ISH Probe Labeling Techniques: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This article provides a thorough evaluation of in situ hybridization (ISH) probe labeling techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

ISH Probe Labeling Techniques: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a thorough evaluation of in situ hybridization (ISH) probe labeling techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of probe chemistry and label selection, details methodological applications across various research and diagnostic scenarios, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common experimental challenges, and discusses validation frameworks and comparative analyses of emerging technologies. The synthesis of these core intents delivers a critical resource for selecting, implementing, and validating optimal ISH probe labeling strategies to enhance accuracy and reliability in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

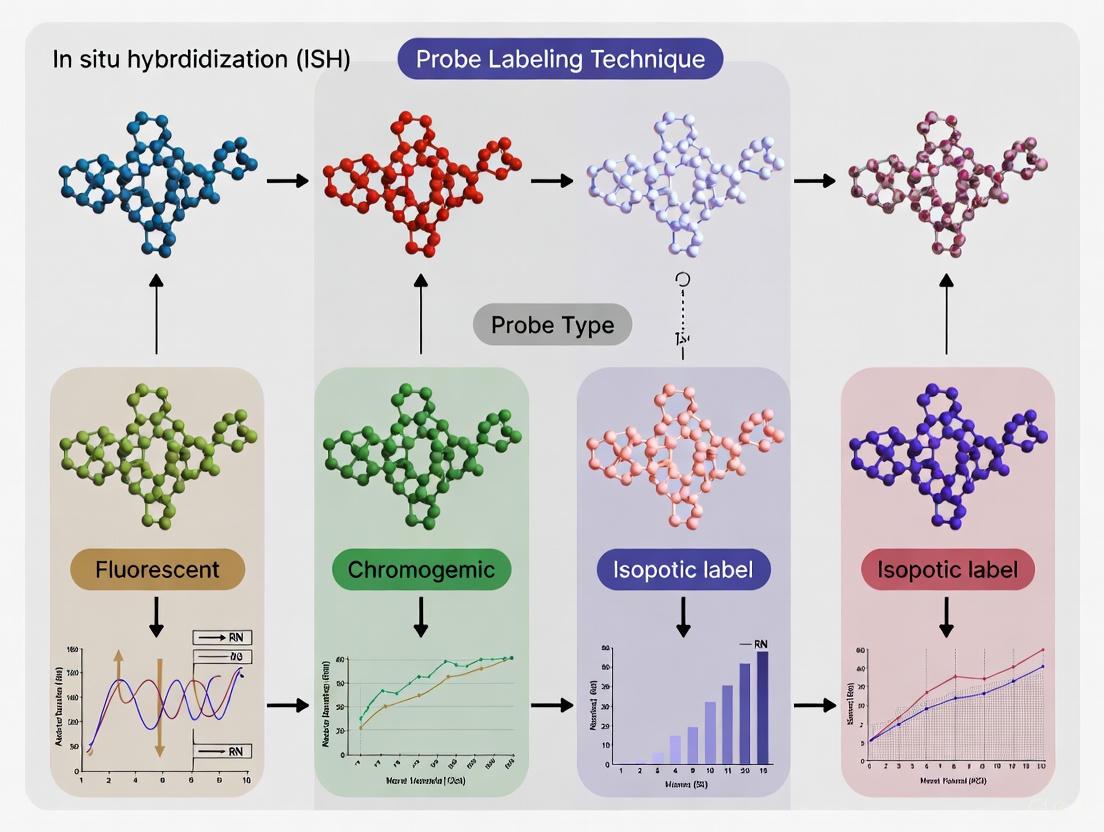

The Building Blocks of ISH: Understanding Probe Chemistry and Label Selection

In situ hybridization (ISH) has undergone a remarkable transformation since its initial development, evolving from a technically challenging procedure reliant on radioactive isotopes to a versatile toolkit of chromogenic and fluorescent methods that enable precise spatial localization of nucleic acids within tissues and cells. The technique was first described in 1969 when Gall and Pardue introduced radioactive ISH using tritium-labelled RNA to visualize ribosomal RNA hybridization in Xenopus oocytes [1] [2]. This pioneering work established the fundamental principle of hybridizing labeled nucleic acid probes to complementary sequences within biological specimens, but the method faced significant limitations including safety hazards, limited resolution, and lengthy exposure times.

The subsequent development of non-radioactive probe labeling in 1981, particularly with haptens like biotin detected by avidin-fluorochrome conjugates, marked a critical turning point that eventually enabled the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques widely used today [1]. This evolution has continued with the refinement of chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH), which offers the advantage of conventional bright-field microscopy while maintaining the capability to detect gene amplification and chromosomal translocations [3] [4]. The ongoing innovation in ISH technologies provides researchers and clinicians with an expanding arsenal of tools for investigating gene expression, chromosomal abnormalities, and viral infections within their morphological context.

Radioactive Isotope Labeling

The earliest ISH methodologies employed radioactive isotopes such as ³²P or ³⁵S, which provided high sensitivity but introduced significant handling complexities and safety concerns [5]. While this approach demonstrated the fundamental feasibility of in situ nucleic acid detection, the practical limitations restricted its widespread adoption in routine laboratories. The requirement for specialized facilities for radioactive material handling, lengthy exposure times, and limited spatial resolution prompted the search for alternative labeling strategies that would eventually revolutionize the field.

Fluorescent Labeling

Fluorescent labeling represents one of the most significant advancements in ISH technology, forming the basis for FISH. This method utilizes fluorochrome-conjugated probes with molecules such as Fluorescein, Cy3, Cy5, SpectrumGreen, SpectrumOrange, and Texas Red [1] [5]. FISH provides several distinct advantages: exceptional sensitivity, capacity for multicolor detection enabling the visualization of multiple targets simultaneously, technical straightforwardness, and compatibility with automated systems for high-throughput applications [5].

The limitations of fluorescent labeling primarily include photobleaching, where fluorescent signals diminish over time with light exposure, potentially affecting the long-term preservation and re-evaluation of samples [5]. Despite this limitation, FISH has become indispensable in both research and clinical diagnostics, particularly for characterizing chromosomal rearrangements in congenital diseases and malignancies [1]. The technique's versatility is evidenced by its adaptation to various applications including metaphase and interphase FISH, fiber-FISH, RNA-FISH, 3D-FISH, and immuno-FISH [5].

Chromogenic Labeling (CISH)

Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) emerged as a powerful alternative that combines the genetic detection capabilities of FISH with the practical advantages of conventional bright-field microscopy. Developed to address the limitations of fluorescence microscopy requirements in routine diagnostic laboratories, CISH utilizes enzyme-based detection systems (typically peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase) with chromogenic substrates like diaminobenzidine (DAB) or Fast Red [3] [2].

In a seminal 2000 study evaluating CISH for HER-2/neu oncogene amplification in breast cancer, researchers found that the method enabled easy discrimination of gene copies using a standard ×40 objective in hematoxylin-stained tissue sections [3]. HER-2/neu amplification typically appeared as "large peroxidase-positive intranuclear gene copy clusters" [3]. The study demonstrated excellent correlation between CISH and FISH (kappa coefficient of 0.81) across 157 breast cancers, establishing CISH as a valuable method for confirming immunohistochemical staining results, particularly in paraffin-embedded tumor samples [3].

Hapten-Based Labeling Methods

Biotin Labeling

Biotin labeling employs the strong interaction between biotin and streptavidin or avidin, typically conjugated to enzymatic reporters for signal generation. This method offers high sensitivity and specificity but requires careful validation due to potential interference from endogenous biotin present in some tissues [5]. The system allows for significant signal amplification through enzyme-substrate reactions, making it suitable for targets with lower abundance.

Digoxigenin (DIG) Labeling

Digoxigenin labeling, derived from a plant steroid molecule, provides an alternative hapten-based approach that minimizes background interference from endogenous biotin [5] [2]. DIG-labeled probes are detected using specific anti-DIG antibodies conjugated to fluorescent tags or enzymes, resulting in high sensitivity with reduced nonspecific signal. This method has proven particularly effective in viral detection studies, where self-designed DIG-labeled RNA probes successfully identified Schmallenberg virus in goat cerebrum, canine bocavirus 2 in dog intestine, and porcine circovirus 2 in pig tissues [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major ISH Probe Labeling Techniques

| Labeling Method | Detection System | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioactive Isotopes (³²P, ³⁵S) | Autoradiography | High | Pioneering method, sensitive | Safety hazards, long exposure times, limited resolution [5] [2] |

| Fluorescent Labeling (Fluorescein, Cy3, Cy5) | Fluorescence microscopy | High | Multicolor detection, technically straightforward, automatable | Photobleaching, requires fluorescence microscope [1] [5] |

| Chromogenic (CISH) | Enzyme + chromogen, bright-field microscopy | Moderate-High | Permanent slides, conventional microscopy, cost-effective | Limited multiplexing capability [3] |

| Biotin | Streptavidin/Avidin-enzyme conjugate | High | High sensitivity, signal amplification | Endogenous biotin interference [5] |

| Digoxigenin (DIG) | Anti-DIG antibody-enzyme conjugate | High | Low background, high specificity | Requires specific antibodies [5] [2] |

Experimental Comparisons and Performance Data

Direct Methodological Comparisons in Viral Detection

A comprehensive 2018 study directly compared different ISH techniques for detecting various RNA and DNA viruses, providing valuable experimental data on their relative performance [2]. The researchers evaluated three approaches: (1) CISH with self-designed DIG-labelled RNA probes, (2) CISH with commercially produced DIG-labelled DNA probes, and (3) a commercial FISH method using fluorescent RNA probe mixes (ViewRNA ISH Tissue Assay Kit).

The results demonstrated striking differences in detection capabilities. For RNA virus detection, the FISH-RNA probe mix achieved successful detection of all tested viruses (atypical porcine pestivirus, equine hepacivirus, bovine hepacivirus, and Schmallenberg virus), while self-designed DIG-labelled RNA probes only detected Schmallenberg virus [2]. Similarly, for DNA viruses, the FISH-RNA probe mix identified all targets (canine bocavirus 2, porcine bocavirus, and porcine circovirus 2), whereas the other methods showed variable detection rates [2].

The study further quantified the cell-associated positive area, finding that the detection rate using the FISH-RNA probe mix was highest compared to other probes and protocols [2]. This enhanced sensitivity comes with trade-offs in cost and procedure time, highlighting the importance of matching technique to experimental requirements.

Probe Stability and Shelf-Life Assessment

A critical practical consideration for ISH laboratories is probe stability and shelf-life. Current diagnostic guidelines typically mandate expiration dates of 2-3 years for FISH probes [1]. However, a comprehensive 2025 study challenged this convention by evaluating 581 FISH probes that had been stored for 1-30 years.

Remarkably, all probes, including both self-labeled homemade and commercial varieties, remained functionally active and produced "bright, analyzable signals" regardless of age [1]. The study documented successful FISH experiments using probes labeled with various haptens including biotin, digoxigenin, SpectrumGreen, and SpectrumOrange, with some remaining effective after 30 years of storage at -20°C in the dark [1].

Some fluorochrome-specific variations were noted: "Commercial probes labeled with SpectrumOrange had shorter exposure times and maintained them over the years," while "DNA probes labeled with SpectrumAqua/diethylaminocoumarin showed bright labeling for the first 3 years and then faded" [1]. These findings have significant practical implications, suggesting that properly stored FISH probes may remain usable far beyond their official expiration dates, potentially reducing costs for diagnostic laboratories.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ISH Techniques in Viral Detection Studies [2]

| Virus | Genome Type | CISH with Self-Designed DIG RNA Probes | CISH with Commercial DIG DNA Probes | FISH with RNA Probe Mix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Porcine Pestivirus (APPV) | RNA | Not detected | Not tested | Detected |

| Equine Hepacivirus (EqHV) | RNA | Not detected | Not tested | Detected |

| Bovine Hepacivirus (BovHepV) | RNA | Not detected | Not tested | Detected |

| Schmallenberg Virus (SBV) | RNA | Detected | Not tested | Detected |

| Canine Bocavirus 2 (CBoV-2) | DNA | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| Porcine Bocavirus (PBoV) | DNA | Not detected | Not detected | Detected |

| Porcine Circovirus 2 (PCV-2) | DNA | Detected | Detected | Detected |

Diagnostic Concordance in Clinical Settings

The comparative performance of ISH techniques has significant implications for clinical diagnostics. A 2025 retrospective cohort study of 104 glioma patients systematically compared FISH, next-generation sequencing (NGS), and DNA methylation microarray (DMM) for detecting copy number variations [6]. While all three methods showed high consistency in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) assessment, "FISH demonstrated relatively low concordance with NGS/DMM in detecting other parameters" including cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/B (CDKN2A/B), 1p, 19q, chromosome 7, and chromosome 10 [6].

In contrast, NGS and DMM exhibited strong concordance across all six parameters [6]. These findings highlight both the utility and limitations of FISH in modern integrated diagnostics, particularly noting that discordant cases were associated with high-grade gliomas and high genomic instability [6].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Machine Learning-Enhanced FISH Analysis

The integration of machine learning with FISH represents a cutting-edge advancement in the evolution of ISH technologies. A 2023 study demonstrated the application of ML algorithms to prioritize FISH probes for differentiating primary sites of neuroendocrine tumors [7]. Using FISH assay metrics from 85 small bowel NET and 59 pancreatic NET samples, trained models achieved up to 93.1% classification accuracy on held-out test sets [7].

Notably, the ERBB2 FISH probe emerged as the most important variable for primary site prediction, followed by MET and CDKN2A probes [7]. This approach demonstrates how computational advances can enhance the diagnostic utility of established ISH methods, providing "probabilistic guidance for FISH testing" and enabling more precise tumor classification [7].

Custom Probe Generation Protocols

The limited commercial availability of gene-specific probes for CISH has prompted development of robust protocols for generating laboratory-designed probes. Researchers have established methods using bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) containing human DNA fragments, which are amplified with φ29 polymerase and random primer labeled with biotin [4].

This protocol enables generation of probes mapping to any gene of interest that can be applied to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections (FFPETS), allowing correlation of morphological features with gene copy number changes [4]. The reliability of these custom probes has been validated through multiple strategies including comparison with commercial probes, confirmation of amplifications identified by microarray-based CGH, and demonstration of specific translocations in breast secretory carcinoma [4].

Diagram 1: ISH Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a standard ISH procedure, from specimen preparation through result interpretation, highlighting the critical decision point in selecting appropriate labeling methods.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ISH techniques requires access to specific reagents and tools. The following table outlines key materials and their functions based on current methodologies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ISH Techniques

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorochrome-conjugated probes (SpectrumGreen, SpectrumOrange, Texas Red) | Direct labeling for FISH; visualizable with fluorescence microscopy | Multicolor FISH, gene rearrangement detection [1] |

| Biotin-labeled probes | Hapten-based labeling; detected with streptavidin-enzyme conjugates | High-sensitivity detection with signal amplification [5] |

| Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes | Hapten-based labeling with low background; detected with anti-DIG antibodies | Viral detection in tissue sections [2] |

| BAC clones | Source of DNA for custom probe generation | Laboratory-designed probes for specific genes [4] |

| φ29 polymerase | Multiple displacement amplification for probe production | Generating high-quality probes from BAC DNA [4] |

| Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections | Standard specimen preservation for morphological correlation | Archival tissue analysis, clinical diagnostics [3] [4] |

| Proteolytic digestion enzymes (Proteinase K, pepsin) | Tissue pretreatment for probe accessibility | Enhancing hybridization efficiency in FFPE tissues [3] [2] |

| ViewRNA ISH Tissue Assay Kit | Commercial system for FISH with signal amplification | Sensitive detection of low-abundance viral RNAs [2] |

Diagram 2: ISH Technique Selection Guide. This decision pathway illustrates key considerations when selecting appropriate ISH methodologies based on sensitivity requirements, equipment availability, and application purpose.

The evolution of ISH from its radioactive origins to modern fluorescent and chromogenic tags represents a compelling narrative of scientific innovation driven by the dual needs of technical performance and practical utility. While radioactive methods established the fundamental principle of in situ hybridization, the development of non-radioactive alternatives has dramatically expanded the applications and accessibility of this powerful technology.

Current ISH methods offer researchers a diverse toolkit, with FISH providing exceptional sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities, while CISH enables genetic analysis using conventional microscopy platforms essential for many diagnostic settings. The demonstrated long-term stability of properly stored FISH probes further enhances their practical value in both research and clinical contexts [1].

