Decoding Life's Beginnings: A Comprehensive Guide to Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition with Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is revolutionizing our understanding of the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT), a fundamental process in early embryonic development.

Decoding Life's Beginnings: A Comprehensive Guide to Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition with Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is revolutionizing our understanding of the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT), a fundamental process in early embryonic development. It explores the foundational biology of MZT across species, details cutting-edge methodological approaches like metabolic RNA labeling, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for experimental design, and establishes frameworks for validating findings and benchmarking embryo models. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes the latest advances to empower robust and insightful MZT research, with implications for understanding infertility, congenital diseases, and regenerative medicine.

Unveiling MZT: From Foundational Biology to Single-Cell Resolution

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) is a fundamental, highly conserved process in animal embryogenesis that represents the first major developmental handoff [1] [2]. This critical transition encompasses the coordinated transfer of developmental control from gene products stored in the egg by the mother to those synthesized from the newly formed zygotic genome [3]. The MZT is not merely a switch but an intricately orchestrated sequence comprising three interdependent events: the targeted degradation of a subset of maternal mRNAs, the robust activation of zygotic transcription, and a fundamental remodeling of the cell cycle [1]. The precision of this handoff is paramount, as failure to execute any component correctly leads to developmental arrest [2]. This review delineates the defining molecular events, regulatory principles, and innovative methodologies used to dissect the MZT, framing this knowledge within the context of modern single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) research.

Quantitative Dynamics of the MZT

The MZT unfolds through a tightly coupled series of molecular events. Understanding its quantitative dynamics provides a foundation for probing its regulatory logic.

Table 1: Core Events of the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition

| Developmental Event | Key Activities | Representative Model Organisms & Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Control Phase | - Development driven by maternally deposited mRNAs and proteins.- Post-transcriptional regulation (mRNA localization, translation, stability).- Rapid, synchronous cleavage divisions with no gap phases. | Drosophila: Pre-MBT; cycles 1-13 [2]Zebrafish: Pre-MBT; ~3 hours post-fertilization (hpf) [4] |

| Zygotic Genome Activation (ZGA) | - Minor wave: Activation of hundreds of genes.- Major wave: Activation of thousands of genes. | Drosophila: Minor wave at cycle 8; major wave at cycle 14 [2]Zebrafish: Minor wave during cleavage; major wave post-MBT [4] |

| Maternal mRNA Clearance | - Maternal degradation pathway: Maternally encoded factors (e.g., SMG, BRAT).- Zygotic degradation pathway: Zygotically transcribed factors (e.g., miR-309 in Drosophila, miR-430 in zebrafish). | Occurs concurrently with ZGA, ensuring handover of developmental control [1] [2] |

| Cell Cycle Remodeling | - Introduction of gap phases (G1, G2).- Lengthening of S-phase.- Onset of cellular differentiation. | Coincides with major ZGA (e.g., cycle 14 in Drosophila) [1] [2] |

Recent proteomic studies in zebrafish have quantified the scale of this transition, revealing the expression dynamics of approximately 5,000 proteins across four key developmental stages (64-cell to 50% epiboly) during the MZT [4]. This work identified nearly 700 differentially expressed proteins, clustering into six distinct temporal patterns that directly reflect the main events of the MZT: ZGA, maternal transcript clearance, and the initiation of organogenesis [4]. A significant finding was the observation of notable discrepancies between transcriptome and proteome profiles, underscoring the critical importance of post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms and the value of multi-omics approaches [4].

Table 2: Key Molecular Regulators of the MZT

| Regulator Category | Key Factors/Families | Primary Function in the MZT |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Zelda, Nanog, Ctcf, Pou5f3 | Pioneering transcription factors that drive ZGA by binding and opening chromatin [4] [2]. |

| RNA-Binding Proteins (RBPs) | Staufen, SMG, BRAT, PUM | Post-transcriptional control of maternal mRNAs; regulate localization, translation, and stability; initiate maternal mRNA decay [2]. |

| Small Non-coding RNAs | miR-309 (Drosophila), miR-430 (Zebrafish), miR-427 (Xenopus) | Zygotically expressed microRNAs that target hundreds of maternal mRNAs for degradation [2]. |

| Chromatin Modifiers | Histone-modifying enzymes, Histone variants | Remodel chromatin accessibility and architecture to facilitate ZGA [4] [3]. |

Regulatory Principles Governing the MZT

The Initiation of Development by Maternal Factors

Before the zygotic genome awakens, the embryo is entirely dependent on maternally deposited mRNAs and proteins. This period is characterized by exclusive post-transcriptional control, where RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) regulate mRNA localization, translation, and stability via cis-acting elements in the transcripts [2]. A quintessential example is the RBP Staufen, which is essential for the localization of maternal mRNAs like bicoid and oskar that establish the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo [2]. Translational control is also exerted through poly(A) tail elongation, a developmentally regulated process that enhances the translation efficiency of specific maternal mRNAs and disappears after gastrulation [2].

The Activation of the Zygotic Genome

Zygotic genome activation is the central event of the MZT. It is not a sudden switch but a gradual process, often involving a minor and a major wave of transcription [2]. The timing of ZGA is intimately linked to a critical developmental milestone known in many species as the mid-blastula transition (MBT) [1]. The onset of ZGA is controlled by a combination of factors:

- Transcription Factors: Pioneering factors like Zelda in Drosophila are crucial for activating the zygotic genome by binding to regulatory sequences and promoting an open chromatin state [2].

- Chromatin Remodeling: A remarkable epigenetic reprogramming occurs after fertilization, involving global DNA demethylation, changes in histone post-translational modifications, and reorganization of the 3D genome architecture, which collectively help restore totipotency and facilitate ZGA [3].

- Cis-Regulatory Elements: The activation of enhancers is a key step in initiating the zygotic genetic program [3].

The Clearance of Maternal Instructions

To complete the handoff of developmental control, the maternal molecular legacy must be erased. This clearance is achieved through the concerted action of two RNA decay pathways [2]:

- The Maternal Degradation Pathway: Triggered after egg activation, this pathway relies on maternally encoded RBPs like SMG, BRAT, and PUM. These factors recruit decay machinery, such as the CCR4/NOT deadenylase complex, to target specific maternal transcripts for destruction [2].

- The Zygotic Degradation Pathway: This pathway is activated slightly later and depends on new transcripts from the zygotic genome, notably microRNAs like the miR-309 cluster in Drosophila and miR-430 in zebrafish. These zygotically expressed miRNAs accelerate the degradation of hundreds of maternal mRNAs, ensuring their removal is coupled to the activation of their replacements [2].

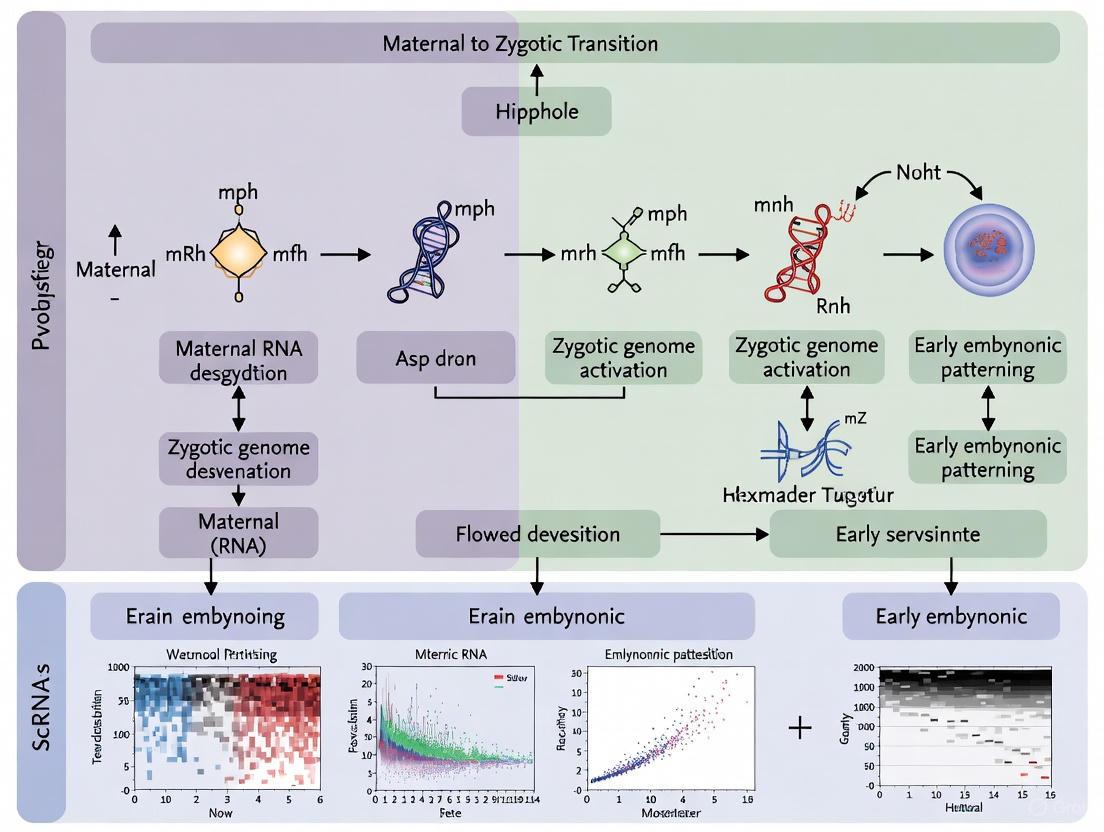

Diagram 1: Regulatory logic of the MZT handoff.

