HCR-FISH vs. CARD-FISH: A Comprehensive Sensitivity and Application Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a critical evaluation of two powerful signal amplification techniques in fluorescence in situ hybridization: Hybridization Chain Reaction FISH (HCR-FISH) and Catalyzed Reporter Deposition FISH (CARD-FISH).

HCR-FISH vs. CARD-FISH: A Comprehensive Sensitivity and Application Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of two powerful signal amplification techniques in fluorescence in situ hybridization: Hybridization Chain Reaction FISH (HCR-FISH) and Catalyzed Reporter Deposition FISH (CARD-FISH). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies for both technologies. By synthesizing current research, we deliver a practical comparative analysis of their sensitivity, specificity, and suitability for diverse sample types—from clinical biopsies to environmental samples. The content addresses key decision factors for protocol selection, troubleshooting common challenges, and validating results, ultimately serving as a strategic guide for implementing these techniques in biomedical research and diagnostic development.

Understanding HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH: Core Principles and Signal Amplification Mechanisms

The fundamental principle of Hybridization Chain Reaction combined with Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (HCR-FISH) is an enzyme-free, isothermal signal amplification method driven by target-triggered polymerization of metastable DNA hairpins. In the presence of a specific nucleic acid target (e.g., mRNA), an initiator probe bound to the target triggers a cascading, autonomous self-assembly of two fluorescently labeled DNA hairpin molecules (H1 and H2). This reaction results in the formation of a long, nicked double-stranded DNA polymer that tethers numerous fluorophores to the site of the target, enabling its sensitive visualization without the need for enzymatic amplification [1] [2] [3]. This core mechanism stands in contrast to enzyme-dependent methods like CARD-FISH, offering distinct advantages in simplicity, sample penetration, and robustness.

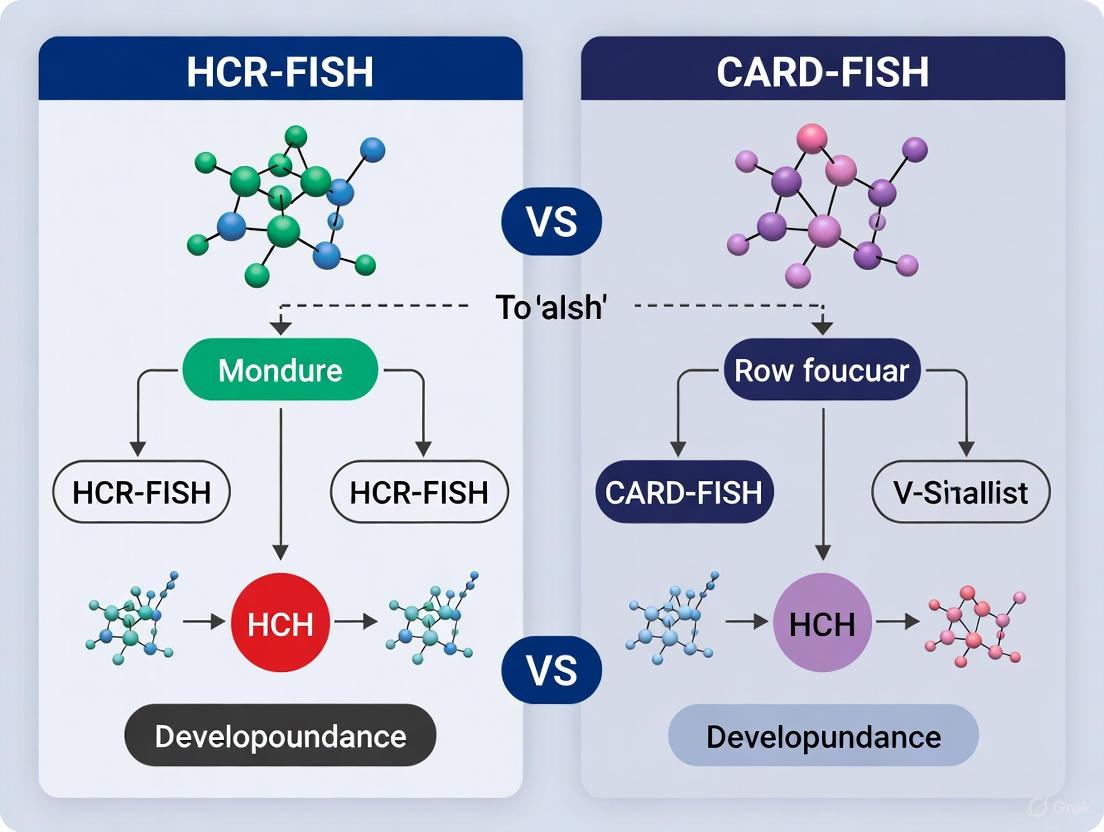

Head-to-Head: HCR-FISH vs. CARD-FISH

The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH based on key performance metrics and characteristics relevant to research and diagnostic applications.

| Feature | HCR-FISH | CARD-FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Enzyme-free, hybridization chain reaction [3] | Enzyme-dependent (horseradish peroxidase, HRP) catalyzed reporter deposition [4] [5] |

| Signal Amplification | Linear polymerization of DNA hairpins [1] | Exponential deposition of fluorescent tyramides [5] |

| Typical Protocol Duration | Shorter; less time-consuming [3] | Longer; includes permeabilization and enzymatic steps [3] [5] |

| Sample Penetration | Excellent (small hairpin probes) [2] [6] | Limited (large HRP-probe conjugate requires intense permeabilization) [3] [5] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Straightforward; simultaneous one-stage amplification for multiple targets [2] | Complex; sequential hybridization rounds often required |

| Quantitative Imaging | Enables both analog relative and digital absolute quantitation [2] | Primarily used for detection and enumeration [4] |

| Key Limitations | Potential for false-positive signals from probe adsorption in complex samples [3] | Use of ( H2O2 ) may degrade nucleic acids; permeabilization is critical and challenging [3] |

Experimental Protocol & Workflow Comparison

To understand the practical differences in sensitivity and application, it is essential to examine the detailed protocols for each method. The following workflows are compiled from optimized procedures used in environmental and cell imaging studies [3].

HCR-FISH Workflow

Key Steps Explained:

- Probe Hybridization: Fixed samples are incubated with initiator DNA probes designed to be complementary to the target RNA. In advanced "split-initiator" HCR v3.0, two probes, each carrying half of the initiator sequence, must bind adjacently on the target to colocalize the full initiator, providing automatic background suppression [2].

- Amplification: Without any enzymatic step, fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins (H1 and H2) are added. The initiator sequence on the target binds to and opens the first hairpin (H1), exposing a sequence that opens the second hairpin (H2). This, in turn, exposes a sequence identical to the initiator, leading to a chain reaction that grows a fluorescent polymer at the target site [1] [3].

CARD-FISH Workflow

Key Steps Explained:

- Permeabilization: A critical and sample-dependent step. Microbial cells, especially in environmental samples, require enzymatic treatment (e.g., lysozyme, proteinase K) to allow the large HRP-labeled probe to penetrate the cell wall [7] [5].

- Peroxidase Inactivation: Samples are treated with ( H2O2 ) to inactivate endogenous peroxidases that would otherwise cause high background signal. This step risks damaging the target nucleic acids [3].

- Hybridization and Amplification: Samples are hybridized with oligonucleotide probes conjugated to HRP. Subsequently, fluorescently labeled tyramide substrates are added. The HRP enzyme catalyzes the deposition of multiple tyramide molecules, forming an insoluble fluorescent precipitate at the site of the target [4] [5].

Performance Data: Sensitivity & Specificity

Quantitative data from controlled studies highlight the performance differences between these two techniques, particularly in challenging samples.

Table 1: Quantitative Detection Efficiency in Environmental Samples

| Sample Type | Method | Target | Detection Efficiency (vs. DAPI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-oligotrophic Alpine Spring Water | CARD-FISH | Bacteria (EUB338 mix) | ~83% | [7] |

| Ultra-oligotrophic Alpine Spring Water | Standard FISH | Bacteria (EUB338 mix) | ~15% | [7] |

| Marine Sediments | Optimized HCR-FISH | Universal Bacteria | Signally intensity sufficient for detection* | [3] |

*The study demonstrated that with protocol optimization (increasing initiator probe concentration to 10 μmol/L), HCR-FISH successfully visualized microbes in marine sediments where traditional FISH fails, though a specific percentage vs DAPI was not provided [3].

