HoxA vs. HoxD in Limb Patterning: Functional Divergence, Regulatory Synergy, and Clinical Implications

This review synthesizes current research on the distinct and overlapping functions of the HoxA and HoxD gene clusters in vertebrate limb development.

HoxA vs. HoxD in Limb Patterning: Functional Divergence, Regulatory Synergy, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This review synthesizes current research on the distinct and overlapping functions of the HoxA and HoxD gene clusters in vertebrate limb development. While both clusters are essential for patterning the proximal-distal axis, with paralogous genes 9-13 playing critical cooperative roles, they also exhibit unique functional specializations. The HoxD cluster operates at a dynamic topological associating domain (TAD) boundary, enabling its sequential regulation by separate enhancer landscapes for stylopod/zeugopod versus autopod development. In contrast, the HoxA cluster is crucial for integrating the entire musculoskeletal system, patterning muscles and tendons in addition to the skeleton. We explore methodological advances from zebrafish and mouse models that reveal this functional redundancy and specialization, discuss the pathological consequences of cluster dysregulation, and highlight emerging implications for understanding congenital limb malformations and evolutionary morphology. This comparative analysis provides a framework for future research into the mechanistic basis of Hox-driven patterning and its translational potential.

Core Principles: Unraveling the Distinct and Overlapping Roles of HoxA and HoxD

Evolutionary Conservation and Genomic Architecture of Hox Clusters

The Hox gene family, encoding master regulatory transcription factors, plays an indispensable role in determining positional identity along the anterior-posterior body axis in bilaterian animals. Of particular interest in evolutionary and developmental biology is the conserved function of specific Hox clusters in the patterning of paired appendages. Among the four main Hox clusters (A, B, C, and D), HoxA and HoxD have been co-opted in vertebrates to orchestrate the development of fins and limbs [1]. While both clusters contribute to proximal-distal patterning, they exhibit distinct yet complementary regulatory strategies and functional specializations. This guide provides a systematic comparison of HoxA versus HoxD cluster functions in limb patterning research, synthesizing current experimental evidence from multiple model organisms to highlight conserved principles, key differences, and relevant methodological approaches for researchers investigating the genetic basis of morphological evolution and potential therapeutic targets for congenital limb disorders.

Comparative Genomic Architecture and Evolutionary History

The HoxA and HoxD clusters share a common evolutionary origin from ancestral Hox cluster duplication events but have subsequently diverged in their genomic organization and regulatory landscapes. Understanding these architectural differences is crucial for interpreting their distinct functional contributions to limb development.

Table 1: Comparative Genomic Architecture of HoxA and HoxD Clusters Across Vertebrates

| Feature | HoxA Cluster | HoxD Cluster | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Size in Humans | 110 kb [2] | ~100-110 kb [3] | Constrained size despite functional divergence |

| Teleost Counterparts | hoxaa, hoxab (zebrafish) [4] | hoxda (zebrafish; hoxdb largely lost) [4] | Differential retention after teleost-specific genome duplication |

| Regulatory Landscapes | Shared 5' regulatory architecture with HoxD [1] | Bimodal regulation: T-DOM (telomeric) and C-DOM (centromeric) [5] | Independent regulatory modules enable specialized expression |

| Conserved Non-coding Elements | Regulatory elements show anterior-posterior conservation gradient [2] | Ultraconserved digit enhancers (e.g., GCR, Prox) [6] | Preservation of crucial regulatory capacity across vertebrates |

| Chromatin State Dynamics | Similar conformational properties to HoxD [1] | A-P differences in H3K27me3 and chromatin compaction [6] | Epigenetic regulation of collinear expression patterns |

The evolutionary trajectory of Hox clusters reveals significant events that have shaped their current functions. Following two rounds of whole-genome duplication in early vertebrates, the four Hox clusters (A, B, C, and D) emerged, with HoxA and HoxD subsequently being recruited for appendage patterning [4]. Zebrafish, as a teleost fish, experienced an additional teleost-specific whole-genome duplication, resulting in seven hox clusters, including duplicates of HoxA (hoxaa and hoxab) while largely retaining a single HoxD cluster (hoxda) [4] [7]. This differential retention suggests distinct evolutionary constraints on these clusters, with HoxD potentially being more dosage-sensitive or functionally constrained than HoxA in the context of fin/limb development.

Functional Specialization in Limb Patterning: A Comparative Analysis

While both HoxA and HoxD clusters play essential roles in limb development, they exhibit distinct temporal and spatial expression patterns and contribute differently to specific aspects of limb morphology. The functional specialization of these clusters represents a fascinating example of subfunctionalization following gene duplication.

HoxD Cluster: Bimodal Regulation and Distal Patterning

The HoxD cluster operates under a sophisticated bimodal regulatory mechanism that governs its expression in developing limbs [3] [5]. During early limb development, 3' Hoxd genes (Hoxd1-Hoxd9) are activated by enhancers located in the telomeric regulatory domain (T-DOM), patterning proximal structures including the stylopod (upper arm) and zeugopod (forearm) [5]. Subsequently, a regulatory switch occurs, and 5' Hoxd genes (Hoxd9-Hoxd13) come under the control of the centromeric regulatory domain (C-DOM), driving expression in the distal autopod (hand/foot) [3]. This transition creates a domain of low Hoxd expression where both regulatory domains are silent, giving rise to the wrist and ankle articulations [5].

A defining feature of HoxD regulation in distal limb structures is the distal phase (DP) expression pattern, characterized by "reverse collinearity" where the most 5' gene (Hoxd13) is expressed in a broader domain than its 3' neighbors [1]. This pattern, regulated by enhancers in the C-DOM, results in Hoxd13 expression across all five digits while Hoxd12 is restricted to digits 2-5, contributing to the specification of the thumb [1]. Single-cell transcriptomics has revealed unexpected heterogeneity in this system, with distinct combinations of Hoxd genes expressed in individual limb bud cells, suggesting complex cell-type specific regulation [8].

HoxA Cluster: Complementary Functions and Emerging Roles

The HoxA cluster works in concert with HoxD but exhibits its own distinct expression dynamics and functional contributions. In zebrafish, the combined function of hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters is essential for normal pectoral fin development, with hoxab cluster making the highest contribution, followed by hoxda and then hoxaa clusters [4]. Simultaneous deletion of all three clusters results in severely shortened pectoral fins, with defects in both the endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [4].

While initially thought to be HoxD-specific, the distal phase expression pattern has also been observed for posterior HoxA genes in various vertebrate structures, suggesting this regulatory module is an ancient feature of both clusters [1]. This DP expression of HoxA genes occurs not only in paired fins and limbs but also in diverse body plan features such as paddlefish barbels and the vent, indicating this genetic program has been co-opted multiple times during vertebrate evolution [1].

Table 2: Functional Comparison of HoxA and HoxD Clusters in Limb Patterning

| Functional Aspect | HoxA Cluster | HoxD Cluster | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal Limb Patterning | Required for stylopod and zeugopod development | Required for stylopod and zeugopod development | Mouse knockout phenotypes [4] |

| Distal Limb/Autopod Patterning | Critical for autopod formation; shows DP expression in various structures | Essential for digit patterning with characteristic DP expression | Compound mutant analysis [9] [1] |

| Regulatory Mechanism | Shared 5' regulatory landscape with HoxD | Bimodal regulation via T-DOM and C-DOM | Chromatin conformation studies [1] [5] |

| Functional Redundancy | High between duplicates in zebrafish (hoxaa/hoxab) | Less redundant; single hoxda cluster in zebrafish | Zebrafish cluster deletion mutants [4] |

| Expression Dynamics | Collinear expression with posterior prevalence | Bimodal collinearity with distal phase switch | Spatiotemporal expression analyses [4] [1] |

Cooperative Interactions and Genetic Hierarchy

HoxA and HoxD clusters do not function in isolation but engage in complex genetic interactions that ensure proper limb patterning. In mice, simultaneous deletion of HoxA and HoxD clusters leads to more severe limb truncations than individual cluster deletions, demonstrating their cooperative function [4]. Similarly, in zebrafish, the most severe pectoral fin defects are observed only when both HoxA-derived (hoxaa and hoxab) and HoxD-derived (hoxda) clusters are deleted [4].

At the molecular level, Hox13 proteins from both clusters play particularly crucial roles in autopod development. Mouse mutants lacking both Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 show dramatically more severe defects than either single mutant, including an almost complete absence of chondrified condensations in the autopods [9]. These genes act in a partially redundant manner, with double heterozygous mutants already showing abnormal autopodal phenotypes, suggesting that quantitative homeoprotein levels are critical for proper digit patterning [9].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

The complex functions of HoxA and HoxD clusters have been elucidated through sophisticated genetic, genomic, and imaging approaches. Understanding these methodologies is essential for designing future experiments and interpreting existing data.

