Live Cell Imaging of Embryonic Development: From Dynamic Insights to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of live-cell imaging technologies and their transformative impact on the study of embryonic development.

Live Cell Imaging of Embryonic Development: From Dynamic Insights to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of live-cell imaging technologies and their transformative impact on the study of embryonic development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles that enable the decoding of dynamic biological processes, details cutting-edge methodologies and their applications from basic research to drug discovery, offers practical solutions for common experimental challenges, and presents a rigorous comparative analysis of imaging techniques. By synthesizing recent advances and real-world case studies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design robust live-cell imaging experiments that accelerate the translation of developmental insights into clinical applications.

Decoding Development: How Live Imaging Reveals Dynamic Embryonic Processes

The profound complexity of embryonic development unfolds as a four-dimensional process, where precise cellular behaviors in both space and time give rise to functional tissues and organs. Understanding this dynamic choreography requires tools that can capture and quantify biological processes within the intact, living organism. Modern live-cell imaging technologies have transformed this field, moving beyond static snapshots to deliver quantitative, high-resolution data on cell division, migration, and differentiation throughout embryogenesis. This article details core principles and practical protocols for capturing the dynamic nature of embryonic development, providing a framework for researchers to investigate fundamental biological processes with unprecedented clarity and precision.

Advanced Imaging Modalities for Developmental Studies

Selecting the appropriate imaging technology is paramount for successful live imaging of embryos, which are often large, light-scattering, and highly light-sensitive. The table below compares two advanced microscopy methods well-suited for this application.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Imaging Modalities for Embryonic Development

| Feature | Multiview Light-Sheet Microscopy (SiMView) | Microcomputed Tomography (Micro-CT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Long-term, high-speed imaging of rapid cellular dynamics [1] | Quantitative 3D analysis of fixed tissue morphology and organ growth [2] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (e.g., every 30 seconds for entire Drosophila development) [1] | Not applicable (typically for fixed specimens) |

| Specimen Status | Live, intact embryos [1] | Fixed, chemically labeled embryos [2] |

| Key Advantage | Simultaneous multiview acquisition minimizes shadowing and enables accurate cell tracking in entire embryos [1] | Provides highly detailed, quantitative 3D datasets of soft tissue anatomy [2] |

| Data Output | Terabyte-scale multiview movies for quantitative cell tracking [1] | Volumetric measurements of organ growth (e.g., heart, limb, eye) [2] |

Experimental Protocol: High-Content Live Imaging of Drosophila Embryos

This protocol adapts traditional Drosophila embryo handling for high-content imaging systems, enabling the simultaneous acquisition of multiple embryos for quantitative analysis [3].

Materials & Reagents

- Biological Material: Drosophila melanogaster embryos at the syncytial blastoderm stage.

- Equipment: High-content image analyzer or an inverted microscope capable of automated multi-position acquisition; microinjection system; environmental chamber to maintain temperature at 20°C [3].

- Supplies: Embryo collection cages; apple juice agar plates; heptane glue; imaging chambers [3].

Procedure

- Embryo Collection & Preparation: Maintain and set up population cages with adult flies. Collect embryos on apple juice agar plates. Dechorionate embryos using standard chemical or manual methods.

- Mounting: Adhere dechorionated embryos to an imaging dish using a thin layer of heptane glue. Proper orientation is critical for consistent imaging.

- Microinjection (Optional): For perturbation studies, microinject molecular probes, drugs, or nucleic acids into the embryos. The protocol is compatible with simultaneous injection of multiple embryos [3].

- Image Acquisition: Transfer the dish to the high-content image analyzer. Define multiple acquisition points, each covering a single embryo. Configure imaging parameters (e.g., time-lapse interval, duration, laser power) to monitor the biological process of interest, such as mitotic divisions or morphological changes. Acquire movies simultaneously from 6-12 embryos per session [3].

Fluorescent Reporters for Visualizing Cell Cycle Dynamics

Genetically encoded fluorescent reporters are indispensable tools for monitoring cellular processes like the cell cycle in real-time and at single-cell resolution.

Table 2: Common Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Cell Cycle Reporters

| Reporter System | Mechanism of Action | Reported Cell Cycle Phases | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUCCI | Utilizes cell cycle-dependent degradation of Cdt1 (G1) and Geminin (S/G2/M) fused to fluorescent proteins [4]. | G1 (red), S/G2/M (green), G1/S transition (yellow) [4] | Real-time visualization of phase transitions; suitable for in vivo imaging and FACS sorting [4]. | Cannot distinguish S from G2 phase, or G0 from G1 phase [4]. |

| PCNA-based Reporters | Tracks the localization of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA), which forms foci at DNA replication forks [4]. | S-phase (foci pattern) [4] | Direct reporting of DNA synthesis activity. | Requires high-resolution imaging to discern foci patterns. |

Experimental Protocol: Applying the FUCCI System

Materials & Reagents

- Biological Material: Cells or embryos expressing the FUCCI construct (mKusabiraOrange2-hCdt1 and mAzamiGreen-hGem) [4].

- Equipment: Standard epifluorescence or confocal microscope with time-lapse capability, environmental control (CO₂, temperature, humidity); hardware for 488 nm and 561 nm laser lines.

- Software: Image analysis software capable of quantifying fluorescence intensity over time.

Procedure

- Cell Preparation: Culture FUCCI-expressing cells or prepare transgenic embryos. For live imaging, ensure specimens are maintained in optimal physiological conditions on the microscope stage.

- Image Acquisition: Capture dual-channel fluorescence images (e.g., green and red channels) at regular intervals. The timing will depend on the cell cycle length of the system under study.

- Data Analysis:

- Visual Assessment: Identify cell cycle phases based on color: Red fluorescence indicates G1 phase, green indicates S/G2/M phases, and yellow/orange at the transition indicates G1/S [4].

- Quantitative Analysis: Use image analysis software to measure the mean fluorescence intensity of each channel in individual cells over time. Plotting these intensities reveals the kinetics of cell cycle progression.

Quantitative Analysis of Embryonic Morphogenesis

Imaging generates rich, quantitative data on growth and morphology. The volumetric analysis of embryonic chick organs via Micro-CT established mathematical relationships for growth, revealing distinct patterns [2].

Table 3: Quantitative Volumetric Growth Patterns in Embryonic Chick Organs

| Organ/Tissue | Growth Pattern (HH23 to HH40) | Quantitative Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Eye & Heart | Constant exponential growth [2] | Growth follows a single, unchanging exponential rate throughout the developmental window studied. |

| Forebrain & Limb | Multiple phases of growth [2] | Growth kinetics shift, involving different exponential rates at different developmental stages. |

| Cardiac Myocardium | Time and chamber-specific growth [2] | Volumetric growth rates are not uniform across the heart, varying by developmental time and specific chamber. |

