Nodal Signaling in Zebrafish Mesendodermal Patterning: From Molecular Mechanisms to Research Applications

This comprehensive review explores the pivotal role of Nodal signaling in zebrafish mesendoderm induction and patterning, providing researchers and drug development professionals with current mechanistic insights and practical methodologies.

Nodal Signaling in Zebrafish Mesendodermal Patterning: From Molecular Mechanisms to Research Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the pivotal role of Nodal signaling in zebrafish mesendoderm induction and patterning, providing researchers and drug development professionals with current mechanistic insights and practical methodologies. We examine foundational principles including ligand-receptor interactions, feedback regulation, and maternal control of Nodal gene expression. The article details cutting-edge techniques for manipulating and monitoring Nodal signaling, addresses common experimental challenges, and validates zebrafish as a powerful model for studying TGF-β signaling pathways relevant to human development and disease.

Core Mechanisms of Nodal Signaling in Mesendoderm Formation

The Nodal signaling pathway is a cornerstone of vertebrate body plan establishment, with its components orchestrating a complex sequence of patterning events during early embryogenesis. In zebrafish, the Nodal-related ligands Squint (Sqt/Ndr1), Cyclops (Cyc/Ndr2), and Southpaw (Spaw/Ndr3) function through a sophisticated receptor complex to induce and pattern the mesoderm and endoderm. This technical review synthesizes current understanding of their distinct and overlapping functions, quantitative phenotypic outcomes, receptor interactions, and experimental methodologies. Framed within the broader context of mesendodermal patterning research, we provide structured data compilations, signaling pathway visualizations, and essential research tools to facilitate advanced investigation of this critical developmental pathway.

Nodal ligands, belonging to the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, are secreted cytokines that play indispensable roles in zebrafish embryogenesis. The three zebrafish Nodal ligands—Squint (Sqt), Cyclops (Cyc), and Southpaw (Spaw)—exhibit distinct yet partially redundant functions in establishing the embryonic axes and germ layers [1] [2]. These signals are transduced through a conserved receptor complex comprising Type I (Acvr1) and Type II (Acvr2) Activin receptors, alongside the essential EGF-CFC family co-receptor One-eyed pinhead (Oep) [3] [4]. Signal activation initiates an intracellular phosphorylation cascade culminating in Smad2/3 translocation to the nucleus and regulation of target gene expression. The precise spatiotemporal control of this pathway is critical for normal development; its disruption leads to severe defects including loss of mesendodermal tissues, cyclopia, and impaired left-right asymmetry [5] [6]. This review systematically examines the specialized functions of each ligand, their integrated operation within the signaling network, and the experimental frameworks used for their investigation.

Core Ligands: Functions, Expression, and Phenotypes

Squint (Sqt/Ndr1)

Squint functions as a potent long-range morphogen during early blastula stages. Maternal Sqt transcripts are deposited in the oocyte and are later joined by zygotic expression at the blastula margin, forming a signaling gradient that patterns the mesendoderm [1] [7]. Unlike other Nodal ligands, Sqt exhibits unique long-range signaling activity and contains an evolutionarily conserved 3' untranslated region (UTR) that facilitates dorsal targeting of its mRNA [1]. The penetrance of sqt mutant phenotypes is notably variable and influenced by genetic modifiers and environmental factors such as temperature, suggesting Sqt may provide evolutionary advantage by buffering embryos against genetic and environmental perturbations [1].

Table 1: Zebrafish Nodal Ligands: Functions and Mutant Phenotypes

| Ligand | Primary Functions | Expression Dynamics | Mutant Phenotypes | Genetic Redundancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squint (Sqt/Ndr1) | Mesendoderm induction, Dorsal organizer formation, Long-range patterning | Maternal and zygotic; blastula margin, dorsal lineage | Variable: delayed organizer formation, cyclopia, loss of ventral brain; viable adults to lethal | Partially redundant with Cyc |

| Cyclops (Cyc/Ndr2) | Mesendoderm formation, Ventral neural tube, Floor plate specification | Zygotic; blastula margin, midline mesendoderm | Cyclopia, loss of ventral diencephalon and floor plate, left-right defects; lethal | Partially redundant with Sqt |

| Southpaw (Spaw/Ndr3) | Left-right asymmetry establishment | Late segmentation; left lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) | Situs inversus, heart looping defects | Specialized function |

Cyclops (Cyc/Ndr2) and Southpaw (Spaw/Ndr3)

Cyclops acts predominantly as a short-range signal with expression initiating in mesendoderm precursor cells during the blastula stage and persisting in midline structures throughout gastrulation [1] [7]. While Cyc and Sqt show functional redundancy in mesendoderm induction, Cyc has unique essential functions in patterning the ventral neural tube and establishing the floor plate [5]. In contrast to the incomplete penetrance of sqt mutants, cyc deficiency produces fully penetrant cyclopia and embryonic lethality [1]. Southpaw functions predominantly after gastrulation, exhibiting left-sided expression in the lateral plate mesoderm where it directs the establishment of left-right asymmetry for visceral organ patterning [2] [6]. Unlike the early widespread functions of Sqt and Cyc, Spaw activity is temporally and spatially restricted to later asymmetry determination.

Quantitative Phenotypic Analysis

Table 2: Quantitative Phenotypes in Nodal Signaling Mutants

| Genotype / Condition | Mesendoderm Defects | Cyclopia Penetrance | Neural Tube Defects | Left-Right Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sqt (zygotic) | Mild to severe (dose-dependent) | Incomplete (13-34% in adults) | Variable: elongated/divided pineal | Not reported |

| cyc (zygotic) | Moderate (ventral CNS) | Complete (100%) | None (round pineal) | Randomized |

| sqt; cyc double mutant | Complete loss | Complete (100%) | Not specified | Not specified |

| MZoep | Complete loss | Complete (100%) | Severe (widely separated pineal) | Not specified |

| acvr1b-a; acvr1b-b double mutant | Complete loss | Complete (100%) | Not specified | Not specified |

| SB-431542 treatment | Complete loss | Complete (100%) | Not specified | Not specified |

Receptor Complexes and Signaling Mechanisms

Nodal signal transduction is mediated by a sophisticated cell surface receptor system. The core complex includes Type I receptors (Acvr1b-a, Acvr1b-b), Type II receptors (Acvr2a, Acvr2b-a, Acvr2b-b), and the indispensable EGF-CFC co-receptor Oep [3] [4]. Upon ligand binding, Type II receptors phosphorylate Type I receptors, which subsequently activate the downstream Smad2/3 transcription factors. The co-receptor Oep plays a particularly critical role beyond simple signal facilitation; it regulates the spatial distribution of Nodal ligands by controlling their extracellular diffusion and enhancing cellular sensitivity to the signals [3]. Recent genetic analyses reveal that Type I receptors Acvr1b-a and Acvr1b-b function redundantly as the primary mediators of Nodal signaling, while Type II receptors exhibit both Nodal-dependent and independent functions in embryonic patterning [4].

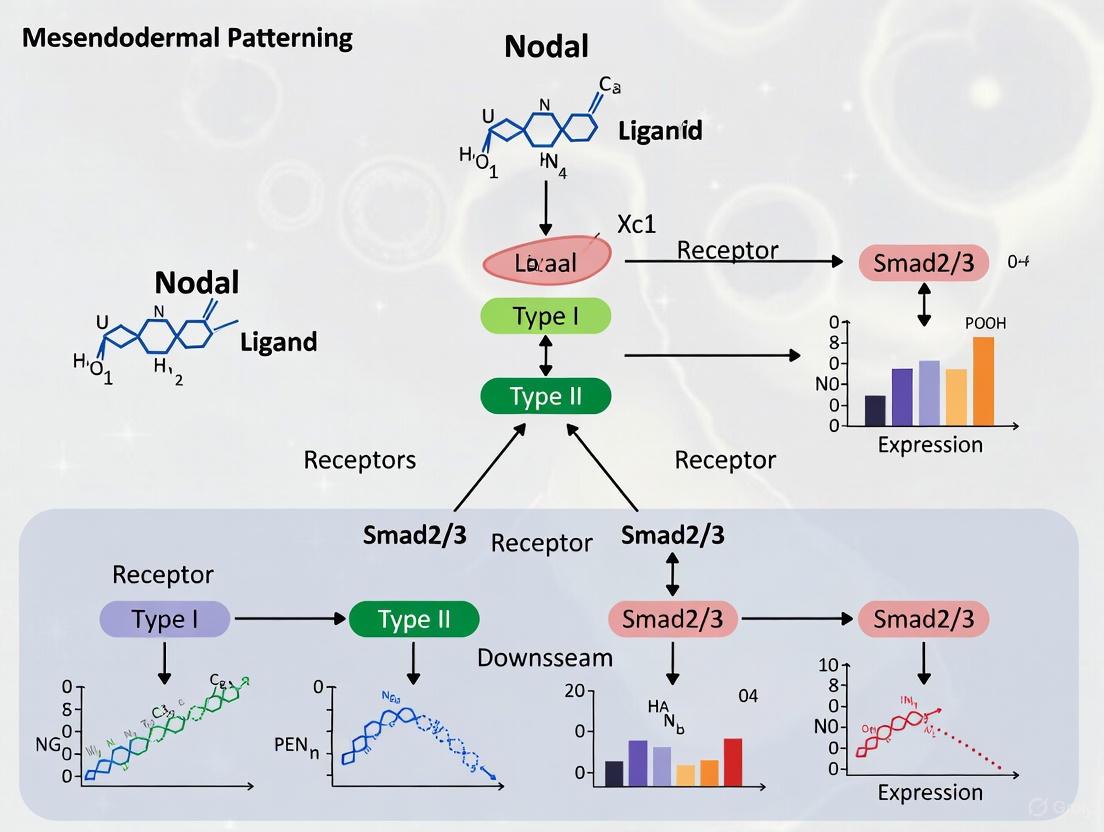

Nodal Signaling Pathway and Key Components: This diagram illustrates the core Nodal signaling pathway in zebrafish, from ligand-receptor binding to target gene activation, including regulatory feedback mechanisms.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genetic Loss-of-Function Strategies

Genetic analysis remains fundamental to Nodal pathway investigation. Maternal-zygotic mutants provide the most complete loss-of-function scenarios, as in MZoep mutants which lack both maternally deposited and zygotically expressed gene products, resulting in complete absence of mesendoderm [5]. Compound mutants reveal functional redundancy; while single sqt or cyc mutants show specific defects, sqt;cyc double mutants display complete absence of mesoderm and endoderm, demonstrating their collective essential role [7]. CRISPR/Cas9-generated mutants have enabled precise dissection of receptor functions, revealing that simultaneous knockout of both acvr1b-a and acvr1b-b Type I receptors is required to recapitulate the complete Nodal loss-of-function phenotype [4].

Pharmacological Inhibition

Small molecule inhibitors provide temporal control over Nodal signaling disruption. SB-431542 and SB-505124 specifically target the kinase activity of ALK4/5/7 Type I receptors, completely blocking signal transduction when applied after the mid-blastula transition [7]. This pharmacological approach demonstrated that Nodal signaling is required during a specific competency window from mid-to-late blastula stages (3-5 hours post-fertilization) for sequential specification of mesendodermal derivatives [7]. Treatment with 800 μM SB-431542 produces phenotypes indistinguishable from sqt;cyc double mutants, confirming its efficacy as a Nodal pathway inhibitor [7].

Quantitative Imaging and Gradient Analysis

Advanced imaging techniques have revealed the biophysical properties of Nodal morphogen gradients. Fluorescently tagged ligands (e.g., Sqt-GFP, Cyc-GFP) enable direct visualization of ligand distribution, demonstrating that Sqt has greater effective range than Cyc [3]. These studies revealed that the co-receptor Oep restricts Nodal spread through receptor-mediated capture, shaping the morphogen gradient that patterns the germ layers [3]. Computational modeling combined with live imaging shows that without Oep replenishment, the Nodal gradient transforms into a traveling wave, highlighting the dynamic regulation of signaling distribution [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Nodal Signaling Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Application | Key Characteristics / Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SB-431542 | Small molecule inhibitor | Temporal disruption of Nodal signaling | Inhibits ALK4/5/7 receptors; blocks signaling after MBT |

| Sqt, Cyc, Spaw mutants | Genetic models | Loss-of-function studies | Alleles: sqtcz35, sqthi975 (predicted nulls) |

| Oep (MZoep) mutants | Genetic model | Complete pathway blockade | Lacks maternal and zygotic Oep; no mesendoderm |

| Acvr1b-a; Acvr1b-b double mutants | Genetic model | Receptor function studies | Phenocopies Nodal loss-of-function |

| Sqt/Cyc-GFP fusions | Imaging tools | Ligand distribution studies | Measures diffusion coefficients and gradient formation |

| gdf3 mutants | Genetic model | Co-ligand function analysis | Maternal-zygotic mutants show reduced Nodal signaling |

| Nodal receptor morpholinos | Knockdown tools | Acute protein depletion | Combinatorial F0 knockdown for receptor analysis |

Regulatory Networks and Co-factors

Nodal signaling operates within a sophisticated regulatory network featuring multiple feedback mechanisms. Positive feedback amplifies the initial signal, as Nodal ligands induce their own expression as well as that of their co-factors [3] [2]. Negative feedback occurs through the induction of Lefty antagonists, which diffuse rapidly to restrict signal range and prevent overactivation [3]. The TGF-β family member Gdf3 (Vg1 ortholog) serves as an essential co-ligand, forming heterodimers with Sqt and Cyc to enhance signaling robustness [6]. Maternal depletion of Gdf3 results in severe reduction of Nodal signaling, demonstrating its role as a critical modulator rather than a redundant component [6].

Nodal Gradient Formation and Regulation: This diagram illustrates how the Nodal signaling gradient is established through diffusion from its source and shaped by co-receptor binding and feedback inhibition.

The zebrafish Nodal signaling pathway, with its sophisticated repertoire of ligands, receptors, and regulatory mechanisms, provides a powerful model system for understanding vertebrate embryonic patterning principles. The functional specialization of Squint, Cyclops, and Southpaw—despite their structural similarities—demonstrates how gene duplication and divergence can generate complexity in developmental networks. From a technical perspective, the comprehensive toolkit of genetic mutants, pharmacological inhibitors, and quantitative imaging approaches enables precise dissection of this essential pathway. Understanding these mechanisms has broader implications for regenerative medicine and disease modeling, particularly given the re-emergence of Nodal signaling in tumorigenesis and its role in maintaining stem cell pluripotency. Future research will likely focus on quantitative modeling of signal dynamics, single-cell analysis of cellular responses, and translational applications targeting Nodal signaling in cancer therapeutics.

This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the maternal regulation of Nodal signaling, a pivotal pathway in zebrafish mesendodermal patterning. We elucidate the essential and complementary roles of the maternal T-box transcription factor Eomesodermin A (Eomesa) and Huluwa (Hwa)-activated β-catenin signaling in the spatiotemporal initiation of zygotic ndr1 (squint) and ndr2 (cyclops) expression. While Hwa/β-catenin is the primary activator of ndr1 on the dorsal side, maternal Eomesa is crucial for its expression in the lateroventral margin and is the major regulator of ndr2. This guide provides a detailed dissection of the experimental evidence, including comprehensive quantitative data and methodologies, which together establish a model wherein maternal factors orchestrate a precise Nodal signaling landscape to ensure robust mesendoderm induction.

In vertebrate embryogenesis, the establishment of the body plan hinges on the precise specification of mesodermal and endodermal tissues, a process known as mesendodermal patterning. The Nodal signaling pathway, belonging to the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, is the principal inducer of this process across species, from sea urchins to mammals [8] [9]. In zebrafish, the Nodal-related genes ndr1/squint and ndr2/cyclops are redundantly required for the formation of most mesodermal and endodermal tissues; simultaneous deficiency of both genes leads to a near-complete loss of these germ layers [10] [8]. The regulation of ndr1 and ndr2 expression is therefore a critical control point in development. Following fertilization, early zebrafish development is directed by maternal gene products deposited into the egg. The transition to zygotic control occurs at the Mid-Blastula Transition (MBT), and it is at this juncture that maternal factors directly activate the expression of zygotic genes, including the nodal genes [10]. This whitepaper focuses on two key maternal determinants—Eomesodermin and the Hwa/β-catenin signaling axis—and their interplay in controlling the Nodal landscape that patterns the zebrafish embryo.

Maternal Regulators of Nodal Expression

Eomesodermin (Eomesa): A Versatile Maternal Determinant

Eomesodermin A (Eomesa) is a maternally expressed T-box transcription factor. Its transcripts are distributed in a vegetal-to-animal gradient during cleavage stages, prefiguring its role in marginal cell fates [10] [11]. Beyond its well-documented synergy with Bon and Gata5 to induce the endoderm marker cas (sox32) [12], Eomesa is a fundamental upstream regulator of Nodal gene expression. Genetic studies using maternal-zygotic eomesa mutants (Meomesa) revealed that Eomesa is indispensable for the initial expression of ndr2 and for the lateroventral expression of ndr1 [10]. This positions Eomesa as a functional counterpart to the Xenopus T-box factor VegT, which is known to activate Nodal-related genes [10].

Hwa/β-catenin Signaling: The Dorsal Initiator

The dorsal-vental axis in zebrafish is established through the activity of the maternal factor Huluwa (Hwa), which encodes a transmembrane protein essential for stabilizing β-catenin on the future dorsal side of the embryo [10]. Mutants lacking maternal hwa (Mhwa) are severely ventralized, phenocopying β-catenin deficient mutants [10]. This Hwa/β-catenin signaling pathway acts as a major dorsal activator of ndr1 expression. The requirement for β-catenin signaling in dorsal Nodal induction demonstrates a conserved mechanism with Xenopus, where nuclear β-catenin synergizes with VegT to enhance Nodal expression [10].

Integrated Model of Regulation

The genetic interaction between these pathways was definitively established using Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants. In these embryos, the expression of both ndr1 and ndr2 is completely abolished, indicating that the functions of maternal Eomesa and Hwa are together essential for the initiation of Nodal signaling [10]. However, these factors contribute differentially to the expression of each Nodal gene and across different regions of the embryo, as detailed in the quantitative analysis below.

Quantitative Analysis of Genetic Interactions

The distinct and overlapping contributions of maternal Eomesa, Hwa/β-catenin, and Nodal autoregulation to ndr1 and ndr2 expression are quantified and summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Relative Contributions of Maternal Factors to ndr1 and ndr2 Expression

| Gene | Dorsal Margin Expression | Lateroventral Margin Expression | Primary Regulator | Secondary Regulator(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ndr1 (squint) |

Severely reduced or absent in Mhwa mutants [10] |

Severely reduced or absent in Meomesa mutants [10] |

Hwa/β-catenin (dorsal); Eomesa (lateroventral) [10] | Nodal autoregulation (ventral expansion) [10] |

ndr2 (cyclops) |

Minor reduction in Mhwa mutants [10] |

Severely reduced or absent in Meomesa mutants [10] |

Maternal Eomesa [10] | Minor contribution from Hwa/β-catenin and Nodal autoregulation [10] |

Table 2: Phenotypic Consequences of Mutations in Maternal and Nodal Pathway Components

| Genotype / Condition | Mesendoderm Phenotype | Key Molecular Deficits |

|---|---|---|

MZoep (No Nodal co-receptor) |

Near-complete loss of mesoderm and endoderm; failure of neural tube closure [5] [9] | Absence of ndr1 and ndr2 signaling [9] |

Meomesa |

Defects in endoderm marker expression; delayed epiboly initiation [11] | Loss of lateroventral ndr1 and most ndr2 expression [10] |

Mhwa |

Severe ventralization (Class I) [10] | Loss of dorsal ndr1 expression [10] |

Meomesa;Mhwa |

Synthetic severe phenotype | Complete abolition of ndr1 and ndr2 expression [10] |

| Nodal Inhibition (SB431542) | Disruption of mesendodermal patterning [10] | Reduced ventral expansion of ndr1 domain [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Genetic Dissection Using Maternal Mutants

Objective: To determine the individual and combined requirements of maternal eomesa and hwa in the spatiotemporal regulation of zygotic ndr1 and ndr2 expression.

Methodology:

- Zebrafish Strains: The following mutant lines were utilized:

- Generation of Maternal-Zygotic Mutants:

- Maternal

eomesa(Meomesa): Homozygouseomesamutant females were generated and their eggs, devoid of functional maternal Eomesa protein, were fertilized with mutant sperm [11]. - Maternal

hwa(Mhwa): A similar strategy was employed usinghwamutant females [10]. - Double Mutants (

Meomesa;Mhwa): Double heterozygotes (eomesa tsu007/+ ;hwa tsu01sm/+) were crossed to generate double homozygous mothers [10].

- Maternal

- Spatiotemporal Expression Analysis:

- Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH): Embryos were collected at specific developmental stages (e.g., 3.3 hpf to shield stage) and fixed. Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes for

ndr1andndr2were used to visualize transcript localization [10] [11]. - Pharmacological Inhibition: The small molecule SB431542, a specific inhibitor of the Activin/Nodal type I receptor ALK4, was used to treat wild-type and mutant embryos to assess the contribution of Nodal autoregulation to its own expression domains [10].

- Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH): Embryos were collected at specific developmental stages (e.g., 3.3 hpf to shield stage) and fixed. Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes for

Molecular Analysis of the Eomesa Nexus

Objective: To define the molecular mechanism by which Eomesa integrates Nodal signaling and endoderm specification.

Methodology:

- Gel Shift Assays (EMSA): Recombinant Eomesa protein or embryo extracts were incubated with a labeled DNA probe containing a T-box binding site from the

caspromoter. Supershift or competition with unlabeled wild-type/mutant oligonucleotides confirmed specific binding [12]. - Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Plasmids expressing Eomesa, Bon, and Gata5 were transfected into cultured cells. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against one factor (e.g., Eomesa) and the immunoblot was probed for the others (e.g., Bon and Gata5) to demonstrate direct physical interaction [12].

- Promoter-Reporter Assays: Wild-type and mutant versions of the

caspromoter (e.g., with a mutated Eomesa binding site) were cloned upstream of a luciferase reporter gene. These constructs were injected into zebrafish embryos, with or without co-injection ofeomesamRNA, and luciferase activity was measured to assess transcriptional synergy [12].

Signaling Pathway and Regulatory Logic

The following diagram synthesizes the complex regulatory interactions between maternal factors, Nodal genes, and their downstream targets as established in the cited research.

Diagram 1: Maternal and Regulatory Control of Nodal Signaling. This diagram illustrates the primary pathways through which maternal Hwa/β-catenin and maternal Eomesa activate the expression of the Nodal genes ndr1 and ndr2. The resulting Nodal ligand signals through a receptor complex requiring the EGF-CFC co-receptor Oep, leading to the formation of an active Smad/FoxH1 complex. This complex drives the expression of mesendoderm target genes and reinforces Nodal expression through a positive feedback loop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table catalogues essential reagents used in the featured studies to facilitate experimental replication and further investigation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Maternal Control of Nodal Signaling

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Key Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

eomesa tsu007/fh105 |

Mutant Allele | CRISPR/TILLING-generated loss-of-function mutants for dissecting maternal vs. zygotic roles [10] [11] | Generation of maternal-zygotic (Meomesa) mutants to analyze ndr2 expression [10] |

hwa tsu01sm |

Mutant Allele | Loss-of-function mutant to disrupt maternal β-catenin signaling and dorsal axis specification [10] | Generation of Mhwa mutants to assess dorsal-specific ndr1 loss [10] |

| SB431542 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Selective inhibitor of the TGF-β/Activin/Nodal type I receptor ALK4/5/7 [10] | Inhibition of Nodal autoregulation to study its role in ndr1 expression domain maintenance [10] |

| Anti-Eomesa Antibody | Custom Antibody | Polyclonal antibody for protein detection via Western Blot and whole-mount immunohistochemistry [11] | Confirmation of Eomesa protein loss in mutant embryos and analysis of its expression gradient [11] |

ndr1/sqt & ndr2/cyc RNA Probes |

In Situ Hybridization Probe | Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA for spatial visualization of transcript expression [10] [11] | Mapping the dynamic expression domains of ndr1 and ndr2 in wild-type and mutant embryos [10] |

| OptoNodal2 System | Optogenetic Tool | Light-controllable Nodal receptor system for high-resolution spatial/temporal perturbation of signaling [13] | Creating synthetic Nodal signaling patterns to study fate decision-making in live embryos [13] |

The body of research synthesized in this whitepaper firmly establishes that the maternal factors Eomesodermin and Hwa/β-catenin are non-redundant, upstream initiators of the Nodal signaling cascade in zebrafish. They act as regional specialists—Hwa/β-catenin on the dorsal side and Eomesa broadly throughout the margin with a predominant role for ndr2—to combinatorially ensure the precise onset of ndr1 and ndr2 expression, thereby launching the mesendodermal gene regulatory network.

Future research will likely focus on several frontiers. First, identifying the direct transcriptional targets of Eomesa and β-catenin at the ndr1 and ndr2 promoters will provide a more precise molecular understanding of their activation mechanisms. Second, the integration of new technologies, such as the improved OptoNodal2 system [13], will enable researchers to move beyond static loss-of-function studies and actively probe how dynamic Nodal signaling patterns are interpreted by embryonic cells. Finally, investigating the robustness of this network, particularly the role of feedback inhibitors like Lefty within the activator-inhibitor motif [14], will be crucial for understanding how this critical developmental system buffers against genetic and environmental variability. For drug development professionals, the exquisite regulation of Nodal signaling offers a paradigm for understanding how morphogen pathways can be targeted, with implications for regenerative medicine and cancer biology, where Nodal signaling is often reactivated.

The formation of mesoderm and endoderm (mesendoderm) in the early zebrafish embryo is orchestrated by a finely-tuned signaling system centered on Nodal proteins, a subset of the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily [8] [15]. A defining feature of this system is a negative feedback loop wherein Nodal signaling activates the expression of its own inhibitors, the Lefty proteins [16] [8]. This activator-inhibitor relationship is considered a paradigm for how feedback inhibition controls pattern formation in vertebrate development [16]. The core circuitry involves Nodal ligands such as Squint (Sqt) and Cyclops (Cyc) promoting their own transcription (autoregulation) while simultaneously inducing the expression of Lefty1 and Lefty2, which in turn diffuse and inhibit Nodal signaling extracellularly [16] [17]. This review synthesizes current research on the mechanisms and functional significance of this feedback loop, with a specific focus on its critical role in ensuring robust zebrafish mesendodermal patterning.

Core Molecular Mechanisms of the Nodal/Lefty Feedback Loop

Nodal Signaling and Autoregulation

Nodal signaling is initiated when a mature Nodal ligand (e.g., Squint or Cyclops) binds to a cell-surface receptor complex. This complex consists of Type I and Type II Activin serine/threonine kinase receptors and an essential EGF-CFC co-receptor (One-eyed pinhead, Oep, in zebrafish) [8] [18] [15]. Ligand binding leads to the phosphorylation of the intracellular signal transducers Smad2 and Smad3. These phosphorylated Smads form a complex with Smad4, which translocates to the nucleus [8] [18]. Within the nucleus, this Smad complex associates with transcription factors such as FoxH1 to activate the expression of target genes [18] [15]. Critically, these target genes include the squint and cyclops genes themselves, establishing a positive autoregulatory loop that amplifies and sustains Nodal signaling [8]. This same transcriptional complex also activates the expression of the lefty genes, instigating the negative feedback arm of the circuit [16].

Lefty-Mediated Inhibition

The Lefty proteins (Lefty1 and Lefty2) are divergent, secreted members of the TGF-β superfamily that function as potent extracellular antagonists of Nodal signaling [8] [19]. Research has elucidated two distinct mechanistic modes by which Lefty proteins inhibit Nodal activity, providing efficient and stringent regulation [19]:

- Direct Ligand Binding: Lefty can directly interact with the Nodal ligand in the extracellular space, physically preventing Nodal from accessing and binding to its receptor complex [19].

- Co-receptor Interference: Lefty can bind directly to the EGF-CFC co-receptor (Oep/Cripto), inhibiting the ability of this essential cofactor to participate in the formation of an active Nodal receptor complex [19].

Table 1: Modes of Lefty Inhibition of Nodal Signaling

| Mechanism | Molecular Interaction | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Ligand Blockade | Lefty binds to Nodal ligand | Prevents Nodal from interacting with its receptors |

| Co-receptor Interference | Lefty binds to EGF-CFC (Oep) | Disrupts formation of the active receptor complex |

Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core components and interactions of the Nodal/Lefty feedback loop:

Biophysical Properties Governing Signal Propagation

The different signaling ranges of Nodal and Lefty are not merely a function of production sites but are critically determined by their distinct biophysical properties and interactions with the extracellular environment. Single-molecule tracking studies in live zebrafish embryos have provided direct support for the hindered diffusion model, revealing how tissue geometry and binding interactions shape morphogen gradients [20].

Hindered Diffusion of Nodal and Lefty

In vivo measurements show that while Nodal and Lefty molecules have similar free diffusion coefficients in open extracellular "cavities," their mobility is significantly reduced in regions of close cell-cell contact ("interfaces") [20]. However, Nodal ligands exhibit a much higher "bound fraction" and longer binding times (tens of seconds) on cell surfaces compared to Lefty proteins [20]. This is attributed to Nodal's high-affinity binding to its receptors and co-receptors. This transient trapping on cell surfaces hinders Nodal movement, restricting it to short-range action. In contrast, the more mobile Lefty proteins, which lack this strong receptor binding, can diffuse over longer distances to exert their inhibitory influence [20].

Quantitative Diffusion Data

Table 2: Biophysical Properties of Nodal and Lefty Proteins from Single-Molecule Tracking

| Protein | Relative Local Mobility (in cavities) | Bound Fraction on Cell Surfaces | Typical Binding Time | Resulting Signaling Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclops (Nodal) | Low | High | Tens of seconds | Ultra-short range (few micrometers) |

| Squint (Nodal) | Intermediate | Intermediate | Tens of seconds | Short-to-mid range |

| Lefty1 | High | Low | Shorter | Long range |

| Lefty2 | Very High | Very Low | Shortest | Ultra-long range (near uniform) |

Experimental Evidence from Zebrafish Models

Phenotypic Consequences of Disrupted Feedback

Genetic loss-of-function experiments in zebrafish have been instrumental in deciphering the role of Lefty-mediated feedback. While lefty1 or lefty2 single mutants are viable with mild or no patterning defects, lefty1-/-;lefty2-/- double mutants are embryonic lethal [16]. These double mutants exhibit a dramatic expansion of Nodal signaling domains and a consequent excess of mesendoderm specification, leading to severe morphological defects including the loss of eyes, heart, and tail [16]. This phenotype demonstrates that without Lefty inhibition, Nodal signaling becomes hyperactive and spatially uncontrolled, disrupting normal embryonic patterning.

Key Experimental Protocol: Rescuing Patterning without Feedback

A pivotal experiment by Rogers et al. (2017) tested whether the feedback connection itself, rather than just the presence of inhibitor, is essential for development [16].

- Objective: To determine if Nodal patterning can function without inhibitory feedback by decoupling Lefty production from Nodal signaling.

- Experimental Subjects: lefty1-/-;lefty2-/- double mutant zebrafish embryos.

- Methodology - Two Rescue Conditions:

- Ectopic Lefty Expression: lefty mRNA was expressed ectopically in locations far from its normal expression domain in the mutant embryos.

- Uniform Pharmacological Inhibition: Mutant embryos were bathed in a solution of a Nodal inhibitor drug (e.g., SB505124), providing spatially and temporally uniform inhibition.

- Key Findings: Both rescue methods successfully restored normal mesendoderm patterning and viability to the lefty mutants [16]. This demonstrates that the precise, feedback-coupled expression of Lefty is not absolutely required for successful development. The system can function with uniform, non-feedback inhibition.

- Critical Insight on Robustness: While viable, the pharmacologically-rescued embryos were "fragile." They were less tolerant to mild perturbations in Nodal signaling levels compared to wild-type embryos, which can dynamically adjust Lefty expression to compensate for such fluctuations [16]. This indicates that the primary function of the Nodal-Lefty feedback loop is to ensure robustness and stability of the patterning process against genetic and environmental variations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Nodal/Lefty Signaling in Zebrafish

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Key Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| lefty1/2 Mutant Zebrafish | Genetic null alleles (e.g., lefty1a145, lefty2a146) generated via TALENs or CRISPR. | Modeling loss of feedback inhibition; studying phenotypes of expanded Nodal signaling [16]. |

| Nodal Inhibitor Drugs (e.g., SB505124) | Small molecule inhibitors that block Activin/Nodal type I receptors. | Temporally controlled inhibition of pathway; rescuing lefty mutants without feedback [16]. |

| HaloTag-Labeled Morphogens | Nodal and Lefty proteins fused to the HaloTag for covalent, bright dye labeling. | Single-molecule tracking of diffusion and binding in live embryos [20]. |

| memGFP mRNA | mRNA encoding membrane-targeted GFP. | Visualizing cell outlines and defining extracellular spaces for single-molecule analysis [20]. |

| Anti-pSmad2 Antibodies | Antibodies specific to the phosphorylated (active) form of Smad2. | Immunohistochemical readout of active Nodal signaling domains in fixed embryos [16]. |

The Nodal/Lefty feedback loop is a cornerstone of zebrafish mesendodermal patterning. The experimental evidence confirms that the primary role of this intricate circuit is not to initiate patterning per se, but to buffer the system against perturbations, thereby ensuring developmental robustness [16]. The ability to pattern successfully with uniform inhibition, albeit with reduced tolerance to fluctuation, underscores that the spatial coupling of activator and inhibitor through feedback is a key evolutionary adaptation for reliability. Furthermore, disruptions in this finely balanced system have direct clinical relevance, as aberrant Nodal signaling is linked to congenital heart defects and laterality disorders like heterotaxy in humans [18]. A deep understanding of these feedback mechanisms therefore not only illuminates fundamental principles of embryonic patterning but also provides a foundation for exploring therapeutic interventions for birth defects.

The transformation of a fertilized egg into a complex organism requires the precise spatial and temporal coordination of cell fate decisions. A cornerstone of this process in vertebrate embryos is the formation of the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—which give rise to all adult tissues and organs. In zebrafish, as in other vertebrates, the TGF-β signaling molecule Nodal serves as the primary inducer of mesendodermal fates, orchestrating a sophisticated gene regulatory network that patterns the embryonic axes. The mesendoderm represents a common progenitor population that subsequently segregates into definitive mesodermal and endodermal lineages, with Nodal signaling levels acting as a morphogen to determine specific cell fates. Cells exposed to high Nodal concentrations adopt endodermal fates, intermediate levels direct mesodermal differentiation, while low or absent signaling permits ectodermal specification [21].

