Decoding the Hox Regulatory Network in Limb Development: From Genomic Profiling to Therapeutic Insights

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the current methodologies, challenges, and applications of gene expression profiling for identifying Hox target genes in the...

Decoding the Hox Regulatory Network in Limb Development: From Genomic Profiling to Therapeutic Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the current methodologies, challenges, and applications of gene expression profiling for identifying Hox target genes in the developing limb. It explores the foundational principles of Hox gene function in limb patterning, details cutting-edge genomic and epigenomic techniques for target discovery, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in validation, and discusses the critical importance of functional validation in vivo. By synthesizing findings from model organisms and human genetic studies, this review highlights how understanding Hox-regulated networks informs the pathogenesis of congenital limb malformations and opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Hox Genes as Master Regulators of Limb Patterning: Principles and Paradigms

The development of the vertebrate limb, a classic model in developmental biology, is governed by a complex interplay of genetic signals that specify the position, identity, and pattern of skeletal elements. Central to this process is the Hox code—a combinatorial expression of Hox genes along the limb axes that provides mesenchymal cells with positional identity [1]. These identities are later interpreted to guide the formation of specific limb structures, a process crucial for both normal development and evolutionary diversification. Within the context of a broader thesis on gene expression profiling, understanding the Hox-dependent regulatory network is paramount. This Application Note details the experimental frameworks and analytical protocols for identifying and validating Hox target genes and their functional roles in limb patterning, providing a practical resource for researchers aiming to decipher this complex genomic landscape.

Deciphering the Hox Code: Core Concepts and Regulatory Principles

The Hox code operates on several foundational principles that dictate its output during limb development.

- Paralogous Group Function: Hox genes are organized into 13 paralogous groups (PG). Their function in the limb is partially modular, with genes from PG9 and PG10 primarily patterning the stylopod (e.g., humerus), PG11 genes patterning the zeugopod (e.g., radius/ulna), and PG12 and PG13 genes governing autopod (wrist and digit) formation [2].

- Temporal Phasing and Collinearity: Hox gene expression in the limb occurs in two major waves. An early phase, involving genes from PG4 to PG11, helps establish the limb field and proximal identities. A later phase, particularly of 5’ HoxA and HoxD genes (e.g., Hoxa13, Hoxd13), is critical for distal autopod patterning [1]. This sequential activation mirrors the temporal collinearity observed along the main body axis.

- Combinatorial and Redundant Codes: A key challenge in studying Hox genes is their extensive functional redundancy. Meaningful phenotypes often emerge only when multiple paralogous and flanking genes are disrupted. For instance, while single mutants for Hoxa11 or Hoxd11 show mild zeugopod defects, the double mutant displays a striking reduction of the ulna and radius [2]. This necessitates sophisticated genetic strategies to uncover their full function.

- A Bimodal Regulatory Landscape: The expression of Hox genes, particularly in the HoxD cluster, is controlled by a bimodal regulatory system. Two large, independent chromatin domains—a telomeric domain (T-DOM) and a centromeric domain (C-DOM)—sequentially engage with the gene cluster [3]. Genes at the 3’ end of the cluster (Hoxd1 to Hoxd8) are regulated by T-DOM, while 5’ genes (Hoxd9 to Hoxd13) are controlled by C-DOM. The region of low Hoxd expression where this regulatory shift occurs corresponds to the future wrist and ankle articulations [3].

Table 1: Key Hox Paralog Groups and Their Primary Roles in Murine Limb Patterning

| Paralog Group | Key Genes | Primary Limb Domain | Major Skeletal Elements Affected | Representative Phenotype of Multigene Mutants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG9/PG10 | Hoxa9,10 / Hoxd9,10 | Stylopod | Humerus, Femur | Reduction and malformation of stylopod elements [2] |

| PG11 | Hoxa11 / Hoxd11 | Zeugopod | Ulna, Radius, Tibia, Fibula | Severe reduction of ulna and radius [2] |

| PG12/PG13 | Hoxa13 / Hoxd13 | Autopod | Wrist, Ankle, Digits | Complete loss of autopod elements [2] |

Application Notes: Experimental Models for Functional Genomics of Hox Genes

Loss-of-Function Studies

Defining the function of Hox genes requires models that overcome redundancy.

- Multigene Frameshift Mutations: A powerful method involves using recombineering to simultaneously introduce frameshift mutations into multiple flanking Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa9,10,11 and Hoxd9,10,11). This approach disrupts coding sequences while leaving intergenic enhancers and non-coding RNAs intact, minimizing compensatory misexpression seen in large cluster deletions [2].

- Dominant-Negative Approaches in Chick: For rapid assessment of Hox function, electroporation of dominant-negative (DN) Hox constructs in the chick limb bud is effective. These DN variants lack the DNA-binding C-terminal homeodomain but retain co-factor binding ability, thereby suppressing the function of endogenous wild-type Hox proteins [4].

Gain-of-Function and Lineage Reprogramming

- Respecification of Limb Position: Gain-of-function experiments reveal that Hox genes are not just permissive but instructive. Misexpression of Hox6/7 genes in the neck lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) is sufficient to reprogram this tissue to form an ectopic limb bud, demonstrating that these genes provide a key instructive signal that defines the final position of the forelimb [4].

Protocols: Identifying Hox Targets via Genomic Profiling

A core objective of modern limb research is to move from Hox gene expression to the networks they regulate. The following protocol outlines a workflow for identifying Hox target genes using laser capture microdissection (LCM) and RNA-Seq, based on validated studies [2].

Protocol 1: Gene Expression Profiling of Hox-Dependent Compartments

Objective: To identify downstream gene expression changes in specific limb compartments resulting from Hox gene mutations.

Materials and Reagents:

- Wild-type and Hox mutant mouse embryos (e.g., Hoxa9,10,11-/-/Hoxd9,10,11-/-).

- RNA stabilization reagent (e.g., RNAlater).

- Standard equipment for histology and cryosectioning.

- Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) system.

- RNA extraction kit (compatible with low input, e.g., from Arcturus).

- RNA-Seq library preparation kit (e.g., SMART-Seq v4 for ultra-low input RNA).

Method Details:

- Tissue Collection and Preparation: Harvest forelimbs from E15.5 mouse embryos. This stage captures active endochondral ossification in the zeugopod. Immediately place tissues in RNA stabilizer, then embed in OCT compound for cryosectioning.

- Compartment Microdissection: Section limbs to a thickness of 5-10 µm. Using LCM, precisely isolate cells from three distinct compartments of the zeugopod:

- Resting Zone

- Proliferative Zone

- Hypertrophic Zone

- RNA Isolation and Sequencing: Extract total RNA from each captured cell population. Prepare RNA-Seq libraries and perform deep sequencing (e.g., Illumina platform). This process should be performed in triplicate for each genotype and compartment.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Read Alignment and Quantification: Align sequence reads to the reference genome (e.g., mm10) using a splice-aware aligner like STAR. Quantify gene-level counts with tools such as HTSeq.

- Differential Expression: Use R/Bioconductor packages (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) to identify genes that are significantly differentially expressed between wild-type and mutant samples in each compartment. Apply a false discovery rate (FDR) correction of p < 0.05.

- Pathway and Enrichment Analysis: Input lists of differentially expressed genes into functional annotation tools (e.g., DAVID, clusterProfiler) to identify enriched KEGG pathways and Gene Ontology (GO) terms related to limb development, chondrogenesis, and bone morphogenesis.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol successfully identified significant downregulation of key developmental genes in the Hox mutant, including Pknox2, Zfp467, Gdf5, Bmpr1b, Igf1, and Hand2, providing a direct link between the Hox code and the regulation of critical growth and patterning pathways [2].

Protocol 2: Computational Analysis of Non-Coding Variants in Hox Target Regions

Objective: To prioritize non-coding genetic variants that may disrupt Hox-binding sites or enhancers, potentially contributing to limb malformations.

Materials and Reagents:

- List of non-coding variants of interest (e.g., from whole-genome sequencing).

- High-performance computing cluster with GPU capabilities.

- Software: Deep learning models (Basenji2, Enformer), R packages (WGCNA, clusterProfiler, biomaRt).

Method Details:

- Variant Score Prediction:

- Format the variant set (VCF file) into a tab-separated file with columns: chromosome, position, ID, reference allele, alternative allele.

- Use deep learning models (Basenji2 or Enformer) to predict the functional impact of each allele on cell- and tissue-specific gene expression or epigenetic modifications. These models compare the predicted regulatory activity of reference and alternative alleles.

- Statistical Comparison and Module Creation:

- Statistically compare the deep-learning-predicted functional scores between case and control groups.

- Use Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to group variants into modules based on the correlation patterns of their functional scores across samples.

- Trait Correlation and Functional Enrichment:

- Correlate the "eigengene" of each module with specific phenotypic traits of interest (e.g., limb measurement ratios from MRI).

- Prioritize variants that are both statistically different between groups and whose scores correlate with the trait.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., with clusterProfiler) on genes linked to the prioritized variants to identify affected biological pathways [5].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

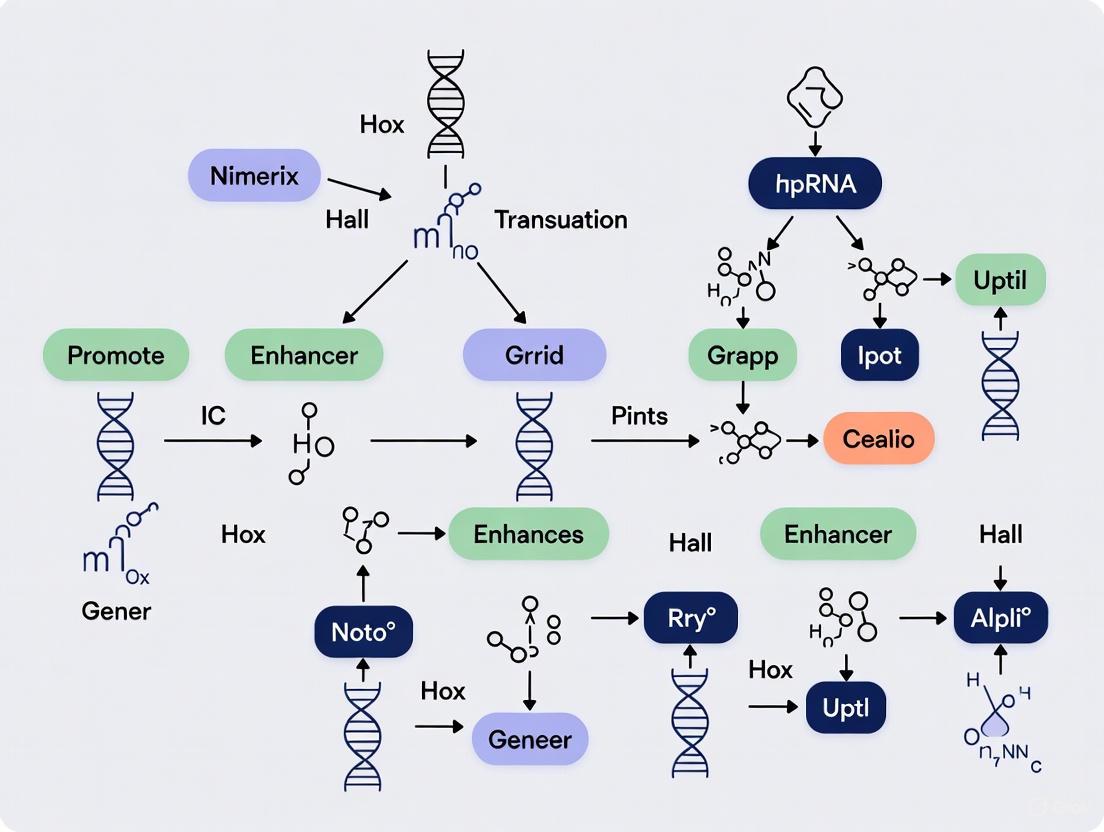

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, summarize key Hox-regulated pathways and the experimental protocol for target gene identification.

Diagram 1: Hox-Regulated Signaling in Limb Development. This diagram illustrates the core genetic and signaling interactions governed by the Hox code. Hox genes directly activate Tbx5, which in turn induces Fgf10 expression in the mesoderm. Fgf10 signals to the overlying ectoderm to establish Fgf8 expression in the Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER), creating a positive feedback loop essential for limb bud outgrowth. Simultaneously, Hox genes regulate Shh in the Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA) for anterior-posterior patterning. Ultimately, Hox proteins directly regulate downstream target genes that execute chondrogenesis and ossification programs [4] [6] [2].

Diagram 2: Target Gene Identification Workflow. The experimental pipeline for identifying Hox target genes begins with the collection of embryonic limb tissue at a key developmental stage (e.g., E15.5). Specific compartments are isolated via Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) before RNA extraction, sequencing, and subsequent bioinformatic analysis for differential expression and pathway enrichment [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Limb Research

| Reagent / Model | Category | Key Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxa9,10,11-/-/Hoxd9,10,11-/- Mutant Mouse | Genetic Model | Overcomes functional redundancy to reveal severe combined phenotypes. | Studying zeugopod formation and Hox regulation of Shh and Fgf8 [2]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Molecular Tool | Suppresses endogenous Hox function in a temporally and spatially controlled manner. | Electroporation in chick limb bud to assess necessity of specific Hox genes [4]. |

| Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) | Equipment | Enables precise isolation of homogeneous cell populations from complex tissues. | Isolating RNA from resting, proliferative, and hypertrophic chondrocyte zones for RNA-Seq [2]. |

| Basenji2 / Enformer Models | Computational Tool | Deep learning models that predict the functional impact of non-coding genetic variants on gene regulation. | Scoring non-coding variants in limb enhancers to prioritize candidates for functional studies [5]. |

| CAP-SELEX Screening | In Vitro Assay | Maps biochemical interactions and composite DNA-binding motifs for transcription factor pairs. | Identifying cooperative binding between HOX proteins and other TFs (e.g., HOX13-MEIS1) [7]. |

Spatial and Temporal Collinearity in Hox Gene Expression

The Hox gene family, comprising 39 transcription factors in mammals arranged in four clusters (A, B, C, and D), represents one of the most evolutionarily conserved developmental regulatory systems. These genes play a pivotal role in conferring positional identity along the anteroposterior (AP) axis during embryonic development. The phenomenon of collinearity—where the genomic organization of Hox genes correlates with their expression patterns—manifests in two principal forms: spatial collinearity, where the position of a gene within a cluster corresponds to its expression domain along the AP axis, and temporal collinearity, where the sequential order of gene activation mirrors their 3' to 5' chromosomal arrangement.

Understanding these mechanisms is particularly crucial in limb development, where Hox genes from the posterior paralog groups (9-13) orchestrate patterning along the proximodistal (PD) axis. The vertebrate limb is divided into three segments: the proximal stylopod (humerus/femur), the medial zeugopod (radius-ulna/tibia-fibula), and the distal autopod (hand/foot bones), each specified by distinct Hox paralog groups. This application note details experimental frameworks and analytical protocols for investigating Hox collinearity within the context of limb research, providing researchers with robust methodologies to identify Hox target genes and elucidate their roles in musculoskeletal patterning.

Fundamental Principles of Collinearity

Spatial Collinearity

Spatial collinearity establishes that a Hox gene's position within its cluster determines its expression boundaries along the AP axis. Genes at the 3' end of clusters (e.g., paralog groups 1-4) are expressed in anterior regions, while genes at the 5' end (e.g., paralog groups 9-13) are expressed in progressively more posterior regions. In limb development, this principle extends to the PD axis, where Hoxd and Hoxa genes exhibit dynamic, overlapping expression domains that prefigure the emergence of limb segments.

Temporal Collinearity

Temporal collinearity describes the sequential activation of Hox genes during development, with 3' genes activated early and 5' genes activated later in development. This phenomenon represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in vertebrate embryogenesis, though its existence and mechanisms continue to be refined through ongoing research. The sequential activation is thought to be harmonized with the progressive emergence of axial tissues, creating a precise coordination between developmental timing and positional specification.

Table 1: Key Hox Paralogs in Vertebrate Limb Patterning

| Paralog Group | Chromosomal Location | Limb Expression Domain | Loss-of-Function Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox9 | 3' regions | Early limb bud Disruption of SHH initiation, AP patterning defects | |

| Hox10 | Mid-cluster | Stylopod (proximal) Severe stylopod mis-patterning | |

| Hox11 | Mid-cluster | Zeugopod (medial) Severe zeugopod mis-patterning | |

| Hox12-13 | 5' regions | Autopod (distal) Complete loss of autopod skeletal elements |

Analytical Framework for Hox Gene Expression Profiling

Spatial Transcriptomic Approaches

Spatial transcriptomic tools provide powerful methods for investigating targeted gene expression patterns while preserving tissue architecture, thereby maintaining the crucial spatial context of Hox gene expression. The Curio platform represents a robust spatial transcriptomic tool that facilitates high-throughput comprehensive spatial gene expression analysis across the entire transcriptome with high efficiency.

Protocol 1: Spatial Gene Expression Analysis of Hox Genes in Mouse Limb Tissue Using Curio

Tissue Preparation:

- Collect mouse embryonic limb tissues at appropriate developmental stages (E11.5-E13.5 for limb patterning)

- Flash-freeze tissues in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound

- Cryosection at 10-20 μm thickness and mount on Curio slides

Library Construction:

- Perform reverse transcription with gene-specific primers targeting Hox genes of interest

- Conduct in situ amplification with barcoded primers

- Implement ligation chemistry to capture spatial information

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence libraries on appropriate Illumina platforms

- Align reads to reference genome (mm10 for mouse)

- Visualize Hox gene expression patterns in spatial context

- Identify spatially restricted expression domains along PD limb axis

This approach enables researchers to visualize and understand Hox gene expression while maintaining tissue integrity, providing crucial insights into how Hox expression domains correspond to morphological boundaries in developing limbs.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Rostrocaudal Patterning

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables comprehensive profiling of Hox expression patterns across multiple cell types along the AP axis. Recent work on the human fetal spine demonstrates the power of this approach for defining position-specific Hox codes.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Analysis of Hox Codes in Developing Tissues

Tissue Dissociation and Cell Sorting:

- Dissect tissues from precise anatomical segments using anatomical landmarks

- Process segments separately to maintain spatial information

- Generate single-cell suspensions using standard enzymatic digestion

- Enrich for viable cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Utilize droplet-based scRNA-seq methods (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium)

- Target sequencing depth of 50,000 reads per cell

- Include unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for accurate quantification

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform quality control filtering to remove low-quality cells

- Conduct dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) and clustering

- Identify differentially expressed Hox genes across anatomical segments

- Define position-specific Hox codes for each cell type

This approach revealed that neural crest derivatives unexpectedly retain the anatomical Hox code of their origin while also adopting the code of their destination, a trend confirmed across multiple organs including the fetal limb, gut, and adrenal gland.

Table 2: Position-Specific Hox Gene Expression in Human Fetal Development

| Anatomical Region | Key Hox Markers | Expression Specificity | Cell Types with Strongest Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | HOXA5, HOXB-AS3, HOXC4, HOXB6 | High region specificity Osteochondral cells, meningeal cells | |

| Thoracic | HOXC5 | Moderate specificity Meningeal cells, mesenchymal progenitors | |

| Lumbar | HOXA10, HOXC10 | Moderate specificity Osteochondral cells, tendon cells | |

| Sacral | HOXC11, HOXA13, HOXD13 | High region specificity Osteochondral cells, mesenchymal cells |

Investigating Chromatin Architecture in Hox Regulation

Chromatin Interaction Analysis

Chromatin organization plays a critical role in Hox gene regulation, particularly through the formation of long-range chromatin interactions that bring enhancers into proximity with target promoters. Techniques such as ChIA-PET (Chromatin Interaction Analysis with Paired-End Tag Sequencing) and Hi-TrAC/TrAC-looping provide powerful tools for mapping these interactions.

Protocol 3: Comprehensive Chromatin Interaction Analysis Using cLoops2

Data Preprocessing:

- Map raw paired-end reads to reference genome using Bowtie2 with MAPQ ≥10 filter

- Preprocess reads into paired-end tags (PETs) representing interaction events

- Perform quality control to remove technical artifacts

Peak Calling:

- Execute cLoops2 callPeaks module with parameters: -eps 100,200 -minPts 5

- Use blockDBSCAN algorithm to identify candidate peak regions

- Calculate statistical significance using Poisson test against local background

Loop Calling and Analysis:

- Identify significant chromatin interactions using permuted local background

- Annotate loops with genomic features (promoters, enhancers)

- Perform differentially enriched loops calling between conditions

- Visualize interactions using integrated visualization modules

The cLoops2 pipeline facilitates comprehensive interpretation of 3D chromatin interaction data, particularly for loop-centric analysis of cis-regulatory elements, providing crucial insights into how chromatin architecture governs the precise spatial and temporal expression of Hox genes during limb development.

Computational and Bioinformatics Pipelines

Differential Gene Expression Analysis

Identifying Hox target genes requires robust computational pipelines for differential expression analysis from RNA sequencing data. The RumBall platform provides a user-friendly, scalable, and reproducible solution for comprehensive bulk RNA-seq analysis.

Protocol 4: Identification of Hox-Regulated Genes Using RumBall

Software Setup:

- Install Docker on your computational system

- Download RumBall Docker image:

docker pull rnakato/rumball - Verify installation:

docker run --rm -it rnakato/rumball star.sh

Data Processing:

- Obtain FASTQ files from public repositories or sequencing cores

- Perform quality control using FastQC

- Map reads to reference genome using STAR aligner

- Quantify gene expression using RSEM

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Execute differential expression testing using DESeq2 or edgeR

- Apply multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg)

- Filter for significant differentially expressed genes (adj. p-value < 0.05)

- Perform gene ontology enrichment using ClusterProfiler

This pipeline enables researchers to identify downstream targets of Hox genes in limb development, facilitating the reconstruction of Hox-regulated genetic networks that control patterning and morphogenesis.

Experimental Models and Functional Validation

Limb Mesenchymal Patterning Systems

The vertebrate limb provides an excellent model for studying Hox function in musculoskeletal development, where bone, tendon, and muscle tissues must be appropriately patterned and precisely connected for physiologically relevant movement. Hox genes play critical roles in patterning all musculoskeletal tissues of the limb, with surprising recent findings that they are not expressed in differentiated cartilage or skeletal cells, but rather are highly expressed in the tightly associated stromal connective tissues as well as regionally expressed in tendons and muscle connective tissue.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Limb Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Curio Seeker Kit | Spatial transcriptomics | Curio Biosystems |

| 10X Genomics Chromium | Single-cell RNA sequencing | 10X Genomics |

| cLoops2 Software | Chromatin interaction analysis | GitHub Repository |

| RumBall Docker Container | RNA-seq analysis pipeline | DockerHub |

| Hox Antibody Panels | Protein localization | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank |

| Limb Mesenchyme Culture Systems | Functional validation of Hox targets | Primary cell culture protocols |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The following diagram illustrates the integrated regulatory network governing Hox gene expression and function during limb development, incorporating key signaling pathways and chromatin-level regulation:

Hox Regulatory Network in Limb Development

The integrated application of spatial genomic technologies, single-cell transcriptomics, and chromatin interaction mapping provides unprecedented resolution for investigating Hox gene collinearity in limb development. The protocols and analytical frameworks outlined in this application note empower researchers to dissect the complex regulatory hierarchies governing Hox-mediated patterning, with particular utility for identifying direct Hox target genes in specific limb compartments.

Future advancements will likely focus on multi-omic integration—combining spatial transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility, and protein localization data—to build comprehensive models of Hox regulatory networks. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated computational tools for analyzing temporal dynamics of Hox expression will further elucidate how collinearity is established and maintained throughout the progression of limb morphogenesis. These approaches will continue to illuminate the fundamental principles of developmental patterning while providing insights relevant to congenital limb abnormalities and regenerative medicine applications.

The study of Hox genes—key regulators of anteroposterior patterning in metazoans—relies on complementary model systems that each provide unique experimental advantages. Drosophila melanogaster and various vertebrate limb bud systems collectively enable comprehensive dissection of Hox gene function, regulation, and evolution. These systems reveal both conserved mechanisms and lineage-specific adaptations in Hox-mediated patterning, particularly in appendage development. The fruit fly haltere, a modified hindwing balancing organ, serves as a powerful paradigm for understanding how Hox genes specify distinct morphological identities in serially homologous structures [8]. Conversely, vertebrate limb buds from mouse, chick, and emerging models like bat wings and pig limbs provide insights into how Hox transcription factors orchestrate complex three-dimensional patterning in evolving morphologies [9] [10] [11]. This Application Note details experimental approaches for identifying Hox target genes across these systems, framed within a gene expression profiling workflow essential for limb researchers.

