Mastering In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Guide to Gene Expression Analysis in Developmental Biology

This comprehensive guide provides developmental biologists with a complete framework for implementing and optimizing in situ hybridization (ISH) to visualize spatial and temporal gene expression patterns.

Mastering In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Guide to Gene Expression Analysis in Developmental Biology

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides developmental biologists with a complete framework for implementing and optimizing in situ hybridization (ISH) to visualize spatial and temporal gene expression patterns. Covering foundational principles through advanced applications, the article details robust protocols for model organisms like zebrafish, systematic troubleshooting for common pitfalls such as weak signal and high background, and modern validation techniques including quantitative analysis and integration with single-cell RNA-seq data. Essential reading for researchers aiming to accurately map gene expression during embryonic development and tissue morphogenesis.

Understanding In Situ Hybridization: Core Principles and Applications in Developmental Biology

What is ISH? Defining the technique for spatial gene expression analysis

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that enables the detection, localization, and quantification of specific nucleic acid sequences within intact cells, tissue sections, or entire organisms. By allowing researchers to visualize where and when genes are active, ISH provides a crucial spatial context to gene expression analysis, bridging the gap between molecular biology and histology [1]. This capability is indispensable for understanding how genes function and are regulated within different biological systems, making it particularly valuable for research in developmental biology, disease pathology, and neuroscience [1] [2]. The technique has evolved significantly since its inception, with early methods relying on radioactive probes giving way to safer, more versatile non-isotopic approaches, including colorimetric and fluorescent detection methods [3]. This article explores the principles, protocols, and applications of ISH, with a specific focus on its critical role in developmental biology research.

Core Principles and Probe Design

At its core, ISH operates on the principle of nucleic acid thermodynamics, where complementary strands of DNA or RNA anneal to form stable hybrids under controlled conditions [3]. The technique involves applying a labeled, sequence-specific probe to a biological sample, where it hybridizes to its complementary DNA or RNA target. The location of this hybridization is then visualized through a detection method appropriate to the label used.

The design and choice of probe are critical factors determining the success and specificity of an ISH experiment. The table below summarizes the main probe types used in ISH.

Table 1: Common Probe Types Used in In Situ Hybridization

| Probe Type | Description | Length/Characteristics | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Probes (Riboprobes) | Single-stranded RNA synthesized via in vitro transcription from a DNA template [1]. | 250–1,500 bases; high sensitivity and specificity [1]. | Detecting mRNA expression; whole-mount ISH in embryos [4]. |

| DNA Probes | Double or single-stranded DNA, often labeled by nick translation or PCR [3]. | Variable length; strong hybridization to DNA targets [1]. | Detecting viral DNA, gene amplification (e.g., HER2) [5]. |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences synthesized to target specific mRNA regions [3]. | Typically 20-50 bases; designed for multiple target sites [3]. | Single-molecule FISH (smFISH); highly multiplexed experiments [3]. |

| SABER Probes | DNA probes based on Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction; part of a unified, modular platform [6]. | Adaptable; can be amplified for high sensitivity [6]. | Multiplexed colorimetric and fluorescent ISH in various sample types [6]. |

Probes are typically labeled with a hapten (such as digoxigenin or biotin) or directly with a fluorophore. Non-radioactive digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes are widely used due to their high sensitivity [1]. The specificity of the probe is paramount; even a 5% mismatch in base pairing can lead to loose hybridization and potential loss of signal during washing steps [1].

ISH in Developmental Biology: Protocols and Workflows

In developmental biology, ISH is an irreplaceable tool for visualizing the dynamic expression patterns of genes that orchestrate embryonic patterning, organogenesis, and tissue differentiation. The following workflow, adapted from a protocol optimized for paradise fish embryos, outlines a typical whole-mount ISH procedure [7].

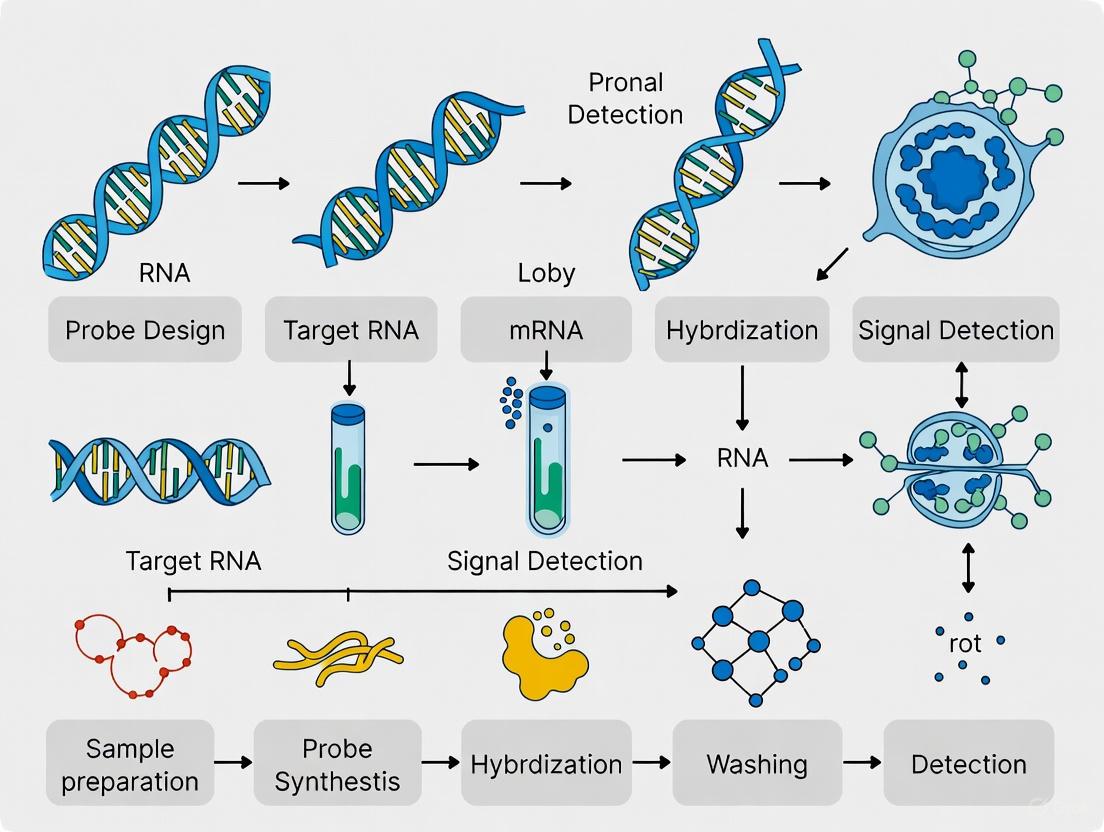

Diagram 1: Whole-mount ISH workflow for embryonic gene expression analysis.

Detailed Protocol: DIG-Labeled RNA ISH

This protocol describes the key steps for detecting mRNA using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes on paraffin-embedded tissue sections or whole-mount embryos [1] [7].

Stage 1: Tissue Preparation and Pre-treatment

- Fixation: Preserve tissue morphology and RNA integrity using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). For whole-mount embryos, fixation time must be optimized to allow probe penetration while preserving anatomy [7].

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: For paraffin-embedded sections, remove wax by sequential washes in xylene and graded ethanol (100%, 95%, 70%, 50%), followed by a rinse in water. Slides must not dry out after this point [1].

- Permeabilization and Protein Digestion: Treat samples with Proteinase K (e.g., 20 µg/mL for 10-20 minutes at 37°C) to digest proteins and allow probe access to the target mRNA. Critical: Concentration and time must be optimized for each tissue type. Over-digestion damages morphology, while under-digestion reduces signal [1].

- Acetic Acid Wash and Dehydration: Immerse slides in ice-cold 20% acetic acid for 20 seconds for further permeabilization, then dehydrate through ethanol series and air dry [1].

Stage 2: Hybridization

- Pre-hybridization: Apply a pre-warmed hybridization solution to the sample and incubate for 1 hour at the desired hybridization temperature (typically 55-62°C) to block non-specific sites [1].

- Probe Hybridization: Denature the DIG-labeled RNA probe at 95°C for 2 minutes, chill on ice, and dilute in fresh hybridization solution. Apply the probe to the sample, cover with a coverslip, and incubate overnight at 65°C in a humidified chamber [1].