This whitepaper examines the molecular machinery through which Nodal signaling translates concentration gradients into discrete transcriptional programs and cellular behaviors. We explore the downstream transcription factors that interpret this signaling, the cis-regulatory elements that integrate these signals, and the terminal differentiation genes that ultimately execute germ layer-specific functions. Recent technological advances, including optogenetic perturbation and large-scale transcription factor interaction mapping, have provided unprecedented insight into the logic of this developmental system. Understanding these mechanisms not only illuminates fundamental biological principles but also informs efforts in regenerative medicine, where controlled differentiation of stem cells into specific lineages remains a critical challenge.

The Core Nodal Signaling Pathway and its Regulation

The Nodal signaling pathway comprises a conserved set of components that transmit extracellular signals to the nucleus, culminating in changes in gene expression. Nodal ligands – primarily Cyclops and Squint in zebrafish – function as morphogens that form concentration gradients emanating from the embryonic margin [21]. These ligands signal through a cell surface receptor complex consisting of type I and type II activin receptors along with the EGF-CFC co-receptor One-eyed pinhead (Oep). Genetic studies have demonstrated that Oep is not merely a permissive co-factor but actively shapes the Nodal signaling gradient by regulating ligand spread and cellular sensitivity [21].

Upon receptor activation, intracellular Smad2/3 transcription factors become phosphorylated, form complexes with Smad4, and translocate to the nucleus where they participate in transcriptional regulation. The signaling range and intensity are finely tuned by feedback mechanisms, including positive feedback on Nodal ligand production and negative feedback through induction of Lefty antagonists, which form an activator-inhibitor pair with Nodal ligands [14] [21]. This regulatory architecture enables the system to generate robust patterning outcomes despite potential environmental fluctuations.

Table 1: Core Components of the Nodal Signaling Pathway in Zebrafish

| Component Type | Key Elements | Function in Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| Ligands | Cyclops, Squint | Diffusible morphogens forming concentration gradients; often heterodimers with Vg1 |

| Receptors/Co-receptors | Type I/II Activin Receptors, Oep | Cell surface complex that binds ligands and initiates signaling |

| Intracellular Transducers | Smad2/3, Smad4 | Phosphorylated and form complexes that translocate to nucleus |

| Transcription Factors | FoxH1, Mix-type proteins | Cooperate with Smads to activate target genes |

| Antagonists | Lefty1, Lefty2 | Diffusible inhibitors that restrict signaling range |

Figure 1: Core Nodal Signaling Pathway with Feedback Loops. Nodal ligand binding activates receptor complexes, leading to Smad phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Target gene activation includes positive feedback on Nodal production and negative feedback through Lefty antagonists.

From Signal to Pattern: Gradient Formation and Interpretation

The establishment of a Nodal signaling gradient is a dynamic process initiated by ligand secretion from the yolk syncytial layer (YSL) beneath the embryonic margin. Research has revealed that diffusive transport of Nodal ligands is sufficient to generate this gradient, contrary to models proposing obligatory feedback-driven relay mechanisms [21]. The shape and range of this gradient are critically determined by the EGF-CFC co-receptor Oep, which regulates ligand capture by target cells. In oep mutants, Nodal activity becomes nearly uniform throughout the embryo, demonstrating Oep's essential role in restricting ligand spread [21].

Cells interpret their position within the Nodal gradient through concentration-dependent activation of target genes. The signaling duration and intensity are translated into distinct transcriptional outputs through the combinatorial action of Smad complexes with various transcription factors. This interpretation mechanism enables cells to adopt specific fates according to their positional coordinates: high signaling levels activate endodermal genes like sox32 and sox17, intermediate levels induce mesodermal regulators such as ntl and gsc, while low or absent signaling permits ectodermal default programs [21].

Recent work has revealed that metabolic cues intersect with Nodal signaling to influence germ layer patterning. Glycolytic activity has been shown to modulate Nodal and Wnt signaling pathways, thereby influencing the proportional allocation of cells to different germ layers [22]. This connection between metabolism and patterning adds an additional layer of regulation that may link developmental programs to nutritional status.

Downstream Transcription Factors and Their Target Genes

The transcriptional response to Nodal signaling is mediated by a hierarchy of transcription factors that directly interpret Smad input and activate cell-type-specific genetic programs. Large-scale interaction mapping using CAP-SELEX has revealed an extensive network of transcription factor (TF) interactions that dramatically expand the gene regulatory code [23]. This methodology, which systematically tests TF-TF-DNA interactions, identified 2,198 interacting TF pairs among 58,000 tested combinations, with 1,329 showing preferred spacing/orientation and 1,131 forming novel composite motifs distinct from individual TF specificities [23].

Key Nodal-responsive transcription factors include FoxH1, which forms complexes with Smad2/3, and members of the Mix-type homeodomain family (e.g., Bon, Mixer, Mezzo). These factors activate cascades of gene expression that progressively specify mesodermal and endodermal sublineages. The discovery that TF-TF interactions frequently cross family boundaries and create novel DNA-binding specificities helps resolve the "hox specificity paradox," wherein TFs with similar binding specificities in vitro achieve distinct functional outcomes in vivo [23].

Table 2: Key Transcription Factor Interactions in Mesendodermal Patterning

| Transcription Factor Pair | Interaction Type | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| FOXI1–ELF2 | Composite motif formation | Creates novel DNA binding specificity distinct from individual factors |

| HOXB13–MEIS1 | Spacing/orientation preference | Cooperative binding with specific distance constraints |

| BACH2–LMX1A | Long-range interaction (8-9bp gap) | Unusual example of cooperation over longer distances |

| GLI2–RFX3 | Cross-family interaction | Links Hedgehog signaling to cilia-related gene regulation |

| POU5F1 (OCT4)–SOX2 | Well-characterized pair | Maintains pluripotency; paradigm for TF cooperation |

The functional significance of these interactions is evident in their enrichment at cell-type-specific regulatory elements, where they integrate positional information to drive appropriate gene expression programs. For instance, TFs that define embryonic axes frequently interact with different partners and bind distinct composite motifs, explaining how similar DNA-binding domains can achieve diverse developmental outcomes [23].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Optogenetic Perturbation of Nodal Signaling

Recent advances in optogenetics have enabled unprecedented spatial and temporal control over Nodal signaling, permitting direct testing of patterning models. An improved optoNodal2 system was developed by fusing Nodal receptors to the light-sensitive heterodimerizing pair Cry2/CIB1N, while sequestering the type II receptor to the cytosol [13]. This system eliminates dark activity and improves response kinetics without sacrificing dynamic range. Researchers adapted an ultra-widefield microscopy platform for parallel light patterning in up to 36 embryos simultaneously, demonstrating precise spatial control over Nodal signaling activity and downstream gene expression [13].

The experimental workflow involves several key steps:

- Embryo preparation: Zebrafish embryos expressing optoNodal2 components are collected and mounted for imaging and illumination.

- Light patterning: Custom illumination patterns are applied to activate Nodal signaling in defined spatial domains.

- Response monitoring: Signaling activity is tracked using live reporters of pathway activity (e.g., Smad localization) and target gene expression.

- Phenotypic analysis: Morphogenetic outcomes such as endodermal precursor internalization are quantified.

This approach has demonstrated that patterned Nodal activation can drive precise internalization of endodermal precursors and rescue developmental defects in Nodal signaling mutants, establishing a toolkit for systematic exploration of Nodal signaling patterns [13].

CAP-SELEX for Mapping Transcription Factor Interactions

The CAP-SELEX (consecutive-affinity-purification systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) method provides a high-throughput approach for identifying cooperative binding between transcription factors [23]. The adapted 384-well microplate format enables screening of thousands of TF-TF combinations through these key steps:

- TF expression and pairing: Human transcription factors are expressed in E. coli and combined into pairwise combinations (58,754 pairs in the recent study).

- DNA library incubation: TF pairs are incubated with a random oligonucleotide library.

- Consecutive affinity purification: Complexes containing both TFs and their bound DNA sequences are purified through sequential affinity tags.

- Sequencing and analysis: Bound DNA ligands are sequenced and analyzed using specialized algorithms to detect spacing/orientation preferences and novel composite motifs.

Two novel algorithms were developed for data analysis: a mutual information-based approach that identifies TF pairs with preferential binding to specific spacings/orientations, and a k-mer enrichment method that detects composite motifs differing from individual TF specificities [23].

Single-Cell Multiomics for Regulatory Network Inference

Single-cell RNA sequencing combined with single-cell ATAC sequencing enables the reconstruction of enhancer-driven gene regulatory networks with high resolution [24]. This approach involves:

- Cell isolation and processing: Single-cell suspensions are prepared from developing embryos or patterned stem cell models.

