Hox Genes in Limb Positioning: A Cross-Species Analysis from Development to Disease

This review synthesizes cutting-edge research on the expression and function of Hox genes in vertebrate limb positioning, offering a cross-species comparative analysis.

Hox Genes in Limb Positioning: A Cross-Species Analysis from Development to Disease

Abstract

This review synthesizes cutting-edge research on the expression and function of Hox genes in vertebrate limb positioning, offering a cross-species comparative analysis. We explore the foundational principles of Hox-directed positional identity in model organisms, including mice, zebrafish, and anurans, and detail advanced methodologies for analyzing their expression and function. The article addresses common challenges in Hox research, such as gene redundancy and phenotypic interpretation, and provides validation strategies through comparative studies of paralogous groups and cluster deletions. Finally, we discuss the translational implications of Hox genes in congenital disorders, tissue regeneration, and neurodegenerative disease, providing a critical resource for developmental biologists and biomedical researchers aiming to leverage Hox biology for therapeutic innovation.

Positional Blueprints: How Hox Genes Establish the Limb Axis Across Species

The Hox code represents a fundamental principle in developmental biology, where a family of transcription factors provides positional information along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis to orchestrate the formation of distinct anatomical structures in vertebrate embryos. These genes are arranged in four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) on different chromosomes and exhibit two remarkable properties: temporal collinearity, where genes are activated sequentially from 3' to 5' during gastrulation, and spatial collinearity, where their expression domains along the A-P axis correspond to their genomic position within the clusters [1] [2]. This sophisticated regulatory system patterns diverse anatomical features from vertebrae to limbs, and its disruption can lead to profound developmental abnormalities. Cross-species analyses from zebrafish to humans reveal that while the core Hox patterning mechanism is deeply conserved, modifications to its implementation contribute to the remarkable diversity of body plans observed across vertebrates [3] [4]. This guide systematically compares the conserved principles and species-specific variations in Hox code function, providing researchers with experimental insights and methodological approaches for investigating this crucial patterning system.

Fundamental Principles of the Hox Code System

The Hox gene family encodes transcription factors characterized by a conserved DNA-binding homeodomain that directly regulates downstream target genes. The chromosomal organization of Hox genes is not arbitrary but directly reflects their functional roles along the A-P axis. Genes at the 3' end of each cluster pattern anterior structures, while those at the 5' end specify posterior identities [2]. This genomic arrangement enables coordinated regulation through shared enhancer elements and chromatin landscapes, as demonstrated by chromosome conformation studies showing that the HoxD cluster lies between two topologically associating domains (TADs) containing distinct enhancer sets for autopod (digit) versus zeugopod (forearm) patterning [5].

The Hox code operates through combinatorial expression rather than individual gene action. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses of developing mouse limbs reveal surprising heterogeneity in Hox gene expression at the cellular level, with individual cells expressing specific combinations of Hoxd genes despite sharing common enhancer regulation [5]. This cellular-level complexity allows for refined patterning outcomes from a limited set of transcription factors.

Molecular Regulation Mechanisms:

- CTCF-mediated chromatin organization: Controls sequential Hox gene activation during gastrulation [2]

- Enhancer sharing and competition: Multiple Hox promoters compete for access to shared enhancer elements [5]

- Auto-regulatory and cross-regulatory networks: Hox proteins regulate their own and each other's expression [6]

- Cellular memory mechanisms: Maintain positional identity through development via epigenetic modifications

The regulatory logic of the Hox code extends beyond simple activation to include complex repression mechanisms that define anatomical boundaries. For example, in chick embryos, Hoxc9 represses forelimb initiation in posterior regions, while simultaneously patterning thoracic vertebrae, demonstrating how the same Hox gene can execute distinct positional functions in different tissues [1].

Cross-Species Analysis of Hox Code Function

Vertebrate Conservation from Zebrafish to Mammals

Functional studies across vertebrate models demonstrate remarkable conservation of core Hox patterning mechanisms. Recent zebrafish genetic analysis shows that Hox genes in HoxB and HoxC clusters pattern anterior vertebrae, with Hoxc6 specifying vertebral identity in a mechanism conserved with tetrapods [3]. Similarly, mouse models reveal that Hoxa11 mutants exhibit abnormal sesamoid bone development in forelimbs, while Hoxd11 mutants show aberrant sesamoid formation between the radius and ulna [4].

Human developmental studies using single-cell RNA sequencing of fetal spines between 5-13 weeks post-conception identify a conserved rostrocaudal Hox code comprising 18 position-specific Hox genes across stationary cell types, with osteochondral cells exhibiting the broadest Hox expression profile [2]. This human Hox atlas confirms the fundamental conservation of principles first identified in model organisms while revealing human-specific expression patterns in certain cell types.

Table 1: Hox Gene Functional Conservation Across Vertebrate Species

| Species | Hox Genes | Patterning Role | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | HoxB/HoxC cluster genes | Anterior vertebral patterning | Micro-CT scanning of various Hox mutants [3] |

| Chicken | Hoxb4, Hoxc9, Hoxb5 | Forelimb positioning | Electroporation, dominant-negative constructs, live imaging [1] [6] |

| Mouse | Hoxa11, Hoxd11, Hoxd13 | Limb patterning & sesamoid development | Genetic knockouts, single-cell RNA-seq, RNA-FISH [4] [5] |

| Human | 18-gene Hox code | Spinal patterning across cell types | Single-cell & spatial transcriptomics, in-situ sequencing [2] |

| Carnivora | Hoxc10 | Pseudothumb development | Comparative genomics, selection analysis [4] |

Evolutionary Adaptation and Specialization

While the core Hox code mechanism is conserved, species-specific modifications underlie anatomical adaptations. In Carnivora, Hoxc10 shows evidence of convergent evolution between giant and red pandas, potentially contributing to pseudothumb development [4]. Marine carnivores like pinnipeds and sea otters demonstrate how limb modifications to flippers may involve selected changes in Hox gene regulation, though with different genetic mechanisms than terrestrial specialists.

Avian species display remarkable natural variation in forelimb position, from sparrows (10th vertebra) to swans (25th vertebra), correlated with changes in Hox gene collinear activation timing during gastrulation [1]. Comparative analysis of zebra finch, chicken, and ostrich development reveals that heterochrony—changes in developmental timing—in Hox gene activation contributes to this diversity in limb positioning [7].

Table 2: Hox Code Variations in Evolutionary Adaptations

| Adaptation | Species Example | Hox Genes Involved | Regulatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudothumb development | Giant & red panda | Hoxc10 | Convergent amino acid evolution [4] |

| Forelimb position diversity | Avian species | Hoxb4, Hoxb9 | Heterochrony in collinear activation [1] [7] |

| Hindlimb identity | Multiple tetrapods | Tbx4, Pitx1 | Downstream of Hox code [8] |

| Flipper development | Pinnipeds, sea otter | Hox9-13 genes | Positive selection signals [4] |

| Axial skeleton patterning | All vertebrates | Hoxc6 | Conserved from fish to mammals [3] |

Experimental Analysis of Hox Code Function

Key Methodologies and Their Applications

Functional dissection of the Hox code employs sophisticated genetic, genomic, and imaging approaches. Single-cell RNA sequencing has revolutionized our understanding of Hox heterogeneity, revealing that only a minority of limb bud cells co-express expected Hox gene combinations simultaneously [5]. Spatial transcriptomics techniques like Visium (50μm resolution) and higher-resolution in-situ sequencing enable precise mapping of Hox expression patterns within developing tissues while maintaining anatomical context [2].

