Functional Validation of CRISPR Mutants in Developmental Models: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating CRISPR-generated mutants in developmental models.

Functional Validation of CRISPR Mutants in Developmental Models: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating CRISPR-generated mutants in developmental models. It covers foundational principles of gene editing, explores advanced methodological applications across diverse model systems, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest 2025 research, this resource emphasizes the critical importance of cell-type-specific validation, the power of multi-omics approaches for comprehensive analysis, and the evolving landscape of precision editing tools for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Understanding CRISPR Editing Fundamentals in Developmental Systems

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) systems constitute an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea that protects against viral and plasmid attacks [1]. Since its repurposing for genome engineering in 2012, this RNA-guided system has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development by providing an unprecedented ability to make precise modifications to genomic DNA [2] [3]. The core principle of CRISPR-based systems is their programmability: a Cas nuclease is directed by a guide RNA (gRNA) to a specific DNA sequence, where it creates a double-strand break (DSB). The cell's subsequent repair of this break can be harnessed to create gene knockouts, precise insertions, or single-nucleotide changes [2] [1]. This guide will explore the core principles of these systems, objectively compare the performance of different editors and delivery methods, and detail their application and validation in functional genomics, with a specific focus on developmental models.

Basic Components and Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas Systems

Molecular Architecture: Cas Enzyme and Guide RNA

The fundamental machinery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two core components:

- Cas Enzyme: The Cas9 protein from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) is the nuclease most commonly used. It is responsible for cleaving the target DNA strand. Its activity is triggered upon recognition of a short DNA sequence known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). For SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [2].

- Guide RNA (gRNA): This is a synthetic, single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines two natural RNA elements: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains the ~20 nucleotide sequence that defines the target DNA site via Watson-Crick base pairing, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding [2] [1].

The simplicity of this system lies in its programmability; to redirect the nuclease to a new genomic locus, one only needs to redesign the ~20 nucleotide sequence within the gRNA [1].

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

The double-strand break created by the Cas9-gRNA complex is repaired by the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery, primarily through two pathways that determine the editing outcome:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is the dominant and error-prone repair pathway in mammalian cells. It directly ligates the broken ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cut site. If these indels occur within a protein-coding exon and cause a frameshift, they can lead to a gene knockout [2] [1]. NHEJ is efficient in both dividing and non-dividing cells.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This pathway uses a donor DNA template with homology to the sequences flanking the break to repair the DSB. By providing an engineered donor template, researchers can achieve precise gene knock-in or specific point mutations. However, HDR is less frequent than NHEJ and primarily occurs in dividing cells [2] [1].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these repair pathways.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Genome Editing

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | Gene knockout (indels) | Precise knock-in or correction |

| Donor Template Required | No | Yes |

| Efficiency in Mammalian Cells | High | Low |

| Cell Cycle Phase | All phases (predominant in G1, S, G2) | S and G2 phases |

| Major Application | Disrupting gene function | Inserting genes or making precise edits |

Workflow of a CRISPR-Cas9 Experiment

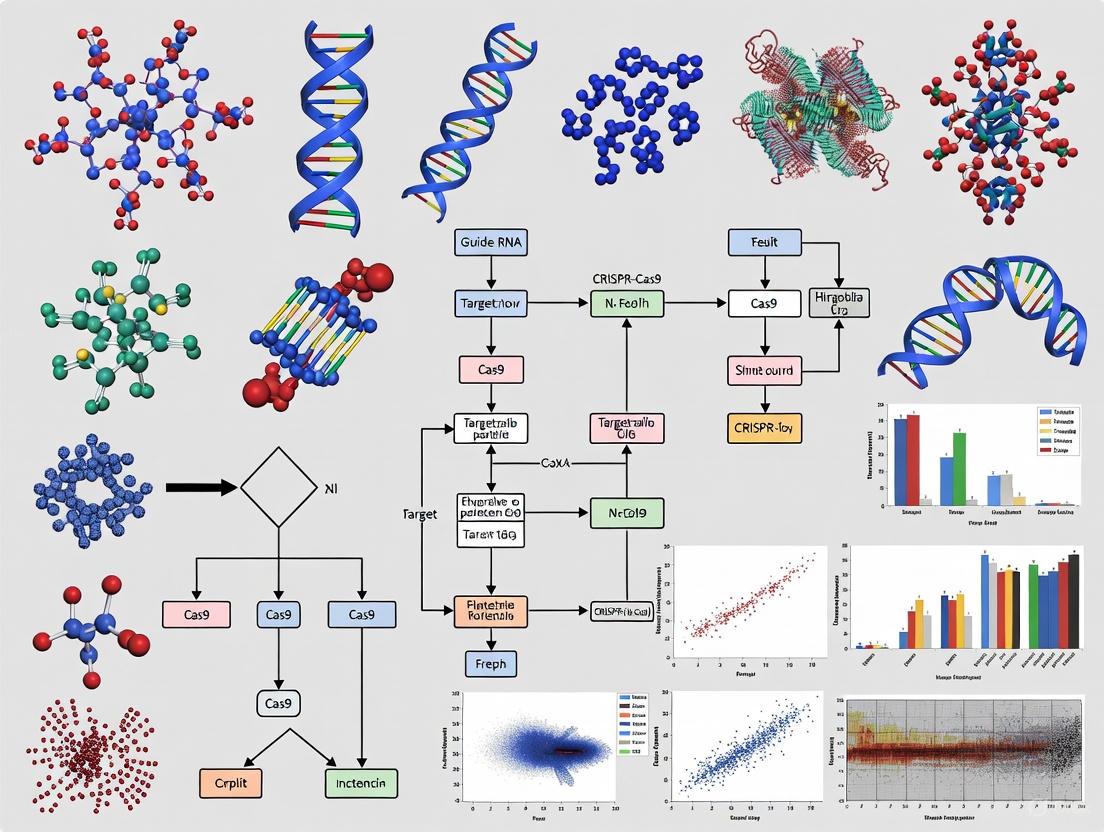

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for a CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing experiment, from design to validation.

Evolution of the CRISPR Toolkit: From Nucleases to Editors

The original CRISPR-Cas9 system has been extensively engineered to overcome limitations such as PAM restrictions, off-target effects, and the unpredictability of NHEJ-mediated edits.

Advanced Cas9 Variants

- High-Fidelity Cas9: Mutants like eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, and HypaCas9 were engineered to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining robust on-target activity [2].

- PAM-Restriction Relaxed Variants: Engineered proteins like xCas9 and SpRY recognize a broader range of PAM sequences, significantly expanding the targetable genomic space [2].

- Size-Optimized Cas9 Orthologs: Smaller Cas9 proteins, such as those from Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9) and Campylobacter jejuni (CjeCas9), are advantageous for viral delivery, particularly using the adeno-associated virus (AAV) which has a limited packaging capacity [2].

Base Editors and Prime Editors

To move beyond DSBs and enable more precise editing, two major classes of "DSB-free" editors have been developed.

- Base Editors (BEs): These are fusions of a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease (a "nickase") with a deaminase enzyme. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) convert a C•G base pair to a T•A pair, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert an A•T base pair to a G•C pair within a defined "editing window" near the PAM site. They enable efficient single-nucleotide changes without inducing a DSB, thus minimizing indel byproducts [2].

- Prime Editors (PEs): These represent a more versatile platform. They consist of a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme. A specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) both directs the complex to the target site and serves as a template for the reverse transcriptase to "write" the desired edit directly into the genome. Prime editors can mediate all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, with remarkably high precision and low off-target effects [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major CRISPR Editor Types

| Editor Type | Editing Action | Primary Outcome | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Creates DSB | Indels (Knockout) | Simplicity, high knockout efficiency | Unpredictable repair outcomes, prominent off-target effects |

| Cytosine Base Editor (CBE) | C → T (G → A) | Point Mutation | High efficiency, no DSB, low indels | Restricted to C-to-T/G-to-A edits within a ~5nt window |

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | A → G (T → C) | Point Mutation | High efficiency, no DSB, low indels | Restricted to A-to-G/T-to-C edits within a ~5nt window |

| Prime Editor (PE) | All point mutations, small insertions/deletions | Precome Edit | Versatility, unprecedented precision, no DSB | Lower efficiency compared to base editors, complex pegRNA design |

Functional Validation in Developmental Models: Protocols and Applications

CRISPR-Cas systems are indispensable for functional genomics in vertebrate developmental models like mice and zebrafish, allowing for high-throughput interrogation of gene function in vivo.

A Simple Validation Protocol for Mouse Embryos

A streamlined Cleavage Assay (CA) has been developed to efficiently validate CRISPR-mediated edits in preimplantation mouse embryos before embryo transfer, reducing reliance on time-consuming and expensive Sanger sequencing [4].

Experimental Protocol: Cleavage Assay (CA) for Mouse Embryos

- Electroporation: Mouse zygotes are electroporated with the preassembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of Cas9 protein and gRNA.

- In vitro Culture: Electroporated embryos are cultured to the blastocyst stage.

- Post-Culture Electroporation: Blastocysts are subsequently electroporated with the same RNP complex used in step 1.

- Principle of Detection: The core principle is that a successfully modified allele will no longer be recognized and cleaved by the RNP complex because the target sequence has been altered. In contrast, unmodified (wild-type) alleles will be cleaved.

- Outcome Analysis: Efficient cleavage in this second electroporation indicates a low initial editing efficiency. Conversely, a lack of cleavage indicates that a high proportion of the alleles were successfully modified in the first electroporation, thus predicting a high success rate for generating mutant mice [4].

High-Throughput Screening with Optimized sgRNA Libraries

The sensitivity of CRISPR screens depends critically on the efficiency of the sgRNA library. Recent benchmark studies have systematically compared library performance.

- Library Size and Efficiency: Studies show that smaller, more principled sgRNA libraries can perform as well as or better than larger libraries. For example, a minimal "Vienna-single" library (3 guides/gene) designed using VBC activity scores demonstrated stronger depletion of essential genes than the larger 6-guide Yusa v3 library in lethality screens conducted in HCT116, HT-29, RKO, and SW480 cell lines [5].

- Dual-targeting vs. Single-targeting: Dual-targeting libraries, which use two sgRNAs per gene to potentially create a deletion between cut sites, show stronger depletion of essential genes. However, they also exhibit a slight fitness reduction even in non-essential genes, possibly due to an elevated DNA damage response from creating two DSBs. This suggests a trade-off between efficacy and potential cellular stress [5].

Table 3: Benchmarking of CRISPR sgRNA Library Performance in Essentiality Screens

| Library Name | Guides per Gene | Design Principle | Performance in Essentiality Screens | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top3-VBC | 3 | Top Vienna Bioactivity scores | Strongest depletion of essential genes | High efficiency with minimal library size |

| Yusa v3 | ~6 | Pre-existing library design | Moderate performance | Larger size offers no advantage over Top3-VBC |

| Croatan | ~10 | Dual-targeting focused design | Strong depletion | Larger library size |

| Bottom3-VBC | 3 | Bottom Vienna Bioactivity scores | Weakest depletion | Validates predictive power of VBC scores |

| Vienna-Dual | Paired guides from top 6 VBC | Dual-targeting strategy | Strongest depletion overall | Potential for induced DNA damage response |

Computational Analysis and Workflow for Screening Data

The analysis of high-throughput CRISPR screens requires robust computational pipelines for quality control (QC) and hit identification. The MAGeCK-VISPR workflow is a comprehensive tool that addresses this need [6].

Key Steps in the MAGeCK-VISPR Workflow:

- Quality Control (QC): Defines QC measures at multiple levels: sequence level (GC content, base quality), read count level (mapping rate, Gini index for evenness), sample level (correlation between replicates, PCA), and gene level (enrichment for known essentials like ribosomal genes) [6].

- Hit Identification with MAGeCK-MLE: Employs a maximum-likelihood estimation algorithm to model sgRNA read counts and call essential genes under multiple conditions simultaneously. It can account for variable sgRNA knockout efficiency, improving the accuracy of fitness effect estimates (β scores) for each gene [6].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-based Functional Genomics

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nucleases | SpCas9, SaCas9, High-Fidelity SpCas9 (eSpCas9), CjCas9 | Executes DNA cleavage; different variants offer trade-offs in size, fidelity, and PAM recognition. |

| Precise Editors | Cytosine Base Editor (CBE), Adenine Base Editor (ABE), Prime Editor (PE) | Enables precise nucleotide changes without inducing double-strand breaks. |

| sgRNA Libraries | Brunello, Yusa v3, Vienna-single, Vienna-dual | Pre-designed pools of sgRNAs for genome-wide or pathway-focused loss-of-function screens. |

| Analysis Software | MAGeCK-VISPR, CRISPResso, CRISPRMatch | Computational pipelines for analyzing NGS data from editing experiments or screens, providing QC and hit identification. |

| Delivery Vectors | Adeno-associated Virus (AAV), Lentivirus, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Vehicles for introducing CRISPR components into cells (in vitro) or tissues (in vivo). |

| Validation Tools | Cleavage Assay (CA), T7 Endonuclease I assay, Sanger Sequencing | Methods to confirm the success and efficiency of genome editing. |

The field of genome editing is undergoing a transformative shift, moving beyond the well-characterized Cas9 and Cas12a systems. Two powerful forces are driving this expansion: the discovery of novel, rare CRISPR-Cas systems from microbial genomes and metagenomes, and the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to design entirely new gene-editing proteins. For researchers focused on functional validation of CRISPR mutants in developmental models, this burgeoning toolkit offers new precision, specificity, and targeting capabilities. This guide objectively compares the performance of these emerging editors against traditional alternatives, providing the experimental data and protocols needed to inform their application in basic research and drug development.

Part 1: The New Frontier of Natural CRISPR-Cas Diversity

The natural diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems is far greater than previously recognized. Ongoing mining of genomic and metagenomic data has led to an updated evolutionary classification, which now includes 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes [7]. This represents a significant expansion from the 6 types and 33 subtypes known five years ago, revealing a "long tail" of rare, low-abundance variants in prokaryotes [7].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of recently identified and notable Class 2 CRISPR systems, which are of particular interest for their application as genome-editing tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Novel and Established Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems for Gene Editing

| System / Variant | Type & Subtype | Key Features & Applications | Experimental Evidence & Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenCRISPR-1 (AI-designed) | N/A (Cas9-like) | Comparable on-target efficiency to SpCas9 (median indel rates: 55.7% vs 48.3%) [8]. Improved specificity: 95% reduction in off-target editing (median indel rates: 0.32% vs 6.1% for SpCas9) [8]. Low immunogenicity: Lacks immunodominant T-cell epitopes found in SpCas9 [8]. | Proof-of-concept study in HEK293T cells; data from preprint, not yet peer-reviewed [8]. |

| Cas14 | Class 2, Type VII | Metallo-β-lactamase (β-CASP) effector nuclease [7]. Targets RNA in a crRNA-dependent manner [7]. Found in archaea; targets transposable elements [7]. | Identification based on genomic mining; limited number of spacer hits; structural data available [7]. |

| Cas12g | Class 2, Type V | RNase activity with collateral RNase and single-strand DNase activities [9]. Potential for RNA targeting and diagnostics. | Experimentally characterized in E. coli; shown to function as an RNase [9]. |

| Cas13d | Class 2, Type VI | Compact RNA-targeting effector [9]. Can be modulated by a WYL-domain-containing accessory protein [9]. Application in transcriptome engineering and RNA diagnostics. | Study demonstrated RNA targeting by Cas13d; the smallest known type VI effector at the time [9]. |

| SpCas9 (Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) | Class 2, Type II-A | Benchmark system: Widely used, high on-target efficiency. Higher off-target effects compared to high-fidelity variants and AI-designed editors [8]. | Extensive validation in thousands of studies; considered the industry standard for DNA cleavage. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Novel Cas Variants in Human Cells

The following methodology, adapted from characterization studies for novel Cas proteins like Cas14 and the AI-generated OpenCRISPR-1, provides a framework for initial functional validation in a developmental research context [8] [7].

- Codon Optimization and Cloning: The gene sequence of the novel Cas variant is human-codon-optimized and cloned into a mammalian expression plasmid under a constitutive promoter (e.g., CMV or CAG).

- Cell Transfection: HEK293T or other relevant cell lines (including patient-derived iPSCs for disease modeling) are transfected with the following:

- Plasmid expressing the novel Cas protein.

- Plasmid expressing a chimeric single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting a well-characterized genomic locus (e.g., AAVS1 safe harbor).

