In Situ Hybridization Sensitivity Comparison: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of in situ hybridization (ISH) sensitivity for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

In Situ Hybridization Sensitivity Comparison: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of in situ hybridization (ISH) sensitivity for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of ISH and its advantages over immunostaining, explores modern high-sensitivity methodologies like RNAscope and HCR, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance. The content synthesizes validation data and comparative benchmarks to aid in the selection of optimal ISH techniques for specific research and clinical applications, from basic discovery to diagnostic assay development.

Understanding In Situ Hybridization: Principles, Advantages, and Evolution

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that allows for the precise localization of specific DNA or RNA sequences within individual cells, tissue sections, or entire tissues (in whole mount ISH) [1]. The core principle of ISH is the use of a labeled, complementary nucleic acid strand, known as a probe, which binds (hybridizes) to its target sequence within the morphologically preserved biological sample [2] [1]. This technique provides crucial temporal and spatial information about gene expression and genetic loci that cannot be obtained through bulk extraction methods [3].

Within the context of research comparing the sensitivity of different ISH methodologies, understanding the fundamental components and variations of the technique is paramount. This guide details the core aspects of ISH, from its basic principle to its advanced applications and experimental protocols, providing a framework for evaluating its performance.

The Core Principle and Key Variations of ISH

The power of ISH lies in its ability to answer the question of "where" a specific genetic sequence is located. The basic principle involves fixing the target nucleic acids within their cellular context, applying a labeled probe that is complementary to the target sequence under specific hybridization conditions, and then detecting the location of the bound probe [1]. The main variations of the technique are distinguished by the type of target, the method of detection, and the probe design.

Primary ISH Methodologies

| Technique | Target | Detection Method | Primary Advantage | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CISH (Chromogenic ISH) | DNA or RNA | Chromogenic reaction, visualized with bright-field microscopy [3] | Ability to view signal and tissue morphology simultaneously with common microscopes; permanent slides [3] | Molecular pathology diagnostics [3] |

| FISH (Fluorescent ISH) | DNA or RNA | Fluorophores, visualized with fluorescence microscopy [3] | Multiplexing: ability to visualize multiple targets in the same sample [3] | Gene presence, copy number, location (DNA-FISH); gene expression and RNA localization (RNA-FISH) [3] |

| Branched DNA (bDNA) FISH (e.g., ViewRNA) | RNA (primarily) | Fluorophores with signal amplification, visualized with fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [1] [3] | High Sensitivity & Specificity: proprietary signal amplification reduces background and increases signal-to-noise ratio [1] [3] | Detection of low-abundance RNA transcripts; multiplex gene expression analysis [3] |

The following workflow outlines the general stages of a branched DNA FISH assay, a method known for its high sensitivity:

Essential Components: The ISH Toolkit

The successful execution of an ISH experiment relies on a set of key reagents and materials. The table below details these essential components and their functions.

Research Reagent Solutions for ISH

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Probes | Labeled, complementary nucleic acids (DNA, RNA, or oligonucleotides) that hybridize to the target sequence. Types include double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, RNA probes (riboprobes), and synthetic oligonucleotides (PNA, LNA) [2]. |

| Labels | Reporter molecules attached to the probe for detection. These can be radioactive isotopes (e.g., 32P, 35S) or non-radioactive labels like biotin, digoxigenin, or fluorescent dyes [2] [1]. |

| Fixatives | Chemicals like formaldehyde used to preserve tissue architecture and cross-link nucleic acids in place, preventing degradation and diffusion [1]. |

| Permeabilization Agents | Substances such as proteinase K that treat cells to open membranes, allowing probe access to the target nucleic acids [1]. |

| Hybridization Buffers | Solutions that control temperature, salt, and/or detergent concentration to ensure specific binding between the probe and its target [1]. |

| Detection Reagents | For non-fluorescent probes, these include enzyme-conjugated antibodies (e.g., anti-digoxigenin) that bind the probe label, followed by a chromogenic substrate to produce a visible precipitate [1]. |

| Signal Amplification System | In branched DNA FISH, a series of oligonucleotides (pre-amplifiers and amplifiers) that bind to the probe to create a tree-like structure, dramatically amplifying the signal [1] [3]. |

Detailed Methodologies: Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic ISH with Digoxigenin-Labeled Probes

This protocol outlines the key steps for a standard chromogenic or fluorescent ISH assay using a hapten-labeled probe [1].

- Sample Preparation: Tissue or cells are fixed, typically with a cross-linking fixative like formaldehyde, to preserve morphology and retain nucleic acids. For some samples, permeabilization with proteinase K is required to allow probe entry [1].

- Probe Hybridization: The labeled complementary DNA or RNA probe is applied to the sample and incubated at an elevated temperature optimized for specific hybridization. This step can take several hours or overnight [1].

- Stringency Washes: After hybridization, non-specifically bound probe is removed through a series of washes. Parameters like temperature, salt concentration, and detergent concentration are manipulated to ensure only perfectly matched sequences remain bound [1].

- Signal Detection:

- For hapten-labeled probes (e.g., digoxigenin), an antibody conjugate (e.g., an antibody linked to alkaline phosphatase) is applied and allowed to bind [1].

- For chromogenic detection, a substrate for the enzyme is added, which produces an insoluble, colored precipitate at the site of the target.

- For fluorescent detection, the antibody is conjugated to a fluorophore, or the probe is directly labeled with a fluorophore.

- Visualization and Analysis: The results are visualized via bright-field microscopy (for chromogenic detection) or fluorescence microscopy. Signal localization within the tissue context is then analyzed.

Protocol 2: Branched DNA (bDNA) Signal Amplification FISH

This method, used in technologies like ViewRNA, employs a multi-step hybridization process to achieve high sensitivity and is particularly suited for detecting low-abundance RNA targets [1] [3].

- Sample Preparation and Fixation: Cells or tissues are fixed to preserve RNA and morphology.

- Target Hybridization: A probe set containing approximately 20 to 40 oligonucleotide pairs is hybridized to the target RNA. These oligo pairs bind side-by-side along the target sequence [1].

- Signal Amplification (Pre-Amplification): A pre-amplifier molecule hybridizes to each pair of the bound oligonucleotides on the target-specific probe [1].

- Signal Amplification (Amplification): Multiple amplifier molecules hybridize to each pre-amplifier [1].

- Label Probe Hybridization: Finally, many label probes, conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (for chromogenic detection) or directly to fluorophores, hybridize to each amplifier molecule. This fully assembled "tree" structure can result in an 8,000-fold signal amplification for a single transcript [1].

- Detection: The signal is detected using fluorescence or bright-field microscopy. The use of independent but compatible signal amplification systems enables the multiplexing of several targets in a single assay [1] [3].

The logical relationship and workflow of the branched DNA signal amplification system is detailed below:

Applications and Quantitative Performance

ISH is a versatile technique with broad applications across biological research and clinical diagnostics. Its utility in sensitivity comparisons becomes clear when examining its use cases and performance metrics.

Key Application Areas of ISH

| Field | Specific Application |

|---|---|

| Microbiology | Morphology and population structure of microorganisms (classic target: 16S rRNA) [2]. |

| Pathology & Diagnostics | Pathogen profiling, assessment of abnormal gene expression, and HER2 testing in breast and gastro-oesophageal carcinoma [2] [4]. |

| Developmental Biology | Gene expression profiling in embryonic tissues [2]. |

| Cytogenetics | Karyotyping and phylogenetic analysis; detection of chromosomal aberrations and fusion genes via unique FISH patterns [2] [1]. |

| Genomic Mapping | Physical mapping of clones to specific chromosomal regions [2]. |

| Gene Expression Studies | Spatial and temporal localization of mRNA, lncRNA, and miRNA within tissues and cells [1] [3]. |

Quantitative Data on ISH Performance

Recent studies, particularly those focusing on automation, provide quantitative data relevant for sensitivity and efficiency comparisons.

Table: Automated vs. Manual FISH Performance Comparison Data from a 2025 validation study of the Leica BOND-III automated staining platform for HER2 FISH testing demonstrates key performance metrics [4].

| Metric | Automated FISH (Leica BOND-III) | Manual FISH (Agilent HER2 IQFISH) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Breast Cancer) | 95% | (Baseline) |

| Specificity (Breast Cancer) | 97% | (Baseline) |

| Sensitivity (Gastric Carcinoma) | 100% | (Baseline) |

| Specificity (Gastric Carcinoma) | 100% | (Baseline) |

| Overall Concordance | 98% | (Baseline) |

| Technical Hands-on Time | Significantly decreased | (Baseline) |

| Overall Supply Costs | Reduced | (Baseline) |

This empirical data shows that automated FISH platforms can achieve high diagnostic concordance with manual methods while improving laboratory efficiency and reducing costs, a critical consideration for clinical and research settings [4].

