CRISPR vs. Morpholino Knockdown: A Comprehensive Guide to Efficacy, Applications, and Best Practices for Researchers

This article provides a systematic comparison of CRISPR-based gene editing and morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) knockdown, two foundational technologies in functional genomics.

CRISPR vs. Morpholino Knockdown: A Comprehensive Guide to Efficacy, Applications, and Best Practices for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of CRISPR-based gene editing and morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) knockdown, two foundational technologies in functional genomics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles, mechanisms, and optimal applications of each tool. The scope ranges from foundational concepts and methodological protocols to troubleshooting off-target effects and validation strategies. By synthesizing current research and technical insights, this guide aims to empower readers in selecting the appropriate technology for their specific experimental goals, from early-stage phenotypic screening to the generation of stable genetic models and therapeutic development.

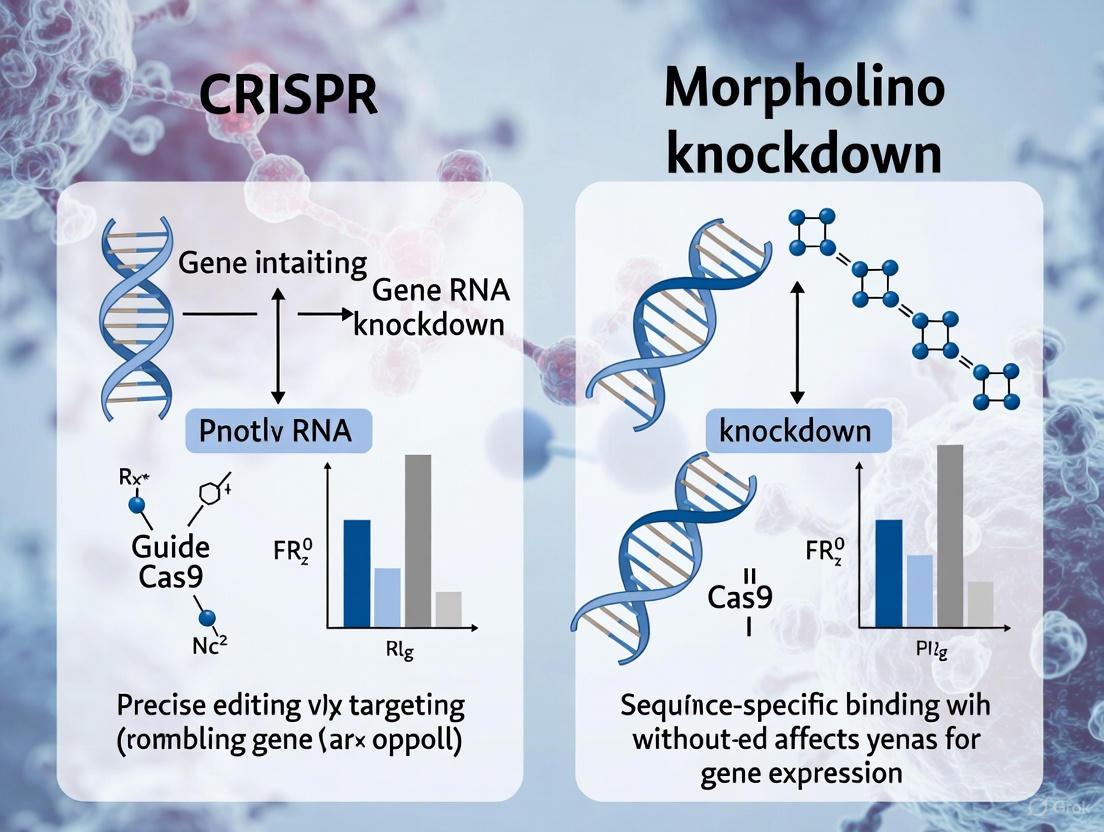

Understanding the Core Mechanisms: From DNA Editing to RNA Knockdown

In functional genomics and therapeutic development, CRISPR and morpholinos represent two powerful but fundamentally distinct technologies. CRISPR-Cas9 is a genome-editing system that permanently modifies DNA sequences, while morpholino oligonucleotides are antisense molecules that temporarily modulate RNA processing and translation [1] [2] [3]. This comparison guide examines their mechanisms, applications, and experimental considerations to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their specific research context.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of CRISPR and Morpholino Technologies

| Characteristic | CRISPR-Cas9 | Morpholino Oligonucleotides |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | DNA | RNA (mRNA or pre-mRNA) |

| Primary Mechanism | Creates double-strand breaks in DNA; exploits cellular repair mechanisms (NHEJ/HDR) for permanent changes [2] | Steric blockade of translation initiation or pre-mRNA splicing via Watson-Crick base pairing [4] [3] |

| Nature of Effect | Typically permanent, heritable genetic modification | Transient, non-heritable knockdown |

| Duration of Effect | Stable, long-lasting | Temporary (days to a week, depending on system) |

| Key Components | Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9) + guide RNA (sgRNA) [2] | Single-stranded morpholino oligo (25-30 bases) [3] |

| Common Applications | Gene knockout, knock-in, gene correction, large-scale screening, therapeutic genome editing [5] [2] | Acute gene knockdown, splicing modulation, translational inhibition, developmental biology studies [1] [6] |

Mechanisms of Action: DNA Editing Versus RNA Interference

CRISPR-Cas9: Programmable DNA Cleavage

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as a programmable DNA endonuclease. The Cas9 enzyme is directed to a specific genomic locus by a guide RNA (gRNA) that is complementary to the target DNA sequence. Upon binding, Cas9 creates a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA [2]. The cell then repairs this break through one of two primary pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cut site. This can disrupt the open reading frame of a gene, effectively creating a knockout [2].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a donor DNA template to introduce specific genetic alterations, such as point mutations or gene insertions (knock-in) [2].

Morpholinos: Steric Blockade of RNA Function

Morpholinos are synthetic oligonucleotides where the natural ribose sugar backbone is replaced by a morpholine ring and connected via phosphorodiamidate linkages [1] [3]. This unique structure makes them uncharged, nuclease-resistant, and stable in vivo. They do not degrade their target RNA but instead act through steric hindrance [4]. The two primary design strategies are:

- Translation-Blocking Morpholinos: Bind to the 5' untranslated region (UTR) including the AUG start codon, physically preventing the ribosomal complex from initiating translation [1] [3].

- Splice-Blocking Morpholinos: Target exon-intron or intron-exon junctions in pre-mRNA, interfering with the splicing machinery and often leading to exon skipping or intron retention [1] [3] [6].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Typical Workflow for CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

- Target Selection and gRNA Design: Identify the target genomic sequence adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which is required for Cas9 recognition (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) [2]. Design 2-3 gRNAs with high on-target and low off-target potential using computational tools.

- Component Delivery:

- In vitro: Deliver Cas9 and gRNA expression plasmids, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, or viral vectors into cells via transfection, electroporation, or viral transduction [2].

- In vivo: Systemic delivery using viral vectors (e.g., AAV) or non-viral methods like Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), which show promise for therapeutic applications, particularly for liver targets [5].

- Validation and Analysis:

- Confirm editing efficiency via T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

- For knockouts, validate protein loss by western blot or immunofluorescence.

- For knock-ins, confirm correct integration via PCR and sequencing.

A Typical Workflow for Morpholino-Mediated Knockdown

- Target Selection and Morpholino Design:

- Delivery:

- Validation and Analysis:

- For translation blockers: Assess protein reduction via western blot, immunofluorescence, or functional assays.

- For splice blockers: Use RT-PCR to detect changes in mRNA splicing patterns (e.g., size shifts due to exon skipping) [3] [6].

- Always include standard control and mismatch morpholinos to confirm specificity [3].