- On-Target Efficiency Analysis: After 72 hours, genomic DNA is harvested.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): The target locus is PCR-amplified and subjected to deep sequencing to quantify insertion-deletion (indel) frequencies.

- T7 Endonuclease I Assay: Used as a rapid, initial validation method to detect cleavage-induced mutations.

- Off-Target Assessment: Potential off-target sites are predicted in silico based on sequence similarity to the sgRNA.

- These sites are amplified via PCR and deeply sequenced (NGS) to quantify mis-editing rates.

- Results are compared directly to SpCas9 programmed with the same sgRNA to determine relative specificity.

Part 2: The Role of AI in Designing and Optimizing CRISPR Tools

Artificial Intelligence is revolutionizing the CRISPR toolkit by moving beyond natural diversity to create bespoke editors. Large language models (LLMs), trained on massive datasets of protein sequences, can now generate novel, functional CRISPR-Cas proteins with optimized properties [8] [10].

Key AI Tools and Their Applications

Table 2: AI Models for Guiding CRISPR-based Genome Editing Experiments

| AI Tool / Model | Primary Function | Key Application in Research | Supporting Data / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProGen2 (Fine-tuned) | Generates novel CRISPR-Cas protein sequences from scratch [8]. | Creation of new editors like OpenCRISPR-1 with desired properties (e.g., high fidelity, altered PAM) [8]. | Generated 4 million novel sequences; 209 tested, many showed activity; OpenCRISPR-1 was a top performer [8]. |

| CRISPR-GPT | Acts as an AI "copilot" to design experiments, predict off-targets, and troubleshoot [11]. | Assists researchers in planning and optimizing CRISPR experiments, reducing trial and error. | Enabled a student to successfully perform a CRISPRa experiment on first attempt [11]. |

| DeepCRISPR, CRISTA, DeepHF | Predicts optimal guide RNAs (gRNAs) by analyzing genomic context and potential off-target effects [10]. | Improving the efficiency and specificity of CRISPR screens and therapeutic designs. | AI models consider multiple factors (on/off-target scores, mutation impact) to predict gRNA efficacy [10]. |

| SPROUT | Predicts the repair outcomes of CRISPR-Cas9 editing in primary T cells [10]. | Informing experimental design to maximize desired editing outcomes for cell therapies. | ML algorithm trained on a large dataset of editing events; high predictive accuracy [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing AI for gRNA Design and Validation

This protocol outlines how to integrate AI tools like CRISPR-GPT into a standard workflow for functional validation in a developmental model.

- Target Identification: Based on your research hypothesis (e.g., gene knockout in a zebrafish model), identify the target DNA sequence.

- AI-Assisted gRNA Design:

- Input the target sequence and experimental goal (e.g., "knockout for gene X in human iPSCs") into an AI platform like CRISPR-GPT [11].

- The AI agent will suggest multiple candidate gRNAs, rank them based on predicted on-target efficiency, and list potential off-target sites with their risk scores.

- Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize the top 3-5 AI-recommended gRNAs.

- Clone them into appropriate expression vectors alongside the chosen Cas nuclease (e.g., SpCas9, OpenCRISPR-1).

- Parallel Testing: Transfect the gRNA/Cas combinations into your cell model and perform on-target and off-target efficiency analysis as described in the previous protocol.

- Model Refinement: Compare the empirical data with the AI's predictions. This feedback can be used to refine the AI models for future projects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers embarking on the functional validation of novel CRISPR mutants, having the right reagents is critical. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Tool Validation

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Experimental Workflow | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery of CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) or mRNA in vivo; particularly effective for liver-targeting [12]. | Systemic delivery of Intellia Therapeutics' hATTR therapy [12]. |

| Mammalian Expression Plasmids | Cloning and expressing novel Cas variants and their sgRNAs in human cell lines. | Testing OpenCRISPR-1 activity in HEK293T cells [8]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits | High-throughput sequencing of target loci to quantify on-target editing efficiency and detect off-target effects. | Used in both OpenCRISPR-1 and clinical trial analysis to measure indel percentages [12] [8]. |

| Cas9 Nickases | Created by mutating one of the two nuclease domains; used in base editing or paired with another nickase for improved specificity. | OpenCRISPR-1 was converted into a nickase to expand its application potential [8]. |

| Patient-Derived iPSCs | In vitro disease modeling for functional validation of CRISPR edits in a relevant genetic background. | Cited as a key model for understanding gene function and developing therapies [10]. |

The CRISPR toolkit is expanding at an unprecedented rate, fueled by both the discovery of rare natural systems and the power of AI-driven design. For the research scientist, this means an array of new options: from highly specific, AI-designed editors like OpenCRISPR-1 to a growing menagerie of natural Cas variants with diverse functions. The experimental data clearly shows that these new tools can match or surpass the performance of the foundational SpCas9 system, particularly in specificity. As AI copilots like CRISPR-GPT begin to lower the barrier to complex experimental design, the functional validation of CRISPR mutants in developmental models will become more efficient, precise, and accessible, accelerating the path from genetic discovery to therapeutic application.

In functional genomics, the precise validation of gene function often involves creating and analyzing CRISPR mutants in developmental model organisms. The efficiency and outcome of genome editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 are intrinsically linked to the cellular DNA repair machinery [1] [3]. These repair pathways are not universally identical; their activity and prevalence differ significantly between dividing and non-dividing cells [13] [14]. For researchers using vertebrate models such as mice and zebrafish to study development, this distinction is critical. A comprehensive understanding of how DNA repair mechanisms operate in these different cellular contexts enables more accurate interpretation of mutant phenotypes, informs the selection of appropriate model systems, and guides the optimization of gene-editing experimental protocols [3]. This guide objectively compares the fundamental DNA repair pathways, their operational preferences in proliferating versus post-mitotic tissues, and the direct implications for designing and validating CRISPR-based experiments in developmental research.

Cells employ several major pathways to repair DNA damage, each specialized for specific types of lesions. The choice between these pathways has profound consequences for genome stability and the success of genome editing.

Table 1: Major DNA Repair Pathways and Their Characteristics

| Repair Pathway | Primary Damage Type Addressed | Key Proteins/Enzymes | Template Required? | Fidelity | Primary Activity in Cell Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Double-Strand Breaks (DSBs) | DNA-PKcs, Ku70/80, XRCC4 [13] | No | Error-Prone (can cause indels) [1] | All phases (G1, S, G2) [1] |

| Homologous Recombination (HR) | DSBs, especially during replication | RAD51, BRCA1/2, RPA [15] | Yes (sister chromatid) [16] | High-Fidelity [1] | S and G2 phases [1] |

| Base Excision Repair (BER) | Single-base damage, abasic sites | DNA glycosylases, APE1, POLβ [13] [17] | Yes (complementary strand) | High | All phases |

| Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) | Bulky, helix-distorting lesions | XPA-XPG, TFIIH, ERCC1 [13] [17] | Yes (complementary strand) | High | All phases |

| Mismatch Repair (MMR) | Replication errors, base-base mismatches | MSH2, MLH1 [15] | Yes (complementary strand) | High | S phase and post-replication |

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of how a cell might choose between the two primary pathways for repairing the double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9, highlighting the critical role of the cell cycle.

DNA Repair in Dividing vs. Non-Dividing Cells

The cellular context—specifically, whether a cell is actively progressing through the cell cycle or is in a quiescent/post-mitotic state—profoundly influences which DNA repair mechanisms are dominant and functionally critical.

Dividing Cells: A Versatile Repair Toolkit

In proliferating cells, such as those in developing tissues, stem cells, or cultured cell lines, the full arsenal of DNA repair pathways is active and accessible.

- HR Proficiency: The presence of a sister chromatid during the S and G2 phases provides a homologous template for high-fidelity repair via HR [1] [16]. This makes dividing cells capable of precise, error-free correction of DSBs.

- Active NHEJ: While HR is available, NHEJ remains highly active throughout the cell cycle and is a frequently used pathway for DSB repair, including those introduced by CRISPR-Cas9 [1] [3].

- Replication-Associated Repair: Dividing cells actively utilize MMR to correct replication errors and BER/NER to address lesions that could otherwise block the replication fork, preventing mutations from being passed to daughter cells [15].

Non-Dividing Cells: Heavy Reliance on Error-Prone Repair

In contrast, non-dividing or slowly dividing cells (e.g., neurons, muscle cells) operate under a different set of repair constraints, which has direct implications for their genomic stability and for gene-editing approaches in these cell types.