Table 2: Hybridization Solution Components [1]

| Reagent | Final Concentration | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | 50% | Reduces hybridization temperature and suppresses non-specific binding. |

| Salts (20x SSC) | 5x | Provides ionic strength for proper nucleic acid hybridization. |

| Dextran Sulfate | 10% | Excludes volume, increasing effective probe concentration. |

| Denhardt's Solution | 5x | Blocks non-specific probe binding to the tissue. |

| Heparin | 20 U/mL | Blocks non-specific binding, particularly to nuclear and extracellular matrix. |

| SDS | 0.1% | Detergent that reduces background. |

Stage 3: Post-Hybridization Washes and Detection

- Stringency Washes: Remove unbound and loosely hybridized probe through a series of washes. A common regimen includes:

- Wash 1: 50% formamide in 2x SSC, 3x 5 min at 37-45°C.

- Wash 2: 0.1-2x SSC, 3x 5 min at 25-75°C. The temperature and salt concentration here determine stringency and must be adjusted based on probe characteristics [1].

- Immunological Detection:

- Blocking: Incubate samples with a blocking buffer (e.g., MABT + 2% BSA or serum) for 1-2 hours at room temperature to prevent non-specific antibody binding [1].

- Antibody Incubation: Apply an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-DIG antibody at the recommended dilution in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [1].

- Washing: Remove excess antibody with multiple washes of MABT buffer (e.g., 5x 10 minutes) [1].

- Colorimetric Detection: Immerse samples in a staining buffer containing the AP substrates BCIP and NBT. The enzymatic reaction produces an insoluble blue/purple precipitate at the site of probe hybridization. Monitor the reaction closely and stop by washing with water or TE buffer once the desired signal-to-noise ratio is achieved [1] [2].

Analyzing Signaling Pathways in Development

ISH is routinely used to map the expression of genes within key signaling pathways that guide embryonic development. By applying the protocol above, researchers can study the effects of pathway manipulation. The following diagram illustrates the role of major pathways and how they can be perturbed with small molecule inhibitors [7].

Diagram 2: Using ISH to study signaling pathways in development.

Table 3: Small Molecules for Perturbing Key Developmental Pathways [7]

| Signaling Pathway | Small Molecule | Action | Expected Phenotype in Fish/Zebrafish Embryos | Gene Expression Changes (Visualized by ISH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP | Dorsomorphin | Inhibitor | Dorsalized embryo: expansion of dorsal structures, reduction of ventral tissues. | Upregulation of dorsal markers (e.g., chordin). |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Lithium Chloride | Inhibitor | Defects in dorso-ventral and antero-posterior axis patterning. | Altered expression of axis patterning genes (e.g., goosecoid). |

| Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) | Cyclopamine | Inhibitor | Curved trunk, reduced horizontal myoseptum, cyclopia. | Loss of Shh-target genes in neural tube and somites. |

| Notch | DAPT (γ-secretase inhib.) | Inhibitor | Defective somite formation, curved body, neural patterning errors. | Altered expression of Notch-target genes (e.g., her genes). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful ISH relies on a suite of specialized reagents, each serving a specific function to ensure high signal-to-noise ratio and preservation of tissue integrity.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for an ISH Laboratory

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled Riboprobes | The core detection reagent; antisense RNA probe complementary to the target mRNA [1]. | Must be designed for high specificity; length optimized (~800 bases); requires linearized DNA template for synthesis [1]. |

| Proteinase K | A critical permeabilization enzyme; digests proteins to allow probe access to mRNA targets [1]. | Concentration and incubation time are highly variable and must be titrated for each tissue and fixation condition [1]. |

| Formamide | A key component of hybridization and stringency wash buffers; denatures nucleic acids and allows hybridization at lower temperatures [1]. | Reduces non-specific binding and tissue damage from high temperatures. Standardly used at 50% concentration [1]. |

| Saline Sodium Citrate (SSC) | The primary salt buffer for hybridization and washing; ionic strength controls "stringency" of hybridization [1]. | Higher concentration (e.g., 2x SSC) is less stringent; lower concentration (e.g., 0.1x SSC) is more stringent and removes mismatched probes [1]. |

| Anti-Digoxigenin-AP Antibody | Conjugate antibody that binds to the DIG hapten on the hybridized probe; alkaline phosphatase (AP) enzyme catalyzes colorimetric reaction [1]. | Must be used in a blocking buffer to minimize non-specific binding to tissue. |

| BCIP/NBT | Alkaline phosphatase substrate; produces an insoluble blue/purple precipitate at the site of probe hybridization [2]. | Reaction must be monitored to prevent high background. Stopped by washing with TE buffer or water. |

Advanced ISH Technologies and Future Directions

The field of spatial transcriptomics has seen explosive growth, with ISH techniques evolving to meet demands for higher multiplexing and quantification [8]. Advanced versions of FISH now allow for the visualization of hundreds to thousands of RNA species simultaneously within a single sample.

- Single-Molecule FISH (smFISH): This highly sensitive method uses multiple short, fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes targeting a single mRNA species, enabling the detection and quantification of individual mRNA transcripts as diffraction-limited spots under a microscope [3] [8].

- Multiplexed Error-Robust FISH (MERFISH): MERFISH is a massively multiplexed smFISH technique that uses a combinatorial barcoding strategy to profile the expression of hundreds to thousands of genes in individual cells while preserving their spatial context [8] [9].

- SABER and OneSABER: Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction (SABER) is a method for signal amplification that uses concatemeric DNA probes to increase sensitivity [6]. The recently developed OneSABER platform provides a unified, open-source framework that uses a single type of DNA probe adaptable for both colorimetric and fluorescent, single and multiplexed ISH applications, increasing accessibility and reducing costs [6].

These advanced ISH technologies are pivotal for creating detailed 3D atlases of gene expression during development, such as the Mouse Organogenesis spatiotemporal Transcriptomic Atlas (MOSTA), which provides unprecedented insights into the molecular basis of cell fate specification [8] [9]. As these methods become more refined and accessible, they will continue to drive discoveries in developmental biology, cancer research, and regenerative medicine.

Analyzing Embryonic Development and Tissue Patterning

In situ hybridization (ISH) is an indispensable technique in developmental biology, enabling researchers to visualize the spatial and temporal distribution of specific RNA transcripts within intact tissues and embryos. This capability is fundamental for deciphering the complex gene expression patterns that orchestrate embryonic development and tissue patterning [10]. The protocol detailed in this application note has been optimized for robustness and accessibility, requiring no specialized instruments and maintaining extremely low economic cost, making it an excellent option for rapid screening and validation of gene expression [10]. By precisely localizing gene activity, this method provides critical insights into the function of developmental genes and the molecular basis of morphological diversity, thereby supporting foundational research with potential applications in understanding developmental abnormalities and guiding drug discovery efforts [11].

Key Applications in Model Organisms

The utility of a well-optimized whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) protocol extends across multiple model organisms, facilitating cross-species comparative studies that illuminate the evolutionary conservation of developmental mechanisms.

Mammalian Models: Mouse Gastrulation

In murine models, this protocol has been successfully employed to uncover crucial regulators of early embryogenesis. For instance, it was instrumental in identifying Pou3f1 as a significant regulator of mouse neuroectoderm development. The optimized WISH protocol revealed Pou3f1's enrichment in the anterior embryonic region of the mouse gastrula, signaling its potential role in embryonic ectoderm development [10]. Subsequent applications of this method have further uncovered additional lineage regulators critical during mouse gastrulation [10]. The protocol is particularly effective for early post-implantation mouse embryos and other small tissue samples, providing high-quality hybridization signals while preserving good tissue morphology [10].

Fish Models: Paradise Fish and Zebrafish

Recent research has adapted and optimized WISH protocols for the Chinese paradise fish (Macropodus opercularis), an emerging model organism with unique physiological adaptations. Initial attempts to apply standard zebrafish protocols to paradise fish were unsuccessful, highlighting the necessity for species-specific optimization [7]. The optimized protocol enabled a comparative analysis of conserved developmental gene expression between paradise fish and the established zebrafish model, focusing on key genes including:

- chordin (chd) and goosecoid (gsc): Involved in dorsal-ventral axis patterning [7]

- myogenic differentiation 1 (myod1): Critical for muscle development [7]

- T box transcription factor Ta (tbxta): Essential for mesoderm formation [7]

- paired box 2a (pax2a) and retinal homebox gene 3 (rx3): Important for eye and central nervous system development [7]

This cross-species comparison provides deeper insights into the evolutionary conservation of early developmental programs and establishes paradise fish as a complementary model system for developmental biology research [7].

Table 1: Key Developmental Genes and Their Expression Patterns

| Gene | Function in Development | Expression Patterns |

|---|---|---|

| chordin (chd) [7] | Dorsal-ventral axis patterning [7] | Dorsal organizing center [7] |

| goosecoid (gsc) [7] | Dorsal mesoderm specification [7] | Anterior embryonic region [7] |

| myoD (myod1) [7] | Myogenic differentiation [7] | Presomitic mesoderm and somites [7] |

| T box transcription factor Ta (tbxta) [7] | Mesoderm formation and differentiation [7] | Notochord and tailbud [7] |

| paired box 2a (pax2a) [7] | Central nervous system and eye development [7] | Midbrain-hindbrain boundary, optic stalk [7] |

| retinal homebox gene 3 (rx3) [7] | Eye field specification [7] | Anterior neural plate, developing eye [7] |

Investigating Signaling Pathways

Beyond gene expression localization, in situ hybridization can be powerfully combined with chemical perturbation to dissect the function of conserved signaling pathways during embryogenesis. Small molecule agonists and antagonists provide a precise method to manipulate pathway activity and observe consequent changes in gene expression patterns.

Pathway-Specific Pharmacological Manipulation

The following small molecule inhibitors are routinely used to interrogate specific signaling pathways:

- BMP Signaling: Dorsomorphin acts as a BMP antagonist, inhibiting BMP type I receptors and leading to dorsalized phenotypes characterized by expanded dorsal structures and reduced ventral tissues [7].

- Wnt Signaling: Lithium Chloride functions as a Wnt antagonist by inhibiting GSK-3β, resulting in axis patterning defects and abnormalities in neural development [7].

- Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) Signaling: Cyclopamine specifically antagonizes the Shh pathway by binding to Smoothened, often producing phenotypes with curved trunks, reduced horizontal myoseptum, and cyclopia [7].

- Notch Signaling: DAPT inhibits γ-secretase activity, preventing Notch receptor cleavage and activation, which disrupts somite formation, neurogenesis, and left-right asymmetry establishment [7].

The combination of these pharmacological tools with spatial gene expression analysis in both zebrafish and paradise fish embryos provides a powerful comparative framework for understanding the evolutionary conservation and plasticity of fundamental developmental pathways [7].

Signaling Pathway Integration in Development

The diagram below illustrates how these key signaling pathways interact to coordinate embryonic patterning.

Diagram 1: Key signaling pathways and their primary roles in embryonic patterning. BMP and Wnt coordinate dorsal-ventral (DV) and anterior-posterior (AP) axis formation, while Shh patterns the central nervous system (CNS) and left-right (LR) asymmetry. Notch signaling regulates somitogenesis and neurogenesis through lateral inhibition.

Table 2: Small Molecule Modulators of Key Developmental Pathways

| Signaling Pathway | Small Molecule | Mode of Action | Phenotypic Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP [7] | Dorsomorphin [7] | BMP type I receptor inhibitor [7] | Dorsalized embryos; expanded dorsal structures, reduced ventral tissues [7] |

| Wnt/β-catenin [7] | Lithium Chloride [7] | GSK-3β inhibitor [7] | Axis patterning defects; neural development abnormalities [7] |

| Sonic Hedgehog [7] | Cyclopamine [7] | Smoothened antagonist [7] | Curved trunk; reduced horizontal myoseptum; cyclopia [7] |

| Notch [7] | DAPT [7] | γ-secretase inhibitor [7] | Defective somite formation; disrupted neurogenesis [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Wholemount In Situ Hybridization

This section provides a comprehensive, step-by-step methodology for wholemount RNA in situ hybridization, optimized for early post-implantation mouse embryos but adaptable to other model organisms [10].

The experimental workflow for wholemount in situ hybridization involves several sequential phases, from sample preparation to signal detection, as illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Wholemount in situ hybridization workflow. The procedure begins with sample collection and fixation, followed by probe synthesis, tissue preparation, hybridization, and detection.

Protocol Steps

A. Embryo Collection and Fixation

- Collect tissue samples or mouse embryos carefully into a 35 mm dish or 24-well plate containing DPBS [10].

- Fix embryos in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight to preserve tissue morphology and immobilize RNA transcripts [10].

- Dehydrate embryos by transferring through a graded methanol series (25%, 50%, 75%, 100% methanol/DPBS), spending 5 minutes in each concentration at room temperature [10].

- Store dehydrated embryos in 100% methanol at -20°C for up to one week [10].

B. Digoxigenin-Labeled RNA Probe Preparation

- Design primers with a minimal T7 promoter sequence (5'-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3') added to the 5' terminal of the forward or reverse primer, depending on the desired transcript strand. Optimal probe length is 600-900 bases for highest sensitivity and specificity [10].

- Amplify probe DNA using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., KOD FX Neo) with a cDNA template enriched for the target transcript. Separate the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis, excise the target band, and purify using a gel extraction kit [10].

- Perform in vitro transcription to synthesize DIG-labeled RNA probes using the following reaction mixture:

Incubate at 37°C for 3 hours [10].Component Volume/Amount Template DNA 1 µg 10× Transcription Buffer 3 µl DIG-Nucleotide Mix 2 µl RiboLock RNase Inhibitor 1 µl T7 RNA Polymerase 2 µl Nuclease-Free Water to 30 µl Total Volume 30 µl - Digest template DNA by adding 0.5 µl DNase I directly to the reaction mix and incubating at 37°C for 15 minutes [10].

- Purify RNA probes using the MEGAclear Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, then dissolve in nuclease-free water [10].

C. Sample Pretreatment and Hybridization

- Rehydrate stored embryos through a reverse methanol series (75%, 50%, 25% methanol/PTW), then wash in 100% PTW buffer [10].

- Perform antigen retrieval and permeabilization by treating embryos with 6% H₂O₂/PTW for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by Proteinase K solution (10 µg/ml for mouse embryos) [10].

- Post-fix embryos in 4% PFA/0.1% glutaraldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature to maintain tissue integrity during subsequent procedures [10].

- Pre-hybridize embryos in hybridization solution for 2-4 hours at 65-70°C [10].

- Hybridize with DIG-labeled probe by adding 0.5-2 µg/ml of RNA probe to fresh hybridization solution and incubating embryos in this solution overnight at 65-70°C [10].

D. Post-Hybridization Washes and Antibody Detection

- Remove unbound probe through a series of stringent washes:

- Block non-specific binding by incubating embryos in blocking buffer (2% Boehringer Blocking Reagent, 20% sheep serum in TBST) for 2-4 hours at room temperature [10].

- Incubate with Anti-Digoxigenin-AP Antibody diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C [10].

- Remove unbound antibody with 8-10 washes in TBST over 6-8 hours [10].

E. Colorimetric Detection

- Equilibrate embryos in NTMT buffer (100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% Tween-20) [10].

- Develop color reaction by incubating embryos in NBT/BCIP stock solution diluted in NTMT buffer in the dark. Monitor development visually and stop the reaction by washing with PTW when desired signal-to-background ratio is achieved [10].

- Post-fix developed embryos in 4% PFA/0.1% glutaraldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature to preserve the signal [10].

- Store samples in 50% Glycerol/PBS solution at 4°C [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the in situ hybridization protocol depends on critical reagents that ensure specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for In Situ Hybridization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation Agents [10] | Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Glutaraldehyde [10] | Preserves tissue architecture and immobilizes RNA transcripts to maintain spatial information [10] |

| Labeling System [10] | DIG RNA Labeling Mix, Anti-Digoxigenin-AP Antibody [10] | Provides non-radioactive labeling and detection system; DIG-labeled nucleotides are incorporated into probes, detected by antibody conjugate [10] |

| Detection Substrate [10] | NBT/BCIP Stock Solution [10] | Chromogenic substrate for alkaline phosphatase; produces insoluble purple precipitate at sites of probe hybridization [10] |

| Permeabilization Agents [10] | Proteinase K, Tween-20 [10] | Enhances tissue permeability to allow probe access to target transcripts while maintaining tissue integrity [10] |

| Hybridization Components [10] | Formamide, SSC, Yeast RNA, Heparin [10] | Creates optimal stringency conditions for specific hybridization; reduces non-specific background binding [10] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors [7] | Dorsomorphin, Cyclopamine, DAPT, LiCl [7] | Chemically perturb specific signaling pathways (BMP, Shh, Notch, Wnt) to study their role in developmental gene expression [7] |

RNA-RNA hybrids, central to techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), provide critical insights into spatial gene expression during development. The choice of probe is pivotal for the success of such experiments. This application note delineates the superior stability and sensitivity of riboprobes (RNA probes) over alternative DNA or oligonucleotide probes in detecting RNA-RNA hybrids. We detail the underlying biophysical mechanisms, present comparative quantitative data, and provide a validated protocol for whole-mount in situ hybridization in zebrafish embryos, a key model organism in developmental biology. The information herein is designed to guide researchers in leveraging the advantages of riboprobes for robust and precise gene expression analysis.

In developmental biology, understanding the spatial and temporal localization of mRNA is fundamental to unraveling the mechanisms of pattern formation, tissue differentiation, and morphogenesis. In situ hybridization (ISH) is a cornerstone technique for this purpose, relying on the thermodynamic principle of complementary base-pairing to visualize target mRNA transcripts within fixed cells, tissues, or whole-mount embryos [3]. When the probing molecule is also RNA, the resulting duplex is an RNA-RNA hybrid. The stability and specificity of this hybrid structure are the primary determinants of assay success. Among the available probes—including DNA and oligonucleotides—riboprobes consistently yield superior results due to the inherent stability of the RNA-RNA duplex [12]. This note elaborates on the technical foundations of this superiority and provides a practical framework for its application in protocol development.

Comparative Analysis of Probe Types

The selection of an appropriate probe is a critical first step in any ISH experiment. The three main probe types—riboprobes, DNA probes, and oligonucleotide probes—each possess distinct characteristics that influence their performance.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ISH Probe Types

| Probe Type | Typical Length | Sensitivity | Stability of Hybrid | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riboprobe (RNA) | 100 - 500+ bp [12] | High to Very High | Very High (RNA-RNA hybrid) | High specificity; use of RNAse to reduce background; sense strand as control [12]. | RNA is labile; requires molecular biology skills for production [12]. |

| Oligonucleotide (DNA) | 20 - 50 nt [12] | Low to Moderate | Lower (DNA-RNA hybrid) | Ease of synthesis and labeling; no requirement for molecular cloning. | Lower sensitivity due to small size; requires high target mRNA copy number [12]. |

| DNA Probe | Variable | Moderate | Moderate (DNA-RNA hybrid) | — | Largely superseded by riboprobes and oligonucleotides. |

The data in Table 1 underscores the principal advantage of riboprobes: their high sensitivity, which is a direct consequence of their length and the superior stability of the RNA-RNA hybrid. RNA-RNA hybrids are more thermally stable than DNA-RNA hybrids, allowing for the use of higher stringency conditions (e.g., higher hybridization temperatures) that minimize non-specific binding and background noise [12]. Furthermore, the ability to use RNAse A in post-hybridization washes selectively degests single-stranded, unbound RNA, further enhancing signal-to-noise ratio without affecting the protected double-stranded hybrid [12].

Mechanism of Superior Stability and Sensitivity

The enhanced performance of riboprobes can be attributed to fundamental biophysical and biochemical properties:

- Structural Stability: The RNA-RNA duplex formed between a riboprobe and its target mRNA is structurally more stable than a DNA-RNA hybrid. This stability allows the hybrid to withstand the stringent washing conditions necessary to remove mismatched or weakly bound probes, thereby enhancing the specificity and clarity of the signal.

- Probe Length and Labeling Density: Riboprobes are typically long (several hundred base pairs), enabling the incorporation of multiple labeled nucleotides per molecule [3]. This high labeling density creates a strong signal that is readily detectable. While very long probes might require hydrolysis for better tissue penetration, a target size of 300 bp is often optimal for balancing sensitivity and permeability [13].

- Robust Control Strategies: A significant advantage of riboprobes is the straightforward generation of control probes. A "sense" probe, complementary to the antisense riboprobe and identical in sequence to the target mRNA, can be synthesized from the same plasmid. The sense probe should yield no specific signal, providing a critical negative control for non-specific hybridization and background [12].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and key advantages of using riboprobes for detecting mRNA targets.

Detailed Protocol: Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization in Zebrafish Embryos

This protocol is adapted for qualitative chromogenic detection of mRNA in zebrafish embryos using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobes and is compatible with downstream genotyping by PCR [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DIG-labeled Riboprobe | The complementary RNA molecule that binds the target mRNA. | Probes of 300-1200 bp work well. Design for high specificity [14]. |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Fixative that preserves tissue morphology and immobilizes RNA. | Over-fixation can reduce signal; standard is 4% in PBS [13]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that permeabilizes tissues by digesting proteins, allowing probe entry. | Concentration and time must be empirically optimized to balance penetration and tissue integrity [13]. |

| Formamide | A denaturant used in hybridization buffer. | Lowers the effective melting temperature of hybrids, allowing high-stringency hybridization at lower, morphologically-safe temperatures [14]. |

| Dextran Sulfate | A volume-excluding agent that increases probe effective concentration. | Accelerates development and improves contrast but inhibits PCR; omit if genotyping is required [14]. |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | An antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) that binds the DIG hapten. | Enables immunodetection of the hybridized probe. |

| NBT/BCIP | Chromogenic substrate for Alkaline Phosphatase. | Produces an insoluble purple-blue precipitate at the site of target mRNA localization [14]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Day 1: Fixation, Permeabilization, and Pre-hybridization

- Fixation: Dissect and fix tissues (e.g., zebrafish embryos, butterfly pupal wings) in fresh 4% PFA for 2 hours at room temperature. For some tissues, fixation at 4°C for up to 12 hours is acceptable, but shorter times are preferred to avoid over-fixation [13].

- Washing: Wash fixed samples 5 times for 5 minutes each in PBT (1x PBS with 0.1% Tween-20).

- Permeabilization: Incubate samples with Proteinase K (e.g., 3 minutes for fragile butterfly pupal wings [13]; concentration and time must be determined for each tissue type).

- Post-fixation & Washing: Re-fix briefly in 4% PFA for 20 minutes to maintain tissue structure after permeabilization. Wash thoroughly with PBT.

- Pre-hybridization: Gradually transition samples into hybridization buffer (50:50 PBT:Hyb, then 100% Hyb). Pre-hybridize in Hyb buffer for at least 1 hour at 55-60°C [14]. Hybridization Buffer (Hyb) recipe: 50% deionized formamide, 5x SSC, 0.1% Tween-20, 50 µg/ml Heparin, 1 mg/ml Torula RNA [14].

Day 2: Hybridization

- Probe Preparation: Denature the DIG-labeled riboprobe (20-50 ng/µl) at 80°C for 5 minutes and add to fresh, pre-warmed Hyb buffer.

- Hybridization: Replace the pre-hybridization buffer with the probe-containing Hyb buffer. Incubate at 55-60°C for 48 hours. Note: A lower temperature (55-60°C) can yield higher contrast stains compared to 70°C for highly specific probes and is more compatible with subsequent genotyping [14].

Day 4: Post-Hybridization Washes and Antibody Incubation

- Stringency Washes: Remove unbound probe with a series of stringent washes:

- Wash 4 x 5 minutes in pre-warmed (55°C) Hyb buffer.

- Wash 2 x 5 minutes in a 50:50 mixture of Hyb buffer and PBT.

- Wash 4 x 5 minutes in PBT at room temperature.

- Blocking: Incubate samples in Block Buffer (e.g., 10% normal goat serum in PBT) for 1 hour at 4°C to reduce non-specific antibody binding.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate samples with anti-DIG-Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) antibody (e.g., 1:2000 dilution in Block Buffer) overnight at 4°C [13].

Day 5: Chromogenic Detection and Imaging

- Washing: Wash samples extensively to remove unbound antibody (e.g., 3 x 5 min, then 7 x 5 min in PBT).

- Detection Equilibration: Rinse samples 2 times in Detection Buffer (e.g., Alkaline Phosphatase buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% Tween-20).

- Staining: Develop the color reaction by incubating samples in Detection Buffer containing NBT/BCIP. Wrap the container in foil to protect from light and monitor development from 5 minutes up to several hours/overnight.

- Stop Reaction: Once the desired stain intensity is achieved with acceptable background, stop the reaction by rinsing several times in Detection Stop Buffer (e.g., 1x PBS with 1 mM EDTA).

- Imaging and Genotyping: Mount samples and image using transmitted light microscopy. For genotyping, the tissue can be processed for DNA extraction. Critical: Omission of dextran sulfate from the Hyb buffer is essential for successful PCR genotyping after in situ hybridization [14].

Riboprobs remain a powerful tool for developmental biologists investigating gene expression patterns. Their superior sensitivity and the exceptional stability of the RNA-RNA hybrids they form make them the probe of choice for detecting low-abundance transcripts or when the highest resolution spatial data is required. The provided protocol and comparative data offer a clear roadmap for researchers to implement this robust technique, enabling precise mRNA localization in complex tissues and contributing to a deeper understanding of developmental processes.

The selection of an appropriate label for in situ hybridization (ISH) is a critical decision that directly influences the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability of gene expression analysis in developmental biology research. This technical choice becomes particularly significant when investigating the precise spatial and temporal patterns of gene expression that orchestrate embryonic development. While radioactive isotopes dominated early ISH methodologies, non-isotopic haptens—primarily digoxigenin and biotin—and direct fluorescent tags have become the mainstay of modern protocols due to their improved safety, stability, and resolution [15] [16].

Each labeling system possesses distinct characteristics that make it suitable for specific experimental scenarios. The optimal choice depends on multiple factors, including the target abundance, tissue type, detection method, and required sensitivity. This application note provides a structured comparison of digoxigenin, biotin, and fluorescent tags, and details protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the ideal labeling strategy for their developmental studies.

Label Comparison: Properties and Applications

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary labeling systems used in modern ISH protocols.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Non-Isotopic ISH Labeling Systems

| Label Type | Sensitivity & Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Cases in Developmental Biology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin | High sensitivity; comparable to biotin in multi-step protocols [17]. | Very low background; no endogenous interference in animal tissues [18] [15]. | Detection requires an anti-digoxigenin antibody [15]. | Gold standard for embryonic tissue sections; detecting low-abundance transcripts; multi-color FISH with other haptens [19]. |

| Biotin | High in multi-step detection systems; lower in single-step protocols [17]. | Well-established; less expensive; strong affinity for streptavidin/avidin [15]. | Endogenous biotin in tissues can cause false positives [18] [15]. | Experiments in tissues low in endogenous biotin; cost-sensitive high-throughput screens. |

| Fluorescent Tags | Varies with fluorophore and instrumentation. | Direct detection enables multi-target visualization; high spatial resolution [19] [20]. | Can be expensive; signal may photobleach; potential for autofluorescence. | Multi-color karyotyping [20]; simultaneous detection of mRNA & rRNA [16]; live imaging applications. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Two-Color catFISH with Digoxigenin and Biotin

This protocol, adapted for developmental biology applications, allows for the simultaneous detection of two different mRNA populations or transcriptional states within the same embryonic tissue sample, such as distinguishing nascent nuclear transcripts from mature cytoplasmic mRNA [19].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials and Reagents:

- pSPT18-c-fos_exon & intron plasmids: To generate template DNA for in vitro transcription of exon- and intron-specific RNA probes [19].

- DIG- and Biotin-Labeled UTP: For incorporation into RNA probes during in vitro transcription [19].

- Anti-Digoxigenin Antibody: Conjugated to a fluorophore (e.g., FITC, Rhodamine) [19].

- Streptavidin: Conjugated to a different fluorophore (e.g., Cy3, Cy5) [19] [20].

- Hybridization Buffer: Containing formamide, dextran sulfate, and salts to facilitate specific hybridization [16].

- RNAse-free reagents and equipment: Including water, buffers, and plasticware to preserve RNA integrity [16].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Probe Synthesis: Linearize plasmid DNA containing the gene of interest (e.g., c-fos). Perform in vitro transcription using T7/SP6 RNA polymerase in the presence of either DIG-11-UTP or Biotin-16-UTP to generate labeled, strand-specific RNA probes. Purify probes and quantify labeling efficiency [19].

- Tissue Preparation: Fix embryonic tissues promptly with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to preserve RNA and morphology. For paraffin-embedded tissues, follow standard processing protocols. Permeabilize with a detergent (e.g., Triton X-100) and/or proteinase K to facilitate probe access [19] [16].

- Hybridization: Apply the hybridization buffer containing a mixture of the DIG-labeled (exonic) and biotin-labeled (intronic) probes to the tissue sections. Denature probe and target DNA/RNA if necessary, and incubate in a humidified chamber overnight at an optimized temperature (e.g., 55-65°C) [19].

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Perform stringent washes with saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer to remove non-specifically bound probe. The stringency is controlled by temperature and salt concentration [16].

- Simultaneous Immunofluorescence Detection: Incubate the tissue with a blocking solution to minimize non-specific antibody binding. Then, apply a cocktail containing the anti-digoxigenin antibody (with fluorophore A) and streptavidin (with fluorophore B). Wash thoroughly to remove unbound detection reagents [19].

- Mounting and Imaging: Mount the slides with an anti-fade mounting medium and visualize using a fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filter sets for the two fluorophores [19].

Optimized ISH for Embryonic Tissues

This general protocol is optimized for detecting gene expression patterns in early developing embryos, such as in zebrafish or paradise fish, and is highly effective for digoxigenin-labeled probes [21].

Workflow Diagram:

Key Considerations for Development:

- Fixation: Over-fixation can mask target mRNA and reduce signal, while under-fixation compromises tissue integrity. Optimize PFA concentration and fixation time for specific embryonic stages [21] [16].

- Permeabilization: The proteinase K concentration and incubation time are critical. Too little results in poor probe penetration; too much destroys tissue morphology. Titration is essential [21].

- Hybridization Stringency: Adjust the hybridization temperature and post-hybridization wash stringency based on the probe's GC content and required specificity to minimize cross-hybridization with related genes [16].

- Signal Amplification: For low-abundance targets, consider using Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) to dramatically increase sensitivity. This method uses horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to deposit multiple fluorophore- or hapten-labeled tyramide molecules at the probe site [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for ISH Protocol Development

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Protocol-Specific Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin-11-UTP | A hapten-labeled nucleotide incorporated into RNA or DNA probes via in vitro transcription or nick translation [19] [15]. | Preferred for animal tissues to avoid endogenous biotin background [18]. |

| Biotin-16-UTP | A hapten-labeled nucleotide incorporated into nucleic acid probes [19] [15]. | Check tissue for endogenous biotin; use extra blocking if necessary [17]. |

| Anti-Digoxigenin Antibody | Primary antibody that binds specifically to the digoxigenin hapten. Conjugated to AP, HRP, or fluorophores [19] [15]. | Key for signal generation. Multi-step detection enhances sensitivity [17]. |

| Streptavidin | A protein with extremely high affinity for biotin. Conjugated to enzymes or fluorophores [15] [20]. | Forms the core of biotinylated probe detection systems. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that digests proteins and increases tissue permeability for probe access [19] [16]. | Concentration and time must be carefully optimized for each tissue type and fixation protocol. |

| Hybridization Buffer | A solution that creates optimal conditions for specific annealing of the probe to its target [16]. | Typically contains formamide to control stringency, and dextran sulfate to increase effective probe concentration. |

| NBT/BCIP | A chromogenic substrate for Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). Produces a purple-blue precipitate at the probe binding site [19]. | Provides a permanent stain for bright-field microscopy. |

The strategic selection between digoxigenin, biotin, and fluorescent tags is fundamental to successful ISH experimentation in developmental biology. Digoxigenin emerges as the most versatile and robust label for most applications, particularly due to its absence in animal tissues, which guarantees minimal background and high-specificity detection. Biotin remains a powerful, cost-effective alternative, provided its susceptibility to endogenous background is adequately managed. Finally, direct fluorescent tags are indispensable for multi-analyte detection and high-resolution imaging, despite their cost and susceptibility to photobleaching. By leveraging the comparative data and optimized protocols detailed in this application note, researchers can make informed decisions and implement reliable ISH assays to decode the complex language of gene expression during development.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a cornerstone technique in developmental biology, enabling the spatial visualization of gene transcripts within tissues and whole embryos. This capability is crucial for understanding gene function, tissue patterning, and the evolutionary conservation of developmental programs across species. While the fundamental principle of ISH—complementary base-pair binding of labeled nucleic acid probes to target sequences—remains consistent [22] [23], its successful application varies significantly between model organisms due to differences in embryology, tissue permeability, and fixation requirements. Research in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) particularly benefits from cross-species comparisons, which rely on optimized and tailored ISH protocols to generate comparable data.

This application note details specialized ISH methodologies for key model organisms—zebrafish, paradise fish, and mouse—framed within the context of a broader thesis on developmental biology research. We provide detailed protocols, a quantitative summary of target genes and their expression, and a visual guide to critical signaling pathways, serving as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Organism-Specific Protocol Optimizations

Zebrafish (Danio rerio)

Zebrafish is a well-established vertebrate model characterized by external fertilization, high fecundity, and embryonic transparency. A standard chromogenic whole-mount ISH protocol for zebrafish involves using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobes detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies and NBT/BCIP chromogenic substrates [24]. A critical consideration for genotyping is the omission of dextran sulfate from the hybridization buffer, as it inhibits PCR, though this may sacrifice some signal contrast [24]. The standard hybridization temperature of 70°C ensures high stringency, but for specific probes with high complementarity, lowering the temperature to 55-60°C can yield faster-developing, higher-contrast stains [24].

For advanced, quantitative applications, a whole-mount single-molecule FISH (smFISH) protocol has been established. This method is superior for quantifying transcript levels at single-cell resolution. A key modification from cell culture protocols is the inclusion of a methanol pretreatment step, which was found to be absolutely critical for achieving a good signal-to-noise ratio and distinguishable dot-like signals in whole-mount embryos [25]. This protocol can detect transcripts as short as 720 bases and has been successfully used for both ubiquitously expressed genes (e.g., gapdh, sdha) and cell-type-specific genes (e.g., olig2, ntla) [25].

Paradise Fish (Macropodus opercularis)

The paradise fish, an obligate air-breathing species, is an emerging model for behavioral genetics and evolutionary studies. Initial attempts to apply the standard zebrafish ISH protocol to paradise fish embryos failed, underscoring the necessity for optimization, though the specific modifications are not detailed in the provided search results [21] [7]. The optimized protocol has been successfully used to compare the expression of several conserved developmental genes, such as chordin (chd), goosecoid (gsc), and myogenic differentiation 1 (myod1), with zebrafish [21] [7]. Furthermore, paradise fish share many practical advantages with zebrafish, including high fecundity, external fertilization, and transparent embryos, making them a compatible complementary model system [7].

Mouse (Mus musculus)

Mouse models require specialized ISH protocols for thicker tissues and organs. For the developing mouse retina, a whole-mount smFISH protocol has been developed to detect individual mRNAs in vascular endothelial cells [26]. This protocol presents solutions for challenges such as adequate tissue permeabilization and co-detection of mRNA and protein, which are common hurdles in mammalian tissue analysis. The ability to perform smFISH on a whole-mount tissue like the retina preserves spatial context and avoids the labor-intensive process of generating and analyzing hundreds of histological sections [25] [26].

The table below summarizes key developmental genes and the effects of signaling pathway perturbations, as investigated in the cited studies, providing a quantitative reference for cross-species experimental design.

Table 1: Summary of Gene Expression and Pathway Modulation in Model Organisms

| Gene / Pathway | Function in Development | Expression / Effect in Zebrafish | Expression / Effect in Paradise Fish | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chordin (chd) | Dorsalizing factor, neural induction | Established expression pattern | Conserved expression pattern confirmed | [21] [7] |

| myogenic differentiation 1 (myod1) | Skeletal muscle determination | Established expression pattern | Conserved expression pattern confirmed | [21] [7] |

| egfp (transgene) | Reporter gene | ~139 transcripts/cell (hemizygous); ~214 transcripts/cell (homozygous) | Information not available | [25] |

| BMP Pathway Inhibition | Dorsal-ventral patterning | Dorsalized phenotype | Dorsalized phenotype | [7] |

| Shh Pathway Inhibition | CNS patterning, pancreas development | Curved trunk, cyclopia, reduced myoseptum | Phenotypic defects observed | [7] |

| Wnt Pathway Inhibition | Axis formation, neural patterning | Patterning defects, reduced telencephalon, lack of eyes | Patterning defects observed | [7] |

| Notch Pathway Inhibition | Somitogenesis, neurogenesis | Somitogenesis defects, curved body, neural patterning errors | Somitogenesis defects observed | [7] |

Table 2: smFISH Performance for Endogenous Genes in Zebrafish Embryos

| Gene Name | Function / Expression Domain | Transcript Length (bases) | Detectable with smFISH | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| olig2 | Motor neuron progenitors | Information not available | Yes | [25] |

| ntla | Notochord | Information not available | Yes (fits logistic distribution) | [25] |

| fli1a | Vascular endothelium | Information not available | Yes (<50 copies/cell) | [25] |

| fbp1b | Liver | Information not available | Yes | [25] |

| gapdh | Ubiquitous | 1331 | Yes | [25] |

Visualizing Key Signaling Pathways in Development

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways discussed in this note, their agonists/antagonists, and their primary roles during early embryonic development.

Experimental Workflow for Protocol Optimization

The process of adapting an ISH protocol from a established model like zebrafish to a new species like paradise fish involves systematic troubleshooting. The following workflow outlines the key steps and decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation and troubleshooting of ISH protocols depend on a core set of reagents. The table below details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Situ Hybridization

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DIG-Labeled Riboprobes | Complementary RNA probes for target mRNA detection; DIG hapten is detected by antibodies. | Probe length typically 300-3200 bp; specificity is critical [24]. |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Conjugated antibody binds DIG hapten; alkaline phosphatase (AP) enzyme produces colorimetric signal. | Allows chromogenic detection with NBT/BCIP [24] [23]. |

| NBT/BCIP | Chromogenic substrate for AP; yields an insoluble purple-blue precipitate at probe sites. | Standard for chromogenic ISH; compatible with brightfield microscopy [24]. |

| Formamide | Organic solvent in hybridization buffer; lowers melting temperature of RNA duplexes. | Allows for lower, less destructive hybridization temperatures while maintaining stringency [24] [22]. |

| Dextran Sulfate | Agent in hybridization buffer; increases effective probe concentration by excluding volume. | Accelerates development and enhances contrast, but inhibits PCR for genotyping [24]. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme; digests proteins surrounding target nucleic acids in fixed tissues. | Improves probe accessibility and hybridization signal; requires careful titration [23]. |

| Small Molecule Agonists/Antagonists | Pharmacologically modulates specific signaling pathways (e.g., Dorsomorphin for BMP). | Used to study gene function and pathway conservation; dissolved in embryo medium [7]. |

The tailored application of ISH techniques, from classic chromogenic methods to quantitative smFISH, is fundamental to advancing our understanding of developmental biology across model organisms. The protocols and data summarized here provide a framework for researchers to investigate gene expression and evolutionary conservation in zebrafish, mouse, and emerging models like the paradise fish. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of these tools, particularly for multiplexing and single-cell analysis, will further illuminate the genetic architecture of development and disease.

Step-by-Step ISH Protocols: From Sample Preparation to Signal Detection

In developmental biology research, the accurate visualization of gene expression patterns via in situ hybridization (ISH) is fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of tissue fixation and RNA preservation. The integrity of RNA within tissue samples dictates the sensitivity, specificity, and overall success of subsequent molecular analyses. Effective preservation maintains the spatial and temporal expression patterns of specific nucleic acid sequences, providing crucial insights into where and when genes are active during development [1]. This protocol outlines standardized methodologies for tissue handling, fixation, and preservation to maintain high RNA quality, ensuring reliable and reproducible results in developmental studies.

Sample Collection and Initial Handling

The immediate post-collection period is critical for preserving RNA integrity. Rapid action is required to inhibit ubiquitous RNase enzymes and prevent transcriptional changes that occur post-collection.

- Minimize Ischemia Time: Begin fixation or preservation immediately after tissue dissection to prevent degradation from warm ischemia.

- Tissue Size Standardization: For uniform fixation, dissect tissues into small, consistent fragments. For cryopreservation without preservatives, aliquot sizes of ≤ 30 mg are recommended for optimal RNA extraction, whereas larger aliquots (250-300 mg) show significantly reduced RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) [27].

- Preservation Medium: For short-term transport, submerge tissues in a cold, RNA-stabilizing solution like DMEM to maintain tissue viability and slow degradation [28].

Fixation Protocols

Fixation preserves tissue morphology and immobilizes nucleic acids. The choice of fixative and protocol parameters significantly impacts RNA integrity and accessibility for ISH probes.

Formaldehyde Fixation

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples are a mainstay for histology and ISH, allowing long-term storage at room temperature [1] [29].

- Fixative Preparation: Prepare a 4% formaldehyde solution in 1X Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). For better tissue penetration, add a surfactant like Silwet-L77 (0.0001% v/v) [30].

- Fixation Duration: Standard fixation time is 12-24 hours at 4°C with gentle rocking [30]. Prolonged fixation (e.g., 72 hours) can lead to increased RNA fragmentation and should be avoided [29].

- Vacuum Infiltration: For dense or complex tissues, apply vacuum infiltration (e.g., -27 inHg for 1 minute, repeated until tissue sinks) to ensure complete fixative penetration [30].