Performance and Efficacy Comparison

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Efficacy and Experimental Parameters

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 | Morpholino Oligonucleotides |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Knockdown/Knockout Efficiency | 50% - 90% in different experimental setups [7] | Dose-dependent; ED₅₀ in the range of 1–3 μmol/L for effective splice-blocking in cells [6] |

| Time to Onset of Effect | Dependent on protein turnover; can take 24-72 hours for full effect | Rapid; effect can be observed within hours of delivery |

| Optimal Research Context | Stable gene inactivation, generating mutant lines, therapeutic correction of mutations [5] [2] | Acute, transient knockdown; studying early developmental processes; splicing modulation [1] [8] |

| Key Advantages | Permanent modification, versatile (knockout/knock-in), suitable for in vivo therapy [5] | Rapid application, no genetic compensation reported, temporal control via timing of delivery [1] [8] |

| Key Limitations | Potential for off-target editing, complex delivery, ethical concerns for germline editing | Transient effect, potential for off-target toxicity (p53 activation), requires careful dose optimization [1] |

Recent studies highlight the contextual nature of their efficacy. For example, in a direct comparison in chick embryos, CRISPR-Cas13d (an RNA-targeting CRISPR system) achieved knockdown of the PAX7 gene that was comparable to a translation-blocking morpholino [8]. In therapeutic contexts, systemic delivery of CRISPR-LNPs for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) achieved a ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels in human clinical trials [5], whereas a morpholino (eteplirsen) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is FDA-approved to induce exon skipping and restore the reading frame of dystrophin in a subset of patients [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease (protein or plasmid) | The effector enzyme that cuts the target DNA [2]. | Choose between wild-type (creates DSBs) or nickase/nuclease-dead (dCas9) variants for different applications. |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | A synthetic RNA that directs Cas9 to the specific DNA target sequence [2]. | Can be produced via in vitro transcription, purchased as synthetic RNA, or delivered via plasmid. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotide | A synthetic antisense oligo that binds target RNA to block translation or splicing [3]. | Must be designed to be perfectly complementary to the target RNA sequence; typically 25 bases in length. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A non-viral delivery vehicle for in vivo delivery of CRISPR components or other nucleic acids [5]. | Particularly effective for targeting the liver; enables potential re-dosing. |

| Control Morpholino | A standard control (e.g., scrambled sequence) to distinguish specific from non-specific effects [3] [6]. | Critical for validating that observed phenotypes are due to specific gene knockdown. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Donor Template | A DNA template containing the desired sequence change, used to precisely edit the genome after a DSB [2]. | Can be a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or a double-stranded DNA plasmid. |

The choice between CRISPR and morpholinos is not a matter of which tool is superior, but which is optimal for the specific biological question and experimental system.

- Choose CRISPR-Cas9 when the research goal requires permanent, heritable genetic modification, such as generating stable cell lines or animal models, conducting large-scale genetic screens, or developing therapeutic interventions that correct the underlying genetic cause of a disease [5] [2].

- Choose Morpholinos for experiments requiring rapid, transient gene knockdown without altering the genome, particularly in early developmental studies (e.g., in zebrafish, Xenopus, or chick embryos), for modulating RNA splicing, or when investigating genes where early knockout is embryonically lethal [1] [8].

The future of genetic research lies in the synergistic use of both technologies. Morpholinos can provide rapid initial functional data, while CRISPR can be used to generate stable, validated models. Furthermore, the emergence of new systems like CRISPR-Cas13d, which targets RNA like morpholinos but is encoded by plasmids, expands the available toolkit, offering researchers more flexibility to design rigorous and informative experiments [8].

In functional genomics and therapeutic development, two principal technologies enable targeted gene disruption: the CRISPR-Cas9 system and Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs). These technologies employ fundamentally distinct mechanisms to achieve gene knockdown. CRISPR-Cas9 introduces permanent genomic modifications by creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which are then repaired by cellular mechanisms that often result in gene disruption [9]. In contrast, Morpholinos are synthetic antisense oligonucleotides that achieve transient gene knockdown by blocking translation or splicing of targeted RNA transcripts without altering the underlying DNA sequence [10] [11]. Understanding their mechanistic differences is critical for researchers selecting the appropriate tool for specific experimental or therapeutic goals, particularly in studies assessing gene function and developing genetic therapies.

Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 Action

Core Components and DNA Targeting

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as a programmable DNA endonuclease. Its operation requires two core components: the Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA), a short synthetic RNA sequence complementary to the target DNA locus. The gRNA directs Cas9 to a specific genomic location through Watson-Crick base pairing, while an adjacent protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence is essential for Cas9 recognition and cleavage activity [9].

Double-Strand Break Induction and Repair Pathways

Once bound to the target DNA, Cas9 induces a double-strand break (DSB) approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site. The cell subsequently attempts to repair this break through two primary pathways [9]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This error-prone pathway directly ligates the broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). If these indels are not multiples of three nucleotides, they cause frameshift mutations that lead to premature termination codons (PTCs) and gene knockout [9] [12].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This precise repair pathway uses a homologous DNA template to repair the break, potentially allowing for specific gene corrections or insertions when an exogenous donor template is supplied [9].

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism for inducing double-strand breaks and subsequent repair pathways leading to genetic outcomes.

Mechanism of Morpholino Oligonucleotide Action

Molecular Structure and Design Principles

Morpholino oligonucleotides are synthesized with a specific chemical architecture that distinguishes them from natural nucleic acids. They feature a phosphorodiamidate backbone with morpholine rings instead of the ribose sugar-phosphate backbone found in DNA and RNA. This unique structure confers several advantages: neutral charge preventing non-specific binding to cellular proteins, resistance to enzymatic degradation, and high binding affinity for complementary RNA sequences [10] [11].

MO design follows precise parameters: typically 25 bases in length, 40-60% GC content, and minimal self-complementarity to prevent secondary structure formation. Target specificity is crucial, particularly in organisms like zebrafish which often possess duplicated genes (paralogs) that may require paralog-specific MO designs [10] [11].

Modes of Action: Translation Blocking and Splice Modification

MOs exert their effects through two primary mechanisms based on their target binding sites:

Translation Blocking: MOs targeting the 5' untranslated region (UTR) or region surrounding the translational start site physically prevent the assembly of the translation initiation complex, thereby blocking ribosome scanning and protein synthesis. This approach effectively knocks down both maternal and zygotic transcripts [10] [11].

Splice Modification: MOs targeting splice junctions (5' splice donor sites, branch points, or 3' splice acceptor sites) interfere with splicesome assembly and pre-mRNA processing. This results in exon skipping, intron retention, or activation of cryptic splice sites, often producing frameshifts and premature termination codons that lead to nonsense-mediated decay of the aberrant transcript [10].

Figure 2: Two primary mechanisms of Morpholino action showing translation blockade and splice modification pathways.

Comparative Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Efficiency and Applications

Table 1: Direct comparison of key characteristics between CRISPR-Cas9 and Morpholino technologies

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 | Morpholino Oligonucleotides |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | DNA | RNA |

| Mechanism | DSB induction followed by NHEJ/HDR repair [9] | Steric blockade of translation or splicing [10] [11] |

| Persistence | Permanent, heritable changes | Transient (typically 3-5 days in zebrafish) [10] [11] |

| Efficiency Range | Variable (10-90% depending on system) | High with proper design and delivery |

| Delivery Methods | Viral vectors, plasmids, RNPs [13] | Microinjection, "caged" MOs for temporal control [10] [11] |

| Primary Applications | Stable gene knockout, gene correction, therapeutic editing [9] | Transient knockdown, isoform-specific targeting, maternal transcript targeting [10] |

| Optimal Use Case | Permanent genetic modification, animal model generation | Rapid functional screening, essential gene analysis, developmental studies [11] |

Experimental Outcomes in Model Systems

Table 2: Experimental results demonstrating efficacy and specific applications of each technology

| Experiment | System | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR: HTT CAG repeat contraction | Human HEK293T cells (41 CAG repeats) | ~90% contraction when DSB within repeats; complete tract deletion with upstream DSB [14] [15] | BMC Biology (2024) |

| CRISPR: SMN2 splicing correction | SMA iPSCs and mice | Disruption of ISS-N1 enhanced exon 7 inclusion; rescued SMA mice survival to >400 days [16] | NSR (2019) |

| CRISPR: Alternative splicing induction | Rabbit models | Exon skipping only occurred with PTC mutations, not missense mutations [17] | Genome Biology (2018) |

| Morpholino: AHR2 knockdown | Zebrafish embryos | Protection against TCDD-induced pericardial edema [11] | Methods Mol Biol (2012) |

| Morpholino: p53 co-knockdown | Zebrafish embryos | Reduced off-target apoptosis in MO-treated embryos [18] | PLoS Genetics (2007) |

| Morpholino: Cyp1a knockdown | Zebrafish embryos | Exacerbated toxicity from PAHs (ANF, BNF) [11] | Methods Mol Biol (2012) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Gene Knockout

The standard protocol for implementing CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing involves sequential steps from design to validation:

Target Selection and gRNA Design: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to a PAM (NGG for SpCas9). Tools like CRISPOR or CHOPCHOP can predict efficiency and minimize off-target effects. For repetitive regions like CAG tracts, careful gRNA positioning is critical—DSBs within repeats yield contractions while upstream breaks cause complete tract deletions [14] [15].

