Harnessing Pluripotency: How Stem Cell Plasticity Drives Advanced Organoid Development for Biomedical Research

This article explores the critical role of the pluripotent state in human stem cells for the successful differentiation of three-dimensional organoids.

Harnessing Pluripotency: How Stem Cell Plasticity Drives Advanced Organoid Development for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of the pluripotent state in human stem cells for the successful differentiation of three-dimensional organoids. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts, methodological applications, and current challenges in the field. We examine how the inherent plasticity of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including both embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells, is harnessed to generate complex, patient-specific tissue models. The content covers the molecular regulation of differentiation, protocols for generating various organoid types, solutions for common pitfalls like heterogeneity and maturation, and a comparative analysis of organoid model validity. By integrating recent advances in single-cell transcriptomics, CRISPR screening, and bioengineering, this article provides a comprehensive resource for leveraging organoid technology in disease modeling, drug screening, and the development of regenerative therapies.

The Blueprint of Life: Understanding Pluripotency and Developmental Principles in Organoid Formation

Pluripotency defines the capacity of a single cell to differentiate into all derivatives of the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—that emerge during embryonic development and ultimately give rise to every cell type in the adult organism [1]. This remarkable biological potential forms the cornerstone of developmental biology and regenerative medicine. Two primary cell types exemplify this state: embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). ESCs are derived from the inner cell mass of blastocyst-stage embryos, possessing inherent pluripotency and near-unlimited self-renewal capacity in vitro [2] [3]. In contrast, iPSCs are artificially generated through the reprogramming of somatic cells, reverting them to a pluripotent state through the introduction of specific transcription factors [1] [4]. The discovery of iPSCs in 2006 by Takahashi and Yamanaka represented a paradigm shift, creating new possibilities for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative therapies while circumventing the ethical concerns associated with human embryos [1] [4] [2].

Within organoid differentiation research, understanding the nuances of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) is fundamental. Organoids are three-dimensional, miniaturized, and simplified versions of organs generated in vitro that mimic the complex architecture and functionality of human tissues [5] [6]. PSC-derived organoids are generated by applying developmental biological principles to ESCs or iPSCs, guiding them through processes of directed differentiation and morphogenesis that resemble in vivo organogenesis [5] [7]. The application of signaling pathways that govern embryonic development—including Wnt, FGF, TGFβ/BMP, and retinoic acid—enables researchers to direct PSC differentiation toward specific organ fates, resulting in organoids with remarkable cell type complexity, architecture, and function similar to their in vivo counterparts [5]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of ESCs and iPSCs, their molecular definitions, and their crucial role as starting materials in advanced organoid research.

Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs): The Gold Standard of Pluripotency

Origin and Characteristics

ESCs are pluripotent cells derived from the inner cell mass of blastocyst-stage embryos [2] [3]. First isolated from mice in 1981 and later from humans in 1998, ESCs represent the reference standard for pluripotency due to their biological origin [1] [2]. Human ESCs (hESCs) typically exist in a "primed" state of pluripotency, characterized by flat colony morphology, dependence on TGFβ/activin/nodal signaling, and limited single-cell clonogenicity [3]. In contrast, mouse ESCs (mESCs) reside in a "naive" pluripotent state, exhibiting domed colonies, increased single-cell survival, and dependence on JAK/STAT signaling [3]. The conversion of primed hESCs to a naive state has been achieved through various culture conditions, resulting in domed colony morphology, enhanced single-cell clonogenicity, and faster doubling times [3].

Molecular Signature

The molecular signature of ESCs is defined by the core transcription factor network that maintains pluripotency, consisting primarily of OCT4 (POU5F1), SOX2, and NANOG [2]. These factors operate in a self-reinforcing regulatory circuit that activates genes responsible for pluripotency while suppressing those involved in differentiation. Additional markers characterizing ESC identity include REX1, KLF2, KLF4, and PRDM14 [3]. ESCs also express specific surface markers such as SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81, which are used for identification and purification [2]. The maintenance of ESC pluripotency depends on specific signaling pathways, with hESCs requiring TGFβ/activin/nodal signaling alongside FGF2, while mESCs rely on LIF/STAT3 signaling and BMP inhibition [3].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Embryonic Stem Cells

| Characteristic | Description | Technical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner cell mass of blastocyst-stage embryos | Derived from donated embryos under informed consent |

| Pluripotency State | Primed (hESCs) or naive (mESCs) | Naive state conversion enables enhanced differentiation |

| Key Transcription Factors | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | Core pluripotency network maintenance |

| Surface Markers | SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 | Identification and purification standards |

| Signaling Dependencies | TGFβ/activin/nodal (hESC), LIF/STAT3 (mESC) | Culture medium formulation |

| Differentiation Potential | All three germ layers in vitro and in vivo | Teratoma formation assays, directed differentiation |

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): Reprogrammed Pluripotency

Historical Development and Reprogramming Mechanisms

The foundation for iPSC technology was established by John Gurdon's pioneering somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in 1962, which demonstrated that a nucleus from a differentiated somatic cell could be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state when transferred into an enucleated egg [1] [4]. This revealed that genetic information remains intact during differentiation and that epigenetic modifications governing cell fate are reversible. In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka identified a combination of four transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM)—that could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into iPSCs [1] [4] [8]. The following year, this approach was successfully applied to human fibroblasts, using either the OSKM factors or an alternative combination (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) reported by Thomson's group [1] [8].

The molecular reprogramming process occurs in two broad phases [1]. The early phase involves stochastic silencing of somatic genes and activation of early pluripotency-associated genes, characterized by inefficient access of exogenous transcription factors to closed chromatin regions. The late phase is more deterministic, involving activation of late pluripotency-associated genes and establishment of a self-reinforcing pluripotency network. Throughout this process, cells undergo profound remodeling of chromatin structure, epigenome, metabolism, cell signaling, and proteostasis [1] [4]. A critical event in fibroblast reprogramming is mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), which is essential for establishing the epithelial characteristics of pluripotent cells [1].

Reprogramming Methods and Optimization

Multiple methods have been developed to deliver reprogramming factors into somatic cells, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: iPSC Reprogramming Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration | Efficiency | Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | RNA genome | Yes (random) | Moderate | Lower (insertional mutagenesis) |

| Lentivirus | RNA genome | Yes (random) | High | Lower (insertional mutagenesis) |

| Sendai Virus | RNA genome | No | High | Higher (cytoplasmic RNA virus) |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No (transient) | Low to moderate | Higher |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | Moderate | Higher (immunogenic considerations) |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Low | Highest |

Efforts to optimize reprogramming have focused on improving efficiency and safety. The original OSKM combination has been modified by substituting potentially oncogenic factors like c-MYC with safer alternatives such as L-MYC or GLIS1 [8]. Small molecules that modulate epigenetic states—including histone deacetylase inhibitors (valproic acid), DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, and TGF-β pathway inhibitors—significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency [8]. The development of fully chemical reprogramming methods using defined small molecule combinations represents a breakthrough for generating footprint-free iPSCs without genetic manipulation [1] [8].

