Decoding Positional Information in Embryos: From Morphogen Gradients to Precision Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how cells interpret positional cues to form complex tissues and organs during embryonic development.

Decoding Positional Information in Embryos: From Morphogen Gradients to Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how cells interpret positional cues to form complex tissues and organs during embryonic development. We examine the foundational principles of positional information, from Wolpert's French Flag model to modern information-theoretic approaches. The review covers cutting-edge methodologies, including brain organoid systems and quantitative imaging, used to study and manipulate positional signals. We also address the inherent challenges and noise-filtering mechanisms that ensure patterning robustness and compare the instructed versus self-organizing paradigms across model systems. Finally, we discuss the critical implications of these fundamental processes for understanding birth defects and advancing regenerative medicine strategies.

The French Flag to Molecular Signals: Core Principles of Positional Information

A fundamental question in developmental biology is how a single fertilized egg gives rise to a complex multicellular organism with precisely organized tissues and organs. At the heart of this process lies the problem of how cells determine their spatial position within the embryo and adopt fates appropriate to that location. The conceptual framework for understanding this phenomenon was revolutionized by Lewis Wolpert's introduction of the French Flag model and the accompanying theory of positional information. This model provides a powerful abstraction for how cells decode their position within a developing embryo, proposing that cells acquire positional value through exposure to spatial cues, primarily in the form of morphogen gradients [1] [2]. These values are then interpreted by cells' genetic machinery to drive appropriate differentiation, ensuring the reproducible formation of spatial patterns like the distinct blue, white, and red stripes of the French flag, irrespective of the embryo's absolute size [1]. This whitepaper examines the core principles of Wolpert's paradigm, its mathematical formalization through information theory, the experimental evidence supporting it, and modern computational approaches that expand upon its original concepts, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical guide to this foundational framework in developmental biology.

Core Principles of the French Flag Model

Conceptual Foundations and Historical Context

The French Flag model originated from Lewis Wolpert's seminal work in the late 1960s, framing the challenge of embryonic pattern formation as a "French Flag Problem" [1] [3]. The model abstracts a developing tissue as a one-dimensional array of initially identical cells that must self-organize into three distinct regions (blue, white, and red) representing different cell fates, with the relative proportions of these regions remaining constant even if the overall tissue size varies [3]. Wolpert's key insight was the separation of positional specification—how a cell determines its location—from interpretation—how the cell's genetic program responds to that positional cue to execute a specific differentiation pathway [1]. This framework distinguished itself from lineage-based models by emphasizing that cell fate is determined by environmental positional cues rather than inherited cytoplasmic determinants [1].

The model posits that positional information is provided by a morphogen—a signaling molecule that forms a concentration gradient across the developing tissue [2]. Cells respond to this gradient through discrete concentration thresholds [1]. Specifically:

- High morphogen concentrations (above threshold T1) activate genetic programs for one fate (e.g., blue stripe)

- Intermediate concentrations (between T1 and T2) activate programs for a second fate (e.g., white stripe)

- Low concentrations (below T2) activate programs for a third fate (e.g., red stripe) [1]

This threshold-based interpretation enables a single gradient to generate multiple cell types in a predictable spatial pattern, with boundary sharpness maintained through mechanisms like cooperative binding of transcription factors and positive feedback loops [1].

The Morphogen Gradient Mechanism

In the French Flag model, morphogens are diffusible signaling molecules that establish concentration gradients across developing tissues [1]. The gradient forms through localized production of the morphogen at a specific source, followed by diffusion away from this site and uniform degradation throughout the tissue [1]. This dynamic balance between production, diffusion, and degradation maintains a stable concentration distribution over time, providing reliable positional cues despite ongoing molecular turnover [1]. The steady-state assumption central to the model means that the rate of morphogen production at the source balances the combined effects of diffusion and degradation [1]. Cells then read their position by detecting the local concentration of this morphogen through specific receptors and signal transduction pathways, ultimately leading to concentration-dependent activation of target genes that determine cellular fate [2].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the French Flag model:

Figure 1: The French Flag Model Mechanism. A morphogen gradient establishes positional information that cells interpret through concentration thresholds to determine fate.

Mathematical Formalization: From Gradients to Information Theory

Information-Theoretic Framework for Positional Information

While Wolpert's original formulation was qualitative, recent advances have provided a rigorous mathematical framework for positional information based on Shannon information theory [4] [5]. This approach formalizes the colloquial concept that "a cell determines its position from noisy patterning cues" into a quantifiable metric [5]. The central quantity is mutual information, I(X;Y), which measures the statistical dependence between a cell's position (X) and the molecular cues it detects (Y), such as morphogen concentrations [4] [5].

Mutual information is derived from the more basic concept of entropy, S(X) = -Σ P(X) log₂P(X), which measures the uncertainty or dynamic range of a probability distribution [5]. Mutual information between position X and gene expression Y is defined as I(X;Y) = S(X) + S(Y) - S(X,Y), representing the reduction in uncertainty about a cell's position when its molecular profile is known [4] [5]. This framework generalizes linear correlation coefficients to capture nonlinear dependencies between position and molecular cues, with higher values (in bits) indicating stronger statistical relationships, less noise, and higher predictability [5].

Positional Information and Positional Error

This information-theoretic approach connects positional information directly to positional error—the uncertainty with which a cell can determine its location based on molecular cues [4]. In the context of developmental gene expression patterns, positional information can be quantified by measuring how much information about position is carried by the expression levels of patterning genes [4]. Studies applying this framework to the early Drosophila embryo have demonstrated that the information distributed among just four gap genes is sufficient to determine developmental fates with nearly single-cell resolution [4]. The mutual information approach allows researchers to move beyond indirect measures of patterning precision (e.g., boundary sharpness) to directly quantify the fundamental limits of positional specification systems subject to biophysical constraints like intrinsic noise in gene expression and embryo-to-embryo variability [4].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Formulations in Positional Information Theory

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy | S(X) = -Σ P(X) log₂P(X) | Uncertainty in cell position or gene expression level | Measures the dynamic range of a morphogen concentration distribution [5] |

| Mutual Information | I(X;Y) = S(X) + S(Y) - S(X,Y) | Reduction in uncertainty about position X when molecular cue Y is known | Quantifies how much information about embryonic position is encoded in gap gene expression patterns [4] [5] |

| Positional Error | σ_x² ≈ 1/(I(X;Y) · ln2) | Uncertainty in inferring position from molecular measurements | Estimates the precision of cell fate boundaries in Drosophila embryo patterning [4] |

| Information Capacity | Maximum I(X;Y) under biophysical constraints | Theoretical limit on distinguishable positional values | Determines how many distinct cell fates a morphogen gradient can reliably specify [4] |

Experimental Evidence and Model Validation

Key Experimental Paradigms

The French Flag model has found substantial experimental support across multiple model organisms. The most direct validation comes from the discovery of morphogen molecules that form concentration gradients and instruct cell fates in a concentration-dependent manner. The first identified morphogen was Bicoid in the Drosophila embryo, which forms an anterior-posterior gradient and acts as a transcription factor to regulate downstream target genes [5] [2]. Subsequent research identified numerous other morphogens, including Decapentaplegic (the Drosophila homolog of TGF-β), Hedgehog, Wingless/Wnt, and Fibroblast Growth Factor [2].

Critical experimental evidence supporting the model includes:

- Grafting experiments: Seminal work by Spemann and others demonstrated that cells adopt fates based on their position rather than their origin [5]

- Genetic perturbations: Mutations affecting morphogen production or interpretation cause predictable shifts in patterning boundaries [4] [5]

- Quantitative imaging: Direct visualization of morphogen gradients and their dynamics using fluorescently tagged proteins [4]

Detailed Methodology: Quantifying Positional Information in Drosophila

A comprehensive experimental protocol for quantifying positional information in the Drosophila embryo involves several key stages [4]:

1. Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Collect fixed Drosophila embryos at appropriate developmental stages (e.g., cleavage cycle 14A)

- Perform immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against key patterning proteins (e.g., Bicoid, Hunchback, Krüppel, Giant, Knirps)

- Acquire high-resolution confocal microscopy images of multiple embryos (N ≥ 50 recommended for statistical power)

- Convert fluorescence intensities to relative protein concentrations using appropriate controls and normalization

2. Data Processing and Error Analysis

- Map embryo coordinates to a standardized normalized anterior-posterior (AP) position (0-100%)

- Extract position-dependent mean expression profiles ḡ(x) for each gene

- Calculate position-dependent variance σ_g²(x) across embryos

- Account for experimental noise sources (antibody staining variability, imaging artifacts)

3. Information-Theoretic Analysis

- Compute mutual information I(g;x) between gene expression levels g and position x

- Estimate positional error from mutual information values

- Assess the contribution of individual genes and their combinations to total positional information

This approach has revealed that the Drosophila gap gene system distributes positional information across multiple genes, achieving nearly single-cell resolution despite intrinsic noise constraints [4].