Component Delivery: Transfert cells with plasmids encoding both Cas9 and gRNA, or use preassembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for higher precision and reduced off-target effects. Delivery methods include lipid nanoparticles, viral vectors, or electroporation [13].

DSB Induction and Repair: After cellular uptake, the Cas9-gRNA complex localizes to the target DNA and induces DSBs. The cell's endogenous repair machinery, predominantly NHEJ, introduces indels at the break site [9].

Validation and Screening: Extract genomic DNA 24-72 hours post-transfection. Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze edits by sequencing (Sanger or NGS) or T7 endonuclease I assay. For the HTT CAG repeat study, deep sequencing precisely quantified repeat contraction frequencies [14].

Morpholino Knockdown Protocol

The established protocol for effective morpholino-mediated gene knockdown includes:

MO Design and Preparation: For translation blocking, target the 25 bases surrounding the start codon. For splice blocking, target splice acceptor/donor sites or branch points. Resuspend lyophilized MO in high-grade water to 1-5 mM stock concentration. Validate sequence specificity, especially in zebrafish with paralogous genes [10] [11].

Embryo Microinjection: Prepare working dilutions (typically 0.5-5 ng/nL) in injection buffer. Microinject 1-2 nL into the yolk or cytoplasm of 1-8 cell stage zebrafish embryos. The cytoplasmic bridges enable ubiquitous MO distribution. Include standard control MOs to distinguish specific from non-specific effects [10].

Phenotypic Assessment: Monitor embryos for expected morphological changes over 1-5 days post-fertilization (dpf). For splice-blocking MOs, validate efficacy by RT-PCR to detect altered splicing patterns 24-48 hours post-injection [10].

Off-Target Mitigation: To address p53-mediated apoptosis, a common off-target effect, co-inject with p53-targeting MO (0.5-1 ng/nL). This approach specifically reduces non-specific cell death without affecting specific knockdown phenotypes [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and materials required for implementing CRISPR-Cas9 and Morpholino techniques

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components | SpCas9 nuclease, sgRNA scaffolds, PAM-compatible plasmids | Core editing machinery [9] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lentiviral/AAV vectors, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation systems | Cellular introduction of editing components [13] |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Translation blockers, splice blockers, standard control MOs | Gene-specific knockdown [10] [11] |

| Microinjection Supplies | Microinjector, micropipette puller, borosilicate glass capillaries | Embryo manipulation and delivery [10] |

| Validation Tools | T7 endonuclease I, sequencing primers, Western blot antibodies | Efficiency assessment and confirmation [14] [10] |

| Specialized Modifications | HiFi Cas9 variants, base editors, "caged" photoactivatable MOs | Enhanced specificity or temporal control [13] [11] |

CRISPR-Cas9 and Morpholino technologies offer complementary approaches for gene disruption with distinct mechanistic bases and application landscapes. CRISPR-Cas9 creates permanent DNA-level modifications through DSB repair, making it ideal for generating stable cell lines, animal models, and therapeutic interventions. Conversely, Morpholinos provide transient, RNA-level knockdown perfect for rapid functional screening, developmental studies, and analyzing essential genes where permanent knockout would be lethal. The selection between these technologies depends fundamentally on the experimental timeline, desired persistence of effect, and specific biological question. As both technologies continue to evolve with enhanced specificity and novel applications, they will remain indispensable tools in the molecular biologist's arsenal for deciphering gene function and developing genetic therapies.

In functional genomics and drug development, two technologies represent fundamentally different approaches to probing gene function: Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) and CRISPR-Cas9 systems. MOs provide transient gene knockdown by targeting specific RNA sequences, while CRISPR creates permanent, heritable mutations at the DNA level. This distinction creates a temporal divide that significantly impacts experimental design, data interpretation, and translational applications. For researchers investigating developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic targets, understanding this dichotomy is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool and accurately evaluating resulting phenotypes. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics, experimental parameters, and optimal applications of these technologies, providing a framework for their use in modern biological research.

Morpholino Oligonucleotides (MOs): Transient Knockdown

Morpholinos are synthetic antisense oligonucleotides typically 25 bases in length, composed of morpholine rings connected by phosphorodiamidate linkages [19]. This unique chemistry makes them highly resistant to nucleases, providing stability in biological systems without triggering significant innate immune responses [1]. MOs function primarily through two distinct mechanisms:

- Translation Blocking: MOs bind to the 5' untranslated region (UTR) and start codon of target mRNAs, sterically preventing the ribosomal initiation complex from assembling and proceeding with protein synthesis [19].

- Splice Modification: MOs target splice donor or acceptor sites in pre-mRNA, disrupting normal processing and leading to exon skipping, intron retention, or activation of cryptic splice sites, typically generating nonfunctional protein products [11] [19].

A key advantage of MOs is their temporal flexibility. They can be injected into zebrafish embryos at the 1-8 cell stage, providing effective knockdown through the first 4 days of development [11]. For conditional applications, "caged" MOs can be photo-activated to function in specific locations at specific times, creating spatially and temporally controlled knockdowns [11].

CRISPR-Cas Systems: Permanent Genome Editing

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, derived from a bacterial adaptive immune system, creates targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in genomic DNA [20]. The system comprises two key components:

- Guide RNA (gRNA): A synthetic RNA molecule that directs the Cas nuclease to complementary DNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing [13].

- Cas9 Nuclease: An enzyme that introduces double-strand breaks three base pairs upstream from protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs) in the target DNA [20].

Following DNA cleavage, cellular repair mechanisms are activated:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone pathway that results in small insertions or deletions (indels), often disrupting gene function through frameshift mutations [13].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that allows for specific genetic modifications when a donor DNA template is provided [13].

Unlike MOs, CRISPR generates permanent, heritable mutations that persist throughout the organism's lifespan and can be transmitted to subsequent generations, enabling the creation of stable mutant lines [21].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis

Table 1: Key Characteristics of MO and CRISPR Technologies

| Parameter | Morpholino (MO) | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Control | Transient (4-5 days in zebrafish) [11] | Permanent, heritable |

| Molecular Target | mRNA | Genomic DNA |

| Mechanism | Translation blocking, splice modification [19] | DNA double-strand break, NHEJ/HDR repair [13] |

| Onset of Effect | Rapid (hours) | Delayed (requires turnover of existing protein) |

| Duration of Effect | Days | Lifetime and inheritable |

| Efficiency Range | Variable (dose-dependent) [19] | Variable (depends on gRNA design, delivery) [20] |

| Optimal GC Content | 40-60% [19] | 65% or higher for improved efficiency [22] |

| Typical Delivery | Microinjection into embryos [19] | Multiple methods (microinjection, viral vectors, LNPs) [5] |

| Cost Considerations | Moderate (reagent cost) | Low (CRISPR), higher (delivery optimization) |

Table 2: Applications and Limitations

| Aspect | Morpholino (MO) | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Applications | Acute knockdowns, early development studies, splice modulation, conditional knockdowns [11] | Stable mutant lines, genetic screening, disease modeling, gene therapy [5] |

| Key Advantages | Rapid deployment, titratable effects, targets maternal mRNA, temporal control [11] [21] | Permanent modification, high specificity versions available, versatile editing capabilities [20] |

| Primary Limitations | Transient nature, off-target effects (p53 activation) [1], limited to developmental windows | Potential for compensatory mutations [23], off-target editing [20], mosaic F0 generation |

| Phenotype Concordance | May reveal functions obscured in mutants by genetic compensation [21] [23] | May show absence of phenotype due to genetic compensation [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Morpholino Knockdown Experiments

MO Design Considerations:

- Sequence Selection: Target the 5' UTR extending no more than 25 bases upstream of the start codon for translation blockers, or splice donor/acceptor sites for splice modifiers [19].