As ISH technologies continue to evolve, integration with computational approaches like machine learning [7] and ongoing refinement of probe design methodologies [4] promise to further enhance their diagnostic precision and research applications. This continuous innovation ensures that ISH remains an indispensable methodology for spatial genomics and transcriptomics, bridging the critical gap between molecular analysis and morphological context.

Nucleic acid probes are single-stranded DNA or RNA fragments engineered with a strong affinity for a specific complementary DNA or RNA target sequence [8]. These essential tools in molecular biology and diagnostics allow for the precise detection and localization of genetic material, enabling applications ranging from basic research to clinical diagnostics and drug development [9] [8]. The core principle involves the hybridization of the probe to its target sequence, facilitated by the degree of homology between them, which allows for the visualization and analysis of specific nucleic acid regions within complex biological samples [8].

Within the context of in situ hybridization (ISH) techniques, which allow for precise localization of specific nucleic acid segments within histologic sections, the choice of probe type is critical [9]. The three primary categories—DNA probes, RNA probes (riboprobes), and synthetic oligonucleotides—each possess distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations that determine their suitability for specific experimental and clinical needs [10]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these core probe types, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform strategic probe selection in research and development.

Core Characteristics and Comparison

The fundamental differences in the chemical structure of DNA and RNA probes lead to variations in their stability, hybridization efficiency, and optimal applications. DNA probes are composed of deoxyribonucleic acid, featuring a backbone that makes them relatively chemically stable and less prone to degradation [10]. In contrast, RNA probes (riboprobes) are made of ribonucleic acid; the presence of a 2' hydroxyl group in their structure makes them more chemically unstable and susceptible to alkaline hydrolysis compared to DNA [10]. A key functional difference lies in the stability of the hybrid formed with the target: RNA-RNA hybrids formed by riboprobes are more stable than DNA-DNA hybrids, contributing to the higher sensitivity often observed with RNA probes [11].

Synthetic oligonucleotides represent a broader category that includes not only standard DNA oligonucleotides but also various analogs with modified backbones, such as Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA) and Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) [12]. These analogs are engineered to overcome some limitations of natural nucleic acids. PNA, for instance, has an uncharged peptide-like backbone, which allows for stronger binding to complementary sequences and greater resistance to nucleases and proteases [12].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of DNA, RNA, and Synthetic Oligonucleotide Probes

| Characteristic | DNA Probes | RNA Probes (Riboprobes) | Synthetic Oligonucleotides |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | Deoxyribose sugar-phosphate backbone; Thymine | Ribose sugar-phosphate backbone; Uracil; 2' OH group [10] | Includes analogs with modified backbones (e.g., PNA, LNA) [12] |

| Primary Synthesis Method | Chemical synthesis, PCR, Nick translation [8] | In vitro transcription (IVT) from DNA templates [10] [8] | Automated chemical synthesis [10] |

| Typical Length | 20 - 1000 bp (some FISH probes 1-10 Kb) [10] | 200 - 500 bases (optimal for ISH) [11] | 20 - 50 bases (common for synthetic) [11] |

| Thermal Stability & Hybrid Strength | DNA-DNA hybrids are less stable than RNA-DNA/RNA-RNA hybrids [11] | RNA-RNA/DNA hybrids are more stable, leading to higher sensitivity [11] | PNA and LNA exhibit enhanced binding affinity and thermal stability [12] |

| Native Chemical Stability | High; resistant to alkaline hydrolysis [10] | Lower; susceptible to RNase degradation and hydrolysis [10] | Generally high; PNA is resistant to nucleases and proteases [12] |

| Key Applications in ISH | Locus-specific FISH, whole chromosome painting, CISH [10] | RNA ISH, high-sensitivity gene expression localization [10] [11] | miRNA detection (LNA probes), rapid diagnostic assays [10] [12] |

Performance Data from Comparative Studies

A systematic comparative evaluation of DNA and RNA probes for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides robust, quantitative data on their performance differences [13]. Under optimized hybridization conditions, the study directly compared probes based on metrics critical for NGS, such as enrichment efficiency and robustness against artifacts.

The findings revealed a clear trade-off: RNA probes demonstrated superior enrichment efficiency, characterized by significantly higher mtDNA mapping rates and greater average mtDNA depth per gigabyte of sequencing data in both fresh tissue and plasma samples [13]. However, DNA probes were more effective at reducing artifacts caused by nuclear mitochondrial DNA segments (NUMTs) at both the read and mutation levels, a crucial factor for accurate mutation detection [13]. Furthermore, RNA probes captured a broader fragment size distribution in plasma cell-free mtDNA, indicating a potential bias towards longer fragments [13].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of DNA vs. RNA Probes in mtDNA NGS [13]

| Performance Metric | DNA Probes | RNA Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Average mtDNA Mapping Rate (Fresh Tissue) | 61.79% | 92.55% |

| Average mtDNA Depth per GB (Fresh Tissue) | ~32,400X | ~38,500X |

| Average mtDNA Mapping Rate (Plasma) | 16.18% | 42.95% |

| Average mtDNA Depth per GB (Plasma) | ~9,180X | ~15,270X |

| Interference from NUMTs | Lower (more effective at reducing artifacts) | Higher |

| Fragment Size Distribution | Narrower, more uniform | Broader, prevalence of longer fragments |

The efficacy of synthetic oligonucleotide analogs was highlighted in a study probing bacterial ribosome assembly [12]. The research found that while DNA antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) showed only a subtle inhibitory effect on ribosome assembly, their synthetic analogs—particularly PNA and LNA—demonstrated significantly improved inhibitory effects, consistent with their well-characterized superior in vitro hybridization free energies (LNA > PNA > DNA) [12]. This underscores the value of synthetic probes in applications requiring very high binding affinity and disruptive potential.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Probe Synthesis and Labeling Methodologies

The processes for generating different probe types are distinct and have implications for cost, complexity, and probe quality.

DNA Probe Synthesis (Nick Translation): This is a classic method for generating labeled double-stranded DNA probes [8]. The protocol involves randomly "nicking" the backbone of a double-stranded DNA template with dilute DNase I. The enzyme DNA polymerase I then simultaneously removes nucleotides from the probe molecules in the 5'→3' direction (exonuclease activity) and replaces them with labeled dNTP precursors (polymerase activity) [8]. This method is efficient and can be completed in less than an hour, accommodating fluorophore-, biotin-, or digoxigenin-labeled nucleotides [8].

RNA Probe (Riboprobe) Synthesis (In Vitro Transcription): This is the primary and most reliable method for producing RNA probes [11] [8]. The process starts with a purified DNA template (either linearized plasmid or PCR product) containing a bacteriophage RNA polymerase promoter (e.g., T7, SP6, T3) upstream of the sequence of interest [11]. The template is incubated with the appropriate RNA polymerase and a mixture of nucleotides, including labeled ones (e.g., biotin- or digoxigenin-UTP), to generate large amounts of uniformly labeled, single-stranded RNA probes [11] [8]. A common strategy for ISH is to clone the DNA sequence between two opposing promoters to independently generate antisense (detection) and sense (control) probes from the same template [11] [8].

Diagram 1: Riboprobe Synthesis Workflow via In Vitro Transcription

DNA vs. RNA Probe Hybridization Workflow for NGS

A detailed 2025 study on mtDNA NGS provides a clear experimental workflow for comparing probe performance [13]. The protocol begins with the extraction of genomic DNA from samples (e.g., fresh frozen tissue or plasma), followed by the construction of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) libraries. For tissue samples, DNA is typically sheared to fragments of 300-500 bp [13]. These WGS libraries are then subjected to hybridization-based capture using custom-designed double-stranded DNA and RNA probes that comprehensively cover the mitochondrial genome. After enrichment, the libraries are sequenced via NGS, and the resulting data is analyzed bioinformatically to compare performance metrics such as mapping rate, depth of coverage, and NUMT interference [13].