Genetic perturbation approaches include:

- Dominant-negative constructs: Electroporation of truncated Hox proteins that disrupt native function [6]

- Temporal-specific electroporation: Enables stage-specific manipulation of Hox expression in chick embryos [1]

- CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis: Generates targeted Hox mutations in model organisms [3]

- Lineage tracing and live imaging: Tracks cell fate decisions during gastrulation [1] [7]

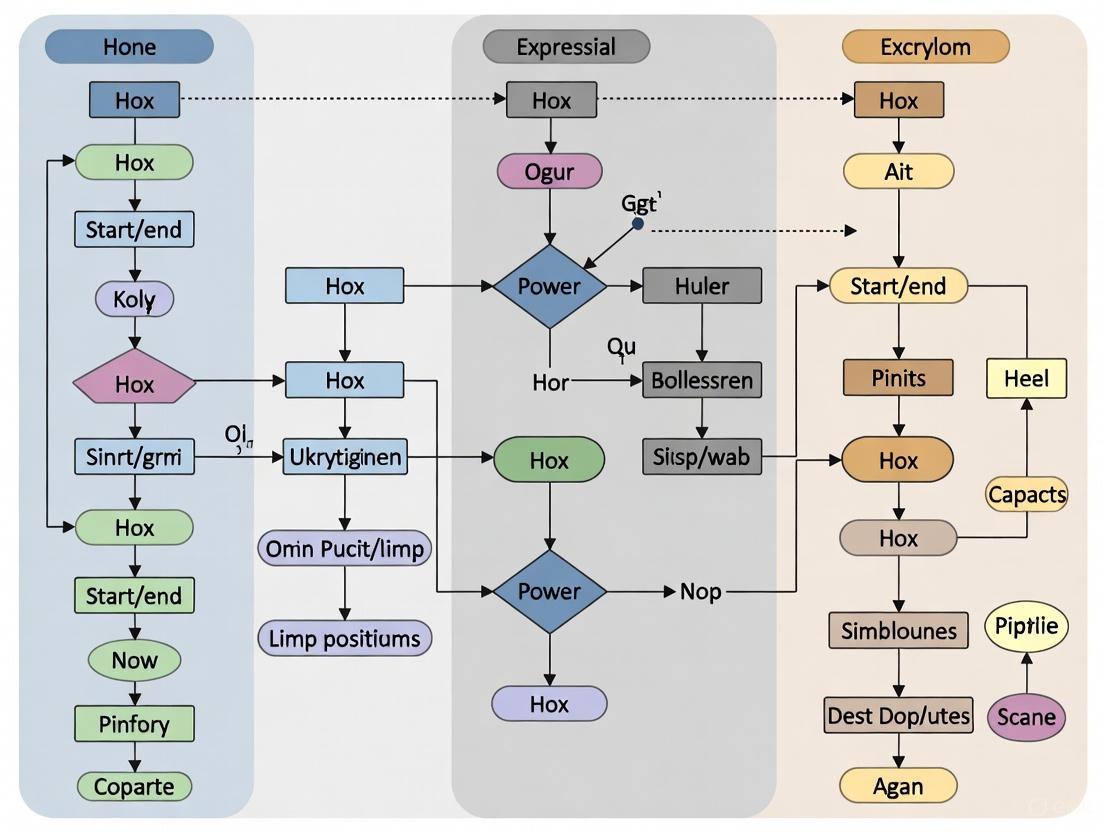

Experimental Workflow for Hox Code Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental pipeline for analyzing Hox code function, integrating multiple contemporary approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Code Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Example Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant-negative Hox constructs | Loss-of-function studies | Hoxa4, a5, a6, a7 DN forms in chick LPM | [6] |

| Hox-reporter transgenic lines | Lineage tracing, cell sorting | Hoxd11::GFP mice for FACS isolation | [5] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq platforms | Cellular heterogeneity analysis | Fluidigm C1 for limb bud transcriptomes | [5] |

| Spatial transcriptomics (Visium) | Anatomical expression mapping | Human fetal spine Hox code mapping | [2] |

| In-situ sequencing (Cartana) | High-resolution spatial analysis | 123-gene panel in human fetal sections | [2] |

| Micro-CT scanning | Phenotypic analysis | Zebrafish vertebral patterning in Hox mutants | [3] |

| Species-specific genomes | Comparative genomics | Carnivora Hox gene selection analysis | [4] |

The Hox code represents a paradigmatic example of evolutionary developmental biology, where deeply conserved genetic mechanisms are adapted to generate diverse anatomical outcomes. The fundamental principles of temporal and spatial collinearity, combinatorial gene expression, and hierarchical regulatory networks operate across vertebrates from zebrafish to humans [3] [2]. However, modifications in the timing of Hox gene activation, specific amino acid changes, and alterations to downstream regulatory networks enable species-specific adaptations in limb positioning, vertebral identity, and specialized structures like pseudothumbs [1] [4].

For researchers investigating Hox gene function, the integrated experimental approaches outlined here—combining single-cell genomics, spatial mapping, and precise genetic perturbations—provide powerful tools to dissect both conserved and species-specific aspects of the Hox code. These methodologies enable the transition from correlative observations to functional understanding of how Hox patterns are established, maintained, and evolved across vertebrate species.

Future research directions will likely focus on understanding the single-cell heterogeneity of Hox expression, the three-dimensional chromatin architecture enabling precise Hox regulation, and how Hox codes integrate with other patterning systems to generate complex morphological structures. Such investigations will continue to reveal how conserved genetic toolkits generate both stability and diversity in vertebrate body plans.

Hox genes are a family of highly conserved homeodomain-containing transcription factors that serve as master regulators of embryonic development. These genes instruct positional identity along the anterior-posterior (AP) body axis, defining regional morphology in all bilaterian animals [9]. First described in Drosophila, these genes exhibit collinear expression—their order on chromosomes corresponds with their spatial and temporal activation domains [9]. In mammals, genome duplication events have resulted in 39 Hox genes arranged in four clusters (HoxA, B, C, and D), further subdivided into 13 paralogous groups [9]. These genes employ both distinct and overlapping functions to pattern different body regions, with particularly fascinating differences in their roles in axial versus limb patterning. This comparative analysis examines the mechanistic differences in Hox gene function between these two fundamental patterning systems, synthesizing findings from cross-species research to elucidate conserved principles and specialized adaptations.

Hox Gene Functions in Axial Patterning

The Combinatorial Hox Code Model

The vertebrate axial skeleton, comprising the skull, vertebrae, and ribs, is patterned through a sophisticated combinatorial Hox code. In this model, the morphological identity of each vertebra is determined by the specific combination of Hox genes expressed in that region [10] [11] [12]. Unlike the limb skeleton, where Hox paralog groups function in discrete domains, axial patterning involves significant functional overlap between paralogs, with multiple Hox genes contributing to each vertebral segment's identity [9]. This system creates a precise pattern of cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and caudal vertebrae through region-specific expression combinations along the AP axis [11].

Table 1: Hox Gene Functions in Vertebrate Axial Patterning

| Paralog Group | Vertebral Region | Transformation Phenotype | Nature of Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox4-5 | Cervical/Anterior Thoracic | Anteriorization | Altered cervical/thoracic boundary identity |

| Hox9 | Posterior Thoracic | Anteriorization | Extension of thoracic characteristics (e.g., rib formation) |

| Hox10 | Lumbar | Anteriorization | Ectopic rib formation on lumbar vertebrae |

| Hox11 | Sacral | Anteriorization | Altered sacro-caudal boundary identity |

Experimental Evidence from Mutant Models

Genetic evidence supporting the combinatorial model comes from extensive loss-of-function studies in mice. For example, loss of Hox10 paralogous group function results in anterior homeotic transformations where lumbar vertebrae acquire characteristics of more anterior thoracic vertebrae, including the formation of ectopic ribs [9]. Similarly, complete loss of Hox11 function causes sacral vertebrae to assume a lumbar identity [9]. These transformations occur because the remaining Hox genes in the region provide patterning information, resulting in adoption of a more anterior fate rather than complete loss of structural identity [9]. The redundant functionality between paralogs is evidenced by the fact that single gene knockouts often produce mild phenotypes, while compound mutants (lacking multiple paralogs) show dramatic homeotic transformations [13].

Hox Gene Functions in Limb Patterning

Segmental Specification Along the Proximodistal Axis

In contrast to the combinatorial system used in axial patterning, limb patterning employs a segmental specification model where different Hox paralog groups control distinct limb segments along the proximodistal (PD) axis [9] [14]. The vertebrate limb comprises three main segments: the stylopod (humerus/femur), zeugopod (radius-ulna/tibia-fibula), and autopod (hand/foot). Each segment is primarily patterned by specific Hox paralog groups with minimal functional overlap [9].