Experimental Models and Their Key Characteristics

Table 1: Key Model Systems for Studying Hox Gene Function in Appendage Development

| Model System | Key Hox Genes | Experimental Advantages | Morphological Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila haltere | Ultrabithorax (Ubx) | Genetic tractability, extensive toolbox, rapid generation time | Wing-to-haltere transformation, trichome patterns, gene expression changes |

| Mouse limb bud | Hoxa/d clusters (e.g., Hoxd11-d13) | Genetic manipulation, well-characterized development, mutant strains | Digit patterning, skeletal preparations, AP polarity |

| Chick limb bud | Hoxd genes | Accessibility for manipulation, electroporation, bead implantation | Skeletal patterning, gene expression via in situ hybridization |

| Bat wing | Hox genes, Meis2, Pdgfd | Extreme morphological adaptation, single-cell approaches | Digit elongation, membrane expansion, chondrogenesis vs. osteogenesis |

| Pig limb bud | Hoxd genes, Shh targets | Evolutionary adaptation digit loss/reduction | Digit reduction, AP polarity loss, AER-Fgf8 dynamics |

| Crustacean embryo | Hox genes | Evolutionary diversity, embryonic accessibility | Body segmentation, appendage specialization |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Cross-Species Identification of Hox Targets Using ChIP-seq

Purpose: To identify direct transcriptional targets of Hox proteins across evolutionary distant species and uncover conserved versus lineage-specific regulatory networks.

Materials:

- Species-specific Ubx/AbdB-class antibodies (non-cross-reactive)

- Developing appendage tissue (wing buds, haltere discs, limb buds)

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation kit

- High-throughput sequencing platform

- Bioinformatics pipeline for comparative genomics

Procedure:

- Generate species-specific Hox antibodies: Design antibodies against divergent N-terminal regions of Hox proteins to avoid cross-reactivity [8].

- Collect embryonic tissue: Dissect appendage primordia at equivalent developmental stages based on morphological landmarks.

- Perform Chromatin Immunoprecipitation: Cross-link proteins to DNA, shear chromatin, immunoprecipitate with Hox-specific antibodies.

- Library preparation and sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries from immunoprecipitated DNA and input controls.

- Bioinformatic analysis: Identify peaks representing bound genomic regions using MACS2 or similar tools.

- Comparative genomics: Align bound regions across species to distinguish conserved versus species-specific targets.

Troubleshooting: Validate antibody specificity using knockout tissue if available. Optimize fixation conditions for each tissue type. Include biological replicates to ensure reproducibility.

Gene Expression Profiling of Hox Mutants Using Single-Cell RNA-seq

Purpose: To characterize cell type-specific transcriptional changes in Hox mutant appendages at high resolution.

Materials:

- Wild-type and Hox mutant embryos

- Single-cell dissociation reagents

- Single-cell RNA-seq platform (e.g., 10X Genomics)

- Cellranger or equivalent analysis pipeline

- R/Python packages for scRNA-seq analysis (Seurat, Scanpy)

Procedure:

- Tissue dissociation: Isolate limb buds or wing discs at appropriate stages and prepare single-cell suspensions [10].

- Single-cell library preparation: Use partitioning system to capture individual cells and barcode transcripts.

- Sequencing: Profile transcriptomes to sufficient depth (typically 50,000 reads/cell).

- Quality control: Filter out low-quality cells, doublets, and dying cells.

- Cell clustering: Identify distinct cell populations using unsupervised clustering.

- Differential expression: Compare gene expression between wild-type and mutant cells across clusters.

- Trajectory analysis: Reconstruct developmental trajectories to identify differentiation defects.

Troubleshooting: Minimize stress during dissociation to preserve native transcriptional states. Include cell hashing or multiplexing to process multiple genotypes together. Validate key findings with orthogonal methods like smFISH.

Functional Validation of Hox Targets Using Transgenic Reporter Assays

Purpose: To test whether putative cis-regulatory elements identified through ChIP-seq or ATAC-seq mediate Hox-responsive expression.

Materials:

- Candidate enhancer elements (conserved or species-specific)

- Minimal promoter-reporter vectors (e.g., lacZ, GFP)

- Germline transformation system (species-appropriate)

- Hox gain/loss-of-function genetic backgrounds

Procedure:

- Clone enhancer elements: Amplify candidate regions (typically 0.5-3kb) and clone upstream of minimal promoter driving reporter.

- Generate transgenic animals: Use species-specific method (P-element transformation, pronuclear injection, electroporation).

- Analyze reporter expression: Characterize expression patterns in wild-type appendages.

- Test Hox responsiveness: Assess reporter expression in Hox gain-of-function and loss-of-function backgrounds.

- Quantify expression changes: Use image analysis or flow cytometry to quantify expression differences.

Troubleshooting: Include positive and negative control reporters. Test multiple independent transgenic lines to account for position effects. For cross-species comparisons, test orthologous enhancers in the same host species to isolate cis-regulatory changes.

Signaling Pathways and Gene Regulatory Networks

Figure 1: Hox Gene Regulatory Network in Appendage Development. Hox genes integrate multiple signaling inputs (SHH, FGF, BMP, WNT, Notch) and cooperate with other transcription factors (Meis2, Tbx, Gli) to regulate downstream processes. Species-specific modifications include delayed chondrogenesis in bat wings and repression of growth in fly halteres.

Comparative Gene Expression Data

Table 2: Hox Gene Expression Dynamics Across Model Systems

| Gene/Pathway | Mouse Limb | Chick Limb | Bat Forelimb | Pig Limb | Drosophila Haltere |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5'Hoxd genes | Asymmetric posterior domain; biphasic regulation [11] | Stronger in forelimb than hindlimb; TAD boundary variation [11] | Upregulated in forelimb; prolonged chondrogenesis [10] | Anterior expansion; symmetric pattern [9] | N/A |

| Shh pathway | Restricted posterior Ptch1; anterior-posterior Gli1 gradient [9] | Similar to mouse with modifications | Notch activation; WNT/β-catenin suppression [10] | Distally restricted Ptch1; anteriorly expanded Gli1 [9] | Hh signaling modified by Ubx |

| Fgf8 expression | Maintained in AER throughout digit patterning [9] | Maintained in AER | Upregulated compared to hindlimb [10] | Reduced and distally restricted in AER [9] | Downregulated by Ubx |

| Chondrogenesis | Balanced with osteogenesis | Balanced with osteogenesis | Prolonged and enhanced (10.5% vs 6.4% in hindlimb) [10] | Normal progression | N/A |

| Key co-factors | Meis2, Tbx4/5, Pitx1 | Meis2, Tbx4/5 | PDGFD+ MPs (11.5% vs 0.7% in hindlimb) [10] | Hand2, Gli3 | Homothorax, Extradenticle |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-specific antibodies | Anti-Ubx (Apis, Bombyx, Drosophila), Anti-Hoxd [8] | Immunodetection, ChIP, functional perturbation | Must target divergent N-terminal to avoid cross-reactivity |

| Transcriptomic tools | Microarrays, RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq [12] [10] [13] | Gene expression profiling, cell type identification | Stage-matching critical for comparisons; batch effects |

| Epigenomic methods | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, Hi-C, 4C-seq [14] [9] [11] | cis-regulatory element mapping, 3D genome architecture | Fixation optimization needed for different tissues |

| Transgenic systems | P-element vectors, Cre/lox, electroporation, CRISPR [14] [8] | Functional validation, lineage tracing, gene editing | Species-specific optimization required |

| In situ hybridization | RNAscope, whole-mount RNA in situ [9] [15] | Spatial expression patterning | Probe design for cross-species comparisons |

| Live imaging tools | Membrane-GFP, time-lapse microscopy [16] | Morphogenesis tracking | Tissue culture conditions for ex vivo development |

Experimental Workflow for Cross-Species Hox Studies

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Cross-Species Hox Target Identification. This pipeline enables systematic identification and validation of Hox targets across evolutionarily divergent species, from tissue collection through functional mechanism elucidation.

Interpretation Guidelines and Data Analysis

When comparing Hox gene function across model systems, researchers should consider several key analytical approaches:

Evolutionary analysis: Distinguish between conserved targets (likely ancestral Hox network components) and species-specific targets (potentially mediating morphological innovations). Approximately 15-20% of Ubx targets are conserved between Drosophila, Apis, and Bombyx despite 300 million years of divergence [8].

Expression dynamics: Note that conserved binding does not necessarily imply conserved expression outcomes. Many Hox targets show differential expression in Drosophila wing versus haltere but not between forewing and hindwing in Apis or Bombyx, suggesting changes in co-factor recruitment or enhancer logic [8].

Regulatory mechanism: Consider the role of 3D genome architecture in Hox regulation. Variations in TAD boundaries between mouse and chick correlate with differential Hoxd expression in forelimb versus hindlimb [11].