Modern Computational Approaches and Extensions

Marr's Three Levels of Analysis for Developmental Patterning

A modern framework for understanding positional information applies David Marr's three levels of analysis to developmental patterning [6]:

Computational Level (Normative Theories) At this highest level of abstraction, development is framed as an information processing problem that should maximize the reproducibility of body plans despite stochastic fluctuations [6]. Information-theoretic objectives, such as maximizing positional information, formalize the computational problem to be solved [6].

Algorithmic Level This level describes the specific strategies or algorithms that implement the computational theory. Examples include:

- Thresholding of morphogen concentrations [6]

- Temporal integration of signals [6]

- Lateral inhibition for boundary sharpening [6]

- Spatial averaging to reduce noise [6]

Implementation Level This level addresses the physical implementation of algorithms in biological hardware, including:

- Gene regulatory networks that process positional cues [6]

- Reaction-diffusion systems that generate and maintain morphogen gradients [6]

- Mechano-chemical models that incorporate physical forces [6]

Beyond Global Gradients: Local Signaling and Self-Organization

Recent computational work has explored alternative solutions to the French Flag problem that do not require long-range morphogen gradients. These approaches use cellular automata models with local cell-cell communication rules that can generate robust axial patterns through self-organization rather than global instruction [3]. Evolutionary algorithms have identified successful local rules that implement patterning strategies simple enough to potentially be implemented in natural or synthetic biological systems [3].

These local patterning strategies often employ modular building blocks that can be combined to create patterns with different numbers of regions and proportions [3]. They demonstrate remarkable robustness to noise and system growth, addressing key limitations of pure gradient models while maintaining the core concept of positional specification [3].

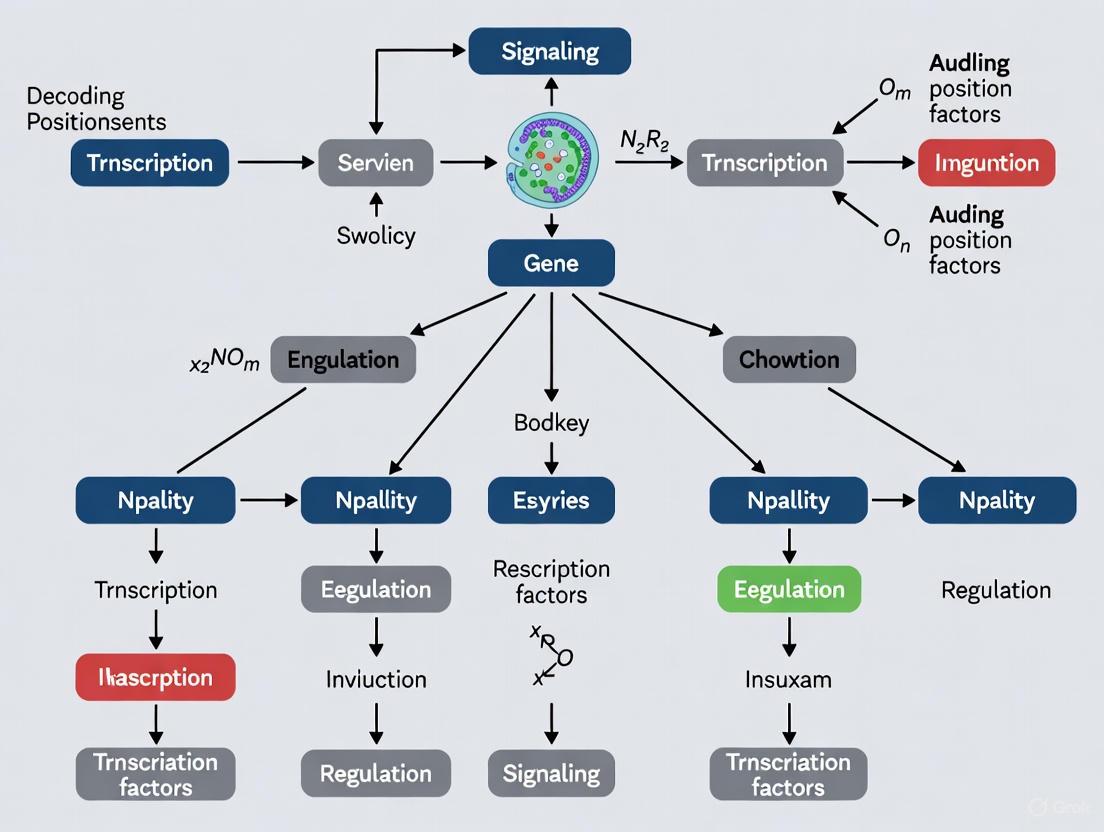

The following diagram illustrates the information flow from positional specification to cell fate determination:

Figure 2: Information Flow in Positional Specification. Position is encoded in morphogen concentrations that are interpreted by gene regulatory networks to determine cell fate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Studying Positional Information

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bicoid Antibodies | Quantify protein concentration gradients in Drosophila | Measure anterior-posterior morphogen gradient formation and dynamics [4] [2] |

| In situ Hybridization | Visualize spatial mRNA patterns for patterning genes | Map expression domains of gap genes and pair-rule genes in early embryos [4] |

| Fluorescent Reporter Genes | Real-time monitoring of gene expression boundaries | Track boundary formation and sharpness in live embryos [4] |

| Cellular Automata Models | Simulate local cell-cell communication strategies | Test self-organizing patterning mechanisms without global gradients [3] |

| Mutual Information Estimation Algorithms | Quantify positional information from expression data | Calculate bits of positional information in gap gene system [4] [5] |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Search parameter spaces for successful patterning rules | Identify local signaling rules that solve French Flag problem [3] |

| Synthetic Morphogen Systems | Engineer orthogonal signaling pathways in synthetic biology | Test principles of gradient formation and interpretation [3] |

Wolpert's French Flag model has provided an enduring conceptual framework for understanding how cells decode their positional information during embryonic development. From its initial formulation as a qualitative model of morphogen gradient interpretation, it has evolved into a quantitative, information-theoretic paradigm that reveals fundamental limits and design principles of developmental systems. The integration of experimental approaches with computational modeling continues to uncover both the universal principles and specific mechanisms that enable reproducible pattern formation in the face of biological noise and variability. For researchers in developmental biology and regenerative medicine, this framework offers powerful tools to dissect patterning processes, engineer synthetic tissues, and understand the failures of positional signaling in disease states. As we deepen our understanding of how positional values are established, interpreted, and maintained, we move closer to the ultimate goal of controlling cell fate and tissue architecture for therapeutic applications.

The development of a complex, multicellular organism from a single fertilized egg is one of the most remarkable processes in biology. A fundamental question in developmental biology is how cells acquire their positional identities to form correctly patterned tissues and organs. The concept of morphogen gradients has emerged as a central answer to this question. Morphogens are signaling molecules that are distributed in a concentration-dependent manner across a developing tissue, providing positional information that instructs cells to adopt specific fates according to their location within the gradient [7]. This whitepaper examines three paradigmatic morphogen systems—Bicoid, Retinoic Acid, and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH)—that function as biochemical coordinates in embryonic patterning, with particular focus on their mechanisms of action, quantitative properties, and experimental methodologies for their study.

The intellectual foundation for understanding morphogen gradients dates back to early experimental embryology, which revealed that developing embryos possess an inherent coordinate system. Seminal work by Spemann and Mangold in 1924 identified the "organizer" region in newt embryos, which could induce a secondary embryonic axis when transplanted, suggesting the presence of inductive, diffusible substances [7]. In 1969, Lewis Wolpert crystallized these concepts into the "French Flag Model," proposing that a diffusible morphogen produced at a source and degraded at a sink could establish a linear concentration gradient, with different threshold concentrations specifying distinct cell fates, analogous to the stripes of the French flag [7]. The subsequent molecular identification of morphogens such as Bicoid, Retinoic Acid, and SHH has validated and refined these theoretical models, revealing a sophisticated interplay of diffusion, transcription, and temporal dynamics in embryonic patterning.

