Mastering Xenopus Embryo Microinjection: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Targeted Techniques

This comprehensive guide details the established microinjection techniques for Xenopus laevis embryos, a cornerstone methodology in developmental biology, cell biology, and drug discovery research.

Mastering Xenopus Embryo Microinjection: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Targeted Techniques

Abstract

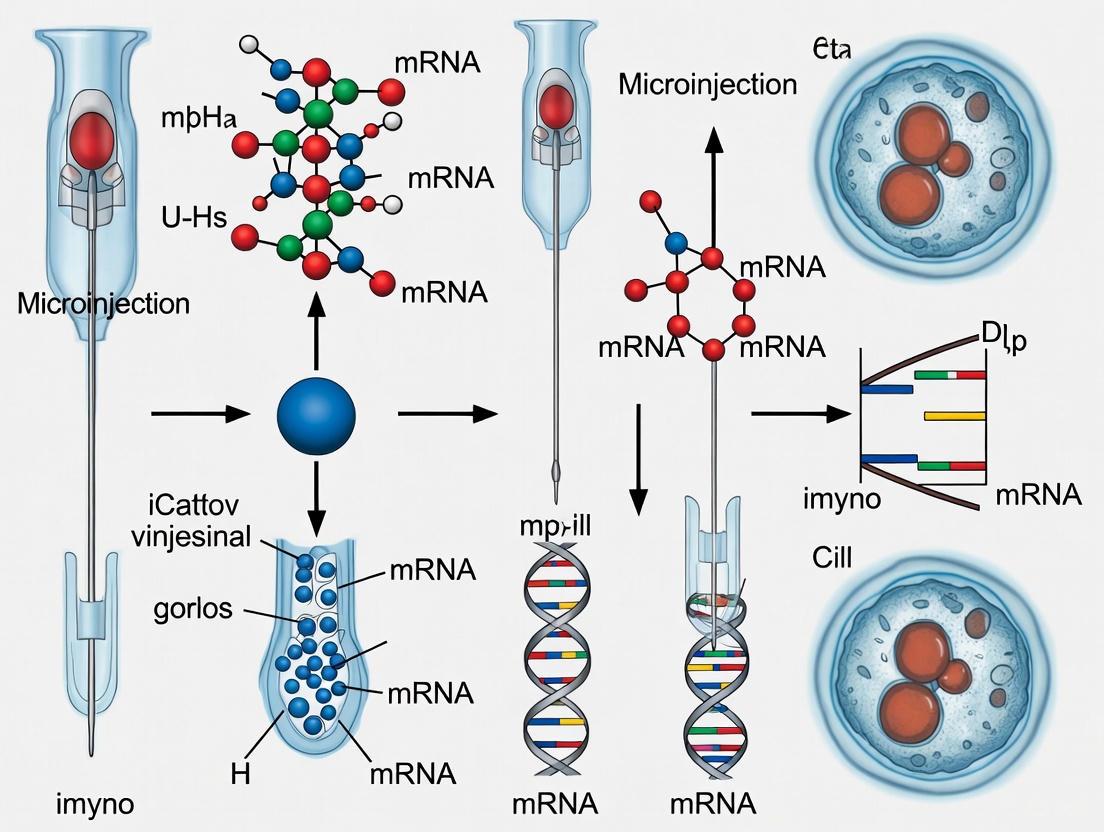

This comprehensive guide details the established microinjection techniques for Xenopus laevis embryos, a cornerstone methodology in developmental biology, cell biology, and drug discovery research. It covers foundational principles, including the rationale for using Xenopus as a model system and essential equipment setup. The article provides step-by-step methodological protocols for both standard and advanced targeted microinjection, utilizing fate maps for specific tissues like the pronephros. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance survival rates and experimental reproducibility. Finally, the guide explores validation techniques through lineage tracing and immunostaining, and discusses the comparative advantages of Xenopus microinjection for functional gene analysis and protein expression studies.

Xenopus Microinjection Foundations: Principles, Applications, and Model System Advantages

Why Xenopus? Key Advantages of the Frog Model System for Microinjection

The genus Xenopus, particularly the species Xenopus laevis (African clawed frog) and Xenopus tropicalis (Western clawed frog), has established itself as a cornerstone of biological research for decades. Its initial rise to prominence began in the 1930s with its use in the Hogben pregnancy test, a novel bioassay that was simpler and more reliable than previous methods [1]. Since then, Xenopus has evolved into an indispensable tool for developmental biology, genetics, and biomedical research. The external fertilization, large and readily manipulable eggs, and rapid embryonic development of these frogs make them uniquely suited for microinjection-based studies [1] [2]. This application note details the specific advantages of the Xenopus system for microinjection, provides a comparative analysis of the two primary species used, and outlines key protocols for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in high-throughput screening and disease modeling.

Key Advantages for Microinjection and Research

The choice of Xenopus as a model system is underpinned by a set of distinct biological and practical characteristics that facilitate experimental manipulation and enhance the translatability of research findings.

Large, Externally Developing Eggs and Embryos: Xenopus eggs are among the largest of all vertebrates, measuring about 1-1.3 mm in diameter [1]. This substantial size makes them exceptionally easy to visualize and manipulate under a stereomicroscope. Furthermore, their external development allows for direct access to all stages of embryogenesis without invasive procedures, enabling straightforward microinjection, surgical manipulation, and continuous observation [1] [3] [2].

Rapid and Synchronous Development: Following fertilization, Xenopus embryos develop rapidly, reaching the tadpole stage within a few days [1]. This rapid timeline allows for the efficient design and execution of experiments, significantly accelerating research cycles compared to other vertebrate models. Embryos from a single clutch develop synchronously, providing a large cohort of specimens at identical developmental stages for robust statistical analysis [2].

High Genetic and Physiological Conservation with Humans: Despite its evolutionary distance, Xenopus shares a high degree of genetic conservation with humans. Over 80% of known human disease-associated genes have orthologs in the Xenopus genome [4] [5]. Critical signaling pathways such as Wnt, BMP, and FGF, which govern fundamental processes like cell division, differentiation, and organogenesis, are highly conserved, making findings in Xenopus directly relevant to human biology and disease [1] [4].

Ease of Genetic Manipulation: The Xenopus system is highly amenable to a wide array of genetic manipulations. Techniques such as microinjection of mRNA, DNA, and morpholino oligonucleotides have been standard for decades [6] [7]. More recently, the advent of CRISPR/Cas9 technology has enabled precise genome editing, allowing researchers to model human genetic diseases with high efficiency and at a lower cost compared to mammalian models [2] [5].

Robustness and High Fecundity: Xenopus embryos are remarkably resilient and can withstand experimental manipulations such as microinjection and surgical procedures with high survival rates [1]. A single female can produce thousands of eggs in one laying, providing ample biological material for high-throughput screening of genetic or chemical factors [5].

Transparency for Live Imaging: The relative transparency of Xenopus embryos and tadpoles, particularly in early stages, permits high-resolution live imaging of developmental processes. This feature is invaluable for tracking cell migrations, such as those of cranial neural crest cells, and for visualizing organogenesis in real-time without the need for dissection [3] [4] [2].

Comparative Analysis of Xenopus Species

While both Xenopus laevis and X. tropicalis are widely used, they possess distinct characteristics that make them suitable for different research applications. The table below provides a detailed comparison to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate species for their work.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis

| Feature | Xenopus laevis | Xenopus tropicalis |

|---|---|---|

| Ploidy | Allotetraploid (36 chromosomes) [5] | Diploid (20 chromosomes) [8] [5] |

| Adult Size | Larger (10-12 cm females) [1] | Smaller (4-6 cm) [1] [8] |

| Embryo Size | Larger (~1.3 mm) [1] [6] | Smaller [6] |

| Generation Time | ~12 months [8] | 4-6 months [8] |

| Genome Sequence | Sequenced in 2016 [1] | First frog genome sequenced (2010) [1] [5] |

| Ideal for | Embryological studies, microinjection training, protein/oocyte expression [1] [9] | Genetic studies, CRISPR/Cas9, comparative genomics [1] [6] [2] |

| Key Advantage | Large embryo size, robust for manipulation [1] [6] | Simpler genetics, shorter generation time [1] [8] |

Research Applications Enabled by Microinjection

The technical advantages of Xenopus microinjection have directly fueled breakthroughs across diverse fields of biomedical research.

Developmental Biology and Cell Fate Mapping: The ability to perform targeted microinjection into specific blastomeres at early cleavage stages (e.g., 4-cell, 8-cell) is a powerful application. Using established fate maps, researchers can inject materials specifically into the blastomere that gives rise to a particular organ, such as the kidney (pronephros), heart, or eyes [3]. This allows for tissue-specific overexpression or knockdown of genes, minimizing secondary effects in the rest of the embryo. Co-injection of a lineage tracer (e.g., fluorescent mRNA) enables verification of targeting and visualization of the progeny of the injected cell [3].

Disease Modeling: Xenopus is extensively used to model human genetic diseases. By injecting mRNAs carrying gain-of-function mutations or using morpholinos/CRISPR to create loss-of-function models, researchers have studied a wide spectrum of disorders [5]. These include congenital heart defects, kidney disease, ciliopathies, and various craniofacial malformations such as DiGeorge syndrome and Treacher Collins syndrome [4] [5]. The rapid development and easy scoring of phenotypes make it an efficient model for validating disease-associated genes.

Craniofacial Development Research: Xenopus is a premier model for studying craniofacial morphogenesis, which depends on the precise migration and differentiation of cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs) [4]. Microinjection is used to perturb genes involved in CNCC specification, migration, and differentiation, helping to elucidate the etiology of common birth defects like cleft lip and palate. The external development and large embryos allow for direct in vivo visualization of CNCC behaviors at a resolution often not achievable in mammalian models [4].

Pigmentation and Pigmentary Disorders: The melanocytes of Xenopus develop and function similarly to those in mammals. Changes in pigmentation are exceptionally easy to score in live embryos [5]. Microinjection of morpholinos or CRISPR components targeting pigmentation genes (e.g., MITF) can model human pigmentary disorders and melanoma. The system is also valuable for studying skin responses to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) and DNA repair mechanisms [5].

Ion Channel and Receptor Studies: While not performed in embryos, the microinjection of in vitro-transcribed mRNA into Xenopus oocytes is a classic technique for the heterologous expression and functional characterization of ion channels, receptors, and transporters [9]. This system allows for precise electrophysiological and pharmacological studies of human proteins in a controlled environment.

Essential Equipment and Reagents for Microinjection

A successful microinjection experiment requires specific equipment and reagents. The following table lists the core components of the "Researcher's Toolkit."

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment for Xenopus Microinjection

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Stereomicroscope | A microscope with good optics and a large working distance (at least 8-10 cm) is essential for visualizing embryos and manipulating injection needles [7]. |

| Micromanipulator & Microinjector | Apparatus for holding the injection pipette and delivering precise, controlled volumes of solution into embryos or oocytes [9] [7]. |

| Injection Pipettes | Fine, glass capillaries pulled to a sharp tip for piercing the embryo membrane without causing significant damage. |

| Lineage Tracers | Fluorescent dyes, dextrans, or mRNA encoding fluorescent proteins (e.g., MEM-RFP) used to trace the fate of injected cells and verify targeting [3]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Antisense molecules used to transiently knock down gene expression by blocking mRNA translation or splicing [3] [5]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Components | Cas9 protein/RNA and guide RNAs for creating targeted, heritable gene knockouts or knock-ins [2]. |

| In vitro Transcription Kits | For synthesizing capped mRNA for overexpression studies or for creating lineage tracer RNA [7]. |

| Marc's Modified Ringer's (MMR) | A common saline solution for maintaining embryos and oocytes [3]. |

| Dejelly Solution (e.g., 2% Cysteine) | For removing the protective jelly coat surrounding fertilized eggs prior to microinjection [3]. |

Detailed Microinjection Protocol for Embryos

The following protocol outlines the key steps for microinjecting Xenopus embryos, with specific considerations for both X. laevis and X. tropicalis.

Protocol Workflow

Protocol Steps

1. Embryo Preparation and Selection

- Obtain embryos through natural mating or in vitro fertilization using hormones [3]. Once laid, transfer fertilized embryos into a Petri dish.

- Remove the protective jelly coat by incubating embryos in a 2% cysteine solution (pH 8.0) for a few minutes with gentle agitation. Rinse thoroughly with an appropriate buffer like 1x MMR [3].

- Select healthy, undamaged embryos and align them on an injection dish fitted with a nylon mesh or in grooves made of agarose to immobilize them during injection [3] [9].

2. Injection Needle Preparation and Loading

- Pull borosilicate glass capillaries to create fine-tipped injection needles using a pipette puller.

- Backfill the needle with a small amount of mineral oil using a syringe. Then, front-load the needle with your injection sample (e.g., morpholino, CRISPR mix, mRNA) by immersing the tip into the droplet and using the microinjector's suction function to draw up the desired volume [9].

3. Blastomere Targeting and Orientation

- For targeted injections, use the established Xenopus fate maps available on Xenbase [3]. At the 4-cell stage, the ventral blastomeres contribute significantly to the kidney and other ventral tissues. At the 8-cell stage, the ventral-vegetal blastomere (V2) is the primary contributor to the pronephros [3].

- Orient the embryos under the microscope so the targeted blastomere is accessible. The pigmented animal pole and the lighter vegetal pole serve as visual guides.

4. Microinjection Execution

- Mount the loaded needle onto the micromanipulator. Using the manipulator, position the needle at a shallow angle relative to the embryo.

- Gently insert the needle into the target blastomere. Use a brief pulse of pressure from the microinjector to deliver the solution. A visible clearing or slight expansion of the cell indicates a successful injection.

- Wait a few seconds before retracting the needle to prevent the backflow of the injected material [9].

5. Post-Injection Incubation and Analysis

- After injection, transfer the embryos to a fresh dish with incubation medium (e.g., 0.1x MMR).

- Critical Step: Regulate the incubation temperature tightly. Cooler temperatures (e.g., 14-16°C) slow development, providing a larger time window for injections at specific stages [3].

- Allow embryos to develop to the desired stage. Phenotypic analysis can include live imaging for lineage tracers, whole-mount immunostaining to visualize specific tissues (e.g., pronephric tubules), or molecular biology techniques to assess gene expression changes [3].

Research Applications Workflow

The general workflow for a functional genetics study in Xenopus from microinjection to analysis is summarized below.

The Xenopus frog system remains an powerful and versatile model for microinjection-based research. Its unique combination of large, robust embryos, rapid external development, and high genetic conservation with humans offers unparalleled advantages for developmental studies, disease modeling, and drug screening. The continued development of sophisticated genetic tools like CRISPR/Cas9, coupled with its inherent suitability for high-throughput approaches, ensures that Xenopus will continue to be a vital organism for answering fundamental biological questions and advancing human health.

Microinjection in Xenopus embryos and oocytes is a cornerstone technique for developmental biology and functional genomics. This application note details established and emerging protocols for targeted gene manipulation, leveraging the unique advantages of the Xenopus system, including externally developing embryos, a well-defined fate map, and high fecundity. We focus on specific methodologies for gene overexpression and knockdown, concluding with advanced applications for studying protein function.

Targeted Microinjection for Gene Manipulation

The power of microinjection in Xenopus is vastly enhanced by the use of fate maps, which allow researchers to target specific blastomeres that give rise to particular tissues and organs. This enables tissue-specific manipulation of gene expression and the creation of mosaic embryos where manipulated and unmanipulated tissues can be compared within the same organism [3] [10].

The table below summarizes the primary blastomeres targeted for specific tissues at the 4-cell and 8-cell stages.

Table 1: Blastomere Selection for Tissue-Targeted Microinjection

| Target Tissue | Stage | Blastomere Name | Blastomere Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney (Pronephros) | 4-cell | Ventral Blastomere | Large, darkly pigmented cell [3] |

| 8-cell | V2 Blastomere | Ventral, vegetal blastomere [3] | |

| Retina | 32-cell | - | Specific blastomeres identified via retina fate map [10] |

The following workflow outlines the key steps for performing targeted microinjection and subsequent analysis.

Protocol: Kidney-Targeted Microinjection at the 8-Cell Stage

This protocol describes how to target the developing pronephros (kidney) in Xenopus laevis embryos [3].

Materials:

- Dejellied Xenopus embryos at the 8-cell stage.

- Injection reagents: Morpholinos, mRNA for overexpression, or cDNA constructs.

- Lineage tracer: e.g., MEM-RFP or MEM-GFP mRNA.

- Microinjection setup: Injector, micromanipulator, pulled borosilicate glass needles.

- Solutions: 1x MMR, 2% cysteine (pH 8.0) for dejellying.

Method:

- Prepare Embryos: Collect embryos and remove the jelly coat by incubating in 2% cysteine (pH 8.0). Rinse thoroughly in 1x MMR [3].

- Identify Blastomere: Under a stereomicroscope, orient the embryo to locate the left ventral, vegetal (V2) blastomere. This cell is vegetal (yolky, less pigmented) and ventral (larger and darker than dorsal cells) [3].

- Prepare Injection Needle: Back-fill a needle with mineral oil, then front-fill with your injection solution mixed with lineage tracer [11].

- Inject: Penetrate the V2 blastomere and inject ≤ 15 nL of solution. A successful injection will show a slight dimpling and filling of the cell [3] [11].