- HR Inefficiency: The absence of a sister chromatid as a repair template renders the HR pathway largely inactive [13] [16]. This leaves NHEJ as the primary mechanism for dealing with DSBs.

- NHEJ Dominance: The reliance on the error-prone NHEJ pathway in non-dividing cells means that DSBs are often repaired imperfectly. In the context of CRISPR, this favors outcomes that lead to gene knockouts rather than precise knock-ins [13].

- Accumulation of Lesions: Without the dilution effect of cell division, unrepaired DNA damage, particularly from oxidative stress and alkylation, can accumulate over time in non-dividing cells. This is a key factor linking DNA repair deficiencies to neurodegenerative diseases and aging [13] [16] [14].

Table 2: Functional Implications of Repair Pathways in Different Cell Contexts

| Cellular Context | Dominant DSB Repair Pathway | Outcome for CRISPR Editing | Associated Risks in Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dividing Cells (e.g., stem cells, progenitors) | Both NHEJ and HR are active [1]. | Knockout (via NHEJ) or precise knock-in (via HR) are possible [3]. | Unrepaired damage/mutations can be propagated, leading to cancer [16]. |

| Non-Dividing Cells (e.g., neurons) | Predominantly NHEJ, HR is inefficient [13]. | Primarily suited for gene knockout; precise knock-in is challenging. | Accumulation of DNA damage contributes to neurodegeneration (e.g., XP, CS) [13] [17]. |

Implications for CRISPR Functional Validation in Developmental Models

The interplay between cell division and DNA repair directly impacts the design, execution, and interpretation of gene-editing experiments in developmental models like zebrafish and mice.

Model System Selection and Experimental Design

The choice of model organism and the timing of experimental intervention must be deliberate.

- Leveraging High HR Efficiency: For experiments requiring precise gene knock-ins (e.g., introducing a specific disease-associated point mutation or a fluorescent tag), it is most efficient to perform CRISPR editing in early-stage embryos or in rapidly dividing cell cultures. This maximizes the chance that the edit will occur in cells that are in the S/G2 phase and can utilize the HR pathway [3].

- Exploiting NHEJ for Knockout: For simple gene knockouts, the prevalence of NHEJ across all cell types and cycle phases makes this a highly robust and widely applicable strategy. It can be effectively employed in both dividing and non-dividing tissues [18].

Interpretation of Mutant Phenotypes

Understanding repair mechanisms prevents misinterpretation of experimental results.

- Mosaic Founder Generation (F0): Injected embryos often exhibit mosaicism, where not all cells carry the same mutation. This occurs because the CRISPR-induced break can be repaired at different times after the first few cell divisions, leading to a mixture of edited and wild-type cells in the same animal [3]. Researchers must account for this by breeding to establish stable lines (F1) for phenotypic analysis.

- Phenotype Severity: The efficiency of generating a biallelic knockout in a target tissue can depend on the tissue's proliferative capacity. Highly proliferative tissues may show a more pronounced and consistent phenotype due to more efficient editing and turnover.

Optimization of Editing Protocols

Practical experimental parameters can be tuned to influence repair outcomes.

- gRNA and Cas9 Delivery: The method of delivering CRISPR components (e.g., plasmid DNA, mRNA, or pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes) can affect the kinetics and duration of Cas9 activity. RNP delivery, for instance, leads to rapid but transient activity, which can reduce off-target effects and may be suitable for targeting non-dividing cells [18].

- Providing Repair Templates: To enhance the efficiency of HR-mediated knock-in in dividing cells, a single-stranded or double-stranded DNA donor template with homology arms must be co-delivered with the Cas9 and gRNA components [3].

Essential Protocols for Validating CRISPR Genomic Edits

A critical final step in any CRISPR experiment is the rigorous validation of the intended genetic modification. The following protocols are standard in the field.

Protocol 1: Validating Knockout Mutations via TIDE Analysis

Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) is a rapid, effective method for quantifying editing efficiency and characterizing the spectrum of insertion/deletion (indel) mutations in a mixed cell population [19].

- PCR Amplification: Design primers that flank the target site, ensuring at least 200 base pairs of sequence on either side. Use genomic DNA from both wild-type (control) and CRISPR-treated cell populations or tissues as the PCR template.

- Sanger Sequencing: Purify the PCR products and submit them for Sanger sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Upload the sequencing chromatogram (.ab1) files from both the wild-type and edited samples, along with the gRNA target sequence, to the online TIDE software (https://tide.nki.nl).

- Interpretation: The TIDE algorithm decomposes the complex chromatogram from the edited sample and provides a detailed report of the types and frequencies of indels present, as well as an overall editing efficiency. A high frequency of indels that are not multiples of three indicates successful frameshift knockout.

Protocol 2: Genotypic Validation of Monoclonal Cell Lines

When a clonal, genetically uniform cell line is required, single cells must be isolated and screened [18].

- Isolation of Clones: After CRISPR treatment, seed cells at a very low density to allow for the formation of distinct single-cell colonies. Alternatively, use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to deposit single cells into individual wells of a multi-well plate.

- Expansion and Harvesting: Allow each colony to expand for 1-2 weeks. Split the culture, reserving one part for genomic DNA extraction and the other for continued culture (and potential cryopreservation).

- PCR and Sequencing: Amplify the target region from the genomic DNA of each clone. For initial screening of large deletions (using a dual-guRNA strategy), agarose gel electrophoresis can reveal size shifts. For precise identification of mutations, Sanger sequence the PCR products.

- Sequence Alignment: Align the sequencing results of each clone to the wild-type reference sequence using software like CRISPResso or basic alignment tools (e.g., BLAST) to identify the exact nature of the mutations on each allele [19].

- Protein-Level Validation (Western Blot): For knockout lines, confirm the absence of the target protein by Western blot analysis using an antibody against the protein of interest. This is a crucial step to ensure that the genomic edits have resulted in a null phenotype, especially if the indel did not cause a complete frameshift or if a truncated protein is produced [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Creates targeted double-strand breaks in the genome. | Can be delivered as plasmid, mRNA, or pre-complexed RNP. RNP is favored for reduced off-target effects [18]. |

| Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus via complementary base pairing. | Must be designed for high on-target and low off-target activity. Design tools like CRISPOR are essential [19]. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Template | Provides a DNA template for precise knock-in via the HR pathway. | Can be single or double-stranded DNA with homology arms flanking the desired insertion [3]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) / Viral Vectors | Methods for delivering CRISPR components into cells, especially for in vivo studies. | LNPs show high tropism for the liver and allow for re-dosing; viral vectors (e.g., AAV) offer broad cell tropism but can trigger immune responses [12]. |

| DNA Polymerases for Genotyping | Amplifies the target genomic region for validation by PCR. | Must be high-fidelity to avoid introducing errors during amplification. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Provides a comprehensive, quantitative analysis of editing efficiency and can screen for off-target effects. | More expensive and data-intensive than Sanger sequencing, but offers unparalleled depth and breadth of analysis [19]. |

This guide provides an objective comparison of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), organoids, and animal embryos for functional validation of CRISPR mutants in developmental research. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each system is crucial for selecting the appropriate model for your experimental goals.

The following table summarizes the fundamental attributes of each model system, which dictate their applicability in developmental studies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Developmental Model Systems

| Feature | iPSCs | Organoids | Animal Embryos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Somatic cells reprogrammed to an embryonic-like, pluripotent state [20]. | 3D structures derived from self-organizing PSCs or adult stem cells that mimic organ-like features [21] [22]. | The developing embryo within an animal model (e.g., mouse, zebrafish). |

| Plasticity & Developmental Potential | High pluripotency; can differentiate into any cell type [20]. | Multipotent or region-specific; mimic developing or adult tissue [21] [23]. | Totipotent/Pluripotent; gives rise to a complete, functional organism. |

| Key Advantage for CRISPR Validation | Facilitate human genetic disease modeling and high-throughput screening [23] [24]. | Recapitulate human tissue complexity and cell-cell interactions in a 3D environment [25] [26]. | Provide the full, in vivo context of development, including systemic cues. |

| Primary Limitation | Lack the complex 3D architecture and microenvironment of developing tissues [23]. | May lack full maturation, vascularization, and innervation; challenges in reproducibility [21] [26]. | Significant biological differences from humans; ethical considerations; high cost [23] [24]. |