Core Principles of Morphogen Gradient Function

Morphogen gradients operate through a set of conserved principles that enable them to reliably convey positional information. First, they are established through processes involving localized synthesis, diffusion, and clearance [7]. The shape of the gradient—whether exponential or linear—is determined by whether clearance occurs throughout the tissue or is localized to a sink [7]. Second, cells interpret their position by measuring the local concentration of the morphogen, often through the activation of target genes with different binding affinities or response elements, leading to distinct transcriptional outputs [7] [8]. Finally, the temporal dimension of morphogen signaling is critical; the duration of exposure can be as important as the concentration in determining cell fate, a phenomenon observed in systems ranging from the Drosophila embryo to the vertebrate neural tube [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Gradient Properties and Patterning Roles of Key Morphogens

| Morphogen | Primary Developmental Role | Gradient Shape | Formation Mechanism | Key Interpretive Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicoid (Bcd) | Anterior-Posterior Patterning in Drosophila | Exponential [7] | Synthesis-Diffusion-Degradation [9] | Concentration + Duration [8] |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Rostro-Caudal Neural Patterning, Organogenesis | Not Specified in Sources | Local Synthesis (RALDHs) & Degradation (CYP26s) [10] | Concentration-dependent Hox Gene Expression [10] |

| Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) | Dorsoventral Neural Tube, Limb Bud Patterning | Not Specified in Sources | Production in Floor Plate/Notochord, Diffusion [11] | Concentration + Duration [11] |

Bicoid: A Quantitative Model for Anterior-Posterior Patterning

Gradient Establishment and Dynamics

Bicoid (Bcd) is a transcription factor that patterns the anterior-posterior (AP) axis of the early Drosophila embryo. It represents one of the best-characterized morphogen systems, with its gradient formation and function subjected to rigorous quantitative analysis. The Bcd gradient is established via a synthesis-diffusion-degradation (SDD) mechanism [7] [9]. Maternal bicoid mRNA is tightly localized to the anterior pole of the oocyte. Upon fertilization and the onset of translation, Bcd protein diffuses through the syncytial blastoderm, creating an exponential concentration gradient that decreases from anterior to posterior [7]. A key study using a fluorescent protein timer as a protein-age sensor provided direct evidence for the SDD model by revealing a gradient of increasing Bcd protein age from anterior to posterior, consistent with continuous production at the anterior, diffusion, and degradation throughout the embryo [9].

The Bcd gradient is highly dynamic, with nuclear concentrations changing rapidly during the syncytial nuclear division cycles. This dynamic nature necessitates that target genes decode their positional information from a shifting concentration profile. The precision of this decoding is remarkable; the gradient is capable of providing sufficient information to distinguish neighboring cell fates [8].

Temporal Decoding of the Bicoid Signal

A critical insight from recent research is that cells do not simply take a instantaneous "snapshot" of the Bcd concentration. Instead, they temporally integrate the Bcd signal. Using an optogenetic tool to switch off Bcd-dependent transcription with high temporal resolution, researchers demonstrated that the duration of Bcd activity is essential for correct cell fate specification [8].

This work revealed two key principles of temporal decoding. First, Bcd transcriptional activity is dispensable for the first hour after fertilization but is persistently required throughout the remainder of the blastoderm stage. Second, there is a dose-duration coupling: cell fates specified by higher Bcd concentrations (in the most anterior regions) require Bcd input for a longer duration than fates specified by lower concentrations (more posterior regions) [8]. Short interruptions of Bcd activity perturb only the most anterior fates, while prolonged inactivation expands these defects toward the posterior. This differential requirement correlates with the higher reliance of anterior gap genes (like hunchback) on Bcd for their sustained expression.

Diagram Title: Bicoid Gradient Formation and Temporal Decoding

Retinoic Acid: A Versatile Morphogen in Neural and Organ Patterning

Biosynthesis and Signaling Topology

Retinoic Acid (RA), a lipid-soluble derivative of Vitamin A, operates as a crucial morphogen in the patterning of the central nervous system (CNS), limbs, and many organs. Unlike Bcd, which is a protein transcribed from a localized mRNA, RA is a small molecule whose distribution is controlled through a sophisticated network of biosynthesis and degradation. The synthesis of RA occurs via a two-step oxidation process: first, retinol is converted to retinaldehyde by enzymes including RDH10, and then retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH1, 2, 3) catalyzes the irreversible conversion to RA [10]. The catabolism of RA is primarily mediated by enzymes of the CYP26 family (Cyp26a1, b1, c1), which degrade it into inactive metabolites [10].

This synthesis-and-degradation topology allows for precise spatiotemporal control of RA levels. In the developing nervous system, the expression of RALDH2 in the paraxial mesoderm generates a source of RA that patterns the hindbrain and spinal cord along the rostro-caudal axis [11] [10]. The activity of CYP26 enzymes in the anterior region protects the forebrain and midbrain from posteriorizing RA signals, creating a sharp boundary of RA activity.

Genomic and Non-Genomic Mechanisms

RA functions primarily by binding to nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARα, β, γ), which form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXR). The RAR:RXR complex binds to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) in the regulatory regions of target genes [10]. In the absence of RA, this complex associates with co-repressors (N-CoR) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) to repress transcription. Upon RA binding, a conformational change leads to the dismissal of co-repressors and recruitment of co-activators (including CBP/p300), which activate transcription by creating a more accessible chromatin environment [10].

Beyond this canonical genomic action, RA also exhibits rapid, non-genomic effects. It can modulate neuronal firing by reshaping the activity of ion channels and influence cell signaling by liberating factors like pSmad1 from nuclear complexes, thereby affecting processes such as BMP signaling [10]. This dual mode of action allows RA to exert both sustained control over transcriptional programs and rapid modulation of cellular physiology.

Table 2: Molecular Machinery of Retinoic Acid Signaling

| Component Category | Key Molecules | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Enzymes | RDH10, RALDH1/2/3 (ALDH1A1/2/3) | Two-step oxidation of Retinol to active RA [10] |

| Degradation Enzymes | CYP26A1/B1/C1 | Catabolize RA into inactive metabolites [10] |

| Nuclear Receptors | RARα/β/γ, RXRα/β/γ | Ligand-activated transcription factors binding RAREs [10] |

| Co-regulators | N-CoR/SMRT, CBP/p300, CARM1 | Chromatin remodeling for transcriptional repression/activation [10] |

| Cellular Binding Proteins | CRABP1/2 | Facilitate intracellular transport and metabolism of RA [10] |

Sonic Hedgehog (SHH): Mediating Dorsoventral Patterning and Neurogenesis

SHH in Neural Tube Patterning

The Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway is a cornerstone in the dorsoventral (DV) patterning of the neural tube and the specification of neuronal subtypes, including motor neurons (MNs). The primary source of SHH during neural tube patterning is the notochord and the floor plate [11]. SHH acts as a classic morphogen, with varying concentrations specifying distinct progenitor domains along the DV axis. High concentrations of SHH induce the expression of transcription factors characteristic of ventral progenitors (such as Nkx2.2), which give rise to V3 interneurons and motor neurons, while lower concentrations specify more dorsal identities (such as Pax6-expressing progenitors that give rise to motor neurons and other interneuron classes) [11].

The concentration-dependent response is further refined by the duration of SHH exposure. Prolonged signaling is required for the specification of the most ventral cell fates, demonstrating that neural progenitors integrate both the level and the timing of the SHH signal [11] [8]. This temporal integration is facilitated by a genetic feedback circuit involving the Gli transcription factors, which are the ultimate effectors of the SHH pathway.

Interaction with Other Morphogenic Pathways

SHH never acts in isolation; it coordinates with other signaling pathways to achieve precise patterning. A critical interaction occurs with the retinoic acid (RA) pathway during motor neuron formation. RA, produced by RALDH-2 in the paraxial mesoderm, functions as a caudalizing factor, promoting a spinal cord identity. SHH, in contrast, acts as a ventralizing factor. The coordination between these two signals is essential for the correct specification of motor neuron precursors in the ventral spinal cord [11]. Furthermore, SHH interacts with Wnt and BMP pathways, often in an antagonistic manner, to define the full complexity of the neural tube's DV axis [11].