Table 2: Hox Gene Functions in Vertebrate Limb Patterning

| Paralog Group | Limb Segment | Loss-of-Function Phenotype | Key Regulatory Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox9 | Proximal Stylopod | Severe stylopod mis-patterning | Initiates Shh expression via Hand2 and Gli3 regulation |

| Hox10 | Stylopod | Severe stylopod mis-patterning | Required for proximal skeletal element formation |

| Hox11 | Zeugopod | Severe zeugopod mis-patterning; loss of radius/ulna | Essential for zeugopod specification |

| Hox12-13 | Autopod | Complete loss of autopod elements | Controls distal limb patterning and digit formation |

Coordination of Limb Axes and Tissue Integration

Hox genes coordinate patterning along all three limb axes (AP, PD, and dorsoventral). Posterior Hox genes (particularly HoxA and HoxD clusters) establish the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) by regulating Sonic hedgehog (Shh) expression [14]. For example, Hox9 genes promote posterior Hand2 expression, which inhibits the hedgehog pathway inhibitor Gli3, allowing induction of Shh expression [9]. Simultaneously, Hox genes pattern the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) through regulation of Fgf signaling [14]. This integrated approach ensures coordinated outgrowth and patterning. Additionally, Hox genes expressed in connective tissues help integrate the musculoskeletal system by coordinating the patterning of muscle, tendon, and bone components derived from different embryonic origins [9].

Comparative Analysis: Key Distinctions and Overlapping Principles

Fundamental Differences in Patterning Strategies

The comparison between axial and limb patterning reveals fundamentally different strategies employed by Hox genes. In axial patterning, the system utilizes combinatorial codes with extensive paralog redundancy, where multiple Hox genes contribute to each vertebral segment's identity [9] [11]. In contrast, limb patterning employs modular specification with limited redundancy, where discrete paralog groups control specific limb segments [9] [14]. This distinction is evident in mutant phenotypes: axial patterning mutants typically show homeotic transformations (one structure transforms into another), while limb patterning mutants exhibit segment loss or severe malformation of specific limb regions [9].

Conserved Regulatory Principles

Despite these differences, both systems share the fundamental principle of temporal and spatial collinearity. In both contexts, Hox genes are activated in a sequence that corresponds to their chromosomal order, with 3' genes expressed earlier and more anteriorly/proximally than 5' genes [9] [14]. Additionally, both systems employ the principle of posterior prevalence, where more posteriorly-expressed Hox proteins dominate in functional activity over those expressed more anteriorly when co-expressed in the same cell [14]. Both systems also utilize compartment-specific expression, with Hox genes acting in mesenchymal compartments rather than differentiated skeletal cells—in the limb, they pattern connective tissues that subsequently guide musculoskeletal integration, while in the axis they pattern pre-somitic mesoderm [9].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genetic Manipulation Techniques

The foundational experiments elucidating Hox functions have employed both loss-of-function and gain-of-function approaches in model organisms. Targeted gene disruption in mice remains the gold standard for determining gene function, with single, double, and compound mutants revealing both unique and redundant functions [13]. For example, Fromental-Ramain et al. (1996) demonstrated that Hoxa-9 and Hoxd-9 have both specific and redundant functions in forelimb and axial skeleton patterning through systematic single and double knockout approaches [13]. Tissue-specific manipulation techniques, particularly important for distinguishing direct versus indirect effects, include Cre-lox mediated conditional knockout and limb-specific electroporation of dominant-negative constructs [6].

Molecular Analysis Methods

Molecular analyses of Hox function employ diverse methodologies. Gene expression analysis via in situ hybridization reveals spatial and temporal expression patterns, while lineage tracing determines cell fate restrictions. Gene expression profiling in mutant backgrounds has identified downstream targets, revealing that Hox proteins regulate genes involved in cell adhesion, extracellular matrix composition, and signaling pathways [14]. For example, transcriptional profiling of Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 mutants has identified targets involved in endochondral bone formation [14]. Additionally, cross-species comparative approaches examine Hox expression and function across vertebrates (mice, chicks, fish) and invertebrates to elucidate evolutionary conservation and divergence [15] [14].

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Hox Gene Functional Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Model Systems | Mouse (Mus musculus), Chick (Gallus gallus), Frog (Xenopus) | Loss/gain-of-function studies, evolutionary comparisons | Provide in vivo systems for manipulating and analyzing Hox function |

| Gene Expression Tools | In situ hybridization probes, RNAscope assays, scRNA-seq | Spatial localization of Hox transcripts, identification of expression domains | Enable visualization of Hox mRNA distribution in tissues |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, Cre-lox system | Targeted gene knockout, conditional mutagenesis, lineage tracing | Allow precise manipulation of Hox genes in specific tissues/timepoints |

| Antibody Reagents | Anti-HOX antibodies, anti-GFP tags | Protein localization, cell fate mapping, tissue staining | Enable detection of Hox protein expression and distribution |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | Retinoic acid, Cyclopamine (Shh inhibitor) | Ectopic limb induction, pathway inhibition studies | Probe Hox gene regulation and function in patterning |

Evolutionary Perspectives and Cross-Species Conservation

Hox gene functions in axial and limb patterning exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation across vertebrates, with similar paralog groups governing comparable morphological domains in mice, chicks, and humans [12] [14]. The deep evolutionary origin of Hox genes is evidenced by their presence in cnidarians, the sister group to bilaterians, though their role in axial patterning in these early diverging animals remains debated [16]. In vertebrates, a significant evolutionary event was the duplication of Hox clusters, which allowed for functional specialization and increased morphological complexity [17]. Cross-species comparisons reveal that while the core functions are conserved, species-specific adaptations have arisen through changes in Hox expression domains and regulatory networks. For example, in snakes, modifications in Hox10 and Hox11 expression correlate with their extensive rib formation and loss of limb development [17]. Similarly, experimental evidence from anuran tadpoles demonstrates that vitamin A-induced homeotic transformations involve Hox gene regulation, with downregulation of posterior Hox genes preceding ectopic limb formation [15].

Hox genes employ distinct strategies to pattern the axial skeleton and limbs, utilizing combinatorial codes with redundancy in the former and modular specification in the latter. However, both systems operate through the fundamental principles of collinearity and posterior prevalence. The experimental approaches outlined, from genetic manipulations in model organisms to molecular analyses of gene expression, have been essential in deciphering these complex patterning systems. As research continues, emerging technologies in single-cell analysis and genome editing will further refine our understanding of Hox gene networks, potentially revealing new insights for regenerative medicine and evolutionary developmental biology. The conservation of these patterning mechanisms across species underscores their fundamental importance in animal development while providing a framework for understanding how morphological diversity evolves through modifications of shared genetic programs.

The precise positioning of paired appendages along the anterior-posterior axis is a fundamental process in vertebrate development. While Hox genes have long been hypothesized to control limb position, conclusive genetic evidence has remained elusive. Recent groundbreaking research utilizing zebrafish knockout models provides definitive proof that HoxB-derived clusters function as master regulators of pectoral fin positioning. This review synthesizes findings from pivotal studies demonstrating that combined deletion of hoxba and hoxbb clusters completely abolishes pectoral fin formation, identifies specific Hox genes responsible for this patterning, and elucidates the molecular mechanisms through which these genes establish positional information. We present comprehensive comparative analysis of experimental approaches, phenotypic outcomes, and molecular data that collectively establish a new paradigm for understanding Hox-mediated control of appendage positioning across vertebrate species.

Hox genes, encoding evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, constitute a fundamental regulatory system for patterning the anterior-posterior axis in bilaterian animals [18]. These genes are characterized by their unique genomic organization into clusters and the phenomenon of collinearity, wherein their order within clusters corresponds to their spatial and temporal expression domains along the developing embryo [18] [19]. In vertebrates, Hox genes have undergone complex evolutionary histories, with teleost fishes like zebrafish possessing seven hox clusters resulting from an additional teleost-specific whole-genome duplication [20].

The hypothesis that Hox genes determine limb position has been supported by correlative evidence for decades. Comparative studies across species revealed that Hox gene expression boundaries align with future limb positions, and experimental manipulations in avian embryos demonstrated that altering Hox expression could shift limb bud formation [1] [21]. However, genetic evidence from knockout models in mice has been surprisingly limited, with most single and compound Hox mutants showing only subtle alterations in limb positioning rather than complete absences [22] [20]. This discrepancy between correlative evidence and functional genetic validation has represented a significant gap in the field of developmental biology.