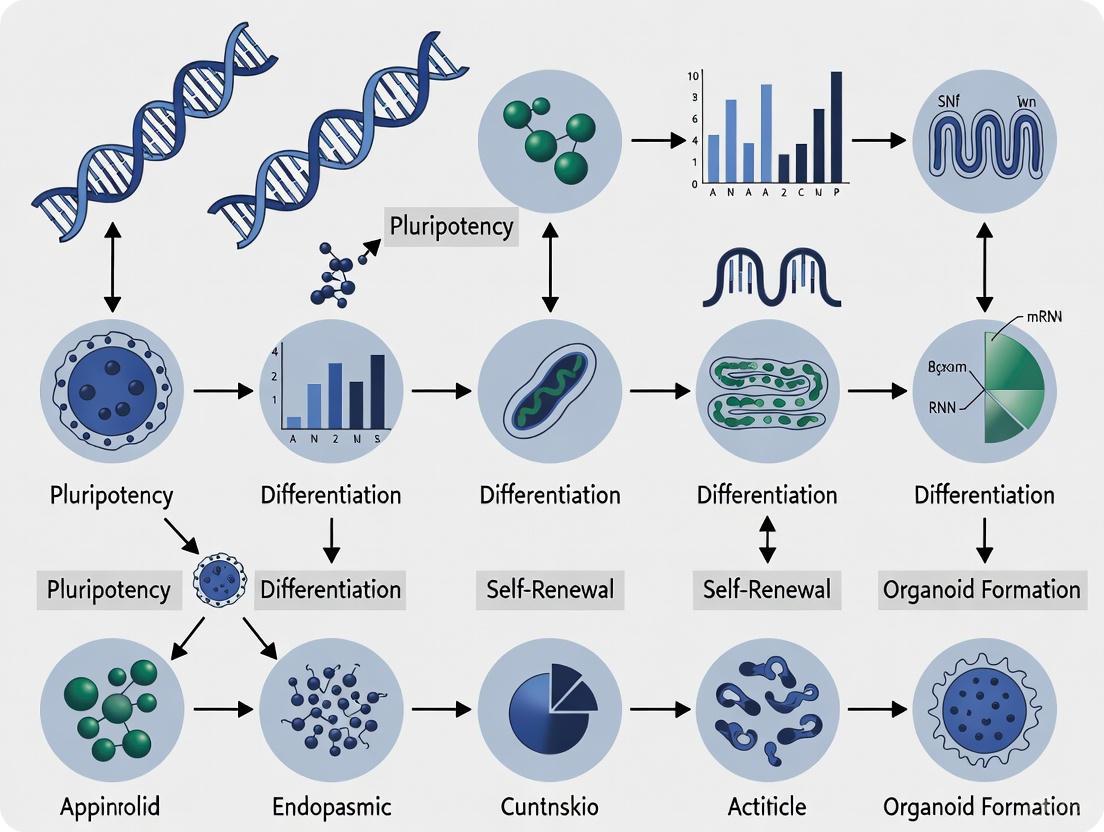

Diagram 1: iPSC Reprogramming Phases. The reprogramming process transitions from an initial stochastic phase to a deterministic phase, establishing stable pluripotency.

Comparative Analysis: ESCs vs. iPSCs in Research Applications

Molecular and Functional Equivalence

Comprehensive comparisons between ESCs and iPSCs have revealed both similarities and important differences. Multiple studies demonstrate that thoroughly reprogrammed iPSCs can achieve a state of pluripotency that closely resembles that of ESCs, with comparable differentiation potential toward all three germ layers [9] [10]. However, persistent molecular differences have been observed, including aberrant epigenetic patterns in some iPSC lines, such as abnormal methylation at the DLK1-DIO3 imprinted locus [10]. The reprogramming process can also introduce genetic and epigenetic abnormalities, including copy number variations and residual epigenetic memory of the somatic cell origin, which may influence differentiation preferences [9] [1].

Table 3: Functional Comparison of ESCs and iPSCs in Disease Modeling

| Disease Model | ESC-Based Approach | iPSC-Based Approach | Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy | Knockdown of SMN in ESCs [9] | iPSCs derived from patients [9] | Similar disease-related phenotypes observed in both models |

| Long QT Syndrome | Gene targeting in ESCs [9] | iPSCs derived from patients [9] | Comparable disease modeling capabilities |

| Fragile X Syndrome | Mutant ESCs from PGD embryos [9] | iPSCs derived from patients [9] | Both successfully model the disorder |

| Turner Syndrome | Screening for XO ESC colonies [9] | iPSCs from Turner patients [9] | ESCs better model early embryonic lethality |

| Fanconi Anemia | Knockdown of FANCA/FANCD2 [9] | iPSCs from patients [9] | Reprogramming efficiency affected by genetic background |

Advantages and Limitations for Research

Both cell types present distinct advantages and limitations for research applications. ESCs offer a gold standard for pluripotency with established differentiation protocols and typically stable epigenetic profiles [3]. However, their use involves ethical considerations regarding embryo destruction, and their allogeneic nature presents immune compatibility challenges for transplantation [2] [10]. iPSCs overcome these ethical constraints and enable the generation of autologous cell therapies with perfect immune matching [1] [2]. They also facilitate the development of patient-specific disease models, particularly for genetic disorders [9] [1]. However, iPSCs face challenges including potential tumorigenicity due to reprogramming factor integration, epigenetic abnormalities that may affect functionality, and more variable differentiation efficiency compared to ESCs [9] [2].

Pluripotent Stem Cell Differentiation: Principles and Protocols

Developmental Principles Guiding Differentiation

The differentiation of PSCs into specific lineages recapitulates embryonic development through the sequential application of signaling pathways that govern germ layer formation, patterning, and organ induction [5]. The same small number of signaling pathways—Wnt, FGF, TGFβ/BMP, and retinoic acid—can generate diverse tissues through variations in timing, concentration, and combination [5]. During in vitro differentiation, PSCs first undergo specification into one of the three germ layers. For neuroectoderm formation, dual SMAD inhibition (repressing BMP and TGFβ signaling) promotes neural induction [5] [6]. For definitive endoderm formation, high activin A (a Nodal mimetic) concentration combined with Wnt activation drives efficient specification [5]. Mesoderm formation requires precise Wnt and FGF signaling modulation, with specific timing determining anterior-posterior patterning [5].

Diagram 2: PSC Differentiation Signaling. Developmental signaling pathways guide PSCs through germ layer specification to functional organoids.

Neural Organoid Differentiation Protocol

The generation of neural organoids from PSCs follows a standardized workflow that exemplifies the application of developmental principles [6]:

ESC/iPSC Culture Maintenance: PSCs are maintained in feeder-free conditions using defined media such as StemFlex Medium on matrix-coated plates (e.g., Geltrex). Cells are passaged using gentle dissociation reagents like Versene or Accutase [6].

Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: PSCs are dissociated into single cells and seeded in low-attachment U-bottom plates (e.g., Nunclon Sphera) at defined densities (6-9×10³ cells/well) in media supplemented with ROCK inhibitor (RevitaCell) to enhance survival and aggregation. EBs form within 24 hours and are cultured for 3-4 days with medium changes every other day [6].

Neural Induction: EBs are transferred to neural induction medium composed of DMEM/F-12 with N-2 supplement. This medium is changed every other day for 8-9 days until EBs display a characteristic bright "ring" of neuroepithelium surrounding a darker center [6].

Matrix Embedding and Patterning: Neural-induced EBs are individually encapsulated in Geltrex matrix droplets and transferred to differentiation medium containing DMEM/F-12 and Neurobasal Medium supplemented with N-2 and B-27 supplements. The matrix provides a 3D environment that supports complex morphogenesis [6].

Growth and Maturation: Embedded organoids are transferred to an orbital shaker system for enhanced nutrient exchange and cultured for extended periods (weeks to months) in maturation medium containing B-27 Supplement with vitamin A. Medium is changed every 2-3 days, with organoids developing complex neural structures over time [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Pluripotent Stem Cell and Organoid Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC/L-MYC, NANOG, LIN28 | Induction of pluripotency | Multiple combinations possible; safety optimized versions available |

| Culture Matrices | Geltrex, Matrigel, Laminin-521 | Extracellular matrix support | Critical for 3D culture and organoid formation |

| Pluripotency Media | mTeSR, StemFlex, Essential 8 | Maintenance of undifferentiated state | Defined, xeno-free formulations preferred |

| Differentiation Media Supplements | N-2 Supplement, B-27 Supplement | Neural lineage specification | B-27 without vitamin A for induction, with vitamin A for maturation |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Dorsomorphin (BMP inhibitor), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), CHIR99021 (Wnt activator) | Pathway modulation for directed differentiation | Used for germ layer specification and patterning |

| Dissociation Reagents | Accutase, TrypLE Select, Versene | Gentle cell dissociation | Preserve viability for passaging and EB formation |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Y-27632, RevitaCell | Enhances single-cell survival | Critical for cloning, thawing, and reprogramming |

| Characterization Antibodies | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 | Pluripotency verification | Essential for quality control |

The definitions of pluripotency embodied by ESCs and iPSCs have fundamentally transformed biomedical research, particularly in the advancing field of organoid technology. While ESCs continue to serve as a crucial reference standard, iPSCs offer unprecedented opportunities for personalized disease modeling and drug development. The ongoing refinement of reprogramming methods—including the development of non-integrating delivery systems and fully chemical reprogramming—continues to enhance the safety and applicability of iPSCs [1] [8]. Current research focuses on addressing the remaining challenges, including the functional equivalence between ESC- and iPSC-derived cell types, the elimination of tumorigenic risk, and the improvement of differentiation efficiency and maturation [2] [10]. As organoid protocols become more sophisticated, incorporating multiple cell types and achieving greater architectural and functional complexity, the role of well-characterized pluripotent stem cells as starting materials becomes increasingly critical. The continued interrogation of pluripotency mechanisms will undoubtedly yield next-generation models that more faithfully recapitulate human development and disease, accelerating both fundamental discoveries and therapeutic applications.

The remarkable capacity of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) to both self-renew indefinitely and differentiate into any somatic cell type is governed by an intricate molecular circuitry. At the heart of this circuitry lies a core transcriptional network, predominantly featuring the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, which operates in concert with dynamic epigenetic mechanisms to maintain cellular identity or direct fate transitions [11] [12]. Understanding this core machinery is not merely a fundamental pursuit in developmental biology but is also critical for advancing organoid differentiation research. Organoids—three-dimensional, self-organizing tissue models derived from stem cells—have emerged as powerful tools for studying human development, disease modeling, and drug screening [7]. The fidelity of these organoids in recapitulating in vivo tissue complexity is fundamentally dependent on the precise manipulation and understanding of the pluripotency network that guides their initial formation and patterning [13] [14]. This technical guide delves into the components, interactions, and regulatory dynamics of the core molecular machinery governing pluripotency, with a specific focus on its implications for organoid research.

The Core Pluripotency Transcription Factor Network

Key Transcription Factors and Their Hierarchical Relationships

The core pluripotency network is orchestrated by a limited set of transcription factors that establish autoregulatory and feed-forward loops to stabilize the pluripotent state. OCT4 (encoded by POU5F1), a POU-family transcription factor, is a master regulator essential for establishing and maintaining pluripotency. Its dosage is critical; even slight deviations can precipitate differentiation into trophectoderm or primitive endoderm lineages [12] [15]. SOX2, an SRY-related HMG-box factor, acts as a crucial transcriptional partner for OCT4. The two factors co-occupy regulatory elements of numerous target genes, forming heterodimers to regulate expression of key pluripotency genes, including NANOG, FGF4, and LEFTY [12] [15]. NANOG, a homeodomain transcription factor, reinforces the pluripotent state by promoting self-renewal and alleviating dependency on external signals like LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) [12] [15].

Global mapping studies using techniques like bioChIP-Chip have revealed that these core factors do not operate in isolation. They are part of an extended network that includes other critical factors such as KLF4, c-MYC, DAX1, REX1, and ZPF281 [12]. This network exhibits a distinct hierarchy. KLF4, for instance, appears to lie upstream of feed-forward circuits involving OCT4 and SOX2, while c-MYC regulates a broad set of targets involved in metabolism and proliferation, distinguishing it from the more lineage-specific functions of other factors [12]. A key organizational principle is that promoters bound by multiple transcription factors (>4) tend to be highly active in PSCs and are repressed upon differentiation, whereas those bound by fewer factors are often already repressed in the pluripotent state [12].

Table 1: Core Pluripotency Transcription Factors and Their Functions

| Transcription Factor | Gene | Protein Family | Primary Function in Pluripotency | Consequence of Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | POU5F1 | POU-domain | Master regulator; essential for establishing and maintaining pluripotency | Loss of inner cell mass; differentiation/trophectoderm bias |

| SOX2 | SOX2 | HMG-box | Transcriptional partner for OCT4; regulates key pluripotency genes | Embryo lethality; loss of pluripotency |

| NANOG | NANOG | Homeodomain | Promotes self-renewal; alleviates LIF dependency | Failure to maintain pluripotency; primitive endoderm differentiation |

| KLF4 | KLF4 | Krüppel-like factor | Activates NANOG; part of reprogramming cassette | Impaired reprogramming and self-renewal |

| c-MYC | MYC | bHLH-ZIP | Regulates metabolism and proliferation; enhances reprogramming efficiency | Reduced reprogramming efficiency; growth defects |

Spatial Organization and Dynamics in the Nucleus

The functional output of the core transcription factors is not solely determined by their expression levels but also by their spatial organization and dynamic interactions within the nucleus. Advanced live-cell imaging techniques have revealed that OCT4 and SOX2 are not uniformly distributed in the nucleoplasm of embryonic stem cells (ESCs). Instead, they partition between the nucleoplasm and distinct, brighter foci that colocalize with regions of condensed chromatin [16]. These foci are thought to represent biomolecular condensates, potentially formed through liquid-liquid phase separation, which may concentrate transcription-related machinery to modulate gene expression [16] [16].

This spatial organization is highly dynamic and responds to differentiation cues. Upon induction of differentiation by 2i/LIF withdrawal, OCT4 undergoes a significant reorganization within 12-24 hours, preceding its downregulation. This is characterized by an increase in the coefficient of variation of its nuclear distribution, the mean number of bright foci per nucleus, and their relative intensity [16]. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) further showed that differentiation triggers distinct changes in OCT4 and SOX2 dynamics, with a specific impairment of longer-lived OCT4-chromatin interactions [16]. This early dynamical reorganization represents a potential mechanism for rapidly modulating the transcriptional activity of these factors at the onset of differentiation, a critical consideration for initiating organoid formation.

Figure 1: Core Pluripotency Transcription Factor Network. The diagram illustrates the hierarchical and interconnected relationships between key transcription factors, including autoregulatory (OCT4-SOX2) and feed-forward loops (KLF4 to OCT4/SOX2/NANOG). c-MYC operates in a broader, parallel pathway.

Epigenetic Regulation of Pluripotency

Histone Modifications and Chromatin States

The transcriptional network is deeply intertwined with the epigenetic landscape, which governs chromatin accessibility and defines gene expression potential. In PSCs, a unique configuration of histone modifications helps maintain a plastic state poised for multi-lineage differentiation. A hallmark of pluripotency is the presence of bivalent chromatin domains, where promoters of key developmental genes simultaneously carry the activating mark H3K4me3 and the repressive mark H3K27me3 [11] [12]. This paradoxical modification poises these genes for rapid activation or further repression upon receiving differentiation signals, allowing for timely lineage commitment [11].

The balance of activating and repressive marks is tightly controlled. H3K4me3 at the promoters of genes like OCT4 and SOX2 maintains an open chromatin state conducive to active transcription [11]. The Set1/COMPASS complex, responsible for this methylation, is upregulated during the establishment of pluripotency [11]. Conversely, the repressive mark H3K27me3 is deposited by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) and is vital for silencing developmental genes that promote differentiation, such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) [11]. Activating histone acetylation marks, such as H3K9ac and H3K27ac, are also essential for maintaining an open chromatin configuration and are dynamically regulated during differentiation by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [11].

Table 2: Key Histone Modifications in Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Histone Modification | Type | Enzyme(s) | Function in PSCs | Role in Differentiation/Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Activating | Set1/COMPASS | Marks promoters of actively transcribed pluripotency genes (OCT4, SOX2) | Maintains open chromatin at core network genes |

| H3K27me3 | Repressive | PRC2 (EZH2) | Silences developmental/differentiation genes; part of bivalent domains | Must be removed for activation of lineage-specific genes |

| H3K9me3 | Repressive | SUV39H1 | Associated with heterochromatin and gene repression | Abundant in somatic cells; removal by KDM4B is essential for reprogramming |

| H3K27ac | Activating | p300/CBP | Marks active enhancers | Crucial for activating genes during lineage commitment |

| H3K9ac | Activating | p300/CBP | Associated with active transcription | Facilitates open chromatin during reprogramming |

Epigenetic Dynamics in Differentiation and Reprogramming

During the reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the epigenetic landscape must be radically reset from a differentiated to a pluripotent state. This involves the erasure of repressive marks characteristic of somatic cell memory, such as H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, and the establishment of an activating chromatin state at pluripotency gene promoters [11]. Enzymes like the H3K9me3 demethylase KDM4B and the H3K27me3 demethylase UTX play critical roles in this process by removing repressive marks from the promoters of genes like NANOG, thereby initiating and facilitating reprogramming [11].

