Multicolor Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Advanced 3D Applications

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement or optimize multicolor whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH).

Multicolor Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Advanced 3D Applications

Abstract

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement or optimize multicolor whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH). It covers foundational principles of spatial gene expression analysis, detailed methodological protocols for both chromogenic and fluorescent techniques, advanced troubleshooting strategies for common challenges, and rigorous validation approaches. With a focus on recent technological advances such as Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) and 3D imaging compatibility, this guide synthesizes current best practices for obtaining reliable, publication-quality data in diverse model systems, from zebrafish and Drosophila to non-model organisms.

Understanding Multicolor WISH: Core Principles and Probe Design Strategies

What is Multicolor WISH? Defining Key Concepts and Applications

Multicolor Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) is an advanced molecular technique that enables the simultaneous visualization of multiple distinct RNA transcripts within the three-dimensional context of intact biological specimens. By using nucleic acid probes labeled with different fluorescent or chromogenic tags, researchers can map the precise spatial relationships and co-expression patterns of multiple genes directly in fixed tissues, preserving critical anatomical information often lost in sectioned samples [1] [2]. This powerful method is particularly invaluable for studying complex biological processes in diverse research organisms, especially those where genetic tools are limited [2].

Core Principles and Technical Advantages

Multicolor WISH bridges a critical gap in functional genomics. While sequencing methods like RNA-seq provide comprehensive data on gene abundance, they lack spatial context. Multicolor WISH complements these data by answering where genes are expressed, revealing intricate expression patterns in their native tissue environment [2].

A key application is in the study of regeneration, where resolving gene expression in delicate, newly formed tissues like the planarian blastema is essential. Traditional WISH methods often use harsh proteinase K digestion to permeabilize tissues, which can damage morphology and destroy antigen epitopes, limiting compatibility with subsequent protein analysis [2]. The development of gentler protocols, such as the Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) method, has been a significant advancement. This protocol enhances tissue preservation, particularly for fragile structures like the epidermis and blastema, while still allowing efficient probe penetration for robust signal detection [2].

Essential Reagents and Solutions for Multicolor WISH

Successful execution of a multicolor WISH experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The table below outlines key components and their functions, drawing from proven protocols.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multicolor WISH

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fixative Solution | Preserves tissue architecture and immobilizes RNA transcripts; often formaldehyde-based. | Standard initial step for all specimens [1]. |

| Permeabilization Agents | Enables penetration of probes and antibodies into intact tissues. | Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) mixture used as a gentle alternative to proteinase K [2]. |

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) Probes | Amplifies signal through enzymatic or hairpin-mediated amplification for high sensitivity. | Used in multiplex RNA FISH in mosquito brains for sensitive detection [1]. |

| Formamide | A component of hybridization buffers that helps control stringency. | Standard component of hybridization buffer [1]. |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | Protects RNA integrity during sample preparation. | EGTA (chelating agent) included in NAFA protocol to inhibit nucleases [2]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Multicolor WISH Performance

Evaluating the performance of different WISH protocols provides critical data for researchers selecting a method. The following table compares the NAFA protocol against two established methods based on key performance metrics.

Table 2: Protocol Performance Comparison in Planarian Studies

| Performance Metric | NAC Protocol | NA (Rompolas) Protocol | NAFA Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Preservation | Poor (epidermal damage) [2] | Good [2] | Excellent [2] |

| Probe Permeability & WISH Signal | Strong [2] | Weak (for piwi-1, zpuf-6) [2] | Strong [2] |

| Immunostaining Compatibility | Weak (likely due to protease) [2] | Good [2] | Strong (bright anti-H3P signal) [2] |

| Key Differentiator | Uses mucolytic N-Acetyl Cysteine & proteinase K [2] | Acid-based, no proteinase K [2] | Combined acid (NA/FA) & EGTA, no proteinase K [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: NAFA Fixation for Multicolor FISH and Immunostaining

The following workflow details the NAFA protocol, which has been validated in planarians and adapted for killifish fin regeneration [2].

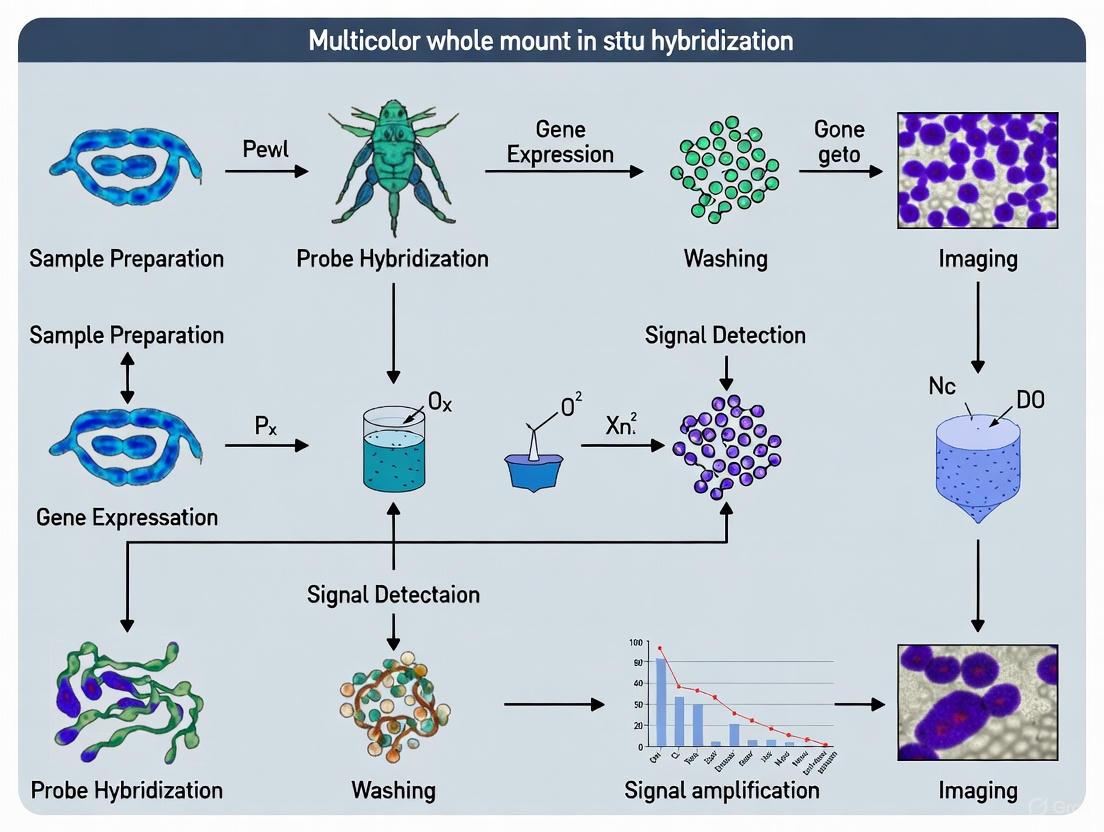

Figure 1: The NAFA protocol workflow for combined FISH and immunostaining.

Sample Preparation and Fixation

- Dissection and Fixation: Dissect tissues (e.g., planarians or killifish tail fins) in a physiological buffer. Immediately transfer samples into fresh fixative solution, typically containing formaldehyde, for a defined period at room temperature to preserve morphology and RNA integrity [1] [2].

- Permeabilization with NAFA Solution: Following fixation, wash samples and incubate in the NAFA permeabilization solution. This critical step, which avoids proteinase K, typically uses a mixture of Nitric Acid and Formic Acid (or other carboxylic acids like acetic or lactic acid), along with the calcium chelator EGTA. This combination gently renders the tissue permeable to probes and antibodies while preserving delicate structures [2].

Hybridization and Signal Detection

- Pre-hybridization and Probe Incubation: Equilibrate tissues in a standard hybridization buffer containing formamide to control stringency. Incubate with gene-specific antisense RNA probes that are labeled with haptens (e.g., Digoxigenin, Fluorescein) or directly with fluorophores. Hybridization is typically performed overnight at an elevated temperature specific to the probe and tissue [1].

- Stringency Washes and Signal Development: After hybridization, perform a series of stringent washes to remove unbound and non-specifically bound probes. For signal detection, choose a method based on your experimental goals:

- Fluorescent HCR: Use fluorescently labeled hairpin probes for Hybridization Chain Reaction, which provides amplified signal and is ideal for multiplexing [1].