In situ hybridization stands as a critical technique for spatially resolving nucleic acid localization within a cellular context. From its foundational forms (CISH and FISH) to more sensitive, amplified versions (bDNA FISH), the core principle remains the hybridization of a complementary probe to an in-situ target. When framed within sensitivity comparison research, the choice of probe type, labeling method, and detection system—especially the use of sophisticated signal amplification technologies—becomes the defining factor for performance. The ongoing innovation in ISH, including automation and multiplexing, ensures its continued relevance in advancing both basic biological understanding and clinical diagnostic capabilities.

In situ hybridization (ISH) and immunostaining (including immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence) are cornerstone techniques for visualizing molecular targets within tissues and cells. While both methods preserve valuable spatial context lost in bulk analysis techniques, they operate on fundamentally different principles and target distinct molecules. Immunostaining uses antibodies to detect proteins (antigens), providing a snapshot of protein expression and localization [5] [6]. In contrast, ISH uses nucleic acid probes to hybridize to DNA or RNA sequences, revealing information about gene location, transcription, and genomic alterations [7] [6]. Understanding their comparative specificity, reliability, and applications is crucial for selecting the optimal method in research and diagnostics, particularly in sensitive areas like cancer and regenerative biology. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these two powerful techniques, framed within ongoing research aimed at enhancing the sensitivity of in situ hybridization.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

Core Mechanisms and Targets

The fundamental distinction lies in their detection targets and the chemistry employed. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Core Principles and Targets of Immunostaining and ISH

| Feature | Immunostaining (IHC/IF) | In Situ Hybridization (ISH) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | Proteins (antigens) [8] | Nucleic Acids (DNA, mRNA, miRNA) [8] [6] |

| Detection Molecule | Antibodies [5] [6] | Nucleic Acid Probes [7] [6] |

| Key Principle | Antigen-antibody binding [6] | Complementary base-pairing hybridization [6] |

| Visualization | Chromogenic (DAB) or Fluorescent tags [5] [6] | Chromogenic (DIG) or Fluorescent (FISH) tags [7] [6] |

| Information Gained | Protein expression, localization, post-translational modifications [5] | Gene expression, genetic aberrations, viral nucleic acids [7] [6] |

Workflow and Signal Detection

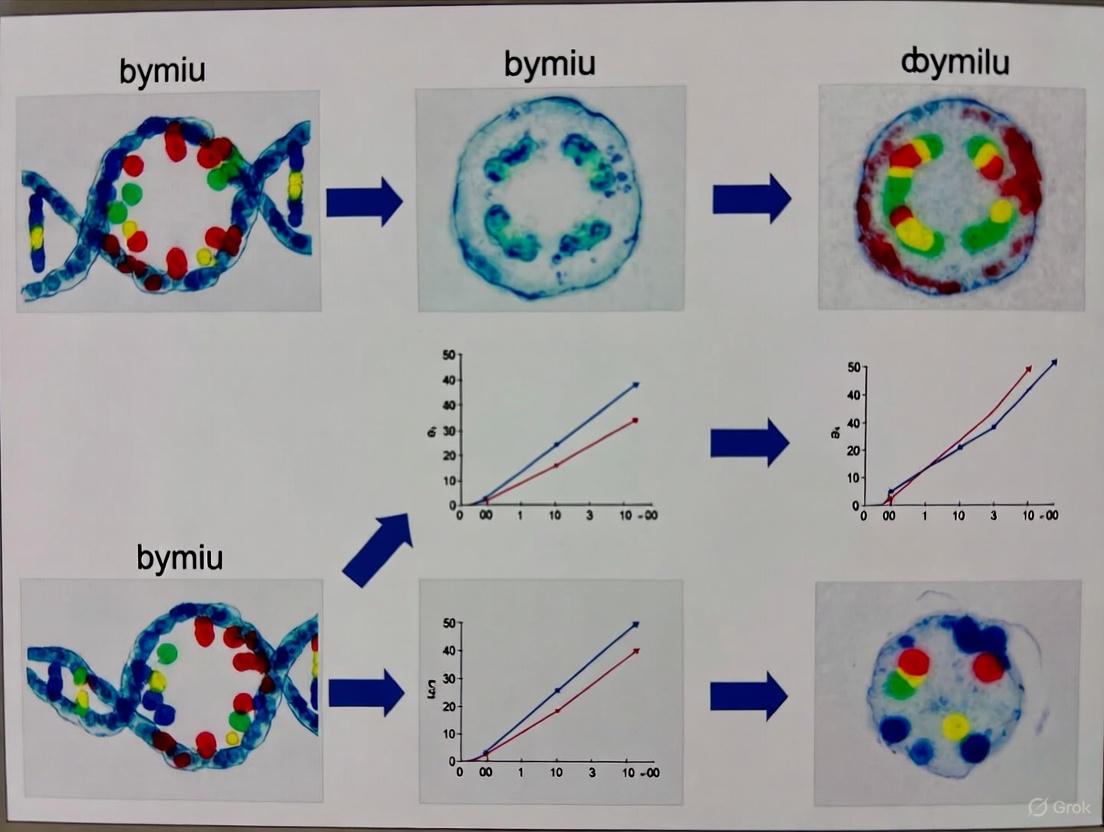

The experimental workflows for both techniques share common steps like fixation and permeabilization, but critical differences exist in pre-treatment and detection, which directly impact their specificity and reliability. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways for each method.

Diagram 1: Core signaling pathways for Immunostaining and ISH.

Specificity and Reliability: A Detailed Analysis

Factors Governing Specificity

Immunostaining Specificity: Specificity is almost entirely dependent on the affinity and specificity of the primary antibody used [7]. A well-validated antibody ensures minimal cross-reactivity with non-target proteins. However, antibodies can sometimes recognize proteins with similar epitopes, leading to false-positive results [7]. The method excels at determining the subcellular localization of a target protein (e.g., nuclear, cytoplasmic, membrane) [7].

ISH Specificity: Specificity is determined by the design of the nucleic acid probe, including its length, sequence composition, and hybridization conditions [7]. Probe specificity can be computationally predicted by checking the homology of its sequence with other genes in the relevant database [7] [9]. This reduces the risk of off-target binding and allows for the discrimination between highly homologous genes or different splice variants with careful probe design [7].

Assessing Reliability and Sensitivity

Reliability encompasses sensitivity, reproducibility, and robustness. Key differentiators are highlighted in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Reliability and Technical Performance

| Aspect | Immunostaining | In Situ Hybridization | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Highly dependent on antibody quality and titer [7]. | Can achieve single-molecule sensitivity with advanced methods (e.g., RNAscope) [8]. | ISH is often more reliable for low-abundance targets. |

| Target Validation | Probes can be designed from sequence data for any known gene, independent of species [7]. | Enables protein-level validation of transcriptomic hits [5]. | ISH is superior for novel targets or non-model organisms. |

| Reproducibility | Can be variable between different antibody batches and protocols [7]. | High reproducibility; probe performance is predictable from sequence [7]. | ISH generally offers more consistent results across labs. |

| Sample Preservation | Harsh protease treatments for ISH can destroy protein epitopes, reducing IHC reliability [10] [8]. | Proteinase K digestion can damage tissue morphology [10]. Newer methods (e.g., NAFA) avoid this [10]. | Method choice affects tissue integrity. |

| Clinical Performance | High specificity (e.g., 100% in biliary strictures), but can have low sensitivity (45.8%) [11]. | High sensitivity (84.2% for FISH in biliary strictures), but can have lower specificity (96.0%) [11]. | Combining both can optimize diagnostic accuracy [12] [11]. |

A clinical study on biliary strictures underscores this comparison, where cytology (a morphology-based method similar to IHC) showed 100% specificity but only 45.8% sensitivity, while FISH showed 84.2% sensitivity and 96.0% specificity, demonstrating the trade-offs between these approaches [11].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Advanced Immunostaining Protocol for Delicate Tissues

The NAFA (Nitric Acid/Formic Acid) fixation protocol is an advanced method designed for delicate tissues like regenerating planarians, offering superior preservation for both IHC and ISH [10].

