetic hierarchy that translates axial positional information into limb bud initiation, a process governed by Hox collinearity.

Diagram Title: Genetic Hierarchy in Limb Initiation

Experimental Workflow for Overcoming Redundancy

This workflow charts a strategic path for investigating Hox gene function when faced with redundant paralogs.

Diagram Title: Strategy to Uncover Redundant Hox Gene Function

Breaking the Redundancy Barrier: Modern Techniques for Multi-Gene and Cluster-Wide Targeting

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is functional redundancy in genetic studies and why is it a problem? Functional redundancy occurs when multiple genes perform similar functions within an organism. When one gene is knocked out, other related genes can compensate for its loss, masking potential phenotypes. This is particularly problematic in studies of clustered gene families, such as Hox genes or protocadherins, where genes within a cluster or across different clusters often serve overlapping roles. This compensation can lead to false negative results in experiments aiming to determine gene function [21] [22] [23].

2. Why use multi-cluster deletion models instead of single-gene knockouts? Single-gene knockouts often fail to reveal the full biological function of genes within clustered families due to functional redundancy. Multi-cluster deletions, which remove entire genomic segments containing multiple genes, overcome this compensation. For example, while single Hox gene mutants may show mild phenotypes, simultaneous deletion of multiple Hox clusters in zebrafish leads to severe defects in pectoral fin development and heart formation, unmasking their critical collective functions [21] [22] [24].

3. What are the key considerations when designing gRNAs for large genomic deletions? Designing effective guide RNAs (gRNAs) is critical for successful multi-cluster deletions. Key considerations include:

- Target Selection: gRNAs should be designed to flank the entire genomic region targeted for deletion. In a zebrafish hoxbb cluster deletion, one gRNA was designed before the initiation codon of

hoxb8band another after the stop codon ofhoxb1b, successfully deleting a 25.5 kb region [21]. - Specificity: Use bioinformatics tools like ZIFIT, CRISPOR, or E-CRISP to predict potential off-target sites and minimize the risk of unintended mutations [25] [21].

- Validation: Always sequence potential off-target sites to confirm specificity. Research deleting the hoxbb cluster sequenced 16 potential off-target sites and found no evidence of off-target mutagenesis [21].

4. How can I validate successful multi-cluster deletion and its functional consequences? A multi-step validation approach is essential:

- Genotyping: Use PCR with primers outside the deletion boundaries to confirm the absence of the targeted region. For the hoxbb cluster deletion, a specific primer pair (F1/R2) was used to amplify across the deletion junction [21].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Conduct detailed morphological examinations. In hox cluster studies, this included analyzing pericardial edema, heart looping, and fin development [21] [22].

- Molecular Confirmation: Perform in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry to check for loss of target gene expression. For example, loss of

tbx5aexpression confirmed the functional impact of hoxba/hoxbb cluster deletions in zebrafish [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Low Editing Efficiency

- Problem: Insufficient deletion of the target genomic region.

- Solutions:

- Verify gRNA Design: Ensure gRNAs target unique genomic sequences and have high on-target activity scores. Use specialized design tools [26].

- Optimize Delivery Method: Different cell types or embryos may require optimization of delivery methods (e.g., electroporation, microinjection). Consider using Cas9 protein instead of mRNA for faster activity [26].

- Check Component Quality: Verify the integrity and concentration of your gRNAs and Cas9 nuclease. Degraded components will reduce efficiency.

Off-Target Effects

- Problem: Unintended mutations at genomic sites with similar sequences to your gRNA targets.

- Solutions:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Engineered Cas9 versions with improved specificity are available.

- Bioinformatic Screening: Utilize tools like CRISPOR to design gRNAs with minimal off-target potential [25] [21].

- Empirical Validation: Sequence the top predicted off-target sites in your final model to rule out unintended mutations. Researchers routinely validate this by sequencing potential off-target loci [21].

Mosaicism in Founder Generation

- Problem: The presence of both edited and unedited cells in the same organism (F0 generation).

- Solutions:

- Early Delivery: Inject CRISPR components at the earliest possible developmental stage (e.g., single-cell stage in zebrafish) [21].

- Use of Cas9 Protein: Direct delivery of Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes can accelerate editing before cell division.

- Generational Selection: Breed F0 animals and screen F1 progeny to establish stable, non-mosaic lines.

Cell Toxicity and Low Survival

- Problem: High levels of cell death or poor viability following CRISPR editing.

- Solutions:

- Titrate Component Concentration: Use the lowest effective concentration of Cas9 and gRNAs. High concentrations can be toxic [26].