The manipulation of epigenetic modifiers can significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency. The use of HDAC inhibitors, such as valproic acid (VPA), increases the efficiency of iPSC generation by preventing the removal of acetyl groups, thereby maintaining a more open chromatin structure that is favorable for the activation of pluripotency genes like MYC [11]. Recent single-cell epigenomic analyses of human neural organoid development have further underscored that epigenetic regulation, particularly the installation of activating histone marks, often precedes the activation of groups of neuronal genes, highlighting the instructive role of the epigenome in guiding lineage-specific differentiation trajectories [17].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating the Core Machinery

Genome-Wide Mapping of Transcription Factor Occupancy

Identifying the genomic binding sites of pluripotency transcription factors is essential for deciphering the regulatory network. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by microarray hybridization (ChIP-Chip) or sequencing (ChIP-Seq) are standard methodologies. An alternative, powerful approach is biotin-mediated ChIP (bioChIP) [12].

Protocol: bioChIP-Chip for Global Target Mapping [12]

- Cell Line Engineering: Generate mouse ES cell lines expressing a biotin-tagged version of the transcription factor of interest (e.g., Nanog, c-Myc) using a lentiviral system.

- Cross-linking and Lysis: Cross-link cells with formaldehyde to covalently bind proteins to DNA. Lyse cells and shear chromatin by sonication to fragments of 200-1000 bp.

- Biotin-Affinity Capture: Incubate the sheared chromatin with streptavidin-coated beads. The biotin-tagged transcription factor and its bound DNA fragments will be captured.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the protein-DNA complexes and reverse the cross-links.

- DNA Purification and Amplification: Purify the enriched DNA and amplify it if necessary.

- Microarray Hybridization and Analysis: Label the purified DNA and hybridize it to a promoter tiling microarray. Compare the signal to a reference input DNA sample to identify statistically significant regions of transcription factor occupancy.

This method circumvents the need for ChIP-quality antibodies and has been shown to be highly comparable to conventional ChIP, with a correlation of 0.896 for Nanog targets [12].

Analyzing Transcription Factor Dynamics in Live Cells

To probe the dynamic behavior and spatial organization of core factors in living cells, as described in Section 2.2, advanced microscopy techniques are required.

Protocol: Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) and Live-Cell Imaging of OCT4/SOX2 [16]

- Cell Line Generation: Establish ES cell lines with doxycycline-inducible expression of OCT4 or SOX2 fused to a fluorescent protein (e.g., YPet). Validate that the fusion proteins function similarly to endogenous proteins and do not alter pluripotency markers.

- Differentiation Induction: Induce differentiation by withdrawing 2i/LIF from the culture medium. For controls, maintain cells in self-renewing conditions.

- Confocal Imaging: At various time points (e.g., 0, 12, 24, 48h post-differentiation), acquire high-resolution confocal images of live cells. Quantify the distribution of the TFs by measuring the coefficient of variation (CV) of fluorescence intensity across the nucleus, the number of bright foci per nucleus (NTF), and their intensity relative to the nucleoplasm (ITF/Inucleus).

- FCS Measurements: Perform FCS on the nucleoplasm of live cells. This technique analyzes the fluctuations in fluorescence intensity within a very small volume to extract parameters such as diffusion coefficients and binding kinetics. This can reveal changes in TF-chromatin interaction dynamics upon differentiation induction.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing TF Dynamics. The diagram outlines the key steps for investigating the reorganization and interaction dynamics of transcription factors like OCT4 and SOX2 during early differentiation using live-cell imaging and FCS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pluripotency Studies

| Reagent / Model System | Function/Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline-Inducible TF-YPet ES Cell Lines | Controlled expression of fluorescently tagged TFs for live-cell imaging and dynamics studies | Studying OCT4/SOX2 nuclear reorganization during early differentiation [16] |

| bioChIP-Chip Platform | Genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding sites without need for specific antibodies | Identifying global targets of an expanded set of 9 pluripotency factors in mESCs [12] |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Valproic Acid) | Promotes open chromatin state by inhibiting histone deacetylase activity | Enhancing reprogramming efficiency of somatic cells to iPSCs [11] |

| Microfluidic Droplet Culture Systems | 3D culture of PSCs in confined volumes to modulate cell fate via enhanced autocrine/paracrine signaling | Regulating differentiation and tissue patterning in gastruloids and cardiac organoids [14] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-specific pluripotent cells for disease modeling and differentiation studies | Differentiating into insulin-producing β-cells for diabetes research and drug screening [18] |

| Directed Differentiation Oligodendrocyte Protocol | Forced expression of transcription factors (SOX10, OLIG2, NKX6.2) to direct cell fate | Generating oligodendroglial cells within human neural progenitor cells and organoids [13] |

Implications for Organoid Differentiation Research

The precise manipulation of the core pluripotency machinery is fundamental to the burgeoning field of organoid research. The transition from a pluripotent state to a structured, tissue-like organoid requires the controlled dissolution of the core network and the activation of specific differentiation programs. Understanding the dynamical reorganization of factors like OCT4 and SOX2 [16] provides a temporal guide for when and how to introduce patterning cues. Furthermore, the knowledge of epigenetic landscapes, such as the presence of bivalent domains, helps predict which lineage-specific genes are primed for activation and can be leveraged to direct organoid differentiation along desired paths [11] [17].

Novel culture technologies, such as microfluidic droplet systems, are enhancing our ability to control this process. Confining PSCs in microscale droplets accelerates the accumulation of autocrine and paracrine signaling molecules, which in turn regulates fate decisions and promotes the self-organization and tissue patterning observed in advanced models like gastruloids and cardioids [14]. This is particularly relevant for modeling complex diseases, as demonstrated by the use of iPSC-derived organoids to study the role of TCF4 haploinsufficiency in oligodendroglial differentiation deficits associated with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome [13]. As organoid protocols become more sophisticated, integrating a deeper understanding of the underlying transcriptional and epigenetic logic will be paramount for increasing their fidelity, reproducibility, and utility in both basic research and clinical applications.

Organoid biology represents a paradigm shift in developmental biology, moving beyond the classical notion of positional information towards a model of genetically encoded self-assembly. This process involves genetic programs that contain cell-autonomous instructions as well as signalling events which can induce emergent properties, enabling unpatterned stem cells to develop into complex three-dimensional structures [19]. The foundation of organoid technology lies in leveraging the inherent pluripotency of stem cells—their capacity to differentiate into any cell type—and guiding this potential through the sequential activation of developmental pathways that mimic embryonicogenesis [5] [20].

The core premise is that pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), possess the developmental blueprint to reconstruct organ-like structures when provided with appropriate environmental cues [5]. This process does not rely exclusively on "self-organization" in the pure physical sense, but rather on the execution of genetic programs scripted within the genome that direct temporal sequences of changes in cell state [19]. By recapitulating the signaling milieu of early embryonic development, researchers can essentially "coax" stem cells to reactivate these intrinsic developmental programs, resulting in the emergence of organoids with remarkable architectural and functional similarity to their in vivo counterparts [5] [21].

Developmental Principles Guiding Organoid Formation

Core Signaling Pathways in Embryonic Patterning

The transformation from pluripotent stem cells to complex organoids is governed by the precise manipulation of a surprisingly small number of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. These pathways—Wnt, FGF, TGF-β/BMP, Retinoic Acid (RA), and Nodal—act as the morphogenetic language that directs germ layer formation, anterior-posterior patterning, and organ induction [5]. The remarkable diversity of tissues generated from these common pathways arises from differences in the timing, dose, and combination of signaling activities [5].

In embryonic development, these pathways create concentration gradients that provide positional information to cells. Organoid culture replicates this principle by applying specific combinations and concentrations of growth factors and small molecule inhibitors at defined time points, effectively "instructing" cells to adopt particular regional identities [5]. For instance, activation of Wnt and FGF signaling promotes posterior fates, while their inhibition favors anterior identities [5].