- Parallel library preparation: Both transcriptome and chromatin accessibility libraries are generated from the same cells.

- Data integration: Transcriptional and epigenomic profiles are combined to infer regulatory relationships.

- Regulon assembly: Transcription factors and their potential target genes are connected based on correlated activity patterns across cells.

Application of this method to T cell differentiation revealed how transcription factors like BATF and KLF2 govern cell fate decisions in the tumor microenvironment [24], illustrating approaches applicable to mesendodermal patterning studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Nodal Signaling and Germ Layer Specification

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| OptoNodal2 System | Optogenetic reagent | Light-controllable Nodal signaling; Cry2/CIB1N heterodimerizing pair; no dark activity; improved kinetics [13] |

| CAP-SELEX Platform | TF interaction mapping | 384-well format; screens >58,000 TF pairs; identifies spacing preferences and composite motifs [23] |

| Ultra-widefield Microscopy | Imaging platform | Parallel light patterning in 36 embryos; precise spatial control of signaling [13] |

| Tg(myl7:EGFP-CAAX) | Transgenic zebrafish line | Membrane-targeted GFP in myocardial cells; enables live imaging of heart morphogenesis [25] |

| scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq | Multiomic profiling | Paired single-cell transcriptome and epigenome; reveals enhancer-driven regulons [24] |

Morphogenetic Outcomes: From Gene Expression to Tissue Architecture

The ultimate readout of germ layer specification is the transformation of transcriptional programs into complex three-dimensional tissues. Nodal signaling not only patterns gene expression but also directs morphogenetic behaviors that shape embryonic structures. In zebrafish heart development, Nodal signaling through the ligand Southpaw regulates asymmetric cellular behaviors that drive clockwise rotation of the heart tube [25].

High-resolution live imaging has revealed that myocardial cells undergo oriented cell rearrangement and cell shape changes that collectively drive convergent extension of the cardiac disc [25]. Interestingly, left-sided cells exhibit more active rearrangement and shape changes compared to right-sided cells, resulting in asymmetric deformation that rotates the heart tube. This left-right asymmetry is abolished when Nodal signaling is disrupted, demonstrating that Nodal directly modulates the cellular behaviors underlying organogenesis [25].

Figure 2: Nodal Regulation of Heart Tube Morphogenesis. Asymmetric Nodal signaling drives left-right differences in cellular behaviors, leading to tissue-scale asymmetric deformation and clockwise heart tube rotation.

The morphogenetic process can be divided into two temporally distinct phases: an early phase dominated by oriented cell rearrangement through intercalation, and a later phase driven primarily by cell shape changes [25]. This sophisticated coordination of cellular behaviors ensures the robust establishment of organ asymmetry essential for proper physiological function.

The journey from Nodal signaling activation to germ layer specification represents a paradigm of embryonic patterning, integrating dynamic signaling gradients, sophisticated transcriptional networks, and physical morphogenetic processes. Recent technological advances—particularly in optogenetics [13], large-scale TF interaction mapping [23], and single-cell multiomics [24]—have provided unprecedented resolution into these processes.

Key emerging principles include the central role of TF-TF composite motifs in expanding the regulatory lexicon [23], the importance of co-receptor expression in shaping morphogen gradients [21], and the direct regulation of cellular morphogenetic behaviors by patterning signals [25]. The integration of metabolic cues with signaling pathways adds another layer of regulation that connects developmental programs to physiological conditions [22].

Future research directions will likely focus on achieving quantitative, predictive models of pattern formation that incorporate the full complexity of TF interactions, feedback regulation, and cellular behaviors. The application of synthetic biology approaches to reconstruct patterning circuits in stem cell models will further test our understanding of these principles. As we deepen our knowledge of how transcription factors guide cells from pluripotency to differentiated states, we advance both fundamental biology and the prospects for controlled tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications.

Within the broader study of zebrafish mesendodermal patterning research, understanding the cellular behaviors that translate molecular signals into physical form is paramount. The Nodal signaling pathway, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, serves as a master regulator in early vertebrate development. Its function extends beyond simple fate specification to directly orchestrating the complex morphogenetic movements that shape the embryo. This technical guide focuses on two fundamental cellular processes—convergent extension (CE) and other key tissue morphogenesis behaviors—driven by Nodal signaling. We examine how Nodal coordinates these processes through precise control of cell rearrangement, cell shape change, and directed migration, drawing upon recent optogenetic, live-imaging, and explant studies to provide a mechanistic framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Nodal Signaling Pathway: Mechanism and Regulation

The core Nodal pathway is an evolutionarily conserved system for controlling cell fate and behavior during embryonic development [8]. Activation begins when a Nodal ligand binds to a complex comprising Activin type I (Acvr1b) and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors at the cell surface. This interaction is dependent on EGF-CFC co-receptors (e.g., One-eyed pinhead/Oep in zebrafish, Cripto in mammals), which are essential for productive signal transduction [8]. Receptor activation leads to the phosphorylation of intracellular Smad2/3 proteins, which then form a complex with Smad4. This Smad complex translocates into the nucleus, where it associates with transcription factors such as FoxH1 to activate the expression of target genes, including Nodal itself (forming a positive feedback loop), Lefty (a secreted antagonist), and Sox32 (a key endodermal determinant) [8] [26].

The pathway is tightly regulated at multiple levels to ensure precise spatiotemporal signaling dynamics. Extracellular antagonists like Lefty and DAN family proteins (e.g., Cerberus) inhibit Nodal signaling by preventing receptor binding [8]. Intracellular negative regulators include Ectodermin, which promotes Smad4 mono-ubiquitination and nuclear export, and PPM1A, a phosphatase that dephosphorylates and inactivates Smad2/3 [8]. Additionally, the microRNA-430/427/302 family post-transcriptionally represses components like Nodal and Lefty, adding another layer of control to fine-tune signaling output [8]. The following diagram illustrates the core pathway and its key regulators.

Diagram of the core Nodal signaling pathway and its key regulators. The pathway is initiated by Nodal binding to its receptors and co-receptor, leading to Smad-dependent transcription of target genes. Multiple negative feedback mechanisms, including extracellular antagonists and intracellular inhibitors, precisely regulate signaling output.

Quantitative Data on Nodal-Driven Cellular Behaviors

Recent research has quantified the profound impact of Nodal signaling on specific cellular behaviors during gastrulation and organogenesis. The data reveal how Nodal governs tissue-level morphogenesis by regulating the magnitude and asymmetry of cellular processes.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Nodal-Dependent Cellular Behaviors during Zebrafish Development

| Cellular Behavior | Tissue Context | Quantitative Measurement | Effect of Nodal Loss | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Rearrangement (Intercalation) | Left Heart Primordium | ~50% reduction in circumferential length in 9 hours (early phase, driver) | Abolished left-right asymmetry in cell behavior | [25] |

| Cell Shape Change (Shortening) | Left Heart Primordium | ~80% extension in perpendicular axis; progressive cell shortening (later phase, driver) | Abolished left-right asymmetry in cell behavior | [25] |

| Tissue Convergence | Left vs. Right Heart Primordia | More rapid convergence of the left primordium | Asymmetric convergence abolished; heart tube rotation fails | [25] |

| Unidirectional Ingression | Ectopic Endodermal Cells | Radial, highly polarized migration to inner layer; not random walk | Ingression requires Nodal signaling and Sox32 | [26] |

| Patterned Internalization | Endodermal Precursors | Precise spatial control driven by optogenetic Nodal patterns | Mutant defects rescued by synthetic Nodal patterns | [13] |

The BMP/Nodal Signaling Ratio as a Morphogenetic Regulator

Beyond absolute levels, the relative concentration of Nodal to other morphogens provides critical patterning information. Research using zebrafish explants has identified a critical developmental window during which the BMP/Nodal ratio dictates the type of convergent extension movements [27]. Precise temporal manipulation of these pathways revealed that:

- A high BMP/Nodal ratio specifically induces and enhances neuroectoderm-driven convergent extension.

- A low BMP/Nodal ratio specifically induces and enhances mesoderm-driven convergent extension. These findings demonstrate that the temporal dynamics of morphogen signaling ratios activate distinct morphogenetic programs within individual tissues [27].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Nodal-Driven Behaviors

High-Resolution Live Imaging of Heart Tube Morphogenesis

This protocol enables the visualization and quantification of cellular behaviors during heart tube formation in zebrafish.

- Transgenic Line: Generate or use the Tg(myl7:EGFP-CAAX) zebrafish line. The myl7 promoter drives myocardial-specific expression of membrane-targeted EGFP, labeling cell boundaries [25].

- Sample Preparation: Mount live zebrafish embryos in a suitable imaging chamber (e.g., glass-bottom dish) using low-melting-point agarose to immobilize them for time-lapse imaging.