Applications in CRISPR-Based Functional Validation

Each model system offers unique advantages for investigating gene function in development, as detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Functional Validation Applications for CRISPR Mutants

| Research Application | iPSCs | Organoids | Animal Embryos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Modeling | Excellent for modeling monogenetic hereditary diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's disease-causing mutations in APP, PSEN1) [24]. | Model complex diseases and cancer; capture tumor heterogeneity and allow drug screening on patient-derived tissues [21] [25]. | Traditional gold standard for studying systemic diseases and complex phenotypes. |

| Studying Early Development | Differentiate into specific lineages to study early cell fate decisions [23]. | Model human-specific aspects of organogenesis and tissue patterning (e.g., brain, kidney, intestine) [21] [23]. | Directly observe the dynamic process of embryogenesis and morphogenesis in real time. |

| Drug Discovery & Toxicology | High-throughput screening of compound libraries on human cells [20]. | Intermediate-to-high throughput screening in a more physiologically relevant human tissue context [21] [26]. | Lower throughput; used for pre-clinical validation of efficacy and toxicity in a whole-body system. |

| Personalized/Precision Medicine | Source for patient-specific iPSC lines to test individualized therapies [20]. | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) can be used to test patient-specific drug responses [26] [27]. | Not directly applicable. |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Workflows

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing in iPSCs and Organoids

The following workflow is commonly used for introducing mutations in iPSCs and subsequent organoid differentiation [24].

Figure 1: Key steps for generating and analyzing CRISPR-edited iPSC-derived organoids.

Detailed Methodologies:

sgRNA Design and Delivery:

- sgRNA Design: Design a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) with high on-target efficiency and low off-target potential for your gene of interest. The target sequence must be adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM, e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) [24].

- Delivery to iPSCs: Deliver the CRISPR/Cas9 system (as plasmid, ribonucleoprotein complex) into iPSCs using methods such as electroporation or lipofection. For iPSCs, non-integrating methods are often preferred for clinical relevance [20].

Validation of Edited iPSC Clones:

- After delivery, culture iPSCs and allow them to form single-cell-derived colonies.

- Pick individual clones and expand them.

- Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR amplification of the targeted genomic region.

- Validate the introduction of the desired mutation using Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing. Karyotyping is recommended to ensure genomic stability [20].

Organoid Differentiation from Edited iPSCs:

- Culture the validated, edited iPSC clones in conditions that direct differentiation toward the desired germ layer (e.g., endoderm, mesoderm, ectoderm).

- Embed the differentiating cells in an extracellular matrix (ECM) like Matrigel or Geltrex, which provides crucial 3D structural support and biochemical cues [28].

- Guide further maturation by sequentially adding specific growth factors and small molecules to the culture medium to mimic developmental signaling pathways (e.g., WNT, BMP, FGF) [21] [28]. This process can take several weeks to generate mature organoids.

Phenotypic Analysis of Mutant Organoids:

- Imaging: Use immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy to analyze structural changes, cell differentiation markers, and protein localization.

- Transcriptomics: Perform single-cell or bulk RNA sequencing to uncover global gene expression changes resulting from the mutation.

- Functional Assays: Conduct assays specific to the organoid type (e.g., calcium imaging for neuronal activity, albumin production for hepatic organoids, electrophysiology for cardiac organoids) [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Based Developmental Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Reprogram somatic cells to create iPSCs. | Yamanaka Factors: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) [20]. Delivered via viral (lentivirus, Sendai virus) or non-viral (episomal plasmids, mRNA) methods. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides a 3D scaffold for organoid growth, mimicking the native basement membrane. | Animal-Derived: Matrigel, Geltrex, Cultrex [28]. Xeno-Free: VitroGel [28]. Choice affects differentiation efficiency and organoid maturity. |

| Guidance Factors | Directs iPSC differentiation and organoid patterning. | Growth factors and small molecules (e.g., WNT agonists, BMP inhibitors, FGF, EGF) added sequentially to culture media [21] [28]. |

| CRISPR Components | Enables precise genome editing. | Cas9 Nuclease: Creates double-strand breaks. sgRNA: Guides Cas9 to the target DNA sequence [25] [24]. |

| Cell Culture Media | Maintains stem cell pluripotency or supports organoid differentiation. | iPSC Maintenance: mTeSR Plus, Essential 8 [20]. Organoid Differentiation: Defined media kits or lab-formulated cocktails [28]. |

Selecting the optimal model requires balancing physiological relevance, experimental tractability, and resource constraints. The following diagram outlines key decision criteria.

Figure 2: A simplified decision pathway for selecting a model system based on key research questions.

For functional validation of CRISPR mutants in developmental studies, the integration of these models often provides the most powerful approach. A common strategy involves using iPSCs for high-throughput genetic manipulation and initial screening, followed by organoid differentiation to model tissue-level phenotypes, with final validation in animal embryos for systemic and physiological context. This multi-tiered methodology leverages the unique strengths of each system to build a comprehensive understanding of gene function in development.

Practical Implementation Across Developmental Model Systems

The functional validation of CRISPR mutants in developmental models is a cornerstone of modern biological research and therapeutic development. The efficacy of these experiments is profoundly influenced by the method chosen to deliver gene-editing tools into target cells. Among the various strategies available, Virus-Like Particles (VLPs), electroporation, and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as leading technologies. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three delivery methods, focusing on their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal tool for their specific application.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of VLP, electroporation, and LNP delivery systems for CRISPR-based editing tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Key CRISPR Delivery Strategies

| Feature | Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Electroporation | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cargo | mRNA, RNP [29] [30] | Plasmid DNA, mRNA, RNP [31] | DNA, mRNA, RNP [31] [32] |

| Editing Efficiency | ~50% base editing in 293T cells [30] | Highly efficient [31] [33] | 37% liver editing, 19% lung editing in mice [32] |

| Mechanism | Viral capsids package and deliver cargo; transient expression [29] | Electrical pulses create transient pores in cell membrane [31] | Lipid-encapsulated vesicles fuse with cell membranes [31] |

| Key Advantage | High transduction efficiency + transient activity [29] | Broad cargo compatibility and high efficiency [31] | Suitable for in vivo delivery; proven clinical use [32] |

| Major Limitation | Complex production and scalability challenges [33] | Can be damaging to cells [31] | Lower and variable efficiency depending on cell type [31] |

| Safety Profile | Safer than viral vectors (e.g., "Gag-Only" strategy eliminates integration risk) [30] | No risk of genomic integration [31] | Lower immunogenicity than viral vectors; transient expression [32] |

| Ideal Application | Delivery to hard-to-transfect cells; high-efficiency editing with reduced off-target concerns [29] [30] | Research applications, especially with easy-to-transfect cell lines; ex vivo therapy (e.g., Casgevy) [31] | In vivo therapeutic delivery, particularly to liver and lungs [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Virus-Like Particles (VLPs)

Protocol: Production of Lentivirus-Like Particles (LVLPs) with Gag-Only Strategy [30]

- Plasmid Transfection: Lenti-X 293T cells are plated and transfected using a reagent like LipoMax with a plasmid mix. A "Gag-Only" strategy uses HIV-Gag protein while omitting the Pol protein to eliminate risks associated with reverse transcriptase and integrase.

- VLP Collection and Concentration: Supernatants are collected 48-72 hours post-transfection, clarified by centrifugation or filtration, and concentrated using a commercial concentrator.

- Functional Validation: The purified LVLPs are used to transduce target cells (e.g., 293T, Jurkat). Editing efficiency is assessed by sequencing the target genomic locus to quantify insertions/deletions (% indels) or base conversions.

Supporting Data:

- A study implementing an optimized HDVrz-psi-LVLP system achieved approximately 50% base editing efficiency in 293T cells and 20% efficiency in Jurkat cells [30].

- MaxCyte electroporation for VLP production demonstrated that optimized electroporation conditions and the use of a chemical enhancer can significantly increase VLP editing activity in harvested supernatants [33].

Electroporation

Protocol: Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 as Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) via Electroporation [31] [33]

- RNP Complex Formation: The Cas9 protein is pre-complexed with guide RNA (gRNA) in vitro to form an active RNP complex.

- Cell Preparation: Target cells are harvested and resuspended in an appropriate electroporation buffer.

- Electroporation: The cell suspension is mixed with the RNP complexes and subjected to a controlled electrical pulse using specialized instrumentation.

- Post-Processing: After electroporation, cells are rested and then transferred to complete culture media to recover.