The MZT in an Evolutionary Context

Despite the core functions of the MZT being deeply conserved, the specific gene transcripts that execute this program show surprising evolutionary dynamism. Comparative transcriptomics across 14 Drosophila species spanning over 50 million years of evolution revealed a "core" set of zygotically transcribed genes, highly enriched for transcription factors with critical roles in early development [5]. This core is conserved over 250 million years, extending to mosquitoes. However, the broader pools of maternal and zygotic transcripts show considerable variation between species [5]. While the expression levels of maternally deposited transcripts are generally more conserved than those of zygotic genes, the specific maternal transcripts that are completely degraded during the MZT are among the fastest-evolving [5]. This suggests that while the fundamental logic of the MZT is constrained, there is significant flexibility in the genetic components that implement it, potentially as an adaptation for development in different environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: scRNA-seq for MZT Analysis

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the study of the MZT by allowing researchers to deconstruct the transcriptomes of individual cells within a developing embryo, moving beyond bulk tissue measurements and revealing unprecedented cellular heterogeneity [6] [7]. The standard analytical workflow for scRNA-seq data involves several key steps, each with established best practices and computational tools [6] [8].

Key Experimental and Computational Protocols

A. Wet-Lab Experimental Protocol: Single-Cell Dissociation and Library Preparation

- Sample Collection: Precisely stage and collect embryos at timepoints spanning the MZT (e.g., before, during, and after MBT) [4].

- Single-Cell Suspension: Generate a single-cell suspension through enzymatic and/or mechanical dissociation of the embryonic tissue. Care must be taken to maintain cell viability while achieving complete dissociation [6].

- Single-Cell Isolation & Barcoding: Use a high-throughput platform (e.g., 10x Genomics) to isolate individual cells into nanoliter-scale droplets or wells, each containing a unique cellular barcode and Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI). This step labels all mRNA from a single cell with the same barcode [6].

- Library Construction & Sequencing: Inside each droplet/well, cells are lysed, and mRNA is reverse-transcribed into barcoded cDNA. The cDNA is amplified, and sequencing libraries are constructed. The pooled libraries are then sequenced on a high-throughput platform [6].

B. Computational Protocol: scRNA-seq Data Analysis The following workflow outlines current best practices for analyzing the resulting data [6] [8]:

- Raw Data Preprocessing: Use pipelines like Cell Ranger (for 10x Genomics data) to perform quality control on raw sequencing reads, demultiplex cellular barcodes, align reads to a reference genome, and generate a gene-barcode count matrix [6] [8].

- Quality Control (QC) & Filtering: Filter the count matrix to remove low-quality cells. Standard QC metrics include [6]:

- Count depth: The total number of molecules per barcode.

- Number of genes detected: Barcodes with very high counts may be doublets, while those with very low counts may be empty droplets or dead cells.

- Mitochondrial read fraction: A high percentage suggests cytoplasmic mRNA loss from broken membranes.

- Normalization & Dimensionality Reduction: Normalize the data to account for technical variability (e.g., sequencing depth). Identify highly variable genes and perform principal component analysis (PCA). Further reduce dimensions using non-linear techniques like UMAP or t-SNE for visualization [6] [8].

- Clustering & Cell Type Annotation: Graph-based clustering is performed on the reduced dimensions to group transcriptionally similar cells. These clusters are then annotated as specific cell types or states using known marker genes [6].

- Downstream Analysis:

- Differential Expression: Identify genes that are differentially expressed between clusters or across experimental conditions.

- Trajectory Inference: Use tools like Monocle 3 or Velocyto to reconstruct developmental pathways and infer the temporal ordering of cells along a differentiation trajectory, which is particularly powerful for studying the progression through the MZT [8].

Diagram 2: From embryos to insights via scRNA-seq.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for MZT and scRNA-seq Research

| Item/Tool Name | Category | Function in MZT/scRNA-seq Research |

|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Model Organism | Vertebrate model with external development, genetic tractability, and rapid MZT for functional studies [4]. |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Model Organism | Invertebrate model with well-characterized genetics, rapid syncytial development, and extensive MZT regulatory knowledge [2] [5]. |

| Seurat | Computational Tool | Comprehensive R toolkit for scRNA-seq data analysis, including QC, integration, clustering, and visualization [6] [8]. |

| Scanpy | Computational Tool | Scalable Python-based toolkit for analyzing large-scale scRNA-seq datasets, integrated within the scverse ecosystem [8]. |

| Cell Ranger | Computational Tool | Standardized pipeline for processing raw 10x Genomics sequencing data into gene-barcode count matrices [8]. |

| Monocle 3 | Computational Tool | Software package for inferring developmental trajectories and pseudotime ordering from scRNA-seq data [8]. |

| scvi-tools | Computational Tool | Deep generative modeling framework for advanced tasks like robust batch correction and imputation [8]. |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) | Molecular Reagent | Short nucleotide barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules, allowing for accurate quantification and reduction of amplification noise [6]. |

The maternal-to-zygotic transition is a cornerstone of animal development, a exquisitely timed process where control is passed from one generation to the next. Defining the MZT requires integrating our understanding of molecular regulation—from chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation to mRNA decay—with dynamic changes in cell cycle structure and the emergence of cellular diversity. The integration of advanced technologies, particularly single-cell multi-omics and sophisticated computational tools like machine learning, is pushing the boundaries of our knowledge [7]. These approaches are transforming the MZT from a well-described biological phenomenon into a deeply understood, modelable system. By continuing to dissect the regulatory principles and evolutionary dynamics of this critical handoff, researchers will not only illuminate the fundamental beginnings of life but also advance the frontiers of regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) is a fundamental process in early animal embryogenesis that represents the first major developmental handover, shifting control from maternally deposited gene products to those synthesized from the zygotic genome [1]. This highly coordinated event is characterized by two interdependent molecular hallmarks: the clearance of maternal RNAs and zygotic genome activation (ZGA) [9]. The MZT unfolds with remarkable temporal precision across species, driven by complex feedback mechanisms that ensure developmental progression is both robust and timely [1]. During the initial phases of development, the embryo relies entirely on maternal mRNAs and proteins stored in the oocyte, as the zygotic genome remains transcriptionally silent. The MZT marks the critical juncture where these maternal components are degraded and developmental control is transferred to the newly activated zygotic genome [9]. The timing and regulation of these events exhibit species-specific variations but follow a conserved logic essential for embryonic viability [9].

Table 1: MZT Timing Across Model Organisms

| Organism | Maternal mRNA Clearance | ZGA Initiation | Major ZGA Wave |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | Begins upon fertilization [9] | Minor wave at ~2.3 hpf [10] | 10 cell cycles post-fertilization [9] |

| Drosophila | Destabilized upon egg activation [9] | Cleavage cycles 8-14 [9] | Increases rapidly until cycle 14 [9] |

| Mouse | Degraded by two-cell stage [9] | One-cell stage [9] | Two-cell stage [11] |

| Human | Elimination between 4-8 cell stage [9] | 4-8 cell stage [9] | 4-8 cell stage [12] |

| Xenopus | Begins immediately after fertilization [9] | Not specified | 6 hours post-fertilization [9] |

| Pig | Gradual decay from 1- to 8-cell [11] | Minor ZGA at 1-cell [13] [11] | Major ZGA at 4-cell [13] [11] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Maternal RNA Clearance

Pathways for Maternal mRNA Degradation

The clearance of maternal mRNAs is an active and highly selective process essential for normal development. In Drosophila, the Pan gu (PNG) Ser/Thr kinase complex plays a pivotal role by promoting the translation of the RNA-binding protein Smaug (SMG) following egg activation [9]. Smaug then recruits the CCR4/POP2/NOT deadenylase complex to initiate poly(A) tail shortening and subsequent mRNA decay [9]. This pathway is responsible for degrading approximately two-thirds of unstable maternal mRNAs [9]. In vertebrates such as mouse, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), which triggers the phosphorylation and degradation of CPEB1. This in turn stimulates polyadenylation and translational activation of BTG4, which recruits the CCR4-NOT deadenylation complex to target mRNAs [9].