Diagram Title: SHH Patterning in the Neural Tube with Pathway Interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing the understanding of morphogen gradients relies on a sophisticated toolkit of molecular biology, imaging, and genetic techniques. The following table summarizes key reagents and methodologies used in contemporary research on Bicoid, Retinoic Acid, and SHH.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Morphogen Research

| Reagent/Method | Morphogen System | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Optogenetic Constructs (CRY2::mCh::Bcd) | Bicoid | Enables high-temporal-resolution, reversible perturbation of Bcd-dependent transcription in live Drosophila embryos [8]. |

| Fluorescent Timer Tagger | Bicoid | Serves as a protein-age sensor to distinguish new vs. old protein pools, validating the Synthesis-Diffusion-Degradation model [9]. |

| MS2-MCP Live Imaging System | Bicoid | Allows direct visualization and quantification of transcriptional activity (e.g., of hunchback) in real time in living embryos [8]. |

| RALDH & CYP26 Modulators | Retinoic Acid | Pharmacological inhibitors/activators or genetic models to manipulate RA synthesis and degradation, defining RA sources/sinks [10]. |

| RAR-specific Agonists/Antagonists | Retinoic Acid | Tools to dissect the specific functions of RAR receptor subtypes in development and disease [10]. |

| SHH-loaded Beads | Sonic Hedgehog | Used for classic embryological experiments to create ectopic sources of SHH and test its inductive properties [11]. |

| SMO Agonists (e.g., SAG) | Sonic Hedgehog | Small molecules that activate the SHH pathway downstream of PTCH1, used to probe pathway function and in differentiation protocols [11]. |

| hESC Differentiation Protocols | SHH & RA | Defined in vitro systems using RA and SHH to differentiate human embryonic stem cells into motor neurons for disease modeling [11]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optogenetic Perturbation of Bicoid Signaling

This protocol, adapted from [8], allows for precise temporal control of Bicoid-dependent transcription to study the dynamics of morphogen interpretation.

- Fly Lines: Generate transgenic flies expressing the optogenetic construct CRY2::mCh::Bcd under the control of the endogenous bcd promoter in a bcd mutant background. For transcription live imaging, cross with flies containing an MS2 reporter system for a target gene (e.g., hunchback-MS2) and MCP::GFP or MCP::mCh.

- Embryo Collection and Preparation: Collect embryos from appropriately crossed flies aged 0-2 hours on apple juice agar plates. Dechorionate embryos manually or chemically.

- Mounting: Align and mount dechorionated embryos on a glass coverslip under halocarbon oil. Ensure the anterior-posterior axis is identifiable.

- Microscopy and Illumination:

- Use a confocal or two-photon microscope equipped with a temperature-controlled chamber (set to 25°C).

- For control ("Dark") experiments, image embryos using a long-wavelength laser (e.g., 561 nm for mCh) to minimize CRY2 activation.

- For perturbation ("Light") experiments, illuminate the entire embryo with a solid-state 488 nm or 470 nm blue laser to activate CRY2. Illumination regimes can be varied (continuous, pulsed) to test different temporal scenarios.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire time-lapse images of both the morphogen (mCh::Bcd) and the transcriptional reporter (GFP/mCh signal from nascent RNA).

- Quantify the nuclear fluorescence intensity of Bcd over time to monitor gradient stability.

- Quantify transcriptional activity by measuring the number of active transcription sites, their intensity, and their persistence (duration of active transcription at a given locus).

Protocol: SHH and RA-Mediated Motor Neuron Differentiation from hESCs

This protocol, based on [11], outlines the key steps to differentiate human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into motor neurons, recapitulating the in vivo interplay of caudalizing (RA) and ventralizing (SHH) morphogens.

- Neural Induction: Culture hESCs in standard maintenance media until they reach 80-90% confluency. To initiate neural induction, switch to a neural basal medium supplemented with dual SMAD signaling inhibitors (e.g., SB431542 for TGF-β/Activin/Nodal inhibition and LDN-193189 for BMP inhibition) for 7-10 days. This step promotes the formation of neural progenitor cells.

- Caudalization with Retinoic Acid: After neural induction, add all-trans Retinoic Acid (RA) to the medium at a concentration of 0.1-1 µM. This step patterns the neural progenitors toward a spinal cord identity. Treat for 5-7 days.

- Ventralization with SHH Agonist: Concurrently with or immediately after RA treatment, add a Sonic Hedgehog pathway agonist to the medium. This can be recombinant SHH protein (e.g., 100-500 ng/mL) or a small molecule SMO agonist like SAG (e.g., 1 µM). This combination of RA and SHH signaling specifies the progenitors to a motor neuron fate (pMN domain).

- Terminal Differentiation: Replace the patterning media with a terminal differentiation medium containing neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF, CNTF) and reduce or withdraw mitogens. Maintain cells in this medium for 1-2 weeks to allow for the maturation and outgrowth of motor neurons.

- Validation: Analyze the resulting cells using immunocytochemistry for motor neuron markers (e.g., Islet1/2, HB9, ChAT) and/or electrophysiology to confirm functional maturity.

The study of morphogen gradients like Bicoid, Retinoic Acid, and Sonic Hedgehog has profoundly advanced our understanding of how biochemical coordinates guide embryonic development. The field has moved from descriptive models to a quantitative and dynamic view of gradient formation and interpretation. Key future directions include:

- Integrating Multi-Scale Data: Combining quantitative measurements of gradient dynamics, live imaging of transcriptional outputs, and single-cell omics will be essential to build predictive, mathematical models of patterning networks.

- Elucidating Non-Canonical Functions: Further investigation into the non-transcriptional roles of morphogens, such as RA's effect on ion channels [10], will provide a more holistic view of their mechanisms.

- Decoding Regulatory Topology: Understanding how the regulatory DNA of target genes integrates information from multiple morphogen pathways (e.g., the convergence of SHH and RA on motor neuron genes) remains a central challenge, now addressable with CRISPR-based screens and live imaging of enhancer activity [12].

- Translating to Disease and Therapy: The critical roles of these pathways in development are mirrored in disease. SHH is implicated in neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and Parkinson's [11], while RA is a successful therapeutic in leukemia but has a complex role in the tumor microenvironment [10]. A deeper mechanistic understanding of morphogen signaling will continue to inform novel therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine and oncology.

In conclusion, Bicoid, Retinoic Acid, and Sonic Hedgehog exemplify the elegant economy of nature, where a handful of signaling molecules, through variations in their concentration, duration, and combinatorial interactions, orchestrate the breathtaking complexity of embryonic patterning. The continued dissection of their actions promises not only to answer fundamental questions in developmental biology but also to provide new avenues for clinical intervention.

The formation of the neural tube is a cornerstone of embryonic development, giving rise to the entire central nervous system. This process is orchestrated by a complex interplay of key signaling morphogens, primarily Wnt, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH). These pathways function as graded cues to provide positional information to neural progenitor cells, determining their fate along the dorsal-ventral (DV) and anterior-posterior (AP) axes. This whitepaper delves into the molecular mechanisms of each pathway, their integration in spatial patterning, and the experimental methodologies used to decipher how cells decode this positional information. Understanding these systems is critical for advancing research in neurodevelopmental disorders and regenerative medicine.

A fundamental question in developmental biology is how a seemingly uniform sheet of cells self-organizes into the complex, patterned tissues of a mature organism. The neural tube, the embryonic precursor to the brain and spinal cord, serves as a powerful model for studying this process. Its patterning along the DV and AP axes is directed by a handful of highly conserved signaling systems, including Wnt, BMP, and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH). These morphogens form concentration gradients across the developing tissue, and progenitor cells interpret their relative levels and timing of exposure to acquire specific identities [11]. This positional information is subsequently translated into the expression of unique transcription factor codes that dictate whether a cell becomes a motor neuron, an interneuron, or another specific neuronal subtype. The precise interpretation of these signals is not only vital for normal development but also provides a framework for in vitro differentiation of human stem cells for disease modeling and therapeutic discovery.

Wnt Signaling in Neural Tube Patterning

Molecular Mechanisms

The Wnt signaling pathway is a critical regulator of diverse cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and migration [13]. It is broadly categorized into the canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) branches.

- Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: In the absence of a Wnt ligand, cytoplasmic β-catenin is constantly targeted for proteasomal degradation by a multiprotein "destruction complex" that includes Axin, Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC), Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β (GSK3β), and Casein Kinase 1α (CK1α) [13]. When a Wnt ligand binds to a Frizzled (Fzd) receptor and its co-receptor (LRP5/6), it recruits Disheveled (Dvl), which disrupts the destruction complex. This leads to the stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin, which then translocates to the nucleus. There, it partners with T-cell factor/Lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factors to activate the expression of target genes such as Axin2 and c-Myc [13].

- Non-canonical Wnt Pathways: The non-canonical branch, including the Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) and Wnt/Ca²⁺ pathways, functions independently of β-catenin. The PCP pathway, activated by ligands like Wnt5a and Wnt11, regulates cytoskeletal organization and cell polarity through Rho and Rac GTPases [13]. The Wnt/Ca²⁺ pathway, also triggered by Wnt5a, modulates intracellular calcium levels, influencing cell adhesion and movement [13].

Role in Neural Tube Patterning

In the context of neural tube patterning, Wnt signaling exhibits a distinct dorsalizing function. The pathway is highly active in the dorsal neural tube, where it is secreted from the roof plate [11]. A high concentration of Wnt, in conjunction with BMP signaling, is a key determinant for the differentiation of dorsal interneurons [11]. Furthermore, Wnt signaling interacts with other morphogen pathways, such as SHH, to establish the precise boundaries of progenitor domains. Wnt signaling also plays a crucial role in the rostral-caudal patterning of the spinal cord, working in concert with Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) to promote caudal (posterior) identities [11].

Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Signaling in Neural Tube Patterning

Molecular Mechanisms

The SHH pathway is a master regulator of ventral patterning. The pathway is initiated when the SHH ligand binds to its receptor, Patched-1 (PTCH1). In the absence of SHH, PTCH1 constitutively inhibits the activity of Smoothened (SMO), a G-protein-coupled receptor-like protein. Binding of SHH to PTCH1 relieves this inhibition, allowing SMO to accumulate and transduce the signal intracellularly [14] [11]. This ultimately leads to the activation of the GLI family of transcription factors (GLI1, GLI2), which move to the nucleus to activate or repress target genes, including PTCH1 and GLI1 themselves, creating a feedback loop [11].

Role in Neural Tube Patterning and Motor Neuron Specification

SHH is secreted from the notochord and the floor plate, creating a ventral-to-dorsal concentration gradient within the neural tube [11]. This gradient is the primary determinant of ventral progenitor cell fates. Different concentrations and durations of SHH exposure activate distinct transcriptional programs in neural progenitor cells. For instance, high levels of SHH are required for the specification of floor plate cells and V3 interneurons, while intermediate levels promote the generation of motor neurons (MNs) [11]. Lower levels are sufficient for the specification of more dorsal V2 and V1 interneurons. The critical role of SHH in MN formation is leveraged in vitro to differentiate human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into MNs by using SHH as a ventralizing factor, often in combination with retinoic acid (RA) for caudalization [11].

Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Signaling in Neural Tube Patterning

Molecular Mechanisms and Role in Patterning

BMPs belong to the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily. The BMP pathway is activated when BMP ligands (e.g., BMP4, BMP7) bind to a receptor complex comprising type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors. This binding leads to the phosphorylation of receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads: Smad1/5/8), which then form a complex with the common mediator Smad4. This complex translocates to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes [11]. BMP signaling is the principal dorsalizing signal in the neural tube. Secreted from the overlying ectoderm and the roof plate, BMPs establish a dorsal-to-ventral gradient that opposes the ventral SHH gradient [11]. High levels of BMP signaling are essential for the induction and patterning of dorsal cell types, including neural crest cells and dorsal interneurons. The inhibition of BMP signaling is, in fact, one of the initial steps required for neural induction from the ectoderm, often mediated by secreted inhibitors like Noggin, Chordin, and Follistatin [11].

Integration of Signaling Pathways and Quantitative Patterning

The precise patterning of the neural tube is not the result of each pathway acting in isolation, but rather from their intricate integration and mutual antagonism. The opposing gradients of ventral SHH and dorsal BMP/Wnt create a coordinate system that allows progenitor cells to ascertain their precise positional identity.

- SHH and Wnt Interaction: Wnt and SHH often act together in processes such as cell differentiation and growth, but their interaction can be either cooperative or antagonistic [11]. In the neural tube, high Wnt activity dorsally and high SHH activity ventrally help to define the boundaries of progenitor domains.

- SHH and RA Interaction: Retinoic acid (RA), a key caudalizing factor, interacts with SHH to regulate the development of the CNS. Studies show that RA can enhance the expression of SHH target genes, and the coordination between these two pathways is necessary for the normal growth and differentiation of motor neuron precursors [11].

Table 1: Summary of Key Signaling Pathways in Neural Tube Patterning

| Signaling Pathway | Source | Gradient | Primary Function in Neural Tube | Key Target Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) | Notochord, Floor plate | Ventral -> Dorsal | Ventral patterning | Floor plate, Motor neurons, V3-V0 interneurons |

| Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) | Ectoderm, Roof plate | Dorsal -> Ventral | Dorsal patterning | Neural crest, Dorsal interneurons |

| Wnt | Roof plate | Dorsal -> Ventral | Dorsal patterning, AP patterning | Dorsal interneurons |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Paraxial mesoderm | Posterior -> Anterior | Caudalization | Spinal cord neurons |

Table 2: Key Transcription Factors and Progenitor Domains

| Progenitor Domain | Position | Key Transcription Factors | Neuronal Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Floor Plate | Most ventral | Foxa2, Shh | N/A (signaling center) |

| pMN | Ventral | Olig2, Nkx6.1 | Motor neurons |

| p3 | Ventral | Nkx2.2 | V3 interneurons |

| p2 | Intermediate | Irx3, Pax6 | V2 interneurons |

| p1 | Intermediate | Pax6, Dbx1 | V1 interneurons |

| p0 | Dorsal | Pax7, Dbx1 | V0 interneurons |

| dP6-dP1 | Dorsal | Pax3, Pax7, Msx1/2 | Dorsal interneurons |

| Neural Crest | Most dorsal | Sox9, Snail1, FoxD3 | Neural crest cells |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

In Vivo Transgenic Mouse Models

Classic experiments elucidating the role of SHH in vivo involved the creation of transgenic mouse models. One methodology adapted the GAL4/UAS system from Drosophila to achieve ectopic expression of full-length SHH in the dorsal neural tube [14].

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Constructs:

- Driver Transgene (pWEXP-GAL4): The coding sequence of the yeast transcription factor GAL4 was cloned into a Wnt-1 expression vector (pWEXP-2). The Wnt-1 promoter drives GAL4 expression in specific regions of the neural tube [14].

- Responder Transgene (pUAS-Shh): The full-length mouse Shh cDNA was cloned downstream of a pentamer array of the Upstream Activating Sequence (UAS), the binding site for GAL4 [14].

- Production of Transgenic Mice: Both linearized transgenes were microinjected into the pronuclei of B6CBAF1/J zygotes. Founder (G0) transgenic mice were identified by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA using probes for GAL4 or Shh [14].

- Experimental Workflow: Bigenic embryos were generated by crossing mice carrying the WEXP-GAL4 driver with mice carrying the UAS-Shh responder. In these embryos, GAL4 is expressed in the Wnt-1 domain and then binds to the UAS to induce Shh expression in the same spatial pattern, effectively misexpressing Shh in the dorsal neural tube [14].

- Analysis: Embryos were harvested between 9.5 and 18.5 days post-coitum (dpc). Proliferation was assessed by phosphohistone-H3 immunostaining. Cellular differentiation was analyzed by in situ hybridization for marker genes and histological examination [14].

Key Findings: This study demonstrated that ectopic SHH signaling in the dorsal neural tube caused a significant increase in proliferative rates at 12.5 dpc. Furthermore, it led to a blockade in differentiation, resulting in persistent structures resembling the ventricular zone germinal matrix at late fetal stages (18.5 dpc) [14]. This provided direct evidence that SHH can promote proliferation and inhibit differentiation in CNS precursors in vivo.

In Vitro Differentiation of Human Stem Cells

To study human neural development and model diseases, protocols have been established to differentiate hESCs into specific neuronal subtypes, such as motor neurons.