Supporting Data:

- Electroporation is recognized as a highly efficient method for delivering RNP complexes into a broad range of cell types [31].

- Electroporation has proven successful for ex vivo gene editing, as exemplified by the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based drug, Casgevy, for sickle cell anemia [31].

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

Protocol: In Vivo Editing with Stable Cas9 RNP-LNPs [32]

- RNP Formulation: A thermostable Cas9 protein (e.g., engineered iGeoCas9) is complexed with sgRNA to form an RNP.

- LNP Encapsulation: The RNPs are encapsulated into LNPs using microfluidics or other mixing techniques. The LNP formulation typically includes ionizable cationic lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids.

- In Vivo Delivery: The formulated RNP-LNPs are administered systemically (e.g., via intravenous injection) to the target organism.

- Efficiency Assessment: Editing efficiency in tissues (e.g., liver, lung) is quantified by next-generation sequencing (NGS) of extracted genomic DNA.

Supporting Data:

- A single intravenous injection of iGeoCas9 RNP-LNPs in mice achieved genome-editing levels of 37% in the liver and 16% in the lungs in a reporter model. Furthermore, the system edited the disease-causing SFTPC gene in lung tissue with 19% average efficiency [32].

Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the generalized workflows for implementing each of the three delivery strategies.

Diagram 1: VLP production starts with transfection of producer cells, followed by harvesting and concentration of particles before target cell transduction.

Diagram 2: Electroporation involves direct delivery of pre-assembled CRISPR components into target cells via electrical pulses.

Diagram 3: LNP delivery encapsulates CRISPR cargo for systemic administration and subsequent tissue editing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Delivery Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Packaging Plasmids | Provides structural and functional proteins for VLP assembly. | HIV-Gag plasmid for "Gag-Only" LVLPs to enhance safety [30]. |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids | Key component of LNPs for encapsulating cargo and promoting endosomal escape. | Used in LNP formulations for efficient in vivo RNP delivery to lungs and liver [32]. |

| Electroporation Instrument | Applies controlled electrical fields to facilitate cargo delivery into cells. | MaxCyte electroporation systems enable scalable, cGMP-compliant VLP and RNP delivery [33]. |

| Concentration Reagent | Concentrates and purifies VLPs from cell culture supernatant. | Lenti-X Concentrator is commonly used for this purpose [30]. |

| Thermostable Cas9 | A engineered Cas9 variant with high stability, beneficial for RNP-LNP formulation. | iGeoCas9 demonstrates >100x higher editing than native GeoCas9 and works well in LNP delivery [32]. |

| Chemical Transfection Reagent | Facilitates plasmid DNA delivery into producer cells for VLP generation. | LipoMax transfection reagent is used for plasmid delivery in 293T cells [30]. |

The choice between VLPs, electroporation, and LNPs is not one of absolute superiority but of strategic alignment with experimental goals. Electroporation excels in high-efficiency ex vivo delivery for research and validated therapies. LNPs offer a powerful, clinically proven route for in vivo delivery, particularly to the liver and lungs. VLPs represent a versatile hybrid, combining the high transduction efficiency of viral systems with the transient, safer profile of non-viral methods, especially in their advanced "Gag-Only" configurations. For functional validation of CRISPR mutants in developmental models, researchers must weigh these performance characteristics against their specific needs for efficiency, safety, scalability, and target system.

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing with advanced cellular models represents a transformative approach in developmental biology and drug discovery. This guide compares established methodologies for generating functional neuronal networks from both mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), with emphasis on their application for functional validation of CRISPR mutants. These models provide invaluable platforms for studying neurodevelopment, disease modeling, and screening therapeutic compounds, with each system offering distinct advantages and limitations for researchers [34] [35] [36].

The fundamental workflow involves three critical phases: (1) directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into neural lineages, (2) precision genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce disease-relevant mutations, and (3) functional validation through electrophysiological and morphological characterization. This objective comparison provides researchers with the experimental data necessary to select the most appropriate model system for their specific functional validation requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Neural Differentiation Protocols

Efficiency and Characterization of Derived Neuronal Networks

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for different neural differentiation approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neural Differentiation Methods

| Method | Differentiation Time | Neuronal Purity | Key Markers | Electrophysiological Maturity | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse ESC (Dorsal NPC) | 14-20 days [36] | High PAX6+ NPCs [36] | PAX6, SOX1, Nestin [36] | Not specified | High-throughput screening, developmental studies [36] |

| Human iPSC (NGN2-Induced) | 7-10 days [34] | Highly pure cortical neurons [34] | MAP2, NeuN [34] | Requires glial co-culture for full maturity [34] | Disease modeling, circuit engineering [34] |

| Human iPSC (Simplified Protocol) | 8-10 weeks [35] | ~60% neurons, ~40% astrocytes [35] | MAP2, Synapsin, GFAP [35] | Mature properties without co-culture [35] | Neuropsychiatric disease modeling, network studies [35] |

| Human iPSC (Dorsal NPC) | 14-20 days [36] | High PAX6+ NPCs [36] | PAX6, SOX1, Nestin [36] | Further differentiation required | Cerebral cortex modeling, neurodegenerative disease [36] |

Electrophysiological Properties of Human iPSC-Derived Neurons

Quantitative assessment of neuronal function is critical for validating CRISPR-edited lines:

Table 2: Electrophysiological Properties of Mature Human iPSC-Derived Neurons [35]

| Parameter | Value (Mean ± SEM) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Resting Membrane Potential | -58.2 ± 1.0 mV | Indicates healthy neuronal state |

| Capacitance | 49.1 ± 2.9 pF | Reflects membrane surface area |

| Action Potential Threshold | -50.9 ± 0.5 mV | Demonstrates excitability |

| Action Potential Amplitude | 66.5 ± 1.3 mV | Shows depolarization capability |

| Peak AP Frequency | 11.9 ± 0.5 Hz | Indicates firing capacity |

| Spontaneous Synaptic Activity | 74% of neurons | Evidence of network formation |

| Synaptic Event Amplitude | 16.03 ± 0.82 pA | Quantifies synaptic strength |

| Synaptic Event Frequency | 1.09 ± 0.17 Hz | Measures synaptic activity level |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generation of Dorsal Neural Progenitor Cells from Mouse and Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

This optimized protocol generates homogeneous dorsal PAX6-positive NPCs suitable for cerebral cortex modeling [36].

Materials and Reagents

- Pluripotent Stem Cells: Mouse ESCs or human iPSCs/ESCs

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Dorsomorphin (BMP inhibitor), SB431542 (SMAD inhibitor)

- Basal Media: DMEM/F12, Neurobasal medium

- Supplements: N2, B27, GlutaMAX, FGF2 (20 ng/ml)

- Extracellular Matrix: Matrigel/Geltrex or Laminin

- Specialized Reagent: STEMdiff Neural Rosette Selection Reagent

Single BMP Inhibition Method (14-20 days)

- EB Formation (Day 0): Detach human iPSCs/ESCs and plate at 1×10^6 cells per well in ultralow-attachment plates in EB1 medium (neurobasal medium containing 1% N2, 2% B27, and 1.25 μM dorsomorphin) [36].

- EB Maintenance (Days 1-10): Culture EBs in suspension with medium changes every 3 days.

- NPC Plating (Day 10): Dissociate EBs with Accutase and plate at 3×10^5 cells per well on Geltrex-coated plates in NPC1 medium (DMEM/F12 with 1% N2, 2% B27, and 20 ng/ml FGF2).

- Rosette Selection (Days 15-20): Select neural rosettes using STEMdiff Neural Rosette Selection Reagent when visible (typically 5 days after plating).

- NPC Expansion: Dissociate rosettes and passage cells in NPC1 medium with ROCK inhibitor (10 μM Y-27632) to enhance survival.

Double BMP/SMAD Inhibition Method (13 days)

- EB Formation (Day 0): Plate 80% confluent hiPSCs/hESCs on ultralow-attachment plates in EB2 medium (DMEM/F12 with 20% KOSR, 5 μM dorsomorphin, and 10 μM SB431542).

- EB Patterning (Days 1-5): Maintain EBs in EB2 medium with regular monitoring.

- Neural Induction (Days 6-9): Switch to neural induction medium (DMEM/F12 with 1% N2, 2% B27) for 4 days.

- NPC Plating (Day 10): Plate EBs on poly-L-ornithine/laminin-coated surfaces in NPC medium.

