Mastering Limb Development: A Comprehensive Guide to Hox Gene Electroporation in Chick Embryos

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers utilizing electroporation to manipulate Hox gene expression in the chick limb bud, a cornerstone model in developmental biology and regenerative medicine.

Mastering Limb Development: A Comprehensive Guide to Hox Gene Electroporation in Chick Embryos

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers utilizing electroporation to manipulate Hox gene expression in the chick limb bud, a cornerstone model in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. We synthesize current methodologies, from foundational principles of Hox codes that govern limb positioning to advanced, step-by-step electroporation protocols. The content details robust validation techniques for assessing gene manipulation efficacy and explores troubleshooting strategies to overcome common experimental pitfalls. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application and validation, this guide aims to empower scientists to design and execute precise experiments that unravel the mechanisms of limb patterning, with significant implications for understanding congenital disorders and informing therapeutic development.

Decoding the Hox Code: Principles of Axial Patterning and Limb Positioning

The Hox gene family, a subset of homeobox genes, comprises a group of highly conserved transcription factors that are fundamental to establishing the anterior-posterior (A-P) body plan in metazoans [1]. These genes encode proteins that specify the positional identity of regions along the A-P axis during embryonic development, ensuring that the correct anatomical structures form in their appropriate locations [1]. In vertebrates, this family consists of 39 genes organized into four distinct genomic clusters (HOXA, HOXB, HOXC, and HOXD) located on different chromosomes [2]. A defining feature of Hox genes is their spatial collinearity—the order of genes within each cluster corresponds to their sequential expression domains along the A-P axis, with genes at the 3' end of the cluster governing anterior development and those at the 5' end controlling posterior formation [2] [3]. The pivotal role of Hox genes in limb positioning and patterning makes them a prime subject for investigation via targeted electroporation in chick limb bud experiments.

Core Principles of Hox Gene Function

The Hox Code and Transcriptional Regulation

Hox proteins function by binding to specific DNA sequences via a 60-amino-acid homeodomain, enabling them to activate or repress hundreds of downstream target genes [1]. They often form complexes with co-factor proteins such as Extradenticle (Exd) and Homothorax (Hth) to enhance DNA-binding specificity and affinity [4]. The combinatorial expression of different Hox genes, known as the "Hox code," provides a molecular framework for specifying regional identity [5]. Recent studies in chick embryos reveal that this code operates through both permissive and instructive signals; for instance, Hox4/5 genes create a permissive territory for forelimb formation, while Hox6/7 provide instructive cues that precisely determine the final forelimb position [5].

Temporal Dynamics and Cluster Regulation

The precise spatiotemporal expression of Hox genes is critical for their function. Master regulators such as Nr6a1 control the timely progression of Hox expression signatures along the axis, acting as a central coordinator for trunk development [6]. Furthermore, Hox gene clusters have undergone significant evolutionary changes, with teleost fishes experiencing a third round of genome duplication (3R-WGD), resulting in eight Hox clusters, while mammals generally retain the standard four clusters [3]. This evolutionary plasticity underscores the functional importance of these genes in body plan organization.

Quantitative Analysis of Hox Gene Expression

The expression profiles of Hox genes are highly tissue-specific and are frequently disrupted in disease states. A comprehensive analysis of HOX gene expression across multiple cancer types, comparing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) with healthy tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) resource, reveals significant differential expression patterns [2].

Table 1: HOX Gene Differential Expression in Selected Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Total Samples (TCGA+GTEx) | Number of HOX Genes with Altered Expression | Notable Examples of Dysregulated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glioblastoma (GBM) | 173 | 36 | Widespread dysregulation of anterior, central, and posterior HOX genes |

| Esophageal Carcinoma (ESCA) | 468 | ≥13 | Associated with metaplastic precursors like Barrett's esophagus |

| Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LUSC) | 551 | ≥13 | Alterations in central and posterior HOX genes |

| Stomach Adenocarcinoma (STAD) | 626 | ≥13 | HOXD10 downregulation linked to increased proliferation and invasion |

| Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (PAAD) | 350 | ≥13 | Dysregulation of developmental pathways |

Table 2: Functional Classification of Human HOX Genes

| HOX Group | Paralog Members | General Axial Specification Domain | Example Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | HOXA1-3, HOXB1-3, HOXC1-3, HOXD1-3 | Hindbrain, cranial neural crest | Head structure formation, neural patterning |

| Central | HOXA4-8, HOXB4-8, HOXC4-8, HOXD4-8 | Thoracic region, limb buds | Specification of thoracic vertebrae, limb positioning (e.g., Hox4-Hox7) |

| Posterior | HOXA9-13, HOXB9-13, HOXC9-13, HOXD9-13 | Lumbar, sacral, and genital regions | Patterning of posterior trunk structures, urogenital development |

Application Note: Electroporation of Hox Genes in Chick Limb Buds

The chick embryo is a premier model for studying limb development due to its accessibility and the ease of gene manipulation via in ovo electroporation. This technique allows for the precise delivery of genetic constructs into the limb-forming lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) to investigate Hox gene function.

Experimental Workflow for Hox Gene Electroporation

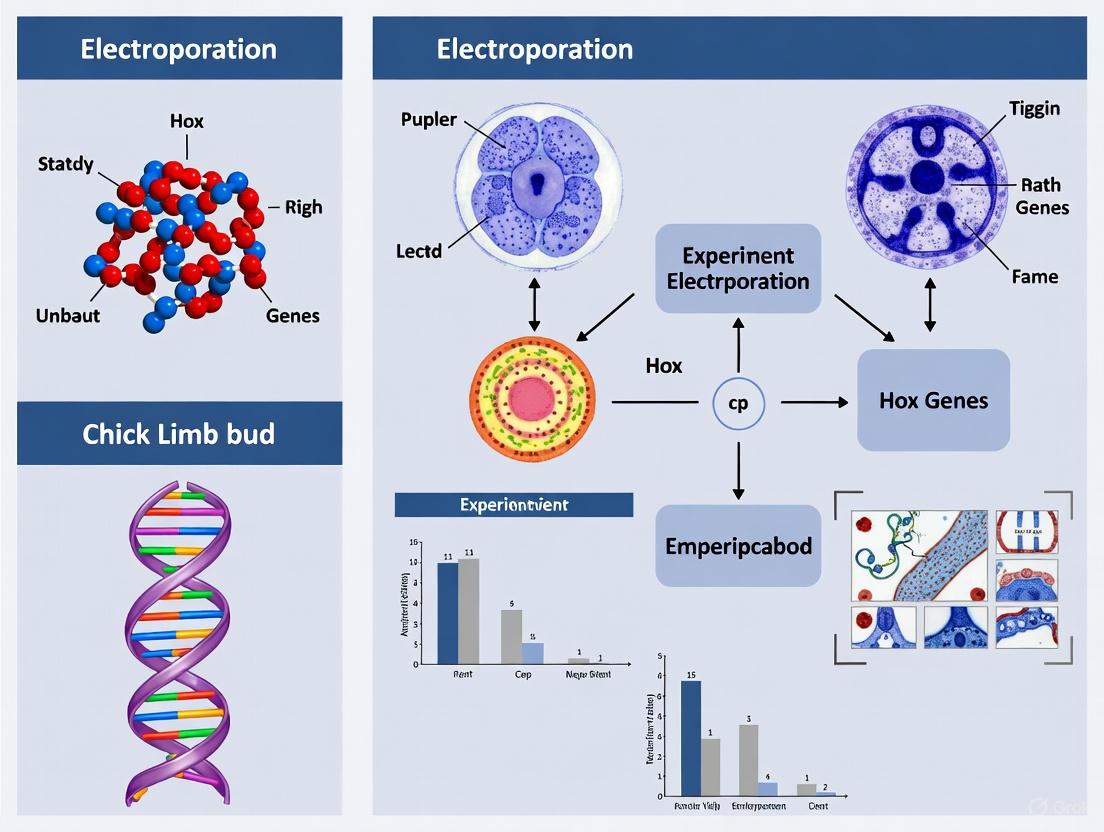

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the experimental workflow for investigating Hox gene function in chick limb development via electroporation:

Detailed Protocol: Gain-of-Function Analysis

Objective: To investigate the effect of anterior Hox gene misexpression on limb positioning and identity.

Materials & Reagents:

- Fertilized chick eggs (incubated to Hamburger-Hamilton [HH] stage 12-14)

- Plasmid DNA: pCAGGS-Hoxa6-IRES-EGFP or similar Hox expression vector [5]

- Fast Green dye (2-5 mg/mL) for visualization

- Electroporator (e.g., BTX ECM 830)

- Platinum or gold electrodes (1 cm diameter paddle electrodes)

- Micropipette puller and microinjection capillaries

Procedure:

- DNA Preparation: Prepare a Hox expression plasmid (e.g., pCAGGS-Hoxa6-IRES-EGFP) at a concentration of 1-2 µg/µL in Tris-EDTA buffer, with 0.1% Fast Green for visualization [5].