Quantitative imaging: When analyzing skeletal phenotypes or gene expression patterns, use cranial width or other conserved structures for normalization to account for allometric differences, as demonstrated in bat studies [10].

Applications in Drug Development and Disease Modeling

Hox gene research in model systems provides valuable insights for human biomedical applications:

Neurogenesis: Genome-wide screening in human embryonic stem cell-derived neuronal cells reveals essential, non-redundant roles for HOXA6 and HOXB6 in caudal neurogenesis, suggesting paralog-specific functions relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders [17].

Congenital limb defects: The identification of ~30% novel genes in murine limb development through transcriptomics [13] expands the candidate gene list for human limb malformations, which occur in approximately 1 in 1000 live births.

Evolutionary medicine: Understanding how bats maintain interdigital membranes through balanced FGF/BMP signaling [10] or how pigs lose digits through altered SHH response [9] informs potential regenerative medicine approaches.

The Hox family of homeodomain-containing transcription factors are master regulators of embryonic patterning, conferring cellular identity along the anterior-posterior axis during development [18] [19]. Despite their highly conserved homeodomains that bind similar AT-rich DNA sequences in vitro, individual Hox proteins execute distinct developmental programs in vivo, presenting a long-standing question known as the "Hox specificity paradox" [19] [20]. The resolution to this paradox lies in their collaboration with cofactors from the Three Amino Acid Loop Extension (TALE) homeodomain family, particularly PBX and MEIS proteins [19] [21] [20]. These cofactors form multifactorial complexes with Hox proteins, dramatically enhancing DNA-binding specificity and affinity through cooperative interactions [19] [22]. In limb development and regeneration, Hox proteins function with their TALE cofactors to establish positional memory and pattern limb structures along the anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes [23] [24]. This application note details the molecular mechanisms underlying Hox-TALE collaboration and provides experimental protocols for identifying Hox target genes in limb research, enabling researchers to decipher the gene regulatory networks controlling limb patterning and regeneration.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hox-TALE Complex Formation

Structural Basis of Hox-PBX Interactions

Hox proteins from paralog groups 1-10 typically contain a conserved hexapeptide (HX) motif (with a YPWM core sequence) located N-terminal to the homeodomain [19] [22]. This motif serves as a primary protein interaction interface, binding to the PBC homeodomain of PBX cofactors [19] [22]. Structural analyses reveal that Hox-PBX heterodimer formation on adjacent DNA binding sites generates complexes with significantly enhanced DNA-binding specificity compared to Hox monomers alone [19] [20]. The interaction between the HX motif and PBX is relatively weak in the absence of DNA but stabilizes significantly when both proteins bind adjacent sites on DNA [19]. This cooperative binding enables the recognition of composite DNA sequences that are not efficiently bound by either protein alone, effectively expanding the DNA recognition repertoire and specificity of Hox proteins [19].

Table 1: Key Protein Interaction Motifs in Hox-TALE Complexes

| Motif Name | Consensus Sequence | Location in Hox Protein | Binding Partner | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexapeptide (HX) | YPWM (core) | N-terminal to homeodomain | PBX homeodomain | Primary interface for Hox-PBX dimerization |

| UbdA (UA) | Variant motif | N-terminal region | PBX/EXD | Alternative interaction interface in specific Hox proteins |

| Homeodomain | 60 amino acids | Central DNA-binding domain | DNA major/minor groove | Primary DNA binding; paralog-specific residues contact TALE cofactors |

| Paralog-specific residues | Variable | N-terminal arm of homeodomain | DNA minor groove | Confer latent specificity in DNA shape recognition |

MEIS Integration and Trimeric Complex Formation

MEIS family proteins integrate into Hox-PBX complexes through multiple mechanisms. First, MEIS proteins form stable heterodimers with PBX through conserved N-terminal domains, facilitating nuclear localization of PBX proteins [25] [21]. Second, in trimeric complexes, MEIS binding can remodel Hox-PBX interactions, sometimes rendering the HX motif dispensable through redundant alternative interfaces [22]. For example, the posterior Hox protein HOXA9 can utilize paralog-specific residues within its homeodomain as alternative TALE interaction interfaces when the HX motif is compromised [22]. Third, MEIS proteins contribute to the stability of the complex; PBX3 binding protects MEIS1 from ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation, thereby extending MEIS1 half-life and ensuring sustained complex formation [25] [26]. These multilayered interactions create stable Hox-PBX-MEIS trimeric complexes with distinct DNA-binding properties and transcriptional regulatory capabilities not achievable by any of the components individually [21] [22].

Latent Specificity and DNA Shape Recognition

When Hox proteins form complexes with TALE cofactors, they exhibit "latent specificity" - the revelation of distinguishing DNA-binding preferences that are masked in monomeric binding [19]. Comprehensive DNA binding site selection assays (SELEX-seq) comparing eight Drosophila Hox factors as monomers and in complex with Exd (the Drosophila PBX homolog) demonstrated that differences in binding preferences between Hox factors increased significantly when in complex with Exd [19]. This latent specificity is partly mediated through recognition of DNA shape features, particularly minor groove width [19]. Anterior Hox factors prefer DNA sites with narrower minor grooves, while central/posterior Hox factors favor wider minor grooves [19]. These preferences are determined by paralog-specific residues in the N-terminal arm of the Hox homeodomain that contact the DNA minor groove [19]. The integration of DNA shape readout with sequence-specific binding provides an additional layer of specificity to Hox-TALE complexes.

Diagram 1: Molecular architecture of Hox-PBX-MEIS trimeric complex formation on DNA. The complex recognizes composite DNA binding sites through cooperative interactions.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Hox-TALE Interactions

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for Complex Formation

Purpose: To detect and characterize protein-DNA complexes formed by Hox proteins and TALE cofactors in vitro.

Protocol:

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify recombinant Hox, PBX, and MEIS proteins. Truncated constructs containing key domains (e.g., Hox proteins with intact homeodomains and HX motifs) can be used to map interaction interfaces [22].

- DNA Probe Design: Design and end-label double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing predicted Hox-TALE binding sites. Consensus sites like CENT/POST (for posterior Hox proteins) or specific genomic enhancer elements are appropriate [22].

- Binding Reactions: Incubate proteins with DNA probes in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 50 µg/mL poly(dI-dC)) for 30 minutes at room temperature [22].

- Electrophoresis: Resolve protein-DNA complexes on a 4-6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer at 4°C.

- Analysis: Visualize complexes by autoradiography or phosphorimaging. Include controls with individual proteins and mutated binding sites to verify specificity.

Application Notes: EMSA with Hox protein mutants (e.g., HX motif mutations) reveals the contribution of specific interfaces to complex formation. For HOXA9, EMSA demonstrated that while dimeric HOXA9/PBX1 complex formation depends on the HX motif, trimeric HOXA9/PBX1/MEIS1 complexes can form through alternative interfaces in the homeodomain [22].

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) for Live-Cell Interactions

Purpose: To visualize and quantify Hox-TALE protein interactions in live cells.

Protocol:

- Vector Construction: Clone Hox and TALE genes into BiFC vectors containing complementary non-fluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein (e.g., YFP or Venus) [22].

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect constructs into appropriate cell lines (e.g., HEK293T or limb mesenchymal cells). Include controls with empty vectors and interaction-deficient mutants.

- Fluorescence Detection: Image cells 24-48 hours post-transfection using fluorescence microscopy. Quantify fluorescence intensity as a measure of interaction strength.

- Context Variation: Test interactions in different cell types and under various differentiation states to assess context-dependency.

Application Notes: BiFC analysis of HOXA9 revealed that its interaction with PBX1 occurs in live cells and depends on the homeodomain rather than solely the HX motif [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for assessing how cellular environment influences Hox-TALE interactions.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for Genomic Binding Mapping

Purpose: To identify genome-wide binding sites of Hox-TALE complexes in limb cells.

Protocol:

- Cell Fixation: Cross-link proteins to DNA in limb bud cells or limb-derived cell lines using formaldehyde.

- Chromatin Preparation: Sonicate chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate with antibodies specific to Hox proteins (e.g., HOXA9, HOXD13), PBX, or MEIS proteins. Use pre-immune IgG as control.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and prepare libraries for high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome, call peaks, and identify enriched motifs.

