Hox Compound Mutants in Mice: Unraveling Genetic Redundancy and Regulatory Networks in Limb Development

This article synthesizes current methodologies and findings from the generation and analysis of Hox compound mutant mice, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers investigating limb development.

Hox Compound Mutants in Mice: Unraveling Genetic Redundancy and Regulatory Networks in Limb Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current methodologies and findings from the generation and analysis of Hox compound mutant mice, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers investigating limb development. It explores the foundational principles of Hox gene function in establishing the limb axes, details advanced techniques for creating multi-gene knockouts, and addresses the challenge of genetic redundancy. The content further covers strategies for phenotypic validation and cross-species comparative genomics, offering insights into the complex regulatory networks that govern limb patterning. Aimed at developmental biologists, geneticists, and professionals in biomedical research, this review serves as a strategic guide for designing and interpreting studies on Hox gene function, with implications for understanding congenital limb defects and evolutionary biology.

Decoding the Hox Code: Principles of Gene Regulation in Limb Patterning

Hox genes are a family of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors that play a fundamental role in patterning the anterior-posterior (AP) body axis during embryonic development of bilaterian animals [1] [2]. These genes encode proteins containing a characteristic 60-amino-acid DNA-binding domain known as the homeodomain, which allows them to bind to specific regulatory sequences and control the expression of numerous downstream target genes [2]. In vertebrates, Hox genes are notable for their unique genomic organization—they are arranged in tight clusters on different chromosomes, a relic of ancient whole-genome duplication events [3] [4].

The mouse (Mus musculus), as a model organism, has been instrumental in deciphering the functions of Hox genes in mammalian development. Mice possess 39 Hox genes distributed across four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) located on different chromosomes [4]. During early vertebrate evolution, two rounds of whole-genome duplication occurred from a single ancestral cluster, leading to the four-cluster organization observed in mammals today [3]. The paralogous groups, comprising genes descended from a common ancestor within the cluster, exhibit functional redundancy and overlapping expression patterns, which have complicated their genetic analysis but also provide robustness to the developmental system [1] [4].

This application note provides researchers with a comprehensive overview of the Hox gene toolkit in mice, with a specific focus on generating and analyzing compound mutants for investigating limb development. We present structured data on paralog groups, detailed protocols for genetic manipulation, and visual frameworks to guide experimental design.

Hox Gene Organization and Nomenclature in Mice

Genomic Organization of Hox Clusters

The 39 Hox genes in mice are organized into four clusters, each residing on a different chromosome. The clusters are labeled HoxA (chromosome 6), HoxB (chromosome 11), HoxC (chromosome 15), and HoxD (chromosome 2) [4]. Each cluster contains 9-11 genes that are transcribed from the same DNA strand in each cluster, maintaining a remarkable evolutionary conservation across bilaterian animals [2] [4].

A defining feature of Hox gene expression is temporal and spatial collinearity—genes located at the 3' end of a cluster are expressed earlier and in more anterior regions of the embryo, while genes at the 5' end are expressed later and in more posterior regions [4]. This collinear expression pattern allows Hox genes to provide positional information along the AP axis, thereby specifying the identity of different body regions and structures, including the limbs [1] [4].

Paralog Groups and Functional Classification

Hox genes across the four clusters are classified into 13 paralog groups (PG1-13) based on sequence similarity and their position within the clusters [4]. Due to gene loss events during evolution, no single cluster contains a representative from all 13 paralog groups. The table below summarizes the complete complement of Hox genes in the mouse genome, organized by cluster and paralog group.

Table 1: Hox Gene Clusters and Paralog Groups in the Mouse Genome

| Paralog Group | HoxA Cluster | HoxB Cluster | HoxC Cluster | HoxD Cluster | General Expression Domain along A-P Axis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG1 | Hoxa1 | Hoxb1 | - | - | Hindbrain / Rhombomere 4 |

| PG2 | Hoxa2 | Hoxb2 | - | - | Hindbrain |

| PG3 | Hoxa3 | Hoxb3 | - | - | Hindbrain / Posterior Pharynx |

| PG4 | Hoxa4 | Hoxb4 | Hoxc4 | Hoxd4 | Anterior Vertebrae |

| PG5 | Hoxa5 | Hoxb5 | Hoxc5 | Hoxd5 | Posterior Vertebrae / Forelimb Region |

| PG6 | Hoxa6 | Hoxb6 | Hoxc6 | - | Posterior Vertebrae / Forelimb Region |

| PG7 | Hoxa7 | Hoxb7 | Hoxc7 | - | Posterior Vertebrae |

| PG8 | - | Hoxb8 | Hoxc8 | - | Posterior Vertebrae |

| PG9 | Hoxa9 | Hoxb9 | Hoxc9 | Hoxd9 | Lumbar Vertebrae / Hindlimb Region |

| PG10 | Hoxa10 | Hoxb10 | Hoxc10 | Hoxd10 | Lumbar / Sacral Vertebrae |

| PG11 | Hoxa11 | Hoxb11 | Hoxc11 | Hoxd11 | Sacral Vertebrae / Limb Patterning |

| PG12 | Hoxa13 | - | - | Hoxd12 | Caudal Vertebrae / Limb Patterning |

| PG13 | - | - | Hoxc13 | Hoxd13 | Caudal Vertebrae / Limb Patterning |

The posterior Hox genes (paralog groups 9-13) in the HoxA and HoxD clusters are particularly critical for limb development. Their nested and collinear expression domains in the mesenchymal cells of developing limbs are essential for specifying the proximal-distal axis and determining the identity of limb segments [5] [4]. The functional redundancy between paralogs, as evidenced by the more severe phenotypes in compound mutants compared to single mutants, necessitates sophisticated genetic strategies for complete functional analysis [5] [4].

Hox Genes in Limb Development: A Primer for Mutant Analysis

The developing limb has served as a premier model system for understanding how Hox genes pattern complex vertebrate structures. In mice, the forelimbs and hindlimbs are primarily patterned by the coordinated activity of genes from the HoxA and HoxD clusters [5] [4].

Functional Roles of HoxA and HoxD Clusters in the Limb

Genetic studies in mice have revealed that posterior paralog groups in the HoxA and HoxD clusters (approximately PG9-13) function cooperatively to pattern different segments of the limb [4]:

- Proximal Stylopod (e.g., Humerus): Requires the function of Hoxa9, Hoxd9, and other early-expressed paralogs [4].

- Middle Zeugopod (e.g., Radius/Ulna): Involves Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 genes, with compound mutants showing dramatic losses of these elements [4].

- Distal Autopod (e.g., Hand/Foot): Critically dependent on Hoxa13 and Hoxd12/d13 function, with simultaneous deletion leading to severe truncation of distal limb elements [5] [4].

The fundamental requirement for HoxA and HoxD function in limb development is conserved across vertebrates, as demonstrated by similar pectoral fin defects in zebrafish mutants lacking the homologous hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters [5]. This functional conservation underscores the utility of mouse models for understanding the core genetic programs governing paired appendage development.

Logical Framework for Hox Gene Function in Limb Patterning

The following diagram illustrates the cooperative relationship between HoxA and HoxD clusters in establishing limb pattern, and the experimental approach to dissecting their function through compound mutagenesis.

Diagram 1: Hox gene logic in limb patterning and mutant analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Generating Hox Compound Mutant Mice

Strategic Approach to Compound Mutagenesis

Due to the extensive functional redundancy among Hox paralogs, elucidating their full function requires the generation of compound mutants that remove multiple genes simultaneously. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for creating and analyzing such mutants, with emphasis on limb phenotype analysis.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Compound Mutant Generation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted gene editing using sgRNAs specific to Hox genes | Enables simultaneous targeting of multiple paralogs or entire cluster deletions [5] |

| Embryonic Stem (ES) Cells | Generation of targeted mutant alleles through homologous recombination | Traditional method for precise genetic modifications in mice [4] |

| tbx5a, shha RNA Probes | In situ hybridization to analyze early limb bud patterning | Critical for assessing molecular defects prior to morphological changes [5] [6] |

| Alcian Blue & Alizarin Red | Cartilage and bone staining for skeletal phenotype analysis | Standard technique for visualizing skeletal defects in late-stage embryos or neonates [5] |

| Micro-CT Imaging | High-resolution 3D skeletal analysis of adult mutants | Enables detailed quantification of bone defects in surviving adults [5] |

Protocol: Generation and Validation of HoxA/HoxD Compound Mutants

Phase 1: Genetic Targeting Strategy

Target Selection: Prioritize paralog groups with known overlapping expression domains. For limb studies, focus on PG9-13 in HoxA and HoxD clusters [4]. Design targeting vectors or sgRNAs for:

- Single paralog knockouts (e.g., Hoxa13⁻/⁻)

- Compound paralog knockouts (e.g., Hoxa13⁻/⁻; Hoxd13⁻/⁻)

- Cluster deletion mutants (e.g., HoxA cluster deletion) [5]

Mutant Generation:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Approach: Inject zygotes with pools of sgRNAs targeting multiple Hox genes and Cas9 mRNA/protein. This method is efficient for generating multi-gene knockouts and cluster deletions in a single step [5].