Specificity and Background:

- Background Suppression: A key advancement in HCR-FISH (v3.0) is automatic background suppression. Using split-initiator probes reduces non-specific amplified background by approximately 50-60 fold compared to full-initiator probes, as demonstrated in whole-mount chicken embryos [2].

- False Positives: A challenge for HCR-FISH in complex samples like sediments is the adsorption of DNA probes to abiotic particles, generating false-positive signals. This can be mitigated through optimized sample pretreatment and hybridization buffers [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The table below details the essential components and their functions.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| HCR-FISH | ||

| Initiator Probes | Binds target RNA and triggers the HCR cascade | In v3.0, split-initiator probes are used for automatic background suppression [2]. |

| DNA Hairpins (H1, H2) | Fluorescently-labeled amplifiers that form the polymer | Must be kinetically trapped and metastable; store energy for the chain reaction [1]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Creates optimal conditions for probe binding | Formamide concentration and salt can be adjusted for stringency [3]. |

| CARD-FISH | ||

| HRP-labeled Probes | Confers specificity and enzymatic activity | The large size of the HRP conjugate necessitates permeabilization [5]. |

| Permeabilization Enzymes | Breaks down cell walls to allow probe entry | Lysozyme for many Bacteria; Proteinase K for more resistant cells [7]. |

| Fluorescent Tyramide | Substrate for HRP; deposits and amplifies signal | The deposition creates an insoluble precipitate at the target site [5]. |

| General | ||

| Paraformaldehyde | Fixes samples and preserves cellular structure | Standard fixative for microbial cells [3]. |

| DAPI | Counterstain for total cell counts | Used to determine total prokaryotic abundance and hybridization efficiency [7]. |

Advanced Applications & Evolution

The fundamental principle of HCR has been adapted to create powerful next-generation assays that extend beyond RNA detection.

- proxHCR for Protein Detection: The HCR principle has been engineered for proximity-dependent detection of proteins and post-translational modifications. In this system, antibodies conjugated to special DNA hairpins bring initiator sequences into proximity only when their target proteins are nearby or interacting. This triggers the standard HCR amplification, allowing for enzyme-free, sensitive protein imaging and flow cytometry [8].

- Nonlinear HCR: Traditional HCR produces linear polymers. By designing different primer and initiation methods, nonlinear HCR systems (e.g., branched HCR, dendritic HCR) have been developed. These form highly branched DNA nanostructures, achieving exponential growth kinetics and even higher sensitivity for low-abundance biomarker detection in biosensing and bioimaging [1].

Catalyzed Reporter Deposition-Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (CARD-FISH) represents a significant advancement in environmental microbiology for detecting, identifying, and enumerating microorganisms without cultivation. This technique leverages the catalytic power of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to deposit numerous fluorescent tyramide molecules at target sites, achieving up to 100-fold signal amplification compared to conventional FISH. While CARD-FISH provides exceptional sensitivity for detecting microorganisms with low ribosomal RNA content, it presents challenges including required cell permeabilization and endogenous peroxidase inactivation. This review examines the CARD-FISH mechanism in detail and compares its performance with emerging alternatives like Hybridization Chain Reaction-FISH (HCR-FISH), providing researchers with comprehensive experimental data and protocols for implementation.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes has become a standard technique in environmental microbiology since its development over 25 years ago [9]. The method allows phylogenetic identification and enumeration of microorganisms in diverse habitats including soil, sediments, aquatic environments, and engineered sludge [9]. However, conventional FISH faces limitations in detecting microorganisms with low ribosomal content, small cell size, or low metabolic activity, primarily due to insufficient sensitivity from limited target molecules, poor probe permeability, and low hybridization efficiency [9] [10].

To address these limitations, several signal amplification methods have been developed. CARD-FISH (also known as Tyramide Signal Amplification or TSA) and HCR-FISH represent two prominent approaches that enhance detection sensitivity for environmental microorganisms [9] [11]. CARD-FISH, first applied to environmental microorganisms in 1997, utilizes enzymatic amplification via horseradish peroxidase [9], while HCR-FISH, developed more recently, employs a hybridization chain reaction without enzymes [11]. Understanding the mechanism, advantages, and limitations of CARD-FISH is essential for researchers selecting appropriate detection methods for specific applications.

The CARD-FISH Mechanism: HRP and Tyramide Chemistry

Fundamental Principles

The CARD-FISH technique builds upon conventional FISH by incorporating a signal amplification step that significantly enhances detection sensitivity. The method is based on the catalytic activity of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to oligonucleotide probes. When HRP encounters hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), it activates fluorescently labeled tyramide derivatives, converting them into highly reactive radical intermediates [9] [12] [13]. These activated tyramide radicals covalently bind to electron-rich tyrosine residues on proteins in the immediate vicinity of the HRP enzyme [13]. This deposition results in the accumulation of numerous fluorescent molecules at the target site, dramatically enhancing the fluorescence signal compared to conventional FISH where only one fluorophore is typically deposited per probe [9].

Table 1: Key Components of the CARD-FISH System

| Component | Function | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| HRP-labeled Probe | Binds to target rRNA sequence | Large molecule (~40 kDa) requiring permeabilization |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Enzyme substrate | Activates HRP; requires concentration optimization |

| Labeled Tyramide | Signal molecule | Fluorophore or hapten conjugate; activated by HRP |

| Blocking Reagent | Reduces background | Minimizes non-specific tyramide deposition |

Procedural Workflow

The CARD-FISH protocol involves several critical steps that must be optimized for different sample types. First, samples are fixed, typically with paraformaldehyde or ethanol, to preserve cellular structure and nucleic acids [9]. For many prokaryotic cells, permeabilization treatments using enzymes such as lysozyme, achromopeptidase, or proteinase K are necessary to facilitate entry of the large HRP-labeled probes [9]. Cells are often immobilized on slides or filters using low-melting-point agarose embedding to prevent loss during subsequent treatments [9].

Hybridization with HRP-labeled oligonucleotide probes follows standard FISH procedures but uses lower probe concentrations (typically 0.1 μM or 0.5 ng/μL) to minimize background fluorescence [9]. After hybridization and washing, the CARD reaction is performed using a working solution containing fluorescently labeled tyramide, H₂O₂, and often amplification enhancers. The reaction is typically stopped after 10-30 minutes, followed by counterstaining and microscopy [9] [4].

Figure 1: CARD-FISH Experimental Workflow. The diagram outlines key steps in the CARD-FISH procedure, highlighting critical stages that require optimization for different sample types.

Technical Advancements and Methodological Optimizations

Enhancing Sensitivity and Reducing Background

Significant methodological improvements have been made to optimize CARD-FISH performance. The addition of 10-30% dextran sulfate to the CARD working solution enhances signal localization and intensity through volume exclusion effects, though it may introduce spotty background signals that can be mitigated by elevated temperature washing (45-60°C) [9]. Inorganic salts (e.g., 2M NaCl) and organic enhancers like p-iodophenyl boronic acid (at 20 times the tyramide concentration) have been shown to significantly improve signals, though the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood [9].

Tyramide concentration represents a critical optimization parameter. While higher concentrations increase detection rates for environmental bacteria, excessive tyramide causes elevated background fluorescence [9]. Similarly, HRP-labeled probe concentration must be carefully titrated, with typical CARD-FISH protocols using substantially lower concentrations (0.1 μM or 0.5 ng/μL) than conventional FISH to minimize nonspecific signals [9].

For challenging targets requiring extreme sensitivity, two-pass TSA-FISH has been developed, involving two sequential TSA reactions [9]. This method initially uses dinitrophenyl (DNP)-labeled tyramide instead of fluorophore-labeled tyramide, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-DNP antibody and a second TSA reaction with fluorophore-labeled tyramide [9]. This approach provides additional signal amplification but requires careful optimization with dextran sulfate and blocking reagents to maximize signal intensity while minimizing nonspecific staining [9].

Permeabilization Strategies

As HRP is a large molecule (approximately 40 kDa), permeabilization protocols must be carefully optimized for different microbial groups [9]. The fixation method significantly impacts permeability, with protein-denaturing reagents (e.g., ethanol) typically providing better permeability than cross-linking reagents (e.g., paraformaldehyde), though some prokaryotes exhibit signal loss with ethanol fixation [9]. Storage conditions also affect permeability, with long-term storage inexplicably increasing detection rates for some microorganisms [9].

Table 2: CARD-FISH Permeabilization Treatments for Different Microorganisms

| Microorganism Type | Recommended Treatment | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative Bacteria | Lysozyme (10-100 mg/mL, 37°C, 30-90 min) | Most commonly used enzyme; concentration and time require optimization |

| Gram-positive Bacteria | Lysozyme + Achromopeptidase | Combined enzymes often necessary for adequate permeabilization |

| Planctomycetes | Often minimal treatment required | Some reports indicate detection without specific permeabilization |

| Methanogens | Variable; some require no treatment | Species with S-layers may be detected without permeabilization |

CARD-FISH vs. HCR-FISH: Comparative Performance Analysis

Sensitivity and Detection Efficiency

Comparative studies between CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH reveal important performance differences relevant for research applications. CARD-FISH typically provides 26- to 41-fold higher fluorescence signals than standard FISH [10], with some reports indicating up to 100-fold enhancement [12] [13]. In contrast, HCR-FISH generally offers more modest amplification, typically around 8-fold higher sensitivity than standard FISH [10], though optimized protocols (quickHCR-FISH) can improve this further.

When applied to marine bacterioplankton, CARD-FISH has demonstrated superior capability for detecting microorganisms in oligotrophic environments where cellular rRNA content is low [10] [4]. However, for certain applications, particularly with Gram-positive bacteria, HCR-FISH shows advantages due to better probe penetration without extensive permeabilization treatments [10].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | CARD-FISH | HCR-FISH | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplification | 26-100x conventional FISH [10] [12] | ~8x conventional FISH [10] | Pure cultures & environmental samples |

| Detection Rate in Marine Samples | High for oligotrophic microbes [4] | Variable; requires optimization [11] | Marine seawater & sediments |

| Probe Penetration | Requires permeabilization for most prokaryotes [9] | Better penetration without treatment [11] | Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria |

| Background Signals | Manageable with optimization [9] | Can be problematic in sediments [11] | Environmental sample applications |

| Protocol Duration | Longer due to multiple steps [11] | Shorter; less time-consuming [11] | Complete experimental workflow |

Practical Considerations for Research Applications

Beyond sensitivity, several practical factors influence technique selection for specific research applications. CARD-FISH requires inactivation of endogenous peroxidases using H₂O₂ treatment, which may degrade nucleic acids [11] [10]. The method also necessitates careful optimization of tyramide incubation time for each sample type [10]. Conversely, HCR-FISH does not require peroxidase inactivation, better preserving target RNA [11].

CARD-FISH has proven particularly valuable for identifying key protistan groups in aquatic environments, revealing that Paraphysomonas or Spumella-like chrysophytes are less abundant than previously thought, while little-known groups like heterotrophic cryptophyte lineages (CRY1), cercozoans, katablepharids, and MAST lineages are more prominent [4]. When combined with tracer techniques and double CARD-FISH, the method has enabled visualization of food vacuole contents, demonstrating that larger flagellates are actually omnivores ingesting both prokaryotes and other protists [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Protocols

Critical Reagents for CARD-FISH Implementation

Successful implementation of CARD-FISH requires careful selection of reagents and optimization for specific applications. Commercial tyramide reagents are available with various fluorophore conjugates spanning the visible spectrum, with next-generation products like TyraMax dyes offering improved brightness and photostability [12]. These reagents are typically supplied with optimized amplification buffers that enhance sensitivity and specificity.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CARD-FISH

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| HRP-Labeled Probes | Direct HRP-conjugated oligonucleotides | Target sequence binding with enzymatic activity |

| Tyramide Reagents | Alexa Fluor tyramides, TyraMax dyes | Signal amplification upon HRP activation |

| Permeabilization Enzymes | Lysozyme, Achromopeptidase, Proteinase K | Facilitate probe entry through cell walls |

| Amplification Enhancers | Dextran sulfate, p-iodophenyl boronic acid | Increase signal intensity and localization |

| Blocking Reagents | TSA blocking reagent | Reduce non-specific background signals |

Detailed CARD-FISH Protocol for Environmental Samples

Based on established methodologies [9] [4], the following protocol provides a foundation for CARD-FISH implementation with environmental samples:

Sample Fixation: Fix samples with 1-3% formaldehyde or paraformaldehyde for 1-24 hours at 4°C. For some applications, ethanol fixation may improve permeability.

Cell Immobilization: Apply fixed samples to gelatin-coated slides or filters. Embed cells in low-melting-point agarose (0.1-0.3%) to prevent loss during subsequent treatments.

Permeabilization: Treat with lysozyme (10-100 mg/mL in 0.05M EDTA, 0.1M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) for 30-90 minutes at 37°C. Optimize concentration and duration for specific sample types.

Endogenous Peroxidase Inactivation: Incubate with 0.01-0.3% H₂O₂ in methanol for 30 minutes at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase activity.

Hybridization: Apply HRP-labeled probes (0.1-0.5 ng/μL) in hybridization buffer containing formamide, salts, and detergents. Hybridize for 2-12 hours at appropriate temperature based on probe design.

CARD Reaction: Incubate with tyramide working solution (containing fluorescent tyramide, H₂O₂, amplification buffer, and enhancers) for 10-30 minutes at 37°C.

Counterstaining and Microscopy: Wash thoroughly, counterstain with DAPI, and apply antifading mounting medium for epifluorescence or confocal microscopy.

CARD-FISH remains a powerful technique for detecting environmental microorganisms, particularly when high sensitivity is required. The HRP-tyramide amplification system provides exceptional signal enhancement that enables detection of microbes with low ribosomal content in oligotrophic environments. While the method requires careful optimization of permeabilization and amplification conditions, and faces challenges with background signals and protocol complexity, it continues to yield valuable insights into microbial ecology and diversity. Emerging alternatives like HCR-FISH offer advantages in certain applications, but CARD-FISH maintains its position as a gold standard for sensitive detection and identification of microorganisms in complex environmental samples.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has served as a canonical tool in environmental microbiology research, enabling the visualization and phylogenetic identification of targeted microbial cells at the single-cell level through 16S rRNA labeling [11] [3]. However, traditional FISH methods face significant limitations when applied to environmental samples containing microbes with low ribosomal RNA content, such as those found in marine sediments and oligotrophic habitats [11] [10]. These challenges primarily manifest as insufficient signal intensity for distinguishing target cells from background noise and problematic false-positive signals that compromise analytical specificity [11] [3].

To address these limitations, researchers have developed sophisticated signal amplification techniques that enhance detection sensitivity while maintaining specificity. Two prominent methods—Catalyzed Reporter Deposition-FISH (CARD-FISH) and Hybridization Chain Reaction-FISH (HCR-FISH)—have emerged as powerful alternatives to conventional FISH [11] [10]. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these amplification methodologies, examining their theoretical sensitivity limits, experimental performance metrics, and practical considerations for implementation in challenging research contexts. The evaluation is situated within a broader thesis on advancing microbial detection sensitivity, particularly for environmental samples where traditional methods prove inadequate.

Fundamental Principles of Amplification Mechanisms

CARD-FISH: Enzyme-Catalyzed Signal Amplification

CARD-FISH employs horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled oligonucleotide probes to achieve signal amplification through enzymatic activity [11]. When the HRP-conjugated probe hybridizes to its target rRNA, it catalyzes the deposition of fluorescently labeled tyramide substrates in the immediate vicinity of the hybridization site [11]. This enzymatic process generates substantial signal amplification, with reports indicating a 26- to 41-fold increase in fluorescence intensity compared to standard FISH [10]. The tyramide radicals produced by HRP exhibit extremely short diffusion distances, resulting in highly localized signal deposition that preserves spatial resolution [11].

Despite its impressive amplification capabilities, CARD-FISH presents several practical challenges. The large molecular weight of HRP (~40 kDa) impedes probe penetration into microbial cells, necessitating additional permeabilization steps that may vary in effectiveness across different microbial taxa [11] [3]. Furthermore, the method requires careful inactivation of endogenous peroxidases using H₂O₂, which risks degrading target nucleic acids and potentially compromising detection accuracy [11] [3]. The protocol also demands optimization of tyramide incubation times for different sample types, adding complexity to experimental workflows [10].

HCR-FISH: Enzyme-Free Signal Amplification Through Hybridization Chain Reaction

HCR-FISH utilizes an innovative enzyme-free amplification mechanism based on triggered self-assembly of nucleic acid hairpins [11] [14]. In this system, initiator probes hybridize to target rRNA sequences while exposing initiator regions that trigger a cascading hybridization event between two fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins [11] [14]. This process generates long, nicked double-stranded DNA polymers that accumulate fluorophores at the target site, significantly enhancing fluorescence signal without enzymatic involvement [11].