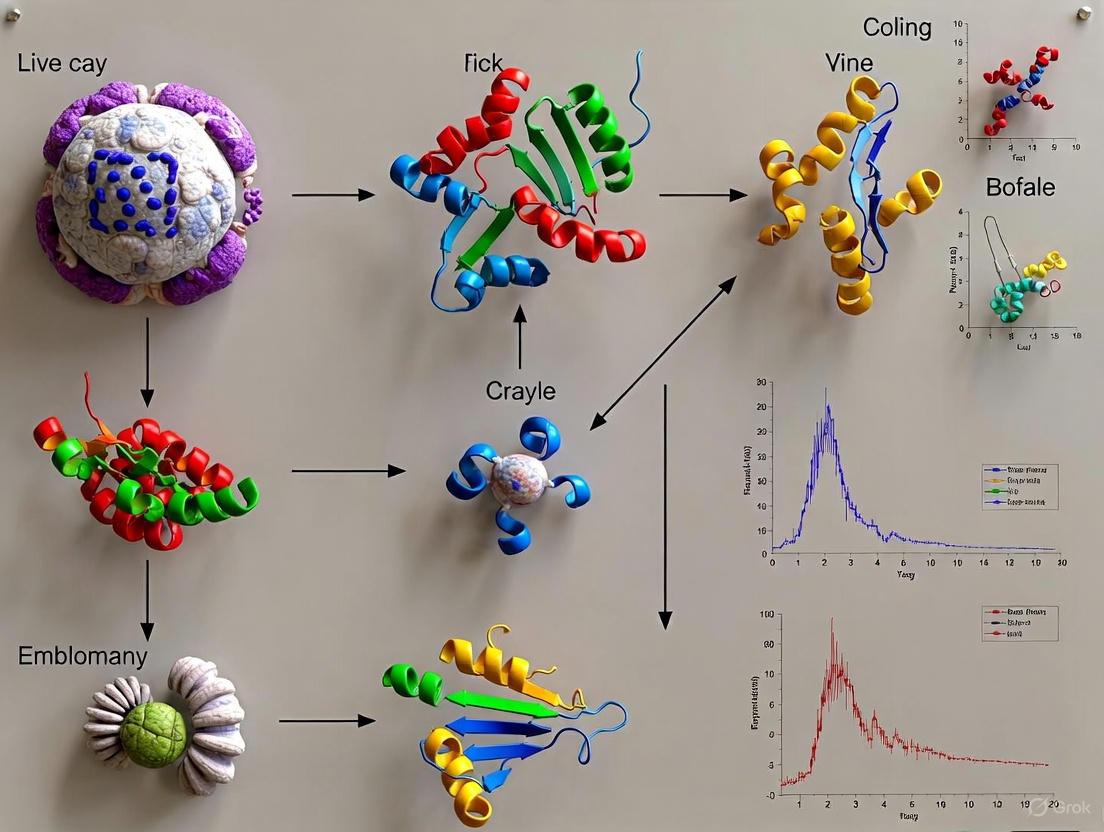

Integrated Workflow for Live Embryonic Imaging

The following diagram synthesizes the core principles and methodologies discussed into a cohesive experimental and analytical pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Live Embryo Imaging

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| FUCCI Plasmids | Genetically encoded reporter for visualizing cell cycle phase transitions in live cells [4]. | Consists of mKusabiraOrange2-hCdt1 (G1) and mAzamiGreen-hGem (S/G2/M) [4]. |

| Osmium Tetroxide | Heavy metal stain for contrasting and labeling soft tissues in fixed specimens for Micro-CT imaging [2]. | Provides high-fidelity soft tissue anatomy at resolutions of ~25 μm [2]. |

| Microinjection Setup | Delivery of molecular probes, drugs, or nucleic acids into embryos for perturbation studies [3]. | Enables temporal control over experimental interventions in live embryos [3]. |

| Light-Sheet Microscope | High-speed, optically sectioning microscope for long-term imaging of large, light-sensitive specimens with minimal photodamage [1]. | SiMView framework allows simultaneous multiview imaging [1]. |

| High-Content Image Analyzer | Automated microscope for simultaneous imaging of multiple specimens/positions, enabling high-throughput quantitative data acquisition [3]. | Allows acquisition of 6-12 embryos in a single session [3]. |

The transformation of a single fertilized egg into a complex, multicellular organism is one of the most dynamic and coordinated processes in biology. For decades, our understanding of embryonic development was pieced together from static snapshots—fixed samples representing individual time points. While this provided a foundational atlas of development, it inherently missed the continuous cellular behaviors, environmental interactions, and temporal cues that drive morphogenesis. The central thesis of this application note is that live-cell imaging transcends these limitations by enabling the quantitative, real-time observation of developmental processes, thereby revealing the fundamental mechanics that static methods cannot capture.

Technological revolutions in genetically encoded fluorescent reporters and high-speed imaging microscopy have been pivotal in this shift [4]. These tools allow researchers to move beyond inferring process from structure and instead directly witness and measure cellular dynamics throughout entire embryogenesis. This capability is transforming developmental biology from a descriptive science to a predictive one, with profound implications for understanding congenital disorders and advancing regenerative medicine.

Quantitative Live-Cell Imaging Methods

A suite of advanced imaging methods now enables the quantitative analysis of dynamic events in developing embryos. The following table summarizes the core quantitative data, key performance metrics, and primary applications of these leading technologies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Live-Cell Imaging Technologies for Developmental Biology

| Technology | Key Quantitative Metrics | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Coverage | Primary Applications in Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light-Sheet Microscopy (SiMView) [5] | Acquisition speed: ~175 million voxels/sec; Temporal resolution: ~30 seconds for entire Drosophila embryogenesis. | Very High (sec-min) | Entire embryo | Long-term, high-speed imaging of entire embryogenesis; automated cell lineage tracing. |

| Confocal Microscopy [6] | Varies by system; enables quantification of cell area and membrane intensity. | Moderate (min) | Tissue explants or regions | High-resolution imaging of epithelial cell morphology, cytoskeletal dynamics, and cell behaviors in explants. |

| FUCCI Cell Cycle Reporter [4] | Reports G1 (red), S/G2/M (green), and G1/S transition (yellow) based on fluorescence intensity. | Low to Moderate (hr) | Single-cell to whole tissues (in vivo) | Tracking cell cycle dynamics in real time; isolation of cell cycle phase-specific populations via FACS. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the process for visualizing live epithelial cells and their cytoskeleton using confocal microscopy to study cell morphology and behavior during morphogenesis.

Materials and Reagents

- Embryos: Xenopus laevis embryos, micro-injected at the 1-4 cell stage with mRNA for fluorescent markers (e.g., membrane-GFP).

- Culture Medium: Danilchik's For Amy (DFA) medium, supplemented with antibiotics and antifungics to prevent microbial growth.

- Chamber Components:

- Custom acrylic chamber or small nylon washer.

- Large cover glass (45 x 50 mm) and smaller cover slip fragments (e.g., 24 x 40 mm).

- Silicone grease.

- 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in 1/3 XMBS for coating.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Chamber Preparation: a. Use silicone grease to seal a custom acrylic chamber or a nylon washer to a large 45 x 50 mm cover glass. b. Add 1 mL of 1% BSA in 1/3 XMBS to the chamber to coat the surface. Incubate for 2-4 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. c. Just before transferring tissues, rinse and fill the chamber with DFA medium.

Tissue Isolation (Animal Cap Explant): a. Transfer injected embryos to a dish of DFA medium. b. Under a dissecting microscope, use a hair loop to support an embryo and a hair knife to make a small incision at the animal pole. c. Use repeated smooth flick cuts to extend the incision and carefully remove the cap ectoderm. d. Using a transfer pipette, move 3-4 excised explants to the prepared culture chamber.

Mounting for Imaging: a. Position each explant with the epithelium facing the bottom of the chamber. b. Dip the ends of a small cover slip fragment into silicone grease and gently place it over each explant. Apply light pressure to fix the fragment in place, taking care not to smash the explant. c. Completely fill the chamber with DFA, coat the top edges with grease, and seal the chamber with a 24 x 40 mm cover slip. Blot away any overflow.

Image Acquisition via Confocal Microscopy: a. Place the sealed chamber onto the microscope stage. b. Using a 20x objective under bright field, locate the apical ends of the superficial cells. c. Switch to a higher-power objective and fluorescence mode. d. Keep laser power as low as possible to minimize phototoxicity and capture time-lapse movies or single images.

Quantitative Analysis using ImageJ: a. Measuring Cell Area: Open the image file in ImageJ. Use the selection tool to outline a cell. Add the outline to the ROI (Region of Interest) Manager. After outlining multiple cells, click "Measure" in the ROI Manager to obtain area data for all selected cells. b. Measuring Membrane Intensity: Select the straight-line tool and draw a perpendicular line across a cell membrane. Add the line to the ROI Manager. In the "Analyze" menu, select "Plot Profile" to generate a graph of fluorescence intensities across the membrane.

Visualization of Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps of the protocol for live imaging of embryonic epithelial cells.

This protocol outlines the approach for long-term, high-speed imaging of entire embryogenesis using simultaneous multiview light-sheet microscopy (SiMView).

Materials and Reagents

- Biological Specimen: Drosophila melanogaster embryos expressing fluorescent reporters (e.g., for membranes or nuclei).

- Microscopy System: SiMView light-sheet microscope, comprising four synchronized optical arms (two for illumination, two for detection) and sCMOS cameras.

- Computational Infrastructure: High-performance computing workstations with terabytes of storage capacity and specialized software for data processing.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation and Mounting: a. Prepare Drosophila embryos of the desired developmental stage. b. Mount embryos in an appropriate medium within the imaging chamber, ensuring proper orientation for multiview acquisition.