- ES Cell Approach: Use sequential targeting or Cre-loxP systems in ES cells to generate multi-allelic mutants, followed by blastocyst injection and germline transmission [4].

Phase 2: Phenotypic Analysis of Mutants

Embryonic Staging: Collect embryos at key developmental timepoints (e.g., E10.5 for early bud, E12.5 for patterning, E15.5 for chondrogenesis).

Molecular Characterization:

Morphological and Skeletal Analysis:

- Document external limb morphology at each stage.

- For late embryos (E14.5-E18.5) and neonates, perform cartilage and bone staining with Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red to visualize the skeletal pattern [5].

- For viable adult mutants, use micro-CT scanning to perform quantitative analysis of skeletal elements in three dimensions [5].

Phase 3: Data Interpretation

Compare phenotypic severity across genetic combinations, noting that:

- Single mutants often show mild or specific defects [4].

- Compound paralog mutants show enhanced phenotypes (e.g., Hoxa11/Hoxd11 double mutants show complete loss of radius and ulna) [4].

- Simultaneous deletion of entire HoxA and HoxD clusters results in the most severe limb truncations, particularly of distal elements [5] [4].

Correlate molecular and morphological data to determine when and where patterning is disrupted.

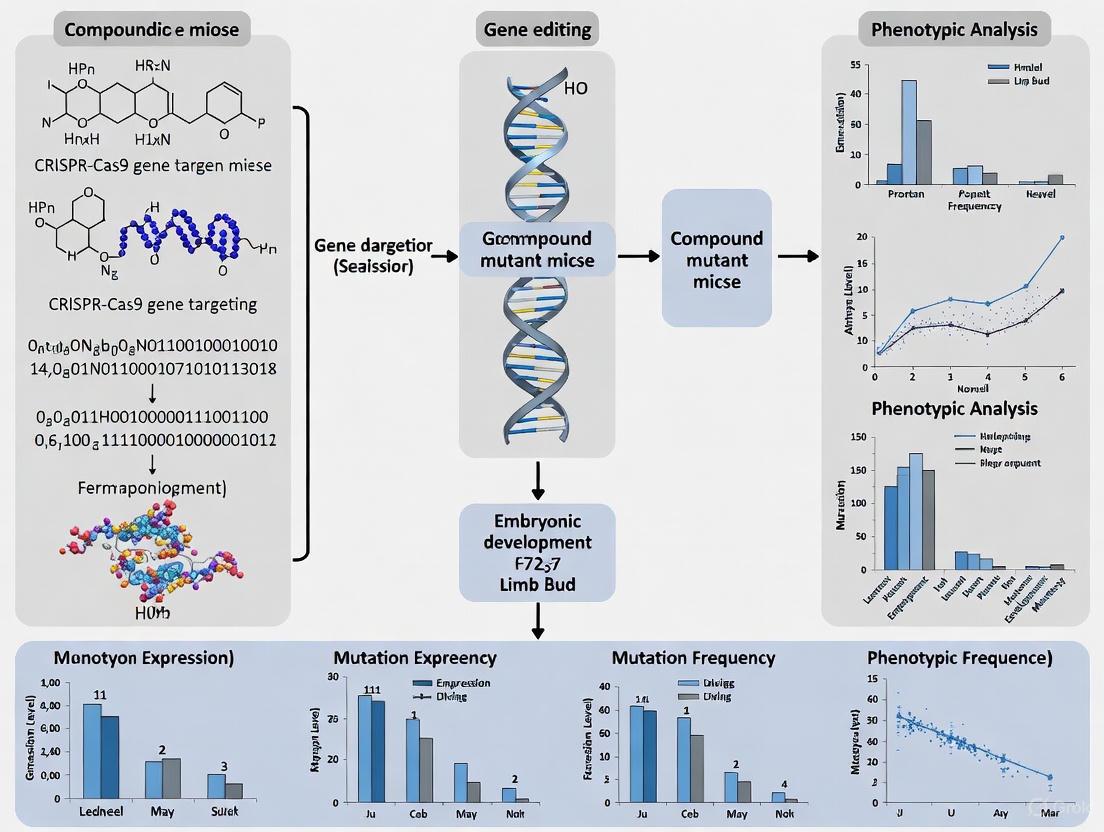

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key experimental steps in generating and analyzing Hox compound mutants.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Hox compound mutant analysis.

Application Notes and Technical Considerations

Addressing Functional Redundancy and Compensation

The high degree of functional redundancy among Hox paralogs presents a significant challenge for phenotypic analysis. Several strategies can help address this:

Systematic Compound Mutant Analysis: Generate mutants with increasing genetic complexity (single → double → cluster mutants) to reveal the full spectrum of gene function [5] [4].

Early Phenotype Analysis: Examine embryos at multiple developmental stages, as functional compensation might mask phenotypes at later stages. Early patterning defects are often more informative than final morphological outcomes.

Molecular Marker Analysis: Use in situ hybridization to assess the expression of downstream targets and signaling pathway components (e.g., shha in the ZPA) to identify subtle molecular changes before morphological defects become apparent [5].

Alternative Model Systems for Hox Gene Analysis

While mouse models are invaluable for understanding Hox function in mammalian development, complementary approaches in other organisms can provide additional insights:

Zebrafish: Offer advantages for live imaging and large-scale genetic screening. Zebrafish possess seven hox clusters due to teleost-specific genome duplication, providing a different perspective on subfunctionalization after duplication [5] [6].

Cross-Species Comparisons: Studies in organisms with different Hox cluster organizations (e.g., duplicated clusters in land snails [7]) can reveal general principles of Hox gene evolution and functional diversification after genome duplication.

The systematic analysis of Hox gene function in mice requires a comprehensive approach that addresses their complex genomic organization, overlapping expression patterns, and extensive functional redundancy. The protocols and frameworks presented here provide a roadmap for researchers to design effective strategies for generating and analyzing Hox compound mutants, with particular emphasis on limb development. As genetic technologies continue to advance, particularly with the precision and scalability of CRISPR-Cas9 systems, our ability to dissect the intricate functions of this essential gene family will continue to grow, offering new insights into the genetic control of morphological patterning in development and evolution.

The formation of a functionally integrated limb requires precise spatial coordination along three principal axes: the anteroposterior (AP) axis (thumb to little finger), the proximodistal (PD) axis (shoulder to fingertip), and the dorsoventral (DV) axis (knuckle to palm) [8]. This complex patterning process is governed by an evolutionarily conserved genetic toolkit that includes transcription factors and signaling molecules. Among these, Hox genes—a family of 39 homeobox-containing transcription factors arranged in four clusters (HOXA, HOXB, HOXC, HOXD) in mice and humans—play fundamental roles in establishing axial identity and morphology [8]. These genes encode transcription factors that bind DNA through a conserved 180 bp homeobox region, enabling them to activate or repress downstream genetic cascades that ultimately define specific anatomical regions [8]. The molecular basis of positional memory, wherein cells retain spatial identity from embryogenesis into adulthood, has been recently illuminated through studies revealing sustained expression of developmental transcription factors in specific domains [9]. This application note details methodologies for investigating Hox gene functions in limb axial patterning, with particular emphasis on generating and analyzing compound Hox mutant mice.

Hox Gene Expression and Function Across Limb Axes

Molecular Regulation of Axial Patterning

Table 1: Key Gene Families Regulating Limb Axial Patterning

| Gene Family | Examples | Primary Role in Limb Patterning | Axis Involvement | Mutant Phenotype/Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hox Genes | Hoxa/d cluster genes | Specify positional identity along axes; regulate proximal-distal segmentation | All three axes (Primary: PD, AP) | Hand-foot-genital syndrome, Synpolydactyly [8] |

| T-box Genes | Tbx5, Tbx4 | Determine limb identity (forelimb vs hindlimb); initiate outgrowth | PD | Holt-Oram syndrome (TBX5) [8] |

| Fibroblast Growth Factors | Fgf4, Fgf8, Fgf10 | Promote outgrowth; maintain AER function | PD | Achondroplasia (FGF receptor mutations) [8] |

| Hedgehog Signaling | Sonic hedgehog (Shh) | Establish anteroposterior polarity; digit specification | AP | Ectopic activity causes digit duplications [8] |

| Bone Morphogenic Proteins | BMP2, BMP7 | Chondrocyte condensation; joint formation; digit apoptosis | PD, AP | Hunter-Thompson and Grebe chondrodysplasias [8] |

| WNT Signaling | Wnt7a | Establish dorsoventral polarity; maintain Shh expression | DV, AP | - |

| Iroquois Homeobox | Irx genes | Cell specification in multiple tissues; regulated by Hox proteins | Context-dependent | Congenital conditions affecting multiple organs [10] |

Hoid Gene Expression Dynamics and Functional Domains

Table 2: Hox Gene Expression Patterns and Functional Contributions to Limb Axes

| Hox Gene Cluster | Chromosomal Location | Expression Domain in Limb Bud | Primary Axial Role | Genetic Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOXA | Chromosome 7 | Early proximal limb bud; later autopod | Proximal-distal patterning | Targeted mutations affect stylopod/zeugopod formation [8] |

| HOXB | Chromosome 17 | Limited role in limb patterning | Minor role in PD patterning | - |

| HOXC | Chromosome 12 | Limited role in limb patterning | Minor role in PD patterning | - |

| HOXD | Chromosome 2 | Complex 5' to 3' expression in autopod | Anteroposterior digit patterning | Compound mutants show digit reduction/polydactyly [8] |

| HOX10 (A/D) | Multiple clusters | Proximal limb bud (stylopod) | Proximal identity specification | Compound mutants show homeotic transformations [8] |

| HOX11 (A/D) | Multiple clusters | Middle limb bud (zeugopod) | Middle limb identity | Compound mutants show zeugopod defects [8] |

| HOX12 (A/D) | Multiple clusters | Distal limb bud (autopod) | Distal limb and digit identity | Compound mutants show autopod defects [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Hox Compound Mutant Analysis

Protocol 1: Generating Hox Compound Mutant Mice

Objective: To create mouse models with combined deficiencies in multiple Hox genes to investigate functional redundancy and axial patterning defects.