Regulation by RNA-Binding Proteins (RBPs) and Post-Translational Modifications

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) serve as critical mediators of maternal mRNA stability, functioning as adaptors that direct the degradation machinery to specific transcript subsets [9]. Proteome-wide studies in Drosophila embryos have identified 523 high-confidence RBPs, half of which were previously unknown to bind RNA, revealing the extensive and dynamic nature of the RNA-bound proteome during the MZT [14]. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) provide an essential regulatory layer for controlling RBP activity and function. In Xenopus, the embryonic deadenylation element-binding protein (EDEN-BP) recognizes U-rich embryonic deadenylation elements to trigger deadenylation of target transcripts [9]. Meanwhile, phosphorylation of Pumilio (PUM) during oocyte maturation induces conformational changes that regulate the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of specific mRNAs [9].

Diagram Title: Maternal mRNA Clearance Pathways in Drosophila and Mouse

Zygotic Genome Activation: Timing and Transcriptional Regulation

Waves of Zygotic Genome Activation

ZGA occurs in distinct temporal waves across species, typically categorized as minor and major phases [11]. The minor ZGA involves limited activation of a specific gene set that is essential for subsequent developmental programming, while the major ZGA represents broad-scale transcriptional activation of the zygotic genome [13]. In mice, minor ZGA initiates at the one-cell stage followed by major ZGA at the two-cell stage [13] [11]. Conversely, pigs and humans exhibit similar ZGA timing, with minor activation around the one-cell stage and major activation occurring between the four-cell to eight-cell stages [13] [11] [12]. A recent single-cell RNA-seq study in pigs confirmed that minor and major ZGAs occur at 1-cell and 4-cell stages, respectively, for both in vitro fertilized (IVF) and parthenogenetically activated (PA) embryos [11].

Transcription Factor Networks and Epigenetic Regulation

The initiation of ZGA depends on the accumulation of key transcriptional regulators to threshold levels [13]. DUX was identified as the initial transcription factor responsible for initiating zygotic transcription in both mouse and human embryos [13]. The pluripotency factors POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG, c-MYC, and KLF4—famous for their role in cellular reprogramming—also play significant roles in ZGA [13]. The relationship between SOX2 and POU5F1 is particularly close and interdependent, forming a core transcriptional module [13]. Epigenetic reprogramming is equally critical for ZGA, involving comprehensive DNA demethylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling that collectively establish a permissive environment for zygotic transcription [13] [11]. In pigs, global epigenetic modification patterns diverge during minor ZGA and expand further, with in vivo-developed (IVV) embryos showing more active regulation of genes linked to H4 acetylation and H2 ubiquitination, while parthenogenetic embryos display increased H3 methylation [13].

Table 2: Key Transcription Factors and Epigenetic Regulators in ZGA

| Regulator Category | Key Factors | Functional Role in ZGA | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | DUX | Initial transcription factor for ZGA initiation | Mouse, Human [13] |

| POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG | Pluripotency network, zygotic genome activation | Multiple [13] | |

| c-MYC, KLF4 | Reprogramming factors, zygotic transcription | Multiple [13] | |

| Chromatin Remodelers | SMARCB1 | Chromatin remodeling (in vivo embryos) | Pig [13] |

| SIRT1, EZH2 | Chromatin modification (in vitro embryos) | Pig [13] | |

| Histone Modifications | H4 acetylation, H2 ubiquitination | Active epigenetic marks in IVV embryos | Pig [13] |

| H3 methylation | Increased in parthenogenetic embryos | Pig [13] |

Advanced Single-Cell RNA-seq Technologies for MZT Analysis

Metabolic Labeling for Distinguishing Maternal and Zygotic Transcripts

Traditional scRNA-seq methods capture transcriptome snapshots but cannot distinguish newly transcribed zygotic mRNAs from pre-existing maternal transcripts. To overcome this limitation, researchers have developed innovative approaches combining scRNA-seq with metabolic labeling [10]. In zebrafish embryos, injection of 4-thiouridine triphosphate (4sUTP) at the one-cell stage enables selective incorporation into newly transcribed RNAs [10]. A chemical conversion step then creates characteristic T-to-C changes in sequencing reads, allowing precise quantification of zygotic transcripts. This method revealed that zygotic mRNAs account for only 13% of cellular mRNAs at the dome stage (4.3 hpf), increasing to 41% by the 50% epiboly stage (5.3 hpf) [10]. Application of GRAND-SLAM analysis to this data enables statistical inference of labeled fractions, accurately distinguishing maternal and zygotic transcripts with labeled fractions <3.5% for maternal genes and >80% for zygotic genes [10].

Integrated Multi-Omic Approaches

Combining scRNA-seq with other single-cell modalities provides unprecedented insights into the coordination of transcriptional and epigenetic regulation during MZT. Single-cell methylome and transcriptome sequencing (scM&T-seq) has been applied to human oocytes and pre-implantation embryos, enabling simultaneous profiling of DNA methylation and gene expression [12]. This approach has identified distinct genes and molecular pathways for early developmental stages and revealed that trophectoderm differentiation occurs largely independent of DNA methylation [12]. Critically, comparison between developmentally high-quality embryos and those undergoing spontaneous cleavage-stage arrest demonstrated that arrested embryos frequently fail to appropriately accomplish embryonic genome activation and epigenetic reprogramming [12].

Diagram Title: scRNA-seq Metabolic Labeling Workflow for MZT Analysis

Computational Tools for scRNA-seq Analysis in MZT Research

The analysis of scRNA-seq data from early embryos presents unique computational challenges due to the high dimensionality, sparsity, and technical noise inherent in these datasets. Several specialized computational methods have been developed to address these challenges. scHSC is a deep learning method that employs hard sample mining through contrastive learning for clustering scRNA-seq data, simultaneously integrating gene expression and topological structure information between cells to improve clustering accuracy [15]. Other tools like SC3 utilize a consensus clustering framework specifically designed for single-cell RNA-seq data, employing PCA and Laplacian transformations to reduce dimensionality [15]. For trajectory inference, URD is used to perform dimensionality reduction, UMAP projection, and clustering of embryonic cells, enabling reconstruction of developmental pathways [10].

Comparative Analysis of In Vivo vs. In Vitro Embryo Development

Transcriptomic and Epigenetic Differences

Single-cell RNA-seq analyses have revealed substantial differences between in vivo-developed (IVV) embryos and those generated through assisted reproductive technologies (ART). In pigs, in vitro embryos (IVF and parthenogenetically activated) exhibit more similar developmental trajectories compared to IVV embryos, with PA embryos showing the least gene diversity at each stage [13]. Significant variations occur in maternal mRNA handling, particularly affecting mRNA splicing, energy metabolism, and chromatin remodeling [13]. While ZGA timing is similar across embryo types, IVV embryos demonstrate more pronounced upregulation of genes during major ZGA and distinct epigenetic modification patterns [13]. Specifically, IVV embryos uniquely upregulate genes linked to mitochondrial function, ATP synthesis, and oxidative phosphorylation during major ZGA [13].

mRNA Degradation Dynamics

A notable difference between in vivo and in vitro embryos concerns the timing and specificity of maternal mRNA degradation. In IVV embryos, maternal mRNA degradation occurs in a timely manner, while in vitro embryos exhibit delayed clearance of specific transcript categories [13]. Maternal genes regulating phosphatase activity and cell junctions, while highly expressed in both embryo types, are properly degraded in IVV but not in in vitro embryos [13]. This defective clearance likely contributes to the developmental challenges observed in ART-derived embryos, including irregular cell morphology, slower cleavage rates, and lower embryonic formation rates [13].