Key Experimental Findings: Genetic Evidence from Zebrafish Knockout Models

Comprehensive Hox Cluster Deletion Strategy

In a series of innovative experiments, researchers generated seven distinct hox cluster-deficient mutants in zebrafish using the CRISPR-Cas9 system [22] [20]. This systematic approach enabled unprecedented analysis of functional requirements and redundancies among the duplicated hox clusters in teleosts. The experimental strategy involved:

- Targeted deletion of entire hox clusters rather than individual genes

- Combinatorial crosses to generate double and triple cluster mutants

- Phenotypic analysis across developmental stages (3-5 days post-fertilization)

- Molecular characterization via in situ hybridization and genotyping

This comprehensive genetic approach revealed that while single hox cluster deletions produced mild phenotypes, specific double mutants exhibited severe developmental defects, uncovering essential functions masked by paralogous redundancy.

Hoxba;hoxbb Double Mutants Exhibit Complete Absence of Pectoral Fins

The most striking finding emerged from analysis of hoxba;hoxbb double-deletion mutants, which specifically exhibited a complete absence of pectoral fins [22] [20]. This phenotype displayed complete penetrance, with all double homozygous mutants (15/252 embryos) lacking pectoral fins entirely. Critical observations included:

- Specificity: The pectoral fin absence was specific to hoxba;hoxbb deletion, with other cluster combinations not recapitulating this severe phenotype

- Gene dosage sensitivity: hoxba⁻/⁻;hoxbb⁺/⁻ and hoxba⁺/⁻;hoxbb⁻/⁻ heterozygotes developed normal pectoral fins, demonstrating that one functional allele from either cluster suffices for fin formation

- Developmental timing: The fin formation failure occurred at the earliest stages of pectoral fin field specification

- Lethality: Double homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal around 5 dpf, preventing analysis of later developmental processes

Table 1: Phenotypic Spectrum of Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Penetrance | Additional Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba⁻/⁻ | Morphological abnormalities | Partial | Reduced tbx5a expression |

| hoxbb⁻/⁻ | Normal | - | None reported |

| hoxba⁻/⁻;hoxbb⁻/⁻ | Complete absence | 100% | Embryonic lethal at ~5 dpf |

| hoxaa⁻/⁻;hoxab⁻/⁻;hoxda⁻/⁻ | Severe shortening | 100% | Defective endoskeletal disc and fin-fold |

Molecular Mechanism: Abrogation of tbx5a Expression and Retinoic Acid Competence

The mechanistic basis for the absent pectoral fins in hoxba;hoxbb mutants involves failure of the fundamental genetic program initiating fin bud formation [22]. Molecular analyses revealed:

- tbx5a absence: Expression of tbx5a, a transcription factor essential for pectoral fin bud initiation, is completely absent in the lateral plate mesoderm of double mutants

- Early failure: tbx5a expression fails to be induced at the initial stages of pectoral fin field specification, indicating loss of pectoral fin precursor cells

- Retinoic acid incompetence: The mutants lose competence to respond to retinoic acid, a key signaling molecule involved in limb patterning

- Specific Hox requirements: Follow-up studies identified hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as pivotal genes underlying this process, though frameshift mutations in these individual genes did not fully recapitulate the cluster deletion phenotype

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutagenesis

The foundational methodology enabling these discoveries involved CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of entire hox clusters [22] [20]. The technical approach included:

- Guide RNA design: Multiple gRNAs targeting flanking regions of each hox cluster

- Microinjection: Delivery of Cas9 protein and gRNAs into single-cell zebrafish embryos

- Deletion verification: PCR-based genotyping to confirm large deletions (typically >10 kb)

- Stable line establishment: Outcrossing of founders and establishment of homozygous lines

This methodology allowed for the generation of clean deletion mutants without off-target effects, enabling precise functional analysis of each cluster.

Phenotypic and Molecular Analysis

Comprehensive characterization of mutant phenotypes employed multiple established developmental biology techniques:

- Morphological analysis: Brightfield microscopy to document fin development at 3-5 dpf

- Whole-mount in situ hybridization: Spatial analysis of gene expression patterns (tbx5a, shha)

- Cartilage staining: Alcian blue staining to visualize cartilage elements in larval pectoral fins

- Micro-CT scanning: Detailed analysis of skeletal structures in adult mutants

These methodologies provided multi-dimensional assessment of phenotypic consequences at morphological, cellular, and molecular levels.

Comparative Analysis Across Vertebrate Models

Zebrafish Versus Mouse Hox Mutant Phenotypes

The dramatic phenotype observed in zebrafish hoxba;hoxbb mutants contrasts sharply with previously reported Hox mouse mutants, highlighting both conserved and divergent functions [20].

Table 2: Cross-Species Comparison of Hox Mutant Limb/Fin Phenotypes

| Species/Model | Genetic Manipulation | Limb/Fin Phenotype | Molecular Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | hoxba;hoxbb deletion | Complete absence of pectoral fins | No tbx5a induction in LPM |

| Mouse | Hoxb5 knockout | Rostral shift of forelimbs (incomplete penetrance) | Minor alterations in limb position |

| Mouse | Hoxc10 knockout | Hindlimb patterning defects | Altered Tbx4 expression |

| Chick | Hoxc9 dominant-negative + Hoxb4 overexpression | Ectopic Tbx5 expression and shifted limb position | Expansion of forelimb field |

| Mouse | HoxA+HoxD cluster deletion | Severe limb truncation | Normal initial limb bud formation |

Evolutionary Insights: Conserved and Divergent Mechanisms

The zebrafish findings provide important evolutionary perspectives on the origin of paired appendages:

- Deep functional conservation: The role of Hox genes in appendage positioning represents an ancient evolutionary mechanism predating the divergence of ray-finned and lobe-finned fishes

- Teleost-specific adaptations: Gene duplication events in teleosts have led to subfunctionalization between co-orthologs, with hoxba and hoxbb clusters retaining complementary functions in fin positioning

- Differential redundancy: The complete loss of pectoral fins only in double mutants demonstrates how genome duplication can create genetic buffering systems that mask essential developmental functions

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Networks

The molecular hierarchy governing pectoral fin positioning involves a complex genetic network with Hox genes at the apex, regulating key signaling pathways and downstream effectors.

Hox Gene Regulation of Fin Development: This diagram illustrates the genetic hierarchy through which HoxB-derived clusters control pectoral fin positioning in zebrafish. The hoxba and hoxbb clusters regulate specific Hox genes (hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b) that establish retinoic acid competence in the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) and directly induce tbx5a expression, which subsequently activates Fgf10 and the broader limb initiation program.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Zebrafish Hox-limb Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 system | Gene editing tool | hox cluster deletion | Targeted mutagenesis of entire genomic regions |

| tbx5a RNA probe | In situ hybridization reagent | Gene expression analysis | Detection of pectoral fin bud initiation marker |

| Alcian blue | Histochemical stain | Cartilage visualization | Staining of endoskeletal disc in larval fins |

| Retinoic acid | Chemical treatment | Signaling pathway analysis | Test competence of LPM to limb-inducing signals |

| Anti-GFP antibody | Immunological reagent | Lineage tracing | Detection of electroporated constructs in chick studies |

| Micro-CT scanner | Imaging equipment | Skeletal analysis | 3D visualization of adult fin skeletal structures |

The genetic evidence from zebrafish hox cluster knockout models provides transformative insights into the fundamental mechanisms controlling appendage positioning along the anterior-posterior axis. The demonstration that hoxba;hoxbb double deletion completely abolishes pectoral fin formation offers the most direct validation to date of the long-standing hypothesis that Hox genes function as master regulators of limb position. These findings establish zebrafish as a powerful model for deciphering the evolutionary and developmental principles of appendage patterning, with broad implications for understanding the Hox code across vertebrate species.

The combinatorial requirement for both hoxba and hoxbb clusters reveals how gene duplication events can distribute essential functions among paralogs, creating robust developmental systems through redundancy. The identification of hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as key regulators, coupled with their action through establishing retinoic acid competence and direct activation of tbx5a, provides a mechanistic framework for future studies of limb development and evolution. These findings open new avenues for research into how alterations in Hox-regulated positioning mechanisms may contribute to evolutionary diversification of appendage morphology across vertebrate lineages.

The development of paired appendages represents a fundamental process in vertebrate evolution, enabling the diversification of locomotion and interaction with the environment across species. Central to this developmental program are Hox genes, which encode transcription factors that orchestrate patterning along the major body axes. In limb development, these genes exhibit a sophisticated temporal regulation that directly influences the formation of distinct limb segments. The concept of "tri-phasic expression" describes the three distinct temporal phases of Hox gene activity that occur during limb bud development, each associated with the specification of a different proximodistal segment of the limb [23] [24]. This evolutionary perspective is crucial when comparing limb development across species, as despite vastly different skeletal organizations—from the fins of teleost fishes to the limbs of tetrapods—the core regulatory mechanisms governing Hox gene expression have remained remarkably conserved [23] [25].

The tri-phasic expression pattern provides a fascinating window into the deep homology between vertebrate appendages. In tetrapods, the three phases correspond to the development of the upper arm (stylopod), forearm (zeugopod), and hand/foot (autopod). Research in zebrafish has revealed that although their fin skeletons are much simpler, they nonetheless exhibit a similar tri-phasic expression of Hox genes, with the third phase correlating with development of the most distal structure—the fin blade [23] [25]. This conservation suggests that the regulatory mechanisms underlying tri-phasic Hox expression were established in a common ancestor of both teleosts and tetrapods, and that teleost fins possess a distal structure potentially comparable to the autopod region of tetrapod limbs [23].

Comparative Analysis of Tri-Phasic Hox Expression Across Species

Phase-Specific Expression Patterns and Functions

Table 1: Comparative Tri-Phasic Hox Expression in Vertebrate Appendages

| Developmental Phase | Tetrapod Limb Association | Zebrafish Fin Association | Key Hox Genes Involved | Regulatory Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Phase | Stylopod (upper arm/thigh) | Proximal fin structures | Hox9-10 genes [23] | Initial establishment of nested domains [24] |

| Second Phase | Zeugopod (forearm/leg) | Intermediate fin structures | Hox9-11 genes [23] | Transition to more complex patterns [24] |

| Third/Distal Phase | Autopod (hand/foot) | Distal fin blade [23] [25] | Hoxa13, Hoxd10-13 [23] [25] | Sonic hedgehog signaling; long-range enhancers (5DOM) [23] [26] |

Evolutionary Conservation of Regulatory Mechanisms

The tri-phasic expression of Hox genes represents a deeply conserved developmental module in vertebrate evolution. Research comparing zebrafish and mouse models reveals that despite approximately 400 million years of evolutionary divergence, both species utilize similar regulatory infrastructures. In both systems, the 3DOM regulatory landscape (located 3' to the HoxD cluster) controls proximal expression (first phase), while the 5DOM landscape (located 5' to the HoxD cluster) governs distal expression (third phase) [26]. This conservation is particularly remarkable given the extensive genomic reorganization that occurred following the teleost-specific whole-genome duplication.

The functional significance of this regulatory conservation is profound. Deletion of the 3DOM region in zebrafish abolishes expression of hoxd4a and hoxd10a in pectoral fin buds, mirroring exactly the effect observed in mouse limb buds when the homologous region is deleted [26]. Similarly, the third phase of Hox expression in both zebrafish fins and mouse limbs depends on Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling and the presence of specific long-range enhancers [23] [24]. This conservation suggests that the tri-phasic regulatory system represents a fundamental developmental "toolkit" for patterning vertebrate paired appendages, which has been maintained despite the radically different skeletal structures that evolved in fish fins versus tetrapod limbs.

Experimental Approaches for Analyzing Tri-Phasic Expression

Key Methodologies for Hox Gene Expression Analysis

The investigation of tri-phasic Hox gene expression employs a diverse array of molecular and genetic techniques, each providing unique insights into the temporal and spatial dynamics of limb patterning.

Table 2: Essential Experimental Protocols for Tri-Phasic Hox Gene Research

| Methodology | Experimental Application | Key Insights Generated | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) | Spatial mapping of Hox gene expression patterns during limb/fin development [26] | Revealed three distinct phases of Hoxa/d gene expression in zebrafish pectoral fins [23] [25] | Requires careful staging of embryos; provides spatial but not quantitative data |

| CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing | Deletion of regulatory landscapes (3DOM, 5DOM) to assess function [26] | Demonstrated conserved function of 3DOM in proximal patterning in both mice and zebrafish [26] | Enables functional testing of evolutionary hypotheses about regulatory conservation |

| Electroporation of dominant-negative constructs | Functional perturbation of specific Hox genes in avian embryos [1] [6] | Identified roles of Hox4/5 as necessary but insufficient for forelimb formation [6] | Allows precise temporal and spatial control of gene perturbation |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Transcriptional trajectory analysis across developmental stages [27] | Revealed global switch from A-P to P-D genetic program between E10.5-E11.5 in mouse [27] | Provides unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity and lineage relationships |

| Chromatin Conformation Capture (4C) | Mapping 3D chromatin architecture at Hox loci [28] | Identified bimodal compartmentalization of active and inactive Hox genes [28] | Links chromatin architecture to gene regulation during temporal colinearity |

Visualization of Tri-Phasic Regulatory Transitions

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental regulatory transitions that occur during the three phases of Hox gene expression in developing limb buds:

Regulatory Transitions During Tri-Phasic Hox Expression

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Limb Development Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant-negative Hox constructs [6] | Functional perturbation of specific Hox genes | Enable dissection of individual Hox gene functions without complete knockout |

| Hoxa13:Cre transgenic mouse line [27] | Lineage tracing and genetic manipulation of distal limb cells | Allows specific targeting of autopod progenitor cells for functional studies |

| Zebrafish hoxda cluster mutants [26] | Evolutionary developmental biology studies | Permit testing of conserved regulatory principles across vertebrate species |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing workflows [27] | Transcriptional trajectory analysis | Provide comprehensive mapping of gene expression dynamics at cellular resolution |

| H3K27ac/H3K27me3 CUT&RUN assays [26] | Epigenetic profiling of regulatory landscapes | Enable characterization of chromatin states associated with different Hox expression phases |

Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying Temporal Dynamics

The temporal dynamics of Hox gene expression during limb development are governed by sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that operate at multiple levels. A key principle is temporal collinearity, where Hox genes are activated sequentially according to their position within the gene cluster, with 3' genes expressed earlier and more anteriorly than 5' genes [28]. This process is facilitated by dynamic changes in chromatin architecture, where initially silent Hox clusters in embryonic stem cells transition through a bivalent chromatin state before establishing a bimodal organization with active and inactive compartments [28].

The transition between expression phases involves a regulatory landscape switch where control shifts from the 3' regulatory domain (3DOM) to the 5' regulatory domain (5DOM) [26] [27]. In both mice and zebrafish, the 3DOM landscape contains enhancers that drive the first phase of Hox gene expression, while the 5DOM landscape controls the third, distal phase of expression [26]. This switch in regulatory control is associated with changes in histone modifications, with active genes marked by H3K4me3 and inactive genes covered by H3K27me3 [28].

The following diagram illustrates the chromatin architecture dynamics that enable phase-specific Hox gene regulation:

Chromatin Architecture Dynamics in Hox Gene Regulation

Implications for Evolutionary Developmental Biology

The conservation of tri-phasic Hox expression between zebrafish fins and tetrapod limbs provides compelling evidence for the deep homology of vertebrate paired appendages. This concept suggests that despite their different morphologies, fish fins and tetrapod limbs share a common developmental regulatory program that was present in their last common ancestor [23] [25]. The functional significance of this conservation is particularly evident in the third phase of expression, where Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 genes pattern the most distal structures in both systems—the fin blade in fish and the autopod in tetrapods [23] [26].

Recent research has revealed an intriguing evolutionary hypothesis: the regulatory landscape controlling distal Hox expression in tetrapod limbs may have been co-opted from a pre-existing program used for cloacal development [26]. This model is supported by the finding that deletion of the 5DOM region in zebrafish affects hoxd13a expression in the cloaca but not in fins, suggesting that the ancestral function of this regulatory landscape was in cloacal development rather than appendage patterning [26]. This represents a fascinating example of evolutionary co-option, where existing genetic regulatory circuits are repurposed for new functions—in this case, the development of novel skeletal structures in tetrapod limbs.

The tri-phasic expression system also demonstrates how heterochrony (changes in developmental timing) can contribute to evolutionary diversity. The timing of Hox gene activation during gastrulation determines the anterior-posterior position of limb formation, and natural variation in this timing correlates with differences in limb positioning across bird species [1]. This mechanism illustrates how modifications to the temporal dynamics of a conserved developmental program can generate morphological diversity without fundamentally altering the core regulatory machinery.

The study of tri-phasic Hox gene expression patterns continues to yield fundamental insights into the principles of developmental biology and evolutionary change. Future research in this field will likely focus on several promising directions, including the comprehensive identification of all regulatory elements within the Hox 3DOM and 5DOM landscapes across multiple species, the mechanistic understanding of how chromatin architecture changes are initiated and maintained during phase transitions, and the exploration of human medical implications, particularly how mutations affecting tri-phasic Hox expression contribute to congenital limb disorders. Additionally, the integration of single-cell multi-omics approaches should provide unprecedented resolution of the molecular events underlying phase transitions, potentially revealing novel regulatory mechanisms that could inform therapeutic strategies for limb regeneration and repair.

Hox gene collinearity represents one of the most fundamental principles in developmental biology, describing the remarkable correlation between the genomic organization of Hox genes and their spatial-temporal expression patterns during embryogenesis. This phenomenon, first discovered in Drosophila, manifests as an ordered sequence of gene activation along the chromosome that corresponds precisely to patterned expression along the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo [29] [30]. In vertebrate limb development, this principle has been co-opted to orchestrate the intricate patterning of musculoskeletal structures, serving as a critical mechanism for translating positional information into morphological complexity [14]. The collinearity paradigm operates through multiple dimensions: spatial collinearity, where gene order corresponds to expression domains along the body axis; temporal collinearity, where genes are activated sequentially in time according to their chromosomal position; and quantitative collinearity, where expression levels follow a predictable gradient based on gene order [29] [31].

The vertebrate limb has emerged as an powerful model system for investigating Hox collinearity mechanisms, particularly because it exhibits two distinct phases of Hox gene regulation—an early phase controlling proximal limb structures (stylopod and zeugopod) and a late phase patterning distal elements (autopod) [32] [14]. During early limb bud formation, Hoxd genes are transcribed in a collinear manner that mirrors their organization along the chromosome, with 3' genes expressed earlier and more anteriorly than their 5' counterparts [32]. This review systematically compares the dominant models explaining Hox collinearity, presents experimental evidence from cross-species analyses, and provides methodological guidance for investigating these mechanisms in limb positioning research.

Comparative Models of Hox Collinearity

The Two-Phases Molecular Model

The two-phases model, supported by extensive genetic engineering experiments in mice, proposes that Hox gene collinearity emerges from sequential chromatin opening combined with regulatory elements located outside the Hox cluster [29]. This model identifies distinct regulatory phases during vertebrate limb development: an early wave that controls growth and polarity up to the forearm, and a late wave that specifically patterns the digits [32]. According to this framework, gene activation is regulated sequentially from the telomeric side (3') of the Hoxd cluster, balanced by repressive influences from the centromeric region [29]. In the developing limb, a telomeric active site (ELCR - early limb control regulation) provides positive activation that is counterbalanced by centromeric repressive influences (POST), with the combination of these forces producing sequential chromatin opening and the characteristic overlapping expression patterns along the anterior-posterior axis [29].

The molecular machinery underpinning this model involves enhancers, inhibitors, promoters, and other regulatory molecules that collectively control the precise spatiotemporal activation of Hox genes [29]. This model effectively explains the biphasic expression patterns observed in Hoxa and Hoxd clusters during limb development, where early phase regulation resembles the collinear strategy implemented in trunk development, while late phase regulation appears to have evolved separately after cluster duplication events [14]. The two-phases model extends to both early and late developmental stages, aiming to provide a comprehensive explanation of Hox-mediated patterning throughout limb morphogenesis [29].

The Biophysical Model

In contrast to molecular-focused explanations, the biophysical model proposes that physical forces generated within the cell nucleus drive Hox collinearity through mechanical effects on chromatin organization [29] [30]. According to this model, spatial and temporal signals from the multicellular tissue are transduced to the genetic domain, where physical forces decondense and pull the chromatin fiber from inside the chromosome territory toward transcription factories located in the interchromosome domain [29]. This process is conceptually analogous to the elastic expansion of a spring, with genes being sequentially pulled toward activation zones as physical forces increase along the cluster [30] [31].

The biophysical model introduces a heuristic formulation where pulling force (F) results from the product of negative charges (N) associated with the DNA backbone and positive charges (P) deposited in the nuclear environment (F = N*P) [30] [31]. As morphogen gradients establish positional information across the developing limb bud, differential distribution of these hypothetical P-molecules generates graded physical forces that sequentially extract Hox genes from their inactive chromatin territory, with 3' genes experiencing weaker forces and activating earlier than 5' genes subjected to stronger forces [31]. This model naturally explains quantitative collinearity through the physical proximity of genes to transcription factories, where closer association enables stronger expression [29] [31].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Collinearity Models

| Feature | Two-Phases Model | Biophysical Model |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Sequential chromatin opening balanced by enhancer/repressor elements | Physical forces pulling chromatin toward transcription factories |

| Primary Mechanism | Molecular regulation (enhancers, inhibitors, promoters) | Force-mediated chromatin decondensation and translocation |

| Explanatory Scope | Early and late developmental phases | Primarily early developmental phase |

| Scale Integration | Functions primarily at DNA (microscopic) level | Explicitly multiscale: macroscopic embryonic signals to microscopic nuclear forces |

| Supporting Evidence | Genetic engineering experiments showing regulatory landscapes | Observed Hox cluster elongation and gene translocation during activation |

| Quantitative Collinearity | Requires additional assumptions | Natural explanation via proximity to transcription factories |

Model Predictions and Experimental Differentiation

The two models generate distinct, testable predictions that enable experimental differentiation. The two-phases model anticipates that deletion of specific regulatory elements outside the Hox cluster will disrupt collinear expression without necessarily affecting chromatin structure globally [29]. In contrast, the biophysical model predicts that physical perturbations affecting nuclear mechanics or force generation should compromise collinear expression patterns [30] [31]. Crucially, the biophysical model uniquely predicts the physical translocation of Hox genes from chromosome territories to transcription factories during activation—a phenomenon that has received experimental support [31].

Recent evolutionary arguments also differentiate these models. The biophysical model suggests that tighter Hox cluster organization in vertebrates (compared to invertebrates) enables more efficient force generation and more emphatic collinearity—a prediction supported by stochastic modeling showing that compact clusters produce more robust patterning against molecular noise [31]. This evolutionary constraint toward cluster consolidation presents a challenge for purely molecular models that don't explicitly account for the mechanical advantages of specific genomic architectures.

Experimental Analysis of Collinearity Mechanisms

Key Methodologies for Investigating Collinearity

The experimental investigation of Hox collinearity employs sophisticated genetic, molecular, and imaging approaches to manipulate and visualize gene expression dynamics. Loss-of-function studies using targeted gene deletions in mice have revealed the essential roles of specific Hox paralog groups in limb patterning, with Hox10 paralogs required for stylopod formation, Hox11 for zeugopod patterning, and Hox13 for autopod development [9]. Complementarily, gain-of-function approaches through misexpression in chick embryos have demonstrated the instructive roles of Hox genes in establishing positional identity [6] [14].

Advanced imaging and sequencing technologies have revolutionized our ability to document collinear expression patterns. Single-cell RNA sequencing combined with spatial transcriptomics has enabled high-resolution mapping of HOX gene expression along the rostrocaudal axis in human fetal development, revealing previously unappreciated complexities in collinear regulation [2]. These approaches can delineate the inherent rostrocaudal maturation gradient in the fetal spine—a temporal maturation difference of approximately 6 hours between each vertebral level during development [2]. Additionally, live imaging of chromatin dynamics has provided direct evidence for the physical translocation of Hox genes during activation, offering critical support for biophysical mechanisms [31].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Applications

| Research Reagent | Experimental Application | Key Function in Collinearity Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxb1/lacZ transgene | Transposition experiments | Reports expression patterns when relocated within Hox clusters |

| Dominant-negative Hox constructs | Loss-of-function studies | Suppresses signaling of target Hox genes while preserving co-factor binding |

| CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Cluster engineering | Creates targeted deletions, duplications, and inversions in Hox clusters |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Expression profiling | Maps Hox expression patterns at cellular resolution across developmental time |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Tissue context mapping | Correlates Hox expression with anatomical position in developing limbs |

| Fluorescence in situ hybridization | Nuclear localization | Visualizes Hox cluster organization and position relative to transcription factories |

Experimental Evidence Informing Model Selection

Genetic engineering experiments producing unexpected results have been particularly informative for evaluating collinearity models. When an anterior Hoxb1/lacZ transgene was inserted at the posterior end of the HoxD cluster, its expression in the fourth rhombomere was completely abolished, yet early mesodermal expression was unexpectedly preserved [33]. This tissue-specific differential regulation challenges simple silencing models but can be explained by the biophysical model through differential force implementation across tissues [33] [31].