Materials:

- Hox floxed allele mouse strains (e.g., Hoxa11flox/flox, Hoxd11flox/flox)

- Tissue-specific Cre recombinase mice (Prrx1-Cre for limb mesenchyme)

- Tamoxifen (for inducible Cre systems)

- Genotyping primers for Hox alleles and Cre transgene

- Embryo dissection tools and stereomicroscope

Methodology:

- Crossing Strategy:

- Breed Hoxa11flox/flox;Hoxd11flox/flox double homozygous mice with Prrx1-Cre transgenic mice.

- Generate Hoxa11flox/+;Hoxd11flox/+;Prrx1-Cre+ triple heterozygous intermediates.

- Intercross triple heterozygotes to obtain compound mutants (Hoxa11flox/flox;Hoxd11flox/flox;Prrx1-Cre+).

- For temporal control, use Cre-ERT2 systems with tamoxifen administration (100μL of 10mg/mL tamoxifen in corn oil) at E9.5-E11.5.

Genotyping Protocol:

- Extract genomic DNA from tail or yolk sac biopsies using standard phenol-chloroform method.

- Perform PCR with allele-specific primers:

- Hoxa11 floxed allele: Forward 5'-CTGGACTCCATCGCTTACAC-3', Reverse 5'-GTAGCCATGGTGGAGAACCT-3' (wild-type: 280bp, floxed: 340bp)

- Hoxd11 floxed allele: Forward 5'-GATCCACAGGCATTCCTTCT-3', Reverse 5'-CACGGTCTTGGCTATGGTTC-3' (wild-type: 320bp, floxed: 390bp)

- Cre transgene: Forward 5'-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC-3', Reverse 5'-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3' (450bp product)

Embryo Harvesting:

- Time pregnancies accurately; designate noon of vaginal plug day as E0.5.

- Harvest embryos at critical limb patterning stages (E10.5-E15.5).

- Process for skeletal staining, in situ hybridization, or immunohistochemistry.

Protocol 2: Molecular Analysis of Positional Identity and Signaling Centers

Objective: To characterize molecular changes in Hox compound mutants using contemporary approaches for assessing positional memory and signaling pathways.

Materials:

- Hand2:EGFP knock-in axolotl or mouse model (for posterior identity tracking) [9]

- ZRS>TFP transgenic reporter (for Shh expression visualization) [9]

- RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent V2 Assay kit

- Antibodies: anti-HOXD13, anti-SHH, anti-FGF8, anti-HAND2

- Flow cytometry equipment for progenitor cell isolation

Methodology:

- Lineage Tracing of Signaling Centers:

- Utilize ZRS>TFP; loxP-mCherry double transgenic animals for fate mapping of Shh-expressing cells [9].

- Administer 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) at stage 42 (axolotl) or E10.5 (mouse) to label embryonic Shh lineage.

- Amputate limbs at mid-stylopod level and monitor regeneration/development.

- Image TFP (active Shh expression) and mCherry (historical Shh expression) at 7, 14, and 21 days post-amputation (d.p.a.) or equivalent developmental stages.

Transcriptional Profiling of Anterior-Posterior Compartments:

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of Prrx1+ connective tissue cells from anterior vs. posterior limb regions at E12.5.

- Extract RNA and perform RNA-seq library preparation using SMART-Seq v4 protocol.

- Conduct differential expression analysis (DESeq2, α<0.01) to identify anterior-posterior stratified genes [9].

- Validate key findings (e.g., Hand2, Alx1, Hoxd13) by in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry.

Functional Assessment of Positional Memory:

- Test positional memory stability by challenging anterior cells with ectopic Shh signaling.

- Apply recombinant Shh protein (1μg/mL) or SAG (Smoothened agonist, 200nM) to anterior limb explants for 48 hours.

- Assess establishment of ectopic Hand2-Shh feedback loop through qPCR and reporter expression [9].

- Perform secondary amputation to test lasting competence for Shh expression.

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Networks in Limb Patterning

Genetic Regulation of Limb Axes

Figure 1: Genetic regulation of proximal-distal limb patterning

Anteroposterior Patterning Network

Figure 2: Molecular network controlling anteroposterior limb patterning

Dorsoventral Patterning Circuit

Figure 3: Signaling pathways establishing dorsoventral limb asymmetry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Limb Patterning Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage Tracing Systems | ZRS>TFP; loxP-mCherry [9] | Fate mapping of Shh-expressing cells | Determine embryonic vs. regeneration-derived Shh lineage |

| Knock-in Reporters | Hand2:EGFP [9] | Visualize posterior identity cells | Track Hand2 expression dynamics in development/regeneration |

| Conditional Mutagenesis | Prrx1-Cre; Hox floxed alleles | Limb mesenchyme-specific gene deletion | Generate tissue-specific Hox compound mutants |

| Signaling Agonists/Antagonists | Recombinant Shh; SAG; Cyclopamine | Activate/inhibit Shh signaling | Test signaling pathway requirements in axial patterning |

| Transcriptional Profiling | RNAscope; Single-cell RNAseq | Spatial transcriptomics; cell type identification | Characterize anterior-posterior gene expression differences |

| Positional Memory Assays | Ectopic Shh exposure; blastema formation | Test stability of positional identity | Convert anterior to posterior fate [9] |

| Axolotl Models | Ambystoma mexicanum transgenic lines | Study regeneration-specific mechanisms | Investigate positional memory in regenerative contexts [9] |

Concluding Remarks and Applications

The molecular dissection of Hox gene functions in limb axial patterning reveals remarkable conservation of genetic programs across vertebrate species, alongside species-specific adaptations. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of positional memory—particularly the identification of the Hand2-Shh positive-feedback loop that maintains posterior identity—provide new insights into how cells retain and execute positional information during development and regeneration [9]. The experimental approaches outlined here enable systematic investigation of how Hox genes orchestrate the complex three-dimensional patterning of the vertebrate limb. These methodologies are particularly valuable for drug development professionals investigating congenital limb malformations and for tissue engineering applications aiming to recapitulate native patterning in regenerated tissues. The continued refinement of compound mutant strategies will further elucidate the functional redundancies and specificities within the Hox gene network that coordinates limb morphogenesis.

Application Note: Quantifying Phenotypic Enhancement in Compound Mutants

Functional redundancy among Hox genes is a well-established concept, yet its full extent and mechanistic basis are often only revealed through the generation and analysis of compound mutants. This application note synthesizes key quantitative findings from studies comparing single and compound Hox mutants, providing researchers with a consolidated reference for experimental planning and phenotypic expectation.

Table 1: Comparative Phenotypic Severity in Limb/Appendage Development Models

| Organism / Model | Genetic Manipulation | Single Mutant Phenotype | Compound Mutant Phenotype | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (Limb) [11] | Hoxd12 point mutation | Not reported | Microdactyly | Shortened digits I & V (approx. 50% of WT length); misshapen, thinner radius/ulna [11]. |

| Zebrafish (Pectoral Fin) [5] | hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- | hoxab-/-: Shortened fin [5] | Severe shortening of endoskeletal disc and fin-fold | hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- showed most severe shortening among double mutants; triple mutants most severe overall [5]. |

| Zebrafish (Pectoral Fin Bud Initiation) [6] | hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- | hoxba-/-: Reduced tbx5a expression, fin abnormalities [6] | Complete absence of pectoral fins | 5.9% penetrance (15/252 embryos) of fin absence, matching Mendelian expectation for double homozygotes [6]. |

| Mouse (Uterine Gland Formation) [12] | Hoxa9,10,11+/−; Hoxc9,10,11+/−; Hoxd9,10,11+/− (ACD+/−) | Hoxa10-/- or Hoxa11-/-: Subfertility [12] | Drastic fertility reduction | ~0.15 pups/vaginal plug (vs. ~5.3 in AD+/- and ~11.5 in WT) [12]. |

| Mouse (Hematopoiesis) [13] | Hoxa9-/-; Hoxb3-/-; Hoxb4-/- | Hoxa9-/-: Reconstitution defect [13] | Reduced body weight, marked reduction in spleen size and cellularity | Increased immunophenotypic HSC numbers (Lin−, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CD150+) but reconstitution defect no worse than Hoxa9-/- single mutant [13]. |

Protocol: Generating and Analyzing Hox Compound Mutants for Limb Research

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for creating and validating compound Hox mutant mice, with a specific focus on the analysis of limb phenotypes. It integrates best practices from multiple studies to ensure robust and interpretable results.

Stage 1: Genetic Model Design and Mutant Generation

Materials:

- Mouse Lines: Single mutant alleles (e.g., Hoxd12 point mutant [11], Hoxa9,10,11 cluster mutant [12]).

- Genotyping Reagents: PCR primers flanking the mutation site, appropriate DNA polymerases, gel electrophoresis equipment.

- CRISPR-Cas9 System: (Optional, for cluster deletion) Cas9 protein/gRNA, microinjection apparatus for zygotes [5] [6].

Procedure:

- Select Paralogous Targets: Identify candidate Hox genes for compound mutation based on sequence similarity (e.g., paralog groups 9-13), overlapping expression domains in the limb bud, and mild or absent single-mutant phenotypes [12] [5].

- Design Breeding Scheme: Develop a multi-generation crossing strategy to combine multiple mutant alleles. For example, to generate a triple cluster heterozygous mutant (ACD+/−), cross single cluster mutants over several generations [12].

- Critical: Maintain careful genotypic records at each generation. Backcross to a standard background strain (e.g., C57BL/6) to minimize confounding effects of genetic background.

- Generate Mutant Alleles (if not available): For cluster-wide deletions, use CRISPR-Cas9. Design multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting flanking regions of the cluster to induce a large genomic deletion. Validate deletions via long-range PCR and sequencing [5] [6].

Stage 2: Phenotypic Characterization of Limb Defects

Materials:

- Fixation and Staining: Alcian Blue (for cartilage), Alizarin Red S (for bone), ethanol, acetic acid, potassium hydroxide [11].

- Imaging: Stereomicroscope with camera, micro-CT scanner (for high-resolution 3D adult bone structure) [5].

- RNA In Situ Hybridization: DIG-labeled RNA probes (e.g., for Shh, Tbx5), hybridization buffer, anti-DIG antibody, NBT/BCIP substrate [5] [6].

Procedure:

- Skeletal Preparation and Morphometry:

- Euthanize mice at desired stage (e.g., P0 for neonates, 8 weeks for adults) [11].

- Skin and eviscerate specimens, then fix in 95% ethanol.

- Stain with Alcian Blue solution to visualize cartilage, followed by Alizarin Red S solution to stain bone.

- Clear soft tissues in 1% KOH and store in glycerol.

- Image stained skeletons and perform quantitative morphometry: measure lengths of zeugopod elements (radius/ulna, tibia/fibula) and all phalanges using image analysis software. Compare to wild-type and single mutant littermates [11].

- Molecular Phenotyping via Gene Expression Analysis:

- Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH): To assess patterning gene expression (e.g., Shh) in embryos or limb buds.

- Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR): To quantify expression changes of downstream targets.

Stage 3: Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Compare Phenotypic Severity: Systematically compare the compound mutant phenotype to single mutants and wild-types using the quantitative data from Stage 2.

- Assess Synergy/Additivity: Determine if the phenotype in the compound mutant is merely the sum of single mutant effects (additive) or is more severe than expected (synergistic), indicating functional redundancy [12] [5].

- Correlate Molecular and Morphological Defects: Link misregulation of key signaling pathways (e.g., Shh downregulation) to the specific morphological abnormalities observed (e.g., truncated digits) [5].

Signaling Pathways in Hox-Mediated Limb Patterming

Hox genes exert their influence on limb development through the regulation of key signaling pathways. The following diagram synthesizes findings from multiple mutant studies to illustrate this regulatory network.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Hox Compound Mutant Studies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application in Hox Studies | Example Usage in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster-Deletion Mutants | To overcome functional redundancy by deleting multiple Hox genes simultaneously. | Zebrafish hoxaa/hoxab/hoxda triple mutants reveal severe fin truncation, mild in single mutants [5]. |

| Sensitized Genetic Background | A partially compromised background (e.g., heterozygosity) to reveal functions of redundant genes. | Hoxa9,10,11+/- background uncovered essential fertility role for Hoxd9,10,11 genes [12]. |

| Alcian Blue & Alizarin Red S | Differential staining of cartilage (blue) and bone (red) in skeletal preparations. | Used to quantify bone shortening in Hoxd12 point mutant mouse limbs [11]. |

| Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) | Spatial visualization of gene expression patterns in entire embryos or tissues. | Identified downregulation of shha in pectoral fin buds of zebrafish Hox cluster mutants [5]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | High-resolution profiling of gene expression in individual cells from a complex tissue. | Defined altered gene expression patterns in all cell types of Hox mutant mouse uteri [12]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | For generating targeted deletions of specific Hox genes or entire genomic clusters. | Used to create deletion mutants for all seven zebrafish hox clusters [5] [6]. |

The Hox gene family comprises 39 highly conserved transcription factors in mammals, organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) on different chromosomes. These genes are master regulators of positional identity along the anterior-posterior body axis and play particularly crucial roles in vertebrate limb development [14] [15]. The nested, overlapping expression domains of Hox genes generate a combinatorial "Hox code" that provides specific patterning information for different limb segments [15]. In the developing limb, posterior Hox genes from the HoxA and HoxD clusters (specifically Hox9-13 paralogs) are critical for patterning the three main limb segments: the proximal stylopod (humerus/femur), medial zeugopod (radius-ulna/tibia-fibula), and distal autopod (hand/foot bones) [14]. The unique property of collinearity—where the order of Hox genes on the chromosome corresponds to their spatial and temporal expression domains—ensures precise regulation of limb patterning along the proximodistal axis [16].

Upstream Regulators of Hox Gene Expression in the Limb

Hox gene expression in the developing limb is regulated by complex integration of signaling gradients and transcriptional mechanisms. Retinoic acid (RA), Fibroblast growth factors (Fgfs), and Wingless-related integration sites (WNTs) form opposing signaling gradients that establish the nested Hox expression patterns [16]. These upstream regulators act through specific cis-regulatory elements, including retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) embedded within and adjacent to Hox clusters [16].

Table 1: Key Upstream Regulators of Hox Genes in Limb Development

| Regulator | Role in Hox Regulation | Specific Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Anterior-posterior patterning | Binds to RAREs; direct transcriptional regulation of multiple Hox genes [16] |

| FGF Signaling | Proximodistal outgrowth | Works with BMP signaling; regulates Hoxd gene expression [17] |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Limb bud initiation | Activates Hox gene expression through TCF/LEF binding sites [18] |

| Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) | Anterior-posterior patterning | Feedback loop with Hox genes; maintained by Hox9 and restricted by Hox5 [14] |

| BMP Signaling | Cartilage patterning | Works with FGF-4 to regulate HoxD gene expression [17] |

The regulatory landscape surrounding Hox clusters contains numerous enhancers that integrate these diverse signaling inputs. These enhancers can act locally on adjacent genes or over long distances to coordinately regulate multiple genes within a cluster [16]. For instance, in the mouse Hoxb complex, three RAREs in the middle of the cluster participate in mediating response to RA by regulating multiple coding and long non-coding RNAs [16].

Specific Upstream Regulatory Interactions

Recent research has revealed specific regulatory interactions governing Hox expression in limbs. Hox5 genes function to restrict Shh expression to the posterior limb bud by interacting with Plzf, thereby preventing anterior Shh expression that leads to patterning defects [14]. Conversely, Hox9 genes promote posterior Hand2 expression, which inhibits the hedgehog pathway inhibitor Gli3, allowing induction of Shh expression in the posterior limb bud [14]. This precise control of Shh positioning is critical for proper anterior-posterior limb patterning.

Downstream Targets of Hox Gene Regulation

Hox proteins execute their patterning functions by regulating diverse downstream target genes involved in skeletal formation, muscle development, and tendon specification. Genome-level identification of Hox targets in Drosophila revealed that Hox proteins regulate upstream regulators, cofactors, and signaling pathway components, creating complex regulatory loops [19].

Table 2: Key Downstream Targets of Hox Genes in Limb Development

| Target Gene | Function | Regulatory Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Shh | Anterior-posterior patterning | Positively regulated by Hoxd12; initiated by Hox9 genes [14] [11] |

| Fgf4 | Limb outgrowth | Dramatically increased in Hoxd12 point mutants [11] |

| Lmx1b | Dorsal-ventral patterning | Significantly upregulated in Hoxd12 point mutants [11] |

| Bmp4 | Proximal-distal patterning | Downstream of Wnt2/2b in lung development (Hox5 pathway) [18] |

| Distal-less (Dll) | Limb development | Directly repressed by BX-C Hox proteins in abdomen [20] |

| SIX2/GDNF | Nephron progenitor maintenance | Regulated by Hox11 genes in kidney development [21] |

Hox proteins exhibit remarkable versatility in target selection, often achieved through association with other transcription factors rather than specific DNA binding motifs. Research on Ultrabithorax (Ubx) in Drosophila revealed that while Ubx-bound sequences are conserved across insect genomes, no consensus Ubx-specific motif was detected [19]. Instead, binding motifs for other transcription factors like GAGA factor (GAF) and MAD were enriched, suggesting complex regulatory loops govern Hox function [19].