Table 3: Metabolic and Energetic Differences in Early Embryos

| Parameter | In Vivo Developed (IVV) Embryos | In Vitro Produced Embryos |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Metabolism | Upregulation of mitochondrial function, ATP synthesis, oxidative phosphorylation [13] | Altered energy metabolism pathways [13] |

| Mitochondrial Genes | Higher nucleosome occupancy and ATP8 expression [13] | Higher expression of many mitochondrially encoded genes [13] |

| Chromatin Remodeling | SMARCB1 and HDAC1 as key regulators [13] | SIRT1 and EZH2 as central regulators [13] |

| Maternal mRNA Clearance | Timely degradation of maternal mRNAs [13] | Defective clearance of specific maternal mRNAs [13] |

| Metabolic Substrates | Lipids as major energy source [13] | Altered substrate utilization in culture [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for MZT Research

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function/Utility | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4sUTP (4-thiouridine triphosphate) | Metabolic labeling | Incorporates into newly transcribed RNA to distinguish zygotic from maternal transcripts [10] | Quantifying zygotic transcript accumulation in zebrafish embryos [10] |

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | RNA interactome capture | Isolates polyadenylated RNAs under denaturing conditions for RBP identification [14] | Identifying RNA-binding proteins in Drosophila embryos [14] |

| scM&T-seq Protocol | Multi-omic profiling | Simultaneous measurement of mRNA expression and DNA methylation at single-cell resolution [12] | Correlating epigenetic reprogramming with transcriptional activation in human embryos [12] |

| Drop-Seq | Single-cell RNA-seq | High-throughput single-cell transcriptome profiling using microfluidics [10] | Profiling thousands of individual embryonic cells [10] |

| URD | Computational analysis | Dimensionality reduction, UMAP projection, and trajectory inference for scRNA-seq data [10] | Reconstructing developmental pathways from embryonic single-cell data [10] |

| GRAND-SLAM | Computational analysis | Estimates fraction of newly transcribed mRNA from metabolic labeling data [10] | Distinguishing maternal and zygotic transcript fractions in single cells [10] |

The maternal-to-zygotic transition represents a critically important period in embryonic development, integrating the coordinated processes of maternal mRNA clearance and zygotic genome activation through sophisticated molecular mechanisms. The emergence of advanced single-cell technologies, particularly metabolic labeling scRNA-seq and multi-omic approaches, has revolutionized our ability to dissect these events with unprecedented resolution. These methods have revealed the complex regulatory networks involving RNA-binding proteins, transcription factors, and epigenetic modifications that ensure proper timing of the MZT across species. Furthermore, comparative analyses of in vivo and in vitro embryos have identified key deficiencies in ART-derived embryos, providing insights that may ultimately improve assisted reproduction outcomes. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield deeper understanding of this fundamental biological transition and its implications for developmental biology and reproductive medicine.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents a critical developmental milestone where control of embryonic development shifts from maternally-deposited factors to the newly activated zygotic genome. This process involves two coordinated molecular events: degradation of maternal mRNAs and zygotic genome activation (ZGA). The timing and regulation of MZT vary significantly across species, with important implications for developmental biology and biomedical research. This technical review synthesizes current knowledge on MZT timelines in human, mouse, zebrafish, and Drosophila models, leveraging single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies to provide unprecedented resolution of these transitions. We present comparative quantitative data, detailed methodological frameworks for MZT analysis, and practical resources for researchers investigating this fundamental biological process across model systems.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition is a conserved process in animal embryogenesis characterized by the degradation of maternally-provided mRNAs and the subsequent activation of transcription from the zygotic genome. This transition is essential for continued embryonic development and represents the first major transcriptional event in the life of an organism. The development of scRNA-seq technologies has revolutionized our ability to study MZT at single-cell resolution, enabling detailed characterization of transcriptional dynamics and cellular heterogeneity during early development [16] [10].

Metabolic labeling techniques combined with scRNA-seq now allow researchers to distinguish newly transcribed zygotic mRNAs from pre-existing maternal transcripts, providing unprecedented insights into the temporal regulation of ZGA [10] [17]. These technological advances have revealed both conserved and species-specific aspects of MZT regulation across different model organisms, with implications for understanding embryonic development, regenerative medicine, and evolutionary biology.

Comparative Timelines of MZT Across Species

The timing of MZT events varies considerably across species, reflecting differences in embryonic development strategies, cell cycle regulation, and genetic programs. The table below summarizes key temporal milestones in the MZT process for human, mouse, zebrafish, and Drosophila models:

Table 1: Comparative MZT Timelines Across Model Species

| Species | Fertilization to First Cleavage | Minor ZGA Onset | Major ZGA Onset | MZT Completion | Key Developmental Stages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 24-30 hours | 4-cell stage | 8-cell stage | 8-cell to morula | Slow development; extended embryonic phases |

| Mouse | 18-24 hours | 1-cell stage | 2-cell stage | 2-cell to 4-cell | Rapid ZGA; compact timeline |

| Zebrafish | ~45 minutes | 2.3 hours post-fertilization (hpf) | 3.3 hpf | ~5.3 hpf | External development; visible embryos |

| Drosophila | ~25 minutes | Cycle 8-10 | Cycle 14 | Cellularization | Syncytial divisions; mid-blastula transition |

In mice, minor ZGA initiates at the one-cell stage, followed by major ZGA at the two-cell stage [13]. This compact timeline contrasts with humans and pigs, where minor ZGA occurs around the four-cell stage and major ZGA around the eight-cell stage [13]. Zebrafish embryos begin minor ZGA at approximately 2.3 hours post-fertilization (hpf), with the major wave of ZGA commencing at 3.3 hpf [10]. The MZT in zebrafish is largely complete by 5.3 hpf, coinciding with the 50% epiboly stage [10]. Drosophila follows a distinct pattern characterized by rapid syncytial divisions, with ZGA occurring in cycles 8-14 and MZT completion at cellularization [16].

Table 2: Key Molecular Features of MZT Across Species

| Species | Maternal mRNA Degradation Trigger | Critical Transcription Factors | Chromatin Remodeling Features | Metabolic Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Embryonic genome activation | DUX, POU5F1, NANOG | Gradual chromatin reorganization | Pyruvate-dependent |

| Mouse | Fertilization | DUX, POU5F1, SOX2 | Rapid epigenetic reprogramming | Pyruvate-dependent |

| Zebrafish | miR-430 activation | Nanog, Pou5f3, SoxB1 | Dynamic histone modifications | Mixed substrate utilization |

| Drosophila | Mid-blastula transition | Zelda, Bicoid | ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling | Yolk-dependent |

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Methodologies for MZT Analysis

Metabolic Labeling Approaches

Metabolic RNA labeling with nucleoside analogs (e.g., 4-thiouridine [4sU], 5-ethynyluridine [5EU], or 6-thioguanosine [6sG]) enables distinguishing newly synthesized zygotic transcripts from maternal mRNAs during MZT [10] [17]. The incorporation of these analogs creates chemical tags detectable through sequencing by identifying characteristic base conversions (T-to-C for 4sU).

Benchmark studies have identified optimal chemical conversion methods for scRNA-seq applications. The mCPBA/TFEA (meta-chloroperoxy-benzoic acid/2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine) combination at pH 5.2 demonstrates superior performance with high T-to-C substitution rates (8.11%) while maintaining RNA integrity and recovery rates [17]. On-beads conversion methods generally outperform in-situ approaches, achieving 2.32-fold higher substitution rates [17].

scRNA-seq Platform Selection

The choice of scRNA-seq platform significantly impacts data quality for MZT studies:

- Drop-seq: Customizable platform enabling on-beads chemical conversion; lower cell capture rate (~5%) but flexibility in protocol adaptation [17]

- 10x Genomics: Commercial platform with higher capture efficiency (~50%); suitable for limited cell numbers in early embryos [17]

- Combinatorial barcoding (e.g., Parse Evercode): Hardware-free approach working with fixed cells of any model organism; enables longitudinal studies with minimal batch effects [18]

Experimental Workflow for Zebrafish MZT Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a optimized experimental workflow for studying MZT in zebrafish embryos using metabolic labeling and scRNA-seq:

Data Analysis Pipeline

Analysis of scRNA-seq data from metabolically labeled embryos involves specialized computational approaches:

- GRAND-SLAM analysis: Statistical method to determine the fraction of newly-transcribed zygotic mRNA from T-to-C conversions for each gene in each cell [10]

- Pseudotime reconstruction: Algorithms like UMAP and pseudotime ordering to reconstruct developmental trajectories [10]

- Kinetic modeling: Mathematical models to quantify mRNA transcription and degradation rates within individual cell types during specification [10]

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks in MZT

The MZT is governed by complex regulatory networks involving transcription factors, non-coding RNAs, and signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory architecture controlling MZT across species:

Transcription Factor Networks

Key transcription factors play conserved roles in ZGA across species:

- DUX: Initiates transcription in early mouse and human embryos [13]

- POU5F1 (OCT4), SOX2, NANOG: Core pluripotency factors involved in zygotic genome activation across mammals [13]

- Zelda: Pioneering transcription factor critical for ZGA in Drosophila [16]

Non-Coding RNA Regulation

Non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs, play crucial roles in MZT regulation:

- miR-430 (zebrafish) and miR-427 (Xenopus): Trigger massive degradation of maternal mRNAs during MZT [10]

- Long non-coding RNAs: Exhibit stage-specific expression during MZT and participate in ceRNA (competing endogenous RNA) networks that fine-tune gene expression [19]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MZT scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Labeling Reagents | 4sU (4-thiouridine), 5EU (5-ethynyluridine), 6sG (6-thioguanosine) | Incorporates into newly synthesized RNA for detection | 100 μM 4sU for 4 hours effective for zebrafish embryos [17] |

| Chemical Conversion Kits | mCPBA/TFEA pH 5.2, IAA (iodoacetamide), NaIO4/TFEA | Converts labeled nucleotides for detection | mCPBA/TFEA pH 5.2 provides optimal conversion efficiency [17] |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Drop-seq, 10x Genomics, Parse Evercode, MGI C4 | Single-cell transcriptome profiling | Choose based on cell capture efficiency needs and model organism [18] [17] |

| Cell Fixation Reagents | Methanol, Paraformaldehyde | Preserves cellular RNA for delayed processing | Methanol fixation effective for preserving zebrafish embryonic cells [17] |

| Analysis Pipelines | GRAND-SLAM, dynast, Seurat, Scanpy | Computational analysis of scRNA-seq data | GRAND-SLAM specifically designed for metabolic labeling data [10] [17] |

Comparative Analysis of MZT Across Species

Conservation and Divergence in MZT Regulation

Despite fundamental differences in MZT timing, several aspects of this process are conserved across species:

- Dynamics of maternal mRNA clearance: All species exhibit coordinated degradation of maternal transcripts, though the specific triggers and timing vary [13] [10]

- Chromatin remodeling: Epigenetic reprogramming is essential for ZGA across species, though the specific modifications and enzymes involved show variation [13]

- Transcription factor networks: Core pluripotency factors maintain conserved roles in ZGA, though their specific expression patterns and downstream targets may differ [16] [13]

Species-Specific Adaptations

Each model organism exhibits unique adaptations in MZT regulation:

- Zebrafish: Rapid external development with high fecundity; exceptional transparency enables live imaging of MZT processes [18] [10]

- Drosophila: Syncytial nuclear divisions preceding cellularization; well-defined genetic toolkit for functional studies [16]

- Mouse: Compact MZT timeline with early ZGA; ideal for genetic manipulation and modeling human development [16] [13]

- Human: Extended preimplantation development; ethical and technical limitations for functional studies [13]

The comparative analysis of MZT across model species reveals both conserved fundamental principles and species-specific adaptations. scRNA-seq technologies, particularly when combined with metabolic labeling approaches, provide powerful tools for dissecting the temporal progression and regulatory architecture of this critical developmental transition. The integration of cross-species datasets, such as those compiled in the Cell Landscape resource [16], enables researchers to identify core conserved pathways and species-specific innovations.

Future research directions include developing improved computational methods for integrating temporal and spatial information during MZT [20], optimizing low-input scRNA-seq protocols for limited cell numbers in early embryos, and applying single-cell multi-omics approaches to simultaneously profile transcriptional and epigenetic dynamics during this crucial developmental window. These technical advances will further enhance our understanding of MZT across species and provide insights with broad implications for developmental biology, regenerative medicine, and evolutionary studies.

{#context} Within the broader context of maternal to zygotic transition (MZT) research, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of early mammalian development. This technical guide details how scRNA-seq enables the precise mapping of the transcriptional journey from a single totipotent zygote to the formation of multipotent germ layers, providing unprecedented insights into cell fate decisions for researchers and drug development professionals.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents the foundational period in embryonic development when control shifts from maternal transcripts to the activated zygotic genome. This process, encompassing zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and the degradation of maternal RNAs, initiates the developmental cascade toward cellular diversification [19] [21]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative technology for investigating this opaque phase of life, allowing for the systematic, high-resolution dissection of transcriptional dynamics in individual cells of the early embryo [22] [23].

By enabling the profiling of thousands of genes across hundreds to millions of individual cells, scRNA-seq moves beyond bulk measurements that obscure cellular heterogeneity. This capability is crucial for understanding the progression from totipotency—the potential of a single cell to generate all embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues—to pluripotency and subsequent lineage specification into the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) [24] [25]. This guide synthesizes current experimental protocols, key transcriptional findings, and computational tools that together form a comprehensive framework for mapping lineage specification using scRNA-seq.

Technological Foundations of scRNA-seq in Development

The application of scRNA-seq to early embryos presents unique challenges, including the scarcity of biological material and the minute amounts of RNA per cell. The fundamental workflow begins with the dissociation of embryonic cells or stem cell models into single-cell suspensions. Subsequently, cells are lysed, and the released mRNA is captured, reverse-transcribed into cDNA, and amplified, often using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to control for amplification biases [23] [26]. The resulting libraries are sequenced and computationally analyzed.

Key Computational and Visualization Methods

Downstream analysis transforms high-dimensional transcriptomic data into biological insights. Standard steps include quality control, normalization, and dimensionality reduction using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Cells are then clustered based on transcriptional similarity, and their relationships are visualized in two-dimensional space using methods such as:

- Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP): Ideal for visualizing both local and global relationships in the data. It is often the default method for exploring cellular populations [26] [27].

- t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE): Emphasizes local structures and fine population details, useful for detailed cluster analysis [26].

- scBubbletree: A recent method that addresses overplotting in large datasets by visualizing clusters as "bubbles" on a dendrogram, providing quantitative summaries of cluster properties and relationships [27].

Differential expression analysis and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) further identify marker genes and activated pathways distinguishing different cell states and lineages [26]. Deep learning models, such as those built with scvi-tools, are increasingly used to integrate multiple datasets and build robust classifiers for cell types and states across development [23].

Figure 1: A generalized computational workflow for analyzing scRNA-seq data from early embryos. The process flows from raw sample to quality-controlled (QC), normalized data, through dimensionality reduction (DimRed) and clustering, culminating in visualization (Viz) and differential expression (DE) analysis. {#fig1}

Charting the Transition from Totipotency to Lineage Commitment

Defining Totipotency and the Zygotic Genome Activation

The totipotent zygote undergoes cleavage divisions, and in mice, a major wave of ZGA occurs at the 2-cell stage, while in humans, it occurs at the 4- to 8-cell stage [24] [23]. scRNA-seq has been instrumental in characterizing the transcriptome of these early stages. A defining feature of mouse totipotent cells is the robust expression of endogenous retroviral elements (e.g., MERVL) and genes like the ZSCAN4 cluster [24].

Studies have identified a rare, transient population within mouse Embryonic Stem Cell (ESC) cultures, termed 2-cell-like cells (2CLCs), which recapitulate this MERVL-positive and ZSCAN4-positive totipotent transcriptome, providing a valuable in vitro model for studying totipotency [24]. The nuclear receptor NR5A2 has been identified as a critical transcription factor bridging ZGA and later lineage specification. Depletion of Nr5a2 in mouse embryos leads to a failure to activate 4-8C specific genes and subsequent arrest at the morula stage, underscoring its role as a key regulator of the developmental continuum [25].

From Morula to Blastocyst: The First Lineage Decisions

The first major lineage segregation occurs at the blastocyst stage, giving rise to the trophectoderm (TE), which forms extra-embryonic structures, and the inner cell mass (ICM). The ICM further differentiates into the epiblast (EPI), which gives rise to the embryo proper, and the primitive endoderm (PrE) [22] [23]. scRNA-seq has enabled the precise definition of the transcriptomic signatures defining these lineages.