- Chromogenic Development: Use an antibody conjugated to an enzyme like Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) against the probe hapten, followed by incubation with a precipitating substrate (e.g., NBT/BCIP) [2].

Immunostaining and Imaging

- Combined Protein Detection: Following the WISH procedure, the same sample can be used for immunostaining. Incubate with a primary antibody against your protein of interest, followed by a fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody. The NAFA protocol's gentle nature results in well-preserved antigen epitopes, yielding a bright and specific immunofluorescence signal [2].

- Mounting and Confocal Microscopy: Clear the tissue and mount it in an anti-fading medium. Image the samples using a confocal microscope to capture the high-resolution, multi-channel three-dimensional data of RNA and protein localization [2].

Applications in Biomedical Research

Multicolor WISH is a cornerstone technique for spatial transcriptomics in a wide range of research fields.

- Regeneration Biology: It is indispensable for studying gene expression dynamics in regenerating tissues, such as planarian bodies and killifish fins, allowing researchers to decipher the molecular signals that control stem cell behavior and patterning in the blastema [2].

- Neuroscience and Development: The protocol has been successfully applied to map 3D spatial gene expression in complex organs like the mosquito brain, helping to unravel the molecular architecture of the nervous system [1].

- Drug Discovery and Development: In pharmaceutical research, Multicolor WISH can be used to visualize the spatial distribution of mRNA targets in whole organisms or tissues in response to drug candidates, providing critical insights into mechanism of action and tissue-specific efficacy.

In the field of molecular biology, the ability to visualize gene expression has been revolutionized by the transition from single-plex to multiplexed analysis. Multiplexing refers to the simultaneous detection of multiple distinct RNA species within the same biological sample. While traditional single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) provides precise quantification of individual transcripts with subcellular resolution, it is fundamentally limited to studying one or a few genes at a time [3]. The development of highly multiplexed spatial transcriptomics technologies has transformed this landscape, enabling researchers to uncover complex gene regulatory networks and cellular heterogeneity that were previously inaccessible. This paradigm shift is crucial for advancing our understanding of biological systems, where cellular processes are orchestrated by coordinated actions of multiple genes rather than by individual transcripts in isolation [4]. By preserving spatial context while dramatically increasing analytical throughput, multiplexed gene visualization provides an indispensable tool for exploring the intricate architecture of tissues and organs during development, in homeostasis, and in disease states.

Key Advantages of Multiplexed Gene Visualization

Unraveling Cellular Heterogeneity and Identity

Multiplexed RNA imaging enables comprehensive cell-type profiling by capturing unique gene expression signatures that define distinct cellular populations within complex tissues. Unlike single-gene detection methods, which provide fragmented information, simultaneous measurement of dozens to thousands of transcripts allows for robust identification and characterization of rare cell types and transitional states that would otherwise be missed [4]. For example, in the developing zebrafish brain, simultaneous visualization of multiple regulatory genes has been essential for mapping distinct neuronal lineages and brain subdivisions [5]. This capability is particularly valuable in stem cell biology and cancer research, where cellular heterogeneity drives functional diversity and therapeutic responses.

Enhanced Diagnostic Specificity and Accuracy

In biomedical applications, multiplexing significantly improves diagnostic precision by reducing false positives and false negatives through multi-marker verification. Cancer diagnosis exemplifies this advantage, as malignant states are associated with aberrant expression of multiple tumor-related genes rather than single biomarkers [4]. When these genes show fluctuating expression even in healthy cells, reliance on a single marker lacks sufficient specificity. Simultaneous detection of multiple cancer-associated transcripts provides a more reliable diagnostic signature, enabling earlier and more accurate disease detection. This multi-parameter approach also facilitates patient stratification and personalized treatment strategies based on comprehensive molecular profiles.

Decoding Gene Regulatory Networks

Multiplexed visualization enables researchers to map spatial relationships between functionally related genes, revealing how their expression patterns are coordinated within tissue architecture. By preserving the spatial context of transcript localization, these techniques can identify potential interactions between signaling pathways and their targets, transcription factor domains, and feedback mechanisms that maintain tissue organization [5]. This spatial dimension is particularly important for understanding morphogenetic processes during embryonic development and organ formation, where the precise positioning of gene expression domains dictates cellular fate decisions and tissue patterning.

Technical Efficiency and Experimental Throughput

From a practical standpoint, multiplexing offers significant resource optimization by maximizing data acquisition from precious biological samples. Rather than performing sequential single-gene detection on serial sections—which introduces alignment challenges and consumes more tissue—multiplexed approaches capture comprehensive gene expression information from the same cells [4]. This is especially valuable for limited clinical specimens or rare experimental models. Additionally, the integration of automated imaging platforms with multiplexed detection enables high-throughput spatial transcriptomics, making large-scale studies of gene expression patterns feasible across multiple conditions, time points, or treatment groups.

Dynamic RNA Monitoring in Living Systems

Recent technological advances have extended multiplexed RNA imaging from fixed specimens to living cells, enabling real-time tracking of RNA dynamics and interactions. While conventional FISH methods provide only static snapshots of gene expression, emerging live-cell multiplexed imaging platforms allow researchers to monitor RNA localization, transport, and turnover in response to cellular stimuli or perturbations [4]. This temporal dimension provides crucial insights into post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms and how RNA behaviors correlate with other cellular components, opening new avenues for studying gene expression dynamics under physiological conditions.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Multiplexed RNA Imaging Technologies

| Technique | Multiplexing Capacity | Spatial Resolution | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| smFISH | 1-10 transcripts | Single-molecule | Precise quantification, subcellular localization | Limited multiplexing, high autofluorescence in plants [3] |

| MERFISH | 10,000+ transcripts | Single-molecule | Error-robust encoding, whole-transcriptome coverage | Multiple hybridization rounds, complex analysis [4] |

| seqFISH/+ | 10,000+ transcripts | Single-molecule | Sparse labeling strategy, super-resolution imaging | Many iterative rounds, photobleaching concerns [4] |

| Live-cell Multiplexed Imaging | 3-10 transcripts | Single-molecule to subcellular | Real-time dynamics, physiological conditions | Lower multiplexing capacity, probe delivery challenges [4] |

| Two-color FISH (AP/POD combination) | 2 transcripts | Cellular | One-step antibody detection, avoids inactivation steps | Limited to few targets, substrate bleed-through [5] |

Experimental Approaches and Workflows

Whole-Mount smFISH for Plant Tissues

The whole-mount smFISH (WM-smFISH) protocol represents a significant advancement for quantitative mRNA analysis in intact plant tissues, which traditionally presented challenges due to high levels of tissue autofluorescence [3]. This method involves several key steps: First, tissues are fixed and embedded in a hydrogel to preserve morphological integrity. Additional clearing steps using methanol and ClearSee treatments are then incorporated to minimize autofluorescence and light scattering. Following clearing, hybridization with gene-specific probes labeled with fluorophores such as Quasar570 or Quasar670 is performed. Finally, cell wall staining using Renaissance 2200 enables precise assignment of transcripts to individual cells [3]. A major advantage of this approach is its compatibility with fluorescent protein reporters, allowing simultaneous detection of mRNA and protein products from the same transgene. The computational workflow for analysis includes cell segmentation based on cell wall signal using Cellpose, quantification of mRNA foci per cell using FISH-quant, and measurement of protein intensity fluorescence with CellProfiler [3].

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) for Multiplexed Detection

HCR provides a powerful signal amplification strategy for multiplexed RNA detection, particularly advantageous for challenging samples like the Anopheles gambiae brain [6]. The protocol begins with tissue dissection and fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde with 0.3% Triton X-100. For probe design, an automated HCR Probe Designer can split target mRNA sequences into short oligos (25 bp) that are filtered based on melting temperature (47°C-85°C), GC content (37-85%), and sequence specificity to eliminate cross-hybridization [6]. Each validated oligo pair is tagged with initiator sequences that trigger self-assembly of fluorophore-labeled hairpin amplifiers upon binding to target RNA. Typically, 15-20 probe pairs per transcript are sufficient for effective visualization. This method can be combined with immunohistochemistry for simultaneous protein detection, though careful fluorophore selection is essential to minimize spectral overlap [6].

Combined Alkaline Phosphatase and Peroxidase Detection Systems

A sophisticated two-color FISH approach combines alkaline phosphatase (AP) and peroxidase (POD) detection systems to overcome limitations of single-enzyme methods [5]. This protocol utilizes AP-Fast Blue and POD-tyramide signal amplification (TSA) with carboxyfluorescein (FAM) for simultaneous fluorescent detection of two different transcripts. Key optimizations include hydrogen peroxide treatment to improve embryo permeabilization and the addition of dextran sulfate to the hybridization mix to enhance signal sensitivity through molecular crowding effects [5]. A significant advantage of this system is the elimination of antibody-enzyme conjugate inactivation steps required in conventional sequential detection protocols, reducing both hands-on time and the potential for false-positive co-localization results due to insufficient inactivation. The AP system's sustained enzymatic activity allows for extended development times, making it particularly suitable for detecting lower abundance transcripts that might be missed with the quickly-quenched POD-TSA system [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplexed FISH Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Design Platforms | AGambiaeHCRdesign, Molecular Instruments probe designer [6] | Customizable probe sets with initiator tags for HCR amplification; ensure specificity through BLAST filtering |

| Fluorophores | Quasar570, Quasar670, Alexa Fluor dyes [3] [6] | Signal detection across multiple channels; select to minimize spectral overlap with autofluorescence |

| Signal Amplification Systems | HCR hairpin amplifiers, TSA systems [6] [5] | Enhance sensitivity for low-abundance targets; HCR offers linear amplification while TSA provides exponential signal enhancement |

| Mounting and Clearing Media | ClearSee, 80% glycerol, ProLong Gold Antifade [3] [7] | Reduce light scattering and autofluorescence; improve imaging depth and signal-to-noise ratio in thick specimens |

| Detection Enzymes | Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), Horseradish Peroxidase (POD) [5] | Enzyme reporters for chromogenic or fluorescent detection; AP allows longer development times than POD |

| Cell Segmentation Tools | Cellpose, FISH-quant, CellProfiler [3] | Computational assignment of transcripts to individual cells; enable single-cell quantitative analysis |

Workflow Integration and Automation

Advanced multiplexed imaging workflows increasingly incorporate automated processing pipelines to handle the computational demands of data analysis. For example, the Tapenade Python package provides user-friendly tools for processing and analyzing multi-layered organoids across scales, including optical artifact correction, 3D nuclei segmentation, and signal normalization across depth and channels [7]. Similarly, integrated workflows for WM-smFISH combine image acquisition with computational analysis to quantify mRNA and protein levels at single-cell resolution, generating spatial heatmaps that visualize expression patterns and ratios between mRNA molecules and protein accumulation [3]. These automated pipelines are essential for extracting biologically meaningful information from the complex datasets generated by highly multiplexed imaging approaches.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Workflow for Combined HCR and Immunohistochemistry

HCR and IHC Combined Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential steps for simultaneous RNA and protein detection in whole-mount tissues, from sample preparation through computational analysis.

Multiplexed smFISH and Computational Analysis Pipeline

smFISH Computational Pipeline: This workflow shows the integration of experimental and computational steps for quantitative analysis of multiplexed FISH data at single-cell resolution.

Multiplexed gene visualization represents a transformative approach in spatial biology, enabling researchers to move beyond single-gene analysis to comprehensive profiling of gene regulatory networks within their native spatial context. The advantages of simultaneous multi-gene detection—including enhanced ability to decipher cellular heterogeneity, improved diagnostic specificity, insights into gene regulatory networks, technical efficiency, and dynamic monitoring capabilities—establish multiplexing as an essential methodology for modern biological research. As these technologies continue to evolve, with improvements in multiplexing capacity, sensitivity, and computational analysis, they promise to further deepen our understanding of complex biological systems and accelerate applications in disease mechanism studies, diagnostics, and therapeutic development [4]. The experimental workflows and reagents detailed herein provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these powerful approaches in diverse model systems and research contexts.

Multicolor whole-mount in situ hybridization (WM-FISH) enables the spatial visualization of gene expression within intact biological specimens, providing three-dimensional transcriptional context that is essential for developmental biology and biomedical research. The core of this technology rests on three interconnected pillars: the design of specific probes, the selection of detectable labels, and the methods for signal amplification and detection. Advancements in these components have significantly enhanced the multiplexing capability, sensitivity, and resolution of the technique, allowing researchers to decode complex gene regulatory networks directly in their native tissue environment. This application note details the critical reagents and methodologies that underpin robust and reproducible multicolor WM-FISH experiments, framed within the context of a broader thesis on protocol optimization.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Their Functions

The following table catalogs the fundamental reagents required for a successful multicolor WM-FISH experiment, along with their specific functions in the protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Multicolor WM-FISH

| Reagent/Category | Function and Importance in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| HCR DNA Oligonucleotide Probes [8] | Split-initiator probes bind adjacent sites on target mRNA; two halves form a complete initiator to trigger amplification, enabling high specificity and low background. |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Hairpin Amplifiers [8] | Upon initiation, these hairpins self-assemble into a fluorescent polymer at the probe site, providing signal amplification in an antibody-free manner. |

| π-FISH Target Probes [9] | Proprietary probes with 2-4 complementary base pairs that form a stable π-shaped bond, increasing hybridization efficiency and signal stability. |

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes [8] | Critical for plant samples; permeabilizes the cell wall to allow probe penetration for whole-mount analysis. |

| White Light Laser (WLL) Microscope [10] | Confocal microscope with tunable excitation wavelengths; essential for distinguishing multiple fluorophores with distinct spectral properties. |

| Formaldehyde / Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [11] | Standard fixative for tissue preservation; maintains structural integrity and RNA localization within the sample. |

| Protease Plus / Proteinase K [11] [8] | Enzyme for tissue permeabilization; can also be used to digest fluorescent proteins when their signal interferes with FISH detection. |

Quantitative Performance of FISH Detection Methods

The choice of detection and amplification strategy directly impacts the sensitivity and quantitative output of a FISH experiment. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of several modern methods, based on comparative studies.

Table 2: Comparison of FISH Detection Method Efficiencies

| Method | Key Mechanism | Proven Applications | Relative Signal Intensity & Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCR RNA-FISH v3 [8] [9] | Enzyme-free, self-assembling DNA hairpin amplification. | Multiplexed RNA detection in plants (Arabidopsis, maize) [8] and animals [1]; compatible with IHC. | High sensitivity with effective background suppression [9]. |

| π-FISH Rainbow [9] | Multi-layer amplification using π-shaped target probes and U-shaped amplifiers. | Detecting DNA, RNA, protein, and neurotransmitters; decoding 21 genes in mouse brain in two rounds. | Highest reported signal intensity and detection efficiency compared to HCR and smFISH [9]. |

| Standard smFISH [9] | Direct hybridization of many short, fluorescently-labeled oligonucleotides. | General purpose RNA detection; requires no amplification. | Lower signal intensity and sensitivity compared to π-FISH and HCR [9]. |

| Multicolor FISH (Non-combinatorial) [10] | Mono-labeled oligonucleotide probes with 8 distinct fluorophores, distinguished by WLL microscopy. | Differentiation of 7-8 microbial taxa simultaneously in activated sludge and mock communities. | High specificity; avoids biases from combinatorial labeling and complex post-processing [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Whole-Mount HCR RNA-FISH

Below is a generalized and optimized protocol for multiplexed whole-mount RNA FISH using the Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR), adapted for robustness across species [8].

Sample Preparation, Fixation, and Permeabilization

- Dissection and Fixation: Dissect fresh tissue in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and immediately transfer to 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in a suitable buffer. Fix overnight at 4°C.

- Dehydration: Wash fixed samples twice with PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20). Process through a graded methanol series (e.g., 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%) incubating for 10 minutes each on ice. Samples can be stored in 100% methanol at -20°C for short-term storage [11].

- Rehydration and Permeabilization: Rehydrate the samples through a reverse methanol series (75%, 50%, 25% methanol in PBST), followed by two washes in PBST. For plant tissues or tough specimens, incubate with a cell wall digesting enzyme solution to ensure adequate probe penetration [8].

Probe Hybridization and HCR Signal Amplification

- Pre-hybridization: Pre-hybridize samples in hybridization buffer for 30 minutes at the desired temperature (e.g., room temperature to 37°C).

- Hybridization: Replace the buffer with fresh hybridization buffer containing the specific HCR split-initiator probes (typically 1-4 nM each). Hybridize overnight in the dark.

- Post-Hybridization Washes: The next day, wash the samples 4-5 times over 1-2 hours with pre-warmed wash buffer to remove unbound probes stringently.