Experimental Protocols for Hox Compound Mutant Analysis

Protocol: Generating Hox Compound Mutant Mice

Principle: Due to extensive functional redundancy among Hox paralogs, compound mutants are necessary to reveal their full phenotypic contributions [15]. This protocol outlines the generation of mice with multiple Hox gene mutations using BAC recombineering technology.

Materials:

- BAC clones containing Hox clusters

- Embryonic stem cells (ESCs)

- Kan/Neo selectable marker flanked by Lox66 and Lox71 sequences

- Cre recombinase

- Quantitative PCR reagents for genotyping

Procedure:

- BAC Modification: Engineer a BAC targeting construct with frameshift mutations in multiple flanking Hox genes using recombineering technology [21].

- Marker Integration: Recombine a DNA segment with Kan/Neo selectable marker flanked by homology regions to the first exon of target Hox genes.

- Marker Excision: Following identification of correctly modified E. coli, remove the selectable marker with inducible Cre recombinase.

- ESC Targeting: Electroporate the final BAC targeting construct into ESCs and screen by genomic DNA qPCR to identify clones with correct targeting.

- Mouse Generation: Generate chimeric mice from targeted ESC clones and breed to germline transmission.

- Neo Excision: Cross resulting mice with germline Cre expressors to remove remaining Kan/Neo sequence.

Technical Notes: This strategy allows targeting frameshift mutations in multiple flanking Hox genes while leaving intergenic and intronic shared enhancers intact, avoiding ectopic expression of remaining Hox genes that can confound interpretation [21].

Protocol: Skeletal Phenotype Analysis of Hox Mutants

Principle: Hox mutations frequently cause homeotic transformations detectable through skeletal staining techniques.

Materials:

- Alcian Blue solution (cartilage staining)

- Alizarin Red solution (bone staining)

- Ethanol series

- Potassium hydroxide

- Glycerol

Procedure:

- Fixation: Fix E18.5 or newborn pups in 95% ethanol.

- Cartilage Staining: Stain with Alcian Blue solution to visualize cartilage.

- Bone Staining: Counterstain with Alizarin Red to visualize mineralized bone.

- Clearing: Clear soft tissue in potassium hydroxide solution.

- Storage: Transfer through glycerol series for preservation and imaging.

Analysis: Examine skeletal elements for homeotic transformations, such as rib attachments on lumbar vertebrae or changes in digit number and identity [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Limb Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Limb Development Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Anti-Ubx (N-terminal specific) [19] | ChIP experiments to identify direct Hox targets |

| Mouse Models | Hoxa5;Hoxb5;Hoxc5 triple mutants [18] | Revealing redundant functions in lung development |

| Hoxd12 point mutants [11] | Studying specific amino acid requirements | |

| Hox9,10,11 multi-cluster mutants [21] | Assessing functional redundancy across paralog groups | |

| Staining Reagents | Alcian Blue [11] | Cartilage visualization in skeletal preparations |

| Alizarin Red [11] | Bone mineralization staining | |

| Molecular Biology Tools | ChIP-chip platforms [19] | Genome-wide identification of Hox binding sites |

| Quantitative RT-PCR [11] | Measuring expression changes in downstream targets | |

| BAC Libraries | Hox cluster BACs [21] | Generating targeted mutations via recombineering |

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Networks

The following diagram illustrates the key regulatory interactions between upstream regulators, Hox genes, and downstream targets in limb development:

Positioning Hox genes within limb development networks reveals their crucial role as integrators of positional information and executors of morphological patterning. The extensive functional redundancy among Hox paralogs necessitates compound mutant approaches to fully elucidate their functions [15]. The experimental protocols and reagents outlined here provide a framework for systematic analysis of Hox gene function in limb development. Future research directions include better understanding how Hox proteins select their specific targets despite similar DNA binding preferences, and how the dynamic transcriptional regulation of Hox clusters responds to signaling gradients to generate precise morphological outcomes [16] [19]. These insights have broader implications for understanding congenital limb malformations and evolutionary adaptations in limb morphology across species.

Historical Context and Key Milestones in Hox Limb Research

Hox genes, encoding a family of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, are fundamental architects of the body plan in bilaterian organisms. Their role in specifying structures along the anteroposterior axis extends to the intricate process of limb development, where they orchestrate the formation of the stylopod (upper limb), zeugopod (forearm/lower leg), and autopod (hand/foot) [22] [23]. Research into Hox genes in limb development has progressively shifted from observing large-scale phenotypic transformations to deciphering the complex regulatory networks and cellular heterogeneities that underpin limb patterning. This application note frames these key milestones within the context of generating and analyzing Hox compound mutant mice, providing researchers with structured data, validated protocols, and visual guides to advance this critical field.

Key Milestones in Hox Limb Research

The following table summarizes pivotal findings and the evolution of methodologies in Hox limb research.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones and Findings in Hox Limb Research

| Milestone / Finding | Experimental Model | Key Outcome | Implication for Compound Mutants |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENU-Induced Point Mutation [11] | Mouse (Hoxd12 A-to-C) | Microdactyly; shortened digits, missing digit I tip; increased Fgf4 & Lmx1b. | Point mutants model specific functional alterations vs. full gene deletion. |

| Bimodal Regulatory Model [22] [23] | Mouse & Chick Limb Buds | Limb patterning via two chromatin domains (T-DOM for zeugopod, C-DOM for autopod). | Compound mutants may disrupt domain switching, affecting proximal vs. distal structures. |

| Functional Cooperation of Genes [24] | Mouse Single-Cell Transcriptomics | Heterogeneous combinatorial Hoxd gene expression in single cells of the autopod. | Phenotype severity depends on the number and combination of Hoxd genes deleted. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis [25] | Amphipod (Parhyale) | Precise limb transformations via targeted gene knockout and RNAi. | Enables efficient generation of complex, multi-gene knockout mice. |

| Positional Memory in Regeneration [9] | Axolotl Limb Regeneration | A positive-feedback loop (Hand2-Shh) maintains posterior positional memory. | Suggests Hox function extends beyond development to adult tissue patterning and repair. |

Quantitative Phenotypic Data in Hox Mutants

Quantitative assessment of skeletal elements is crucial for characterizing mutant phenotypes. The following table compiles representative data from a Hoxd12 point mutation study.

Table 2: Quantitative Skeletal Analysis of Hoxd12 Point Mutant Mice [11]

| Skeletal Element | Wild-Type Length (cm) | Microdactyly Mutant Length (cm) | Phenotypic Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digit V Metacarpal | 0.2 | 0.1 | 50% reduction in length |

| Digit V Medial Phalanx | 0.2 | 0.1 | 50% reduction in length |

| Radius & Ulna | 1.3 | 1.3 | Total length unchanged, but thinner and misshapen |

| Digit I | Normal | Missing tip | Loss of distal structure |

Experimental Protocols for Limb Analysis

Protocol 1: Skeletal Staining for Cartilage and Bone

This protocol is used to visualize and quantify the cartilage and bone skeleton in developing or adult mouse limbs, as applied in [11].

Materials:

- Alcian Blue 8GX ( stains sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage)

- Alizarin Red S ( stains calcium deposits in bone)

- Ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%)

- Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) solution

- Glycerol

- Research Reagent Solution: Alcian Blue-Alizarin Red Staining Solution

Method:

- Euthanize and Fix: Euthanize mice at the desired postnatal age (e.g., 8 weeks). Skin, viscera, and fat, then fix carcasses in 95% ethanol for 1-2 weeks.

- Cartilage Staining: Transfer specimens to Alcian Blue staining solution for 2-3 days.

- * Tissue Clearing:* Transfer specimens to 1% KOH solution until the skeleton is clearly visible.

- Bone Staining: Transfer specimens to Alizarin Red staining solution for 1-2 days.

- Clearing and Storage: Clear remaining tissue in a series of KOH-glycerol solutions (e.g., 1:4, 1:1, 4:1 KOH to glycerol) and store in 100% glycerol.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image specimens using a dissecting microscope. Measure bone lengths using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Protocol 2: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Limb Bud Cells

This protocol outlines the process for analyzing heterogeneous Hox gene expression at single-cell resolution, as performed in [24].

Materials:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS)

- Microfluidics platform for single-cell capture (e.g., Fluidigm C1)

- RNA-seq library preparation kit

- Research Reagent Solution: Hoxd11::GFP Reporter Mouse Line

Method:

- Dissociation: Microdissect autopod tissue from embryonic day (E) 12.5 mouse embryos and digest with collagenase to create a single-cell suspension.

- Cell Sorting (FACS): Sort cells using FACS. For enrichment of Hoxd-expressing cells, use limb buds from a Hoxd11::GFP reporter mouse line.

