Definitive Validation of Transgenic Reporter Lines for Embryonic Expression: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of transgenic reporter lines for embryonic expression studies.

Definitive Validation of Transgenic Reporter Lines for Embryonic Expression: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

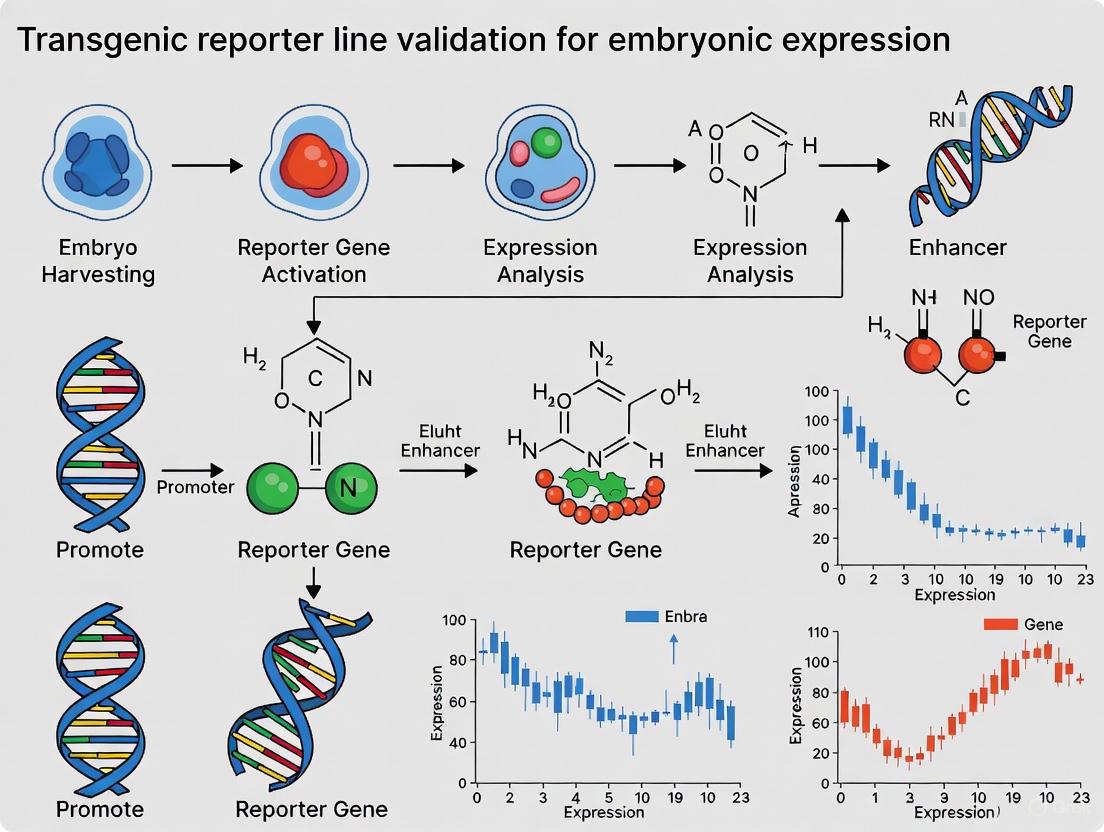

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of transgenic reporter lines for embryonic expression studies. It covers foundational principles of reporter gene biology and regulatory element selection, explores advanced methodologies including CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted integration and novel lineage tracing systems, addresses critical troubleshooting for issues like positional effects and silencing, and establishes robust validation frameworks from cellular to organismal levels. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource aims to enhance the precision, reliability, and reproducibility of embryonic research utilizing transgenic reporters across model organisms.

Core Principles of Transgenic Reporter Systems in Embryonic Development

Reporter genes are genetically encoded elements that produce a detectable signal, allowing researchers to non-invasively visualize and measure biological processes that are otherwise not visible [1]. These powerful tools have revolutionized practically all fields of biological research, from fundamental microbiology to preclinical studies in higher eukaryotes [1]. By linking the expression of easily detectable reporter proteins to specific genetic regulatory elements, scientists can monitor gene expression patterns, track cell fate, study signaling pathway activation, and validate therapeutic efficacy in real-time.

The fundamental principle underlying reporter gene technology involves fusing the regulatory DNA sequence of interest (such as a promoter or enhancer) to a gene encoding a protein that can produce a measurable signal. When the regulatory sequence is activated, it drives expression of the reporter gene, generating a quantifiable output that reflects the biological activity being studied [2] [3]. This experimental approach provides invaluable insights into cellular mechanisms while enabling longitudinal analyses within the same subject or cell population.

Within the context of transgenic reporter line validation for embryonic expression research, selecting the appropriate reporter system is paramount. The choice between fluorescent proteins like GFP and enzymatic reporters like luciferase involves careful consideration of signal stability, detection sensitivity, spatial resolution, and experimental requirements for substrate administration. This guide provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparison of these fundamental tools to inform researchers' experimental design decisions.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signal Generation

Fluorescent Proteins: Illumination Through Light Absorption

Fluorescent proteins, with Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) as the most prominent representative, function through the principle of fluorescence. These proteins absorb light at a specific wavelength and then emit lower-energy light at a longer wavelength [4]. The molecular mechanism involves the formation of a chromophore within a barrel-shaped protein structure through autocatalytic post-translational modification. When exposed to light of the appropriate excitation wavelength, electrons in the chromophore become excited to higher energy states; as they return to ground state, they release energy as photons of visible light.

The engineering of fluorescent proteins has produced a broad palette of spectrally distinguishable variants, enabling multiparametric imaging of multiple biological processes simultaneously [1]. Modern variants offer improved brightness, photostability, and expression characteristics across diverse biological systems. For embryonic expression research, this color diversity allows for fate mapping of different cell lineages within the same developing organism.

Luciferases: Bioluminescence Through Enzymatic Reaction

Luciferase systems generate light through fundamentally different mechanisms. These enzymes catalyze the oxidation of a substrate molecule (luciferin), converting chemical energy directly into photon emission [4]. Unlike fluorescence, bioluminescence does not require initial light excitation, which eliminates problems associated with autofluorescence and photobleaching [5]. The firefly luciferase reaction requires luciferin, oxygen, and ATP, producing light at approximately 560 nm [5].

Different luciferase systems have been characterized, including bacterial luciferase (which autonomously synthesizes its substrate through luxCDE genes) [5] and the increasingly popular NanoLuc luciferase, which offers smaller size and brighter output. The enzymatic nature of luciferase systems provides exceptional signal-to-noise ratios, as mammalian tissues produce virtually no endogenous bioluminescence. However, this comes with the requirement of administering the substrate (luciferin) either to cell culture media or via injection in live animal studies [4].

Figure 1: Molecular mechanisms of fluorescent proteins versus luciferase systems. Fluorescent proteins require light excitation, while luciferases generate light through enzymatic oxidation of substrate.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in the performance characteristics of fluorescent and bioluminescent reporter systems. These technical distinctions directly influence their suitability for specific applications in embryonic expression research and transgenic line validation.

Signal Intensity and Stability

Head-to-head comparisons of GFP and luciferase imaging in vivo demonstrate that GFP provides approximately twice the initial signal intensity of luciferase (55,909 intensity units versus 28,065 intensity units at initial measurement) [6]. More significantly, GFP signals remain stable over time, showing minimal change over 20 minutes of continuous imaging. In contrast, luciferase signals decrease rapidly following substrate administration, dropping by approximately 80% between 10 and 20 minutes post-luciferin injection due to substrate clearance [6]. This temporal stability makes fluorescent proteins preferable for extended imaging sessions and quantitative time-course studies.