Detailed Protocol:

- Neural Induction: hESCs are aggregated into embryoid bodies or plated in specific media to initiate neural induction. This step often involves dual-SMAD inhibition (using inhibitors for BMP and TGF-β pathways) to efficiently direct cells toward a neural lineage [11].

- Caudalization: The neuralized cells are treated with Retinoic Acid (RA), typically at a concentration of 0.1-1 µM, to caudalize the tissue and confer a spinal cord identity [11].

- Ventralization: Concurrently or sequentially, cells are treated with a SHH pathway agonist, such as recombinant SHH protein or the small molecule agonist Purmorphamine (e.g., 0.5-1 µM). This mimics the ventralizing signal from the notochord and specifies the cells to a motor neuron progenitor fate [11].

- Terminal Differentiation: After 2-3 weeks of patterning, the cells are transitioned to a differentiation medium containing neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF, CNTF) to support the maturation and survival of post-mitotic motor neurons.

- Validation: The resulting MNs are validated by immunocytochemistry for markers like HB9, Islet-1, and ChAT, and by functional assays such as patch-clamp electrophysiology to confirm their electrical excitability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Neural Patterning

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SHH | Protein | Agonist of SHH pathway; ventralizing factor | In vitro differentiation of hESCs into motor neurons [11] |

| Purmorphamine | Small Molecule | Smoothened agonist (activates SHH pathway) | Cost-effective alternative to recombinant SHH in cell culture |

| Cyclopamine | Small Molecule | Smoothened antagonist (inhibits SHH pathway) | Studying consequences of loss of SHH signaling |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Small Molecule | Caudalizing factor | Specifying spinal cord identity in stem cell differentiation [11] |

| Noggin / Dorsomorphin | Protein / Small Molecule | BMP pathway inhibitors | Neural induction from pluripotent stem cells; studying dorsal patterning [11] |

| CHIR99021 | Small Molecule | GSK3β inhibitor (activates Wnt/β-catenin) | Studying the role of canonical Wnt signaling in dorsal patterning |

| Transgenic Mouse Models | Animal Model | Tissue-specific gene overexpression/knockout | In vivo analysis of gene function (e.g., dorsal misexpression of Shh) [14] |

| Anti-Olig2 / Nkx2.2 / Pax6 / Pax7 | Antibody | Immunostaining for progenitor domain markers | Identifying and quantifying neural progenitor populations in tissue/cells |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core components and interactions of the Wnt and SHH signaling pathways, which are central to neural tube patterning.

The development of a complex multicellular organism from a single fertilized egg is one of the most remarkable processes in biology. How do cells with identical genetic material acquire distinct identities based on their position within an embryo? For half a century, the dominant conceptual framework for addressing this question has been Lewis Wolpert's theory of positional information [5]. Wolpert elegantly postulated that cells determine their fate by interpreting local concentrations of signaling molecules called morphogens, which form concentration gradients across developing tissues. This "French Flag Model" proposed that cells respond to threshold concentrations of these morphogens to activate specific genetic programs appropriate for their location [5].

While this qualitative framework has been enormously successful in shaping developmental biology, a quantitative revolution has emerged from an unexpected source: information theory. Originally developed by Claude Shannon for communication systems, information theory provides rigorous mathematical tools for quantifying how much information signals can carry about their sources [5]. In the context of development, this means treating position as a random variable and morphogen concentrations as signals about that variable, enabling researchers to quantify precisely how much positional information molecular concentrations encode [4].

This technical guide explores how the fusion of developmental biology with information theory has transformed our understanding of embryonic patterning, focusing on quantitative frameworks, experimental methodologies, and the fundamental limits of positional specification systems.

Theoretical Foundations: Quantifying Positional Information

Core Mathematical Framework

At the heart of the information-theoretic approach to positional information lies mutual information—a measure that captures the statistical dependence between two variables. In developmental systems, we are interested in the mutual information between a cell's position ( x ) and the molecular concentrations ( \vec{g} ) that the cell measures [4]:

[ I(\vec{g}; x) = S(x) - S(x|\vec{g}) ]

Where ( S(x) ) is the entropy of the position distribution (measuring the initial uncertainty about position), and ( S(x|\vec{g}) ) is the conditional entropy (measuring the uncertainty about position that remains after measuring molecular concentrations ( \vec{g} )) [4].

For a one-dimensional embryo of length ( L ) with uniform cell density, the entropy of the position distribution is ( S(x) = \log2 L ). If positional estimates have Gaussian noise with standard deviation ( \sigmax ), the positional information can be approximated as [15]:

[ I{\text{position}} = \log2 L - \log2 (\sqrt{2\pi e} \sigmax) ]

This relationship reveals that positional information increases as the precision of positional specification improves (i.e., as ( \sigma_x ) decreases).

Table 1: Key Information-Theoretic Quantities in Developmental Patterning

| Quantity | Mathematical Expression | Biological Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positional Information | ( I(\vec{g}; x) ) | Amount of information molecular concentrations ( \vec{g} ) carry about position ( x ) | |

| Positional Error | ( \sigma_x ) | Standard deviation of position estimate given molecular concentrations | |

| Entropy of Position | ( S(x) = -\sum P(x)\log_2 P(x) ) | Uncertainty about cell position before molecular measurements | |

| Conditional Entropy | ( S(x | \vec{g}) ) | Uncertainty about position remaining after molecular measurements |

| Mutual Information | ( I(\vec{g}; x) = S(x) - S(x | \vec{g}) ) | Reduction in positional uncertainty due to molecular measurements |

The French Flag Problem Revisited

Wolpert's classic French Flag problem illustrates how positional information enables patterning [5]. In this model:

- A morphogen gradient provides positional information along the anterior-posterior axis

- Cells interpret local morphogen concentrations through intracellular thresholds

- Different concentration thresholds activate distinct genetic programs (flag colors)

- The system transforms continuous positional information into discrete cell fates

The information-theoretic framework quantifies how much information this morphogen gradient contains about position and how reliably cells can interpret this information despite biological noise.

Model System: Quantitative Patterning in the Drosophila Embryo

The Drosophila Patterning Hierarchy

The early Drosophila embryo represents a paradigm for quantitative studies of positional information, with a relatively simple and well-characterized patterning hierarchy [4]:

- Maternal gradients (Bicoid, Caudal) establish initial anterior-posterior polarity

- Gap genes (Hunchback, Krüppel, Giant, Knirps) are expressed in broad domains

- Pair-rule genes (Even-skipped, Fushi tarazu) form seven-stripe patterns

- Segment polarity genes define final segment boundaries

This hierarchy progressively refines positional information, ultimately specifying approximately 100 distinct cell fates along the anterior-posterior axis [15].

Diagram 1: Drosophila patterning hierarchy information flow

Quantifying Positional Information in Gap Genes

Groundbreaking work has quantified positional information in the gap gene system through precise measurements of protein concentrations in hundreds of embryos [4]. The experimental approach involves:

- Quantitative immunofluorescence to measure gap protein concentrations

- Embryo registration to align positions across multiple embryos

- Noise characterization to separate biological variability from measurement error

- Information estimation using computational frameworks

These studies reveal that the combined expression levels of just four gap genes provide sufficient information to specify position with approximately 1% accuracy along the embryo length [15]. This precision approaches the physical limits set by the spacing between nuclei.

Table 2: Quantitative Measurements of Positional Information in Drosophila

| Patterning Layer | Positional Error | Positional Information | Distinguishable States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Gradients | ~2-3% embryo length | ~5.5 bits | ~45 positions |

| Gap Gene System | ~1% embryo length | ~6.5 bits | ~90 positions |

| Pair-Rule Stripes | ~1% embryo length | ~6.5 bits | ~90 positions |

| Theoretical Maximum | ~0.5% embryo length | ~7.5 bits | ~180 positions |

The Information Gap and Spatial Correlations

A fascinating puzzle emerged when researchers discovered that the measured positional information in gap genes appears slightly insufficient to specify unique identities for all cells in the Drosophila embryo [15]. With approximately 90 nuclei along the anterior-posterior axis and positional errors of about 1%, there remains an "information gap" of approximately 1.68 bits [15].

This apparent paradox was resolved by considering spatial correlations in positional errors. When errors are independent between cells, the probability of neighboring cells receiving "crossed signals" (incorrect ordering) is substantial (~20%). However, when positional errors are correlated over distances of approximately 20% of the embryo length, the effective information increases sufficiently to specify unique cellular identities [15].