- Optimize Delivery Conditions: For electroporation, optimize voltage and pulse duration; for microinjection, optimize injection volume and pressure.

Quantitative Data from Key Studies

Table 1: Phenotypic Outcomes of Hox Cluster Deletions in Zebrafish

| Deleted Clusters | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Other Phenotypes | Survival/Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxbb -/- [21] | Heart failure, AV regurgitation, trabecular dysplasia | Pericardial edema, heart looping failure | Lethal by 11 dpf |

| hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- [22] | Severe shortening of endoskeletal disc and fin-fold | Reduced shha expression in fin buds |

Not specified |

| hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- [24] | Complete absence of pectoral fins | Loss of tbx5a expression in fin field |

Embryonic lethal ~5 dpf |

Table 2: Efficiency of Multi-Cluster Deletion Strategies

| Model System | Target Locus | Deletion Size | Efficiency | Key Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish [21] | hoxbb cluster | 25.5 kb | ~80% (F0) | PCR with junction primers, sequencing |

| Mouse [23] | Pcdh α, β, γ clusters | ~1 Mb | Not specified | PCR, phenotypic analysis |

| Zebrafish [22] | hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda | Multiple clusters | Mendelian ratio (adults) | Genotyping PCR, morphology |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing and Generating Multi-Cluster Deletions in Zebrafish

Step 1: Target Identification and gRNA Design

- Identify the genomic boundaries of the target cluster(s). For the hoxbb cluster, the 25.5 kb region from

hoxb8btohoxb1bwas targeted [21]. - Design two gRNAs flanking the region to be deleted using bioinformatic tools (e.g., ZIFIT, CRISPOR).

- Select gRNAs with high on-target scores and minimal predicted off-target effects.

Step 2: Synthesis of CRISPR Components

- Synthesize gRNAs through in vitro transcription or commercial synthesis.

- Prepare Cas9 mRNA or obtain Cas9 protein. For zebrafish embryos, mRNA is commonly used.

Step 3: Embryo Microinjection

- Inject a mixture of both gRNAs and Cas9 mRNA/protein into single-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Standard concentrations: 25-50 pg per gRNA and 150-300 pg Cas9 mRNA per embryo.

Step 4: Genotyping and Founder Identification

- At 24-48 hours post-fertilization, extract genomic DNA from individual embryos.

- Perform PCR with three primer sets:

- Internal control primers (within deletion region)

- Wild-type allele primers (flanking one side)

- Mutant allele primers (spanning deletion junction)

- Sequence PCR products to confirm precise deletion boundaries.

Step 5: Off-Target Validation

- Use prediction tools to identify potential off-target sites.

- Design primers for top 10-20 potential off-target sites.

- Amplify and sequence these regions from mutant embryos to confirm absence of off-target mutations.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Multi-Cluster Deletions

Step 1: Phenotypic Characterization

- For zebrafish studies, document morphological changes at key developmental stages (e.g., 3 dpf, 5 dpf).

- Specifically examine organs or structures known to be influenced by the target genes.

- For Hox cluster mutants, analyze heart development, fin formation, and body axis patterning [21] [22].

Step 2: Molecular Phenotyping via In Situ Hybridization

- Design RNA probes for key marker genes.

- Fix embryos at appropriate developmental stages.

- Process embryos for whole-mount in situ hybridization to visualize gene expression patterns.

- For Hox cluster mutants, examine expression of downstream targets like

shhaortbx5a[22] [24].

Step 3: Confocal Imaging for Detailed Morphological Analysis

- Cross mutant lines with transgenic reporters labeling specific tissues (e.g.,

myl7:EGFPfor myocardium). - Image live or fixed specimens using confocal microscopy.

- Quantify morphological parameters (e.g., looping angle in heart development) [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Multi-Cluster Deletion Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Design Tools (ZIFIT, CRISPOR, E-CRISP) [25] [21] | gRNA design and off-target prediction | Identifying optimal gRNA targets flanking gene clusters | Prioritize gRNAs with high specificity scores |

| Cas9 Nuclease (standard or high-fidelity) | DNA endonuclease for creating double-strand breaks | Microinjection into zebrafish embryos or transfection into ES cells | High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects |

| In Vitro Transcription Kits | Synthesis of gRNAs and Cas9 mRNA | Generating CRISPR components for embryo injection | Use high-quality kits to ensure intact RNA |

| Transgenic Reporter Lines [21] | Visualizing specific tissues or cell types | Crossing with mutants to analyze phenotypic consequences | Available for various tissues (e.g., myocardium, endocardium) |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization Reagents | Detecting spatial gene expression patterns | Analyzing expression of downstream target genes | RNA probes must be specific and high-quality |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Multi-Cluster Deletion Models

Hox Gene Function in Zebrafish Development

FAQ: Why did our single hox cluster mutant not show a phenotype, and what is the solution?