- Incubate: Transfer injected embryos to a dish with 1x MMR and incubate at 14-16°C to slow development, allowing more time for subsequent manipulations if needed [3].

- Verify Targeting: At tailbud stages (stage 38-40), image the embryo to confirm the lineage tracer fluorescence is localized to the pronephric region. Fix embryos for whole-mount immunostaining with pronephric-specific antibodies for detailed analysis [3].

Gene Overexpression and Knockdown Techniques

Microinjection enables diverse strategies for modulating gene function. The table below compares the core techniques.

Table 2: Core Microinjection Techniques for Gene Manipulation

| Technique | Reagent Injected | Primary Mechanism | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Overexpression | Synthetic mRNA [10] or cDNA [11] | Introduces exogenous coding sequence for translation | Functional analysis, rescue experiments, dominant-negative effects |

| Knockdown (Morpholino) | Antisense Morpholino Oligomers (MOs) [12] | Blocks translation initiation or pre-mRNA splicing | Loss-of-function studies, phenocopy of mutations |

| Knockdown (CRISPRi) | dCas9-KRAB mRNA + gene-specific gRNAs [13] | Represses transcription by blocking RNA polymerase | Specific mRNA suppression, alternative to MOs |

| Protein Expression | cDNA or mRNA [14] [11] | Heterologous expression in oocytes/embryos | Studying channel/transporter function, protein localization |

Protocol: mRNA Overexpression and Knockdown with Morpholinos

Materials:

- For mRNA injection: Synthetic mRNA encoding the protein of interest, resuspended in nuclease-free water.

- For Morpholino injection: Antisense Morpholino oligonucleotide targeting the gene of interest.

- Injection equipment and materials as in Protocol 1.1.

Method:

- Reagent Preparation: Dilute synthetic mRNA or Morpholino to the desired working concentration in nuclease-free water. Co-inject with a fluorescent lineage tracer [10] [12].

- Microinjection: Follow the general microinjection and blastomere targeting steps outlined in Protocol 1.1. Inject into the cytoplasm of the target blastomere.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate embryos and monitor development. Analyze phenotypes, then fix embryos for in situ hybridization, immunostaining, or other techniques to assess molecular changes [12].

Emerging Protocol: Gene Knockdown with CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi)

While traditional Morpholinos are effective, CRISPRi offers a modern, DNA-targeting alternative for gene knockdown. A 2025 study in Xenopus tropicalis demonstrated that CRISPRi, specifically using dCas9 fused to a KRAB repressor domain (dCas9-KM), efficiently suppresses both exogenous and endogenous mRNA transcription. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas13 systems were found to be ineffective in this model [13].

Materials:

- mRNA encoding the dCas9-KM repressor fusion protein.

- Synthetic gRNAs targeting the gene of interest.

- Standard microinjection setup.

Method:

- Reagent Preparation: Co-inject a mix of dCas9-KM mRNA (e.g., 300 pg/embryo) and a pool of target-specific gRNAs (e.g., 100 pg/embryo each) into the fertilized egg at the one-cell stage [13].

- Incubation and Validation: Allow embryos to develop to the desired stage. Assess knockdown efficacy via quantitative PCR (qPCR), phenotypic analysis, or loss of specific markers (e.g., loss of pigmentation for tyrosinase) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Xenopus Microinjection

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lineage Tracers | Visualizing progeny of injected blastomere | MEM-RFP, MEM-GFP, fluorescent dextrans [3] [15] |

| Morpholinos (MOs) | Gene knockdown; block translation/splicing | Antisense oligonucleotides; control MOs are critical [12] |

| Synthetic mRNA | Gene overexpression; express wild-type/mutant proteins | In vitro transcribed from plasmid templates (e.g., CS2+) [10] [15] |

| cDNA Constructs | Heterologous protein expression; mosaic analysis | Injected into oocyte nucleus or embryos [11] [15] |

| Microinjection Setup | Precise delivery of reagents | Injector, micromanipulator, micropipette puller, forceps [3] [11] |

| Fate Maps | Guide targeted blastomere injection | Available online at Xenbase [3] |

Protein Function and Live Imaging Applications

Beyond transcriptional manipulation, microinjection is pivotal for studying protein function, localization, and dynamic cellular processes.

Protocol: Heterologous Protein Expression in Oocytes

Xenopus oocytes are a premier system for expressing and studying proteins from diverse organisms [11].

Materials:

- Stage V-VI oocytes manually isolated from ovarian tissue.

- cDNA construct (50-200 µg/mL) for nuclear injection.

- Modified Barth's Solution (MBS).

- Microinjection setup with a plunger-based system (e.g., Drummond Nanoject).

Method:

- Oocyte Preparation and Isolation: Manually defolliculate oocytes using fine forceps. Allow oocytes to recover overnight at 16-20°C in MBS [11].

- Nuclear Injection (cDNA): Orient healthy oocytes with the animal (pigmented) pole upward. Load a needle with cDNA solution (<3 ng per oocyte). Penetrate the animal pole and inject into the germinal vesidium (nucleus) [11].

- Cytoplasmic Injection (mRNA): For mRNA injection, target the vegetal cytoplasm. This is more tolerant of larger injection volumes but requires more mRNA for equivalent expression [11].

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate injected oocytes for 24-72 hours. Screen for protein expression using western blotting, electrophysiology, radioisotope flux, or imaging, depending on the protein and experimental goal [14] [11].

Protocol: Live Imaging of Cell and Developmental Processes

The large size and clarity of Xenopus embryonic cells make them ideal for high-resolution live imaging [15].

Materials:

- Embryos injected with mRNA encoding fluorescent fusion proteins (e.g., memGFP, τ-GFP).

- Low-melt agarose.

- Custom-made or commercial imaging chambers with a cover glass bottom.

- Confocal or spinning-disk microscope.

Method:

- Label Embryos: Inject low doses (15-500 pg, optimized empirically) of mRNA encoding fluorescently tagged proteins into embryos to label cellular structures (membrane, organelles, cytoskeleton) [15].

- Mount for Imaging: Embed live embryos in low-melt agarose within the imaging chamber, ensuring the tissue of interest is positioned close to the cover glass [15].

- Image Acquisition: Collect time-lapse Z-stacks on an inverted confocal microscope. Adjust acquisition speed and laser power to minimize photodamage while capturing the dynamic process [15].

The microinjection techniques outlined here—from targeted blastomere injections and various knockdown/overexpression strategies to live imaging—provide a comprehensive toolkit for probing gene and protein function in the versatile Xenopus model. Mastery of these protocols enables precise interrogation of developmental mechanisms, disease processes, and fundamental cell biology.

Microinjection is a foundational technique in developmental biology for introducing exogenous materials such as DNA, RNA, proteins, or drugs directly into cells and embryos. Within Xenopus embryo research, this method is indispensable for probing gene function, protein dynamics, and early developmental mechanisms [16] [17]. The success of these intricate experiments hinges on a properly configured workstation comprising a vibration-damped microscope, precise micromanipulators, and meticulously prepared microinjection needles [16] [18]. This application note details the essential equipment specifications and protocols for establishing a robust microinjection system tailored to Xenopus embryo research, providing a critical technical resource for the experimental foundation of a doctoral thesis.

Core Microinjection System Specifications

A reliable microinjection system rests on three core components: the microscope, micromanipulator, and microinjector. Their integration must provide stability, optical clarity, and precise control.

Microscope Selection and Key Specifications

For microinjection of Xenopus oocytes and embryos, an inverted microscope is generally recommended due to its superior working distance and accessibility for micromanipulators [16] [19]. The condenser must have a long or ultra-long working distance to accommodate manipulator arms without obstruction [16]. Stability is paramount; the microscope should be placed on a heavy, vibration-damped table in a quiet location to isolate it from environmental disturbances [16] [18]. The following table summarizes the critical microscope specifications and common models suitable for this research.

Table 1: Microscope Specifications for Xenopus Microinjection

| Microscope Type | Key Feature | Recommended Model Examples | Contrast Techniques | Typical Magnification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inverted Microscope | Long working distance condenser | Nikon ECLIPSE Ti2 series, Ts2R/ Ts2R-FL [19] | Differential Interference Contrast (DIC), Phase Contrast [19] | 200x for cytoplasmic injection, 400x for nuclear injection [20] |

| Upright Microscope | Horizontal micropipette access | Zeiss Axioskop [18] | DIC, Nomarski [18] | Dependent on objective and eyepiece |

Micromanipulators and Microinjectors

The micromanipulator is responsible for the fine, three-dimensional positioning of the micropipette. Its stability directly governs the success of the entire procedure [16]. Electronic models are highly advantageous as they allow for programmable, precise movements to pre-determined coordinates [16] [20]. The microinjector controls pressure within the micropipette. Different applications require different pressures; for instance, injecting DNA solution into a pronucleus requires high pressure (>3000 hPa), while holding oocytes requires mild positive and negative pressures [16]. A digital microinjector allows for independent control of base pressure (to prevent medium backflow) and injection pressure pulses [16] [20].

Table 2: Micromanipulator and Microinjector Configurations for Key Applications

| Application in Xenopus Research | Recommended Micromanipulator | Recommended Microinjector | Pressure Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronuclear DNA Injection | Two XenoWorks manipulators (Right/Left) [16] | XenoWorks Digital microinjector [16] | High injection pressure >3000 hPa; subtle negative holding pressure [16] |

| Oocyte Holding & Somatic Cell Transfer | Two XenoWorks manipulators (Right/Left) [16] | Two XenoWorks Analog microinjectors [16] | Mild positive and negative pressure for holding and transfer [16] |

| General Cytosolic/Nuclear Injection | Eppendorf TransferMan NK2 [20] | Eppendorf FemtoJet [20] [21] | Injection pressure (Pi): 600-1800 hPa; Compensation pressure (Pc): ~180 hPa [21] |

Microneedle Preparation Protocols

The quality of the micropipette is a decisive factor for cell viability and injection success. The preparation process involves pulling, back-filling, and carefully breaking the tip to the desired diameter.

Micropipette Pulling Procedure

- Equipment Setup: Use a horizontal, double-stage micropipette puller, such as a Sutter Instrument P-87 or P-97 [20] [21]. Turn the machine on at least 20 minutes before use to ensure thermal stability [21].

- Glass Capillary Selection: Use borosilicate glass capillaries with an outer diameter of 1.0 mm and an inner filament, which facilitates back-filling by capillary action (e.g., World Precision Instruments #1B100F-4) [20] [21].

- Pulling Parameters: Program the puller for a multi-step process. Example parameters for a Sutter P-87 are: Heat=600, Pull=100, Velocity=140, Time=150; followed by Heat=960, Pull=0, Velocity=40, Time=250; and a final step of Heat=960, Pull=27-30, Velocity=60, Time=252 [21]. The goal is a needle that tapers over 0.4-0.6 cm to a sharp, closed point [20].

- Storage: Store pulled needles in a covered storage jar or attached to the sticky side of foam strips in a Petri dish to protect them from dust and damage [18] [21].

Needle Back-Filling and Tip Breaking

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the injection solution (e.g., DNA in distilled water). Centrifuge it at maximum speed for 10 minutes to pellet particulate matter that could clog the needle [21]. Adding a visible dye like Fast Green (0.1% w/v) or a fluorescent marker like Dextran Texas Red helps visualize the solution during injection [20].

- Back-Filling: Using a fine, pulled pipette tip or a microloader, carefully aspirate a small volume of the prepared solution. Insert the tip into the back of the needle and expel the solution, allowing it to flow to the tip via capillary action over 2-3 minutes [20] [21]. Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Breaking the Tip: Mount the filled needle on the manipulator. Under microscopic observation (40x objective), lower the needle tip towards the broken edge of a coverslip. Gently tap the needle against the edge to break off a tiny piece and open the tip [21]. The ideal tip diameter is approximately 0.5 µm for cytoplasmic injection and 0.2-0.5 µm for nuclear injection [20].

- Verifying Flow: Engage the microinjector and press the foot pedal to check for a rapid, laminar flow of injection solution from the needle tip. There should be no flow at the resting compensation pressure [21]. Adjust the compensation pressure (

Pc) to prevent backflow of medium into the needle, which would dilute the injection solution [20].

Experimental Workflow for Microinjection

The microinjection process is a systematic sequence from sample preparation to post-injection care. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages for a typical experiment involving Xenopus oocytes or embryos.

Diagram 1: Microinjection Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful microinjection relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials, each serving a specific function to ensure cell viability and experimental integrity.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Xenopus Microinjection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Halocarbon Oil | Creates an inert, immiscible layer over samples on an injection pad to prevent desiccation [22] [21]. | Series 700 (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich H8898) [22] [21] |

| Agarose Pads | Provides a stable, non-toxic, and slightly adhesive surface for immobilizing oocytes or embryos during injection [23] [21]. | 2% agarose in water, baked onto coverslips [23] [21] |

| Marker Dyes | Co-injected with substances of interest to visually confirm successful delivery and estimate injection volume [20]. | Fast Green (0.1%), Dextran Texas Red [20] |

| Recovery Buffer | A physiological solution used to recover and rehydrate samples after the injection procedure [22]. | M9 buffer or specialized recovery buffer with salts and glucose [22] |

| Modified Barth's Saline (MBS) | A standard medium for holding and culturing Xenopus oocytes and embryos, maintaining osmotic balance and pH [17]. | 1x MBS with Penicillin/Streptomycin [17] |

Mastering the setup and operation of the microinjection workstation is a prerequisite for advanced research in developmental biology using the Xenopus model. The precise alignment of a vibration-resistant microscope, a stable micromanipulator, and a pressure-controlled microinjector, combined with consistently prepared micropipettes, forms the foundation for reproducible and high-yield experiments. By adhering to the detailed equipment specifications and standardized protocols outlined in this document, researchers can effectively troubleshoot their systems and reliably generate high-quality data for their investigations into gene function and embryonic development.

Understanding Early Xenopus Embryogenesis and Critical Developmental Stages for Injection

The African clawed frog (Xenopus) has served as a cornerstone model organism in developmental biology for decades, providing fundamental insights into embryonic development, cell signaling, and gene function. Its external development, large, readily manipulable embryos, and high fecundity make it an exceptional system for microinjection-based studies [24] [2]. Mastering the precise staging of early Xenopus embryogenesis is paramount for the success of these techniques, as the timing of developmental events is temperature-dependent and crucial for experimental reproducibility [25]. This application note details the critical early developmental stages of Xenopus laevis and provides a standardized protocol for targeted microinjection, serving as an essential resource for researchers employing these techniques in fundamental and applied biomedical research.

Normal Table of Development and Key Staging Landmarks

The Nieuwkoop and Faber (NF) staging system is the definitive standard for characterizing Xenopus development, defining 66 distinct stages based on discrete morphological features rather than temporal or size metrics [25]. This allows the system to be consistently applied across different Xenopus species and laboratory conditions.

For microinjection experiments, the early cleavage, blastula, and gastrula stages (NF 1-20) are most critical. The table below summarizes key morphological landmarks and experimental considerations for these stages.

Table 1: Critical Early Developmental Stages for Microinjection inXenopus laevis

| NF Stage | Name | Key Morphological Landmarks | Optimal Injection Target / Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | Fertilized Egg to 4-Cell | Single cell; first cleavage bisects left/right; second cleavage divides dorsal/ventral [3]. | All blastomeres are totipotent. Injection into a single blastomere at the 4-cell stage can target its progeny [3]. |

| 4 | 8-Cell | Third cleavage separates animal (darker, pigmented) and vegetal (yolky) hemispheres [3]. | Ventral-vegetal (V2) blastomeres contribute significantly to the kidney (pronephros) [3]. |

| 5-6 | 16- to 32-Cell | Cleavages become less synchronous. Blastomeres are named based on lineage (e.g., V2.2 at 16-cell) [3]. | The V2.2 blastomere (also known as C3 at the 32-cell stage) is the primary contributor to the pronephros [3]. |

| 6.5-9 | Morula to Early Blastula | "Mulberry" cluster of cells; formation of blastocoel cavity begins [2]. | Common stage for mRNA injection into the blastocoel or animal pole for widespread overexpression. |

| 10 | Early Gastrula | Dorsal lip of the blastopore forms, marking the start of gastrulation [25]. | Critical stage for manipulating Spemann-Mangold organizer signals. Injection near the dorsal lip can affect axial patterning. |

| 12.5 | Mid Gastrula | Blastopore is crescent-shaped [25]. | |

| 13-20 | Neurula | Blastopore closes; neural plate folds into neural tube [2]. | Stages for analyzing neural induction and patterning; injections are less common. |

Experimental Protocol: Targeted Microinjection of Early Embryos

This protocol describes the methodology for targeted microinjection into specific blastomeres of 4- and 8-cell stage Xenopus laevis embryos to manipulate gene expression in a tissue-specific manner, using the pronephros (kidney) as an example.

I. Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Microinjection

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Dejelly Solution (2% Cysteine, pH 8.0) | Removes the protective jelly coat from naturally laid embryos to enable manipulation and injection [3]. |

| Marc's Modified Ringers (MMR) | Standard saline solution for raising and maintaining Xenopus embryos post-injection [3]. |

| Testes Storage Solution (1x MMR, 1% BSA, Gentamycin) | Medium for storing isolated male testes used for in vitro fertilization [3]. |

| Lineage Tracer (e.g., MEM-RFP mRNA) | RNA encoding a fluorescent protein (e.g., membrane-targeted RFP) co-injected to confirm successful targeting and visualize progeny of the injected blastomere [3]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides or mRNA | Agents for knocking down or overexpressing genes of interest, respectively [3] [24]. |

| Microinjection Needles | Fine glass capillaries pulled to a sharp point for piercing the vitelline membrane and blastomere. |

| Micromanipulator & Microinjector | Apparatus for holding the needle and delivering nanoliter-volume injections with high precision [3] [24]. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

A. Embryo Preparation

- Obtain embryos through natural mating or in vitro fertilization. For in vitro fertilization, squeeze eggs from a hormonally primed female into a dish and fertilize with a macerated testis [3].

- Once the jelly coats have swollen (approximately 15 minutes post-fertilization), pour off excess water and add ~50 ml of Dejelly Solution. Gently swirl for 3-5 minutes until embryos pack closely together.

- Rinse embryos thoroughly with 1x MMR (or similar medium) several times to remove all traces of cysteine [3].

- Temperature Control: Incubate dejellied embryos at 14-16°C to slow the rate of development. This provides a longer window for performing injections at the 4- and 8-cell stages [3].

B. Blastomere Identification and Targeting

- Using a dissecting microscope, orient the embryo with the animal pole (darkly pigmented) facing upward and the vegetal pole (light, yolky) downward.

- Identify the cleavage planes. The first cleavage typically separates the left and right sides. The second cleavage separates dorsal (smaller, less pigmented cells) from ventral (larger, darker cells) [3].

- For 4-cell injections: To target the left kidney, inject the left ventral blastomere.

- For 8-cell injections: To target the left kidney, inject the left ventral-vegetal (V2) blastomere [3].

- Refer to the following workflow diagram for the overall experimental process.

C. Microinjection Process

- Back-fill a pulled glass needle with the injection solution (e.g., morpholino/mRNA mixed with lineage tracer).

- Calibrate the injection volume (typically 5-10 nL per blastomere for early stage embryos) by measuring the diameter of the droplet expelled into oil [3] [24].

- Secure the embryo in a small well made of agarose or using a holding pipette.

- Carefully pierce the vitelline membrane and the targeted blastomere with the needle.

- Deliver the calibrated volume into the blastomere cytoplasm. Withdraw the needle smoothly.

D. Post-Injection Analysis

- Allow injected embryos to recover and develop in 1x MMR at the desired temperature (14-22°C) until the desired analysis stage [3].

- Validation of Targeting: At tailbud stages (e.g., NF 38-40), visualize the lineage tracer fluorescence using a fluorescence microscope. Successful targeting of the pronephros will show fluorescence in the bilateral tubules located along the trunk [3].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess the effects of your manipulation (e.g., morpholino knockdown) on pronephric development using whole-mount immunostaining with pronephros-specific antibodies and compare to the contralateral, uninjected side as an internal control [3].

Critical Signaling Pathways in Early Patterning

The cell fate decisions during early Xenopus development are directed by conserved signaling pathways. Key pathways active during the blastula and gastrula stages include BMP, Wnt, and Nodal/FGF signaling, which establish the dorsal-ventral and anterior-posterior axes. The following diagram summarizes the logical relationships of these key pathways in establishing the primary body axes.

Mastering the detailed staging and microinjection protocols for early Xenopus embryogenesis is a fundamental skill for researchers utilizing this powerful model system. The integration of the updated Normal Table of development with refined targeted microinjection techniques enables precise spatial and temporal control over gene expression. This precision, in turn, facilitates robust modeling of human genetic diseases, high-throughput drug screening, and the dissection of core conserved signaling pathways that govern vertebrate development. By adhering to these standardized application notes and protocols, researchers can ensure the reproducibility and reliability of their microinjection-based experiments in Xenopus.

Step-by-Step Microinjection Protocols: From Embryo Preparation to Targeted Tissue Delivery

Embryo Collection, Fertilization, and Jelly Coat Removal (Dejellying)

Within the field of developmental biology and biomedical research, the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis stands as a fundamental model organism. Its externally developing embryos, large size, and capacity for high-throughput experimentation make it an indispensable system for studying gene function, cell signaling, and organogenesis. A critical foundation for many advanced techniques, including microinjection for gene overexpression or knockdown, is the consistent production of high-quality, synchronously developing embryos. This application note details the essential upstream protocols for the robust generation and preparation of Xenopus embryos, framing them within the context of a broader research workflow centered on microinjection techniques. The successful execution of embryo collection, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and jelly coat removal is a prerequisite for ensuring that subsequent experimental manipulations yield reliable and interpretable data for researchers and drug development professionals.

The process of preparing Xenopus laevis embryos for microinjection and other analyses is a multi-stage workflow, beginning with animal husbandry and concluding with de-jellied, synchronously developing embryos ready for experimentation. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points in this process.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents and their specific functions in the embryo preparation protocol. Accurate preparation of these solutions is critical for experimental success.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Xenopus Embryo Collection and Preparation

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Details & Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) | Induction of ovulation in females and mating behavior in males [26]. | Typically used at 1000 U/mL stock concentration; administered via subcutaneous injection into the dorsal lymph sac [26]. |

| Marc's Modified Ringer's (MMR) | Embryo culture medium post-fertilization and dejellying [27] [26]. | 1x MMR: 0.1 M NaCl, 2.0 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO(4), 2 mM CaCl(2), 5 mM HEPES; pH 7.4-7.8 [27] [26]. Often used at 0.1x concentration for culturing embryos [27]. |

| L-Cysteine Dejelly Solution | Removal of the protective jelly coat surrounding the embryo [27] [26]. | 2% L-cysteine free base dissolved in 0.1x MMR; pH adjusted to 7.8-8.0 with NaOH [27] [26]. |

| Modified Barth's Saline (MBS) | Oocyte culture and storage [27] [28]. | 1x MBS: 88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.82 mM MgSO(4), 0.33 mM Ca(NO(3))(2), 0.41 mM CaCl(2), 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 [27] [29]. |

| Gentamicin Reagent | Antibiotic to prevent bacterial contamination in embryo cultures [26]. | Used as a 1000x stock solution (10 mg/mL) in culture media [26]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Hormone-Induced Embryo Production

The reliable production of a large number of synchronous embryos is achieved through controlled hormonal induction.

- Animal Preparation and Priming: Sexually mature female frogs are identified by their larger, pear-shaped body and prominent cloacal labia, while males possess keratinized nuptial pads on their forearms [26]. Females receive a priming subcutaneous injection of Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin (PMSG) into the dorsal lymph sac roughly 72 hours before the planned experiment. This pre-stimulates the ovaries [26].

- Ovulation and Egg Collection: To induce ovulation, females receive a boosting injection of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) or ovine Luteinizing Hormone (oLH) in the evening [26]. Eggs are collected the following morning either by natural mating or, more commonly for IVF, by gently squeezing anesthetized females. Healthy eggs are yellowish and translucent [26] [30]. They should be collected in a dry Petri dish, as excess water can cause activation and swelling, preventing fertilization [30].

- Sperm Harvest and In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Sacrifice or anesthetize a male frog and surgically remove the testes, which appear as yellowish, bean-shaped organs. A small piece of testis (approximately 1/4 to 1/3) can be stored in a salt solution like Testes Storage Solution or 1x MMR at 4°C for up to 7-10 days, though fertilization efficiency declines over time [26] [3]. For IVF, macerate a small piece of testis directly over the collected eggs using forceps. Gently swirl the dish to ensure contact, then add a small amount of water or buffer to activate the sperm and initiate fertilization [3] [30].

Jelly Coat Removal (Dejellying)

The jelly coat is a viscous, protective layer that physically impedes microinjection and must be removed shortly after fertilization.

- Solution Preparation and Timing: Prepare a 2% L-cysteine solution in 0.1x MMR and adjust the pH to 8.0 with NaOH. This solution should be made fresh or used the same day [27] [26]. The dejellying process should begin once the jelly coats have fully expanded, typically a few minutes post-fertilization.

- Dejellying Process: Carefully pour off the fertilization medium and completely cover the embryos with the 2% cysteine solution. Gently swirl the dish for even exposure. Monitor the embryos closely; the jelly coat will dissolve, and the embryos will pack closely together, typically within 3-5 minutes [27].

- Rinsing and Post-Procedure Care: Immediately upon dejellyling, pour off the cysteine solution and rinse the embryos thoroughly with multiple washes of 0.1x MMR. It is critical to remove all traces of cysteine, as prolonged exposure is toxic to the embryos [27]. After the final rinse, culture the clean, de-jellied embryos in fresh 0.1x MMR until they reach the desired developmental stage for microinjection.

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Precise timing and resource planning are essential for efficient experimentation. The following tables provide key quantitative benchmarks.