The fundamental HCR mechanism proceeds through four distinct stages: (1) initiator probes hybridize with targeted intracellular RNA, leaving their initiator sequence unpaired; (2) the unpaired initiator sequence binds to the unpaired tail of hairpin A, linearizing its stem-loop structure; (3) the newly exposed sequence on hairpin A binds to hairpin B, releasing a sequence identical to the initiator; and (4) this process repeats autonomously, forming elongated double-stranded DNA structures with numerous incorporated fluorophores [11]. This mechanism provides substantial signal amplification while avoiding enzymatic complications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH Amplification Mechanisms

| Characteristic | HCR-FISH | CARD-FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Mechanism | Enzyme-free hybridization chain reaction | Enzyme-catalyzed (HRP) tyramide deposition |

| Probe Size | Small oligonucleotides (~35-45 nt) [15] | Large HRP-labeled probes (~40 kDa) [11] |

| Cell Permeability | High due to small probe size [11] | Requires permeabilization steps [11] [10] |

| Endogenous Enzyme Interference | None | Requires H₂O₂ treatment to inactivate peroxidases [11] |

| Risk of Nucleic Acid Damage | Low | Moderate due to H₂O₂ treatment [11] |

| Protocol Flexibility | High; initiator probes easily modified [11] | Lower; HRP probes more complex to produce |

Diagram 1: HCR-FISH amplification mechanism based on triggered self-assembly of nucleic acid hairpins.

Theoretical Sensitivity Limits and Detection Thresholds

The theoretical sensitivity limits of signal amplification methods define their ultimate detection capabilities in ideal conditions. For CARD-FISH, the enzymatic amplification process provides significant signal enhancement, achieving detection thresholds suitable for microorganisms in oligotrophic environments like marine seawater and sediments where standard FISH fails [10]. The method's effectiveness stems from the high turnover rate of HRP enzymes, with each enzyme molecule catalyzing the deposition of numerous tyramide molecules [11].

HCR-FISH operates on fundamentally different principles with distinct theoretical advantages. The non-enzymatic nature of HCR eliminates several constraints inherent to CARD-FISH. Recent optimizations have demonstrated that HCR-FISH can achieve up to 8-fold higher sensitivity than standard FISH, positioning it as a viable alternative to CARD-FISH [10]. The quickHCR-FISH protocol, incorporating modified hybridization and amplification buffers with double-labeled amplifier probes, further enhances signal intensity while reducing incubation times [10].

The theoretical framework for HCR sensitivity suggests potential for single-molecule detection under optimal conditions. The split-initiator probe design in third-generation HCR (v3.HCR-FISH) significantly increases specificity by ensuring that amplification only triggers when two separate probes hybridize in close proximity to their target mRNA [14]. This approach dramatically reduces non-specific background signal while maintaining high amplification efficiency.

Table 2: Theoretical Sensitivity Limits and Detection Capabilities

| Parameter | HCR-FISH | CARD-FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplification Factor | Up to 8-fold over standard FISH [10] | 26- to 41-fold over standard FISH [10] |

| Theoretical Detection Limit | Potentially single molecules with optimized probes [14] | Limited by probe permeability and enzyme accessibility [11] |

| Impact of Cellular Activity | Less dependent on rRNA content [11] | Requires sufficient target accessibility [11] |

| Background Signal | Can be minimized with optimized protocols [11] | Generally low with proper peroxidase inactivation [11] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (up to 5 targets simultaneously) [14] | Limited by available enzyme substrates [15] |

Experimental Performance and Protocol Optimization

Methodology for HCR-FISH Protocol Optimization

Substantial optimization of HCR-FISH protocols has been necessary to achieve reliable performance with environmental samples. Initial attempts to apply HCR-FISH to sediment samples encountered significant challenges with false-positive signals, likely due to non-specific DNA adsorption to abiotic particles [11] [3]. Through systematic optimization, researchers have developed robust protocols that overcome these limitations.

Critical modifications to the original HCR-FISH protocol include increasing initiator probe concentration from 1 μmol/L to 10 μmol/L in hybridization buffer, significantly enhancing signal intensity without compromising specificity [11] [3]. Testing of five distinct HCR initiator/amplifier pairs on model organisms (Escherichia coli and Methanococcoides methylutens) identified two sets with superior hybridization efficiency and specificity [11] [3]. Incorporation of blocking reagents and dextran sulfate in hybridization and amplification buffers, adapted from CARD-FISH protocols, further improved signal-to-noise ratios in complex environmental matrices [10].

Sample pretreatment represents another crucial optimization area. Various cell detachment methods and extraction protocols have been evaluated specifically for sediment samples, with optimal combinations identified for minimizing false-positive signals while maintaining cell integrity [11]. Additionally, image processing techniques have been developed to enhance DAPI counterstaining signals, improving discrimination between microbial cells and abiotic particles in fluorescence microscopy [11].

Diagram 2: Key optimization strategies that enable effective HCR-FISH application to challenging environmental samples.

quickHCR-FISH: Accelerated Protocol for Enhanced Performance

The development of quickHCR-FISH represents a significant advancement in protocol efficiency [10]. This improved methodology incorporates modified hybridization and amplification buffers specifically formulated to produce high signal intensity with shorter amplification times [10]. The protocol has demonstrated particular effectiveness for detecting Gram-negative bacteria and has been successfully applied to environmental microorganisms in marine seawater and sediment samples [10].

A key innovation in quickHCR-FISH is the implementation of double-labeled amplifier probes, which further enhance signal intensity without increasing non-specific background [10]. This modification, combined with optimized buffer compositions, enables robust detection of microorganisms with low ribosomal content that would otherwise remain undetectable with standard FISH protocols [10].

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Direct comparison of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH performance reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each method. CARD-FISH generally provides higher absolute signal amplification, making it particularly effective for detecting microbes with extremely low metabolic activity in oligotrophic environments [10]. However, this advantage must be balanced against the method's technical complexities, including the requirement for precise permeabilization protocols and potential nucleic acid degradation from peroxidase inactivation treatments [11].

HCR-FISH offers slightly lower absolute amplification but superior specificity and flexibility. The method's modular design enables straightforward adaptation to different targets simply by modifying initiator probe sequences, while the same fluorescent amplifier components can be reused across different experiments [11]. This flexibility significantly reduces development time and cost compared to CARD-FISH, which requires production of new enzyme-conjugated probes for each target [11].

Experimental data from sediment samples demonstrates that optimized HCR-FISH protocols successfully visualize microbes that were previously challenging to detect, while simultaneously reducing false-positive signals that plagued earlier implementations [11] [3]. The method's smaller probe size facilitates better penetration into microbial cells without requiring aggressive permeabilization treatments that can compromise cell integrity [11].

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison in Environmental Samples

| Performance Metric | HCR-FISH | CARD-FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Detection in Marine Sediments | Successful with optimized protocol [11] | Established but requires permeabilization [10] |

| False-Positive Signals | Manageable with proper blocking [11] | Generally low with peroxidase inactivation [11] |

| Protocol Duration | Shorter incubation times [11] [10] | Longer due to multiple incubation steps [11] |

| Gram-Positive Detection | May require permeabilization optimization [10] | Challenging without extensive permeabilization [10] |

| Sample Versatility | High across diverse sample types [14] | Limited by permeabilization requirements [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH requires specific reagent systems optimized for each methodology. The following essential materials represent critical components for achieving reliable, reproducible results in microbial detection applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Signal Amplification Methodologies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| HCR Initiator Probes | Split-initiator DNA oligonucleotides (~35-45 nt) [15] [14] | Target-specific probes that trigger hybridization chain reaction upon binding |

| HCR Amplifier Hairpins | Fluorescently labeled H1 and H2 hairpins (B1-B5 initiator systems) [14] | Form amplifying nanostructures with fluorophores; reusable across experiments |

| HCR Buffers | Hybridization buffer, wash buffer, amplification buffer [14] | Optimized solutions for specific hybridization and signal amplification |

| CARD-FISH Probes | HRP-labeled oligonucleotide probes [11] | Enzyme-conjugated probes for catalytic signal deposition |

| Tyramide Reagents | Fluorescently labeled tyramides [11] | Enzyme substrates that precipitate at target sites for signal amplification |

| Permeabilization Enzymes | Lysozyme, proteinase K [10] | Critical for CARD-FISH to enable HRP probe entry into cells |

| Blocking Reagents | Dextran sulfate, blocking reagents [10] | Reduce non-specific binding in complex environmental samples |

| Counterstains | DAPI, SYBR Green [11] | Provide reference staining for total microbial cells |

The comparative analysis of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH reveals a nuanced landscape where methodological selection depends heavily on specific research requirements and sample characteristics. CARD-FISH remains a powerful option for maximum signal amplification in challenging samples with extremely low target abundance, despite its technical complexities and potential for nucleic acid degradation [11] [10]. Meanwhile, HCR-FISH offers compelling advantages in flexibility, specificity, and protocol simplicity, particularly for applications requiring multiplexed detection or where enzyme-based methods face limitations [11] [14].