Genetic Manipulation Strategies

Cluster-wide deletions using CRISPR-Cas9 have been particularly informative for understanding functional redundancy and compensation among Hox genes. In zebrafish, systematic deletion of individual hox clusters has revealed that while single cluster deletions often produce mild phenotypes, combined deletions uncover essential redundant functions [4] [7]. For example, only simultaneous deletion of hoxba and hoxbb clusters results in complete absence of pectoral fins, demonstrating functional redundancy between these duplicates [7].

Compound mutants with various combinations of Hox gene mutations have been instrumental in deciphering genetic interactions. The analysis of mice with all possible combinations of disrupted Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 alleles revealed that these genes act partially redundantly, with double homozygous mutants showing dramatically enhanced phenotypes compared to single mutants [9].

Molecular Characterization Techniques

Chromatin conformation capture methods have been crucial for elucidating the bimodal regulatory mechanism of the HoxD cluster. These approaches have revealed that the cluster is flanked by two topologically associating domains (TADs) - the telomeric T-DOM and centromeric C-DOM - that sequentially interact with different parts of the cluster during limb development [5].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has provided unprecedented resolution of Hox gene expression heterogeneity. Contrary to population-level analyses suggesting homogeneous expression, single-cell transcriptomics has revealed that Hoxd genes are expressed in specific combinations in individual limb bud cells, with only a minority of cells co-expressing both Hoxd11 and Hoxd13 despite their shared regulatory landscape [8].

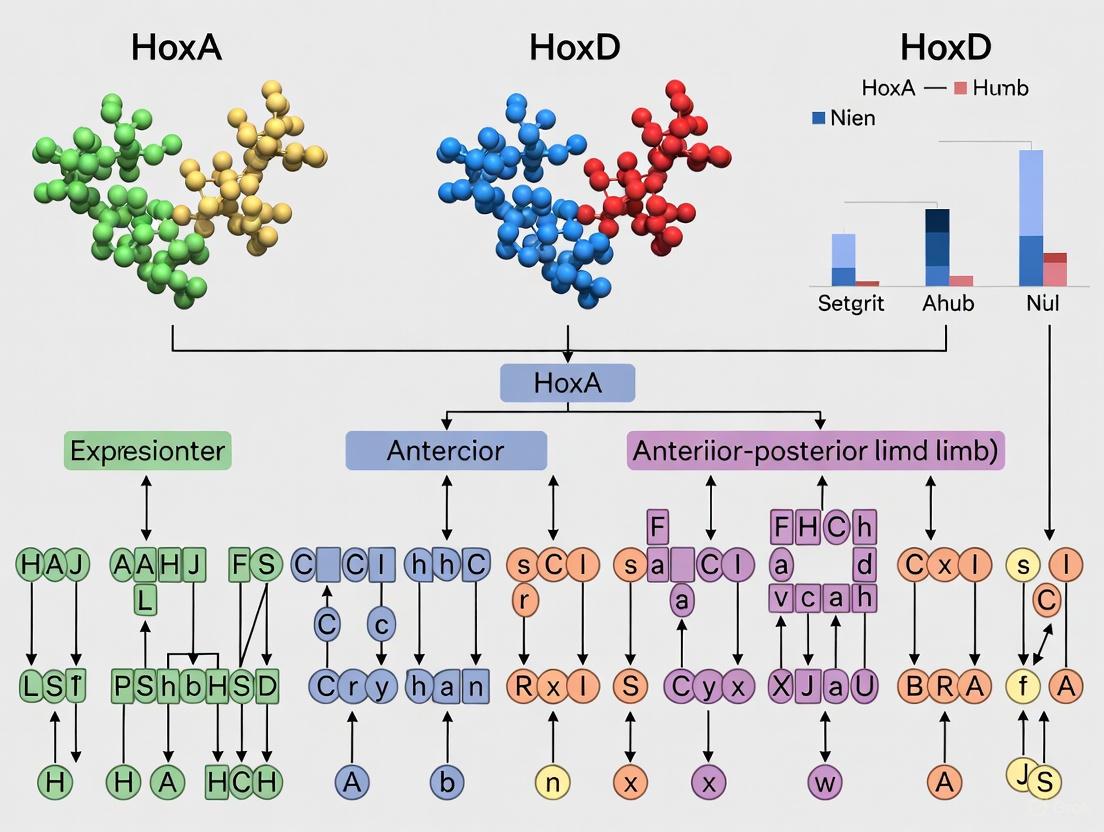

Figure 1: Bimodal Regulatory Mechanism of HoxD Cluster in Limb Development. The HoxD cluster is sequentially regulated by two distinct topological associating domains (TADs) - telomeric (T-DOM) and centromeric (C-DOM) - that drive expression in proximal and distal limb domains, respectively. A HOX13-mediated regulatory switch facilitates the transition between these phases [3] [5].

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Advancing our understanding of Hox cluster functions requires specialized research tools and reagents. The following table summarizes key resources used in the field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Cluster and Limb Patterning Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Research Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish hox cluster mutants | CRISPR-Cas9 generated deletions of individual or multiple hox clusters | Functional redundancy analysis; pectoral fin development studies | [4] [7] |

| Hoxd11::GFP reporter mice | GFP knocked into Hoxd11 locus | Tracking Hoxd11 expression at single-cell level; FACS enrichment | [8] |

| H3K27me3-specific antibodies | Histone modification markers for Polycomb-repressed chromatin | ChIP assays to study epigenetic regulation of Hox clusters | [6] |

| RNA-FISH probes | Hox gene-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization probes | Single-cell resolution of Hox gene expression patterns | [8] |

| Custom tiling arrays | High-resolution microarray for chromatin immunoprecipitation | Genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and enhancer elements | [6] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq protocols | Fluidigm C1 platform for capturing transcriptomes | Identifying heterogeneous Hox gene expression in limb buds | [8] |

Evolutionary Perspectives and Comparative Insights

The comparison between HoxA and HoxD clusters extends beyond their functions in model organisms to reveal fundamental principles of evolutionary developmental biology. Both clusters exhibit deep evolutionary conservation in their limb patterning functions, with similar mechanisms operating across jawed vertebrates.

The distal phase expression pattern, once considered a tetrapod novelty, has been documented in the pectoral fins of basal ray-finned fishes like paddlefish and cartilaginous fishes like catsharks, indicating this regulatory module predates the origin of limbs [1]. Furthermore, the discovery that HoxA genes also exhibit DP expression in various vertebrate structures suggests this is an ancient feature of both clusters that has been co-opted multiple times during vertebrate evolution [1].

Comparative studies between mouse and chicken reveal that while the bimodal regulatory mechanism of HoxD is largely conserved, species-specific modifications exist. In chicken hindlimbs, the duration of T-DOM regulation is shortened compared to forelimbs, correlating with morphological differences between wings and legs [5]. Such regulatory variations highlight how modifications of conserved genetic programs can contribute to morphological diversity.

HoxA and HoxD clusters represent a fascinating case of paralogous gene clusters that have maintained complementary yet distinct functions in vertebrate limb patterning. While both clusters contribute to proximal-distal patterning, HoxD has evolved a more elaborate bimodal regulatory mechanism that enables its sequential deployment in proximal and distal limb domains. HoxA, while sharing some regulatory features with HoxD, exhibits its own distinct expression dynamics and functional contributions.

Future research directions include elucidating the precise mechanisms of chromatin topology establishment, understanding the functional significance of single-cell heterogeneity in Hox expression, and exploring how modifications of these conserved genetic programs contribute to the evolution of novel limb morphologies. The continued development of sophisticated genetic tools and single-cell technologies will undoubtedly provide deeper insights into the complex interplay between these essential regulatory genes.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the distinct yet complementary functions of HoxA and HoxD clusters provides valuable insights into the genetic basis of congenital limb disorders and potential therapeutic strategies. The extensive functional redundancy between these clusters suggests that therapeutic approaches may need to target multiple genes simultaneously, while the sophisticated regulatory mechanisms offer potential opportunities for precise intervention.

The precise patterning of vertebrate limbs is a fundamental process in developmental biology, orchestrated by an evolutionarily conserved genetic toolkit. At the heart of this process lies the Hox gene family—encoding transcription factors that provide positional information along the anterior-posterior body axis. In tetrapods, Hox genes are organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD), each located on different chromosomes. These genes exhibit a remarkable phenomenon called collinear expression, whereby their order within the cluster corresponds to both their temporal activation and spatial expression domains along the developing body axes [4]. During limb development, particularly in the limb bud mesenchyme, specific Hox genes from the HoxA and HoxD clusters demonstrate nested, overlapping expression patterns that play distinct yet coordinated roles in patterning the proximal-distal and anterior-posterior axes of the emerging limb [4] [10].