- Fixation Solution: 4% formaldehyde in 1x PBS with 0.25% nitric acid and 2.5% formic acid.

- Key Additive: Includes EGTA, a calcium chelator, to inhibit nucleases and preserve RNA integrity during sample preparation [10].

- Critical Modification: Omits Proteinase K digestion, which is standard in many ISH protocols but damages protein epitopes and fragile tissue structures like the epidermis and blastema [10].

- Workflow: After fixation, samples are permeabilized and blocked. For IHC, they are incubated with primary and fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. For subsequent FISH, the protocol uses formic acid for permeabilization instead of proteases [10].

- Advantage: This protocol robustly preserves fragile external structures (e.g., cilia, epidermis) while allowing antibody and probe penetration, enabling high-quality tandem FISH and immunostaining [10].

High-Sensitivity RNA In Situ Hybridization Workflow

Advanced ISH methods like RNAscope and HCR FISH have significantly improved upon conventional ISH for detecting low-expression genes [7].

- Probe Design (Primary Probe): Use of multiple short, synthetic oligonucleotide probes targeting different regions of the same mRNA transcript. This increases the effective coverage and specificity without compromising tissue penetration [7].

- Signal Amplification (e.g., RNAscope): The primary probes contain tail sequences that serve as binding sites for pre-amplifier molecules. Multiple amplifier molecules then bind to each pre-amplifier, and each amplifier hybridizes with many labeled probes. This branched DNA (bDNA) technology creates a large signal amplification complex at each probe-binding site [8].

- Visualization: The labeled probes are detected using chromogenic (e.g., Fast Red, DAB) or fluorescent substrates. The signal appears as distinct dots, each representing a single mRNA molecule [7] [8].

- Key Advantage: This multi-step amplification allows for single-molecule sensitivity and low background, and the lack of a protease digestion step makes it more compatible with subsequent immunostaining [7] [8].

Application Scenarios and Integration

Distinct and Overlapping Applications

Each technique excels in specific scenarios, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 3: Key Application Scenarios for Immunostaining and ISH

| Application Domain | Immunostaining | In Situ Hybridization |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Diagnostics & Subtyping | HER2, ER/PR, PD-L1 testing for therapy guidance [5]. | HER2 gene amplification via FISH; detection of gene fusions [4] [6]. |

| Cell Type Identification | Profiling immune cells (CD3, CD20), astrocytes (GFAP) [5]. | Identifying cell types based on specific mRNA expression. |

| Neurobiology | Localizing amyloid-β plaques and tau tangles in Alzheimer's [5]. | Mapping neurotransmitter receptor mRNA expression [8]. |

| Regeneration Research | Visualizing mitotic cells (anti-H3P), muscle fibers (anti-6G10) [10]. | Analyzing gene expression patterns in stem cells (piwi-1) and blastemas [10]. |

| Infectious Disease | - | Detecting viral DNA/RNA (e.g., HPV) [6]. |

| Target Validation | Confirming protein-level expression of transcriptomic hits [5]. | - |

Integrated Workflows: Dual ISH-IHC

Combining ISH and IHC on the same tissue section provides a powerful multi-omics approach, revealing the relationship between gene expression and protein production within the same cell. However, standard protocols for each method are incompatible [8] [9].

- The Fundamental Conflict: The protease treatment required for ISH probe penetration destroys protein epitopes, damaging the IHC signal. Conversely, antibody reagents can introduce RNases that degrade the RNA target for ISH [8].

- Sequential Protocol with Critical Modifications:

- RNase Inhibition: Tissue sections are pretreated with recombinant ribonuclease inhibitors during the IHC antibody incubation to protect RNA integrity [8].

- IHC First: Perform immunostaining first using cross-linked or highly stable antibodies.

- Antibody Crosslinking: After IHC labeling, antibodies are crosslinked to the tissue using a fixative like formaldehyde. Standard fixation is insufficient to withstand the subsequent ISH pretreatments [8].

- ISH Second: Perform the ISH protocol, including its more stringent washes and hybridization steps. The crosslinked antibodies remain bound, preserving the protein signal.

- Outcome: This workflow allows for the robust dual detection of both protein and mRNA targets in the same tissue section, enabling sophisticated spatial biology analysis [8] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this powerful integrated approach.

Diagram 2: Sequential workflow for dual ISH-IHC detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of these techniques, especially their integration, relies on key reagents. The following table details essential components for the dual ISH-IHC protocol.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Dual ISH-IHC

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitor (e.g., RNaseOUT) | Protects RNA targets from degradation during IHC steps [8]. | Critical for preserving RNA integrity when using antibody reagents. |

| Antibody Crosslinker | Covalently binds antibodies to tissue post-IHC, preventing their dissociation during harsh ISH steps [8]. | Standard formaldehyde fixation is often insufficient. |

| Branched DNA (bDNA) ISH Probes (e.g., ViewRNA, RNAscope) | Enable high-sensitivity, multiplexed RNA detection without protease treatment [8] [9]. | Simplify combination with IHC and boost signal for low-expression genes. |

| Formic Acid / NAFA Fixative | Acts as a permeabilization agent for ISH, replacing Proteinase K to better preserve antigen epitopes [10]. | Enhances tissue integrity and compatibility with IHC. |

| Multiplex-Compatible Mountant | Preserves fluorescence and colorimetric signals, prevents photobleaching for archival [8]. | Essential for long-term storage and multi-channel imaging. |

| Spectral Imaging System | Simultaneously resolves multiple fluorescent signals from IHC and FISH with minimal crosstalk [8]. | Enables high-plex data acquisition from a single section. |

Immunostaining and ISH are complementary, not competing, technologies. Immunostaining is the established choice for protein localization and cell phenotyping when high-quality antibodies are available, offering excellent morphological context. ISH provides unparalleled specificity for nucleic acid detection, crucial for genetic aberrations, viral detection, and validating gene expression, especially in non-model organisms or for low-abundance transcripts.

The choice between them hinges on the research question: For "where is the protein?", use immunostaining. For "is the gene active and where?", use ISH. The future of spatial biology lies in their integration. Overcoming technical hurdles with optimized protocols like NAFA fixation and dual ISH-IHC enables true spatial multi-omics, allowing researchers to correlate transcriptional activity with translational output within the complex architecture of intact tissues. This powerful synergy promises to unlock deeper insights into development, disease mechanisms, and regenerative processes.

The journey of in situ hybridization (ISH) from a semi-quantitative morphological technique to a precise single-molecule detection platform represents one of the most significant advancements in molecular pathology and genetic research. This evolution has been driven by fundamental innovations in probe design, signal amplification methodologies, and detection systems that have collectively pushed the sensitivity boundaries of nucleic acid detection in morphologic contexts. This technical review examines the critical developmental pathway from conventional ISH to single-molecule resolution, with particular focus on the quantitative improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and spatial resolution that have transformed research capabilities and diagnostic applications. The progression mirrors a broader thesis in molecular detection: that achieving true single-molecule sensitivity requires not merely incremental improvements but fundamental reimagining of hybridization chemistry, amplification strategies, and visualization technologies.

In situ hybridization has undergone a remarkable transformation since its initial development in 1969, when the first demonstrations used radioactive probes to localize specific DNA sequences [13]. The evolution from these early radioactive methods to contemporary single-molecule detection platforms represents an increase in sensitivity of several orders of magnitude, enabling researchers to visualize and quantify individual nucleic acid molecules within their native cellular and tissue contexts. This enhanced sensitivity has proven particularly valuable in applications requiring detection of low-abundance transcripts, rare genetic variants, and subtle changes in gene expression that were previously undetectable with conventional methodologies.

The drive toward single-molecule sensitivity has been fueled by demands from multiple research domains. In cancer research, detecting rare genetic rearrangements or low-frequency mutations has prognostic and therapeutic implications. In developmental biology, understanding the spatial patterning of gene expression requires precise quantification of transcript localization. In drug development, tracking the distribution of therapeutic oligonucleotides necessitates highly sensitive detection methods [14]. These research needs have catalyzed the technical evolution chronicled in this review, establishing a new paradigm for what is detectable at the molecular level within intact biological systems.

