Optimized IVF Protocol for Timed Embryo Donor Mice: Enhancing Precision in Reproductive Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to in vitro fertilization (IVF) protocols specifically tailored for generating timed embryo donor mice, a critical resource for biomedical and drug development research.

Optimized IVF Protocol for Timed Embryo Donor Mice: Enhancing Precision in Reproductive Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to in vitro fertilization (IVF) protocols specifically tailored for generating timed embryo donor mice, a critical resource for biomedical and drug development research. It covers the foundational principles of mouse reproductive biology and the importance of precise timing in superovulation. The content details a step-by-step methodological application, including reagent preparation, oocyte collection, and sperm handling. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies, such as strain-specific adjustments and novel sperm preparation techniques. Finally, it explores validation methods and compares efficiency across different mouse strains, offering researchers a robust framework to improve experimental reproducibility and success rates in generating embryo donors.

Fundamentals of Mouse Reproductive Biology and Timed Donor Principles

The Role of Mouse Models in Advancing Reproductive Biology and Drug Development

Mouse models serve as an indispensable cornerstone of biomedical research, providing critical insights into the complex mechanisms governing mammalian reproduction and enabling the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Their genetic similarity to humans, short reproductive cycles, and the availability of sophisticated genetic engineering tools make them particularly valuable for studying reproductive biology and advancing drug development. This article presents a detailed overview of current applications and methodologies, with a specific focus on in vitro fertilization (IVF) protocols for timed embryo donor mice, framed within the context of a broader thesis on reproductive technologies. We provide structured experimental data, detailed protocols, and visual workflows specifically designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of reproductive biology and translational medicine.

Key Advances in Reproductive Biology Using Mouse Models

Foundational Research and Therapeutic Development

Recent research utilizing mouse models has yielded significant advances across multiple domains of reproductive biology, from addressing infertility to developing novel contraceptive strategies and refining assisted reproductive technologies (ART). The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Mouse Model Studies in Reproductive Biology

| Research Area | Key Finding | Quantitative Result | Significance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infertility Treatment | mRNA therapy restores spermatogenesis in NOA mice | 22.2% live birth rate (26 pups/117 embryos) via ICSI | Offers non-integrating gene therapy approach for genetic infertility | [1] |

| Fertility Enhancement | Fertilin peptide improves embryo development and birth rates | Accelerated blastocyst expansion by 2h43; Significant improvement in live birth rate | Potential therapeutic for improving IVF outcomes | [2] |

| Contraceptive Research | Human PRSS55 rescues infertility in knockout mice | RES TM line showed fertility comparable to wild-type controls | Validates model for testing human PRSS55-targeted contraceptives | [3] |

| ART Safety | Mutation rates in IVF-conceived mice | ~30% more single-nucleotide variants vs. natural conception | Informs safety assessment of assisted reproductive technologies | [4] |

| Germ-Free Production | Optimized cesarean technique improves fetal survival | FRT-CS significantly improved survival while maintaining sterility | Enhances efficiency of germ-free mouse production for microbiome studies | [5] |

Humanized Models for Drug Development

The development of humanized mouse models has proven particularly transformative for preclinical drug development. For instance, Cyagen's C3 and C5 humanized mouse models, created via precise gene replacement technology, express the full human C3 or C5 genes while suppressing the endogenous mouse genes. These models have become foundational for testing highly specific biologics, such as siRNA-based therapeutics and bispecific antibodies, whose efficacy is dependent on human protein targets [6]. This approach directly addresses the translational bottleneck caused by species-specific interactions between therapeutic candidates and their targets, thereby providing more reliable predictive data for human clinical outcomes.

Detailed In Vitro Fertilization Protocol for Timed Embryo Donor Mice

This section provides a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for obtaining timed embryos from donor mice via IVF, incorporating best practices and optimizations from core facility procedures and recent research.

Pre-IVF Procedures and Animal Preparation

Donor Mouse Selection and Superovulation

- Donor Females: Utilize 30-50 female mice, 3-5 weeks old, from the line of interest. Younger females typically yield higher oocyte quantities and quality [7].

- Superovulation Hormone Regimen:

- Day 1 (Afternoon): Administer intraperitoneal (IP) injection of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMS/PMSG) at 5-7.5 IU per mouse to stimulate follicular growth.

- Day 3 (Afternoon): Administer IP injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) at 5-7.5 IU per mouse to induce final oocyte maturation [2] [7].

- Sperm Donors: Provide 1-2 proven breeder male mice (2-5 months old) for fresh sperm collection. Homozygous males are preferred if maintaining a specific genetic background [7].

- Euthanize one male sperm donor by cervical dislocation or CO₂ asphyxiation following approved IACUC protocols.

- Quickly dissect to isolate the cauda epididymides.

- Transfer epididymides to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing 500 µL of pre-warmed, equilibrated human tubal fluid (HTF) medium supplemented with 4 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA).

- Make several incisions in the epididymal tubules using fine scissors or a 25-gauge needle to allow sperm to swim out.

- Incubate the sperm suspension for 45-90 minutes at 37°C under 5% CO₂ to allow for capacitation. Assess sperm motility and concentration after incubation [7].

Oocyte Collection and Fertilization

Oocyte Harvesting

- Approximately 13-15 hours post-hCG injection, euthanize the superovulated donor females.

- Collect the oviducts and place them in a dish of pre-warmed HEPES-buffered medium (e.g., M2 or FHM).

- Under a stereomicroscope, locate the ampulla, a swollen section of the oviduct containing the cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs).

- