CRISPR Revolution: Decoding the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition in Development and Disease

This article synthesizes the latest advances in applying CRISPR technologies to study the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition (MZT), a fundamental reprogramming event in early embryonic development.

CRISPR Revolution: Decoding the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition in Development and Disease

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advances in applying CRISPR technologies to study the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition (MZT), a fundamental reprogramming event in early embryonic development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of MZT, detail innovative CRISPR screening methodologies—including the use of CRISPR-RfxCas13d for maternal RNA knockdown—and address critical troubleshooting aspects such as off-target effects and structural variations. Furthermore, we provide a comparative analysis of CRISPR tools, highlight their validation in vertebrate models like zebrafish and medaka, and discuss the growing clinical implications of these findings for genetic medicine and therapeutic development.

The MZT Blueprint: Establishing Fundamental Principles and Key Regulatory Networks

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents the most profound handover of developmental control in the life of an organism. This conserved process marks the switch from reliance on maternally deposited RNAs and proteins in the oocyte to the activation of the embryonic genome [1]. The MZT encompasses two tightly coupled major events: the extensive degradation of maternal transcripts and the initiation of transcription from the zygotic genome, known as zygotic genome activation (ZGA) [2]. For decades, the MZT has been a focal point of developmental biology, but recent advances in genome-editing technologies, particularly CRISPR-based systems, have revolutionized our ability to dissect its molecular mechanics with unprecedented precision. This whitepaper details the core principles of the MZT, the experimental frameworks leveraging CRISPR for its study, and the emerging therapeutic implications of this research.

Core Concepts: Deconstructing the MZT

The Component Processes

The MZT is not a single event but a cascade of interconnected processes that are precisely coordinated in time and space.

- Maternal RNA Degradation: The oocyte is loaded with maternal messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that drive the initial stages of development. A critical step in the MZT is the active clearance of a large subset of these transcripts. This clearance is mediated by sequences in the 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) of the maternal mRNAs and is executed by factors including microRNAs. For instance, in zebrafish, the microRNA miR-430 is expressed at the onset of ZGA and promotes the deadenylation and degradation of several hundred maternal mRNAs [3].

- Zygotic Genome Activation (ZGA): This is the defining event where the transcriptionally silent embryonic genome is awakened. The zygotic genome begins to transcribe its own set of genes, which will thereafter control development [3]. The activation of this new genetic program requires overcoming epigenetic silencing and assembling the transcription machinery.

- Cell Cycle Remodeling: Early embryonic cell cycles are characterized by rapid, synchronous divisions lacking gap phases. The MZT coincides with a major remodeling of the cell cycle, introducing gap phases and leading to asynchronous, slower divisions, a period often referred to as the midblastula transition (MBT) [1].

Timing and Conservation Across Species

The timing of major ZGA is species-specific, though the overarching principles of the MZT are conserved across metazoans. The table below summarizes the key stages.

Table 1: Timing of Zygotic Genome Activation in Model Organisms

| Organism | Typical ZGA Stage | Key Regulators and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Late 2-cell stage [4] | Involves multiple waves of activation; pioneering transcription factors initiate the first wave [3]. |

| Human | Major activation at 8-cell stage [5] | Paternal genome initiates ZGA; primate-specific factors like ZNF675 play a role [5]. |

| Zebrafish | Around MBT (10th cell cycle) [6] | microRNAs like miR-430 are critical for maternal mRNA clearance [3]. |

| Xenopus (Frog) | Midblastula stage (MBT) [3] | Timing is influenced by the nucleocytoplasmic ratio [3]. |

| Drosophila (Fly) | Around cycle 14 [1] | Characterized by a major activation wave and abbreviated early transcripts. |

A landmark study using human parthenogenetic (maternal-only) and androgenetic (paternal-only) embryos revealed a surprising parental asymmetry in human ZGA. The paternal genome extensively initiates ZGA at the 8-cell stage, while the maternal genome's activation is significantly delayed until the morula stage, suggesting human ZGA is "initiated from the paternal genome" [5].

The CRISPR Toolkit for MZT Research

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 and its derivative technologies has provided a versatile toolkit for functional gene analysis and epigenetic manipulation, making it ideal for probing the complex regulatory networks of the MZT.

Key CRISPR Technologies and Their Applications

Table 2: CRISPR-Based Tools for Investigating MZT

| CRISPR Technology | Mechanism of Action | Application in MZT Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 (Nuclease) | Creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, repaired by NHEJ (causing indels) or HDR (using a template) [7]. | - Generate knockout models to study gene function [7].- Correct disease-causing mutations in early embryos [7]. |

| CRISPR Inhibition (dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-MECP2) | Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains silences target genes [7]. | Study the effect of repressing specific ZGA transcription factors or epigenetic regulators. |

| CRISPR Activation (dCas9-VPR, dCas9-P300) | dCas9 fused to activator domains (e.g., VPR, P300) upregulates gene expression [7]. | Artificially activate ZGA genes to test their sufficiency in driving development. |

| Epigenome Editing (dCas9-DNMT3a, dCas9-TET1) | dCas9 targeted to promoters and fused to DNA methyltransferases (e.g., DNMT3a) or demethylases (e.g., TET1) to alter DNA methylation [7]. | Investigate the role of specific DNA methylation changes in regulating ZGA and imprinting [7]. |

| CRISPR-RfxCas13d | Targets and degrades RNA rather than DNA, knocking down mRNA transcripts [6]. | Perform high-throughput maternal RNA screens to identify regulators of MZT without altering the genome [6]. |

Experimental Workflows

A typical CRISPR-based experiment to investigate a ZGA gene involves a defined workflow, from target design to phenotypic analysis.

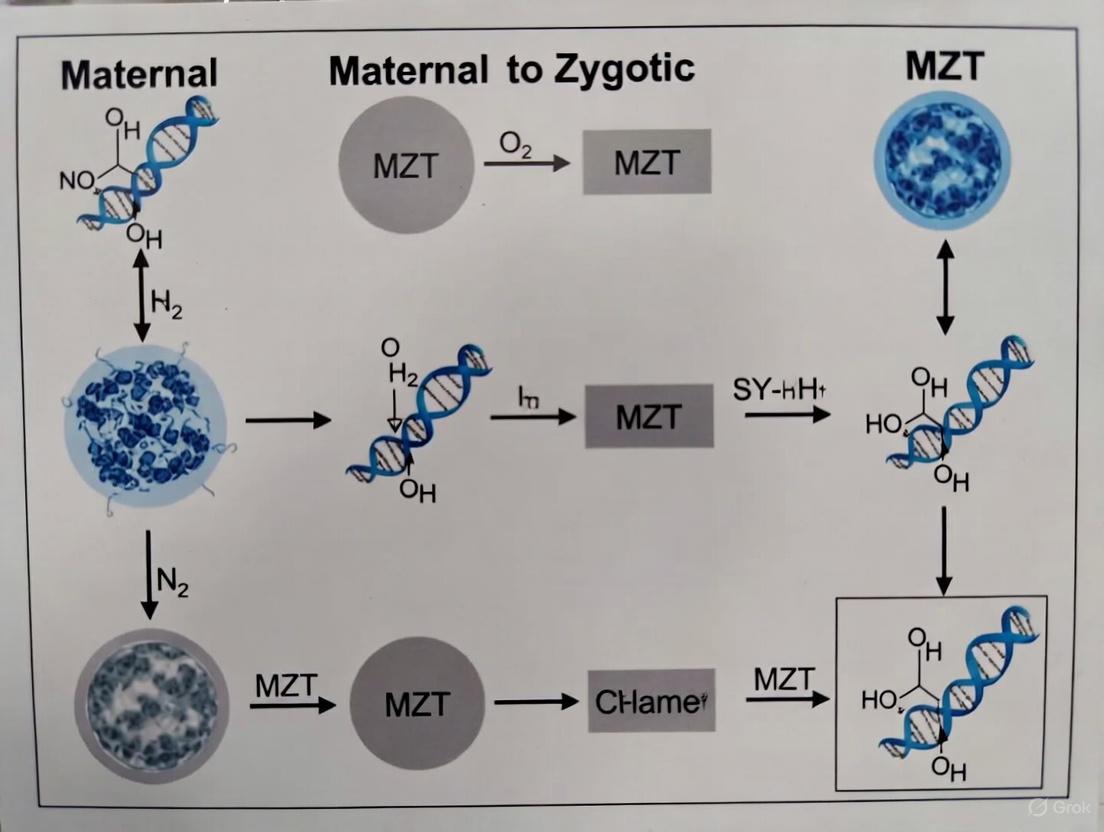

Diagram 1: Functional Gene Analysis via CRISPR-Cas9.