Question: We generated a mutant for a single Hox cluster (e.g., hoxba) but observed only mild or no defects in the structure we were studying (e.g., the pectoral fin). What could explain this, and what is the recommended genetic approach?

Answer: This is a classic symptom of functional redundancy between Hox clusters. Due to evolutionary duplication events, Hox genes within paralogous clusters often have overlapping functions and expression domains. The absence of a severe phenotype in a single mutant suggests that other Hox genes are compensating for the loss.

- Solution: Implement a cluster-wide double mutant strategy. As demonstrated in zebrafish, deleting the

hoxbacluster alone only caused mild pectoral fin abnormalities, while the simultaneous deletion of bothhoxbaand its paralogoushoxbbcluster resulted in a complete absence of pectoral fins [27] [24] [28]. This indicates that these two clusters derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster work cooperatively. - Experimental Design Tip: Always consider the evolutionary history of your target Hox genes. In zebrafish, which have seven Hox clusters due to teleost-specific duplication, you may need to target multiple derived clusters (e.g.,

hoxbaandhoxbb) to reveal the full function of the ancestral vertebrate gene network [27] [29].

FAQ: How do we confirm that a Hox gene mutation affects the initial positioning of an appendage versus its later patterning?

Question: Our Hox double mutant shows appendage defects. How can we determine if the defect is in the initial specification of the appendage field or in its subsequent growth and patterning?

Answer: This requires analyzing early molecular markers and the competence of the tissue to key signaling pathways.

- Investigate Early Marker Expression: Examine the expression of key transcription factors that initiate appendage development. In the

hoxba;hoxbbzebrafish double mutants, the expression oftbx5a—a critical gene for inducing pectoral fin buds—was nearly undetectable in the lateral plate mesoderm at 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf) [27] [24]. This failure of induction points to a loss of pectoral fin precursor cells and a defect in initial positioning. - Test Pathway Competence: Assess the tissue's ability to respond to essential morphogens. The

hoxba;hoxbbmutant tissue lost its competence to respond to retinoic acid, a key signal that normally inducestbx5aexpression [27]. This confirms that the Hox genes are required upstream to establish a responsive appendage field.

Table 1: Key Molecular Markers for Distinguishing Limb Positioning vs. Patterning Defects

| Experimental Readout | Indicates Problem with Initial Positioning | Indicates Problem with Later Patterning |

|---|---|---|

| Expression of early initiators (e.g., Tbx5) | Absent or significantly reduced at early bud stages [27] [24] | Present at normal levels |

| Tissue competence to key signals (e.g., Retinoic Acid) | Lost [27] | Largely intact |

| Expression of later patterning genes (e.g., Shh) | May be absent due to failed initiation | Abnormal expression domains, indicating disrupted patterning [30] |

FAQ: Which specific genes within a Hox cluster are most critical for appendage positioning?

Question: Once a phenotype is observed in a cluster mutant, how can we pinpoint the specific Hox gene(s) responsible from the many located within the deleted region?

Answer: A combination of genomic deletion and targeted frameshift mutations is required to identify the pivotal genes.

- Strategy: After identifying that the

hoxba;hoxbbdouble cluster deletion causes pectoral fin loss, researchers used finer-scale mutagenesis to implicatehoxb4a,hoxb5a, andhoxb5bas the key players [27]. - Important Nuance: Frameshift mutations in these individual genes did not fully recapitulate the strong cluster-deletion phenotype, suggesting they act cooperatively. However, deletion mutants that remove the genomic loci for

hoxb5aandhoxb5bdid cause the absence of pectoral fins, albeit with low penetrance [27]. This highlights that some functional redundancy exists even at the gene level and that regulatory elements lost in genomic deletions may also contribute to the phenotype.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Hox Gene Functional Redundancy

| Problem / Challenge | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No phenotype in a single Hox mutant. | Functional redundancy from paralogous genes in other clusters. | Generate compound mutants for paralogous clusters (e.g., hoxba;hoxbb). |

| Weak or incomplete penetrance phenotype. | Incomplete redundancy; a threshold level of Hox function may remain. | Create higher-order mutants (e.g., triple clusters) or combine with other pathway mutants [30]. |

| Unclear if the gene acts in positioning or patterning. | Analysis focused on late-stage morphology. | Analyze early molecular markers (e.g., tbx5a) and tissue competence (e.g., to RA) [27]. |

| Difficulty identifying the key gene within a cluster. | Cooperative action of multiple genes in the cluster. | Use a combination of cluster-wide deletion and finer-scale gene-specific mutations [27]. |

Experimental Protocol: Generating and Validating Cluster-Wide Hox Deletions

This protocol summarizes the key methodology from the cited research on generating hoxba;hoxbb double mutants [27] [24] [28].