Future developments in signal amplification technology will likely focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities, reducing background interference in complex matrices, and streamlining protocols for high-throughput applications. The emergence of unified platforms like OneSABER, which enables combination of different signal development and amplification techniques within a single probe system, represents a promising direction for the field [15]. Such integrated approaches may eventually transcend the current dichotomy between HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH, providing researchers with modular systems that can be customized for specific applications while maintaining consistency in probe design and validation.

For researchers selecting between these methodologies, the decision framework should consider target abundance, sample complexity, required throughput, and available technical expertise. CARD-FISH may be preferable for maximum sensitivity in low-biomass environments, while HCR-FISH offers superior flexibility and specificity for diverse experimental contexts. As both technologies continue to evolve, their complementary strengths will undoubtedly expand the frontiers of microbial detection and visualization across diverse research applications.

Historical Development and Technological Evolution of Both Methods

For decades, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has been a cornerstone technique in microbial ecology, enabling the identification, visualization, and quantification of microorganisms within their natural environments. However, a significant limitation emerged when applying standard FISH to oligotrophic habitats, such as marine seawater and sediments. The microorganisms in these environments are often small, slow-growing, or inactive, resulting in low cellular rRNA content. This makes them notoriously difficult to detect with conventional FISH, as the fluorescence signal intensity is directly proportional to the cellular rRNA concentration [10]. This fundamental sensitivity problem catalyzed the development of advanced signal amplification methods, primarily the Catalyzed Reporter Deposition-FISH (CARD-FISH) and the Hybridization Chain Reaction-FISH (HCR-FISH), which have since evolved to push the boundaries of in situ detection [10] [3].

This guide objectively compares the performance of HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH, framing the analysis within a broader thesis on evaluating their sensitivity for environmental research. It provides a detailed examination of their technological evolution, operational mechanisms, and direct experimental comparisons, supported by quantitative data and protocol details to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate method for their applications.

Historical Development and Technological Trajectories

The Advent of CARD-FISH

CARD-FISH was introduced as a powerful in situ signal amplification method utilizing the enzyme horseradish peroxidase (HRP). In this technique, oligonucleotide probes are labeled with HRP. After the probe hybridizes to its target, the HRP enzyme catalyzes the deposition of numerous fluorescently labeled tyramide molecules at the site of hybridization. This reaction results in a massive signal amplification, reported to yield a 26- to 41-fold higher fluorescence signal than standard FISH. This breakthrough established CARD-FISH as the go-to method for detecting microorganisms in oligotrophic habitats like marine waters and soils [10].

The Emergence of HCR-FISH

HCR-FISH emerged more recently as an innovative and sensitive alternative. This method is based on an enzyme-free, isothermal hybridization chain reaction. In HCR-FISH, a primary "initiator" probe binds to the target rRNA. This initiator then triggers a cascading, self-assembly of two fluorescently labeled DNA "hairpin" amplifiers, forming a long, nicked double helix that accumulates a large number of fluorophores at the target site [3]. Early adaptations of HCR-FISH demonstrated up to an 8-fold higher sensitivity than standard FISH, positioning it as a potential alternative to CARD-FISH [10].

Evolutionary Improvements: quickHCR-FISH

The initial HCR-FISH protocol had drawbacks, including long incubation times for the chain reaction and difficulty detecting Gram-positive bacteria without prior cell permeabilization. This led to the development of improved versions, such as "quickHCR-FISH." This modification used optimized hybridization and amplification buffers containing a blocking reagent and dextran sulfate, along with double-labeled amplifier probes. These changes resulted in higher signal intensity and a significantly shorter amplification time, making HCR-FISH a more robust and practical alternative, particularly for cases where strong cell permeabilization or enzymatic reactions should be avoided [10].

Table 1: Key Milestones in the Technological Evolution of CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH

| Time Period | CARD-FISH (Enzyme-Based) | HCR-FISH (Enzyme-Free) |

|---|---|---|

| 1990s-2000s | Introduction of the method using horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and tyramide signal amplification [10]. | --- |

| ~2010 | Established as the standard for sensitive detection in oligotrophic environments [10]. | First combination of HCR with FISH for bio-imaging reported [3]. |

| ~2015 | --- | First application on environmental microbes (e.g., activated sludge) [3]. Early protocol showed 8x higher sensitivity than FISH but had long incubation times [10]. |

| 2015-Present | Continued use as a gold standard, but known limitations persist (permeabilization, endogenous peroxidase) [10]. | Development of "quickHCR-FISH" with faster protocols and better buffers [10]. Optimization for challenging samples like marine sediments [3]. |

Comparative Analysis of Principles and Workflows

The core difference between CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH lies in their signal amplification mechanisms: CARD-FISH relies on an enzymatic reaction, while HCR-FISH uses a controlled, autonomous DNA self-assembly.

CARD-FISH Workflow and Critical Steps

The CARD-FISH protocol involves several crucial and delicate steps [10]:

- Cell Permeabilization: A critical and problematic pre-treatment. The large size of the HRP-labeled oligonucleotide probes (~40 kDa) necessitates enzymatic permeabilization of the cell wall to facilitate entry. This step requires optimization for different sample types and can be harsh on cells.

- Inactivation of Endogenous Peroxidases: Required to prevent false-positive signals, often using H₂O₂, which can degrade nucleic acids [3].

- Hybridization: HRP-labeled probes hybridize to the target rRNA.

- Signal Amplification: HRP catalyzes the deposition of numerous fluorescent tyramide molecules.

- Detection: Fluorescence is visualized under an epifluorescence microscope.

HCR-FISH Workflow and Critical Steps

The HCR-FISH protocol is enzymatically independent, which simplifies several aspects [10] [3]:

- Fixation: Standard fixation of cells (e.g., with paraformaldehyde).

- Hybridization: Unlabeled initiator probes hybridize to the target rRNA. Notably, these probes are smaller than HRP-labeled probes, facilitating better cell penetration without the need for aggressive permeabilization [3].

- Amplification: The addition of two fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins (Amplifier A and B). The initiator probe triggers a cascading hybridization between the two hairpins, forming a fluorescent polymer at the target site.

- Detection: Fluorescence is visualized under an epifluorescence microscope.

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and critical differences in the signaling pathways of both methods.

Direct Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Protocols

Direct experimental comparisons between the two methods, particularly involving the improved quickHCR-FISH, provide crucial performance data for researchers.

Table 2: Direct Experimental Comparison: CARD-FISH vs. HCR-FISH

| Performance Metric | CARD-FISH | quickHCR-FISH | Experimental Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Increase vs. FISH | 26- to 41-fold [10] | Up to 8-fold [10] | Early HCR showed lower amplification than CARD-FISH. |

| Relative Signal Intensity | Baseline | 1.3-fold higher [10] | quickHCR-FISH signal was 30% brighter than CARD-FISH when detecting Gramella forsetii. |

| Amplification Time | ~30-60 minutes (Tyramide incubation) [10] | 30 minutes [10] | QuickHCR-FISH offers a faster amplification step. |

| Cell Permeabilization | Required (enzymatic) [10] [3] | Not required for Gram-negative [10] | HCR's smaller probes bypass a major CARD-FISH bottleneck. |

| Endogenous Enzyme Inactivation | Required (H₂O₂ treatment) [10] [3] | Not required [3] | H₂O₂ can degrade target nucleic acids [3]. |

| Application on Marine Samples | Established [10] | Successful [10] | Both can be used, but HCR avoids permeabilization/CARD reaction issues [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

To ensure reproducibility, below are the detailed methodologies from critical comparison experiments.

Protocol 1: quickHCR-FISH vs. CARD-FISH on Marine Bacterium (Gramella forsetii) [10]

- Sample Preparation: G. forsetii cells were harvested from the logarithmic growth phase and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 hours at 4°C.

- quickHCR-FISH Protocol:

- Hybridization Buffer: 30% formamide, 0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 0.01% SDS, 1% blocking reagent, 10% dextran sulfate. Initiator probe concentration was 10 µM.