Table 1: Key Lineage-Specific Marker Genes Identified by scRNA-seq in Human and Mouse Preimplantation Embryos {#tbl1}

| Lineage | Key Marker Genes | Species | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trophectoderm (TE) | GATA2, GATA3, GATA4, CDX2 | Human & Mouse | Formation of extra-embryonic tissues, including placenta [22] [23] |

| Epiblast (EPI) | NANOG, SOX2, POU5F1/OCT4 | Human & Mouse | Pluripotency; forms the embryo proper [22] [23] |

| Primitive Endoderm (PrE) | GATA6, PDGFRA | Human & Mouse | Forms the yolk sac [22] [23] |

| Totipotent/2C-like | ZSCAN4 (cluster), MERVL elements | Mouse | Associated with totipotency and zygotic genome activation [24] |

Gastrulation and Germ Layer Formation

Gastrulation is a pivotal event during which the three germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—are established. scRNA-seq applied to in vitro models like gastruloids has provided a detailed view of the transcriptional programs driving this process. A multi-layered proteomics study of mouse gastruloids revealed global rewiring of the (phospho)proteome and distinct protein expression profiles for each germ layer, with key transcription factors like ZEB2 playing a critical role in subsequent somitogenesis [28].

Integration of scRNA-seq data with other modalities is deepening our understanding. For instance, a 2025 study profiling seven histone modifications (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27ac) using TACIT in mouse early embryos revealed that epigenetic heterogeneity, particularly in H3K27ac, emerges as early as the 2-cell stage, priming cells for future lineage choices [29].

Figure 2: A transcriptional roadmap of early lineage specification. Key regulatory genes and processes identified by scRNA-seq are shown at critical developmental transitions from the totipotent zygote to the germ layers. {#fig2}

Experimental Models and Validation

Given ethical and legal restrictions on human embryo research, scientists have developed several in vitro models to study early development.

- Stem Cell-Derived Embryo-like Models: Blastoids (blastocyst-like structures) and gastruloids (models of gastrulation) are derived from pluripotent stem cells. scRNA-seq is essential for validating these models by comparing their transcriptional profiles to their in vivo counterparts, assessing how faithfully they recapitulate natural developmental trajectories [22] [28].

- Extended Pluripotent Stem Cells (EPSC): These are stem cells cultured under specific conditions that purportedly confer a broader developmental potential, including the ability to contribute to both embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages. However, the true totipotent character of some reported EPSC lines has been questioned and requires stringent validation [24].

- 2-Cell-like Cells (2CLCs): As mentioned, this rare cell population within mESC cultures provides a tractable system for studying the molecular underpinnings of the totipotent state [24].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Studies in Early Development {#tbl2}

| Reagent / Resource | Category | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| scVI / scANVI [23] | Computational Tool | Deep learning-based probabilistic modeling for dataset integration and cell type classification. |

| Seurat [27] | Computational Tool | A comprehensive R package for the analysis and visualization of scRNA-seq data. |

| TACIT/CoTACIT [29] | Experimental Method | Enables genome-coverage single-cell profiling of multiple histone modifications, allowing for multi-omics integration. |

| Gastruloids [22] [28] | Biological Model | Stem cell-derived 3D aggregates that model post-implantation development and germ layer formation. |

| 2-Cell-like Cells (2CLCs) [24] | Biological Model | A rare population within mESC cultures used to study the transcriptional and epigenetic features of totipotency. |

| Extended Pluripotent Stem Cells (EPSC) [24] | Biological Model | Stem cells cultured under specific conditions to exhibit expanded developmental potential. |

| NR5A2 siRNA/CRISPR [25] | Perturbation Tool | Used to functionally validate the role of the critical transcription factor NR5A2 in connecting ZGA to lineage specification. |

| ZEB2 degron system [28] | Perturbation Tool | Enables rapid, targeted degradation of the ZEB2 protein to study its essential role in somitogenesis. |

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally altered the resolution at which we can observe the initial stages of life. By delineating the transcriptional cascades from totipotency through germ layer formation, it provides a systematic, data-driven framework for understanding the molecular logic of development. The integration of scRNA-seq with other omics technologies, advanced computational models, and innovative in vitro systems continues to refine this framework. These insights are not only foundational for developmental biology but also pave the way for advances in regenerative medicine and the understanding of developmental disorders.

The maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) represents a cornerstone event in embryonic development, marking the critical handover of developmental control from the maternal genome to the zygotic genome. This process encompasses the degradation of maternally supplied transcripts and the subsequent activation of the zygotic genome, a pivotal phase for successful embryogenesis. While the roles of protein-coding genes have been extensively studied, the emergence of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) as master regulators of MZT has only recently come into focus. These ncRNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), fine-tune gene expression at multiple levels, offering a sophisticated regulatory layer that ensures the precise spatiotemporal coordination required for this developmental milestone. The investigation of these elements is increasingly powered by advanced single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies, which provide the resolution necessary to dissect complex regulatory networks in individual cells during early development.

In plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, MZT occurs relatively late, with the first zygotic division taking place approximately 24 hours after pollination (hap), and zygotic genome activation (ZGA) happening gradually [19]. This stands in contrast to many animal models, where MZT occurs earlier. Recent research has begun to illuminate that despite this timing difference, ncRNAs constitute a sizable and significant portion of the transcriptome and play crucial regulatory roles during MZT across species, from plants to corals and vertebrates [30] [19] [31]. These RNAs form intricate networks, such as the competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network, where different RNA species communicate and co-regulate each other by competing for shared miRNA binding sites [19]. Understanding the dynamics of these networks is essential for a complete molecular understanding of embryonic development.

Key Non-Coding RNA Classes and Their Functions in MZT

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

Long non-coding RNAs are transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding potential. During MZT in Arabidopsis thaliana, researchers have identified over 80 known lncRNAs and 300 novel lncRNAs that are differentially expressed, many of which are specific to particular phases of the MZT [30] [19]. These lncRNAs exert their regulatory functions through diverse mechanisms. They can act as molecular scaffolds that recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, thereby influencing the transcriptional landscape of the zygote. Furthermore, lncRNAs can function as decoys or sponges for miRNAs, sequestering them and preventing them from interacting with their target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). This function is particularly important within the ceRNA network, where the delicate balance between lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs ensures proper gene expression dynamics during the transition from maternal to zygotic control.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNAs, approximately 22 nucleotides in length, that primarily function as post-transcriptional repressors of gene expression. They achieve this by binding to partially complementary sequences in the 3' untranslated regions of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. During MZT, miRNAs are instrumental in the clearance of maternal mRNAs, a necessary step for embryonic patterning and the onset of zygotic programs. Studies in both Arabidopsis thaliana and the reef-building coral Montipora capitata have identified distinct waves of miRNA expression and activity that correspond to key transitions in early development [19] [31]. In Arabidopsis, stage-specific "hub-miRNAs" have been predicted across different zygotic development stages, suggesting they sit at the core of regulatory networks and potentially coordinate the expression of hundreds of transcripts [30] [19].

The ceRNA Network Hypothesis

The competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis presents a unifying framework to understand the interactions between different RNA species. In this model, lncRNAs and other transcripts possessing miRNA binding sites (such as circular RNAs) can act as "sponges," competing with mRNAs for miRNA binding. By sequestering miRNAs, these ceRNAs can derepress the miRNA's natural mRNA targets, adding a complex layer of post-transcriptional regulation. Research in Arabidopsis thaliana has revealed that these ceRNA networks are not static; they undergo dynamic "rewiring" during MZT, with changing interactions among mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs across developmental stages [30] [19]. This differential rewiring is crucial for the progressive changes in gene expression that drive embryonic development.

Quantitative Profiling of Non-Coding RNAs During MZT

Recent transcriptomic studies have provided a quantitative overview of the non-coding RNA landscape during MZT. The following table summarizes key findings from an scRNA-seq analysis of MZT in Arabidopsis thaliana, illustrating the scale of differential expression and the discovery of novel regulatory elements.

Table 1: Summary of Differentially Expressed Elements During MZT in Arabidopsis thaliana

| Element Type | Quantity Identified | Key Characteristics | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed mRNAs | > 1,900 | Stage-specific expression patterns from egg to 1-cell embryo | Represents the core transcriptomic shift from maternal to zygotic control [30] [19]. |

| Known LncRNAs | 80 | Previously annotated; show differential expression during MZT | Suggests important, conserved regulatory roles in early development [30] [19]. |

| Novel LncRNAs | ~ 300 | Newly identified; include MZT phase-specific lncRNAs | Indicates a previously hidden layer of complexity in embryonic regulation [30] [19]. |

| Hub-miRNAs | Predicted across stages | Central nodes in miRNA-mRNA interaction networks | Potential master regulators coordinating the clearance of maternal transcripts and activation of zygotic programs [30] [19]. |

Parallel investigations in other species underscore the conserved nature of ncRNA involvement in MZT. In the coral Montipora capitata, mRNA-miRNA interaction analyses suggest that miRNAs contribute significantly to the degradation of maternal transcripts, particularly those involved in developmental regulation [31]. This highlights the critical and evolutionarily conserved role of miRNAs in orchestrating the timely clearance of maternal messages, a prerequisite for zygotic genome activation.