Detection Sensitivity and Temporal Resolution

The photon generation efficiency of these systems differs substantially, directly impacting detection sensitivity and imaging speed. GFP imaging requires only 100 milliseconds exposure time to detect robust signals, while luciferase imaging necessitates 30-second exposures—a 300-fold difference that enables real-time imaging with fluorescent reporters but not with bioluminescent systems [6]. However, luciferase systems typically achieve better signal-to-noise ratios in deep tissues due to the absence of background autofluorescence [5]. The minimal detectable cell numbers for each system depend on specific experimental conditions, with one study demonstrating similar detection thresholds for bacterial luciferase (lux) and firefly luciferase (luc) at approximately 2.5×10⁴ cells in subcutaneous implants [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Reporter Gene Systems

| Performance Parameter | GFP/Fluorescent Proteins | Firefly Luciferase | Bacterial Luciferase (lux) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Intensity | 55,909 intensity units (initial) [6] | 28,065 intensity units (at 10 min) [6] | Reduced vs. firefly luciferase [5] |

| Signal Stability | Stable over 20 min (<1% change) [6] | Decreases ~80% from 10 to 20 min [6] | Maintains constant level [5] |

| Exposure Time | 100 ms [6] | 30 s [6] | 10 min for in vitro imaging [5] |

| Background Issues | Autofluorescence, light scattering [4] | Minimal background [5] | Minimal background [5] |

| Substrate Requirement | None | Exogenous luciferin required [4] | Autonomous substrate synthesis [5] |

| Temporal Resolution | Excellent (real-time capability) | Limited (slow signal acquisition) | Limited (slow signal acquisition) |

Technical Considerations for Embryonic Research

For embryonic expression research, additional practical considerations influence reporter selection. The autonomous nature of fluorescent proteins enables continuous monitoring of dynamic developmental processes without experimental interruption. However, light scattering and absorption in thick tissues can limit detection efficiency [4]. Luciferase systems overcome some tissue penetration limitations but require potentially disruptive substrate administration. The bacterial lux system offers complete autonomy but currently provides lower signal output compared to optimized firefly luciferase variants [5]. Transgenic line validation requires special attention to potential positional effects and expression fidelity, which can be mitigated through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted integration into defined genomic safe harbor loci [2] [1].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Standardized Protocols for Comparative Studies

To ensure valid comparisons between reporter systems, researchers must implement standardized experimental protocols. For in vitro assessments, cells are typically transfected with reporter constructs, harvested, and serially diluted in multi-well plates for detection limit determinations [5]. Viable cell counts should be determined using a hemocytometer, with background correction applied using untransfected control cells.

For in vivo imaging studies, including embryonic research, animal preparation must be carefully controlled. Studies typically utilize nude mice (6-8 weeks old) implanted with reporter-expressing cells [6]. For luciferase imaging, D-luciferin potassium salt is administered intravenously (150 mg/kg) with imaging commencing immediately post-injection [6]. GFP imaging requires no substrate but depends on optimized excitation (487 nm) and emission detection (513 nm) parameters [6]. Consistent anesthesia, positioning, and environmental controls are essential for quantitative comparisons.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for comparative reporter gene validation. The protocol encompasses cell preparation through in vitro and in vivo assessment to data analysis.

Transgenic Line Validation Approaches

Validating transgenic reporter lines for embryonic expression research requires specialized methodologies to ensure faithful representation of endogenous gene expression patterns. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing now enables precise insertion of reporter cassettes into specific genomic loci, minimizing positional effects that can compromise expression fidelity [2] [3]. For temporal control of reporter expression, tetracycline-inducible systems offer low leakiness and good fold induction when activated [1].

For definitive validation, researchers should employ complementary techniques including:

- Primary validation: Comparison of reporter signal with endogenous gene expression via in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry in embryonic tissues.

- Spatial fidelity assessment: Whole-mount imaging of cleared embryos using techniques like CLARITY or iDISCO to verify anatomical precision of reporter expression [1].

- Temporal validation: Time-course analyses comparing reporter activation with known developmental milestones.

- Transgene mapping: Methods like TransTag for identifying transgene insertion sites in zebrafish models [7], with analogous approaches applicable to mammalian systems.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Reporter Gene Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Vectors | pGL4[luc2], pCDNA3.1-CT-GFP, pLuxCDEfrp | Plasmid constructs for introducing reporter genes into cells | Promega, Thermo Fisher [5] |

| Detection Kits | Luciferase Assay Systems, Ready-to-Use GFP | Commercial kits providing optimized reagents for signal detection | Promega, Thermo Fisher, PerkinElmer [8] |

| Imaging Substrates | D-luciferin potassium salt | Essential substrate for luciferase-based bioluminescence imaging | Gold Biotechnology, PerkinElmer [6] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Lipofectamine 2000, Selective antibiotics | Transfection and maintenance of reporter cell lines | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen [5] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Targeted integration of reporter cassettes into specific genomic loci | Multiple providers [2] [3] |

| In Vivo Imaging Systems | IVIS Lumina, BioSpectrum Advanced | Instrumentation for detecting and quantifying reporter signals in living systems | PerkinElmer, Analytik Jena [5] [6] |

Application-Specific Recommendations

Guidance for Embryonic Expression Research

For transgenic reporter line validation in embryonic research, the optimal reporter system depends on specific experimental priorities. Fluorescent proteins (particularly GFP and its variants) are recommended when:

- Real-time imaging of dynamic developmental processes is required

- High spatial resolution at cellular level is essential

- Multiplexing with multiple reporters is needed

- Minimizing experimental disruption to embryos is prioritized

- Longitudinal studies without repeated substrate administration are planned

Luciferase systems (particularly firefly luciferase) are preferable when:

- Maximizing detection sensitivity in deep tissues is critical

- Quantitative assessment of transcriptional activity is the primary goal

- Background autofluorescence compromises fluorescent detection

- Three-dimensional reconstruction of expression patterns is needed

- Photobleaching during extended imaging is a concern

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The reporter gene field continues to evolve with emerging technologies that enhance their utility for developmental biology research. Hybrid BRET-FRET systems combine bioluminescence and fluorescence resonance energy transfer, enabling more sophisticated biosensor designs [3]. Microfluidics-integrated reporter assays permit high-throughput screening of transcriptional responses in miniature formats [3]. Dual-reporter systems incorporating spectrally distinct enzymes that metabolize the same substrate provide internal controls for normalizing functional signals against potential confounding factors [1].

For embryonic research specifically, continued development of bright, far-red fluorescent proteins and autonomously bioluminescent systems (e.g., improved lux constructs) will address current limitations in tissue penetration and substrate requirements. Coupled with advances in tissue clearing methods and light-sheet microscopy, these technological innovations will further solidify the central role of reporter genes in understanding developmental biology.

In embryonic expression research and transgenic reporter line validation, the selection of regulatory elements is not merely a technical choice but a fundamental determinant of experimental success. These DNA sequences, which include promoters and enhancers, function as genetic switches that precisely control where, when, and to what extent a gene is expressed [9]. In the context of transgenic reporter lines, this translates directly to the specificity, intensity, and reliability of the expression pattern being studied. The fundamental principle governing these elements is that they act in cis, meaning they regulate genes on the same chromosome, and their effect is independent of orientation and distance from the target gene, though they can function over considerable genomic distances [9].

The three primary classes of promoters—constitutive, tissue-specific, and inducible—offer distinct experimental advantages and limitations. Constitutive promoters provide steady, ubiquitous expression across most tissues and developmental stages, making them invaluable for widespread labeling or when consistent expression is required regardless of cellular context [10]. In contrast, tissue-specific promoters restrict expression to particular cell types or organs, enabling precise targeting of reporter genes to specific populations of interest within the complex architecture of the embryo [10]. Finally, inducible promoters allow researchers to control the timing of gene expression through external stimuli, providing temporal precision that is often crucial for studying dynamic developmental processes [11]. The strategic selection among these options forms the cornerstone of valid and interpretable experimental design in developmental biology.

Classification and Characteristics of Promoters

Core Architectural Components

All promoters share a common modular architecture consisting of several key regions. The core promoter, which includes the transcription start site (TSS), serves as the docking platform for RNA polymerase II and the general transcription machinery [12]. Critical core elements include the TATA box, initiator (Inr), and downstream promoter elements (DPEs) [12]. Immediately upstream lies the proximal promoter, which contains multiple transcription factor binding sites that provide additional layers of regulation [12]. Beyond this, distal regulatory elements such as enhancers, silencers, and insulators can exert influence over vast genomic distances—up to hundreds of kilobases—through chromatin looping mechanisms that bring these elements into physical proximity with their target promoters [9] [12].