The mathematical explanation involves the determinant of the correlation matrix ( C ) with elements ( C{nm} = \langle \delta xn \delta xm \rangle / \sigmax^2 ). For correlated errors, the noise entropy is reduced by ( \Delta S = -\frac{1}{2} \log_2 \det C ) bits, increasing the effective positional information [15].

Experimental Protocols: Measuring Positional Information

Quantitative Imaging and Data Processing

Accurate measurement of positional information requires precise quantification of gene expression patterns across multiple embryos [4]:

Sample Preparation:

- Fixation of Drosophila embryos at specific developmental stages

- Immunofluorescence staining for gap proteins (Hb, Kr, Gt, Kni)

- Nuclear staining (DAPI) for position reference

- Mounting in photobleaching-resistant medium

Image Acquisition:

- High-resolution confocal microscopy

- Multi-channel imaging for different gap proteins

- Multiple embryo imaging in single sessions

- Signal calibration using reference standards

Data Processing Pipeline:

- Nuclear segmentation to identify individual nuclei

- Background subtraction and signal normalization

- Embryo registration using landmark features

- Expression quantification for each nucleus

- Cross-embryo alignment to account for variability

Information Estimation from Experimental Data

Estimating mutual information from finite experimental samples requires careful statistical approaches [4]:

Direct Estimation Method:

- Bin position and expression levels into discrete intervals

- Compute empirical probability distributions ( P(g,x) )

- Calculate mutual information using: ( I(g;x) = \sum{g,x} P(g,x) \log2 \frac{P(g,x)}{P(g)P(x)} )

- Apply correction for finite-sample bias

Gaussian Approximation Approach:

- Assume Gaussian distributions for expression patterns

- Estimate position-dependent means ( \bar{g}(x) ) and variances ( \sigma_g^2(x) )

- Compute noise covariance matrix ( \Sigma(x) )

- Calculate information using Gaussian mutual information formula

Binning-Free Methods:

- k-nearest neighbor approaches for continuous estimation

- Kernel density estimation for probability distributions

- Cross-validation to avoid overfitting

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for positional information quantification

Comparative Systems: Positional Information Across Species

Axolotl Limb Regeneration

The molecular basis of positional memory is strikingly revealed in axolotl limb regeneration [16]. Unlike Drosophila embryonic patterning, where positional information is established de novo, regeneration requires cells to retain memory of their original positions.

Key Findings in Axolotl System:

- Posterior identity is maintained by a positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh

- Hand2 expression persists in posterior cells from development through adulthood

- Positional memory can be reprogrammed: anterior cells exposed to Shh during regeneration can stably adopt posterior identity

- Asymmetric reprogramming: anterior-to-posterior conversion is easier than posterior-to-anterior

This system demonstrates how positional information can be maintained long-term through transcriptional feedback loops and potentially epigenetically stabilized gene expression patterns [16].

Microtubule Aster Positioning in Drosophila

Positional information operates not only at the genetic level but also in structural cellular elements. In the syncytial Drosophila embryo, microtubule asters position nuclei through a combination of pushing forces and spatial constraints [17].

Mechanisms of Aster Positioning:

- Aster-boundary interactions push asters toward the center

- Aster-aster repulsion maintains regular spacing

- Effective exclusion zones created by yolk and lipid droplets

- Force balance determines final positions

This physical positioning system works alongside the genetic patterning hierarchy to ensure proper nuclear distribution before cellularization [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Positional Information Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Immunofluorescence | Precise protein concentration measurement | Gap gene expression quantification in Drosophila [4] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Live imaging of gene expression | ZRS>TFP for Shh expression in axolotl [16] |

| Cross-Entropy Test | Statistical comparison of single-cell patterns | Quantifying differences in t-SNE/UMAP projections [18] |

| Lineage Tracing | Tracking cell fate decisions | Genetic fate mapping with Cre-lox systems [16] |

| Microtubule Drugs | Perturbing cytoskeletal positioning | Testing aster positioning mechanisms [17] |

| Shh Pathway Modulators | Manipulating limb patterning | Altering positional memory in axolotl [16] |

| Mutant Drosophila Strains | Uncoupling developmental processes | gnu mutant for aster studies [17] |

Future Directions and Applications

Technological Advances

The field of positional information quantification continues to advance through technological innovations:

Single-Cell Omics:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing for comprehensive transcriptional profiling

- Spatial transcriptomics for positional mapping of gene expression

- Live-cell imaging of transcriptional dynamics

- CRISPR-based lineage tracing

Quantitative Modeling:

- Incorporating chromatin accessibility data

- Modeling epigenetic contributions to positional memory

- Physical models of morphogen transport and signaling

- Whole-embryo digital twins for in silico experiments

Therapeutic Applications

Understanding positional information has profound implications for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering:

Regenerative Medicine:

- Reprogramming positional memory for improved regeneration

- Designing scaffolds with appropriate positional cues

- Directing stem cell differentiation in spatially appropriate patterns

Tissue Engineering:

- Creating organoids with proper positional organization

- Designing synthetic morphogen gradients

- Controlling tissue patterning for artificial organs

Cancer Biology:

- Understanding how positional information is disrupted in cancer

- Exploiting positional signaling pathways for targeted therapies

- Developing drugs that modulate spatial organization

The integration of information theory with developmental biology has transformed our understanding of how embryos encode and process positional information. What began as Wolpert's qualitative French Flag model has evolved into a rigorous quantitative framework capable of measuring the precise information content of biological patterning systems. The demonstration that just four genes in the Drosophila gap gene system can provide nearly sufficient information to uniquely specify all cell identities along the anterior-posterior axis—and that spatially correlated errors can bridge the small remaining information gap—represents a triumph of this quantitative approach [15].

As measurement technologies continue to improve and computational models become more sophisticated, we are moving toward a complete information-theoretic description of embryonic patterning. This framework not only deepens our fundamental understanding of development but also provides essential principles for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. The precise quantification of how cells know where they are—and what they should become—represents one of the most exciting frontiers at the intersection of physics, information theory, and developmental biology.

From In Vivo Studies to Organoids: Tools for Mapping and Manipulating Positional Cues

A fundamental question in developmental biology is how cells within a developing embryo decode their positional information to adopt specific fates and form complex, functional tissues. This process relies on the precise interpretation of molecular signals, which convey location within a coordinate system, ultimately directing the spatial organization of the body plan. The concept of positional information is central to understanding how cells with identical genetic material determine their location in a multicellular structure and consequently their developmental fates [4]. Despite its widespread use as a qualitative descriptor, positional information has only recently been rigorously defined mathematically using information-theoretic principles that quantify how much a cell can learn about its position by measuring local concentrations of various morphogens [4]. Research utilizing established model organisms—particularly Drosophila, zebrafish, and chick—has been pioneering in unraveling the mechanisms of this positional decoding, each system offering unique advantages for probing different aspects of this universal problem. These organisms provide complementary windows into the continuum of developmental strategies, from highly instructed patterning driven by maternal morphogen gradients to self-organized patterning emerging from cellular interactions [6]. This whitepaper synthesizes how studies in these three model systems have illuminated the principles, mechanisms, and quantitative constraints governing how cells interpret positional cues during embryogenesis, providing researchers with technical insights and methodologies applicable to both basic science and drug development.

Theoretical Frameworks for Analyzing Positional Information

The study of positional information has been greatly advanced by formal theoretical frameworks that provide quantitative tools for analyzing developmental patterning. A key approach conceptualizes developmental systems as information processing systems that can be analyzed at what are known as Marr's three levels: the computational problem being solved, the algorithms employed, and their physical implementation [6]. At the first level, the computational problem is often formalized as the need to generate reproducible cell fate patterns despite stochastic fluctuations at cellular and subcellular scales. Information-theoretic measures, particularly mutual information, provide a normative framework for quantifying the spatial precision of cell fate patterns, known as positional information [6]. This approach measures, in bits, the information that gene expression levels provide about cell position and sets fundamental limits on the precision of cell fate decisions [4] [6].