Advanced scRNA-seq Methodologies for Studying MZT

Metabolic RNA Labeling and scRNA-seq

To capture the dynamic RNA synthesis and degradation events during MZT, scientists employ metabolic RNA labeling coupled with scRNA-seq. This technique involves feeding embryos nucleoside analogs (e.g., 4-Thiouridine (4sU) or 5-Ethynyluridine (5EU)), which are incorporated into newly synthesized RNA. These tagged RNAs can then be distinguished from pre-existing ones through chemical conversion and sequencing, allowing for the precise measurement of transcriptional dynamics in single cells [17].

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated ten different chemical conversion methods for detecting these labeled RNAs. The performance of these methods was assessed based on RNA integrity, conversion efficiency (T-to-C substitution rate), and RNA recovery rate (number of genes and UMIs detected per cell) [17]. The following table summarizes the top-performing methods from this benchmark, providing a guide for experimental design.

Table 2: Benchmarking of Chemical Conversion Methods for Metabolic Labeling scRNA-seq

| Chemical Conversion Method | Key Reagents | Condition | Average T-to-C Substitution Rate | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCPBA/TFEA | meta-chloroperoxy-benzoic acid / 2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine | pH 7.4 (on-beads) | 8.40% | High conversion efficiency [17] |

| mCPBA/TFEA | meta-chloroperoxy-benzoic acid / 2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine | pH 5.2 (on-beads) | 8.11% | High conversion efficiency & minimal impact on library complexity [17] |

| NaIO4/TFEA | Sodium periodate / 2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine | pH 5.2 (on-beads) | 8.19% | High conversion efficiency [17] |

| IAA (Iodoacetamide) | Iodoacetamide | 32°C (on-beads) | 6.39% | Compatible with commercial high-capture-efficiency platforms [17] |

The study concluded that on-beads methods (where chemical conversion occurs after mRNA is captured on barcoded beads) generally outperform in-situ approaches (conversion within intact cells before encapsulation). The mCPBA/TFEA combination was particularly effective [17]. This methodology was successfully applied to zebrafish embryonic cells during MZT, leading to the identification and validation of zygotically activated transcripts.

Computational Clustering for scRNA-seq Data

The analysis of scRNA-seq data from MZT experiments relies heavily on computational methods to identify distinct cell states and transitions. Traditional clustering methods often use "hard" graph constructions, where relationships between cells are binary (connected or not), which can oversimplify the continuous nature of developmental processes [32].

To address this, new methods like scSGC (Soft Graph Clustering) have been developed. scSGC uses non-binary edge weights to capture the continuous similarities between cells more accurately, which is crucial for resolving subtle transitional states during MZT. Its framework integrates a ZINB-based feature autoencoder to handle data sparsity, a dual-channel soft graph module to model cell-cell relationships, and an optimal transport-based clustering optimizer [32]. This approach has been shown to outperform numerous state-of-the-art models in clustering accuracy and cell type annotation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Analysis of MZT

| Category / Item | Specific Example | Function in MZT Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Labeling Reagents | 4-Thiouridine (4sU), 5-Ethynyluridine (5EU) | Labels newly synthesized RNA, enabling measurement of RNA dynamics during zygotic genome activation [17]. |

| Chemical Conversion Kits | mCPBA/TFEA-based kits, IAA-based kits (e.g., SLAM-seq) | Chemically converts labeled RNA for detection via sequencing; critical for time-resolved scRNA-seq [17]. |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Drop-seq, 10x Genomics, MGI C4 | High-throughput platform for capturing transcriptomes of individual embryonic cells [17]. |

| Computational Tools | scSGC clustering pipeline, dynast pipeline | Analyzes scRNA-seq data, identifies cell clusters, and reconstructs developmental trajectories [17] [32]. |

Visualizing Regulatory Networks and Experimental Workflows

The ceRNA Network During MZT

The following diagram illustrates the core competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network, a key regulatory mechanism involving interactions between mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs during MZT.

Core ceRNA Network in MZT: This diagram shows how a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) can act as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) by sequestering a microRNA (miRNA). This competition prevents the miRNA from repressing its target messenger RNA (mRNA), thereby allowing the translation of the zygotic transcript into a functional protein [30] [19].

Metabolic RNA Labeling Workflow

This diagram outlines the key steps of a metabolic RNA labeling experiment (e.g., using scSLAM-seq or scNT-seq) for studying RNA dynamics in MZT.

Metabolic RNA Labeling Workflow for MZT: This workflow begins with pulsing embryos during MZT with a nucleoside analog. Cells are then processed single-cell suspensions, followed by a key chemical conversion step that marks the newly synthesized RNA for sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis finally distinguishes zygotically activated transcripts from maternal RNAs [17].

The integration of advanced scRNA-seq technologies, particularly metabolic labeling, with sophisticated computational clustering methods is ushering in a new era of precision in developmental biology. These tools have firmly established non-coding RNAs—including miRNAs, lncRNAs, and the complex ceRNA networks they form—as critical regulators of the maternal-to-zygotic transition. The dynamic rewiring of these networks ensures the precise temporal control of maternal mRNA degradation and zygotic genome activation, a process conserved from plants to animals. Future research, building on the foundational data and methodologies outlined here, will continue to decode the intricate dialog between the maternal and zygotic genomes, with profound implications for understanding the very beginnings of life and the molecular basis of developmental disorders.

Advanced scRNA-seq Methodologies for Capturing Dynamic MZT Processes

Metabolic RNA labeling techniques represent a groundbreaking advancement in single-cell RNA sequencing, enabling researchers to capture temporal dynamics of RNA synthesis and degradation within individual cells. By integrating nucleoside analogs like 4-thiouridine (4sU) with high-throughput scRNA-seq platforms, methods such as scNT-seq and scSLAM-seq provide unprecedented resolution for monitoring transcriptional kinetics during dynamic biological processes. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodological considerations, and applications of these technologies, with particular emphasis on their transformative potential for elucidating regulatory mechanisms during maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) in embryonic development. We present comprehensive experimental protocols, quantitative benchmarking data, and analytical frameworks to facilitate implementation of these powerful techniques in developmental biology research and drug discovery applications.

Conventional single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) methods provide static snapshots of gene expression patterns, capturing cellular heterogeneity but obscuring the temporal dynamics of RNA regulation [33]. This limitation is particularly significant when studying rapid biological transitions such as the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT), where the transcriptional landscape shifts dramatically as control passes from maternal to zygotic genomes [34] [30]. Metabolic RNA labeling techniques overcome this limitation by incorporating nucleoside analogs into newly synthesized RNA, creating a time-stamp that distinguishes recently transcribed RNA from pre-existing transcripts [33] [35].

The integration of metabolic labeling with scRNA-seq has opened new avenues for investigating RNA kinetics at single-cell resolution, enabling precise measurement of transcription and degradation rates during critical developmental windows [36]. These approaches are revolutionizing our understanding of cellular differentiation, embryonic development, and disease progression by adding a temporal dimension to single-cell analysis [34]. In the context of MZT, these methods provide unique insights into the coordination of RNA synthesis and degradation that underlies this fundamental developmental process [17] [30].

Core Methodologies and Principles

Fundamental Biochemical Principles

Metabolic RNA labeling techniques share a common biochemical foundation centered on the incorporation of nucleoside analogs into newly transcribed RNA:

4-Thiouridine (4sU) Integration: Cells are exposed to 4sU, which is incorporated into nascent RNA during transcription. The concentration and duration of 4sU exposure can be tuned to balance labeling efficiency with cellular toxicity [33] [35].

Chemical Conversion: After RNA extraction, specific chemical treatments convert the incorporated 4sU residues, creating characteristic T-to-C (thymine-to-cytosine) mutations in sequencing reads [33] [17]. This conversion serves as the primary marker for distinguishing newly synthesized RNA.

Sequencing and Bioinformatics: Converted RNAs are sequenced using scRNA-seq platforms, with specialized computational pipelines identifying T-to-C substitutions to quantify newly synthesized versus pre-existing transcripts [33] [35].