Diagram 2: Probe Comparison Workflow for Targeted NGS

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful probing experiments, particularly in ISH, rely on a suite of essential reagents and tools. The following table details key components for probe-based research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Probe-Based Applications

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage RNA Polymerases (T7, SP6, T3) | Enzymes for synthesizing RNA probes (in vitro transcription) from specific promoters on DNA templates [11]. | Essential for riboprobe generation; choice depends on promoter in cloning vector. |

| DNA Polymerase I / Klenow Fragment | Used for DNA probe synthesis via nick translation (full enzyme) or random priming (Klenow fragment) [8]. | Incorporates labeled nucleotides into DNA probe sequences. |

| Modified Nucleotides (dNTPs/UTPs) | Nucleotides conjugated to labels (e.g., biotin, digoxigenin, fluorophores) for probe detection [8]. | Key for non-radioactive detection; different labels offer varying sensitivity. |

| DNase I | Enzyme used in nick translation to create initial nicks in double-stranded DNA template backbone [8]. | Critical for initiating the nick translation DNA labeling process. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protects sensitive RNA probes from degradation by ubiquitous RNases during synthesis and handling [10]. | Crucial for maintaining integrity of riboprobes. |

| Cloning Vectors with Promoters | Plasmid templates containing phage promoters (e.g., pGEM-T) for inserting target sequence and producing riboprobes [11]. | Provides a renewable source for consistent riboprobe production. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Enzymes for linearizing plasmid DNA templates prior to in vitro transcription [11]. | Ensures production of defined-length RNA transcripts. |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) / Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA) | Synthetic nucleotide analogs with modified backbones that confer enhanced binding affinity and stability [12]. | Used in synthetic oligonucleotide probes for challenging targets like miRNAs or for disruptive probing. |

The comparative data and protocols presented in this guide underscore that there is no single "best" probe type; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific experimental requirements and trade-offs.

- Choose RNA Probes (Riboprobes) when the highest sensitivity and hybridization strength are the primary goals, such as in detecting low-abundance mRNA transcripts in RNA ISH or for achieving maximum enrichment efficiency in targeted NGS, even at the cost of potential artifacts from homologous sequences like NUMTs [13] [11].

- Choose DNA Probes for applications where robustness, chemical stability, and lower cost are prioritized, or when minimizing artifacts (e.g., NUMT interference in mtDNA studies) is critical for accurate mutation detection [13] [10].

- Choose Synthetic Oligonucleotides (including standard oligos, LNAs, and PNAs) for flexibility, high affinity, and nuclease resistance. They are ideal for standardized diagnostic assays, detecting short targets like miRNAs, and for applications requiring exceptional binding strength to disrupt native structures, as demonstrated in ribosome assembly studies [10] [12].

This structured comparison of DNA, RNA, and synthetic oligonucleotide probes, grounded in recent experimental findings, provides a framework for researchers to make informed decisions, thereby enhancing the precision and reliability of their scientific and diagnostic outcomes.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a fundamental molecular technique for localizing and detecting specific nucleic acid sequences in cells, tissue sections, and entire tissues [14]. The technique relies on hybridizing a target nucleotide sequence with a complementary probe that is labeled to enable visualization [14]. The choice of labeling methodology profoundly impacts assay sensitivity, specificity, resolution, and applicability across different research and diagnostic scenarios. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of three principal probe labeling chemistries—nick translation, in vitro transcription, and chemical synthesis—to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal approach for their specific experimental needs within the broader context of evaluating ISH probe labeling techniques.

Methodological Principles and Comparative Analysis

Nick Translation

Principle: Nick translation enzymatically labels double-stranded DNA probes by simultaneously utilizing two enzymes: DNase I to introduce single-strand "nicks" in the DNA backbone, and DNA Polymerase I to remove nucleotides from the 5' end of the nick while incorporating new labeled nucleotides at the 3' end [15] [16]. This process effectively replaces unlabeled nucleotides with labeled ones along the DNA template.

Protocol Outline:

- Reaction Setup: Combine purified DNA template (>1 kb), nick translation buffer, dNTP mix (including labeled dUTP, e.g., biotin-, digoxigenin-, or fluorophore-conjugated), and the Nick Translation Enzyme Mix (DNase I and DNA Polymerase I) [15] [16].

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 15-16°C for approximately 1 hour [15].

- Termination & Purification: Stop the reaction with EDTA and purify the labeled probe to remove unincorporated nucleotides.

This method is recommended for labeling double-stranded DNA larger than 1kb for fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) applications [15].

In Vitro Transcription

Principle: In vitro transcription (IVT) generates labeled RNA probes (riboprobes) from a linearized DNA template cloned downstream of a bacteriophage RNA polymerase promoter (e.g., T3, T7, SP6) [17]. The RNA polymerase synthesizes a single-stranded RNA transcript while incorporating labeled nucleotides.

Protocol Outline:

- Template Linearization: Digest a plasmid containing the insert of interest and the appropriate promoter with a restriction enzyme that cuts downstream of the insert [17].

- Transcription Reaction: Combine the linearized DNA template, transcription buffer, RNase inhibitor, DTT, NTP mix (including DIG- or FITC-labeled UTP), and the specific RNA polymerase [18] [17].

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours [17].

- Template Removal & Purification: Digest the DNA template with DNase I. Precipitate the synthesized RNA probe with LiCl and ethanol [17].

- Optional Hydrolysis: Hydrolyze long RNA transcripts into smaller fragments (200-300 bases) using carbonate buffer to improve tissue penetration [17].

DIG-labeled RNA probes are noted for their stability, with a shelf life of over six years [18].

Chemical Synthesis

Principle: This method involves the automated solid-phase synthesis of short oligonucleotide probes (20-50 bases) with labels directly incorporated via modified phosphoramidites during synthesis or conjugated to the probe post-synthesis. While less detailed in the provided search results, it is the primary method for generating oligonucleotide FISH probes [14].

Common Labels: Synthetic oligonucleotides are commonly labeled with fluorochromes such as Alexa Fluor dyes, CY3, CY5, and Fluorescein [14]. These probes are often used in techniques like single-molecule FISH (smFISH) and multiplexed error-robust FISH (MERFISH) [14].

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of the three labeling methods based on experimental data and established protocols.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of ISH Probe Labeling Methods

| Feature | Nick Translation | In Vitro Transcription | Chemical Synthesis (Oligonucleotides) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Type | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [15] | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA, riboprobes) [17] | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA oligonucleotides) [14] |

| Typical Probe Length | >1 kilobase (kb) [15] | 200-300 bases (after hydrolysis) [17] | 20-50 bases [14] |

| Primary Use Case | DNA target detection (e.g., gene loci, chromosomes) [15] [16] | RNA target detection (mRNA localization) [17] | RNA and DNA target detection, high-throughput multiplexing [14] |

| Key Advantage | Simple protocol, strong signals, ideal for long DNA probes [16] | High sensitivity and specificity for RNA; probe stability [18] | High specificity for short targets; designed for multiplexing [14] |

| Label Incorporation | Enzymatic incorporation of labeled dUTP [15] | Enzymatic incorporation of labeled UTP [17] | Direct during synthesis or post-synthesis conjugation [14] |

| Typical Assay Duration | ~1 hour labeling time [15] | ~4-6 hours (excluding cloning) [17] | N/A (commercially synthesized) |

| Probe Stability | Stable for decades when stored at -20°C in the dark [1] | DIG-labeled: 6+ years; FITC-labeled: ~2 years [18] | Varies by label; generally high |

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Diagnostic Contexts

| Parameter | Nick Translation (FISH) | In Vitro Transcription | Alternative Methods (DMM/NGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concordance with NGS/DMM | Relatively low for CDKN2A/B, 1p, 19q, Chr7, Chr10; high for EGFR [6] | Not directly comparable (different targets) | Strong concordance between NGS and DMM [6] |

| Associated with Discordance | Discordant cases linked to high-grade gliomas and high genomic instability [6] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Best Application | Targeted DNA CNV detection in integrated diagnostics [6] | High-sensitivity RNA detection | Genome-wide CNV assessment [6] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core procedural workflows for each labeling method.