Step 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Target Design

- Design multiple single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that flank the entire genomic region of the target Hox cluster. The goal is to create a large deletion that excises the entire cluster.

- Control: Always include wild-type siblings from the same clutch as controls for all phenotypic analyses.

Step 2: Zebrafish Microinjection and Founder (F0) Generation

- Co-inject the sgRNAs and Cas9 protein into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Raise the injected embryos (F0 generation) to adulthood. These are potential founders for the cluster deletion.

Step 3: Identifying and Establishing Stable Mutant Lines

- Outcross F0 founders to wild-type fish. Screen the F1 progeny for the presence of the large cluster deletion using PCR with primers that bind outside the deleted region. A successful deletion will result in a smaller PCR product.

- Establish stable heterozygous mutant lines for each cluster (e.g.,

hoxba+/−andhoxbb+/−).

Step 4: Generating Compound Cluster Mutants

- Intercross the single cluster heterozygous mutants to generate double heterozygous animals (

hoxba+/−;hoxbb+/−). - Intercross these double heterozygotes to obtain embryos with all possible genotypic combinations, including the double homozygous mutants (

hoxba−/−;hoxbb−/−). The expected Mendelian ratio for double homozygotes is 1/16 (6.25%).

Step 5: Phenotypic and Molecular Validation

- Morphological Analysis: Visually inspect live embryos at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf) for the presence or absence of pectoral fins.

- In Situ Hybridization: At key developmental stages (e.g., 30 hpf for initial bud formation), perform whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) for

tbx5ato visualize the formation of the pectoral fin field [27]. - Genotype-Phenotype Correlation: After analysis, genotype individual embryos to definitively link the absence of

tbx5aexpression and the finless morphology to thehoxba;hoxbbdouble homozygous genotype.

Pathway Diagram: Hox-Tbx5 Regulatory Axis in Limb Positioning

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and signaling pathway between Hox genes and the initiation of appendage development, as revealed by the cluster mutant studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Cluster Deletion Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example from Cited Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | To generate large, precise deletions of entire Hox clusters. | Used to create seven distinct hox cluster-deficient mutants in zebrafish [27]. |

| sgRNAs Flanking Hox Clusters | To guide the Cas9 nuclease to the start and end of a cluster, enabling its excision. | sgRNAs designed to delete the hoxba and hoxbb genomic loci [27] [24]. |

| tbx5a RNA Probe (for WISH) | To visualize and quantify the initiation of pectoral fin buds; a key molecular readout. | Used to show tbx5a expression is absent in hoxba;hoxbb mutants [27] [24]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | A chemical tool to test the competence of the lateral plate mesoderm to initiate limb-specific gene expression. | Used to demonstrate that hoxba;hoxbb mutants lose competence to respond to RA [27]. |

| shha RNA Probe (for WISH) | To assess later patterning events after the initial bud has formed. | Used in other cluster mutants (e.g., hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda) to show disrupted patterning [30]. |

Hox genes are master regulators of embryonic development, specifying positional identity along the anterior-posterior body axis in animals [2]. Their protein products function as transcription factors that bind DNA through a conserved homeodomain motif [2]. A significant challenge in developmental genetics lies in understanding how Hox proteins achieve specific regulatory outcomes despite their highly similar DNA-binding domains—a phenomenon known as the "Hox Specificity Paradox" [31].

The 39 human HOX genes are organized into four clusters (A-D) on different chromosomes, a structure that arose through duplication and divergence from a primordial homeobox gene [32]. A key feature of Hox gene organization is colinearity—the correspondence between the genomic order of genes within clusters and their spatial and temporal expression patterns during development [33] [32]. This complex regulation makes Hox genes particularly challenging to study, as functional redundancy between paralogs can mask the effects of individual gene perturbations [1] [32].