For loss-of-function studies targeting maternal mRNAs, the CRISPR-RfxCas13d system offers a powerful, DNA-free alternative.

Diagram 2: Maternal Gene Screen via CRISPR-RfxCas13d.

Research Reagent Solutions for MZT Studies

A successful MZT research program relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for CRISPR-based investigations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Mediated MZT Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function and Importance | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle for in vivo CRISPR components. Naturally accumulates in the liver, enabling efficient liver editing. Allows for potential re-dosing [8]. | Used in clinical trials for systemic delivery of CRISPR therapies targeting liver-expressed genes (e.g., for hATTR amyloidosis) [8]. |

| Cell-Permeable Anti-CRISPR Proteins | A safety switch to rapidly deactivate Cas9 after editing is complete, reducing off-target effects and improving clinical safety [9]. | The LFN-Acr/PA system uses an anthrax toxin component to ferry anti-CRISPR proteins into human cells within minutes, boosting specificity up to 40% [9]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Nanoparticles | A biodegradable polymer nanoparticle for delivering gene-editing agents (e.g., PNAs and ssDNA donors) to early embryos. Penetrates the zona pellucida without microinjection [10]. | Used for embryonic gene editing in mice, achieving high editing rates (~94% in blastocysts) with no detected off-target effects and normal embryonic development [10]. |

| dCas9-Epigenetic Effector Fusions | Targeted manipulation of the epigenome (e.g., DNA methylation) without altering the underlying DNA sequence, crucial for studying epigenetic reprogramming during MZT [7]. | dCas9-DNMT3a and dCas9-TET1 used to silence or activate endogenous reporters, respectively. Applied to study genomic imprinting in oocytes [7]. |

| Auxin-Inducible Degradation (AID) System | Allows for inducible, targeted degradation of endogenous proteins to study the function of maternal protein pools during the MZT [7]. | Efficiently induced degradation of maternal proteins in the ovary and early embryo of Drosophila [7]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Mediated ZGA Gene Knockout

This protocol outlines the key steps for investigating the function of a ZGA gene in a mouse model using CRISPR-Cas9.

Materials and Reagents

- CRISPR Components: Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease 3NLS (IDT) or similar.

- gRNAs: Chemically modified synthetic sgRNAs with high efficiency and specificity scores for the target ZGA gene.

- Animal Model: C57BL/6J or other appropriate strain.

- Microinjection Setup: Inverted microscope with micromanipulators, piezo-drill unit.

- Embryo Culture Media: KSOM or M16 medium, equilibrated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Procedure

gRNA Design and Validation:

- Design two to four gRNAs targeting early exons of the target ZGA gene.

- Validate cleavage efficiency in vitro using a DNA plasmid substrate or in a cell-based model.

Preparation of Injection Mix:

- Prepare a working solution containing 50 ng/μL Cas9 protein and 25 ng/μL of each sgRNA in nuclease-free microinjection buffer.

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes) to remove any particulates that could clog the injection needle.

Zygote Collection and Microinjection:

- Collect zygotes from superovulated females at the pronuclear stage.

- Using a piezo-driven micromanipulator, perform cytoplasmic microinjection of the CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

- After injection, wash zygotes and place into pre-equilibrated culture droplets.

Embryo Culture and Phenotypic Analysis:

- Culture embryos in vitro through the MZT (to the 2-cell, 8-cell, and blastocyst stages).

- Record and compare the developmental rates and morphology of injected embryos versus control embryos.

- A significant developmental arrest or delay at the stage of expected ZGA function indicates a potential critical role for the targeted gene.

Genotypic and Molecular Confirmation:

- From a subset of phenotypically abnormal embryos, extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify the target region by PCR and perform Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing to confirm the presence of indels.

- For the remaining embryos, process for RNA extraction to analyze transcriptomic changes via RT-qPCR or RNA-seq, confirming disruption of the target gene and its downstream effects.

Troubleshooting and Safety

- Low Editing Efficiency: Optimize gRNA design and use high-purity, chemically modified sgRNAs to enhance stability and efficiency.

- High Embryo Lethality: Titrate the concentration of the RNP complex to minimize toxicity. Ensure all buffers and media are of the highest quality.

- Off-Target Effects: Employ the cell-permeable LFN-Acr/PA system to rapidly inhibit Cas9 after the editing window [9]. Always use computational prediction tools to select gRNAs with minimal off-target potential and validate using unbiased methods like whole-genome sequencing.

The integration of advanced genome-editing tools with classical embryology has dramatically accelerated our understanding of the MZT. We have moved from descriptive observations to functional, mechanistic dissections of how the zygotic genome is awakened. The discovery of parental asymmetry in human ZGA and the ability to conduct high-throughput functional screens for maternal effectors are direct results of this technological synergy. Looking forward, the refinement of CRISPR systems—with a strong emphasis on safety, precision, and the ability to manipulate the epigenome—will not only answer fundamental biological questions but also pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies. Correcting genetic mutations during the embryonic stage, as demonstrated in proof-of-concept studies, holds the potential to prevent devastating genetic diseases, positioning MZT and CRISPR research at the forefront of the next revolution in medicine.

The Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition (MZT) represents a cornerstone event in early embryonic development, encompassing two fundamental processes: the clearance of maternally deposited mRNAs and the large-scale activation of the zygotic genome, accompanied by extensive epigenetic reprogramming [11]. This transition is conserved across metazoans and is essential for transferring developmental control from the oocyte to the embryo proper. Dysregulation of MZT is a significant cause of early developmental arrest in human embryos, with profound implications for assisted reproduction and understanding developmental disorders [11] [12].

The emergence of CRISPR-based technologies has revolutionized the functional study of MZT. Moving beyond traditional gene knockout techniques, tools like CRISPR-RfxCas13d enable precise, efficient degradation of maternal RNAs without triggering the innate immune responses associated with earlier methods like morpholinos [13]. Furthermore, the application of CRISPR in screening and epigenetic profiling has unveiled novel regulatory layers, providing unprecedented insights into the complex interplay between RNA clearance, epigenetic states, and zygotic genome activation (ZGA). This technical guide synthesizes current methodologies and discoveries, framing them within the broader context of MZT research powered by CRISPR.

Degradation Pathways and Kinetics

Maternal mRNA clearance is not a uniform event but a meticulously orchestrated process involving sequential pathways. These are broadly classified into the Maternal (M)-decay pathway, which operates before ZGA using maternally inherited factors, and the Zygotic (Z)-decay pathway, which depends on transcripts produced after ZGA [11]. In human preimplantation embryos, transcriptomic analyses have revealed distinct clusters of maternal mRNAs that are degraded at specific stages, illustrating the precise timing of these pathways [11].

Table 1: Classification of Maternal mRNA Degradation During Human MZT

| Cluster | Degradation Pattern | Proposed Pathway | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster I | Degraded from Germinal Vesicle (GV) to zygote stage; stable thereafter. | M-decay | Shorter 3'UTRs [11] |

| Cluster II | Degraded from the zygote to the 8-cell stage. | Z-decay | Longer 3'UTRs, enriched for cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements (CPEs) [11] |

| Cluster III | Continuously degraded from the GV to the 8-cell stage. | Combined M- and Z-decay | - |

| Cluster IV | Stable during MZT. | - | Resistant to degradation |

The kinetics of this clearance are tuned to the species' developmental tempo. Research utilizing the QUANTA computational framework on time-series RNA-seq data from zebrafish, frog, mouse, and human embryos has shown that degradation onset and rates generally align with the speed of development. However, a subset of transcripts displays species-specific kinetic tuning, governed by distinct usage of destabilizing motifs in their 3'UTRs [14].

Key Regulators of RNA Clearance

The execution of maternal mRNA decay relies on a suite of conserved trans-acting factors and cis-acting elements:

- BTG4/CCR4-NOT: This complex is a central player in the M-decay pathway, mediating deadenylation and decay of maternal mRNAs prior to ZGA. Its defect is linked to human embryo arrest [11].

- TUT4/7 (Terminal Uridylyl Transferases): These enzymes facilitate 3'-oligouridylation of mRNAs, promoting degradation and are key effectors of the Z-decay pathway [11].

- microRNAs: The miR-430 family in zebrafish (and its equivalents in other species) is transcribed during ZGA and accelerates the decay of hundreds of maternal mRNAs [13] [14].

- YAP1-TEAD4: This transcriptional module activates the expression of Z-decay factors like TUT4/7 upon ZGA, thereby licensing the second wave of maternal transcript clearance [11].

Recent advances have also highlighted the role of RNA modifications, such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A), in regulating MZT. In mice, maternally inherited m6A-modified transcripts show enhanced stability, and the knockdown of m6A readers like Ythdc1 and Ythdf2 using CRISPR-Cas13d disrupts preimplantation development, underscoring the critical function of the epitranscriptome in this transition [15].

