Morphogen Gradient Formation and Interpretation: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Applications in Drug Development

This article synthesizes contemporary research on morphogen gradient formation and interpretation, addressing both foundational biological mechanisms and their translational applications.

Morphogen Gradient Formation and Interpretation: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on morphogen gradient formation and interpretation, addressing both foundational biological mechanisms and their translational applications. We explore the core biophysical principles—including diffusion, degradation, and endocytic trafficking—that govern gradient establishment, alongside the intracellular networks that enable precise signal interpretation. The review highlights how advanced model systems, such as organoids and synthetic biology circuits, are revolutionizing our ability to study and engineer morphogen-mediated patterning. We further examine the critical challenges of reproducibility, scalability, and precision in these systems, and discuss how integrating computational modeling, single-cell analytics, and standardized bioengineering is enhancing their predictive power for therapeutic development. Finally, the article evaluates the growing role of morphogen-informed models in preclinical drug screening and their emerging potential to reshape regenerative medicine and precision oncology.

Core Principles and Current Controversies in Morphogen Gradient Biology

The development of a complex multicellular organism from a single fertilized egg represents one of the most fascinating questions in biology. How embryonic tissues organize in space and time to form fields of distinct cells reliably has fascinated developmental biologists for decades [1]. The conceptual framework for understanding this process was fundamentally shaped by two pivotal theoretical advances: Francis Crick's physical analysis of diffusion-based gradient formation and Lewis Wolpert's elegant concept of positional information. These frameworks, developed within the broader context of morphogen gradient research, provide the foundational principles for how patterns emerge during embryonic development. The core premise is that positional information enables cells to determine their spatial location within a developing tissue and adopt specific fates accordingly [2] [1]. This whitepaper traces the evolution of these theoretical frameworks, their experimental validation, and their modern interpretation through quantitative systems-level approaches, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide to the field.

The history of gradient theories dates back to early 20th century proposals of "formative substances" or metabolic gradients that could influence developmental plans [2] [3]. However, the first rigorous mathematical treatment was provided by Alan Turing in 1952 with his reaction-diffusion model, which showed how chemical substances he termed "morphogens" could self-organize into spatial patterns from homogeneous initial conditions [3]. This was followed by Crick's explicit analysis of diffusion as a physical mechanism for gradient formation and Wolpert's powerful abstraction of positional information, which together established a theoretical triad that continues to guide experimental and computational approaches in developmental biology and regenerative medicine.

Crick's Diffusion Model: The Biophysical Foundation

Theoretical Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Francis Crick's 1970 model provided a critical biophysical foundation for understanding how morphogen gradients could form in developing tissues [3]. Crick recognized that freely diffusing morphogen produced in a source cell and destroyed in a spatially distinct "sink" could establish a concentration gradient over developmentally relevant timescales. His key insight was that a localized sink was not strictly necessary—gradients can form if all cells act as sinks through uniform degradation, or even if morphogen is not degraded at all [3].

The fundamental mathematical description of morphogen spreading through non-directional movement with spatially uniform degradation can be captured by a partial differential equation that has become central to the field:

Where c represents morphogen concentration as a function of space and time, D is the effective diffusion coefficient [μm²/s], and k is the effective degradation rate [1/s] [3]. The first term on the right describes diffusion-driven spreading, while the second term represents first-order degradation. At steady state (when ∂c/∂t = 0), this equation yields an exponential concentration profile characterized by a specific characteristic length λ = √(D/k), which determines how far the morphogen signal extends from its source [1] [3].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Crick's Diffusion Model

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Biological Role | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | μm²/s | Determines speed of morphogen spread | FRAP, FCS |

| Degradation Rate | k | s⁻¹ | Controls gradient length and turnover | Metabolic labeling, pulse-chase |

| Characteristic Length | λ = √(D/k) | μm | Spatial range of morphogen action | Immunostaining, live imaging |

| Source Strength | j₀ | molecules/(μm²×s) | Production rate at source | Quantified imaging, biosensors |

Boundary Conditions and Tissue Context

Crick's model explicitly considered boundary conditions that reflect biological reality. At the source boundary (x = 0), a constant flux of molecules enters the target tissue: D(∂c/∂x)|ₓ₌₀ = -j₀, where j₀ represents the source strength [3]. At the opposite tissue boundary (x = L), a reflective condition where (∂c/∂x)|ₓ₌ₗ = 0 assumes molecules cannot diffuse out of the tissue. The model elegantly demonstrates that the steady-state gradient shape depends solely on the ratio D/k, while the transient dynamics toward this steady state depend on D independently [1]. This separation of timescales has profound implications for developmental processes, particularly in rapidly patterning systems.

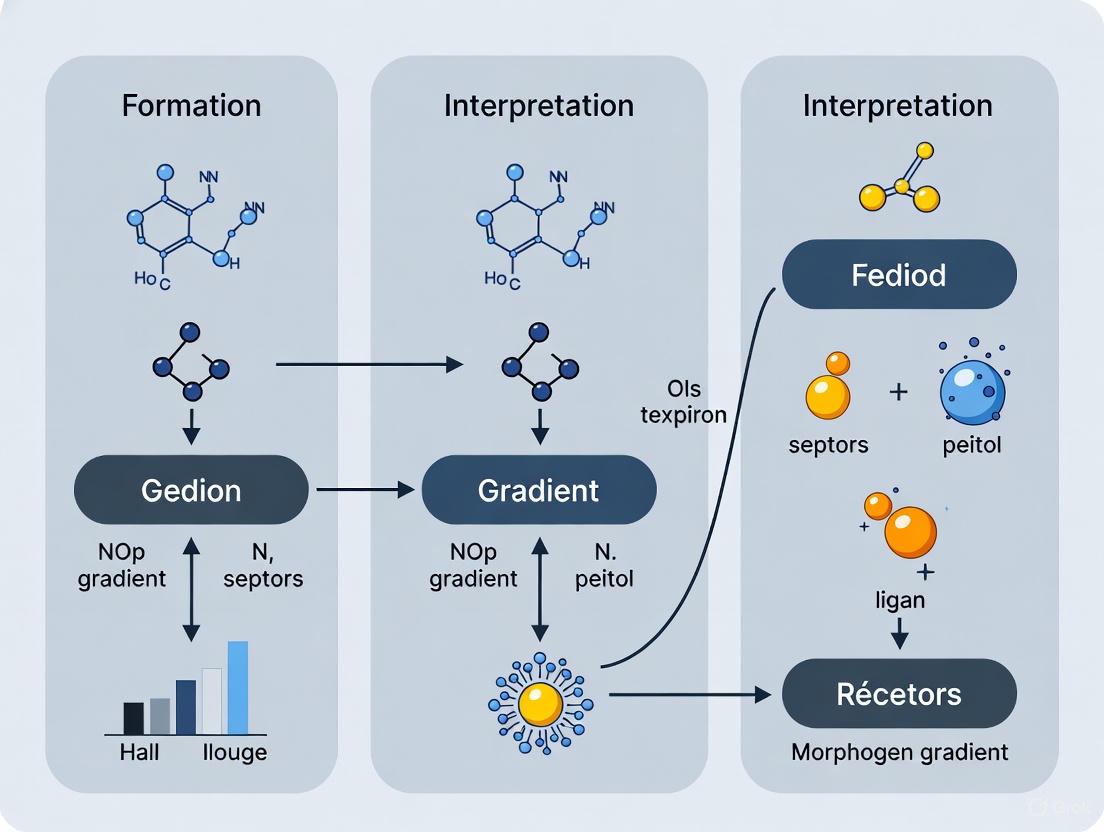

Figure 1: Crick's diffusion model for morphogen gradient formation

Wolpert's Positional Information: The French Flag Model

Core Conceptual Framework

Lewis Wolpert's seminal 1969 positional information model represented a paradigm shift in how developmental biologists conceptualized patterning [2] [1]. Wolpert elegantly postulated that cells determine their fate by interpreting local concentrations of graded morphogen profiles, abstractly termed positional information [2]. This framework provided a solution to his famous "French Flag Problem" of patterning, wherein a field of initially identical cells develops into precisely positioned blue, white, and red regions [2].

