Live Imaging of Embryonic Development: A Comparative Guide to Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of live imaging techniques for studying embryo development, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Live Imaging of Embryonic Development: A Comparative Guide to Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of live imaging techniques for studying embryo development, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of established and emerging technologies, including light-sheet, confocal, and Brillouin microscopy. The content explores methodological applications from basic research to clinical IVF, addresses critical troubleshooting for phototoxicity and sample viability, and offers a direct validation of techniques based on recent studies. The synthesis aims to guide the selection of optimal imaging strategies for specific developmental questions and preclinical applications.

The Why and What: Core Principles and the Expanding Toolbox of Embryo Live Imaging

The Paradigm Shift from Static to Dynamic Analysis in Developmental Biology

For decades, developmental biology relied on static analytical methods that provided snapshots of biological processes. Traditional techniques like histology and fixed-tissue microscopy offered valuable structural information but could not capture the dynamic, continuous nature of embryonic development. The paradigm has now shifted toward dynamic live imaging approaches that enable researchers to observe developmental processes in real-time within living organisms. This transformation has been driven by advances in imaging technology, computational analysis, and sample preparation methods that collectively provide unprecedented insight into the temporal dimension of biological systems.

Comparative Analysis of Static vs. Dynamic Methodologies

Fundamental Limitations of Static Approaches

Static analysis in developmental biology encompasses techniques that capture biological information at a single fixed time point. These include conventional histology, fixed-sample imaging, and end-point biochemical assays. While these methods have contributed substantially to our understanding of embryonic architecture, they suffer from significant limitations:

- Inability to observe temporal processes including cell migration, division dynamics, and fate determination

- Specimen alteration through fixation and processing artifacts

- Inference of dynamics from multiple static samples rather than direct observation

- Limited understanding of causality in developmental processes

The emergence of sophisticated live imaging technologies has addressed these limitations by enabling continuous, non-invasive observation of developing embryos across multiple temporal and spatial scales.

Quantitative Comparison of Imaging Modalities

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Developmental Biology Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Imaging Depth | Key Applications in Developmental Biology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM) | Subcellular (~1μm) | High (seconds-minutes) | Several millimeters | Long-term embryonic development, cell tracking [1] [2] |

| Confocal Raman Spectroscopy | Subcellular (~0.5μm) | Low (hours) | ~100μm | Biomolecular mapping, label-free imaging [3] |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | ~170μm | Low (hours) | Unlimited | Brain development, gross morphology [4] |

| Confocal Microscopy | Subcellular (~0.5μm) | Medium (minutes) | ~200μm | Cellular and subcellular dynamics [5] |

| Static Light Scattering (SLS) | Molecular | Low (minutes) | N/A | Molecular weight, biopolymer characterization [6] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Across Model Organisms

| Organism | Optimal Imaging Window | Key Advantages for Live Imaging | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | 0-24 hours post-fertilization | High optical clarity, vertebrate model | Comprehensive cell lineage tracking, organogenesis [2] |

| Mouse | 6.5-10.0 days post coitum | Mammalian model, genetic tools | Gastrulation, endoderm morphogenesis [5] |

| Chick | 5-20 days of incubation | Accessible embryo, economical model | Brain development, subdivision volume analysis [4] |

| Arabidopsis | Imbibition phases | Plant model, environmental response | Protein localization during hydration [7] |

| Medfly (Ceratitis capitata) | ~60 hours (room temperature) | Insect development, phylogenetic position | Morphogenetic framework establishment [1] |

Advanced Dynamic Imaging Technologies

Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM)

LSFM represents a revolutionary approach for long-term live imaging of embryonic development. This technique illuminates the specimen with a thin sheet of light perpendicular to the detection axis, enabling optical sectioning with minimal phototoxicity and rapid acquisition speeds [2]. The implementation of multi-view imaging in advanced LSFM platforms like SiMView allows simultaneous acquisition of four complementary views of the specimen, providing exceptional physical coverage of large developing organisms [2].

Applied to zebrafish embryogenesis, LSFM enables continuous tracking of tens of thousands of cells during the first 24 hours of development, requiring acquisition speeds of at least 10 million volume elements per second to monitor cellular movements [2]. Similarly, in medfly embryos, LSFM has enabled recording of complete embryonic development over 60 hours at 30-minute intervals, generating 373,995 images while maintaining embryo viability [1].

Confocal Raman Spectroscopic Imaging

This label-free technique utilizes inelastic scattering of laser light to generate biomolecular maps based on intrinsic chemical properties rather than exogenous labels [3]. Confocal Raman spectroscopic imaging (cRSI) provides full spectral coverage enabling visualization of biomolecular distribution in three dimensions with subcellular spatial resolution. Applications in zebrafish embryos include volumetric biomolecular profiling of mycobacterial infections and temporal monitoring of wound response in living embryos [3].

Functional and Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging

While traditionally used in clinical settings, MRI has been adapted for developmental studies, particularly for analyzing brain development in chick embryos [4]. Using a 3.0 T MRI system, researchers have successfully monitored brain subdivision volume changes and structural evolution through diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which measures fractional anisotropy to reflect tissue structural maturation during neural development [4].

Experimental Protocols for Dynamic Live Imaging

Zebrafish Embryo Preparation for LSFM

The exceptional optical clarity of zebrafish embryos makes them ideally suited for long-term live imaging. The following protocol has been optimized for comprehensive developmental analysis:

Sample Mounting: Embed dechorionated embryos in low melting point agarose using the "cobweb holder" approach, which provides mechanical stability while allowing precise positioning within the sample chamber [1] [2].

Multi-view Acquisition: For complete embryonic coverage, implement simultaneous multi-directional imaging along four different axes to overcome opacity of the yolk cell and ensure all structures are visualized [2].

Temporal Parameters: Set acquisition intervals to 30-60 seconds for tracking cell movements during early embryogenesis, adjusting based on specific developmental processes under investigation [2].

Environmental Control: Maintain consistent temperature (23±1°C for medfly; 28.5°C for zebrafish) throughout imaging sessions to ensure normal developmental progression [1] [2].

Mouse Embryo Culture and Imaging

Mouse embryonic development presents unique challenges due to in utero development. The following static culture method enables time-lapse imaging of postimplantation embryos:

Embryo Isolation: Dissect embryos at 6.5-10.0 days post coitum in pre-warmed media, preserving extraembryonic tissues for proper development [5].

Serum-Enriched Culture: Utilize freshly prepared rat serum as culture medium, providing essential nutrients and growth factors normally supplied by the mother [5].

Microscope-Mounted Culture: Adapt static culture methods for implementation directly on microscope stage, enabling continuous imaging while maintaining physiological conditions [5].

Genetic Labeling: Employ transgenic mouse lines expressing fluorescent proteins under tissue-specific promoters (e.g., Flk1 for endothelial cells, c-fms for macrophages) to visualize specific cell lineages [5].

Arabidopsis Embryo Imaging Under Hydration Stress

Investigation of protein dynamics during seed imbibition requires specialized preparation:

Seed Coat Removal: Carefully dissect embryos to expose them directly to solutions of controlled water potential, eliminating the confounding barrier effect of the seed coat [7].

Osmotic Solution Preparation: Prepare solutions with varying water potential using osmolytes such as NaCl, mannitol, or sorbitol in concentration increments (e.g., 200 mM steps from 0 M to 2 M) [7].