Chromatin State Dynamics and Zygotic Genome Activation

The activation of the zygotic genome is preceded and accompanied by extensive remodeling of the embryonic epigenome. Key events include global DNA demethylation and subsequent re-establishment of methylation patterns, as well as the acquisition of activating histone marks at promoters and enhancers.

High-resolution mapping of histone modifications in zebrafish embryos using CUT&RUN has revealed a sophisticated regulatory logic. Two distinct subclasses of enhancers have been identified, distinguished by the presence of H3K4me2 [16]:

- H3K4me2-positive enhancers are epigenetically bookmarked by DNA hypomethylation, allowing them to recapitulate gamete activity in the embryo independently of the pioneer factors Nanog, Pou5f3, and Sox19b (NPS).

- H3K4me1-only enhancers largely rely on NPS pioneering for their de novo activation during development.

This finding demonstrates that parallel enhancer activation pathways collaborate to drive the transcriptional reprogramming to pluripotency.

Table 2: Key Histone Modifications and Their Roles in MZT (Profiled by CUT&RUN in Zebrafish)

| Histone Modification | Type | Primary Genomic Location | Function in MZT |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me1 | Methylation | Enhancers | Marks one subclass of enhancers; often requires NPS for activation [16] |

| H3K4me2 | Methylation | Enhancers | Distinguishes a second subclass of enhancers; often NPS-independent, bookmarked by DNA hypomethylation [16] |

| H3K4me3 | Methylation | Promoters | Associated with active transcription [16] |

| H3K27ac | Acetylation | Active Enhancers/Promoters | Marks active regulatory elements; crucial for ZGA. Reduced upon Bckdk depletion [13] [16] |

| H3K56ac | Acetylation (globular core) | Enhancers | Marks active enhancers [16] |

Linking Epigenetics and RNA Decay

The integration of multiple omics technologies—including ATAC-seq (for chromatin accessibility), RNA-seq, and SLAM-seq (for measuring nascent transcription)—has been instrumental in linking epigenetic states to transcriptional outcomes during MZT. For instance, the knockdown of bckdk mRNA, a novel regulator identified via CRISPR screening, led to reduced H3K27ac levels and impaired miR-430 processing, thereby disrupting both ZGA and maternal mRNA clearance [13]. This exemplifies the tight coupling between epigenetic regulation and the RNA decay machinery.

CRISPR-Based Methodologies for MZT Research

Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-RfxCas13d Maternal RNA Screening

The following protocol, adapted from a zebrafish kinase/phosphatase screen, details how to perform a loss-of-function screen for maternal RNAs [13].

1. Target Selection and gRNA Design:

- Selection Criteria: Focus on genes with high mRNA abundance in the oocyte and high translation levels at the onset of ZGA. The proof-of-principle study selected 49 genes encoding kinases and phosphatases [13].

- gRNA Design: Design three chemically synthesized and optimized guide RNAs (gRNAs) per target mRNA to maximize knockdown efficacy and mitigate off-target effects.

2. Riboribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Assembly:

- Purify recombinant RfxCas13d protein.

- Complex the purified RfxCas13d protein with a pool of the synthesized gRNAs to form the RNP complex.

3. Embryo Microinjection:

- Microinject the pre-assembled RNP complex directly into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Include control groups injected with RfxCas13d protein only and uninjected embryos.

4. Phenotypic Screening and Validation:

- Monitor injected embryos for developmental phenotypes (e.g., epiboly delays) over the first 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf).

- For candidates of interest, validate knockdown efficiency (e.g., via RNA-seq, achieving a median of 92% mRNA reduction in the cited study) and analyze downstream effects on the transcriptome (RNA-seq), chromatin (ATAC-seq, CUT&RUN for histone marks), and/or proteome (phospho-proteomics) [13].

Visualizing a CRISPR-Cas13d Screening Workflow

The diagram below outlines the key steps in a CRISPR-RfxCas13d maternal RNA screening pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Based MZT Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in MZT Research |

|---|---|---|

| RfxCas13d Protein | RNA-targeting Cas protein; induces cleavage of target RNAs when complexed with a gRNA. | Targeted degradation of maternal mRNAs; enables high-efficiency knockdown screens in vertebrate embryos [13]. |

| Optimized gRNAs | Short guide RNAs that direct RfxCas13d to complementary RNA sequences. | Specific and efficient target mRNA knockdown. Using multiple gRNAs per target increases efficacy [13]. |

| CUT&RUN Kits | Low-input chromatin profiling technique for mapping histone modifications and transcription factor binding. | Epigenetic landscape profiling during early development (e.g., H3K4me, H3K27ac) [16]. |

| SLAM-seq | Time-resolved sequencing method for measuring nascent RNA synthesis and degradation. | Directly quantifying ZGA dynamics and maternal mRNA decay kinetics [13]. |

| ADAR-based RNA Editors | Systems (e.g., REPAIR, LEAPER) for programmable A-to-I RNA editing. | Reversible manipulation of RNA sequences to study function without genomic DNA alteration [17]. |

| scMulti-omic Platforms | Single-cell technologies combining RNA-seq and ATAC-seq or BS-seq. | Profiling genome activation and epigenetic reprogramming in individual cells of pre-implantation embryos [12]. |

Integrated Regulatory Pathways in MZT

The core regulatory events of MZT are not linear but form an interconnected network. The following diagram synthesizes the key relationships between maternal factors, epigenetic reprogramming, zygotic genome activation, and RNA clearance, integrating findings from recent CRISPR studies.

Pathway Explanation: The diagram illustrates the core regulatory network of MZT. Maternal factors, including pioneer factors like NPS and novel regulators like Bckdk discovered via CRISPR screening, initiate the process by driving epigenetic reprogramming (e.g., establishing H3K27ac and H3K4me2 marks) and directly promoting Zygotic Genome Activation (ZGA) [13] [16]. A key mechanistic insight from CRISPR studies is the Bckdk-Phf10 axis: Bckdk-mediated phosphorylation of the chromatin remodeler Phf10 influences H3K27ac levels, thereby regulating ZGA. Bckdk also impacts maternal RNA clearance by promoting miR-430 processing [13]. Successful ZGA leads to the production of zygotic factors (e.g., miR-430, TUT4/7), which in turn execute the large-scale clearance of maternal mRNAs. This clearance is essential for dismantling the maternal regulatory program and fully enabling zygotic control, thus completing the transition.

The integration of CRISPR-based screening and multi-omic profiling has dramatically accelerated the deconstruction of MZT, moving from phenomenological observation to mechanistic understanding. These tools have enabled the identification of novel regulators like Bckdk and have clarified the existence of parallel epigenetic pathways ensuring robust ZGA. The experimental protocols and resources detailed in this guide provide a framework for researchers to systematically investigate the complex interplay of RNA clearance and epigenetic reprogramming.

Future research will likely focus on further elucidating the molecular details of these novel pathways, exploiting the reversibility of RNA editing for therapeutic exploration, and applying single-cell multi-omic technologies to dissect cell-fate heterogeneity during this critical developmental window. As CRISPR tools continue to evolve in specificity and deliverability, their power to unravel the fundamental logic of life's beginnings—and to address clinical challenges in human reproduction—will only increase.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents a fundamental reprogramming event in animal development, encompassing zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and coordinated degradation of maternal components. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the key regulators—pioneer transcription factors, chromatin remodeling complexes, and post-translational modifications—that orchestrate this critical developmental window. We examine how CRISPR-based technologies have revolutionized the functional dissection of these regulators, providing unprecedented mechanistic insights. The integration of advanced genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic approaches has revealed complex regulatory networks that reset the embryonic genome to totipotency and launch subsequent developmental programs, with significant implications for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition is an evolutionarily conserved process in animal development where control of embryogenesis shifts from maternally-deposited factors to the newly formed zygotic genome [18] [19]. This transition involves two coordinated events: massive degradation of maternal RNAs and proteins, and activation of the zygotic genome [18]. The MZT reprograms terminally differentiated gametes to a totipotent state, enabling the zygotic genome to direct all subsequent developmental processes [18] [15].

The application of CRISPR-based technologies has dramatically accelerated our understanding of MZT regulation [20]. While early studies were largely descriptive, newer genome editing tools enable functional genetic screening and precise manipulation of the embryonic genome and epigenome [13] [20]. The development of single-cell and low-input sequencing methods has further revolutionized the field by allowing detailed profiling of the transcriptome, transcription-factor binding, and chromatin architecture despite limited biological material [18]. Advanced live-imaging techniques now permit real-time visualization of transcription dynamics during early development [18].

Pioneering Transcription Factors in Genome Activation

Pioneer transcription factors (PTFs) constitute a specialized class of transcriptional regulators that possess the unique ability to bind condensed chromatin and initiate chromatin opening, thereby establishing competence for gene expression during ZGA [21]. These factors function as molecular pioneers that scan compacted chromatin landscapes and initiate developmental gene activation programs.

Key Pioneer Factor Families

Research across model organisms has identified several core PTF families essential for MZT:

Nanog, Pou5f3 (Oct4), and SoxB1 (Sox2): In zebrafish, these three maternal factors act as widespread regulators of ZGA, controlling approximately 80% of zygotic genes [19]. Loss of function leads to complete developmental arrest, underscoring their critical role in developmental reprogramming [19].

GATA family factors: Studies in mammalian systems demonstrate that GATA3 can pioneer new enhancers through recruitment of collaborating factors like AP-1 and chromatin remodelers including SWI/SNF complexes [21]. This pioneering activity requires chromatin remodeling and establishes local chromatin architecture permissive for transcription.

Mechanisms of Action

Pioneer factors employ multiple mechanisms to activate the silent genome:

Chromatin Scanning: PTFs scan compacted chromatin through DNA shape recognition and specific motif binding [21].

Recruitment of Collaborating Factors: PTFs recruit non-pioneer transcription factors (e.g., GATA3 recruits AP-1) to enhance binding specificity and stability [21].

Chromatin Remodeler Recruitment: PTFs recruit ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers like SWI/SNF complexes to nucleosome repositioning [21].

Enhancer Establishment: PTF binding initiates enhancer formation marked by histone acetylation and other activation marks [21].

Table 1: Pioneer Transcription Factors in MZT Regulation

| Factor | Model System | Function in MZT | Molecular Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanog | Zebrafish | Activates ~80% of zygotic genes; essential for ZGA | SoxB1, Pou5f3 [19] |

| Pou5f3 (Oct4) | Zebrafish | Coordinates chromatin accessibility and ZGA | Nanog, SoxB1 [19] |

| SoxB1 (Sox2) | Zebrafish | Promotes transcriptional competence during ZGA | Nanog, Pou5f3 [19] |

| GATA3 | Mammalian cells | Pioneers new enhancers; recruits chromatin remodelers | AP-1, SWI/SNF complexes [21] |

Diagram 1: Pioneer Factor Mechanism in Chromatin Remodeling

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in ZGA

Chromatin remodeling complexes play indispensable roles in ZGA by reconfiguring nucleosome architecture to establish transcriptionally permissive chromatin states. The SWI/SNF family of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers represents a particularly crucial regulator of embryonic genome activation.

SWI/SNF Complex Diversity and Function

The mammalian SWI/SNF complex exists in multiple specialized variants with distinct developmental functions:

Complex Composition: SWI/SNF complexes comprise up to 15 subunits encoded by 29 genes, forming tissue-specific assemblies with unique functions [22]. Mammals can form up to 1400 different SWI/SNF complex combinations across various tissues [22].

Subcomplex Specialization: Three primary variants include cBAF (canonical BAF), ncBAF (non-canonical BAF), and PBAF (Polybromo-associated BAF), each with distinct subunit composition and genomic targeting [22].

Developmental Essentiality: SWI/SNF subunits are frequently mutated in neurodevelopmental disorders and cancers, highlighting their dosage-sensitive roles in development [22]. Heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in subunits like ARID1B cause protein destabilization and impaired SWI/SNF activity despite the presence of a wild-type allele [22].

Regulatory Mechanisms Controlling SWI/SNF Activity

Recent CRISPR screening approaches have identified novel mechanisms regulating SWI/SNF complex assembly and function:

Assembly Chaperones: MLF2 (Myeloid Leukemia Factor 2) promotes SWI/SNF assembly and chromatin binding [22]. Rapid MLF2 degradation reduces chromatin accessibility at sites requiring high SWI/SNF binding levels.

Post-transcriptional Control: RBM15 (RNA binding motif 15), part of the m6A writer complex, controls m6A modifications on specific SWI/SNF mRNAs to regulate subunit protein levels [22]. m6A misregulation causes overexpression of core subunits, leading to incomplete complex assembly.

Phosphoregulation: Phf10 (also known as Baf45a), a PBAF-complex subunit, requires phosphorylation for proper function during ZGA [13]. Bckdk-mediated phosphorylation of Phf10 regulates its activity in chromatin remodeling during early development.

Table 2: Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in MZT Regulation

| Complex/Subunit | Regulatory Mechanism | Function in MZT | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWI/SNF (BAF) complexes | ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling | Creates accessible chromatin at enhancers and promoters | CRISPR screen identified assembly regulators [22] |

| MLF2 | Chaperone-mediated complex assembly | Promotes SWI/SNF chromatin binding and activity | Rapid degradation reduces chromatin accessibility [22] |

| RBM15 | m6A mRNA modification of SWI/SNF subunits | Maintains subunit stoichiometry for proper assembly | m6A misregulation causes incomplete complexes [22] |

| Phf10/Baf45a | Phosphorylation-dependent activity | Regulates PBAF complex function during ZGA | Constitutively phosphorylated Phf10 rescues Bckdk depletion [13] |

Post-Translational and Post-Transcriptional Regulation

Beyond transcription factor networks and chromatin remodeling, post-translational and post-transcriptional mechanisms provide crucial regulatory layers that control the timing and fidelity of MZT.

Protein Phosphorylation in ZGA Regulation

Protein phosphorylation represents a key post-translational mechanism regulating MZT progression:

Bckdk Kinase Function: CRISPR-RfxCas13d screening in zebrafish identified Bckdk (branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase) as a novel post-translational regulator of MZT [13]. Bckdk depletion causes epiboly defects, ZGA deregulation, H3K27ac reduction, and impaired miR-430 processing.

Phosphoproteome Remodeling: Bckdk knockdown reduces phosphorylation of multiple targets, including the chromatin remodeling factor Phf10/Baf45a [13]. Constitutively phosphorylated Phf10 rescues developmental defects caused by bckdk depletion, establishing a direct functional link.

Non-Mitochondrial Roles: While Bckdk has established mitochondrial functions in amino acid catabolism, its cytosolic localization enables phosphorylation of nuclear targets like Phf10 during early development [13].

RNA Modification Dynamics

RNA modifications, particularly N6-methyladenosine (m6A), serve as important post-transcriptional regulators during MZT:

m6A Dynamics: In mice, m6A modifications can be maternally inherited or de novo gained during ZGA [15]. Maternally inherited m6A+ transcripts show enhanced translation and elevated protein abundance.

Functional Regulators: CRISPR/Cas13d-mediated screening identified Ythdc1 and Ythdf2 as m6A readers essential for preimplantation development [15]. Ythdc1 binds maternal m6A+ transcripts and participates in RNA stability regulation.

Coordination with Degradation: m6A works in concert with specialized decay mechanisms, including miR-430-mediated clearance in zebrafish, to orchestrate maternal transcript elimination [18] [13].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

The dissection of MZT regulators has been accelerated by sophisticated experimental approaches that enable precise functional interrogation during early development.

CRISPR-Based Screening Platforms

CRISPR technologies have enabled systematic functional screening during early embryogenesis:

CRISPR-RfxCas13d Screening: This RNA-targeting CRISPR system enables efficient maternal mRNA knockdown in vertebrate models where RNAi is ineffective [13]. The approach involves:

- Design of optimized guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting maternal transcripts

- Co-injection of purified RfxCas13d protein and gRNAs into 1-cell stage embryos

- Phenotypic screening for developmental defects

- Transcriptomic and proteomic validation of hits

CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Screening: DNA-editing CRISPR screens identify essential chromatin regulators through negative selection [22] [23]. For example, SETDB1 was identified as essential for metastatic uveal melanoma cell survival through chromatin regulator screening [23].

Epigenome Editing Reporters: Engineered reporter cell lines (e.g., ZF-DT-Nkx2.9 mESCs) enable screening for regulators of SWI/SNF-dependent gene activation through inducible recruitment systems [22].

Multi-Omics Integration

Comprehensive profiling approaches provide systems-level views of MZT regulation:

Nascent Transcriptomics: Metabolic labeling with 4-thio-UTP or azide-modified uridine analogs enables specific detection of zygotic transcripts amid abundant maternal RNAs [18].

Epigenomic Mapping: ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and DNA methylation profiling reveal chromatin dynamics during ZGA [18] [13]. Single-cell methods further resolve heterogeneous chromatin states.

Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Analysis: Low-input proteomic techniques quantify protein abundance and phosphorylation changes during MZT [13] [15].