The French Flag model operates through several key principles. First, a prepatterned source establishes a morphogen gradient through a tissue. Second, cells respond to this gradient by interpreting local morphogen concentrations against predefined threshold values. Third, each concentration threshold triggers a specific genetic response, leading to discrete boundaries between cell fates despite the continuous nature of the gradient [2]. Wolpert's crucial insight was separating the "information" contained in the morphogen concentration from the "interpretation" machinery that converts this information into cellular responses—a distinction that allowed evolution to act independently on signaling and response mechanisms [2].

Experimental Validation and Molecular Proof

While Wolpert's conceptual framework found immediate popularity, its experimental validation required significant time. In 1974, transplantation experiments in Drosophila definitively demonstrated the existence of cytoplasmic determinants [2]. The watershed moment came in 1988 with the discovery of the anterior determinant Bicoid in the Drosophila embryo, which displayed all the characteristics of Wolpert's positional information concept [2] [1]. Bicoid forms a concentration gradient along the anterior-posterior axis, with different concentrations activating or repressing specific target genes to establish the body plan [1]. This was quickly followed by demonstrations that frog growth factors determine differential cell fates according to concentration thresholds [2], establishing Wolpert's framework as a universal mechanism operating across diverse organisms.

Figure 2: Wolpert's French Flag model of positional information

Shannon Information Theory in Positional Specification

The modern interpretation of positional information has shifted from qualitative description to quantitative, mathematically rigorous formulation based on Shannon information theory [2]. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in morphogen-mediated patterning: the inherently stochastic nature of the mapping between physical position and local morphogen concentrations. Mutual information, I(X;Y) = S(X) + S(Y) - S(X,Y), provides a model-free measure of the statistical dependence between position and morphogen concentration, generalizing linear correlation coefficients to capture nonlinear relationships [2].

This information-theoretic framework enables researchers to answer fundamental systems-level questions: where does positional information reside in the patterning network, how is it transformed and accessed during development, and what fundamental limits is it subject to? [2]. The shift to information theory moves focus beyond specific biological mechanisms, molecules, genes, and pathways to reveal general principles governing the reliability of positional specification despite molecular noise.

Precision and Reproducibility in Developmental Patterning

Quantitative studies have revealed that specific morphological features during early development occur with remarkable precision and reproducibility across wild-type embryos [2]. The Bicoid gradient in Drosophila, for instance, patterns the embryo with characteristic lengths of approximately 100 μm, significantly larger than the Dpp (20 μm) and Wingless (6 μm) gradients in the fly wing [1]. This precision exists despite the stochastic nature of individual morphogen-receptor interactions and intracellular signaling events.

Table 2: Experimentally Characterized Morphogen Gradients

| Morphogen | System | Characteristic Length | Formation Mechanism | Target Genes/Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicoid | Drosophila embryo | ~100 μm | Diffusion & degradation [1] | Gap genes (hunchback, Krüppel) [1] |

| Dpp | Drosophila wing | ~20 μm | Diffusion & degradation [1] | Optomotor-blind, Spalt [1] |

| Wingless | Drosophila wing | ~6 μm | Diffusion & degradation [1] | Distal-less, Senseless [1] |

| BMP | Drosophila embryo | ~5 cells | Extracellular interactions [1] | pMad gradient, dorsal fates [1] |

| Sonic Hedgehog | Mouse neural tube | Tissue-scale | Co-expanding source [4] | Neural progenitor domains [4] |

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Key Experimental Protocols for Gradient Analysis

The validation and quantification of morphogen gradients require sophisticated experimental approaches. Immunostaining and GFP fusion proteins provide static images of gradient profiles in fixed tissues [1]. For dynamic measurements, functional fluorescent protein-morphogen fusions enable live imaging of gradient formation and turnover [1]. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments yield quantitative data on diffusion coefficients by measuring how quickly fluorescence returns to a photobleached region [3].

Critical tests for morphogen function involve altering gradient shape through genetic manipulation and observing resulting changes in patterning outcomes. As expected for true morphogens, changes in Bicoid concentration elicit corresponding shifts in the expression domains of downstream target gap genes [1]. Similar approaches using inducible expression systems, morpholino knockdowns, or pharmacological inhibitors have been applied across model systems to establish causal relationships between gradient properties and patterning outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Morphogen Gradient Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Fusions | Bicoid-GFP, Dpp-GFP | Live imaging of gradient dynamics | [1] |

| Antibodies for Immunostaining | Anti-Bicoid, Anti-pMad | Fixed tissue gradient visualization | [1] [3] |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, RNAi, Gal4/UAS | Perturbation of gradient formation | [1] |

| Biosensors | FRET-based BMP sensors | Real-time signaling activity monitoring | [1] |

| Theoretical Modeling Tools | Reaction-diffusion solvers | Quantitative simulation of gradient dynamics | [2] [3] |

Advanced Concepts: Temporal Control and System-Level Properties

Beyond Position: Morphogen Gradients as Temporal Regulators

Recent research has revealed that morphogen gradients convey more than just spatial information—they can also orchestrate developmental timing [4]. In growing tissues such as the mouse neural tube, the same Sonic Hedgehog gradients that convey positional information can simultaneously enable cells to measure time [4]. The key mechanism involves a passively co-expanding morphogen source, which creates a hump-shaped transient signal as morphogen abundance first increases then decreases due to tissue growth [4].

This temporal dimension adds considerable sophistication to the French Flag model. In the developing neural tube, opposing gradients of Sonic Hedgehog and BMP signaling not only pattern spatial domains but can also synchronize developmental time across the entire tissue [4]. This dual functionality demonstrates how the same molecular machinery can solve multiple patterning challenges simultaneously through sophisticated dynamics.

Future Directions: Unsolved Puzzles in Gradient Biology

Despite significant advances, fundamental questions about morphogen gradients remain unanswered. The field continues to investigate how the precision and robustness of gradients emerge from stochastic molecular interactions [2]. The interplay between gradient formation and interpretation represents another frontier—in many systems, these processes may influence each other through mutual feedback loops rather than operating in linear sequence [1]. Understanding this interplay requires system-level approaches that combine quantitative experiments with theoretical modeling [1].

Future research must also address how gradients pattern tissues across different scales and how they integrate with other patterning mechanisms such as cell-cell communication and mechanical forces. The application of information theory to positional specification represents a promising framework for addressing these questions by providing model-free measures of patterning performance [2]. As techniques for quantitative measurement and perturbation continue to advance, so too will our understanding of these fundamental mechanisms of biological pattern formation.

Morphogen gradients are fundamental to patterning and growth in developing tissues, providing positional information through differential concentration-dependent signaling. The establishment, interpretation, and maintenance of these gradients rely on a complex interplay of biophysical transport mechanisms and biochemical processing. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core mechanisms—diffusion, degradation, and extracellular regulation—that collaboratively shape morphogen distribution and signaling dynamics. We synthesize current research frameworks, highlighting how endocytic trafficking critically interprets the extracellular morphogen gradient by controlling signaling duration, while extracellular modulation fine-tunes ligand availability and distribution. Quantitative data from foundational studies are consolidated into structured tables, and detailed experimental protocols are provided for key methodologies. Visual signaling pathways and workflows, generated using compliant Graphviz specifications, enhance conceptual clarity. This resource aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive mechanistic understanding essential for investigating gradient-dependent processes in development and disease contexts.

Morphogens are signaling molecules released from localized source cells that form concentration gradients across developmental fields, instructing cell fate in a concentration-dependent manner [5]. The paradigm of morphogen-mediated patterning hinges on the precise formation and interpretation of these gradients, which dictate distinct transcriptional responses based on threshold concentrations [6]. The gradient is not a static entity but a dynamic system shaped by the rates of morphogen production, dispersion from the source, and eventual turnover.