- Embryo Preparation: Window the eggshell and visualize the embryo under a stereomicroscope. Identify the forelimb-forming region in the lateral plate mesoderm at the cervical-thoracic boundary.

- Microinjection: Using a pneumatic picopump, inject approximately 0.1-0.5 µL of the DNA solution into the targeted region of the LPM.

- Electroporation: Position paddle electrodes on either side of the embryo. Deliver five 50-ms pulses of 25-30V with 100-ms intervals to drive the DNA into the cells of the LPM [7] [5].

- Post-Procedure Care: Seal the window with laboratory film and re-incubate the eggs at 38°C in a humidified incubator until the desired developmental stage (typically HH24-HH35 for limb analysis).

- Analysis: Visualize electroporated cells by EGFP fluorescence. Assess changes in limb bud position, morphology, and molecular patterning via in situ hybridization for marker genes like Tbx5 (forelimb identity) or Fstl1 (a HoxA13 downstream target) [8] [5].

Protocol: Loss-of-Function Using Dominant-Negative Constructs

Objective: To inhibit the function of specific Hox genes in the limb-forming region.

Procedure: The workflow is similar to the gain-of-function approach, with the key difference being the construct used. Employ dominant-negative (DN) Hox variants that lack the C-terminal portion of the homeodomain. These DN proteins retain the ability to bind co-factors but cannot bind DNA, thereby sequestering essential transcriptional co-activators [5]. For example, electroporate a construct expressing DN-Hoxa5 to assess its requirement in establishing the permissive field for forelimb development [5].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Gene Electroporation Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hox Expression Vectors | Plasmid DNA driving Hox cDNA expression (e.g., pCAGGS, pRCAS). | Gain-of-function studies to assess Hox overexpression effects [5]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Truncated Hox genes that disrupt native Hox/co-factor complex function. | Loss-of-function studies to inhibit specific Hox protein activity in the LPM [5]. |

| EGFP Reporter Vectors | Plasmids encoding Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein, often bicistronic. | Visualization of electroporated cells and lineage tracing [7] [8]. |

| Electroporation Apparatus | System generating controlled electrical pulses (e.g., BTX ECM 830). | Introduction of charged DNA molecules into specific embryonic cells [7]. |

| Limb Bud Marker Assays | In situ hybridization probes for genes like Tbx5, Fstl1, Enpp2. | Molecular analysis of limb identity and patterning following Hox manipulation [8] [5]. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Following electroporation, analysis is critical for drawing meaningful conclusions about Hox gene function. The diagram below illustrates the logical framework for interpreting experimental outcomes related to the Hox code in limb positioning:

Key Analytical Considerations:

- Molecular Phenotyping: A successful Hox gain-of-function experiment in the anterior LPM may result in the ectopic activation of Tbx5, a key determinant of forelimb identity, and the subsequent formation of an ectopic limb bud anterior to the normal limb [5].

- Patterning Defects: Loss-of-function experiments using dominant-negative constructs may result in a posterior shift or complete failure of limb bud initiation, depending on the targeted Hox paralog group [5].

- Downstream Targets: Validate findings by examining the expression of known Hox downstream genes. For example, Hoxa13 regulates targets like Igfbp4 and Fstl1 in the limb interdigital mesenchyme, which can be assessed via in situ hybridization or RT-PCR [8].

The electroporation of Hox genes in the chick limb bud provides a powerful and precise methodological approach to deconstructing the complex regulatory networks that govern A-P patterning and limb positioning. The protocols outlined herein enable functional testing of specific Hox codes and their downstream effectors. The robust, quantitative data generated from such experiments not only advances fundamental developmental biology but also informs our understanding of the mechanisms underlying evolutionary diversity in body plans and the role of Hox gene dysregulation in human disease and congenital disorders.

In vertebrate development, the precise positioning of limbs along the anterior-posterior axis is a fundamental patterning event governed by the combinatorial expression of Hox genes. Recent research has elucidated that specific Hox paralog groups provide distinct signaling cues that collectively determine limb formation sites. This application note examines the mechanistic roles of Hox4/5 (permissive signals) and Hox6/7 (instructive signals) in establishing the forelimb formation field within the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) of chicken embryos, with particular emphasis on experimental approaches utilizing electroporation-based techniques to manipulate Hox gene function.

The conceptual framework of permissive versus instructive signaling represents a significant advance in understanding how Hox genes orchestrate limb positioning. Permissive signals establish a permissive field where limb formation can potentially occur, while instructive signals actively initiate the limb developmental program within this defined territory [5]. This hierarchical regulatory logic ensures precise limb positioning across vertebrate species despite variations in cervical vertebra number.

Key Findings: Quantitative Data on Hox Gene Functions

Table 1: Functional Properties of Hox Paralogs in Forelimb Positioning

| Hox Paralog Group | Signal Type | Expression Domain | Functional Role | Genetic Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hox4/5 | Permissive | Throughout neck region LPM | Establishes permissive field for forelimb formation; necessary but insufficient for limb initiation | Activates Tbx5 expression; required for limb competence |

| Hox6/7 | Instructive | Restricted domain at cervical-thoracic boundary | Determines final forelimb position; sufficient to reprogram neck LPM to form ectopic limbs | Directly regulates Tbx5 via specific enhancer elements |

| Hox9+ | Repressive | Caudal to forelimb field | Suppresses forelimb program; limits Tbx5 expression posteriorly | Antagonizes Hox4/5 and Hox6/7 functions |

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes of Hox Manipulation in Chick Embryos

| Experimental Condition | Tbx5 Expression | Limb Bud Formation | Positional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Wild-type) | Normal at brachial level | Normal forelimb at cervical-thoracic boundary | Standard limb positioning |

| Hox4/5 Dominant-Negative | Absent or severely reduced | Forelimb initiation failed | No limb formation |

| Hox6/7 Dominant-Negative | Reduced or displaced | Diminished or misshapen limb bud | Altered limb position |

| Hox6/7 Misexpression | Ectopic activation in neck LPM | Additional limb buds anterior to normal position | Anterior limb duplication |

Experimental Protocols: Electroporation-Based Functional Analysis

Plasmid Construct Preparation for Hox Gene Manipulation

A. Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs:

- Generate truncated Hoxa4, Hoxa5, Hoxa6, or Hoxa7 variants lacking C-terminal portion of homeodomain

- Clone into expression vector with IRES-EGFP reporter (e.g., pCIG vector)

- Verify protein expression and DNA binding deficiency via EMSA [5] [9]

B. Gain-of-Function Hox Constructs:

- Clone full-length Hoxc6 or Hoxc7 cDNA into electroporation vectors

- Include nuclear localization signals and flag tags for detection

- Confirm transcriptional activity via luciferase reporter assays with Tbx5 regulatory elements [9]

Chick Embryo Electroporation for LPM Targeting

Day 1: Embryo Preparation and Electroporation

- Incubate fertilized chicken eggs to Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 12 (~45-49 hours) [5]

- Window eggshell and visualize embryo using Indian ink injection beneath embryo

- Inject ~0.5-1 μL plasmid DNA (1 μg/μL concentration with Fast Green tracer) into the lateral plate mesoderm region adjacent to the prospective wing field

- Position platinum electrodes parallel to embryo with anode facing targeted LPM

- Deliver 5 pulses of 20V, 50ms duration with 100ms intervals using square wave electroporator

- Seal window with transparent tape and return eggs to 38°C incubator

Day 2: Analysis of Electroporation Efficiency

- Harvest embryos at HH14 (8-10 hours post-electroporation)

- Screen for EGFP expression in LPM using fluorescence microscopy

- Process embryos for whole-mount in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry [10]

Phenotypic Analysis Methods

A. Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization:

- Generate antisense riboprobes for Tbx5, Hox genes, Fgf10, and Shh

- Fix embryos in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C

- Follow standard hybridization protocols with proteinase K permeabilization [9]

- Document expression patterns using high-magnification microscopy

B. Section Immunohistochemistry:

- Cryosection EGFP-positive embryos at 10-20μm thickness

- Immunostain with antibodies against Hox proteins (e.g., anti-Hoxb4), Tbx5, or limb markers

- Counterstain with DAPI for nuclear visualization

- Quantify expression domains and cell counts in targeted versus contralateral control regions [11]

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Hox Gene Regulatory Hierarchy in Limb Positioning. Hox4/5 genes establish a permissive field (yellow) throughout the neck region, while Hox6/7 genes provide instructive signals (green) that directly activate Tbx5 expression, initiating the limb development cascade.