Diagram 2: CRISPR Screening Workflow for MZT Regulators

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MZT Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-RfxCas13d system | Maternal mRNA knockdown | Specific RNA degradation in embryos | Target 49 kinases/phosphatases in zebrafish [13] |

| dCas9-epigenetic editors | Chromatin manipulation | Targeted DNA methylation/demethylation | Imprinting control region editing [23] |

| ZF-DT-Nkx2.9 reporter | SWI/SNF activity screening | Live/dead reporter for remodeler function | CRISPR screen for SWI/SNF regulators [22] |

| MS2-MCP RNA tagging | Live imaging of transcription | Real-time visualization of transcription | Track gene activation during ZGA [18] |

| 4-thio-UTP labeling | Nascent transcript capture | Metabolic labeling of zygotic transcripts | Profile early zygotic transcriptome [18] |

| SLIM-seq | m6A mapping | Genome-wide m6A profiling | Define m6A dynamics during mouse MZT [15] |

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Integration of quantitative findings across studies reveals consistent patterns in MZT regulator function:

Table 4: Quantitative Effects of MZT Regulator Perturbation

| Regulator | Perturbation Method | Phenotypic Severity | Transcriptomic Impact | Key Molecular Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanog/Pou5f3/SoxB1 | Multispecies morpholino knockdown | Complete developmental arrest | ~80% of zygotic genes not activated [19] | Loss of chromatin accessibility |

| Bckdk | CRISPR-RfxCas13d knockdown | Severe epiboly delay (>67% affected) | Downregulation of pure zygotic genes [13] | Reduced H3K27ac; impaired Phf10 phosphorylation |

| MLF2 | Rapid degradation in mESCs | Not reported | Subset of SWI/SNF targets affected | Reduced chromatin accessibility at high-occupancy sites [22] |

| Ythdc1 | CRISPR/Cas13d knockdown in mouse zygotes | Impaired preimplantation development | Altered stability of maternal m6A+ transcripts [15] | Disrupted maternal mRNA clearance |

| Phf10 | CRISPR-RfxCas13d knockdown | Epiboly defects | ZGA deficiency [13] | Compromised PBAF complex function |

The integration of CRISPR-based functional genomics with multi-omics profiling has dramatically advanced our understanding of MZT regulation. Pioneer transcription factors, chromatin remodeling complexes, and post-translational modifications form interconnected networks that orchestrate the precisely timed transition from maternal to zygotic control. Key emerging principles include the dosage sensitivity of chromatin regulators, the importance of RNA modifications in coordinating maternal transcript clearance, and the critical role of phosphorylation in regulating chromatin remodeler activity.

Future research directions will likely focus on achieving single-molecule resolution of chromatin changes during ZGA, engineering more precise epigenetic editing tools, and leveraging mechanistic insights to improve reproductive medicine and mRNA-based therapeutics. The continued refinement of CRISPR technologies will further enable systematic dissection of this fundamental developmental window, with potential applications in regenerative medicine and therapeutic genome editing.

Evolutionary Conservation of MZT Mechanisms Across Metazoan Models

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents a fundamental reprogramming event during early embryogenesis, marking the shift from maternal to embryonic control of development. This process encompasses two critical events: degradation of maternally-provided transcripts and proteins, and activation of the zygotic genome (ZGA). Despite the vast evolutionary distance between metazoans, core MZT mechanisms exhibit remarkable conservation from basal metazoans to vertebrates. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on MZT conservation, highlighting key molecular players across species and presenting novel CRISPR-based methodologies that enable unprecedented investigation of this crucial developmental window. Understanding the evolutionary conservation of MZT mechanisms provides critical insights for developmental biology, regenerative medicine, and therapeutic development.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition is an essential phase in early animal development where the fertilized egg transitions from relying on maternal gene products deposited in the oocyte to activating transcription from its own genome. During this critical period, the embryo must achieve two major objectives: (1) selectively degrade a specific subset of maternal RNAs and proteins, and (2) initiate precise transcription from the zygotic genome [24]. The MZT represents the first significant developmental hurdle for the newly formed organism, and its proper execution is crucial for subsequent embryonic patterning and cell differentiation.

All animals undergo some form of MZT, though the timing and specific regulatory mechanisms show both conservation and variation across the metazoan phylogeny [24]. In Drosophila, the MZT occurs during the syncytial blastoderm stage, with a minor wave of ZGA beginning at nuclear cycle 8 and a major wave at nuclear cycle 14 [24]. In zebrafish, ZGA occurs in two waves, with the major wave beginning around 2 hours post-fertilization [13]. Even early-branching metazoans like sponges, ctenophores, and placozoans undergo this fundamental transition, though their cellular complexity and regulatory networks differ substantially from bilaterians [25].

The evolutionary conservation of MZT mechanisms provides a powerful framework for understanding both the core principles of embryonic reprogramming and the adaptations that underlie diverse developmental strategies. This technical guide explores the conserved elements of MZT across metazoan models, details cutting-edge CRISPR methodologies for its investigation, and presents quantitative comparisons of MZT characteristics across species.

Core MZT Mechanisms: Conserved Principles Across Metazoans

Maternal RNA Clearance: Shared Degradation Pathways

The clearance of maternal RNAs is a tightly regulated process essential for developmental progression. Research across model systems has revealed striking conservation in the molecular machinery governing maternal transcript degradation:

RNA-binding proteins: In Drosophila, the RNA-binding protein Smaug (Smg) is responsible for destabilizing approximately two-thirds of maternally encoded mRNAs during the MZT [24]. Smg recruits the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex to target transcripts, leading to polyA-tail shortening and subsequent degradation. Similarly, proteins like Brain Tumor (Brat) and Pumilio (Pum) recruit the same complex to initiate mRNA decay [24].

MicroRNA-mediated degradation: In zebrafish, the microRNA miR-430 plays a central role in maternal transcript clearance [13]. This pathway is evolutionarily conserved, with related miRNA families serving analogous functions in different organisms: the mir-309 cluster in Drosophila, and mir-430 and mir-427 in zebrafish and Xenopus, respectively [24]. These miRNAs specifically target maternal rather than zygotic RNAs for degradation, demonstrating the precision of this regulatory system.

Translational control: The transition from translational repression to RNA degradation is regulated by conserved kinase complexes. In Drosophila, the Pan Gu (Png) kinase complex reverses translational inhibition by repressors like Pum exclusively during the oocyte-to-embryo transition [24]. Png directly phosphorylates proteins involved in translation, including Pum, Trailer Hitch (Tral), and MEI31B, shifting the balance from repression to degradation.

Zygotic Genome Activation: Chromatin Remodeling and Pioneer Factors

Zygotic genome activation requires dramatic chromatin reorganization and the action of pioneer transcription factors. Conserved mechanisms include:

Pioneer factors: Across metazoans, pioneer factors play essential roles in initiating ZGA by binding closed chromatin and making it accessible for transcription. In zebrafish, factors like Nanog, SoxB1, and Pou5f3 are crucial for ZGA [13]. In Drosophila, the pioneer factor Zelda is required for proper deposition of Polycomb modifications and activation of the zygotic genome [26].

Chromatin remodeling: The establishment of appropriate chromatin states during ZGA is essential for developmental progression. In Drosophila, broad domains of Polycomb-modified chromatin (H3K27me3 and H2Aub) are rapidly established across the genome during ZGA [26]. Similarly, in zebrafish, H3K27ac emerges as a crucial epigenetic mark for triggering ZGA [13]. These conserved chromatin modifications help establish the transcriptional programs that guide subsequent development.

Coordination with cell cycle changes: In many organisms, ZGA coincides with changes in the cell cycle. In Drosophila, the major wave of ZGA at nuclear cycle 14 occurs alongside dramatic lengthening of the division cycle and cellularization [24]. This coordination suggests conserved mechanisms linking cell cycle regulation and transcriptional activation.

Proteome Remodeling: Degradation of Maternal Proteins

During the MZT, a subset of the maternal proteome is degraded through conserved mechanisms:

Ubiquitin-proteasome system: In Drosophila, degradation of maternal proteins is partially dependent on the E2 conjugating enzyme Marie Kondo (Kdo) and the E3 CTLH ligase complex, which promote degradation of translational repressors such as ME31B, Cup, and Tral [24]. Similarly, removal of Smg at the end of the MZT requires the E3 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex [24].

Regulatory coordination: As with RNA clearance, degradation of maternal proteins is coordinated with other MZT events. In Drosophila, upregulation of Kdo protein is impeded in png mutants, demonstrating coordination between kinase signaling and protein degradation [24].