Application Notes: ChIP-seq in mouse models revealed that Hoxa9 and Meis1 co-bind at numerous enhancer regions controlling oncogenes in leukemia [26]. In limb research, similar approaches can identify target genes involved in patterning.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hox-TALE Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pMSCV-Hoxa9, pcDNA3-Pbx1, pCMV-MEIS1 | Protein expression and functional studies | Epitope-tagged versions for detection; retroviral for stable expression |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, Limb bud mesenchymal cells, C3H10T1/2 | Interaction studies and differentiation assays | High transfection efficiency; limb differentiation potential |

| Antibodies | Anti-HOXA9, Anti-PBX1/2/3, Anti-MEIS1, Control IgG | Immunodetection, ChIP, Western blotting | Specificity for target proteins; ChIP-grade for genomic studies |

| DNA Probes | CENT/POST consensus site, ZRS limb enhancer | EMSA, reporter assays | Contain validated Hox-TALE binding sites |

| Chemical Inhibitors | HXR9 (HOX/PBX inhibitor), Cyclopamine (Shh pathway inhibitor) | Functional perturbation studies | Specific disruption of Hox-TALE interactions or downstream pathways |

Hox-TALE Functions in Limb Development and Regeneration

Limb Patterning Along the Axes

In limb development, 5' Hox genes (Hox9-13) play crucial roles in patterning along both the anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes [23]. Gene knockout studies in newts revealed that different Hox genes have specialized and redundant functions in limb formation [23]. While individual knockout of Hox9, Hox10, or Hox12 caused no apparent skeletal abnormalities, Hox11 knockout disrupted posterior zeugopod and autopod elements in both forelimbs and hindlimbs [23]. Furthermore, compound knockouts of Hox9 and Hox10 resulted in substantial loss of stylopod and anterior zeugopod/autopod elements specifically in hindlimbs [23]. These findings demonstrate that Hox9 and Hox10 function redundantly in proximal limb (stylopod) formation, while Hox11 contributes to posterior distal element development [23]. The functional diversification of 5' Hox genes in tetrapod limb development highlights the complexity of Hox-mediated patterning programs executed through collaboration with TALE cofactors.

Positional Memory in Limb Regeneration

Salamander limb regeneration provides a fascinating model for studying Hox-TALE functions in positional memory. Research in axolotls revealed that connective tissue cells retain positional information from embryogenesis in the form of spatially organized gene expression patterns [24]. Posterior cells maintain expression of the transcription factor Hand2, which primes them to express Shh after amputation [24]. During regeneration, a positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh maintains posterior identity, with Hand2 being sustained after regeneration to safeguard posterior memory [24]. This positional memory system allows regenerating cells to re-establish proper patterning along the anterior-posterior axis. The stability of this memory involves positive-feedback mechanisms that can be experimentally manipulated; transient exposure of anterior cells to Shh during regeneration can convert them to a posterior memory state through establishment of an ectopic Hand2-Shh loop [24].

Diagram 2: Hox-mediated positional memory circuit in limb regeneration. The Hand2-Shh positive feedback loop maintains posterior identity and can be experimentally manipulated to alter cell memory.

Data Analysis and Target Gene Identification

Transcriptomic Analysis of Hox-TALE Functions

Gene expression profiling is essential for identifying Hox target genes in limb development. Analysis of anterior versus posterior limb cells in axolotl revealed approximately 300 differentially expressed genes, with Hand2 dominating the posterior cell signature [24]. Bioinformatic approaches can identify Hox target genes by correlating Hox gene expression with potential targets across datasets. In prostate cancer studies, a specific subgroup of HOX genes showed negative correlation with Fos, DUSP1, and ATF3 expression [18]. Similar approaches can be applied to limb datasets to identify candidate Hox targets. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of co-occurring mutational partners in AML revealed over-activation of NOTCH, PI3K, and AEP complex pathways in HOX/MEIS high-expressing cells [27]. In limb research, GSEA can identify pathways coordinately regulated by Hox-TALE complexes.

Table 3: Hox-TALE Target Genes and Functional Pathways

| Target Gene | Hox-TALE Complex | Biological Process | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flt3 | Hoxa9-Meis1-Pbx3 | Hematopoietic proliferation | ChIP-seq shows co-binding at enhancer [25] [26] |

| Trib2 | Hoxa9-Meis1-Pbx3 | Cell transformation | Expression dependent on Pbx3/Meis1 dimerization [25] |

| Shh | Hand2 (posterior Hox) | Limb patterning | Hand2 binds ZRS enhancer; essential for Shh expression [24] |

| Fos | HOX subgroup (negative correlation) | Apoptosis regulation | Negative correlation in prostate cancer [18] |

| DUSP1 | HOX subgroup (negative correlation) | EGFR signaling inhibition | Negative correlation in prostate cancer [18] |

Computational Prediction of Hox-TALE Binding Sites

In silico approaches can predict Hox-TALE binding sites using motif discovery algorithms. SELEX-seq data revealed that Hox-TALE heterodimers preferentially bind specific composite motifs [19]. For example, Exd/Hox heterodimers recognize sites with the consensus sequence, while monomeric Hox binding is less specific [19]. These motifs can be used to scan limb enhancer elements for potential Hox-TALE regulation. When combined with chromatin accessibility data (ATAC-seq) from limb cells, these predictions can prioritize functional binding sites for experimental validation.

The collaboration between Hox proteins and PBX/MEIS cofactors represents a fundamental mechanism for achieving transcriptional specificity in development and disease. In limb research, understanding these interactions provides critical insights into patterning mechanisms and positional memory. Experimental approaches including EMSA, BiFC, and ChIP enable researchers to characterize these complexes and identify their genomic targets. The development of competitive peptide inhibitors like HXR9, which disrupts HOX/PBX interactions, demonstrates the therapeutic potential of targeting these complexes [18]. In limb regeneration studies, manipulating Hox-TALE networks could enhance regenerative outcomes by controlling positional identity. As single-cell technologies advance, mapping the "HOXOME" - the cell-specific transcriptional state of Hox genes - across limb cell types will further illuminate how Hox-TALE complexes orchestrate the intricate patterning of limb structures.

In the study of developmental biology, Hox genes function as master selector genes that specify the identity of body segments and the structures that form there. However, the fundamental question of how these transcription factors ultimately orchestrate the formation of diverse and complex organs remains a central area of research. The answer lies in the conceptual framework of realizator genes—the downstream executors of selector gene commands. This Application Note details the experimental approaches for identifying these critical realizator genes, with a specific focus on applications in limb research. We provide validated protocols for gene expression profiling, data normalization, and functional validation, equipping researchers with the tools to bridge the gap between genetic instruction and phenotypic outcome.

Background: From Hox Selector Genes to Cellular Realizators

Hox genes encode transcription factors that determine structures along the anteroposterior axis in bilaterians, sometimes by modifying a homologous structure and other times by constructing entirely new organs [28]. The classical hypothesis of selector genes, proposed by García-Bellido, posits that Hox genes act by regulating a battery of "realizator" genes, which are directly responsible for executing the basic cellular functions that shape different organs [28]. These functions include, but are not limited to:

- Regulating cell proliferation to control the size and shape of structures.

- Determining distinct cell affinities to guide tissue organization.

- Establishing organ shape through coordinated changes in cell behavior.

A key challenge is that Hox proteins often regulate their targets through complex genetic cascades involving intermediate transcription factors, making the direct realizator targets difficult to pinpoint [28]. In the context of limb development, the regulatory network is particularly intricate. The restricted regional expression of Hox genes defines limb module domains during the paddle stage of development, making this an ideal system for studying their function [29]. Furthermore, post-transcriptional mechanisms like alternative splicing (AS) have been shown to be highly dynamic during mouse and opossum limb development, adding another layer of regulation that can impact the final cellular phenotype [29].

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Hox Targets

The following section outlines a core workflow for identifying and validating direct Hox target genes, which are strong candidates for realizators.

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Identification of Hox-Binding Sites via ChIP-seq

Principle: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) identifies the genomic regions bound by a transcription factor of interest, such as a Hox protein.

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell/ Tissue Preparation: Use limb bud tissue or relevant cell models at the appropriate developmental stage (e.g., paddle stage). Cross-link proteins to DNA with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Quench the reaction with 125 mM glycine.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and isolate nuclei. Shear chromatin to an average fragment size of 200–500 base pairs using sonication. Verify fragment size by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the sheared chromatin with a validated, high-specificity antibody against the target Hox protein (e.g., Anti-Ubx, Anti-Antp). Use pre-immune serum or an isotype control for a mock IP. Protein A/G magnetic beads are used to capture the antibody-chromatin complexes.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads stringently with low-salt, high-salt, and LiCl wash buffers to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the immunoprecipitated complexes and reverse the cross-links.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Purify the DNA. Prepare a sequencing library using a commercial kit (e.g., Illumina). Sequence the library on an appropriate platform to obtain sufficient coverage (typically 20-50 million reads per sample).