The comparative analysis of HoxA and HoxD cluster functions reveals both conserved principles and species-specific adaptations in limb patterning mechanisms. While murine models have provided foundational insights, recent research in zebrafish and chick embryos has refined our understanding of how these gene clusters orchestrate limb development. This guide systematically compares the experimental evidence for HoxA and HoxD cluster functions, providing researchers with structured data, methodological protocols, and visual frameworks to navigate this complex field.

Comparative Functions of HoxA and HoxD Clusters in Limb Development

Evolutionary Conservation and Divergence

The fundamental role of Hox genes in limb development demonstrates deep evolutionary conservation between tetrapods and bony fishes. In mice, the paralog groups 9-13 of HoxA and HoxD clusters are critically required for limb development, with simultaneous deletion of both clusters resulting in severe limb truncation [4]. Similarly, zebrafish—which possess seven Hox clusters due to teleost-specific whole-genome duplication—retain this functional requirement. Zebrafish have two HoxA-derived clusters (hoxaa and hoxab) and one HoxD-derived cluster (hoxda), which collectively perform functions analogous to their murine counterparts [4].

Despite this conservation, important functional differences exist between HoxA and HoxD clusters across species. In zebrafish, the hoxab cluster appears to have the highest contribution to pectoral fin formation, followed by hoxda and then hoxaa, suggesting a hierarchical functional redundancy [4]. This contrasts with murine models where HoxA and HoxD clusters play more balanced but distinct roles in proximal-distal patterning.

Table 1: Functional Comparison of HoxA and HoxD Clusters in Limb Development

| Feature | HoxA Cluster | HoxD Cluster | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role in Limb Development | Proximal-distal patterning (stylopod/zeugopod) and growth initiation | Distal patterning (autopod) and skeletal element formation | Mouse knockouts show proximal defects (HoxA) versus distal defects (HoxD) [4] |

| Expression Pattern in Limb Bud | Nested expression with proximal-distal collinearity | Bimodal expression with early proximal and late distal phases | Zebrafish hoxaa/hoxab/hoxda mutants show differential fin truncations [4] |

| Key Target Genes | Shha, Fgf10 | Shha, Fgf8 | shha markedly downregulated in zebrafish hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- mutants [4] |

| Functional Hierarchy | hoxab > hoxaa in zebrafish | hoxda essential for posterior fin elements | Triple mutants show hoxab has highest contribution [4] |

| Phenotype of Cluster Deletion | Shortened endoskeletal disc and fin-fold | Defects in posterior fin structures | Zebrafish triple mutants show severe shortening of both structures [4] |

Zebrafish Hox Cluster Deletion Phenotypes

Recent genetic studies in zebrafish provide compelling quantitative data on the specific contributions of HoxA-related and HoxD-related clusters to pectoral fin development. The following table summarizes the phenotypic consequences of various cluster deletion combinations:

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Pectoral Fin Defects in Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Endoskeletal Disc Length | Fin-fold Length | shha Expression in Fin Bud | tbx5a Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Normal | Normal | Normal (posterior portion) | Normal expression pattern |

| hoxaa-/- | Minimal effect | Minimal effect | Minimally affected | Normal |

| hoxab-/- | Shortened | Shortened | Reduced | Reduced |

| hoxda-/- | Minimal effect | Minimal effect | Minimally affected | Normal |

| hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- | Significantly shorter | Significantly shorter | Markedly downregulated | Reduced |

| hoxaa-/-;hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- | Shortest | Shortest | Most severely downregulated | Normal initiation, reduced later |

The quantitative data reveal that the hoxab cluster has the most significant contribution to pectoral fin development, particularly in regulating shha expression, which is essential for posterior fin growth and patterning [4]. Importantly, tbx5a expression—critical for the initial induction of pectoral fin buds—remains normal in the triple mutants, indicating that HoxA and HoxD-related clusters function after the initial specification of the fin field [4].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genetic Manipulation Techniques

CRISPR-Cas9 Cluster Deletion in Zebrafish

The generation of zebrafish Hox cluster mutants relies on sophisticated CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing approaches:

- Target Design: Multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) are designed to flank the entire Hox cluster, typically targeting regions upstream of the first gene and downstream of the last gene in the cluster.

- Microinjection: Cas9 mRNA and gRNAs are co-injected into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Mutant Screening: Founders (F0) are outcrossed to wild-type fish, and F1 progeny are screened for large deletions using PCR with primers outside the targeted region.

- Stable Line Establishment: Fish with confirmed deletions are raised to establish stable mutant lines through successive generations [7].

The simultaneous deletion of multiple Hox clusters (e.g., hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda) requires crossing of individual cluster mutants and genotyping of double or triple homozygous offspring, which typically occur at Mendelian ratios (e.g., 1/16 for double homozygotes) [7].

Chick Electroporation Approaches

Studies in chick embryos provide complementary insights through targeted manipulation of Hox expression:

- Plasmid Construction: Dominant-negative Hox variants (lacking the C-terminal portion of the homeodomain) or full-length Hox genes are cloned into expression vectors.

- Electroporation: Plasmids are electroporated specifically into the dorsal layer of the lateral plate mesoderm in HH12 chick embryos.

- Expression Analysis: After 8-10 hours (reaching HH14), transfected regions are identified by co-electroporated EGFP markers, and downstream effects on Tbx5 and other limb markers are analyzed [11].

Phenotypic Analysis Methods

Morphological Assessment

- Cartilage Staining: Alcian blue staining of 5 dpf zebrafish larvae to visualize cartilaginous endoskeletal discs.

- Micro-CT Scanning: Used for surviving adult zebrafish to analyze skeletal defects in three dimensions, particularly useful for identifying defects in the posterior portion of the pectoral fin [4].

Molecular Characterization

- Whole-mount in situ hybridization: To examine spatial expression patterns of key genes like tbx5a and shha in zebrafish embryos (e.g., at 30 hpf and 48 hpf).

- Bulk RNA-seq: Transcriptomic analysis of specific tissues from mutant embryos to identify differentially expressed genes and pathways [12].

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Networks

The following diagram illustrates the key genetic interactions between Hox clusters and critical limb patterning genes:

The diagram illustrates how Hox genes from different clusters regulate distinct aspects of limb development through specific target genes. The HoxB cluster (specifically hoxba and hoxbb in zebrafish) plays a critical role in the initial positioning of limb buds through direct induction of Tbx5 expression [7]. Subsequently, HoxA and HoxD clusters regulate limb outgrowth and patterning through both overlapping and distinct targets, with HoxA influencing proximal-distal patterning and HoxD contributing to anterior-posterior patterning through regulation of Shh signaling [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Hox Gene Function in Limb Development

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | gRNAs targeting hox cluster boundaries | Generation of cluster deletion mutants | Zebrafish studies [4] [7] |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | DN-Hoxa4, DN-Hoxa5, DN-Hoxa6, DN-Hoxa7 | Loss-of-function studies in chick | Electroporation into LPM [11] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Visium assay | Mapping gene expression in developing limbs | Human embryonic limb atlas [13] |

| Lineage Tracing Tools | insc>mCD8-GFP in Drosophila | Tracking neural stem cell size and division | CNS patterning studies [14] |

| Cartilage Stains | Alcian blue | Visualization of cartilaginous elements in developing fins/limbs | Zebrafish phenotypic analysis [4] |

| in situ Hybridization Probes | tbx5a, shha, Hox genes | Spatial expression pattern analysis | Zebrafish and chick studies [4] [7] |

| Micro-CT Imaging | Skyscan systems | 3D skeletal structure analysis | Adult zebrafish pectoral fin defects [4] |

Comparative Models: From Zebrafish to Human

The experimental workflow for analyzing Hox gene function spans multiple model systems, each offering unique advantages:

Each model system offers distinct advantages for studying Hox gene function: zebrafish enables comprehensive genetic analysis of functional redundancy through cluster deletions [4] [7]; chick embryos allow precise spatial and temporal manipulation of gene expression [11]; mouse models provide insights into mammalian-specific patterning mechanisms [12]; and human embryonic studies reveal species-specific features of limb development [13].

Recent single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses of human embryonic limbs have confirmed the conservation of core Hox-dependent patterning mechanisms while also identifying human-specific features. The human embryonic limb cell atlas has revealed extensive diversification of cells from a few multipotent progenitors to myriad differentiated cell states, with distinct mesenchymal populations in the autopod that may reflect specialized adaptations [13].

The comparative analysis of HoxA and HoxD cluster functions reveals a sophisticated regulatory system where these gene families play both distinct and overlapping roles in limb development. While HoxA-related clusters appear to have predominant functions in proximal-distal patterning and overall limb bud outgrowth, HoxD-related clusters specialize in anterior-posterior patterning and distal element formation. Both clusters converge on the regulation of key signaling pathways, particularly the Shh and Fgf pathways, which mediate their morphological effects.

The emerging picture from zebrafish, chick, mouse, and human studies is one of deep evolutionary conservation coupled with lineage-specific adaptations. The fundamental principle of collinear Hox gene expression in limb bud mesenchyme is maintained across vertebrates, but the specific contributions of individual clusters and genes have diversified through processes like whole-genome duplication and cis-regulatory evolution. For researchers investigating limb development and congenital limb disorders, these insights highlight the importance of considering both the conserved core mechanisms and species-specific differences when translating findings across model systems.

The Hox family of homeodomain transcription factors are master regulators of embryonic development, specifying positional identity along the body axis. Among these, the paralog groups 9-13 of the HoxA and HoxD clusters play particularly crucial and overlapping roles in patterning the mammalian limb. These genes exhibit a remarkable functional redundancy, wherein the deletion of single genes produces minimal phenotypes, while combined deletions result in severe limb malformations. This review synthesizes current evidence from key experimental models to compare and contrast the cooperative functions of HoxA and HoxD 9-13 paralogs in limb development, providing a comprehensive analysis of their redundant, complementary, and specific roles in patterning the stylopod, zeugopod, and autopod.

Comparative Analysis of HoxA and HoxD Cluster Functions

Domain-Specific Functional Redundancy in Limb Patterning

Table 1: Functional Domains of Hox 9-13 Paralogs in Mouse Limb Development

| Limb Region | Hox Paralog Groups | Primary Cluster Contribution | Phenotype of Combined Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stylopod (humerus/femur) | Hox9-10 | HoxA & HoxD | Reduced proximal elements; minor role in stylopod patterning [15] |

| Zeugopod (ulna/radius, tibia/fibula) | Hox11 | HoxA & HoxD (HoxC contributes in hindlimb) | Striking reduction in ulna and radius size [15] [16] |

| Autopod (wrist/ankle, digits) | Hox12-13 | HoxA & HoxD | Complete loss of autopod elements; disrupted digit patterning [9] |

The functional redundancy between HoxA and HoxD clusters follows a proximal-distal logic in limb patterning. While Hox9 and Hox10 paralogs primarily pattern the stylopod (the proximal limb segment containing the humerus or femur), their functional redundancy is partial, with flanking genes playing minor but detectable roles [15]. The zeugopod (middle segment containing the ulna/radius or tibia/fibula) is predominantly patterned by Hox11 paralogs, where combined mutation of Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 produces a dramatic reduction in the size of the ulna and radius, far exceeding the subtle defects observed in single mutants [15]. The most severe redundancy is observed in the autopod (distal segment containing the wrist/ankle and digits), where combined inactivation of Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 results in an almost complete lack of chondrified condensations, demonstrating that the activity of group 13 Hox gene products is absolutely essential for autopodal patterning in tetrapod limbs [9].

Quantitative Phenotypic Severity Across Mutation Combinations

Table 2: Phenotypic Severity in Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants (5 dpf)

| Genotype | Endoskeletal Disc Length | Fin-fold Length | shha Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Normal | Normal | Normal [4] |

| hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/- | No significant difference | Shortened | Not provided |

| hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- | Significantly shorter | Shortest among doubles | Markedly down-regulated [4] |

| hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- | Significantly shorter | Shortest | Markedly down-regulated [4] |

Recent research in zebrafish pectoral fin development (homologous to tetrapod forelimbs) has quantified the cooperative functions of HoxA- and HoxD-related clusters. The phenotypic severity follows a clear gene dosage pattern, where triple homozygous mutants (hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/-) exhibit the most severe truncation of both the endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [4]. Among the clusters, hoxab demonstrates the highest contribution to pectoral fin formation, followed by hoxda and then hoxaa [4]. This hierarchy of functional redundancy underscores the complementary but unequal contributions of different Hox clusters to appendage patterning.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Key Experimental Approaches for Dissecting Functional Redundancy

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Multi-Gene Knockout Strategy

The most insightful approach for studying Hox redundancy involves the generation of compound mutants with systematic deletions of multiple Hox genes. In mice, a novel recombineering method has enabled the simultaneous introduction of frameshift mutations into multiple flanking genes (Hoxa9,10,11 and Hoxd9,10,11), preserving intergenic noncoding RNAs and enhancers to maintain normal cluster cross-regulation [15]. In zebrafish, the CRISPR-Cas9 system has been employed to generate mutants with various combinations of deletions in hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters, allowing for the quantification of phenotypic severity across different genotypic combinations [4].

Phenotypic Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive phenotypic analysis involves multiple complementary approaches. For skeletal patterning, cartilage and bone staining (e.g., Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red) provides detailed visualization of skeletal elements, while micro-CT scanning enables high-resolution three-dimensional reconstruction of skeletal defects in adult specimens [4]. For molecular analysis, whole-mount in situ hybridization reveals spatial expression patterns of key regulatory genes such as shha and tbx5a [4], and laser capture microdissection coupled with RNA-Seq allows for precise characterization of gene expression programs in specific limb compartments [15].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Hox Gene Regulation of Limb Signaling Centers

The severe limb defects observed in HoxA and HoxD compound mutants result from the disruption of key signaling centers that control limb bud outgrowth and patterning. Mouse mutants lacking Hoxa9,10,11 and Hoxd9,10,11 show severely reduced Shh expression in the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) and decreased Fgf8 expression in the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) [15]. Similarly, in zebrafish HoxA- and HoxD-related cluster mutants, expression of shha in fin buds is markedly down-regulated, particularly in hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- and triple homozygous mutants [4]. This disruption of the Shh-Fgf feedback loop essential for limb bud outgrowth leads to a reduced mesenchymal progenitor cell pool and subsequent truncation of skeletal elements.

Regulatory Architecture and Collinear Expression

The functional redundancy between HoxA and HoxD clusters is facilitated by their shared bimodal regulatory architecture. Both clusters are controlled by two waves of transcriptional activation involving distinct regulatory landscapes. At the HoxD locus, a telomeric regulatory domain (T-DOM) controls the early collinear expression in the proximal limb (stylopod and zeugopod), while a centromeric regulatory domain (C-DOM) controls the later "distal phase" expression in the autopod [3] [17]. This bimodal regulation creates a domain of low Hoxd gene expression that generates the future wrist and ankle articulations [17]. A similar regulatory strategy is employed by the HoxA cluster, with shared 5′ regulatory landscapes suggesting an ancient origin for this bimodal control mechanism [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Hox Gene Redundancy

| Reagent/Model | Specifications | Research Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-gene Hox mutants | Hoxa9,10,11-/-/Hoxd9,10,11-/- mice | Analysis of flanking gene redundancy in zeugopod development | [15] |

| Cluster deletion mutants | hoxaa-/-;hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- zebrafish | Study of complete functional redundancy across clusters | [4] |

| Hox13 compound mutants | Hoxa13-/-/Hoxd13-/- mice | Investigation of autopod-specific redundancy | [9] |

| RNA-Seq datasets | LCM-derived RNA from wild-type and mutant limb compartments | Identification of downstream pathways and targets | [15] |

| Chromatin conformation | 4C-seq, CHi-C from developing limbs | Analysis of bimodal regulatory interactions | [3] [17] |

The essential cooperative role of HoxA and HoxD 9-13 paralogs in limb patterning represents a paradigm of functional redundancy in developmental genetics. Through a combination of partial functional equivalence and specific contributions, these genes control limb development along the proximal-distal axis in a dosage-dependent manner. The hierarchical redundancy, where the combined function of multiple genes ensures robustness in patterning, has significant implications for understanding the evolution of limb diversity and the etiology of human congenital limb malformations. Future research exploiting single-cell technologies and sophisticated genetic models will further elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this remarkable example of developmental system redundancy.

In the field of developmental biology, Hox genes are master regulators of embryonic patterning, with the HoxA and HoxD clusters playing particularly crucial and comparative roles in the development of paired appendages. In jawed vertebrates, the HoxA and HoxD gene clusters undertake deeply conserved, yet distinct, functions in orchestrating the growth and patterning of limbs. These genes exhibit remarkable functional redundancy while also executing specific, non-overlapping responsibilities. The phenotypic consequences of disrupting these genes range from complete limb truncation to the highly specific loss of individual skeletal segments, providing a powerful natural experiment for deciphering their unique contributions. This guide systematically compares the functions of HoxA versus HoxD clusters by synthesizing recent genetic evidence, detailing the experimental protocols that generate these insights, and visualizing the complex regulatory pathways involved. Understanding this phenotypic spectrum is fundamental for research into congenital limb anomalies and evolutionary developmental biology.

Comparative Phenotypic Analysis of Hox Cluster Mutants

The functional disruption of HoxA and HoxD clusters, through various genetic techniques, produces a spectrum of phenotypes that reveal their core responsibilities in limb formation. The table below synthesizes phenotypic data from multiple model organisms to provide a direct comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Phenotypes of HoxA and HoxD Cluster Mutations in Vertebrate Appendages

| Gene Cluster | Model Organism | Genetic Manipulation | Observed Phenotype | Key Molecular Markers Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoxA & HoxD | Mouse | Simultaneous deletion of both HoxA & HoxD clusters | Severe limb truncation [4] | N/D |

| HoxA & HoxD | Zebrafish | Triple deletion of hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda (HoxA/D-related) |

Severely shortened pectoral fin; shortened endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [4] | Down-regulation of shha in fin buds [4] |

| HoxD | Mouse | Deletion of telomeric regulatory domain (T-DOM) | Alters zeugopod (forearm/shank) development; differences between fore- and hindlimbs [5] | Reduced Hoxd gene expression in the zeugopod [5] |

| HoxD | Chicken | Comparative analysis of regulatory mechanism | Conserved bimodal regulation, but shortened T-DOM regulation duration in hindlimb buds [5] | Reduction in Hoxd gene expression in hindlimb zeugopod [5] |

| HoxB-derived | Zebrafish | Double deletion of hoxba and hoxbb clusters |

Complete absence of pectoral fins [7] | Failure of tbx5a induction in pectoral fin field [7] |

The data demonstrates a clear functional hierarchy. The most severe phenotypes, including complete limb absence or drastic truncation, result from the combined loss of HoxA and HoxD cluster function, underscoring their redundant and essential role in initiating limb outgrowth [4] [7]. In contrast, perturbations specifically affecting the HoxD cluster, particularly its complex regulatory landscapes, tend to result in segment-specific losses, especially in the zeugopod and autopod, highlighting its refined role in patterning specific limb segments [5]. Interestingly, the HoxB cluster, derived from the same ancestral cluster as HoxA and HoxD, has a distinct and critical role in determining the initial anteroposterior position of limb bud formation, a function that is genetically separable from the patterning roles of HoxA/D [7].

Experimental Protocols for Functional Analysis

To generate the comparative data presented above, researchers employ a suite of sophisticated genetic and molecular techniques. The following protocols detail the key methodologies.

Generation of Multi-Cluster Deletion Mutants in Zebrafish

The systematic deletion of multiple Hox clusters in zebrafish provides a model to dissect functional redundancy and specificity.

- CRISPR-Cas9 Target Design: Design multiple single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that flank the entire genomic locus of the target Hox cluster (e.g.,

hoxaa,hoxab,hoxda). - Microinjection: Co-inject sgRNAs and Cas9 protein into single-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Mutant Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to identify germline-transmitting founders. Genotype the F1 offspring to identify individuals carrying large deletions.

- Line Establishment: Intercross F1 heterozygotes to generate homozygous mutant larvae (F2) for phenotypic analysis.

- Phenotypic Analysis: At 3-5 days post-fertilization (dpf), analyze pectoral fin morphology. Cartilage is stained with Alcian Blue to visualize the endoskeletal disc.

- Molecular Analysis: Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) on mutant larvae at specific stages (e.g., 48 hours post-fertilization) to examine the expression of critical genes like

shhaandtbx5a[4] [7].

Chromatin Conformation Analysis in Mouse Limb Buds

This protocol analyzes the dynamic 3D genome architecture that regulates Hoxd gene expression during limb development.

- Tissue Dissection: Dissect anterior and posterior regions from distal limb buds of E10.5 mouse embryos.

- Cell Line Derivation (Optional): Immortalize mesenchymal cells from the dissected anterior and posterior tissue to create stable cell lines for in vitro study.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP):

- For native ChIP (nChIP), isolate nuclei and digest chromatin with micrococcal nuclease (MNase).

- Immunoprecipitate the fragmented chromatin using antibodies against specific histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3 for Polycomb repression) or Polycomb group proteins like Ring1B.

- For cross-linked ChIP, fix cells with formaldehyde, sonicate to shear DNA, and immunoprecipitate.

- Analysis: Quantify the enriched DNA by qPCR or hybridize to tiling arrays (ChIP-chip) to determine the abundance of histone modifications across the HoxD locus in anterior versus posterior cells [6].

- Chromatin Conformation Capture (3C-based methods): Use techniques like 4C or Hi-C on dissected limb bud tissue or derived cell lines to identify long-range physical interactions between the HoxD cluster and its distal enhancers, such as the Global Control Region (GCR) [6].

Regulatory Element Analysis via Mouse Transgenics

This tests the functional capacity of conserved non-coding DNA sequences to act as enhancers.

- Element Isolation: Clone a candidate conserved sequence (e.g., the CsB element from skate or zebrafish) into a reporter vector (e.g., lacZ or GFP) controlled by a minimal promoter.

- Pronuclear Injection: Microinject the linearized reporter construct into the pronucleus of fertilized mouse oocytes.

- Embryo Analysis: Harvest transgenic embryos at E12.5 and stain for the reporter gene (e.g., β-galactosidase for lacZ) to visualize the spatial and temporal activity of the enhancer in the developing limb [18].

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic

The functional relationship between Hox genes and their regulatory inputs can be summarized in the following pathway diagram.

Diagram 1: Hox gene functional hierarchy in limb development.

The regulatory architecture controlling HoxD gene expression in the limb is a classic example of bimodal regulation, which is shared by the HoxA cluster [5] [18]. The following diagram illustrates this complex mechanism.

Diagram 2: Bimodal regulatory logic of the HoxD cluster.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and models used in foundational Hox gene limb patterning research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Models for Hox Limb Patterning Studies

| Reagent / Model | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants | CRISPR-generated mutants for hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda, hoxba, hoxbb clusters. |

Dissecting functional redundancy and specific roles of Hox clusters in fin development [4] [7]. |

| T-Box Reporter Assays | Reporters for Tbx5 expression or its limb-specific enhancers. |

Determining how Hox genes (particularly HoxB) initiate limb bud formation [7]. |

| H3K27me3 & Ring1B Antibodies | Antibodies for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) against Polycomb repressive marks. | Probing the repressive chromatin state over Hox clusters in anterior limb bud cells [6]. |

| Global Control Region (GCR) Reporters | Transgenic mice carrying reporter genes under the control of the HoxD GCR. | Studying the enhancer logic driving the distal phase (autopod) Hoxd expression [6]. |

| Anterior/Posterior Limb Bud Cell Lines | Immortalized mesenchymal cell lines derived from distinct E10.5 mouse limb bud regions. | In vitro analysis of anterior-posterior differences in Hox chromatin topology and expression [6]. |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) | Protocol using RNA probes to visualize spatial gene expression patterns in embryos. | Characterizing Hox gene expression domains in wild-type and mutant limb/fin buds [5] [4]. |

While the HoxA and HoxD gene clusters are universally recognized for their central role in limb skeleton formation, emerging research reveals distinct and specialized functions for HoxA that extend into the broader integration of musculoskeletal tissues. This review systematically compares the functions of the HoxA and HoxD clusters, moving beyond their established cooperative roles in skeletal patterning to highlight HoxA's unique contributions to coordinating muscle, tendon, and connective tissue development. We synthesize quantitative phenotypic data from genetic perturbation studies across model organisms, detail the experimental methodologies enabling these discoveries, and visualize the complex regulatory networks. Furthermore, we identify HoxA's continued expression in adult musculoskeletal progenitor cells, suggesting its potential role in tissue homeostasis and regeneration, with significant implications for therapeutic targeting in degenerative diseases and regenerative medicine.

The Hox gene family, encoding evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, provides a fundamental blueprint for the vertebrate body plan, with particular importance in patterning the limbs. In mammals, 39 Hox genes are organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD), with the HoxA and HoxD clusters being the principal architects of limb development [19]. For decades, research has focused on their indispensable, cooperative roles in guiding the formation of the limb skeleton—the stylopod (upper limb), zeugopod (forearm/leg), and autopod (hand/foot). A landmark finding demonstrated that the simultaneous deletion of both HoxA and HoxD clusters in mice results in a severe truncation of limb skeletal elements, underscoring their synergistic function [4].

However, a paradigm shift is underway, moving beyond a skeleton-centric view. A growing body of evidence indicates that while HoxA and HoxD functions overlap, they are not redundant. The HoxA cluster is emerging as a critical regulator of a fully integrated musculoskeletal system. It exerts influence over the development of non-skeletal tissues, including muscle, tendon, and dermal structures, and its expression persists into adulthood in specific progenitor cell populations. This article provides a comparative analysis of HoxA versus HoxD cluster functions, presenting quantitative phenotypic data, detailed experimental protocols, and visualizations of the regulatory pathways that underscore HoxA's unique and essential role in musculoskeletal integration.

Comparative Analysis of HoxA and HoxD Functions in Limb Development

The functional interplay between HoxA and HoxD has been extensively studied through genetic knockout models in mice and zebrafish. The table below synthesizes key quantitative data from these studies, highlighting both the collaborative and distinct roles of each cluster.

Table 1: Quantitative Phenotypic Comparisons of HoxA and HoxD Cluster Mutants in Limb/Fin Development

| Model Organism | Genetic Perturbation | Key Skeletal Phenotypes | Key Non-Skeletal/Musculoskeletal Integration Phenotypes | Key Molecular Markers Altered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Simultaneous deletion of HoxA & HoxD clusters [4] | Severe truncation of distal limb elements [4] | Not reported | Not specified |

| Zebrafish | Triple mutant: hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- [4] |

Significant shortening of the endoskeletal disc (cartilage precursor) | Significant shortening of the non-cartilaginous fin-fold [4] | shha expression markedly downregulated in fin buds [4] |

| Zebrafish | hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- double mutant [4] |

Significant shortening of endoskeletal disc | Significant shortening of the fin-fold [4] | shha expression downregulated [4] |

| Zebrafish | hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/- double mutant [4] |

No significant difference in endoskeletal disc length | Shortening of the fin-fold [4] | Not specified |

| Mouse | Single-cell RNA-seq of wild-type limb buds [8] | N/A | Heterogeneous combinatorial Hox gene expression in single cells, suggesting coordination for specific cell fates [8] | N/A |

The data reveal that the loss of HoxA-related clusters in zebrafish has a more pronounced effect on the non-cartilaginous fin-fold—a structure involving integumentary and connective tissues—than on the cartilaginous endoskeletal disc. This points to a specific role for HoxA in patterning non-skeletal tissues. Furthermore, the reliance of Sonic hedgehog (shha) expression on HoxA/HoxD function is critical, as SHH is a key morphogen for both skeletal and soft tissue patterning.

HoxA's Specific Role in Musculoskeletal Integration

Regulation of Musculoskeletal Progenitors and Connective Tissues

Recent reviews synthesize that Hox genes, including those in the HoxA cluster, are not only expressed during embryonic patterning but are also maintained in specific stromal and progenitor cells in adult tissues such as muscle, tendon, and bone [19]. This sustained expression is theorized to be crucial for maintaining regional identity and managing tissue homeostasis and repair in response to injury. The function of HoxA in these contexts appears to be in establishing the positional identity of the connective tissue scaffolds, or "stroma," upon which myoblasts and tenocytes organize and function.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

HoxA proteins influence musculoskeletal integration by directly and indirectly modulating key signaling pathways.

- Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Signaling: As evidenced in zebrafish, HoxA-related genes are crucial for maintaining

shhaexpression in the developing fin/limb bud [4]. SHH signaling is a master regulator of patterning across both anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes, influencing the development of muscles, tendons, and nerves alongside the skeleton. - Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Remodeling: A study on regional skin properties found that HOXA9 regulates dermal fibroblast proliferation and the expression of extracellular matrix-related genes, which are processes directly associated with tissue structure and elasticity [20]. This ECM regulatory function is likely conserved in other musculoskeletal connective tissues.

The diagram below illustrates the proposed regulatory network through which HoxA genes coordinate musculoskeletal integration.

Diagram Title: HoxA's Multifaceted Role in Musculoskeletal Integration

Experimental Protocols for Delineating Hox Cluster Function

Understanding the distinct roles of HoxA and HoxD has relied on sophisticated genetic and molecular techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this review.

Generation of Multi-Cluster Hox Mutants in Zebrafish

This protocol is adapted from Ishizaka et al. (2024) in Scientific Reports [4].

- Objective: To create and analyze zebrafish with combined deletions of HoxA-related (

hoxaa,hoxab) and HoxD-related (hoxda) clusters and assess pectoral fin development. - Procedure:

- Mutant Generation: Use the CRISPR-Cas9 system to generate mutant lines with individual and combined deletions of the

hoxaa,hoxab, andhoxdaclusters. - Genetic Crosses: Perform intercrosses between triple hemizygous mutants to obtain larvae with various combinations of homozygous cluster deletions.

- Phenotypic Analysis (Larval Stage):

- Image live 3 days post-fertilization (dpf) larvae to assess overall pectoral fin morphology and length.

- At 5 dpf, fix larvae and perform cartilage staining (e.g., Alcian Blue) to visualize and measure the endoskeletal disc along anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes.

- Measure the length of the non-cartilaginous fin-fold from the stained specimens.

- Phenotypic Analysis (Adult Stage): In surviving adult mutants, use micro-CT scanning to analyze the skeletal structure of the pectoral fin, focusing on the posterior portion.

- Mutant Generation: Use the CRISPR-Cas9 system to generate mutant lines with individual and combined deletions of the

- Key Outcome Measures: Quantitative measurements of fin length, endoskeletal disc dimensions, and fin-fold length, followed by statistical comparison between genotypes.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Limb Bud Cells

This protocol is adapted from Darbellay et al. (2018) in BMC Biology [8].

- Objective: To characterize the heterogeneity of Hox gene expression and its correlation with specific cell types in the developing limb.

- Procedure:

- Tissue Dissociation: Microdissect autopod (future hand/foot) tissue from embryonic day (E) 12.5 mouse limb buds. Dissociate the tissue into a single-cell suspension using enzymatic treatment.

- Cell Sorting (Optional): To enrich for Hox-expressing cells, use a mouse line with a GFP reporter knocked into the

Hoxd11locus and sort GFP-positive cells using FACS. - Single-Cell Capture and Library Prep: Load the single-cell suspension onto a Fluidigm C1 microfluidics chip for automated cell capture and lysis. Perform reverse transcription and cDNA amplification within the chip.

- Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis: Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified cDNA and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina). Use bioinformatic pipelines for read alignment, gene counting, and clustering analysis to identify cell populations based on their transcriptional signatures.

- Key Outcome Measures: Identification of distinct cell clusters based on Hox gene combinatorial expression patterns (e.g., Hoxd13+/Hoxd11-, Hoxd13+/Hoxd11+). Correlation of Hox codes with markers for specific cell lineages (e.g., myoblasts, tenocytes, chondrocytes).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Hox Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Hox Gene Function in Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted genome editing for generating knockout mutant models. | Creating zebrafish mutants with large deletions of entire Hox clusters (e.g., hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda) [4]. |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) | Spatial visualization of gene expression patterns in intact embryos/tissues. | Assessing the expression patterns of key genes like shha and tbx5a in zebrafish fin buds of mutant lines [4]. |

| Reporter Mouse Lines (e.g., Hoxd11::GFP) | Visualizing and tracking cells that express a specific gene of interest. | FACS-sorting of Hoxd11-expressing cells from developing mouse limbs for single-cell RNA-seq [8]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Profiling the complete transcriptome of individual cells to uncover cellular heterogeneity. | Revealing heterogeneous combinatorial expression of Hoxd genes in single limb bud cells [8]. |

| Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) | High-resolution, non-destructive 3D imaging of mineralized tissues and skeletons. | Analyzing defects in the skeletal structure of the pectoral fin in surviving adult zebrafish mutants [4]. |

The comparative analysis clearly demonstrates that while the HoxA and HoxD clusters function cooperatively to pattern the limb skeleton, the HoxA cluster possesses unique and critical functions in musculoskeletal integration. Its influence on the development of non-skeletal tissues like the fin-fold, its role in regulating key signaling pathways such as SHH, and its impact on ECM composition underscore a broader mandate in organizing the complete limb. The persistence of HoxA expression in adult stromal and progenitor cells opens exciting avenues for future research.

Future studies should focus on:

- Identifying the direct transcriptional targets of HOXA proteins in musculoskeletal progenitor cells.

- Elucidating the precise role of HoxA in tissue homeostasis and regeneration in adult models.

- Exploring the potential of modulating HoxA activity for therapeutic interventions in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases or traumatic injuries.

Understanding HoxA's comprehensive role moves us beyond the skeleton, providing a more holistic view of how the intricate patterns of muscles, tendons, and bones are so perfectly coordinated into a functional limb.

Experimental Models and Techniques: From Cluster Deletions to 3D Genome Architecture

In vertebrate developmental biology, Hox genes—master regulatory genes encoding transcription factors—play a pivotal role in specifying positional identity along the anterior-posterior body axis and are fundamental to the patterning of paired appendages [21] [18]. The evolution and development of limbs are primarily governed by genes from the HoxA and HoxD clusters [21] [5]. Their complex, spatiotemporally regulated expression directs the formation of skeletal elements in the stylopod (e.g., humerus), zeugopod (e.g., radius/ulna), and autopod (e.g., digits) [5]. Understanding the mechanistic roles of HoxA and HoxD has been profoundly advanced by studying key animal models: zebrafish, mouse, and chick embryos. Each model offers unique advantages, and their comparative analysis allows researchers to disentangle conserved principles from species-specific adaptations in limb patterning. This guide objectively compares the insights gained from these three models, focusing on their experimental uses, the data they generate, and their respective strengths in elucidating the functions of HoxA versus HoxD clusters.

Model Organism Comparison

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and experimental applications of each model organism in Hox gene research.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Animal Models in Hox Gene Limb Patterning Research

| Feature | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Mouse (Mus musculus) | Chick (Gallus gallus) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Class | Actinopterygii (Ray-finned fish) | Mammalia | Aves |

| Appendage Studied | Pectoral and Pelvic Fins | Forelimbs and Hindlimbs | Wings and Legs |

| Key Hox Clusters | hoxa, hoxb, hoxc, hoxd (7 clusters in total) [22] | HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD (4 clusters) | HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD |

| Major Role in Limb/Fin Positioning | HoxB-derived clusters (hoxba/hoxbb) are essential for anterior-posterior positioning of pectoral fin buds via induction of tbx5a [22]. | HoxA and HoxD clusters are crucial for patterning; no single mutation causes severe limb positioning loss, suggesting high redundancy [22]. | Expression boundaries of Hox genes align with future limb positions; amenable to surgical manipulation [22]. |

| Major Role in Limb/Fin Patterning | hoxa and hoxda clusters (orthologous to tetrapod HoxA/D) cooperatively pattern pectoral fins [22]. HoxA11 and HoxA13 domains do not fully separate [21]. | HoxA and HoxD are critical for proximal-distal patterning. A bimodal regulatory mechanism controls transcriptions [5]. | HoxA and HoxD govern patterning. Exhibits a conserved bimodal regulatory mechanism with differences in enhancer activity vs. mouse [5]. |

| Distinctive Hox Expression Features | Co-expression of hoxa11 and hoxa13 in developing fins; no full separation of domains [21]. Transient "Distal Phase" (DP) HoxD expression. | Clear separation of HoxA11 (zeugopod) and HoxA13 (autopod) domains [21]. Robust, inverted "Distal Phase" (DP) HoxD expression in autopod. | Clear separation of HoxA11 and HoxA13 domains. DP HoxA expression observed in hindgut and vent [18] [1]. |

| Principal Experimental Advantages | Genetic transparency, external development, high fecundity. Powerful for CRISPR/Cas9-based mutagenesis of multiple clusters [22]. | Genetic and physiological similarity to humans. Extensive toolkit for conditional and compound mutagenesis (e.g., HoxA cluster deletion) [5] [23]. | Accessibility for surgical manipulation (e.g., bead implantation), electroporation, and ex ovo culture. Ideal for comparative studies of divergent forelimb/hindlimb morphology [5]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

This section details the methodologies and key findings from seminal experiments in each model organism.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Generation of Hox Cluster Mutants in Zebrafish This protocol is used to investigate functional redundancy among Hox clusters [22].

- Design gRNAs: Design multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the flanking regions of a specific entire hox cluster (e.g., hoxba or hoxbb).

- Microinjection: Co-inject Cas9 mRNA and the pool of gRNAs into single-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to identify founders carrying large cluster deletions.

- Generate Mutant Lines: Incross heterozygous (F1) carriers to generate homozygous cluster-deleted mutants (F2).

- Phenotypic Analysis: Analyze mutant embryos for fin/limb defects using whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) for key marker genes like tbx5a at 24-48 hours post-fertilization (hpf).

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of HoxD Regulation in Mouse and Chick Limb Buds This protocol is used to compare the evolutionarily conserved bimodal regulatory system of the HoxD cluster [5].

- Sample Collection: Collect mouse forelimb and hindlimb buds at Embryonic Day (E) 12.5. Collect chick wing and leg buds at Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 28 (equivalent to ~E12.5).

- Chromatin Conformation Analysis: Perform Hi-C or similar chromosome conformation capture techniques on limb bud cells to map the 3D genome architecture and identify Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) at the HoxD locus.

- Histone Modification Profiling: Conduct ChIP-seq experiments for active histone marks (e.g., H3K27ac) to map active enhancer regions within the telomeric (T-DOM) and centromeric (C-DOM) regulatory landscapes.

- Transcriptome Analysis: Perform RNA-seq or quantitative RT-PCR on micro-dissected limb bud domains to quantify Hoxd gene expression levels.

- Data Integration: Correlate chromatin interaction data, enhancer activity, and gene expression patterns to identify conserved and species-specific aspects of HoxD regulation.

Protocol 3: Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) for Hox Gene Expression A standard technique for visualizing spatial gene expression patterns in all three models [21] [18] [5].

- Fixation: Fix embryos in paraformaldehyde.

- Hybridization: Digest with proteinase K, then incubate with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNA probes complementary to the target Hox mRNA (e.g., HoxA13, HoxD13).

- Washing: Perform stringent washes to remove unbound probe.

- Immunodetection: Incubate with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody.

- Color Reaction: Immerse embryos in a staining solution containing NBT/BCIP, which produces a purple precipitate upon reaction with the enzyme.

- Analysis: Document expression patterns using microscopy.

The table below consolidates key quantitative findings from cross-species studies of Hox gene expression and function.

Table 2: Comparative Quantitative Data on Hox Gene Function from Animal Models

| Experimental Observation | Zebrafish | Mouse | Chick | Significance / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype of HoxB cluster loss | hoxba-/-;hoxbb-/- mutants: 100% absence of pectoral fins (n=15/252) [22]. | Hoxb5-/- mutants: Rostral shift of forelimb buds with incomplete penetrance [22]. | N/A (Data not available in search results) | Suggests differential redundancy and evolutionary divergence in the function of HoxB clusters for appendage positioning. |

| HoxA11 & HoxA13 expression domain separation | No full separation reported; domains overlap during fin development [21]. | Clear separation: HoxA11 in zeugopod, HoxA13 in autopod [21]. | Clear separation, similar to mouse [21]. | Domain separation correlates with the evolution of a distinct autopod (wrist/ankle and digits). |

| HoxD "Distal Phase" (DP) Expression | Present, but transient, in fin development [18]. | Strong, sustained DP expression in the autopod [18] [5]. | Present in limb buds; DP expression also found in non-limb structures (e.g., barbels) [18] [1]. | DP is an ancient regulatory module, co-opted for various distally elongated structures in vertebrates. |

| Comparison of HoxD gene expression levels (Forelimb vs. Hindlimb) | N/A | Similar Hoxd13 and Hoxd12 mRNA levels in E12.5 fore- and hindlimbs [5]. | Stronger Hoxd gene expression in wing buds vs. leg buds at HH28 [5]. | Correlates with the striking morphological divergence between avian wings and legs. |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic

The regulation of Hox genes during limb development, particularly the HoxD cluster, involves a sophisticated bimodal switch between two large regulatory domains. The following diagram illustrates this conserved mechanism and its species-specific modifications.

Figure 1: The Bimodal Regulatory Logic of the HoxD Cluster. This conserved mechanism involves a switch from telomeric (T-DOM) to centromeric (C-DOM) regulation, creating a zone of low Hox expression that forms the wrist/ankle. Species-specific differences in the timing and strength of these domains contribute to morphological diversity [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

A successful research program in comparative Hox gene biology relies on a suite of essential reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene and Limb Patterning Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted genome editing for generating knockout mutants of specific Hox genes or entire clusters. | Creating zebrafish hoxba;hoxbb double cluster mutants to study fin loss [22]. |

| DIG-Labeled RNA Probes | In situ hybridization for spatial visualization of gene expression patterns. | Mapping HoxA13 and HoxD13 mRNA domains in mouse, chick, and zebrafish embryos [21] [5]. |

| Species-Specific Hox Antibodies | Immunohistochemistry to detect and localize HOX proteins at the cellular level. | Distinguishing protein expression domains of HoxA11 and HoxA13 in axolotl limb regeneration [21]. |

| Transgenic Reporter Constructs | Assessing the activity of cis-regulatory elements (enhancers) in vivo. | Testing the function of human conserved non-coding elements (CNEs) in transgenic mouse and zebrafish embryos [24]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Small molecule signaling agonist used to manipulate Hox gene expression. | Testing competence of zebrafish hoxba;hoxbb mutants to induce tbx5a in fin buds [22]. |

| ChIP-seq Kits | Genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding sites and histone modifications. | Identifying active enhancer regions (H3K27ac) within the HoxD C-DOM and T-DOM in chick and mouse [5]. |

CRISPR-Cas9 Cluster Deletion Strategies and Phenotypic Analysis

In the field of developmental biology, Hox genes stand as master regulators of embryonic patterning, determining positional identity along the body axis in bilaterian animals. Among these, the HoxA and HoxD clusters play particularly crucial and interconnected roles in vertebrate limb development [18]. These genes exhibit remarkable collinear expression patterns, with their order on chromosomes corresponding to their spatial and temporal expression domains during embryogenesis [18] [5]. The posterior Hox genes (paralogs 9-13) in both clusters are especially critical for specifying limb structures, from the proximal stylopod to the distal autopod [4].

The complex regulation of Hox genes involves a bimodal control system where large chromatin domains on either side of the clusters—telomeric (T-DOM) and centromeric (C-DOM) regulatory domains—orchestrate precise expression patterns through dynamic three-dimensional genome architecture [5]. While this regulatory mechanism is largely conserved across tetrapods, species-specific variations in enhancer activity and temporal control contribute to the remarkable diversity of limb morphologies observed in nature [5]. This article compares contemporary CRISPR-Cas9 strategies for deleting entire Hox clusters and analyzes the resulting phenotypic outcomes, providing researchers with methodological insights for functional genomics in limb patterning research.

Experimental Approaches for Hox Cluster Deletion

CRISPR-Cas9 System Optimization

Efficient deletion of large genomic regions such as Hox clusters requires optimized CRISPR-Cas9 systems. Critical advances include the development of novel binary vectors such as pUbiCAS9-Red and pEciCAS9-Red, which incorporate codon-optimized Cas9 driven by either the Petroselinum crispum Ubiquitin4-2 promoter (PcUbi4-2) or a synthetic egg cell-specific (EC1) promoter [25]. These systems employ an attR1-attR2 Gateway cassette and Arabidopsis U6-26 RNA polymerase III promoters flanking a Cas9 small guide RNA (sgRNA) scaffold, enabling rapid Golden-Gate assembly of multiple sgRNAs without PCR amplification [25]. The inclusion of seed-specific fluorescent reporters permits non-destructive selection of Cas9-negative progeny, significantly streamlining the isolation of heritable deletion events.

The timing of Cas9 expression proves critical for heritable deletions. Studies demonstrate that using the EC1 promoter to drive Cas9 expression during early reproductive stages dramatically increases the efficiency of heritable genomic deletions (6-100% for different target regions) compared to constitutive promoters [25]. This approach has enabled generation of offspring carrying homozygous deletions of large genomic regions, including entire gene clusters.

Guide RNA Design and Validation

The design of highly efficient sgRNAs represents perhaps the most critical parameter for successful cluster deletion. Research indicates tremendous variability in sgRNA efficiency (4-69% across different constructs) [25]. To address this challenge, researchers have implemented pre-screening protocols where binary constructs carrying Cas9 and different sgRNA combinations are transfected into protoplasts, followed by semi-quantitative PCR amplification of targeted regions to assess deletion efficiency before generating stable transgenic lines [25].

The specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 systems remains an important consideration, with off-target effects reported at sites with base mismatches to the 20-base targeting sequences [26]. Strategies to minimize these effects include using modified Cas9 variants with enhanced fidelity, carefully controlling Cas9/gRNA exposure duration and concentration, and employing bioinformatic tools to select target sites with minimal off-target potential [27] [26]. For critical experiments, confirmation through multiple independent sgRNAs targeting the same locus provides additional validation.

Table 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Systems for Genomic Cluster Deletions

| System Component | Options | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Variants | SpCas9, SaCas9, FnCas12a, LbCas12a | SaCas9 shows high efficiency; Cas12a prefers T-rich PAMs [27] |

| Promoter Systems | Constitutive (pUbi), Egg cell-specific (EC1) | EC1 promoter dramatically improves heritable deletions (6-100% efficiency) [25] |

| Delivery Methods | Protoplast transfection, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation | Protoplast screening allows pre-selection of efficient sgRNAs [25] |

| sgRNA Design | 17-20nt spacers, PAM-appropriate | Efficiency varies widely (4-69%); requires empirical validation [25] |

Phenotypic Analysis of Hox Cluster Mutants

Zebrafish Hox Cluster Deletion Models

Recent research utilizing CRISPR-Cas9 has generated zebrafish mutants with various combinations of deletions in the hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters (homologs of mammalian HoxA and HoxD clusters) to investigate their functional requirements in pectoral fin development [4]. The phenotypic analysis reveals both compensatory mechanisms and specialized functions among these clusters.

Triple homozygous deletion mutants (hoxaa⁻⁄⁻;hoxab⁻⁄⁻;hoxda⁻⁄⁻) display present but severely shortened pectoral fins, indicating that these clusters function redundantly in pectoral fin formation [4]. Detailed morphological analysis shows that the contributions of individual clusters follow a hierarchy: hoxab cluster has the highest impact, followed by hoxda cluster, with hoxaa cluster showing the mildest effect [4]. This is evidenced by the observation that hoxab⁻⁄⁻;hoxda⁻⁄⁻ larvae exhibit the most severe shortening of both the endoskeletal disc and fin-fold among double mutants.

Table 2: Phenotypic Severity in Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Endoskeletal Disc Length | Fin-fold Length | Overall Fin Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Normal | Normal | Normal development |

| hoxaa⁻⁄⁻;hoxab⁻⁄⁻ | No significant difference from wild-type | Shortened | Mild fin defects |

| hoxab⁻⁄⁻;hoxda⁻⁄⁻ | Significantly shorter | Shortest among double mutants | Severe fin truncation |

| hoxaa⁻⁄⁻;hoxab⁻⁄⁻;hoxda⁻⁄⁻ | Shortest | Shortest | Most severe truncation |

The investigation into developmental mechanisms reveals that the initial establishment of pectoral fin buds occurs normally in triple mutants, as tbx5a expression remains undisturbed [4]. However, subsequent signaling pathways crucial for fin outgrowth are severely compromised, with marked downregulation of shha expression in the posterior portion of fin buds, particularly evident in hoxab⁻⁄⁻;hoxda⁻⁄⁻ and triple mutants [4]. This demonstrates that Hox clusters act after initial bud specification to promote fin growth through maintenance of Shh signaling.

Mammalian and Salamander Models

Beyond zebrafish, mammalian studies reveal that simultaneous deletion of both HoxA and HoxD clusters in mice leads to severe limb truncation, particularly affecting distal elements [4]. The phenotypic outcome exceeds what would be expected from simple additive effects of single cluster deletions, indicating synergistic interactions between these clusters during limb patterning.

In salamander limb regeneration models, Hox genes are re-expressed during the regenerative process, mirroring their developmental roles [28]. Recent research has identified a positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh that maintains posterior identity in axolotl limbs [29]. Disruption of this circuit through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of Sall4, a transcription factor upstream of Shh signaling, results in limb regenerate defects including missing digits, fusion of digit elements, and malformations of the radius and ulna [28]. This highlights the conserved nature of Hox-related regulatory networks across development and regeneration.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Networks

The molecular circuitry governing Hox function in limb development involves complex interactions between multiple signaling pathways. The HoxA and HoxD clusters are regulated through dynamic chromatin interactions with telomeric (T-DOM) and centromeric (C-DOM) regulatory domains, creating a bimodal control system that patterns proximal and distal limb structures respectively [5]. This regulatory architecture is largely conserved across tetrapods, though species-specific variations in enhancer activity contribute to morphological diversity [5].

During limb development and regeneration, a positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh establishes and maintains posterior identity [29]. Posterior cells express residual Hand2 transcription factor from development, which primes them to form a Shh signaling center after limb amputation [29]. During regeneration, Shh signaling also maintains Hand2 expression, creating a self-sustaining circuit that safeguards positional memory even after regeneration is complete [29]. This circuit is susceptible to experimental manipulation, as transient exposure of anterior cells to Shh during regeneration can establish an ectopic Hand2-Shh loop, effectively converting anterior cells to a posterior memory state [29].