The molecular hierarchy of limb positioning involves sequential activation of specific transcriptional programs:

Permissive Phase (Hox4/5-dependent):

- Hox4/5 expression establishes molecular competence in LPM cells

- Creates permissive territory extending through cervical region

- Does not directly initiate limb program but enables cellular responsiveness to limb-inducing signals [5]

Instructive Phase (Hox6/7-dependent):

- Hox6/7 activation within permissive field directly triggers Tbx5 expression

- Tbx5 protein binds and activates Fgf10 transcription in LPM

- Fgf10 signaling induces Fgf8 expression in overlying ectoderm, initiating AER formation

- Positive feedback loop between Fgf10 and Fgf8 promotes limb bud outgrowth [9] [12]

Repressive Boundaries:

- Caudal Hox genes (Hox9 and beyond) suppress limb formation outside proper territory

- Anterior limit established by absence of permissive Hox signals

- This combinatorial code ensures single forelimb per body side at correct axial position [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Hox Gene Electroporation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pCIG, BGZA reporter | Electroporation constructs with fluorescent reporters for tracking transfection efficiency |

| Hox Constructs | Dominant-negative Hoxa4-7, Full-length Hoxc6, Hoxc7 | Gain-of-function and loss-of-function manipulation of Hox signaling |

| Electroporation Equipment | Square wave electroporator, Platinum electrodes, Microinjector | Physical delivery of DNA constructs to target tissues |

| Detection Reagents | Tbx5 riboprobes, Anti-GFP antibodies, Anti-Hox antibodies | Visualization of gene expression changes and protein localization |

| Embryo Culture | Fertilized chick eggs, Indian ink, Transparent tape | Embryo maintenance and manipulation during experiments |

Advanced Applications and Technical Considerations

Spatiotemporal Control of Hox Expression

For precise temporal control of Hox gene function, consider implementing:

- Inducible systems (tetracycline- or tamoxifen-regulated) for staged activation

- Photoactivatable Hox constructs for spatial restriction of activity

- Electroporation at multiple stages to test temporal requirements in limb positioning

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Image-Based Quantification:

- Measure fluorescence intensity of reporter constructs in defined LPM regions

- Calculate expression domains as percentages of total LPM length

- Quantify ectopic limb bud size relative to endogenous buds

Molecular Quantification:

- qRT-PCR on microdissected LPM regions following electroporation

- RNA-Seq of Hox-manipulated versus control LPM cells

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation to identify direct Hox targets [9]

Troubleshooting Electroporation Efficiency

- Low transfection efficiency: Optimize DNA concentration (0.5-2 μg/μL range), increase pulse duration

- Embryo viability: Ensure electrode placement avoids heart region, optimize voltage parameters

- Mosaic expression: Use multiple electroporation angles or repeated pulses for more uniform coverage

- Specificity issues: Employ LPM-specific promoters (e.g., Tbx5 regulatory elements) to restrict expression

The hierarchical model of permissive (Hox4/5) and instructive (Hox6/7) signaling provides a robust framework for understanding vertebrate limb patterning. The experimental approaches outlined here enable precise functional dissection of this regulatory code using chick embryo electroporation. These protocols support investigation of how Hox combinatorial patterns translate into specific morphological outcomes, with relevance for evolutionary biology, regenerative medicine, and congenital limb defect research.

The permissive-instructive signaling paradigm may extend beyond limb development to other Hox-regulated processes, including axial patterning and organogenesis. The tools and methods described facilitate further exploration of this fundamental mechanism in diverse developmental contexts.

The chick embryo remains a preeminent model for elucidating the fundamental principles of vertebrate limb development. Its longstanding paradigmatic value provides a unique window into the complex cellular interactions and molecular signaling that orchestrate organogenesis [13]. The accessibility of the developing embryo for surgical manipulation, including tissue grafting and microsurgery, combined with modern genetic techniques such as electroporation-mediated gene transfer, offers a powerful, integrative platform for functional genetic analysis. This system is particularly indispensable for research aimed at understanding the roles of Hox genes in conferring positional identity and patterning the limb axes. The ability to perform precise loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments in vivo allows researchers to dissect the intricate gene regulatory networks that control limb positioning, outgrowth, and patterning with a level of temporal and spatial control that is difficult to achieve in other vertebrate models.

Key Advantages Summarized

The chick embryo system offers a compelling set of advantages for developmental biology research, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Advantages of the Chick Model System for Limb Development Studies

| Advantage | Description | Application in Limb Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility & Manipulability | Embryos develop externally in eggs, allowing direct access for surgical and molecular interventions. | Permits tissue grafting (e.g., ZPA grafts), bead implantation for localized factor delivery, and microinjection/electroporation. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Significantly lower cost of acquisition and maintenance compared to mammalian models. | Enables higher sample sizes for robust statistical analysis and complex experimental designs. |

| Rapid Development | Relatively short incubation period (~21 days) for complex organogenesis. | Accelerates the timeline from experimental intervention to phenotypic analysis of limb defects. |

| Well-Staged Morphology | Normal embryonic stages are meticulously defined by the Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) staging series. | Provides a precise, standardized reference for comparing experiments and reproducible timing of interventions. |

| Molecular Tractability | Highly amenable to gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies via in ovo electroporation and virus-mediated gene transfer. | Ideal for functional analysis of genes like Hox genes, signaling molecules (FGFs, SHH, BMPs), and transcription factors (Tbx5) [5] [13]. |

The Hox Code in Limb Positioning: An Integrative Analysis

A principal strength of the chick model has been its use in deciphering the Hox code that governs the positioning of limbs along the anterior-posterior axis. Recent research using this system has revealed that limb positioning is not controlled by a single signal but by the combinatorial actions of Hox genes, which can be categorized into permissive and instructive cues [5].

Permissive and Instructive Hox Signals

- Hox4/5 Provide a Permissive Signal: Research employing loss-of-function approaches in chick embryos demonstrates that HoxPG4 and HoxPG5 genes are necessary for forelimb formation. They establish a permissive field within the neck region, a territory where limb formation is possible. However, they are insufficient on their own to initiate limb budding [5].

- Hox6/7 Provide an Instructive Signal: The final position of the forelimb is determined by the instructive action of HoxPG6 and HoxPG7 within the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM). Gain-of-function experiments, where Hox6/7 are misexpressed in the neck LPM, are sufficient to reprogram this tissue, inducing the formation of an ectopic limb bud anterior to the normal limb field. This demonstrates their instructive role in launching the limb developmental program [5].

This model elegantly explains how the forelimb is consistently positioned at the cervical-thoracic boundary across vertebrates, despite variations in neck length. The permissive Hox4/5 domain, which expanded during the evolution of the neck, is acted upon by the more posteriorly restricted instructive Hox6/7 signal to define the precise site of limb emergence.

Initiation of the Limb Program

The initiation of the limb program is marked by the expression of Tbx5 in the forelimb LPM, a master regulator gene functionally required for forelimb formation [5]. The Hox code directly regulates the activation of Tbx5. This process involves two phases: first, Hox-regulated gastrulation movements establish broad limb, interlimb, and hindlimb domains in the LPM; second, the specific Hox code, involving both activating (e.g., Hox4/5) and repressing (e.g., Hox9) factors, directly regulates Tbx5 activation in the forelimb-forming LPM [5].

Table 2: Key Hox Genes and Their Roles in Chick Forelimb Positioning

| Hox Gene | Expression Domain | Functional Role | Experimental Evidence in Chick |

|---|---|---|---|

| HoxPG4/5 (e.g., Hoxa4, Hoxa5) | Anterior LPM, including neck region | Permissive: Demarcates territory with limb-forming potential; necessary but insufficient for forelimb formation. | Loss-of-function using dominant-negative constructs reduces/abolishes forelimb formation [5]. |

| HoxPG6/7 (e.g., Hoxa6, Hoxa7) | LPM at cervical-thoracic boundary | Instructive: Determines precise position of limb bud onset; sufficient to induce ectopic limb buds. | Gain-of-function (electroporation) in neck LPM induces ectopic Tbx5+ limb buds [5]. |

| HoxPG9 | Posterior to the limb field | Repressive: Suppresses limb formation in flank/trunk regions, limiting the limb field. | Not the primary focus of [5], but noted as part of the established forelimb-forming Hox code. |

Signaling Pathways and Gene Regulatory Networks in Limb Bud Development

Limb bud development is governed by a self-regulatory system of interlinked signaling feedback loops that coordinate patterning with growth [13]. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling centers and their key interactions.

Core Signaling Feedback Loop in Limb Development

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Electroporation of Hox Genes into Chick Limb Bud Mesoderm

This protocol describes how to misexpress Hox genes or their dominant-negative variants in the lateral plate mesoderm of chick embryos to study their function in limb positioning [5].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Fertilized chick eggs (e.g., White Leghorn)

- DNA plasmid(s): Hoxa6, Hoxa7 (for gain-of-function), or dominant-negative Hoxa4, a5, a6, a7 (for loss-of-function), co-electroporated with an EGFP reporter plasmid.

- Fast Green dye (for visualizing injection)

- Electroporator and electrodes (e.g., 5mm platinum plate electrodes)

- Micropipette puller and injector

- Tyrode's solution or PBS

II. Procedure

- Incubation and Window Preparation: Incubate eggs at 38°C, ~70% humidity until embryos reach Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 12. Create a window in the eggshell and visualize the embryo using Indian ink.

- DNA Preparation: Prepare a mixture of the Hox expression plasmid and EGFP plasmid at a final concentration of 1-2 µg/µL in water or buffer with 0.1% Fast Green.

- Microinjection: Using a finely pulled glass capillary, inject 0.1-0.5 µL of the DNA solution into the dorsal layer of the lateral plate mesoderm in the prospective forelimb field.

- Electroporation: Position platinum plate electrodes on either side of the embryo. Deliver 3-5 pulses of 15-20V, 50ms duration, with 100-500ms intervals.

- Post-Procedure Care: Seal the window with transparent tape and return the eggs to the incubator for 8-48 hours for analysis.

III. Analysis

- After 8-10 hours (to HH14), check for EGFP fluorescence to confirm successful transfection.

- Analyze phenotypes at later stages (HH20-35) via in situ hybridization for markers like Tbx5, Fgf10, and Shh, and assess skeletal morphology by Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red staining.

Protocol: Direct Reprogramming of Non-Limb Mesenchyme

This assay tests the sufficiency of factors to confer limb progenitor identity, relevant to understanding Hox-induced reprogramming [14].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Factors: Prdm16, Zbtb16, Lin28a, Lin41 (optional, for proliferation).

- 3D Culture Scaffold: Hyaluronic acid (HA)-based hydrogel or Matrigel.

- Limb Culture Media Supplements: CHIR99021 (Wnt agonist), Fgf8, Retinoic Acid (RA), SB431542 (TGF-β/BMP antagonist), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor).

II. Procedure

- Isolate non-limb fibroblasts (e.g., from flank or neck) from HH19-20 chick embryos or equivalent mouse embryos.

- Transfert fibroblasts with the combination of factors (Prdm16, Zbtb16, Lin28a).

- Culture the transfected cells in a 3D HA-gel scaffold with the supplemented limb culture media.

- Maintain culture for 8 days, monitoring cell proliferation and marker expression.

III. Analysis

- Assess the expression of limb progenitor markers (e.g., Prx1, Lhx2, Sall4) via immunostaining or RT-qPCR.

- Test differentiation potential by grafting reprogrammed cells into a host limb bud and analyzing contribution to cartilage (Sox9+) and tendon (Collagen I+) [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chick Limb Development Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Loss-of-function studies; blocks DNA binding of endogenous Hox proteins. | Elucidating necessity of Hox4/5 in establishing permissive field for limb formation [5]. |

| Hox Expression Plasmids | Gain-of-function studies; misexpresses Hox genes in ectopic locations. | Testing sufficiency of Hox6/7 to instruct limb bud formation in neck LPM [5]. |

| EGFP Reporter Plasmid | Visualizes successfully transfected/electroporated cells. | Co-electroporation with Hox constructs to mark and trace manipulated cells [5]. |

| Limb Progenitor Reprogramming Factors (Prdm16, Zbtb16, Lin28a) | Converts non-limb fibroblasts into limb progenitor-like cells. | Studying the genetic basis of limb progenitor specification and potential [14]. |

| 3D Hydrogel Scaffold (HA-based) | Mimics the early limb bud extracellular matrix for cell culture. | Maintaining limb progenitor cells in a more authentic, proliferative state in vitro [14]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Agonists (CHIR, Y-27632, SB431542) | Controls specific signaling pathways in cell culture (Wnt, ROCK, TGF-β/BMP). | Creating in vitro culture conditions that sustain limb progenitor identity and potency [14]. |

The initiation of limb development represents a fundamental process in vertebrate embryogenesis, culminating in the formation of correctly positioned and type-specific appendages. A cornerstone of this process is the activation of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5, a master regulator gene whose expression in the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) is both necessary and sufficient to trigger forelimb bud formation [15] [16] [17]. The precise spatial and temporal restriction of Tbx5 is critical, as it dictates the exact axial position at which the forelimb emerges. Recent research has elucidated that this restricted expression is directly governed by a combinatorial Hox code—a specific set of Hox genes expressed along the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo [9] [18] [19]. This application note provides a detailed experimental framework, grounded in key chick embryo electroporation studies, for investigating how Hox genes directly regulate the Tbx5 enhancer to initiate the limb program. We summarize pivotal quantitative data, provide step-by-step protocols for gain- and loss-of-function experiments, and visualize the core regulatory pathways, offering a practical toolkit for researchers exploring the molecular basis of limb positioning and its implications for evolutionary biology and congenital disorders.

Core Regulatory Logic: The Hox-to-Tbx5 Pathway

The molecular pathway from Hox gene expression to Tbx5 activation and subsequent limb outgrowth can be conceptualized in a two-step model. First, a permissive Hox environment (primarily involving HoxPG4 and HoxPG5 genes) establishes a territory in the LPM with the potential to form a limb [5]. Second, an instructive signal (governed by HoxPG6 and HoxPG7 genes) within this permissive territory actively initiates the limb program by directly activating Tbx5 transcription [5] [20]. This activation is counterbalanced by repressive Hox proteins (like Hoxc9) expressed in caudal LPM, which sharpen the posterior boundary of the Tbx5 expression domain [19]. The following diagram synthesizes this core regulatory logic, illustrating the key genes and their functional interactions in the prospective forelimb field.

Diagram 1: Core regulatory pathway governing Tbx5 activation. HoxPG4/5 genes provide a permissive background, while HoxPG6/7 provide an instructive signal for activation. Repressive Hox genes (e.g., Hoxc9) define the caudal boundary.

Key Experimental Data and Phenotypes

The model above is supported by robust gain-of-function (GOF) and loss-of-function (LOF) experiments in chick embryos. The table below synthesizes the quantitative findings from these studies, detailing the necessity and sufficiency of specific Hox paralogy groups (PG) in inducing Tbx5 expression and limb bud formation.

Table 1: Summary of Hox Gene Gain/Loss-of-Function Phenotypes in Chick Limb Initiation

| Hox Paralogy Group | Necessary for Endogenous Limb? (LOF Phenotype) | Sufficient for Ectopic Limb? (GOF Phenotype) | Effect on Tbx5 Expression | Key Molecular Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoxPG4/5 (e.g., Hoxa4, Hoxa5) | Necessary: DN* mutants downregulate Tbx5 [5] | Not Sufficient: Does not induce ectopic Tbx5 or buds in neck LPM [5] [20] | Downregulated in LOF [5] | Fgf10 downregulated in LOF [5] |

| HoxPG6/7 (e.g., Hoxa6, Hoxa7) | Necessary: DN mutants downregulate Tbx5 [5] | Sufficient: Induces ectopic Tbx5 and bud formation in neck LPM [5] [20] | Downregulated in LOF; Ectopically induced in GOF [5] [20] | Fgf10 induced in GOF; Ectopic buds lack Fgf8 [20] |

| HoxPG9/10 (e.g., Hoxc9) | Not directly tested via LOF in chick | N/A | Represses Tbx5 enhancer activity [19] | Confines Tbx5 expression to rostral LPM [18] [19] |

| *DN: Dominant-Negative |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides standardized protocols for the key experiments that established the regulatory relationship between Hox genes and Tbx5, utilizing the chick embryo as a model system.

Protocol 1: Gain-of-Function via Electroporation to Induce Ectopic Limb Buds

This protocol tests the sufficiency of Hox genes to initiate the limb program in non-limb forming territories, such as the neck LPM [5] [20].

- Plasmid Preparation: Subclone the full-length cDNA of the Hox gene of interest (e.g., Hoxa6 or Hoxa7) into the pCIG or RCAS expression vector. The pCIG vector contains an IRES-eGFP element, enabling co-expression of the Hox gene and a GFP reporter from a single transcript [9] [5].

- Embryo Preparation: Incubate fertilized chicken eggs until embryos reach Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 10-12. Window the eggs under sterile conditions to access the embryo.

- DNA Injection and Electroporation:

- Inject the plasmid DNA (1 µg/µL in PBS with Fast Green tracer) into the lumen of the neural tube at the level of the neck (cervical) LPM.