- Single-Cell Capture and Lysis: Load the cell suspension onto a microfluidics chip to capture individual cells. Lyse cells and reverse-transcribe RNA into cDNA.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplify cDNA and prepare sequencing libraries with unique barcodes for each cell. Sequence libraries on a high-throughput platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align sequences to the reference genome, quantify gene expression, and use clustering algorithms to identify cell populations based on their Hox gene combinatorial expression profiles.

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core regulatory principles governing Hox gene function in limb development.

Diagram 1: Bimodal Regulation of HoxD Cluster in Limb Patterning

Diagram 2: Hoxd12 Point Mutation Disrupts Gene Network

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Compound Mutant Limb Analysis

| Reagent / Model | Type | Key Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxd11::GFP Reporter Mouse [24] | Transgenic Model | Enables visualization of Hoxd11 expression domains and FACS enrichment of Hox-expressing cells. | Isolating specific cell populations for single-cell RNA-seq from limb buds. |

| Alcian Blue / Alizarin Red [11] | Histological Stain | Differentiates cartilage (blue) and mineralized bone (red) in whole-mount skeletons. | Quantitative analysis of skeletal elements in mutant vs. wild-type limbs. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System [25] | Gene Editing Tool | Allows for precise, simultaneous knockout of multiple Hox genes to create compound mutants. | Efficient generation of Hoxd9-d13 compound mutant mice to study functional overlap. |

| N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) [11] | Chemical Mutagen | Creates random point mutations for forward genetic screens to discover novel limb phenotypes. | Identifying novel alleles and subtle functional changes in Hox genes. |

Building Complex Mutants: From Single Knockouts to Comprehensive Paralog Deletion

The Hox gene family, comprising 39 evolutionarily conserved transcription factors in mammals, provides crucial positional information along the anterior-posterior body axis during embryonic development. These genes are organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) located on different chromosomes and are further classified into 13 paralog groups (PG1-13) based on sequence similarity and genomic position. In the context of limb development, Hox genes execute particularly critical functions in determining limb positioning, patterning skeletal elements, and specifying morphological identities between forelimbs and hindlimbs. The strategic selection of target Hox genes for functional analysis requires a comprehensive understanding of their distinct and overlapping roles during limb morphogenesis, informed by both historical data and recent single-cell transcriptomic atlases of human embryonic limb development [26].

The complex regulation of Hox genes occurs through a bimodal mechanism involving topologically associating domains (TADs) that coordinate their spatiotemporal expression. During limb development, genes primarily from the HoxA and HoxD clusters are sequentially activated through dynamic interactions with regulatory elements located in telomeric (T-DOM) and centromeric (C-DOM) domains. This regulatory switch enables the same genes to pattern different limb segments at various developmental timepoints, with early proximal patterning controlled through T-DOM and subsequent distal patterning mediated through C-DOM [27] [28]. For researchers generating compound mutant mice, understanding this sophisticated regulatory landscape is essential for designing targeted interventions that specifically perturb distinct aspects of limb patterning without completely disrupting limb initiation or outgrowth.

Strategic Selection of Target Hox Genes and Paralog Groups

Hox Genes Controlling Limb Positioning and Initiation

The initial positioning of limb buds along the anterior-posterior axis is regulated by specific Hox genes, with compelling genetic evidence now establishing that HoxB cluster genes are particularly critical for this process. Recent research in zebrafish has demonstrated that double-deletion mutants of hoxba and hoxbb clusters (derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster) exhibit a complete absence of pectoral fins, accompanied by failure to induce tbx5a expression in the pectoral fin field [6]. Further analysis identified hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as pivotal genes cooperatively determining pectoral fin positioning through establishing expression domains along the anteroposterior axis. Interestingly, while Hoxb5 knockout mice display only a rostral shift of forelimb buds with incomplete penetrance, the zebrafish studies provide the first genetic evidence that Hox genes definitively specify the positions of paired appendages in vertebrates [6].

In mammalian systems, the identity of limbs as forelimbs versus hindlimbs is determined by the rostrocaudal position of the lateral plate mesoderm where the limb bud forms, governed by an antagonistic gradient of rostral retinoic acid (RA) and caudal FGF signaling. The forelimb field specifically requires RA for expression of Tbx5, while the hindlimb field is determined by GDF11 signaling from the paraxial mesoderm, which activates hindlimb-specific genes including Isl1, Pitx1, and Tbx4 [29]. The GDF11/SMAD2 signaling pathway plays a particularly crucial role in activating posterior Hox genes (Hox10-13) to specify lumbar, sacral, and caudal vertebral identities, with recent research identifying Protogenin (Prtg) as a key regulator that facilitates this trunk-to-tail HOX code transition by enhancing GDF11 signaling activity [30].

Hox Genes Regulating Proximal-Distal Patterning of Limb Elements

The development of stylopod (upper arm/thigh), zeugopod (forearm/shank), and autopod (hand/foot) elements is coordinately regulated by Hox genes with specific paralog groups dominating different regions. Genetic studies across multiple vertebrate models have established that 5' HoxA and HoxD genes (paralog groups 9-13) play predominant roles in patterning the distal limb elements, while more 3' genes contribute to proximal patterning. A recent human embryonic limb cell atlas has spatially resolved the expression of HOXA and HOXD gene clusters across developing limbs, confirming conserved patterning roles while identifying novel human-specific features [26].

Table 1: Key Hox Genes and Their Roles in Limb Patterning

| Hox Gene | Paralog Group | Limb Domain | Major Function | Phenotype of Mutant Mice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxd12 | PG12 | Autopod (distal) | Digit patterning, chondrogenic branching | Microdactyly, shortened digits, missing digit I tip [11] |

| Hoxa13 | PG13 | Autopod (distal) | Digit formation, terminal differentiation | Digit hypoplasia, long bone shortening [28] |

| Hoxd13 | PG13 | Autopod (distal) | Digit patterning, joint specification | Brachydactyly, synpolydactyly [28] |

| Hoxa11 | PG11 | Zeugopod (mid) | Radius/ulna and tibia/fibula patterning | Zeugopod shortening, fused bones [28] |

| Hoxd11 | PG11 | Transition domain | Proximal-distal transition | Humerus/femur patterning defects [27] |

| Hoxd10 | PG10 | Stylopod (proximal) | Femur/humerus specification | Minor patterning defects [28] |

| Hoxb5 | PG5 | Limb positioning | Forelimb positioning initiation | Rostral shift of forelimb buds (incomplete penetrance) [6] |

| Hoxc10 | PG10 | Hindlimb identity | Hindlimb-specific patterning | Altered hindlimb morphology [29] |

Hox Genes Governing Anterior-Posterior Patterning and Digit Identity

The anterior-posterior polarity of the limb, crucial for establishing digit identities (thumb to pinky), is regulated through a complex interplay between Hox genes and Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling. Point mutations in Hoxd12 provide particularly insightful evidence of its role in digit patterning, as ENU-induced A-to-C mutation resulting in alanine-to-serine conversion produces microdactyly with specific shortening of digits, missing tip of digit I, and altered anterior-posterior patterning [11]. Notably, these Hoxd12 point mutants exhibit dramatic increases in Fgf4 and Lmx1b expression while maintaining normal Shh expression, suggesting Hoxd12 functions independently of or downstream to the SHH pathway in digit patterning.

Comparative analyses between chick and mouse limb development reveal important species-specific differences in HoxD gene regulation that correlate with morphological variations. While the bimodal regulatory mechanism (switching between T-DOM and C-DOM) is globally conserved, modifications in enhancer activities, TAD boundary widths, and forelimb versus hindlimb regulatory controls have evolved between these species [28]. These differences manifest in the striking morphological specialization of chick wings versus legs, highlighting how alterations in Hox gene regulation—rather than simply their expression—contribute to species-specific limb morphologies.

Experimental Approaches for Hox Gene Analysis in Limb Development

Protocol 1: ENU Mutagenesis Screening for Limb Phenotypes

Objective: To identify novel point mutations in Hox genes that cause specific limb malformations without complete loss of gene function.

Materials and Methods:

- Animals: BALB/cJ male mice (8-10 weeks old) for ENU treatment

- Mutagen: N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) dissolved in citrate buffer (pH 5.0)

- Dosing: Intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ENU, repeated after 2-week interval

- Breeding Scheme: Three-generation breeding protocol to establish recessive mutations

- Phenotypic Screening: Examination of F3 progeny for limb abnormalities at birth

Procedure:

- Prepare fresh ENU solution at 10 mg/mL in citrate buffer (pH 5.0)

- Administer ENU to male mice via intraperitoneal injection at 100 mg/kg body weight

- After two-week recovery, administer second dose of ENU at same concentration

- Cross ENU-treated males with wild-type females to produce F1 generation

- Intercross F1 siblings to generate F2 population

- Cross F2 animals to produce F3 progeny for phenotypic screening

- Identify mutants with specific microdactyly phenotypes at birth

- Perform skeletal staining with Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red at 8 weeks to visualize bone and cartilage patterns

Genetic Mapping and Mutation Identification:

- Outcross mutant mice to C57BL/6 strain to generate mapping population

- Use microsatellite markers (e.g., D2Mit329, D2Mit285) for initial linkage analysis

- Sequence candidate genes in linked chromosomal regions

- Confirm causative mutations by genotyping and phenotypic correlation

This approach successfully identified an A-to-C point mutation in Hoxd12 causing alanine-to-serine conversion and specific microdactyly with anterior-posterior patterning defects [11].

