Blue Light vs. Red Light Optogenetics: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a systematic comparison of blue-light and red-light optogenetic systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Blue Light vs. Red Light Optogenetics: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of blue-light and red-light optogenetic systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of light-tissue interaction, including the superior tissue penetration and reduced scattering of red light. The review details the core optogenetic tools, such as channelrhodopsins and phytochromes, and their specific methodological applications in neuroscience and therapeutic development. It addresses key experimental challenges like cross-talk and phototoxicity, offering optimization strategies. Finally, it presents a rigorous comparative analysis of system performance, validating the distinct advantages and optimal use cases for each wavelength to guide tool selection for both basic research and clinical translation.

The Physics of Light in Biology: Why Wavelength Matters

Optogenetics has revolutionized neuroscience and biology by enabling precise, cell-specific control of cellular functions with light. However, a significant obstacle hinders its application, particularly for deep tissue structures: the fundamental challenge of light scattering and absorption in biological tissues. Biological tissues contain various structures and molecules that readily scatter, absorb, or reflect visible light, dramatically reducing light penetration and limiting the precision and effectiveness of optogenetic manipulations [1]. This scattering problem becomes especially critical when considering the size of major research models like the rodent brain, where targeting subcortical structures requires light to traverse significant tissue depths [1].

The severity of this challenge is wavelength-dependent. Shorter wavelengths, such as blue light, experience substantially more scattering and absorption compared to longer wavelengths like red and near-infrared (NIR) light [1] [2]. This physical reality has driven a fundamental comparison between blue-light and red-light optogenetic systems, not merely as a matter of spectral preference but as a crucial determinant of experimental success in non-superficial applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these systems, focusing on their performance in overcoming tissue optical barriers, supported by experimental data and the latest technological solutions.

The Physics of Light-Tissue Interactions

Understanding the differential performance of blue and red light requires an examination of the core physical phenomena involved.

Scattering: The Dominant Factor

- Mechanism: Scattering occurs when light encounters variations in the refractive index at interfaces like liquid-lipid membranes [1].

- Wavelength Dependence: Scattering is strongly inversely proportional to wavelength, meaning shorter wavelengths scatter more [1]. Consequently, blue light (~470 nm) experiences significantly more scattering than red light (~630 nm).

- Tissue Variability: The degree of scattering varies by brain structure. Areas with high cell density scatter more light than regions dominated by axons and dendrites. Myelinated axons and directionally organized fibers also increase scattering [1].

Absorption: The Role of Chromophores

- Key Absorbers: Skin melanin and blood hemoglobin are major absorbers of visible light [1].

- Spectral Preference: Hemoglobin has significantly higher absorption for blue light than for red light [1]. Melanin also dramatically reduces blue light penetration.

- Other Absorbers: Fat exhibits relatively similar absorption across blue and red wavelengths, while water primarily absorbs at longer NIR wavelengths beyond those typically used in optogenetics [1].

The Combined Effect: Penetration Depth

The combined effects of scattering and absorption result in stark differences in practical penetration depth. In skin, red light penetration reaches 4-5 mm, whereas blue light penetration is limited to approximately 1 mm [1]. Considering a mouse's scalp is 0.3-0.6 mm thick, this difference is physiologically significant for in vivo studies [1].

Table 1: Physical Properties and Tissue Interaction of Blue vs. Red Light in Optogenetics

| Physical Property | Blue Light (~470 nm) | Red Light (>630 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Scattering | High | Low |

| Hemoglobin Absorption | High | Low |

| Melanin Absorption | High | Low |

| Approximate Penetration Depth in Skin | ~1 mm [1] | 4-5 mm [1] |

| Representative Scattering Mean Free Path (MFP) in Brain | ~10s of micrometers [3] | Longer than blue light (specific value N/A) |

| Phototoxicity Potential | Higher | Lower |

Quantitative Comparison of Blue vs. Red Light Performance

Experimental data clearly demonstrates the performance gap between blue and red light in biological tissues.

Direct Penetration and Focus Quality

Wavefront shaping experiments through biological tissues like brain slices and skulls quantify the challenge. After corrective modulation, the achieved focus through a 500-μm thick brain slice can reach a Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of less than 4 μm with a Peak-to-Background Ratio (PBR) of about 200 for a 589 nm laser [3]. This represents a dramatic improvement over the scrambled speckle pattern of unmodulated light. However, performance continuously decreases with increasing tissue thickness due to escalating scattering and absorption [3]. When using denser intact mouse skulls as the scattering medium, the maximum average PBR through one piece of skull drops to about 45, highlighting the severe scattering induced by bone [3].

Functional Outcomes in Neural Stimulation

The ultimate test is the efficiency of optogenetic stimulation. Using the fast multidither coherent optical adaptive technique (fCOAT) system to correct for scattering, researchers achieved subcellular-resolution optogenetic stimulation through brain tissue [3]. The results demonstrated a stimulation efficiency enhancement of up to 300% with a corrected focus compared to stimulation using the uncorrected speckle pattern [3]. This quantitatively proves that overcoming scattering is not just about achieving a pretty focus but is directly tied to the experimental efficacy and precision of optogenetic manipulation.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Light-Based Stimulation Through Tissue

| Performance Metric | Blue Light Systems | Red Light Systems | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Efficiency vs. Speckle | Information Missing | Up to 300% enhancement [3] | fCOAT correction through brain tissue |

| Focus FWHM Through 500 μm Brain Slice | Information Missing | < 4 μm [3] | After wavefront shaping correction |

| Peak-to-Background Ratio (PBR) | Information Missing | ~200 (brain slice), ~45 (one mouse skull) [3] | After wavefront shaping correction |

| Typical Opsin Kinetics | Very fast (e.g., ChR2) [4] | Fast (e.g., ChrimsonR) to very fast (e.g., vfChrimson) [5] | Measurement of photocurrent rise/decay |

Technological Solutions to Overcome Scattering

The challenge of light scattering has spurred innovative technological solutions that enhance both blue and red light systems.

Wavefront Shaping

- Principle: These methods measure how tissue scrambles light and then pre-shape the light's wavefront to counteract the scattering, forming a tight focus deep inside the tissue [3].

- Implementation: Systems like the fCOAT use a spatial light modulator (SLM) to segment the wavefront and iteratively find the optimal pattern to focus through dynamic scattering media [3]. This allows the formation of a stable, adjustable focus that can be maintained for over 60 seconds, sufficient for many optogenetic protocols [3].

- Application: This technique is wavelength-agnostic but is particularly beneficial for shorter wavelengths like blue light that are more severely scattered.

Implantable μ-LED Devices

- Principle: To bypass superficial tissue entirely, researchers have developed miniaturized, flexible, and sometimes wireless LED implants that can be placed directly on or near the target structure [6] [2].

- Advantage: These devices allow for local light delivery regardless of wavelength, eliminating the penetration problem. μ-LED arrays also offer high spatial resolution for precise control [6].

- Applications: Such implants have been used for optogenetic stimulation in the brain, spinal cord, and even peripheral nerves [2]. For example, a μ-LED system conforming to the spinal cord dura mater has been integrated with a sensing module for closed-loop control after spinal cord injury [2].

Opsin Engineering & Spectral Separation

A parallel strategy involves engineering the optogenetic tools themselves rather than the light. A key development is the creation of red-shifted channelrhodopsins (R-ChRs) like Chrimson, ChrimsonR, and the faster vfChrimson [1] [5]. These opsins are excited by longer wavelengths that penetrate tissue more effectively. However, a persistent problem is "cross-talk" or "bleed-through," where R-ChRs are also activated by the more energetic blue light [5]. A sophisticated solution involves co-expressing a red-shifted excitatory opsin with a blue-light-sensitive inhibitory anion channelrhodopsin (ACR). In this system, red light only activates the R-ChR, causing excitation. Blue light activates both the R-ChR and the ACR, with the resulting shunting inhibition suppressing neural firing, effectively creating spectral selectivity [5].

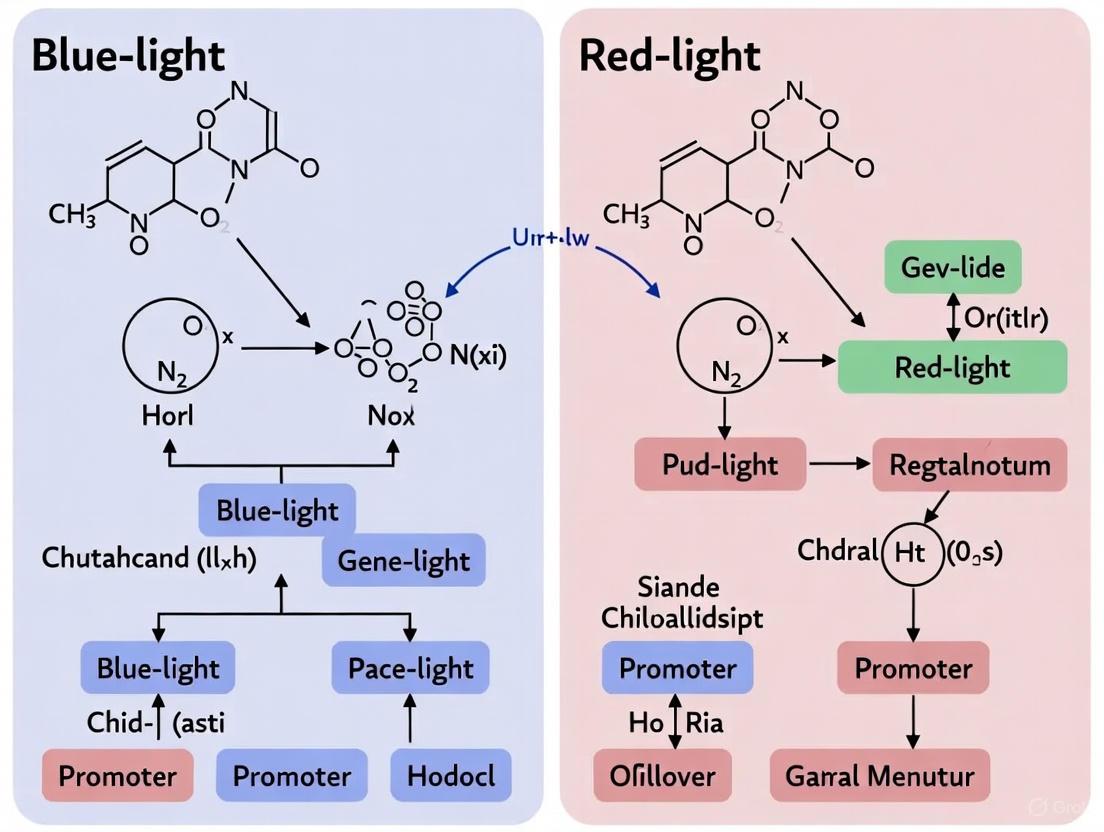

Diagram 1: Logical workflow of technological solutions to the challenge of light scattering in optogenetics, showing the three main strategic categories and their outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in deep-tissue optogenetics requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential components for designing and executing such studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Advanced Optogenetics

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Utility | Example Variants & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Excitatory Opsins | Depolarizes neurons by cation influx upon light activation. | ChR2 (Blue): Classic, fast kinetics [4].ChrimsonR (Red): Red-shifted, less cross-talk [7].vfChrimson (Red): Very fast kinetics for high-frequency stimulation [5]. |

| Inhibitory Opsins | Hyperpolarizes/suppresses neurons via chloride or proton pumps. | GtACR2 (Blue): Anion channel, effective but slow kinetics [5].ZipACR (Blue): Ultrafast anion channel [5].Modified ZipACR (I151T/V): Engineered for faster, optimized kinetics [5]. |

| Viral Delivery Vectors | Enables targeted gene delivery of opsin genes to specific cell types. | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV): Low immunogenicity, serotypes for cell-specific targeting [4].AAV2.7m8: Enhanced spread in neural tissue [7]. |

| Wavefront Shaping System | Corrects for light scattering to form a tight focus deep in tissue. | fCOAT System: Uses SLM for fast, stable focusing in dynamic tissue [3]. |

| Implantable μ-LED Devices | Local, wireless light delivery to deep structures, bypassing tissue. | Flexible μ-LED Arrays: Conform to brain or spinal cord [6] [2].Closed-Loop Implants: Integrate sensing and stimulation [2]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for comparison, below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: fCOAT for Deep-Tissue Optogenetic Stimulation

This protocol is adapted from work demonstrating high-precision optogenetics through scattering brain tissue [3].

- System Setup: Construct an fCOAT system comprising a focusing part for stimulation and an inverted imaging part for monitoring calcium signals and the formed focus. The scattering medium (e.g., brain slice) is placed between the two objective lenses.

- Wavefront Modulation: Conjugate a Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Spatial Light Modulator (FLC-SLM) to the rear pupil plane of the focusing objective. Segment the SLM pixels into N x N segments (e.g., 16x16 to 64x64).

- Iterative Correction: Perform an iterative optimization process. The number of measurements required is less than 4N². Use the intensity of scattered light at a pre-defined target point as the feedback signal.

- Focus Generation & Validation: Generate a compensation profile after one iteration (more can be used for accuracy). Validate the focus by measuring the Peak-to-Background Ratio (PBR) and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the corrected focus. A typical result through a 500-μm brain slice is a PBR of ~200 and FWHM of <4 μm.

- Optogenetic Stimulation: Illuminate the corrected focus on neurons expressing optogenetic actuators (e.g., channelrhodopsins). Use a shutter to switch the light at a frequency matching the actuator's kinetics. Compare stimulation efficiency (e.g., calcium signal amplitude) against uncorrected speckle stimulation.

Protocol: Validating Spectral Separation with Zip-IvfChr

This protocol is based on the development of a dual-color system for activation and suppression with high temporal precision [5].

- Construct Design: Create a single expression vector (e.g., for AAV delivery) containing both the red-shifted excitatory opsin (membrane-trafficking optimized vfChrimson, or IvfChr) and a fast blue-light-sensitive inhibitory opsin (engineered ZipACR variant, e.g., I151T or I151V).

- Cell Transfection/Transduction: Introduce the construct into the target neurons, either in vitro (e.g., cultured hippocampal neurons) or in vivo (e.g., stereotactic injection into a target brain region like the facial motor nucleus).

- Slice Electrophysiology (in vitro validation): Perform whole-cell patch-clamp recordings on transfected neurons. Apply light stimuli:

- Red Light Test (635 nm pulses): Apply pulses of varying frequencies and durations. Successful system performance is indicated by time-locked action potential generation at high frequencies (e.g., up to 40 Hz).

- Blue Light Test (470 nm pulses): Apply pulses of the same duration and intensity. Successful performance is indicated by a lack of action potential generation during the pulse. Transient suppression of ongoing activity should be fully reversed within 5 ms after pulse termination due to fast ZipACR kinetics.

- In Vivo Behavioral Assay: In anesthetized animals expressing Zip-IvfChr in motor neurons controlling vibrissae:

- Red Light Stimulation: Should trigger robust, measurable vibrissa movement.

- Blue Light Stimulation: Should trigger no or minimal vibrissa movement, confirming effective spectral separation and suppression.

Diagram 2: Signaling pathway for dual-color optogenetic control, illustrating how co-expression of a red-shifted channelrhodopsin (R-ChR) and a blue-light-sensitive anion channelrhodopsin (B-ACR) enables spectral separation of excitation and suppression.

In both photobiomodulation (PBM) and optogenetic research, the wavelength of light is a fundamental parameter that dictates therapeutic efficacy and experimental success. Light penetration depth directly influences which biological targets can be activated or modulated, from superficial skin layers to deeper tissues and engineered cellular systems. This comparative analysis quantifies the performance differences between blue and red light, providing researchers with evidence-based parameters to guide experimental design and therapeutic development in optogenetics and drug discovery.

The differential penetration arises from the interaction between light and biological tissues. Shorter wavelengths in the blue spectrum (400-495 nm) are more readily scattered and absorbed by surface structures, while longer red and near-infrared wavelengths (600-1000 nm) experience less scattering and can reach deeper tissue layers [8] [9]. This physical principle underpins the selective applications of different light wavelengths across biomedical research and therapeutic applications.

Quantitative Analysis: Penetration Depth and Optical Properties

Penetration Depth by Wavelength

Table 1: Penetration Depth Characteristics of Different Light Wavelengths

| Light Type | Wavelength Range (nm) | Penetration Depth | Primary Biological Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Light | 400-495 nm | 0.07 - 1.0 mm [9] | Epidermis, superficial bacterial colonies [8] [10] |

| Green Light | 520-570 nm | ~1 mm (estimated) | Epidermis, superficial dermis |

| Red Light | 630-700 nm | 1-2 mm [8], up to 2-5 mm [10] | Dermis, fibroblasts, capillaries |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) | 700-1000 nm | 5-10 mm [8], up to 25 mm [10] | Hypodermis, muscles, joints, bones |

Experimental measurements from human ex vivo tissues demonstrate how penetration depth (δ) varies significantly across wavelengths and tissue types [11]. These values represent the depth at which irradiance drops to approximately 37% (1/e) of its surface value, highlighting the stark contrast between blue and red light performance.

Optical Properties Across the Spectrum

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Optical Penetration Depths (δ) in Human Tissues

| Tissue Type | 633 nm (Red) δ (mm) | 675 nm (Red) δ (mm) | 780 nm (NIR) δ (mm) | 835 nm (NIR) δ (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung (normal) | 0.76 | 0.84 | 1.15 | 1.31 |

| Lung carcinoma | 1.36 | 1.65 | 1.92 | 2.03 |

| Mammary tissue | 1.45 | 1.75 | 1.98 | 2.12 |

| Mammary carcinoma | 1.82 | 1.95 | 2.15 | 2.28 |

| Myometrium | 1.15 | 1.35 | 1.65 | 1.78 |

| Uterine mioma | 1.45 | 1.65 | 1.85 | 2.05 |

| Bladder | 1.95 | 2.25 | 2.55 | 2.75 |

| Brain | 1.85 | 2.15 | 2.45 | 2.65 |

| Muscle | 1.55 | 1.75 | 2.05 | 2.25 |

| Skin (epidermis/dermis) | 0.65 | 0.75 | 1.05 | 1.25 |

Data adapted from measurements on human ex vivo tissues [11]

The data reveals that tumor tissues often exhibit greater light penetration compared to their normal counterparts, a critical consideration for photodynamic therapy applications. The progressive increase in penetration depth from red to near-infrared wavelengths is consistent across all measured tissue types.

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Light-Tissue Interactions

In Vitro Assessment of Cellular Responses

Protocol 1: Evaluating Low-Intensity Light Effects on Keratinocytes

A customized LED exposure system enables parallel investigation of multiple wavelengths on human keratinocytes (HaCaT cell line) [12]:

- Device Setup: Compact, modular LED array compatible with 24-well plates, battery-powered with adjustable intensities (0.09-0.8 mW) and pulse modulation capabilities

- Wavelength Parameters: Yellow (585 nm), orange (610 nm), and red (660 nm) light applied for 10 minutes (energy density < 0.032 J/cm²)

- Cell Culture: Immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS

- Assessment Methods:

- In vitro wound model: Confluent monolayer scratched with pipette tip, measuring closure rate

- Immunohistochemistry: Cell viability, proliferation (Ki-67), ROS production, mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 staining)

- Timeline: Analysis at 48 hours post-irradiation

This system enables standardized comparison of multiple wavelengths under identical conditions, addressing reproducibility challenges in PBM research [12].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for assessing low-intensity light effects on keratinocytes [12]

Transcriptomic Analysis of Blue Light Effects

Protocol 2: Investigating Blue Light (450 nm) Molecular Mechanisms

Comprehensive analysis of blue light effects on wound healing-associated cells [13]:

- Cell Lines: Immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT), normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC)

- Irradiation Parameters: 450 nm blue light at low fluence (4.5 J/cm²) and high fluence (18 J/cm²)

- Molecular Assessments:

- Kinetic assays for cell viability, proliferation, ATP quantification

- Migration assays (scratch/wound healing)

- Apoptosis assays (Annexin V/PI staining)

- RNA sequencing for transcriptome analysis

- Pathway Analysis: TGF-β, ErbB, VEGF signaling pathways, DNA replication, cell cycle regulation

This protocol demonstrates the biphasic dose-response relationship characteristic of PBM, where low fluences stimulate cellular activities while high fluences inhibit them [13].

Biological Mechanisms and Research Applications

Chromophores and Signaling Pathways

The distinct biological effects of blue versus red light originate from their interactions with different cellular chromophores:

Blue Light (400-495 nm): Primarily absorbed by flavins and flavoproteins (FMN in complex I, FAD in complex II) in the electron transport chain [13]. Also targets opsins (OPN3, OPN4) and nitrosated proteins, releasing nitric oxide (NO) to influence vascular function and cellular signaling [9] [13].

Red Light (630-700 nm): Mainly absorbed by cytochrome c oxidase (CCO), the terminal enzyme in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [9] [12]. This interaction boosts electron transport, increases ATP synthesis, and modulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling.

Near-Infrared Light (700-1000 nm): Penetrates most deeply, potentially targeting water molecules and TRPV1 calcium ion channels while also influencing mitochondrial function [12].

Figure 2: Molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways for blue vs. red light [9] [13] [12]

Optogenetics Applications and Opsin Engineering

In optogenetics, the penetration difference directly influences system design and experimental outcomes:

Blue Light Optogenetics: Systems like LACE (Light-Activated CRISPR Effector) use CRY2-CIBN dimerization under blue light for precise transcriptional control [14]. While offering high temporal precision, blue light's limited penetration and potential phototoxicity represent significant constraints.

Red Light Optogenetics: Emerging systems (iLight, MagRed, REDLIP) leverage red-shifted opsins (ChrimsonR, MCOs) for deeper tissue penetration and reduced phototoxicity [14] [7]. These systems often require lower light intensities and enable manipulation of deeper brain structures or tissues.

Strategic Target Cell Selection in optogenetics reflects penetration limitations [7]:

- Retinal Ganglion Cells (RGCs): Targeted in advanced retinal degeneration where photoreceptors are lost; accessible to both blue and red light in ocular applications

- ON-Bipolar Cells: Targeted in earlier disease stages; require deeper-penetrating red light for effective stimulation

- Cortical and Deep Brain Neurons: Primarily accessible to red/NIR light systems due to scalp and skull scattering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Light-Based Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HaCaT (human keratinocytes) [12], NHDF (normal human dermal fibroblasts) [13], HUVEC (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) [13], HEK293T (human embryonic kidney) [14] | In vitro models for wound healing, angiogenesis, and optogenetic manipulation |

| Optogenetic Tools | LACE system (CRY2-VP64, CIBN-dCas9) [14], ChrimsonR [7], MCOs (Multi-Characteristic Opsins) [7], Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) [7] | Light-controlled gene expression, neural stimulation, cellular signaling |

| LED Light Sources | Custom LED arrays [12], Commercial panels (Celluma) [10], OptoPlate systems [14] | Controlled light delivery for in vitro and in vivo applications |

| Analysis Tools | RNA sequencing [13], Flow cytometry [14], Mitochondrial membrane potential assays (JC-1) [12], ATP quantification [13] | Assessment of cellular responses, transcriptomic changes, metabolic effects |

| Animal Models | Retinitis pigmentosa models [7], Diabetic wound models [13], Wild-type rodents for tissue penetration studies [11] | In vivo validation of light-based therapies and penetration parameters |

The quantitative comparison between blue and red light performance reveals a fundamental trade-off: blue light offers superior spatial precision for superficial targets while red light provides broader tissue access for deeper applications. This dichotomy directly influences experimental design and therapeutic development across multiple domains.

For optogenetics research, selection of opsins with appropriate action spectra must align with target tissue depth and desired precision. Blue light systems remain valuable for cultured cells or superficial tissue manipulation, while red-shifted opsins enable deeper interventions with reduced phototoxicity. In drug development and therapeutic applications, understanding these optical properties guides device design and treatment protocols—from topical antimicrobial blue light treatments to deep-tissue regenerative therapies using red/NIR illumination.

The future of light-based research lies in multimodal approaches that strategically combine wavelengths to simultaneously target multiple biological processes at different tissue depths. As optogenetic tools continue to evolve with enhanced sensitivity and novel spectral properties, researchers will gain increasingly precise control over biological systems, further expanding the therapeutic potential of light in medicine and basic research.

Optogenetics has revolutionized neuroscience by enabling precise, cell-specific control of neural activity with light. However, a significant challenge in deploying this technology for in vivo applications, especially in larger brains or for potential clinical therapies, is the limited ability of light to penetrate biological tissues. The journey of light from an external source to its target neurons in the brain is hindered by the skin, skull, and blood that lie in its path. The wavelength of light used is a critical determinant of its success, leading to a fundamental comparison between traditionally used blue-light systems and the emerging red-light alternatives. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, focusing on the core challenge of light-tissue interactions and presenting the latest experimental data and tools shaping the field.

The Physics of Light-Tissue Interaction

When light travels through biological tissues, its intensity is diminished by three primary physical phenomena: scattering, absorption, and reflection. The extent of these interactions is heavily dependent on the light's wavelength.

- Scattering occurs when light particles (photons) collide with and are deflected by structures within the tissue. It is the most significant factor reducing light penetration. Shorter wavelengths are scattered much more strongly than longer wavelengths; consequently, blue light scatters far more than red light within the brain [1].

- Absorption happens when the energy of a photon is captured by specific molecules in the tissue. Key absorbers in the path to the brain include:

- Hemoglobin in blood, which has a much higher absorption coefficient for blue light than for red light [1].

- Melanin, the skin's photoprotective pigment, which also preferentially absorbs blue light [1].

- Water and fat, though their absorption is relatively similar across blue and red spectra used in optogenetics, with water mainly absorbing at longer infrared wavelengths [1].

- Reflection at the skin surface has a minuscule overall effect on penetration and shows less wavelength dependence [1].

The following diagram illustrates how these factors create a more favorable path for red light.

Quantitative Comparison: Blue Light vs. Red Light

The physical differences between blue and red light translate into direct, measurable advantages for red light in in vivo optogenetics. The table below summarizes key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Blue vs. Red Light in Biological Tissue

| Performance Metric | Blue Light (~470 nm) | Red Light (~630 nm) | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Penetration Depth in Skin | ~1 mm [1] | 4–5 mm [1] | Measurement of light attenuation in tissue [1] |

| Scattering in Neural Tissue | High [1] | Significantly Lower [1] | Analysis of light propagation in rodent brain [1] |

| Absorption by Hemoglobin | High [1] | Low [1] | Spectrophotometry of hemoglobin [1] |

| Typical Opsin Single-Channel Conductance | ~40 fS (ChR2) [15] | ~80-110 fS (ChRmine/ChReef) [15] | Noise analysis via automated patch-clamp [15] |

| Photocurrent Desensitization | Variable; high in some opsins | Engineered to be minimal (e.g., ChReef) [15] | Electrophysiology on engineered opsin variants [15] |

| Suitability for Non-Invasive Deep Brain Stimulation | Limited, requires invasive implants | High, enables "implant-free" paradigms [15] | In vivo cardiac and deep brain stimulation in mice [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Neurovascular Coupling

To illustrate how these principles are investigated, the following is a detailed methodology from a study examining neurovascular coupling using optogenetics. This protocol highlights the use of specific wavelengths and the importance of targeting cell bodies versus distal projections [16].

Objective: To investigate the variability in hemodynamic responses driven by the interhemispheric circuit during optogenetic and somatosensory activation [16].

Experimental Workflow:

Key Findings from this Protocol:

- Stimulation of cell bodies could evoke either predominant postsynaptic inhibition or excitation in the connected hemisphere, leading to fundamentally different hemodynamic responses: inhibition caused oxygen consumption without hyperemia, while excitation led to a biphasic response with functional hyperemia [16].

- Crucially, optogenetic stimulation at distal axonal projections consistently failed to evoke a robust increase in cerebral blood flow, despite causing local oxygen consumption. This indicates that signals originating from the cell body are necessary for functional hyperemia [16].

Advanced Tools and Reagents for Red-Light Optogenetics

The advancement of red-light optogenetics relies on the development of new opsins and supporting reagents. The table below details key components of the modern red-light toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Red-Light Optogenetics

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Key Function | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChReef [15] | Red-Shifted Cation Channelrhodopsin | High-efficiency neural excitation; minimal desensitization enables sustained stimulation. | Restored visual function in blind mice with iPad-screen light levels; enabled efficient cardiac pacing [15]. |

| iLight System [17] | Bacterial Phytochrome (BphP)-based Transcriptional Activator | NIR light-controlled gene expression. | Driven light-induced insulin production in a diabetes model, reducing blood glucose by ~60% [17]. |

| Blvra⁻/⁻ Mouse Model [17] | Genetically Modified Animal | Knocks out biliverdin reductase A, elevating endogenous biliverdin (BV) chromophore levels. | Enhanced iLight performance ~25-fold in cells and ~100-fold in neurons; improved PA imaging depth and sensitivity [17]. |

| Zip-IvfChr System [5] | Dual Opsin System (vfChrimson + ZipACR mutants) | Enables dual-color control: red light for activation, blue light for suppression with high temporal precision. | Achieved high-frequency APs with red light; blue light suppressed APs with reversal within 5 ms post-pulse in brainstem neurons [5]. |

| 3D-PAULM [17] | Imaging System (Photoacoustic & Ultrasound) | Enables simultaneous molecular imaging of BphP probes and brain vasculature at ~7 mm depth. | Imaged BphP1-expressing neurons and vasculature through intact scalp and skull in Blvra⁻/⁻ mice [17]. |

The choice between blue and red light for optogenetic systems extends far beyond simple color preference. It is a critical decision grounded in the physics of light-tissue interaction. Quantitative data unequivocally shows that red light offers superior tissue penetration, reduced scattering, and lower absorption by blood compared to blue light. While blue-light opsins have been the workhorses of in vitro neuroscience, the future of non-invasive in vivo research and clinical translation is increasingly red. The development of high-performance red-shifted opsins like ChReef, along with supporting technologies such as chromophore-enhanced animal models and advanced multimodal imaging, provides researchers with a powerful and expanding toolkit to overcome the biological barriers of skin, skull, and blood.

Optogenetics has revolutionized neuroscience by enabling precise control of neuronal activity with light. A critical consideration in experimental design and therapeutic application is the choice of illumination wavelength, as it directly influences both the efficacy of stimulation and the potential for adverse effects on biological tissues. This guide provides a comparative assessment of the phototoxicity and thermal damage risks associated with blue-light and red-light optogenetic systems. We evaluate these competing technologies by examining their fundamental physical properties, biological interactions, and empirical findings from recent studies, providing researchers with a evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate optogenetic tools that balance performance with safety.

Comparative Analysis: Blue Light vs. Red Light Optogenetics

Fundamental Physical and Biological Properties

Table 1: Physical Properties and Biological Interactions of Blue vs. Red Light

| Characteristic | Blue Light (∼470 nm) | Red Light (∼630-710 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Penetration Depth | Lower (∼1 mm in skin) [1] | Higher (4-5 mm in skin) [1] |

| Light Scattering | High [1] | Low [1] |

| Hemoglobin Absorption | High [1] | Lower [1] |

| Primary Phototoxicity Mechanism | Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) generation, often mediated by culture media [18] | Less intrinsic phototoxicity; age-dependent effects observed [19] |

| Reported Gene Expression Alterations | Upregulation of Immediate Early Genes (IEGs) like Fos and Fosb [18] | No significant impact on IEG expression reported under standard conditions [19] |

| Key Thermal Consideration | Lower wavelength, but thermal load is more a function of intensity and device design than wavelength alone [20] | Longer wavelength, but thermal load is more a function of intensity and device design than wavelength alone [20] |

Documented Cellular and Tissue Effects

Table 2: Empirical Evidence of Biological Effects and Damage

| Effect Type | Blue Light Exposure | Red Light Exposure |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Cytotoxicity | Loss of cell viability at elevated exposure; IEG induction in primary rat cortical cultures [18] | Not observed in young animals; marked effects in aged mice [19] |

| In Vivo Tissue Damage | Local damage and autofluorescence in the cerebral cortex of young mice; ablation of cortical tissue in older mice [19] | No noticeable effect in young mice; damaged fiber bundles and reduced EEG power in old mice [19] |

| Neuroinflammatory Response | Gliosis (GFAP-positive astrocytes) around lesioned area [19] | Minor gliosis directly under LED in young mice; reactive microglia and gliosis in older mice [19] |

| Functional Neural Impact | Moderately reduced EEG power (20-40%) [19] | Massive reduction in EEG power (40-90%), particularly in theta range, in older mice [19] |

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Blue Light Phototoxicity in Neuronal Cultures

- Objective: To quantify blue light-induced gene expression alterations and cell viability loss in primary neuronal cultures, and to test the efficacy of photoinert media in mitigating these effects [18].

- Cell Preparation: Primary rat cortical cultures are generated from E18 rat cortical tissue. Cells are seeded on poly-L-lysine-coated plates and grown in complete Neurobasal media (Neurobasal Medium supplemented with B27 and L-glutamine) for 11 days in vitro (DIV) [18].

- Media Intervention: On DIV10, culture media is replaced with either standard complete Neurobasal media or a photoinert alternative (e.g., NEUMO media supplemented with SOS and Glutamax) [18].

- Illumination Protocol: On DIV11, cultures are exposed to blue light (470 nm) using a custom LED array. A typical paradigm involves pulses (e.g., 1-second) at a 5% duty cycle for 4 hours, with an irradiance of ~0.4-0.9 mW/cm². Control plates are wrapped in foil and placed on an identical enclosure [18].

- Outcome Measures:

Protocol 2: Evaluating Age-Dependent Red Light EffectsIn Vivo

- Objective: To determine the functional and structural consequences of large-area red light exposure on the brains of young versus old mice [19].

- Animal Model: Young (3-month) and old (16-month) C57BL/6 mice are implanted with a skull-mounted LED and electroencephalogram (EEG)/electromyogram (EMG) electrodes [19].

- Stimulation Protocol: Red light (∼630 nm, ~15 mW) is delivered in 10 ms pulses at 10 Hz for 8.5 hours during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep using a closed-loop system [19].

- Outcome Measures:

- Functional Assessment: Continuous EEG recording is performed to quantify spectral power (e.g., in the theta range) and sleep architecture before, during, and after stimulation [19].

- Behavioral Analysis: Animals are monitored for hyperactivity, circling, or hypoactivity [19].

- Histological Analysis: Post-experiment, brains are examined via DAPI, GFAP (astrocytes), IBA1 (microglia), and silver staining (fiber tract integrity) to identify damage and neuroinflammation [19].

Mechanisms of Phototoxicity and Thermal Load

Signaling Pathways in Light-Induced Damage

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular mechanisms and signaling pathways implicated in phototoxicity for blue and red light, highlighting their distinct modes of action.

Thermal Load Management in Implantable Devices

Thermal damage is a critical risk factor for both blue and red-light systems, particularly with implantable devices. The thermal load is primarily a function of light intensity, pulse duration, and the design of the device itself, rather than wavelength alone [20]. A unified framework for managing this risk focuses on solving the thermal-optical equation to predict temperature rise in brain tissue. Key parameters include device geometry, material properties, and emission profiles. Optimization guided by such analyses is essential to reduce local heating without compromising the functionality of the optogenetic intervention [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Phototoxicity Assessment

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cortical Cultures | In vitro model system for quantifying neuronal phototoxicity and gene expression changes. | Isolated from E18 rat cortex; used to test blue light effects in a controlled environment [18]. |

| Photoinert Cell Culture Media | Media formulated to minimize light-induced ROS generation, mitigating phototoxic effects. | NEUMO media supplemented with SOS; prevents blue light-induced IEG expression in cortical cultures [18]. |

| Custom LED Illumination Systems | Provides precise control over light wavelength, intensity, pulse width, and duty cycle for stimulation. | Used for both in vitro (e.g., 470 nm array) and in vivo (e.g., skull-mounted LED) photostimulation [18] [19]. |

| AAV Vectors for Opsin Delivery | Gene delivery tools for targeted expression of optogenetic actuators (e.g., Chrimson, GtACR2). | Enables cell-type-specific expression of red-shifted channelrhodopsins or inhibitory anion channels [5] [21]. |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Functional assessment of brain activity in response to light exposure in vivo. | Measures spectral power reduction (e.g., in theta range) as an indicator of red-light-induced neural deficits in aged mice [19]. |

| Histological Stains (GFAP, IBA1, Silver) | Detect structural damage and neuroinflammation in tissue post-illumination. | GFAP labels reactive astrocytes; IBA1 labels activated microglia; silver staining reveals damaged fiber tracts [19]. |

The choice between blue and red light for optogenetic applications involves a direct trade-off between tissue penetration and age-dependent safety profiles. Blue light systems, while foundational, carry a significant risk of phototoxicity mediated by ROS generation, which can be partially mitigated by using photoinert media in vitro. Red light systems offer superior tissue penetration and reduced phototoxicity in standard models, making them attractive for deep brain stimulation. However, emerging evidence of severe, age-dependent pathological effects in older animals necessitates careful consideration for long-term therapeutic applications or studies involving aging models. Ultimately, protocol optimization—including media selection, light dosage, and careful thermal management of implants—is paramount for minimizing side effects and ensuring the validity and safety of both blue- and red-light optogenetic research.

Toolkits and Techniques: Actuators, Applications, and Emerging Systems

Blue-light optogenetic tools represent a foundational technology in neuroscience and cell biology, enabling precise spatiotemporal control over cellular functions. These tools primarily consist of channelrhodopsins for direct membrane potential manipulation and LOV (Light-Oxygen-Voltage) domains for controlling intracellular signaling processes. Unlike red-light systems that offer superior tissue penetration, blue-light tools typically provide faster kinetics and higher light sensitivity, making them ideal for applications requiring millisecond-scale precision in accessible tissue regions or in vitro systems. The core distinction between these tool classes lies in their mechanisms: channelrhodopsins function as light-gated ion channels that directly alter membrane potential, while LOV domains serve as modular photoswitches that control protein-protein interactions and enzymatic activities through light-induced conformational changes [1] [22] [23].

This comparison guide focuses on two prominent channelrhodopsin variants (ChR2 and Chronos) alongside the versatile LOV domain platform, providing researchers with objective performance data and experimental protocols to inform tool selection for specific applications. We present quantitative comparisons of temporal resolution, spectral properties, and light sensitivity, along with detailed methodologies for implementing these tools in both neuronal and non-neuronal systems, framed within the broader context of optogenetic tool development that increasingly seeks to balance kinetic performance with tissue penetration challenges [1] [24].

Channelrhodopsins: Direct Neural Control

Channelrhodopsins are light-gated ion channels derived from microbial sources that provide direct control over membrane potential. Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), isolated from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, was the first opsin demonstrated to enable precise optical control of neuronal firing, revolutionizing neuroscience research [25] [23] [4]. Upon blue-light exposure (~470 nm), ChR2 undergoes a conformational change that opens a cation-conducting pore, allowing Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions to flow along their electrochemical gradients, resulting in membrane depolarization and action potential generation in excitable cells [25] [23].

Chronos represents a more recently developed channelrhodopsin variant engineered for superior kinetic properties. Isolated through extensive screening of algal species, Chronos exhibits faster opening and closing kinetics compared to ChR2, enabling more precise temporal control of neuronal activity, particularly at high stimulation frequencies [26] [24]. Both tools require the ubiquitous chromophore all-trans-retinal (or its analogs) for proper function, which is typically present in sufficient quantities in mammalian tissues [25].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Blue-Light Activated Channelrhodopsins

| Property | ChR2 | Chronos |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Activation Wavelength | 470 nm [25] | ~500 nm [24] |

| Ion Selectivity | Cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+) [23] | Cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+) [24] |

| Temporal Kinetics | Fast activation, relatively slow deactivation [24] | Very fast activation and deactivation [26] [24] |

| Temporal Fidelity at High Frequency | Reduced synchronization > 40 Hz [26] | Maintains synchronization up to 200+ Hz [26] |

| Desensitization | Moderate desensitization during sustained illumination [24] | Reduced desensitization [24] |

| Primary Applications | General neuronal stimulation, medium-frequency protocols [23] | High-frequency stimulation, precise temporal patterning [26] [24] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in the performance characteristics of ChR2 and Chronos that impact their experimental utility. In an optogenetic model of the auditory brainstem implant, Chronos demonstrated superior temporal resolution compared to ChR2, maintaining higher response synchrony at stimulation rates of 56, 168, and 224 pulses per second (p < 0.05) [26]. This enhanced temporal fidelity makes Chronos particularly valuable for applications requiring precise spike timing or high-frequency stimulation protocols.

Neural circuit engagement also differs between these tools. When expressed in cortical pyramidal neurons under the CaMKII promoter, ChR2, Chronos, and Chrimson (a red-shifted opsin) evoked distinct patterns of network activity despite similar expression levels [24]. Specifically, the tools differentially regulated cortical γ oscillations (30-80 Hz), with Chronos producing more naturalistic activity patterns compared to ChR2, suggesting that opsin kinetics significantly influence network-level responses to optogenetic stimulation [24].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Channelrhodopsins

| Performance Metric | ChR2 | Chronos | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Spike Rate | ~40 Hz [26] | >200 Hz [26] | Auditory brainstem implant model [26] |

| Response Latency | ~2.3 ms [4] | ~1 ms (estimated) [24] | Neuronal depolarization [24] [4] |

| Current Rise Rate | 160 ± 111 pA/ms [4] | Not specified | HEK293 cells and neurons [4] |

| γ-Band Power Modulation | Moderate increase [24] | Distinct pattern from ChR2 [24] | Mouse visual cortex in vivo [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Channelrhodopsin Applications

Viral-Mediated Expression in Mouse Cortex

This protocol enables optogenetic control of specific neuronal populations in the mouse brain using ChR2 or Chronos, based on methodology from Jun & Cardin (2019) [24]:

Surgical Procedure: Anaesthetize C57BL/6J mice (3-5 months old) and secure in a stereotaxic apparatus. Create a small burr hole craniotomy in the skull over the target brain region (e.g., visual cortex: -3.2 mm posterior, -2.5 mm lateral relative to bregma). Inject 1 μL of AAV5-CaMKII-ChR2-GFP or AAV5-CaMKII-Chronos-GFP through a beveled glass micropipette at a depth of -500 μm from the brain surface. Maintain an injection rate of approximately 100 nL/min to minimize tissue damage. Following injection, leave the pipette in place for 5 minutes before withdrawal to prevent viral backflow.

Expression Period: Allow 4 weeks for robust opsin expression before conducting experiments. Verify expression patterns and localization via GFP fluorescence through histology. For histology, perfuse mice with 4% PFA in PBS, post-fix brains for 8 hours, section at 40 μm thickness, and image with confocal microscopy. Counterstain with NeuN (1:500) to identify neuronal populations [24].

In Vivo Optogenetic Stimulation and Recording

Setup Preparation: Prepare a craniotomy over the virus expression site and position an optical fiber (200 μm core diameter) coupled to a 470 nm laser (for ChR2 or Chronos) on the dura surface. Position recording electrodes (tetrodes) immediately adjacent to the fiber.

Stimulation Protocol: Deliver 1.5-second laser pulses at varying light intensities (0.5-10 mW/mm²) with 10-second inter-pulse intervals. Present 150 total pulses per session, grouped into bouts of 30 pulses separated by 5-minute baseline periods to assess both transient and sustained neural responses.

Data Collection: Record extracellular multiunit activity and local field potentials (LFPs) simultaneously. Filter MU activity at 600-9000 Hz and sample at 40 kHz. Record LFP with open filters, referenced to the cortical surface [24].

LOV Domains: Modular Photoswitches for Cellular Signaling

LOV (Light-Oxygen-Voltage) domains represent a distinct class of blue-light optogenetic tools that function as modular photoswitches to control intracellular signaling processes rather than directly altering membrane potential. These small (∼110 amino acid) protein domains originate from plant phototropins and utilize a flavin mononucleotide (FMN) chromophore to sense blue light (∼450 nm) [22] [27]. Unlike channelrhodopsins, LOV domains function through light-induced conformational changes that can be harnessed to control protein-protein interactions, protein localization, and enzymatic activities [22] [23].

The photochemical mechanism of LOV domains involves blue-light absorption by the FMN cofactor, leading to formation of a covalent bond between the C4a position of the flavin isoalloxazine ring and a conserved cysteine residue within the LOV domain. This adduct formation triggers rotation of a conserved glutamine (Q513 in AsLOV2) and subsequent unfolding of the C-terminal Jα helix, which serves as the primary signal transduction element linking light absorption to effector domain function [22] [27]. The photocycle is thermally reversible in the dark, with decay kinetics ranging from seconds to hours depending on the specific LOV variant [22].

Several LOV platforms have been developed for optogenetic applications, including:

- AsLOV2 from Avena sativa: Fast-cycling variant (τ ≈ 80s) widely used in optogenetic designs [22]

- VVD from Neurospora crassa: Slow-cycling variant (τ ≈ 5h) used in dimerization systems [22]

- EL222 from Erythrobacter litoralis: Fast-cycling bacterial LOV domain fused to a DNA-binding domain [22]

Quantitative Performance Characteristics

LOV domains exhibit diverse photochemical properties that determine their suitability for different experimental applications:

Table 3: Characteristics of Major LOV Domain Variants

| LOV Variant | Dark Recovery Half-life | Dynamic Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AsLOV2 | ~80 seconds [22] [27] | Medium | PA-Rac1, iLID, LEXY systems [22] [27] |

| VVD | ~5 hours [22] | High | Dimerization systems [22] |

| EL222 | ~30 seconds [22] | Medium | Transcriptional control [22] |

| YtvA | ~100 minutes [22] | Medium | Stress response studies [22] |

| FKF1 | >24 hours [22] | High | Flowering time control [22] |

A critical consideration for LOV domain applications is their dark-state activity, which can limit dynamic range in some optogenetic constructs. Molecular dynamics simulations extending to 7 μs have revealed that residues N414 and Q513 serve as critical mediators linking FMN photochemistry to Jα helix unfolding in AsLOV2 [27]. Mutagenesis studies demonstrate that the N414A mutation accelerates Jα helix unfolding kinetics while reducing cellular activity in the Zdk2-AsLOV2 dimerization system by 4-fold, highlighting the importance of these residues for optimal tool function [27].

Experimental Protocols for LOV Domain Applications

LOVTRAP Dimerization Assay

The LOVTRAP system utilizes the AsLOV2 domain and its binding partner Zdk2 to achieve light-controlled protein sequestration [27]:

Construct Design: Fuse the protein of interest to AsLOV2 (dark state binder) and its interaction target to Zdk2 (light-sensitive binder). Alternatively, for sequestration approaches, fuse one component to AsLOV2 and the other to Zdk2.

Transfection and Expression: Introduce constructs into target cells using appropriate transfection methods (e.g., lipofection, electroporation). Allow 24-48 hours for protein expression before experimentation.

Light Control: Apply 450 nm blue light (∼1-5 mW/mm²) to dissociate Zdk2 from AsLOV2. Return to darkness to allow reassociation. The relatively fast dark recovery of AsLOV2 (τ ≈ 80s) enables reversible control on the minute timescale [22] [27].

Functional Validation: Assess system functionality through fluorescence imaging (if using fluorescent protein fusions), biochemical assays for downstream signaling events, or phenotypic readouts relevant to the controlled proteins.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of LOV Domains

This computational approach elucidates the structural dynamics of LOV photoactivation [27]:

System Preparation: Obtain the dark-state crystal structure of AsLOV2 (PDB 2V1A). Insert the Cys-FMN adduct from the light-state structure (PDB 2V1B) to simulate the photoactivated state.

Simulation Parameters: Parameterize the Cys-FMN adduct appropriately. Perform molecular dynamics simulations using 4 fs timesteps for extended durations (≥7 μs) to capture complete Jα helix unfolding events.

Analysis: Monitor Jα helix stability through root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculations and secondary structure assessment. Identify key residue interactions (e.g., between N414 and Q513) that mediate allosteric signaling from the FMN binding pocket to the Jα helix [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of blue-light optogenetic tools requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential components for experiments utilizing channelrhodopsins or LOV domains:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Blue-Light Optogenetics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | AAV5-CaMKII-ChR2-GFP, AAV5-CaMKII-Chronos-GFP [24] | Efficient neuronal expression of optogenetic tools |

| Cell-Type Specific Promoters | CaMKII (excitatory neurons), Synapsin (pan-neuronal) [24] [4] | Target opsin expression to specific cell populations |

| Light Sources | 470 nm LED/laser, 593 nm laser [24] | Activate blue-light tools or red-shifted controls |

| Light Delivery | 200 μm optical fibers [24] | Deliver light to target tissues in vivo |

| Chromophores | All-trans-retinal [25] | Essential cofactor for channelrhodopsin function |

| LOV Binding Partners | Zdk2 [27] | Engineered binding partners for LOV domain systems |

| Validation Reagents | Anti-NeuN antibodies, DAPI [24] | Verify expression patterns and cellular localization |

Comparative Strategic Implementation

Tool Selection Guidelines

Choosing between channelrhodopsins and LOV domains depends primarily on the biological process being studied and the required mode of control:

Select channelrhodopsins (ChR2 or Chronos) when:

- Direct control of membrane potential and action potential firing is desired

- Millisecond-scale temporal precision is required

- Studying neural circuit function or excitability

- Minimal interference with intracellular signaling is preferred

Select LOV domains when:

- Controlling intracellular signaling pathways or protein-protein interactions

- Manipulating enzymatic activities or transcription factor function

- Subcellular localization control is needed

- Direct plasma membrane depolarization would be disruptive

Within the channelrhodopsin family, ChR2 serves as a robust, well-characterized option for general stimulation purposes at low-to-medium frequencies (≤ 40 Hz), while Chronos provides superior performance for high-frequency stimulation (> 40 Hz) and applications requiring precise temporal patterning of activity [26] [24]. For LOV domains, AsLOV2 offers the advantage of relatively rapid dark recovery (seconds to minutes), enabling reversible control on physiologically relevant timescales, while VVD and FKF1 provide more persistent light-state populations for sustained pathway activation [22].

Integration with Red-Light Systems

While blue-light tools offer excellent kinetics and sensitivity, their limited tissue penetration compared to red-light systems presents challenges for deep tissue applications [1]. Strategic approaches to overcome this limitation include:

- Fiber optic implantation for direct light delivery to deep brain structures [24]

- Bioluminescent optogenetics using luciferase-luciferin systems to generate light intracellularly [4]

- Multi-color experiments combining blue-light actuators with red-shifted sensors or actuators for simultaneous monitoring and manipulation [23] [24]

For in vivo applications targeting deep brain structures, red-shifted channelrhodopsins like Chrimson (activated by ~590 nm light) may be preferable due to superior tissue penetration, though they typically exhibit slower kinetics than blue-light tools [1] [24].

Key Experimental Evidence and Validation

Channelrhodopsin Performance Validation

Critical evidence supporting the differential performance of ChR2 and Chronos comes from direct comparative studies. In the auditory brainstem implant model, both opsins were expressed in the cochlear nucleus via viral-mediated gene transfer, and neural responses were recorded in the inferior colliculus [26]. This approach demonstrated that Chronos maintained higher response synchrony at stimulation rates where ChR2 performance degraded, establishing its superiority for high-frequency applications [26].

Similarly, in vivo cortical stimulation experiments revealed that ChR2, Chronos, and Chrimson engage distinct patterns of network activity despite similar expression levels, with significant differences in γ-band power modulation [24]. These findings highlight that opsin kinetics influence not only single-cell responses but also network-level dynamics, an important consideration for systems neuroscience applications.

LOV Domain Mechanism Validation

The mechanistic understanding of LOV domain function has been advanced through interdisciplinary approaches combining molecular dynamics simulations with experimental validation. Simulations predicting the key roles of residues N414 and Q513 in signal transduction from the FMN binding pocket to the Jα helix were validated through site-directed mutagenesis, time-resolved infrared spectroscopy, and cellular optogenetic experiments [27]. This comprehensive approach demonstrated that hydrogen bonding interactions between these residues mediate the allosteric coupling underlying light-induced Jα helix unfolding [27].

Visual Guide to Blue-Light Tool Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate key mechanisms and experimental workflows for blue-light optogenetic tools:

Channelrhodopsin Activation Mechanism

LOV Domain Photoswitching Mechanism

In Vivo Optogenetic Workflow

Optogenetics, the revolutionary method for controlling cellular functions with light, has become an indispensable tool in neuroscience and biological research. A significant evolution in this field is the shift from blue-light-operated systems to red-light-activated tools, a transition driven by the superior physical properties of longer wavelength light. Red and near-infrared (NIR) light, spanning approximately 630-710 nm and 710-1400 nm respectively, experience significantly less scattering and absorption in biological tissues compared to blue light (~430-500 nm) [1] [28]. This inherent advantage translates to deeper tissue penetration—red light penetrates skin 4-5 mm versus just ~1 mm for blue light—enabling less invasive manipulation of deep brain structures in living animals [28]. Furthermore, red light carries a lower risk of phototoxicity due to its reduced energy transfer compared to higher-energy blue wavelengths, and it minimizes activation of endogenous photosensitive proteins, thereby reducing background noise [28].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three leading red-light optogenetic systems: the channelrhodopsin Chrimson, various phytochrome-based systems, and biliverdin-dependent fluorescent proteins. We objectively evaluate their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal tool for their specific applications.

Comparative Performance of Red-Light Systems

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of major red-light optogenetic tools and actuators, providing a basis for direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Red-Light Optogenetic Tools and Fluorescent Proteins

| Tool Name | Type / Class | Peak Excitation (nm) | Peak Emission (nm) | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrimson/ChrimsonR [29] | Cation Channelrhodopsin | ~590 [29] [30] | N/A | Fast kinetics, high temporal precision [30]. Improved trafficking (IvfChr variant) [30]. | Neuronal excitation, vision restoration (RGC targeting) [7] [30]. |

| vfChrimson [30] | Cation Channelrhodopsin | N/A | N/A | Ultrafast kinetics (off-rate τ = 5.6 ± 0.3 ms) [30]. | High-frequency neuronal stimulation [30]. |

| BphP1-PpsR2/Q-PAS [31] | Bacterial Phytochrome | 740-780 (NIR) [31] | N/A | Activated by NIR light; uses endogenous biliverdin [31]. | Protein dimerization, control of receptor tyrosine kinases [31]. |

| iRFP670 [32] | Biliverdin-dependent FP | 643 [32] | 670 [32] | Molecular Brightness: 205% of iRFP713; pKa=4.0 [32]. | Multicolor in vivo imaging [32]. |

| iRFP713 [32] | Biliverdin-dependent FP | 690 [32] | 713 [32] | Molecular Brightness: Baseline (100%); pKa=4.5 [32]. | Whole-body imaging, tumor tracking [32]. |

| iRFP720 [32] | Biliverdin-dependent FP | 702 [32] | 720 [32] | Molecular Brightness: 93% of iRFP713; pKa=4.5 [32]. | Multicolor in vivo imaging with spectral unmixing [32]. |

Detailed System Profiles and Experimental Data

Chrimson Family of Red-Shifted Channelrhodopsins

The Chrimson family represents a pinnacle of engineering for neuronal excitation. Derived from Chlamydomonas noctigama, Chrimson and its variant ChrimsonR (K176R mutation) are activated at a peak of ~590 nm, offering a significant red-shift over earlier channelrhodopsins like ChR2 (470 nm) [29] [30]. A key performance differentiator is kinetics. While standard Chrimson is effective, the vfChrimson variant is engineered for ultrafast operation, with a channel off-rate time constant of 5.6 ± 0.3 ms, enabling high-frequency stimulation up to the intrinsic limits of neurons [30]. A critical practical challenge is poor membrane trafficking. To address this, researchers developed IvfChr, a membrane-trafficking optimized vfChrimson, which ensures sufficient protein expression at the cell membrane for robust photocurrents [30].

Experimental evidence from slice electrophysiology in the hippocampus demonstrates that neurons expressing IvfChr can generate time-locked action potentials in response to red light pulses (635 nm) at high frequencies [30]. Furthermore, in vivo validation in the facial motor nucleus of the brainstem showed that IvfChr activation by red light successfully triggered large-amplitude vibrissa movement, confirming its efficacy in driving behavior [30].

A major application for Chrimson is in vision restoration. GenSight Biologics' GS030 therapy combines an AAV vector encoding ChrimsonR with light-stimulating goggles, targeting retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. This approach is currently in Phase 1/2 clinical trials (PIONEER, NCT03326336) [7].

Phytochrome-Based Actuators and Dimerizers

Phytochromes are a widespread family of photoreceptors that use a covalently bound tetrapyrrole (bilin) chromophore [33] [31]. They photoconvert between a red-absorbing Pr state and a far-red-absorbing Pfr state, a process involving Z/E photoisomerization of the bilin 15/16 double bond [33]. A critical distinction exists between phytobilin-containing phytochromes (e.g., plant and cyanobacterial phytochromes) and the more widespread biliverdin (BV)-containing phytochromes, which include bacterial phytochromes (BphPs) [33]. Research indicates these two classes have distinct photochemical mechanisms and Pfr state structures, as revealed by circular dichroism spectroscopy and chromophore substitution experiments [33].

A prominent optogenetic application is the BphP1-PpsR2 system. The bacterial phytochrome BphP1 interacts with its partner protein PpsR2 in a light-dependent manner, with activation in the 740-780 nm NIR range [31]. This system is particularly valuable because it can utilize endogenous biliverdin in mammals as a chromophore and is spectrally compatible with blue-light systems [31]. An engineered version using a synthetic partner protein called Q-PAS overcomes limitations of the natural PpsR2, such as large size and tendency to oligomerize [31]. This system has been used to control receptor tyrosine kinases by fusing the catalytic domain to the photosensitive core of BphP1, allowing reversible kinase activation with far-red/NIR light [31].

Diagram: Simplified signaling pathway of the BphP1 optogenetic system.

Biliverdin-Dependent Near-Infrared Fluorescent Proteins (iRFPs)

Bacterial phytochromes have also been engineered as Near-Infrared Fluorescent Proteins (iRFPs) for deep-tissue imaging. These tools are derived from the PAS and GAF domains of BphPs and efficiently incorporate biliverdin IXα (BV), a ubiquitous mammalian chromophore, eliminating the need for external chromophore supply in many applications [32]. A significant achievement in this area is the development of a palette of spectrally distinct iRFPs, including iRFP670, iRFP682, iRFP702, iRFP713, and iRFP720, with emission maxima covering 670 nm to 720 nm [32].

Key performance advantages include high brightness in mammalian cells; for example, iRFP670 shows 119% of the effective brightness of iRFP713 in HeLa cells without exogenous BV [32]. They also exhibit relatively fast folding and chromophore incorporation (half-time of 4.5-5 hours), comparable to EGFP, and stability across a pH range of 4 to 8 [32]. When evaluated in a tissue phantom model with optical properties matching mouse muscle, iRFPs demonstrated superior signal-to-autofluorescence ratios for deep-tissue imaging compared to conventional far-red FPs like E2-Crimson and mNeptune [32]. This palette enables multicolor in vivo imaging in living mice using spectral unmixing techniques [32].

Diagram: Experimental workflow for developing and validating iRFPs.

Key Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Protocol for Dual-Color Neuronal Control with Zip-IvfChr

A sophisticated application of red-light tools involves creating a co-expression system for dual-color control. The following protocol, adapted from research on the Zip-IvfChr system, details how to achieve high-frequency activation with red light and simultaneous suppression with blue light [30].