- Position the embryo so that the positive electrode is on the same side as the injected DNA. Deliver five pulses of 50 ms each at 25V with a 100-150 ms interval using a square-wave electroporator.

- Incubation and Harvest: Reseal the windowed egg with tape and return it to the 37°C incubator for 22-48 hours, allowing the embryo to develop until HH14-18.

- Analysis:

- Screening: Identify successfully electroporated embryos by visualizing GFP fluorescence in the targeted LPM.

- Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WMISH): Fix embryos and analyze the expression of key markers: Tbx5 (initiation), Fgf10 (mesenchymal outgrowth signal), and Fgf8 (AER formation) [9] [20].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Observe the formation of ectopic limb buds anterior to the native forelimb location.

Protocol 2: Loss-of-Function using Dominant-Negative Electroporation

This protocol assesses the necessity of specific Hox genes for endogenous limb formation by disrupting their function in the prospective wing field [5].

- Construct Design: Generate a dominant-negative (DN) form of the target Hox gene (e.g., Hoxa4-dn). The DN construct lacks the C-terminal portion of the homeodomain, rendering it unable to bind DNA but retaining the ability to sequester essential co-factors, thereby disrupting the function of the endogenous wild-type protein [5].

- Embryo Preparation and Electroporation: Follow steps 2-4 from Protocol 1, but electroporate the DN-encoding plasmid into the LPM at the level of the prospective forelimb (rather than the neck).

- Analysis:

- After 8-10 hours of incubation (to HH14), screen for GFP-positive embryos.

- Perform WMISH for Tbx5. A successful knockdown will show a marked downregulation or absence of Tbx5 expression on the electroporated side compared to the control side.

- Analyze subsequent markers like Fgf10 and Fgf8 to confirm the failure to establish the FGF signaling feedback loop.

- Monitor the development of the wing bud; a severe reduction or absence is expected.

Protocol 3: Analyzing Direct Regulation using Enhancer Reporter Assays

This protocol tests the direct action of Hox proteins on the identified Tbx5 forelimb enhancer [9] [19].

- Reporter and Effector Constructs:

- Co-electroporation: Co-inject both the reporter and effector plasmids into the chick hindbrain or LPM and electroporate as in Protocol 1. The hindbrain provides a well-characterized system for testing enhancer function [9].

- Analysis:

- After 22 hours, harvest embryos and process for β-galactosidase activity to visualize reporter expression.

- Compare the expression pattern of the wild-type enhancer versus mutant versions when co-expressed with different Hox genes. Mutagenesis of specific Hbs should ablate Hox responsiveness [19].

The following workflow diagram encapsulates the key stages of Protocol 1 and 2.

Diagram 2: Generalized experimental workflow for chick in ovo electroporation studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues the critical reagents and their applications for studying Hox-Tbx5 interactions in limb initiation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Hox/Tbx5 Limb Initiation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Type / Species | Primary Function in Experiment | Key Application / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCIG Vector | Plasmid | Bicistronic expression vector; expresses gene of interest and eGFP via IRES. | Visualizes electroporated cells; pCIG-Hoxa6/a7 for GOF [5]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox (e.g., Hoxa4-dn) | Engineered DNA | Loss-of-function; disrupts activity of endogenous Hox proteins. | Used to test necessity in prospective wing field [5]. |

| Tbx5 forelimb enhancer (361 bp) | DNA Regulatory Element | Reporter construct; recapitulates forelimb-restricted Tbx5 expression. | Contains 6 Hox binding sites; used to test direct regulation [9] [19]. |

| Tbx5, Fgf10, Fgf8 probes | RNA (for WMISH) | Gene expression analysis; markers for limb initiation and outgrowth. | Readout for successful Hox manipulation [9] [5]. |

| Hoxc9 | cDNA / Protein | Repressor of Tbx5; defines caudal expression boundary. | Used to map repressive domains and mechanisms [19]. |

| Chick Embryo (HH10-12) | Animal Model | Electroporation recipient; ideal for rapid functional studies. | Model system of choice for cited gain/loss-of-function studies. |

The experimental data and protocols outlined herein establish a clear and direct regulatory pathway: specific combinations of Hox proteins, expressed in a colinear fashion along the anterior-posterior axis, bind to and directly control a key enhancer of the Tbx5 gene, thereby initiating the limb developmental program at a precise embryonic position [9] [18] [19]. The functional dissection of this pathway relies on the precise application of electroporation-based gain-of-function and loss-of-function strategies in the chick model.

For researchers, several critical considerations are paramount. First, the choice of Hox paralogy group is essential, as HoxPG6/7 genes carry instructive potential that HoxPG4/5 genes lack, despite both being necessary [5] [20]. Second, the specificity of dominant-negative constructs must be empirically validated to avoid misinterpretation of phenotypes [20]. Finally, while the Hox-Tbx5 axis initiates the limb program, successful outgrowth requires coordinated signaling with the overlying ectoderm, which may have its own region-specific competencies [20] [21]. Mastering these protocols provides a powerful means to not only understand fundamental embryological principles but also to model how alterations in this regulatory cascade contribute to evolutionary diversity and congenital limb defects.

Precision Electroporation: Protocols for Hox Gene Manipulation in Chick Limb Buds

In the field of developmental biology, Hox genes encode a family of transcription factors that play a fundamental role in organizing the anterior-posterior (AP) axis and specifying positional identity in vertebrate embryos [5]. These genes exhibit both spatial and temporal collinearity, meaning they are activated in a sequence reflecting their chromosomal position and are expressed in domains whose anterior boundaries along the body axis correspond to their location within the clusters [22]. A significant body of research has established that Hox genes are crucial for the proper growth and skeletal patterning of tetrapod limbs, with genes from the HoxA and HoxD clusters being particularly important for both fore- and hindlimb development [23]. The precise positioning of limb buds along the AP axis is governed by a combinatorial Hox code in the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) [5].

Two primary experimental approaches—gain-of-function (GOF) and loss-of-function (LOF)—have been instrumental in deciphering the roles of specific Hox genes in limb positioning and development. GOF experiments involve introducing and expressing a gene of interest in cells or tissues where it is not normally active, allowing researchers to assess its sufficiency to induce specific developmental programs. Conversely, LOF experiments aim to disrupt the function of an endogenous gene, revealing its necessity in a given process. In chick embryos, electroporation of the LPM has emerged as a powerful technique for implementing both strategies, enabling precise spatial and temporal control over gene manipulation [5]. This application note details the experimental design principles and protocols for choosing and implementing these complementary approaches within the context of Hox gene research in the chick limb bud.

Core Principles: GOF vs. LOF Approaches

Scientific Rationale and Application Contexts

Gain-of-Function (GOF) and Loss-of-Function (LOF) approaches answer fundamentally different biological questions. The choice between them depends on the specific hypothesis being tested.

- GOF is used to determine whether a gene is sufficient to initiate a specific developmental program or cell fate. For example, a recent study demonstrated that misexpression of Hox6/7 genes in the neck LPM of chick embryos is sufficient to reprogram this tissue and induce the formation of an ectopic limb bud, revealing an instructive role in forelimb positioning [5]. GOF can also be used to test functional equivalence between genes from different species or paralogous groups.

- LOF is used to determine whether a gene is necessary for a given developmental process. This was exemplified by experiments showing that suppression of Hoxa13 in the chick leads to hindgut and cloacal atresia, demonstrating its requirement for normal posterior development [24]. Similarly, knocking down HoxPG4/5 gene function resulted in changes in limb patterning [5].

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Features

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each approach to guide experimental selection.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of GOF and LOF Approaches

| Feature | Gain-of-Function (GOF) | Loss-of-Function (LOF) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | Is gene X sufficient to induce phenotype Y? | Is gene X necessary for process Z? |

| Typical Outcome | Ectopic expression, homeotic transformation, or induction of specific markers. | Loss of structures, failure to express downstream markers, or patterning defects. |

| Key Strength | Can reveal instructive signals and bypass functional redundancy. | Directly tests the requirement of an endogenous gene. |

| Primary Limitation | May produce non-physiological effects; overexpression can be toxic. | Phenotypes may be masked by functional redundancy from paralogous genes. |

| Example Finding | Hox6/7 can reprogram neck LPM to form a limb bud [5]. | HOXA13 suppression causes hindgut atresia [24]. |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful execution of GOF and LOF experiments in the chick embryo requires a standardized toolkit. The following table catalogs key reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chick Electroporation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Length Hox cDNA | A plasmid containing the complete coding sequence of a Hox gene. Used for GOF studies to produce a functional transcription factor. | Misexpressing Hoxc8 to test its ability to alter limb positioning [5]. |

| Dominant-Negative (DN) Hox Construct | A plasmid expressing a truncated Hox protein that binds co-factors but not DNA, thereby inhibiting the function of endogenous wild-type proteins. A common LOF tool. | Electroporation of DN-Hoxa4, a5, a6, or a7 to study their requirement in the forelimb field [5]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmid (e.g., EGFP) | A plasmid expressing a fluorescent protein. Used to mark successfully electroporated cells, allowing for visualization of the transfection domain. | Co-electroporation with experimental plasmids to identify transfected regions in the LPM [5]. |

| Tbx5 In Situ Hybridization Probe | A labeled RNA probe to detect Tbx5 mRNA, a key marker for the initiation of the forelimb program in the LPM. | Assessing the expansion or reduction of the forelimb field after Hox manipulation [5]. |

| HH Staged Chick Embryos | Fertilized chicken eggs incubated to specific developmental stages according to the Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) staging system. | Using HH12 embryos for electroporation into the prospective wing field [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gain-of-Function via Electroporation

This protocol describes how to misexpress a Hox gene in the chick LPM to test its sufficiency in altering limb positioning or identity.