The core thesis of contemporary research posits that the interpretation of the morphogen gradient is as critical as its physical establishment. This interpretation is highly context-dependent, determined by the specific competence of the receiving cells—defined by their gene expression profile, available transcription factors, and epigenetic landscape [6]. Furthermore, it has become clear that cells interpret not only the level of morphogen but also the duration of signaling exposure [6] [7]. Thus, understanding gradient formation requires dissecting the transport mechanisms that govern its spatial distribution and the cellular mechanisms that decode its informational content.

Core Transport Mechanisms and Their Regulation

The formation of a stable morphogen gradient is a physical process governed by the relationship between diffusion, which spreads the molecule, and degradation, which limits its range. These core mechanisms are further modulated by a suite of extracellular factors.

Diffusion

Diffusion is the passive, thermally driven process that enables morphogens to spread from a local source, forming a concentration gradient. This movement is governed by Fick's laws, leading to a concentration that typically decays exponentially from the source. The effective range of the morphogen is determined by the diffusion coefficient (D) and the degradation rate (k). Recent studies, particularly on the Dpp morphogen in Drosophila, highlight that simple free diffusion is often insufficient to explain gradient dynamics in vivo. Instead, Dynamin-mediated internalization is crucial for shaping the extracellular distribution, as blocking this process expands the range of extracellular Dpp [7].

Degradation and Intracellular Trafficking

Morphogen degradation is essential for establishing a finite gradient and preventing uncontrolled signaling. The intracellular trafficking pathway is a key determinant of the signaling duration and, consequently, the interpretation of the gradient.

- Signal Initiation: Dpp signaling activation depends on Dynamin-mediated internalization from the cell surface [7].

- Signal Attenuation: Contrary to some models, Rab5-mediated early endosomal trafficking is dispensable for signaling initiation but required for its termination by promoting the downregulation of activated Thickveins (Tkv) receptors [7].

- Signal Termination: The Multivesicular Body (MVB) serves as a critical compartment for terminating Dpp signaling. The ESCRT complex sorts activated receptors into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) for degradation. Blocking MVB formation expands the intracellular Dpp signaling gradient without altering the extracellular distribution, demonstrating that this step is vital for accurately interpreting the extracellular gradient [7]. Rab7-mediated lysosomal degradation appears to be a subsequent step for terminal degradation.

Extracellular Regulation

The extracellular space is not a passive medium but is actively involved in modulating morphogen movement and stability.

- Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs): Proteins like Dally can bind morphogens, influencing their stability, diffusion, and presentation to signaling receptors. They can antagonize Tkv-mediated endocytosis, thereby promoting a longer-range gradient [7].

- Receptor-Mediated Sequestration: Cell-surface receptors, such as Tkv for Dpp, act as a sink for morphogens. Their binding can limit spread and facilitate internalization, a process described as "restricted diffusion" or "transcytosis" in some models [7].

Table 1: Key Morphogens and Their Associated Transport Mechanisms

| Morphogen | Organism | Core Transport Mechanism | Key Regulatory Factors | Primary Role in Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dpp/BMP | Drosophila | Diffusion & Endocytic Trafficking | Tkv, Punt, Dally, Dynamin, Rab5, ESCRT | Wing disc patterning and growth [7] |

| Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) | Vertebrates | Diffusion & Extracellular Modulation | PCT, Smoothened, Megf8, Mgrn1 | Neural tube patterning [5] |

| Wnt | Vertebrates, Drosophila | Diffusion & Restricted Spread | Frizzled receptors, extracellular inhibitors | Limb patterning, cell fate specification [6] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Investigating morphogen gradients requires sophisticated genetic, cell biological, and biophysical techniques to visualize endogenous proteins and perturb specific mechanisms.

Visualizing Endogenous Morphogen Gradients

A significant challenge has been the difficulty of visualizing endogenous morphogens at physiological levels. A breakthrough methodology involves generating functional, fluorescent protein-tagged alleles.

- Protocol: Generation of Endogenous Fluorescent-Tagged Morphogen Alleles [7]

- Allele Design: Insert a bright fluorescent protein (e.g., mGreenLantern or mScarlet) into the native morphogen gene locus, typically at the C-terminus of the mature peptide, to minimize disruption to protein folding and processing.

- Transgenesis: Use site-specific recombination (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 or phiC31 integrase) to create a knock-in allele.

- Functional Validation:

- Genetic Rescue: Homozygous flies must be assessed for viability and adult wing morphology to confirm the tagged protein is functional.

- Signaling Activity: Immunostaining for phosphorylated Mad (pMad) in wing discs confirms the allele can activate the downstream signaling pathway correctly.

- Imaging: Use confocal microscopy to visualize both the extracellular gradient (via non-permeabilized immunostaining with α-GFP antibodies) and the total cellular pool (via direct fluorescence) in larval wing imaginal discs.

Perturbing Endocytic Trafficking

To dissect the role of intracellular trafficking, specific steps of the endocytic pathway can be blocked.

- Protocol: Blocking Key Endocytic Compartments [7]

- Dynamin-mediated Internalization: Express a dominant-negative form of Dynamin (e.g., Shibire(^{ts})) in clones of cells. This blocks all endocytosis from the plasma membrane.

- Early Endosome Function: Knock down or express dominant-negative Rab5 in clones to disrupt early endosome maturation and fusion.

- MVB Formation: Knock down key components of the ESCRT machinery (e.g., Vps28, Vps25, or Hrs) in clones to prevent the formation of intraluminal vesicles and block signal termination at this step.

- Lysosomal Degradation: Knock down or express dominant-negative Rab7 to disrupt transport from late endosomes to lysosomes.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence of a typical genetic experiment to test the role of a specific gene in morphogen trafficking:

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Dpp Trafficking Experiments in Wing Discs [7]

| Experimental Condition | Effect on Extracellular Dpp Gradient | Effect on pMad Signaling Gradient | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Wild-type) | Normal graded distribution | Normal graded distribution | Baseline gradient formation and interpretation |

| Block Dynamin (Shibire^ts^) | Gradient expands | Signaling is impaired | Internalization is required for signaling and shapes extracellular gradient |

| Block Rab5 (Early Endosome) | No major change | Signaling range expands | Early endosomes are dispensable for spreading but required for signal attenuation |

| Block MVB (ESCRT) | No major change | Signaling range expands | Signal termination occurs at the MVB; critical for interpreting extracellular gradient |

| Block Rab7 (Lysosome) | Not reported | Minor or no change | Lysosomal degradation is not the primary mode of signal termination |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is a classic example of a morphogen pathway whose interpretation is critical for development. Its core components and regulatory feedback are outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for experimental research in morphogen gradient biology.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Morphogen Gradient Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Fluorescent-tagged Alleles (e.g., mGL-dpp) | Enables visualization of endogenous morphogen distribution at physiological expression levels. | Directly quantifying extracellular and intracellular Dpp gradients in Drosophila wing discs [7]. |

| Dominant-Negative Dynamin (Shibire(^{ts})) | Blocks clathrin-mediated endocytosis in a temperature-sensitive manner. | Testing the necessity of internalization for morphogen signaling and gradient formation [7]. |

| Rab5, Rab7, ESCRT Mutants/RNAi | Allows specific disruption of distinct endosomal compartments. | Dissecting the role of early endosomes, MVBs, and lysosomes in signal activation and termination [7]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (e.g., α-pMad) | Marks cells with active morphogen signaling. | Visualizing the transcriptional output gradient of Dpp/BMP signaling [7]. |

| Receptor Mutants (e.g., tkv, pnt) | Removes key sinks and signaling components. | Studying how receptor binding and internalization shape the morphogen gradient [7]. |

| HSPG Mutants (e.g., dally, dly) | Disrupts extracellular matrix interactions with morphogens. | Investigating the role of the extracellular environment in stabilizing and transporting morphogens [7]. |

Morphogens are signaling molecules that are secreted from a localized source and form long-range concentration gradients to regulate growth and patterning of tissues and organs in a concentration-dependent manner [8] [9]. A fundamental challenge in developmental biology has been to understand how these gradients are formed, maintained, and interpreted by target cells. While extracellular diffusion and binding interactions were initially considered the primary shaping forces, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that intracellular trafficking plays an equally critical role in both shaping morphogen distribution and determining cellular response [8] [10] [7]. This endocytic debate centers on how the complex journey of morphogens and their receptors through the endosomal network—from internalization to recycling or degradation—controls the precision of developmental patterning.