- Amplification: Pre-wash the samples in amplification buffer. Meanwhile, snap-cool the fluorophore-labeled HCR hairpin amplifiers by heating to 95°C for 90 seconds and allowing them to cool at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark. Incubate the samples with the prepared hairpins (typically 60 nM) in amplification buffer for 4-16 hours in the dark.

- Final Washes and Mounting: Wash the samples several times with wash buffer to remove excess hairpins. Counterstain nuclei if desired (e.g., with DAPI), and mount the samples in an anti-fade mounting medium for imaging [8].

Workflow and Technology Comparison Diagrams

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for a whole-mount HCR FISH experiment, covering the key stages from sample preparation to final imaging.

Figure 2: A comparison of advanced FISH technologies, highlighting their core amplification mechanisms and optimal application scenarios to guide method selection.

In situ hybridization (ISH) has evolved from a method for localizing single genes to a sophisticated tool for visualizing multiple nucleic acid targets simultaneously within their native cellular or tissue context. The success of any multicolor whole mount ISH protocol hinges on a foundational element: the effective design and labeling of probes. Non-isotopic haptens, primarily digoxigenin (DIG), fluorescein, and biotin, have become the cornerstones of modern ISH due to their stability, safety, and high signal amplification potential [12]. These haptens are incorporated into nucleic acid probes, which are then detected via specific antibody or affinity interactions conjugated to reporters, enabling the precise spatial resolution of gene expression. Within the framework of a broader thesis on multicolor whole mount ISH, understanding the distinct characteristics of these labeling molecules is not merely a procedural detail but a critical strategic decision that directly impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing capacity of an experiment. This document outlines the fundamental principles and optimized protocols for employing these haptens, providing researchers with the knowledge to design robust and reproducible multiplexed assays.

Hapten and Probe Design Principles

Characteristics of Common Haptens

The choice of hapten is paramount, influencing everything from probe incorporation efficiency to background signal. The table below summarizes the key properties of the three primary haptens used in probe labeling.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Common Non-Isotopic Haptens for ISH

| Hapten | Source/Structure | Detection System | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin (DIG) | Steroid derived from Digitalis purpurea plants [12] | Anti-DIG antibody (conjugated to AP, HRP, or fluorophore) [12] | Very high specificity and low background in animal tissues; excellent for signal amplification [12]. | Detection requires an antibody step, which can be more complex than biotin detection. |

| Biotin | Essential vitamin (Vitamin B7) found in animal tissues [12] | Streptavidin or Avidin (conjugated to AP, HRP, or fluorophore) [12] | Strong affinity binding; well-established protocols. | Endogenous biotin in tissues can cause high background and false positives [12]. |

| Fluorescein | Synthetic organic molecule [13] | Anti-fluorescein antibody (conjugated to AP, HRP, or a different fluorophore) [13] | Directly detectable if conjugated to a fluorophore; widely used for antibody-based detection in multiplexing. | Can be photosensitive; signal may be less amplified than DIG or biotin without secondary detection. |

Probe Design and Labeling Methodologies

Probes for ISH are distinguished by their nucleic acid type, size, and the distribution of the label. DNA probes are commonly generated via nick translation, a method that incorporates hapten-labeled nucleotides (e.g., biotin-11-dUTP, DIG-11-dUTP) into double-stranded DNA [13] [14]. RNA probes (riboprobes), known for their high sensitivity and low background, are synthesized by in vitro transcription using RNA polymerases and hapten-labeled ribonucleotides (e.g., Fluorescein-12-UTP) [13] [15]. For advanced applications requiring high specificity, oligonucleotide probes can be chemically synthesized with a hapten or fluorophore conjugated directly to the 5' or 3' end [10].

A significant technical consideration is that the bulky structure of hapten-labeled nucleotides can cause steric hindrance, potentially reducing the efficiency of incorporation by polymerases. This is particularly noted with biotin, which can lead to suboptimal transcription rates [12]. DIG-labeled nucleotides also exhibit this property, but the high specificity of the detection system often compensates for potentially lower incorporation efficiency. The choice between direct and indirect detection is also crucial. Direct detection, where a fluorophore is attached directly to the probe, is simpler and faster. Indirect detection, using a hapten that is then bound by a labeled antibody or streptavidin, allows for significant signal amplification, making it indispensable for detecting low-abundance targets [13] [12].

Table 2: Probe Synthesis and Labeling Methods

| Method | Probe Type | Principle | Common Haptens Incorporated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nick Translation | DNA | Uses DNase I to create single-strand "nicks" and DNA polymerase I to incorporate labeled nucleotides [13]. | Biotin-dUTP, DIG-dUTP, Dinitrophenol (DNP) [13] |

| In Vitro Transcription | RNA (Riboprobe) | Uses a linearized DNA template and RNA polymerase to synthesize labeled RNA strands [13] [15]. | Fluorescein-UTP, DIG-UTP, Biotin-UTP [13] |

| Chemical Synthesis | Oligonucleotide | Probes are built nucleotide-by-nucleotide with a hapten or fluorophore added during synthesis [10]. | Cy3, Cy5, Alexa Fluor dyes, DIG, Fluorescein [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Multicolor Whole Mount FISH

The following protocol has been optimized for multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization in whole mount echinoderm embryos [16] but can be adapted for other model organisms with appropriate modifications to fixation and permeabilization.

Probe Labeling and Purification

This section details the generation of hapten-labeled riboprobes, which are highly sensitive for detecting mRNA in whole mount specimens.

- Template Preparation: Linearize 5-10 µg of plasmid DNA containing the gene of interest with an appropriate restriction enzyme. Purify the linearized template via phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

- In Vitro Transcription:

- Set up a transcription reaction in a final volume of 20 µL [16]:

- 1 µg linearized DNA template

- 1x transcription buffer

- 10 mM DTT

- 40 U RNase inhibitor

- 2.5 mM each ATP, CTP, GTP

- 1.625 mM UTP

- 0.375 mM hapten-labeled UTP (e.g., DIG-UTP, Fluorescein-UTP) [16]

- 20-40 U of appropriate RNA polymerase (T7, T3, or SP6)

- Note: The 3.75:1 ratio of unlabeled to labeled UTP ensures high incorporation while maintaining probe integrity.

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours.

- Set up a transcription reaction in a final volume of 20 µL [16]:

- DNase Treatment and Purification: Add 2 U of DNase I (RNase-free) and incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C to remove the DNA template. Purify the labeled RNA probe using a spin column-based kit or by precipitation. Resuspend the probe pellet in 50 µL of nuclease-free water or hybridization buffer. Quantify the probe and store at -80°C.

Whole Mount Specimen Preparation and Hybridization

- Fixation and Permeabilization:

- Fixation: Fix embryos or tissues in 4% paraformaldehyde in a MOPS-buffered saline solution (e.g., 0.1M MOPS pH 7, 0.5M NaCl) for several hours at 4°C [16]. For early embryonic stages, it may be necessary to remove fertilization membranes to ensure probe penetration [16].

- Permeabilization: Wash fixed specimens in MOPS buffer with 0.1% Tween-20. For robust permeabilization, treat specimens with proteinase K (e.g., 10 µg/mL for 10-30 minutes) and refix in 4% PFA for 1 hour to maintain morphology.

- Pre-hybridization and Hybridization:

- Pre-hybridize specimens in hybridization buffer (e.g., 70% formamide, 100 mM MOPS pH 7, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, 1 mg/ml BSA) for 1-4 hours at the hybridization temperature (typically 55-65°C) [16].

- Denature the probe by heating to 80°C for 5 minutes and immediately placing on ice.

- Replace the pre-hybridization buffer with fresh hybridization buffer containing the denatured probe (50-100 ng/mL). Hybridize overnight (12-16 hours) at the appropriate temperature.

- Post-Hybridization Washes:

- Remove the probe solution and perform stringent washes to reduce off-target binding:

- Wash 2x in a solution of 70% formamide, 100 mM MOPS pH 7, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20 for 30 minutes each at the hybridization temperature.

- Wash 2x in MOPS buffer with 0.1% Tween-20 for 15 minutes each at room temperature.

- Remove the probe solution and perform stringent washes to reduce off-target binding:

Immunological Detection and Signal Amplification

For hapten-labeled probes, detection requires an antibody-conjugate. For multicolor experiments, probes are typically detected and amplified sequentially.