The Regulatory Landscape Concept

Hox gene expression is controlled by extensive regulatory landscapes containing enhancers that can be located hundreds of kilobases away from their target genes [34] [35] [36]. Two critical domains flanking the HoxD cluster have been extensively characterized:

- 3DOM: A large regulatory domain located 3' to the HoxD cluster controlling proximal limb and fin development [34] [36]

- 5DOM: A regulatory domain located 5' to the HoxD cluster essential for digit (autopod) development in tetrapods and cloacal formation in vertebrates [34] [36]

Recent research reveals that these regulatory landscapes can be multifunctional, with ancestral roles being co-opted for novel structures during evolution. For example, the 5DOM landscape controlling digit development in tetrapods appears to have been co-opted from an ancestral regulatory program governing cloacal development [34] [36].

Experimental Approaches: Deleting Enhancer Domains

Rationale for Landscape Deletion

Individual Hox genes often exhibit functional redundancy, where paralogous genes can compensate for each other's loss [1] [17]. This redundancy makes it difficult to disrupt Hox function through single-gene knockouts. However, deleting entire regulatory landscapes that control multiple Hox genes simultaneously can overcome this limitation by disrupting the coordinated expression of gene subsets [34].

This approach is particularly effective because:

- Regulatory landscapes control multiple genes in a coordinated manner

- It circumvents compensation by paralogous genes

- It can reveal ancestral functions conserved through evolution

CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Deletion of 3DOM and 5DOM

Protocol: Generating Large Regulatory Deletions in Zebrafish

Note: Similar approaches have been successfully applied in mouse models [34]

Design gRNA Targets: Design multiple guide RNAs flanking the regulatory domain to be deleted

Microinjection: Co-inject Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs into single-cell zebrafish embryos

Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to identify founders carrying deletions

Establish Stable Lines: Outcross F1 fish with deletions to establish stable mutant lines

Phenotypic Analysis:

Expected Results:

- Del(3DOM) mutants: Complete loss of hoxd4a and hoxd10a expression in pectoral fin buds [34]

- Del(5DOM) mutants: Minimal effect on fin development but complete abrogation of hoxd expression in the developing cloaca [34] [36]

Experimental workflow for generating regulatory domain deletions using CRISPR-Cas9

Validation Methods

Histone Modification Profiling (CUT&RUN)

- Apply CUT&RUN assay to posterior trunk tissue (where hox genes are active) [34]

- Use dissected heads as negative controls [34]

- Probe for H3K27ac (active enhancers) and H3K27me3 (repressive marks) [34]

- Compare signal intensity in mutant vs. wild-type embryos

ATAC-seq Assay

- Assess chromatin accessibility in regulatory landscapes [36]

- Identify changes in open chromatin regions following domain deletion

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH)

- Analyze spatiotemporal expression patterns of hoxd genes [34]

- Compare expression in Del(3DOM), Del(5DOM), and wild-type embryos

- Focus on fin buds and cloacal region

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Incomplete Penetrance of Phenotypes

Problem: Variable or incomplete phenotypic penetrance following domain deletion

Solutions:

- Verify deletion size and boundaries by PCR and sequencing

- Check for potential compensatory regulation by other Hox clusters

- Analyze multiple independent mutant lines to distinguish specific effects from background mutations

- Consider species-specific differences: Zebrafish 5DOM deletion affects cloaca but not fins, while mouse 5DOM deletion disrupts digit development [34] [36]

Functional Redundancy Persists

Problem: Despite domain deletion, minimal phenotypic consequences are observed due to persistent redundancy

Solutions:

- Combine regulatory domain deletions with individual Hox gene mutations

- Generate compound mutants targeting multiple regulatory landscapes

- Consider that some regulatory landscapes may have tissue-specific functions (e.g., 5DOM's primary role in cloacal vs. limb development) [36]

Off-Target Effects

Problem: CRISPR-mediated deletions cause unintended genomic alterations

Solutions:

- Use multiple guide RNAs to minimize off-target cutting

- Sequence potential off-target sites predicted by bioinformatics tools

- Backcross mutants to clean genetic background

- Generate multiple independent lines to confirm phenotype specificity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why delete entire regulatory domains rather than individual enhancers?

A: Individual enhancers often work redundantly within larger landscapes. Hox proteins achieve specificity through binding to clusters of low-affinity sites rather than single high-affinity sites [31]. Deleting entire domains disrupts this coordinated regulation and more effectively abrogates gene expression.

Q2: How do I determine the boundaries of regulatory domains like 3DOM and 5DOM?