Table 2: Key Temporal Metrics for Embryo Preparation Procedures

| Process Stage | Typical Duration | Key Indicators & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cysteine Dejellying | 3 - 5 minutes [27] | Embryos pack closely; avoid prolonged exposure. |

| Sperm Viability (Post-Harvest) | Up to 7 - 10 days [3] | Stored at 4°C in appropriate solution; efficiency declines over time. |

| Oocyte Refrigeration | Up to 1 week [29] | Stored in MBS + antibiotics at 4°C. |

| Development to 4-cell stage | ~4 hours [3] | When incubated at 16°C; useful for planning targeted injections. |

Table 3: Hormone and Reagent Formulations

| Hormone/Reagent | Typical Stock Concentration | Common Working Concentration/Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) | 1000 U/mL [26] | Administered via injection; exact dose is frog- and protocol-dependent. |

| L-Cysteine Dejelly Solution | 2% (w/v) [27] [26] | Used at full strength for dejellyling. |

| Gentamicin (Antibiotic) | 10 mg/mL [26] | Used as 1x (10 µg/mL) in culture media. |

Integration with Microinjection Workflow

The protocols described herein are the critical first steps in a pipeline designed for the functional genetic analysis of early vertebrate development. The successful output—synchronously developing, de-jellied embryos—is the direct input for microinjection. With the jelly coat removed, injection needles can easily penetrate the embryo's vitelline membrane and target specific blastomeres. Established fate maps for Xenopus laevis allow researchers to target injections to specific blastomeres at the 4-cell or 8-cell stage that are fated to give rise to particular tissues, such as the kidney (pronephros), thereby confining genetic manipulations to a specific lineage and reducing pleiotropic effects [3]. Following microinjection, these embryos can be cultured further and analyzed using a wide array of techniques, including immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, and live imaging, to assess the phenotypic outcomes of the experimental manipulation [27] [3]. Thus, mastery of these foundational embryo preparation techniques is a non-negotiable prerequisite for generating high-quality, reproducible data in Xenopus research.

Within the broader framework of a thesis on microinjection techniques for Xenopus embryo research, the preparation of injection materials represents a critical foundational step. The ability to precisely manipulate gene expression and track cell lineages has cemented Xenopus as a premier model for vertebrate developmental biology and drug discovery research [31] [3]. This protocol details the preparation of three essential reagent classes: synthetic mRNA for gain-of-function studies, Morpholino oligonucleotides for gene knockdown, and lineage tracers for fate mapping. Mastery of these techniques enables researchers to investigate gene function, model human diseases, and dissect signaling pathways in a physiologically relevant context.

Research Reagent Solutions: A Core Toolkit

The following table catalogues the essential reagents required for microinjection experiments in Xenopus embryos, along with their primary functions and applications.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Xenopus Microinjection Studies

| Reagent | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Synthetic mRNA | Mediates gain-of-function by overexpressing proteins; can express wild-type, mutant, or dominant-negative proteins to perturb biological processes [32]. |

| Morpholino (MO) Oligonucleotides | Mediates loss-of-function by knocking down protein levels; blocks translation or pre-mRNA splicing of specific targets without significant off-target effects [31] [33]. |

| Lineage Tracers | Marks injected cells and their descendants for fate mapping; includes fluorescent dextrans or mRNAs encoding fluorescent proteins to verify targeting and trace lineage [34] [3]. |

| Capped mRNA | Ensures efficient translation of synthetic mRNA in the embryo, critical for robust protein expression [32]. |

| Fluorescently Tagged Dextrans | Serves as a neutral, non-diffusible lineage tracer that is not diluted by cell division and is easily detected [34] [35]. |

Quantitative Profiles of Key Reagents

Understanding the scope and quantitative reliability of these reagents is vital for experimental design. The following table summarizes key data profiles from foundational studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Data Profiles for Injection Reagents and Applications

| Aspect | Quantitative Data |

|---|---|

| Proteomic Coverage | Nearly 4,000 proteins quantified during early Xenopus development, providing a comprehensive background for knockdown/overexpression studies [36]. |

| Morpholino Specificity | MOs can be designed to target either translational initiation (blocking protein production) or splice sites (disrupting mRNA processing) [31]. |

| Lineage Tracer Requirements | Tracers must be small enough to diffuse through the cytoplasm before cell division, yet large enough to avoid transfer to adjacent cells via gap junctions [34] [35]. |

| Embryo Synchronization | Development from 1-cell to 4-cell stage takes ~2 hours at 22°C and ~4 hours at 16°C, defining the time window for early injections [3]. |

Protocol: Preparation of Synthetic mRNA

Background and Principle

The injection of synthetic, in vitro-transcribed mRNA is a powerful gain-of-function approach that allows researchers to investigate the consequences of protein overexpression during early development [32]. This method is particularly suited for studying cell cycle regulation, checkpoints, and apoptosis [32]. The principle involves transcribing a plasmid DNA template containing the gene of interest to produce mRNA that is subsequently capped for efficient translation in the embryo.

Materials and Equipment

- Plasmid DNA Template: A plasmid containing the gene of interest downstream of a bacteriophage promoter (e.g., T3, T7, or SP6).

- In Vitro Transcription Kit: Commercial kits are available that provide the necessary RNA polymerase, nucleotides, and buffers.

- Capping Analog: Such as m7G(5')ppp(5')G to synthesize 5'-capped mRNA for stability and efficient translation.

- RNase-Free Reagents and Consumables: Including water, tubes, and pipette tips to prevent RNA degradation.

- Purification Kit: Phenol-chloroform extraction reagents or commercial spin columns for purifying the transcribed mRNA.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Linearize the Plasmid DNA: Digest the circular plasmid DNA template with a restriction enzyme that cuts downstream of the gene insert and the RNA polymerase promoter. Purity the linearized DNA to remove enzymes and buffers.

Set Up the Transcription Reaction: Combine the following components on ice in an RNase-free tube:

- 1 µg of linearized plasmid DNA template

- 2 µL of 10x Transcription Buffer

- 2 µL of 10x Cap/Nucleotide Mix (containing ATP, CTP, GTP, UTP, and the capping analog)

- 2 µL of RNA Polymerase (e.g., T7, SP6)

- RNase-free water to a final volume of 20 µL

Incubate the Reaction: Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 1-2 hours to allow for efficient RNA synthesis.

Remove DNA Template: Add 1 µL of DNase I (RNase-free) to the reaction and incubate for an additional 15 minutes at 37°C to digest the DNA template.

Purify the mRNA: Purify the transcribed mRNA using a phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation or a commercial RNA purification spin column. Elute the purified mRNA in RNase-free water.

Quality Control and Quantification: Measure the concentration of the mRNA using a spectrophotometer. Analyze the integrity of the mRNA by running a small aliquot on a denaturing agarose gel; a single, distinct band should be visible. Aliquot and store the mRNA at -80°C.

Troubleshooting and Notes

- A low yield of mRNA can result from incomplete linearization of the plasmid DNA or degradation of RNA components. Ensure the plasmid is completely linearized and use fresh, RNase-free reagents.

- The absence of a single band on a gel may indicate RNA degradation or the presence of truncated transcripts, which can be caused by RNase contamination or secondary structures in the template.

Protocol: Preparation of Morpholino Oligonucleotides

Background and Principle

Morpholino oligonucleotides are antisense tools that enable researchers to reduce the levels of a specific protein without major financial or temporal investments [31] [33]. Their utility in Xenopus is enhanced by the organism's rapidly developing, synchronized embryos [31]. MOs function by binding to complementary mRNA sequences, thereby preventing either translation initiation or pre-mRNA splicing, which ultimately abrogates the function of the target gene [31].

Materials and Equipment

- Morpholino Oligonucleotide: Designed to be complementary to the translation start site or a splice junction of the target mRNA.

- Nuclease-Free Water: For resuspension and dilution.

- Sterile Filters: For filtering solutions if necessary.

- Pipettes and Sterile Tips.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Reconstitution and Dilution:

- Centrifuge the lyophilized Morpholino tube briefly.

- Resuspend the Morpholino in nuclease-free water to create a stock solution (typically 1-5 mM).

- Gently vortex and incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to ensure complete dissolution.

- Prepare a working dilution in nuclease-free water based on the desired final injection concentration. A common working concentration is 200-500 µM.

Preparation for Injection:

- The Morpholino working solution can be mixed with a lineage tracer (e.g., fluorescent dextran) to identify successfully injected embryos [3].

- Centrifuge the injection solution briefly before loading it into the injection needle to pellet any particulate matter.

Troubleshooting and Notes

- Morpholinos are stable at room temperature for extended periods. Stock solutions can be stored at -20°C for long-term storage, but repeated freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided.

- A standard control is a standard control Morpholino provided by the manufacturer. The efficacy of a translation-blocking MO can be confirmed by western blot, while a splice-blocking MO can be validated by RT-PCR to detect mis-spliced transcripts [31].