- Blocking: Incubate specimens in a blocking solution (e.g., 0.5% PerkinElmer Blocking Reagent in MOPS buffer) for 1-2 hours to minimize non-specific antibody binding [16].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with a hapten-specific antibody (e.g., anti-DIG-POD, anti-fluorescein-HRP, or anti-DNP-HRP) diluted in blocking solution for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [16].

- Signal Amplification (Tyramide Signal Amplification - TSA):

- Wash specimens thoroughly to remove unbound antibody.

- Incubate with the appropriate tyramide dye (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 tyramide, Cy3 tyramide) diluted in the provided amplification diluent for 5-30 minutes. TSA provides a 10-200x increase in sensitivity over standard ICC/IHC/ISH methods [13].

- Quench the peroxidase activity from the first TSA reaction by treating the sample with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 30-60 minutes [13].

- Sequential Detection: Repeat steps 1-3 for the next hapten-labeled probe, using a different antibody and a spectrally distinct tyramide dye. This sequential application of TSA reactions allows for the multiplex detection of multiple targets beyond the number of available fluorophores [13].

Visualization of Workflows and Reagent Toolkits

Molecular Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental molecular pathways for detecting each hapten, from probe hybridization to signal generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Multicolor FISH

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multicolor FISH

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nick Translation DNA Labeling System 2.0 (e.g., Enzo) | Provides enzymes and buffer to generate hapten-labeled DNA probes for FISH [12]. | Labeling genomic DNA probes for chromosome enumeration or translocation detection [13]. |

| FISH Tag RNA Kits (e.g., Thermo Fisher) | A complete workflow for generating amine-modified RNA probes, which are then labeled with amine-reactive Alexa Fluor dyes [13]. | Directly creating fluorescent RNA probes for multiplexed gene expression analysis in whole mount embryos [13]. |

| Tyramide SuperBoost Kits (e.g., Thermo Fisher) | Provide extremely sensitive signal amplification via a poly-HRP mediated tyramide reaction, ideal for low-abundance targets [13]. | Detecting rare transcripts or proteins in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections [13]. |

| TSA Palette Kit (e.g., PerkinElmer) | Contains a suite of tyramides with different fluorophores and a blocking reagent for multiplexed signal amplification [16]. | Sequential TSA for detecting 4+ targets in a single specimen using a limited set of primary antibodies [13]. |

| Label It DNP Labeling Kit (e.g., Mirus) | Enzymatically incorporates Dinitrophenol (DNP) hapten into nucleic acid probes, expanding the palette for multiplexing [16]. | Adding a 5th or 6th color channel to a highly multiplexed FISH experiment [13]. |

Mastering the fundamentals of DIG, fluorescein, and biotin labeling is a prerequisite for successful and innovative multicolor whole mount ISH research. The strategic selection of a hapten, informed by an understanding of its inherent advantages and limitations, directly shapes the quality and interpretability of experimental data. By adhering to optimized protocols for probe synthesis, hybridization, and powerful signal amplification techniques like TSA, researchers can push the boundaries of multiplexing. This enables the simultaneous visualization of complex gene regulatory networks within the beautiful and informative context of an intact, three-dimensional embryo, thereby providing profound insights into the spatial orchestration of development and disease.

The selection of detection methodology is a critical determinant of success in multicolor whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH). Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) represent two foundational technological approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations for visualizing spatial gene expression patterns. Within the broader thesis on multicolor whole mount ISH protocol research, this application note provides a structured comparison to guide researchers in selecting the optimal detection system based on experimental objectives, available equipment, and desired throughput. Both techniques enable the localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within a morphological context, yet they differ fundamentally in their detection chemistry, instrumentation requirements, and applications in multiplexing.

CISH utilizes an immunohistochemistry-like peroxidase reaction that produces a permanent, precipitating chromogenic signal visible with a standard bright-field microscope [17]. In contrast, FISH employs fluorophore-labeled probes that require excitation by specific wavelengths of light and detection through a fluorescence microscope equipped with specialized filter sets [10]. The strategic choice between these systems impacts not only the immediate experimental workflow but also the potential for data extraction, long-term sample preservation, and compatibility with downstream analyses.

Technical Comparison: CISH versus FISH

The decision between CISH and FISH involves evaluating multiple technical parameters against experimental requirements. The table below provides a systematic comparison of key characteristics:

Table 1: Technical comparison between CISH and FISH detection methods

| Parameter | Chromogenic ISH (CISH) | Fluorescent ISH (FISH) |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Type | Permanent chromogenic precipitate | Fluorescent emission |

| Microscope Requirements | Standard bright-field microscope | Fluorescence microscope with specific filter sets |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited, typically 2-3 targets | High, with advanced methods detecting 7+ targets simultaneously [10] |

| Signal Permanence | High; slides can be archived for years | Low; fluorophores fade over time |

| Spatial Resolution | Excellent for tissue morphology | Subcellular and single-molecule resolution possible [18] |

| Compatibility with H&E | Direct; allows easy correlation with histology | Indirect; requires serial sections or counterstains |

| Scanning Speed | Fast (approximately 29 sec/mm²) [19] | Slow with z-stacking (approximately 764 sec/mm²) [19] |

| Throughput in Routine Diagnostics | High; superior for high-throughput genetic testing [19] | Lower; more time-consuming for large batches |

| Protocol Duration | Can be lengthy (overnight hybridization) | Variable; IQ-FISH reduces time to 4 hours [19] |

Quantitative Performance Data

Studies directly comparing both methodologies in diagnostic settings demonstrate high concordance. In HER2/neu testing on breast carcinoma tissue microarrays, FISH detected amplification in 24.5% of tumors (46/188) compared to 22.9% (43/188) by CISH, with 94.1% overall concordance (177/188 tumors) [17]. Another study reported 99% concordance (94/95 cases) between CISH and FISH scoring results (Cohen κ coefficient: 0.9664) [19]. The scanning success rate was higher for CISH (97.6% overall, with CISH accounting for only 2 of 13 failed scans) [19].

Experimental Protocols for Multicolor Detection

Two-Color Fluorescent ISH with Differential Detection Systems

This protocol combines alkaline phosphatase (AP) and horseradish peroxidase (POD) reporter systems to enable simultaneous two-color fluorescent detection in a single procedure, eliminating the need for antibody conjugate inactivation [5].

Probe Preparation and Labeling:

- Synthesize antisense RNA probes labeled with haptens (digoxigenin, dinitrophenol, or fluorescein) using in vitro transcription.

- Purify probes and verify integrity by gel electrophoresis.

Sample Preparation and Pre-hybridization:

- Fix whole mount zebrafish embryos (or other model organisms) in 4% paraformaldehyde.

- Permeabilization Enhancement: Treat with 2% hydrogen peroxide to improve tissue permeabilization and subsequent probe accessibility [5].

- Perform proteinase K digestion (concentration and duration optimized for tissue type and age).

- Refix in 4% PFA and pre-hybridize in hybridization buffer at the hybridization temperature.

Hybridization and Washes:

- Signal Enhancement: Add labeled probes to hybridization buffer containing 5% dextran sulfate to increase local probe concentration through molecular crowding [5].

- Hybridize at appropriate temperature for 16-24 hours.

- Perform stringent washes with saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffers at hybridization temperature and room temperature.

Simultaneous Two-Color Detection:

- Block nonspecific binding with blocking reagent.

- Incubate with a mixture of anti-hapten antibodies conjugated to different reporter enzymes:

- Anti-digoxigenin-AP (for target 1)

- Anti-fluorescein-POD (for target 2)

- Wash thoroughly to remove unbound antibodies.

Sequential Substrate Development:

- AP Detection: Develop with Fast Blue substrate for alkaline phosphatase. The AP reaction can proceed for extended periods (hours) due to high signal-to-noise ratio.

- POD Detection: Develop with carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-tyramide using tyramide signal amplification (TSA) for horseradish peroxidase. The TSA reaction is typically limited to 30 minutes as POD is quenched by substrate excess.

Imaging:

- Visualize using a fluorescence microscope with filters for Fast Blue (far-red) and FAM (green) fluorescence.

- Mount and store samples appropriately for fluorescence preservation.

Chromogenic ISH for High-Throughput Analysis

This protocol is optimized for situations requiring permanent staining and high-throughput processing, such as validation of gene amplification in clinical samples [19] [17].

Sample Preparation:

- Use formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections or tissue microarrays (TMAs).

- Deparaffinize slides and perform antigen retrieval using heat-induced epitope retrieval methods.

- Digest with pepsin (8 minutes at room temperature) to expose target sequences [19].

Hybridization:

- Apply digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes specific to the target gene.

- Co-denature specimen and probe at 95°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hybridize overnight (16-24 hours) at 37°C in a humidified chamber.

Post-Hybridization Washes:

- Wash with 0.5× sodium chloride-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer to remove unbound probe.

- Rinse with phosphate-buffered saline with Tween (PBST).

Chromogenic Detection:

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes.

- Apply blocking solution (e.g., CAS-Block) for 10 minutes.

- Incubate with FITC-sheep anti-digoxigenin for 30-60 minutes.

- Wash and incubate with HRP-goat anti-FITC for 30-60 minutes.

- Develop with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) for 20-30 minutes, producing a brown precipitate.

- Counterstain with hematoxylin and eosin, dehydrate, and mount.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents for CISH and FISH applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Labeling Systems | FISH Tag DNA/RNA Kits with Alexa Fluor dyes [13] | Enzymatic incorporation of amine-modified nucleotides for fluorophore conjugation |

| Signal Amplification | SuperBoost Tyramide Signal Amplification Kits [13] | Poly-HRP-mediated deposition of tyramide dyes for low-abundance targets |

| Chromogenic Substrates | DAB, Fast Red, Fast Blue [17] [5] | Enzyme-mediated precipitation for chromogenic detection |

| Fluorescent Substrates | Alexa Fluor tyramides, FITC-tyramide [13] | Enzyme-activated fluorescent precipitation for signal amplification |

| Permeabilization Enhancers | Dextran sulfate [5] | Increases hybridization efficiency through molecular crowding |

| Detection Enzymes | Horseradish peroxidase (POD), Alkaline phosphatase (AP) [5] | Enzymatic reporters for signal generation |

| Blocking Reagents | CAS-Block, normal serum [17] | Reduce nonspecific background staining |

Decision Framework and Workflow Integration

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points for selecting between CISH and FISH based on experimental priorities:

Diagram 1: Decision framework for selecting between CISH and FISH methodologies

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The field of in situ hybridization continues to evolve with significant advancements in multiplexing capacity and analytical methods. Recent developments in multicolor FISH approaches now enable the differentiation of up to eight phylogenetically distinct microbial populations using spectrally unique fluorophores and confocal laser scanning microscopy with white light laser technology [10]. For transcript localization in developmental models, optimized FISH procedures incorporating tyramide signal amplification (TSA) with dextran sulfate and peroxidase activity enhancers (4-iodophenol and vanillin) permit simultaneous visualization of up to three unique transcripts in whole-mount zebrafish embryos [20].

Artificial intelligence is increasingly transforming FISH image analysis. The recently developed U-FISH platform employs deep learning to enhance diverse FISH images for consistent spot detection, achieving an F1 score of approximately 0.924 and enabling AI-assisted FISH diagnostics [18]. This approach demonstrates superior accuracy and generalizability compared to existing methods while maintaining computational efficiency with only 163k parameters. Integration of such AI tools with large language models represents the next frontier in making sophisticated spatial-omics analysis accessible to broader research communities.

These technological advances are expanding the boundaries of what can be achieved with both FISH and CISH methodologies, providing researchers with increasingly powerful tools to resolve complex spatial gene expression patterns with subcellular resolution in their native morphological context.

Effective sample preparation is a critical foundation for successful multicolor whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), particularly in regeneration research where preserving delicate tissue morphology is paramount. This application note details the Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) protocol, a versatile fixation and permeabilization method that superiorly preserves fragile structures like wound epidermis and blastemas while ensuring robust nucleic acid and protein detection. We provide a comprehensive methodological guide, quantitative performance comparisons, and essential resource tables to standardize practices across research and drug development laboratories.

In the context of multicolor WISH for studying complex processes like tissue regeneration, fixation and permeabilization are the most critical determinants of experimental success. Fixation stabilizes cellular components and preserves tissue architecture at a specific moment, preventing degradation and maintaining the spatial context of gene expression. Permeabilization enables macromolecular probes to access their intracellular targets without compromising the structural integrity achieved during fixation.

The technical challenge is particularly acute in regeneration research using models like planarians and killifish. The very tissues of greatest interest—the delicate, newly formed blastema and wound epidermis—are most vulnerable to damage from harsh chemical treatments. Traditional protocols that rely on proteinase K digestion or aggressive mucolytic agents often compromise this integrity, leading to tissue shredding and loss of morphological context. The NAFA protocol addresses this fundamental trade-off by enabling effective probe penetration while preserving fragile tissues, thereby ensuring that gene expression data can be accurately localized within an intact anatomical framework.

The NAFA Protocol: A Detailed Methodology

The Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) protocol is a significant advancement, eliminating the need for proteinase K digestion. This preserves protein epitopes for concurrent immunostaining and drastically improves the structural preservation of delicate tissues.

Primary Fixation with NAFA Solution

The following table summarizes the key components of the NAFA fixation solution and their specific functions within the protocol:

Table 1: Composition and Function of the NAFA Fixation Solution

| Component | Final Concentration | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Nitric Acid | 3% | Tissue permeabilization and macromolecule stabilization. |

| Formic Acid | 2% | Acts as a carboxylic acid to enhance tissue permeability. |

| EGTA | 1mM | Chelates calcium to inhibit nuclease activity, preserving RNA integrity. |

| Formaldehyde | 4% | Cross-links proteins and nucleic acids to preserve tissue structure. |

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Freshly prepare the NAFA fixation solution in a chemical fume hood.

- Fixation: Immerse tissue samples completely in the NAFA solution. The fixation duration is species- and size-dependent and must be empirically optimized.

- Rinsing: Following fixation, thoroughly rinse samples with a buffered solution like PBS to halt the fixation process and remove residual acids.

Permeabilization and Post-Fixation Handling

A key advantage of the NAFA protocol is that the primary fixation step achieves significant permeabilization, rendering a separate proteinase K digestion step unnecessary. This directly contributes to superior preservation of antigen epitopes for immunostaining and maintains the integrity of fragile tissues.

Subsequent Steps:

- Hybridization and Washes: Proceed with standard pre-hybridization, probe hybridization, and post-hybridization wash steps as required by your specific WISH protocol.

- Antibody Incubation: For tandem FISH and immunostaining, the preserved epitopes allow for effective antibody binding after the hybridization steps are complete.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The efficacy of the NAFA protocol is best demonstrated through direct comparison with established methods. The following table synthesizes qualitative and quantitative findings from validation studies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Fixation Protocols for WISH and Immunostaining

| Protocol | Tissue Preservation (Epidermis/Blastema) | WISH Signal Quality | Compatibility with Immunostaining | Key Differentiating Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFA | Excellent preservation; intact epidermis and blastema [2]. | Robust signal for internal (piwi-1) and external (zpuf-6) markers [2]. | High; brighter antibody signal (e.g., anti-H3P) due to no proteinase K [2]. | Nitric Acid + Formic Acid + EGTA. |

| NAC Protocol | Noticeable damage and shredding of delicate tissues [2]. | Robust WISH signal comparable to NAFA [2]. | Reduced; proteinase K digestion degrades target epitopes [2]. | N-Acetyl Cysteine + Proteinase K. |

| NA (Rompolas) Protocol | Excellent preservation, similar to NAFA [2]. | Very weak or absent WISH signal [2]. | Good for immunostaining alone [2]. | Nitric Acid without carboxylic acid. |

Experimental Workflow and Visual Guide

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points and steps in the NAFA protocol, contrasting it with traditional methods.