- Data Analysis: Map sequenced reads to the reference genome. Call peaks of enrichment in the Hox-IP sample compared to the control using tools like MACS2. These peaks represent potential direct Hox-binding sites.

Visualization of the ChIP-seq Workflow:

Protocol 2: Profiling Gene Expression in Hox-Gain/Loss-of-Function Models

Principle: Comparing transcriptomes (via RNA-seq) from wild-type and Hox-mutant tissues reveals genes whose expression is dependent on the Hox gene, providing a list of potential realizators for functional testing.

Detailed Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Establish at least three biological replicates for each condition:

- Wild-type control limb buds.

- Hox loss-of-function (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 knockout, RNAi knockdown) limb buds.

- Hox gain-of-function (e.g., conditional overexpression) limb buds.

- RNA Extraction:

- Homogenize tissue in QIAzol Lysis Reagent or equivalent.

- Extract total RNA using a commercial kit (e.g., from Qiagen). Treat samples with RNase-Free DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Assess RNA integrity and purity using an instrument like the NanoDrop ND-1000; accept 260/280 ratios of ~2.0 [30].

- Library Prep and RNA-seq:

- Use 1 µg of high-quality total RNA (RIN > 8) for library preparation.

- Construct cDNA libraries with poly-A selection for mRNA enrichment.

- Sequence on a platform such as Illumina NovaSeq to a depth of 25-40 million paired-end reads per sample.

- Differential Expression Analysis:

Protocol 3: Validation of Realizator Gene Expression by qRT-PCR

Principle: Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) provides a sensitive and quantitative method to validate the expression changes of candidate realizator genes identified by ChIP-seq and RNA-seq.

Detailed Methodology:

- cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize cDNA from 1 µg of DNA-free total RNA using a reverse transcription kit (e.g., PrimeScript RT reagent Kit) with oligo(dT) and random hexamer primers.

- qRT-PCR Reaction:

- Prepare reactions in triplicate containing: 1x SYBR Green Master Mix, forward and reverse primers (200 nM each), and cDNA template (diluted 1:10).

- Run on a real-time PCR system (e.g., Applied Biosystems 7500) with the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s [31].

- Critical Normalization:

- Reference Gene Method: Normalize target gene data using the geometric mean of multiple, validated reference genes. Use algorithms like geNorm, NormFinder, and RefFinder to select the most stable reference genes for your specific limb bud samples [31] [30]. For limb development, common candidates include Hprt1, Hsp90aa1, and B2m, but these must be empirically validated.

- Algorithm-Only Method: As an alternative, use the NORMA-Gene algorithm, which requires expression data for at least five genes and uses least squares regression to calculate a normalization factor, potentially reducing variance more effectively than reference genes [30].

Data Presentation and Analysis

The table below synthesizes examples of Hox target genes identified in various studies, illustrating the diversity of realizator functions.

| Hox Gene | Identified Target / Realizator | Function of Target / Assigned Realizator Role | Experimental Evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrabithorax (Ubx) | blistered (Drosophila) | Activation of proteins involved in cell-cell adhesion; required for wing blade formation. | Loss-of-function mutation transforms halteres to wings. | [32] |

| Ultrabithorax (Ubx) | spalt (Drosophila) | Patterns the placement of wing veins. | Ubx represses spalt in halteres; loss of Ubx causes ectopic expression. | [32] |

| Sex combs reduced (Scr) | bric à brac (bab) (Drosophila) | Involved in limb patterning. | Loss of the cofactor dac results in ectopic bab expression and loss of Scr. | [33] |

| HPV16 E7 (HOX regulation) | HOXA10 (Human) | Transcription factor; expression correlates with epithelial marker E-Cadherin. | E7 mediates epigenetic deregulation (H3K4me3/H3K27me3) leading to decreased expression. | [34] |

| Abdominal-A (abd-A) | (Various) | Repression of limb formation in the abdomen. | Ectopic expression in anterior segments transforms them to abdominal identity. | [32] |

Hox-Realizator Gene Regulatory Network in Limb Development

The following diagram summarizes the logical relationships between a Hox selector gene and its downstream realizator targets within a limb development context, based on the findings from the provided research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function / Application in Hox-Realizator Research |

|---|---|

| High-Specificity Hox Antibodies | Essential for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments to pull down DNA bound by specific Hox transcription factors. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Systems | For creating stable Hox loss-of-function models in cell lines or model organisms to study subsequent gene expression changes. |

| RNase-Free DNase I | Critical for removing genomic DNA contamination during RNA extraction, ensuring pure template for RNA-seq and qRT-PCR. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent dye used in qRT-PCR to quantitatively measure the amplification of candidate realizator gene cDNA. |

| Reference Genes (Validated) | Genes with stable expression across experimental conditions (e.g., Hprt1, Hsp90aa1) used for normalization in qRT-PCR. |

| TRIzol/QIAzol Reagent | A monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for the effective denaturation and extraction of total RNA from tissue. |

| NORMA-Gene Algorithm | A normalization method that reduces variance in expression data without the need for pre-validated reference genes. |

Advanced Genomic Technologies for Mapping the Hox Target Landscape

Understanding the precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression is a central goal in developmental biology. In the context of limb formation and regeneration, Hox genes encode key transcription factors that orchestrate patterning along the proximal-distal and anterior-posterior axes [23]. Identifying the complete repertoire of genes directly regulated by Hox proteins is essential for deciphering the genetic networks controlling limb morphogenesis. Genome-wide binding analysis techniques, particularly Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), have become indispensable tools for this purpose, enabling the unbiased mapping of transcription factor occupancy across the entire genome [35].

This application note details the integration of ChIP-seq within a broader research strategy aimed at identifying Hox target genes in limb tissues. We provide a validated experimental workflow, from tissue processing to data interpretation, along with practical considerations for studying chromatin architecture in developing and regenerating limbs.

Two primary methodologies have been used for the genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions: ChIP-chip (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation coupled with DNA microarray) and ChIP-seq. While ChIP-chip hybridizes immunoprecipitated DNA to microarray probes, ChIP-seq leverages next-generation sequencing, offering superior resolution, a larger dynamic range, lower background noise, and less requirement for starting material [35]. Consequently, ChIP-seq has largely superseded ChIP-chip as the method of choice.

The fundamental principle of both techniques is the immunoprecipitation of protein-DNA complexes using a highly specific antibody, followed by the isolation and analysis of the bound DNA fragments. When applied to limb tissues, this allows for the direct identification of Hox binding sites in cis-regulatory elements such as enhancers and promoters.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Genome-Wide Binding Techniques.

| Feature | ChIP-chip | ChIP-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Technology | DNA microarrays | Next-generation sequencing |

| Genomic Coverage | Limited to predefined probes | Comprehensive, entire genome |

| Resolution | ~100 bp (lower) | ~10-50 bp (higher) |

| Input DNA Requirement | High (micrograms) | Low (nanograms) |

| Background Signal | Higher | Lower |

| Primary Application | Historical; targeted studies | Current standard for de novo discovery |

Integrated Workflow for Hox Target Gene Discovery in Limb Tissues

A successful ChIP-seq experiment in limb research follows a multi-stage process, from tissue collection to functional validation. The workflow below outlines the critical path for identifying Hox target genes.

Figure 1: A unified workflow for ChIP-seq analysis in limb tissues, from sample preparation through functional validation.

Stage 1: Experimental Phase

Limb Tissue Collection and Preparation. The unique challenge in limb research is the small size and cellular heterogeneity of the tissue. For studies on mouse embryos, entire limb buds at stages like E10.5, E11.5, and E13.5 are commonly used [36]. Tissues are immediately crosslinked (e.g., with 1% formaldehyde) to freeze protein-DNA interactions. The chromatin is then sheared via sonication to fragments of 200–500 bp. The cellular heterogeneity of limb buds means that ChIP-seq signals represent an average across multiple cell types, which can be mitigated by using large sample pools or emerging single-cell methods [36] [35].

Immunoprecipitation and Sequencing. This is the most critical step, reliant on a high-quality, specific antibody against the Hox protein of interest. The sheared chromatin is incubated with the antibody, and the immunoprecipitated complexes are captured, purified, and reverse-crosslinked to isolate the DNA. This DNA library is then prepared for high-throughput sequencing.