The traditional view of morphogen gradient formation emphasized passive diffusion and limited extracellular stability. However, research spanning decades has revealed that morphogen activity is intimately linked with receptor-mediated endocytosis and subsequent intracellular sorting [8] [9]. The Dpp/BMP pathway in Drosophila, particularly in the wing imaginal disc, has served as a valuable model for these studies, demonstrating how trafficking influences both gradient geometry and signaling output [8] [7]. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of how distinct endocytic compartments contribute to morphogen gradient formation and interpretation, with particular emphasis on quantitative approaches that bridge molecular mechanisms to tissue-level patterning.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Trafficking Shapes Gradient Formation

Endosomal Network Architecture and Cargo Dynamics

The endocytic pathway comprises a series of interconnected compartments with distinct biochemical properties and functions. Following internalization, cargo enters early endosomes marked by the small GTPase Rab5, where the initial sorting decisions occur [8] [10]. Cargo can then be recycled to the plasma membrane via recycling endosomes or targeted for degradation through maturation into late endosomes (characterized by Rab7) and subsequent fusion with lysosomes [8]. A specialized compartment known as the multivesicular body (MVB) facilitates the sorting of activated receptors into intraluminal vesicles for degradation, representing a key point of signal regulation [7].

Quantitative studies of endosomal network dynamics reveal that cargo distribution follows characteristic patterns influenced by kinetic parameters such as cargo influx, endosome fusion-fission rates, and endosome lifetime. One theoretical approach modeling these dynamics estimated the average time between endosome fusion events at approximately 3 minutes, with an endosome lifetime of roughly 11 minutes [8]. These parameters create a highly dynamic system where cargo amounts in single endosomes can vary over wide ranges, enabling precise regulation of signaling duration and intensity.

Models of Morphogen Gradient Formation

Several models have been proposed to explain how endocytic trafficking contributes to morphogen gradient formation:

- Transcytosis Model: Morphogens are internalized and transported through cells via repeated cycles of endocytosis and exocytosis, potentially extending their range [7].

- Glypican-Mediated Transport: Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (e.g., Dally) internalize and recycle morphogens independently of signaling receptors, contributing to extracellular gradient formation [7].

- Receptor-Mediated Sink Model: Signaling receptors (e.g., Tkv for Dpp) internalize morphogens, creating a sink that limits spread, with extracellular factors antagonizing this process to establish long-range distribution [7].

Recent research utilizing functional fluorescent protein-tagged Dpp alleles has provided new insights, demonstrating that while Dynamin-mediated internalization is required for Dpp signaling activation, Rab5-mediated early endosomal trafficking is surprisingly dispensable for Dpp spreading but essential for signal termination [7].

Table 1: Key Trafficking Components and Their Roles in Morphogen Gradient Formation

| Trafficking Component | Role in Gradient Formation | Effect When Disrupted |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamin | Mediates initial internalization of ligand-receptor complexes | Expands extracellular morphogen distribution but impairs signaling [7] |

| Rab5 | Regulates early endosome formation and cargo sorting | Expands signaling range due to impaired receptor downregulation [7] |

| Rab7 | Controls late endosome maturation and lysosomal degradation | Limited effect on Dpp signaling termination [7] |

| ESCRT Complex | Mediates MVB formation and receptor sorting into ILVs | Expands intracellular signaling range without altering extracellular gradient [7] |

| Recycling Endosomes | Return receptors to plasma membrane | Modulates cellular sensitivity and response duration [10] |

Interpretation of Gradients: How Cells Decode Positional Information

Signal Activation and Termination Compartments

The interpretation of morphogen gradients depends not only on ligand concentration but also on the subcellular location of signal activation and termination. Research has revealed that signaling is not restricted to the plasma membrane; instead, various endosomal compartments serve as distinct signaling platforms that influence the strength and duration of signaling outputs [10].

For Dpp/BMP signaling, recent evidence indicates that signal termination occurs primarily at the multivesicular body (MVB) through ESCRT-dependent sorting of activated receptors into intraluminal vesicles, rather than through Rab7-mediated lysosomal degradation [7]. When MVB formation is blocked, the Dpp signaling gradient expands without altering the extracellular Dpp distribution, demonstrating that this compartment is critical for proper interpretation of the morphogen gradient [7]. This finding highlights how the duration of intracellular signaling, controlled by trafficking kinetics, contributes to positional information.

Temporal Dynamics in Signal Interpretation

Cells can interpret both the concentration and duration of signaling activity to determine fate decisions. A striking example comes from Notch signaling, where different ligands (Dll1 and Dll4) produce distinct temporal patterns of NICD (Notch intracellular domain) release despite signaling through the same receptor [10]. These dynamics arise from differential endocytic clustering and transcytosis, leading to either pulsed or sustained NICD activity that is decoded into distinct transcriptional programs and cell fates [10].

Similarly, for the EGF receptor, spatially distinct populations of phosphatases control signaling kinetics, with plasma membrane-localizing PTPRJ/G and ER-localizing PTPN2 exhibiting different dephosphorylation rates [10]. The rate of perinuclear accumulation of receptor-bearing endosomes thus influences signaling lifetime, connecting trafficking speed to signal interpretation.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Endocytic Trafficking in Signal Interpretation

| Parameter | Experimental Measurement | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling Duration | Temporal analysis of pMad dynamics | Determines extent of target gene expression and patterning [7] |

| Receptor Phosphorylation Lifetime | FRET-based biosensors and phospho-specific antibodies | Influences signal output strength; regulated by compartment-specific phosphatases [10] |

| Perinuclear Accumulation Rate | Live imaging of fluorescently tagged receptors | Controls exposure to perinuclear phosphatases that deactivate receptors [10] |

| Endosomal Residence Time | Single endosome tracking and photoconversion | Determines opportunity for signal complex assembly and activation [8] |

| Ligand-Receptor Interaction Time | Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) | Affects signaling output magnitude and duration [10] |

Experimental Approaches and Key Findings

Visualization and Perturbation of Endogenous Morphogens

A significant advance in the field came from the generation of functional fluorescent protein-tagged dpp alleles (mGL-dpp and mSC-dpp) that enable simultaneous visualization of extracellular and intracellular Dpp distribution at physiological expression levels [7]. These tools revealed that Dpp predominantly exists intracellularly, with only a small fraction detectable extracellularly, highlighting the importance of intracellular trafficking for Dpp distribution and signaling.

Using these endogenous tags with systematic perturbation of trafficking components, researchers have delineated the specific roles of different endocytic compartments. The experimental workflow typically involves:

- Genetic perturbation of specific trafficking components (e.g., Rab5, Rab7, ESCRT subunits) using RNAi or dominant-negative mutants

- Quantitative imaging of extracellular vs. intracellular morphogen distribution

- Assessment of signaling activity via phospho-Mad (pMad) staining or other pathway reporters

- Correlation of trafficking defects with phenotypic outcomes in wing disc patterning and adult wing morphology [7]

This approach demonstrated that while Dynamin-mediated internalization shapes the extracellular Dpp gradient, MVB-dependent termination interprets this gradient by controlling signaling duration [7].