- Hybridization: 4 hours at 46°C.

- Amplification: Incubation with 60 nM of each fluorescently labeled hairpin amplifier (double-labeled) in amplification buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- CARD-FISH Protocol:

- Permeabilization: Cells were embedded in agarose gel and permeabilized with lysozyme solution.

- Inactivation: Endogenous peroxidases were inactivated with 10 mM HCl and 1% H₂O₂.

- Hybridization: HRP-labeled probe in hybridization buffer (30% formamide) at 35°C for 4 hours.

- Amplification: Incubation with fluorescently labeled tyramide in amplification buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Result: quickHCR-FISH demonstrated a 1.3-fold higher fluorescence signal intensity than CARD-FISH for the same target organism.

Protocol 2: HCR-FISH Optimization for Sediment Microbes [3]

- Critical Modification: Increasing the initiator probe concentration in the hybridization buffer from the original 1 μmol/L to 10 μmol/L was essential for obtaining a clear and intensive signal sufficient to identify the exact location and shape of individual cells (E. coli was used as a model).

- Challenge: Early attempts to apply HCR-FISH to sediments were unsuccessful due to strong false-positive signals, likely from probe adsorption to abiotic particles.

- Solution: The optimized protocol involved modifications to sample pretreatment methods and hybridization buffer composition to reduce false positives, successfully enabling visualization of microbes in marine sediments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH relies on a specific set of reagents and materials. The table below details these key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH

| Item | Function/Role | CARD-FISH | HCR-FISH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Probe | Binds to target rRNA sequence. | HRP-labeled oligonucleotide (~40 kDa) [10]. | Unlabeled initiator oligonucleotide (smaller size) [3]. |

| Signal Amplifier | Amplifies the fluorescence signal. | Fluorescently labeled tyramide [10]. | Fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins (Amplifier A & B) [3]. |

| Permeabilization Agent | Allows probe entry into the cell. | Lysozyme or other enzymes (critical step) [10]. | Typically not required for many bacteria [10]. |

| Blocking Reagent | Reduces non-specific binding. | Used in buffers to improve specificity [10]. | Used in hybridization buffer (e.g., in quickHCR-FISH) [10]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Creates conditions for specific probe binding. | Standard buffer with formamide [10]. | Optimized buffer with dextran sulfate & blocking reagent [10]. |

| Microscope | For signal visualization. | Epifluorescence microscope [16]. | Epifluorescence microscope [3]. |

The historical evolution of in situ hybridization for detecting environmental microbes has been driven by the need for greater sensitivity and practicality. CARD-FISH, with its powerful enzymatic amplification, broke through the limitations of standard FISH and remains a highly sensitive benchmark. However, its drawbacks—specifically the requirement for meticulous permeabilization and the risk of endogenous enzyme activity—have driven the development of enzyme-free alternatives.

HCR-FISH, particularly in its optimized "quick" form, represents a significant technological evolution. It offers a compelling alternative with several practical advantages: simpler sample preparation, no enzyme-related steps, and faster amplification. While early versions had lower absolute signal amplification than CARD-FISH, recent optimizations have resulted in protocols where HCR-FISH can not only match but in some cases exceed the performance of CARD-FISH for specific applications, such as detecting Gram-negative bacteria in marine samples [10].

The choice between these methods ultimately depends on the specific research context. For projects where the highest possible signal amplification is critical and sample types are well-characterized for permeabilization, CARD-FISH remains a powerful choice. For broader screening, studies of novel organisms where permeabilization is unknown, or when simplicity and speed are prioritized, HCR-FISH has emerged as a robust, sensitive, and often more user-friendly alternative. Future developments will likely continue to enhance the sensitivity, multiplexing capability, and accessibility of both techniques.

Key Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Each Approach

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a cornerstone technique in environmental microbiology and medical diagnostics for visualizing and identifying microbial cells. To overcome the limitations of traditional FISH—particularly its limited sensitivity for detecting microorganisms with low ribosomal RNA content—researchers have developed powerful signal amplification methods. Among these, Catalyzed Reporter Deposition-FISH (CARD-FISH) and Hybridization Chain Reaction-FISH (HCR-FISH) represent two of the most advanced approaches [11] [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, framing their performance within sensitivity research to inform method selection by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CARD-FISH: Enzyme-Mediated Signal Amplification

CARD-FISH combines the principles of FISH with catalytic reporter deposition for signal amplification. The technique employs oligonucleotide probes labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). When these probes hybridize to their target RNA sequences, the HRP enzyme catalyzes the deposition of numerous fluorescently labeled tyramide molecules onto the probe-target complex [17]. This enzymatic amplification results in a massive increase in fluorescence signal at the target site, enabling the detection of microbial cells with low rRNA content that would be undetectable with conventional FISH [18].

HCR-FISH: Enzyme-Free Signal Amplification

HCR-FISH utilizes an isothermal, enzyme-free signal amplification mechanism based on DNA hairpin oligonucleotides. In this system, initiator probes hybridize to the target rRNA, triggering a cascading hybridization event between two fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins [11] [2]. This process forms elongated double-stranded DNA polymers that accumulate at the target site, significantly amplifying the fluorescence signal without requiring enzymatic reactions [11]. The latest generation of this technology (HCR v3.0) employs split-initiator probes that provide automatic background suppression, dramatically improving signal-to-noise ratios [2].

Comparative Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences between CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH based on experimental data:

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CARD-FISH vs. HCR-FISH

| Performance Metric | CARD-FISH | HCR-FISH | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | 8.9-54 rRNA copies/cell [18] | ~2-4 fold lower than CARD-FISH (estimated) | Competitive FISH with E. coli; gel quantification |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio | High with optimized protocols | ≈50-60 fold suppression with v3.0 [2] | Whole-mount embryo imaging; in situ validation |

| Amplification Mechanism | Enzymatic (HRP-tyramide) [17] | Enzyme-free, isothermal HCR [11] | Biochemical protocol analysis |

| Probe Permeability | Limited (HRP ~40 kDa) [11] | Excellent (small DNA probes) [11] | Molecular weight comparison |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Moderate | High (up to 5 targets simultaneously) [2] | Multiplexed mRNA imaging studies |

| Protocol Duration | ~2 days [4] | ~1 day (shorter than CARD-FISH) [11] | Protocol timing comparisons |

Advantages and Limitations Analysis

CARD-FISH: Strengths and Constraints

Key Advantages:

- Superior Sensitivity: CARD-FISH demonstrates the highest sensitivity of both methods, capable of detecting as few as 8.9±1.5 to 54±7 16S rRNA molecules per E. coli cell, representing a 26- to 41-fold improvement over conventional FISH [18].

- Proven Track Record: Extensive validation in diverse environments, including aquatic ecosystems, soil microbiology, and extreme environments [4] [17].

- Compatible with Autofluorescent Samples: Effective even in samples with significant background autofluorescence due to powerful signal amplification [18].

Inherent Limitations:

- Permeability Challenges: The large molecular size of HRP (~40 kDa) requires additional permeabilization steps (e.g., lysozyme treatment) to enable probe entry into cells [11] [4].

- Endogenous Peroxidase Interference: Requires hydrogen peroxide treatment to inactivate cellular peroxidases, which may degrade target nucleic acids [11].

- Limited Probe Versatility: HRP-labeled probes are more complex and expensive to modify compared to DNA-based probes [11].

HCR-FISH: Strengths and Constraints

Key Advantages:

- Excellent Cell Permeability: Small DNA probes penetrate cells efficiently without additional permeabilization steps [11].

- Flexible Probe System: Initiator probes are unlabeled, allowing easy adaptation to new targets without redesigning fluorescent components [11].

- Automatic Background Suppression: Third-generation HCR (v3.0) with split-initiator probes provides ≈50-fold suppression of amplified background, enabling use of unoptimized probe sets [2].

- Preserved Cellular Integrity: Eliminates hydrogen peroxide treatment, better preserving target RNA and cellular structure [11].

Inherent Limitations:

- Moderately Lower Sensitivity: Shows approximately 2-4 fold lower signal conversion compared to full-initiator systems, though this is offset by dramatically reduced background [2].

- Environmental Sample Challenges: Increased potential for false-positive signals from probe adsorption to abiotic particles in complex matrices like sediments [11].

- Protocol Optimization Needs: Requires careful optimization of hybridization conditions, particularly for challenging environmental samples [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed CARD-FISH Protocol

The following protocol for CARD-FISH with prokaryotic cells has been adapted from established methodologies [18] [4]:

- Fixation: Harvest cells and fix in 3% formaldehyde solution for 8 hours [18].