- Plasmid Preparation: Maxi-prep a high-purity plasmid containing the full-length Hox cDNA of interest, driven by a constitutive promoter (e.g., CAGGS or CMV). A plasmid expressing a fluorescent reporter (e.g., EGFP) is essential and can be co-electroporated or included on the same vector via an IRES or 2A peptide.

- Egg Windowing and Staining: Incubate fertilized chick eggs to the desired stage (e.g., HH12 for targeting the forelimb field). Create a small window in the eggshell above the embryo. Visualize the embryo by injecting a small volume of India ink diluted in PBS beneath the embryo.

- DNA Injection: Using a finely pulled glass capillary needle and a microinjector, inject ~1 µL of the plasmid DNA mixture (at a concentration of 1-3 µg/µL) into the dorsal part of the lateral plate mesoderm at the desired axial level.

- Electroporation: Position platinum plate electrodes on either side of the embryo. Apply 5 pulses of 20V for 50 ms duration with 100 ms intervals using a square wave electroporator. The polarity should direct the DNA toward the targeted LPM.

- Post-Procedure Care: Seal the window in the eggshell with transparent tape and return the eggs to the incubator for the desired period, typically 8-48 hours, to allow for gene expression and phenotypic analysis.

- Analysis: Harvest the embryos and image the fluorescence to confirm the electroporation domain. Analyze phenotypes using whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) for key markers like Tbx5 (forelimb) or Hoxd13 (distal limb patterning) [23] [5], and/or perform immunohistochemistry.

Protocol 2: Loss-of-Function via Dominant-Negative Electroporation

This protocol uses a dominant-negative (DN) strategy to inhibit the function of a specific Hox gene or paralog group.

- DN Construct Design: A dominant-negative Hox construct is generated by deleting the C-terminal portion of the homeodomain. This renders the protein incapable of binding DNA while retaining its ability to dimerize with transcriptional co-factors, thereby sequestering them and blocking wild-type function [5].

- Electroporation: The steps for egg preparation, DNA injection, and electroporation are identical to the GOF protocol (Steps 2-5). The DN construct, along with a fluorescent reporter, is delivered into the limb-forming LPM.

- Phenotypic Assessment: After 8-10 hours of incubation (to HH14), initial validation of transfection is confirmed by EGFP expression. A key early readout is the downregulation of Tbx5 expression in the forelimb field, indicating a failure to initiate the limb program [5]. Later harvests allow for the assessment of morphological defects in limb patterning and skeletal elements.

Diagram 1: Experimental Selection Workflow

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Key Readouts and Phenotypic Scoring

The analysis of GOF and LOF experiments relies on a combination of molecular and morphological readouts.

- Molecular Markers: The most immediate readout is the expression of key marker genes. In the context of limb positioning, Tbx5 is the primary indicator of forelimb field specification [5]. For later limb patterning, the expression of 5' HoxD genes (e.g., Hoxd11-d13) is critical for autopod (hand/foot) development and can be visualized by WISH [23].

- Morphological Phenotypes: Ultimately, changes in marker expression must be correlated with anatomical outcomes. This includes the formation of ectopic limb structures in GOF experiments, or the reduction, loss, or malformation of the native limb in LOF experiments. Skeletal preparations (e.g., Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red staining) are used to analyze the bone and cartilage patterns in developed limbs.

Navigating Complexity: Interpreting Results

Interpreting the outcomes of these experiments requires an understanding of the inherent complexity of Hox gene function.

- Functional Redundancy: A common challenge in LOF studies is the lack of a strong phenotype due to redundancy between Hox paralogs (genes with the same number in different clusters, e.g., Hoxa4 and Hoxb4). This may require simultaneous knockdown of multiple paralogs to reveal a gene's function.

- Combinatorial Code: Hox genes do not act in isolation. The positioning of the forelimb, for instance, depends on a permissive signal from HoxPG4/5 and an instructive signal from HoxPG6/7 [5]. Therefore, the phenotype from manipulating one gene must be interpreted within this broader regulatory context.

- Temporal Considerations: The timing of electroporation is critical, as Hox genes act at different phases of limb field establishment and outgrowth. Electroporating too early or too late may miss the relevant developmental window.

Diagram 2: Hox Gene Signaling Pathway Example

The following table provides a final, consolidated comparison to guide researchers in selecting and applying GOF and LOF approaches effectively in their studies on Hox genes and limb development.

Table 3: Summary Comparison of GOF and LOF Applications

| Aspect | Gain-of-Function (GOF) | Loss-of-Function (LOF) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Tests sufficiency of a gene to instruct a cell fate or developmental program. | Tests necessity of a gene for a specific developmental process. |

| Ideal Use Case | Identifying instructive signals; determining if a gene can reprogram cell fate (e.g., Hox6/7 inducing limb in neck LPM). | Assessing the requirement of a gene in its native context; defining the elements of a Hox code. |

| Key Readout | Ectopic expression of markers (e.g., Tbx5); formation of ectopic structures. | Loss or reduction of marker expression; truncation or patterning defects in native structures. |

| Data Interpretation | Can reveal master regulatory potential. Results may be confounded by non-physiological expression levels. | Provides clear evidence for gene function. Null results may be due to paralog redundancy. |

| Complementary Nature | GOF reveals potential; LOF reveals requirement. Used together, they provide a comprehensive understanding of gene function within the combinatorial Hox code governing limb positioning and development. |

In the study of vertebrate limb development, the electroporation of Hox genes in the chick embryo has emerged as a powerful technique for unraveling the molecular mechanisms controlling limb positioning and patterning. Hox genes encode a family of transcription factors that confer positional identity along the anterior-posterior axis, with specific paralog groups determining the precise locations where limbs emerge [5]. The ability to manipulate Hox gene expression through vector-based approaches enables researchers to investigate how these genes control target gene expression, cell ingression, and ultimately, the termination of body elongation and positioning of appendages [25] [22]. This application note provides detailed methodologies for constructing both full-length and dominant-negative Hox vectors, with specific application to chick limb bud electroporation experiments, offering researchers a comprehensive toolkit for probing the functional roles of Hox genes in vertebrate development.

Hox Gene Function and Experimental Rationale

The Role of Hox Genes in Vertebrate Development

Hox genes exhibit remarkable spatial and temporal collinearity—they are activated sequentially along the chromosome and expressed in domains whose anterior boundaries reflect their position in the clusters [25]. In chicken embryos, 39 Hox genes are organized in four clusters containing up to thirteen paralogous genes each [25] [22]. These genes function as key regulators of axial patterning, with posterior Hox genes (paralogs 9-13) playing a crucial role in controlling body elongation through repression of Wnt activity, leading to graded repression of Brachyury/T transcription factor and subsequent reduction of mesoderm ingression [25] [22].

In limb development, Hox genes operate through sophisticated combinatorial codes. Research demonstrates that Hox4/5 genes provide permissive signals for forelimb formation throughout the neck region, while instructive cues from Hox6/7 in the lateral plate mesoderm determine the final forelimb position [5]. This precise regulatory mechanism explains why limbs consistently emerge at specific axial locations despite variations in vertebral numbers across species.

Rationale for Hox Vector Constructs

The strategic design of Hox expression constructs enables distinct functional investigations:

Full-length constructs facilitate gain-of-function studies, allowing researchers to determine the sufficiency of specific Hox genes to induce phenotypic changes or transcriptional programs when misexpressed.

Dominant-negative constructs enable loss-of-function investigations by interfering with endogenous Hox protein function, providing crucial evidence for necessity even when complete genetic knockouts are impractical.

The chick embryo system offers particular advantages for these studies, including accessibility for manipulation and well-characterized developmental timelines, making it an ideal model for Hox gene functional analyses.

Vector Design Strategies

Full-Length Hox Construct Design

Full-length Hox constructs should contain the complete coding sequence to recapitulate all functional domains of the native protein. The design must account for the conserved domain architecture of Hox proteins, which includes the DNA-binding homeodomain and transcriptional regulatory regions.

Key Components:

- Coding Sequence: Amplify the complete open reading frame from cDNA sources, ensuring inclusion of all functional domains.

- Promoter Selection: Use strong, ubiquitous promoters (e.g., CAGGS, CMV) for widespread expression or tissue-specific promoters for targeted manipulation.

- Tagging Strategy: Incorporate epitope tags (e.g., HA, FLAG, GFP) at either N- or C-termini for detection and localization studies.

- Regulatory Elements: Include WPRE (Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus Posttranscriptional Regulatory Element) for enhanced RNA stability and expression.

Dominant-Negative Hox Construct Design

Dominant-negative Hox constructs are engineered to lack DNA-binding capability while retaining protein-protein interaction domains, enabling them to sequester co-factors and block endogenous Hox function [5]. This approach is particularly valuable for interrogating the functional requirements of specific Hox genes in a temporally and spatially controlled manner.

Engineering Strategy:

- Homeodomain Truncation: Delete or disrupt the C-terminal portion of the homeodomain to abolish DNA binding while preserving co-factor interactions [5].

- Dimerization Domains: Retain intact protein-protein interaction domains to facilitate formation of non-functional complexes with endogenous partners.

- Nuclear Localization: Ensure preservation of nuclear localization signals to target the construct to the appropriate cellular compartment.

Table 1: Comparison of Hox Vector Construct Types

| Feature | Full-Length Construct | Dominant-Negative Construct |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Capacity | Fully functional | Disrupted/eliminated |

| Co-factor Interaction | Intact | Retained |

| Functional Outcome | Gain-of-function | Loss-of-function |

| Primary Application | Sufficiency testing | Necessity testing |

| Typical Promoter | Ubiquitous or tissue-specific | Ubiquitous or tissue-specific |

| Common Tags | GFP, HA, FLAG | GFP, HA, FLAG |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Cloning of Hox Constructs

Materials:

- cDNA source (chick cDNA library, RT-PCR products)

- Expression vector backbone (e.g., pCAGGS, pMES)

- Restriction enzymes or recombination cloning system

- Competent E. coli cells

- Antibiotics for selection

- Plasmid purification kits

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Amplify Hox Coding Sequence

- Design gene-specific primers with appropriate restriction sites or recombination sites

- Perform high-fidelity PCR with proofreading polymerase

- Verify amplicon size by agarose gel electrophoresis

Vector Preparation

- Digest destination vector with appropriate restriction enzymes

- Alternatively, prepare vector for recombination cloning

- Purify linearized vector fragment

Ligation/Recombination

- Mix insert and vector at optimal molar ratios (typically 3:1 to 5:1)

- Perform ligation or recombination reaction according to manufacturer's protocol

- Incubate at appropriate temperature and duration

Transformation and Selection

- Transform competent E. coli cells with the reaction mixture

- Plate on selective media containing appropriate antibiotics

- Incubate overnight at 37°C

Screening and Validation

- Pick individual colonies for culture and plasmid purification

- Verify constructs by restriction digest and analytical gel electrophoresis

- Confirm sequence fidelity by Sanger sequencing

Protocol 2: Chick Embryo Electroporation of Hox Constructs

Materials:

- Fertilized chick eggs (Hamburger-Hamilton stage 12-15 for limb studies)

- Electroporation apparatus (square wave electroporator, electrodes)

- Injection needles (borosilicate glass)

- Microinjector system

- Plasmid DNA purified with endotoxin-free kits

- Fast Green dye (0.1% in PBS) for visualization

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Embryo Preparation

- Window fertilized chick eggs incubated to desired stage (HH12-15)

- Visualize embryos under dissecting microscope

- Remove extraembryonic membranes if necessary

DNA Preparation

- Dilute purified plasmid DNA to 1-2 μg/μL in TE buffer or PBS

- Add Fast Green dye to final concentration of 0.1% for visualization

- Centrifuge briefly to remove particulates

DNA Injection

- Load DNA solution into injection needle

- Position needle in target region (lateral plate mesoderm for limb studies)

- Inject approximately 0.1-0.5 μL per embryo using pneumatic picopump

Electroporation

- Position electrodes flanking the target tissue

- Apply 5 pulses of 20V, 50ms duration, with 100ms intervals

- Ensure current flows through DNA-loaded region

Post-Electroporation Processing

- Add antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin) to prevent infection

- Seal window with transparent tape

- Return eggs to incubator for desired development period

Analysis

- Harvest embryos at appropriate time points

- Process for in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, or other analyses

Applications in Chick Limb Bud Research

Investigating Limb Positioning Mechanisms

The electroporation of Hox constructs in chick limb buds has been instrumental in deciphering the molecular logic of limb positioning. Research has established that Hox4/5 genes create a permissive field for limb formation, while Hox6/7 provide instructive signals that determine the precise position of forelimb emergence [5]. By electroporating dominant-negative Hox constructs targeting Hoxa4, a5, a6, or a7 into the lateral plate mesoderm, researchers have demonstrated that these genes are necessary for proper Tbx5 activation and subsequent forelimb formation [5].

Analyzing Signaling Pathway Interactions

Hox genes function within complex regulatory networks, interacting with key signaling pathways including Wnt, FGF, and retinoic acid (RA) signaling [25] [22]. The electroporation of Hox constructs enables researchers to map these interactions by assessing how Hox misexpression alters pathway activity and downstream gene expression. For example, posterior Hox genes have been shown to repress Wnt activity with increasing strength, leading to graded repression of Brachyury/T and subsequent slowing of axis elongation [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Hox Electroporation Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| pCAGGS Expression Vector | High-level transgene expression in chick embryos | Contains CAGGS promoter (CMV enhancer + chicken β-actin promoter) |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Loss-of-function studies | Truncated homeodomain, intact protein interaction motifs [5] |

| Fast Green FCF Dye | Visualization during microinjection | 0.1% in PBS, non-toxic to embryos |

| Electroporation Electrodes | Directional DNA delivery | Platinum or gold, various configurations for specific tissues |

| Hamburger-Hamilton Stage Series | Embryo staging and timing | Detailed morphological criteria for precise developmental staging |

| Tbx5 Expression Markers | Readout of limb field specification | Early marker of forelimb formation [5] |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Hox Construct Electroporation Workflow

Diagram 2: Hox Signaling in Limb Positioning

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Technical Challenges

Low Transfection Efficiency

- Optimize DNA concentration (typically 1-2 μg/μL)

- Verify electrode positioning and orientation

- Test multiple voltage parameters (15-25V range)

Embryo Viability Issues

- Ensure proper temperature maintenance during procedures

- Use minimal anesthesia time

- Implement strict sterile technique

Variable Expression Patterns

- Standardize injection volume and placement

- Use consistent DNA preparation methods

- Confirm plasmid quality and concentration

Validation Methods

- Epitope Tag Detection: Immunostaining for HA, FLAG, or GFP tags to confirm expression

- In situ Hybridization: Monitor endogenous target gene expression changes

- Western Blotting: Verify protein expression levels and sizes

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess morphological changes in limb development

The strategic application of full-length and dominant-negative Hox constructs in chick limb bud electroporation experiments provides powerful insights into the mechanisms governing vertebrate limb patterning and positioning. The methodologies outlined in this application note offer researchers robust, reproducible techniques for manipulating Hox gene function, enabling precise dissection of their roles in embryonic development. As research advances, these approaches continue to reveal the sophisticated regulatory networks that orchestrate the formation of complex anatomical structures, with implications for evolutionary biology, regenerative medicine, and developmental genetics.

This application note provides a detailed methodology for the electroporation of the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) in HH12 (Hamburger-Hamilton stage 12) chick embryos. This technique is a cornerstone for investigating the Hox gene code that governs limb positioning and patterning [5]. The targeted electroporation of constructs—such as dominant-negative Hox genes, gain-of-function variants, or fluorescent reporters—into the forelimb-forming region of the LPM allows for the functional dissection of gene roles in conferring positional identity to future limb-forming cells without concurrently altering vertebral identity [5]. The protocol below is optimized for precision and efficiency in this specific developmental context.

The experimental workflow for LPM electroporation, from embryo preparation to analysis, is summarized in the following diagram.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

A. Embryo Preparation (Day 1)

- Incubation: Incubate fertilized chick eggs in a humidified incubator at 38°C for approximately 45-48 hours to reach the desired HH12 stage [5].

- Windowing: Carefully tap a small hole into the blunt end of the egg to create an air sac. Using fine scissors, cut a window of approximately 1.5 cm x 1.5 cm in the eggshell above the embryo.