Quantitative Imaging and Computational Modeling

Advanced imaging techniques combined with computational modeling have been instrumental in bridging molecular-scale trafficking events with tissue-level gradient formation. Quantitative approaches include:

- Single-particle tracking of quantum dot-labeled ligands to follow trafficking itineraries

- Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy to measure binding interactions and diffusion coefficients

- Automated image analysis of large endosome populations to derive cargo distribution functions [8]

- Compartmental kinetic modeling to relate trafficking parameters to gradient morphology [8] [11]

These methods have revealed that the endosomal network operates through basic processes—cargo influx, homotypic endosome fusion, endosome fission, and endosome maturation—whose kinetics determine large-scale gradient properties [8]. For instance, analysis of cargo distributions in cells with fluorescently labeled Rab5 enabled estimation that the average time between endosome fusion events is approximately 3 minutes, with an endosome lifetime of about 11 minutes [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Trafficking in Morphogen Gradients

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Functional fluorescent-tagged morphogen alleles (e.g., mGL-dpp, mSC-dpp) | Visualization of endogenous morphogen distribution at physiological levels | Revealed predominant intracellular localization of Dpp and differential effects of trafficking perturbations [7] |

| Dominant-negative Rab mutants (e.g., Rab5DN, Rab7DN) | Specific perturbation of distinct trafficking stages | Established that Rab5-mediated early endocytosis is dispensable for Dpp spreading but required for signal attenuation [7] |

| ESCRT component RNAi | Disruption of MVB formation and ILV sorting | Demonstrated that MVB formation is critical for signal termination and proper gradient interpretation [7] |

| Quantum Dot-FRET tracking | Quantitative analysis of polyplex stability and intracellular unpacking kinetics | Enabled correlation of trafficking kinetics with functional outcomes in gene delivery systems [11] |

| Phospho-specific antibodies (e.g., pMad) | Readout of pathway activation | Revealed expanded signaling range when MVB formation is blocked, despite normal extracellular gradient [7] |

| Cargo distribution analysis | Quantitative imaging of endosomal network dynamics | Enabled estimation of endosomal kinetic parameters (fusion rates, lifetimes) [8] |

The integration of quantitative experimental approaches with theoretical modeling has revolutionized our understanding of how intracellular trafficking shapes and interprets morphogen gradients. The emerging consensus indicates that gradient formation relies on Dynamin-dependent internalization, while gradient interpretation depends on the duration of intracellular signaling controlled by endocytic trafficking through specific compartments, particularly the MVB [7]. This framework reconciles previously conflicting models by assigning distinct roles to different trafficking steps.

Future research directions will likely focus on understanding how trafficking kinetics are modulated at the single-cell level to achieve robust patterning at the tissue scale, and how mechanical forces and cell shape influence trafficking decisions. The development of new imaging technologies capable of tracking multiple endosomal populations simultaneously in developing tissues will further accelerate knowledge gain in this field [10]. As our understanding of these processes deepens, so too will our ability to manipulate patterning systems for therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine and disease treatment.

Morphogen gradients are graded distributions of signaling molecules that specify distinct cellular fates in a concentration-dependent manner, providing a fundamental framework for understanding pattern formation in embryonic development. The concept, formalized by Lewis Wolpert in the positional information model, proposes that cells interpret their spatial position based on the concentration of a signaling molecule, then translate this information into specific developmental behaviors [1]. The first molecular demonstration emerged from studies of the Bicoid transcription factor in the Drosophila syncytium, where it forms an anterior-posterior gradient regulating downstream gap gene expression [1]. Since then, numerous secreted signaling proteins including Dpp, Wingless, Hedgehog, Activin, and Nodal have been identified as morphogens across diverse organisms [1].

Visualizing and quantifying these endogenous gradients presents significant technical challenges. Morphogens operate at microscopic scales, often spanning just a few cell diameters, and their dynamics can unfold within minutes. Furthermore, the interplay between gradient formation and interpretation creates complex feedback loops that necessitate system-level approaches combining experimental and theoretical strategies [1]. This technical guide explores innovative tools and methodologies for tracking endogenous morphogen distribution, providing researchers with practical frameworks for investigating these fundamental patterning mechanisms.

Quantitative Analysis of Morphogen Gradients

Characterizing Gradient Parameters

Quantitative analysis begins with precise measurement of gradient properties. Research indicates that morphogen gradients often exhibit exponential decay profiles, characterized by a single scale parameter known as the characteristic length (λ) [1]. This characteristic length represents the distance over which the morphogen concentration decreases by a factor of e and provides crucial information about gradient shape and spread. For example, studies have revealed that the Bicoid gradient in Drosophila has a characteristic length of approximately 100 μm, substantially larger than Dpp (20 μm) and Wingless (6 μm) gradients in the fly wing [1].

The exponential profile emerges from simple dynamics involving diffusion and linear degradation, where the characteristic length depends on the ratio of the diffusion coefficient (D) to the degradation rate (β) according to the relationship: λ = √(D/β) [1]. This mathematical framework enables researchers to infer dynamic parameters from static images of steady-state gradients, though precise quantification requires careful measurement techniques and appropriate controls.

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Characteristic Lengths of Model Morphogens

| Morphogen | System | Characteristic Length | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bicoid | Drosophila embryo | ~100 μm | Houchmandzadeh et al., 2002 [1] |

| Dpp | Drosophila wing disc | ~20 μm | Kicheva et al., 2007 [1] |

| Wingless | Drosophila wing disc | ~6 μm | Kicheva et al., 2007 [1] |

| BMP | Drosophila embryo | ~5 cells (sharp gradient) | Eldar et al., 2002 [1] |

Experimental Measurement Techniques

Several specialized approaches have been developed for visualizing and quantifying endogenous morphogen distributions:

Fluorescent Protein Fusions: The creation of functional fluorescent protein-morphogen fusions (e.g., GFP fusion proteins) enables direct visualization of gradient formation in living tissues [1]. This approach has been successfully applied to Bicoid, Dpp, and Wingless, revealing their exponential distribution patterns and enabling quantitative analysis of gradient dynamics.

Antibody Staining: Traditional antibody staining provides a static image of morphogen distribution in fixed tissues [1]. While lacking temporal resolution, this method offers high specificity and sensitivity for initial characterization of gradient morphology.

Activity Monitoring: Instead of tracking morphogen distribution directly, some approaches monitor downstream intracellular responses. For example, the BMP activity gradient in Drosophila embryos has been quantified by measuring phosphorylated Mad (pMad) levels, revealing a sharp profile that forms within approximately 30 minutes [1].

Computational Modeling: Mathematical modeling serves as an essential tool for interpreting experimental data and testing hypotheses about gradient dynamics. Models can predict how specific parameters affect gradient formation and provide insights that guide experimental design [1].

Experimental Protocols for Gradient Visualization

Live Imaging of Fluorescent Morphogen Fusions

This protocol details the procedure for tracking morphogen dynamics in living Drosophila tissues using endogenously tagged fluorescent fusion proteins.

Materials Required:

- Fly strains with endogenously tagged morphogen (e.g., Dpp-GFP)

- Confocal or light-sheet microscope with temperature control chamber

- Immersion oil appropriate for the objective lens

- Microscope slides and coverslips designed for live imaging

- Image analysis software (e.g., FIJI/ImageJ, Imaris)

Procedure:

- Cross appropriate fly genotypes to generate embryos or larvae expressing the fluorescently tagged morphogen.

- Prepare samples for imaging by mounting tissues in physiological buffer under a coverslip sealed with valap or specialized imaging chamber.

- Maintain samples at appropriate temperature (typically 25°C) throughout imaging procedure.

- Acquire time-lapse images using confocal or light-sheet microscopy with minimal laser power to prevent phototoxicity.

- Capture z-stacks at regular intervals (e.g., every 2-5 minutes) to monitor gradient dynamics.

- Process images using deconvolution algorithms to improve signal-to-noise ratio if necessary.

- Quantify fluorescence intensity along the relevant axis using line scan analysis in ImageJ.

- Fit exponential decay curves to intensity profiles to determine characteristic length.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Photobleaching can be minimized by using reduced laser power and imaging chambers with oxygen scavengers.

- Movement artifacts may require physical immobilization of samples or computational image registration.

- Background fluorescence should be quantified in control regions and subtracted from measurements.

Fixed Tissue Analysis of Endogenous Morphogens

This protocol describes the quantification of morphogen gradients using antibody staining in fixed samples, enabling higher resolution and multiplexing with additional markers.