Table 1: Conservation of Core MZT Mechanisms Across Metazoan Models

| MZT Mechanism | Drosophila | Zebrafish | Early-Branching Metazoans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal RNA Decay | Smaug, miR-309 cluster, CCR4-NOT complex | miR-430, codon optimality | RNA-binding proteins (sponges) |

| Zygotic Activation | Zelda, H3K27me3 domains at NC14 | Nanog, SoxB1, Pou5f3, H3K27ac | Limited data on pioneer factors |

| Maternal Protein Clearance | Kdo/CTLH complex, SCF complex for Smg | Not detailed in sources | Not described in sources |

| Coordination with Cell Cycle | NC14: cycle lengthening, cellularization | Coordinated with epiboly | Not described in sources |

| Chromatin Remodeling | Polycomb domain establishment | Chromatin accessibility changes | Variable regulatory complexity |

MZT Across the Metazoan Phylogeny: Comparative Analysis

The comparison of MZT mechanisms across diverse metazoans reveals both deeply conserved features and lineage-specific adaptations:

Basal Metazoans: Sponges, Ctenophores, and Placozoans

Single-cell RNA sequencing of non-bilaterian animals has provided insights into the evolution of cell type specification and early development:

Sponges (Amphimedon queenslandica): Sponges possess diverse cell types including choanocytes, pinacocytes, and archaeocytes, each with distinct transcriptional signatures [25]. Sponge choanocytes express specific RNA-binding proteins like MBNL, Bruno2 and Nanos, while pinacocytes express Pumilio and components of the actin contractility apparatus [25]. Sponges show intermediate complexity in their transcriptional regulators, with 209-232 transcription factors and 99-134 chromatin modifiers/remodelers [25].

Ctenophores (Mnemiopsis leidyi): Ctenophores exhibit greater cell type diversity than sponges and placozoans, which is associated with lower specificity of promoter sequences and the existence of distal regulatory elements [25]. This suggests that more complex genome regulation may be required for diverse cell type repertoires.

Placozoans (Trichoplax adhaerens): Despite their morphological simplicity, placozoans contain multiple types of peptidergic cells, revealing previously unknown molecular complexity [25]. In both placozoans and poriferans, sequence motifs in promoters are predictive of cell type-specific programs [25].

Drosophila melanogaster: A Detailed Model of MZT Regulation

Drosophila has served as a foundational model for understanding MZT mechanisms:

Coordinated events: The Drosophila MZT involves precisely coordinated processes including lengthening of the division cycle, degradation of maternally deposited products, transcriptional activation of the zygotic genome, and reorganization of embryonic chromatin [24].

Temporal progression: After fertilization, the zygote undergoes rapid syncytial divisions. The first 9 nuclear cycles last about 8 minutes each, with gradual lengthening thereafter [24]. ZGA occurs gradually with a minor wave at approximately nuclear cycle 8 and a major wave at nuclear cycle 14 [24].

Polycomb domain establishment: In Drosophila, H3K27me3 accumulates adjacent to prospective Polycomb Response Elements beginning in nuclear cycle 14, with patterns indicative of nucleation followed by spreading [26]. The pioneer factor Zelda is required for proper deposition of H3K27me3 and H2Aub at a subset of Polycomb domains [26].

Zebrafish: Vertebrate MZT Regulation

Zebrafish provides insights into vertebrate-specific aspects of MZT:

Post-translational regulation: Recent CRISPR screening in zebrafish has identified Bckdk as a novel post-translational regulator of MZT [13]. Bckdk depletion causes epiboly defects, ZGA deregulation, H3K27ac reduction, and partial impairment of miR-430 processing [13].

Phospho-regulatory networks: Phospho-proteomic analysis following Bckdk depletion revealed reduced phosphorylation of various proteins during MZT, including the chromatin remodeling factor Phf10/Baf45a [13]. This highlights the importance of phosphorylation networks in vertebrate embryonic development.

Conservation across teleosts: Bckdk depletion also induces early development perturbation and downregulation of pure zygotic genes in medaka, indicating conservation of its role in MZT among teleosts [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of MZT Characteristics Across Species

| Species | Genome Size | Intergenic Region Length | Transcription Factors | Chromatin Modifiers | ZGA Timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphimedon queenslandica (sponge) | 166 Mb | 0.6 Kb | 209-232 | 99-134 | Not specified |

| Mnemiopsis leidyi (ctenophore) | 156 Mb | 2 Kb | 209-232 | 99-134 | Not specified |

| Trichoplax adhaerens (placozoan) | 98 Mb | 2.7 Kb | 209-232 | 99-134 | Not specified |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | NC8 (minor), NC14 (major) |

| Danio rerio (zebrafish) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 64-cell stage (2 hpf) |

CRISPR Technologies for MZT Research: Methodological Advances

The development of CRISPR-based technologies has revolutionized the study of MZT by enabling precise manipulation of gene function during early development:

CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Editing in Early Embryos

CRISPR-Cas9 has been widely adopted for generating targeted mutations in oocytes and early embryos:

Mechanism: The CRISPR-Cas9 system uses a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to target DNA containing a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [20]. Cas9 generates double-strand breaks approximately 3 bp upstream from the PAM, which are repaired primarily through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) [20].

Applications: CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to generate homozygous loss-of-function animals, correct disease-associated mutations, and modify genes in large animal models [20]. In zebrafish, "crispants" generated through CRISPR-Cas9 have enabled rapid investigation of maternal-effect genes by inducing high-frequency biallelic editing of the germ line [20].

Evaluation methods: qEva-CRISPR provides a quantitative method for evaluating CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency that detects all mutation types, including point mutations and large deletions [27]. This method allows simultaneous analysis of multiple targets and off-target sites, providing comprehensive editing assessment [27].

CRISPR-RfxCas13d for Targeted RNA Knockdown

CRISPR-RfxCas13d represents a powerful approach for studying maternal RNA contributions:

Mechanism: RfxCas13d is an RNA-targeting CRISPR enzyme that can be programmed with guide RNAs to specifically degrade target mRNAs [13]. Unlike DNA-editing approaches, RfxCas13d knocks down RNA without altering genomic sequence.

Maternal screening applications: In zebrafish, CRISPR-RfxCas13d has been used to perform maternal knockdown screens targeting mRNAs encoding protein kinases and phosphatases [13]. This approach identified Bckdk as a novel regulator of MZT, demonstrating the technology's utility for functional genomics in early development.

Advantages: CRISPR-RfxCas13d enables specific, efficient, and cost-effective degradation of maternal RNAs, overcoming limitations of previous technologies like morpholinos which can trigger toxicity and off-target effects [13].

Epigenome Editing with dCas9 Fusion Proteins

Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to effector domains enables precise epigenetic manipulation:

Transcriptional regulation: dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., dCas9-VPR) or repressors (e.g., dCas9-KRAB) allows targeted regulation of gene expression without altering DNA sequence [20].

Epigenetic editing: Fusion of dCas9 to epigenetic modifiers like DNMT3a (for DNA methylation) or TET1 (for DNA demethylation) enables precise manipulation of the epigenome [20]. In mammalian oocytes and embryos, dCas9-DNMT3a has been used to edit genomic imprinting regions [20].

Chromatin visualization: dCas9 fused to fluorescent proteins enables visualization of specific genomic loci in live cells, providing insights into nuclear organization during early development [20].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for CRISPR-Based MZT Studies. This workflow outlines key stages in designing and implementing CRISPR-based experiments to study MZT mechanisms across species.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MZT Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Applications in MZT Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Genome editing via DNA double-strand breaks | Gene knockout, lineage tracing, mutation correction in early embryos |

| CRISPR-RfxCas13d | RNA knockdown without genomic alteration | Maternal RNA screens, studying post-transcriptional regulation |

| dCas9-Epigenetic Editors | Targeted epigenetic modification | Studying chromatin dynamics during ZGA, imprinting regulation |

| qEva-CRISPR | Quantitative evaluation of editing efficiency | Measuring INDEL frequency, assessing on-target/off-target effects |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Transcriptome profiling at single-cell resolution | Cell type identification, transcriptional dynamics during MZT |

| ChIP-seq | Genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions | Histone modification analysis, transcription factor binding |

| ATAC-seq | Assessment of chromatin accessibility | Mapping open chromatin regions during ZGA |

| SLAM-seq | Measurement of RNA synthesis and degradation rates | Kinetic analysis of maternal RNA decay and zygotic transcription |

The evolutionary conservation of MZT mechanisms across metazoans underscores the fundamental nature of this developmental transition. From sponges to vertebrates, shared principles emerge: the regulated clearance of maternal products, the activation of the zygotic genome through pioneer factors and chromatin remodeling, and the precise coordination of these events with cell cycle changes. However, species-specific adaptations reflect diverse developmental strategies and evolutionary histories.

CRISPR technologies have dramatically advanced our ability to interrogate MZT mechanisms with unprecedented precision. CRISPR-Cas9 enables targeted genome editing, CRISPR-RfxCas13d facilitates maternal RNA screening, and dCas9-based epigenetic editors allow manipulation of the chromatin landscape. These tools, combined with single-cell omics approaches, provide powerful methodologies for dissecting MZT across species.