At the algorithmic level, developmental systems implement various signal processing strategies, including thresholding, temporal integration, spatial averaging, and lateral inhibition [6]. These algorithms are formalized mathematically using dynamical systems theory and implemented at the molecular level through gene regulatory networks, reaction-diffusion mechanisms, and specialized cellular structures like cytonemes [6]. This multi-level perspective allows researchers to connect molecular mechanisms with their functional consequences in patterning, providing a unified framework for comparing patterning strategies across different model organisms.

Drosophila melanogaster: Decoding Morphogen Gradients

The Paradigm of Instructed Patterning

The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, represents a quintessential system for studying instructed patterning, where external signals precisely specify cell fates. The early Drosophila embryo exhibits a hierarchical patterning system along its anterior-posterior axis consisting of three layers: long-range maternal protein gradients, gap genes expressed in broad bands, and pair-rule genes expressed in a seven-striped pattern [4]. Positional information is provided primarily through the first layer, established from maternally supplied and highly localized mRNAs that act as protein sources for morphogen gradients such as Bicoid [4]. This system achieves remarkable precision, specifying developmental fates with nearly single-cell resolution using only a handful of genes despite intrinsic biochemical noise and embryo-to-embryo variability [4].

Key Technological Advances

Live imaging of transcription dynamics has revolutionized our understanding of Drosophila patterning. The MS2/MCP system, a groundbreaking RNA-labeling technology, involves expressing a GFP-tagged MS2 coat protein (MCP) alongside a target gene engineered to contain repeats of the MS2 RNA stem-loop sequence in its 3'UTR [19]. This enables real-time visualization of transcription by marking the site of nascent RNA production with fluorescent puncta. This approach revealed that the hunchback boundary downstream of the Bicoid morphogen establishes rapidly—within approximately 3 minutes after each nuclear mitosis—far more quickly than predicted by theoretical models [19]. Subsequent adaptations, including the PP7/PCP, boxB/λN, and Qβ/QβP systems, have enabled multiplexed imaging of different transcriptional loci [19].

These technologies have unveiled the ubiquitous phenomenon of transcriptional bursting, where gene expression occurs in discrete, stochastic pulses rather than continuously. The simplest model describing this is a two-state system where promoters transition between ON and OFF states, with transcription initiating at rate Kr only in the ON state [19]. In Drosophila embryos, these transcriptional bursts are regulated by enhancer-promoter interactions, morphogen concentrations, and epigenetic modifications, providing a dynamic mechanism for decoding positional information [19].

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Drosophila Transcriptional Imaging

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| MS2/MCP System | MCP-GFP binds MS2 stem-loops in RNA | Real-time visualization of nascent transcription |

| PP7/PCP System | PCP-GFP binds PP7 stem-loops in RNA | Multiplexed imaging with MS2 system |

| Fluorescent Biosensors | Live tracking of protein dynamics | Morphogen gradient quantification |

| Hsp70 Promoter | Drives MCP-GFP expression | Consistent marker protein supply |

Experimental Protocol: Live Imaging of Transcription Dynamics

Objective: To visualize real-time transcription dynamics of a target gene in living Drosophila embryos using the MS2/MCP system.

Procedure:

- Generate transgenic fly lines: Create a fly line expressing MCP fused to a fluorescent protein (e.g., MCP-GFP) under a ubiquitously active promoter (e.g., Hsp70). Generate a separate reporter line with the gene of interest containing 24x MS2 stem-loops in its 3'UTR.

- Cross lines and collect embryos: Cross the two lines and collect embryos at desired developmental stages.

- Prepare for live imaging: Dechorionate embryos and mount in halocarbon oil on a glass-bottom dish. Maintain appropriate temperature (typically 25°C) throughout imaging.

- Image acquisition: Use a confocal or light-sheet microscope with high temporal resolution (5-30 second intervals) to capture fluorescence signal from transcriptional loci.

- Data analysis: Quantify burst properties (frequency, duration, intensity) using spot detection algorithms and fit data to kinetic models of transcription.

Zebrafish: Visualizing Signaling Dynamics in Vertebrates

Advantages for Live Imaging and Chemical Screening

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) offers unique advantages for studying positional information mechanisms in vertebrates, including external development, optical clarity, and genetic tractability. These features enable unparalleled live imaging of signaling dynamics during pattern formation. Zebrafish have been particularly instrumental in studying cytoneme-mediated signaling, specialized actin-based membrane extensions that enable direct cell-to-cell contact and precise ligand-receptor exchange [20]. These dynamic structures, ranging from 1 μm to over 200 μm in length, establish synaptic-like connections between producing and receiving cells, facilitating the targeted delivery of morphogens such as Hedgehog and Wnt proteins [20].

Cytoneme-Mediated Signaling Mechanisms

Unlike traditional filopodia that primarily serve mechanical sensing functions, cytonemes exhibit molecular polarization, regulated stability, and cargo specificity [20]. In zebrafish, cytonemes enable precise long-range gradient formation that would be challenging to achieve through passive diffusion alone. These structures are enriched with specific signaling receptors and adhesion molecules, allowing them to capture and transport morphogen-receptor complexes with high specificity [20]. The core of cytonemes consists of tightly bundled actin filaments regulated by small GTPases, providing the mechanical strength and flexibility required for their extension, retraction, and directional growth [20].

Table 2: Cytoneme Characteristics Compared to Traditional Filopodia

| Feature | Cytonemes | Traditional Filopodia |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Directed morphogen delivery | Environmental sensing, migration |

| Typical Length | 1 μm to >200 μm | Rarely exceed 10 μm |

| Stability | Regulated, Rho GTPase-dependent | Highly dynamic, rapid turnover |

| Molecular Organization | Polarized signaling components | General sensing machinery |

| Cargo Specificity | Specific morphogen-receptor complexes | Non-specific cytoplasmic transport |

Experimental Protocol: Visualizing Cytoneme Dynamics

Objective: To image and quantify cytoneme dynamics and morphogen transport in living zebrafish embryos.

Procedure:

- Generate transgenic lines: Create zebrafish lines expressing fluorescently tagged morphogens (e.g., Shh-GFP) or cytoneme markers (e.g., LifeAct-mCherry) under tissue-specific promoters.

- Microinjection: Alternatively, inject mRNA encoding fluorescent fusion proteins into 1-4 cell stage embryos.

- Mount embryos for imaging: At desired developmental stages, embed embryos in low-melting-point agarose to restrict movement while maintaining viability.

- Time-lapse imaging: Use spinning disk confocal or light-sheet microscopy with high spatial and temporal resolution to capture cytoneme dynamics.

- Image analysis: Track cytoneme extension/retraction rates, lifetime, and morphogen transport using particle tracking algorithms and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP).

Chick Embryo: Bridging Comparative and Molecular Studies

Accessibility for Experimental Manipulation

The chick embryo has served as a foundational model for developmental biology for over a century, offering unique advantages for studying positional information mechanisms, particularly in limb patterning and neural crest development. Its accessibility for surgical manipulation, electroporation, and transplantation makes it ideal for testing hypotheses about cell fate specification and tissue patterning. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies of chick cranial neural crest cells have revealed molecular diversity and dynamics within migratory streams, identifying transcriptional signatures associated with invasive "Trailblazer" cells that lead collective migration into branchial arches [21].

Conservation of Pattering Mechanisms

Direct comparative analysis between chick and mouse pharyngeal arches using scRNA-seq has demonstrated conservation of core transcriptional programs governing neural crest migration and patterning. When chick and mouse datasets are integrated using canonical correlation analysis in Seurat, most clusters consist of mixtures of cells from both species, indicating shared underlying genetic programs [21]. This conservation is particularly evident in Trailblazer signature genes, which are expressed in both species and likely represent core components of the invasion machinery required for neural crest migration [21]. These comparative approaches strengthen the theory that certain cell behaviors, like Trailblazer-mediated invasion, represent fundamental features of migratory cells across vertebrate species.

Experimental Protocol: scRNA-seq of Migratory Neural Crest Cells

Objective: To profile transcriptional states of migrating neural crest cells in chick embryos using single-cell RNA sequencing.

Procedure:

- Tissue dissection: Isolate pharyngeal arches 1 and 2 from chick embryos at HH13 stage. For higher resolution, separate the front 20% and back 80% of arches as distinct samples.

- Single-cell dissociation: Digest tissues in collagenase/dispase solution to create single-cell suspensions while preserving viability.

- Cell capture and library preparation: Use 10x Genomics Chromium platform to capture individual cells and prepare barcoded cDNA libraries following manufacturer's protocol.