The Historical Context: From Radioactive Probes to Basic Fluorescence

The initial phase of ISH evolution relied heavily on radioactive labeling techniques, which provided the first glimpse into chromosomal organization and gene localization but suffered from significant limitations. These early methods used radiolabeled RNA or DNA probes that required long exposure times (days to weeks) and offered limited spatial resolution due to scatter from radioactive emissions. Despite these constraints, radioactive ISH established the fundamental principle that nucleic acids could be localized within morphological contexts through complementary base pairing [14].

The first major transition in ISH technology came with the development of non-radioactive detection methods using fluorophores in the late 1970s [13]. This fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) approach offered several immediate advantages: reduced safety concerns, shorter processing times, and improved spatial resolution. However, early FISH methodologies remained relatively insensitive, capable of detecting only abundant targets such as repetitive DNA sequences or highly expressed genes. The limited brightness of fluorophores and absence of signal amplification strategies restricted applications to targets present in multiple copies per cell.

Table 1: Evolution of ISH Detection Methodologies

| Era | Probe Type | Signal Detection | Sensitivity Limit | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969-1980s | Radioactive DNA/RNA | Autoradiography | ~10-50 copies/cell | Gene localization, repetitive sequences |

| 1980s-1990s | Biotin/Digoxigenin | Enzyme-based chromogenic | ~5-20 copies/cell | Chromosome analysis, viral detection |

| 1990s-2000s | Directly labeled fluorescence | Epifluorescence microscopy | ~5-10 copies/cell | Karyotyping, gene amplification |

| 2000s-2010s | Oligonucleotide pools | Signal amplification (bDNA, TSA) | ~1-5 copies/cell | mRNA detection, gene fusion analysis |

| 2010s-Present | Multiplexed oligonucleotides | Single-molecule imaging | Single molecules | Spatial transcriptomics, low-abundance transcripts |

The critical limitation of these early fluorescence approaches was their fundamental sensitivity constraint. Without amplification, the signal from a single hybridized probe was insufficient to detect against cellular autofluorescence and background noise. This sensitivity barrier restricted FISH applications to targets present in multiple copies and prevented detection of single transcripts or precise quantification of gene expression at the cellular level.

The Signal Amplification Revolution: Bridging the Sensitivity Gap

The introduction of signal amplification strategies marked a pivotal transition in ISH technology, effectively bridging the gap between conventional detection and single-molecule sensitivity. These methodologies recognized that while the target nucleic acid could not be amplified in situ (as in PCR), the detection signal could be dramatically enhanced through various amplification cascades.

Branched DNA (bDNA) Technology

The branched DNA (bDNA) platform represents one of the most significant innovations in signal amplification for ISH. This approach uses a series of sequential hybridizations to build a complex amplification structure on the primary probe-target hybrid. The methodology typically involves:

- Primary probes that hybridize to the target RNA or DNA

- Preamplifier molecules that bind to the primary probes

- Amplifier molecules that bind to the preamplifiers in a branched configuration

- Labeled probes that hybridize to multiple sites on the amplifiers

This cascade results in an accumulation of thousands of fluorophores at the site of each original probe-target binding event, providing approximately 8,000-fold signal amplification [15]. The commercial implementation of this technology in platforms such as RNAscope and ViewRNA has enabled highly sensitive detection while maintaining specificity through a "double-Z" probe design that requires two independent probe binding events for signal generation [15].

Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)

Also known as catalyzed reporter deposition (CARD), tyramide signal amplification utilizes the catalytic activity of horseradish peroxidase to deposit numerous fluorescent or chromogenic tyramide molecules at the probe binding site. The enzyme is conjugated to a detector molecule that binds to the hybridized probe, and when exposed to hydrogen peroxide and tyramide substrates, the enzyme activates the tyramide molecules, causing them to form covalent bonds with nearby tyrosine residues. This results in substantial signal amplification, enabling detection of low-abundance targets [13].

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR)

HCR represents a more recent innovation in signal amplification that employs a series of metastable DNA hairpins that undergo a chain reaction of hybridization events initiated by the probe-target binding. This method provides exponential signal amplification while maintaining high specificity and low background, making it particularly suitable for multiplexed applications and whole-mount samples [14].

Diagram 1: Evolution of FISH sensitivity through probe design and signal amplification strategies. The transition from conventional FISH to single-molecule detection involved fundamental changes in both probe architecture and amplification methodologies, resulting in progressive improvements in sensitivity.

The Single-Molecule Revolution: smFISH and Beyond

The achievement of true single-molecule sensitivity represents the current apex of ISH evolution, enabled by the convergence of several technological innovations. Single-molecule FISH (smFISH) fundamentally transformed the capacity to detect and quantify RNA expression at the cellular level by providing absolute molecular counts rather than relative expression levels.

Fundamental Principles of smFISH

The core innovation of smFISH lies in the use of multiple short oligonucleotide probes (typically 17-22 base pairs) targeting different regions of the same transcript [16]. Each individual probe carries a single fluorophore, producing insufficient signal for detection against cellular background. However, when multiple probes (typically 20-96) hybridize to a single transcript, their collective signal generates a brightly fluorescent spot that can be easily detected by standard fluorescence microscopy [16]. Each bright spot corresponds to a single RNA molecule, enabling direct quantification of transcript abundance without amplification bias.

The statistical nature of this approach ensures high specificity, as false-positive signals from individual mis-bound probes are unlikely to co-localize. Raj et al. (2008) first demonstrated that this method could achieve true single-molecule resolution, fundamentally changing the landscape of gene expression analysis in situ [16].

Advanced smFISH Methodologies

Recent innovations have further enhanced the basic smFISH approach:

High-throughput multiplexed variations such as MERFISH (Multiplexed Error-Robust FISH) and seqFISH (sequential FISH) enable simultaneous detection of hundreds to thousands of different RNA species through combinatorial barcoding and sequential hybridization schemes [17]. These approaches maintain single-molecule sensitivity while dramatically expanding multiplexing capability.

Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) and Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) probes incorporate modified nucleic acid analogs that increase binding affinity and specificity, allowing for shorter probes and improved discrimination of single-nucleotide variants [18].

CRISPR-integrated systems such as the CRISPR FISHer platform have recently emerged, combining CRISPR-mediated target recognition with signal amplification for live-cell imaging of genomic loci [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of smFISH Methodologies

| Method | Probe Type | Probes per Transcript | Multiplexing Capacity | Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional smFISH | DNA oligonucleotides | 30-48 | 1-3 colors | Single molecules | Quantification of abundant transcripts |

| Branched DNA smFISH | Z-probe pairs | 10-20 pairs | 3-4 colors | Single molecules | Low-abundance transcripts, clinical samples |

| MERFISH/seqFISH | Barcoded oligonucleotides | 30-96 | 100-10,000 genes | Single molecules | Spatial transcriptomics, cell atlas |

| HCR-FISH | DNA initiators | 1-4 initiators | 5-10 colors | Single molecules | Whole-mount samples, thick tissues |

| LNA/PNA FISH | Modified nucleotides | 15-30 | 1-3 colors | Single molecules | Short transcripts, miRNA, SNP detection |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Implementing single-molecule FISH requires careful selection of reagents and methodologies optimized for specific applications. The following table summarizes key solutions and their functions in contemporary smFISH workflows.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Molecule FISH

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Design Platforms | Stellaris Designer, TrueProbes, MERFISH Designer | Computational probe selection and optimization | TrueProbes integrates genome-wide BLAST and thermodynamic modeling for enhanced specificity [19] |

| Probe Synthesis | Biosearch Technologies, IDT, GeneCopoeia | Custom oligonucleotide production | 5 nmol scale sufficient for hundreds of experiments; 3' amine modification for fluorophore coupling [16] |

| Fluorophores | Cy5, Alexa 594, Quasar 670, TMR | Signal generation | Cy5 and Alexa 594 provide optimal signal-to-noise; avoid shorter wavelengths (e.g., Alexa 488) due to autofluorescence [16] |

| Signal Amplification Systems | RNAscope, ViewRNA, HCR | Signal enhancement | RNAscope provides 8000-fold amplification via branched DNA [15] |

| Tissue Preparation | Neutral buffered formalin, paraformaldehyde | Tissue fixation and morphology preservation | 24±12 hours fixation optimal; under-fixation and over-fixation both detrimental to RNA integrity [14] |

| Permeabilization | Proteinase K, Triton X-100, Tween-20 | Tissue and cell permeability | Concentration and timing critical for probe accessibility while maintaining morphology [14] |

| Image Analysis Software | Spotiflow, Localize, FISH-quant | Automated spot detection and quantification | Spotiflow uses deep learning for subpixel-accurate detection in diverse image types [17] |

Experimental Protocol: smFISH for Single-Molecule Detection in Oocytes and Embryos

The following detailed protocol adapts smFISH for challenging samples, based on the optimized methodology described by [15] for use in murine oocytes and embryos. This protocol highlights the critical modifications required to achieve single-molecule sensitivity in delicate cellular contexts.

Probe Design and Synthesis (Days 1-2)

Design Parameters: Generate 17-22 base pair oligonucleotide probes targeting different regions of the transcript of interest. Ideal parameters include:

- GC content approximately 45% for uniform binding efficiency

- Minimum of 2 base pair spacing between adjacent probes

- 30-96 probes per transcript target for optimal signal-to-noise

- Include 3' amine group for fluorophore conjugation if synthesizing independently

Probe Synthesis and Coupling:

- Combine 1 nmol of each oligonucleotide in a single microcentrifuge tube

- Add 0.11 volumes of 1M sodium bicarbonate (pH 8.0) to achieve 0.1M final concentration

- Dissolve fluorophore (Cy5, Alexa 594, or TMR) in 50μL of 0.1M sodium bicarbonate

- For TMR, first dissolve in <5μL DMSO before adding bicarbonate

- Mix fluorophore solution with oligonucleotides and incubate overnight at room temperature with gentle rocking protected from light

Purification:

- Precipitate oligonucleotides by adding 10% volume 3M sodium acetate and 2.5 volumes 100% ethanol

- Store at -70°C for at least 1 hour (or overnight)

- Centrifuge at 16,000 RCF for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Remove supernatant and purify coupled probes via HPLC using C18 column with triethylammonium acetate (Buffer A) and acetonitrile (Buffer B) gradient

Sample Preparation and Fixation (Day 3)

Fixation:

- Transfer oocytes or embryos to drops of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS

- Fix for 30-60 minutes at room temperature

- Note: Commercial permeabilization buffers often cause lysis of delicate cells; replace with PBS-based buffers

Permeabilization:

- Wash samples 3×5 minutes in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20

- Permeabilize in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes

- Transfer to Agtech 6-well plates for subsequent steps to minimize sample loss

Hybridization and Signal Detection (Days 3-4)

Hybridization:

- Resuspend probe set in proprietary hybridization buffer (commercial buffers essential for preventing aggregation)

- Hybridize with transcript-specific probes overnight at 37°C

- Perform sequential hybridizations with pre-amplifier and amplifier molecules per manufacturer protocols

Washing and Imaging:

- Wash 3×10 minutes in PBS-based wash buffers

- Mount samples with anti-fade mounting medium

- Image using confocal microscopy with appropriate filter sets

- Acquire z-stacks through entire cell volume to ensure complete transcript capture

Data Analysis and Quantification

Image Processing:

- Use software such as Localize or Spotiflow for automated spot detection

- Apply background subtraction and flat-field correction

- Implement 3D spot detection for accurate counting throughout cell volume

Quantification:

- Each punctate fluorescent spot represents a single mRNA molecule

- Compare signal patterns across channels to exclude cross-talk

- Validate using negative controls (bacterial DapB gene) and positive controls (housekeeping genes)

Diagram 2: Workflow for single-molecule FISH experiments. The process involves four major phases: probe design and synthesis, sample preparation, hybridization and detection, and quantitative data analysis, with specific critical steps at each phase.

Technological Frontiers and Future Directions

The evolution of ISH sensitivity continues with several emerging technologies pushing the boundaries of what is detectable. Recent innovations focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities, improving quantitative accuracy, and expanding applications to new sample types.

Automated platforms such as the Leica BOND-III have demonstrated significant improvements in reproducibility and efficiency while maintaining sensitivity equivalent to manual methods. Studies show 98% concordance between automated and manual FISH with significant reduction in hands-on time and supply costs [4].

Digital PCR integration with single-molecule detection principles has enabled ultra-sensitive quantification of nucleic acids in solution. BEAMing (Bead, Emulsion, Amplification and Magnetics) technology achieves a limit of detection of 0.01%, an order of magnitude improvement over conventional digital PCR [20].

Spatial transcriptomics platforms represent the current cutting edge, combining single-molecule sensitivity with genome-scale multiplexing. Techniques such as Xenium In Situ and MERFISH enable mapping of hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously while maintaining subcellular resolution [17].

Computational probe design advances through platforms like TrueProbes integrate genome-wide BLAST analysis with thermodynamic modeling to optimize probe specificity and sensitivity. These tools address limitations in conventional design algorithms that struggle with short genes, low-abundance transcripts, and sequences with shared motifs [19].

The continued evolution of ISH sensitivity promises to further transform biological research and clinical diagnostics, enabling increasingly precise spatial and quantitative analysis of gene expression in the context of intact biological systems.

In situ hybridization (ISH) technologies have become indispensable tools in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the precise localization of nucleic acids within their native cellular and tissue contexts. The efficacy of these methods hinges on two fundamental metrics: signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which determines assay clarity and specificity, and detection limits, which define the minimum number of target molecules that can be reliably identified. This technical guide explores the core principles and experimental methodologies for quantifying these critical parameters across various ISH platforms, including RNAscope, HCR, Yn-situ, and U-FISH. By examining recent advancements in probe design, signal amplification, and computational analysis, we provide a framework for standardized sensitivity assessment that supports accurate comparison between methodologies and informs appropriate technique selection for specific research or diagnostic applications.

The sensitivity of any in situ hybridization assay is fundamentally governed by its ability to distinguish true signal from background noise across a range of target abundances. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) provides a quantitative measure of this distinction, calculated as the intensity of specific staining divided by non-specific background fluorescence or chromogenic precipitation. A higher SNR directly correlates with improved assay reliability, enabling more accurate target identification and quantification. Closely related is the concept of detection limits, which defines the lowest concentration of a target nucleic acid that can be reliably detected with statistical confidence. These parameters are influenced by multiple interconnected factors including probe design, signal amplification efficiency, tissue preservation, hybridization conditions, and detection methodology.

Recent innovations in ISH technologies have progressively pushed these sensitivity boundaries. Traditional single-molecule FISH (smFISH) methods typically required 20-50 probes targeting different regions of the same transcript to achieve robust detection. However, emerging methodologies like Yn-situ have demonstrated that sophisticated probe architecture can reduce this requirement to just 3-5 probes while maintaining or even improving sensitivity [21]. Similarly, the integration of deep learning approaches such as U-FISH has enabled significant enhancement of SNR in complex image data by transforming raw images with variable characteristics into enhanced images with uniform signal spots and improved signal-to-noise ratios [22]. Understanding how to quantify and compare these advancements requires standardized methodological approaches and metrics, which form the core focus of this technical guide.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ISH Methods and Analysis Tools

| Method / Tool | Key Innovation | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Detection Limit | Probe Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yn-situ [21] | Y-branched preamplifier with 20 initiator repeats | Higher SNR than HCR with 20-probe sets; smaller puncta | Detects RNA with just 3 probe pairs; works for short transcripts | 3-5 probe pairs (vs. 20 for standard HCR) |

| U-FISH [22] | Deep learning-based image enhancement | Superior signal enhancement; median F1 score: 0.924; distance error: 0.290 pixels | Enables detection in diverse imaging conditions & 3D data | Not applicable (post-imaging analysis) |

| RNAscope [23] | Proprietary probe design and amplification | 97.3% concordance with FISH in unequivocal cases; superior in heterogeneous samples | Single-molecule sensitivity at cellular level | Not specified in detail |

| QuantISH [24] | Computational framework for CISH analysis | Enables quantification in chromogenic ISH with single-channel data | Cell-type specific quantification in carcinoma, immune, and stromal cells | Not applicable (image analysis pipeline) |

The quantitative comparison of ISH methodologies reveals distinct approaches to optimizing sensitivity parameters. The Yn-situ method achieves its performance through a novel preamplifier design that creates a Y-shaped structure upon hybridization, with each preamplifier carrying 20 initiator repeats that simultaneously trigger 20 hybridization chain reactions [21]. This architecture produces a significant amplification cascade from minimal probe input, fundamentally altering the relationship between probe count and detection sensitivity. Experimental data demonstrates that while one probe pair produces detectable but weak signals unsuitable for quantitative studies, three probe pairs generate strong, quantifiable signals, and five probe pairs achieve optimal performance with high specificity and intensity [21].