- Specificity Controls: Perform BLAST analysis to ensure target sequence uniqueness and design two non-overlapping MOs against the same target to confirm phenotype specificity [21].

- Optimization Parameters: Design MOs that are 25 bases long with 40-60% GC content, avoiding stretches of more than three contiguous guanines [19].

Experimental Workflow:

- MO Preparation: Resuspend lyophilized MO in cell culture-grade water at 1-3 mM concentration. Heat at 65°C for 10 minutes with vortexing to ensure complete resuspension [19].

- Concentration Optimization: Perform dose-response experiments (typically 1-10 ng per embryo) to identify the optimal phenotype-to-toxicity ratio [19].

- Microinjection: Inject 1-8 cell stage zebrafish embryos using standard microinjection apparatus [11].

- Validation Assays:

- Phenotypic Analysis: Document morphological changes at appropriate developmental stages.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Off-target effects can be controlled by co-injecting p53-targeting MOs to suppress apoptotic responses [19].

- Phenotype specificity should be confirmed through rescue experiments with MO-insensitive mRNA [1].

CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis Experiments

gRNA Design and Construction:

- Target Selection: Identify 20-base target sequences adjacent to 5'-NGG-3' PAM sites using validated computational tools (CRISPR-P 2.0, E-CRISP, CasFinder) [20].

- Efficiency Optimization: Select gRNAs with GC content >65% for improved editing efficiency, as demonstrated in grapevine mutagenesis studies [22].

- Specificity Enhancement: Consider truncated gRNAs (17-18 nucleotides) to reduce off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity [20].

Experimental Workflow:

- Component Preparation: Synthesize gRNA and Cas9 mRNA or prepare ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Delivery Method Selection: Choose appropriate delivery method (microinjection, viral vectors, or lipid nanoparticles) based on target organism/cells [5].

- Microinjection: Inject into zygotes or early embryos for heritable mutations.

- Mutation Validation:

- PCR amplification of target region followed by restriction enzyme assay (if editing disrupts a site).

- T7 endonuclease I or SURVEYOR assays to detect heteroduplex formation.

- Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products or next-generation sequencing for precise mutation characterization.

- Founder Screening: Identify germline-transmitted mutations in F1 generation.

Advanced Considerations:

- For improved specificity, use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9) [20].

- Employ novel repressor domains like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) for enhanced CRISPRi efficiency [24].

Critical Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morpholino Oligos | Translation-blocking MOs, splice-modifying MOs [19] | Acute gene knockdown, splice modulation, developmental studies [11] | Dose optimization required, validate with two non-overlapping MOs [21] |

| CRISPR Nucleases | Wild-type Cas9, High-fidelity variants (eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) [20] | Gene knockout, large-scale screening, therapeutic development [5] | Specificity varies by variant; PAM requirements constrain targeting |

| CRISPR Repressors | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) [24] | Transcriptional repression (CRISPRi), reversible knockdown | No DNA damage; enables temporal control of gene expression |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), viral vectors [5] | In vivo delivery, therapeutic applications | Cell-type specificity; immunogenicity concerns with viral vectors |

| Validation Tools | T7EI assay, antibody detection, RT-PCR [19] | Editing efficiency confirmation, knockdown verification | Method depends on MO type (translation vs splice-blocking) |

Interpretation of Divergent Phenotypes

A significant challenge in genetic manipulation is the frequent observation of different phenotypes between MO knockdowns and CRISPR mutants targeting the same gene. Understanding the biological and technical bases for these discrepancies is essential for proper data interpretation.

Genetic Compensation in Mutants

CRISPR-generated mutants may fail to display expected phenotypes due to transcriptional adaptation or genetic compensation. This phenomenon occurs when mutations that produce degraded transcripts trigger upregulation of functionally related genes, potentially compensating for the lost gene function [23]. Notably, this compensation response is typically activated by mutant mRNA degradation rather than protein loss, explaining why MO knockdowns (which don't necessarily cause transcript degradation) may not trigger the same compensatory mechanisms [23].

Technical Considerations

Temporal Factors:

- MOs produce acute protein depletion, potentially revealing functions essential during specific developmental windows.

- CRISPR mutants experience lifelong gene absence, potentially allowing for developmental adaptation.

Maternal Contributions:

- Translation-blocking MOs can target both maternal and zygotic transcripts [19].

- CRISPR mutants typically only affect zygotic genome, leaving maternal contributions intact in early development.

Experimental Design Considerations:

- MO-specific artifacts: Potential off-target effects can be controlled using p53-targeting MOs and rescue experiments [19].

- CRISPR-specific limitations: Mosaic F0 animals may show variable phenotypes; stable lines are needed for conclusive analysis.

The choice between MO-mediated knockdown and CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis depends fundamentally on the research question, temporal requirements, and desired permanence of the genetic perturbation. MOs offer unparalleled temporal control and are ideal for studying acute gene functions, early developmental processes, and when titratable effects are desirable. CRISPR technologies provide permanent, heritable modifications essential for creating stable model systems, studying long-term genetic effects, and therapeutic applications.

For comprehensive gene characterization, a combined approach is often most powerful:

- Use MOs for rapid initial assessment of gene function and early developmental roles.

- Employ CRISPR to generate stable mutant lines for detailed phenotypic analysis across the lifespan.

- Interpret phenotypic discrepancies not necessarily as technical failures but as potential insights into compensatory mechanisms and genetic network interactions.

As both technologies continue to evolve—with advances in conditional CRISPR systems and improved MO delivery methods—their complementary strengths will further enhance their utility in functional genomics and drug development research.

The field of developmental genetics and functional genomics has been profoundly shaped by two powerful technologies: Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) and CRISPR-based genome editing. Morpholinos, developed in the 1990s and widely adopted in the early 2000s, represent a knockdown approach that transiently suppresses gene expression at the RNA level. In contrast, CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) systems, which emerged as a versatile genome-editing tool in the 2010s, enable a knockout approach that creates permanent modifications at the DNA level. While MOs have been indispensable, particularly in early vertebrate models like zebrafish and Xenopus, CRISPR has revolutionized genetic research by enabling precise genomic modifications across a wide range of organisms. Understanding the technical specifications, applications, strengths, and limitations of each technology is crucial for researchers selecting the appropriate tool for specific experimental questions in basic research and drug development.

Morpholino Oligonucleotides: Design and Mechanism

Morpholino oligonucleotides are synthetic antisense molecules designed to bind to complementary RNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing. Their unique chemical structure features a morpholine ring backbone connected by phosphorodiamidate linkages, which makes them uncharged and resistant to cellular nucleases, ensuring stability in biological systems [1]. MOs function primarily through two mechanisms:

Translation Blocking: MOs designed to target the 5' untranslated region (UTR) and the start codon (AUG) prevent the assembly of the translation initiation complex, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis [1] [25].

Splice Blocking: MOs binding to exon-intron or intron-exon splice junctions disrupt spliceosome assembly, leading to exon skipping or intron retention, which often generates defective or truncated proteins [1] [26].

MOs are typically delivered into early-stage embryos (e.g., 1-4 cell stage zebrafish embryos) via microinjection, making them ideal for studying gene function during early development [25].

CRISPR-Cas Systems: From DNA Cleavage to RNA Targeting

CRISPR-Cas systems are adaptive immune mechanisms in bacteria and archaea that have been repurposed for precise genome editing in eukaryotic cells. The most widely used system, CRISPR-Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at sites specified by a guide RNA (gRNA) and adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [2]. The DSBs are then repaired by the cell's endogenous machinery:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels), leading to frameshift mutations and gene knockouts [2].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a template to introduce specific genetic modifications [2].