Materials Required:

- Primary antibodies against target morphogen

- Fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies

- Fixation buffer (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS)

- Permeabilization and blocking buffers

- Mounting medium with DAPI for nuclear counterstaining

- High-resolution confocal or super-resolution microscope

Procedure:

- Dissect tissues in cold PBS and transfer to fixation buffer for 20-45 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash fixed tissues 3×5 minutes in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBT).

- Block non-specific binding sites with 5% normal serum in PBT for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Incubate with primary antibody diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C.

- Wash 3×15 minutes in PBT.

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Wash 3×15 minutes in PBT, with DAPI included in the second wash if desired.

- Mount samples in anti-fade mounting medium and seal with nail polish.

- Image using high-resolution microscopy, ensuring non-saturating acquisition settings.

- Quantify morphogen distribution using intensity profiling and compare across multiple samples.

Validation Controls:

- Include samples without primary antibody to assess background signal.

- Validate antibody specificity using genetic mutants when available.

- Use multiple antibodies recognizing different epitopes to confirm distribution patterns.

Computational Modeling and Data Analysis

Mathematical Framework for Gradient Interpretation

Computational models provide powerful tools for interpreting gradient data and generating testable predictions. The simplest model describing morphogen gradient formation incorporates diffusion from a localized source combined with uniform degradation. This framework generates an exponential steady-state distribution described by the equation:

C(x) = C₀e^(-x/λ)

where C(x) is the concentration at position x, C₀ is the concentration at the source, and λ is the characteristic length (λ = √(D/β)) [1]. Although real biological systems often incorporate additional complexity including reversible binding, facilitated transport, and feedback regulation, this basic model serves as a valuable starting point for quantitative analysis.

Table 2: Key Parameters in Morphogen Gradient Modeling

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Experimental Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion coefficient | D | μm²/s | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) |

| Degradation rate | β | s⁻¹ | Cycloheximide chase experiments |

| Production rate | J | molecules/s | Quantification of source activity |

| Characteristic length | λ | μm | Fluorescence intensity profiling |

| Interpretation threshold | Cₜₕᵣₑₛₕ | molecules/μm³ | Gene expression boundary analysis |

Tools for Quantitative Data Analysis

Several specialized software platforms facilitate quantitative analysis of morphogen gradients:

Displayr: A cloud-based survey analysis platform that specializes in quantitative data visualization and offers automated reporting features, though its application to biological imaging data may require adaptation [12].

Statistical Analysis Software: Programs like SPSS, Excel, SAS, or R provide robust environments for statistical analysis of quantitative data, including regression analysis to determine relationships between variables [13].

Custom Analysis Scripts: Many research groups develop custom analysis pipelines in Python, MATLAB, or R to address specific quantification challenges in gradient analysis, such as accounting for tissue curvature or normalizing between samples.

Computational-Experimental Workflow for Gradient Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful visualization of endogenous morphogen gradients requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials for experimental research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Morphogen Gradient Visualization

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent protein fusions (GFP, RFP) | Tagging morphogens for live imaging | Dpp-GFP, Wingless-GFP | Endogenous tagging preferred over overexpression |

| Specific antibodies | Detecting endogenous morphogens in fixed tissue | Anti-Bicoid, Anti-Dpp | Validate specificity with genetic controls |

| CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing | Endogenous tagging and functional analysis | Insertion of protein tags, creating mutants | Off-target effects must be controlled |

| Advanced microscopy systems (confocal, light-sheet) | High-resolution imaging of gradient dynamics | Live imaging of embryo development | Phototoxicity concerns with prolonged imaging |

| Image analysis software (FIJI, Imaris) | Quantifying fluorescence intensity and distribution | Intensity profiling, 3D reconstruction | Background subtraction critical for accuracy |

| Mathematical modeling software (MATLAB, Python) | Simulating gradient dynamics and making predictions | Testing transport models, estimating parameters | Model complexity should match biological knowledge |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Design

Morphogen gradients function within specific signaling pathways that regulate developmental patterning. Understanding these pathways is essential for designing appropriate visualization experiments.

Morphogen Signaling Pathway with Feedback

The field of morphogen gradient visualization continues to evolve with emerging technologies offering new insights. Advanced imaging techniques including super-resolution microscopy and single-molecule tracking provide increasingly precise measurements of gradient parameters. Meanwhile, developments in genome editing enable more sophisticated genetic manipulations for testing specific hypotheses about gradient function.

The integration of quantitative experimental data with computational modeling remains essential for advancing our understanding of morphogen gradients. This combined approach has already revealed fundamental principles, such as the relationship between gradient dynamics and interpretation [1]. Future research will likely focus on understanding how multiple gradients interact to create complex patterns and how gradient interpretation is modulated by cellular context.

Visualizing endogenous morphogen distribution presents technical challenges, but the methodologies outlined in this guide provide a robust foundation for investigating these fundamental developmental mechanisms. By applying careful quantitative approaches and leveraging innovative tools, researchers can continue to unravel the complexities of pattern formation in developing systems.

Resolving Theoretical Controversies with Modern Experimental Evidence

The concept of morphogen gradients as carriers of positional information represents one of the most influential frameworks in developmental biology. First formally proposed by Lewis Wolpert in his 1969 positional information model [1] and later molecularly demonstrated with the Bicoid gradient in Drosophila [1], this paradigm has undergone significant evolution as experimental techniques have advanced. For decades, the central theoretical controversy in the field has revolved around a fundamental question: Can a single morphogen gradient achieve the remarkable precision observed in embryonic patterning, or do developing tissues require more complex mechanisms such as opposing gradients or supplementary timing mechanisms? This question strikes at the very heart of how we understand the encoding of spatial and temporal information in biological systems.

Recent experimental advances have brought this theoretical controversy into sharp focus. While early models suggested that single gradients could sufficiently pattern tissues, subsequent research revealed apparent precision limitations that seemed to necessitate more complex solutions. The development of sophisticated visualization techniques, quantitative measurements, and computational approaches has now provided unprecedented insight into gradient dynamics. This technical guide examines how modern experimental evidence is resolving long-standing theoretical debates, with particular emphasis on studies conducted in the mouse neural tube—a model system that has proven instrumental for understanding gradient precision and dynamics. We will explore how cutting-edge methodologies are transforming our understanding of morphogen function, from fundamental gradient formation to sophisticated interpretation mechanisms that enable precise tissue patterning in both space and time.

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Controversies

The Positional Information Framework and Its Limitations

The positional information model, as formalized by Wolpert, proposed that cells acquire spatial identity through their position relative to chemical concentration gradients [1]. This framework elegantly explained how organized patterns could emerge across developing tissues, with cells translating gradient information into specific fates through concentration-dependent differentiation. The first molecular validation came with the discovery of the Bicoid gradient in Drosophila, which patterns the anterior-posterior axis through direct concentration-dependent regulation of downstream genes [1].

However, as research expanded to other systems, theoretical challenges emerged. A fundamental limitation concerned timing: while gradients could efficiently convey spatial information, it remained unclear how they could simultaneously orchestrate the precise timing of differentiation events [4]. Additionally, quantitative analyses suggested that single gradients might lack the precision required to establish sharp boundaries in developing tissues, leading to proposals that opposing gradient systems or supplementary timing mechanisms must operate [4] [14].

The Precision Problem in Gradient Interpretation

Theoretical work highlighted a fundamental precision limitation in gradient-based patterning. For an exponential gradient described by C(x) = C₀exp(-x/λ), boundary positions are established where the concentration reaches a specific threshold: xθ = λln(C₀/Cθ) [14]. This relationship makes boundary positions sensitive to variations in both gradient amplitude (C₀) and decay length (λ). Molecular noise in morphogen production, transport, and degradation inevitably creates embryo-to-embryo variations in these parameters, theoretically translating into significant positional errors in boundary establishment [14].