- Image Acquisition: Perform time-lapse fluorescence confocal microscopy. Recommended parameters include a imaging window spanning the disc-to-tube transition (e.g., 20-30 hours post-fertilion), with z-stacks acquired every 5-10 minutes over 9-10 hours to capture cellular dynamics [25].

- Data Analysis:

- Cell Tracking: Use image analysis software (e.g., TrackMate in Fiji/ImageJ) to track the centroid of individual myocardial cells over time.

- Tissue Dimension Analysis: Manually or automatically measure the circumferential and perpendicular lengths of the cardiac disc/tube over time.

- Cell Behavior Quantification:

- For cell rearrangement, measure the overlap between neighboring cells within circumferentially arrayed rows.

- For cell shape change, measure the length of the long and short axes of individual cells over time.

Optogenetic Control of Nodal Signaling Patterns

This pipeline allows for the spatial and temporal manipulation of Nodal signaling in live embryos to study its role in patterning.

- Optogenetic Reagents: Use the improved optoNodal2 system. This involves fusing Nodal receptors to the light-sensitive heterodimerizing pair Cry2/CIB1N, with the type II receptor sequestered to the cytosol. This system eliminates dark activity and improves response kinetics [13].

- Experimental Setup:

- Embryo Preparation: Inject zebrafish embryos with mRNA encoding the optoNodal2 constructs at the one-cell stage.

- Illumination Platform: Use an ultra-widefield microscopy platform adapted for parallel light patterning. This allows for simultaneous manipulation of up to 36 embryos [13].

- Pattern Design: Project custom illumination patterns (e.g., spots, gradients) onto the embryos at specific developmental stages to activate Nodal signaling in defined spatial domains.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Assess downstream gene expression via in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry for markers like sox32 or gsc.

- Quantify cell internalization events by tracking endodermal precursors.

- Test rescue capabilities by applying synthetic Nodal patterns in Nodal signaling mutants [13].

Ectopic Endodermal Cell Transplantation Assay

This method disentangles the roles of Nodal in cell fate specification versus cell migration.

- Generation of Donor Cells:

- Inject donor embryos with mRNA encoding a constitutively active Nodal receptor (acvr1ba*) or the transcription factor Sox32 to cell-autonomously induce endodermal fate [26].

- Confirm endodermal specification via qPCR for markers like sox17 and sox32.

- Transplantation:

- At the blastula stage, manually transplant approximately 10-20 donor cells into the animal pole of a wild-type host embryo, far from the endogenous endoderm at the margin [26].

- Live Imaging and Analysis:

- Use time-lapse microscopy to track the migration paths of the transplanted cells for several hours.

- Analyze the directionality and trajectory of cell movement. Ectopic endodermal cells typically undergo radial, unidirectional ingression into the inner layer, distinct from the marginal involution of endogenous endoderm [26].

- To test necessity, treat host embryos with small molecule Nodal inhibitors (e.g., SB505124) or perform transplants into Nodal pathway mutant hosts.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps and applications of these core methodologies.

Experimental workflow for investigating Nodal-driven cellular behaviors. Three core methodologies—live imaging, optogenetics, and cell transplantation—enable quantitative analysis of cell behaviors, causal testing of Nodal patterning, and dissection of fate specification from migration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

A range of specialized reagents and model systems are essential for probing the functions of Nodal signaling.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Nodal-Driven Morphogenesis

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Key Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| optoNodal2 System | Optogenetic | Light-controlled activation of Nodal receptors with high spatiotemporal resolution and low dark activity. | Creating synthetic Nodal signaling patterns to study mesendodermal patterning [13]. |

| Tg(myl7:EGFP-CAAX) | Transgenic Line | Labels myocardial cell membranes for high-resolution live imaging. | Visualizing and quantifying cell rearrangement and shape change during heart tube formation [25]. |

| acvr1ba* | Constitutively Active Receptor | Cell-autonomously induces endodermal specification independent of endogenous ligand. | Generating ectopic endodermal cells for transplantation assays to study migration [26]. |

| Zebrafish Explants | Ex Vivo Model | Uncoupled tissue morphogenesis for controlled manipulation of signaling pathways. | Defining the role of BMP/Nodal ratio in driving tissue-specific CE [27]. |

| Southpaw (spaw) Mutant | Genetic Model | Lacks asymmetric Nodal expression in the LPM, disrupting left-right patterning. | Studying the role of asymmetric Nodal in heart tube rotation and organ laterality [25]. |

Nodal signaling is a central conductor of morphogenesis, directly governing the cellular behaviors of convergent extension and tissue patterning that shape the zebrafish embryo. Through the experimental approaches detailed here—quantitative live-imaging, optogenetic patterning, and precise cellular assays—researchers can continue to decode the logic by which this pathway translates molecular information into physical structure. The tools and data presented provide a foundation for ongoing investigation, with significant implications for understanding congenital disorders and informing regenerative medicine strategies aimed at tissue engineering and repair.

Research Tools and Techniques for Studying Nodal Signaling

The formation of the mesoderm and endoderm (mesendoderm) in vertebrate embryos is orchestrated by the evolutionarily conserved Nodal signaling pathway. In zebrafish, this process is directed by Nodal-related signals Squint (Sqt) and Cyclops (Cyc), which establish a signaling gradient that patterns the embryonic tissues [4]. Investigating this crucial pathway requires precise genetic manipulation tools to dissect gene function. Two complementary approaches—CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout and morpholino oligonucleotide knockdown—have become fundamental techniques in developmental biology research. When applied to the study of Nodal signaling in zebrafish, these methods have revealed intricate aspects of receptor-ligand interactions, feedback mechanisms, and spatial patterning during germ layer formation [4] [28]. This technical guide examines the principles, applications, and methodologies of these genetic manipulation approaches within the context of zebrafish mesendodermal patterning research, providing researchers with practical frameworks for experimental implementation.

Fundamental Principles of Nodal Signaling in Zebrafish

Core Signaling Mechanism

The Nodal signaling pathway operates through a conserved receptor complex that includes Type I and Type II single-transmembrane serine/threonine kinase receptors along with an essential EGF-CFC co-receptor (Tdgf1/Oep in zebrafish) [4]. The signaling cascade initiates when Nodal ligands bind to Type II receptors and the co-receptor, leading to recruitment and phosphorylation of Type I receptors. The activated Type I receptors then phosphorylate the receptor-regulated Smad proteins (Smad2/Smad3), which form complexes with Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate target gene expression [4]. This pathway architecture creates a robust signaling system that converts extracellular ligand concentrations into specific transcriptional responses, ultimately guiding cell fate decisions during mesendodermal patterning.

Key Pathway Components and Their Functions

Table 1: Core Components of the Zebrafish Nodal Signaling Pathway

| Component | Type | Key Representatives | Function in Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligands | Secreted signals | Squint (Sqt), Cyclops (Cyc) | Initiate signaling by binding receptor complexes; form concentration gradients |

| Type I Receptors | Transmembrane kinases | Acvr1b-a, Acvr1b-b | Major mediators of Nodal signaling; phosphorylate R-Smads [4] |

| Type II Receptors | Transmembrane kinases | Acvr2 homologs | Bind ligands; phosphorylate Type I receptors [4] |

| Co-receptor | GPI-anchored protein | Tdgf1 (Oep) | Essential for receptor complex formation and ligand recognition [4] |

| Intracellular Transducers | R-Smads | Smad2, Smad3 | Phosphorylated by receptors; form complexes with Smad4 and regulate transcription |

| Transcription Factors | DNA-binding proteins | Foxd3 | Nodal-dependent regulator of dorsal mesoderm formation [28] |

| Antagonists | Secreted inhibitors | Lefty1, Lefty2 | Feedback inhibitors that restrict Nodal signaling range [4] |

The Nodal signaling gradient is established through a delicate balance between ligand production, diffusion, and inhibition. Zebrafish embryos lacking Nodal signaling fail to form endoderm and most mesodermal tissues, resulting in characteristic cyclopia and embryonic lethality [4] [28]. Conversely, excess Nodal signaling also causes severe patterning defects, highlighting the critical importance of precise spatial and temporal regulation of this pathway [4].

Figure 1: Nodal Signaling Pathway in Zebrafish. The diagram illustrates the core Nodal signaling mechanism, including receptor activation, intracellular transduction, and key regulatory feedback loops involving Foxd3 and Lefty.

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Zebrafish

Principles and Applications

The CRISPR/Cas9 system functions as an adaptive immune defense in bacteria and archaea, but has been repurposed as a highly versatile gene-editing tool in eukaryotic cells and organisms [29]. This technology enables precise introduction of targeted DNA double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci, which are subsequently repaired through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways. The NHEJ pathway often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, making CRISPR/Cas9 particularly valuable for generating loss-of-function mutants.