Computational approaches offer a different pathway to sensitivity enhancement by operating on the output of various ISH methods rather than modifying the hybridization chemistry itself. U-FISH employs a U-Net model trained on a comprehensive dataset of over 4000 images and 1.6 million verified targets from seven diverse sources [22]. This approach transforms raw FISH images with variable characteristics into enhanced images with uniform signal spot characteristics, achieving a median F1 score of 0.924 and a distance error of just 0.290 pixels in benchmark analyses [22]. The method's compact architecture of only 163k parameters enables efficient processing while maintaining high accuracy, demonstrating particularly strong noise resistance capabilities in tests with simulated noise [22].

For chromogenic ISH (CISH) methods, where fluorescent multi-channel advantages are absent, the QuantISH pipeline addresses the significant analytical challenge of segmenting nuclei and quantifying signal from a single channel containing both marker and counterstain [24]. Through color deconvolution to separate brown marker RNA stain from blue nucleus stain, followed by sophisticated computational processing including void-filling using textural synthesis algorithms, this framework enables cell-type specific classification and expression quantification based on nuclear morphology [24]. This approach maintains sensitivity despite the constraints of chromogenic detection systems.

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Quantification

Yn-situ Assay Optimization and Sensitivity Determination

The Yn-situ protocol employs a systematic approach to sensitivity optimization beginning with probe design and validation. The core innovation centers on a single-strand DNA preamplifier approximately 1 kb long containing repetitive sequences that serve as initiation sites. To generate this probe, a plasmid containing the double-stranded preamplifier sequence is amplified using LongAmp Taq DNA polymerase (identified as optimal through comparative testing of five commercial polymerases), with optimal results achieved at 0.5 μM primer concentration and 0.05 ng/μL template concentration [21]. Following amplification, single-stranded preamplifier is produced through strandase digestion of the phosphorylated antisense strand, with completeness of digestion verified empirically through testing of reverse primers at varying positions.

Critical to the assay's sensitivity is an improved fixation protocol that incorporates 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) following standard formaldehyde fixation. This chemical modification crosslinks the phosphate groups of cellular RNA with amine groups from proteins, dramatically reducing RNA degradation and improving signal detection, particularly in suboptimal samples such as 6-month-old tissue stored at -80°C [21]. Hybridization conditions follow established HCR parameters but with significantly fewer probe pairs. Experimental determination of optimal preamplifier concentration identified 0.2 ng/μL as ideal, though signals can be detected at concentrations as low as 0.002 ng/μL [21]. To reduce potential background from PCR handle sequences in the preamplifier, short oligos corresponding to these sequences are used at 10 times the preamplifier concentration as blocking reagents.

Sensitivity limits were quantitatively determined through systematic reduction of probe pairs. Experiments demonstrated that strong, quantifiable signals are achieved with three probe pairs, while one pair produces detectable but weak signals unsuitable for rigorous quantification [21]. This establishes the practical detection limit for the method while highlighting the relationship between probe number and signal intensity. The high sensitivity and wide dynamic range of Yn-situ further enables quantification of genes expressed at different levels, as demonstrated in olfactory sensory neurons [21].

U-FISH Image Enhancement and Analysis Protocol

The U-FISH methodology employs a deep learning approach to sensitivity enhancement that begins with comprehensive dataset preparation. The model was trained on a meticulously curated collection comprising over 4000 images with more than 1.6 million verified targets from seven diverse sources, ensuring broad generalizability across different experimental conditions and biological samples [22]. This dataset diversity is a cornerstone feature that enables the development of a universal spot detection model capable of consistent performance without dataset-specific parameter adjustments.

The U-Net architecture underlying U-FISH contains only 163k parameters, making it computationally efficient while maintaining high accuracy [22]. The network transforms raw FISH images with variable characteristics into enhanced images with uniform signal spot characteristics and improved signal-to-noise ratio. This enhanced output enables reliable spot detection with fixed parameters, eliminating the need for time-consuming manual adjustment for each image. Benchmark testing against both deep learning-based (deepBlink, DetNet, SpotLearn) and rule-based (Big-FISH, RS-FISH, Starfish, TrackMate) methods demonstrated U-FISH's superior performance across diverse datasets, with particular advantages in processing 3D FISH data through an innovative approach that enables a 2D network to effectively handle 3D data [22].

For experimental validation, the sensitivity and specificity of U-FISH were quantified using F1 scores and distance errors on test datasets. The method achieved a median F1 score of approximately 0.924, surpassing deepBlink (F1: 0.901), DetNet (F1: 0.886), SpotLearn (F1: 0.910), and rule-based methods [22]. The distance error of 0.290 pixels further confirmed its high precision in spot localization. Additional tests on datasets with simulated noise revealed strong noise resistance capabilities, highlighting its suitability for analyzing FISH images under various experimental conditions [22].

Signal-to-Noise Optimization in Chromogenic ISH

For chromogenic ISH methods, the QuantISH pipeline employs specific preprocessing steps to maximize sensitivity despite the limitations of single-channel detection. The process begins with extraction of contiguous images from tiled microscope scans, typically in MIRAX (MRXS) format from digital slide scanners with 40x magnification [24]. Individual tissue microarray spots are cropped using a module based on the HistoCrop method, followed by color deconvolution using the ImageJ software to separate brown marker RNA stain from blue nucleus stain [24].

A critical sensitivity-enhancing step involves cleaning demultiplexing artifacts through void-filling using a resynthesizer textural synthesis plug-in for GIMP software based on an algorithm that performs best-fit texture synthesis on user-specified regions of interest [24]. This process mitigates the effect of voids in the demultiplexed nucleus staining caused by overlapping signals in RNA-CISH images, enabling more accurate cell segmentation. The void-filled nucleus signal and demultiplexed marker RNA signal are then used in subsequent analysis steps.

Cell segmentation employs CellProfiler software with RescaleIntensity and IdentifyPrimaryObjects components, using Otsu's method with adaptive thresholding [24]. Non-default parameters were determined experimentally through multiple iterations: object diameter 25 to 170 pixels, and threshold smoothing scale of 1.3488. Cell type classification follows, based on nuclear morphology features extracted from the filtered nucleus channel and its segmentation, enabling cell-type specific expression quantification even without separate fluorescent channels for different cell types [24].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Yn-situ Probe Hybridization and Amplification

Yn-situ Signal Amplification Pathway - This diagram illustrates the cascade of molecular interactions in the Yn-situ method that enable high-sensitivity RNA detection with minimal probes, culminating in significantly improved signal-to-noise ratio.

U-FISH Computational Enhancement Workflow

U-FISH Computational Enhancement Workflow - This workflow diagrams the transformation of variable-quality raw images into standardized enhanced outputs through deep learning, enabling consistent spot detection without manual parameter adjustment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Sensitive ISH Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Sensitivity Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | LongAmp Taq DNA Polymerase, KAPA HiFi DNA Polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplification of preamplifier probes with high yield and specificity; critical for Yn-situ probe production [21] |

| Fixation Reagents | Formaldehyde, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), PBS | Tissue preservation and RNA crosslinking; EDC significantly reduces RNA degradation, improving signal in stored samples [21] |

| Detection Systems | DAB, AEC, NBT/BCIP, Fast Red, Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) | Chromogenic or fluorescent signal generation and amplification; TSA enables detection of low-abundance targets [25] |

| Hybridization Buffers | SSC buffer, PBST with Tween 20, Prehybridization buffers | Control of stringency conditions; precise temperature and buffer composition critical for signal-to-noise optimization [25] |

| Enzymes | Pepsin, Strandase, Restriction enzymes (SfiI), HRP, Alkaline phosphatase | Tissue permeabilization, probe generation, and signal detection; pepsin digestion time must be optimized for each tissue type [21] [25] |

| Computational Tools | U-FISH, QuantISH, CellProfiler, ImageJ | Image analysis, spot detection, and quantification; deep learning methods enhance signal-to-noise post-acquisition [22] [24] |

The selection and optimization of research reagents directly impacts the achievable sensitivity of ISH experiments. For probe-based amplification methods like Yn-situ, the choice of DNA polymerase significantly affects preamplifier production. Comparative testing of five commercial polymerases identified LongAmp Taq DNA Polymerase as providing the highest yield of the desired 1 kb product, a critical factor in assay consistency [21]. For detection systems, the matching of enzyme conjugates with appropriate substrates is essential - HRP should be used with DAB and AEC, while alkaline phosphatase pairs with NBT/BCIP and Fast Red [25]. Mismatched combinations result in failed experiments regardless of target abundance.