- Visualization: Dilute Indian ink 1:10 in Howard Ringer's solution or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Using a sharp glass capillary needle or micropipette, inject a small volume of diluted ink beneath the embryo to create a dark background, enhancing contrast for clear visualization.

- Verification: Confirm the embryo is at HH12 under a dissection microscope. Key characteristics include:

- Formation of 13 somite pairs.

- The head turning to the right.

- Well-developed heart loops.

B. Electroporation Setup

- DNA Preparation: Prepare a DNA solution containing your plasmid of interest (e.g., pCAGGS-EGFP for visualization, or Hoxa4/5/6/7 constructs for functional studies [5]) at a concentration of 1-3 µg/µl in PBS with a fast-green dye (0.1-0.5%) for visual tracking during injection.

- Microelectrode Preparation: Pull borosilicate glass capillaries (1.0 mm outer diameter) to a fine tip (5-10 µm) using a micropipette puller.

- Electrode Positioning: Fill the microelectrode with the DNA solution and mount it on a micromanipulator. Position the anode (positive electrode) over the dorsal layer of the LPM in the prospective wing field of the embryo [5]. Position the cathode (negative electrode) on the opposite side of the embryo.

C. Electroporation Execution

- DNA Injection: Using a picopump or air pressure system, inject a small bolus of the DNA solution (typically 0.1-0.5 µl) into the target region of the LPM. The fast-green dye will allow you to confirm the precise location of the injection.

- Pulse Application: Immediately after injection, deliver electrical pulses. The exact parameters are critical and should be optimized. The table below summarizes parameters from published research and provides a starting point for optimization [5] [26].

- Post-Pulse Care: Gently withdraw the electrode. Add a few drops of antibiotic-containing PBS (1x Penicillin-Streptomycin) to the egg to prevent contamination. Seal the window in the eggshell with transparent tape and return the egg to the 38°C incubator for further development.

D. Post-Electroporation Analysis

After an incubation period of 8-10 hours (to HH14 for initial expression checks) or longer (e.g., 48-72 hours for phenotypic analysis), re-open the egg and harvest the embryo [5].

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Imaging: Analyze electroporation efficiency and localization using fluorescence microscopy for EGFP or other fluorescent reporters.

- In Situ Hybridization/Immunohistochemistry: Perform to assess changes in gene expression (e.g.,

Tbx5) resulting from your experimental manipulation [5].

Key Experimental Parameters & Optimization

Electroporation efficiency and cell viability are a complex function of multiple electrical parameters. The following table consolidates key quantitative data from the literature to guide protocol development [5] [26].

Table 1: Electroporation Parameters for LPM Targeting

| Parameter | Example from Literature | Optimization Range | Notes & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | HH12 [5] | HH10-HH14 | HH12 is specified as the origin of wing mesoderm. |

| Field Strength | Not explicitly stated | 10 - 50 V/mm | Must exceed the electropermeabilization threshold of the cell membrane [26]. |

| Pulse Length | Not explicitly stated | 1 - 50 ms | Millisecond pulses are common for GET; length influences molecular uptake and viability [27] [26]. |

| Number of Pulses | Not explicitly stated | 3 - 5 | Multiple pulses can increase uptake but reduce viability; a balance is required [27]. |

| Waveform | Not explicitly stated | Square-wave, Exponential decay | Exponential decay pulses may exceed square-wave efficiency in some contexts [26]. |

| DNA Concentration | 1-3 µg/µl (implied) [5] | 0.5 - 5 µg/µl | Higher concentration increases uptake but can be toxic. Fast-green dye at 0.1-0.5% is used for visualization [5]. |

| Viability Assessment | 24+ hours post-electroporation [5] | 8-48 hours | Assessed by continued development and DAPI staining versus control samples [26]. |

| Efficiency Readout | EGFP expression after 8-10h [5] | 8-72 hours | Initial expression detectable at HH14. Confirmed via fluorescence microscopy [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for LPM Electroporation

| Item | Function/Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| pCAGGS-EGFP Plasmid | Ubiquitous mammalian expression plasmid driving EGFP. Serves as a vital reporter for visualizing electroporated cells and assessing targeting efficiency [5]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Engineered Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa4, a5, a6, a7) lacking DNA-binding domains. Used in loss-of-function studies to compete with and suppress endogenous Hox gene function in the LPM [5]. |

| Fast-Green Dye | A visible dye mixed with the DNA solution. Allows for real-time visual confirmation of the injection site within the LPM before pulse delivery [5]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Hydrogels | A major component of the limb bud extracellular matrix. Used in 3D culture systems to maintain limb progenitor cells in a more authentic state after electroporation [14]. |

| FUCCI Cell Cycle Reporter | A fluorescent ubiquitination-based cell cycle indicator. Used in live-cell imaging to track the effects of electroporation and PEFs on cell cycle progression in real-time [26]. |

Critical Pathway & Mechanistic Insight

Understanding the biological context of Hox genes in LPM patterning is crucial for designing electroporation experiments. The following diagram illustrates the key regulatory interactions that this protocol enables researchers to manipulate and study.

The diagram shows that HoxPG4/5 genes provide a permissive signal, demarcating a territory in the neck region where a limb can form [5]. Within this permissive field, HoxPG6/7 genes provide an instructive signal that is sufficient to reprogram neck LPM to activate the key limb initiation gene Tbx5 and induce ectopic limb bud formation [5]. Successful electroporation of constructs that manipulate these Hox genes allows for direct testing of this model.

The chicken embryo has long been a cornerstone model in developmental biology due to its accessibility for surgical manipulation and observation. The recent advent of reliable transgenic technologies has dramatically enhanced its utility, creating powerful tools for visualizing dynamic cellular behaviors in living embryos. These tools are particularly transformative for studying complex processes like vertebrate limb development, where understanding cell lineage and morphogenesis requires observing cells over time. By enabling high-resolution, live imaging of specific cell populations, transgenic chick lines bridge a critical gap between classical embryology and modern cell biology, allowing researchers to move from static snapshots to dynamic movies of development.

Available Transgenic Chick Lines and Their Applications

Reporter Lines for Limb Bud Compartments

A significant advancement is the generation of a dual-reporter transgenic chicken line specifically designed for limb bud studies. This line uses the Tol2 transposon system for genomic integration and is created via cultured Primordial Germ Cells (PGCs), a method that has made generating genetically modified chicken lines relatively feasible [28].

The table below summarizes the key features of this transgenic line:

- Table 1: Dual-Fluorescence Reporter Chick Line for Limb Bud Analysis

| Feature | Limb Mesenchyme Reporter | Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) Reporter |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter | Mouse Prrx1 limb mesenchymal promoter [28] | Mouse Msx2 AER-specific promoter [28] |

| Fluorescent Reporter | ZsGreen [28] | DsRed [28] |

| Labeled Cell Types | Limb bud mesenchyme (gives rise to cartilage, bones, connective tissues) [28] | Apical Ectodermal Ridge cells [28] |

| Primary Application | Visualizing dynamics and differentiation states of limb mesenchymal cells in living embryos [28] | Visualizing the dynamics and role of the AER, a key signaling center [28] |

| Key Utility | Facilitates detailed characterization of limb mesenchyme and AER cells during development [28] | A powerful tool for advancing the study of vertebrate limb development [28] |

Ubiquitous Nuclear Labeling for Cell Tracking

Beyond tissue-specific lines, transgenic avians with ubiquitous fluorescent expression are invaluable for large-scale cell tracking. A comparable transgenic quail model, Tg(PGK1:H2B-chFP), ubiquitously expresses a nuclear-localized monomer cherry fluorescent protein (chFP) under the control of the human PGK1 promoter [29]. This model offers several key advantages:

- Nuclear Localization: The H2B-chFP fusion protein localizes to the nucleus, simplifying the identification and automated tracking of individual cells during complex morphogenetic events [29].

- Ubiquitous Expression: The reporter is expressed in all embryonic cells from stage X through later stages (e.g., stage 11), allowing for the visualization of any tissue or cell population [29].

- Quantitative Analysis: This system is ideal for 4D (xyzt) live imaging and quantitative analysis of cell behaviors, such as those during gastrulation, head fold formation, and dorsal aortae formation [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating a Transgenic Reporter Chick Line via PGCs

The following protocol outlines the key steps for creating a novel transgenic chick line, as used for the limb bud reporter line [28].

- Step 1: Vector Construction. Clone the tissue-specific promoters (e.g., the 2.4-kb mouse Prrx1 promoter and the Msx2 proximal promoter) upstream of their respective fluorescent protein genes (e.g., ZsGreen, DsRed) within a plasmid containing Tol2 transposable elements [28].