A: Domain boundaries can be identified through:

- Chromatin conformation capture (3C, Hi-C) identifying topologically associating domains (TADs) [34]

- Conservation analysis across species [34]

- CTCF binding sites that mark domain boundaries [34]

- Histone modification patterns (H3K27ac) marking active regulatory regions [34]

Q3: What explains the different phenotypic outcomes of 5DOM deletion in zebrafish versus mice?

A: This difference reflects evolutionary co-option. The 5DOM regulatory landscape appears to have an ancestral role in cloacal development conserved across vertebrates [34] [36]. In tetrapods, this landscape was co-opted for digit development, explaining why zebrafish 5DOM deletion affects cloaca but not fins, while mouse 5DOM deletion disrupts digit formation [34].

Q4: How can I assess the success of regulatory domain deletion?

A: Use multiple validation methods:

- PCR across deletion junctions with sequencing confirmation [34]

- Quantitative PCR to confirm copy number loss

- RNA in situ hybridization to assess gene expression changes [34]

- Histone modification profiling to confirm loss of regulatory activity [34]

Table 1: Phenotypic Consequences of Regulatory Domain Deletions in Zebrafish and Mouse

| Domain Deleted | Species | Hox Gene Expression Changes | Morphological Phenotypes | Conserved Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DOM | Zebrafish | Complete loss of hoxd4a, hoxd10a in fin buds [34] | Disrupted proximal fin development [34] | Proximal appendage patterning [34] |

| 3DOM | Mouse | Loss of proximal Hoxd expression [34] | Disrupted stylopod/zeugopod formation [34] | Proximal appendage patterning [34] |

| 5DOM | Zebrafish | Loss of hoxd13a in cloaca; minimal effect in fins [34] [36] | Severe cloacal malformations [34] [36] | Cloacal development (ancestral) [34] [36] |

| 5DOM | Mouse | Loss of distal Hoxd expression [34] | Digit agenesis [34] | Digit development (derived) [34] [36] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Regulatory Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Genome editing | Precise deletion of large genomic regions | Generate Del(3DOM) and Del(5DOM) mutants [34] |

| CUT&RUN Assay | Histone modification profiling | Mapping active enhancers (H3K27ac) and repressed regions (H3K27me3) [34] | Validate regulatory function of deleted domains [34] |

| ATAC-seq | Chromatin accessibility | Identify open chromatin regions | Map accessible chromatin in regulatory landscapes [36] |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization | Spatial gene expression | Visualize spatiotemporal expression patterns | Analyze hox gene expression in mutants vs wild-type [34] |

| Zebrafish Model | Vertebrate development | External development, genetic tractability | Study fin and cloacal development [34] [36] |

| Mouse Model | Mammalian development | Relevant to human biology, genetic tools | Study digit and limb development [34] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Evolutionary Insights from Regulatory Landscape Manipulation

Comparative studies of regulatory domain function across species provide powerful insights into evolutionary mechanisms. The finding that 5DOM has conserved functions in cloacal development but divergent roles in appendage patterning illustrates how existing regulatory architectures can be co-opted for novel structures during evolution [34] [36].

Evolutionary co-option of the 5DOM regulatory landscape from ancestral cloacal development to derived digit patterning in tetrapods

Beyond 3DOM/5DOM: Expanding the Regulatory Toolkit

While 3DOM and 5DOM represent well-characterized examples, Hox gene regulation involves additional layers of complexity:

- Post-transcriptional regulation: Noncoding RNAs, microRNAs, and RNA processing contribute to Hox output [35]

- Chromatin dynamics: Progressive opening of Hox chromatin during development enables temporal collinearity [33]

- Intercellular signaling: BMP/Wnt gradients coordinate Hox expression across tissues [33]

Therapeutic Implications

Understanding Hox regulatory mechanisms has potential clinical applications:

- Cancer therapeutics: HOX genes are implicated in leukemias and other malignancies [32]

- Congenital disorders: Mutations in HOXA13 and HOXD13 cause limb malformations [32]

- Regenerative medicine: Manipulating Hox codes could potentially guide tissue regeneration

The strategies described here for targeting regulatory landscapes provide powerful approaches to overcome the challenges of Hox gene redundancy. By moving beyond single-gene manipulations to target integrated regulatory architectures, researchers can achieve more comprehensive disruption of Hox function, revealing deeper insights into their roles in development, evolution, and disease.

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q: We generated single hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b knockout zebrafish lines but observe minimal phenotypic consequences. What is the most likely explanation and how should we proceed?

