Mastering DNA Repair Pathways in Zebrafish: A Comprehensive Guide to NHEJ and HDR for Precision Genome Editing

This comprehensive review explores the mechanisms and applications of double-strand break repair pathways—Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—in the zebrafish model.

Mastering DNA Repair Pathways in Zebrafish: A Comprehensive Guide to NHEJ and HDR for Precision Genome Editing

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the mechanisms and applications of double-strand break repair pathways—Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—in the zebrafish model. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we examine the fundamental biology distinguishing these pathways, practical methodologies for implementing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing, strategies for optimizing repair outcomes, and rigorous validation approaches. The article synthesizes current best practices from recent studies, including chemical enhancement of HDR efficiency and standardization protocols, providing an essential resource for advancing precision genetic modeling and therapeutic discovery in biomedical research.

The Cellular Machinery: Understanding NHEJ and HDR Mechanisms in Zebrafish

Fundamental Principles of Double-Strand Break Repair

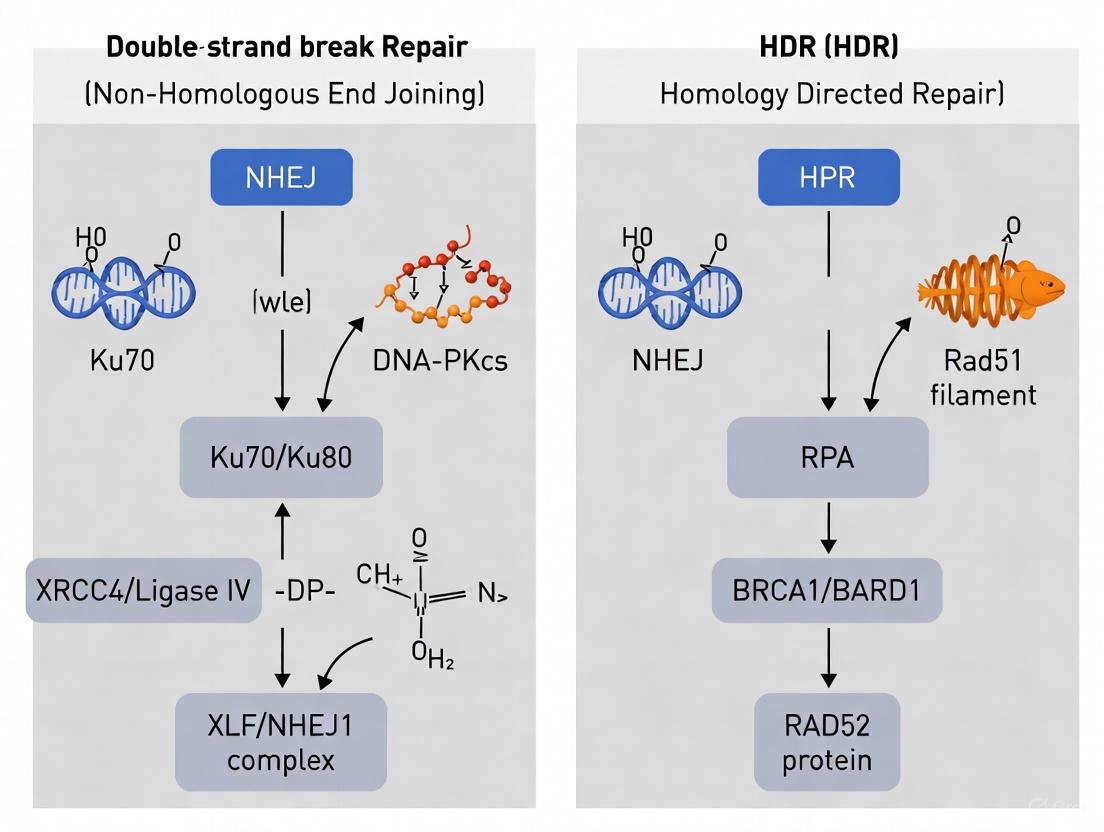

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) represent one of the most critical forms of DNA damage, posing an immediate threat to genomic integrity through potential chromosome rearrangements and disruption of gene function [1]. The fundamental principles governing DSB repair are essential knowledge for researchers utilizing model organisms like zebrafish in biomedical research and drug development. In mammalian cells, two major pathways predominate in DSB repair: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR), with homology-directed repair (HDR) representing a precise subset of homologous recombination [1] [2]. The cellular choice between these pathways is not random but is tightly regulated by cell cycle phase, chromatin context, and the specific nature of the DNA break itself [1]. Understanding these principles provides the foundation for developing precise genome-editing tools and therapeutic strategies aimed at manipulating DNA repair for research and clinical applications.

Core DSB Repair Pathways

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Classical Non-Homologous End Joining (cNHEJ) operates as a rapid, high-capacity pathway that functions throughout the cell cycle, making it the default DSB repair mechanism in mammalian cells [1] [3]. This pathway initiates with the binding of the Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer to DSB ends, which nucleates the recruitment of other essential cNHEJ factors including DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), DNA ligase IV (LIG4), and associated scaffolding factors XRCC4, XRCC4-like factor (XLF), and paralogue of XRCC4 and XLF (PAXX) [1] [3]. The cNHEJ mechanism involves a two-stage synapsis process where Ku70-Ku80 and DNA-PKcs first establish long-range synapsis, followed by close end alignment requiring XLF, non-catalytic functions of XRCC4-LIG4, and DNA-PKcs kinase activity [1]. End processing by nucleases like Artemis and specialized DNA polymerases ensures compatibility of ligated ends [1]. A significant characteristic of cNHEJ is its ability to join DNA ends with minimal reference to DNA sequence, though it can accommodate very limited base-pairing (up to ~4 base pairs of "microhomology") between processed DNA ends [1]. While this makes cNHEJ efficient throughout the cell cycle, it also renders it potentially error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair junction [3].

Homologous Recombination and Homology-Directed Repair

Homologous Recombination (HR) represents a more precise DSB repair pathway that is largely restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when an undamaged sister chromatid is available as a repair template [1] [2] [3]. The critical step committing a DSB to HR is 5'-to-3' resection of DNA ends to form 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [1] [3]. This process initiates with the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex, which recruits CtBP-interacting protein (CtIP) to begin resection [1]. Subsequently, Exonuclease 1 (EXO1) and the BLM-DNA2 complex perform long-range resection, generating extensive 3' ssDNA tails [1] [3]. The resulting ssDNA is rapidly bound by replication protein A (RPA), which must later be replaced by the RAD51 recombinase with assistance from recombination mediators including BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 [1] [3]. The RAD51-nucleoprotein filament then mediates homology search and strand invasion into the homologous DNA template, generating a displacement loop (D-loop) [1]. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) specifically refers to the process where this homologous recombination machinery copies information from a provided DNA template to repair the break precisely [3]. Several subpathways exist beyond D-loop formation, including double-strand break repair (DSBR), synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), and break-induced replication (BIR), with SDSA being the most preferred in somatic cells as it yields non-crossover products [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major DSB Repair Pathways

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homologous Recombination (HR) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function | Direct ligation of broken ends | Templated repair using homologous sequence |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Throughout cell cycle | Primarily S and G2 phases |

| Template Required | No | Yes (sister chromatid or donor DNA) |

| Key Initiating Factor | Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer | MRN complex with CtIP |

| Resection Dependent | No | Yes (5'-to-3' resection) |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (small indels) | High-fidelity |

| Primary Regulatory Kinase | DNA-PKcs | ATM |

| Essential Mediators | DNA-PKcs, XRCC4-LIG4 complex, Artemis | BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51, PALB2 |

Pathway Choice and Regulatory Mechanisms

The decision between NHEJ and HR pathways represents a critical juncture in DSB repair with significant implications for genomic integrity. Mammalian cells preferentially employ NHEJ over HDR through several biological mechanisms: NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle except mitosis, while HDR is restricted to S and G2 phases; NHEJ operates more rapidly than HDR; and NHEJ actively represses HDR through a series of mechanisms [3]. A key determinant of pathway choice is the initiation of DNA end resection, which commits breaks to the HR pathway while preventing NHEJ [1] [3]. The MRN complex serves as a central player in this decision point, functioning as a scaffold for ATM activation while also initiating resection in conjunction with CtIP [1]. BRCA1 promotes end resection and later stages of HR, working in complex with its heterodimeric partner BARD1 and interacting with CtIP and MRN [1]. The Ku70-Ku80 complex not only initiates NHEJ but also protects DNA ends from resection, thereby antagonizing HR [1]. Additionally, 53BP1 promotes NHEJ by protecting DNA ends from resection and counteracting BRCA1 function [3]. Recent research has revealed that the regulatory "rules" governing stalled replication fork repair differ substantially from those operating at conventional two-ended DSBs, suggesting contextual modulation of pathway choice [1].