Similarly, inversion experiments that separate the centromeric neighborhood from the Hoxd cluster produce significant alterations in Hoxd expression during early embryogenesis [29]. The two-phases model attributes these changes to disruption of a regulatory "landscape effect," while the biophysical model interprets them as evidence for the importance of physical cluster fastening—analogous to securing one end of a spring being pulled [29] [30]. The observed elongation of Hox clusters during activation—up to five times their inactive length—provides additional support for physical force applications [30] [31].

Signaling Pathways and Gene Regulatory Networks

The implementation of Hox collinearity in limb development occurs within complex signaling networks that integrate positional information from multiple patterning systems. A core regulatory circuit governing limb initiation involves Tbx5 and Tbx4 transcription factors that directly activate Fgf10 expression in the forelimb and hindlimb fields respectively [8]. This triggers a critical feedback loop where Fgf10 induces Fgf8 expression in the overlying ectoderm, forming the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), which reciprocally maintains Fgf10 expression in the mesoderm to drive continued limb outgrowth [8].

Hox genes interface with this core network by providing positional information that restricts limb formation to appropriate axial levels. Studies in chick embryos demonstrate that Hox4/5 genes provide permissive signals for forelimb formation throughout the neck region, while Hox6/7 genes deliver instructive cues that determine the final forelimb position in the lateral plate mesoderm [6]. This combinatorial Hox code ultimately converges on Tbx5 activation, which initiates the forelimb developmental program [6]. The positioning function of Hox genes is further refined through interactions with Shh signaling, where Hox5 paralogs restrict Shh expression to the posterior limb bud by interacting with Plzf, while Hox9 genes promote posterior Hand2 expression to inhibit the hedgehog pathway inhibitor Gli3, thereby permitting Shh induction [9].

Diagram 1: Hox Gene Integration in Limb Positioning Network. Hox genes provide positional inputs to limb patterning networks, with Hox4/5 providing permissive and Hox6/7 providing instructive signals for Tbx5 activation. This core circuit engages FGF feedback loops and modulates Shh signaling through intermediate factors.

Cross-Species Analysis of Limb Positioning Codes

Comparative studies across vertebrate species reveal both conserved principles and species-specific adaptations in Hox-mediated limb positioning. The fundamental rule that limbs consistently emerge at the cervical-thoracic boundary despite variation in vertebral number highlights the deep conservation of Hox positional codes [6]. However, the specific implementation of these codes demonstrates notable evolutionary flexibility, with modifications in Hox expression domains contributing to species-specific adaptations in limb position and morphology.

In avian embryos, the functional dissection of Hox codes has revealed that neck lateral plate mesoderm can be reprogrammed to form ectopic limb buds when provided with appropriate Hox inputs, demonstrating the instructive capacity of Hox patterning [6]. Mammalian models show similar principles but with distinct regulatory nuances; while Tbx5 is absolutely required for forelimb initiation in mice, Tbx4 appears necessary for hindlimb outgrowth but not initial specification, suggesting the existence of compensatory mechanisms in hindlimb positioning [8]. These species-specific variations highlight both the modular nature of limb positioning networks and the evolutionary flexibility of Hox regulatory implementation.

Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses of human fetal development have uncovered unexpected complexities in Hox code implementation, particularly in neural crest derivatives that retain the anatomical Hox code of their origin while additionally adopting the code of their destination [2]. This dual coding strategy may represent an important mechanism for ensuring proper connectivity between peripheral nervous system components and their central and peripheral targets—a finding with significant implications for understanding the coordination of musculoskeletal and nervous system development.

The investigation of Hox gene collinearity has evolved from initial descriptive observations to sophisticated mechanistic dissection of the underlying principles. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that both molecular and biophysical models contribute valuable insights, with the two-phases model effectively explaining regulatory complexity and the biophysical model providing a compelling mechanism for cross-scale integration. Rather than representing mutually exclusive explanations, these frameworks likely describe complementary aspects of a unified collinearity mechanism where physical forces operate through molecular intermediaries to achieve precise spatiotemporal patterning.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding Hox collinearity mechanisms has practical implications beyond fundamental developmental biology. The precise control of positional identity has relevance for regenerative medicine approaches aiming to reconstruct patterned structures, and for understanding the pathogenesis of congenital limb malformations. Additionally, the principles of collinear regulation may inform therapeutic strategies for manipulating pattern formation in tissue engineering contexts. As single-cell technologies continue to enhance our resolution for observing these processes in human development, and genome engineering approaches enable more precise functional testing, our understanding of Hox collinearity will continue to refine, offering new insights into one of developmental biology's most fascinating phenomena.

Decoding the Hox Toolkit: Modern Methods for Expression and Functional Analysis

The emergence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized functional genetics, enabling systematic dissection of gene cluster functions across model organisms. This review comprehensively compares CRISPR-Cas9 methodologies and findings from targeted Hox cluster deletions in zebrafish and mice, highlighting conserved principles and species-specific adaptations in limb positioning. We synthesize experimental evidence demonstrating how cluster-wide deletions have revealed both functional redundancy and specialization within Hox gene networks, advancing our understanding of evolutionary developmental biology and providing insights for biomedical research.

Hox genes, encoding evolutionarily conserved homeodomain-containing transcription factors, provide positional information along the anterior-posterior axis in bilaterian animals [20]. These genes are characterized by their genomic organization into clusters and a phenomenon known as collinearity, where their order within clusters correlates with expression patterns along embryonic axes [34]. In vertebrates, Hox clusters have undergone duplication events, resulting in four major clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) in tetrapods, while teleost fishes like zebrafish possess additional clusters due to teleost-specific whole-genome duplication [20] [35].

A fundamental question in developmental biology concerns how paired appendages, including limbs in tetrapods and fins in fish, are positioned at specific locations along the body axis. Hox genes have long been hypothesized to regulate this limb positioning, supported by correlative evidence from expression studies [1]. However, functional validation remained limited until the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 enabled systematic deletion of entire Hox clusters, revealing unexpected functional redundancies and species-specific requirements.

CRISPR-Cas9 Methodology for Hox Cluster Deletions

Fundamental Principles of CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Engineering

The CRISPR-Cas9 system represents a transformative genome editing tool derived from bacterial adaptive immune systems. The system consists of the Cas9 endonuclease and two RNA molecules (crRNA and tracRNA) that can be engineered as a single guide RNA (sgRNA) [36]. This ribonucleoprotein complex recognizes specific genomic sequences through complementary base pairing between the 20-nucleotide spacer domain of the sgRNA and the target DNA, adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [36].

Upon binding, Cas9 generates double-strand breaks (DSBs) at targeted sites, which are subsequently repaired by endogenous cellular mechanisms. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, while homology-directed repair (HDR) can facilitate precise genome engineering when a repair template is supplied [36]. The efficiency, specificity, and programmability of CRISPR-Cas9 have made it particularly valuable for targeting gene clusters and regulatory elements in model organisms.

Experimental Workflow for Cluster Deletion

The general workflow for Hox cluster deletion involves several key stages, visualized below:

Target Selection and sgRNA Design: Multiple sgRNAs are designed to flank the entire Hox cluster, targeting regions upstream and downstream of the cluster to facilitate large deletions. Bioinformatic tools like the Genetic Perturbation Platform (GPP) designer are employed to optimize sgRNA efficiency and minimize off-target effects [37].

sgRNA Synthesis: DNA oligomers encoding sgRNA sequences are purchased and used as templates for in vitro transcription with commercially available reagents, followed by purification [36].

Microinjection: Purified sgRNAs and Cas9 mRNA or protein are co-injected into single-cell embryos. In zebrafish, this is typically performed at the one-cell stage [36] [20], while in mice, injections target fertilized eggs.