More recently, CRISPR-Cas13 systems have been developed that target RNA instead of DNA. Cas13d, in particular, has been successfully adapted for targeted gene expression knockdown in model organisms like zebrafish and chick embryos, functioning at the transcript level similarly to MOs but with different delivery mechanisms and potential for spatial-temporal control [8].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms of action for both technologies:

Technical Comparison and Experimental Data

Key Technical Specifications

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of MOs versus CRISPR-Cas systems:

| Feature | Morpholino Oligonucleotides | CRISPR-Cas Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | RNA (mature or pre-mRNA) | DNA (Cas9) or RNA (Cas13) |

| Mechanism of Action | Steric blocking of translation or splicing | Enzymatic cleavage followed by DNA repair or RNA degradation |

| Genetic Effect | Transient knockdown | Permanent knockout (Cas9) or transient knockdown (Cas13) |

| Duration of Effect | Transient (days to a week) | Permanent (Cas9) or transient (Cas13) |

| Delivery Method | Microinjection into embryos | Microinjection, electroporation, viral vectors, LNPs |

| Typical Efficiency | Variable (dose-dependent) | High (can approach 100% in some systems) |

| Primary Applications | Acute gene suppression, splice modulation, developmental studies | Gene knockout, knock-in, epigenetic modification, gene activation/repression |

Efficacy Comparison in Model Organisms

Direct comparative studies in zebrafish and other model organisms have revealed complex efficacy patterns for both technologies:

| Organism/Application | Morpholino Performance | CRISPR Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish - Early Development | Rapid phenotype assessment (24-48 hpf); Effective for maternal and zygotic transcripts [1] [25] | Requires generation of stable lines; Potential embryonic lethality masking later phenotypes [21] | MOs preferred for acute knockdowns; CRISPR better for stable genetic lines |

| Zebrafish - Genetic Compensation | Phenotypes often observed [27] | Compensation by related genes may mask phenotypes [21] [27] | Transcriptional adaptation in mutants can lead to false negatives with CRISPR |

| Chick Embryo | Effective with microinjection or electroporation [8] | Cas9 effective; Cas13d recently adapted with comparable efficacy to MOs [8] | Both technologies viable; Cas13d offers plasmid-based alternative to MOs |

| Human Cell Lines/Therapeutics | Limited use in therapeutics | Multiple clinical trials (e.g., hATTR, sickle cell disease) [5] | CRISPR dominates therapeutic applications with permanent corrections |

Experimental Workflow Comparison

The typical workflows for implementing MO and CRISPR approaches differ significantly in their timeframes and technical requirements:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Morpholino Knockdown in Zebrafish Embryos

Protocol for Translation-Blocking MO in Heart Development Studies [25]

MO Design: Design a 25-base morpholino complementary to the sequence surrounding the translation start site of the target gene. Verify sequence specificity using BLAST against the zebrafish genome.

MO Preparation: Resuspend the MO to a stock concentration of 1-5 mM in nuclease-free water. Prepare working solutions (typically 0.5-2 ng/nL) for microinjection.

Embryo Collection and Preparation: Collect zebrafish embryos within 30 minutes of spawning and maintain in embryo medium. Arrange embryos in injection mold.

Microinjection: Load MO solution into a glass capillary needle and calibrate injection volume (typically 1-2 nL per embryo). Inject into the yolk or cell cytoplasm of 1-4 cell stage embryos.

Dose Optimization: Perform preliminary dose-response experiments with concentrations ranging from 0.5-8 ng per embryo to identify the minimum effective dose while minimizing toxicity.

Phenotype Assessment: For heart development studies, examine embryos at 24-72 hours post-fertilization (hpf) for cardiac malformations, edema, and circulatory defects.

Validation Experiments: Include appropriate controls: standard control MO, second non-overlapping MO targeting the same gene, and rescue experiments with synthetic mRNA encoding the target gene.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing in Zebrafish

Protocol for Generating Stable Mutant Lines [26]

gRNA Design and Synthesis: Identify target sequence (20 nt) adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence in an early exon of the target gene. Synthesize gRNA by in vitro transcription or purchase as synthetic RNA.

Cas9 mRNA Preparation: Obtain Cas9 expression vector and synthesize capped mRNA using in vitro transcription kits.

Microinjection Mixture: Prepare injection mixture containing Cas9 mRNA (150-300 pg/nL) and gRNA (25-50 pg/nL) in nuclease-free water.

Embryo Injection: Inject 1-2 nL of the mixture into the cell cytoplasm or yolk of single-cell zebrafish embryos.

Founder Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood. Outcross F0 fish to wild-type partners and screen F1 progeny for germline transmission by PCR and sequencing.

Mutant Line Establishment: Identify F1 fish carrying mutations and incross to establish homozygous lines. Confirm stable transmission of the mutation and characterize the phenotype across generations.

DeMOBS: A Validation Method for Morpholino Specificity

Deletion of Morpholino Binding Sites (DeMOBS) Protocol [26]

Rationale: This method uses CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce small deletions within the MO binding site, creating MO-refractive alleles that can distinguish specific from off-target MO effects.

Guide RNA Design: Design gRNAs targeting the 5' UTR region where the MO binds, ensuring PAM sites are within or adjacent to the MO target sequence.

Mutant Generation: Generate heterozygous mutants carrying deletions in the MO binding site using standard CRISPR methods.

Testing MO Specificity: Outcross heterozygous mutants to wild-type fish and inject embryos with the MO. In the resulting clutch, approximately 50% of embryos will be genotypically wild-type (MO-sensitive) while 50% will be heterozygous for the deletion (MO-refractive).

Phenotype Analysis: Compare phenotypes between MO-sensitive and MO-refractive siblings. Specific MO phenotypes will be suppressed in MO-refractive embryos, while non-specific toxicity effects will persist in both groups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Gene knockdown via translation or splice blocking | Acute suppression of gene function in early development [1] [25] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Permanent gene editing via DNA cleavage | Generation of stable knockout lines, gene correction [26] [2] |

| CRISPR-Cas13d Systems | RNA knockdown without permanent genomic changes | Transcript-level knockdown with temporal control [8] |

| Vivo-Morpholinos | Systemically delivered MOs for later stages | Gene knockdown in juvenile and adult organisms [4] |

| p53 MO | Suppression of p53-dependent apoptosis | Control for off-target effects in MO experiments [26] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery vehicle for CRISPR components | In vivo therapeutic applications [5] |

| nCas9n mRNA | Nickase version of Cas9 with reduced off-target effects | Improved specificity in genome editing [26] |

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Morpholinos for Functional Validation of Disease Variants

MOs have proven particularly valuable for functionally characterizing Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS) in human disease genes. In mitochondrial disease research, MO knockdown in zebrafish has enabled rapid assessment of pathogenicity through rescue experiments [28]. The typical approach involves:

Knockdown Phenotyping: MO-induced suppression of the target gene recapitulates key disease phenotypes (e.g., neurological defects, metabolic abnormalities).

Rescue Experiments: Co-injection of MO with wild-type human mRNA restores normal phenotype, while mutant mRNA fails to rescue, confirming pathogenicity.

Therapeutic Screening: Validated models can be used for small-molecule screening to identify potential therapeutics.

CRISPR in Clinical Applications

CRISPR-based therapies have advanced rapidly into clinical trials, with notable successes including [5]:

Casgevy: The first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia.

hATTR Amyloidosis: Intellia Therapeutics' Phase I trial using LNP-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 to target the TTR gene in the liver, showing ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels.

Hereditary Angioedema (HAE): CRISPR-mediated reduction of kallikrein protein, with 86% reduction in inflammatory attacks at higher doses.

Personalized CRISPR Therapies: Recent breakthrough case of an infant with CPS1 deficiency treated with a bespoke in vivo CRISPR therapy developed in just six months.

The evolution from MOs to CRISPR technologies represents not a simple replacement but an expansion of the genetic toolkit available to researchers. Each technology occupies distinct but complementary niches in biomedical research:

Morpholinos remain the preferred choice for rapid assessment of gene function during early development, particularly when transient knockdown is desirable or when maternal gene contributions need to be targeted. Their relatively low cost, ease of use, and immediate availability make them ideal for preliminary screens and acute interventions.

CRISPR systems dominate applications requiring permanent genetic modification, including the generation of stable animal models, therapeutic gene editing, and large-scale genetic screens. The technology's versatility continues to expand with developments like base editing, prime editing, and epigenome modulation.

For drug development professionals, the technologies offer different pathways: MOs provide rapid target validation in disease models, while CRISPR enables both sophisticated disease modeling and direct therapeutic intervention. As both technologies continue to evolve, their strategic combination will likely yield the most comprehensive insights into gene function and disease mechanisms.