Fluorescence Normalization: Account for autofluorescence variations in protein storage vacuoles under different hydration conditions by implementing normalized fluorescence quantification [7].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Networks in Development

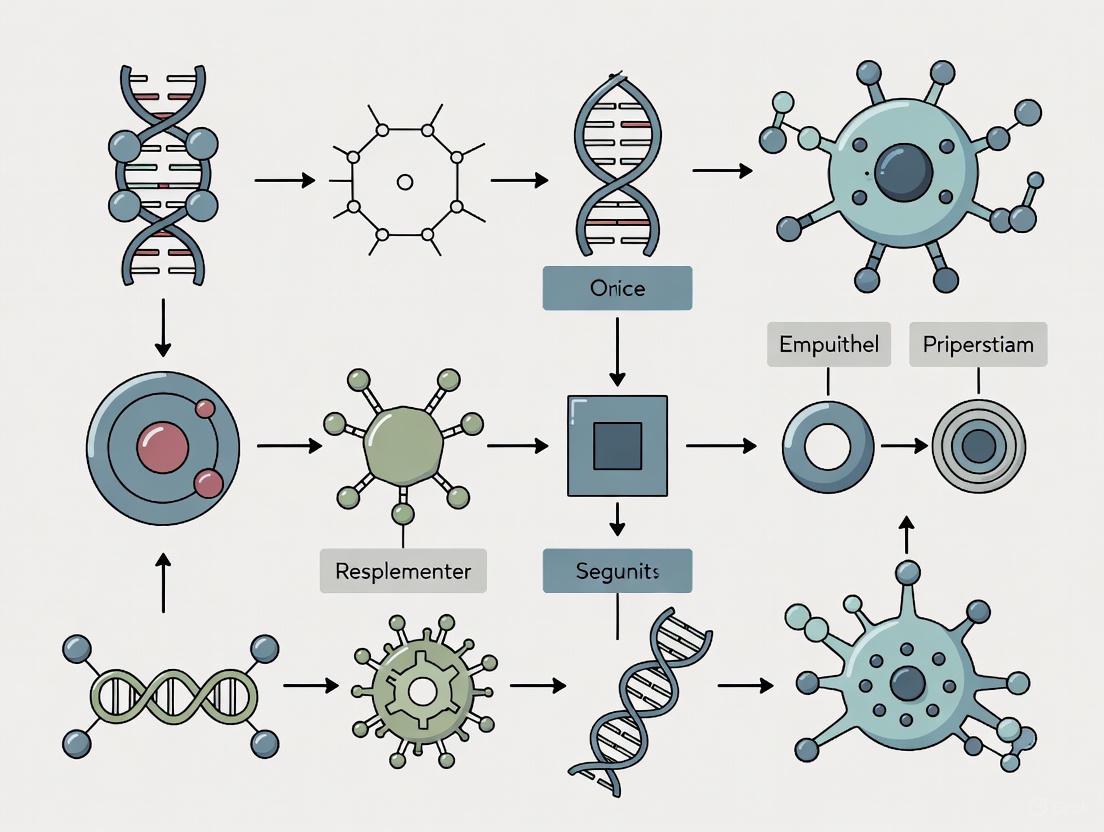

Diagram 1: Gene Regulatory Network Analysis Shift from Static to Dynamic Approaches. The dipteran gap gene system exemplifies how dynamic analysis reveals network criticality and modular behavior not apparent in static structural analysis [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Live Embryo Imaging

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Developmental Live Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application Function | Representative Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Melting Point Agarose | High purity, low gelling temperature | Embryo embedding for stability | Mechanical stabilization in LSFM [1] [2] |

| Transgenic Fluorescent Lines | Tissue-specific promoters | Genetic labeling of cell lineages | Mouse endoderm morphogenesis studies [5] |

| Nuclear-Localized EGFP | Ubiquitin or tissue-specific promoters | Cell tracking and identification | Medfly embryonic development staging [1] |

| Rat Serum | Freshly prepared | Culture medium for postimplantation embryos | Mouse embryo ex vivo development [5] |

| Osmotic Solutions | NaCl, mannitol, sorbitol | Controlled hydration environments | Arabidopsis water potential studies [7] |

| Cobweb Holders | Stainless steel with slotted hole | Precision embryo positioning | Stable mounting for long-term imaging [1] |

The paradigm shift from static to dynamic analysis in developmental biology represents a fundamental transformation in how researchers investigate embryonic development. Static methods continue to provide valuable structural information, but dynamic live imaging approaches have unlocked the temporal dimension of developmental processes, enabling direct observation of cellular behaviors, gene expression dynamics, and morphogenetic events in real-time. The integration of advanced imaging technologies with sophisticated computational analysis and model organisms has established a new framework for understanding the complex dynamics of embryonic development. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to further illuminate the intricate spatial and temporal coordination that transforms a single cell into a complex multicellular organism.

The study of embryonic development relies on advanced live imaging technologies to visualize the complex, dynamic processes of morphogenesis. Selecting the appropriate modality is crucial, as it directly impacts the resolution, depth, and type of quantitative data that can be obtained. This guide objectively compares four principal imaging modalities—optical, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)—in the context of live embryonic research. Each technology offers a unique balance of capabilities and limitations, making it more or less suitable for specific experimental questions, developmental stages, and animal models. We frame this comparison within the broader thesis that no single modality is universally superior; rather, the choice is a strategic trade-off that must align with specific research goals, whether they involve capturing rapid cellular movements, generating high-contrast volumetric data, or conducting longitudinal studies in vivo.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Modalities

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of the four fundamental live imaging modalities used in embryonic research.

Table 1: Key Performance Trade-offs of Embryonic Live Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Penetration Depth | Tissue Contrast | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Imaging (e.g., LSFM, OCT) | ≤ 2 µm (LSFM) [9] to ~15 µm (OCT) [9] | Very High (up to 100 Hz for LSFM) [9] | Limited (≤ 2-3 mm) [10] [11] | Label-free (OCT) or molecular specificity (fluorescence) [9] | Highest resolution; molecular imaging with fluorescence [9] | Limited to early embryos or superficial tissues; scattering in opaque tissues [10] |

| Ultrasound (Micro-ultrasound) | 30 - 50 µm [11] | High (~200 Hz) [11] | ~10-30 mm in mice [12] | Good for blood flow and tissue boundaries [12] | Real-time imaging; excellent for hemodynamics and blood flow [12] [11] | Lower spatial resolution; speckle and shadowing artifacts [10] [13] |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Micro-MRI) | 25 - 100 µm [9] [11] | Low (acquisition time ~2 hours) [9] | High (several cm) [11] | Excellent soft-tissue contrast without ionizing radiation [4] [14] | No skull interference; flexible imaging planes; no radiation [4] | Long scan times; high cost; lower resolution versus micro-CT [11] |

| Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) | < 100 µm to sub-µm [11] [15] | Moderate (minutes per scan) [15] | ~80 mm [11] | Excellent with contrast agents [11] [15] | High-speed, high-resolution 3D imaging; lower cost per scan than MRI [11] | Ionizing radiation; often requires toxic contrast agents for soft tissue [11] |

To aid in modality selection, the following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points based on primary research needs.

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting an embryonic live imaging modality based on primary research requirements.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

In Vivo Chick Embryo Brain Development with 3.0 T MRI

A 2015 study demonstrated the feasibility of serially monitoring brain development in live chick embryos using a clinical 3.0 T MRI system, providing a protocol that avoids embryonic sacrifice and allows for longitudinal tracking [4].

- Animal Model: Ten fertile Hy-line white eggs were incubated. The study successfully monitored seven chick embryo brains serially from day 5 to day 20 of incubation [4].

- Anesthesia and Motion Suppression: To mitigate embryo motion artifacts—a significant challenge after 6 days of incubation—methods such as fast imaging sequences and cooling before imaging were employed [4].

- Image Acquisition: A fast positioning sequence was pre-scanned to obtain sagittal and coronal brain planes corresponding to an established atlas. T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) was used for volume estimation of the whole brain and subdivisions (telencephalon, cerebellum, brainstem, and lateral ventricle). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) was additionally performed to reflect the evolution of neural bundle structures, with Fractional Anisotropy (FA) values serving as a metric for tissue structural anisotropy [4].

- Key Outcomes: The study reported non-linear growth of the whole brain and subdivisions. The FA value within the telencephalon increased non-linearly from 0.026 at day 5 to 0.362 at day 20, indicating progressive neural bundle maturation. All seven scanned eggs hatched successfully, confirming the non-invasive nature of the protocol [4].

Live Avian Embryo Imaging with Contrast-Enhanced Micro-CT

This protocol establishes a method for quantitative 3D imaging of live avian embryonic morphogenesis using micro-CT, overcoming the challenge of soft-tissue contrast with a perfused agent [11] [15].

- Animal Model and Staging: The study analyzed 240 chick embryos across stages from Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 19 (Embryonic Day 3) to HH36 (Embryonic Day 10) [15].

- Contrast Agent Preparation and Perfusion: A Microfil cast was prepared from 80% diluent, 15% microfil dye, and 5% curing agent. The iso-osmotic agent Visipaque (iodixanol) was identified as non-embryotoxic, unlike hyperosmotic alternatives. The agent was perfused directly into the heart using glass capillaries pulled to specific tip sizes (via a NARISHIGE PC-100 puller) appropriate for each embryonic stage. A micro-pump was used to inject the dye at a carefully controlled low flow rate (2.8 to 6.8 µL/min) to prevent vascular rupture [11] [15].