Diagram 1: A workflow comparing the NAFA and traditional fixation pathways, highlighting the critical advantage of the NAFA protocol in preserving tissue and enabling immunostaining.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the NAFA protocol and subsequent WISH relies on a core set of high-quality reagents. The following table catalogs these essential materials.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Fixation and Permeabilization

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| NAFA Fixation Solution | Primary fixative and permeabilization agent. | Must be prepared fresh. Contains strong acids; requires use in a fume hood. |

| EGTA Solution | Calcium chelation to protect RNA integrity from nucleases. | A critical additive for preserving target mRNA during fixation. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing and rinsing buffer; base for other solutions. | Used to stop fixation and for general dilution and washing steps. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Provides optimal conditions for probe binding to target mRNA. | Formulation varies but typically includes salts, Denhardt's solution, and dextran sulfate. |

| Formamide | Component of hybridization buffer. | Reduces hybridization temperature, stringency, and background. |

| Anti-Digoxigenin/ Fab Fragments | Antibody conjugate for chromogenic or fluorescent detection. | Binds to hapten-labeled (e.g., DIG) RNA probes for visualization. |

| NBT/BCIP | Chromogenic substrate for alkaline phosphatase. | Produces an insoluble purple precipitate for brightfield microscopy. |

The NAFA protocol represents a significant methodological improvement for complex gene expression studies in delicate tissues. By forgoing destructive proteinase K treatment in favor of a balanced acid-based permeabilization, it successfully resolves the classic tension between tissue preservation and probe accessibility. Its proven efficacy in diverse regenerative models like planarians and killifish underscores its robustness and recommends it as a new standard for fixation and permeabilization in whole-mount in situ hybridization workflows, particularly those requiring concomitant protein detection.

Step-by-Step Protocols: From Traditional Chromogenic to Modern Fluorescent HCR

Standard Double Colorimetric ISH Protocol for Zebrafish Embryos

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) is an indispensable technique for characterizing the spatial distribution of gene transcripts during embryonic development. The ability to visualize two transcripts simultaneously through double colorimetric ISH is particularly valuable for defining overlapping and abutting gene expression domains, which helps elucidate the molecular subdivisions of complex tissues like the developing vertebrate brain [20] [5]. In zebrafish embryos, this technique has been extensively used to compare numerous regulatory gene expression patterns, providing critical insights into developmental mechanisms [5].

This application note details a standardized protocol for double colorimetric ISH in zebrafish embryos, optimized to achieve high signal sensitivity and low background. The protocol combines the chromogenic substrates NBT/BCIP and Fast Red for sequential detection of two different RNA probes, typically labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) and fluorescein (FL), respectively [21]. We have incorporated key optimizations, including the use of dextran sulfate in the hybridization buffer to enhance signal intensity through molecular crowding effects and hydrogen peroxide treatment to improve embryo permeabilization for better probe and antibody access [5]. This method provides researchers with a robust framework for precise gene expression analysis.

Material and Reagent Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents and their functions required for successfully performing double colorimetric ISH in zebrafish embryos.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Double Colorimetric ISH in Zebrafish Embryos

| Reagent Category | Specific Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS [21] | Preserves tissue morphology and immobilizes nucleic acids within the embryo. |

| Permeabilization Agents | Proteinase K [21], Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [5] | Digests proteins to allow probe and antibody penetration into the tissue. |

| Hybridization Buffers & Components | Prehybridization Buffer (50% Formamide, 5x SSC, Heparin, Torula Yeast RNA) [22] [21], Dextran Sulfate [5] | Creates optimal stringency and blocking conditions for specific probe binding; dextran sulfate increases probe concentration via molecular crowding. |

| Probe Labels | Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes, Fluorescein (FL)-labeled RNA probes [22] [21] | Provides hapten labels for immunodetection of two distinct transcript targets. |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-DIG-Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), Anti-FL-Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [22] | Enzyme-conjugated antibodies that bind specifically to the probe labels. |

| Chromogenic Substrates | NBT/BCIP [22] [21], Fast Red [21] | AP substrates that yield a blue-purple (NBT/BCIP) or red (Fast Red) precipitate at the site of target gene expression. |

| Wash & Blocking Buffers | MABT, SSCT, Blocking Buffer (2% Roche Blocking Agent) [21] | Removes unbound reagents and blocks nonspecific binding sites to reduce background signal. |

The double colorimetric ISH protocol is a multi-day procedure involving specimen fixation, permeabilization, hybridization with labeled probes, and sequential chromogenic detection. A critical design principle is the order of detection: the first detection round is more sensitive [21]. Therefore, it is recommended to detect the weaker probe first using the DIG/NBT/BCIP system, followed by the stronger probe with the FL/Fast Red system [22] [21]. This sequence ensures optimal visualization of both transcripts. The schematic below outlines the complete experimental workflow.

Experimental Protocol

Detailed Step-by-Step Procedure

Day 1: Fixation, Permeabilization, and Hybridization

- Fixation: Fix dechorionated embryos overnight at 4°C in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [21].

- Dehydration: Wash embryos twice for 5 minutes in PBST (1x PBS with 0.1% Tween-20), followed by two 5-minute washes in 100% methanol. Incubate in fresh 100% methanol at -20°C for at least 1 hour or overnight for additional fixation and storage [21].

- Rehydration: Rehydrate the embryos through a series of washes: 5 minutes in 50% Methanol/50% PBST, then two 5-minute washes in PBST [21].

- Permeabilization:

- Treat with Proteinase K. The concentration and duration must be optimized for embryo age (e.g., ~10 µg/mL for 24 hpf embryos) [21].

- (Optional but recommended) To enhance permeability, treat fixed embryos with 2% hydrogen peroxide prior to Proteinase K digestion [5].

- Wash twice for 5 minutes in PBST.

- Re-fix in 4% PFA for 20 minutes at room temperature to maintain tissue integrity.

- Perform two final 5-minute washes in PBST.

- Pre-hybridization: Incubate embryos in pre-warmed prehybridization buffer (50% Formamide, 5x SSC, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.5 mg/mL torula yeast RNA, 50 µg/mL Heparin) for a minimum of 1 hour at 68°C [21]. For increased signal strength, include 5% dextran sulfate in the hybridization buffer [5].

- Hybridization: Replace the prehybridization buffer with fresh hybridization buffer containing both the DIG- and FL-labeled probes (typically 1 µL of each probe per 500 µL buffer). Incubate overnight at 68°C [22] [21].

Day 2: Stringency Washes and First Antibody Detection

- Stringency Washes: Pre-heat all wash buffers to 68°C. Perform the following sequential washes to remove unbound probe:

- 5 minutes in Hyb(-) (50% Formamide, 5x SSC, 0.1% Tween-20).

- Three times for 10 minutes in 25% Hyb(-) / 75% 2x SSCT.

- 5 minutes in 2x SSCT.

- Two times for 30 minutes in 0.2x SSCT.

- Switch to room temperature. Wash for 5 minutes in a 50:50 mix of 0.2x SSCT and MABT.

- Wash 5 minutes in MABT [21].

- Blocking: Incubate embryos in blocking buffer (2% Roche Blocking Agent in MABT) for at least 1 hour [21].

- First Antibody Incubation: Incubate embryos overnight at 4°C with anti-DIG-AP antibody, pre-absorbed if necessary, diluted in blocking buffer (typical dilution between 1:4000 to 1:10000) [22] [21].

Day 3: Chromogenic Development and Second Detection

- Post-Antibody Washes: Wash the embryos thoroughly to remove unbound antibody: 4 times for 15 minutes in MABT, followed by 2 times for 10 minutes in NTMT (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl₂, 100 mM Tris pH 9.5, 0.1% Tween-20, 5 mM Levamisol) [21].

- First Color Development (DIG probe): Transfer embryos to a multi-well plate and replace the NTMT with NBT/BCIP staining solution. Allow the blue-purple chromogenic reaction to develop in the dark, monitoring periodically until the desired signal intensity is achieved. Stop the reaction by washing several times with PBT [22] [21].

- Antibody Inactivation: Fix the embryos in 4% PFA for one hour at room temperature. This critical step inactivates the first antibody and prevents cross-reactivity in the second detection round [22].

- Second Antibody Incubation & Detection (FL probe):

- Wash embryos several times in PBT.

- Block in blocking buffer for 1 hour.

- Incubate with anti-FL-AP antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- On Day 4, repeat the post-antibody wash steps (washes in MABT followed by NTMT).

- For the second color development, use the Fast Red substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions until the red precipitate forms [22] [21].

- Post-staining and Imaging: Perform final washes in PBT. For imaging, embryos can be mounted in a glycerol-based solution or dehydrated and stored in ethanol. Image using a brightfield microscope [21].