Table 1: Core Components of Eukaryotic Promoters

| Component | Location Relative to TSS | Key Elements | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Promoter | -35 to +35 | TATA box, Inr, DPEs | Assembly of pre-initiation complex (PIC) and transcription start |

| Proximal Promoter | -250 to -50 | Clustered TF binding sites | Fine-tuning expression levels through activator/repressor binding |

| Distal Regulatory Elements | Up to 1 Mb away | Enhancers, Silencers, Insulators | Major regulation of tissue-specificity, induction, and repression |

This architectural complexity enables sophisticated regulatory control, with enhancers playing a particularly crucial role in temporal and tissue-specific regulation during embryonic development [9]. The identification of these elements has been revolutionized by next-generation sequencing technologies, including ATAC-seq for mapping open chromatin, ChIP-seq for transcription factor binding sites, and various chromosome conformation capture methods (3C, 4C, Hi-C) for unraveling the three-dimensional interactions that govern gene expression [9].

Constitutive Promoters

Constitutive promoters drive consistent, relatively uniform gene expression across most tissues and developmental stages, making them ideal for applications requiring ubiquitous reporter expression [10]. In plant systems, widely used constitutive promoters include the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S (CaMV 35S) promoter and the nopaline synthase (Nos) promoter from Agrobacterium tumefaciens [10]. However, in monocotyledonous plants like rice, the CaMV 35S promoter exhibits reduced activity, leading to a preference for endogenous plant promoters such as the OsAct1 (actin) and OsUbi1 (ubiquitin) promoters, which demonstrate high efficiency across all rice tissues [10].

While constitutive promoters offer the advantage of strong, widespread expression, they present significant limitations for embryonic research. Their non-specific activity can lead to the expression of reporter genes in non-target tissues, creating background interference and complicating data interpretation [10]. More critically, the constant production of foreign proteins or metabolites can disrupt normal metabolic balance, potentially causing growth retardation, developmental abnormalities, or even embryonic lethality, thereby confounding phenotypic analysis [10]. These limitations have prompted increased adoption of more precise regulatory elements for developmental studies.

Tissue-Specific Promoters

Tissue-specific promoters enable precise spatial control of gene expression, activating transcription only in particular cell types, organs, or at specific developmental stages [10]. This precision is invaluable in embryonic research, where understanding cell lineage specification and tissue patterning requires genetic tools that mirror endogenous expression patterns. In rice, for example, root-specific promoters like those driving expression of the OsIRT1 (iron-regulated transporter) and OsHMA3 (heavy metal transporter) genes restrict expression to root tissues, where these genes facilitate nutrient and metal ion uptake from the soil environment [10].

The fundamental advantage of tissue-specific promoters lies in their ability to limit reporter expression to defined cellular contexts, thereby reducing metabolic burden and potential pleiotropic effects in non-target tissues [10]. This specificity is particularly crucial when expressing potentially cytotoxic reporter proteins or when manipulating gene function in a subset of cells within a complex embryonic structure. From a practical standpoint, the use of tissue-specific promoters enhances signal-to-noise ratio in imaging applications and allows for precise lineage tracing and functional analysis within developing tissues.

Inducible Promoters

Inducible promoters provide temporal control over gene expression, activating transcription only in response to specific external stimuli, chemical inducers, or environmental cues [11]. Common inducing signals include hormones like abscisic acid (ABA), chemicals such as ethanol or tetracycline, or environmental stresses including salinity, drought, or temperature shifts [11]. A prime example is a synthetically designed salt-inducible promoter that demonstrated a five-fold increase in reporter expression under salt stress compared to constitutive promoters in transgenic Arabidopsis [11].

The principal strength of inducible systems is their capacity to separate the timing of transgene activation from the developmental process under investigation. This enables researchers to bypass potential embryonic lethality caused by early constitutive expression and to interrog gene function during specific developmental windows. Furthermore, inducible systems facilitate the study of direct versus indirect effects in genetic pathways, as the immediate consequences of gene activation can be observed without compensatory mechanisms that might develop over time. However, potential limitations include incomplete induction, leaky basal expression, and unintended pleiotropic effects of the inducing agent itself on developmental processes.

Quantitative Comparison of Promoter Performance

Experimental Data from Transgenic Systems

Rigorous quantification of promoter performance is essential for selecting appropriate regulatory elements for specific research applications. Experimental data from both plant and animal systems reveal significant differences in expression levels, induction ratios, and tissue specificity across promoter classes.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Promoter Performance in Transgenic Systems

| Promoter Type | Representative Examples | Expression Level | Induction Ratio | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutive | CaMV 35S, OsAct1, OsUbi1 | High (all tissues) | Not applicable | Stable, ubiquitous expression; potential for metabolic burden |

| Tissue-Specific | OsIRT1, OsHMA3 | Variable (specific tissues) | Not applicable | Spatial precision; reduced pleiotropic effects |

| Inducible (Synthetic) | PS (Salt-inducible) | Moderate to High (after induction) | 5-fold (salt), 2-fold (drought/ABA) | Temporal control; minimal basal expression |

In animal models, systematic validation of transgenic lines labeling specific neuronal populations demonstrates how promoter selection dictates cellular targeting precision. For example, in larval zebrafish, transgenic lines utilizing the nefma and adcyap1b promoters label most or all reticulospinal neurons (RSNs), while the vsx2 and pcp4a promoters provide access to specific ipsilateral or contralateral RSN subpopulations, respectively [13]. This granularity in cellular targeting underscores the critical importance of matching promoter specificity to research questions in embryonic systems.

Methodologies for Promoter Validation

The validation of promoter activity and specificity relies on standardized experimental protocols that enable quantitative comparison across different regulatory elements. For inducible promoters, the following protocol adapted from salt-inducible promoter research provides a robust framework for characterization [11]:

Protocol 1: Validation of Inducible Promoter Activity

- Cloning: Insert the candidate promoter upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GUS, GFP) in an appropriate expression vector.

- Transformation: Introduce the construct into the target organism via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (plants) or microinjection (animals).

- Induction: Apply the specific inducer (e.g., 100 mM NaCl for salt-inducible promoters, 100μM ABA for ABA-responsive promoters) to experimental groups while maintaining control groups without induction.

- Sampling: Harvest tissue at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 12, 24, 48 hours post-induction) to capture induction kinetics.

- Quantification: Measure reporter activity fluorometrically (GUS: 365nm excitation/455nm emission) and normalize to total protein content.

- Analysis: Compare induced versus non-induced expression levels and calculate fold-induction ratios.

For tissue-specific promoters, validation typically involves comprehensive spatial mapping of reporter expression throughout development:

- Histological Analysis: Section tissues and stain for reporter activity to determine cellular resolution of expression.

- Time-Course Monitoring: Track expression patterns across multiple developmental stages.

- Quantitative Comparison: Compare reporter expression levels across different tissues to calculate specificity ratios.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for inducible promoter validation, showing parallel treatment groups and quantitative analysis.

Advanced Applications: Synthetic Biology Approaches

Engineering Synthetic Promoters

When natural promoters lack the desired specificity, strength, or inducibility, synthetic biology approaches offer powerful alternatives through the rational design of artificial regulatory elements. Synthetic promoters are constructed by combining core promoter elements with specific arrangements of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) that respond to particular transcription factors [14]. These engineered systems provide several advantages over their natural counterparts, including reduced sequence homology to prevent gene silencing, precise control over expression levels, and the ability to incorporate multiple regulatory inputs [11].

Multiple molecular techniques exist for synthetic promoter generation, each with distinct applications and outcomes. The hybridization approach involves linking key motifs from different promoters to create novel composites, while site-directed mutagenesis introduces specific mutations to add or remove CREs [14]. DNA shuffling recombines fragments from multiple promoters to generate diverse libraries, and linker-scanning mutagenesis replaces native promoter segments with synthetic sequences containing designed clusters of point mutations [14]. These methods have produced synthetic promoters with tailored properties, such as a 454bp salt-inducible synthetic promoter that drove a five-fold increase in reporter expression under stress conditions [11].

Genomic Safe Harbors for Transgene Integration

Beyond promoter engineering, the genomic location of transgene integration significantly influences expression stability and level. The concept of "genomic safe harbors" (GSHs) has emerged as a critical consideration for reliable transgene expression, particularly in embryonic research where positional effects can confound results [15]. GSHs are defined genomic loci that permit predictable, stable transgene expression without disrupting endogenous gene function or inducing malignant transformation [15].

Two well-characterized GSH platforms include the H11 locus, located in an intergenic region with an open chromatin structure that supports high-efficiency transgene expression, and the Rosa26 locus, which utilizes endogenous non-coding RNA promoters for ubiquitous expression across tissues [15]. Multi-dimensional validation of these platforms in goat models demonstrated stable EGFP expression at cellular, embryonic, and individual levels, with no disruption to adjacent genes or normal development [15]. When designing transgenic reporter lines, combining optimized promoters with targeted integration into validated GSHs represents a robust strategy for minimizing position effects and achieving reproducible expression patterns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Promoter Analysis and Transgenesis

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| pBI121 Vector | Plant Binary Vector | Reporter gene cloning | Contains GUS reporter; used for promoter-reporter fusions |

| CaMV 35S Promoter | Constitutive Promoter | Positive control for transformation | Strong, ubiquitous expression in plants |

| OsAct1/Ubi Promoters | Constitutive Promoter | Driving transgene expression in monocots | High efficiency in rice and other cereals |

| H11 Targeting System | Genomic Safe Harbor | Precise transgene integration | Open chromatin structure; high expression |

| Rosa26 Platform | Genomic Safe Harbor | Ubiquitous transgene expression | Endogenous non-coding RNA promoter |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Gene Editing | Targeted integration; promoter modification | Creates DSBs for HDR-mediated knock-in |

| enhancer AAVs | Viral Vector | Cell-type-specific targeting in nervous system | >1,000 vectors for cortical cell populations |

| PlantCARE/PLACE | Bioinformatics Database | CRE identification in plant promoters | Curated databases of regulatory elements |

Figure 2: Decision pathway for selecting and implementing regulatory elements in transgenic experiments.

The strategic selection of regulatory elements represents a critical decision point in the design of transgenic reporter lines for embryonic expression research. Constitutive, tissue-specific, and inducible promoters each offer distinct advantages that must be aligned with experimental goals, whether the priority is comprehensive labeling, cellular resolution, or temporal control. Quantitative comparisons demonstrate that synthetic promoters can outperform their natural counterparts in both strength and specificity, while genomic safe harbor platforms address the persistent challenge of integration position effects.

For researchers embarking on transgenic reporter line validation, a systematic approach that matches promoter properties to biological questions, employs rigorous validation methodologies, and utilizes the expanding toolkit of synthetic biology resources will yield the most reliable and interpretable results. As the field advances, the integration of multi-omics data with computational design promises to further expand the repertoire of precision regulatory elements, ultimately enhancing our ability to dissect the complex regulatory networks that orchestrate embryonic development.

The selection of an appropriate embryonic model system is a critical first step in the validation of transgenic reporter lines, with implications for the study of gene regulation, disease mechanisms, and drug development. Zebrafish, mouse, and stem cell-derived models each provide unique environments for assessing reporter construct activity, influenced by factors ranging from embryonic transparency to epigenetic landscapes. Each system presents a distinct balance of throughput, physiological relevance, and technical feasibility. This guide objectively compares the performance of these predominant models in transgenic reporter validation, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform selection criteria for research and development applications.

Model System Comparison

The following table provides a comparative overview of the key characteristics of zebrafish, mouse, and stem cell-derived models for transgenic reporter line validation.

| Feature | Zebrafish | Mouse | Stem Cell-Derived Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo/In Vitro Nature | In vivo vertebrate | In vivo mammal | In vitro (can be differentiated into various cell types) |

| Embryonic Transparency | High (enables live imaging) [16] [17] | Low (requires fixation and sectioning) | High for 2D cultures (live imaging possible) |

| Development & Screening Speed | Rapid (external fertilization, fast organogenesis) [17] | Slow (gestation period, in utero development) | Rapid (differentiation protocols over days/weeks) |

| Throughput Potential | High (hundreds of embryos per clutch) [17] [18] | Low (small litter sizes, high maintenance costs) | Very High (amenable to 96-well plate formats) |

| Physiological Relevance | High for vertebrate development and disease modeling [16] [17] | High for mammalian physiology and human disease | Context-dependent (requires validation for tissue-specific function) |

| Genetic Manipulation Efficiency | High (e.g., Tol2 transposon, CRISPR) [17] | Established but lower throughput (e.g., pronuclear injection, ES cell targeting) | High (lentiviral transduction, CRISPR in iPSCs) [19] |

| Primary Challenge | Non-mammalian physiology | Low throughput, high cost, opaque embryos | Epigenetic silencing of transgenes, recapitulation of tissue maturity [19] |

Experimental Data and Validation

Transgene Performance Across Models

Quantitative data on reporter expression and efficiency is crucial for model selection. The table below summarizes key performance metrics as demonstrated in recent studies.

| Model & Specific System | Reporter Construct/Line | Key Performance Data | Experimental Application/Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | Tg(Dusp6:d2EGFP)pt6 (FGF signaling reporter) |

Faithfully reports FGF activity in known signaling centers (e.g., mid-hindbrain boundary). Expression suppressed by FGFR inhibitors [18]. | In vivo visualization of dynamic FGF signaling during development; chemical screening [18]. |

| Zebrafish | Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4 (Wnt signaling reporter) |

More sensitive and specific for Wnt signaling compared to earlier TOPdGFP reporter lines [17]. |

Monitoring Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity in real-time during embryogenesis [17]. |

| Mouse ESCs | Nd (Nanog:VNP) BAC transgene reporter |

Accurately reflects dynamic fluctuations of endogenous Nanog expression; ~55% of cells Nanog+ in standard culture [20]. | Studying pluripotency network dynamics and heterogeneity in stem cell populations [20]. |

| Human iPSCs | Lentiviral EFSp-EGFP |

Drives relatively higher transgene expression vs. CMV, SFFV, MND promoters due to lower CpG island content and reduced methylation [19]. | Benchmarking promoter efficacy; miniUCOE-SFFVp-EGFP showed anti-silencing effect [19]. |

| Mouse Transgenic Assay | enSERT safe-harbor integration | Provides rich, multi-tissue phenotype data for human enhancer sequences in an organismal context [21]. | Functional validation of human neuronal enhancers and non-coding variants identified in MPRA screens [21]. |

Complementary Nature of Assays

Massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) conducted in stem cell-derived neurons and mouse transgenic assays provide correlated and complementary information. A 2025 study testing over 50,000 sequences for neuronal enhancer activity found a strong and specific correlation between MPRA results in human neurons and enhancer activity in mouse embryos. Furthermore, four out of five variants with significant effects in the MPRA also affected neuronal enhancer activity in vivo. The mouse assays added a layer of information by revealing pleiotropic variant effects across different tissues, which could not be captured in the cell-based MPRA [21]. This demonstrates the power of combining high-throughput pre-screening in stem cell models with phenotypic validation in whole organisms.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Signaling Pathway Reporter Zebrafish

Principle: This protocol uses the Tol2 transposon system to create stable transgenic zebrafish lines expressing fluorescent reporters under the control of signaling-responsive elements (e.g., for BMP, Wnt, FGF), enabling live imaging of pathway activity during development [17] [18].

Key Steps:

- Vector Design: Clone multimerized copies (e.g., 7x for Wnt) of the transcription factor binding site (e.g., TCF/LEF for Wnt) upstream of a minimal promoter and a fluorescent protein gene (e.g., GFP, mCherry) in a Tol2 donor plasmid [17].

- One-Cell Stage Embryo Injection: Co-inject the purified Tol2 donor plasmid construct with in vitro synthesized transposase mRNA into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos [17].

- Founder Identification: Raise injected embryos (F0). At maturity, outcross them to wild-type fish and screen their F1 offspring for fluorescence expression to identify germline-transmitting founders.

- Stable Line Establishment: Raise multiple fluorescent F1 offspring to establish stable, homozygous transgenic lines. Validate reporter specificity by confirming that fluorescence patterns change as expected upon genetic or chemical activation/inhibition of the pathway [18].

Protocol 2: Validating Cis-Regulatory Elements in Stem Cell-Derived Neurons

Principle: This protocol uses lentiviral transduction to introduce reporter constructs into human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) and their neuronal derivatives, providing a platform to test putative enhancers or promoters while addressing stem cell-specific epigenetic silencing [19] [21].

Key Steps:

- Reporter Library Construction: Clone candidate regulatory sequences (e.g., 270 bp tiles from ATAC-seq peaks) into a lentiviral MPRA vector upstream of a minimal promoter and a reporter gene. Each sequence is associated with a unique DNA barcode for quantification [21].

- Lentiviral Production: Co-transfect the reporter library plasmid with packaging plasmids (e.g., pMDL.g, pRSV-rev, pMD2.G) into HEK293T cells using polyethylenimine (PEI). Harvest and concentrate viral particles from the culture medium [19] [21].

- Cell Transduction and Differentiation: Transduce the lentiviral library into human iPSCs. Select for stably transduced cells if necessary. Differentiate the iPSCs into excitatory neurons using an established protocol (e.g., via Ngn2 induction) [21].

- MPRA Readout by Sequencing: After differentiation, extract genomic DNA (gDNA) and total RNA from the neurons. Use the gDNA to catalog the integrated library (input). From the RNA, generate cDNA to measure the transcribed barcodes (output). The reporter activity for each element is calculated as the ratio of its RNA barcode counts to DNA barcode counts [21].

- Anti-Silencing Strategies: To combat promoter methylation and silencing in iPSCs, utilize promoters with low CpG content (e.g., EFS) or incorporate chromatin opening elements (e.g., miniUCOE) upstream of the promoter in the vector design [19].

Signaling Pathways in Reporter Assays

Reporter lines are extensively used to visualize the activity of key developmental signaling pathways. The core logic involves a ligand binding to a receptor, which triggers an intracellular cascade leading to the nuclear translocation of pathway-specific transcription factors. These factors then bind to specific DNA sequences (cis-elements), activating the transcription of a reporter gene like GFP.

Examples from Research:

- Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: The

Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4zebrafish line uses multimerized TCF/Lef binding sites to monitor Wnt signaling activity [17]. - FGF/ERK Pathway: The

Tg(Dusp6:d2EGFP)pt6zebrafish line uses the promoter ofdusp6, a direct target of FGF signaling, to report on pathway activity [18]. - Nodal/TGF-β Pathway: A transgenic zebrafish line expressing a GFP-Smad2 fusion protein allows visualization of Nodal signaling by tracking the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the transcription factor [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tol2 Transposon System | Stable genomic integration of transgenes in zebrafish. | High efficiency (~70% germline transmission). Used for generating stable zebrafish reporter lines like Tg(Dusp6:d2EGFP)pt6 [17] [18]. |

| I-SceI Meganuclease | Facilitates genomic integration of foreign DNA. | An alternative method for zebrafish transgenesis, used in the initial generation of the Tg(Dusp6:d2EGFP)pt6 line [18]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Efficient delivery and stable integration of transgenes into mammalian cells, including iPSCs. | Enables high-throughput screening in stem cell models (e.g., MPRA in human neurons) [21]. |

| Ubiquitous Chromatin Opening Element (UCOE) | Prevents epigenetic silencing of transgenes. | miniUCOE placed upstream of a promoter (e.g., SFFV) inhibits CpG methylation and enhances sustained expression in iPSCs [19]. |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) | Carries large genomic regions for transgenesis. | Preserves native gene regulatory elements. Used to create the Nanog:VNP reporter mouse ES cell line, ensuring accurate expression [20]. |

| Destabilized Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., d2EGFP) | Reports on dynamic or recent gene expression. | Short protein half-life (e.g., 2 hours) allows monitoring of rapid changes in signaling activity, as in the FGF reporter zebrafish [18]. |

Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Reporter Expression

This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of various reporter systems and regulatory strategies used in embryonic expression research. The validation of transgenic reporter lines is a critical step, and researchers often must choose between rapid, high-throughput screening methods and rich, organismal-level phenotypic data. Based on current literature, no single assay provides a complete picture; instead, a complementary approach that leverages the strengths of multiple technologies is most effective. The following sections summarize quantitative performance data, detail key experimental protocols, and provide a toolkit of research reagents to inform the design and validation of reporter lines for developmental biology and drug discovery.

Validating transgenic reporter lines for embryonic expression research requires demonstrating that the reporter activity accurately recapitulates the expression pattern of the endogenous gene or regulatory element of interest. A significant challenge in the field is bridging the gap between high-throughput in vitro screening and phenotypically rich in vivo validation. Massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) offer the throughput necessary to screen thousands of sequences and variants, whereas traditional mouse transgenic assays provide the organismal context to observe expression in the complex architecture of the developing embryo [21]. Recent studies show that these methods are not mutually exclusive but are strongly correlated and provide complementary information. For instance, a 2025 study found a strong and specific correlation between MPRA activity in human neurons and enhancer activity in mouse embryos, with four out of five variants showing significant MPRA effects also affecting neuronal enhancer activity in vivo [21]. This guide frames the comparison of reporter regulation within this essential validation pipeline.

Core Regulatory Mechanisms of Reporter Expression

Reporter transgene expression can be manipulated at multiple levels to generate diverse biological readouts. The two primary levels of control are transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation.

Transcriptional Regulation

At the transcriptional level, the choice of promoter is the foremost determinant of reporter expression. Promoters can be broadly classified into three categories:

- Constitutive Promoters: Derived from viral genes (e.g., CMV) or eukaryotic housekeeping genes (e.g., PGK, EF1α), these promoters are "always on" [1]. They are useful for tracking cell number and location but provide no information about cell state. A common challenge is that strong viral promoters can be subject to epigenetic silencing in certain cell types, such as embryonic stem cells [1].

- Tissue-Specific Promoters: These promoters, derived from specific endogenous genes (e.g., the astrocyte-specific Aldh1l1), restrict reporter expression to a particular cell type [1]. This is crucial for studying cell-type-specific functions in complex tissues like the brain or during embryonic development.

- Conditional/Inducible Promoters: These promoters are activated by a specific biological state (e.g., inflammation via NF-κB) or an external molecule, such as tetracycline (Tet-On/Off systems) [1]. They allow for temporal control over reporter expression.

A critical consideration when using any promoter is the "position effect," where the genomic integration site of the transgene influences its expression. This can be mitigated by using "safe-harbor" loci like ROSA26 for knock-in strategies or by using CRISPR/Cas9 for targeted integration into a defined locus [1].

Post-Transcriptional Regulation

Regulation after transcription provides another layer of control, often used to achieve higher specificity.

- Recombinase-Based Systems: The most widely used strategy involves placing a "STOP" cassette, flanked by recombinase recognition sites (e.g., loxP for Cre recombinase), between the promoter and the reporter coding sequence [1]. The STOP cassette prevents transcription of the reporter. Cell-type-specific expression of Cre recombinase excises the STOP cassette, allowing reporter expression only in that specific cell type and its progeny.

- Riboswitches and Aptamer-Based Sensors: These are synthetic RNA elements inserted into the 5' untranslated region (UTR) of the reporter mRNA. Upon binding a specific ligand (e.g., the explosive RDX), the RNA structure changes to permit translation, thereby acting as a sensor at the post-transcriptional level [22].

The diagram below illustrates these core regulatory mechanisms.

Performance Comparison of Reporter Genes and Assays

Selecting the optimal reporter gene is critical, as performance varies significantly based on the experimental context, including the use of complex biological fluids.

Quantitative Comparison of Reporter Genes

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of commonly used reporter genes, based on a systematic comparison study.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common Reporter Genes [23]

| Reporter Gene | Type | Inducibility | Sensitivity | Compatibility with Complex Body Fluids | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable Nano Luciferase (NLucP) | Luminescent (Intracellular) | High | High | Good | Fast kinetics, low background, low promoter leakiness | Requires cell lysis for optimal measurement |

| Firefly Luciferase (FFLuc) | Luminescent (Intracellular) | High | High | Good | Well-established, high signal intensity | Signal is ATP-dependent, pH-sensitive substrate |

| Stable Nano Luciferase (NLuc) | Luminescent (Intracellular) | High | High | Good | Very bright, ATP-independent | Potential for signal carry-over due to stability |

| Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) | Luminescent (Secreted) | High | High | Poor | Allows medium sampling, no lysis required | Signal interference and variability in serum/body fluids |

| Red Fluorescent Protein (tdTomato) | Fluorescent | Poor | Moderate | Good (Intracellular) | No substrate needed, enables microscopy | Slow kinetics, high background from autofluorescence |

Correlation Between High-Throughput andIn VivoAssays

A pivotal question in validation is how well high-throughput in vitro data predicts in vivo performance. A 2025 study directly addressed this by comparing Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs) in human neurons with mouse transgenic assays.

Table 2: Correlation between MPRA and Mouse Transgenic Assay Data [21]

| Assay Type | Throughput | Key Readouts | Strengths | Limitations | Correlation Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenti-MPRA (in vitro) | Very High (>>50,000 sequences) | Quantitative enhancer/variant activity (Z-score) | Quantitative, reproducible, high-throughput | Limited to specific cell type; misses tissue-level complexity and pleiotropic effects. | Strong and specific correlation observed. |

| Mouse Transgenic Assay (in vivo) | Low (Few constructs) | Spatial, tissue-specific enhancer activity in embryo | Provides rich, multi-tissue phenotype; reveals pleiotropic effects. | Resource-intensive, low-throughput, qualitative/low-resolution quantitative. | 4/5 variants with significant MPRA effects also showed neuronal effects in vivo. |

This study demonstrates that while MPRA can effectively prioritize variants for in vivo testing, the mouse transgenic assay remains indispensable for uncovering pleiotropic effects and validating activity in the full biological context [21].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Methodologies

Protocol: Massively Parallel Reporter Assay (MPRA) for Neuronal Enhancers

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating neuronal enhancer activity and variant effects [21].

- 1. Library Design: Design 270 bp tiles covering regions of interest (e.g., ATAC-seq peaks, conserved enhancer cores). Introduce variants, including disease-associated SNPs and synthetic mutations.

- 2. Oligo Synthesis and Cloning: Synthesize the oligo pool and clone it into a barcoded lentiMPRA vector via Golden Gate assembly.

- 3. Viral Packaging and Transduction: Package the lentiMPRA library into lentiviral particles. Transduce the virus into a relevant cell model (e.g., human excitatory neurons derived from WTC11-Ngn2 iPSCs) at a low MOI to ensure single integration events.

- 4. DNA/RNA Sequencing and QC: After a set period, extract genomic DNA (gDNA) and total RNA. Convert RNA to cDNA. Amplify barcodes from both gDNA (representing the input library) and cDNA (representing the transcribed output) for high-throughput sequencing.

- 5. Data Analysis: For each element, count the barcodes in the DNA and RNA libraries. Calculate the reporter activity as the log2 ratio of RNA counts to DNA counts. Normalize activities to scrambled negative controls and express as a Z-score. Elements with a significant Z-score (e.g., FDR < 0.05) are considered functional.

Protocol: Transgenic Mouse Enhancer Assay (enSERT)

This protocol describes the validation of human enhancer sequences in a mouse model, as used in the VISTA Enhancer Browser [21].

- 1. Construct Preparation: Clone the candidate human regulatory sequence (typically 500-2000 bp) into an enhancer trap vector upstream of a minimal promoter and a reporter gene (e.g., lacZ).

- 2. Zygote Injection and Transfer: Microinject the linearized construct into the pronucleus of fertilized mouse zygotes. Implant the viable zygotes into pseudopregnant foster females.

- 3. Embryo Harvesting and Staining: Harvest the resulting embryos at the desired developmental stage (e.g., E11.5). Fix the embryos and subject them to X-gal staining, which produces a blue precipitate in cells where the lacZ reporter is expressed.

- 4. Imaging and Analysis: Image the stained embryos whole-mount and/or as histological sections. Analyze the spatial expression pattern of the blue stain and compare it to known patterns of endogenous gene expression to determine if the human sequence drives expression in the correct biological context.

The workflow below integrates these two complementary methodologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table catalogs key reagents and tools essential for the design, testing, and validation of regulated reporter systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reporter Line Development and Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inducible Promoters | Transcriptional Regulation | Provides temporal control over reporter expression. | σ³² Heat Shock Promoter [22]; Tetracycline (Tet)-On/Off Systems [1] |

| Tissue-Specific Drivers | Transcriptional Regulation | Restricts reporter expression to specific cell lineages for functional study. | Aldh1l1 (astrocytes) [1]; Ptf1a (pancreas) [1]; Enhancer AAVs [24] |

| Recombinase Systems | Post-Transcriptional Regulation | Provides high specificity by excising a STOP cassette in a cell-type-specific manner. | Cre-loxP; FLP-FRT [1] |

| Reporter Gene Cell Lines | Assay System | Provides a stable, reproducible system for high-throughput screening of biologics or compounds. | CRISPR/Cas9-edited RGA cell lines [2] |

| Validated Reporter Mice | In Vivo Validation | Enables high-throughput testing of gene-editing delivery and efficiency in vivo. | GFP-on reporter mouse [25] [26]; Luciferase ABE-editable reporter mouse [26] |

| Foundation Models (AI) | In Silico Prediction | Accurately predicts gene expression and regulatory element activity from sequence, aiding in candidate prioritization. | GET (General Expression Transformer) model [27] |

The strategic combination of transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls allows for precise targeting of reporter expression in transgenic lines. The validation of these lines benefits from a multi-tiered approach: beginning with in silico prediction using foundation models like GET [27], moving to high-throughput functional screening with MPRAs [21], and culminating in definitive phenotypic validation in mouse transgenic assays [21]. The quantitative data presented in this guide underscores that while performance characteristics like sensitivity and dynamic range are important, the choice of reporter and validation assay must be tailored to the specific biological question. The continued development of sensitive luciferases like NLucP, advanced fluorescent proteins, and innovative in vivo reporter models provides researchers with a powerful and expanding toolkit for embryonic expression research.

Defining Validation Benchmarks for Embryonic Expression Studies

In the field of developmental biology, research utilizing transgenic reporter lines and stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs) has transformative potential for advancing our understanding of human development, infertility, congenital diseases, and early pregnancy loss [28] [29]. The usefulness of these models, however, fundamentally hinges on their molecular, cellular, and structural fidelity to their in vivo counterparts [28]. Without rigorous validation against appropriate biological standards, researchers risk drawing incorrect conclusions due to model-specific artifacts or misannotated cell lineages.

This guide establishes a framework for validating embryonic expression patterns within the broader context of transgenic reporter line and embryo model research. We objectively compare validation methodologies—from transcriptomic profiling to functional enhancer assays—and provide supporting experimental data to help researchers select appropriate benchmarks for their specific applications. The recommendations align with emerging international standards from organizations including the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), which emphasizes that all such research must have a clear scientific rationale, defined endpoints, and appropriate oversight mechanisms [29].

Establishing Transcriptomic Reference Benchmarks

The Integrated Embryo Transcriptomic Atlas

A fundamental approach to validation involves comparing expression patterns from transgenic models against comprehensive transcriptional references from human embryos. Recent efforts have created integrated single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) references spanning human development from zygote to gastrula stages (Carnegie stage 7) by harmonizing data from six published datasets [28].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of an Integrated Embryonic Transcriptomic Atlas

| Characteristic | Specification | Utility in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Coverage | Zygote to Carnegie Stage 7 gastrula (E16-19) | Provides continuous reference across critical developmental windows |

| Cell Count | 3,304 early human embryonic cells | Ensures sufficient statistical power for lineage identification |

| Technical Processing | Standardized mapping to GRCh38 using unified pipeline | Minimizes batch effects between integrated datasets |

| Lineage Resolution | Identifies ICM, TE, epiblast, hypoblast, amnion, primitive streak, mesoderm, definitive endoderm, and extraembryonic lineages | Enables precise assignment of cell identities in query datasets |

| Availability | Online early embryogenesis prediction tool with Shiny interfaces | Facilitates community access for benchmarking |

This integrated atlas enables researchers to project their own scRNA-seq data from embryo models or transgenic systems onto the reference using stabilized Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), where cell identities can be predicted based on transcriptional similarity [28]. This approach moves beyond reliance on limited lineage markers toward unbiased transcriptome comparison, effectively addressing the challenge that many co-developing lineages share common molecular markers.

Trajectory Inference and Regulatory Networks

Beyond static classification, the reference enables dynamic analyses through trajectory inference algorithms such as Slingshot, which reconstruct developmental pathways and pseudotemporal ordering of cells [28]. This analysis has identified hundreds of transcription factors showing modulated expression along epiblast (367 factors), hypoblast (326 factors), and trophectoderm (254 factors) trajectories, providing a roadmap for validating the developmental progression observed in model systems.

Complementary Single-Cell Regulatory Network Inference and Clustering (SCENIC) analysis captures the activity of key transcription factors driving lineage specification, including:

- DUXA: High expression during morula stages, decreasing across all lineages

- VENTX: Enriched in epiblast populations

- OVOL2: Active in trophectoderm lineages

- ISL1: Present in amnion cells [28]

These factors provide specific regulatory benchmarks for assessing whether transgenic models recapitulate appropriate developmental gene regulatory programs.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methodologies

Reporter Gene Assays and Transgenic Systems

Reporter Gene Assays (RGAs) represent a powerful methodology for investigating gene expression regulation and cellular signaling pathway activation in embryonic contexts [2]. When applied to transgenic line validation, RGAs typically utilize easily detectable reporter genes (e.g., luciferase, fluorescent proteins) under the control of regulatory elements from genes of interest.

Table 2: Method Comparison for Embryonic Expression Validation

| Method | Mechanism | Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Reference Mapping | Computational projection of query data onto integrated embryonic atlas | Medium to High | Unbiased transcriptional profiling; Continuous developmental reference | Does not directly test regulatory function |

| Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs) | Quantitative assessment of thousands of candidate regulatory sequences in cellular models | Very High | Quantitative and reproducible; Tests variant effects systematically | Limited to in vitro contexts; May lack tissue/organismal context |

| Mouse Transgenic Enhancer Assays | Testing human regulatory sequences in mouse embryos with reporter constructs | Low | Provides rich, multi-tissue phenotypic data; Organismal context | Resource and labor intensive; Lower throughput |

| Combined MPRA-Transgenic Approach | Correlated screening followed by in vivo validation | Medium | Balances throughput with biological relevance; Strong correlation demonstrated | Still requires significant resources for in vivo component |

Recent advancements in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing have significantly improved the efficiency of generating stable RGA cell lines through site-specific integration of exogenous genes into defined genomic loci [2]. This technological progress enables more consistent and reproducible validation across laboratories.

Correlative Validation: Integrating MPRA and Transgenic Approaches

A powerful emerging paradigm involves combining high-throughput MPRAs with lower-throughput but physiologically relevant transgenic mouse assays. Recent research has demonstrated a "strong and specific correlation" between MPRA results in human neurons and enhancer activity in mouse embryonic systems [21].

In one comprehensive study, researchers designed an MPRA library testing over 50,000 sequences (270 bp tiles) derived from fetal neuronal ATAC-seq datasets and validated neuronal enhancers from the VISTA Enhancer Browser [21]. This library included:

- Natural variation: 167 common variants associated with psychiatric disorders

- Synthetic mutations: Transversion variants introduced every fourth base pair in elements with high expected activity

- Controls: 500 di-nucleotide scrambled sequences from enhancers negative in transgenic assays

Following MPRA screening in human excitatory neurons, variants with significant effects were tested in mouse transgenic assays, with four out of five high-impact MPRA variants confirmed to affect neuronal enhancer activity in mouse embryos [21]. This correlation validates the combined approach for efficiently identifying functional regulatory elements with in vivo relevance.

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Standardized scRNA-seq Benchmarking Workflow

Objective: To validate cellular identities and developmental states in transgenic embryo models by comparison to an integrated embryonic reference.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Process transgenic embryo models or reporter lines for scRNA-seq using standardized protocols (10x Genomics, Smart-seq2, etc.).

- Data Preprocessing: Align sequencing reads to reference genome (GRCh38 recommended) using uniform processing pipelines to minimize technical variability [28].

- Reference Projection: Utilize the integrated embryonic reference tool to project query data onto the standardized UMAP embedding.

- Cell Identity Prediction: Annotate predicted cell identities based on transcriptional similarity to reference cell populations.

- Lineage Validation: Assess expression of key lineage-specific markers identified in the reference (e.g., TBXT in primitive streak, ISL1 in amnion, LUM and POSTN in extraembryonic mesoderm) [28].

- Trajectory Analysis: Perform pseudotemporal ordering to validate developmental progression along appropriate trajectories.

Quality Control Metrics:

- Minimum cell recovery per sample: >3,000 cells

- Minimum gene detection per cell: >500 genes

- Maximum mitochondrial read percentage: <20%

- Projection confidence scores >0.7 for cell identity assignments

Combined MPRA-Transgenic Validation Pipeline

Objective: To functionally validate regulatory elements and their variants in transgenic systems.

Protocol:

- Library Design:

- Select regulatory regions (enhancers, promoters) based on epigenetic signatures (ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq) from relevant embryonic tissues.

- Include natural variants (GWAS-associated SNPs) and synthetic mutations (saturated or targeted mutagenesis).

- Incorporate scrambled negative controls and known positive controls (e.g., housekeeping gene promoters) [21].

MPRA Screening:

- Clone library into barcoded lentiviral vectors with minimal promoter driving reporter gene.

- Transduce into relevant cell models (e.g., differentiated human neurons for neuronal enhancers).

- Sequence barcodes from both DNA (representation) and RNA (expression) fractions after 48-72 hours.

- Calculate enhancer activity as log2(RNA counts/DNA counts) normalized to scrambled controls [21].

In Vivo Transgenic Validation:

- Select top candidate sequences (both reference and variant alleles) from MPRA screen.

- Clone into enSERT or similar transgenic vector with minimal promoter and reporter gene (e.g., LacZ).

- Microinject into mouse zygotes and integrate into safe harbor locus.

- Analyze reporter expression patterns at embryonic day 11.5 or other relevant stages by imaging and histology [21].

Data Integration:

- Correlate MPRA activity scores with transgenic expression patterns.

- Validate variant effects observed in MPRA through allele-specific comparisons in transgenic models.

Quality Control Metrics:

- Minimum barcode representation: >15 per tile

- Inter-replicate correlation: Pearson >0.7

- Positive control activity: Significant enrichment over scrambled controls

- Transgenic sample size: ≥3 embryos per construct

Visualization of Validation Workflows

Transcriptomic Validation Pathway

Regulatory Element Validation Framework

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and resources required for implementing robust validation benchmarks for embryonic expression studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Embryonic Expression Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Embryonic Reference | 3,304 cells; zygote to gastrula; standardized GRCh38 alignment | Transcriptomic benchmarking of embryo models | Publicly available reference tool [28] |

| Stable RGA Cell Lines | CRISPR/Cas9-edited with site-specific reporter integration; isogenic background | Quantitative enhancer/promoter activity screening | Custom generation per [2] |

| MPRA Library Components | Barcoded lentiviral vectors; minimal promoter; diverse regulatory tiles | High-throughput regulatory element screening | Custom synthesis following [21] |

| Transgenic Constructs | enSERT-compatible vectors; safe harbor locus targeting | In vivo validation of regulatory elements | VISTA Enhancer Browser resources [21] |

| Lineage Marker Panels | Validated antibodies for key lineages (e.g., ISL1 for amnion, TBXT for primitive streak) | Orthogonal validation of cell identities | Commercial antibody suppliers |

| Embryo Model Systems | Stem cell-based embryo models with appropriate ethical oversight | Test systems for transgenic reporter validation | Institutional stem cell core facilities |

The establishment of comprehensive validation benchmarks represents a critical step toward ensuring the reliability and interpretability of embryonic expression studies. The integrated transcriptomic atlas provides an unbiased foundation for assessing cellular identities, while complementary functional approaches like MPRA and transgenic assays enable direct testing of regulatory hypotheses. The demonstrated correlation between high-throughput screening methods and in vivo validation offers a pragmatic path forward for balancing throughput with biological relevance.

As the field advances, adherence to these validation standards—coupled with appropriate ethical oversight as outlined in ISSCR guidelines [29]—will be essential for building a robust knowledge base of human embryonic development. The reagents, protocols, and analytical frameworks presented here provide a foundation for implementing these benchmarks across diverse research programs focused on understanding and modeling human development.

Advanced Methodologies for Reporter Line Engineering and Application

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeted Integration into Safe Harbor Loci

The precision of CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling targeted modifications with unprecedented accuracy. A critical application of this technology involves the integration of transgenes—such as fluorescent reporters or therapeutic genes—into specific genomic locations. Random integration of exogenous DNA poses significant risks, including unpredictable expression levels, gene silencing, and potential disruption of essential host genes [30]. To overcome these challenges, researchers increasingly target genomic safe harbors (GSHs), which are loci capable of supporting stable, long-term transgene expression without adverse effects on the host cell [15] [31].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of major safe harbor loci and the cutting-edge CRISPR/Cas9 technologies for targeted integration. We focus specifically on their application in transgenic reporter line validation for embryonic expression research, providing experimental data, detailed methodologies, and key reagent solutions to support researchers in this field.

Comparison of Major Safe Harbor Loci

The selection of an appropriate safe harbor locus is fundamental to experimental success. The table below compares the key characteristics of the most widely used and promising loci based on current research.

Table 1: Comparison of Established and Emerging Safe Harbor Loci

| Locus Name | Genomic Context | Key Advantages | Documented Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAVS1 | Intron of PPP1R12C [32] | Well-characterized in human cells; robust expression; minimal adverse effects [32] [33]. | Reporter and therapeutic gene knock-in in human stem cells and Rhesus macaque iPSCs [30] [33]. | Potential for endogenous gene disruption; susceptibility to adjacent regulatory elements [15]. |

| H11 | Intergenic region on mouse chromosome 11 [15] | Open chromatin structure; high biosafety profile in studied artiodactyls [15]. | Stable EGFP expression in cashmere goats across cells, embryos, and adult tissues [15]. | Requires cross-species conservation analysis for new models [15]. |

| Rosa26 | Locus producing non-coding RNA [15] | Ubiquitous expression driven by endogenous promoter; cross-species conservation [15]. | Used in mice, sheep, and goats for consistent transgene expression [15]. | Promoter strength may vary between species and cell types. |

| LHCBM1 | Endogenous gene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [34] | Differential expression under light intensity control; enables high transgenic protein accumulation [34]. | 60-fold increase in valencene production in microalgae [34]. | Application is currently specific to microalgal systems. |

Quantitative Performance Data in Model Systems

Empirical data on integration efficiency and expression stability is crucial for selecting a locus. The following table summarizes performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Safe Harbor Loci Across Model Systems

| Model System | Target Locus | Integration Method | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goat Fetal Fibroblasts | H11 & Rosa26 | CRISPR/Cas9-HDR | Stable EGFP expression in 8 tissues of cloned offspring; normal growth phenotypes; unaltered transcriptional integrity of adjacent genes [15]. | [15] |

| Human Cells | AAVS1 | CRISPR/Cas9-HITI | Greater knock-in efficiency compared to HDR; functional fluorescence, bioluminescence, and MRI reporter activity [30]. | [30] |

| Zebrafish | otx2 & pax2a 5' UTR | CRISPR/Cas9 Knock-in | Faithful recapitulation of endogenous gene expression; no disturbance to native gene function; successful lineage tracing in MHB [35]. | [35] |

| Mouse Haploid ESCs | Actb 3' UTR | CRISPR/Cas9-HDR | Successful reporter knock-in without gene disruption; up to 97.6% co-selection efficiency with fluorescent reporters [36]. | [36] |

| Human Cells | AAVS1 | Type V-K CAST | Programmable integration of large DNA cargo (e.g., Factor IX) without double-strand breaks; high specificity with rare off-targets [31]. | [31] |

Experimental Workflow for Reporter Line Generation

The process of creating and validating a transgenic reporter line using CRISPR/Cas9 is multi-staged. The following diagram outlines the core workflow from target selection to final validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Stages

4.1.1 Locus Selection and gRNA Design

- Cross-Species Conservation Analysis: For non-traditional model organisms, identify potential safe harbor loci by analyzing syntenic regions of established loci (e.g., H11, Rosa26) using genomic databases and BLAST tools [15].

- gRNA Selection: Design sgRNAs with high on-target efficiency. Tools like CHOP-CHOP can be used to identify target sites near the intended integration point, typically within open chromatin regions for better accessibility [35]. The efficiency of candidate sgRNAs must be validated using assays like the T7E1 surveyor nuclease assay or single-strand annealing (SSA) reporter assays in relevant cell types before proceeding [36] [33].

4.1.2 Donor Plasmid Construction for HDR

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): Construct a donor plasmid containing your transgene of interest (e.g., EGFP) flanked by homology arms.

- Arm Length: While traditional arms are ~800 bp, studies in Chlamydomonas show that 50 bp arms can achieve high scar-less HDR efficiency, which can be beneficial for smaller vector sizes [34].

- Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI): As an alternative, design a donor vector that incorporates the same sgRNA target sequence. This leverages the NHEJ pathway, which can be more efficient than HDR, especially in non-dividing cells [30].

- Vector Backbone: Consider using minicircle DNA, which lacks a bacterial backbone and antibiotic resistance genes. This reduces vector size (improving delivery) and enhances biosafety for potential clinical translation [30].

4.1.3 Delivery, Selection, and Molecular Validation

- Delivery Method: For hard-to-transfect cells like primary fibroblasts or stem cells, nucleofection is highly effective. The 4D-Nucleofector system is commonly used with kits such as the P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit [33].

- Selection: Co-integrate a selection marker (e.g., puromycin resistance gene) into the donor construct. After delivery, apply the appropriate selection agent (e.g., 0.5-1 µg/mL puromycin) for 1-2 weeks to eliminate non-edited cells [33].

- Validation: Screen resistant clones using PCR with primers spanning the integration junctions. Confirm precise integration and sequence fidelity via Sanger sequencing. For ultimate validation, especially in cloned embryos or animals, Southern blotting provides definitive proof of correct, single-copy integration [33].

Advanced Technologies: Beyond Standard CRISPR-Cas9

While CRISPR/Cas9-HDR is widely used, new systems are emerging to address its limitations, such as low efficiency and reliance on cellular repair pathways.

5.1 CRISPR-Associated Transposases (CAST) CAST systems, such as the compact type V-K CAST derived from metagenomics, represent a paradigm shift. They facilitate programmable, cut-and-paste integration of large DNA cargos without creating double-strand breaks, thereby avoiding the error-prone NHEJ pathway [31]. These systems have been engineered for nuclear localization and can integrate a full therapeutic gene (e.g., Factor IX) into the AAVS1 safe harbor in human cells with high specificity and rare off-target events [31].

5.2 Lineage Tracing with CRISPR/Cas9 Barcoding Beyond simple reporter line generation, CRISPR/Cas9 can be used for dynamic cell lineage tracing. The principle involves introducing specific, heritable genetic barcodes into progenitor cells. As these cells divide and differentiate, the barcodes accumulate unique mutations. By sequencing these barcodes in descendant cells, researchers can reconstruct lineage relationships and differentiation trajectories during embryonic development with high resolution [37]. This is particularly powerful for studying the midbrain-hindbrain boundary and other complex developmental processes [35] [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of these experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table lists key solutions for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in at safe harbor loci.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Safe Harbor Gene Editing

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example | Function & Application Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmids | "All-in-one" plasmid (e.g., Addgene #79145) | Combines CAG-driven Cas9 (e.g., eSpCas9 for enhanced specificity) and gRNA expression in a single vector for simplified delivery. | [33] |

| Donor Plasmids | AAVS1-specific donor (e.g., Addgene #84209) | Contains transgene flanked by species-specific homology arms (e.g., rhesus macaque AAVS1 sequences) for HDR. | [33] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Matrigel, ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632), Accutase | Essential for maintaining and passaging sensitive cell types like iPSCs under feeder-free conditions, and improving post-transfection survival. | [33] |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, G418/Hygromycin | Antibiotics for selecting successfully transfected cells when the donor plasmid carries a corresponding resistance gene. | [36] [33] |

| Delivery Tools | 4D-Nucleofector System (Lonza) | Electroporation-based system optimized for high-efficiency delivery of CRISPR components into hard-to-transfect cells, including primary and stem cells. | [33] |