In zebrafish Nodal signaling research, CRISPR/Cas9 has been instrumental in characterizing receptor function. For example, studies targeting the Type I receptors Acvr1b-a and Acvr1b-b revealed that these genes function redundantly as major mediators of Nodal signaling during germ layer patterning [4]. Similarly, analysis of Type II receptor mutants demonstrated their partially Nodal-independent functions in embryo patterning [4]. The ability to generate stable mutant lines with CRISPR/Cas9 has provided crucial insights into the complex genetic redundancies and specific functions within the Nodal signaling network.

Experimental Protocol: Generating CRISPR Mutants

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Zebrafish

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | Purified S. pyogenes Cas9 nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target sites |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | 17-20 nt target sequence + scaffold | Directs Cas9 to specific genomic loci |

| Microinjection Apparatus | Micropipette puller, injector | Delivers CRISPR components to zebrafish embryos |

| Genotyping Primers | Flanking target site | Amplifies edited region for mutation detection |

| Mutation Detection Assay | T7E1, TIDE, or sequencing | Identifies and characterizes induced mutations |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Target Selection and gRNA Design: Identify target sequences within genes of interest (e.g., Nodal receptors) that conform to the 5'-NGG-3' PAM requirement. Optimal target sites are typically 17-20 nucleotides located in early exons encoding critical functional domains [30].

gRNA Synthesis:

- Design oligonucleotides containing the T7 promoter sequence followed by the target sequence:

5'-taatacgactcactataGNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNgttttagagctagaa-3' - Amplify using PCR and transcribe using T7 RNA polymerase.

- Purify the gRNA using standard RNA purification methods [30].

- Design oligonucleotides containing the T7 promoter sequence followed by the target sequence:

Cas9 mRNA Preparation:

- Linearize a Cas9 expression plasmid containing the zebrafish codon-optimized Cas9 sequence.

- Perform in vitro transcription using an mRNA synthesis kit.

- Purify the mRNA and quantify concentration [30].

Microinjection into Zebrafish Embryos:

- Prepare an injection mixture containing 150-300 ng/μL Cas9 mRNA and 30-50 ng/μL gRNA.

- Inject 1-2 nL into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Allow injected embryos to develop at 28.5°C [30].

Mutation Efficiency Analysis:

- At 24-48 hours post-fertilization, extract genomic DNA from pooled embryos (10-20 individuals).

- PCR-amplify the target region using flanking primers.

- Assess mutation efficiency using T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay or Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition (TIDE) analysis [30].

Founder Identification and Establishment of Stable Lines:

- Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood.

- Outcross potential founders to wild-type fish.

- Screen F1 progeny for germline transmission by genotyping.

- Establish heterozygous lines and intercross to generate homozygous mutants [4].

Figure 2: CRISPR/Cas9 Workflow in Zebrafish. The diagram outlines the key steps in generating and validating CRISPR/Cas9 mutants, from target selection to establishment of stable lines for functional analysis.

Validation and Phenotypic Analysis

Confirmation of successful gene editing requires comprehensive validation at both molecular and phenotypic levels. For Nodal signaling components, phenotypic analysis typically includes:

- Molecular Genotyping: Sequence the target locus to identify specific mutations and predict their functional consequences (e.g., frameshifts, premature stop codons) [30].

- In Situ Hybridization: Assess expression patterns of known Nodal target genes (e.g., cyclops, squint, foxd3) in mutant embryos [28].

- Morphological Assessment: Document developmental defects characteristic of Nodal signaling disruption, including cyclopia, mesendodermal patterning defects, and axial abnormalities [4] [28].

- Rescue Experiments: Inject wild-type mRNA into mutant embryos to confirm that observed phenotypes are specific to the targeted gene [28].

Morpholino-Mediated Gene Knockdown

Principles and Applications

Morpholino oligonucleotides are synthetic antisense molecules that suppress gene expression by either blocking translation initiation or interfering with pre-mRNA splicing [30]. Their modified chemistry confers resistance to nucleases and improves sequence specificity compared to traditional antisense approaches. In zebrafish Nodal signaling research, morpholinos have been particularly valuable for studying genes with maternal contributions, analyzing genetic redundancy, and performing rapid functional assessments.

Translation-blocking morpholinos bind to sequences near the translation start site, preventing ribosomal assembly and protein synthesis. Splice-blocking morpholinos target intron-exon boundaries and disrupt proper mRNA processing, often leading to exon skipping or intron retention [30]. Both approaches have been successfully employed to investigate Nodal signaling components, including the essential role of Foxd3 as a Nodal-dependent regulator of dorsal mesoderm formation [28].

Experimental Protocol: Morpholino Knockdown

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Morpholino Design:

- For translation blocking: Design 25-base morpholinos complementary to the 5' untranslated region (UTR) and/or the sequence surrounding the start codon.

- For splice blocking: Design morpholinos complementary to splice donor, acceptor, or branch point sites.

- BLAST the sequence against the zebrafish genome to ensure specificity [30].

Morpholino Preparation:

- Resuspend lyophilized morpholino in sterile water to create a 1-2 mM stock solution.

- Dilute to working concentration in 1X Danieau buffer (58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO₄, 0.6 mM Ca(NO₃)₂, 5.0 mM HEPES; pH 7.6) [28].

Microinjection into Zebrafish Embryos:

Efficacy Validation:

- For translation blockers: Inject mRNA encoding a GFP-tagged version of the target gene and assess fluorescence reduction.

- For splice blockers: Perform RT-PCR across the targeted splice region to confirm aberrant splicing [30].

Phenotypic Analysis:

- Assess embryos for developmental defects at relevant stages.

- For Nodal signaling studies, analyze expression of pathway markers (e.g., cyclops, gsc, foxa3) by in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry [28].

- Document phenotypes quantitatively and compare to appropriate controls.

Specificity Controls and Validation

A significant challenge in morpholino experiments is distinguishing specific from off-target effects. The following control strategies are essential:

- Dose-Response Analysis: Titrate morpholino concentration to establish the minimal dose required to elicit the phenotype [30].

- Multiple Independent Morpholinos: Use at least two non-overlapping morpholinos targeting the same gene [28].

- mRNA Rescue: Co-inject in vitro transcribed wild-type mRNA (lacking the morpholino binding site) to confirm phenotype rescue [28].

- Genetic Validation: Whenever possible, compare morpholino phenotypes with mutant phenotypes [30].

The Deletion of Morpholino Binding Sites (DeMOBS) approach provides a particularly robust validation method. This technique involves using CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce small deletions within the morpholino target site, creating MO-refractive alleles. When embryos heterozygous for these deletions are injected with the morpholino, approximately 50% should be rescued, confirming phenotype specificity [30].

Comparative Analysis and Integration of Approaches

Strategic Application in Nodal Signaling Research

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Genetic Manipulation Approaches in Zebrafish Nodal Research

| Parameter | CRISPR/Cas9 Mutants | Morpholino Knockdown |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Permanent genomic modification; gene disruption | Transient suppression of gene expression |

| Temporal Control | Constitutive; established at one-cell stage | Acute; timing can be controlled by injection stage |

| Duration of Effect | Permanent; heritable | Transient; typically 2-5 days |

| Maternal Effect Assessment | Requires maternal-zygotic mutants | Effective against both maternal and zygotic transcripts |

| Genetic Redundancy Analysis | Suitable for generating multiple mutants | Enables simultaneous targeting of multiple paralogs |

| Validation Requirements | Molecular genotyping; phenotypic characterization | Specificity controls; rescue experiments |

| Key Applications in Nodal Research | Receptor characterization (Acvr1b-a/b) [4]; stable line establishment | Foxd3 functional analysis [28]; rapid screening |

Integrated Approaches for Comprehensive Analysis

The most robust conclusions in Nodal signaling research often emerge from the strategic integration of multiple genetic manipulation approaches. For example:

Initial Screening with Morpholinos: Rapid assessment of gene function using morpholinos, followed by validation with CRISPR mutants [30].

Complementation Tests: Injecting morpholinos into heterozygous mutant backgrounds to confirm phenotype specificity through enhanced penetrance [30].

Temporal Manipulation: Using morpholinos for acute knockdowns to define critical windows for Nodal signaling activity, complemented by genetic mutants for phenotypic analysis.

Redundancy Analysis: Combining CRISPR targeting of multiple paralogous genes (e.g., Type I receptors Acvr1b-a and Acvr1b-b) with morpholino-mediated knockdown to overcome compensatory mechanisms [4].

This integrated approach was successfully employed to demonstrate that the Type I receptors Acvr1b-a and Acvr1b-b function redundantly as major mediators of Nodal signaling in zebrafish, while Type II receptors operate partially independently of Nodal in embryo patterning [4].

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Optogenetic Control of Nodal Signaling