Microscope Configuration and Data Acquisition: a. Configure the SiMView system for simultaneous dual-view illumination and detection. b. Set acquisition parameters for long-term time-lapse imaging, achieving temporal resolutions as low as 30 seconds for the entire embryo throughout development. c. Initiate acquisition, recording terabytes of multiview, time-resolved data at speeds up to 175 million voxels per second.

Computational Data Processing: a. Image Registration: Fuse the multiple simultaneous views to create a single, high-quality 3D image for each time point. b. Image Segmentation: Use computational modules to automatically identify and outline individual cells in the entire embryo. c. Cell Tracking: Lineage tracing algorithms connect segmented cells across time points to reconstruct full cell lineages and tracks.

Visualization of Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core data acquisition and processing pipeline for SiMView microscopy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful live-cell imaging in developmental biology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for these dynamic experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Live-Cell Imaging of Development

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| FUCCI Cell Cycle Reporter [4] | Visualizes cell cycle phases (G1, S, G2/M) in live cells via color changes (red/green). | Genetically encoded; based on degradation motifs of hCdt1 (G1) and hGem (S/G2/M); enables tracking of proliferation patterns in development and disease. |

| Kinase Translocation Reporters (KTRs) [4] | Reports kinase activity (e.g., Erk, JNK, p38) via nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of a fluorescent protein. | Provides readout of signaling pathway activity at single-cell resolution; ideal for studying signaling dynamics in patterning and morphogenesis. |

| PCNA-based DNA Replication Reporter [4] | Visualizes active DNA replication foci, providing a precise marker for S phase. | Distinguishes S phase from G2 phase; used for precise identification of replicating cells and analysis of replication fork dynamics. |

| Specialized Culture Media (e.g., DFA) [6] | Supports ex vivo culture and health of explanted embryonic tissues during long-term imaging. | Formulated to maintain physiological conditions; often requires addition of antibiotics/antifungics to prevent contamination. |

| sCMOS Cameras [5] | High-speed, sensitive detection of fluorescence signals in modern microscopes. | Enables fast volumetric imaging with minimal phototoxicity, crucial for capturing rapid cellular dynamics in large specimens. |

Molecular Reporters for Dynamic Cell States

A critical advancement in live-cell imaging has been the development of genetically encoded reporters that monitor specific intracellular processes. A prime example is the FUCCI system, which provides a direct visual readout of the cell cycle phase.

The FUCCI System Workflow and Mechanism

The FUCCI system leverages the cell cycle-regulated ubiquitination and degradation of two key proteins: Cdt1, which is present in G1 and degraded in S/G2/M, and Geminin, which accumulates in S/G2/M and is degraded in G1 [4]. By fusing degradation motifs from Cdt1 and Geminin to different fluorescent proteins (e.g., red and green), the system creates a color-coded cell cycle indicator.

Diagram: The FUCCI system uses fluorescent protein fusions to visualize cell cycle phases. G1 phase shows red fluorescence, S/G2/M phases show green, and the G1/S transition appears yellow due to protein overlap [4].

Applications and Limitations

The FUCCI system has been instrumental in developmental biology, revealing spatial and temporal patterns of cell cycling during organ formation and morphogenesis [4]. In cancer research, it has helped delineate cell-cycle-dependent responses to therapies [4]. Furthermore, FUCCI-expressing cells are compatible with Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), enabling researchers to isolate highly synchronous cell populations from a heterogeneous mixture for downstream transcriptomic or proteomic analysis [4].

However, the system has limitations. The original FUCCI cannot distinguish between S and G2 phases, as both are marked by Geminin, nor can it differentiate G0 quiescence from G1 [4]. Furthermore, since the original degrons are human-derived, they may not function correctly in all model organisms (e.g., zebrafish, Drosophila), necessitating the development of species-specific variants [4].

The move from static snapshots to dynamic, quantitative observation represents a paradigm shift in developmental biology. Techniques like live-cell confocal imaging of explants, high-speed light-sheet microscopy of entire embryos, and the use of molecular reporters like FUCCI provide an unprecedented, data-rich view of embryogenesis in action. These methods allow researchers to not only describe the final structure but also to understand the precise cellular behaviors, lineage relationships, and molecular cues that construct it. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of normal development and its misregulation in disease, paving the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Live-cell imaging has revolutionized our understanding of embryonic development by enabling real-time observation of dynamic cellular processes. This application note details key biological insights and methodologies for visualizing cell lineage, morphogenesis, and proliferation, framing them within the context of embryonic development research. We present integrated protocols and analytical frameworks that combine advanced microscopy, computational tools, and physiological models to address longstanding challenges in developmental biology. The approaches outlined herein provide researchers with robust methods for investigating the spatial and temporal dynamics of development, with particular emphasis on mitigating phototoxicity, enhancing imaging duration, and quantifying complex morphological parameters. These techniques have revealed critical aspects of developmental timing, cell fate decisions, and the origins of chromosomal abnormalities, offering powerful tools for both basic research and drug discovery applications.

Key Quantitative Insights from Recent Studies

Recent advances in live-cell imaging have yielded significant quantitative insights into embryonic development processes. The table below summarizes key findings from seminal studies in the field.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Insights from Live-Cell Imaging Studies

| Biological Process | Experimental System | Key Quantitative Findings | Imaging Methodology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitotic Timing & Cell Cycle | Human and mouse blastocysts | Interphase duration: 18.10±3.82h (human mural), 18.96±4.15h (human polar) vs 11.33±3.14h (mouse mural), 10.51±2.03h (mouse polar). Mitotic duration showed no significant difference (~50 min). | Light-sheet microscopy of H2B-mCherry electroporated embryos [7] | |

| Chromosome Segregation Errors | Late-stage human preimplantation embryos | Observation of de novo mitotic errors including multipolar spindle formation, lagging chromosomes, misalignment, and mitotic slippage. | Optimized light-sheet live imaging [7] | |

| Embryonic Morphogenesis | E5.5 mouse embryo | Successful in-toto single-cell tracking in a whole hemisphere for 12 hours, revealing abrupt embryonic shrinking events during monotonous growth. | Incubator-type biaxial light-sheet microscopy [8] | |

| Cell Proliferation Kinetics | Cancer cell lines (A549, SKBr3, MDA-MB-231) | Quantitative, label-free kinetic proliferation data enabling real-time growth curve generation and multi-parameter analysis. | Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System [9] |

These quantitative findings highlight critical interspecies differences in developmental timing, demonstrate the prevalence of mitotic errors in human embryogenesis, and establish benchmarks for normal developmental progression. The data provide a foundation for identifying pathological deviations in developmental processes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Live Imaging of Chromosome Dynamics in Human Blastocysts

This protocol enables visualization of chromosome segregation and mitotic errors in late-stage human preimplantation embryos, adapted from the landmark study by et al. [7].

Materials and Reagents

- Cryopreserved human blastocysts (5 days post-fertilization)

- H2B-mCherry mRNA (700-800 ng/µL)

- Electroporation system

- Light-sheet fluorescence microscope (e.g., LS2 with dual illumination/detection)

- Embryo culture media

- Specialized sample cuvette

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Embryo Thawing and Recovery: Thaw cryopreserved human blastocysts according to standard protocols and culture in appropriate medium for 2-3 hours to ensure developmental competence.

- Nuclear Labeling via mRNA Electroporation:

- Prepare H2B-mCherry mRNA solution at 700-800 ng/µL concentration.

- Transfer blastocysts to electroporation cuvette containing mRNA solution.

- Apply optimized electroporation parameters (specific voltage and pulse duration to be determined empirically for each system).

- Return electroporated embryos to culture medium and incubate for 2-4 hours to allow protein expression.

- Microscope Setup and Environmental Control:

- Configure light-sheet microscope with dual illumination and detection paths.

- Pre-warm stage chamber to 37°C and maintain 5% CO2 concentration.

- Place embryo in specialized sample cuvette with minimal medium volume (150-200 µL) to enhance stability.

- Image Acquisition:

- Set imaging parameters: 2-5 minute intervals between frames for 40-46 hours.

- Use low laser power and optimized scan speed to minimize phototoxicity [8].

- Acquire z-stacks encompassing entire embryo volume with dual-view detection.

- Post-imaging Analysis:

- Reconstruct 3D volumes from dual-view acquisitions using fusion algorithms.

- Track individual nuclei across time frames using semi-automated segmentation.

- Quantify mitotic timing, error frequency, and chromosome behavior.

Critical Technical Notes

- Electroporation efficiency for human blastocysts is approximately 41%; include sufficient embryos to ensure adequate sample size [7].

- Optimization of scan speed is more critical than irradiation intensity or frame intervals for reducing phototoxicity [8].

- Continuous monitoring of environmental conditions (temperature, CO2, humidity) is essential for embryo viability during extended imaging.

Protocol 2: Long-Term Single-Cell Tracking in Mouse Embryos

This protocol enables in-toto single-cell observation in E5.5 mouse embryos for up to 12 hours, capturing critical events in primitive body axis formation [8].

Materials and Reagents

- R26-H2B-EGFP transgenic mouse embryos (E5.5)

- Polycarbonate embedding cubes (3mm)

- Collagen I gel

- Incubator-type biaxial light-sheet microscope

- Embryo culture media

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation:

- Embed E5.5 mouse embryos in 3mm polycarbonate cubes filled with Collagen I gel.

- Secure cubes to bottom of imaging cuvette using surface tension of 150-200 µL medium.

- Microscope Configuration:

- Utilize biaxial light-sheet system with two multidirectional laser sheets and two image detectors.

- Employ two-layered incubator design: polycarbonate box enclosing microscope optics and small chamber affixed to stage.

- Validate temperature stability (±0.1°C) prior to embryo placement.

- Image Acquisition:

- Set spatial resolution to <5 µm to resolve single nuclei.

- Acquire transverse/horizontal and longitudinal/vertical images sequentially via dual-axis acquisition.

- Maintain frame rate <10 minutes to detect cell division over 12-hour period.

- Data Processing and Analysis:

- Apply 3D rendering algorithms to combine dual-axis acquisitions.

- Segment individual nuclei across time series.

- Categorize cells into epiblast, visceral endoderm, and distal visceral endoderm (DVE) populations.

- Track cell migration trajectories and quantify morphological changes.

Critical Technical Notes

- The two-layered incubator design is critical for maintaining temperature stability and reducing medium evaporation [8].

- Multidirectional laser sheets are essential for overcoming image quality deterioration at deeper embryonic regions.

- Embryo embedding in collagen gel maintains normal developmental morphology while providing mechanical stability during imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful live-cell imaging of embryonic development requires carefully selected reagents and materials that maintain viability while enabling clear visualization. The table below details essential components for these studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Live-Cell Imaging in Developmental Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Labels | H2B-mCherry mRNA, R26-H2B-EGFP transgenic line | Visualizing chromosomes and tracking nuclear positioning | mRNA electroporation preferred over viral vectors for late-stage embryos; H2B fusions provide crisp nuclear definition [7] |

| Specialized Microscopy Systems | Light-sheet microscopy (e.g., LS2, diSPIM), Incubator-type biaxial systems | Long-term imaging with minimal phototoxicity | Light-sheet microscopy reduces phototoxicity by 2-3x compared to confocal methods; integrated incubators maintain viability [7] [8] |

| Cell Culture Vessels | Specialized sample cuvettes, Polycarbonate embedding cubes | Maintaining embryo stability and normal morphology during imaging | 3mm cubic structures with collagen I gel preserve embryonic architecture [8] |

| Viability Maintenance Systems | Two-layered incubators, Environmental control chambers | Regulating temperature, CO2, and humidity during extended imaging | Two-layered design minimizes temperature fluctuations from room variations and human operation [8] |

| Image Analysis Tools | Custom deep learning models, Semi-automated segmentation pipelines | Extracting quantitative data from complex image datasets | Deep learning approaches optimized for embryo size/shape variability enable individual nucleus tracking [7] [10] |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and analytical processes for live-cell imaging in developmental studies.

Live-Cell Imaging Experimental Workflow

Live-Cell Imaging Data Analysis Pipeline

The integration of advanced live-cell imaging technologies with sophisticated computational analysis has created unprecedented opportunities for investigating cell lineage, morphogenesis, and proliferation in embryonic development. The protocols and insights presented here provide a framework for capturing dynamic developmental processes with minimal perturbation, enabling researchers to address fundamental questions in developmental biology. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield deeper understanding of developmental mechanisms and their dysregulation in disease states, ultimately informing new therapeutic strategies for developmental disorders and regenerative medicine applications.

Embryonic development is a remarkably complex process where molecular events within single cells are translated into large-scale tissue patterning and morphogenesis. Understanding this process requires observing how dynamics across different scales—from chromatin organization to cell collective movements—are interconnected. A fundamental challenge in developmental biology has been the mismatch in spatial and temporal scales: cellular processes like divisions or migrations occur in seconds to minutes, while entire morphogenetic events unfold over days or weeks [11]. Similarly, structures are organized at a molecular level (~1 nm) but form tissues at a much larger scale (~1 mm) [11]. This article presents integrated imaging and analysis frameworks that bridge these scales, enabling researchers to quantify how molecular events drive the emergence of tissue-level patterns in living embryos. We detail specific methodologies—from light-sheet microscopy of entire embryos to live-cell chromatin imaging and optogenetic patterning—that provide the temporal resolution, spatial coverage, and molecular specificity needed to decode developmental programs.

Advanced Imaging Platforms for Multiscale Analysis

Simultaneous Multiview Light-Sheet Microscopy (SiMView)

The SiMView technology framework represents a breakthrough for high-speed in vivo imaging of large specimens. This platform addresses the fundamental limitation of short optical penetration depth in conventional microscopes by deploying multiple synchronized optical arms that record complementary views of the specimen simultaneously [1]. The integrated system comprises a light-sheet microscope with four optical arms, real-time electronics for long-term sCMOS-based image acquisition at 175 million voxels per second, and computational modules for high-throughput image processing including registration, segmentation, and tracking [1].

Key Application: SiMView enables recording cellular dynamics throughout entire Drosophila melanogaster embryos with 30-second temporal resolution across full development cycles. This technology provides quantitative morphological information even for rapid global processes and supports accurate automated cell tracking in the intact early embryo [1]. The multiview approach is particularly valuable for neurodevelopment studies, where it has enabled high-resolution long-term imaging of the developing nervous system and neuroblast cell lineages in vivo.

Table 1: Performance Specifications of SiMView Technology

| Parameter | Specification | Developmental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | 30 seconds | Capturing rapid mitotic events during embryogenesis |

| Acquisition Speed | 175 million voxels/second | Comprehensive imaging of entire embryos |

| Spatial Coverage | Entire Drosophila embryo | Global analysis of morphogenetic gradients |

| Cell Tracking Accuracy | Automated tracking in early embryo | Lineage tracing and fate mapping |

Quantitative Three-Dimensional Analysis via Microcomputed Tomography

For detailed morphological analysis at intermediate developmental stages, microcomputed tomography (Micro-CT) has emerged as a powerful tool for embryonic imaging. This approach enables highly detailed, quantitative 3D dataset acquisition of embryonic chicks between 4 and 12 days of development (HH23 to HH40 stages) [2]. The protocol involves labeling with osmium tetroxide (OT) to generate sufficient soft tissue contrast for scanning at 25 μm resolution.

Quantitative Applications: This methodology establishes mathematical relationships for volumetric growth of heart, limb, eye, and brain during development. Research demonstrates that some organs exhibit constant exponential growth (eye and heart), while others display multiple growth phases (forebrain and limb) [2]. Furthermore, studies reveal that cardiac myocardial volumetric growth differs in both time- and chamber-specific manner. These quantitative baselines enable comparison of genetic or experimental perturbation effects on morphogenesis.

Molecular-Scale Imaging: Chromatin Dynamics and Enhancer-Promoter Interactions

CRISPR PRO-LiveFISH for Non-Repetitive Genomic Loci

Understanding how genome organization influences developmental programs requires visualizing specific genomic loci in living cells. CRISPR PRO-LiveFISH (Pooled gRNAs with Orthogonal bases LiveFISH) combines orthogonal bases from expanded genetic alphabet technology with rational sgRNA design to efficiently label multiple non-repetitive loci [12]. This optimized method allows simultaneous imaging of up to six genomic loci using as few as 10 sgRNAs for non-repetitive loci imaging without signal amplification.

Key Findings: This technology has revealed that enhancer-promoter interactions may persist despite spatial mobility and identified that BRD4 maintains super-enhancer contacts regulating MYC oncogene expression in cancer cells [12]. The method demonstrates broad applicability across diverse cell types, including primary cells, enabling studies of correlation between genomic dynamics and epigenetic states.

Super-Resolution Live-Cell Imaging of Chromatin Domains

By combining photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) with single-nucleosome tracking, researchers have developed a nuclear imaging system to visualize higher-order chromatin structures alongside their dynamics in live mammalian cells [13]. This approach revealed that nucleosomes form compact domains with a peak diameter of approximately 160 nm and move coherently in live cells.

Developmental Insights: Heterochromatin-rich regions show more domains and less movement. With cell differentiation, the domains become more apparent with reduced dynamics [13]. Perturbation experiments indicate these structures are organized by a combination of factors including cohesin and nucleosome-nucleosome interactions. These domains persist through mitosis, suggesting they act as building blocks of chromosomes and may serve as information units throughout the cell cycle.

Protocol: Drosophila Embryo Preparation and Microinjection for Live-Cell Microscopy

This protocol adapts the Drosophila embryo for high-content imaging on plates, generating experimental sample sizes sufficient for quantitative analysis of cellular processes in an intact organism.

Equipment and Reagent Setup

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Automated high-content image analyzer | Simultaneous multi-embryo time-lapse acquisition | Enables parallel imaging of 6-12 embryos |

| Drosophila embryo collection cages | Maintain population for embryo production | Use fresh flies transferred when pupae darken at P14 stage [3] |

| Microinjection system | Delivery of molecular probes, drugs | Provides temporal control for perturbation studies |

| Image analysis software | Quantitative analysis of cell behaviors | Custom scripts for morphological analysis |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Embryo Collection and Preparation:

- Maintain population cages with fresh flies, transferring when pupae begin to darken at stage P14 (approximately 14 days post-egg laying at 20°C) [3].

- Allow pupae to eclose and populate bottles for 12-24 hours before transferring fresh flies to small collection cages.

- Collect embryos at appropriate developmental stages using standard apple juice agar plates.

- Dechorionate embryos manually or chemically and mount on appropriate imaging chambers.

Microinjection for Live-Cell Imaging:

- Prepare molecular probes (fluorescent markers, drug inhibitors, etc.) in appropriate injection buffers.

- Align embryos on microscope slides or imaging chambers with specialized double-sided tape.

- Desiccate embryos slightly to prevent backflow during injection.

- Perform microinjection using calibrated injection systems to deliver precise volumes.

- Cover embryos with halocarbon oil to prevent dehydration during time-lapse imaging.

Image Acquisition on High-Content Platform:

- Program automated microscope for multipoint acquisition across multiple embryo positions.

- Set appropriate temporal resolution based on biological process (typically 30-60 second intervals).

- Acquire multi-position time-lapses with sufficient spatial resolution to resolve subcellular structures.

- Implement focus maintenance systems during extended time-lapse acquisitions.

Applications and Limitations

This protocol has been successfully applied to investigate mechanisms driving morphological changes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) during mitosis [3]. The approach revealed the role of microtubules and cytoskeletal factors in mitotic ER reorganization using the syncytial cortical division in the early Drosophila embryo. The system is particularly well-suited for studying biological events occurring within approximately 100 microns of the Drosophila embryo cortex over extended periods. The main limitations include accessibility to deeper tissues and the challenge of tracking individual cells in highly migratory populations.

Computational Framework: Learning Developmental Mode Dynamics from Single-Cell Trajectories

Translating high-dimensional imaging data into predictive models requires sophisticated computational approaches. A recently developed framework combines mode decomposition ideas from physics with sparse dynamical systems inference to learn quantitative continuum models from single-cell imaging data [14].

Application to Zebrafish Gastrulation: This approach has been applied to pan-embryo cell migration during early gastrulation in zebrafish, where thousands of cells undergo coordinated movements to establish the body plan. The method involves:

- Projecting cell positions and velocities onto a spherical mid-surface

- Converting discrete cell data into continuous density and flux fields through consistent coarse-graining

- Representing these fields using spherical harmonic basis functions

- Inferring dynamical equations for the dominant modes

This framework successfully identified that cell migration during zebrafish gastrulation shares similarities with active Brownian particle dynamics on curved surfaces [14]. The approach compresses developmental cell trajectory data into interpretable hydrodynamic models that capture essential ordering principles.

Diagram 1: Computational analysis pipeline for developmental cell trajectories

Optogenetic Patterning: μPatternScope for Spatiotemporal Control of Cell Behavior

Bridging molecular events to tissue-level patterning requires not only observation but also active intervention. The μPatternScope (μPS) framework enables precise spatiotemporal control over engineered cells using dynamic light patterns [15].

System Components and Setup

Hardware Configuration:

- Digital micromirror device (DMD) with 2+ million tilt-capable micromirrors (1080p resolution)

- Telecentric optical engine to homogenize and guide incident light from high-power LED

- Liquid light guide assembly for flexible light source attachment

- Modular optical path mounting to standard microscope episcopic-illumination port

Software Architecture:

- Modular MATLAB-based control software

- Integration with YouScope open-source microscope control platform

- Functions for automated experiment scripting

- Real-time image analysis and feedback control capabilities

Application to Programmed Cell Death Patterning

The μPS system has been combined with engineered ApOpto mammalian cells containing a blue light-inducible apoptosis circuit. This integrated system enables:

- Precise spatial induction of apoptosis through patterned blue light illumination

- Dynamic feedback control between measured cell patterns and illumination profiles

- Complex pattern formation through controlled cell elimination

- Real-time adjustment of stimulation based on observed outcomes

This technology demonstrates how optogenetic intervention at the molecular level (apoptosis induction) can generate defined tissue-level patterns, effectively bridging scales through controlled experimental manipulation [15].

Diagram 2: Optogenetic patterning with feedback control

Integrated Workflow: From Molecular Perturbation to Tissue-Level Phenotyping

Combining these technologies creates a powerful integrated workflow for bridging scales in developmental biology research:

- Molecular Perturbation: Use CRISPR-based tools or optogenetic controls to manipulate specific molecular processes [12] [15].

- Live Imaging: Implement multiview light-sheet microscopy or high-content screening to capture resulting dynamics across scales [3] [1].

- Quantitative Analysis: Apply mode-based computational frameworks to extract meaningful patterns from high-dimensional data [14].

- Model Inference: Derive predictive models that connect molecular interventions to tissue-level outcomes.

This integrated approach enables researchers to move beyond correlation to causation in understanding how molecular events drive tissue patterning during embryonic development.

Table 3: Technology Combinations for Multiscale Analysis

| Molecular Scale Tool | Tissue Scale Tool | Integrated Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR PRO-LiveFISH [12] | Light-sheet microscopy [1] | Linking chromatin dynamics to cell fate decisions |

| Optogenetic apoptosis induction [15] | High-content imaging [3] | Testing tissue self-organization principles |

| Single-nucleosome tracking [13] | Zebrafish embryo tracking [14] | Connecting chromatin organization to cell migration |

The technologies and methodologies presented here provide researchers with an integrated toolkit for bridging the critical gap between molecular events and tissue-level patterning in embryonic development. From high-throughput whole-embryo imaging to targeted optogenetic perturbation and computational modeling, these approaches enable quantitative analysis of developmental processes across spatial and temporal scales. As these technologies continue to evolve—particularly through improvements in spatial resolution, molecular multiplexing, and computational analytics—they promise to unlock deeper insights into how coordinated molecular interactions give rise to the exquisite patterns and structures of developing organisms. The protocols and applications detailed here provide a roadmap for researchers seeking to implement these approaches in their investigation of developmental mechanisms.

The study of embryonic development has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the shift from analyzing fixed specimens to observing dynamic processes in living organisms. Traditional methods relying on static snapshots of fixed tissues provided limited insights into the temporal sequence and cellular dynamics fundamental to embryogenesis. This paradigm shift to live cell imaging has been driven by significant technological advancements that enable researchers to observe, record, and quantify developmental processes in real-time, at single-cell resolution, and within the intact embryonic context. Framed within a broader thesis on live cell imaging in embryonic development research, this article details how modern approaches overcome historical limitations, providing application notes and protocols that empower researchers and drug development professionals to capture the dynamic landscape of embryogenesis.

Historical Limitations of Fixed Specimen Analysis

Traditional developmental biology relied heavily on the analysis of fixed and sectioned specimens. While these methods provided foundational knowledge, they introduced significant limitations that constrained our understanding of developmental dynamics.

- Lack of Temporal Resolution: Fixed samples offer only static snapshots of dynamic processes, making it impossible to observe the sequence and timing of cellular events [4]. This is particularly problematic for understanding rapidly changing processes like cell division, migration, and fate determination.

- Artifacts from Fixation and Processing: Chemical fixation can alter cellular morphology and protein localization, while histological processing may introduce physical distortions that do not reflect the living state [16].

- Population Averaging: Traditional methods often require pooling multiple fixed embryos at different developmental stages to reconstruct a timeline, obscuring natural variability between individuals [4].

- Inability to Study Rare or Transient Events: Without continuous observation, rare cellular events or transient developmental states are easily missed in fixed samples [5].

- Disruption of Native Microenvironment: Fixation disrupts the native physiological context, including cell-cell interactions, signaling gradients, and mechanical forces that guide development [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Fixed-Specimen Methods vs. Modern Live-Cell Imaging Approaches

| Aspect | Fixed Specimen Analysis | Live-Cell Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Static snapshots | Continuous, real-time dynamics [4] |

| Cellular Context | Disrupted native environment | Preservation of native microenvironment [6] |

| Data Type | Inferential timeline reconstruction | Direct observation of temporal sequences [4] |

| Artifact Potential | High (fixation, processing) | Lower (minimal perturbation) [16] |

| Single-Cell Tracking | Not possible | Enabled throughout development [5] |

| Experimental Throughput | Manual processing of multiple samples | Automated, high-speed acquisition [5] |

Technological Advances Enabling Live Imaging of Embryos

The transition to living specimen imaging has been facilitated by several interdependent technological innovations that collectively address the challenges of maintaining embryo viability while capturing high-quality spatial and temporal data.

Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Reporters

The development of genetically encoded fluorescent reporters has been transformative for tracking specific cellular events and states in living embryos. The Fluorescent Ubiquitination-based Cell Cycle Indicator (FUCCI) system stands as a landmark achievement, allowing visual monitoring of cell cycle progression in real-time [4]. The FUCCI system relies on cell cycle-controlled degradation of Cdt1 (accumulated in G1 phase) and Geminin (accumulated in S/G2/M phases) fused to fluorescent proteins, creating distinct color signatures for different cell cycle phases [4]. More recent advancements include kinase translocation reporters for signaling activity and DNA replication foci-based reporters for precise S-phase mapping [4]. These tools enable researchers to correlate developmental events with cell cycle status and signaling dynamics without disrupting native physiology.

Advanced Microscopy Modalities

Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) has emerged as a particularly powerful modality for embryonic imaging due to its unique combination of speed, low phototoxicity, and optical sectioning capability. The SiMView (Simultaneous Multi-View) framework exemplifies this advancement, incorporating four synchronized optical arms for simultaneous multiview imaging of entire Drosophila melanogaster embryos at speeds up to 175 million voxels per second [5]. This technology enables continuous imaging throughout embryonic development with temporal resolution of 30 seconds, capturing global processes and enabling automated cell tracking in the early embryo [5]. Both one-photon and multiphoton implementations have been developed, balancing penetration depth with resolution for different experimental needs.

Computational and Analytical Infrastructure

The massive data streams generated by high-speed live imaging – often terabytes per specimen – require sophisticated computational infrastructure for management, processing, and analysis [5]. Modern workflows incorporate automated image registration algorithms to align multiview data, segmentation tools for identifying cellular boundaries, and tracking modules for following cells through time and space [5]. These computational approaches have been integrated into accessible software platforms like ImageJ, which provides tools for quantifying morphological parameters such as cell area and membrane intensity in time-lapse datasets [6].

Diagram Title: Live Cell Imaging Computational Workflow

Application Notes: Experimental Considerations for Embryonic Live Imaging

Successful live imaging of embryonic development requires careful consideration of multiple experimental parameters to balance image quality with specimen viability.

Maintaining Embryonic Viability During Imaging

Long-term imaging requires meticulous attention to environmental conditions throughout data acquisition. Specimens must be maintained at appropriate temperature, pH, and gas concentrations specific to the organism. For Xenopus laevis embryonic epithelial cells, specialized chambers sealed with cover slips and filled with DFA culture medium enable long-term culture for at least 24 hours at room temperature [6]. The addition of antibiotics and antifungals to culture media is essential to discourage microbial growth without adversely affecting embryonic development [6]. Mechanical stabilization is equally critical – for explained tissues, gentle positioning under cover slip fragments with careful attention to avoid excessive pressure that can damage delicate structures [6].

Optimizing Image Acquisition Parameters

The conflicting demands of spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and phototoxicity require careful optimization for each experimental system. Key principles include using the lowest laser power sufficient for detectable signal, maximizing camera sensitivity through appropriate gain settings, and selecting the longest practical time intervals between acquisitions [6]. For tracking rapid cellular dynamics in early embryogenesis, temporal resolutions of 30-60 seconds often suffice, while faster processes may require higher frequency imaging [5]. The choice between confocal, light-sheet, or widefield microscopy should be guided by the required resolution, penetration depth, and sensitivity to photodamage for the specific biological question and embryonic stage.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Live Imaging Technologies for Embryonic Development

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Penetration Depth | Phototoxicity Impact | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield Microscopy | Moderate | Very High | Shallow | Moderate | Rapid surface events [17] |

| Confocal Microscopy | High | High | Moderate | High | High-resolution subcellular [6] |

| Light-Sheet Microscopy | Moderate-High | Very High | Deep | Low | Long-term whole embryo [5] |

| Multiphoton Microscopy | High | Moderate | Very Deep | Low | Deep tissue imaging [5] |

Protocols: Methodologies for Live Imaging of Embryonic Epithelia

Protocol 1: Live-Cell Imaging and Quantitative Analysis of Embryonic Epithelial Cells inXenopus laevis

This protocol enables real-time observation of cell behaviors, polarity development, and shape changes during epithelial morphogenesis.

Materials and Reagents:

- Custom acrylic chamber or nylon washer

- 45 × 50 mm cover glass

- 1% BSA in 1/3 XMBS

- DFA medium

- Transfer pipette with slanted opening

- Fine forceps

- Hair loop and hair knife

- Silicone grease

- Embryos microinjected with desired mRNA at 1-4 cell stage

Procedure:

- Chamber Preparation: Seal chamber to cover glass using silicone grease. Add 1 mL of 1% BSA in 1/3 XMBS to coat chamber and cover slip fragments. Incubate 2-4 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [6].

- Medium Exchange: Rinse and fill chamber with DFA medium immediately before transferring specimens [6].

- Tissue Explanation: Transfer embryos to dish of DFA. Using forceps to stabilize embryo with hair loop, make incision at animal pole with hair knife. Extend incision with flick cuts to remove cap ectoderm [6].

- Specimen Mounting: Transfer 3-4 explants to chamber using transfer pipette. Position with epithelium facing bottom. Dip cover slip fragment ends in silicone grease and place over each explant, avoiding excessive force [6].

- Chamber Sealing: Completely fill chamber with DFA. Coat top edges with silicone grease and seal with 24 × 40 mm cover slip. Adjust DFA level to reduce bubbles [6].

- Image Acquisition: Position chamber on confocal microscope stage with balancing weights. Using 20× objective initially, locate apical ends of superficial cells under brightfield. Switch to fluorescence and higher power objective for time-lapse acquisition with minimal laser power [6].

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Cell Area Measurement: In ImageJ, outline cells with selection tool. Add outlines to ROI manager (Ctrl+T). Save ROI set and measure areas [6].

- Membrane Intensity: Draw perpendicular line across membrane with straight line tool. Add to ROI manager. Use Plot Profile for intensity measurements across the membrane [6].

Protocol 2: Live Cell Imaging for Keratinocyte Lineage Tracing

This approach enables studies of division kinetics, cell cycle duration, and division fates at single-cell resolution.

Materials and Reagents:

- Unpassaged human keratinocytes

- Culture media without antibiotics (to avoid growth and differentiation suppression)

- Clonal density culture vessels

- Appropriate extracellular matrix coatings

- Time-lapse imaging system with environmental control

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Utilize unpassaged human keratinocytes to minimize culture environment influences. Avoid serial passaging which alters gene expression and proliferation rates [16].

- Clonal Density Culture: Plate keratinocytes at clonal density to enable single-cell analysis and lineage tracing [16].

- Image Acquisition: Record divisions using time-lapse photography with appropriate environmental control (temperature, CO₂) [16].

- Data Analysis: Construct lineage trees from division records. Determine cell cycle duration and division fates of individual keratinocytes [16].

- Assessment: Quantify proliferation, differentiation, and cell cycle duration from lineage trees [16].

Diagram Title: Lineage Tracing Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Live Embryo Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FUCCI System | Visualizes cell cycle phases via fluorescently-tagged Cdt1 (G1) and Geminin (S/G2/M) [4] | Cannot distinguish S/G2 phases or G0/G1; requires species-specific degradation motifs [4] |

| DFA Medium | Supports long-term culture of explained tissues during imaging [6] | Requires addition of antibiotics/antifungals; maintain at room temperature [6] |

| Dispase Solution | Matrix metalloprotease for gentle epidermal separation from dermis [16] | Preserves integrity of epithelial sheets for culture; alternative to harsh enzymatic treatments [16] |

| BSA Coating | Prevents adhesion of explants to glass surfaces [6] | Use at 1% concentration; incubate 2-4 hours at room temperature [6] |

| Silicone Grease | Creates sealed imaging chambers while maintaining viability [6] | Enables long-term culture without contamination or medium evaporation [6] |

The shift from fixed to living specimens represents one of the most significant advancements in developmental biology, transforming our understanding of embryonic development from a series of static states to a dynamic continuum. The technologies and protocols detailed here – from genetically encoded reporters like FUCCI to advanced imaging platforms like SiMView light-sheet microscopy – provide researchers with powerful tools to investigate developmental processes with unprecedented temporal and spatial resolution. As these technologies continue to evolve, particularly with integration of artificial intelligence for image analysis and the development of increasingly sensitive fluorescent reporters, live imaging will undoubtedly uncover new principles of embryonic development and provide deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying birth defects, regenerative processes, and evolutionary developmental biology. For drug development professionals, these approaches offer new paradigms for assessing teratogenic effects and therapeutic interventions in real-time within developing systems.

Advanced Tools and Techniques: A Practical Guide to Live Embryonic Imaging

Live-cell imaging is an indispensable tool in modern developmental biology, enabling researchers to observe the dynamic processes of embryonic development in real time. The choice of microscopy technique is pivotal, as it directly influences the quality of the acquired data and the viability of the delicate living specimens. For researchers studying embryonic development, the primary challenge lies in balancing the need for high-resolution, high-contrast images with the imperative to minimize phototoxicity and maintain embryo health throughout the experiment [18]. This application note provides a structured comparison of three fundamental imaging modalities—widefield, confocal, and light-sheet microscopy—framed within the context of live embryonic imaging. We present quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and reagent solutions to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate technology for their specific investigations in embryonic development and drug screening applications.

Core Imaging Technologies: Principles and Trade-offs

The fundamental differences in how microscopes illuminate the specimen and collect light give rise to their unique performance characteristics, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Core Principles of Major Live-Cell Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Core Illumination Principle | Optical Sectioning | Key Technical Differentiator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield Fluorescence | The entire specimen is flooded with excitation light simultaneously [19]. | No | The entire specimen is illuminated, and light from above and below the focal plane is collected, often creating background haze [18] [20]. |

| Laser Scanning Confocal (LSCM) | A single, focused laser spot is scanned across the specimen in a raster pattern [19] [20]. | Yes | A physical pinhole in the detection path blocks out-of-focus light, ensuring only light from the focal plane is detected [18] [20]. |

| Spinning Disk Confocal (SDCM) | A disk with thousands of pinholes sweeps across the specimen, illuminating multiple points simultaneously [19] [18]. | Yes | Enables high-speed imaging by parallelizing the point-scanning process, but can suffer from pinhole crosstalk in thick samples [18] [20]. |

| Light-Sheet Fluorescence (LSFM) | A thin sheet of light illuminates only the focal plane of the detection objective [21] [22] [23]. | Yes (intrinsic) | Illumination and detection paths are orthogonal. This geometry ensures that only the imaged plane is exposed to light, drastically reducing photodamage [24] [23]. |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Selecting a microscope requires a clear understanding of its performance metrics. The following table summarizes critical parameters for imaging live embryos, and recent research provides a direct, quantitative comparison of the impact of these modalities on embryonic health.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Live Embryo Imaging

| Performance Metric | Widefield Fluorescence | Laser Scanning Confocal (LSCM) | Spinning Disk Confocal (SDCM) | Light-Sheet Microscopy (LSFM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Speed | High | Slow (seconds per frame) [18] | Very High (30 fps or faster) [18] | Highest [22] |

| Z-Resolution / Optical Sectioning | Poor [19] | Excellent | Good (can degrade in thick samples) [20] | Excellent [23] |

| Photobleaching & Phototoxicity | Moderate | High [24] [18] | Moderate | Very Low [24] [23] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Low (high background) [18] | High | High | Very High [22] [23] |

| Penetration Depth | Limited | Good | Good | Excellent [22] |

| Multi-dimensional Imaging | Good | Good | Excellent for fast dynamics | Excellent for long-term imaging |

A landmark 2024 study directly compared the biological safety of LSFM and LSCM for imaging mammalian embryos by using DNA damage as a sensitive indicator of photodamage. The findings offer critical, quantitative guidance for modality selection.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of DNA Damage in Embryos after Imaging (Adapted from Chow et al., 2024 [24])

| Imaging Parameter | Laser Scanning Confocal | Light-Sheet Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Time for 3D Volume Acquisition | ~30 minutes | ~3 minutes (10x faster) |

| Achieved Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | 15.75 ± 1.90 | 15.45 ± 3.45 (Matched) |

| Induced DNA Damage (γH2AX assay) | Significantly higher | No significant increase vs. non-imaged controls |

| Photobleaching Rate | Higher | Reduced |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Live Imaging of Mouse Embryo Yolk Sac Vasculature

The following protocol exemplifies the application of confocal microscopy for a specific developmental process, detailing the steps from sample preparation to image acquisition.

Background and Application

This protocol is designed for visualizing the dynamic morphogenesis of the vasculature and hemodynamics in the mouse embryonic yolk sac, providing insights into cell migration, proliferation, and cell-cell interactions in live, developing embryos [25].

Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Live Embryo Imaging

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporter Mouse Models | Genetically encoded labels for specific structures (e.g., blood vessels). | Essential for confocal and light-sheet imaging to provide contrast [25]. |

| Specialized Embryo Culture Medium | Supports ex utero development during imaging. | Must maintain precise temperature, pH, and gas conditions [18]. |

| Environmental Chamber | Maintains embryo viability on microscope stage. | Controls temperature, CO₂, and humidity [18]. |

| Agarose (Low Gelling Temperature) | For mounting and immobilizing embryos. | Used to create agarose columns or hemispheres for light-sheet microscopy [23]. |

| Custom-Mounted Sample Holders | Physical support for embryos in light-sheet microscopes. | Cylinder-shaped elements made of metal, plastic, or glass [23]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Utilize transgenic fluorescent protein reporter mouse models that label yolk sac blood vessels.

- Carefully dissect mouse embryos at the desired developmental stage (e.g., E7.5-E9.5) with the yolk sac intact.

- Transfer the embryo into a pre-warmed, gas-equilibrated specialized culture medium.

Mounting:

- For confocal microscopy, place the embryo in a glass-bottom dish or an appropriate chamber slide filled with culture medium.

- For light-sheet microscopy, mount the embryo in a low-melting-point agarose column or a custom-made holder like a "cobweb holder" to suspend the sample between the illumination and detection objectives [23].

Microscope Setup:

- Place the mounting dish or holder into the environmental chamber on the microscope stage. Allow the system to stabilize to 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Select appropriate objectives. A high-NA water or silicone immersion objective (e.g., 20x or 40x) is often used for confocal. Light-sheet setups use separate, perpendicular illumination and detection objectives.

- Set the laser power to the minimum necessary to achieve a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio to minimize phototoxicity [18].

- Configure acquisition parameters for time-lapse imaging: define Z-stack range (e.g., to cover the yolk sac volume), step size (e.g., 1-2 µm), and time intervals (e.g., 1-5 minutes) depending on the dynamic process being studied.

Image Acquisition:

- Begin the time-lapse experiment. For confocal, a single Z-stack may take several minutes. For light-sheet, the same volume can be acquired in a fraction of the time [24].

- Monitor embryo health throughout the experiment. Signs of phototoxicity include developmental arrest or morphological changes.

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Use image analysis software (e.g., FIJI/ImageJ, Imaris) to process the 4D dataset (x, y, z, t).

- Perform tasks such as maximum intensity projection, 3D rendering, and kymograph analysis to visualize and quantify vascular remodeling and blood flow.

Advanced Modality: Light-Sheet Microscopy for Embryonic Development

Light-sheet microscopy has rapidly emerged as the method of choice for long-term, high-resolution imaging of embryonic development due to its unique combination of speed and low phototoxicity [21] [22].

Key Advantages for Embryology

- Low Photodamage: By illuminating only the plane being imaged, LSFM drastically reduces the light dose to the embryo. A 2024 study confirmed that LSFM, unlike confocal microscopy, did not induce significant DNA damage in mammalian embryos under equivalent imaging conditions [24].

- High Imaging Speed: The ability to capture an entire plane at once allows for very fast volumetric imaging, essential for capturing rapid developmental events.

- Long-Term Viability: The reduced phototoxicity enables time-lapse imaging over several days, allowing observation of complete processes like pre-implantation development [21] or nearly the entire embryonic morphogenesis of insects like Tribolium castaneum [23].

Technical Considerations and Mounting

A key aspect of LSFM is sample mounting, as the embryo must be suspended in a medium and rotated between two perpendicular objectives. Protocols have been developed to overcome the challenge of suspending the sample, which can involve gel confinement or custom-designed chambers that allow embryos to be imaged within a standard microdrop of culture medium under oil [21]. Standardized mounting techniques include agarose columns, agarose hemispheres, and novel holders like the "cobweb holder" for insects [23].

The choice between widefield, confocal, and light-sheet microscopy for live embryonic imaging is a strategic decision that balances spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and specimen viability. Widefield microscopy remains a valid choice for thin samples or when high speed is needed and optical sectioning is not critical. Confocal microscopy, particularly spinning disk systems, offers a robust solution for many 3D imaging applications requiring good resolution and speed. However, for the most demanding long-term live imaging studies of embryonic development, where minimizing photodamage is paramount, light-sheet fluorescence microscopy has proven to be a superior technology. Its ability to deliver high-speed volumetric imaging with minimal impact on embryo health and development makes it an powerful tool for revolutionizing our understanding of the dynamic processes that shape life.

Live cell imaging of embryonic development represents a cornerstone of modern developmental biology, enabling the direct observation of the dynamic processes that shape a multicellular organism [26]. Central to this capability are fluorescent labeling strategies that allow researchers to mark and track specific molecules, cells, and structures within living systems. The field has evolved from methods that introduce fluorescent markers into cells toward sophisticated genetic encoding of fluorescence, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific experimental needs in embryonic research [27] [26]. This article provides a comprehensive overview of two fundamental labeling paradigms—electroporation-based delivery and genetically encoded reporters—framed within the context of live imaging of embryonic development. We present optimized protocols, quantitative comparisons, and practical guidance to empower researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate labeling strategies for their specific investigations into the intricate processes of embryogenesis.

Electroporation-Based Delivery of Fluorescent Probes

Electroporation has been successfully adapted as a versatile technique for introducing fluorescently labeled biomolecules into living cells, including those of embryonic systems. This method utilizes short electrical pulses to create transient pores in cell membranes, allowing passage of molecules that would otherwise not cross the lipid bilayer [28].

Optimized Electroporation Protocol for Protein Internalization

Based on method development for internalizing fluorescently labeled proteins into live E. coli [28], with adaptations for mammalian embryonic cells:

- Sample Preparation: Fluorescently labeled proteins should be dialyzed into electroporation-compatible buffers (e.g., 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT) to remove high salts that may cause arcing. Remove unincorporated dye through affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA resin for His-tagged proteins) [28].

- Cell Preparation: Use electrocompetent cells diluted 1:1 in water. For embryonic cells, appropriate enzymatic treatment may be required to create single-cell suspensions while preserving viability.

- Electroporation Parameters: Add fluorescently labeled protein (50 nM–2.5 μM final concentration) to cell suspension in pre-chilled electroporation cuvettes. Apply electrical pulse (1.0–1.8 kV for bacterial systems; mammalian embryonic cells typically require lower voltages). Higher voltages increase internalization but reduce cell viability [28].

- Post-Electroporation Processing: Immediately after pulsing, recover cells with pre-warmed culture medium for 3 minutes at 37°C. Pellet cells (1 min at 3,300×g, 4°C) and wash with PBS containing 100 mM NaCl and 0.005% Triton X-100 to remove non-internalized molecules [28].

VANIMA: Electroporation of Labeled Antibodies

The VANIMA (Versatile Antibody-Based Imaging Approach) protocol enables visualization of endogenous proteins and posttranslational modifications in living metazoan cell types [29]:

- Antibody Preparation: Digest antibodies to generate Fab fragments using papain-coated magnetic beads to reduce size and improve nuclear access. Label with fluorescent dyes using commercial labeling kits (e.g., AlexaFluor-488 antibody labeling kit).

- Electroporation Delivery: Use specialized electroporation systems (e.g., Neon Transfection System) to introduce labeled antibodies/Fabs into cells. Efficiency exceeds 90% in human cancer cell lines like U2OS with viability >90% [29].

- Imaging: Transduced antibodies bind endogenous targets, with nuclear localization achieved either via "piggyback" transport with the target protein or through free diffusion of Fabs.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Electroporation-Based Delivery

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low internalization efficiency | Insufficient voltage or improper buffer conditions | Optimize voltage gradient; ensure low-salt buffers |

| High cell death | Excessive voltage or pulse duration | Reduce voltage; shorten pulse duration; ensure proper cooling |

| Persistent background fluorescence | Inadequate removal of non-internalized molecules | Enhance washing stringency with detergent-containing buffers |

| Protein aggregation or precipitation | Incompatible storage buffer | Dialyze into electroporation-compatible buffers before use |

Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Reporters

Genetically encoded fluorescent reporters have revolutionized live imaging by enabling non-invasive monitoring of dynamic processes in developing embryos [27] [26]. These tools convert the detection of specific biological parameters into observable fluorescent signals that can be tracked in real-time.

Design Principles for Fluorescent Reporters

The construction of effective genetically encoded fluorescent reporters follows several key design principles [27]:

- Full-Length Protein Fusions: Direct fusion of fluorescent proteins to full-length cellular proteins reports on localization, synthesis, and turnover.

- FRET-Based Sensors: Sandwiching a conformationally sensitive protein between FRET pairs (e.g., CFP/YFP) enables detection of conformational changes or protein-protein interactions.

- Molecular Switches: Sensing elements that change localization or conformation in response to specific biochemical analytes can be coupled to reporting elements.

Quantitative Assessment of Fluorescent Proteins

Selection of appropriate fluorescent proteins requires consideration of multiple photophysical properties. Based on quantitative characterization of over 40 FPs [30]:

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Selected Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Relative Brightness | Photostability | pKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCerulean (CFP) | 433 | 475 | 0.35 | Medium (α=1.12) | 4.7 |

| EGFP | 488 | 507 | 1.00 | Medium (α=1.29) | 6.0 |

| mVenus (YFP) | 515 | 528 | 1.57 | Medium (α=1.13) | 6.0 |

| mKO2 (Orange) | 551 | 565 | 1.10 | High | 5.6 |

| mCherry (Red) | 587 | 610 | 0.47 | Medium (α=1.38) | 4.5 |

| mCardinal (Far-Red) | 604 | 659 | 0.40 | High | 4.8 |

Note: Relative brightness normalized to EGFP; Photostability represented as accelerated photobleaching factor (α), with lower values indicating less acceleration at higher illumination power.

Critical Considerations for Embryonic Imaging

- Phototoxicity Management: Fluorescent protein photobleaching follows accelerated kinetics, especially under laser scanning conditions. This is particularly critical for long-term imaging of light-sensitive embryonic tissues [30].

- Expression Optimization: For embryonic studies, FPs can be introduced via transgenesis, gene targeting in embryonic stem cells, or BAC modification. The lack of enzymatic amplification means low expression levels may not be detectable [26].