Protocol: Preparation of Lineage Tracers

Background and Principle

Lineage tracing and fate mapping reveal the types of cells, tissues, and organs derived from specific embryonic cells [34] [35]. In Xenopus, intracellular injection of a lineage tracer into a single blastomere labels the injected cell and all its descendants [34] [3]. This is indispensable for verifying that targeted injections to specific blastomeres (e.g., those fated to form the kidney) are successful [3]. An ideal lineage tracer is neutral, non-diffusible to adjacent cells, not diluted by cell division, and easily detectable [34] [35].

Materials and Equipment

- Fluorescent Dextrans: Lysine-fixable, fluorescein (FITC) or tetramethylrhodamine-labeled dextrans (e.g., 10,000 MW).

- mRNA Encoding Fluorescent Proteins: Such as MEM-RFP mRNA for membrane-targeted red fluorescent protein [3].

- Nuclease-Free Water or Injection Buffer: For dilution.

- Pipettes and Sterile Tips.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Selection of Tracer:

- For short-term lineage tracing: Fluorescent dextrans are ideal as they are immediately visible after injection and do not require translation [34].

- For long-term lineage tracing: mRNA encoding a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP, RFP) is suitable, as the translated protein persists through later developmental stages [3].

Preparation of Fluorescent Dextran Solution:

- Prepare a working solution of the fluorescent dextran in nuclease-free water or a suitable injection buffer. A concentration of 5-10 mg/mL is commonly used.

- Centrifuge the solution before loading into the needle.

Preparation of Fluorescent Protein mRNA:

- Prepare the synthetic mRNA encoding the fluorescent protein as described in Section 4.

- Dilute the mRNA to the desired working concentration (typically 50-200 pg/nL) in nuclease-free water.

Troubleshooting and Notes

- Fluorescent dextrans provide immediate feedback but may fade over time. Fluorescent proteins encoded by mRNA require time for translation and folding but offer sustained expression.

- Tracers are often co-injected with the experimental reagent (e.g., MO or mRNA) to confirm the site of injection and the contribution of the injected blastomere to developing tissues [3].

Integrated Experimental Workflow and Targeting Strategy

The prepared reagents are deployed within a coherent experimental workflow that leverages the well-defined fate maps of Xenopus embryos. The integration of reagent preparation with precise embryonic targeting is what enables high-quality, interpretable data.

Targeted Microinjection Using Fate Maps

- Blastomere Identification: For 4-cell embryos, the ventral blastomeres (large, dark cells) contribute significantly to the developing kidney and other ventral tissues. To target the left kidney, inject the left ventral blastomere [3].

- Higher Resolution Targeting: For 8-cell embryos, the ventral, vegetal blastomeres (V2) provide the greatest contribution to the kidney. The V2.2 blastomere at the 16-cell stage and the V2.2.2 (also known as C3) blastomere at the 32-cell stage provide even more precise targeting [3].

- Temperature Control: Slow embryonic development by incubating at 14-16°C to extend the time window available for injections at the 4-, 8-, and 16-cell stages [3].

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The meticulous preparation of mRNA, Morpholinos, and lineage tracers is a prerequisite for successful microinjection experiments in Xenopus embryos. When combined with the powerful approach of targeted blastomere injection guided by established fate maps, these reagents enable precise functional tests of genes in vertebrate development and disease. This protocol provides a reliable foundation for researchers to generate high-quality data, contributing to the advancement of developmental biology and biomedical research.

Standard Cytoplasmic Injection Technique in Single-Cell Embryos

Cytoplasmic microinjection in one-cell embryos is a foundational technique for delivering solutions such as genome editing tools, siRNA, mRNAs, or blocking antibodies directly into the zygotic cytoplasm. When applied to Xenopus research, this technique enables the study of gene function during early development and the generation of gene-edited animal models. The standard technique involves directly penetrating the plasma membrane with a sharp micropipette; however, the application of this method to non-rodent species, including Xenopus, presents specific challenges such as cytoplasmic darkness and membrane elasticity, necessitating protocol adaptations [37] [3]. This application note details a robust cytoplasmic microinjection protocol optimized for species with challenging embryo characteristics, framing it within the broader context of microinjection techniques for Xenopus embryo research.

Key Reagents and Equipment

The following tools and reagents are essential for successfully performing cytoplasmic microinjection.

Table 1: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment for Cytoplasmic Microinjection

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Micropipette Puller | Required to produce injection and holding pipettes with specific tip geometries (e.g., long taper, 5 µm inner diameter for injection needles) [37]. |

| Microforge | Used for precisely breaking and polishing pipette tips to create blunt ends and desired angles (e.g., ~30°) [37]. |

| Micromanipulators | Motorized manipulators (e.g., Eppendorf TransferMan 4r) allow for precise, vibration-free control of pipettes in three dimensions. The ability to store positions streamlines the workflow [38]. |

| Microinjectors | Programmable injectors (e.g., FemtoJet) manage injection pressure (pi) and compensation pressure (pc) for consistent delivery. Continuous flow mode is often recommended [38]. |

| Injection Chamber | Provides a microenvironment for the embryo during the procedure. A common setup involves a drop of medium (e.g., M2 or SOF-HEPES with 20% FBS) covered with mineral oil on a coverslip [37] [38]. |

| Borosilicate Glass Capillaries | Standard material for fabricating micropipettes (e.g., 1.0 mm outer diameter, 0.75 mm inner diameter) [37]. |

| Lineage Tracers | Fluorescent dextrans or mRNA encoding fluorescent proteins (e.g., MEM-RFP) are co-injected to verify the site of injection and track the progeny of the injected cell [3]. |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 components (e.g., Cas9 protein or mRNA and sgRNA) are prepared in injection buffer for targeted genetic modifications [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Micropipette Preparation

Injection Micropipette:

- Pulling: Place a borosilicate glass capillary in a micropipette puller. Use a program that produces a thin tip with a long taper (e.g., Heat: 825; Pull: 30; Velocity: 120; Time: 200; Pressure: 500) [37].

- Blunt-End Creation: Place the pulled pipette on a microforge. Bring the pipette to the filament at the point where the inner diameter is approximately 5 µm. Briefly activate the heater at ~45% power to melt and break the pipette, creating a straight, blunt tip [37].

- Angle Bending: Reposition the pipette about 10 µm from the filament and set the microforge temperature to ~60%. Activate the heater to bend the pipette, creating an approximately 30° angle near the tip. This ensures the tip is parallel to the injection dish surface during operation [37].

Holding Micropipette:

- Pulling: Use a program on the puller that creates a tip with a long, even taper and parallel walls (e.g., Heat: 815; Pull: 20; Velocity: 140; Time: 175; Pressure: 200) [37].

- Breaking and Polishing: Score the pipette at a diameter of 180 µm and break it for a straight cut. Fire-polish the tip on the microforge to achieve an inner diameter of ~40 µm [37].

- Angle Bending: Similar to the injection pipette, bend the holding pipette to create a 30° angle about 5 mm from the tip [37].

Embryo Preparation and Targeting inXenopus

- Embryo Generation: Obtain eggs and fertilize them in vitro using standard protocols for Xenopus [3].

- Dejellying: Remove the protective vitelline membrane by treating embryos with a 2% cysteine solution (pH 8.0) [3].

- Temperature Control: Regulate developmental temperature tightly. For injections at the 4- or 8-cell stage, incubate embryos at cooler temperatures (14-16 °C) to slow the cell cycle and provide more time for the procedure [3].

- Blastomere Targeting: Utilize the established Xenopus fate maps to target the blastomere that gives rise to the tissue of interest, such as the pronephros (kidney) [3].

- For a 4-cell embryo, the ventral blastomeres (larger, darker cells) contribute significantly to the developing kidney. Inject the left ventral blastomere to target the left kidney [3].

- For an 8-cell embryo, the ventral, vegetal blastomeres (V2) are the primary contributors. Inject the left V2 blastomere to target the left kidney [3].

Workstation Setup and Microinjection Procedure

- System Preparation: Ensure microinjectors are loaded with oil and free of air bubbles. Insert the holding and injection pipettes into their respective micromanipulators. Allow oil to enter the pipettes by capillary action and check for proper fluid movement [37].

- Injection Dish Preparation: Place a 50 µL drop of warmed injection medium (e.g., SOF-HEPES + 20% FBS) in the center of a dish lid. Place a 1-2 µL drop of the solution to be injected nearby. Cover all drops with ~10 mL of mineral oil to prevent evaporation [37].

- Loading Embryos: Transfer about 20-30 zygotes or staged embryos into the injection drop using a microdispenser [37].

- Cytoplasmic Injection: The following procedure, adapted from livestock zygotes, is effective for embryos with dark cytoplasm and elastic membranes [37].

- Use a laser to create an opening in the zona pellucida (if present). This step reduces mechanical stress on the embryo.