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Organoid Patterning

| Signaling Pathway | Primary Role in Development | Common Manipulations in Organoid Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Posterior patterning, stem cell maintenance | Wnt agonists (CHIR99021), R-spondin, Wnt3A-conditioned media |

| FGF | Mesendoderm formation, proliferation | FGF2, FGF4, FGF7, FGF10 |

| TGF-β/BMP | Mesoderm/endoderm specification, dorsoventral patterning | Activin A (Nodal mimetic), BMP4, A83-01 (inhibitor) |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Anterior-posterior patterning, neuronal differentiation | All-trans retinoic acid |

| Hedgehog | Tissue patterning, morphogenesis | Smoothened agonist (SAG), Purmorphamine |

From Pluripotency to Regional Identity: The Role of Germ Layer Patterning

The journey from pluripotent stem cells to organoids begins with the specification of germ layer identity, recapitulating the fundamental process of gastrulation. During gastrulation, the migration of epiblast cells through the primitive streak segregates the mesoderm and endoderm from the ectoderm, with Nodal signaling playing a crucial role in mesoderm and endoderm formation [5]. In organoid culture, this process is modeled using specific growth factors and small molecules that steer cells toward the desired germ layer.

For neuroectoderm formation, which gives rise to cerebral and retinal organoids, PSCs are typically cultured in minimal media with small-molecule inhibition of Wnt and TGF-β/Smad signaling [5]. This approach mirrors the natural repression of these pathways in the anterior epiblast during embryonic development. A key methodological innovation for efficient neural induction was developed by Yoshiki Sasai's group, who established that dissociating PSCs to dilute all endogenous signals and allowing them to reaggregate in suspension under Wnt inhibition promotes neural progenitor differentiation [5].

In contrast, definitive endoderm formation is induced through activation of Nodal and Wnt signaling, mirroring their essential role in posterior epiblast patterning during embryonic gastrulation [5]. Human PSCs can be directed to adopt a mesendodermal fate by exposure to activin A (a Nodal mimetic), with longer exposure to high levels driving the formation of definitive endoderm [5]. This definitive endoderm can then be further patterned along the anterior-posterior axis through manipulation of Wnt, FGF, RA, and TGF-β/BMP signaling to generate organoids representing different regions of the digestive and respiratory tracts [5].

Experimental Methodologies for Organoid Generation

Establishing the Foundation: 3D Culture Matrices and Initial Setup

The transition from two-dimensional to three-dimensional culture is fundamental to organoid development, as it enables the spatial organization and cell-cell interactions necessary for morphogenesis. The extracellular matrix (ECM) serves as a critical scaffold that provides not only structural support but also biochemical and biophysical cues that guide cell behavior [22]. Matrigel, a basement membrane extract derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm murine sarcoma, is the most widely used matrix for organoid culture, although defined synthetic matrices are increasingly available [22] [21].

The basic protocol for establishing organoid cultures involves embedding stem cells or tissue fragments within a liquid ECM, which is dispensed as small droplets onto tissue culture surfaces. After incubation at 37°C, the ECM solidifies into gel "domes" that are then overlaid with tissue-specific culture medium [22]. This 3D environment allows cells to interact in all directions and self-organize into complex structures that more closely mimic in vivo architecture than traditional 2D cultures.

Table 2: Core Materials for Organoid Culture

| Material/Reagent | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Basement Membrane Matrix | Provides 3D scaffold, biochemical cues | Matrigel (Corning), Cultrex BME, synthetic hydrogels |

| Pluripotent Stem Cells | Starting cellular material with differentiation potential | Human ESCs, iPSCs |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Enhances single-cell survival after passaging | Y-27632 |

| Advanced Media Base | Nutrient foundation for culture | Advanced DMEM/F-12 |

| Niche Factors | Mimic stem cell niche signaling | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, Wnt3A |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Precisely control signaling pathways | A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), SB202190 (p38 inhibitor) |

Tissue-Specific Differentiation Protocols

Cerebral Organoids

The generation of cerebral organoids follows a minimally guided approach that leverages the innate self-organization capacity of neural progenitors. The protocol begins with the formation of embryoid bodies from PSCs using methods such as SFEBq (serum-free floating culture of embryoid body-like aggregates with quick reaggregation) in low-adhesion U-bottomed plates [19]. These aggregates are then transferred to 3D suspension in Matrigel and cultured with orbital shaking to enhance nutrient exchange [5]. A defining feature of cerebral organoid differentiation is the initial absence of inductive signals to promote default neural induction, followed by the emergence of regional identities that can be enhanced through the addition of patterning factors like retinoic acid [5].

Intestinal Organoids

Intestinal organoids can be generated through two distinct approaches: from tissue-resident stem cells or through directed differentiation of PSCs. For tissue-derived intestinal organoids, single Lgr5+ stem cells isolated from crypts are embedded in Matrigel and cultured with a defined medium containing EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin to recreate the intestinal stem cell niche in vitro [23]. These organoids typically show budding morphologies and contain all the major cell types of the intestinal epithelium.

For PSC-derived intestinal organoids, a stepwise differentiation approach is employed beginning with definitive endoderm induction using activin A, followed by mid/hindgut patterning through activation of Wnt and FGF signaling [5]. The resulting hindgut spheroids are then embedded in Matrigel and cultured with intestinal growth factors to promote 3D organization into organoids with crypt-villus structures [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful organoid culture requires careful selection and combination of research reagents that collectively recreate the appropriate developmental microenvironment. The table below details critical components and their functions in supporting organoid formation and maturation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Organoid Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel (Corning), Cultrex BME, synthetic PEG hydrogels | Provides 3D scaffolding, mechanical cues, and basement membrane components |

| Growth Factors | EGF, FGF families, Noggin, R-spondin, BMP4, Wnt3A | Activates specific signaling pathways for patterning and differentiation |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Precisely controls signaling pathway activity; enhances cell survival |

| Media Supplements | B-27, N-2, N-acetylcysteine, Nicotinamide | Provides essential nutrients, antioxidants, and survival factors |

| Conditioned Media | Wnt3A-conditioned media, R-spondin-conditioned media | Source of difficult-to-purify signaling proteins |

| Dissociation Reagents | Accutase, TrypLE, collagenase | Gentle enzymatic dissociation for organoid passaging |

Current Limitations and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, organoid technology faces several challenges that impact its utility and reproducibility. A primary limitation is incomplete maturation, with many organoids retaining a fetal phenotype rather than achieving full adult characteristics [24] [23]. Additionally, most organoid systems lack vascularization, which limits nutrient diffusion and organoid size, often resulting in necrotic cores [24]. The absence of immune cells, neural innervation, and stromal components in many current models further reduces physiological relevance [23].

There is also considerable batch-to-batch variability in both starting materials (e.g., Matrigel) and resulting organoids, posing challenges for standardization and reproducibility [23]. Furthermore, the cellular complexity of PSC-derived organoids does not always match that of their in vivo counterparts, with certain cell types often underrepresented or missing entirely [23].

Future directions in organoid technology focus on addressing these limitations through engineered microenvironments, vascularization strategies, and multi-tissue integration. The integration of organoids with organ-on-chip platforms provides dynamic fluid flow and mechanical cues that enhance cellular differentiation and function [24]. Efforts to create assembloids—by combining organoids representing different tissue regions—aim to reconstruct more complex tissue interactions [24]. Additionally, automation and AI-assisted culture monitoring are being implemented to improve reproducibility and enable high-throughput screening applications [24] [20].

As these technologies mature, organoids are poised to become increasingly powerful tools for studying human development, disease modeling, drug screening, and personalized medicine, ultimately reducing our reliance on animal models and providing more human-relevant biological insights [20].

The formation of a primitive streak-like signature represents a pivotal commitment in the differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into organized, three-dimensional organoids. This in-depth technical guide explores the role of the primitive streak as a gateway to definitive endoderm specification, framing this process within the broader context of stem cell pluripotency state and its impact on differentiation efficacy. We synthesize current research and experimental data to provide researchers and drug development professionals with actionable methodologies and analytical frameworks for optimizing germ layer induction, with a particular emphasis on the transcription factor MIXL1 as a critical marker and regulator of lineage propensity.

The Primitive Streak: Gateway to Germ Layer Specification

In embryonic development, the primitive streak is the transient structure through which pluripotent epiblast cells undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and ingress to form the definitive endoderm and mesoderm. Recapitulating this event in vitro is crucial for directing hPSCs toward spatially organized tissues. The differentiation propensity of hPSCs, including their efficiency in forming primitive streak-like cells, is not uniform; it is influenced by the stem cell's specific pluripotency state, genetic background, and epigenetic memory [20]. This inherent heterogeneity presents a significant challenge for the reproducible generation of high-quality organoids for research and therapeutic applications [25].