Experimental Applications in Zebrafish Research

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have emerged as a pivotal model organism for DSB repair research and genome engineering applications due to their genetic similarity to humans, transparent embryos, rapid development, and high fecundity [4] [5]. The application of DSB repair principles in zebrafish research has enabled sophisticated genome editing approaches that leverage both NHEJ and HDR pathways.

CRISPR-Cas9 and DSB Repair-Mediated Editing

Traditional CRISPR-Cas9 editing in zebrafish introduces targeted DSBs that are subsequently repaired by endogenous cellular machinery, primarily resulting in NHEJ-mediated indels that can disrupt gene function [4]. While HDR-mediated knock-in approaches using exogenous donor DNA templates enable precise genome modifications, this process occurs less efficiently than NHEJ in zebrafish, mirroring the challenge observed in mammalian systems [6]. To address this limitation, researchers have developed strategies to modulate repair pathway choice, including cell cycle synchronization and inhibition of NHEJ factors to favor HDR outcomes [3].

Advanced Genome Editing Technologies

Base editing technology has revolutionized precise genome engineering in zebrafish by enabling direct chemical conversion of one DNA base into another without inducing DSBs, thereby bypassing the competitive repair pathway choice altogether [4] [5]. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) facilitate C•G to T•A conversions through fusion of catalytically impaired Cas9 with cytidine deaminase enzymes, while adenine base editors (ABEs) promote A•T to G•C conversions using engineered adenine deaminases [4] [5]. The development of zebrafish-codon-optimized editors like AncBE4max has enhanced editing efficiency approximately threefold compared to earlier systems [4]. More recently, prime editing systems have been employed in zebrafish, utilizing Cas9-reverse transcriptase fusion proteins programmed with prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) to directly copy edited sequences into target genomic loci without requiring DSBs [6]. Comparative studies in zebrafish demonstrate that PE2 (nickase-based) editors are more effective for single-nucleotide substitutions, while PEn (nuclease-based) editors show superior efficiency for inserting short DNA fragments up to 30 bp [6].

Table 2: Genome Editing Approaches Leveraging DSB Repair Principles in Zebrafish

| Editing Technology | Mechanism | Key Components | Efficiency in Zebrafish | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 (NHEJ) | DSB induction with error-prone repair | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA | High (varies by target) | Gene knockout, random mutagenesis |

| HDR-Mediated Knock-in | DSB induction with templated repair | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA, donor DNA template | Low (<10% typically) | Precise sequence insertion, gene correction |

| Cytosine Base Editing (CBE) | Direct base conversion without DSB | dCas9 or nCas9, cytidine deaminase, UGI | 9-28% (BE3); ~90% (AncBE4max) [4] | Point mutation introduction, disease modeling |

| Adenine Base Editing (ABE) | Direct base conversion without DSB | dCas9 or nCas9, adenine deaminase | Similar range to CBE | Point mutation introduction, disease modeling |

| Prime Editing (PE2) | Reverse transcription without DSB | Cas9 nickase, reverse transcriptase, pegRNA | 8.4% for nucleotide substitution [6] | Single-nucleotide variants, small edits |

| Prime Editing (PEn) | DSB induction with homology-assisted repair | Cas9 nuclease, reverse transcriptase, pegRNA | 4.4% for substitution; higher for insertions [6] | Short DNA fragment insertion (up to 30 bp) |

HDR Enhancement Strategies and Associated Risks

Recent research has explored pharmacological inhibition of NHEJ factors to enhance HDR efficiency in genome editing. Inhibition of DNA-PKcs using compounds like AZD7648 has shown potential to increase HDR rates by redirecting repair toward homologous recombination [7]. However, a 2025 study revealed that despite increasing apparent HDR efficiency, AZD7648 treatment during genome editing causes frequent kilobase-scale and megabase-scale deletions, chromosome arm loss, and translocations that evade detection by standard short-read sequencing methods [7]. In RPE-1 p53-null cells, AZD7648 increased kilobase-scale deletion frequency by 2.0-fold to 35.7-fold depending on the locus, reaching 43.3% of reads at the GAPDH target site [7]. Similarly, in primary human CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), AZD7648 increased large deletion frequency by 1.2-fold to 4.3-fold across three target loci [7]. These findings highlight the critical importance of comprehensive genotyping when deploying HDR-enhancing strategies and suggest that AZD7648 converts small-scale NHEJ outcomes into larger genetic alterations [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DSB Repair Studies in Zebrafish

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in DSB Repair Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Wild-type SpCas9, HiFi Cas9 | Induces targeted DSBs to engage endogenous repair pathways |

| Base Editors | BE3, BE4max, AncBE4max, Target-AID, ABE | Enables precise nucleotide conversion without DSB induction |

| Prime Editors | PE2, PEn | Programs precise edits without donor templates via reverse transcription |

| HDR Enhancement Reagents | AZD7648 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor) | Shifts repair balance toward HDR by inhibiting NHEJ [7] |

| Repair Pathway Reporters | FIRE (Fluorescent Insertional Repair) reporter | Quantifies HDR vs. NHEJ efficiency in live cells [7] |

| Zebrafish-Specific Delivery Tools | Codon-optimized editors, hei-tag nuclear localization | Enhances efficiency in zebrafish models through improved nuclear import [4] |

| Analytical Tools | Long-read sequencing (Oxford Nanopore), ddPCR, scRNA-seq | Detects large-scale structural variations from editing [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Prime Editing in Zebrafish

The following protocol outlines the methodology for precise genome editing in zebrafish using prime editing technology, based on established research [6]:

Reagent Preparation

- Prime Editor Selection: Choose between nickase-based PE2 for single-nucleotide substitutions or nuclease-based PEn for short DNA fragment insertions (up to 30 bp).

- Guide RNA Design: Design prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) containing:

- Target-specific spacer sequence (typically 20 nt)

- Reverse transcriptase (RT) template encoding desired edit

- Primer binding site (PBS, ~13 nt)

- Homology arm extension for PEn/pegRNA experiments (~13 nt)

- Optional Refolding Procedure: To prevent misfolding between spacer and PBS/RT template sequences, implement a refolding protocol involving denaturation at 65°C for 5 minutes followed by slow cooling to room temperature.

Microinjection Setup

- Sample Preparation: Combine Prime Editor mRNA (100-200 ng/μL) with synthesized pegRNA (50-100 ng/μL) in nuclease-free injection buffer.

- Embryo Collection: Harvest zebrafish embryos within 30 minutes post-fertilization at the one-cell stage.

- Microinjection: Inject 1-2 nL of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex into the cell cytoplasm or yolk near the cell interface.

- Incubation Conditions: Maintain injected embryos at 32°C for optimal prime editor activity [6].

Genotype Analysis

- DNA Extraction: At 96 hours post-fertilization (hpf), extract genomic DNA from pooled embryos (n=10) or individual specimens.

- Target Amplification: Perform PCR amplification of the target genomic region using primers flanking the edit site.

- Editing Assessment:

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay: Detect sequence modifications through mismatch cleavage of heteroduplex PCR products.

- Amplicon Sequencing: Clone PCR products and sequence individual clones or perform next-generation sequencing to characterize editing precision and efficiency.

- Efficiency Calculation: Determine precise editing efficiency as the ratio of correctly edited sequences to total analyzed sequences.

The fundamental principles of double-strand break repair revolve around the competitive interplay between the rapid but error-prone NHEJ pathway and the precise but context-restricted HR/HDR pathway. In zebrafish research, understanding these mechanisms has enabled the development of increasingly sophisticated genome editing technologies that either exploit endogenous repair pathways or bypass them entirely. While base editing and prime editing represent significant advances for precise genome manipulation, traditional CRISPR-Cas9 approaches coupled with HDR enhancement strategies continue to evolve, albeit with newly recognized risks of large-scale genomic alterations. The continued refinement of these tools, guided by fundamental principles of DSB repair, promises to enhance both basic research and therapeutic applications in zebrafish models and beyond.

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) serves as the primary and most rapid cellular defense mechanism for repairing DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) across all cell cycle stages, with particular dominance during G0 and G1 phases when sister chromatids are unavailable as repair templates [8]. This pathway functions as a constant genomic guardian, directly ligating broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [9] [10]. While this template-independent nature enables rapid repair, it also renders NHEJ inherently error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair junction [9] [8]. In the context of zebrafish research, understanding the intricate balance between NHEJ and homology-directed repair (HDR) is fundamental for designing effective gene editing strategies, as NHEJ often competes with precise HDR-based editing approaches [11] [10].

Molecular Mechanism of NHEJ

The NHEJ pathway operates through a coordinated sequence of protein recruitment and catalytic activities that recognize, process, and ligate broken DNA ends. The process can be delineated into three core stages, visualized in the following diagram and detailed in subsequent sections.

End Binding and Tethering

NHEJ initiation occurs when the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer recognizes and tightly binds to exposed DNA ends [9] [8]. This basket-shaped complex slides onto the DNA end and translicates inward, forming a stable ring that protects ends from degradation and prevents premature separation [9]. In vertebrates, Ku recruits the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), which becomes activated upon DNA binding and phosphorylates various substrates to coordinate subsequent repair steps [8] [12]. Simultaneously, the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 (MRX in yeast) or Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN in mammals) complex promotes bridging of the DNA ends, maintaining them in proximity for repair [9].

End Processing

Before ligation can occur, damaged or incompatible DNA ends often require processing to create ligatable termini [9]. The Artemis nuclease plays crucial roles in opening DNA hairpins generated during V(D)J recombination and trimming damaged nucleotides during general NHEJ [9] [8]. For gap filling, the X-family DNA polymerases Pol λ and Pol μ (Pol4 in yeast) perform template-independent synthesis to add missing nucleotides, with Pol μ being particularly important for gap filling at 3' overhangs where the primer terminus is less stable [9] [8].

Ligation

The final and definitive step in NHEJ involves ligation of processed DNA ends by the specialized DNA ligase IV complex [9]. This complex consists of the catalytic subunit DNA ligase IV and its essential cofactor XRCC4, which stabilizes the ligase and enhances its activity [9] [12]. XLF (also known as Cernunnos) interacts with this complex and likely promotes re-adenylation of DNA ligase IV after ligation, recharging the enzyme for multiple catalytic cycles [9]. The rejoining of DNA ends by this complex restores chromosomal integrity, albeit potentially with small sequence alterations [8].

Quantitative Analysis of NHEJ Activity

Cell Cycle Regulation and Efficiency

NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle but demonstrates variable activity and dominance compared to homologous recombination (HR), as quantitatively demonstrated in normal human fibroblasts:

Table 1: NHEJ and HR Efficiency Across Cell Cycle Phases in Human Fibroblasts [13]

| Cell Cycle Phase | NHEJ Activity | HR Activity | Relative Pathway Dominance |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Active | Nearly absent | NHEJ exclusively dominant |

| S | Increases 1.5-3x vs. G1 | Most active | Both active, HR peaks |

| G2/M | Highest activity | Declines from peak | NHEJ elevated, HR declining |

This cell cycle regulation stems from mechanistic constraints: NHEJ can function without a sister chromatid, making it essential in G1, while HR requires a homologous template primarily available during and after DNA replication [13] [12]. The critical regulatory step involves 5' end resection, which commits breaks to HR and inhibits NHEJ; this resection is controlled by cyclin-dependent kinases that are inactive in G1 [9].

NHEJ in Zebrafish Gene Editing

In zebrafish research, NHEJ represents both a challenge and opportunity for genome engineering. When creating specific mutations via HDR, NHEJ competes with precise editing, often resulting in unintended indels. Analysis of successful HDR experiments in zebrafish reveals optimal conditions for suppressing NHEJ while promoting HDR:

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Optimal Conditions for HDR in Zebrafish [11]

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Cutting Efficiency | >60% | Ensures sufficient DSB induction to engage repair mechanisms |

| DSB-Target Proximity | Within 20 nucleotides | Facilitates homologous template access to break site |

| Homology Arm Symmetry | Symmetric or asymmetric | Both can be effective with proper design |

| PAM Site Modification | Essential | Prevents re-cleavage of successfully edited loci |

| Microinjection Stage | 1-2 cell stage | Enables incorporation into germline |

| Template Topology | Single-stranded or double-stranded DNA | Both effective with proper design considerations |

Experimental Approaches for NHEJ Inhibition in Research

Chemical Inhibition Strategies

The development of NHEJ inhibitors provides powerful tools for dissecting pathway functions and potentially enhancing cancer therapies. Recent research has investigated SCR130, a specific ligase IV inhibitor, for its potential to radiosensitize cancer cells:

Methodology Overview:

- Cell Lines: Multiple HNSCC cell lines (Cal33, CLS-354, Detroit 562, HSC4, RPMI 2650, UD-SCC-2, UM-SCC-47) and healthy fibroblasts (SBLF9, 01-GI-SBL) [12]

- Inhibitor Treatment: 30 µM SCR130 (diluted in DMSO) [12]

- Irradiation Protocol: Single dose of 2 Gy ionizing radiation using ISOVOLT Titan X-ray generator [12]

- Assessment Endpoints: Cell death (flow cytometry), clonogenicity (colony formation), DNA damage (γH2AX foci), cell cycle distribution (propidium iodide staining), gene expression (qPCR) [12]

Key Findings: SCR130 treatment combined with IR showed limited radiosensitizing effects that were highly cell line-specific. However, it consistently increased G0/G1 phase arrest concomitant with gained p21 expression, suggesting anti-proliferative effects rather than direct cell death induction [12].

Genetic and Molecular Approaches

Beyond chemical inhibition, genetic approaches provide alternative strategies for NHEJ manipulation:

- NHEJ Gene Disruption: CRISPR-mediated knockout of core NHEJ factors (Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, Ligase IV, XRCC4) [14]

- NHEJ Inhibition in HDR Workflows: Using NHEJ inhibitors to enhance HDR efficiency in precision genome editing [11]

- Variant Analysis: Computational assessment of missense variants in NHEJ components to understand molecular consequences on protein stability, interactions, and function [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for NHEJ Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for NHEJ Investigation

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| SCR130 | Selective DNA ligase IV inhibitor | Probing NHEJ function; potential radiosensitizer in cancer cells [12] |

| Ku Antibodies | Immunodetection of Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer | Verifying protein expression and cellular localization [14] [8] |

| NHEJ Reporter Cassettes | GFP-based systems with engineered I-SceI endonuclease sites | Quantifying NHEJ efficiency in different cell types and conditions [13] |

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitors (e.g., Peposertib) | Block DNA-PKcs kinase activity | Clinical investigation of NHEJ inhibition combined with radiotherapy [12] |

| Pol λ/μ Antibodies | Detect X-family polymerases | Assessing polymerase recruitment to break sites [9] [8] |

| XRCC4/LIG4 Variant Libraries | Collections of clinically identified mutations | Studying molecular drivers of NHEJ-related diseases [14] |

Implications for Zebrafish Research and Therapeutic Development

In zebrafish models, the interplay between NHEJ and HDR has profound implications for disease modeling and functional genomics. The error-prone nature of NHEJ is frequently exploited to generate gene knockouts through frameshift mutations, while HDR enables precise genetic modifications [11] [10]. The competition between these pathways necessitates strategic intervention; inhibiting NHEJ through chemical or genetic approaches can significantly enhance HDR efficiency in zebrafish embryo microinjections [11].

Beyond basic research, understanding NHEJ has direct therapeutic applications. Defects in NHEJ components are linked to human disorders including severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), microcephaly, growth delay, and cancer predisposition [9] [14]. Conversely, cancer cells often exhibit increased reliance on NHEJ due to HR deficiencies, creating therapeutic opportunities for NHEJ inhibitors in combination with DNA-damaging agents [12]. As zebrafish continue to emerge as valuable models for human disease and drug discovery, precisely manipulating DNA repair pathway choices remains essential for advancing both basic science and therapeutic development.

In the landscape of CRISPR-based genome editing, the controlled repair of CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) is paramount. While non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) offers efficient but error-prone repair, homology-directed repair (HDR) provides a precise, template-dependent pathway for accurate genome modification [10] [15]. In zebrafish research, a premier model for vertebrate biology and human disease modeling, mastering HDR is particularly valuable. Zebrafish share approximately 70% of human disease-related genes, making them an essential tool for functional validation [6] [16]. However, HDR-mediated precise genome editing occurs less efficiently than random mutagenesis, presenting a significant challenge for researchers [6]. This in-depth technical guide explores the mechanisms, optimization strategies, and experimental protocols for enhancing HDR efficiency in zebrafish, framed within the broader context of DSB repair pathways.

Core Mechanisms of DNA Repair Pathways

The Cellular Repair Landscape

When a DSB occurs, multiple competing repair pathways are activated. The choice between these pathways is a critical decision point that researchers can influence to achieve desired editing outcomes.

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental decision point after a DSB. NHEJ is the dominant, error-prone pathway that ligates broken ends without a template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) ideal for gene knockout studies [10] [15]. In contrast, HDR uses a homologous DNA template to precisely repair the break, enabling accurate sequence integration [10]. Alternative pathways like microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) also contribute to repair outcomes and can be targeted to improve HDR efficiency [17].

The Critical Role of Pathway Competition

A primary challenge in precise genome editing is the innate cellular preference for NHEJ over HDR. NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle and is faster, while HDR is restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases when homologous templates are available [15]. This competition significantly limits HDR efficiency, with studies in zebrafish showing that even under optimized conditions, imprecise integration can account for nearly half of all integration events despite NHEJ inhibition [17]. Consequently, shifting the repair equilibrium toward HDR is a central focus of optimization efforts.

Quantitative Analysis of HDR Efficiency and Optimization

Template Design and Composition

The design and type of repair template significantly influence HDR efficiency. The table below summarizes key findings from quantitative studies in zebrafish.

Table 1: Impact of Template Design on HDR Efficiency in Zebrafish

| Template Type | Experimental Efficiency | Key Advantages | Reported Germline Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long ssDNA (zLOST) | ~98% phenotypic rescue [18] | High efficiency, precise modification | Up to 31.8% [18] |

| Chemically Modified Templates | Outperformed plasmid-released templates [19] | Reduced degradation/concatemerization | >20% at multiple loci [19] |

| ssODN with Optimized Arms | 1-4% error-free repair rate [20] | Suitable for point mutations | Sufficient for F1 transmission [20] |

| Plasmid DNA (circular) | Variable, often lower efficiency [18] [19] | Convenient for larger inserts | Highly variable |

Chemical and Genetic Reprogramming of Repair Pathways

Strategic inhibition of competing repair pathways can substantially enhance HDR efficiency. Research has identified several small molecules that modulate key pathway components.

Table 2: Small Molecule Modulators to Enhance HDR Efficiency in Zebrafish

| Small Molecule | Target Pathway | Effect on HDR | Reported Efficacy in Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|---|

| NU7441 | NHEJ (DNA-PK inhibitor) | Dramatic HDR enhancement [16] | Up to 13.4-fold increase [16] |

| ART558 | MMEJ (POLQ inhibitor) | Reduces large deletions [17] | Increases perfect HDR frequency [17] |

| D-I03 | SSA (Rad52 inhibitor) | Reduces asymmetric HDR [17] | Decreases imprecise donor integration [17] |

| RS-1 | HDR (RAD51 activator) | Modest HDR stimulation [16] | Statistically significant but modest increase [16] |

Nuclease Selection and Cutting Characteristics

The choice of CRISPR nuclease and the proximity of the cut site to the intended edit are critical parameters.

- Cas9 vs. Cas12a: While Cas9 is the most widely used nuclease, Cas12a recognizes a different PAM sequence (TTTN) and creates a 5-nt 5' overhang rather than a blunt end. This distinct cutting profile is thought to potentially contribute to higher HDR rates at some loci [19].

- Cut-to-Edit Distance: A consistent finding across studies is that HDR efficiency is highly dependent on the distance between the DSB and the target sequence for modification. Designs should place the cut site as close as possible to the intended edit, ideally within 20 nucleotides [11] [19].

Advanced HDR Techniques and Experimental Protocols

The zLOST Protocol for Efficient Knock-In

The zebrafish Long Single-Stranded DNA Template (zLOST) method represents a significant advancement for precise mutation introduction [18].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Template Generation: Produce a long single-stranded DNA (lssDNA) donor (e.g., 299-512 nt) containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms.

- Microinjection Setup: Co-inject into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos:

- zCas9 mRNA or recombinant Cas9 protein

- Target-specific gRNA

- zLOST donor template

- Embryo Incubation: Incubate injected embryos at standard laboratory temperatures (e.g., 28.5°C) until analysis.

- Efficiency Assessment: For visible phenotypes (e.g., tyr rescue), score phenotypic rescue. For non-visible edits, use PCR-based methods and sequencing.

- Germline Transmission: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to wild-type fish. Screen F1 progeny for precise integration.

Key Advantages:

- Demonstrated precise repair at the tyr locus in nearly 98% of injected embryos [18]

- Achieved germline transmission rates up to 31.8% [18]

- Successfully applied to model human disease mutations (e.g., twist2 E78Q and rpl18 L51S) [18]

Chemical Reprogramming Protocol

This protocol utilizes small molecule inhibitors to shift the repair equilibrium toward HDR [16].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Critical Optimization Notes:

- Treatment Timing: Inhibitor treatment should begin immediately post-injection and continue for 24 hours, covering the window when HDR typically occurs after Cas9 delivery [17] [16].

- Quantitative Assessment: Use single-cell resolution analysis (e.g., counting individual fluorescent cells) rather than qualitative presence/absence assessment, as the latter can mask the effects of HDR stimulation [16].

Prime Editing as an Alternative Strategy

Prime editing offers a template-dependent editing approach that does not require a DSB or donor DNA template [6].

Implementation Considerations:

- PE2 vs. PEn: The nickase-based PE2 editor is more effective for single-nucleotide substitutions, while the nuclease-based PEn editor shows higher efficiency for inserting short DNA fragments (up to 30 bp) [6].

- Applications: Particularly valuable for introducing stop codons or short peptide tags without requiring a donor DNA template [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HDR in Zebrafish

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9 mRNA/protein, Cas12a (Cpf1) | Induces targeted double-strand breaks at genomic loci of interest [17] [19] |

| Repair Templates | zLOST (lssDNA), ssODN, dsDNA with chemical modifications | Serves as homologous donor for precise HDR-mediated repair [18] [19] |

| Pathway Inhibitors | NU7441 (NHEJi), ART558 (MMEJi), D-I03 (SSAi) | Shifts repair equilibrium toward HDR by blocking competing pathways [17] [16] |

| HDR Enhancers | RS-1 (RAD51 activator) | Stimulates the HDR pathway directly [16] |

| Validation Tools | Long-read sequencing (PacBio), T7E1 assay, flow cytometry | Confirms precise editing outcomes and quantifies efficiency [17] [18] [19] |

HDR remains the gold standard for precise genome editing in zebrafish, yet its efficiency is constrained by cellular pathway competition. Through optimized template design (e.g., zLOST, chemically modified donors), strategic pathway modulation (NHEJ/MMEJ/SSA inhibition), and careful nuclease selection, researchers can significantly enhance HDR outcomes. The integration of advanced techniques like prime editing and deep-learning-assisted template design [21] promises further improvements. As these methodologies continue to evolve, HDR will become increasingly robust, enabling more sophisticated genetic modeling of human diseases in zebrafish and accelerating drug discovery pipelines.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have emerged as a preeminent vertebrate model for elucidating the complexities of DNA repair mechanisms. Their genetic architecture shares a remarkable 71% of protein-coding genes and 82% of human disease-associated genes, providing a highly relevant system for translational research [22]. This whitepaper details the foundational attributes—including external development, optical transparency, and genetic tractability—that position zebrafish as an ideal organism for dissecting double-strand break (DSB) repair pathways such as Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). We further present advanced CRISPR-based functional genomics tools, quantitative experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions that leverage the zebrafish system to accelerate discovery in genome maintenance and therapeutic development.

The study of DNA repair mechanisms is critical for understanding genome integrity, disease etiology, and cancer biology. Zebrafish offer a unique combination of vertebrate biology and experimental practicality that is unparalleled for in vivo investigation of DNA repair pathways. Several intrinsic characteristics solidify their status as a powerful model system. Their high fecundity and rapid ex utero development facilitate the generation of large cohorts for high-throughput genetic and chemical screens [22]. The optical transparency of embryos and availability of pigment mutants enables real-time, high-resolution imaging of cellular processes, including the recruitment of repair factors to damage sites in living organisms.

Furthermore, the zebrafish genome has been fully sequenced, and a rich repository of genetic tools is available. A key advantage is the ease of genetic manipulation; CRISPR-Cas technologies enable highly efficient gene knockout and precise genome editing [23]. The establishment of mutant lines for DNA repair genes, such as those involved in the Fanconi anemia pathway, has revealed that these genes are not only crucial for genome maintenance but also impact fundamental biological processes like sex determination and differentiation [22]. This ability to model complex human disease phenotypes in a tractable vertebrate system makes zebrafish an indispensable asset for functional genomics and preclinical research.

The DNA Repair Landscape in Zebrafish

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are among the most deleterious DNA lesions, and their accurate repair is essential for cell viability. Zebrafish possess the full repertoire of conserved DSB repair pathways, each with distinct mechanisms and outcomes.

Key Repair Pathways

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is the dominant, error-prone pathway that ligates broken DNA ends without a template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). It is a rapid process active throughout the cell cycle and is commonly exploited to generate gene knockouts [15] [10] [23].

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): Also an error-prone pathway, MMEJ relies on short sequence microhomologies (2-20 bp) flanking the break to guide repair, typically resulting in deletions of the intervening sequence. A key factor in this pathway is DNA polymerase theta (Polθ/POLQ), which is highly conserved between zebrafish and humans [24] [25].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This is a high-fidelity pathway that uses a homologous DNA template (such as a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor) for precise repair. HDR is the preferred mechanism for introducing specific point mutations or inserting sequences like fluorescent protein tags, though its efficiency is lower than that of NHEJ [15] [10] [16].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways in Zebrafish

| Pathway | Template Required | Fidelity | Key Zebrafish Factors | Primary Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | No | Error-prone | DNA Ligase 4 (Lig4) | Gene knockout studies via indel generation [15] [23] |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | No (uses microhomology) | Error-prone | DNA Polymerase Theta (Polθ), nuclear DNA Ligase 3 (nLig3) [24] | Studying repair-associated mutagenesis; modeling genomic instability |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Yes | High-fidelity | Rad51, BRCA2 [22] | Precise gene knock-in, point mutation modeling, and endogenous tagging [26] |

Pathway Interplay and Expression Dynamics

The choice of repair pathway is not static but is dynamically regulated during development. Research has shown that the expression of genes related to cNHEJ and MMEJ is dynamic during zebrafish embryonic development and often increases in specific tissues [24]. Studies mutating key pathway components reveal a complex interplay:

- Loss of Polθ (MMEJ) sensitizes embryos to ionizing radiation and alters the mutation spectrum from Cas9-induced DSBs [24].

- Loss of Lig4 (cNHEJ) leads to significant larval growth defects but does not profoundly affect embryo survival under non-stressed conditions, suggesting other pathways can compensate [24].

This context-dependent requirement of repair pathways underscores the importance of using an in vivo model like zebrafish to understand their regulation in a developing, multicellular organism.

Advanced Functional Genomics Tools

The CRISPR-Cas revolution has been fully embraced in zebrafish research, enabling sophisticated functional genomics at an unprecedented scale and precision.

High-Throughput Mutagenesis and Screening

The scalability of CRISPR in zebrafish allows for systematic, high-throughput interrogation of gene function. Pioneering studies have successfully targeted hundreds of genes to identify those essential for specific biological processes. Examples include:

- A screen of 254 genes to identify regulators of hair cell and tissue regeneration [23].

- A screen of over 300 genes for their role in retinal regeneration or degeneration [23].

- Targeted mutation of zebrafish orthologs of 132 human schizophrenia-associated genes and 40 childhood epilepsy-associated genes [23].

These large-scale efforts demonstrate the power of zebrafish for directly linking human genetic variants to physiological outcomes.

Precision Genome Editing with Base Editors

Beyond inducing DSBs, base editors have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling precise single-nucleotide modifications without creating double-strand breaks [5]. Both cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) have been widely applied in zebrafish.

- CBEs catalyze C:G to T:A conversions and have been used to model diseases like oculocutaneous albinism [5].

- ABEs catalyze A:T to G:C conversions, expanding the scope of possible edits [5].

Recent developments, such as "near PAM-less" editors (e.g., CBE4max-SpRY), have further expanded the targeting scope, allowing access to virtually all genomic sequences with efficiencies as high as 87% at some loci [5]. This level of precision is invaluable for modeling human genetic diseases caused by point mutations.

Table 2: Evolution of Key Base Editing Tools in Zebrafish

| Editor System | Key Features and Improvements | Demonstrated Application in Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|

| BE3 | First CBE system used in zebrafish [5] | Microinjection of mRNA or RNP complexes; efficiency of 9.25–28.57% [5] |

| Target-AID | Unique editing window targeting −19 to −16 nucleotides upstream of PAM [5] | Complementary targeting range to other base editors [5] |

| AncBE4max | Codon-optimized for zebrafish; ~3x higher efficiency than BE3 [5] | Inducing oncogenic mutations in tumor suppressor genes (e.g., tp53) for cancer modeling [5] |

| CBE4max-SpRY | "Near PAM-less" cytidine base editor [5] | Bypasses traditional NGG PAM requirement; achieves editing efficiencies up to 87% [5] |

Experimental Protocols for DNA Repair Studies

This section provides detailed methodologies for investigating and manipulating DNA repair pathways in zebrafish.

Visual Quantification of HDR Efficiency

An in vivo visual reporter assay allows for the quantitative analysis of HDR events at single-cell resolution in live zebrafish embryos [16].

Workflow Description: The diagram illustrates a transgenic zebrafish embryo assay used to quantify Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). The process starts with a transgenic embryo expressing eBFP2 in fast-muscle fibers. A donor DNA template containing the tdTomato gene flanked by homology arms is designed. The embryo is co-injected with Cas9 protein, eBFP2-targeting sgRNA, and the donor template. When Cas9 creates a double-strand break in the eBFP2 gene, the donor template can be used for HDR, leading to the replacement of eBFP2 with tdTomato. Successful HDR is quantified by counting the resulting red fluorescent muscle fibers in the live embryo.

Protocol Steps:

- Reporter Strain: Use a stable transgenic zebrafish line expressing eBFP2 (blue fluorescent protein) specifically in fast-muscle fibers under the control of the

acta1promoter [16]. - Donor Template Construction: Design a donor DNA fragment containing the

tdTomato(red fluorescent protein) gene flanked by homology arms (e.g., 303 bp left arm, 1022 bp right arm) that are homologous to sequences in theeBFP2transgene. The donor should include the sgRNA target site within the homology arm to promote HDR [16]. - Microinjection: Co-inject one-cell stage embryos with:

- Cas9 protein complexed with sgRNA targeting

eBFP2. - The linearized

tdTomatodonor DNA template.

- Cas9 protein complexed with sgRNA targeting

- Chemical Enhancement (Optional): To shift repair toward HDR, include the NHEJ inhibitor NU7441 (50 µM), which has been shown to enhance HDR efficiency up to 13.4-fold in this assay [16].

- Quantification: At 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf), image the trunk musculature. Count the number of fast-muscle fibers that have successfully switched fluorescence from blue (eBFP2) to red (tdTomato) using fluorescence microscopy. This provides a direct, quantitative readout of somatic HDR events [16].

Analyzing DSB Repair Pathway Outcomes

To dissect the contributions of different repair pathways to the mutation spectrum, one can sequence the outcomes of CRISPR-induced breaks in wild-type and DNA repair-deficient mutants.

Workflow Description: The diagram outlines an experimental pipeline to analyze DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair outcomes. The process begins by introducing DSBs into zebrafish embryos via microinjection of Cas9 and guide RNAs (gRNAs). Genomic DNA is then extracted from the embryos. The target loci are amplified from the DNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These amplicons are then subjected to long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio). The resulting sequencing data is analyzed using a computational genotyping framework (e.g., knock-knock) to classify each read into specific repair outcomes, such as perfect HDR, indels from NHEJ, or deletions characteristic of MMEJ. The frequency of these outcomes can be compared between wild-type embryos and those deficient in specific repair pathways (e.g., polq MMEJ mutants).

Protocol Steps:

- DSB Induction: Microinject wild-type and mutant (e.g.,

polq,lig3,lig4) zebrafish embryos with Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes targeting specific genomic loci [24] [17]. - DNA Extraction and Amplification: At the desired stage, extract genomic DNA from pools of embryos. Perform PCR to amplify the genomic regions flanking the Cas9 target site(s) [17].

- Deep Sequencing: Subject the PCR amplicons to long-read amplicon sequencing (e.g., PacBio) to capture the full spectrum of repair events, including large deletions [17].

- Computational Genotyping: Analyze the sequencing data using a framework like

knock-knockto classify each sequencing read into specific categories:- Wild-type sequence

- Perfect HDR (if a donor was supplied)

- Small indels (characteristic of NHEJ)

- Deletions using microhomology (characteristic of MMEJ)

- Other complex rearrangements [17].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the distribution of repair outcomes between genotypes. For example,

polq(MMEJ) mutants show a reduction in large deletions and complex indels, revealing the specific mutagenic signature of the MMEJ pathway [24] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful DNA repair studies in zebrafish rely on a suite of well-defined reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Zebrafish DNA Repair Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Specification | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease (protein or mRNA) | Induces site-specific double-strand breaks guided by sgRNA [15] [23] | Gene knockout via NHEJ; creating DSBs for HDR and MMEJ studies [23] |

| Base Editor Systems (e.g., AncBE4max) | Fuses catalytically impaired Cas9 to a deaminase enzyme for precise single-base changes without DSBs [5] | Modeling human genetic diseases caused by point mutations (e.g., in oncogenes or tumor suppressors) [5] |

| Homology-Directed Repair Donor Template | Provides the correct DNA sequence for precise repair; can be single-stranded oligos or double-stranded DNA with homology arms [26] | Introducing specific point mutations or inserting protein tags (e.g., GFP) into endogenous genes [16] [26] |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., NU7441) | Chemical inhibitor of DNA-PK, a key kinase in the NHEJ pathway [16] | Enhancing HDR efficiency by suppressing the competing error-prone NHEJ pathway; shown to increase HDR up to 13.4-fold in zebrafish [16] |

| MMEJ/SSA Inhibitors (e.g., ART558, D-I03) | ART558 inhibits Polθ (MMEJ); D-I03 inhibits Rad52 (SSA) [17] | Reducing specific imprecise repair patterns in knock-in experiments; improving the accuracy of genomic integrations [17] |

| DNA Repair-Deficient Mutant Lines (e.g., polq, lig4, unga) | Zebrafish strains with loss-of-function mutations in specific DNA repair genes [22] [24] | Studying the in vivo function of a specific repair gene and its interaction with other pathways; analyzing mutation spectra [24] |

Zebrafish provide an unmatched combination of physiological relevance and experimental power for the study of DNA repair mechanisms. Their high genetic homology to humans, coupled with advanced, scalable CRISPR-Cas tools, enables the direct functional validation of variants identified in human patients. The ability to quantitatively monitor and manipulate the interplay between NHEJ, HDR, and MMEJ pathways in a living, developing vertebrate offers insights that are simply not attainable in cell culture systems. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve toward ever-greater precision and scope, the zebrafish model will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of functional genomics, disease modeling, and the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at safeguarding genomic integrity.

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA are critical lesions that, if not properly repaired, can lead to genomic instability, carcinogenesis, and cell death [15] [27]. In vertebrate cells, including zebrafish, two principal pathways compete to repair DSBs: the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and the high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR) [15] [27]. The cellular decision-making process that determines pathway choice is a crucial biological phenomenon with profound implications for genome editing, disease modeling, and therapeutic development. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful vertebrate model for elucidating these mechanisms due to its genetic tractability, optical transparency, and conservation of DNA repair pathways with humans [28] [29] [27]. This review synthesizes current understanding of the factors governing NHEJ/HDR pathway choice, with specific focus on insights gained from zebrafish models.

DNA Repair Pathways: Mechanisms and Key Players

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

NHEJ is an error-prone DNA repair pathway that functions throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [15] [10]. This pathway is faster and more efficient than HDR but often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site [15]. The classic NHEJ pathway involves the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer recognizing and binding to DSB ends, followed by recruitment of DNA-PKcs, Artemis, XLF, XRCC4, and DNA Ligase IV to process and ligate the ends [30]. In zebrafish, NHEJ is the dominant DSB repair pathway and is particularly efficient for generating gene knockouts [15] [16].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

HDR is a precise repair mechanism that utilizes homologous sequences (typically a sister chromatid or exogenously supplied donor template) as a blueprint for accurate DSB repair [15] [10]. This pathway is restricted to the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when homologous templates are available [15]. The core HDR mechanism in zebrafish involves resection of DNA ends to create 3' single-stranded overhangs, followed by RAD51 filament formation with the assistance of BRCA2, and strand invasion into the homologous template [27]. HDR is essential for precise genome editing applications, including knock-ins and specific point mutations [10] [18].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of NHEJ and HDR Pathways in Zebrafish

| Feature | NHEJ | HDR |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | No homologous template needed | Requires homologous template (sister chromatid or donor DNA) |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout cell cycle | Primarily late S and G2 phases |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (often creates indels) | High-fidelity (precise repair) |

| Efficiency in Zebrafish | High (dominant pathway) | Low (typically <10% without intervention) |

| Key Proteins | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, Ligase IV | BRCA2, RAD51, RAD52 |

| Primary Applications | Gene knockouts, gene disruption | Precise knock-ins, point mutations, tag insertions |

Alternative Repair Pathways

Beyond classical NHEJ and HDR, zebrafish possess additional DSB repair pathways including microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) [30]. MMEJ relies on 2-20 nucleotide microhomologous sequences flanking the broken junction and frequently results in deletions [30]. SSA utilizes Rad52-dependent annealing of longer homologous sequences and can lead to significant sequence deletions between repeats [30]. These alternative pathways contribute to the complex landscape of DSB repair outcomes in CRISPR-mediated genome editing.

Factors Governing Pathway Choice

The decision between NHEJ and HDR pathways is influenced by a complex interplay of cellular, molecular, and experimental factors. Research in zebrafish has been instrumental in elucidating these determinants.

Cell Cycle Phase

The cell cycle represents a fundamental determinant of pathway choice, with HDR restricted to late S and G2 phases when sister chromatids are available as repair templates [15] [27]. Evidence from zebrafish embryos demonstrates that HDR-capable cells are those in late S-/G2-phase, as visualized through geminin positivity in intestinal cells [27]. This cell cycle dependency fundamentally limits HDR efficiency, as only a subset of cells are competent for homologous recombination at any given time.

DNA End Resection

The initial processing of DSB ends represents a critical branch point in repair pathway choice [11]. Limited resection promotes NHEJ by preserving DNA ends for direct ligation, while extensive 5'→3' resection creates 3' single-stranded overhangs that favor HDR [11]. In zebrafish, the balance between resection factors and NHEJ machinery determines the cellular commitment to either pathway, with proteins like CtIP and MRE11 promoting resection and HDR.

Expression and Activity of Repair Proteins

The relative abundance and activity of key repair proteins significantly influence pathway choice. Zebrafish studies have demonstrated that BRCA2 deficiency essentially abolishes RAD51 foci formation following irradiation, indicating complete abrogation of HDR [27]. Similarly, heterozygous deficiency of Brca2 results in significantly reduced RAD51 foci, suggesting haploinsufficiency that may predispose to tumorigenesis [27]. Competition between Ku70/80 (NHEJ) and BRCA2/RAD51 (HDR) for binding to DSB ends constitutes a crucial mechanistic point of pathway regulation.

Developmental Stage

DNA repair pathway activity and regulation vary significantly during zebrafish embryonic development [31]. Early embryos possess maternally deposited DNA repair transcripts but have compromised DNA damage recognition and checkpoint activation until the mid-blastula transition (MBT) [31]. The delayed activation of proper DNA damage response mechanisms may represent an adaptation to ensure rapid embryonic cell divisions, even under genotoxic stress.

Template Availability and Nature

The availability, design, and delivery method of homologous templates significantly impact HDR efficiency in zebrafish. Research demonstrates that long single-stranded DNA (lssDNA) templates (zLOST method) achieve dramatically higher HDR efficiency (up to 98.5% phenotypic rescue at the tyr locus) compared to double-stranded or short single-stranded templates [18]. Optimal homology arm length and symmetry further enhance HDR rates [11] [18].

Table 2: Experimental Factors Influencing HDR Efficiency in Zebrafish

| Factor | Optimal Condition | Effect on HDR Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Template Type | Long ssDNA (zLOST) | Up to 98.5% rescue at tyr locus [18] |

| Template Length | 299-512 nt | Significant improvement over shorter templates [18] |

| Homology Arm Symmetry | Symmetric arms | Moderate improvement (≤3%) [18] |

| sgRNA Efficiency | >60% cutting efficiency | Critical for successful HDR [11] |

| PAM Site Alteration | Modified in repair template | Prevents re-cutting of repaired targets [11] |

| DSB-Target Proximity | Within 20 nucleotides | Standard for efficient HDR [11] |

Experimental Modulation of Pathway Choice

Chemical Reprogramming

Small molecule inhibitors provide a powerful approach to shift the repair equilibrium toward HDR in zebrafish. NU7441, a DNA-PK inhibitor that blocks NHEJ, enhances HDR efficiency up to 13.4-fold in zebrafish embryos [16]. Similarly, RS-1 (RAD51 stimulator) shows a modest but significant increase in HDR, while SCR7 (Lig4 inhibitor) demonstrates minimal effects in zebrafish despite efficacy in other models [16]. These findings highlight the species-specific nature of chemical modulation and the importance of empirical validation in zebrafish.

Diagram 1: DNA Repair Pathway Decision and Chemical Modulation. The diagram illustrates key steps in NHEJ (red) and HDR (green) pathways, highlighting points of chemical intervention with NU7441 (NHEJ inhibitor) and RS-1 (HDR enhancer).

Multi-Pathway Suppression Strategies

Recent evidence suggests that simultaneous suppression of multiple repair pathways can further enhance precise editing outcomes. While NHEJ inhibition alone significantly increases perfect HDR events, imprecise integration still accounts for nearly half of all integration events [30]. Additional suppression of MMEJ (via POLQ inhibition) or SSA (via Rad52 inhibition) reduces nucleotide deletions around the cut site and decreases asymmetric HDR events, thereby further improving knock-in accuracy [30]. This multi-pathway approach represents a promising strategy for achieving ultra-precise genome editing in zebrafish.

Zebrafish-Specific Methodological Advances

The zLOST Method

The zebrafish long single-stranded DNA template (zLOST) method represents a significant advancement in HDR-mediated genome editing in zebrafish [18]. This approach utilizes long single-stranded DNA donors (299-512 nt) containing symmetrical homology arms and achieves remarkable efficiency - restoring pigmentation in close to 98% of albino tyr25del/25del embryos [18]. The method demonstrates precise HDR-dependent repair and achieves germline transmission rates of up to 31.8% [18].

Quantitative HDR Assessment Methods

Zebrafish researchers have developed sophisticated assays for quantifying HDR efficiency. A visual reporter assay using fast-muscle fiber conversion from eBFP2 to tdTomato expression enables quantitative in vivo analysis of HDR events at single-cell resolution [16]. Similarly, the RAD51 foci assay in embryonic intestinal tissue provides accurate quantification of HR activity under various experimental conditions [27]. These quantitative approaches provide robust assessment tools for evaluating HDR enhancement strategies.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for HDR Assessment in Zebrafish. The diagram outlines key components for microinjection (left) and methods for evaluating HDR efficiency (right) in zebrafish embryos.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying DNA Repair Pathways in Zebrafish

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Specific Use in Zebrafish Research |

|---|---|---|

| NU7441 | DNA-PK inhibitor, blocks NHEJ | Enhances HDR efficiency up to 13.4-fold in zebrafish embryos [16] |

| RS-1 | RAD51 stimulator, enhances HDR | Modest but significant increase in HDR efficiency [16] |

| ART558 | POLQ inhibitor, suppresses MMEJ | Reduces large deletions and complex indels in knock-in experiments [30] |

| D-I03 | Rad52 inhibitor, suppresses SSA | Decreases asymmetric HDR and imprecise donor integration [30] |

| Long ssDNA Templates | Donor template for HDR | zLOST method achieves up to 98.5% phenotypic rescue at tyr locus [18] |

| Anti-RAD51 Antibody | Immunostaining for HR quantification | Enables Rad51 foci assay in proliferative intestinal tissue [27] |

| BrdU | S-phase marker | Identifies proliferating cells for HR capability assessment [27] |

| γH2AX Antibody | DSB marker | Confirms DSB induction after irradiation [27] |

The cellular decision-making process governing NHEJ versus HDR pathway choice represents a complex biological phenomenon influenced by cell cycle phase, DNA end resection, repair protein expression, developmental stage, and template availability. Zebrafish has proven to be an invaluable model for elucidating these mechanisms, offering insights that bridge fundamental biology and applied genome editing. Methodological advances such as the zLOST platform, combined with chemical reprogramming strategies and sophisticated quantitative assays, have dramatically improved precise genome editing outcomes in zebrafish. These developments not only enhance our fundamental understanding of DNA repair pathway choice but also establish zebrafish as a powerful platform for modeling human diseases and advancing therapeutic development. Future research directions include refining multi-pathway suppression strategies, developing temporal control over repair pathway choice, and applying these insights to improve precision in therapeutic genome editing.

Key Protein Players and Their Roles in Each Repair Pathway

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) represent one of the most deleterious forms of DNA damage, posing a serious threat to genomic stability. If left unrepaired or misrepaired, DSBs can lead to cell death, chromosomal aberrations, and oncogenic transformations [32]. Eukaryotic cells have evolved two primary mechanisms to repair DSBs: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR). The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful vertebrate model for studying these DNA repair pathways due to its high genetic conservation with humans, optical transparency during embryonic development, and genetic tractability [24] [16]. This review provides a comprehensive technical guide to the key protein players in NHEJ and HDR pathways, framed within the context of zebrafish research, to facilitate advanced studies in functional genomics and drug development.

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) Pathway

NHEJ is the predominant DSB repair pathway in vertebrate cells, responsible for repairing up to ~80% of all DSBs [32]. It is characterized by the direct ligation of broken DNA ends without a homologous template, making it active throughout all phases of the cell cycle, particularly in G0 and G1 [8]. While this pathway is fast and efficient, it is inherently error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair junction [15]. In zebrafish, NHEJ is the dominant pathway for repairing DSBs induced by CRISPR-Cas9, making it crucial for gene knockout studies [24] [15].

Core NHEJ Protein Players and Their Functions

The NHEJ pathway employs a sophisticated array of proteins that recognize, process, and ligate broken DNA ends. The table below summarizes the key protein players and their specific roles in the NHEJ pathway.

Table 1: Key Protein Players in the NHEJ Pathway

| Protein Complex/Enzyme | Proposed Role(s) in NHEJ |

|---|---|

| Ku70/Ku80 Heterodimer | Initial DSB sensor and interaction hub; forms a ring-shaped structure that encircles DNA ends; recruits downstream NHEJ factors [32] [33]. |

| DNA-PKcs | Serine/threonine protein kinase activated by DNA binding; phosphorylates NHEJ substrates; involved in end synapsis and acts as a molecular "gate" regulating access to DNA ends [32] [33]. |

| XRCC4 | Forms a constitutive complex with DNA Ligase IV; interacts with XLF to promote synapsis [32] [33]. |

| DNA Ligase IV (LIG4) | Catalyzes the final ligation step; can tolerate certain terminal mismatches and damaged bases [32] [33]. |

| XLF (XRCC4-like factor) | Interacts with XRCC4 to stabilize synapsis; functions redundantly with PAXX [32]. |

| PAXX (Paralog of XRCC4 and XLF) | Promotes synapsis; provides redundant functions with XLF [32]. |

| Artemis | Endonuclease activated by DNA-PKcs; processes DNA ends by opening hairpin structures (critical for V(D)J recombination) and trimming damaged nucleotides [32] [33]. |

| Pol μ and Pol λ | X-family DNA polymerases that perform template-independent synthesis; fill gaps during end processing [32] [33] [8]. |

Specialized NHEJ Sub-pathways

NHEJ can proceed through distinct sub-pathways depending on the nature of the DNA ends [33]:

- Blunt-end ligation-dependent sub-pathway: For clean breaks, the Ku-XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV complex directly catalyzes ligation.

- Nuclease-dependent sub-pathway: For ends with damaged nucleotides or overhangs, the Artemis:DNA-PKcs complex is recruited to process the ends before ligation.

- Polymerase-dependent sub-pathway: For ends with missing nucleotides, Pol μ and Pol λ are recruited to fill in gaps, sometimes utilizing terminal microhomology.

Diagram: The Core Mechanism of Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Pathway

HDR is a precise, template-dependent repair pathway that utilizes a homologous DNA sequence—typically a sister chromatid or an exogenously provided donor template—to accurately repair the break [15] [34]. This pathway is predominantly active during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when a sister chromatid is available [32]. In zebrafish CRISPR research, HDR is the preferred mechanism for introducing precise point mutations, inserting fluorescent protein tags, or creating other specific genomic modifications, though it is generally less efficient than NHEJ [11] [16].

Core HDR Protein Players and Their Functions

HDR involves a more complex sequence of events than NHEJ, requiring a coordinated interplay between numerous proteins responsible for end resection, strand invasion, and synthesis.

Table 2: Key Protein Players in the HDR Pathway

| Protein Complex/Enzyme | Proposed Role(s) in HDR |

|---|---|

| MRN Complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) | Initiates DNA end resection; generates 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [24]. |

| CtIP | Promotes extensive end resection alongside the MRN complex [11]. |

| RPA | Binds to and stabilizes ssDNA overhangs after resection, preventing secondary structure formation [24]. |

| RAD51 | The central recombinase; forms a nucleoprotein filament on ssDNA and catalyzes strand invasion into the homologous donor template [34]. |

| BRCA2 | Mediator protein that facilitates the loading of RAD51 onto ssDNA [32]. |

| DNA Polymerases (δ/ε) | Perform DNA synthesis using the homologous template to copy genetic information across the break site. |

| DNA Ligase I | Seals the nicks in the DNA backbone after synthesis is complete, finalizing the repair. |

The HDR Process in Zebrafish

The HDR pathway can be broken down into several key stages, as illustrated in the workflow below. This process is leveraged in zebrafish genome editing by co-injecting a donor DNA template alongside CRISPR-Cas9 components.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for HDR-Based Genome Editing in Zebrafish

Experimental Protocols for Zebrafish Research

Enhancing HDR Efficiency in Zebrafish Embryos

A significant challenge in zebrafish precision genome editing is the low efficiency of HDR compared to the competing NHEJ pathway. Research has identified several chemical and technical strategies to shift this balance. A seminal study established a quantitative in vivo reporter assay in zebrafish muscle fibers to screen for small-molecule HDR enhancers [16]. Key findings from this and other studies are summarized below.