- Innovative Method - Sheet-like Fixation: A study on lung specimens demonstrated that a "sheet-like fixation" method, which reduces fixation time by increasing surface area, resulted in significantly higher RNA quality (median DV200 value of 47.5%) compared to conventional fixation (median DV200 of 21%) [31].

Table 1: Impact of Formalin Fixation Duration on RNA Quality

| Fixation Method | RNA Quality Metric (DV200) | Suitability for Multiplex Genetic Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Sheet-like Fixation | Median 47.5% (IQR: 40.3-51.5) | 100% success rate [31] |

| Conventional 24-hour Fixation | Median 21% (IQR: 5.3-29.8) | 95% success rate [31] |

| Conventional 72-hour Fixation | Significantly lower quality than 24-hour [29] | Not Recommended |

Alternative Preservation Methods for RNA Analysis

For applications requiring high-quality RNA extraction, such as RNA-seq, chemical stabilization is preferred.

- RNAlater Storage: This solution rapidly penetrates tissues to stabilize and protect RNA. It demonstrates statistically superior performance in RNA yield, purity, and integrity compared to snap-freezing alone. In dental pulp tissue, RNAlater provided an 11.5-fold higher RNA yield than snap-freezing and achieved optimal RNA quality in 75% of samples [28].

- Snap-Freezing in Liquid Nitrogen: This method instantly halts all enzymatic activity. For optimal results, rapidly wash tissue fragments in sterile DMEM, section into pieces < 3 mm, and submerge in liquid nitrogen. Store samples at -80°C or in vapor-phase liquid nitrogen to prevent freeze-thaw cycles [28] [27].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of RNA Preservation Methods

| Preservation Method | Relative RNA Yield (ng/μL) | Mean RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Storage | 4,425.92 ± 2,299.78 [28] | 6.0 ± 2.07 [28] | Superior yield & integrity; easy clinical use [28] |

| Snap-Freezing | 384.25 ± 160.82 [28] | 3.34 ± 2.87 [28] | Instantly halts enzymatic activity [28] |

| RNAiso Plus Reagent | ~2,400 (estimated) [28] | Not Specified | Combined preservation and lysis [28] |

Tissue Processing and Storage

Post-fixation processing must be performed carefully to avoid RNA degradation.

- Dehydration and Clearing: After formaldehyde fixation, dehydrate tissues through a graded ethanol series (e.g., 50%, 70%, 85%, 95%, 100%) [30]. Subsequently, clear tissues using a reagent like Citrisolv (d-Limonene) or xylene to prepare for paraffin infiltration [30].

- Paraffin Embedding: Infiltrate tissues with molten paraffin wax using a vacuum oven at 60°C. Embed tissues in molds for sectioning [30].

- Section Storage: For FFPE sections, do not store slides dry at room temperature. Instead, store them in 100% ethanol at -20°C or in a sealed plastic box at -80°C to preserve RNA integrity for several years [1].

- Thawing Cryopreserved Tissues: For tissues frozen without preservatives, thawing conditions are critical.

Workflow for Tissue Preservation and Fixation

The following diagram summarizes the critical decision points and steps in the tissue preservation and fixation workflow for RNA integrity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RNA Preservation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Chemical stabilizer that rapidly penetrates tissue to protect RNA from degradation. | Superior for maintaining RNA yield and integrity; ideal for clinical settings [28]. |

| 4% Formaldehyde in HBSS | Cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue architecture and immobilizes biomolecules. | Essential for FFPE samples; add Silwet-L77 for improved penetration [30]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Cryogenic preservative that instantly halts all biochemical activity. | Gold standard for snap-freezing; requires specialized handling and storage [28] [27]. |

| Proteinase K | Protease enzyme used to digest proteins and permeabilize tissue sections. | Critical for ISH antigen retrieval; requires concentration and time optimization [1]. |

| Diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) Water | RNase-inactivated water used to prepare solutions and prevent RNA degradation. | Essential for all steps post-tissue collection to inactivate RNases [29]. |

| RNAscope Hydrogen Peroxide & Protease Plus | Commercial reagents for blocking endogenous peroxidases and controlling tissue permeability. | Used in advanced branched DNA ISH assays for high-sensitivity detection [30]. |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with standardized protocols, optimization for specific tissues or experimental conditions is often necessary.

- Antigen Retrieval Optimization: For FFPE-ISH, a proteinase K titration (e.g., 20 µg/mL for 10-20 min at 37°C) is crucial. Insufficient digestion reduces hybridization signal, while over-digestion damages tissue morphology [1].

- Handling Degraded RNA from FFPE: While RNA from FFPE samples is often fragmented, RT-qPCR can still be successfully performed because it can amplify short mRNA fragments [29].

- Validating Preservation Methods: Before proceeding with large studies, validate your chosen method by checking RNA quality using multiple metrics: Nanodrop for purity (A260/A280 ratio), Qubit for accurate quantification, and Bioanalyzer for integrity (RIN or DV200) [28] [29].

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in developmental biology research, enabling the spatial visualization of gene expression patterns directly within tissues and whole embryos. The specificity and sensitivity of this technique are fundamentally dependent on the quality of the nucleic acid probes used. Among the various labeling methods, digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobes have emerged as the gold standard for non-radioactive detection due to their high sensitivity, low background, and excellent stability [32] [14]. These antisense RNA probes are synthesized via in vitro transcription and hybridize specifically to target mRNA sequences, allowing researchers to map gene expression with cellular resolution during critical developmental stages.

The application of DIG-labeled riboprobes has been instrumental in characterizing gene function across model organisms. For instance, optimized ISH protocols using these probes have recently been applied to compare the expression of conserved developmental genes—such as chordin (chd), goosecoid (gsc), and myogenic differentiation 1 (myod1)—in zebrafish and paradise fish embryos, providing insights into the evolutionary conservation of developmental programs [7]. This protocol detail will outline the comprehensive process for generating high-quality, specific DIG-labeled riboprobes, framed within the context of a broader thesis on ISH protocol development for developmental biology research.

Probe Design Fundamentals

Sequence Selection and Specificity

The initial and most critical step in riboprobe synthesis is the careful design of the probe sequence. A well-designed probe ensures high specificity and sensitivity while minimizing background noise.

- Target Region: Select a unique region of the target mRNA that lacks significant homology with other genes. Bioinformatics tools like BLAST should be used to verify sequence uniqueness and avoid cross-hybridization [33].

- Probe Length: Optimal riboprobe length typically ranges from 250 to 1,500 bases, with probes of approximately 800 bases often demonstrating the highest sensitivity and specificity [1]. Longer probes within this range generally exhibit higher hybridization rates and form more thermally stable hybrids with the target mRNA [14].

- Sequence Composition: Maintain balanced GC content and avoid self-complementary regions or hairpin structures that could interfere with hybridization efficiency [34]. The probe must be maximally complementary to the target sequence, as even >5% base pair mismatches can significantly reduce hybridization stability and lead to signal loss during stringent washes [1].

Template Design and Vector Considerations

Riboprobes are synthesized from DNA templates that must include specific promoter elements for RNA polymerase binding.

- Vector Selection: Clone the target sequence into a plasmid vector containing opposable RNA polymerase promoters (e.g., T7, T3, or SP6) on either side of the insertion site. This arrangement enables the synthesis of both antisense (probe) and sense (negative control) RNAs from the same template [14] [1].

- Template Linearization: Before in vitro transcription, circular plasmid templates must be linearized using appropriate restriction enzymes that cleave downstream of the insert. This ensures transcription of discrete RNA fragments of defined length rather than long concatenated transcripts [35] [14].

- PCR-Generated Templates: As a faster alternative to plasmid-based templates, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to generate templates with incorporated promoter sequences. This method is particularly valuable for rapid assessment of gene expression and has been successfully applied in neuroscience research [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Template Preparation Methods for Riboprobe Synthesis

| Method | Procedure | Time Requirement | Key Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid-Based Templates | Restriction digest of plasmid DNA, followed by purification via phenol-chloroform extraction or column purification [35] | Several days | Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) in model organisms [35] [7] | High yield, stable template source, suitable for repeated use |

| PCR-Generated Templates | Two-step PCR amplification to incorporate RNA polymerase promoter sequences and target DNA [34] | 1-2 days | Rapid gene mapping, colocalization studies with immunohistochemistry [34] | Faster alternative, no cloning required, suitable for high-throughput applications |

Probe Synthesis Methods

In Vitro Transcription and DIG Labeling

The synthesis of DIG-labeled riboprobes involves the enzymatic incorporation of DIG-modified nucleotides during in vitro transcription.