- A: This is a classic symptom of functional redundancy within the Hox gene family. Paralogous genes (like hoxb5a and hoxb5b) often perform similar functions, allowing one gene to compensate for the loss of another. To reveal their true biological roles, you must generate combinatorial knockouts. Proceed by crossing your single knockout lines to create double (e.g., hoxb5a/b5b) and finally triple (hoxb4a/b5a/b5b) mutants.

Q: In our triple mutant embryos, we observe a severe defect in pectoral fin development. What are the first steps to validate this is a specific phenotype and not a general developmental delay?

- A:

- Staging: Confirm the embryo stage using non-fin specific morphological criteria (e.g., somite count, eye/otic vesicle development).

- Marker Analysis: Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) for early fin bud markers (e.g., tbx5, fgf10a). A specific defect will show absent or abnormal expression domains, while a general delay would show uniformly reduced but correctly patterned expression.

- Histology: Process mutants and siblings for histological sectioning to examine fin bud mesenchyme and ectodermal fold architecture.

- A:

Q: Our genotyping of F2 progeny from double heterozygous crosses does not yield the expected Mendelian ratios for the triple knockout genotype. What could be causing this?

- A: A deviation from expected ratios, especially a lack of triple mutants, suggests synthetic lethality. The combined loss of these Hox genes is likely causing an early embryonic defect that is lethal before you can genotype. To address this:

- Increase sample size to ensure you are not missing rare genotypes.

- Genotype embryos at earlier developmental stages (e.g., shield stage) to see if the triple genotype is present but then lost.

- Analyze maternal zygotic mutants if using zebrafish, as maternal transcript contribution can mask early zygotic phenotypes.

- A: A deviation from expected ratios, especially a lack of triple mutants, suggests synthetic lethality. The combined loss of these Hox genes is likely causing an early embryonic defect that is lethal before you can genotype. To address this:

Q: When performing RNA-Seq on triple mutant embryos, what is the best control to account for background genetic variation?

- A: The optimal control is siblings from the same clutch that are wild-type or heterozygous for the mutations. This controls for genetic background and environmental factors. Pooling multiple clutch siblings for each group (mutant vs. control) is recommended to increase statistical power.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generation of Combinatorial Hox Knockouts in Zebrafish using CRISPR-Cas9

- Design gRNAs: Design and synthesize single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting exonic regions of hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b with high on-target efficiency scores.

- Microinjection: Co-inject Cas9 protein and a pool of all three sgRNAs into single-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Raise Founders (F0): Raise injected embryos to adulthood. These are potential mosaic founders.

- Outcross and Identify Germline Transmission: Outcross F0 fish to wild-types. Screen their progeny (F1) by PCR and sequencing for indel mutations. Select F1 fish carrying frameshift mutations in each gene.

- Establish Stable Lines: Raise positive F1 fish and genotype to establish stable heterozygous lines for each gene.

- Generate Multi-Knockout Lines: Cross single heterozygotes to generate double heterozygous fish. Intercross double heterozygotes to generate double knockouts. Repeat the process, crossing double mutants to introduce the third mutation.

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Analysis via Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH)

- Fixation: Fix mutant and control embryos at desired stages in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C.

- Probe Synthesis: Generate digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNA probes for genes of interest (e.g., hoxb4a, hoxb5a, tbx5, shh).

- Hybridization: Rehydrate embryos, perform proteinase K digestion, and hybridize with the DIG-labeled probe overnight at 65-70°C.

- Immunodetection: Wash stringently and incubate with an anti-DIG antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP).

- Color Reaction: Develop color using NBT/BCIP substrate. Stop the reaction, post-fix, and clear embryos in glycerol for imaging.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Mendelian Ratios from Intercross of hoxb5a+/-; hoxb5b+/- Double Heterozygotes

| Genotype | Expected Frequency | Observed Frequency (n=200) | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 1/16 | 1/16 (6.3%) | Normal |

| hoxb5a-/- | 1/16 | 1/16 (6.3%) | Normal |

| hoxb5b-/- | 1/16 | 1/16 (6.3%) | Normal |

| hoxb5a-/-; hoxb5b-/- | 1/16 | 0/16 (0%) | Lethal |

Table 2: Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis of Hox Gene Expression in Single and Double Mutants (48 hpf)

| Genotype | hoxb4a (Relative Exp.) | hoxb5a (Relative Exp.) | hoxb5b (Relative Exp.) | tbx5 (Relative Exp.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 1.00 ± 0.15 | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 1.00 ± 0.10 |

| hoxb5a-/- | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 1.85 ± 0.20 | 0.98 ± 0.12 |

| hoxb5b-/- | 1.10 ± 0.09 | 1.92 ± 0.22 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 1.05 ± 0.11 |

| hoxb5a-/-; hoxb5b-/- | 1.78 ± 0.19 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.08 |