Genotype Validation: Successful deletion mutants are identified through PCR screening and sequencing, assessing both the presence of large deletions and potential off-target effects.

Phenotypic Analysis: Founders (F0) are raised and outcrossed to establish stable lines. Subsequent generations are analyzed for morphological and molecular phenotypes using techniques including whole-mount in situ hybridization, skeletal preparations, and transcriptomic approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Cluster Deletions

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 mRNA/Protein | RNA-guided endonuclease that creates DSBs | Zebrafish: In vitro transcribed mRNA [36] [20] |

| sgRNA Templates | DNA oligomers specifying target sequence | Custom-designed oligonucleotides for Hox clusters [36] [37] |

| In Vitro Transcription Kits | sgRNA synthesis | Commercial kits (e.g., Ambion MEGAshortscript) [36] |

| Microinjection Apparatus | Precise delivery into embryos | Pneumatic picopump and micromanipulators [36] |

| Genotyping Primers | PCR amplification of target loci | Flanking primers to detect large deletions [20] [35] |

| Online sgRNA Design Tools | Prediction of efficient sgRNAs | GPP Web Portal [37] |

Comparative Analysis of Hox Cluster Functions

Zebrafish Hox Cluster Organization

Zebrafish possess seven hox clusters resulting from teleost-specific whole-genome duplication: hoxaa, hoxab (derived from HoxA), hoxba, hoxbb (derived from HoxB), hoxca, hoxcb (derived from HoxC), and hoxda (derived from HoxD, with hoxdb largely lost) [20] [35]. This expanded repertoire complicates functional analysis but provides unique opportunities to study subfunctionalization and redundancy.

Phenotypic Outcomes of Cluster Deletions

Table 2: Comparative Phenotypes of Hox Cluster Deletions in Zebrafish and Mice

| Organism | Targeted Clusters | Phenotypic Outcome | Molecular Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | hoxba;hoxbb (double homozygous) | Complete absence of pectoral fins (100% penetrance) [20] [34] | Loss of tbx5a expression in lateral plate mesoderm [20] |

| Zebrafish | hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda (triple homozygous) | Severely shortened pectoral fins [35] | Normal tbx5a induction; reduced shha expression [35] |

| Mouse | HoxA;HoxD (double cluster deletion) | Severe truncation of distal limb elements [35] | Not specified in available results |

| Mouse | CTCF boundary elements at Hox clusters | Derepression of posterior Hox genes; homeotic transformations [38] | Disrupted TAD boundaries; altered chromatin architecture [38] |

Limb Positioning Versus Limb Patterning

The comparative analysis reveals a fundamental distinction in Hox gene functions: HoxB-derived clusters (hoxba/hoxbb) primarily determine limb position along the anterior-posterior axis, while HoxA- and HoxD-derived clusters predominantly regulate subsequent limb patterning and outgrowth.

In zebrafish, hoxba;hoxbb double homozygous mutants display complete absence of pectoral fins due to failed induction of tbx5a expression in the lateral plate mesoderm, indicating these clusters specify where fins initiate [20]. Conversely, hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda triple mutants establish fin buds with normal tbx5a expression but display severe shortening due to reduced shha expression and impaired outgrowth [35], demonstrating their role in patterning established buds.

This functional specialization is conserved in mice, where HoxA and HoxD cluster genes control proximal-distal patterning of limb elements [35], while HoxB and HoxC genes influence limb position, albeit with less severe phenotypes than in zebrafish [1].

Signaling Pathways in Hox-Mediated Limb Development

The molecular mechanisms through which Hox clusters regulate limb development involve complex signaling networks and chromatin architecture:

Chromatin Architecture and Hox Regulation

Recent research has illuminated the critical role of three-dimensional genome organization in Hox gene regulation. CTCF-mediated topologically associating domains (TADs) insulate active and repressed chromatin regions within Hox clusters [37] [38]. At Hox clusters, CTCF collaborates with cofactors like MAZ (Myc-associated zinc-finger protein) to establish chromatin boundaries that ensure proper temporal and spatial Hox expression during development [38].

Disruption of these boundaries through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of CTCF binding sites leads to derepression of posterior Hox genes and homeotic transformations in mice [38], demonstrating how chromatin architecture contributes to Hox gene function in limb development.

Retinoic Acid Signaling Competence

The competence of cells to respond to retinoic acid represents another layer of Hox-mediated regulation in limb positioning. In zebrafish hoxba;hoxbb cluster mutants, the lateral plate mesoderm loses its ability to respond to retinoic acid signaling, providing a mechanistic explanation for failed tbx5a induction despite normal retinoic acid availability [20].

Discussion: Evolutionary and Developmental Implications

Functional Redundancy and Robustness

The differential phenotypic severity observed in various Hox cluster deletion combinations highlights the principle of functional redundancy in developmental systems. In zebrafish, the requirement for simultaneous deletion of both hoxba and hoxbb clusters to eliminate pectoral fins demonstrates redundant functions between these duplicated clusters [20]. Similarly, the graded severity of pectoral fin defects in hoxaa/hoxab/hoxda multiple mutants reveals overlapping functions with quantitatively different contributions, where hoxab cluster has the strongest effect, followed by hoxda and then hoxaa clusters [35].

This redundancy provides developmental robustness, ensuring critical structures form reliably despite genetic or environmental perturbations. From an evolutionary perspective, duplicated clusters can acquire specialized functions (subfunctionalization) while retaining backup capacity, facilitating evolutionary innovation without compromising essential functions.

Comparative Regulatory Strategies

The comparison between zebrafish and mice reveals both conserved principles and species-specific adaptations in Hox gene regulation. The bimodal regulatory mechanism described at the mouse HoxD locus, where genes are regulated by alternating telomeric (T-DOM) and centromeric (C-DOM) regulatory domains, appears generally conserved in chicken but with modifications in timing and boundary width [39]. These subtle regulatory differences may contribute to species-specific limb morphologies.

Interestingly, while mouse studies historically struggled to demonstrate severe limb positioning defects in Hox mutants, the zebrafish model has provided clear genetic evidence due to its expanded Hox repertoire and possibly reduced compensatory capacity in specific developmental contexts. This highlights how comparative approaches across model organisms can reveal fundamental principles obscured in single-species studies.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated cluster deletions have transformed our understanding of Hox gene function in vertebrate limb development. The comparative analysis between zebrafish and mice reveals both deeply conserved genetic principles and species-specific adaptations, highlighting how functional redundancy and regulatory specialization have evolved following genome duplication events.

These findings have broader implications for understanding the genetic basis of evolutionary morphological diversity and for biomedical applications, particularly in congenital limb abnormalities and regenerative medicine. Future research leveraging increasingly sophisticated genome engineering approaches will continue to unravel the complex regulatory networks governing body patterning across species.

Hox genes, a highly conserved family of transcription factors, function as master regulators of positional identity along the anterior-posterior axis during embryonic development. Their expression not only determines the "Bauplan" of the embryo but also persists into adulthood, where it continues to influence cell fate decisions in various stem and progenitor cell populations. The emergence of sophisticated genomic technologies has enabled researchers to move beyond merely cataloging Hox gene expression to understanding the complex regulatory networks they govern. This guide examines how the integrated application of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and the Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) provides a powerful framework for deciphering the transcriptomic and epigenomic landscapes of Hox-positive cells. Within limb positioning research, cross-species comparative approaches leveraging these technologies have been instrumental in unraveling how Hox gene expression determines anatomical specificity, offering insights with broad implications for developmental biology, evolutionary studies, and regenerative medicine.

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq)

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics that uses deep-sequencing technologies to profile the complete set of transcripts in a cell, known as the transcriptome [40]. This method involves converting a population of RNA into a library of cDNA fragments with adaptors attached to one or both ends, followed by high-throughput sequencing to obtain short sequences [40]. Unlike hybridization-based approaches like microarrays, RNA-seq does not rely on existing genomic knowledge, has very low background signal, and offers a dramatically larger dynamic range for quantifying expression levels—spanning over 9,000-fold in some studies compared to a few hundredfold for microarrays [40]. This sensitivity makes it particularly valuable for detecting both known and novel features in a single assay, including transcript isoforms, gene fusions, and single nucleotide variants without the limitation of prior knowledge [41].

Table 1: Key Advantages of RNA-Seq over Microarray Technology

| Feature | Tiling Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Hybridization | High-throughput sequencing |