Protocol 2: Skeletal Staining and Morphometric Analysis of Limb Elements

Objective: To quantitatively assess skeletal patterning defects in Hox mutant mice.

Materials:

- Alcian Blue 8GX (cartilage stain)

- Alizarin Red S (bone stain)

- Ethanol series (70%, 95%, 100%)

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH) for tissue clearing

- Glycerol for storage and visualization

Procedure:

- Euthanize mice at postnatal day 56 (8 weeks) for complete ossification

- Skin and eviscerate specimens, then fix in 95% ethanol for 48 hours

- Transfer to 100% acetone for 48 hours to remove fat

- Stain with Alcian Blue solution (0.015% in 80% ethanol/20% acetic acid) for 48 hours

- Rinse in 95% ethanol, then clear in 1% KOH until skeleton visible

- Stain with Alizarin Red solution (0.005% in 1% KOH) for 48 hours

- Clear through graded glycerol/KOH solutions (20%, 50%, 80% glycerol)

- Store in 100% glycerol for long-term preservation

Morphometric Measurements:

- Measure lengths of individual skeletal elements using digital calipers

- Record lengths of metacarpals, phalanges, radius, and ulna

- Compare mutant versus wild-type measurements using Student's t-test

- Document missing or fused elements, and alterations in joint morphology

This protocol enabled quantification of microdactyly in Hoxd12 point mutants, revealing specific shortening of digit V phalanges to half their normal length and missing tip of digit I [11].

Protocol 3: Spatial Transcriptomic Mapping of Hox Expression in Limb Buds

Objective: To resolve Hox gene expression patterns with single-cell resolution and spatial context in developing limbs.

Materials:

- Fresh human embryonic limb tissue (PCW5-PCW9)

- Single-cell RNA sequencing platform (10x Genomics)

- Spatial transcriptomics reagents (Visium assay, 10x Genomics)

- Tissue clearing reagents for 3D imaging

- Computational tools for data integration (VisiumStitcher)

Procedure:

- Dissect human embryonic hindlimb tissues at PCW5, PCW6, PCW7, PCW8, and PCW9

- Prepare single-cell suspensions using gentle enzymatic digestion

- Perform scRNA-seq library preparation using 10x Genomics platform

- Process spatial transcriptomic samples using Visium spatial gene expression protocol

- For whole-limb spatial mapping, place multiple anatomically continuous sections on same Visium chip

- Integrate data using VisiumStitcher to reconstruct sagittal section of entire fetal hindlimb

- Identify distinct mesenchymal populations based on marker gene expression:

- Distal mesenchyme (LHX2+MSX1+SP9+)

- RDH10+ distal mesenchyme (RDH10+LHX2+MSX1+)

- Transitional mesenchyme (IRX1+MSX1+)

Data Analysis:

- Map HOXA and HOXD cluster gene expression patterns across proximal-distal axis

- Correlate expression boundaries with anatomical landmarks

- Identify novel cell populations based on transcriptional signatures

- Compare human patterns with mouse embryonic limb scRNA-seq data

This approach has revealed extensive diversification of cells from multipotent progenitors to differentiated states and mapped distinct mesenchymal populations in the autopod with specific spatial distributions [26].

Regulatory Networks and Signaling Pathways in Hox-Mediated Limb Patterning

The regulation of Hox gene expression during limb development involves sophisticated signaling pathways and epigenetic mechanisms that ensure precise spatiotemporal control. The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory network controlling Hox gene expression during limb development:

Diagram 1: Regulatory network of Hox genes in limb development. Key signaling pathways and their targets in limb positioning and patterning.

The regulatory mechanisms controlling Hox gene expression during limb development operate at multiple levels, from initial body-axis positioning to fine-grained patterning within the limb bud itself. Retinoic acid (RA) signaling establishes proximal identity in the limb bud and activates Tbx5 in the forelimb field, while GDF11 signaling specifies hindlimb identity through activation of Pitx1 and Tbx4 [29]. The GDF11/SMAD2 pathway plays a particularly crucial role in activating posterior Hox genes (Hox10-13) that specify lumbar, sacral, and caudal vertebral identities, with recent research identifying Protogenin (Prtg) as a key enhancer of GDF11 signaling activity [30].

Within the limb bud itself, a bimodal regulatory system controls Hox gene expression through two topologically associating domains (TADs) flanking the Hox clusters. Genes in the 3' region of the HoxD cluster (Hoxd1-8) interact with the telomeric domain (T-DOM) controlling proximal limb patterning, while genes in the 5' region (Hoxd9-13) interact with the centromeric domain (C-DOM) controlling distal limb patterning [27] [28]. The Hoxd9-11 genes exhibit a unique regulatory strategy, initially interacting with T-DOM during proximal patterning and subsequently switching to C-DOM during distal patterning. This switch is facilitated by HOX13 proteins, which simultaneously inhibit T-DOM activity while reinforcing C-DOM function, creating a domain of low Hoxd expression that gives rise to the wrist and ankle articulations [28].

Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Gene Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene and Limb Development Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application in Limb Analysis | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis Tools | N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) | Induction of point mutations in Hox genes | [11] |

| Genetic Mapping Markers | Microsatellite markers (D2Mit329, D2Mit285) | Linkage analysis and mutation mapping | [11] |

| Skeletal Stains | Alcian Blue 8GX, Alizarin Red S | Cartilage and bone staining for patterning analysis | [11] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Visium, RNA-ISH | Mapping gene expression in tissue context | [26] |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | 10x Chromium platform | Resolving cellular heterogeneity in limb buds | [26] |

| Hox Cluster Modifiers | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, TALENs | Targeted mutagenesis of specific Hox genes | [6] |

| Signaling Agonists/Antagonists | RA, FGF, GDF11 modulators | Manipulating signaling pathways controlling Hox expression | [29] [30] |

| Epigenetic Regulators | WDR5 inhibitors (WDR5-IN-4) | Modifying Hox expression through epigenetic mechanisms | [31] |

The strategic selection of target Hox genes for compound mutant analysis requires careful consideration of several factors, including paralog group, genomic position within the cluster, expression timing, and functional redundancy. Based on current evidence, the following strategic framework is recommended:

First, prioritize 5' HoxD genes (Hoxd9-13) for investigations of autopod patterning and digit specification, as these exhibit the most profound effects on distal limb morphology when mutated. The generation of compound mutants targeting multiple 5' HoxD genes is likely necessary due to significant functional redundancy, as single mutants often produce relatively mild phenotypes.

Second, for studies of limb positioning and initiation, focus on HoxB cluster genes (particularly Hoxb4, Hoxb5) and their upstream regulators including retinoic acid and GDF11 signaling components. The recently identified role of Protogenin in enhancing GDF11/SMAD2 signaling represents a promising regulatory node for experimental manipulation [30].

Third, employ point mutagenesis approaches (e.g., ENU) rather than complete knockout strategies to model the subtle regulatory alterations that likely underlie evolutionary and pathological variations in limb morphology. The Hoxd12 point mutation study demonstrates how single amino acid changes can produce specific patterning defects without completely disrupting limb formation [11].

Finally, integrate advanced spatial transcriptomic methodologies to resolve Hox expression patterns with cellular resolution in both mouse and human embryonic limbs. The recent human embryonic limb cell atlas provides an essential reference for translating findings from mouse models to human development and disease contexts [26].

This strategic approach, leveraging both established and emerging technologies, will enable researchers to effectively dissect the complex regulatory hierarchies governing Hox gene function in limb development and ultimately advance our understanding of both normal morphogenesis and congenital limb abnormalities.

The generation of genetically engineered mouse models, particularly for the functional analysis of complex gene families like the Hox genes, relies on two cornerstone technologies: ES Cell Targeting and CRISPR-Cas9. These methods enable the creation of compound mutants essential for dissecting genetic interactions during limb development [32].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two primary technologies.

| Feature | ES Cell Targeting (Homologous Recombination) | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) using an exogenous DNA donor template [33]. | RNA-programmed DNA cleavage; leverages both HDR and error-prone NHEJ [33]. |

| Primary Application | High-fidelity gene knock-ins (e.g., gene correction) and specific point mutations [33]. | Highly efficient gene knockouts (via NHEJ) and knock-ins (via HDR) [33]. |

| Typical Timeline | 12-18 months for mutant mouse generation. | Can be as short as 6 months, significantly accelerating model generation. |

| Throughput | Lower throughput; typically one genetic modification per targeting effort. | High throughput; facilitates multiplexed editing of several loci simultaneously [34]. |

| Technical Barrier | High; requires sophisticated skills in molecular biology and stem cell culture. | Low; utilizes simple sgRNA design, making it accessible to most labs [33] [34]. |

| Key Considerations | Considered the "gold standard" for precise alterations but is cumbersome and labor-intensive [33]. | Potential for off-target effects and unexpected on-target structural variants [35]. |

Application in Hox Compound Mutant Generation for Limb Research

Hox genes are master regulators of limb patterning, functioning in a dose-dependent and genetically interactive manner [36] [32]. Analyzing their complex roles requires the generation of compound mutants, a task for which both ES cell targeting and CRISPR-Cas9 are employed.