- Introduce the blunt-end injection pipette through the laser opening and advance it until the tip is positioned about three-fourths of the way across the embryo.

- Break the plasma membrane by gently aspirating a small amount of cytoplasmic content into the needle.

- Inject the aspirated cytoplasm followed by the solution of interest (e.g., CRISPR mix, morpholino, lineage tracer) back into the embryonic cytoplasm.

- Post-Injection Recovery: After injection, add a buffer solution to the embryo. Once the embryo becomes active again (typically within 2-5 minutes), transfer it to a fresh culture plate for regular cultivation [23].

Quantitative Injection Parameters

The table below summarizes key quantitative data for preparing injection mixes for genome editing in model organisms, which can serve as a reference for Xenopus studies.

Table 2: Genome Editing Reagent Concentrations for Embryo Microinjection

| Component | Organism | Stock Concentration (ng/µL) | Final Concentration (ng/µL) | Injection Buffer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 mRNA | Mouse | 1,000 | 100 | T10E0.1 |

| sgRNA | Mouse | 250 | 50 | T10E0.1 |

| Cas9 Protein | Mouse | 3,000 | 300 | T10E0.1 |

| sgRNA (each) | Mouse | 250 | 112.5 | T10E0.1 |

| Cas9 Protein | Zebrafish | 3,000 | 600 | T10E0.1 |

| sgRNA | Zebrafish | 1,500 | 200 | T10E0.1 |

Data sourced from demonstrated protocols for mouse and zebrafish [39]. Volumes are typically scaled to a total volume of 5-10 µL for the injection mix.

Workflow and Data Analysis Visualization

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for targeted cytoplasmic microinjection in Xenopus embryos, from preparation to analysis.

Critical Factors for Success

- Needle Quality: The injection needle must have a blunt tip and the correct inner diameter (~5 µm) to facilitate membrane aspiration without causing lysis. A needle that is too wide increases embryo death, while one that is too thin may clog [37] [23].

- Cytoplasmic Maturity: The cytoplasmic viscosity of the oocyte/zygote, indicative of maturity, can significantly influence injection dynamics. Metaphase II (MII) oocytes typically have more viscous cytoplasm, which can facilitate a more controlled injection process [40].

- Injection Solution Purity: The DNA or RNA solution must be pure and well-mixed to prevent needle clogs. High concentrations of DNA can be toxic and lead to unintended gene overexpression or embryo death [23].

- Developmental Control: When targeting a specific tissue (e.g., the left kidney), the non-injected contralateral side (e.g., the right kidney) serves as a perfect internal control for assessing the effects of the manipulation [3].

Targeted microinjection in Xenopus embryos is a powerful technique for investigating gene function during early vertebrate development. By leveraging well-established cell fate maps, researchers can deliver reagents—such as morpholinos for gene knockdown or mRNA for overexpression—specifically into blastomeres that are the progenitors of particular organs, like the kidney (pronephros) [41] [3]. This approach restricts genetic manipulations to a specific tissue, reducing pleiotropic effects in the rest of the embryo and allowing the contralateral side to serve as an internal control [41]. This protocol details the methodology for utilizing fate maps to perform targeted microinjection into specific blastomeres of 4-cell and 8-cell stage Xenopus laevis embryos to study the developing pronephros, a simple model for kidney disease [41].

Blastomere Selection and Fate Mapping

The first and most critical step is the accurate identification of the correct blastomere to inject, based on established fate maps available through resources like Xenbase [41] [28].

- 4-Cell Embryos: The second cleavage divides the embryo into dorsal and ventral halves. The ventral blastomeres (V) are larger and darker than the dorsal (D) ones and contribute more significantly to the developing pronephros [41]. To target the left kidney, inject the left ventral blastomere [41].

- 8-Cell Embryos: The third cleavage bisects the animal and vegetal poles. The ventral, vegetal blastomeres (V2) provide the highest contribution to the pronephros at this stage [41]. To target the left kidney, inject the left V2 blastomere [41].

- Later Stages: For even greater precision, injections can be targeted to the V2.2 blastomere at the 16-cell stage or the V2.2.2 (also known as C3) blastomere at the 32-cell stage, which contributes the most cells to the pronephros [41].

The following diagram illustrates the key blastomeres to target at the 4-cell and 8-cell stages for pronephros studies.

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and materials required for this protocol [41] [3].

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Dejelly Solution (2% cysteine, pH 8.0) | Removes the protective vitelline envelope from the embryos to facilitate microinjection and visualization. |

| MEM-RFP mRNA (or other fluorescent protein mRNA) | Serves as a lineage tracer; its expression verifies successful targeting and shows descendant cells [41]. |

| Morpholinos or mRNA of Interest | The primary experimental reagents for knocking down or overexpressing genes, respectively [41]. |

| Testes Storage Solution (1x MMR, BSA, gentamycin) | Medium for storing isolated male testes used for in vitro fertilization of eggs [41]. |

| Marc’s Modified Ringer’s (MMR) | A standard saline solution for raising and maintaining Xenopus embryos. |

| Fixative (e.g., 4% PFA) | For fixing embryos at desired stages for subsequent immunostaining. |

| Primary and Secondary Antibodies | For whole-mount immunostaining to visualize pronephric tubules and assess development [41]. |

Experimental Protocol

The entire experimental procedure, from embryo preparation to final analysis, is outlined below.

Part 1: Embryo Preparation and Blastomere Identification

- Prepare Embryos: Generate embryos by in vitro fertilization according to standard protocols [41]. Once fertilized, remove the jelly coat by treating embryos with Dejelly Solution (2% cysteine, pH 8.0) for 2-5 minutes with gentle agitation. Wash the embryos thoroughly with 1/3x MMR [41].

- Control Developmental Rate: Transfer the dejellied embryos to incubation chambers containing 1/3x MMR. Maintain a temperature of 14-16°C to slow the rate of development. This provides a longer window for performing injections at the 4-cell and 8-cell stages before the embryos progress to the next cleavage [41] [3].

- Identify Blastomeres: Under a dissecting microscope, use the pigmentation and size of the blastomeres to orient the embryo. Refer to the fate maps and the guidelines in the "Blastomere Selection" section above to identify the correct target blastomere (e.g., left ventral for 4-cell; left V2 for 8-cell) [41].

Part 2: Microinjection Procedure

- Prepare Injection Needles and Mix: Pull glass capillary needles to a fine point. Backfill a needle with your injection mix. A typical mix includes the experimental reagent (morpholino or mRNA) co-injected with a lineage tracer (e.g., 50-100 pg of MEM-RFP mRNA) to mark the injected cells and their progeny [41] [15].

- Perform Microinjection: Calibrate the injection volume (typically 5-10 nL per blastomere at the 4-8 cell stages). Position the embryo using forceps and gently pierce the target blastomere with the needle. Deliver the solution into the cytoplasm. The lineage tracer in the mix allows for immediate visual confirmation of a successful injection [41].

- Post-Injection Care: After injection, return the embryos to the 14-16°C incubator and allow them to develop until the desired stage for analysis [41].

Part 3: Validation and Analysis

- Verify Targeting: Once embryos reach tailbud stages (e.g., stage 28+), visualize the lineage tracer (e.g., RFP fluorescence) using a fluorescence stereomicroscope. Successful targeting of the pronephros will show fluorescence in the vicinity of the developing tubules on the injected side [41] [15].

- Whole-Mount Immunostaining: To assess pronephric morphology and development, fix stage 38-40 embryos and perform whole-mount immunostaining using antibodies against pronephric tubule proteins (e.g., 3G8, 4A6) [41].

- Imaging and Scoring: Image the immunostained or live embryos using a compound microscope or confocal microscope [15]. The pronephric development on the injected side can be scored against the uninjected contralateral side, and a pronephric index can be calculated to quantify the effect of the genetic manipulation [41].

Quantitative Data and Timing

Precise timing is critical for successfully targeting the correct blastomeres. The following table summarizes key developmental timelines at different temperatures [41] [3].

| Developmental Event | Approx. Time at 22°C | Approx. Time at 16°C | Importance for Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-cell to 4-cell (Stage 3) | ~2 hours | ~4 hours | Slower development at 16°C provides a larger window for preparation. |

| 4-cell to 8-cell (Stage 4) | ~15 minutes | ~30 minutes | The primary window for 8-cell stage injections. |

| 8-cell to 16-cell (Stage 5) | ~30 minutes | ~45 minutes | The window for more precise 16-cell stage injections. |

| Target Analysis Stage | Stage 38-40 | Stage 38-40 | Stage when the pronephros is fully formed and can be analyzed. |

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Temperature Control is Critical: The rate of Xenopus development is highly temperature-dependent. Using a cooler incubation temperature (14-16°C) is strongly recommended to provide sufficient time for injections at the 8-cell stage [41] [3].