- Molecular Construct Design: Create a single expression vector encoding both IvfChr (trafficking-improved vfChrimson) and a fast blue-light-activated anion channel like ZipACR (e.g., I151T or I151V mutants). The expression of both opsins should be linked, often using a P2A self-cleaving peptide sequence, to ensure co-expression in the same neuronal population.

- Neuronal Transduction: Deliver the construct into target neurons using a suitable method, most commonly adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes with neuronal tropism (e.g., AAV2/1, AAV2/9, or AAV2/Retro). Stereotactic injection allows for region-specific transduction in the brain.

- Slice Electrophysiology Validation: After allowing 2-4 weeks for opsin expression, prepare acute brain slices. Perform whole-cell patch-clamp recordings on transduced neurons.

- Red-Light Excitation Test: Apply 1-5 ms pulses of 635 nm red light at varying frequencies (e.g., 10-40 Hz). A valid preparation will show time-locked action potentials with high fidelity at all frequencies.

- Blue-Light Suppression Test: While the neuron is firing action potentials (e.g., via current injection), apply 5-20 ms pulses of 470 nm blue light. A successful system will show complete suppression of firing during the blue light pulse, with recovery of activity within <5 ms after pulse termination.

- In Vivo Behavioral Assay: To confirm system functionality in a live animal, express Zip-IvfChr in a well-defined motor pathway (e.g., the facial motor nucleus controlling vibrissa movement). Implant an optical fiber above the target region. Application of red light pulses should elicit robust vibrissa movement, while blue light pulses of the same duration and intensity should produce no movement.

Chromophore Analysis in Phytochromes

Understanding the molecular basis of phytochrome function often requires analyzing the chromophore's role. The following methodology is used to distinguish between different phytochrome classes [33].

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the recombinant phytochrome photosensory core (PAS-GAF-PHY domains) from a heterologous system like E. coli.

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Record CD spectra of the holoprotein in its Pr state and after saturating irradiation to generate the Pfr state (or Pr/Pfr photoequilibrium). The sign of the CD signal for the red absorbance band is diagnostic of the D-ring facial disposition: negative for D-αf and positive for D-βf [33].

- Chromophore Substitution: Reconstitute the apoprotein with semisynthetic bilin monoamides. This involves removing the native chromophore and incubating the apoprotein with synthetic analogs that have specific modifications, such as amidated propionate side chains.

- Functional Assay: Measure the absorption spectra and photoconversion capability of the semisynthetic holoproteins. Altered photochemical properties in specific monoamide derivatives indicate the functional role of individual chromophore propionate side chains in the protein context, helping to elucidate mechanistic differences between phytochrome subclasses [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Resources for Red-Light Optogenetics Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Tools & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AAV Vectors | Gene delivery vehicle for in vivo opsin expression. | Serotypes AAV2/1, AAV2/9, AAV2/Retro for neuronal targeting; AAV2.7m8 for retinal targeting [7] [30]. |

| Biliverdin IXα (BV) | Endogenous chromophore for BphPs and iRFPs. | Critical for function; supplied endogenously in mammals, but can be added exogenously (e.g., 5-25 µM) to boost signals in cell culture [32] [31]. |

| Channelrhodopsin Variants | Light-gated ion channels for neuronal depolarization. | ChrimsonR (stable expression), vfChrimson (ultrafast kinetics), IvfChr (improved trafficking) [29] [7] [30]. |

| Anion Channelrhodopsins (ACRs) | Light-gated chloride channels for neuronal silencing. | ZipACR (I151T/V mutants for fast kinetics); used with Chrimson for blue-light suppression [30]. |

| Light-Stimulating Goggles | Wearable device for vision restoration therapies. | Amplifies ambient light and projects pulses at specific wavelengths (e.g., amber for ChrimsonR) onto the retina [7]. |

| Optical Fibers & Implants | Light delivery for in vivo brain stimulation. | Precision light delivery to deep brain structures; diameter and NA determine light output area and divergence. |

| Fluorescent Protein Palette | Spectrally distinct FPs for multicolor imaging. | iRFP670, iRFP682, iRFP702, iRFP713, iRFP720 for multiplexed in vivo imaging [32]. |

| Phytochrome Dimerizer Systems | Light-controlled protein-protein interaction. | BphP1-PpsR2/Q-PAS system for NIR-controlled dimerization and pathway activation [31]. |

The ability to independently control distinct neural populations is indispensable for deciphering the complex functional architecture of the brain. Multicolor optogenetics represents a transformative approach that enables simultaneous interrogation of multiple neural pathways with high spatiotemporal precision. This paradigm leverages optogenetic constructs with distinct wavelength sensitivities, allowing investigators to bypass limitations imposed by spatial overlap of tools through spectral separation [34]. Unlike traditional single-pathway manipulations, multicolor approaches permit researchers to study convergent inputs, synaptic integration, and spike-timing-dependent plasticity mechanisms in their native circuit contexts [34].

A fundamental challenge in this domain lies in achieving truly independent control of neural populations. While an ideal system would feature opsins with completely discrete activation spectra, current biological tools invariably exhibit some degree of spectral crosstalk, particularly in the blue light range [34] [5]. This comprehensive guide compares the leading strategies and technologies for parallel neural circuit interrogation, providing objective performance data and detailed methodologies to inform experimental design in basic neuroscience and drug development research.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Challenges

The Spectral Crosstalk Problem

The core challenge in multicolor optogenetics stems from the intrinsic molecular properties of microbial opsins. Despite extensive protein engineering efforts, all currently known red-shifted actuators exhibit non-negligible blue-light sensitivity [34]. This phenomenon occurs because the retinal chromophore—the light-absorbing cofactor present in all channelrhodopsins—natively absorbs blue light wavelengths [5]. Consequently, when blue light is delivered to activate a blue-shifted opsin (e.g., ChR2, Chronos), it inevitably also activates red-shifted opsins (e.g., Chrimson, C1V1) expressed in a separate neuronal population [34] [5].

The practical implication of this spectral crosstalk is the potential for erroneous interpretation of neural circuit functions when supposedly independent manipulations inadvertently affect multiple populations. The degree of crosstalk is not constant but varies multidimensionality based on experimental parameters including stimulus wavelength, irradiance, duration, and the specific opsin variants selected [34].

Light Penetration and Tissue Considerations

Beyond spectral separation, wavelength selection carries significant implications for light delivery in vivo. Red light (∼630–710 nm) demonstrates superior tissue penetration compared to blue light (∼430–500 nm) due to reduced scattering and absorption by endogenous molecules like hemoglobin and melanin [1]. This physical advantage means red light can illuminate deeper brain structures with less power requirement, potentially reducing thermal tissue damage [1]. However, this benefit must be balanced against the more limited toolkit of red-shifted opsins and their inherent crosstalk susceptibility.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Light Wavelengths Used in Optogenetics

| Wavelength | Tissue Penetration | Scattering | Absorption by Hemoglobin | Typical Opsins Activated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~405 nm (Violet) | Low (~1 mm) | High | High | ChR2(H134R), Chronos |

| ~470 nm (Blue) | Low (~1 mm) | High | High | ChR2(H134R), Chronos, GtACR2 |

| ~590 nm (Amber) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Chrimson, C1V1 |

| ~635 nm (Red) | High (4-5 mm) | Low | Low | ChrimsonR, vfChrimson, ReaChR |

Strategic Approaches to Multicolor Control

Parameter Titration Strategy

The most straightforward approach to minimizing crosstalk involves systematically limiting stimulation parameters to ranges that do not cross-activate opsins [34]. This method requires preliminary characterization in control systems where only the red opsin is expressed.

Experimental Protocol:

- Express the red-shifted opsin alone in a neural population

- Systematically test blue light stimulation across a matrix of irradiances and pulse durations

- Identify the maximum blue light exposure that does not elicit spiking in the red opsin population

- Apply these limits in subsequent experiments with both opsins expressed [34]

Performance Considerations: This approach preserves precise temporal control over independent neuron populations, making it suitable for studying spike-timing-dependent plasticity and synaptic integration [34]. A significant limitation is that population-derived blue light limits may provide inadequate excitation when blue opsin expression levels are low, potentially rendering some experiments uninterpretable [34]. Using more blue-shifted wavelengths (e.g., 405 nm instead of 470 nm) can reduce crosstalk but further diminishes blue opsin activation efficiency [34].

Sequential Inactivation Strategy

This innovative approach exploits the differential inactivation kinetics of opsins. Pioneered by Hooks et al., the method uses prolonged red light stimulation to forcibly inactivate the red opsin-expressing population before immediately applying blue light stimulation [34].

Experimental Protocol:

- Apply long-duration (50–250 ms) red light to activate and subsequently inactivate red opsin-expressing axons

- Immediately deliver blue light stimulation while the red opsin population remains refractory

- Any postsynaptic response during blue stimulation can be attributed solely to blue opsin activation [34]