- Reaction Components: A standard transcription reaction includes linearized DNA template, RNA polymerase (T7, T3, or SP6), RNase inhibitor, transcription buffer, nucleotides (ATP, CTP, GTP), and DIG-labeled UTP (DIG-11-UTP) [32] [14]. The DIG molecule is covalently linked to the UTP base, allowing its incorporation into the nascent RNA strand.

- Transcription Conditions: Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 2 hours to allow for efficient RNA synthesis. The optimal incubation time may vary depending on the specific RNA polymerase and template used [14].

- Template Removal: After transcription, degrade the DNA template by adding DNase I (RNase-free) and incubating for 15-30 minutes at 37°C. This step prevents potential competition between the template DNA and target mRNA during hybridization [14].

Probe Purification and Quality Assessment

Following synthesis, purification is essential to remove unincorporated nucleotides, enzymes, and degraded template DNA that could interfere with hybridization.

- Purification Methods: Common approaches include phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation [35] or purification using commercial cleanup kits (e.g., RNeasy MinElute, Qiagen) [14]. Column-based methods generally provide more consistent recovery of full-length probes.

- Quality Control: Assess probe quality and concentration using spectrophotometry and gel electrophoresis. Intact RNA should appear as a discrete band on a denaturing agarose gel, with minimal smearing indicating minimal degradation [14]. Aliquots of the purified probe should be stored at -80°C to prevent RNase-mediated degradation.

Table 2: Critical Reagents for DIG-Labeled Riboprobe Synthesis and Their Functions

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DIG-11-UTP | Labeled nucleotide incorporated during in vitro transcription | Serves as hapten for antibody detection; concentration must be optimized for efficient incorporation [32] [14] |

| RNA Polymerases (T7, T3, SP6) | Enzymatic synthesis of RNA from DNA template | High specificity for respective promoter sequences; selection depends on vector system [14] |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA transcripts from degradation | Essential for maintaining RNA integrity during synthesis and storage [14] |

| Proteinase K | Tissue digestion for probe accessibility | Concentration and incubation time require optimization for different tissue types [1] |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Immunological detection of hybridized probes | Conjugated to alkaline phosphatase for colorimetric (NBT/BCIP) detection [32] [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Generating Plasmid-Derived DIG-Labeled Riboprobes

Template Preparation

- Restriction Digest: Digest 5-10 µg of plasmid DNA containing the target sequence with the appropriate restriction enzyme to linearize the template. Use enzymes that generate 5' overhangs or blunt ends, as 3' overhangs can facilitate aberrant transcription initiation [35] [14].

- Purification: Purify the linearized DNA by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation or using a PCR purification kit. Verify complete linearization by running a small aliquot on an agarose gel [14].

- Quantification: Measure DNA concentration using a spectrophotometer and adjust to a working concentration of 0.2-0.5 µg/µL.

In Vitro Transcription

- Reaction Setup: Assemble the transcription reaction at room temperature in the following order:

- 4.0 µL Transcription buffer (5X)

- 2.0 µL DIG RNA labeling mix (10X)

- 1.0 µg Linearized template DNA

- 2.0 µL RNA polymerase (T7, T3, or SP6)

- 1.0 µL RNase inhibitor

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL total volume [14]

- Incubation: Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 2 hours.

- DNase Treatment: Add 2 units of DNase I (RNase-free) and incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes to remove the template DNA.

- Termination: Add 2.0 µL of 0.2 M EDTA (pH 8.0) to stop the reaction.

Probe Purification and Quantification

- Purification: Purify the transcribed RNA using a commercial RNA cleanup kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, or by ethanol precipitation [14].

- Quantification: Measure RNA concentration using a spectrophotometer. Typical yields range from 10-20 µg of labeled RNA per standard reaction.

- Quality Assessment: Analyze 100-200 ng of the purified probe on a denaturing agarose gel alongside an RNA molecular weight marker. A sharp, discrete band should be visible with minimal smearing.

- Storage: Aliquot the probe and store at -80°C to prevent freeze-thaw cycles and RNase degradation.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from probe design to synthesis:

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with careful execution, riboprobe synthesis can encounter challenges that affect downstream applications. The following table addresses common issues and provides evidence-based solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for DIG-Labeled Riboprobe Synthesis

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Transcription Yield | Incomplete template linearization, degraded nucleotides, suboptimal enzyme activity | Verify complete linearization by gel electrophoresis; prepare fresh reaction buffer; ensure proper enzyme storage conditions [14] | Aliquot nucleotides to avoid freeze-thaw cycles; use high-quality restriction enzymes with complete digestion verification |

| High Background in ISH | Non-specific probe binding, incomplete purification, probe degradation | Increase stringency of post-hybridization washes (adjust SSC concentration, temperature); implement pre-absorption with blocking agents [14] [1] | Optimize proteinase K concentration for tissue permeabilization; include dextran sulfate in hybridization buffer (omit if genotyping is required) [14] |

| Weak or No Signal | Insufficient probe labeling, low target abundance, over-fixation of tissues | Increase probe concentration; verify incorporation of DIG-UTP by dot blot; extend development time for chromogenic detection [14] [1] | Test probe sensitivity on positive control tissue; optimize fixation conditions to preserve RNA while maintaining tissue morphology |

| RNA Degradation | RNase contamination, improper storage, repeated freeze-thaw cycles | Use RNase-free reagents and equipment; include RNase inhibitors during synthesis; store in single-use aliquots at -80°C [14] [1] | Designate RNase-free work area; use barrier tips and gloves; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by creating single-use aliquots |

Advanced Applications in Developmental Biology

The versatility of DIG-labeled riboprobes enables their application in sophisticated experimental designs that extend beyond basic gene expression mapping.

- Multiple Transcript Detection: Researchers can simultaneously visualize the expression of two or more genes by using riboprobes labeled with different haptens (e.g., DIG and fluorescein) in combination with specific antibodies conjugated to distinct enzymes [14]. This approach requires sequential hybridization and detection steps with careful optimization to prevent cross-reactivity.

- Combination with Immunohistochemistry: Riboprobe-based ISH can be effectively combined with immunohistochemistry (IHC) to correlate mRNA localization with protein expression in the same sample. This combined approach has proven valuable in neuroscience research for identifying neuronal subtypes based on both transcript and protein markers [34].

- Genotype-Phenotype Correlation: For mutant analysis in developmental studies, the ISH protocol can be modified to facilitate post-hybridization genotyping. Omission of dextran sulfate from the hybridization buffer preserves PCR compatibility, enabling correlation of expression patterns with genotype after photographic documentation [14].

The generation of specific DIG-labeled riboprobes remains an essential methodology in developmental biology research. Careful attention to probe design, template preparation, and synthesis conditions directly influences experimental success in mapping gene expression patterns. The protocols described herein provide a comprehensive framework for producing high-quality riboprobes suitable for a wide range of applications, from basic gene expression analysis to sophisticated multiplexing approaches. As spatial transcriptomics continues to evolve, the fundamental principles of probe design and hybridization optimization detailed in this protocol will continue to inform the development of next-generation in situ hybridization methodologies for developmental studies.

In the field of developmental biology research, in situ hybridization (ISH) stands as a cornerstone technique for visualizing spatial and temporal gene expression patterns, fundamentally supporting the "seeing is believing" paradigm in molecular studies [36]. The core principle of ISH relies on the thermodynamic propensity of two complementary strands of nucleic acids to anneal and form a stable duplex, a process known as hybridization [3]. Within this process, the mastery of hybridization conditions—specifically temperature, stringency, and buffer composition—is paramount to achieving highly specific results with minimal background. These parameters collectively govern the success of detecting target messenger RNA transcripts in complex samples, from whole-mount embryos to tissue sections [3] [36]. As model organisms like zebrafish, Xenopus, and paradise fish continue to illuminate the conserved programs of embryonic development and signaling pathways, optimized and reliable ISH protocols are indispensable for validating high-throughput sequencing data and providing crucial functional insights [21] [36]. This application note provides a detailed guide to optimizing these critical hybridization parameters within the context of developmental biology research.

The Critical Parameters of Hybridization

Hybridization specificity, or stringency, is the ultimate determinant of a successful ISH experiment. It ensures that signal generation originates exclusively from the perfect or near-perfect complementarity between the probe and its intended target sequence. Stringency is primarily controlled by three interdependent factors: temperature, the concentration of monovalent cations in the hybridization buffer, and the presence of denaturing agents like formamide [37].