ES Cell Targeting for Hox Mutants

This traditional method involves sequential targeting of Hox loci in embryonic stem (ES) cells. For instance, studies on the interaction between Shox2 and Hox genes used mice with HoxA/D cluster deletions generated via ES cell targeting to demonstrate their coordinated role in proximal limb growth and Runx2 expression [32]. While powerful, creating multiple mutations is time-consuming.

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Hox Compound Mutants

CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized the rapid generation of compound mutants. A typical workflow for creating Hox compound mutants is outlined below.

Key Considerations for CRISPR-Cas9 in Hox Research

- On-target Structural Variants: Studies in zebrafish show that CRISPR-Cas9 can induce large, unexpected insertions, deletions, and other structural variants (SVs) at on-target sites in about 6% of editing outcomes [35]. These SVs can be passed to offspring.

- Minimizing Risks: Using lower concentrations of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes over plasmid-based delivery can reduce off-target effects. Long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio) is recommended for comprehensive genotyping of founder animals to detect SVs that short-read sequencing would miss [35].

- Phenotypic Analysis: For limb analysis, mutants are typically processed for skeletal staining (e.g., Alcian Blue for cartilage and Alizarin Red for bone) to reveal morphological defects in the stylopod, zeugopod, and autopod [37]. Molecular analysis includes in situ hybridization to examine the expression of Hox genes and their targets (e.g., Shh, Fgf4, Lmx1b) [37] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below lists essential reagents and their functions for generating Hox mutant mice via CRISPR-Cas9.

| Research Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| sgRNAs | Synthetic single-guide RNAs designed to target specific exons or regulatory regions of Hox genes. Essential for directing Cas9 to the desired genomic locus [33] [34]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | The RNA-programmable DNA endonuclease enzyme that creates double-strand breaks. Can be delivered as mRNA, protein, or encoded in a plasmid [34]. |

| HDR Donor Template | A single-stranded or double-stranded DNA vector containing homologous arms and the desired sequence modification (e.g., a loxP site, a point mutation). Used for precise knock-ins [33]. |

| Microinjection Setup | Equipment including a microinjector, manipulators, and a microscope for delivering CRISPR reagents directly into fertilized mouse zygotes. |

| Genotyping Primers | PCR primers designed to flank the targeted Hox locus to detect and characterize induced mutations in founder animals and their progeny. |

| Long-read Sequencer | Platform like PacBio Sequel used for validating on-target edits and, critically, for detecting large structural variants that are a known adverse effect of CRISPR editing [35]. |

Hox Gene Function and Regulatory Pathways in Limb Development

Hox genes, particularly from the HoxA and HoxD clusters, are fundamental to vertebrate limb patterning, controlling the identity of structures along the proximodistal axis [36]. The following diagram illustrates the key regulatory pathways involving Hox genes during limb development.

As illustrated, Hox genes sit atop a complex regulatory network. They regulate key signaling centres like the zone of polarizing activity (producing Shh) and the apical ectodermal ridge (producing FGFs) [36]. These pathways interact in feedback loops to control the expression of downstream effectors. For example:

- Hoxd12 point mutation studies show dramatic upregulation of Fgf4 and Lmx1b, leading to shortening of the zeugopod and autopod, and missing digit tips, without altering Shh expression [37].

- Genetic interaction studies show that Shox2 and Hox genes function synergistically upstream of Runx2 to drive cartilage maturation in the proximal limb (stylopod) [32].

Breeding Schemes for Generating Compound Heterozygous and Homozygous Mutants

Within the context of a broader thesis on the generation of Hox compound mutant mice for limb analysis research, the need for precise breeding protocols is paramount. The functional redundancy inherent among the 39 mammalian Hox genes, which are organized into four clusters (A-D) and 13 paralog groups, necessitates the creation of multi-gene mutants to fully elucidate their roles in limb patterning [38]. Single Hox gene mutations often yield subtle phenotypes, whereas combined mutations in paralogous and flanking genes reveal profound defects in limb development, including dramatic truncations of the stylopod (e.g., humerus), zeugopod (e.g., ulna/radius), and autopod (e.g., digits) [38] [39]. This application note provides detailed methodologies for generating and analyzing these essential genetic models, with a focus on limb skeletal morphogenesis.

Genetic Intervention Strategies and Rationale

The following table summarizes the key Hox gene combinations, their observed limb phenotypes, and the genetic strategies employed, as evidenced by recent and seminal research.

Table 1: Hox Compound Mutant Phenotypes and Breeding Strategies in Limb Development

| Targeted Hox Genes | Limb Phenotype Observed | Genetic Engineering Strategy | Key Signaling Pathways Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxa11/Hoxd11 [38] [39] | Misshapen or reduced ulna/radius; fusion of carpal bones [39]. | Targeted gene disruption via homologous recombination [39]. | Delayed chondrocyte hypertrophy; altered Bmpr1b, Gdf5, Runx3 expression [38]. |

| Hoxa9,10,11/Hoxd9,10,11 [38] | Severe reduction of ulna/radius; reduced Shh and Fgf8 expression [38]. | Simultaneous frameshift mutation via recombineering [38]. | Strongly downregulated Shh (ZPA) and Fgf8 (AER); altered Gdf5, Bmpr1b, Igf1 [38]. |

| Hoxd12 Point Mutation [11] | Microdactyly, shortened digits, missing digit I tip, zeugopod defects. | N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis followed by positional cloning [11]. | Dramatic increase in Fgf4 and Lmx1b; no change in Shh [11]. |

| Hoxd-12 & Hoxd-13 Trans-heterozygotes [40] | Severe carpal, metacarpal, and phalangeal defects; extra rudimentary digit. | Breeding of single targeted mutants to produce trans-heterozygotes [40]. | Delay in ossification; failure of fusion/elimination of cartilaginous elements [40]. |

| Hoxa1 Knock-out [41] | Hindbrain defects impacting respiratory neural circuits; not a primary limb mutant. | Targeted inactivation (Hoxa1-/-) [41]. | Altered hindbrain segmentation and neuronal network formation [41]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mutant Generation and Analysis

Recombineering for Multi-Gene Frameshift Mutations

This protocol is adapted from studies generating Hoxa9,10,11/Hoxd9,10,11 mutants, allowing for the disruption of multiple flanking genes while preserving cluster integrity and regulatory elements [38].

Key Reagents:

- Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs): Containing the murine HoxA and HoxD genomic loci.

- Recombineering Plasmid: Expressing phage-derived recombination proteins (e.g., λ Red system).

- Targeting Vectors: Designed to introduce frameshift mutations (e.g., via single base insertions/deletions) into exons of Hoxa9, Hoxa10, Hoxa11, Hoxd9, Hoxd10, and Hoxd11.

- Mouse Embryonic Stem (ES) Cells: C57BL/6-derived or similar.

Detailed Workflow:

- Vector Construction: Design and synthesize oligonucleotides to create targeting vectors for each of the six genes. The vectors should contain a short homologous arm (~50 bp) matching the target exon site, the desired frameshift mutation, and a selectable marker (e.g., FRT-flanked neomycin resistance cassette) for downstream removal.

- BAC Recombineering: Transform the Hox BAC and the recombineering plasmid into an appropriate E. coli host. Induce the recombination system and electroporate the pooled targeting vectors into the cells. Select for clones where homologous recombination has successfully introduced the frameshifts.

- ES Cell Targeting: Linearize the modified BAC and electroporate into mouse ES cells. Select for successfully targeted ES cells using the appropriate antibiotic.

- Mouse Generation: Inject the targeted ES cells into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. Breed chimeras to obtain germline transmission of the mutant alleles.

- Marker Excision: Cross the mutant mice with a Flp deleter strain to remove the FRT-flanked selection cassette, leaving behind only the frameshift mutation.

ENU Mutagenesis and Phenotype-Driven Screening

This approach, as used to identify the Hoxd12 point mutant, is ideal for discovering novel alleles without a priori assumptions about the target gene [11].

Key Reagents:

- N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU): Potent alkylating mutagen.

- BALB/cJ Mice: Or other inbred strains suitable for ENU mutagenesis.

- Taq Polymerase and Sequencing Reagents: For genotyping and mutation detection.

Detailed Workflow:

- Mutagenesis: Inject male BALB/cJ mice intraperitoneally with ENU (e.g., 100 mg/kg) twice, with a two-week interval between injections [11].

- G0 Founder Generation: Allow the injected males (G0) to recover and then mate them with wild-type females to produce G1 offspring, which are heterozygous for random mutations.

- Three-Generation Breeding Screen:

- G1: Screen for dominant phenotypes. Alternatively, use G1 males to set up the next cross.

- G2: Cross G1 males with wild-type females to produce G2 females, which are bred back to their G1 father.