- Permeabilization: Apply lysozyme solution (3 mg/ml) at 4°C for 15 minutes, followed by incubation in 0.01 M HCl at room temperature for 30 minutes [18] [4].

- Hybridization: Hybridize with HRP-labeled oligonucleotide probes (e.g., EUB338-I) in buffer containing 20-40% formamide at 46°C for 3 hours [18].

- Signal Amplification: Incubate with substrate mixture containing Cy3-labeled tyramide and amplification buffer at 46°C [18].

- Detection: Counterstain with DAPI and visualize by epifluorescence or confocal microscopy.

Detailed HCR-FISH Protocol

The optimized HCR-FISH protocol for environmental samples includes these key steps [11] [2]:

- Fixation: Fix cells following standard FISH protocols.

- Hybridization: Hybridize with initiator probes at increased concentration (10 μmol/L) in appropriate hybridization buffer [11].

- Amplification: Add fluorescently labeled H1 and H2 hairpin amplifiers simultaneously for multiplexed detection [2].

- Washing and Imaging: Remove excess hairpins through washing and image with appropriate fluorescence microscopy.

For HCR v3.0 with automatic background suppression, replace standard probes with split-initiator probe pairs that each carry half of the HCR initiator sequence [2].

Protocol Workflow Comparison

The diagram below contrasts the key procedural differences between the two methods:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues key reagents and their functions for implementing these techniques:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Formaldehyde (3%) [18] | Preserves cellular structure and immobilizes target nucleic acids |

| Permeabilization Enzymes | Lysozyme, Achromopeptidase [4] | Enables HRP-probe entry in CARD-FISH (not needed for HCR-FISH) |

| HRP-Labeled Probes | EUB338-I-HRP [18] | Target-specific hybridization with enzymatic label for CARD-FISH |

| HCR Initiator Probes | Split-initiator probe pairs [2] | Target recognition and HCR initiation for HCR-FISH v3.0 |

| HCR Hairpin Amplifiers | H1 and H2 hairpins [11] [2] | Fluorescent DNA hairpins for signal amplification in HCR-FISH |

| Tyramide Reagents | Cy3-labeled tyramide [18] | Fluorescent substrate for HRP-mediated deposition in CARD-FISH |

| Hybridization Buffers | Formamide-containing buffers [11] [18] | Controls stringency of hybridization conditions |

| Counterstains | DAPI [11] | General nucleic acid stain for reference imaging |

Research Applications and Selection Guidelines

Application-Specific Recommendations

- Low-Biomass Environments: CARD-FISH is preferable for oligotrophic environments or dormant cells with extremely low rRNA content due to its superior sensitivity [18].

- Complex Environmental Samples: HCR-FISH v3.0 excels in sediments, soils, and biofilms where background suppression is critical [11] [19].

- Multiplexing Studies: HCR-FISH provides advantages for simultaneous detection of multiple targets without sequential hybridization [2].

- Delicate Cellular Structures: HCR-FISH is preferred when preserving mRNA integrity is essential, as it eliminates harsh peroxidase inactivation steps [11].

- High-Throughput Applications: HCR-FISH's shorter protocol duration (~1 day vs. ~2 days for CARD-FISH) benefits processing multiple samples [11].

Emerging Technological Developments

Third-generation HCR-FISH with automatic background suppression represents the latest advancement in this field [2]. This innovation addresses a fundamental limitation of earlier amplification methods by ensuring that non-specifically bound probes don't generate amplified background. The split-initiator probe design colocalizes two probe halves on the target mRNA, triggering amplification only when both bind specifically, thereby improving robustness and reducing the need for extensive probe optimization [2].

CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH each offer distinct advantages for sensitive microbial detection. CARD-FISH remains the gold standard for maximum sensitivity in challenging, low-biomass samples. In contrast, HCR-FISH provides superior versatility, easier implementation, and increasingly robust performance with automatic background suppression in v3.0. The choice between these methods should be guided by specific research needs: ultimate sensitivity favoring CARD-FISH versus ease of use, flexibility, and background suppression favoring HCR-FISH. As both technologies continue to evolve, they will further empower researchers to explore microbial diversity, function, and interactions at unprecedented resolution.

Practical Implementation: Protocol Design and Sample-Specific Applications

This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of the Hybridization Chain Reaction-Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (HCR-FISH) protocol alongside the Catalyzed Reporter Deposition-FISH (CARD-FISH) method, focusing on their sensitivity and application in microbial detection and research.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with rRNA-targeted probes is a cornerstone technique in microbial ecology for identifying and quantifying microorganisms in their native context [10]. However, standard FISH often lacks sufficient sensitivity for detecting microbes with low ribosomal RNA content, such as those in oligotrophic habitats like marine water and sediments [10] [3]. To address this limitation, signal amplification methods have been developed. CARD-FISH utilizes horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled probes and tyramide signal amplification to achieve a 26- to 41-fold higher fluorescence signal than standard FISH [10]. Meanwhile, HCR-FISH employs an enzyme-free, hybridization-based chain reaction to typically provide an up to 8-fold signal increase [10]. The following sections will dissect the standard HCR-FISH protocol and objectively compare its performance to CARD-FISH, providing a clear framework for researchers to select the appropriate method.

The Standard HCR-FISH Protocol: A Detailed Workflow

The HCR-FISH protocol is typically completed over three days. The process involves cell fixation, permeabilization, hybridization with initiator probes, signal amplification with fluorescent hairpins, and final washing steps before visualization [20].

Day 1: Sample Preparation and Hybridization

- Fixation: Cells are harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes at room temperature to preserve cellular structure and nucleic acids. After fixation, cells are washed with PBS [20].

- Permeabilization: Cells are treated with 0.5% Tween for 15 minutes at room temperature. This step is critical for enabling the entry of probes into the cells. A subsequent PBS wash is performed [20].

- Pre-hybridization: Cells are equilibrated with a pre-made hybridization buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C [20].

- Overnight Hybridization: The supernatant is removed, and cells are resuspended in a probe solution containing initiator probes (typically at 5-10 nM concentration) in hybridization buffer. The incubation proceeds overnight (12-16 hours) at 37°C [14] [20]. Note that for environmental samples, increasing the initiator probe concentration to 10 μmol/L has been shown to significantly enhance signal clarity [3] [11].

Day 2: Washing and Signal Amplification

- Post-Hybridization Washing: The probe solution is removed, and cells are washed with a pre-warmed probe wash buffer for 15 minutes at 37°C to remove unbound probes. This is followed by a wash with 5X SSCT (Saline-Sodium Citrate buffer with Tween-20) at room temperature [20].

- Pre-amplification: Cells are incubated in amplification buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature [20].

- Hairpin Preparation: While the pre-amplification step is ongoing, the two fluorescently labeled DNA hairpin molecules (H1 and H2) are prepared. Each hairpin is snap-cooled separately by heating to 95°C for 90 seconds and then allowing them to cool at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. This ensures they form the correct metastable hairpin structure [14] [20].

- Overnight Amplification: The pre-amplification buffer is replaced with a solution containing the snap-cooled H1 and H2 hairpins in fresh amplification buffer. The amplification reaction occurs overnight in the dark at room temperature [20].

Day 3: Final Washing and Visualization

- Removal of Unbound Hairpins: The hairpin solution is removed, and cells undergo two washes with 5X SSCT (30 minutes and 5 minutes, respectively) in the dark to eliminate any unamplified hairpins [20].

- Resuspension and Storage: The final cell pellet is resuspended in PBS and should be stored at 4°C in the dark until imaging or analysis by flow cytometry [20].

The following diagram illustrates the core biochemical mechanism of the HCR process that occurs during the amplification step.