Table 3: Strategies to Modulate DNA Repair Pathway Choice in Zebrafish

| Method | Example Agent/Target | Effect on Repair Pathways | Reported Outcome in Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibition | NU7441 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor) [16] | Suppresses c-NHEJ | 13.4-fold enhancement of HDR efficiency; most effective treatment identified [16]. |

| NHEJ Inhibition | SCR7 (Ligase IV inhibitor) | Suppresses c-NHEJ | No significant effect on HDR efficiency in zebrafish [16]. |

| HDR Activation | RS-1 (RAD51 stimulator) [16] | Enhances RAD51 activity | Modest but significant increase in HDR efficiency [16]. |

| Template Design | Asymmetric repair templates [11] | Optimizes donor usability | A standard for improving HDR success rates; cut site should be within 20 nt of the target [11]. |

| Template Topology | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) vs. double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [11] | Influences repair template accessibility | Varies by study; both are successfully used with optimized protocols [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Zebrafish DNA Repair Studies

This table compiles key reagents and their applications for studying or manipulating DNA repair pathways in zebrafish models.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish DNA Repair Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use in Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Induces targeted DSBs at genomic loci of interest. | Foundation for both NHEJ-mediated knockout and HDR-mediated knock-in studies [33] [35]. |

| NU7441 | Small-molecule inhibitor of DNA-PKcs; inhibits c-NHEJ. | Co-injected with CRISPR components to enhance HDR efficiency up to 13.4-fold [16]. |

| RS-1 | Small-molecule enhancer of RAD51 activity; stimulates HDR. | Co-injected to modestly improve HDR-mediated repair [16]. |

| High-Efficiency sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to the specific target locus. | Essential prerequisite; >60% cutting efficiency recommended for HDR experiments [11] [35]. |

| Homology-Donor Template | Provides the homologous sequence for precise repair (ssODN or dsDNA). | Designed with homology arms and altered PAM site to prevent re-cutting [11] [16]. |

| Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) Modulators | Targets a novel redox-dependent regulator of NHEJ. | Protective against DNA damage in whole zebrafish; potential therapeutic target [36]. |

The intricate interplay of protein players in NHEJ and HDR pathways underpins the maintenance of genomic integrity in zebrafish and other vertebrates. NHEJ, driven by the rapid action of Ku, DNA-PKcs, and the Ligase IV/XRCC4/XLF complex, offers a swift but error-prone repair solution. In contrast, HDR, orchestrated by the MRN complex, RAD51, and associated mediators, provides a template-dependent mechanism for high-fidelity repair, albeit with lower intrinsic efficiency in zebrafish. The continued refinement of chemical modulation strategies, such as using NU7441 to inhibit NHEJ, and technical optimizations in reagent design are critical for advancing precise genome editing in this model organism. A deep mechanistic understanding of these pathways and their key protein constituents is indispensable for developing novel therapeutic interventions for human diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, leveraging the unique experimental strengths of the zebrafish system.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated NHEJ and HDR in Zebrafish

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a premier vertebrate model for functional genomics and disease modeling, largely due to its genetic similarity to humans, external development, and optical transparency during early stages [23] [5]. The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic research in this model organism, enabling precise genome modifications that were previously challenging or impossible. CRISPR/Cas9 functions as a programmable gene-editing tool that utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a specific DNA sequence, where it creates a double-strand break (DSB) [37]. This break activates the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, primarily non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR), which researchers can harness to achieve different genetic outcomes [10].

Understanding these repair pathways is fundamental to designing effective CRISPR experiments. NHEJ is an error-prone pathway that directly ligates broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function—making it ideal for gene knockout studies [38] [10]. In contrast, HDR uses a homologous DNA template to repair the break accurately, allowing for precise genetic modifications such as point mutations, gene insertions, or reporter knock-ins [38] [18]. The choice between these pathways depends on the experimental goals, and successful genome editing requires careful design of both gRNAs and repair templates to maximize efficiency while minimizing off-target effects [37].

Guide RNA (gRNA) Design and Optimization

Principles of gRNA Design

The guide RNA is the targeting component of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, responsible for directing the Cas9 nuclease to specific genomic loci. Effective gRNA design must balance on-target efficiency with minimal off-target effects [38] [37]. The gRNA consists of a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that complementary base pairs with the target DNA, immediately adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (5'-NGG-3' for standard Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) [37]. The target sequence should be unique within the genome to prevent off-target editing at similar sites.

Several factors influence gRNA efficiency. The nucleotide composition near the PAM-distal region affects Cas9 binding stability, with guanine-rich sequences often exhibiting higher efficiency [37]. The GC content of the gRNA should ideally range between 40-60%, as extremely low or high GC content can impair binding or promote non-specific interactions [38]. Additionally, the accessibility of the target chromatin region influences editing efficiency, with open chromatin regions typically being more accessible than tightly packed heterochromatin [38].

Bioinformatics Tools for gRNA Design

Several bioinformatics tools have been developed to facilitate optimal gRNA design and off-target prediction. These tools analyze potential gRNA sequences against reference genomes to identify unique targets with minimal off-site activity [37]. Commonly used platforms include:

- CHOPCHOP: A web tool that evaluates gRNA efficiency, scores potential off-target sites, and provides primer design for validation [37].

- Cas-OFFinder: Identifies potential off-target sites by allowing mismatches and bulges in the gRNA-DNA pairing [37].

- CRISPResso: Provides quantitative analysis of CRISPR editing outcomes from sequencing data, helping validate gRNA efficiency and specificity [37].

These tools typically generate efficiency scores for each potential gRNA target, enabling researchers to select the most promising candidates for their experiments. It is recommended to design and test multiple gRNAs for each target gene to ensure at least one produces efficient editing [38].

Repair Template Design for Precise Editing

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Templates

HDR enables precise genome modification by using an exogenous DNA template containing the desired edit flanked by homology arms complementary to the target locus [38] [18]. The design of this repair template significantly impacts HDR efficiency.

Table 1: Comparison of HDR Repair Template Types in Zebrafish

| Template Type | Description | Optimal Length | Advantages | Limitations | Reported Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN (Single-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotide) [39] [18] | Short, single-stranded DNA | 60-180 nt | Easy to synthesize; reduced random integration | Lower efficiency for large inserts; error-prone (1-4% error-free HDR) [39] | 2-8% total HDR (1-4% perfect HDR) [39] |

| lssDNA (Long Single-Stranded DNA) [18] | Long, single-stranded DNA | ~300-500 nt | Higher efficiency than ssODNs; suitable for small inserts | Limited commercial availability | Up to 98.5% phenotypic rescue (tyr locus) [18] |

| dsDNA (Double-Stranded DNA) [18] | Double-stranded DNA (plasmid or PCR product) | >500 bp with homology arms | Suitable for large insertions (e.g., reporters, tags) | Low efficiency; requires larger homology arms | ≤3% (high variability) [18] |

Key considerations for HDR template design include:

- Homology Arm Length: For ssODNs, symmetric arms of 30-60 nucleotides each are commonly used, with longer arms (e.g., 90 nt) potentially increasing HDR rates [39]. For dsDNA templates, arms of 500-1000 bp are typically required.

- Strand Complementarity: Templates complementary to the non-target strand (the strand not binding the gRNA) may slightly improve HDR efficiency [39].

- Modification Protection: Introducing silent mutations in the PAM sequence or the gRNA binding site within the repair template can prevent re-cleavage of successfully edited alleles [38].

Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) Templates

MMEJ is an alternative repair pathway that utilizes microhomology regions (5-25 bp) flanking the DSB [21]. Recent advances leverage predictable MMEJ outcomes for precise integration. The Pythia design tool uses deep learning to predict optimal microhomology sequences, improving frame retention and reducing deletions at integration sites [21]. This approach is particularly valuable in post-mitotic cells where HDR efficiency is low.

Design strategies include:

- Tandem Repeat Arms: Adding 3-6 bp microhomology sequences as tandem repeats at the edges of the transgene cassette safeguards against DNA trimming during integration [21].

- Sequence Context: The nucleotide composition at position -4 relative to the PAM influences integration efficiency, with a guanine (G) base enhancing the process [21].

Advanced Genome Editing Technologies

Base Editing