The rapid advancement of gene-editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, has revolutionized functional genomics. However, a perplexing phenomenon often confronts researchers: discrepancies between phenotypes observed in traditional morpholino knockdown (morphant) models versus modern CRISPR-generated mutant lines. This guide objectively examines the growing body of evidence identifying genetic compensation as a primary biological mechanism underlying these phenotypic differences, rather than technical artifacts alone. We compare the efficacy, applications, and limitations of both approaches through experimental data and methodological protocols, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate gene perturbation strategies and interpreting resulting phenotypes within the context of this complex compensatory response.

The field of functional genomics relies heavily on technologies that disrupt gene function to determine phenotypic outcomes. For decades, antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) have served as a cornerstone tool for transient gene knockdown in model organisms, particularly zebrafish and Xenopus. MOs are synthetic molecules designed to block gene expression by binding complementary RNA sequences, either inhibiting translation initiation or pre-mRNA splicing [1]. Their neutral morpholine backbone linked by phosphorodiamidate bonds creates a stable, water-soluble molecule resistant to nucleases, enabling specific RNA targeting without triggering widespread RNA degradation pathways [1].

The emergence of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has provided an alternative approach through permanent gene knockout. This system utilizes a Cas9 nuclease guided by RNA to create double-stranded DNA breaks at specific genomic loci, which are repaired by error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathways, resulting in insertions or deletions (INDELs) that disrupt gene function [29] [30]. More recently, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR/Cas13 systems have expanded the toolbox, enabling targeted transcriptional repression or RNA degradation without permanent genomic alterations [31] [32] [33].

A contentious debate emerged in the mid-2010s when several studies reported poor phenotypic correlation between morpholino knockdowns and CRISPR-generated mutants, initially attributed primarily to off-target effects of morpholinos [21]. However, subsequent research has revealed a more complex biological explanation: differential activation of genetic compensation in response to these distinct perturbation modalities.

Understanding Genetic Compensation

Mechanisms and Evidence

Genetic compensation represents a biological phenomenon where organisms activate compensatory mechanisms to maintain homeostasis following genetic perturbation. Research indicates that mutant lines frequently develop compensatory gene expression changes that mask expected phenotypes, while morphants typically exhibit immediate, acute loss-of-function effects before such compensation can occur [27].

Seminal work by Rossi et al. (2015) demonstrated that permanent mutations induced by gene editing technologies can trigger upregulation of genetically related genes, often from the same gene family or functional network, which partially or completely compensate for the lost gene function [27]. In contrast, transient knockdown using morpholinos typically does not induce this compensatory response, potentially revealing the "true" acute loss-of-function phenotype. This fundamental biological difference explains why morphants sometimes exhibit stronger or different phenotypes than mutants for the same targeted gene, independent of morpholino off-target effects [27].

Evidence supporting this mechanism includes:

- Transcriptomic analyses showing widespread expression changes in mutant but not morphant zebrafish [27]

- CRISPRi knockdown that phenocopies morpholino results rather than mutant phenotypes [27]

- Partial suppression of morphant phenotypes in heterozygous mutants, indicating biological specificity rather than off-target effects [27]

Visualizing Genetic Compensation Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental biological processes that lead to differential phenotypic outcomes between mutagenesis and morpholino approaches:

Genetic Compensation Pathway

Comparative Experimental Data

Phenotypic Discrepancies in Key Studies

Substantial experimental evidence demonstrates phenotypic differences between mutant and morphant models across multiple model organisms and target genes. The table below summarizes key findings from the literature:

| Target Gene | Organism | Mutant Phenotype | Morphant Phenotype | Compensation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple genes in reverse genetic screen | Zebrafish | 80% of morphant phenotypes not recapitulated [21] | Strong, specific phenotypes | Genetic compensation confirmed in follow-up studies [27] |

| Cdh2 | Zebrafish | Severe malformations, early lethality [32] | Viable with specific pituitary defects [32] | Knockdown enables study of essential gene functions |

| miR-196a, miR-219 | Xenopus | Craniofacial and pigment defects [34] | Neural crest loss phenotypes [34] | Both approaches validated with miRNA mimics rescue |

Methodological Comparisons

The technical and practical differences between gene perturbation approaches significantly influence their applications and limitations:

| Parameter | CRISPR Mutants | Morpholino Knockdown | CRISPRi/Knockdown |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of action | Permanent DNA mutation [29] | Transient RNA blocking [1] | Transcriptional repression [33] |

| Temporal resolution | Developmental and permanent | Acute, transient (hours-days) [1] | Inducible, reversible [33] |

| Compensation induction | High (genomic scale) [27] | Low (transcript level) [27] | Variable [33] |

| Technical considerations | Possible embryonic lethality | Dose-dependent toxicity [1] | Efficient, specific repression [33] |

| Key applications | Stable genetic lines, developmental studies | Acute function, essential genes [1] [32] | Temporal control, subtle modulation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Establishing Reliable Knockdown with Morpholinos

Proper morpholino experimentation requires stringent design and validation protocols to ensure specificity:

Target Identification and Verification: Identify zebrafish orthologs from genomic databases (Ensembl, NCBI) and verify transcript sequences by RT-PCR and sequencing of multiple individuals (n=4-6) to detect natural polymorphisms that might affect MO binding efficiency [1].

Morpholino Design:

- Translation-blocking MOs: Target the 5' untranslated region (5'-UTR) and start codon (AUG) to prevent ribosome assembly [1].

- Splice-blocking MOs: Bind to exon-intron or intron-exon splice junctions to induce exon skipping or intron retention [1].

- Design principles include perfect base-pair complementarity with target sequence and minimal self-complementarity [1].

Specificity Controls:

Dose Optimization: Titrate MO concentrations to the lowest effective dose (typically 1-5ng/embryo for zebrafish) to minimize potential off-target effects while maintaining efficacy [27].

CRISPR Mutant Generation and Validation

Establishing valid mutant lines requires careful design and comprehensive phenotypic assessment:

Guide RNA Design:

Mutation Efficiency Assessment:

- Sequence F0 founder animals to confirm mutation presence and type (INDELs vs. large deletions).

- Establish stable F1/F2 lines to ensure heritable mutations.

Phenotypic Analysis:

- Compare multiple mutant alleles when possible.

- Assess potential compensatory gene expression through transcriptomic analyses [27].

Experimental Workflow for Comparative Studies

The following diagram outlines a rigorous experimental approach for comparing mutant and morphant phenotypes while controlling for genetic compensation:

Comparative Gene Function Study

Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate reagents is crucial for successful gene perturbation studies. The table below details key solutions and their applications:

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Morpholino oligonucleotides (Gene Tools LLC) | Transient gene knockdown by blocking translation or splicing [1] | Acute loss-of-function; essential gene study; splice modulation [1] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Permanent gene knockout through DNA cleavage and repair [29] | Stable mutant line generation; developmental studies; domain deletion [29] |

| CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB) | Transcriptional repression without DNA cleavage [33] | Reversible knockdown; subtle expression modulation; essential genes [33] |

| CRISPR/Cas13 systems | Targeted mRNA degradation [32] | RNA-level knockdown; potential alternative to morpholinos [31] |

| Rescue mRNAs | Express target gene despite morpholino presence [27] | Specificity control for morpholino experiments [27] |

Discussion and Research Implications

Context-Dependent Technology Selection

The choice between mutagenesis and knockdown approaches should be guided by specific research questions rather than presumed technological superiority. Each method offers distinct advantages:

Morpholinos are preferable for:

- Studying essential genes where mutant homozygotes are lethal [32]

- Acute loss-of-function studies in early development [1]

- Investigating gene function in organisms where genetic tools are limited [1]

- Splice modulation or other RNA-specific manipulations [21]

CRISPR mutants are essential for:

- Establishing stable genetic lines for long-term studies

- Modeling human genetic diseases with specific mutations [29]

- Studying developmental processes beyond embryonic stages

CRISPRi/Cas13 systems offer promising alternatives that may combine advantages of both approaches, providing specific, efficient knockdown without permanent genomic changes [32] [33].