Objective Performance Comparison: HCR-FISH vs. CARD-FISH

The choice between HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH involves trade-offs between sensitivity, practicality, and application-specific requirements. The table below summarizes a direct comparison based on key experimental parameters.

| Performance Characteristic | HCR-FISH | CARD-FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplification Factor | Up to 8-fold higher than standard FISH [10] | 26- to 41-fold higher than standard FISH [10] |

| Probe Size | Small oligonucleotides [3] | Large HRP-labeled oligonucleotides (~40 kDa) [3] |

| Cell Permeabilization | Standard treatment often sufficient [3] | Often requires harsh enzymatic permeabilization [10] [3] |

| Endogenous Enzyme Inactivation | Not required [3] | Required (e.g., using H₂O₂) [3] |

| Protocol Duration | Less time-consuming [3] | More time-consuming due to additional steps [10] |

| Key Advantages | Easier probe customization, milder protocol, preserves RNA integrity [3] | Higher absolute signal amplification [10] |

| Key Limitations | Lower absolute signal gain, potential for false positives in complex samples [3] | Complex protocol, risk of nucleic acid degradation, limited probe entry [10] [3] |

Supporting Experimental Data and Protocol Optimizations

- Sensitivity in Environmental Samples: A study focusing on marine sediments found that a modified "quickHCR-FISH" protocol, which uses improved buffers and double-labeled amplifier probes, could serve as a true alternative to CARD-FISH, especially when strong cell permeabilization should be avoided [10].

- Probe Concentration is Critical: Research demonstrates that a primary factor for successful HCR-FISH is initiator probe concentration. While the original protocol used 1 μmol/L, increasing the concentration to 10 μmol/L was necessary to generate intense and clear signals sufficient for identifying individual cells in environmental samples [3] [11].

- Reducing False Positives: A significant challenge for HCR-FISH in sediment samples is false-positive signals from probe absorption to abiotic particles. This can be mitigated by optimizing sample pre-treatment methods, hybridization buffer formulas, and implementing image processing to enhance the distinction between microbial cells and particles stained with DAPI [3].

Essential Reagents for HCR-FISH

A successful HCR-FISH experiment relies on a set of core reagents. The table below lists these key components and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Fixative agent that cross-links and preserves cellular structures [20]. |

| Permeabilization Agent (e.g., Tween-20) | Detergent that creates pores in the cell membrane, allowing probe entry [20]. |

| Initiator Probes | Unlabeled oligonucleotides that bind the target rRNA and contain the HCR initiator sequence [3]. |

| Hairpin H1 & H2 | Fluorescently labeled, metastable DNA hairpins that self-assemble into a polymerization nanoscale assembly upon initiation [14] [20]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Contains formamide and salts to create stringent conditions for specific probe binding [14] [20]. |

| Wash Buffer | Removes excess and non-specifically bound probes after hybridization [20]. |

| Amplification Buffer | Provides ideal ionic conditions for the HCR hairpin assembly process [20]. |

| SSCT (Saline-Sodium Citrate with Tween) | Washing buffer used after amplification to remove unbound hairpins [20]. |

The complete workflow, from fixation to final analysis, is visualized in the following diagram.

Both HCR-FISH and CARD-FISH are powerful tools that overcome the sensitivity limitations of traditional FISH. CARD-FISH offers a higher degree of signal amplification, making it a strong candidate for extremely challenging targets. However, HCR-FISH presents a compelling alternative with significant practical advantages: its enzyme-free, isothermal nature simplifies the protocol, its smaller probes facilitate cell entry, and it avoids the use of harsh chemicals that can compromise RNA integrity. The development of optimized protocols, such as quickHCR-FISH and the critical adjustment of initiator probe concentration, has further solidified its position as a robust and reliable method for identifying microbes, even in complex environmental samples like marine sediments. The choice between them should be guided by the specific requirements of the experiment, weighing the need for maximum signal intensity against the benefits of a more flexible and milder assay.

Catalyzed Reporter Deposition - Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (CARD-FISH) is a powerful technique that significantly enhances detection sensitivity for microorganisms with low ribosomal content in environmental samples [4]. Unlike standard FISH with directly labeled oligonucleotides, CARD-FISH utilizes horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled probes and tyramide signal amplification to achieve 26- to 41-fold higher fluorescence signals [21] [10]. However, this enhanced sensitivity comes with a critical technical challenge: the HRP enzyme molecule must penetrate target cells while preserving cellular integrity during rigorous permeabilization treatments [21]. This article examines the precise permeabilization requirements for successful CARD-FISH, directly comparing its technical demands against the emerging hybridization chain reaction (HCR-FISH) methodology.

Core Principles: CARD-FISH Versus HCR-FISH

The fundamental difference between these amplification techniques lies in their mechanism and consequent permeabilization requirements.

CARD-FISH Mechanism

CARD-FISH employs HRP-labeled probes that catalyze the deposition of numerous fluorescently labeled tyramide molecules at the hybridization site [21]. This enzymatic amplification creates intense fluorescence signals but necessitates extensive cell wall permeabilization to allow the large HRP enzyme (approximately 44 kDa) to enter bacterial cells [21] [10].

HCR-FISH Mechanism

HCR-FISH utilizes enzyme-free signal amplification through hybridization chain reactions, where metastable DNA hairpin probes initiate a cascade of hybridization events upon binding to the target [10]. This method employs smaller DNA probes that penetrate cells more readily, potentially avoiding the harsh permeabilization treatments required for CARD-FISH [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of CARD-FISH and HCR-FISH Technologies

| Characteristic | CARD-FISH | HCR-FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Mechanism | Enzyme-catalyzed (HRP) tyramide deposition | Enzyme-free hybridization chain reaction |

| Probe Size | Large HRP-labeled oligonucleotides | Smaller DNA hairpin probes |

| Key Permeabilization Requirement | Lysozyme treatment essential | May not require enzymatic permeabilization |

| Endogenous Enzyme Interference | Requires peroxidase inactivation | No enzyme interference concerns |

| Typical Signal Amplification | 26-41x compared to standard FISH [10] | Up to 8x compared to standard FISH [10] |

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows highlight the critical permeabilization step in CARD-FISH that carries risk of species-selective cell loss.

Critical Permeabilization Protocols for CARD-FISH

Standardized CARD-FISH Permeabilization Procedure

The permeabilization protocol for CARD-FISH requires meticulous optimization to balance cell permeability with structural integrity [21]. The following step-by-step procedure has been validated for marine bacterioplankton and benthic microorganisms:

Sample Embedding: After concentration onto membrane filters, embed filters in low-gelling-point agarose (0.2% wt/vol) to prevent cell loss during subsequent treatments. Dry filters face up on glass slides at 35°C, then dehydrate in 96% ethanol for 1 minute [21].

Endogenous Peroxidase Inactivation (for sediment samples): Treat samples overnight with 0.1% (wt/vol) active diethyl pyrocarbonate in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C to inhibit endogenous peroxidases that cause background signal [21].

Lysozyme Permeabilization: Incubate filters in lysozyme solution (10 mg ml⁻¹ in 0.05 M EDTA, 0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) at 37°C for 30-90 minutes. The optimal duration must be determined empirically for different sample types [21].

Post-Permeabilization Processing: Wash filters twice in molecular grade water, followed by dehydration in 96% ethanol for 1 minute. Air dry filters before proceeding with hybridization [21].

Permeabilization Optimization Evidence

Experimental data demonstrates that the agarose embedding step prevents significant cell loss during lysozyme treatment. Without embedding, 90-minute lysozyme incubation caused substantial cell loss, while embedded samples maintained cell counts comparable to untreated controls [21]. This embedding step is therefore critical for quantitative applications.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Detection Efficiency Between FISH Techniques

| Sample Type | Standard FISH with MONOLABELED Probe (EUB338-mono) | CARD-FISH with HRP-Labeled Probe (EUB338-HRP) | HCR-FISH (quickHCR Protocol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal North Sea Bacterioplankton | 19-66% (mean 48%) of total cell counts [21] | 85-100% (mean 94%) of total cell counts [21] | Not specified in search results |

| Wadden Sea Sediment Communities | 25-71% (mean 44%) of total cell counts [21] | 53-100% (mean 81%) of total cell counts [21] | Not specified in search results |

| SAR86 Clade in Marine Samples | Undetectable [21] | 3-13% (mean 7%) of total cell counts [21] | Not specified in search results |

| Gramella forsetii (Pure Culture) | Not specified | Not specified | High signal intensity with modified buffers [10] |

| Gram-Positive Environmental Bacteria | Limited detection without permeabilization [10] | Requires optimized lysozyme treatment [21] | Requires cell permeabilization for detection [10] |

Advanced CARD-FISH Applications and Methodological refinements

Protistan Ecology Applications

CARD-FISH has been adapted for studying phagotrophic protists in aquatic environments, revealing previously underestimated groups including heterotrophic cryptophyte lineages (CRY1), cercozoans, katablepharids, and MAST lineages [4]. When combined with tracer techniques and double CARD-FISH, researchers can visualize food vacuole contents of specific flagellate groups, challenging the conventional view of these organisms as predominantly bacterivores [4].

mRNA-Targeting Applications