Nick Translation Workflow

In Vitro Transcription Workflow

Chemical Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of ISH probe labeling techniques requires specific reagent solutions. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ISH Probe Labeling

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nick Translation Kit [15] [16] | Provides optimized enzymes and buffer to label DNA via nick translation. | Core reagent for generating FISH/CISH DNA probes. Compatible with fluorophore-, biotin-, and digoxigenin-labeled dUTPs. |

| dUTPs (Biotin-, DIG-, Fluorophore-labeled) [1] [15] | The labeled nucleotide directly incorporated into the probe. | The "label" in the probe. Choice determines detection method (e.g., antibody for DIG/biotin, direct for fluorophore). |

| In Vitro Transcription Kit [17] | Supplies buffers, RNA polymerase, and RNase inhibitor for synthesizing RNA probes. | Core reagent for generating single-stranded riboprobes for high-sensitivity RNA detection. |

| Labeled NTP Mix (e.g., DIG-UTP) [17] | The labeled ribonucleotide incorporated during transcription. | The "label" for RNA probes. DIG-UTP is common and offers high sensitivity via antibody detection. |

| RNA Polymerase (T3, T7, SP6) [17] | Enzyme that transcribes RNA from a DNA template with its specific promoter. | Drives the synthesis of the RNA probe. Must match the promoter sequence in the DNA template. |

| Anti-Digoxigenin Antibody [5] [14] | Antibody conjugated to a reporter enzyme (HRP/AP) or fluorophore to detect DIG-labeled probes. | Key detection reagent for indirect methods using DIG-labeled probes. |

| Streptavidin-HRP/Streptavidin-Fluorophore [5] [19] | Binds to biotin-labeled probes for detection, often with signal amplification. | Key detection reagent for indirect methods using biotin-labeled probes. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Reagents [19] | Provides enzymatic signal amplification for low-abundance targets, boosting sensitivity 10-200x. | Used with HRP-conjugated antibodies/streptavidin for detecting very rare targets. |

The selection of a probe labeling method is a critical determinant of success in ISH experiments. Nick translation remains the robust, standard choice for generating long DNA probes to assess genomic DNA and copy number variations. In vitro transcription is the gold standard for sensitive and specific RNA detection, offering exceptional probe stability. Chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides provides unparalleled flexibility for multiplexed assays and the detection of short targets, powering advanced techniques like smFISH and MERFISH.

Emerging trends point toward increased automation, integration with microfluidics to reduce assay times and reagent volumes [14], and sophisticated computational analysis, particularly deep learning, to automate the interpretation of complex ISH images [20]. As the field progresses, the integration of these robust labeling chemistries with novel delivery platforms and analytical algorithms will further solidify ISH's role as an indispensable tool in both basic research and clinical diagnostics.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology and diagnostic pathology for detecting and localizing specific nucleic acid sequences within cells or tissues, all while preserving tissue integrity [21]. The technique operates on the principle of complementary binding, where a labeled nucleic acid probe anneals to a specific target sequence of DNA or RNA [22]. The choice of probe label is a critical decision that profoundly influences the sensitivity, specificity, safety, and workflow of an experiment. Historically, radioactively labeled probes were the standard; however, the development of non-radioactive labels like biotin, digoxigenin, and fluorophores has dramatically expanded the toolkit available to researchers [23] [21]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these labeling techniques, framed within the context of modern research and drug development.

Technical Comparison of Labeling Technologies

Fundamental Differences and Key Characteristics

Probe labels are fundamentally categorized as either radioactive or non-radioactive. Radioactive probes are tagged with radioactive isotopes (e.g., ³⁵S) and detected by autoradiography [24] [23]. Non-radioactive probes use chemical or fluorescent tags, which are detected through enzymatic reactions (chromogenic detection) or directly via fluorescence microscopy [25] [23]. The core differences in their properties and handling requirements are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Radioactive vs. Non-Radioactive Probes

| Characteristic | Radioactive Probes | Non-Radioactive Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Label Type | Radioactive isotopes (e.g., ³⁵S, ³²P) [24] | Biotin, Digoxigenin, Fluorophores (e.g., SpectrumOrange) [1] [25] |

| Detection Method | Autoradiography, scintillation counting [23] | Chromogenic (CISH) or Fluorescent (FISH) microscopy [25] |

| Sensitivity | Historically high sensitivity [24] | High sensitivity, enhanced by signal amplification [22] |

| Resolution | Lower, due to scatter from radiation [24] | High, allowing for precise subcellular localization [22] |

| Hazard Profile | High; requires special safety protocols and waste disposal [23] | Low; generally safer and easier to handle [23] |

| Shelf Life | Short, limited by isotope half-life | Long; stable for decades when stored properly at -20°C [1] |

| Experiment Duration | Long (exposure for autoradiography) [24] | Relatively shorter [22] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low or none | High, especially with fluorescent probes [26] |

Quantitative Performance Data from Experimental Studies

Direct comparisons in research studies highlight practical performance differences. A seminal 1993 study directly compared radioactive and non-radioactive ISH for localizing calretinin mRNA in inner ear tissues and found radioactive ISH to be more sensitive, successfully revealing positive signals in inner hair cells that were not detected with the non-radioactive method under their experimental conditions [24]. The table below summarizes key experimental findings.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Key Studies

| Study / Context | Probe Label & Type | Key Experimental Finding | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localization of calretinin mRNA, Rat & Guinea Pig Inner Ear [24] | Radioactive (³⁵S) vs. Non-radioactive (Digoxigenin) | Radioactive ISH was more sensitive, detecting positive structures in inner hair cells that non-radioactive ISH did not. | Radioactive labels may be necessary for detecting low-abundance mRNA targets. |

| Long-term Probe Stability, Human Cytogenetics [1] | Non-radioactive (Biotin, Digoxigenin, Fluorophores) | 581 FISH probes, both self-labeled and commercial, stored at -20°C for 1-30 years, all functioned perfectly upon reuse. | Non-radioactive probes are a cost-effective, long-term resource; expiration dates can be conservative. |

| Clinical Diagnostics & Market Trends [26] | Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., SpectrumOrange) | The fluorescent probe segment holds 50% of the FISH probe market, driven by oncology and genetic disorder diagnostics. | Fluorescent probes are the established standard for clinical and high-throughput research applications. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Workflow for In Situ Hybridization

The following diagram outlines the generalized ISH workflow, highlighting steps where the choice of label introduces procedural variations.

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Tissue Preparation: Optimal tissue fixation is critical. 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) for 24±12 hours is the standard for FFPE tissues, providing a balance between nucleic acid preservation and morphology [22]. Over-fixation can cause excessive cross-linking, leading to false-negative results, while under-fixation risks RNA degradation and poor morphology [22] [21].

Probe Hybridization: The hybridization temperature, typically between 37°C and 65°C, must be optimized for specificity and is often lower than the probe-target melting temperature (Tm) when formamide is used to conserve sample morphology [25] [21]. Post-hybridization, washes of increasing stringency are performed to remove nonspecifically bound probes [25].

Signal Detection and Visualization:

- Radioactive Probes: Hybridized samples are exposed to X-ray film in a process called autoradiography, which can take from hours to days, depending on signal strength [24].

- Non-Radioactive Probes:

- Biotin is detected using streptavidin or avidin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (AP) or horseradish peroxidase (HRP) [25] [21]. Note that endogenous biotin can cause background and requires blocking [25].

- Digoxigenin is detected with high specificity using anti-digoxigenin antibodies conjugated to AP or HRP, avoiding issues with endogenous molecules [25] [21].

- Fluorophores allow for direct detection without an enzymatic step and are visualized via fluorescence microscopy [25].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions for performing ISH, based on protocols from the search results.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for In Situ Hybridization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) | Standard tissue fixative that preserves nucleic acids and morphology [22]. | Fixation time should be optimized; over-fixation reduces probe accessibility [21]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme used for tissue permeabilization; digests proteins to allow probe penetration [25]. | Concentration is critical. Must be titrated (e.g., 1-5 µg/mL) to balance signal with tissue integrity [25]. |

| Formamide | A component of hybridization buffers that allows for lower hybridization temperatures [25]. | Helps preserve tissue morphology by lowering the melting temperature of the probe-target hybrid [21]. |

| Digoxigenin-dUTP | A non-radioactive label incorporated into probes via nick translation or random priming [25]. | High specificity due to lack of endogenous digoxigenin in mammalian tissues [25]. |

| Biotin-dUTP | A non-radioactive label incorporated into probes [25]. | Requires blocking of endogenous biotin to prevent high background in some tissues [25]. |

| Fluorophore-dUTP (e.g., SpectrumOrange) | A fluorescent label for direct detection in FISH [1]. | Enables multiplexing. Stable for decades at -20°C [1]. |

| Anti-Digoxigenin Antibody (conjugated to AP/HRP) | Detection antibody for digoxigenin-labeled probes in chromogenic ISH (CISH) [25]. | Conjugate choice (AP vs. HRP) depends on the substrate and tissue type. |

| Streptavidin (conjugated to AP/HRP or a fluorophore) | Detection molecule for biotin-labeled probes [25]. | Binds with high affinity to biotin. |

| Positive & Negative Control Probes | Essential for validating assay performance and RNA integrity [27]. | A housekeeping gene probe confirms technique; a bacterial gene (e.g., dapB) checks background [27]. |

The choice between radioactive and non-radioactive probes is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific research question. Radioactive probes still hold value for their high sensitivity in detecting low-abundance targets, as demonstrated in specialized research applications [24]. However, for the vast majority of modern research and clinical diagnostics, non-radioactive probes offer a compelling combination of safety, stability, and flexibility. The powerful capabilities of digoxigenin for sensitive chromogenic detection and fluorophores for multiplexed spatial biology are driving their widespread adoption [22] [26]. As the market for FISH probes continues to grow, fueled by advancements in precision medicine [26], the trend is firmly set towards the continued refinement and application of non-radioactive labeling technologies.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that allows for the precise detection and localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within cells or tissue sections [28]. The core principle of this method relies on the hybridization dynamics—the specific annealing of a labeled nucleic acid probe to a complementary DNA or RNA target sequence under stringent conditions [29]. The efficiency and stability of this probe-target binding are critical for the sensitivity and specificity of numerous diagnostic and research applications, from detecting infectious agents to profiling cancer biomarkers [30] [31]. Understanding the factors that govern these fundamental dynamics is essential for developing robust assays, especially when detecting variable targets such as viral genomes or when designing probes for multiplexed spatial biology applications [30] [32].

This guide objectively compares the performance of different probe labeling and design strategies by synthesizing experimental data from current research. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on evaluating ISH probe labeling techniques, providing researchers and drug development professionals with validated protocols and comparative data to inform their experimental design.

Core Factors Governing Hybridization Efficiency

The binding between a probe and its target is a complex process governed by both the probe's sequence composition and the physicochemical environment of the hybridization reaction. Key factors include the following.

Probe Design and Sequence Composition

- Contiguous Matching Stretches: Experimental work with 70-nucleotide (nt) long DNA probes demonstrates that the distribution of mismatches is more critical than their total number. When mismatches interrupt contiguous matching stretches of 6 nt or longer, hybridization is significantly disrupted. Conversely, the same number of matching nucleotides separated into several smaller regions by mismatches results in weaker binding [30].

- Universal Bases and Wobbles: To counteract sequence variation, incorporation of universal bases like deoxyribose-Inosine (dInosine) can remarkably stabilize hybridization. In 70-mer probes, dInosine substitutions at mismatching positions performed comparably to wobble bases (N, representing a mixture of all four nucleotides), and both were more effective than another universal base analog, 5-nitroindole [30].

- Probe Type and Backbone: The stability of the hybrid formed follows the order: RNA-RNA > RNA-DNA > DNA-DNA [25]. Furthermore, synthetic backbones like Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) offer higher affinity for complementary sequences and greater resistance to nucleases and proteases due to their uncharged chemical structure. This is particularly beneficial for penetrating bacterial cell walls and accessing structured ribosomal RNA targets [31].

Hybridization Conditions and Buffer Chemistry

- Stringency Control: Hybridization specificity is primarily driven by temperature and the concentration of monovalent cations in the hybridization buffer. Post-hybridization washes of increasing stringency are critical for dissociating imperfect matches and reducing background [25].

- TMAC Buffer: The use of 3M tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC) buffer is a key strategy to reduce the sequence composition bias. TMAC selectively raises the stability of A:T base pairs to approximately that of G:C base pairs, allowing for more consistent hybridization performance across probes of different sequences [30].

- Formamide and Temperature: Formamide is commonly included in hybridization buffers as it allows the reaction to proceed at temperatures significantly lower than the actual melting temperature (Tm) of the probe-target hybrid, thereby helping to preserve tissue morphology [25].

Comparative Analysis of Probe Technologies and Performance

The following tables summarize experimental data comparing the performance of various probe design strategies and labeling techniques, highlighting their specific advantages and validated applications.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Probe Design Strategies for Mismatch Tolerance

| Probe Design Strategy | Experimental Findings | Key Applications | Reference Model/System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long DNA Probes (70-mer) | Tolerant to naturally occurring synonymous mutations when mismatches do not break contiguous matching stretches ≥6 nt. | Detection of highly variable viral genomes (e.g., Influenza A, Norovirus). | Microsphere-linked probes in Luminex system [30] |

| dInosine-Substituted Probes | Remarkable mismatch tolerance; stabilized hybridization comparable to N wobbles. Preserved specificity. | Broadly targeted yet specific detection of viral variants. | 3M TMAC buffer hybridization [30] |

| PNA (Peptide Nucleic Acid) Probes | Higher affinity for DNA/RNA; better cell wall penetration; resistant to nucleases. Sensitivity: 80.0-93.8%, Specificity: 90.9-93.8%. | Detection of H. pylori and its clarithromycin resistance in gastric biopsy specimens. | Paraffin-embedded tissue; PNA-FISH validation [31] |

| Multiplex Oligonucleotide Probes (smFISH) | ~20 singly-labeled 20-mer probes per transcript enable precise localization and semi-automated quantification of individual mRNA molecules. | Single-molecule RNA detection and quantification in cultured cells and tissues. | Raj et al. (2006, 2008) method [28] |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Probe Labeling and Detection Systems

| Labeling/Detection System | Key Characteristics | Performance Considerations | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dyes (Direct) | Fluorophore (e.g., SpectrumOrange, Cyanine 5) directly attached to probe. | Enables multiplexing; stable for decades at -20°C [1]; may be subject to photobleaching. | FISH for metaphase/interphase cytogenetics [1] |

| Biotin (Indirect) | Detected by streptavidin- or avidin-conjugated reporters (AP/HRP). | Strong signal amplification; potential for endogenous biotin background. | Chromogenic ISH (CISH) [25] |

| Digoxigenin (Indirect) | Detected by high-affinity anti-digoxigenin antibodies conjugated to reporters. | High sensitivity and specificity; minimal endogenous background. | RNA ISH; high-resolution CISH [25] |

| Dual-Hapten (Biotin/Digoxigenin) | Self-labeled homemade probes using dUTPs tagged with haptens. | Proven functionality after 30 years of storage at -20°C. | Home-brew FISH probes for diagnostics [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Optimization

Protocol: Validation of Mismatch-Tolerant Probe Hybridization

This protocol is adapted from studies on long DNA probes and dInosine substitution, designed to quantify hybridization tolerance to mismatches [30].

Step 1: Probe Design and Synthesis

- Select a conserved 70-nt target region from a gene of interest (e.g., Influenza A matrix protein gene).

- Design a set of probes with varying numbers and distributions of mismatches. Include probes with substitutions of dInosine or wobble bases (N) at mismatch-prone positions.

- Synthesize 5' amine-modified 70-mer oligonucleotide probes for coupling to microspheres.

Step 2: Probe Coupling and Target Preparation

- Couple amine-modified probes to color-coded carboxylated microspheres using a carbodiimide coupling method (e.g., EDC chemistry) [30].

- Prepare biotinylated single-stranded DNA targets that are complementary to the probe consensus sequence but contain defined mismatches.

Step 3: Hybridization in TMAC Buffer

- Hybridize microsphere-linked probes (0.2 nM target concentration) in 3M TMAC buffer at a standardized temperature (e.g., 45-55°C).

- The TMAC buffer minimizes the impact of variable GC-content on hybridization stability.

Step 4: Detection and Analysis

- Incubate with streptavidin-phycoerythrin and analyze hybridization signals using a flow cytometry-based system (e.g., Luminex 200).

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Measure the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each probe-target pair. Normalize signals to a perfectly matched control. Probes with dInosine or wobbles at mismatch sites should show significantly higher normalized MFI compared to unmodified probes with the same mismatch pattern.

Protocol: PNA-FISH for Antimicrobial Resistance Detection

This protocol outlines the method for detecting H. pylori and its clarithromycin resistance directly from paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens, as validated in clinical studies [31].

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Sectioning

- Obtain formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) gastric biopsy specimens.

- Cut 3-μm-thick sections and mount on slides.

Step 2: Deparaffinization and Permeabilization

- Deparaffinize slides in xylol and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series.

- Digest samples with Proteinase K (e.g., 1-5 μg/mL for 10 minutes at room temperature). Optimization Note: A titration experiment is crucial. Insufficient digestion diminishes signal, while over-digestion destroys tissue morphology [25].