Recent studies have demonstrated that the early activation of key genetic markers during this primitive streak-like stage is a strong predictor of successful differentiation into advanced endoderm derivatives, including hepatic and intestinal organoids. Understanding and controlling this initial step is therefore fundamental to the entire paradigm of stem cell-based disease modeling and drug development [20].

MIXL1 as a Key Regulator of Endoderm Propensity

Functional Role of MIXL1

The mesendoderm transcription factor MIXL1 has been identified as a master regulator of definitive endoderm (DE) differentiation. In the early mouse embryo, Mixl1 is expressed in the primitive streak and nascent mesoderm, and its loss of function leads to deficiencies in definitive endoderm formation [25]. This foundational role is conserved in human cells. Research on human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) has shown that:

- MIXL1 Expression Correlates with DE Efficiency: hiPSC lines with higher MIXL1 activation at the early differentiation stage demonstrate a greater propensity for generating high-quality DE and subsequent endoderm derivatives [25].

- A Functional Genomics Tool: Enforced expression of MIXL1 in hiPSC lines with low innate endoderm propensity can enhance their differentiation efficiency, effectively "re-wiring" the cells toward the desired lineage [25].

Quantitative Data on hiPSC Line Heterogeneity

An analysis of 11 hiPSC lines from four genetic sources revealed significant variability in DE differentiation efficacy, ranked using Principal Component 1 (PC1) scores from transcriptomic data as a proxy for differentiation progression [25]. The following table summarizes the performance of selected lines, highlighting the correlation between MIXL1 activity and successful organoid formation.

Table 1: Differentiation Propensity of Selected hiPSC Lines and Functional Outcomes

| hiPSC Line | DE Propensity Rank (PC1 Score) | MIXL1 Activity | Hepatocyte Differentiation (CYP3A4 Activity) | Human Intestinal Organoid (hIO) Generation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | High | High | Robust | High; spheroids progressed beyond passage 3, forming all major intestinal cell types. |

| C9 | High | High | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| C32 | Low | Low | Lower cytochrome P450 3A4 activity | Low; fewer spheroids generated, impaired growth after embedding, did not progress beyond passage 3. |

| C7 | Low | Low | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

The data clearly indicates that low-propensity lines like C32 not only struggle with DE formation but also fail to generate functionally robust advanced endoderm derivatives, underscoring the long-term impact of initial primitive streak-like induction quality [25].

Experimental Protocols for Primitive Streak and Definitive Endoderm Induction

Standardized DE Differentiation Workflow

A typical protocol for directing hiPSCs through a primitive streak-like state to definitive endoderm is adapted from the STEMDiff Definitive Endoderm protocol, which is widely used in the field [25].

Day 0: Seeding hiPSCs

- Grow hiPSCs to 70-80% confluence in pluripotency maintenance media.

- Dissociate cells using EDTA or a gentle cell dissociation reagent.

- Seed the cells at a density of 1.0–1.5 x 10^5 cells per cm² on Matrigel-coated plates in media containing a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) to enhance survival.

Day 1: Initiation of Differentiation

- Replace the seeding medium with definitive endoderm induction medium.

- Base Medium: RPMI 1640.

- Key Inductive Factors:

- Activin A (100 ng/mL): A TGF-β family ligand that mimics Nodal signaling, essential for primitive streak and DE induction.

- Wnt3a (25 ng/mL): Activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to reinforce the primitive streak program.

- Low Serum: Use 0-2% FBS for the first 24 hours to enhance sensitivity to morphogen signaling.

Days 2-4: DE Maturation

- Continue feeding cells with Activin A-containing medium but with increased FBS concentration (2% for Days 2-3).

- By day 4, cells should exhibit a characteristic epithelial morphology with tight, cobblestone-like packing.

- Quality Control: Analyze the population for co-expression of DE markers FOXA2 and SOX17 via flow cytometry or immunocytochemistry. A successful differentiation should yield >80% FOXA2+/SOX17+ cells in high-propensity lines.

Functional Validation via Advanced Differentiation

To confirm the functional quality of the DE cells, proceed with lineage-specific differentiation protocols:

- Hepatocyte Differentiation: Subject DE cells to a multi-stage protocol involving FGF, BMP, and HGF for hepatoblast specification, followed by OSM and dexamethasone for maturation. Assess functionality by measuring Albumin (ALB) secretion and Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) activity [25].

- Human Intestinal Organoid (hIO) Generation: Embed DE-derived spheroids in Matrigel and culture with growth factors (e.g., EGF, Wnt3a, R-spondin) to promote intestinal morphogenesis. Success is indicated by the emergence of budding structures containing intestinal stem cells (SOX9+), enterocytes (CDX2+), and other specialized lineages [25].

Visualizing the Primitive Streak-Driven Differentiation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway and transcriptional hierarchy from pluripotency to definitive endoderm specification, centered on the primitive streak-like stage.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathway from hiPSC to definitive endoderm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Primitive Streak and Definitive Endoderm Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSC Lines | Source of pluripotent cells for differentiation; genetic background impacts lineage propensity [25]. | Comparing differentiation efficiency across isogenic lines (e.g., C11 vs C32). |

| Activin A | Recombinant protein mimicking Nodal; key morphogen for inducing primitive streak and DE [25]. | Used at 100 ng/mL in base media for days 1-4 of DE differentiation. |

| Wnt3a | Recombinant protein activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway; synergizes with Activin A for induction [25]. | Used at 25 ng/mL during the first 24 hours of DE differentiation. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane matrix providing a substrate for cell attachment and 3D organoid culture. | Coating plates for 2D DE differentiation; embedding DE spheroids for 3D hIO culture. |

| FOXA2 & SOX17 Antibodies | Immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry markers for quantifying definitive endoderm purity [25]. | Quality control check on day 4 of differentiation; expect >80% double-positive cells. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Small molecule that improves survival of dissociated hiPSCs during passaging and seeding. | Added to cell suspension medium for 24 hours after seeding for differentiation. |

| StemCell Technologies STEMDiff DE Kit | Commercial, standardized kit for definitive endoderm differentiation. | Alternative to lab-made media for consistent, robust DE generation. |

The efficient navigation of the primitive streak stage is not merely a technical hurdle but a determinant of success in downstream organoid applications. The propensity of a given hiPSC line to activate MIXL1 and robustly traverse this developmental checkpoint directly impacts the physiological relevance and functionality of the resulting endoderm-derived tissues, such as hepatocytes and intestinal organoids [25]. As the field moves toward greater standardization and scalability in organoid generation for precision medicine and drug toxicity screening [20], the pre-assessment of hiPSC lineage propensity and the modulation of key drivers like MIXL1 will become integral to manufacturing fit-for-purpose stem cell products. Mastering this critical first step ensures that organoid models truly reflect human physiology, thereby enhancing the predictive power of preclinical drug development.

Organoid technology has revolutionized biomedical research by providing in vitro three-dimensional miniature structures that mimic the cellular heterogeneity, architecture, and function of human organs. The pluripotency state of the starting stem cell population represents a fundamental variable that dictates the developmental potential, application scope, and limitations of the resulting organoid model. Researchers must choose between human pluripotent stem cells and adult stem cells, each offering distinct advantages and constraints that align with specific research objectives. PSCs, including both embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells, possess unlimited self-renewal capacity and the potential to differentiate into any cell type derived from the three germ layers. In contrast, AdSCs, harvested from specific adult tissues, exhibit more restricted differentiation potential typically limited to their tissue of origin. This review provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these two approaches, examining their differential impacts on organoid development, maturation, and application within the context of a broader thesis on how stem cell pluripotency states direct organoid differentiation research.

Fundamental Biological and Technical Distinctions

The choice between PSCs and AdSCs establishes divergent experimental pathways in organoid generation, influencing protocol complexity, developmental recapitulation, and final organoid composition. PSC-derived organoids undergo stepwise differentiation mimicking embryonic organogenesis, requiring sequential signaling modulation to guide cells through developmental milestones over extended periods. This approach generates organoids containing multiple cell types, including epithelial, mesenchymal, and sometimes endothelial components, effectively recreating aspects of the tissue microenvironment [26]. The complex multicellularity makes PSC-derived organoids particularly valuable for studying human development and disorders affecting tissue interactions.

Conversely, AdSC-derived organoids originate from tissue-resident stem cells already committed to specific lineages, utilizing their innate self-organization capacity within permissive culture conditions. These protocols typically employ defined growth factor combinations that maintain stemness and promote differentiation along predetermined pathways, resulting in organoids predominantly comprising epithelial cell types without mesenchymal components [26]. The relative technical simplicity and faster generation time make AdSC-derived organoids ideal for high-throughput applications, though their cellular complexity remains more limited compared to PSC-derived models.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of PSC-Derived vs. AdSC-Derived Organoids

| Characteristic | PSC-Derived Organoids | AdSC-Derived Organoids |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) | Tissue-specific adult stem cells (e.g., Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells) |

| Differentiation Potential | Pluripotent (all three germ layers) | Multipotent (limited to tissue of origin) |

| Protocol Duration | Extended (weeks to months) | Shorter (days to weeks) |

| Cellular Complexity | High (multiple cell types, including epithelial and mesenchymal) | Lower (predominantly epithelial cells) |

| Developmental Stage Modeled | Fetal-like development | Adult tissue homeostasis |

| Genetic Manipulation | Highly amenable (CRISPR/Cas9 in iPSCs) | More challenging |

| Primary Applications | Developmental biology, disease modeling, drug toxicity screening | Disease modeling (especially monogenic diseases and cancer), personalized medicine, host-pathogen interactions |

Protocol Architectures and Workflow Specifications

PSC-Derived Organoid Generation

The generation of organoids from PSCs requires meticulously orchestrated protocols that recapitulate embryonic development through sequential signaling manipulation. A representative protocol for generating jawbone-like organoids from human iPSCs demonstrates this multi-step approach [27]. The process begins with 3D aggregation of dissociated iPSCs in V-bottom ultra-low-cell-adhesion plates with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 to enhance cell survival. Neural crest cell induction follows using combined TGF-β inhibitor (SB431542) and GSK3β inhibitor (CHIR99021) treatment, with BMP4 pretreatment to suppress neuroectoderm differentiation. Successful induction of HOX-negative NCCs is validated through flow cytometry for CD271high cells and immunostaining for SOX10, TFAP2A. Subsequent mandibular prominence ectomesenchyme specification employs Fgf8 and endothelin-1 to establish Dlx5+ and Hand2+ expression patterns mirroring in vivo proximal-distal patterning. Finally, osteogenic conditions induce mineralized bone matrix formation containing network-forming osteocytes, creating jawbone-like organoids suitable for disease modeling and regeneration studies.

The development of cerebral organoids from PSCs illustrates an alternative approach utilizing self-organization with minimal extrinsic patterning [28] [26]. The widely-used SFEBq (serum-free floating culture of embryoid body-like aggregates with quick aggregation) method involves embedding embryoid bodies in Matrigel and culturing them in neural induction media without additional patterning factors, allowing spontaneous development of various brain regions. For more specific regional identities, patterning protocols incorporate morphogens like BMP, WNT, and SHH pathway modulators to generate region-specific organoids (cortical, thalamic, midbrain, striatal, cerebellar). Further refinement through assembloid techniques enables modeling of neural circuit formation by fusing region-specific organoids, such as dorsal and ventral forebrain spheroids to study GABAergic neuron migration [28].

AdSC-Derived Organoid Generation

AdSC-derived organoid protocols employ more direct approaches leveraging the innate differentiation program of tissue-resident stem cells. The foundational intestinal organoid protocol isolates crypt structures or Lgr5+ stem cells from intestinal tissue and embeds them in Matrigel with a defined medium containing EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin to support stem cell maintenance and differentiation [26]. This minimal niche reconstitution allows spontaneous formation of crypt-villus structures containing all intestinal epithelial lineages without mesenchymal cells. Similar approaches have been successfully adapted for various epithelial organs including stomach, liver, pancreas, and lung by modifying growth factor combinations to match tissue-specific requirements [29] [26].

Diagram 1: Comparative workflow architectures for PSC-derived versus AdSC-derived organoid generation

Functional Outputs and Maturation Characteristics

Electrophysiological and Functional Maturation

Functional characterization reveals significant differences in maturation trajectories between PSC-derived and AdSC-derived organoids. Brain organoids derived from PSCs develop complex electrical activity over extended culture periods, with studies demonstrating the emergence of synchronized network activity, oscillatory dynamics, and functional synaptic connections [28]. Multimodal electrophysiological assessments using patch-clamp recordings, multi-electrode arrays, and calcium imaging have confirmed the presence of action potentials, synaptic transmission, and network bursting in cerebral organoids, albeit with developmental timelines extending over months. This protracted maturation mirrors human brain development but presents challenges for disease modeling and drug screening applications requiring adult-like phenotypes.

Accelerating neuronal maturation in PSC-derived systems represents an active research frontier. Recent breakthrough approaches include the GENtoniK cocktail combining LSD1 inhibitor GSK2879552, DOT1L inhibitor EPZ-5676, NMDA, and LTCC agonist Bay K 8644, which significantly enhances synaptic density, electrophysiological function, and transcriptional maturation in cortical neurons and organoids [30]. This small-molecule combination targets chromatin remodeling and calcium-dependent transcription pathways to effectively advance functional maturity across multiple neural and non-neural lineages.

Extracellular Matrix Composition and Structural Organization

The extracellular matrix microenvironment differs substantially between organoid types based on their cellular composition. PSC-derived organoids frequently contain self-produced mesenchymal components that generate native ECM proteins, creating more authentic tissue-scale mechanical properties and signaling environments. For example, jawbone-like organoids derived from iPSCs through mandibular prominence ectomesenchyme spontaneously produce mineralized bone matrices containing type-I collagen and embedded osteocytes [27]. This autonomous matrix production enables the formation of complex 3D tissue architectures that more closely resemble native organ organization.

In contrast, AdSC-derived organoids predominantly rely on exogenous ECM supplements like Matrigel to provide structural support and biochemical cues, as they typically lack mesenchymal stromal cells capable of depositing native matrix components. While this simplifies the culture system, it introduces xenogeneic components that may influence organoid phenotype and limit translational applications. Recent advances in synthetic ECM-mimetic hydrogels offer promising alternatives to address batch variability and composition standardization challenges in both PSC and AdSC organoid culture systems [31].

Table 2: Functional and Maturation Properties of Different Organoid Models

| Property | PSC-Derived Organoids | AdSC-Derived Organoids |

|---|---|---|

| Maturation Timeline | Protracted (months to years) | Relatively faster (weeks to months) |

| Functional Assessment | Emerging electrical activity, network synchronization, metabolic functions | Tissue-specific functions (e.g., absorption, secretion) |

| ECM Composition | Self-produced native ECM + exogenous support | Primarily exogenous ECM (e.g., Matrigel) |

| Vascularization | Generally absent without engineering | Generally absent without engineering |

| Metabolic Function | Developing, often fetal-like | More mature, adult-like functions |

| Electrical Activity | Demonstrated in neural, cardiac organoids | Tissue-dependent |

| Transplantability | Demonstrated in animal models | Demonstrated in animal models |

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Disease Modeling Capabilities

The selection between PSC and AdSC sources directly influences disease modeling approaches and capabilities. PSC-derived organoids excel in modeling neurodevelopmental disorders and genetic syndromes affecting organogenesis, as they recapitulate early developmental processes inaccessible in post-natal tissues. Cerebral organoids have successfully modeled microcephaly, autism spectrum disorders, and Zika virus-induced neuropathology, revealing disease mechanisms operating during early brain development [28] [32]. Similarly, patient-specific iPSC-derived organoids offer unprecedented opportunities for studying genetic diseases like osteogenesis imperfecta, with jawbone organoids recapitulating abnormal mineralization and matrix deposition phenotypes [27].