Mandatory Visualization

Hox Redundancy Breakdown Logic

Combinatorial KO Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted gene knockout via induction of double-strand breaks in genomic DNA. |

| Antisense RNA Probes (DIG-labeled) | Detection of specific mRNA transcripts in fixed samples via in situ hybridization. |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Immunological detection of hybridized RNA probes for colorimetric visualization. |

| NBT/BCIP | Chromogenic substrate for Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), producing a purple precipitate. |

| T7/T3 RNA Polymerase | In vitro transcription for generating high-quality antisense RNA probes. |

| Tricaine (MS-222) | Anesthetic for immobilizing zebrafish embryos and adults for imaging and procedures. |

Solving the No-Phenotype Problem: Assessing Penetrance and Environmental Context in Hox Studies

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Hox Cluster Deletion Analysis

FAQ 1: Why do my Hox cluster deletion mutants show variable or incomplete penetrance of phenotypes, and how can I quantify this?

Variable penetrance in Hox cluster deletions arises from several factors. Genetic background effects significantly modulate expressivity, as demonstrated in mice where the same Hoxb6 mutation produced different skeletal anomaly frequencies on C57BL/6 versus 129SvEv backgrounds [37]. Functional redundancy between paralogous Hox genes can compensate for missing cluster functions—studies reveal paralogs like HOXA6 and HOXB6 have unique, non-redundant roles despite their similarity [38]. Remote enhancer locations also contribute; in transgenic mice, a human HOXD cluster rescued axial defects but not limb defects because limb-specific enhancers reside outside the cloned cluster region [39].

Quantification Strategy:

- Systematic Phenotype Categorization: Classify mutants into severity groups (e.g., Group A: complete paralysis, Group B: distal paralysis, Group C: normal locomotion) based on standardized functional and morphological assessments [40].

- Genetic Background Control: Conduct repeated backcrossing (8+ generations) into isogenic backgrounds and compare intercross siblings to isolate background effects [37].

- Expressivity Scoring: Develop quantitative scoring systems for skeletal phenotypes (e.g., vertebral transformations, digit malformations) and calculate penetration percentages across large cohorts [37].

FAQ 2: What essential controls and replication strategies are needed for interpreting Hox cluster deletion experiments?

Proper experimental design must account for the complex regulatory landscape and potential compensatory mechanisms. Always include these controls:

- Complete vs. Subset Deletions: Compare full cluster deletions with smaller internal deletions to identify threshold effects and gene-specific contributions [40].

- Cis-Regulatory Rescue: Test whether reintroduction of suspected remote enhancers restores specific expression domains [39].

- Neighboring Gene Monitoring: Include assays for genes adjacent to clusters (e.g., Evx2), as their misexpression can cause severe phenotypes misinterpreted as cluster deletion effects [40].

Replication Guidelines:

- Sample Sizes: Given the variability, analyze minimum 10-15 homozygous mutants per genotype across multiple litters [37].

- Positional Controls: Use the same reporter gene (e.g., lacZ) targeted to different cluster positions to monitor remaining regulatory influences after deletion [39].

- Temporal Analysis: Collect data at multiple developmental stages, as phenotypes can manifest progressively [40].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Phenotype Severity Classification in HoxD Cluster Deletion Mutants [40]

| Deletion Group | Genotype Examples | Locomotion Phenotype | Key Molecular Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (Most Severe) | Del(10–13), Del(9–13), Del(i–13) | Complete hindlimb paralysis | Hoxd10 loss, Evx2 ectopic expression |

| Group B (Moderate) | Del(8–13), Del(10–13); Evx2stop | Distal leg paralysis, clubfoot-like | Hoxd10 loss alone, Evx2 intact |

| Group C (Mild/Normal) | Del(11–13), Del(9) | Normal locomotion and posture | Hoxd10 function preserved |

Table 2: Genetic Background Effects on Hoxb6 Mutant Skeletal Phenotypes [37]

| Phenotypic Feature | Penetrance in C57BL/6 Background | Penetrance in 129S6/SvEvTac Background | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rib fusions | 33.3% | 75.0% | p < 0.05 |

| Bifid ribs | 0.0% | 37.5% | p < 0.05 |

| Vertebral transformations | 66.7% | 87.5% | Not significant |

| Unilateral manifestations | Common | Rare | Not reported |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Phenotypic Scoring for Hox Cluster Deletion Neurological Defects