Stage 2: Computational and Integrative Phase

Bioinformatic Analysis. Raw sequencing reads are aligned to the reference genome. Peak calling algorithms are used to identify genomic regions enriched with Hox binding, representing putative direct targets [35]. Subsequent motif analysis can reveal if the bound regions are enriched for the canonical Hox binding motif, validating the specificity of the experiment.

Data Integration with Limb Regulome. To distinguish functionally relevant binding events, Hox ChIP-seq data must be integrated with other genomic datasets from limb tissues. A powerful approach is to overlay Hox peaks with maps of active cis-regulatory elements defined by histone marks like H3K27ac (for active enhancers) or chromatin accessibility data from ATAC-seq [36] [37]. For instance, a comprehensive study of 446 limb-associated gene loci provided a rich resource of putative limb enhancers and their interacting promoters, which can be directly queried for Hox binding [36].

Functional Validation. Finally, candidate target genes and regulatory elements require functional testing. This can be achieved through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of the bound genomic region in animal models like mice or axolotls, followed by assessment of limb phenotypes and gene expression changes [23] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for ChIP-seq in limb research.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Limb Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hox-specific Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of the Hox protein-DNA complex | Critical for pulling down specific Hox proteins (e.g., Hoxd13) from limb bud lysates [36]. |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Efficient capture of antibody-bound complexes | Facilitates the wash and elution steps during the ChIP procedure. |

| Chromatin Shearing Kit | Standardized fragmentation of crosslinked chromatin | Ensures consistent and optimal chromatin fragment size from precious limb samples. |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Kit | Quality control and quantification of ChIP-DNA | Essential for accurately measuring low-yield DNA prior to library prep. |

| ChIP-Seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from IP'd DNA | Compatible with low-input DNA from limited limb tissue. |

| Validated Limb Enhancer Reporters | Functional testing of identified Hox-bound regions | Confirms enhancer activity of bound regions in limb contexts (e.g., via chicken bioassay) [37]. |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Technologies

The field is rapidly moving beyond standard ChIP-seq towards more integrated and dynamic analyses of gene regulation.

Multimodal and Foundation Models. New computational tools, such as the Chromnitron model, are being developed to predict the genome-wide binding landscapes of hundreds of chromatin-associated proteins (CAPs) by integrating DNA sequence, chromatin accessibility, and protein features [38]. This is particularly useful for TFs like some Hox proteins for which high-quality ChIP-grade antibodies are lacking.

Mapping Chromatin Dynamics. Understanding how chromatin architecture changes during limb development or regeneration is key. Techniques like Capture-C have been used to profile the 3D chromatin microarchitecture of hundreds of limb-associated gene loci, revealing tissue- and stage-specific enhancer-promoter interactions [36]. Furthermore, new methods like iNOME-seq enable the simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility, nucleosome positioning, and DNA methylation in living tissues, acting as a "memory repository" of epigenetic status [39].

Defining Positional Memory in Regeneration. In regenerating axolotl limbs, the stability of positional memory—how cells remember their anterior-posterior identity—is mediated by transcription factors like Hand2. Research has shown that a positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh maintains posterior identity, and this memory can be experimentally reprogrammed [24]. ChIP-seq for factors like Hand2 in regenerating blastemas can reveal the direct targets that maintain this positional information.

Figure 2: A positive-feedback loop maintaining positional memory in regeneration. Factors like Hand2 prime cells to express Shh upon injury, and Shh signaling in turn reinforces Hand2 expression, creating a stable memory state [24].

ChIP-seq provides a powerful and direct method to identify the genomic binding sites of Hox transcription factors, thereby uncovering their target genes during limb development and regeneration. A robust ChIP-seq workflow, combined with the integration of complementary epigenomic datasets and functional validation, is essential for building accurate models of limb gene regulatory networks. The continued development of advanced genomic technologies and computational models promises to further refine our understanding of how Hox genes orchestrate the complex process of limb formation.

The three-dimensional organization of the genome is a fundamental regulator of nuclear processes, directly controlling gene activation, repression, and cellular identity [40]. In the context of limb development and regeneration, physical interactions between genes and their regulatory elements are particularly crucial for orchestrating complex spatiotemporal expression patterns. Techniques based on Chromatin Conformation Capture (3C) have revolutionized our ability to map these interactions, revealing that enhancers often contact target promoters over considerable genomic distances—sometimes hundreds of kilobases—bypassing nearby genes to regulate specific targets [41]. For researchers studying Hox gene networks in limb research, understanding these architectural principles provides essential insights into how these key developmental regulators are controlled.

The following table summarizes the primary functions of key genome organization features relevant to gene regulation:

Table 1: Key Features of 3D Genome Organization

| Feature | Description | Functional Role in Gene Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Compartments | Large-scale A (active) and B (inactive) chromatin compartments | Segregates transcriptionally active and inactive regions |

| Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) | Self-interacting genomic regions (hundreds of Kb to Mb) | Constrains enhancer-promoter interactions within defined boundaries |

| Chromatin Loops | Specific contacts between distal regulatory elements and promoters | Enables precise spatial organization for transcriptional control |

| Enhancer-Promoter Interactions | Physical contacts between enhancers and their target gene promoters | Directly activates or enhances transcription of target genes |

3C Technology Landscape: From Locus-Specific to Genome-Wide Methods

The Chromatin Conformation Capture (3C) technology family has evolved significantly since its inception, offering researchers a range of tools to investigate genome architecture at different resolutions and scales. The core methodology shared across these techniques involves formaldehyde crosslinking to preserve native chromatin interactions, enzymatic digestion of DNA, proximity ligation of crosslinked fragments, and high-throughput sequencing to identify interacting loci [41] [40].

Table 2: Overview of Chromatin Conformation Capture Technologies

| Technology | Year | Applicability | Resolution | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3C | 2002 | Locus-specific | Locus-level | Simple; ideal for validating specific interactions | Cannot capture genome-wide interactions |

| 4C | 2006 | Locus-to-genome | ~10-100 kb | Discovers all interactions with a specific bait locus | Limited to one locus at a time |

| Hi-C | 2009 | Genome-wide | ~1-10 Mb | Unbiased genome-wide interaction mapping | High cost; complex data analysis |

| Capture Hi-C | 2015 | Targeted genome-wide | kb to sub-kb | Cost-effective targeting of important regions (e.g., promoters) | Requires probe design; less unbiased |

| Micro-C | 2015 | Genome-wide | Nucleosome-level | Ultra-high resolution (nucleosome level) | Very expensive; data heavy |

| Single-cell Hi-C | 2013 | Genome-wide (single-cell) | ~100 kb-1 Mb | Resolves cell-to-cell heterogeneity in chromatin structure | Sparse data, low throughput |

Application to Hox Gene Regulation in Limb Development

In limb research, Hox genes exhibit complex expression patterns along both anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes, regulated through intricate genomic architectures. Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses of mouse limb buds revealed a developmental transition from anterior-posterior to proximal-distal patterning between E10.5 and E11.5 [42]. During this critical period, Hox gene regulation shifts from being controlled by early/proximal regulatory landscapes to late/distal landscapes, with Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 (Hox13) emerging as key determinants of proximal-distal patterning [42].

The functional importance of Hox genes in limb formation extends to regeneration contexts. In Xenopus limb regeneration, hoxc12 and hoxc13 demonstrate the highest regeneration specificity in expression profiles, acting as key regulators for rebooting the developmental program during morphogenesis phases after initial wound response [43]. Loss-of-function experiments showed that knocking out either gene inhibited cell proliferation and expression of developmentally essential genes, resulting in autopod regeneration failure, while limb development itself remained unaffected [43].

Human embryonic limb atlases resolved through single-cell and spatial transcriptomics have further illuminated the spatial organization of HOX gene expression. These studies demonstrate anatomical segregation of gene expression patterns linked to limb malformations, with transcriptionally distinct mesenchymal populations in the autopod expressing specific HOX signatures [44].

Detailed Methodologies: Promoter Capture Hi-C for Hox Gene Research

Experimental Workflow for Promoter Capture Hi-C

Promoter Capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) represents a powerful derivative of Hi-C that specifically enriches for promoter-containing ligation products, enabling high-resolution mapping of promoter-interacting regions (PIRs) across the entire genome [41]. This method is particularly valuable for Hox research as it allows systematic identification of distal regulatory elements contacting Hox gene promoters.

Cell Fixation and Crosslinking

- Begin with a minimum of 2 × 10^7 cells per experiment [41]