- Rosette Selection and Expansion: Select and expand rosettes as in the single inhibition method.

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in these differentiation protocols:

Figure 1: Neural Differentiation Signaling Pathway. Pathway inhibition drives differentiation toward dorsal neural fates.

Protocol 2: Differentiation of Electrophysiologically Mature Human iPSC-Derived Neuronal Networks

This simplified protocol generates self-contained neuronal networks with both neurons and astrocytes without requiring co-culture [35].

Materials and Reagents

- Human iPSC-Derived Neural Precursor Cells (NPCs): Passages 5-11

- Coating Reagents: Poly-L-ornithine, Laminin (50 μg/ml)

- Neural Differentiation Medium: Neurobasal medium, 1% N2, 2% B27-RA, 1% NEAA, BDNF (20 ng/ml), GDNF (20 ng/ml), dibutyryl cyclic AMP (1 μM), ascorbic acid (200 μM), laminin (2 μg/ml)

- Maintenance Medium: Same as above but without laminin

Differentiation Procedure (8-10 weeks)

- Surface Coating (Day -2): Coat coverslips with poly-L-ornithine for 1 hour at room temperature, wash with sterile water, then apply laminin solution (50 μg/ml) for 15-30 minutes at 37°C.

- NPC Plating (Day 0): Dissociate NPCs with collagenase and plate on coated coverslips. Allow cells to attach for 1 hour in neural differentiation medium before adding additional medium.

- Early Differentiation (Weeks 1-4): Perform complete medium changes three times per week.

- Network Maturation (Weeks 5-10): Change only half of the medium volume three times per week to preserve secreted factors.

- Functional Assessment (Weeks 8-10): Perform electrophysiological recordings or immunocytochemistry.

Protocol 3: Engineering Defined Circuits of Human iPSC-Derived Neurons and Rat Glia

This specialized protocol creates topologically controlled neuronal circuits for drug screening applications [34].

Materials and Reagents

- Microfabricated PDMS Structures: Custom microstructures with node and microchannel design

- Microelectrode Arrays (MEAs): For stimulation and recording

- Human iNeurons: NGN2-induced iPSC-derived neurons

- Rat Primary Glial Cells: Isolated from postnatal rat brain

- Antifouling Coating: Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) to prevent axonal overgrowth

Circuit Creation and Maintenance

- Surface Preparation: Apply antifouling PVP coating to PDMS microstructures to confine growth to designated areas.

- Cell Seeding: Seed either dissociated cells or pre-aggregated spheroids at optimized neuron-to-glia ratios into microstructure nodes.

- Circuit Development: Culture circuits for >50 days with regular medium changes.

- Functional Monitoring: Record spontaneous and evoked activity using MEAs.

- Pharmacological Testing: Apply compounds like magnesium chloride to validate inhibitory responses.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this engineered neural circuit platform:

Figure 2: Engineered Neural Circuit Workflow. PDMS microstructures guide unidirectional neural circuit formation.

CRISPR Validation in Developmental Neural Models

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Functional Validation

The following table outlines the key steps and considerations for CRISPR-mediated functional validation in neural models:

Table 3: CRISPR-Cas9 Validation Workflow for Neural Models [37] [38] [39]

| Step | Method Options | Key Considerations | Validation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA Design | CRISPR design websites/software [37] | Minimize off-target effects, ensure high on-target activity [37] | BLAST analysis, pre-validation with positive controls [40] |

| Delivery Method | Viral vectors, electroporation, lipid-based transfection [37] | Optimize for specific cell type (iPSCs, NPCs, or neurons) [37] | Fluorescence markers, antibiotic selection |

| Gene Editing | Knockout, knock-in, point mutations [37] | Use controls: non-targeting gRNA (negative), validated gRNA (positive) [38] | T7E1 assay, Sanger sequencing, NGS [38] [39] |

| Validation of Editing | T7E1, Sanger sequencing, TIDE, NGS [38] [39] | T7E1 for initial screening, sequencing for precise mutation identification [38] | PCR, sequencing traces, restriction digest |

| Loss of Expression | Western blot, RT-PCR, flow cytometry [38] | Confirm complete protein knockout, not just DNA editing [38] | Antibody staining, functional assays |

| Functional Phenotyping | MEA recording, patch clamp, calcium imaging [34] [35] | Assess electrophysiological consequences in mature neurons | Comparison with isogenic controls, rescue experiments |

Methods for Validating CRISPR Editing Efficiency

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Mismatch Cleavage Assay

The T7E1 assay provides a rapid, cost-effective method for initial screening of CRISPR editing efficiency [38].

Procedure:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest genomic DNA from edited cells 3-7 days post-transfection.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target region using high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., AccuTaq LA).

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and reanneal PCR products to create wild-type/mutant heteroduplexes.

- T7E1 Digestion: Incubate with T7 Endonuclease I to cleave mismatched heteroduplexes.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze cleavage products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Efficiency Calculation: Determine efficiency from band intensity ratios [38].

Sequencing-Based Validation Methods

For precise characterization of CRISPR-induced mutations, sequencing methods are essential:

- Sanger Sequencing with TIDE Analysis: Provides quantitative data on indel frequencies without clonal isolation [38].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Enables highly sensitive detection of low-frequency mutations and off-target effects [39].

- Amplicon Sequencing: Focused analysis of specific target sites with deep coverage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Neural Differentiation and CRISPR Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Protocol Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Dorsomorphin, SB431542, Y-27632 [36] | Direct neural differentiation, enhance cell survival [36] | NPC differentiation, cell passaging |

| Growth Factors | FGF2, BDNF, GDNF [35] [36] | Support NPC proliferation, neuronal maturation/survival [35] | NPC maintenance, neuronal differentiation |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, Laminin, Poly-L-ornithine [35] [36] | Provide substrate for cell attachment and neurite outgrowth | Pluripotent stem cell culture, neuronal differentiation |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM/F12, Neurobasal, BrainPhys [35] [41] | Support specific stages of neural development | All protocols |

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 nuclease, guide RNAs, donor templates [37] [40] | Enable precise genome editing | CRISPR validation across all models |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 enzyme, sequencing primers, antibodies [38] | Confirm successful gene editing and protein loss | CRISPR validation steps |

The choice between mouse embryo-derived and human iPSC-derived neuronal models depends on specific research requirements. Mouse ESC-derived NPCs offer rapid generation (2-3 weeks) of homogeneous dorsal progenitors ideal for high-throughput screening [36]. In contrast, human iPSC-derived models provide species-specific relevance for disease modeling, with NGN2-induced neurons yielding rapid, pure cultures [34], while simplified protocols generate self-contained networks with mature electrophysiological properties [35].

For functional validation of CRISPR mutants, each system presents distinct advantages. Engineered circuits of human iNeurons enable high-content screening of defined networks [34], while the simplified coculture-free protocol produces reproducible electrophysiological readouts [35]. The integration of robust CRISPR validation methods—from initial T7E1 screening to comprehensive NGS analysis—ensures accurate interpretation of phenotypic outcomes in these developmental models [38] [39].

These complementary approaches empower researchers to address specific questions in neurodevelopment and disease mechanisms, with the optimal system determined by the balance between throughput, physiological relevance, and experimental complexity required for each functional validation study.

The application of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology has revolutionized functional genomics, enabling systematic loss-of-function analyses on an unprecedented scale. Within developmental models research, CRISPR libraries facilitate the functional validation of mutants by allowing researchers to connect genetic perturbations to phenotypic outcomes in a high-throughput manner. These libraries employ advanced guide RNA (gRNA) designs optimized for maximum knockout efficiency without sacrificing specificity, providing powerful tools for identifying genes essential for specific biological processes or disease states [42]. The emergence of focused and genome-wide libraries has been particularly transformative for investigating gene function in developmental contexts, where precise spatiotemporal gene regulation is critical.

The fundamental principle underlying CRISPR library screening involves the delivery of numerous gRNAs targeting multiple genes simultaneously, followed by the application of selective pressure to identify genes influencing particular pathways or phenotypes. Early work demonstrated that focused CRISPR/Cas9-based lentiviral libraries could successfully identify host genes essential for bacterial toxin intoxication, establishing the methodology as robust for functional genomics applications [43]. As the field has progressed, library design and screening methodologies have become increasingly sophisticated, incorporating computational approaches and deep learning models to enhance gRNA efficacy predictions [44].