Fixation protocols represent another crucial sensitivity determinant. While standard formaldehyde fixation preserves tissue architecture, the addition of EDC crosslinking dramatically improves signal detection in challenging samples by covalently linking RNA phosphate groups to protein amines, effectively immobilizing targets and reducing degradation [21]. This is particularly valuable for archival tissues or samples with partial RNA degradation. Enzymatic permeabilization using pepsin requires careful optimization, with typical digestion times of 3-10 minutes at 37°C, but must be adjusted for specific tissue types - over-digestion weakens or eliminates signal, while under-digestion decreases hybridization efficiency [25].

Computational reagents in the form of software tools and algorithms have emerged as essential components in modern ISH sensitivity optimization. The U-FISH platform, with its compact 163k parameter architecture, demonstrates how specialized computational tools can enhance signal-to-noise ratio post-acquisition, achieving a median F1 score of 0.924 in benchmark tests [22]. Similarly, the QuantISH pipeline enables sensitivity extraction from chromogenic ISH images through sophisticated color deconvolution and segmentation algorithms that would be impossible through visual assessment alone [24]. These tools effectively extend the detection limits of established laboratory methods through computational means.

The continuous refinement of in situ hybridization technologies has progressively lowered detection limits while improving signal-to-noise ratios through innovations in probe design, amplification strategies, and computational analysis. The quantitative framework presented here establishes standardized metrics and methodologies for sensitivity assessment that enable direct comparison across platforms and experimental conditions. As ISH applications expand into increasingly challenging domains including low-abundance targets, spatially resolved transcriptomics, and clinical diagnostics, rigorous attention to these fundamental sensitivity parameters becomes essential for methodological validation and appropriate technique selection. The integration of computational enhancement with biochemical amplification represents a particularly promising direction, offering complementary pathways to overcome the inherent limitations of each approach individually. By establishing clear metrics and standardized assessment protocols, the field can advance more rapidly toward the ultimate goal of comprehensive, quantitative spatial mapping of nucleic acids with single-molecule sensitivity across diverse biological contexts.

High-Sensitivity ISH Methods: Protocols, Costs, and Practical Applications

In molecular pathology, diagnostics, and research, the ability to evaluate gene expression within its native tissue context is invaluable. Traditional RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) techniques have often been hampered by technical complexity, insufficient sensitivity, and high background noise, limiting their clinical and research utility [26]. Similarly, while immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a popular alternative, it depends on the availability of specific antibodies, which can be expensive, time-consuming to develop, and sometimes impossible to create for species other than human, rat, and mouse [27]. Grind-and-bind methods like PCR, though useful, sacrifice all spatial and morphological context [27]. To solve these persistent problems, Advanced Cell Diagnostics (ACD) developed the RNAscope platform—an advanced ISH technology that combines single-molecule sensitivity with high specificity in a format amenable to automation, thereby enabling simplified and robust workflows for researchers and drug development professionals [27] [26].

Core Technology: The RNAscope Platform and Its Mechanism

The RNAscope technology represents a significant evolution in RNA ISH. Its foundational innovation is a proprietary double Z (ZZ) probe design that enables simultaneous signal amplification and background suppression, allowing for single-molecule visualization while preserving tissue morphology [26].

The Double Z Probe Design and Signal Amplification

The high performance of RNAscope stems from its unique probe architecture and amplification cascade, detailed below and illustrated in Figure 1.

dot code block

Figure 1. RNAscope Signal Amplification Mechanism. The diagram illustrates the proprietary double Z probe design and subsequent hybridization steps that enable specific signal amplification, resulting in a detectable dot for each target RNA molecule.

The process functions as follows:

- Probe Hybridization: Each target RNA molecule is hybridized by 20 double Z probe pairs on average [28]. A minimum of 7 Z pairs is required to generate a signal [29]. The double Z probe consists of three regions: a lower region that hybridizes to the target RNA, a spacer sequence, and a tail that binds to the pre-amplifier [28].

- Signal Amplification Cascade: The binding of the pre-amplifier to the Z probe tails initiates a multi-stage amplification process. Each pre-amplifier subsequently binds to multiple amplifier molecules, which in turn are conjugated with numerous labeled probes (either chromogenic or fluorescent) [28]. This cascade can result in up to 8,000-fold signal amplification, as approximately 400 labeled probes attach to each dimer [28].

- Detection: The final output is visualized as a distinct punctate dot, where each dot corresponds to a single RNA transcript [30]. The intensity or size of a dot can vary based on the number of ZZ probes bound to the target molecule, but the critical quantitative factor is the number of dots, not their size [30].

Assay Portfolio: RNAscope, BaseScope, and miRNAscope

ACD's technology suite includes three complementary assays tailored for different RNA targets, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of ACD's RNAscope Technology Assays

| Feature | RNAscope Assay | BaseScope Assay | miRNAscope Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZZ Pairs per Target | 20 (minimum of 7) [29] | 1 to 3 [29] | N/A (Unique probe design) [29] |

| Target Molecules | mRNA & lncRNA >300 bases [29] | Short targets (50-300 bases), exon junctions, splice variants, point mutations [29] | Small RNAs (17-50 bases) including miRNAs, ASOs, siRNAs [29] |

| Multiplex Capability | Single-plex up to 12-plex [29] | Single-plex to Duplex [29] | Single-plex [29] |

| Primary Application | Detection of long RNA transcripts [29] | Detection of short sequences, splice variants, and genetic mutations [29] | Detection of small non-coding RNAs [29] |

Implementing Simplified and Automated Workflows

A key advantage of the RNAscope platform is its compatibility with automated instrumentation, which standardizes the staining process, reduces manual hands-on time, and improves reproducibility.

Standardized Workflow Steps

The RNAscope procedure involves a series of standardized steps, whether performed manually or on an automated system. The entire workflow, from sample preparation to analysis, is depicted in Figure 2.

dot code block

Figure 2. RNAscope Automated Workflow. The process flows from sample preparation through pretreatment, hybridization, and finally to visualization and analysis, and is compatible with automated platforms like the Leica Bond Rx.

- Sample Preparation: The assay is compatible with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, fresh frozen tissues, and cultured cells [28]. For FFPE samples, tissue fixation and processing are critical first steps.

- Pretreatment and Permeabilization: Slides are subjected to a universal pretreatment to expose target RNA sequences and permeabilize the tissue, allowing probe access [29] [28].

- Hybridization and Amplification: Target-specific probes are hybridized, followed by the sequential amplification steps. These key steps can be fully automated on instruments like the Leica Bond Rx and Roche Discovery ULTRA [28].

- Visualization and Imaging: Results can be visualized using a standard bright-field microscope for chromogenic dyes or an epifluorescent/confocal microscope for fluorescent assays [30].

- Analysis: Quantification is performed by counting the punctate dots, each representing an individual RNA transcript. This can be done manually or using image analysis software like HALO, QuPath, or Aperio [30] [28].

Performance and Validation Data

Independent studies and systematic reviews have validated the performance of RNAscope against established gold standard methods, confirming its place in modern research and diagnostic development.

Sensitivity and Specificity Compared to Gold Standard Methods

A 2021 systematic review comparing RNAscope to techniques like IHC, qPCR, and DNA ISH in human samples confirmed that RNAscope is a highly sensitive and specific method [28]. The review, which included 27 retrospective studies, found a high concordance rate (CR) between RNAscope and PCR-based methods (qPCR and qRT-PCR) and DNA ISH, ranging from 81.8% to 100% [28]. Its concordance with IHC was lower (58.7% to 95.3%), which is expected given that the two techniques measure different biomolecules (RNA vs. protein) that may not always correlate perfectly due to post-transcriptional regulation [28].