The key advantage of this approach is that it enables simultaneous measurement of both new and old RNA populations within the same cell, effectively capturing two timepoints in a single measurement [35]. This dual perspective is particularly valuable for understanding rapid transcriptional changes during developmental transitions like MZT.

Major Technical Platforms

Several specialized methodologies have been developed to integrate metabolic labeling with single-cell transcriptomics:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Metabolic RNA Labeling Techniques

| Method | scRNA-seq Platform | Chemical Conversion Approach | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scNT-Seq [33] | Drop-seq | TFEA/NaIO₄ or mCPBA/TFEA on barcoded beads | High-throughput, UMI-based quantification | Profiling RNA dynamics in heterogeneous cell populations |

| scSLAM-seq [17] | Various platforms | IAA-based reaction (in-situ or on-beads) | Compatibility with different platforms | Cell culture systems, rapid transcriptional responses |

| NASC-seq [35] | Smart-seq2 | Alkylation-based conversion | High sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts | Monitoring rapid transcriptional responses in single cells |

| scDUAL-seq [36] | Multiple platforms | Dual nucleoside analog labeling | Simultaneous measurement of synthesis and degradation | Comprehensive RNA kinetic analysis in heterogeneous populations |

| Well-TEMP-seq [17] | Microwell-based system | Various chemical approaches | High cell capture efficiency | Systems with limited cell numbers (e.g., early embryos) |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for scNT-seq, a representative metabolic RNA labeling method:

Figure 1: scNT-seq Experimental Workflow. Cells are metabolically labeled with 4sU, co-encapsulated with barcoded beads in droplets, followed by on-bead chemical conversion, library preparation, and sequencing with specialized analysis to distinguish newly transcribed RNAs. [33]

Technical Optimization and Benchmarking

Chemical Conversion Methods

The efficiency of metabolic labeling approaches heavily depends on the chemical conversion step, which marks newly synthesized RNA for detection. Recent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated different conversion chemistries:

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Chemical Conversion Methods [17]

| Chemical Method | Average T-to-C Substitution Rate | RNA Recovery Rate | Library Complexity | Recommended Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCPBA/TFEA pH 7.4 | 8.40% | High | Moderate | Standard conditions, high sensitivity required |

| mCPBA/TFEA pH 5.2 | 8.11% | High | High | Optimal balance of efficiency and complexity |

| NaIO₄/TFEA pH 5.2 | 8.19% | High | Moderate | Alternative oxidizing conditions |

| IAA (on-beads, 37°C) | 3.84% | Moderate | Moderate | Commercial platforms with high capture efficiency |

| IAA (on-beads, 32°C) | 6.39% | Moderate | Moderate | Drop-seq compatibility |

| IAA (in-situ) | 2.62% | Lower | Higher | Limited sample availability |

The benchmarking data reveals that mCPBA/TFEA-based methods generally achieve superior T-to-C substitution rates compared to IAA-based approaches [17]. However, the optimal choice depends on specific experimental constraints, including the scRNA-seq platform, sample type, and required sensitivity.

Platform-Specific Considerations

The compatibility of metabolic labeling with different scRNA-seq platforms presents important technical considerations:

On-Beads vs. In-Situ Conversion: Methods like scNT-seq perform chemical conversion on RNA after capture on barcoded beads, achieving approximately 2.32-fold higher substitution rates than in-situ approaches where conversion occurs in intact cells [17].

Capture Efficiency: Commercial platforms like 10x Genomics and MGI C4 offer higher cell capture rates (~50%) compared to home-brew Drop-seq systems (~5%), making them preferable for samples with limited cell numbers, such as early embryonic materials [17].

RNA Integrity: Chemical conversion treatments typically reduce library complexity to some degree, though second-strand synthesis can help recover partially reversed transcribed mRNAs [33].

Application to Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition Research

Technical Advantages for MZT Studies

Metabolic RNA labeling techniques offer particular advantages for investigating the maternal-to-zygotic transition, a critical developmental process characterized by dramatic reprogramming of gene expression:

Distinguishing Maternal and Zygotic Transcripts: By enabling separation of newly synthesized (zygotic) RNA from pre-existing (maternal) RNA, these methods directly address a fundamental challenge in MZT research [17] [30].

Capturing Rapid Transcriptional Changes: The MZT involves precisely timed waves of transcriptional activation and RNA degradation, processes that can be quantitatively measured using metabolic labeling approaches [36].

Single-Cell Heterogeneity: scRNA-seq integration reveals cell-to-cell variation in the timing and extent of zygotic genome activation, which may be crucial for normal development [34].

Experimental Design Considerations

Implementing metabolic labeling for MZT studies requires careful experimental planning:

Labeling Window Optimization: The duration of 4sU exposure must be calibrated to capture transcriptional bursts during zygotic genome activation without excessive cellular stress. Short pulses (15-60 minutes) are often optimal for resolving rapid transitions [35].

Embryo Compatibility: Methods must be adapted for embryonic tissues, with considerations for permeability barriers and minimal perturbation of developmental processes [17].

Reference-Based Demultiplexing: For species-mixing experiments or pooled embryo analysis, pre-labeling with DNA barcodes enables sample multiplexing while avoiding batch effects [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of metabolic RNA labeling requires specific reagents and materials:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic RNA Labeling Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside Analogs | 4-Thiouridine (4sU), 5-Ethynyluridine (5EU), 6-Thioguanosine (6sG) | Incorporates into newly synthesized RNA; concentration and exposure time must be optimized for each biological system [17] [35] |

| Chemical Conversion Reagents | Iodoacetamide (IAA), 2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine (TFEA), meta-chloroperoxy-benzoic acid (mCPBA), sodium periodate (NaIO₄) | Creates base conversions in labeled RNA; choice affects efficiency and RNA integrity [33] [17] |

| scRNA-seq Platform | Drop-seq beads, 10x Genomics, MGI C4, Microwell systems | Platform choice balances capture efficiency, throughput, and compatibility with chemical conversion [17] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | dynast pipeline, GRAND-SLAM, Binomial mixture models | Distinguishes true conversions from background errors; essential for accurate kinetic measurements [17] [35] |

| Sample Multiplexing | ClickTags, Lipid-tagged DNA barcodes, Genetic barcodes | Enables pooling of multiple samples while avoiding batch effects; particularly valuable for embryo time-course studies [34] |

Analytical Framework and Data Interpretation

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The analysis of metabolic labeling data requires specialized computational approaches to accurately distinguish signal from noise:

Base Conversion Detection: Raw sequencing data must be processed to identify T-to-C substitutions while accounting for sequencing errors and natural mutation rates [35].

Statistical Modeling: Binomial mixture models adapted from approaches like GRAND-SLAM estimate the true conversion probability while considering background error rates, significantly improving detection accuracy [35].

Kinetic Parameter Calculation: For methods like scDUAL-seq that incorporate dual labeling, synthesis and degradation rates can be calculated simultaneously, providing comprehensive RNA kinetic profiles [36].

The following diagram illustrates the core analytical workflow for interpreting metabolic labeling data:

Figure 2: Computational Analysis Pipeline. Specialized bioinformatics workflows process base conversion data to distinguish newly synthesized from pre-existing RNAs and calculate kinetic parameters. [33] [35]

Integration with Single-Cell Multi-Omics

Metabolic RNA labeling data can be powerfully integrated with other single-cell omics approaches to provide multidimensional insights into MZT:

Regulatory Network Inference: Tools like SCENIC can identify transcription factor regulons with altered activity based on newly synthesized RNA, revealing direct transcriptional effects rather than secondary consequences [33].

Spatial Context Integration: Combining temporal RNA dynamics with spatial transcriptomics positions transcriptional events within the embryonic architecture [34].

Epigenetic Correlation: Joint analysis with scATAC-seq data can connect chromatin accessibility changes with subsequent transcriptional responses during zygotic genome activation [34].

Metabolic RNA labeling techniques represent a significant advancement in single-cell transcriptomics, providing previously unattainable temporal resolution for studying dynamic biological processes. The application of these methods to maternal-to-zygotic transition research offers particular promise for elucidating the precise timing and regulation of zygotic genome activation, RNA degradation events, and the emergence of transcriptional heterogeneity in early development.

As these technologies continue to evolve, we anticipate further improvements in conversion efficiency, platform compatibility, and computational analysis methods. The integration of metabolic labeling with emerging multi-omics approaches will likely provide increasingly comprehensive views of embryonic development, disease mechanisms, and cellular differentiation processes. For researchers investigating dynamic biological systems, these techniques provide powerful tools to move beyond static snapshots and capture the temporal dimension of gene regulation.