This precision problem led to the hypothesis that single gradients were insufficient for precise patterning. Research in the mouse neural tube appeared to support this view, with reported positional errors of gradients increasing from 1-2 cell diameters in early stages to more than 30 cell diameters later in development [14]. These observations formed the basis for proposing that combined readout of opposing Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) gradients was necessary to achieve the observed precision of central progenitor domain boundaries [14].

Modern Experimental Approaches to Gradient Analysis

Advanced Visualization and Quantification Techniques

Contemporary morphogen gradient research employs sophisticated visualization and quantification methods that have dramatically improved measurement precision. Current protocols, as detailed in works such as "Morphogen Gradients: Methods and Protocols" [15], include:

- Fluorescent protein-morphogen fusions for live imaging of gradient dynamics

- Antibody staining techniques for high-resolution spatial mapping of endogenous morphogen distributions

- Transcriptional reporters (e.g., GBS-GFP for SHH signaling) to monitor gradient interpretation in real time

- Phosphorylation-specific antibodies (e.g., for pSMAD in BMP signaling) to visualize activity gradients of signal transduction cascades

These techniques have enabled researchers to move beyond static snapshots of gradient distributions to dynamic measurements of gradient formation and interpretation. For instance, imaging of functional fluorescent protein-morphogen fusions has revealed that gradients such as Bicoid in Drosophila and Dpp and Wingless in the fly wing typically exhibit exponential decay profiles, characterized by a single scaling length that defines their spatial extent [1].

Computational and Mathematical Modeling Approaches

The integration of theoretical and experimental approaches has been essential for advancing our understanding of gradient dynamics [1]. Mathematical modeling enables researchers to:

- Quantify gradient parameters by fitting mathematical functions to experimental data

- Extract kinetic parameters (diffusion and degradation rates) from gradient dynamics

- Test hypothetical mechanisms through numerical simulations

- Distinguish between alternative models that could explain observed gradient behaviors

For exponential gradients, the characteristic length λ depends on the diffusion coefficient (D) and degradation rate (β) as λ = √(D/β) [1]. This relationship highlights a fundamental insight: different combinations of D and β can produce identical steady-state gradients, necessitating dynamic measurements to distinguish between potential mechanisms. Computational approaches have thus become indispensable for interpreting experimental data and deriving biologically meaningful parameters from gradient observations.

Table 1: Key Experimental Techniques in Modern Morphogen Gradient Research

| Technique Category | Specific Methods | Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphogen Visualization | Antibody staining, GFP fusion proteins, Fluorescent in situ hybridization | Static mapping of morphogen distribution, Live imaging of gradient dynamics | Fixation artifacts, Tag-induced functional alterations, Limited temporal resolution |

| Signaling Activity Readouts | Phosphorylation-specific antibodies, Transcriptional reporters, SMAD phosphorylation assays | Monitoring intracellular signaling activity, Real-time tracking of gradient interpretation | Reporter sensitivity thresholds, Indirect measurement of signaling |

| Computational Approaches | Exponential fitting, Reaction-diffusion modeling, Noise analysis, Error propagation methods | Quantifying gradient parameters, Predicting boundary positions, Estimating patterning precision | Model dependence, Parameter uncertainty, Computational complexity |

Case Study: Re-evaluating Gradient Precision in the Neural Tube

Experimental Redesign and Methodology

A seminal 2022 study published in Nature Communications fundamentally reassessed the precision of morphogen gradients in the mouse neural tube, providing a textbook example of how improved methodologies can resolve theoretical controversies [14]. This research employed multiple independent approaches to overcome limitations of previous gradient measurements:

First, researchers directly compared different error estimation methods using synthetic exponential gradients with known statistical properties matching those reported for neural tube gradients [14]. This controlled approach enabled systematic evaluation of methodological artifacts in precision assessment.

Second, the study implemented a Direct Error Estimation Method (DEEM) that determined boundary positions in individual embryos and calculated the standard deviation of these positions, avoiding approximation errors inherent in previous indirect methods [14].

Third, researchers developed numerical simulations based on measured molecular noise levels in morphogen production, turnover, and diffusion to independently estimate gradient variability and positional error [14].

Critical to these advances was the use of improved statistical methods that acknowledged a fundamental mathematical reality: the arithmetic mean of different exponential functions is not itself exponential [14]. This insight resolved discrepancies between previous analytical approaches and direct measurements.

Resolution of a Theoretical Controversy

The revised experimental approach yielded a striking conclusion: the positional error of morphogen gradients in the neural tube had been significantly overestimated in previous studies [14]. Where earlier work reported errors increasing to more than 30 cell diameters in the neural tube center, the new analysis revealed that a single morphogen gradient could achieve the observed precision of central progenitor domain boundaries (NKX6.1 and PAX3 boundaries) throughout the first day of neural tube development [14].

This finding resolved the long-standing theoretical debate about whether opposing gradients were necessary for precise patterning. The research demonstrated that the combined readout of SHH and BMP gradients, previously proposed as essential for achieving precision, was not required—a single gradient provided sufficient positional information [14]. Furthermore, the study revealed that the size of gene expression domains remains independent of gradient amplitude variability when boundaries are established by threshold-based readout of a single gradient, creating a robust mechanism for producing precise progenitor cell numbers [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Error Estimation Methods in Morphogen Gradient Studies

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations | Impact on Precision Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FitEPM (Fitted Error Propagation Method) | Fit exponential to mean gradient, use analytical derivative in error propagation | Simple implementation, Works well near source | Overestimates error far from source (mean of exponentials isn't exponential) | Led to overestimation of positional errors, supporting multi-gradient models |

| NumEPM (Numerical Differentiation Error Propagation Method) | Numerical differentiation of mean gradient, use in error propagation | Better handles non-exponential mean shapes | Still indirect method, Sensitive to noise in mean gradient | Produced moderate error estimates |

| DEEM (Direct Error Estimation Method) | Direct determination of boundary positions in individual embryos, calculate standard deviation | Direct measurement, Avoids approximation artifacts, Mathematically precise | Requires high-quality data from multiple embryos | Revealed single gradients are sufficiently precise, resolved controversy |

Emerging Concept: Gradients as Temporal Regulators

Experimental Evidence for Dual Position-Time Encoding

Recent research has revealed an additional layer of functionality in morphogen gradients: their capacity to convey temporal information alongside positional cues. A 2025 study proposed that the same morphogen gradients that specify position can also enable cells to measure time during development [4]. This mechanistic insight emerged from quantitative analysis of the Sonic Hedgehog gradient in the mouse neural tube, combined with theoretical modeling of gradient dynamics in growing tissues.

The experimental approach involved precise measurement of SHH gradient dynamics during neural tube development, with particular attention to how gradient properties change as both the morphogen source and the target tissue expand [4]. Researchers tracked the spatial and temporal dynamics of SHH signaling using multiple complementary approaches, including direct morphogen visualization and signaling activity reporters.

The key discovery was that a passively co-expanding morphogen source, as found in the developing neural tube, produces a characteristic "hump-shaped" transient signal at fixed positions within the tissue [4]. As the source expands, morphogen abundance initially increases, but subsequently decreases due to tissue growth, exposing cells to a predictable temporal sequence of morphogen concentrations that can serve as a timing mechanism.

Theoretical Implications and Experimental Validation

This dual functionality of morphogen gradients resolves another theoretical puzzle: how the timing of differentiation is coordinated with positional specification during development. The proposed mechanism is strikingly simple, requiring no additional molecular machinery beyond the existing gradient system [4].

Experimental validation came from demonstrating that opposing gradient systems, such as the SHH and BMP gradients in the neural tube, can synchronize developmental timing across the entire tissue [4]. The research showed quantitatively where in the neural tube cells experience transient signaling and for what duration, providing a direct link between gradient dynamics and differentiation timing.

This conceptual advance has profound implications for understanding developmental programs, suggesting that the same signaling systems that pattern tissues spatially can also orchestrate temporal sequences of differentiation. The integration of positional and temporal information within single gradient systems represents a more parsimonious and robust mechanism than previously imagined.