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Embryos were scanned post-perfusion. The protocol confirmed that 3D volumetric quantification of contrast-enhanced tissues in live embryos was statistically identical to measurements from fixed specimens, validating its accuracy for morphometric studies [11].

Multimodal Optical Imaging with OCT and 2P-LSFM

A 2025 study presented a novel multimodal system that combines the structural capabilities of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) with the molecular specificity of Two-Photon Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (2P-LSFM) for high-resolution embryonic imaging [9].

- System Integration: The system features optically co-aligned OCT and LSFM beams, scanned through the same galvanometer-mounted mirrors and illumination objective. This co-alignment simplifies image registration and enables simultaneous data acquisition [9].

- Performance Specifications: The swept-source OCT subsystem provides a lateral resolution of ~15 µm and an axial resolution of ~7 µm. The 2P-LSFM subsystem offers a superior lateral resolution of ~2 µm with a light sheet thickness of ~10 µm. The use of two-photon excitation enhances penetration depth up to ~1 mm in scattering embryonic tissues compared to one-photon LSFM [9].

- Experimental Workflow: The sample is mounted on a motorized translation stage, which steps the embryo through the co-planar OCT and LSFM imaging planes. At each step, both OCT and LSFM images are acquired concurrently. This setup overcomes traditional LSFM limitations of short working distance and limited field of view by using a telecentric scan lens as the illumination objective [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful live embryo imaging often depends on specialized reagents and materials. The table below details essential items from the featured experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Embryonic Live Imaging

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Visipaque (Iodixanol) | Iso-osmotic, non-embryotoxic blood pool contrast agent for micro-CT [11]. | Perfused into chick embryo vasculature to provide high-contrast imaging of cardiovascular structures without inducing malformations [11]. |

| Microfil Cast | Polymerizing contrast agent for ex vivo vascular casting and micro-CT imaging [15]. | Injected into chick embryo hearts to create a detailed 3D cast of the vasculature for high-resolution morphological analysis [15]. |

| Glass Capillaries (Pulled) | Fine-tipped needles for micro-injection into delicate embryonic structures [15]. | Used with a micro-pump to perfuse contrast agent into the ventricles of chick embryo hearts at different developmental stages [15]. |

| Isoflurane | Inhalable anesthetic for immobilizing small animals during imaging sessions [12]. | Used at ~2% in oxygen/air to anesthetize mice during micro-ultrasound procedures to minimize motion artifacts [12]. |

| Swept-Source Laser | High-speed laser for Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [9]. | Served as the OCT light source (1051 nm central wavelength) in a multimodal OCT-LSFM system for rapid, label-free structural imaging [9]. |

| Femtosecond Excitation Laser | Laser for non-linear microscopy, such as two-photon excitation [9]. | Generated 920 nm femtosecond pulses for 2P-LSFM to enable deeper penetration and reduced photo-toxicity in fluorescently tagged mouse embryos [9]. |

Integrated Imaging & Future Directions

The trend in embryonic imaging is moving toward multimodal integration, where the complementary strengths of different modalities are combined to gain a more comprehensive understanding of development. As exemplified by the combined OCT and 2P-LSFM system, researchers can now simultaneously acquire coregistered structural and molecular information from the same live embryo [9]. This synergy allows for the correlation of gross morphological changes with specific cellular and molecular events.

Furthermore, technological improvements are continuously pushing the boundaries of each modality. In MRI, the transition from 1.5-T to 3-T magnetic fields provides a higher signal-to-noise ratio for improved image quality, while advanced motion-correction software is overcoming the challenge of fetal movement artifacts [14]. In optical imaging, techniques like light-sheet microscopy offer high-speed volumetric imaging with minimal photo-damage, making long-term observation of rapid developmental processes feasible [16] [9]. The future of the field lies in both the refinement of these individual technologies and the intelligent design of integrated platforms that provide a unified, quantitative view of embryonic morphogenesis.

Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins and Vital Reporters as Contrast Agents

The use of genetically encoded fluorescent proteins has revolutionized the fields of cell and developmental biology and redefined our understanding of the dynamic morphogenetic processes that shape the embryo [17]. These proteins function as vital reporters to label tissues, cells, cellular organelles, or proteins of interest, providing contrasting agents that enable the acquisition of high-resolution quantitative image data [17]. For researchers studying embryo development, these tools have transformed static snapshots of fixed specimens into dynamic, real-time visualizations of living processes. The advent of more accessible and sophisticated imaging technologies, coupled with a growing palette of fluorescent proteins with diverse spectral characteristics, now allows scientists to probe dynamic processes in situ in living embryos, moving analyses from sequentially staged dead embryos into a dynamic context that reveals the cell behaviors underlying normal embryonic development [17].

Comparative Analysis of Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins

Performance Characteristics and Key Applications

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics and applications of major genetically encoded fluorescent proteins based on current literature and experimental data.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation/Emission Max (nm) | Brightness (Relative to EGFP) | Photostability | Maturation Time (min) | Primary Applications in Live Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP (Enhanced GFP) | 488/509 | 1.0 (reference) | Moderate | ~30 | General cell labeling, gene expression reporting, protein fusion [17] |

| Emerald GFP | 487/509 | ~1.5-2.0x EGFP | High | ~30 | Long-term time-lapse imaging, low-expression systems [17] |

| mWasabi | 493/509 | ~1.5x EGFP | High | ~15 | Rapid dynamics, short-term high-resolution imaging [17] |

| Azami Green (AG) | 492/505 | Comparable to EGFP | High | ~15 (at 37°C) | Mammalian cell culture, embryo imaging [17] |

| Venus | 515/528 | ~1.5x EGFP | Moderate | ~15 | Protein interactions, secretory organelles [17] |

| Cerulean | 433/475 | ~0.5x EGFP | Low | ~30 | FRET donor with Venus/YFP acceptors [17] |

| mCherry | 587/610 | ~0.5x EGFP | High | ~45 | Multiplex imaging, lineage tracing [17] |

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Performance data for fluorescent proteins are typically established through standardized photophysical characterization including measurements of quantum yield (efficiency of photon emission), extinction coefficient (light absorption capacity), and photostability (resistance to photobleaching) [17]. For instance, the development of EGFP through point mutation (S65T) significantly improved its fluorescence intensity and photostability compared to wild-type GFP, establishing it as the green fluorescent protein of choice for most applications in mice and other model organisms [17].

Experimental protocols for determining these characteristics generally involve:

- Protein purification and spectroscopy: Recombinant FPs are expressed and purified to measure absorption and emission spectra, quantum yield, and extinction coefficients [17].

- Cellular expression assays: Plasmids encoding FPs are transfected into mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293) to assess brightness, maturation time, and photostability in biological environments [17].

- Targeted expression in model systems: FP genes are introduced into embryos via transgenesis or other methods to evaluate performance in developmental contexts [17].

Advanced Biosensor Design Based on Fluorescent Proteins

Molecular Architecture of Activity Reporters

Beyond simple labeling, fluorescent proteins form the core of sophisticated biosensors that report specific biochemical activities in live cells and embryos. These include FRET-based reporters and single-fluorophore translocation reporters [18].

Table 2: Genetically Encoded Biosensors Utilizing Fluorescent Proteins

| Biosensor Type | Molecular Design | Detection Mechanism | Key Advantages | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRET-Based Reporters | Donor and acceptor FPs linked by a sensor domain | Phosphorylation-induced conformational change alters FRET efficiency | Ratiometric measurement, reduced artifacts | Kinase activity, calcium signaling [18] |

| Single-Fluorophore Translocation Reporters (KTR) | Single FP fused to a kinase-specific substrate | Phosphorylation regulates nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling | Enables multiplex imaging, simple acquisition | ERK, JNK, PKA signaling pathways [18] |

| Degradation-Based Reporters | FP fused to a degradation motif (degron) | Activity-dependent protein stabilization/destruction | Direct monitoring of proteostasis | β-TrCP activity, cell cycle regulation [19] |

The β-TrCP activity reporter exemplifies the degradation-based design strategy. This biosensor was constructed by fusing the fluorescent protein mVenus to specific fragments of human CDC25B containing a non-canonical β-TrCP degron motif (DDGFVD) [19]. Validation experiments demonstrated that knocking down β-TrCP1,2 using siRNA caused a significant increase in reporter fluorescence signal, confirming specific reporting of β-TrCP-mediated degradation activity [19].

Experimental Workflow for Biosensor Validation

A standardized protocol for biosensor development and validation includes:

- Molecular cloning: Construction of biosensor plasmids using appropriate backbone vectors (e.g., lentiviral vectors for stable expression) with constitutive promoters (e.g., EF1α) [19].

- Functional validation: Transfection into relevant cell lines followed by pharmacological or genetic perturbation of the target activity [19].

- Quantitative live-cell imaging: Time-lapse microscopy with appropriate environmental control (temperature, CO₂) to monitor biosensor dynamics [19].

- Image analysis: Computational quantification of fluorescence intensity, localization, or FRET ratios using software such as ImageJ, MetaMorph, or Imaris [17].

The following diagram illustrates the molecular design and mechanism of the β-TrCP degradation-based biosensor:

Diagram 1: β-TrCP Biosensor Mechanism

Application in Live Embryo Imaging: Technical Considerations

Methodological Advances in Embryo Imaging

The application of genetically encoded reporters in embryo imaging requires specialized methodologies to maintain viability while achieving sufficient resolution. Recent innovations include:

Electroporation-based labeling: A novel method for introducing mRNA encoding histone H2B-fluorescent protein fusions into blastocyst-stage human embryos addresses limitations of microinjection, which is restricted to early stages (zygote or two-cell) due to the need for individual cell injection [20]. This technique, combined with light-sheet microscopy, enables high-resolution imaging every 15 minutes for up to 48 hours while maintaining embryo viability [20].

Computational analysis pipelines: Once image data is collected, computational methods quantify and segment data to generate high-resolution information on cellular organelles, serving as descriptors of cell position (nuclei) and morphology (plasma membrane) [17]. Specialized software includes commercially available packages (Amira, Imaris, MetaMorph, Volocity) and open-source alternatives (ImageJ) with specific tools for developmental imaging (3D-DIAS for cell identification and tracking) [17].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a complete live embryo imaging pipeline:

Diagram 2: Live Embryo Imaging Workflow

Experimental Outcomes in Embryo Research

Implementation of these methodologies has yielded critical insights into developmental processes:

- Chromosomal instability tracking: Live imaging of human embryos revealed higher frequency of chromosome misalignment compared to mouse embryos (approximately 8% vs 4%), with resulting micronuclei typically tolerated in trophectoderm cells [20].

- Cell fate determination: Tracking individual cells throughout development has demonstrated that some abnormalities are confined to cells destined to become trophectoderm, which continue to proliferate and contribute to blastocyst formation despite mis-segregated chromosomes [20].

- Lineage specification: Fluorescent reporters have enabled precise mapping of division orientation, revealing that trophectoderm nuclei align parallel to the embryo surface, ensuring subsequent divisions are perpendicular to maintain epithelial stability [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Live Embryo Imaging with Fluorescent Proteins

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Embryo Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Vectors | EGFP, mCherry, H2B-GFP fusions | Cell labeling, lineage tracing, protein localization | Promoter selection (constitutive vs. tissue-specific), expression level optimization [17] [20] |

| Gene Delivery Tools | Electroporation systems, Microinjection | Introduction of nucleic acids encoding FPs | Stage-dependent efficiency; electroporation effective at blastocyst stage [20] |

| Live-Cell Imaging Media | Climate-controlled chamber systems | Maintenance of embryo viability during imaging | Stable pH, temperature, osmolarity over extended periods [17] |

| Microscopy Systems | Light-sheet microscopy, Confocal LSM | 3D+time acquisition with minimal phototoxicity | Balance between resolution, imaging depth, and photodamage [17] [20] |

| Pharmacological Modulators | MLN-4924 (SCF inhibitor), Kinase inhibitors | Pathway perturbation for functional studies | Dose optimization to avoid pleiotropic effects [19] |

| Image Analysis Software | Imaris, ImageJ, 3D-DIAS | Cell tracking, fluorescence quantification | Automated segmentation accuracy for high-density embryo data [17] |

Genetically encoded fluorescent proteins and vital reporters have fundamentally transformed live imaging in embryo development research, evolving from simple morphological markers to sophisticated biosensors of specific biochemical activities. The continuous expansion of the fluorescent protein palette, coupled with advances in imaging modalities and computational analysis, provides an increasingly powerful toolkit for deconstructing the dynamic processes that shape embryonic development. As these technologies continue to mature, they promise to yield ever deeper insights into the fundamental principles of development while offering clinical applications in reproductive medicine through improved embryo assessment capabilities [20]. The optimal selection of fluorescent reporters—balanced for brightness, photostability, and developmental neutrality—remains crucial for designing experiments that accurately capture the intricate dynamics of embryogenesis without perturbing the delicate processes under investigation.

Live imaging has revolutionized developmental biology by transforming our understanding of how complex organisms form. This guide compares the performance of modern live imaging techniques that enable researchers to visualize and quantify key biological processes from embryonic lineage commitment to organ formation. Unlike static snapshots, technologies such as light-sheet fluorescence microscopy, confocal time-lapse imaging, and Brillouin microscopy provide dynamic, high-resolution data on cellular behaviors, mechanical properties, and tissue-scale transformations in real-time [21] [22] [23]. We objectively evaluate these techniques based on their spatiotemporal resolution, phototoxicity, applicability to different model systems, and the unique biological insights they generate, providing experimental data to guide method selection for specific research goals in basic science and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Live Imaging Techniques

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different live imaging modalities used in contemporary developmental biology research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Live Imaging Techniques

| Imaging Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution (Volumetric) | Key Advantage | Primary Application in Guide | Phototoxicity Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light-Sheet Microscopy | ~5 μm (for single nuclei) [24] | 10-minute intervals for 12+ hours [24] | Minimal phototoxicity, long-term imaging | Tracking mitotic errors and cell fate in human and mouse embryos [21] | Low; enables 46+ hour imaging of human embryos [21] |

| Confocal Time-Lapse | Subcellular (cell area, division) [23] | 24-hour intervals for 11 days [23] | Cellular resolution growth quantification | Stamen organogenesis in Arabidopsis [23] | Moderate; limits observation depth in mouse embryos [24] |

| Line-Scan Brillouin Microscopy | 1.5 μm [22] | ~2 minutes for 83×183×43 μm volume [22] | Label-free mechanical property assessment | Tissue mechanics during Drosophila gastrulation [22] | Low; ~20 mW illumination, no observed photodamage [22] |

| Biaxial Light-Sheet (diSPIM) | <5 μm [24] | <10-minute intervals for 12 hours [24] | Dual-axis improved image quality | Single-cell tracking in E5.5 mouse embryos [24] | Optimized via scan speed adjustment [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Live Imaging Applications

Protocol: Live Imaging Chromosome Segregation in Human Blastocysts

This protocol outlines the methodology for visualizing de novo mitotic errors in late-stage preimplantation human embryos, a technique that has revealed chromosome segregation defects immediately before implantation [21].

- Nuclear Labeling: Electroporate blastocyst-stage human embryos (cryopreserved at 5 days post-fertilization) with 700-800 ng/μL H2B-mCherry mRNA. This approach achieves approximately 41% efficiency in human embryos without significant impact on cell number or lineage specification compared to controls [21].

- Microscopy Setup: Utilize a light-sheet fluorescence microscope (LS2 model) with dual illumination and double detection. This configuration minimizes light exposure and enables long-term imaging (up to 46 hours) that would be prohibitive with confocal microscopy due to phototoxicity [21].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire 3D image stacks over time to track mitotic phases (prophase, metaphase, anaphase, telophase) and identify segregation errors including multipolar spindle formation, lagging chromosomes, misalignment, and mitotic slippage.

- Data Analysis: Employ a semi-automated segmentation pipeline using a customized deep learning model optimized for variability in embryo size, shape, and signal to trace individual nuclei and their positions [21].

Protocol: Quantifying Mechanical Properties During Embryogenesis

This protocol describes line-scan Brillouin microscopy for assessing viscoelastic properties in developing embryos, enabling correlation of mechanical changes with morphogenetic events [22].

- System Configuration: Implement a line-scan Brillouin microscope (LSBM) in either orthogonal-line (O-LSBM) or epi-line (E-LSBM) configuration. Use a narrowband 780 nm diode laser to reduce phototoxic effects compared to commonly used 532 nm lasers [22].

- Sample Preparation: Mount embryos (Drosophila, ascidian, or mouse) in microdrop cultures using a custom miniaturized incubation chamber with full environmental (temperature, CO₂, O₂) control [22].

- Data Acquisition: Perform simultaneous Brillouin shift mapping and fluorescence SPIM imaging. For Drosophila gastrulation, image with a field of view of ~83 × 183 × 43 μm with z-increment of 2.5 μm and volume time resolution of ~2 minutes [22].

- Spectral Processing: Analyze multiplexed spectra using a GPU-enhanced numerical fitting routine for real-time spectral data analysis, providing >1,000-fold enhancement in processing time compared to CPU-based pipelines [22].

Protocol: Computational Integration of Tissue Morphogenesis Data

This protocol outlines a computational framework for analyzing tissue motion and deformation from multiple live imaging datasets, addressing variability in mammalian embryo development [25].

- Image Preprocessing: Extract underlying tissue motion using non-rigid registration algorithms on 3D+t live images of developing organs (e.g., mouse heart from cardiac crescent to linear heart tube stages) [25].

- Data Synchronization: Temporally map individual 3D live images to a pseudodynamic Atlas of heart morphogenesis using a staging system that registers each specimen to a common timeline and geometric framework [25].

- Motion Integration: Project individual motion profiles onto the unified spatiotemporal framework to reconstruct cumulative tissue deformation and generate an in-silico fate map of cardiomyocyte trajectories [25].

- Quantitative Analysis: Define stepwise tissue deformation and cumulative deformation metrics to quantify growth patterns and anisotropy across multiple integrated specimens [25].

Visualizing Key Biological Pathways and Workflows

Hippo Signaling Pathway in Mouse Embryo Lineage Segregation

The following diagram illustrates the Hippo signaling pathway that governs the segregation of the trophectoderm (TE) from the inner cell mass (ICM) in the mouse blastocyst, a key process in early lineage commitment [26].

Diagram Title: Hippo Signaling in Mouse Embryo Lineage Segregation

Light-Sheet Microscopy Workflow for Embryo Live Imaging

This workflow diagram outlines the optimized process for long-term live imaging of preimplantation embryos using light-sheet microscopy, highlighting key methodological improvements that enable reduced phototoxicity and high-resolution tracking [21] [24].

Diagram Title: Light-Sheet Microscopy Workflow for Embryo Imaging

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Embryo Live Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| H2B-mCherry mRNA | Nuclear DNA labeling via electroporation | Tracking chromosome segregation in human blastocysts [21] |

| Cdx2-eGFP mouse line | Reporter for Hippo signaling activity and TE lineage | Quantitative readout of lineage specification in mouse embryos [26] |

| R26-H2B-EGFP mouse line | Ubiquitous nuclear labeling | Single-cell tracking in E5.5 mouse embryos [24] |

| SPY650-DNA dye | Alternative DNA staining | Limited labeling of trophectoderm nuclei in blastocysts [21] |

| Collagen I gel | 3D embryo embedding for stable imaging | Maintaining normal morphology in E5.5 mouse embryos [24] |

| Line-scan Brillouin microscope | Label-free mechanical property assessment | Measuring tissue stiffness during Drosophila gastrulation [22] |

| Custom incubation chamber | Environmental control (temperature, CO₂, O₂) | Long-term culture during live imaging [22] |

From Lab to Clinic: Practical Applications of Specific Live Imaging Modalities

Light-Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM) has emerged as a transformative imaging technique that addresses critical limitations of conventional fluorescence microscopy in live embryo research. Unlike traditional point-scanning methods, LSFM illuminates specimens with a thin sheet of light, exciting fluorophores only within the focal plane of the detection objective [27]. This fundamental difference in optical configuration provides exceptional advantages for imaging sensitive biological samples over extended periods, making it particularly valuable for developmental biology studies requiring long-term observation of embryonic processes with minimal photodamage [17] [28]. As live imaging becomes increasingly crucial for understanding the dynamic morphogenetic events that shape developing organisms, LSFM offers researchers the unique capability to capture rapid volumetric changes at high spatial and temporal resolution while maintaining sample viability [29]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of LSFM performance against alternative imaging modalities and details experimental protocols for implementing this technology in embryo development research.

How LSFM Works: Optical Principles and Configurations

Fundamental Operating Principle

The core innovation of LSFM lies in its orthogonal arrangement of illumination and detection pathways. In a typical LSFM setup, a thin laser sheet (typically 1-5 µm thick) illuminates only a single plane within the specimen at any given time, while a detection objective positioned perpendicular to the light sheet collects the emitted fluorescence [27] [30]. This sectioning approach eliminates out-of-focus excitation, dramatically reducing photobleaching and phototoxicity compared to widefield or confocal microscopy. The entire illuminated plane is captured simultaneously using a high-speed camera, enabling rapid volumetric imaging by scanning the light sheet through the sample or translating the sample through the light sheet [28].

Advanced LSFM Configurations

Several advanced LSFM configurations have been developed to address specific imaging challenges:

Dual-view Inverted Selective Plane Illumination Microscopy (diSPIM) combines two perpendicular objectives for alternating excitation and detection, significantly improving resolution isotropy. By computationally fusing the resulting volumetric views, diSPIM achieves isotropic resolution of approximately 330 nm, more than quadrupling axial resolution compared to single-view systems [28].

Multiview LSFM rotates the specimen to acquire images from multiple angles, which are computationally combined to reconstruct the entire specimen with more isotropic resolution. This approach is particularly valuable for imaging large, optically heterogeneous samples [29].

Confocal line-scanning LSFM (LS-LSFM) incorporates a rolling shutter mechanism synchronized with the scanning excitation beam to reduce scattered light contribution, improving image quality in scattering specimens [31].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental components and light path of a basic LSFM system:

Performance Comparison: LSFM Versus Alternative Imaging Modalities

Quantitative Comparison of Key Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of LSFM compared to other common live imaging techniques used in developmental biology:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Live Imaging Modalities for Embryo Research

| Method | Resolution | Imaging Depth | Speed | Photobleaching/Phototoxicity | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wide-field | Good | Low (microns) | Fast | Low | Basic fluorescence imaging of thin samples |

| Confocal (LSCM)* | Good | Moderate (10s of microns) | Slower | Moderate/High | Standard fixed and live cell imaging |

| Multi-photon | Good | Good (100s of microns) | Slower | Moderate/High | Deep tissue imaging, intravital studies |

| Light Sheet (LSFM)* | Good | Good (100s of microns) | Fast | Low | Long-term live imaging of large volumes |

| Super-resolution-SIM | Very Good | Low (microns) | Slow | High | Subcellular structure analysis |

Data compiled from published sources [30]

Technical Advantages for Embryo Imaging

LSFM provides distinct technical advantages that make it particularly suitable for embryonic development studies:

Superior Imaging Speed: LSFM can acquire full volumetric data at rates 10-1,000× faster than other 4D microscopy techniques [28]. This enables capture of rapid developmental processes, such as zebrafish heart contraction, which requires exposure times of less than 5 ms [31].

Enhanced Viability for Long-term Imaging: The significantly reduced phototoxicity of LSFM enables continuous observation of embryonic development over timescales of days, as demonstrated in studies of Parhyale hawaiensis limb formation spanning 3-8 days of embryogenesis [29].

Improved Depth Penetration: In conventional confocal microscopy, excitation illumination must pass through the entire sample to the focal plane, with emitted light returning through the same path. This compounded scattering limits sensitivity and resolution in thick samples. LSFM's separate illumination and detection paths reduce light scattering and improve imaging in thick specimens [30].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing LSFM for Embryo Imaging

Sample Preparation and Mounting

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful LSFM imaging of developing embryos:

Mouse Embryo Preparation: For imaging early mouse embryogenesis (E5.5), embed embryos in a 3-mm cubic structure made of polycarbonate filled with collagen I gel. Secure the cube to the bottom of the imaging cuvette using the surface tension of 150-200 μl of medium [24].

Drosophila Embryo Mounting: For fruit fly embryogenesis studies, combine LSFM with image processing to obtain outlines of cells and cell nuclei, as well as the geometry of the whole embryo tissue by image segmentation [32].

Parhyale hawaiensis Preparation: For crustacean limb development studies, use transgenic embryos with fluorescently labeled nuclei imaged for several consecutive days using LSFM. The transparent eggshell and low autofluorescence of these embryos make them ideal for long-term imaging [29].

Multi-view Image Acquisition and Processing

Multiview acquisition significantly enhances image quality by providing more isotropic resolution:

Data Acquisition: Image samples from multiple angular viewpoints (e.g., from day 3 to day 8 of embryogenesis for Parhyale limb formation). Rotate the specimen to acquire complementary views that will be computationally combined [29].

Image Registration and Fusion: Use computational methods to register acquired views and fuse raw z-stacks into a single output volume. Software solutions include open-source packages like the Massive Multi-view Tracker (MaMuT) for visualization, annotation, and lineage reconstruction [29].

Joint Deconvolution: Implement joint deconvolution algorithms that make optimal use of information from multiple views. The modified Richardson-Lucy algorithm can provide an estimate consistent with complementary measurements, effectively preserving the best resolution inherent in each view [28].

The workflow below illustrates the multi-view acquisition and processing pipeline:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for LSFM Experiments

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LSFM Embryo Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins (FPs) | Label specific tissues, cells, or subcellular structures | EGFP, Venus, Citrine for labeling mouse embryo nuclei [17] [24] |

| Low-Melting Point Agarose | Sample embedding and stabilization | Immobilizing embryos for long-term imaging without developmental disruption |

| Collagen I Gel | 3D matrix for embryo support | Embedding mouse embryos for E5.5 development studies [24] |

| Environmental Control Systems | Maintain temperature, CO₂, O₂ during imaging | Custom incubation chambers for mouse embryo culture during imaging [22] [24] |

| Cell Lineage Tracking Software | Segment and track cells through development | Massive Multi-view Tracker (MaMuT) for reconstructing cell lineages [29] |

Advanced Applications: Integration with Complementary Technologies

Deep Learning-Enhanced LSFM

Recent advances combine LSFM with deep learning to further improve imaging capabilities:

UI-Trans Network: A convolutional neural network (CNN)-transformer hybrid architecture has been developed to mitigate complex noise-scattering-coupled degradation in LSFM images. This approach achieves 3-5 fold signal-to-noise ratio improvement and approximately 1.8 times contrast improvement in ex vivo zebrafish heart imaging [31].

Reduced Light Exposure: Deep learning-enhanced LSFM enables high-quality imaging with less than 0.03% light exposure and 3.3% acquisition time compared to standard acquisition methods, dramatically reducing potential phototoxicity [31].

Integration with Biomechanical Imaging

LSFM has been successfully combined with Brillouin microscopy to simultaneously capture structural and mechanical information:

Line-Scan Brillouin Microscopy (LSBM): This integrated approach enables visualization of mechanical properties during Drosophila gastrulation with 100-fold improvement in imaging speed compared to previous Brillouin microscopy implementations [22].

Correlated Mechanical and Fluorescence Imaging: Concurrent SPIM fluorescence imaging enables 3D fluorescence-guided Brillouin image analysis, correlating mechanical properties with specific tissue regions and molecular constituents [22].

Comparative Experimental Data: LSFM Performance in Published Studies

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of LSFM in Developmental Biology Applications

| Application | Sample Type | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Imaging Duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish Heart Development | Live zebrafish embryo | Subcellular | Sufficient for heartbeat | Long-term developmental stages | [31] |

| Mouse Embryo Gastrulation | E5.5 mouse embryo | Single-cell (∼5 μm) | 10 min/frame | 12 hours continuous | [24] |

| Drosophila Gastrulation | Fruit fly embryo | Cellular | ∼2 min/volume | Complete VFF and PMI processes | [22] |

| Arthropod Limb Formation | Parhyale hawaiensis | Single-cell | Not specified | 3-8 days of embryogenesis | [29] |

| Microtubule Dynamics | Live cultured cells | ∼330 nm isotropic | 200 images/s | Hundreds of volumes | [28] |

Light-Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy represents a significant advancement in live imaging technology, particularly for developmental biology applications requiring long-term, high-resolution observation of rapid volumetric dynamics. While point-scanning techniques like confocal and multiphoton microscopy remain valuable for specific applications requiring higher resolution in scattering tissues, LSFM provides unparalleled capabilities for imaging large specimens with minimal photodamage. The integration of LSFM with complementary technologies including multiview acquisition, advanced computational processing, deep learning enhancement, and biomechanical imaging continues to expand its applications in developmental biology and drug discovery research. As the technology becomes more accessible and user-friendly, LSFM is poised to become an increasingly central tool for researchers investigating the dynamic processes that shape embryonic development.

Live imaging of embryo development provides unparalleled insight into the dynamic cellular and subcellular processes that underlie morphogenesis. Among the various technologies available, laser-scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) represents a cornerstone technique for high-resolution tracking in three-dimensional space over time. This guide objectively compares LSCM's performance against emerging alternatives such as super-resolution microscopy and light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM), with a specific focus on applications in embryo development research. The global confocal microscope market, estimated at $1.5 billion in 2025 with a 7% compound annual growth rate, reflects its significant role in life sciences research and clinical diagnostics [33].

Understanding the mechanical properties of cells and tissues is fundamental to developmental biology, as these physical parameters play integral roles in determining biological function [34]. While confocal microscopy excels at visualizing molecular components via fluorescence, assessing mechanical properties with similar spatiotemporal resolution has remained challenging. Recent advances in imaging technologies now enable researchers to correlate mechanical property measurements with detailed morphological tracking, opening new avenues for understanding embryogenesis.

Technical Comparison of Imaging Modalities

Fundamental Principles and Key Differentiators

Laser-Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM) operates on the principle of spatial filtering to eliminate out-of-focus light. A laser beam is focused to a discrete point within the sample, and emitted fluorescence passes through a pinhole aperture positioned in a plane conjugate to the focal point (hence "confocal"). This optical arrangement rejects light from above and below the focal plane, resulting in significantly improved image contrast and effective optical sectioning capability compared to widefield fluorescence microscopy. The point-scanning approach allows for high-resolution imaging but inherently limits acquisition speed, particularly for large volumetric samples [35].

Super-resolution Microscopy encompasses several techniques that overcome the diffraction limit of light (~200 nm for conventional microscopy). Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) uses grid projections at different angles and orientations to encode high-frequency information into the observable spatial frequencies, effectively doubling the resolution through computational reconstruction. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy employs a donut-shaped depletion beam that deactivates fluorophores at the periphery of the excitation focus, effectively reducing the point spread function and achieving resolutions down to 20-70 nm [35].

Light-Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM) utilizes a separate objective to illuminate the sample with a thin sheet of light, exciting only fluorophores within the focal plane of the detection objective. This orthogonal arrangement minimizes photobleaching and phototoxicity by limiting light exposure to the imaged plane rather than the entire sample volume. The digital scanned laser light sheet microscopy (DSLM) variant rapidly scans a Gaussian laser beam to generate a dynamic light sheet, further improving optical sectioning capability [36].

Performance Metrics and Experimental Considerations

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Live Imaging Techniques for Embryo Development

| Performance Metric | Laser-Scanning Confocal | Super-Resolution (STED/SIM) | Light-Sheet (LSFM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~240 nm lateral, ~600 nm axial | ~20-100 nm (below diffraction limit) | ~300-400 nm lateral, ~1 µm axial |

| Temporal Resolution | Seconds to minutes for 3D volumes | Minutes to hours for 3D volumes | Sub-second to seconds for 3D volumes |

| Phototoxicity Impact | Moderate to high (point scanning) | High (high illumination doses) | Low (selective plane illumination) |

| Sample Penetration Depth | Moderate (limited by scattering) | Limited (especially in thick samples) | Excellent (good depth penetration) |

| Live Cell Compatibility | Good, with limitations due to phototoxicity | Limited for extended live imaging | Excellent for long-term imaging |

| Ease of Sample Preparation | Standard | Often requires special buffers/mounting | Can require specialized mounting (e.g., cobweb holder) |

| Data Volume | Moderate | High (especially for large volumes) | Very high (rapid 3D acquisition) |

Table 2: Application-Specific Suitability for Embryo Development Research

| Research Application | Laser-Scanning Confocal | Super-Resolution | Light-Sheet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term morphogenesis tracking | Limited by phototoxicity | Generally unsuitable | Excellent (e.g., 60+ hours of medfly development) |

| Subcellular protein localization | Good | Excellent | Moderate |

| Rapid dynamic processes | Moderate | Limited | Excellent |

| Large sample imaging | Slow | Very slow | Fast |

| Mechanical properties assessment | Limited | Limited | Emerging (e.g., Brillouin LSFM) |

| High-throughput screening | Moderate | Low | High |

The data in Table 1 and Table 2 reveal a clear trade-off between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and phototoxicity that must be balanced according to specific experimental requirements. While super-resolution techniques provide unparalleled spatial resolution, their extended acquisition times and high illumination dosages often preclude long-term live imaging of delicate embryonic samples [35]. Conversely, LSFM sacrifices some spatial resolution for dramatically reduced phototoxicity, enabling time-lapse observations spanning entire embryogenesis periods—in one study, covering approximately 97% of Mediterranean fruit fly embryonic development (60 hours at 30-minute intervals) [36].

Experimental Applications in Embryo Development

Case Study: Drosophila Gastrulation

The mechanical dynamics during Drosophila melanogaster gastrulation have been successfully captured using line-scanning Brillouin microscopy (LSBM), a specialized variant of light-sheet technology. During ventral furrow formation (VFF) and posterior midgut invagination (PMI)—two fast tissue-folding events occurring within approximately 15 minutes—researchers observed transient increases in Brillouin shift (indicating changes in mechanical properties) within the mesodermal cells engaged in tissue folding. This mechanical tightening occurred independently of the geometry of the contractile domain (rectangular in VFF, circular in PMI), suggesting a common biophysical mechanism underlying different folding modalities [34].

This study exemplifies the power of advanced imaging to correlate mechanical properties with morphological changes. The line-scanning approach enabled volumetric imaging with a temporal resolution of approximately 2 minutes per volume, representing an approximate 100-fold improvement compared to previous spontaneous Brillouin scattering microscopes at more than 10-fold lower illumination energy per pixel. Critically, no photodamage or phototoxicity was observed at illumination powers below ~20 mW, highlighting the suitability of this method for imaging highly dynamic and photosensitive developmental processes [34].

Comparative Performance in Long-Term Development Studies

In a comprehensive study of Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) embryogenesis, LSFM demonstrated exceptional capability for long-term observation without compromising developmental outcome. Researchers acquired nine datasets totaling 484.5 hours of recording time (373,995 images, 256 GB), with six datasets capturing embryonic development in toto at 30-minute intervals along four directions in three spatial dimensions. Remarkably, all imaged embryos hatched morphologically intact, and all but one developed into healthy adults—a testament to the minimal phototoxicity of light-sheet illumination [36].

This study implemented a digital scanned laser light sheet microscope (DSLM) with a 488 nm diode laser for illumination and either 10×/0.3 NA or 20×/0.5 NA water-dipping objectives for detection. The system included a precision rotation stage for multi-view acquisition, significantly improving image quality and resolution through computational fusion of complementary viewpoints. The resulting datasets enabled the creation of a morphogenesis-based two-level staging system for medfly development, providing a framework for future comparative studies in insect embryogenesis [36].

Detailed Methodologies

Laser-Scanning Confocal Protocol for Live Embryo Imaging

Sample Preparation:

- Embryo Collection: Collect Drosophila embryos within a defined time window (typically 0-30 minutes after laying) using a small paint brush to transfer them to a 100 µm cell strainer.

- Dechorionation: Treat embryos with a 1:9 dilution of sodium hypochlorite solution (approximately 1% final concentration) for 90 seconds to remove the chorion, followed by two 60-second washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Mounting: Embed embryos in appropriate agarose or mounting medium on glass-bottom dishes or chambered coverslips. For longer observations, maintain temperature at 25°C using a stage-top incubator.

Image Acquisition:

- System Setup: Configure laser power, detector gain, and pinhole size (typically 1 Airy unit) to optimize signal-to-noise ratio while minimizing photobleaching.

- Spatial Sampling: Set voxel size to approximately 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.5 µm (x,y,z) to satisfy Nyquist sampling for most objectives.

- Temporal Parameters: Adjust frame averaging and scanning speed to balance temporal resolution with image quality. For tracking most morphogenetic movements during embryogenesis, 2-5 minute intervals between 3D stacks typically suffice.

- Multi-Position Imaging: When imaging multiple embryos, implement tile scanning or predefined position lists to maximize data throughput.

Data Processing:

- Background Subtraction: Apply rolling-ball or top-hat algorithms to correct for uneven illumination.

- Drift Correction: Use cross-correlation or feature-based registration to compensate for sample drift during extended time-lapses.

- Deconvolution: Apply iterative restoration algorithms (e.g., constrained iterative, blind deconvolution) to improve effective resolution, particularly for multi-channel data.

Line-Scanning Brillouin Microscopy Protocol

System Configuration:

- Laser Source: Implement a narrowband (50 kHz) tunable 780 nm diode laser, frequency-stabilized by locking to atomic transitions (e.g., D2 line of ⁸⁷Rb) using absorption spectroscopy.

- Background Suppression: Use a gas cell as an ultra-narrowband notch filter for suppression of inelastically scattered Rayleigh light to within ~80 dB.

- Detection Path: Employ a high-resolution CCD camera coupled with a spectrometer optimized for high spatial resolution and background suppression across a ~200 µm field of view.

- Geometry Selection: Choose between orthogonal-line (O-LSBM) for minimal illumination dosage or epi-line (E-LSBM) to mitigate scattering and optical aberrations.

Sample Mounting and Environmental Control:

- Mechanical Stabilization: Use specialized mounting systems such as the cobweb holder approach, consisting of a stainless-steel cylinder with a slotted hole (2 mm × 4 mm) to which agarose-embedded specimens are attached.

- Environmental Chamber: Implement a custom miniaturized incubation chamber for full environmental (temperature, CO₂, O₂) control during time-lapse observations.

- Hydration Maintenance: Use fluorinated ethylene propylene foil to physically isolate the specimen chamber from the objective's immersion media while maintaining hydration.

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Spectral Processing: Implement GPU-optimized numerical fitting routines for real-time spectral data analysis, providing >1,000-fold enhancement in processing time compared to CPU-based pipelines.

- Mechanical Property Mapping: Calculate Brillouin shift (vB) and linewidth (ΓB) to deduce elastic and viscous properties, respectively, with spectral precision <20 MHz.

- Correlative Imaging: Acquire concurrent selective plane illumination microscopy (SPIM) fluorescence images to guide Brillouin image analysis and correlate mechanical properties with specific tissue regions or molecular constituents.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy experimental workflow for live embryo imaging.

Decision framework for selecting appropriate live imaging modalities based on research objectives.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Live Embryo Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Composition | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | 1× concentration, pH 7.4 | Embryo washing and dehydration prevention | Maintains osmotic balance during sample preparation |

| Sodium Hypochlorite Solution | 1:9 dilution of ~10% stock in PBS | Chemical dechorionation | 90-second treatment typically sufficient for Drosophila embryos |

| Low-Melt Agarose | 0.7-1.0% in appropriate buffer | Embryo embedding and mechanical stabilization | Provides optical clarity while immobilizing specimens |

| Culture Medium | Species-specific formulation | Maintaining embryo viability during imaging | May require oxygenation for extended observations |

| Fluorescent Labels | GFP, RFP, or synthetic dyes | Highlighting specific structures or molecules | Nuclear-localized EGFP effective for tracking cell movements |

| Immersion Media | Water, glycerol, or specialized oils | Coupling objectives to sample chambers | Must match objective specifications and minimize refractive index mismatch |

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy remains an indispensable tool for high-resolution cellular and subcellular tracking in embryo development research, particularly when balanced spatial and temporal resolution is required. However, the comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that emerging technologies each offer distinct advantages for specific applications. Super-resolution techniques provide unparalleled spatial resolution for elucidating subcellular architecture, while light-sheet microscopy excels at long-term volumetric imaging of delicate developmental processes with minimal phototoxicity.

The optimal choice of imaging modality depends critically on the specific research question, with factors including required spatial and temporal resolution, sample viability constraints, and data processing capabilities all influencing instrument selection. As imaging technologies continue to evolve, multimodal approaches that combine the strengths of multiple techniques will likely provide the most comprehensive insights into the complex dynamics of embryo development.

Time-lapse imaging (TLI) has emerged as a transformative technology in clinical in vitro fertilization (IVF), enabling continuous monitoring of embryo development through the capture of morphokinetic parameters. This technology provides a stable culture environment by eliminating the need to remove embryos from incubators for conventional morphological assessment, while generating quantitative data on the timing of key developmental events. This review comprehensively compares TLI's performance against conventional embryo selection methods, synthesizing current evidence on its clinical effectiveness. We examine the foundational kinetic parameters utilized for embryo evaluation, detail standardized methodologies for their application, and analyze the growing integration of artificial intelligence in enhancing selection algorithms. Furthermore, we contextualize TLI within the broader landscape of live imaging techniques for embryo development research, providing researchers and clinicians with an evidence-based assessment of its current capabilities and limitations in clinical practice.

Time-lapse imaging (TLI) represents a significant technological advancement in assisted reproductive technology (ART) laboratories, introducing modern optical systems into traditional embryo culture paradigms [37]. This system integrates an incubator with built-in microscopy and camera components connected to an external computer, capturing embryo images at defined regular intervals across multiple focal planes throughout the culture period [38]. These sequential images are compiled into a video timeline, enabling embryologists to observe the dynamic process of embryo development more intuitively and objectively than with static morphological assessments [37].

The clinical implementation of TLI addresses two fundamental aspects of embryo culture: maintaining undisturbed culture conditions and enhancing embryo selection. By eliminating the need to remove embryos from stable incubator conditions for routine morphological evaluation, TLI minimizes exposure to fluctuations in temperature, pH, and humidity that can potentially stress developing embryos [39]. Furthermore, TLI provides a continuous developmental record rather than the snapshot perspectives available through conventional methods, allowing embryologists to document and evaluate embryo morphology and the timing of developmental events through continuous image tracking [40] [41]. This detailed morphokinetic analysis has given rise to new quantitative markers for embryo selection that extend beyond traditional morphological grading systems [40].

As IVF clinics worldwide face increasing pressure to improve success rates while promoting single embryo transfer to minimize multiple pregnancies, technologies like TLI that potentially enhance embryo selection have gained significant traction [39] [37]. This review systematically examines the kinetic parameters derived from TLI, their methodological applications, and the current evidence regarding their effectiveness in improving clinical outcomes compared to conventional embryology practices.

Key Kinetic Parameters in TLI Assessment

The value at which embryo development reaches a specific state or time point is referred to as an embryo dynamics parameter [37]. These parameters provide quantitative metrics for evaluating embryonic development, though some controversy exists regarding the precise terminology and definitions for specific terms [37]. The most fundamental reference point for embryonic division is t0, representing the time of fertilization. For intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles, t0 is clearly defined as the time of sperm injection, while for conventional IVF, the precise moment of fertilization is less certain [37]. To address this variability, some researchers advocate using the time of the first cytokinesis groove (tcf1) as a standardized reference point for all treatment cycles [37].

Table 1: Fundamental Morphokinetic Parameters in Time-Lapse Imaging

| Parameter | Definition | Developmental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| tPNf | Time of pronuclear fading | Marks completion of fertilization process |

| t2 | Time to 2 completely divided blastomeres | First cleavage event; shorter times associated with better prognosis |

| t3 | Time to 3 completely divided blastomeres | - |

| t4 | Time to 4 completely divided blastomeres | Key parameter for implantation prediction |

| t5 | Time to 5 completely divided blastomeres | - |

| t8 | Time to 8 completely divided blastomeres | Important for blastocyst development prediction |

| tB | Time to blastocyst formation | Indicator of developmental competence |

| cc2 | Cell cycle duration from 2-cell to 3-cell stage (t3-t2) | Measure of cleavage synchrony |

| s2 | Synchronization of 2nd cell division (t4-t3) | Indicator of division regularity |

Beyond these fundamental timing parameters, additional calculated intervals provide insights into the synchrony and regularity of cell divisions. The parameter "cc" (cleavage cycle) has been defined differently by various research groups. Some scholars use "cc" to indicate the time for doubling the number of cells (cc2 for time from 2-cell to 4-cell phase, cc3 for time from 4-cell to 8-cell phase), while others define it as the duration of a specific cell phase (cc2 as duration of the 2-cell phase, calculated as t3-t2) [37]. Another parameter, s2, represents the duration of the embryo at the 3-cell stage (t4-t3) and reflects the synchronization of the second cell division [37].

Research indicates that implanted embryos generally progress through key developmental stages more rapidly than non-implanted embryos. Specifically, embryos that successfully implant typically reach the 2-cell, 3-cell, 4-cell, 5-cell, and 8-cell stages faster than those that fail to implant, consistent with conventional morphological evaluation research indicating that embryos with faster cleavage rates generally have higher implantation potential [37]. However, the predictive value of specific parameters varies across studies, with some reporting conflicting results regarding the significance of certain kinetic markers like s3 (synchronization of the third cleavage division) [37].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized TLI Culture and Imaging Protocols

The implementation of TLI in clinical settings requires standardized protocols to ensure consistent and reliable data acquisition. In typical research settings, such as that described by Chen et al., oocytes and embryos are cultured in specialized TLI systems like the EmbryoScope+ (Vitrolife, Sweden) in pre-equilibrated EmbryoSlides containing global culture medium (G-TL, Vitrolife, Sweden) under a controlled atmosphere (typically 5% O2, 6% CO2) [42]. Image acquisition occurs automatically at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 minutes) across multiple focal planes (e.g., 11 planes) using minimal illumination such as a single red LED (635 nm) to minimize potential light exposure effects [42].

Fertilization checks are performed approximately 19 hours post-insemination or injection, with abnormal fertilizations (1 or 3+ pronuclei) excluded from further consideration [42]. Embryo development is subsequently assessed using integrated software platforms (e.g., EmbryoViewer, Vitrolife) that facilitate annotation of key morphokinetic parameters according to established guidelines [42]. These annotations typically include: time to syngamy (tPNf), times to specific cell stages (t2, t3, t4, t5, t8), and time to blastocyst formation (tB) [42].

Diagram 1: Standard TLI workflow from oocyte collection to embryo transfer

Quality Assessment and Embryo Grading Protocols

In research settings, embryo quality is typically assessed using combined morphological and kinetic grading systems. For example, in the study by Chen et al., embryos were evaluated on days 2 and 3 of development using the BLEFCO classification system, which assesses cell number, fragmentation level, symmetry among blastomeres, and compaction degree [42]. According to this classification, embryos graded ≥4.1.2. or 4.2.1. at day 2 and ≥8.1.2. or 8.2.1. at day 3 are considered good quality [42]. Blastocysts are typically assessed using the Gardner and Schoolcraft classification system, with good-quality blastocysts defined as those with expansion grade ≥3, inner cell mass (ICM) grade ≥B, and trophectoderm grade ≥B on day 5 [42].

Additionally, embryos are often scored using automated algorithms such as the KIDScore D3 v1.2 and KIDScore D5 v3.1, which integrate multiple morphokinetic parameters to generate numerical scores predictive of implantation potential [42]. Embryos displaying abnormal cleavage patterns (such as direct or reverse cleavage) are typically discarded, as these abnormalities are associated with reduced developmental potential [42].

Comparative Effectiveness Analysis

Clinical Outcomes: TLI vs. Conventional Methods

The fundamental question regarding TLI technology is whether it improves clinical outcomes compared to conventional embryo culture and selection methods. Recent high-quality evidence from a large multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial (the TILT study) provides compelling data on this issue. This trial, published in 2024, assigned 1575 participants undergoing IVF or ICSI to one of three groups: TLI for undisturbed culture and embryo selection, TLI for undisturbed culture alone (with standard morphology selection), or standard care without TLI [43].

The results demonstrated no significant differences in live birth rates between the groups: 33.7% (175/520) in the TLI group, 36.6% (189/516) in the undisturbed culture-only group, and 33.0% (172/522) in the standard care group [43]. The adjusted odds ratio was 1.04 (97.5% CI 0.73 to 1.47) for TLI versus control and 1.20 (0.85 to 1.70) for undisturbed culture versus control [43]. These findings indicate that, compared to standard embryo incubation and selection, the use of TLI systems for embryo culture and selection does not significantly increase the odds of live birth following IVF or ICSI treatment.

Table 2: Comparative Clinical Outcomes of TLI vs. Conventional Methods

| Outcome Measure | TLI with Morphokinetic Selection | Undisturbed Culture Only | Standard Care | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live Birth Rate | 33.7% (175/520) | 36.6% (189/516) | 33.0% (172/522) | Not significant (p>0.05) |