CRISPR Library Formats: Arrayed versus Pooled Designs

Structural and Functional Comparisons

CRISPR libraries are primarily available in two distinct formats—arrayed and pooled—each with characteristic advantages and implementation requirements suited to different experimental goals in functional validation.

Arrayed Libraries (e.g., LentiArray CRISPR libraries) are formatted in multi-well plates with individual gene targets (and up to four gRNAs) located in separate wells. This configuration is particularly compatible with high-throughput screening platforms where phenotypic readouts are complex or require spatial separation, such as microscopic analysis of morphological changes in developmental models. The arrayed format enables researchers to easily trace which genetic perturbation produces which observed phenotype, simplifying hit identification without the need for sequencing deconvolution [42].

Pooled Libraries (e.g., LentiPool CRISPR libraries) contain collections of gRNA lentiviruses combined in a single tube, allowing for the simultaneous introduction of thousands of genetic perturbations into a cell population. This approach is particularly powerful for negative or positive selection screens where the relative abundance of specific gRNAs is monitored before and after selective pressure. Pooled screens are more resource-efficient than arrayed formats but require next-generation sequencing (NGS) for hit identification, adding computational overhead to the screening process [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Arrayed and Pooled CRISPR Library Formats

| Feature | Arrayed Libraries | Pooled Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Format | Individual gRNAs in separate wells | All gRNAs mixed together |

| Screening Readout | Direct phenotypic assessment | NGS-based gRNA quantification |

| Infrastructure Requirements | High-throughput screening platforms | Standard cell culture with NGS capability |

| Best Applications | Complex phenotypes, developmental morphology | Fitness-based selection screens |

| Hit Identification | Directly linkable to well position | Requires sequencing deconvolution |

| Cost Considerations | Higher reagent costs | Lower reagent costs, added NGS expense |

Library Diversity and Specialization

CRISPR libraries are available with varying levels of target comprehensiveness, from whole-genome collections to focused libraries targeting specific gene families. Whole-genome libraries typically target over 18,000 genes with approximately 73,000 gRNAs, enabling unbiased discovery of novel genes involved in biological pathways and disease development [42]. Focused libraries target specific functional categories, such as:

- Kinase CRISPR Library (822 genes): Targeting kinases involved in signaling cascades with dysregulation linked to disease development [42]

- Transcription Factor CRISPR Library (1,817 genes): Targeting key regulators of gene expression [42]

- Epigenetics CRISPR Library (396 genes): Focusing on epigenetic regulators of gene expression [42]

- Cell Surface Protein CRISPR Library (778 genes): Enabling discovery of receptors and surface markers [42]

These specialized libraries are particularly valuable for developmental models research, where pathway-specific screening can efficiently identify regulators of processes like cell differentiation, pattern formation, and morphogenesis.

Experimental Workflows for CRISPR Screening

Pooled Library Screening Methodology

The standard workflow for pooled CRISPR screening involves multiple sequential steps that must be carefully optimized to ensure successful gene identification:

Workflow Title: Pooled CRISPR Library Screening Process

Generation of Cas9-Expressing Cells: Stable cell lines are established through lentiviral transduction with Cas9-containing vectors followed by blasticidin selection to ensure consistent nuclease expression across the cell population [42].

Library Transduction: Cas9-expressing cells are transduced with the pooled sgRNA library at an appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI, typically ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single gRNA, followed by puromycin selection to eliminate untransduced cells [42].

Selection Phase: The transduced population undergoes selective pressure appropriate for the research question. For positive selection, cells are treated with drugs or other perturbants that favor the survival of specific knockout populations. For negative selection, cells are divided into reference and experimental samples, with selective pressure applied only to the experimental group to identify knockouts that confer sensitivity [42].

Genomic DNA Isolation and Sequencing: Genomic DNA is harvested from surviving cells, and the sgRNA inserts are amplified by PCR. The resulting amplicons are sequenced using NGS platforms to quantify gRNA representation [42].

Hit Identification: Bioinformatics analysis identifies gRNAs significantly enriched or depleted following selection compared to the reference population, indicating genes essential for survival under the experimental conditions [42].

Validation of Editing Efficiency

A critical consideration in CRISPR screening is the validation of editing efficiency, which can vary significantly among gRNAs due to factors including sequence context, chromatin structure, and GC-content [45]. Several methods are available for assessing editing efficiency:

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR Editing Efficiency Validation Methods

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Quantitative Accuracy | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) | Cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA | Low | Inaccurate, especially above 30% editing [45] | Initial low-cost assessment |

| Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) | Decomposes Sanger sequencing traces | Moderate | Moderate (can deviate >10% from NGS in 50% of clones) [45] | Intermediate resource settings |

| Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) | Analyzes Sanger sequencing data with advanced algorithms | High | High (R² = 0.96 vs NGS) [46] | Cost-effective validation with NGS-like accuracy |

| Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Direct sequencing of edited loci | Very high | Gold standard [45] | Definitive validation when resources allow |

Notably, the widely used T7E1 assay demonstrates significant limitations in accurately quantifying editing efficiency. Studies comparing T7E1 with targeted NGS revealed that T7E1 often fails to detect editing in poorly performing sgRNAs (<10% efficiency by NGS) and substantially underestimates efficiency in highly active sgRNAs (>90% by NGS) [45]. Furthermore, sgRNAs with apparently similar activity by T7E1 (~28%) showed dramatically different actual editing efficiencies when assessed by NGS (40% vs. 92%) [45]. These findings underscore the importance of using quantitative validation methods like ICE or targeted NGS for reliable assessment of editing efficiency.

Advanced Applications in Developmental Models Research

Maximizing Phenotype Penetrance in Mosaic Models

In developmental models, particularly non-mammalian vertebrates like Xenopus and zebrafish, CRISPR/Cas9-edited F0 animals often demonstrate variable phenotypic penetrance due to the mosaic nature of editing outcomes after double-strand break repair [47]. Even with high editing efficiency, phenotypes may be obscured by the proportional presence of in-frame mutations that still produce functional protein. Research has shown that the nature of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations depends on local sequence context and can be predicted by computational methods [47].

The InDelphi neural network, trained on mouse embryonic stem cells, accurately predicts CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing outcomes in Xenopus tropicalis, Xenopus laevis, and zebrafish embryos, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.89 between predicted and experimentally observed frameshift frequencies [47]. This predictive capability enables selection of gRNAs with repair outcome signatures enriched toward frameshift mutations, maximizing phenotype penetrance in F0 generation animals—a crucial consideration for efficient functional validation in developmental models.

Workflow Title: Predictive Modeling for Phenotype Penetrance

Deep Learning Approaches for gRNA Optimization

The development of DeepCRISPR represents a significant advancement in computational approaches for gRNA design, unifying sgRNA on-target knockout efficacy and off-target profile prediction into a single deep learning framework [44]. This platform employs a hybrid deep neural network that incorporates both unsupervised pre-training on billions of genome-wide sgRNA sequences and supervised fine-tuning using labeled sgRNAs with known knockout efficacies [44].

DeepCRISPR addresses several challenges in sgRNA design:

- Data heterogeneity: Integration of epigenetic information from different cell types enables more accurate predictions across experimental conditions [44]

- Data sparsity: Data augmentation techniques generate novel sgRNAs with biologically meaningful labels, expanding the effective training set [44]

- Feature identification: Automated learning of sequence and epigenetic features that affect sgRNA efficacy in a data-driven manner [44]

Such computational approaches are particularly valuable for developmental models research, where optimizing gRNA design can significantly enhance the efficiency of functional validation studies.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in CRISPR Screening |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Libraries | LentiArray CRISPR Libraries, LentiPool CRISPR Libraries [42] | Deliver gRNAs for targeted gene knockout in arrayed or pooled formats |

| Cas9 Expression Systems | LentiArray Lentiviral Cas9 Nuclease [42] | Provide consistent Cas9 nuclease expression across cell populations |

| Selection Antibiotics | Blasticidin, Puromycin [42] | Select for successfully transduced cells maintaining Cas9 and gRNA constructs |

| Control Reagents | Positive/Negative Delivery Controls with/without GFP [42] | Optimize delivery conditions and establish hit selection criteria |

| Validation Reagents | T7E1 assay, Sequencing primers [45] | Assess editing efficiency and specificity |

| Computational Tools | DeepCRISPR, InDelphi, ICE, TIDE [47] [46] [44] | Predict editing outcomes, analyze screening data, and design optimal gRNAs |