Future research directions should include comprehensive comparative studies of MZT in early-branching metazoans, systematic analysis of post-translational modifications during embryonic reprogramming, and development of improved CRISPR tools with enhanced specificity and efficiency. Understanding the conserved principles of MZT not only advances fundamental knowledge of animal development but also informs therapeutic strategies for regenerative medicine and assisted reproduction.

Diagram 2: Conserved Molecular Regulation of MZT. This diagram illustrates key molecular interactions and regulatory relationships conserved across metazoan species during maternal-to-zygotic transition.

CRISPR Toolbox for MZT: From Gene Editing to Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents a critical developmental milestone during which control of embryonic development shifts from maternally-inherited components to the zygotic genome. This process involves two fundamental events: degradation of maternal mRNAs and zygotic genome activation (ZGA). Recent advances in CRISPR-based technologies have revolutionized our ability to interrogate the molecular mechanisms governing MZT with unprecedented precision. This technical guide explores the application of CRISPR-Cas9 and next-generation editors—including Cas12, Cas13, DNA base editors, and prime editors—for functional genetic studies during oogenesis and early embryogenesis. We provide a comprehensive framework for employing these tools to dissect the complex regulatory networks underlying MZT, with detailed protocols, safety considerations, and resource guidance for the research community.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition encompasses the finely orchestrated sequence of events where maternally deposited transcripts and proteins are degraded while the embryonic genome becomes transcriptionally active [7]. This transition involves critical processes including maternal mRNA elimination, epigenetic reprogramming, and zygotic genome activation [7]. The chromatin architecture during early embryonic stages exists in a uniquely relaxed state characterized by totipotency, with mammalian cleavage-stage embryos undergoing the most dramatic chromosomal reprogramming events [7].

The application of CRISPR technologies to MZT studies faces unique challenges and opportunities. The limited biological material available from oocytes and early embryos necessitates highly efficient and precise genome editing tools. Furthermore, the dynamic epigenetic landscape during early development requires tools capable of probing chromatin states and transcriptional regulation without permanently altering the genomic sequence in most cases.

CRISPR Toolbox for MZT Research

Core CRISPR Nucleases

CRISPR-Cas9

The CRISPR-Cas9 system constitutes the foundational technology for most genome editing applications in early embryos. The system comprises two components: a guide RNA (gRNA) for target recognition and the Cas9 endonuclease for DNA cleavage [28]. The mechanism involves the gRNA spacer sequence annealing to the target DNA, with Cas9 generating a blunt-ended double-strand break (DSB) approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence [28]. DSB repair occurs primarily through either the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, resulting in insertions or deletions (indels), or the higher-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway [28].

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Systems for MZT Studies

| CRISPR System | Target | PAM Sequence | Cleavage Pattern | Key Applications in MZT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 (SpCas9) | DNA | 3'-NGG-5' [28] | Blunt ends [29] | Gene knockouts, large deletions, epigenetic editing |

| Cas12a | DNA | 3'-TTTV-5' [29] | Staggered ends [29] | Multiplexed gene regulation, DNA manipulation |

| Cas13 | RNA | Depends on subtype [29] | RNA cleavage [29] | Maternal transcript degradation studies, transient knockdowns |

| Base Editors | DNA | Varies by Cas domain | Single-base changes without DSBs [29] | Modeling point mutations, epigenetic modifications |

| Prime Editors | DNA | Varies by Cas domain | All single-base changes, small insertions/deletions [29] | Precise genome manipulation without donor templates |

CRISPR-Cas12

Cas12 nucleases represent a valuable alternative to Cas9 for certain MZT applications. Unlike Cas9, Cas12 enzymes utilize a single RuvC-like nuclease domain that cleaves both DNA strands, generating staggered ends in regions distal to the PAM sequence [29]. This distinct cleavage pattern can influence repair outcomes and efficiency. Some Cas12 variants recognize T-rich PAM sequences (TTTV), expanding the targetable genomic space compared to the NGG PAM requirement of standard SpCas9 [29].

CRISPR-Cas13

The Cas13 system targets RNA rather than DNA, making it particularly suitable for studying maternal mRNA degradation during MZT without permanently altering the genome. Cas13 can be programmed to cleave specific transcripts, enabling researchers to dissect the functional consequences of eliminating particular maternal mRNAs [29]. Fusion of catalytically inactive dCas13 to adenosine deaminases (ADAR) enables precise RNA base editing (A-to-I), offering a transient, reversible manipulation of gene expression [29].

Advanced Genome Editing Tools

DNA Base Editors

Base editors facilitate precise single-nucleotide changes without inducing double-strand breaks, making them valuable for modeling point mutations and studying their functional impact during early development. These systems typically consist of a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease fused to a deaminase enzyme that converts one base to another (e.g., cytidine deaminase for C•G to T•A conversions) [29]. The absence of DSBs favors higher editing efficiency and reduces unintended indels.

Prime Editors

Prime editors represent the most precise CRISPR-based editing technology, capable of installing all possible single-base changes, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring donor DNA templates or causing DSBs [29]. The system utilizes a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that specifies both the target locus and the desired edit. This technology offers unprecedented precision for studying the functional consequences of specific genetic variants during MZT.

Epigenetic Editors

Catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) serves as a programmable DNA-binding platform that can be fused to various epigenetic modifiers, including DNMT3a for DNA methylation, TET1 for DNA demethylation, and various histone modifiers [7]. These tools enable researchers to manipulate the epigenetic landscape during early development to investigate how epigenetic states regulate MZT processes, including ZGA.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Strategic Planning for MZT Studies

When designing CRISPR experiments for MZT research, several unique considerations must be addressed. The limited quantity of starting material necessitates highly efficient editing systems. For studies focusing on maternal effect genes, interventions must occur during oogenesis or very early embryogenesis. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of the MZT requires precise temporal control over editing activities.

Temporal considerations are paramount in MZT studies. Researchers must decide whether to target maternal components (requiring editing during oogenesis) or zygotic components (targetable after ZGA). For maternal effect genes, microinjection of CRISPR components into zygotes may be insufficient, as the maternal transcripts and proteins are already present. In such cases, editing the maternal germline through conditional approaches in oocytes may be necessary.

gRNA Design and Validation

Effective gRNA design is crucial for successful MZT experiments. The process begins with identifying unique target sequences within the gene of interest that meet PAM requirements for the selected Cas enzyme. Several computational tools exist for gRNA design and off-target prediction, including Cas-OFFinder, CasOT, and others [29]. For MZT studies, special attention should be paid to potential off-target effects in highly expressed maternal genes.

Validation strategies for gRNAs include:

- In vitro cleavage assays using synthesized target sequences

- SITE-seq for biochemical identification of off-target sites [29]

- CIRCLE-seq for highly sensitive, circularized DNA-based off-target detection [29]

- GUIDE-seq for genome-wide identification of off-target sites in cells [29]

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of CRISPR Tools in Early Embryos

| Editing Tool | Typical Efficiency in Early Embryos | Primary Editing Outcome | Off-Target Risk | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | 50-90% indels [7] | Frameshifts, gene knockouts | Medium-high [29] | DSB-induced toxicity, complex karyotypes |

| Cas12 Nuclease | 40-80% indels | Frameshifts, gene knockouts | Medium [29] | Less characterized in embryos |

| Base Editors | 20-60% base conversion [29] | Point mutations | Low-medium [29] | Restricted editing window, bystander edits |

| Prime Editors | 10-30% desired edits [29] | Precise edits, small indels | Low [29] | Lower efficiency, larger construct size |

| dCas9-Epigenetic | Varies by target | Transcriptional modulation | Low | Transient effects, potential redundancy |

Delivery Methods for Oocytes and Early Embryos

The delivery of CRISPR components into oocytes and early embryos presents technical challenges due to the small size and sensitivity of these cells. The most common delivery approaches include:

Microinjection: Direct injection of CRISPR reagents into the cytoplasm or pronucleus of zygotes represents the gold standard delivery method. This approach typically involves injection of Cas9 mRNA or protein complexed with in vitro transcribed gRNA (ribonucleoprotein complexes) [7]. RNP delivery often shows faster editing and reduced off-target effects compared to DNA-based delivery.

Electroporation: For later-stage embryos, electroporation can be an efficient method for delivering CRISPR components. This approach is less technically demanding than microinjection and can be applied to multiple embryos simultaneously.

Viral vectors: While less common for early embryo editing due to size constraints and potential immune activation, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have been used for CRISPR delivery in some contexts. However, the limited packaging capacity of AAVs restricts their utility for larger CRISPR systems.

Analytical Methods for Validation

Comprehensive validation of editing outcomes is essential for interpreting MZT studies. Recommended validation approaches include:

Next-generation sequencing: Amplicon sequencing of target loci provides the most comprehensive assessment of editing efficiency and specificity. This method quantitatively detects both intended edits and unexpected mutations at the target site.