AdSC-derived organoids provide superior models for carcinogenesis and monogenic disorders affecting adult tissues, as they maintain the genetic and epigenetic signatures of the original tissue while permitting genetic manipulation and high-throughput screening. Patient-derived tumor organoids retain histological features, genetic alterations, and drug response patterns of original tumors, enabling personalized therapy selection and resistance mechanism studies [20] [26]. The genetic stability and scalability of AdSC-derived organoids make them particularly suitable for biobanking and large-scale genetic screens.

Pharmaceutical Applications

Both organoid types are transforming preclinical drug development, though their applications differ based on their physiological relevance and scalability. PSC-derived organoids provide human-specific platforms for developmental toxicity testing and disease-specific therapeutic screening, addressing species-specific discrepancies in drug responses [20]. Liver organoids enable prediction of drug-induced hepatotoxicity, while cardiac organoids detect cardiotoxic effects missed in animal models. The ability to generate patient-specific organoids from iPSCs further supports personalized therapeutic screening across diverse genetic backgrounds.

AdSC-derived organoids offer robust platforms for high-throughput compound screening and personalized oncology applications. Patient-derived tumor organoids successfully predict individual responses to chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies, with clinical studies demonstrating their potential to guide cancer treatment decisions [20] [26]. The reproducibility and scalability of AdSC-derived organoids facilitate their integration into industrial drug discovery pipelines, potentially reducing late-stage drug attrition rates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Organoid Generation and Manipulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Guide differentiation, enhance cell survival | PSC differentiation, neural crest induction [27] |

| Growth Factors | Fgf8, Edn1, EGF, Noggin, R-spondin | Patterning, stem cell maintenance | Regional specification (PSC), stem cell niche (AdSC) [27] [26] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels, collagen | 3D structural support, biochemical cues | All organoid culture systems |

| Maturation Accelerators | GSK2879552 (LSD1 inhibitor), EPZ-5676 (DOT1L inhibitor), Bay K 8644 (LTCC agonist) | Promote functional maturation | PSC-derived neuronal maturation [30] |

| Cell Surface Markers | CD271 (NGFR), Lgr5, EpCAM | Identification, isolation of specific cell populations | Neural crest cells (PSC), intestinal stem cells (AdSC) |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Genetic manipulation, disease modeling | Mainly PSC-derived organoids |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite remarkable progress, both PSC and AdSC-derived organoid technologies face significant challenges requiring continued innovation. Incomplete maturation remains a fundamental limitation, with most organoids retaining fetal-like characteristics rather than achieving full adult functionality [31] [32]. The delayed maturation is particularly pronounced in PSC-derived organoids, though recent advances in small-molecule acceleration strategies show promise for addressing this limitation [30]. Vascularization represents another critical challenge, as current organoid models largely lack perfusable vascular networks, limiting nutrient diffusion, organoid size, and physiological relevance. Emerging approaches incorporating endothelial cells and fluidic systems using organ-on-chip technologies may address this limitation.

Standardization and reproducibility issues persist due to protocol variability between laboratories and batch-to-batch differences in critical reagents like Matrigel [20]. Future developments focusing on defined culture conditions and engineered matrices will enhance experimental reproducibility and translational potential. Similarly, increasing organoid complexity through assembloid and connettoid approaches that combine multiple organoid regions will enable modeling of circuit-level functions and inter-organ communication [28]. As the field progresses, the complementary strengths of PSC and AdSC-derived organoids will likely be leveraged in integrated approaches that maximize their respective advantages for specific research and clinical applications.

Diagram 2: Key challenges and emerging solutions in organoid technology

The selection between pluripotent and adult stem cell sources for organoid generation represents a fundamental strategic decision with far-reaching implications for experimental outcomes and applications. PSC-derived organoids provide unparalleled models for human development and disorders affecting organogenesis, offering complex multicellular systems that mimic embryonic and fetal tissue organization. Conversely, AdSC-derived organoids excel in modeling adult tissue homeostasis, carcinogenesis, and monogenic disorders, with advantages in scalability, genetic stability, and maturation state. Rather than competing approaches, these methodologies offer complementary strengths that researchers can strategically deploy based on specific biological questions. Future advances in maturation acceleration, vascularization, and standardization will further enhance the utility of both organoid types, solidifying their position as indispensable tools for biomedical research, drug development, and regenerative medicine. The ongoing refinement of both platforms will continue to deepen our understanding of human biology and pathology while accelerating the development of novel therapeutics.

From Pluripotent to Complex: Protocols and Cutting-Edge Applications in Organoid Differentiation

The generation of organoids from human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), represents a transformative approach in biomedical research. These self-organizing three-dimensional structures mimic the complexity of native organs, providing unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [20]. The entire process hinges on precisely controlling the pluripotent state of stem cells, guiding them through developmental pathways that recapitulate organogenesis in vitro. The pluripotency state of the starting cell population—whether "naïve" or "primed"—profoundly influences differentiation efficiency and organoid fidelity, as these states exhibit distinct epigenetic landscapes, metabolic profiles, and signaling requirements [33]. Naïve state pluripotency, characterized by global DNA hypomethylation and open chromatin structures, offers enhanced developmental plasticity, while primed state cells demonstrate restricted potential as they approach lineage commitment [33]. Understanding and controlling these pluripotency networks is therefore fundamental to standardizing robust organoid differentiation protocols.

Core Principles of Organoid Differentiation

The Role of Signaling Pathways

Directed differentiation of PSCs into organoids requires the meticulous temporal modulation of key developmental signaling pathways. These pathways, including Wnt, FGF, TGF-β, BMP, and RA (retinoic acid), are manipulated through specific small molecule inhibitors and growth factors to steer cell fate [34] [33]. The goal is to mimic the natural signaling centers that pattern the embryo, sequentially narrowing developmental potential from broad germ layers to specific organ identities.

Three-Dimensional Culture Systems

The transition from two-dimensional (2D) monolayers to three-dimensional (3D) culture is critical for organoid formation. This shift enables the emergence of complex cytoarchitecture, cell-cell interactions, and tissue-level polarity that define functional organs [35] [20]. Suspension culture systems, often using low-adhesion plates, and extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds, like Matrigel, provide the structural context necessary for self-organization and morphogenesis [36] [37].

Detailed Differentiation Protocols

Brain Organoid Protocol

Unguided brain organoids model the early stages of human neurodevelopment, including regional patterning and neuroepithelium formation.

Key Steps:

- Embryoid Body Formation (Day 0): Aggregate approximately 500,000 human PSCs per aggregate in low-adhesion 96-well plates using medium containing a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to enhance cell survival [36].

- Neural Induction (Day 2-10): Transfer aggregates to neural induction medium (NIM). For unguided protocols, this medium lacks patterning morphogens to allow spontaneous regionalization. Early exposure to an extrinsic matrix (e.g., Matrigel) is critical for supporting neuroepithelial formation and lumen expansion [36].

- Maturation (Day 11+): Transition organoids to differentiation medium to support neuronal differentiation and circuit formation. The addition of Vitamin A from day 15 onward supports further maturation [36].

Morphodynamic Phases: Live imaging reveals three distinct phases: (1) rapid tissue and lumen growth, (2) tissue stabilization with lumen fusion, and (3) stabilization of lumen number with continued growth [36].

Figure 1: Workflow for the differentiation of brain organoids from human PSCs.

Liver Organoid Protocol

Liver organoids model the metabolic and secretory functions of the human liver, providing a tool for studying liver disease and drug metabolism [35].

Key Steps:

- Definitive Endoderm Induction: Treat PSC aggregates with Activin A to direct differentiation towards definitive endoderm, the germ layer that gives rise to the liver.

- Hepatic Specification: Activate Wnt and FGF signaling pathways to pattern the endoderm into hepatic progenitor cells (hepatoblasts) [35] [38].

- Hepatocyte Maturation and 3D Culture: Transfer progenitors to 3D culture conditions in a supportive matrix (e.g., Matrigel). Promote functional maturation using a combination of factors, which may include HGF, OSM, and glucocorticoids [35]. The resulting organoids exhibit key liver functions, including albumin secretion and drug metabolism.

Vascularization Advancements: Recent breakthroughs have enabled the generation of vascularized liver organoids. This involves co-differentiating PSCs into hepatic and endothelial lineages, often using custom triple reporter stem cell lines to track different cell types, resulting in organoids with perfusable vessel-like networks [39].

Heart Organoid Protocol