Critical Timings and Parameters

Table 2: Key Optimization Parameters for Double Colorimetric ISH

| Protocol Step | Critical Parameter | Recommended Guideline | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeabilization | Proteinase K concentration & time | Age-dependent; must be empirically determined (e.g., ~10 µg/mL for 24 hpf) [21] | Prevents over-digestion (tissue damage) or under-digestion (weak signal). |

| Hybridization | Addition of Dextran Sulfate | 5% in hybridization buffer [5] | Molecular crowding effect increases local probe concentration, enhancing signal strength. |

| Probe Detection Order | Sequence of antibody application | Detect weaker probe first (with DIG/NBT/BCIP) [22] [21] | The first detection round is more sensitive, ensuring visualization of low-abundance transcripts. |

| Color Development | Substrate reaction monitoring | Monitor visually; can be slowed by placing at 4°C [21] | Prevents over-development, which increases background, or under-development, which yields weak signal. |

Technical Optimization and Troubleshooting

Even with a standardized protocol, optimization for specific probes and experimental conditions is often necessary. The table below outlines common challenges and evidence-based solutions derived from the referenced literature.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Double Colorimetric ISH

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Non-specific probe/antibody binding; insufficient washing. | Increase stringency of post-hybridization washes (e.g., lower SSC concentration, higher temperature) [23]. Include blocking agents (heparin, torula RNA) in hybridization buffer [22] [23]. Use MABT for washes after hybridization to reduce background [21]. |

| Weak or No Signal | Poor probe penetration or concentration; low transcript abundance. | Optimize permeabilization with H₂O₂ pre-treatment [5]. Increase probe concentration and include 5% dextran sulfate in hybridization [5]. Extend substrate development time, particularly for the second probe [5]. |

| Uneven Staining | Uneven probe distribution; drying of embryos during hybridization. | Ensure embryos are fully submerged and tubes are horizontal on a shaker during all steps [21]. Use adequate volume of hybridization buffer and a properly sealed, humidified chamber to prevent evaporation [23]. |

| Loss of Morphology | Over-digestion with Proteinase K. | Precisely calibrate Proteinase K treatment time for embryo age and batch. Perform a time-course experiment. Stop digestion promptly with a glycine wash if needed [21]. |

Implementing Serial Stain-and-Strip Methods for Multiple Targets

Within the advancing field of multiplexed tissue analysis, the ability to visualize multiple biomarkers on a single sample is crucial for understanding complex cellular interactions, especially in the tumor microenvironment [24]. While techniques like multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) and digital spatial profiling offer powerful solutions, their implementation can be hindered by requirements for specialized, costly platforms not available to most clinical laboratories [24]. Serial stain-and-strip methods present a viable and effective alternative, enabling researchers to sequentially label, image, and remove multiple targets on the same whole-mount specimen. This protocol details a rigorous framework for implementing these methods, ensuring the generation of high-quality, reproducible data for drug development and diagnostic research.

The core principle involves the cyclic application of fluorescent probes, followed by high-resolution image acquisition and subsequent gentle stripping of antibodies to preserve antigen integrity for the next round of staining. This approach, when performed with rigor, allows for the comprehensive mapping of numerous targets within a single biological sample, thereby maximizing the informational yield from precious specimens [24]. The following sections provide a detailed application note and protocol, designed with reproducibility at its core, to guide researchers through the critical steps of experimental design, execution, and quantitative analysis.

Experimental Design and Workflow

A successful serial stain-and-strip experiment requires meticulous pre-planning to minimize bias and ensure statistical rigor. A predefined acquisition and analysis pipeline, established through preliminary trials, is essential to avoid post-hoc data manipulation and biased conclusions [25].

The entire process, from sample preparation to final data integration, is visualized in the following workflow diagram. Adherence to this structured pathway is critical for maintaining sample integrity and data validity throughout the multi-cycle procedure.

Key Design Considerations

- Bias Mitigation: To prevent experimenter bias, predefine all imaging areas. Use software to capture images from fixed or randomly selected locations within a well or across the entire sample in a tiled manner, ensuring comprehensive and unbiased sampling [25].

- Controls are Critical: Each staining cycle must include appropriate controls. These are "no primary antibody" controls to assess specificity and, crucially, a "no-strip" control to confirm the complete removal of signal before proceeding to the next cycle [25].

- Statistical Power: Collaborate with a biostatistician during the experimental design phase to determine the necessary sample size and number of biological replicates required for sufficient statistical power [25]. Preliminary data should be used to establish this pipeline but not included in the final analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents

The following table lists the essential research reagent solutions required for the serial stain-and-strip protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Specifically binds to target antigens of interest. | Use antibodies confirmed for IHC/IF in your sample type. Conjugate-free for sequential staining. |

| High-Fidelity Fluorescent Secondaries | Visualizes primary antibody binding. | Use bright, stable fluorophores (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes). Select from different animal hosts to prevent cross-reactivity [25]. |

| Antibody Elution Buffer | Gently dissociates antibodies from antigens between cycles while preserving tissue morphology and antigenicity for subsequent rounds. | Common formulations include glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) or commercial stripping buffers. |

| Antigen Retrieval Solution | Re-exposes epitopes masked by fixation. | Citrate-based (pH 6.0) or Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) solutions. Optimization may be required for different targets. |

| Blocking Solution | Reduces nonspecific binding of antibodies. | Typically contains serum from the same species as the secondary antibody and a detergent like Triton X-100. |

| Mounting Medium | Preserves samples and reduces photobleaching during imaging. | Use an anti-fade medium (e.g., with DABCO or commercial equivalents) [25]. |

Step-by-Step Staining and Stripping Protocol

Sample Preparation and Initial Staining:

- Perform standard antigen retrieval on fixed whole-mount samples appropriate for your tissue type.

- Block samples with a suitable blocking solution for 1-2 hours at room temperature to minimize background.

- Incubate with the first primary antibody (Target A) overnight at 4°C.

- The following day, wash thoroughly and incubate with the corresponding fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 1-2 hours at room temperature, protected from light.

Image Acquisition (Cycle 1):

- Acquire high-resolution images of the stained samples for Target A. Adhere to the Shannon-Nyquist criterion for optimal spatial sampling, as calculated by your acquisition software, to ensure no resolution is lost [25].

- To obtain quantitative images, avoid pixel saturation and maximize the dynamic range for optimal contrast [25]. Maintain consistent focus, light intensity, and environmental factors (e.g., temperature, CO₂) across all imaging sessions.

- Save the images with precise metadata, including all acquisition parameters.

Antibody Elution (Stripping):

- Immerse the slide or sample in a pre-validated antibody elution buffer. A common method is using 0.2 M Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) for 10-20 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Wash the sample extensively in PBS or a neutral pH buffer to remove the stripping solution and eluted antibodies completely.

Stripping Validation (Critical Quality Control Step):

- Re-image the sample using the exact same microscope settings and channels used in Step 2.

- Quantitatively analyze the resulting image. The fluorescent signal must be reduced to background levels. If residual signal is detected, the stripping cycle must be repeated until the validation check passes [25].

Subsequent Staining Cycles:

- Once stripping is validated, proceed to the next cycle by returning to Step 1 for the next target (Target B).

- Repeat the process of staining, imaging, and stripping for each additional target. Always perform the validation step between cycles.

Final Image Processing and Analysis:

- Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Fiji, or commercial platforms) to coregister all images from different cycles based on fiduciary markers or tissue landmarks.

- Generate a final multiplex image by overlaying the individually acquired channels.

- Perform quantitative and spatial analysis on the coregistered multiplex image data [24].

Quantitative Data and Validation

Rigor in image acquisition and processing is paramount for generating reliable, quantitative data. The following table summarizes key metrics and controls that must be tracked throughout the experiment.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics and Validation Controls

| Parameter | Optimal Value / Target | Measurement Method / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Maximized, > 3:1 | Compare mean signal intensity in the region of interest (ROI) to mean background intensity. Ensures detectable specific signal [25]. |

| Stripping Efficiency | > 95% signal reduction | Compare mean signal intensity in the target channel post-stripping to the pre-stripping intensity. Critical for protocol validity [25]. |

| Antigen Integrity | Preserved signal in re-stained cycle | Re-stain a previously stripped target in a final cycle. Confirms antigens remain detectable after elution treatments. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | < 10-15% between replicates | Measure of technical reproducibility across multiple samples or imaging sessions [25]. |

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Aim for > 95% concordance | Compare automated or multiplexed results to a validated gold-standard method, as demonstrated in automated FISH validation studies [26]. |

Data Rigor and Reproducibility

- Hardware Calibration: Regularly confirm that the microscope light source is aligned and provides even illumination. Check the overlay and registration of different fluorescence channels using multicolor fluorescent beads [25].

- Image Quality: To increase signal, use bright, stable fluorophores and high numerical aperture (NA) objectives. To decrease noise, use phenol-red free media and reduce detector gain where possible [25].