Off-target assessment: Genome-wide methods such as GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq should be employed to identify potential off-target sites [29]. For clinically oriented applications, targeted deep sequencing of predicted off-target sites represents the gold standard for validation [29].

Functional validation: Phenotypic assessment should align with the biological question. For studies of maternal effect genes, developmental progression through MZT and beyond should be carefully documented. For zygotic genes, specific molecular readouts of ZGA or cellular differentiation may be appropriate.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR MZT Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for MZT Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | SpCas9, eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1 [28] | DNA cleavage with NGG PAM | High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects in sensitive embryonic systems |

| Cas12 Variants | Cas12a (Cpfl), Cas12b | DNA cleavage with T-rich PAMs | Alternative PAM recognition expands targetable sites |

| Cas13 Systems | Cas13a, Cas13b, dCas13-ADAR fusions [29] | RNA targeting and editing | Enables transient manipulation of maternal transcripts |

| Base Editors | BE4max, ABE8e | Single-base changes without DSBs | Reduced cellular toxicity compared to nuclease approaches |

| Prime Editors | PE2, PEmax | Precise edits without donor templates | Versatile for introducing specific mutations |

| dCas9 Effector Fusions | dCas9-DNMT3a, dCas9-TET1, dCas9-KRAB [7] | Epigenetic modification | Probing chromatin dynamics during MZT |

| Delivery Tools | Cas9 mRNA, recombinant Cas9 protein, lipid nanoparticles [8] | Introducing editing components | RNP complexes enable rapid editing with reduced persistence |

| gRNA Cloning Systems | Multiplex gRNA vectors [28] | Expressing multiple guides | Essential for targeting redundant pathways or gene families |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 assay, TIDE, targeted deep sequencing [29] | Assessing editing efficiency | NGS methods provide most comprehensive characterization |

Safety and Specificity Considerations

The application of CRISPR technologies in early embryos demands rigorous attention to safety and specificity. Key considerations include:

Off-target effects: Unintended editing at sites with sequence similarity to the target can confound experimental results. Strategies to minimize off-target effects include:

- Using high-fidelity Cas variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) [28]

- Careful gRNA design with emphasis on specificity

- RNP delivery rather than plasmid DNA

- Validating findings with multiple independent gRNAs

On-target accuracy: Even at intended target sites, CRISPR editors can generate heterogeneous outcomes. NHEJ-mediated repair produces unpredictable indels, while base editors can create "bystander" edits at adjacent bases within the editing window [29]. Comprehensive sequencing of edited loci is essential to characterize the full spectrum of editing outcomes.

Embryo viability: The physical manipulation and editing processes themselves can impact embryo development. Appropriate controls, including sham-injected embryos and non-targeting gRNAs, are necessary to distinguish specific editing effects from procedural artifacts.

Future Perspectives

The rapid evolution of CRISPR technologies continues to expand their applications in MZT research. Several emerging areas hold particular promise:

Single-cell multi-omics: Combining CRISPR perturbations with single-cell RNA sequencing and epigenomic profiling will enable comprehensive mapping of gene regulatory networks during MZT at unprecedented resolution.

Temporal control: Development of chemically inducible or light-activatable CRISPR systems will provide precise temporal control over editing activities, essential for dissecting dynamic MZT processes.

Epigenome engineering: Advanced epigenetic editors will facilitate mechanistic studies of how chromatin dynamics regulate ZGA and developmental competence.

Clinical applications: As safety and efficiency improve, CRISPR-based approaches may find therapeutic applications in treating inherited genetic disorders through early embryonic intervention.

The integration of these advanced CRISPR tools with other cutting-edge technologies such as live imaging, single-cell analysis, and computational modeling will continue to transform our understanding of the fundamental biological processes governing the maternal-to-zygotic transition.

The Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition (MZT) is a fundamental reprogramming process in early animal development, encompassing the clearance of maternally provided mRNAs and the activation of the zygotic genome (ZGA) [6] [13] [19]. While transcriptional regulators of MZT are well-studied, the post-translational mechanisms, particularly those controlled by protein phosphorylation, remain less understood [13]. In vertebrate models like zebrafish, systematic study of maternal RNA function has been challenging due to the inefficacy of RNAi and potential off-target effects of morpholinos [13]. The recent adaptation of the CRISPR-RfxCas13d system, an RNA-guided, RNA-targeting effector, has enabled efficient and specific knockdown of maternal mRNAs, opening the door for powerful genetic screens in early vertebrate development [30] [13]. This case study details a proof-of-principle CRISPR-RfxCas13d screen that identified the kinase Bckdk as a novel post-translational regulator of MZT in teleosts.

Experimental Protocol: A CRISPR-RfxCas13d Maternal Screen

1. Screening Design and Candidate Selection

- Biological Objective: To systematically identify maternally deposited mRNAs encoding kinases, phosphatases, and their regulators that are critical for MZT in zebrafish [6] [13].

- Candidate Gene Selection: 49 candidate genes were selected based on their specific transcriptomic and translational patterns, which mirrored those of known MZT regulators like Nanog and Pou5f3 (highly abundant in the oocyte and highly translated at the onset of ZGA) [13].

- gRNA Design and Library: Three chemically synthesized and optimized guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed per target mRNA to maximize knockdown efficacy [13]. The gRNAs were co-injected with purified RfxCas13d protein into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos [13].

2. Phenotypic Screening and Triage

- Primary Phenotypic Readout: Embryonic development was monitored for 24 hours, with a focus on epiboly defects, a phenotype often associated with MZT and ZGA failure [13] [31].

- Hit Identification: From the initial 49 candidates, seven kinase knockdowns induced epiboly defects in at least one-third of injected embryos [13]. The most severe developmental delay was observed upon knockdown of bckdk mRNA [13].

- Validation of Knockdown Efficiency: RNA-seq analysis of 14 candidates (7 with phenotypes and 7 without) confirmed high target knockdown efficiency, with a median mRNA reduction of 92% (range: 58% to 99%) [13].

3. Functional Validation of Bckdk in MZT

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA-seq following bckdk knockdown revealed a significant downregulation of pure zygotic genes (PZGs) at the onset of the major ZGA wave, indicating a failure in genome activation [13].

- Epigenetic and Metabolic Characterization: Further investigation using ATAC-seq, SLAM-seq, and histone modification analysis showed that bckdk depletion led to a significant reduction in the active enhancer mark H3K27ac and a partial impairment of miR-430 processing, which is crucial for maternal mRNA clearance [6] [13].

- Conservation Analysis: The role of Bckdk in MZT was confirmed to be conserved in another teleost, medaka (Oryzias latipes), where its knockdown similarly caused early developmental perturbation and downregulation of PZGs [13].

4. Mechanistic Investigation through Phospho-proteomics

- Target Discovery: Phospho-proteomic analysis was performed to identify substrates whose phosphorylation was altered upon bckdk depletion [6] [13].

- Key Substrate Identification: The chromatin remodeling factor Phf10 (also known as Baf45a), a component of the SWI/SNF complex, was identified as being less phosphorylated in the absence of Bckdk [6] [13].

- Rescue Experiments: Knockdown of phf10 mRNA recapitulated the ZGA defects [6] [13]. Critically, expression of a phospho-mimetic mutant of Phf10 rescued the developmental defects and restored H3K27ac levels in bckdk-depleted embryos, establishing a functional link in the pathway [6] [13].

The following table summarizes the quantitative data from the key phenotypic and molecular analyses of the bckdk knockdown.

| Assay Type | Key Measurement | Result upon bckdk Knockdown | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Phenotype | Embryos with epiboly defects [13] | Severe delay (most severe among 7 hits) | Disruption of a critical early morphogenetic event. |

| Knockdown Efficiency | mRNA reduction (RNA-seq) [13] | High (exact percentage not specified in provided excerpts) | Highly efficient target degradation by RfxCas13d. |

| Zygotic Genome Activation | Downregulation of Pure Zygotic Genes (PZGs) [13] | Significant downregulation | Failure to properly activate the embryonic genome. |

| Epigenetic Landscape | H3K27ac levels [6] [13] | Significant reduction | Loss of an activating histone mark critical for enhancer function. |

| Maternal mRNA Clearance | miR-430 processing [6] [13] | Partially impaired | Defect in the pathway responsible for degrading maternal mRNAs. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow of the screening and validation process, from initial gRNA library design to the final mechanistic insights into Bckdk's role in MZT.

Experimental Workflow from Screen to Mechanism

The molecular relationship between Bckdk and its downstream effectors in regulating MZT is summarized in the following pathway diagram.

Bckdk-Phf10 Pathway in MZT Regulation