Step 3: PNA Probe Hybridization

- Hybridize with PNA probes (typically 13-18 bp) targeting the wild-type or mutant (A2142G, A2143G) sequences of the H. pylori 23S rRNA gene.

- Use a standardized hybridization buffer and incubate at a defined temperature for a specific duration.

Step 4: Stringency Washes and Detection

- Perform post-hybridization stringency washes to remove non-specifically bound probes.

- Detect fluorescently labeled PNA probes and counterstain with DAPI.

Step 5: Microscopy and Interpretation

- Visualize under a fluorescence microscope. The presence of H. pylori is confirmed by specific fluorescent signals. The resistance genotype is determined by which probe set (wild-type vs. mutant) produces the signal.

- Validation Metrics: Compared to culture and Etest, this PNA-FISH method demonstrated a sensitivity of 80.0-84.2% and a specificity of 90.9-93.8% in clinical validations [31].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the nucleation-zipping model and the critical experimental steps for a robust FISH assay, integrating the key factors discussed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Hybridization Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| TMAC (Tetramethylammonium Chloride) | Hybridization buffer that neutralizes sequence composition bias, making A:T and G:C base pairs equally stable. | Essential for comparing probes of different sequences or when analyzing targets with variable GC-content [30]. |

| dInosine (Deoxyribose-Inosine) | Universal base that pairs with all four canonical bases (I:C > I:A > I:T ≈ I:G). | Used in probe synthesis to introduce mismatch tolerance at variable positions, preserving specificity in long probes [30]. |

| PNA (Peptide Nucleic Acid) Probes | Synthetic DNA mimics with a neutral backbone, conferring higher affinity and nuclease resistance. | Ideal for challenging FISH applications, such as penetrating Gram-negative bacterial cell walls (e.g., H. pylori) [31]. |

| Proteinase K | Protease enzyme that digests proteins, permeabilizing the sample to allow probe access to nucleic acids. | Concentration and time must be titrated for each tissue type; over-digestion destroys morphology [25]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) | Modified RNA nucleotides with a bridged sugar, increasing duplex stability and thermal affinity (Tm). | Incorporated into oligonucleotide probes (e.g., primers) to increase hybridization strength and specificity [30]. |

| Hapten-Labeled dNTPs (Biotin-, Digoxigenin-dUTP) | Modified nucleotides incorporated into probes via Nick Translation or Random Priming for indirect detection. | Probes labeled with these haptens and stored at -20°C in the dark have been shown to remain functional for over 30 years [1]. |

The fundamental dynamics of probe-target binding and stability are governed by an interplay of probe design, chemical composition, and hybridization environment. Data confirms that strategies employing long probes with preserved contiguous matching stretches or stabilizing modifications like dInosine offer remarkable tolerance to sequence variation without sacrificing specificity. Furthermore, the choice of probe chemistry—such as PNA for challenging cellular targets or hapten-labeled DNA for long-term stability—directly impacts assay performance.

These findings provide a solid foundation for the evaluation of ISH probe labeling techniques. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative guide underscores that there is no single optimal solution; rather, the choice of probe and hybridization strategy must be tailored to the specific biological question, target accessibility, and required performance metrics. As the field moves towards higher multiplexing and spatial resolution, these fundamental principles of hybridization dynamics will continue to underpin the development of next-generation diagnostic and research tools.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Labeling Techniques in Research and Diagnostics

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) represents a pivotal molecular cytogenetics technique for localizing specific nucleic acid sequences within fixed tissues and cells. This method provides crucial temporal and spatial information about gene expression and genetic loci, offering researchers and clinicians a powerful tool for diagnostic and research applications [33]. Within the broader context of in situ hybridization (ISH) probe labeling techniques, direct detection methods utilizing fluorescent dyes have emerged as a preferred approach for many applications due to their capacity for multiplexing, rapid visualization, and high sensitivity compared to non-fluorescent alternatives [34]. As technological advancements continue to refine FISH methodologies, understanding the workflow considerations and performance characteristics of direct fluorescent detection becomes essential for optimizing experimental design in research and diagnostic settings.

This guide objectively compares the performance of direct fluorescence detection FISH with other ISH labeling techniques, providing supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate molecular cytogenetics approaches.

Technical Foundations of FISH and Alternative Labeling Methods

In situ hybridization encompasses various techniques for localizing nucleic acid sequences within biological samples. The fundamental difference between FISH and other ISH methods lies in the detection system employed. FISH utilizes fluorescently labeled probes that can be directly visualized through fluorescence microscopy, whereas other ISH approaches typically employ non-fluorescent hapten-labeled probes detected through enzymatic reactions or immunohistochemistry [34].

The evolution of ISH began with radioactive isotope labeling using 32P or 35S isotopes, which provided high sensitivity but posed significant safety concerns and is rarely used in modern laboratories [5]. Non-radioactive methods have largely replaced these techniques, with fluorescent labeling emerging as a leading approach due to its sensitivity, versatility, multicolor detection capability, and technical straightforwardness [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Major ISH Probe Labeling Methods

| Labeling Method | Detection Principle | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Labeling | Direct fluorescence microscopy | High sensitivity, multiplexing capability, technically straightforward | Photobleaching, requires fluorescence microscope | Gene presence, copy number, location; mutation analysis [5] [33] |

| Biotin Labeling | Streptavidin/Avidin binding with enzymatic or fluorescent detection | High sensitivity and specificity | Potential interference from endogenous biotin | General purpose ISH, often with signal amplification [5] |

| Digoxigenin (DIG) Labeling | Anti-DIG antibodies with enzymatic detection | High sensitivity, low endogenous background | Requires antibody detection step | General purpose ISH, especially where background is concern [5] |

| Chemiluminescent Labeling | Substrate-induced chemiluminescent emission | High sensitivity | Complex procedure, precise timing required | Gene expression studies, oncogene detection [5] |

| Nanoparticle Labeling | Optical properties of quantum dots or gold nanoparticles | Great optical stability, multi-color ability | High cost, technically challenging | Specialized applications requiring extreme photostability [5] |

Workflow Considerations for Direct Fluorescence Detection FISH

Fundamental FISH Principles and Procedural Steps

The basic principle of FISH involves hybridization of nuclear DNA of either interphase cells or metaphase chromosomes affixed to a microscopic slide with a nucleic acid probe. These probes are labeled directly through incorporation of a fluorophore or indirectly with a hapten. The labeled probe and target DNA are denatured and allowed to anneal, enabling complementary DNA sequences to form hybrids. For indirectly labeled probes, an additional enzymatic or immunological detection step is required, while direct detection methods allow immediate visualization after hybridization [35]. The signals are ultimately evaluated by fluorescence microscopy.

The FISH methodology consists of several critical stages, each with specific workflow considerations that impact the efficiency, reliability, and interpretation of results. These stages include cytological preparation, probe labeling, hybridization, post-hybridization washing, and signal detection/visualization [35].

Diagram 1: Fundamental FISH experimental workflow showing key procedural steps from sample preparation through final analysis.

Direct Versus Indirect Detection Pathways

A critical distinction in FISH methodologies lies between direct and indirect detection approaches. Direct detection incorporates fluorophores immediately into the probe, allowing visualization after hybridization without additional steps. Indirect detection uses hapten-labeled probes (biotin, digoxigenin) that require subsequent detection with fluorophore-conjugated affinity reagents (streptavidin, antibodies) [19] [35]. While indirect methods can provide signal amplification beneficial for low-abundance targets, direct detection offers simplified workflows, reduced procedural time, and lower background signal.

Diagram 2: FISH detection pathways comparing direct fluorophore labeling with indirect hapten-based approaches requiring secondary detection steps.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Technical Parameters

Sensitivity and Multiplexing Capabilities

Direct fluorescence detection FISH demonstrates distinct advantages in sensitivity and multiplexing capability compared to other ISH methods. The technique's high sensitivity stems from the direct fluorophore incorporation and the capacity for signal amplification using tyramide-based systems [19]. For low-abundance targets, SuperBoost signal amplification kits can provide sensitivity 10-200 times that of standard methods, generating superior signal definition and clarity for high-resolution imaging [19].

The multiplexing capacity of direct fluorescence FISH represents one of its most significant advantages. Using spectrally distinct fluorophore labels for different hybridization probes enables researchers to resolve several genetic elements or multiple gene expression patterns within a single specimen [33] [19]. Experimental data demonstrates successful simultaneous detection of up to five different genes in whole-mount Drosophila embryos using five distinct RNA probes with different fluorophore combinations [19].