Future Directions and Best Practices

The recognition of genetic compensation as a fundamental biological phenomenon necessitates revised best practices in functional genomics:

Embrace Complementary Approaches: Rather than dismissing morpholino data that differs from mutant phenotypes, researchers should interpret these differences as potentially revealing important biological compensation mechanisms [27].

Implement Rigorous Controls: For morpholino studies, essential controls include dose optimization, two non-overlapping MOs, rescue experiments, and p53 pathway assessment [27].

Develop Enhanced CRISPR Applications: CRISPRi with dual-guideRNA designs demonstrates improved knockdown efficacy and consistency [33], potentially offering a middle ground with minimal compensatory activation.

Concurrent Transcriptomic Analysis: When phenotypic discrepancies occur, RNA sequencing of both mutants and morphants can identify compensatory gene expression networks [27].

Genetic compensation represents a crucial biological variable that significantly impacts phenotypic outcomes in gene perturbation studies. The historical debate pitting morpholinos against CRISPR mutants has evolved to recognize that phenotypic differences often reflect genuine biological compensation mechanisms rather than mere technical artifacts. A comprehensive understanding of gene function requires acknowledging that organisms respond differently to transient versus permanent genetic perturbations, with each approach revealing distinct aspects of gene function and network robustness. As genetic manipulation technologies continue to advance, researchers should select methodologies based on specific biological questions while implementing appropriate controls and interpretations that account for compensatory mechanisms. The integration of multiple approaches—mutants, morphants, and emerging CRISPR knockdown technologies—provides the most powerful strategy for unraveling complex genetic networks and their roles in development and disease.

Strategic Deployment in Research: Choosing the Right Tool for Your Experimental Goal

In the field of functional genomics, rapid phenotypic screening during early development is crucial for unraveling the complex genetic networks that orchestrate embryogenesis and disease etiology. Researchers and drug development professionals are often faced with the critical decision of selecting the most appropriate loss-of-function technology to meet their experimental goals. Within this context, two powerful approaches—Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) for gene knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9 for gene knockout—offer complementary strengths and limitations [35]. While CRISPR technology has revolutionized genetic engineering with its permanent gene disruption capabilities, Morpholinos remain an indispensable tool for high-throughput phenotypic screening, particularly when investigating early developmental processes where temporal control, scalability, and cost-effectiveness are paramount [21] [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their efficacy in rapid phenotypic screening, with supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform research decisions.

The fundamental distinction between these technologies lies in their mechanism of action: Morpholinos achieve transient gene knockdown by blocking translation or splicing of target mRNAs, while CRISPR/Cas9 creates permanent genetic mutations at the DNA level [35] [26]. This distinction has profound implications for experimental design, especially in developmental studies where the timing of gene function is critical. As we explore the technical performance, experimental workflows, and specific applications of each technology, it becomes evident that both have a justified place in the modern researcher's toolkit, with selection dependent on the specific research questions being addressed.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Performance Profiles

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Morpholino and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies for phenotypic screening

| Parameter | Morpholino (MO) | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Antisense oligonucleotide that binds to RNA; blocks translation or splicing [1] | RNA-guided nuclease creates double-strand breaks in DNA; repaired by error-prone NHEJ or HDR [29] |

| Temporal Control | Immediate effect after delivery; knocks down existing mRNA [1] | Delayed effect due to DNA repair and protein turnover; depends on Cas9 expression and activity [35] |

| Permanence of Effect | Transient (2-4 days in zebrafish) [1] | Permanent; heritable genetic modification [29] |

| Throughput Capacity | High; suitable for screening dozens to hundreds of genes simultaneously [26] | Moderate; requires generation and validation of mutant lines [35] |

| Development Time for Functional Analysis | 1-2 days (direct embryo injection) [1] | Weeks to months (requires germline transmission and stable line establishment) [35] |

| Maternal Effect Assessment | Possible by targeting maternal mRNA pools [26] | Requires generation of maternal-zygotic mutants (multiple generations) [26] |

| Compensatory Mechanisms | Minimal; acute knockdown avoids developmental compensation [21] | Common; genetic compensation can mask phenotypes [21] [26] |

| Off-Target Effects | p53-mediated toxicity; potential non-specific binding [26] | Off-target cleavage at similar genomic sites [36] |

| Additional Applications | Splice modification, miRNA protection, translational blocking [21] | Gene knockout, knock-in, epigenetic editing, transcriptional regulation [30] [36] |

Quantitative Efficacy Data from Comparative Studies

Table 2: Experimental efficacy data from direct comparison studies

| Study System | Morpholino Efficacy | CRISPR/Cas9 Efficacy | Phenotype Concordance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tbx5a gene (Zebrafish) | 2ng MO: >90% pectoral fin defects [26] | N/A | Partial | DeMOBS validation confirmed specificity of MO phenotype; genetic compensation observed in mutants [26] |

| Carbonic Anhydrase Genes (Zebrafish) | Multiple CA isoforms knocked down; novel roles in neural development, reproduction identified [1] | N/A | N/A | MOs enabled rapid functional assessment of entire gene family during early development [1] |

| Imaging-Based Pooled Screening | N/A | Identified regulators of lncRNA localization; high-content phenotype imaging [37] | N/A | CRISPR screening with complex cellular phenotypes beyond MO capabilities [37] |

| ctnnb2 gene (Maternal Effect) | Effective maternal mRNA knockdown [26] | Requires maternal-zygotic mutants | Partial | MOs enabled assessment of maternal gene function without multi-generation breeding [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Morpholino-Based Screening Workflow

MO Design and Validation: Translation-blocking MOs are designed to target the 5' untranslated region (5'-UTR) and start codon (AUG) to prevent ribosome assembly and inhibit translation initiation. Splice-blocking MOs bind to exon-intron or intron-exon splice junctions, leading to exon skipping or intron retention, thereby generating defective or truncated transcripts [1]. The design process involves:

- Target Identification and Verification: Precise identification of the target gene and verification of its transcript sequence using genomic databases (Ensembl, NCBI), followed by sequence verification through RT-PCR and sequencing of multiple individuals to detect natural polymorphisms that might affect MO binding efficiency [1].

- Control Design: Essential controls include standard control MO (Gene Tools), two non-overlapping MOs targeting the same gene to confirm specificity, and rescue experiments with synthetic mRNA engineered to lack the MO target site [21] [26].

- Dose Optimization: Titration experiments (e.g., 2-12ng per embryo) to determine the lowest effective dose that elicits the phenotype while minimizing potential off-target effects [26].

Delivery and Phenotype Analysis: MOs are typically delivered into single-cell or early-stage embryos via microinjection [1]. For zebrafish embryos, 1-2 nL of MO solution is injected into the yolk or cell cytoplasm. After delivery, phenotypic analysis proceeds through:

- Morphological Assessment: Visual inspection for developmental defects at specific timepoints.

- Molecular Validation: RT-PCR, Western blot, or immunohistochemistry to confirm reduction of target RNA or protein.

- High-Throughput Adaptation: For screening applications, automated injection systems and automated image acquisition and analysis can be implemented to process large embryo numbers [26].

CRISPR/Cas9 Screening Workflow

Vector Design and Delivery: For gene knockout approaches, sgRNAs are designed to target early coding sequences or regulatory regions. Single sgRNAs can produce small indels via NHEJ repair, while dual sgRNAs can create large deletions [29]. The implementation involves:

- sgRNA Design: Identification of target sites with high on-target and low off-target potential using AI-powered tools (e.g., DeepCRISPR, CRISPRon) [36]. The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence requirement must be considered for the specific Cas nuclease being used.

- Delivery System Selection: Choice between viral vectors (lentivirus, AAV), lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), or physical methods (electroporation, microinjection) [38]. Recent advances include lipid nanoparticle spherical nucleic acids (LNP-SNAs) that improve cellular uptake and editing efficiency [38].

- Validation: Deep sequencing of target loci to assess editing efficiency and potential off-target effects in relevant cell types.

Mutant Line Generation and Analysis: For developmental studies in model organisms like zebrafish:

- Founder Generation: Microinjection of CRISPR components into single-cell embryos, raising injected embryos (F0) to adulthood.

- Germline Screening: Outcrossing F0 adults and screening F1 progeny for germline transmission using T7 endonuclease assay or sequencing.

- Stable Line Establishment: Raising heterozygous F1 fish and intercrossing to generate homozygous mutants for phenotypic analysis.

- Phenotypic Characterization: Comprehensive analysis across developmental stages, with particular attention to potential genetic compensation mechanisms that may mask true phenotypes [21].

Advanced Applications and Specialized Uses

Specialized Research Applications

Table 3: Application-specific recommendations and considerations

| Research Application | Recommended Technology | Rationale | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Developmental Screens | Morpholino | Rapid assessment; maternal effect analysis; high-throughput capability [1] [26] | Dose optimization critical; include proper controls for specificity |

| Late Developmental/Adult Studies | CRISPR/Cas9 | Permanent modification; analysis beyond early stages [35] | Time-intensive line establishment; watch for genetic compensation |

| Structure-Function Studies | CRISPR/Cas9 | Precise domain deletion; specific amino acid changes [29] | Dual sgRNA approach for large deletions; reading frame preservation |

| Splice Variant Analysis | Morpholino | Splice blocking capability; isoform-specific knockdown [21] | RT-PCR validation of splicing defects; rescue with isoform-specific mRNA |

| Therapeutic Development | CRISPR/Cas9 | Permanent correction; clinical applications [5] | Advanced delivery systems (LNP-SNAs); safety validation required |

| Large-Scale Genetic Screens | Both (Complementary) | MOs for rapid initial screening; CRISPR for validation and mechanistic studies [35] [26] | DeMOBS approach to validate MO phenotypes in CRISPR-refractive alleles [26] |

Addressing Technical Challenges

Morpholino Off-Target Effects: A significant concern with MOs is non-specific effects, particularly p53-mediated toxicity. The Deletion of Morpholino Binding Sites (DeMOBS) method provides a genetic approach to validate MO specificity [26]. This technique involves:

- Creating indel mutations within the 5' UTR MO target site using CRISPR/Cas9.

- Generating heterozygous carriers of these MO-refractive alleles.

- Injecting MO into offspring and assessing whether the phenotype is suppressed in heterozygous mutants compared to wild-type siblings.

- This approach effectively distinguishes genuine morphant phenotypes from those produced by off-target effects [26].

CRISPR Compensation Mechanisms: A notable limitation of CRISPR knockout approaches is the frequent observation that mutant phenotypes are less severe than corresponding morphant phenotypes. This discrepancy is attributed to genetic compensation, where mutations trigger upregulation of related genes that compensate for the lost function [21]. This phenomenon explains why MO knockdown sometimes reveals functions that are masked in knockout models due to compensatory mechanisms [21].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Key research reagent solutions for loss-of-function studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Morpholino Oligomers | Gene knockdown via translation or splicing blockade | Gene Tools LLC [21] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Gene knockout via targeted DNA cleavage | Various Cas9 variants (SpCas9, St1Cas9) [36] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Non-viral delivery of CRISPR components | LNP-SNAs for enhanced delivery [38] |

| AI-Based Design Tools | gRNA optimization and off-target prediction | DeepCRISPR, CRISPRon, Rule Set models [36] |

| DeMOBS Validation System | Genetic validation of MO specificity | CRISPR-generated indels in MO target sites [26] |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Phenotypic screening and analysis | Imaging-based pooled CRISPR screening [37] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that both Morpholino and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies offer distinct advantages for phenotypic screening in early development. Morpholinos excel in scenarios requiring rapid, high-throughput analysis of gene function, particularly when investigating early developmental processes, maternal effects, or when temporal control is essential. Their relatively low cost, straightforward implementation, and immediate effects make them ideally suited for large-scale screening applications. Conversely, CRISPR/Cas9 provides permanent genetic modifications that are essential for studying gene function beyond early development, establishing animal models of disease, and conducting structure-function analyses of specific protein domains.

The most robust research strategies often employ both technologies in complementary roles: using Morpholinos for initial high-throughput screening to identify candidate genes, followed by CRISPR/Cas9 for validation and detailed mechanistic studies. The DeMOBS approach further enhances this integration by providing a genetic method to validate Morpholino specificity [26]. As CRISPR technology continues to advance with improved delivery systems like LNP-SNAs [38] and AI-enhanced design tools [36], its applications in developmental biology will undoubtedly expand. Nevertheless, the unique advantages of Morpholinos for rapid, transient knockdown ensure their continued relevance in the functional genomics toolkit, particularly for researchers focused on high-throughput phenotypic screening during critical early developmental windows.

In functional genomics and drug development, the choice between transient gene knockdown and permanent gene editing is foundational to experimental design. For investigations requiring heritable mutations and long-term studies, the generation of stable cell lines is paramount. CRISPR-based technologies and Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) represent two fundamentally different approaches for probing gene function. CRISPR facilitates permanent, heritable genetic modifications that are passed to subsequent cellular generations, making it the preferred method for generating stable knock-in and knock-out lines [13]. In contrast, MOs induce a transient, non-heritable knockdown, with effects typically lasting from a few days to a week, making them suitable for acute, short-term functional assessments, particularly in early developmental models like zebrafish [1] [39]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their efficacy in creating stable, durable models for research and drug development.

CRISPR-Cas Systems for Permanent Genome Editing

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as a programmable nuclease. A guide RNA (gRNA) directs the Cas enzyme to a specific DNA sequence, where it induces a double-strand break (DSB) [13] [40]. The cell's repair machinery then resolves this break, primarily through two pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels), effectively disrupting the target gene and creating a knockout [13].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that can be co-opted by providing an exogenous DNA donor template. This allows for specific nucleotide changes or the insertion of entire genes, creating a knock-in [13].

When performed in stem cells or early progenitor cells, these edits become permanent and are inherited by all subsequent daughter cells, forming the basis of a stable, clonal cell line [41].

Morpholino Oligonucleotides for Transient Gene Suppression

Morpholinos are synthetic antisense oligonucleotides that sterically block translation or pre-mRNA splicing [1] [42]. Their unique phosphorodiamidate morpholino backbone makes them nuclease-resistant and neutral-charged, which enhances stability and reduces non-specific interactions [42]. However, as they do not integrate into the genome and are diluted through cell division, their effects are inherently transient. This limits their application to short-term experiments and prevents their use in establishing permanently altered cell lines for long-term studies [1] [39].

Performance Comparison: Efficacy, Stability, and Specificity

The following table summarizes a direct, data-driven comparison between CRISPR and Morpholino technologies for generating stable lines.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CRISPR and Morpholino Technologies

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | Morpholino (MO) |

|---|---|---|

| Heritability | Permanent and heritable; edits passed to daughter cells [41] | Transient and non-heritable; effect diluted with cell division [1] |

| Duration of Effect | Lifetime of the cell line | Typically 3-7 days in zebrafish embryos [1] |

| Primary Application | Generation of stable knock-in/knock-out lines; long-term functional studies; therapeutic development [41] [13] | Acute gene knockdown; analysis of early developmental phenotypes; rapid target validation [1] [39] |

| Typical Editing Efficiency (Knock-in) | Up to 84% in optimized systems (e.g., HEK293T with EZ-HRex platform) [41] | Not applicable (no knock-in capability) |

| Key Genomic Risk | Structural variations (megabase deletions, translocations) [40] | Off-target effects via p53 activation [1] |

| Experimental Timeline | Weeks to months (requires screening and validation of clones) [41] | Days (phenotypes assessable within 48-96 hours post-injection) [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Stable Line Generation

Protocol for CRISPR-Cas9 Stable Knock-in Cell Line Generation

This protocol is adapted from established methods for creating clonal lines with precise, durable integrations [41].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Stable Line Generation

| Reagent | Function | Stability & Handling Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered Cas9 protein for high-fidelity cleavage. | Stable ≥1 year at -20°C; withstands 10+ freeze-thaw cycles [43]. |

| Alt-R gRNA (crRNA + tracrRNA) | Guides Cas9 to the specific genomic target. | Lyophilized, stable 1 year at -20°C; resuspend in nuclease-free water or IDTE [43]. |

| Electroporation Enhancer | Increases HDR efficiency in primary cells. | Stable 1 year at -20°C in a sealed container [43]. |

| HDR Donor Template | DNA template for precise knock-in via homologous recombination. | Design with ~800 bp homology arms; use ssDNA for point mutations, dsDNA for large insertions. |