Schematic of dual positional and temporal information encoding in morphogen gradients, based on experimental evidence from neural tube development [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Critical Reagents for Gradient Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Morphogen Gradient Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphogen Visualization Tools | Anti-SHH antibodies, Anti-BMP antibodies, GFP fusion constructs, Fluorescent protein tags | Direct gradient visualization, Live imaging of gradient dynamics, Quantifying morphogen distribution | Enable direct observation of morphogen spatial distribution and dynamics |

| Signaling Activity Reporters | Phospho-SMAD antibodies, GBS-GFP transcriptional reporter, Phosphorylation-specific antibodies | Monitoring intracellular signaling activity, Assessing gradient interpretation, Measuring pathway activation | Provide readouts of gradient interpretation at cellular level |

| Computational Tools | Exponential fitting algorithms, Reaction-diffusion modeling software, Error analysis frameworks, Statistical comparison packages | Quantifying gradient parameters, Estimating patterning precision, Simulating gradient dynamics | Enable quantitative analysis and theoretical modeling of gradient properties |

| Genetic Tools | Transgenic reporter lines, Conditional knockout systems, Tissue-specific drivers, CRISPR-Cas9 editing systems | Testing necessity and sufficiency, Manipulating gradient components, Analyzing gene function | Allow functional manipulation of gradient formation and interpretation |

Experimental Workflows for Gradient Analysis

The integration of these reagents into standardized experimental workflows has been essential for resolving theoretical controversies. A typical comprehensive gradient analysis involves:

Workflow 1: Precision Assessment

- Gradient Visualization - Use antibody staining or fluorescent reporters to visualize morphogen distribution in multiple embryos [15] [14]

- Quantitative Profiling - Extract intensity profiles across the patterning field using image analysis software [14]

- Boundary Determination - Identify expression boundaries in individual samples using standardized thresholding [14]

- Error Calculation - Apply direct error estimation methods (DEEM) to calculate positional variability [14]

Workflow 2: Temporal Dynamics Analysis

- Time-Series Imaging - Capture gradient dynamics using live imaging of fluorescent reporters [4] [15]

- Source and Tissue Measurement - Quantify changes in source size and tissue dimensions over time [4]

- Signal Transient Analysis - Track concentration changes at fixed positions to identify hump-shaped dynamics [4]

- Synchronization Assessment - Analyze correlation between opposing gradients in timing coordination [4]

Experimental workflow for morphogen gradient analysis, integrating multiple methodological approaches to resolve theoretical questions.

Modern experimental evidence has fundamentally transformed our understanding of morphogen gradients, resolving long-standing theoretical controversies through improved methodologies and quantitative approaches. The integration of advanced visualization techniques, precise computational methods, and sophisticated genetic tools has revealed that gradient systems are both more precise and more multifunctional than previously appreciated.

The resolution of these controversies has substantial implications for both basic developmental biology and applied biomedical research. The demonstration that single gradients can achieve high patterning precision simplifies our understanding of developmental mechanisms and provides more straightforward frameworks for tissue engineering applications. Meanwhile, the discovery that gradients convey both positional and temporal information reveals previously unrecognized efficiencies in developmental programming.

These insights fundamentally reshape our theoretical framework of morphogen function, suggesting that developmental systems achieve robustness through elegant integration of multiple information types within single signaling systems rather than through redundant or overlapping mechanisms. As research continues to advance, further integration of experimental and theoretical approaches will undoubtedly continue to resolve additional controversies and reveal new layers of sophistication in these fundamental biological patterning systems.

Advanced Model Systems and Engineering Approaches for Gradient Study

Organoid technology represents a transformative advancement in biomedical research, enabling the in vitro modeling of human tissue complexity with unprecedented fidelity. These three-dimensional, self-organizing cellular structures recapitulate key aspects of in vivo organ development, architecture, and function, providing a critical bridge between conventional two-dimensional cell cultures and animal models. By preserving the genetic, phenotypic, and functional characteristics of original tissues, organoids have emerged as powerful platforms for drug evaluation, disease modeling, and personalized medicine. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles underlying organoid systems, with particular emphasis on their relationship to morphogen gradient formation and interpretation—the very signaling mechanisms that orchestrate tissue patterning in vivo. We detail standardized methodologies for organoid generation, culture, and application while highlighting recent technological innovations that enhance physiological relevance and screening throughput. The integration of organoids into drug development pipelines promises to improve predictive accuracy, reduce reliance on animal models, and ultimately accelerate the translation of therapeutic candidates to clinical practice.

Organoids are defined as specialized classes of cellular models that can self-organize into tissue-like structures containing multiple relevant cell types from the tissues they represent [16]. Unlike traditional two-dimensional cell cultures, organoids maintain three-dimensional architecture, cellular heterogeneity, and tissue-specific functions that closely mirror in vivo biology [17]. The foundation of modern organoid technology stems from the landmark 2009 discovery of LGR5+ adult stem cells in the intestine and the development of methods to culture these cells to mimic a near-native physiological environment [18].

The physiological relevance of organoids arises from their ability to recapitulate developmental processes, including the self-organization and cell fate determination governed by morphogen gradients—concentration-dependent signals that instruct cells regarding their position and identity within a tissue [4]. In developing tissues, morphogen gradients form through diffusion from localized sources to distributed sinks, with tissue geometry playing a critical role in gradient establishment and maintenance [19]. Organoid systems successfully mimic these patterning mechanisms, making them invaluable for studying human development, disease pathogenesis, and drug responses.

The drug development landscape is increasingly embracing organoid technology, particularly following regulatory shifts such as the FDA's 2025 roadmap for reducing animal testing requirements [17] [18]. With clinical trial failure rates exceeding 85% for some therapeutic areas, the pharmaceutical industry requires more predictive models that better capture human-specific biology [20]. Organoids address this need by preserving patient-specific genetic backgrounds, tumor heterogeneity, and tissue-level responses to therapeutic interventions, thereby enabling more accurate preclinical assessment of drug efficacy and toxicity.

Theoretical Foundations: Morphogen Gradients in Development and Organoid Systems

Principles of Morphogen Gradient Formation

Morphogen gradients are fundamental to tissue patterning in embryonic development, providing positional information that guides cell fate decisions. Traditional models describe gradient formation through source-diffusion-degradation mechanisms, wherein morphogens diffuse from a localized source and are degraded throughout the tissue [19]. Recent research has revealed that the complex geometry of developing tissues significantly influences gradient dynamics. Computational reconstructions of zebrafish epiboly have demonstrated that the tortuous extracellular space affects morphogen distribution, with pore connectivity directly impacting gradient shape and robustness [19].

The same morphogen gradients that convey positional information can also enable cells to measure developmental time, particularly in growing tissues with expanding morphogen sources [4]. As the source expands, morphogen abundance increases initially then decreases as tissue growth dilutes the signal, creating a hump-shaped temporal profile that cells can interpret as a timing mechanism [4]. This dual functionality of morphogens—encoding both spatial and temporal information—is crucial for recapitulating proper tissue development in organoid systems.

Recapitulating Morphogen Gradients in Organoid Culture

Organoid technology leverages understanding of morphogen signaling to direct self-organization and differentiation in vitro. Key signaling pathways—including Wnt, BMP, Notch, and Hedgehog—are manipulated through precise supplementation of growth factors and small molecule inhibitors to mimic in vivo niche signals [21]. The establishment of these signaling gradients in three-dimensional organoid cultures enables the coordinated processes of stem cell self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation that characterize functional tissues.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Intestinal Organoid Development

| Pathway | Role in Intestinal Homeostasis | Common Modulators | Effect on Cell Fate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Stem cell maintenance | CHIR99021 (activator) | Promotes LGR5+ stem cell expansion [21] |

| Notch | Proliferation vs. differentiation choice | DAPT (inhibitor) | Inhibits secretory differentiation [21] |

| BMP | Differentiation control | Noggin, DMH1 (inhibitors) | Promotes epithelial maturation [21] |

| EGF | Proliferation stimulation | EGF | Enhances growth and viability [21] |