Table 2: Workflow Efficiency Comparison Between FISH and Alternative Methods

| Parameter | Direct FISH | Chromogenic ISH (CISH) | Radioactive ISH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Result | Rapid (hours to 1 day) [36] | Longer due to extra detection steps [34] | Extended (days to weeks for autoradiography) [5] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple targets simultaneously) [33] [19] | Limited (typically single color) [34] | Very limited |

| Sensitivity | High [34] | Moderate [34] | High [5] |

| Resolution | Excellent (single molecule detection possible) [28] | Good | Limited by autoradiography |

| Specimen Archiving | Permanent with digital scanning [36] | Permanent | Temporary (signal fades) |

| Equipment Requirements | Fluorescence microscope | Bright-field microscope | Darkroom, autoradiography equipment |

Probe Stability and Shelf-Life Considerations

Workflow efficiency is significantly impacted by reagent stability, and recent experimental data challenges conventional limitations regarding FISH probe shelf life. A comprehensive study evaluating 581 FISH probes labeled 1-30 years prior found that all probes stored at -20°C in the dark functioned perfectly, regardless of official expiration dates [1]. This research demonstrated that self-labeled homemade and commercial FISH probes maintain stability for at least 30 years when properly stored, suggesting that expensive probes need not be discarded due to age alone [1].

Not all fluorophores demonstrate equal stability over extended periods. Studies indicate that DNA probes labeled with SpectrumAqua/diethylaminocoumarin show bright labeling for approximately three years before signal fading, while commercial probes labeled with SpectrumOrange maintained consistent performance with shorter exposure times over many years [1].

Optimized FISH Workflow Protocols

Digital FISH Analysis Implementation

Recent advancements in FISH workflow digitalization have significantly improved efficiency and standardization. An optimized protocol implementing rapid hybridization and automated whole-slide fluorescence scanning reduced hybridization time from 18 hours to just 4 hours while maintaining excellent signal-to-noise ratios [36]. This approach utilized the IntelliFISH Hybridization buffer and resulted in strong, distinct signals with substantially shortened turnaround times.

Digital slide scanning with appropriate profile selection dramatically impacts workflow efficiency. Research comparing "low profile" (150ms exposure time) and "high profile" (2000ms exposure time) scanning settings found that the low profile setting resulted in significantly shorter scanning times (mean 15min vs 170min) and reduced storage volumes while maintaining sufficient signal quality for most routine applications [36].

Automated Signal Counting and Analysis

Workflow efficiency is further enhanced through automated signal counting approaches. Comparative studies between manual counting and software-based counting (FISHQuant) demonstrated similar results and cut-off values, with automated processing providing graphically represented results within seconds [36]. However, limitations persist with densely packed tissues where nuclear discrimination remains challenging, necessitating manual verification in certain sample types [36].

Applications and Method Selection Criteria

Diagnostic and Research Applications

Direct fluorescence detection FISH has proven particularly valuable in clinical diagnostics, especially for hematologic malignancies where it provides sensitive detection of chromosomal abnormalities that may be missed by conventional cytogenetics [37]. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, FISH enables patient stratification into prognostic categories based on deletion 13q14 (good prognosis), trisomy 12 (intermediate prognosis), and deletions of ATM or TP53 (poor prognosis) [37].

In glioma diagnostics, FISH has been traditionally employed for copy number variation assessment, though emerging technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) and DNA methylation microarray (DMM) now provide alternative approaches. Comparative studies demonstrate that while all three methods show high consistency in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) assessment, FISH exhibits relatively low concordance with NGS/DMM in detecting other parameters like CDKN2A/B, 1p, 19q, chromosome 7, and chromosome 10 [6].

Selection Criteria for Appropriate Method Implementation

Choosing between direct fluorescence FISH and alternative ISH methods requires consideration of multiple experimental parameters:

- Target abundance: For low-abundance targets, highly sensitive labeling methods such as fluorescent labeling combined with signal amplification techniques are recommended [5]

- Sample type: Cell samples are particularly well-suited for fluorescent labeling, while tissue sections require greater consideration of probe penetration and background interference [5]

- Multiplexing requirements: Applications requiring detection of multiple targets simultaneously are ideally served by direct fluorescence FISH [33]

- Equipment availability: Fluorescent labeling necessitates access to fluorescence microscopy, while other methods may require different detection systems [5]

- Turnaround time: Direct FISH provides more rapid results than many alternative ISH methods [34]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of direct fluorescence FISH workflows requires specific reagent systems optimized for particular applications and sample types.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Direct Fluorescence FISH Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorophore Conjugates | Alexa Fluor dyes (488, 555, 594, 647) [19] | Direct probe labeling for multiplex detection with high photostability |

| Signal Amplification Systems | SuperBoost Tyramide Signal Amplification Kits [19] | Enzyme-mediated deposition of fluorescent tyramides for low-abundance targets |

| Hybridization Buffers | IntelliFISH Hybridization Buffer [36] | Rapid hybridization reducing process time from 18h to 4h with strong signals |

| Mounting Media | VECTASHIELD HardSet with DAPI [36] | Antifade mounting medium with nuclear counterstain, minimal hardening time |

| Probe Labeling Kits | FISH Tag DNA and RNA Kits [19] | Enzymatic incorporation of amine-modified nucleotides for consistent labeling |

| Nucleic Acid Labels | ChromaTide dUTP conjugates (biotin, Texas Red, Oregon Green) [19] | Modified nucleotides for direct enzymatic incorporation during probe synthesis |

| Automated Analysis Software | FISHQuant [36] | Automated quantification of structural and numerical FISH signal abnormalities |

Direct detection methods using fluorescent dyes represent a powerful approach within the broader spectrum of ISH techniques, offering significant advantages in multiplexing capability, workflow efficiency, and sensitivity when appropriately implemented. While alternative methods including chromogenic ISH and radioactive ISH maintain relevance for specific applications, direct fluorescence FISH provides unparalleled capacity for simultaneous visualization of multiple targets with rapid turnaround times.

The evolving landscape of FISH methodology continues to benefit from workflow optimizations including reduced hybridization times, digital slide analysis, and enhanced probe stability. Understanding the comparative performance characteristics and appropriate application contexts for these various techniques enables researchers and clinical laboratory professionals to select optimal approaches for their specific experimental or diagnostic requirements. As molecular cytogenetics advances, direct fluorescence detection methods remain essential tools for spatial genomic analysis and expression profiling across diverse research and clinical settings.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational molecular technique that localizes and detects specific nucleotide sequences within cells, tissue sections, or entire tissues [14]. The technique, first successfully demonstrated in 1969, relies on hybridizing a complementary DNA or RNA probe to a target sequence [1] [14] [38]. Hapten-based detection systems represent a sophisticated approach where probes are labeled with non-radioactive small molecules (haptens) that are subsequently recognized by high-affinity reporter molecules, enabling both direct visualization and significant signal amplification. Within molecular cytogenetics and diagnostic pathology, the two most prominent haptens are biotin and digoxigenin (DIG), which serve as critical tools for indirect detection in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) [1] [38]. These systems are prized for their ability to balance high sensitivity, specificity, and flexibility, making them indispensable for research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

Performance Comparison: Biotin vs. Digoxigenin

The choice between biotin and digoxigenin hinges on experimental requirements for sensitivity, background signal, and sample type. The following table summarizes their core characteristics and performance metrics.

Table 1: Direct comparison of biotin and digoxigenin hapten-based systems.

| Feature | Biotin System | Digoxigenin (DIG) System |

|---|---|---|

| Hapten Origin | Vitamin; endogenous in many organisms [39] | Plant-derived steroid from Digitalis plants; exogenous to animals [39] |

| Detection Ligand | Streptavidin or Avidin [1] | Anti-Digoxigenin Antibody [1] |

| Binding Affinity | Very high (Ka ~10^15 M⁻¹) [39] | High (Ka ~10^11 M⁻¹) [39] |

| Endogenous Interference | Possible, due to endogenous biotin in some tissues [39] | Very low; no endogenous background in animal tissues [39] |

| Primary Application Scope | Versatile; used in ISH, ELISA, and pull-down assays [40] | Highly robust in ISH and immunoassays [39] |

| Signal Amplification Potential | Very high; multiple layers of streptavidin-biotin conjugation possible | High; relies on enzyme-antibody conjugates for catalytic amplification [38] |