Performance in Challenging Sample Types

The robustness of RNAscope is demonstrated by its application on demanding sample types. A 2025 study successfully employed the miRNAscope assay on FFPE human brain samples stored for up to 76 years [31]. The combination of Nanostring nCounter profiling for candidate selection followed by miRNAscope ISH enabled the spatial detection of specific miRNAs like miR-124-3p in these decades-old samples, opening avenues for investigating epigenetic mechanisms in historical collections [31].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics of RNAscope Technology

| Metric | Performance Data | Context / Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Single-molecule sensitivity [32] [26] | Capable of detecting individual RNA transcripts |

| Specificity | High specificity due to double-Z probe design [28] | Suppresses background noise; off-target binding is unlikely |

| Concordance with qPCR/qRT-PCR | 81.8% - 100% [28] | High agreement with quantitative PCR methods |

| Detection Efficiency | Similar to other sensitive ISH-based commercial SRT platforms [33] | Independent analysis shows performance matches other top platforms |

| Application in Old Archives | Successful detection in 76-year-old FFPE samples [31] | Validates use in long-term stored, challenging samples |

A Practical Guide to Data Analysis and Interpretation

A significant strength of the RNAscope assay is that its output—discrete dots corresponding to individual RNA molecules—lends itself to both semi-quantitative and quantitative analysis [34]. The analysis approach should be tailored to the biological question and expression pattern.

Controls and Sample Qualification

Before analyzing target probe data, it is crucial to review control slides. ACD recommends running a minimum of three slides per sample: the target marker panel, a positive control, and a negative control probe [30].

- Positive Control (e.g., PPIB, Polr2A, UBC): Validates tissue RNA integrity and successful assay execution. Failure indicates RNA degradation or technical issues [28] [33].

- Negative Control (bacterial dapB gene): Confirms the absence of background noise and non-specific signal [30] [28].

Analysis Methodologies for Different Expression Scenarios

The RNAscope analysis guide outlines several common expression scenarios and appropriate methodologies for each [34]:

- Homogeneous Target Expression: When a cell population shows uniform staining, the overall expression level can be reported as the average number of dots per cell using semi-quantitative scoring or image analysis software [34].

- Heterogeneous Target Expression: When cells within a population display different expression levels, the dynamic range should be quantified. Cell-by-cell expression profiles can be binned, and data can be presented as a histogram or calculated as a Histo score (H-score). The H-score is calculated as: H-score = Σ (ACD score x percentage of cells per bin), providing a value from 0 to 400 [34].

- Target Expression in Multiple Cell Types or Subpopulations: In this case, each cell type or region of interest should be analyzed independently according to the methodologies above [34].

- Co-expression of Two Targets: To determine the percentage of cells co-expressing two genes, quantitative software analysis is used to count the number of cells positive for both Target 1 and Target 2 divided by the total number of cells [34].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing the RNAscope workflow effectively requires a set of core reagents and tools. The following toolkit is essential for researchers.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNAscope Workflows

| Item | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNAscope Probe Sets | Target-specific detection; hybridize to RNA of interest | Probes for >20,000 targets in multiple species; available in chromogenic or fluorescent formats [27] |

| RNAscope Reagent Kit | Contains reagents for pretreatment, hybridization, amplification, and detection | Kit components are specific to each assay type (e.g., RNAscope, BaseScope) and cannot be interchanged [29] |

| Positive Control Probes | Verify tissue RNA integrity and assay performance | PPIB (moderate expression), Polr2A (low expression), UBC (high expression) [28] [33] |

| Negative Control Probe | Assess background noise and non-specific binding | Bacterial dapB gene; should not produce signal in animal tissues [30] [28] |

| Automation Platform | Standardize staining, improve reproducibility, enable high-throughput | Compatible with Leica Bond Rx and Roche Discovery ULTRA automated stainers [28] |

| Image Analysis Software | Quantify dot counts and perform cell-based or region-based analysis | HALO (Indica Labs), QuPath, Aperio; enables quantitative, high-throughput data extraction [30] [28] |

RNAscope technology, with its innovative double Z probe design, has established a new standard for sensitive and specific in situ RNA analysis. Its compatibility with automated platforms translates this powerful detection capability into a simplified, reproducible workflow that is accessible for both research and clinical diagnostic development. As the field moves towards greater integration of AI-driven image analysis and expanded multiplexing capabilities, RNAscope and related commercial ISH platforms are poised to remain at the forefront of spatial biology, enabling deeper insights into gene expression within the native tissue architecture [35].

Spatial transcriptomics has revolutionized biological research by enabling precise mapping of gene expression within intact tissues and cells. The sensitivity and specificity of in situ hybridization (ISH) techniques are paramount for detecting low-abundance RNAs, short transcripts, and achieving single-molecule resolution. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of three powerful ISH methods—Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR), Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction (SABER FISH), and click-amplifying FISH (clampFISH)—focusing on their customization potential for diverse research applications. We evaluate their performance characteristics, detailed experimental protocols, and reagent requirements to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing these methods for enhanced spatial RNA detection.

Advanced in situ hybridization techniques employ enzyme-free amplification to achieve high sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities while preserving tissue morphology. The core principle involves using DNA probes that bind to target RNAs and initiate localized signal amplification cascades.

- Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) utilizes metastable DNA hairpins that undergo a triggered, self-assembly process upon binding to an initiator sequence attached to the target probe. This results in the formation of a long, nicked double helix that tethers numerous fluorophores, providing linear signal amplification [36] [37].

- SABER FISH (Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction) employs Primer Exchange Reaction (PER) to synthesize long, single-stranded DNA concatemers in vitro, which are appended to the primary target probes. These concatemers serve as scaffolds for hybridizing multiple fluorescent "imager" strands, significantly boosting the signal per probe [38] [39].

- clampFISH uses "C"-shaped probes that hybridize adjacently on the target RNA. These probes are then ligated via click chemistry, forming a stable circularized complex. This complex can withstand stringent washes and serves as a template for exponential signal amplification through successive hybridization of fluorescent secondary and tertiary probes [40].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of HCR, SABER FISH, and clampFISH

| Performance Metric | HCR v3.0 | HCR-Cat (Next-Gen) | SABER FISH | clampFISH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplification Type | Linear | Catalytic (Linear + Enzymatic) | Linear (concatemer-based) | Exponential (multi-round) |

| Typical Signal Gain | Baseline | ~240-fold (vs. HCR v3.0) [36] | Customizable (via concatemer length) [38] | ~1.74-fold per amplification round [40] |

| Probe Requirement for Detection | Multiple (e.g., 8-20) [36] | Can work with a single probe pair [36] | 15-30 short oligonucleotides [38] | Not specified |

| Short RNA Detection Capability | Limited for very short targets | Enabled via catalytic deposition [36] | Enabled via concatemer amplification [38] | Not specified |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (orthogonal hairpins) [36] | High (combined with immuno-detection) [36] | High (orthogonal concatemers + DNA exchange imaging) [39] | High (sequential rounds) [40] |

| Nuclear RNA/Transcription Site Detection | Challenging, lower contrast [40] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Excellent with nuclampFISH variant [40] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism and customization workflow for each method.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Next-Generation HCR for Challenging Targets in Thick Tissues

Application: Robust detection of short or low-abundance RNA targets in whole-mount zebrafish, mouse brain, and Drosophila tissues with high autofluorescence [36].

Detailed Protocol:

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix samples (e.g., 5 dpf larval zebrafish) with 4% PFA. For thick tissues, perform permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 24-48 hours.

- Hybridization: Hybridize split-initiator probe sets (e.g., 8 probes for hcrt mRNA) in a standard hybridization buffer (e.g., 30% formamide, 5x SSC) at 37°C for 12-36 hours.

- HCR v3.0 Amplification (Baseline): Wash off excess probes and amplify with fluorophore-labeled HCR hairpins (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes) in amplification buffer at room temperature for 12-24 hours.

- HCR-Cat Enhancement: a. Instead of fluorophores, use HCR hairpins conjugated to haptens like FITC or Digoxigenin (DIG). b. After HCR amplification, incubate samples with an HRP-conjugated anti-FITC or anti-DIG antibody. c. Catalytically deposit fluorescent tyramide (e.g., Cy3- or Cy5-tyramide) for 10-30 minutes to achieve ~240-fold signal increase.

- Imaging: Clear samples using PACT or iDISCO+ methods for deep tissue imaging. Image using confocal or light-sheet microscopy.

SABER FISH for a Unified and Multiplexed Platform

Application: A "one probe fits all" approach for multiplexed RNA detection in whole-mount flatworms (Macrostomum lignano), planarians, and FFPE mouse intestinal sections [38].

Detailed Protocol: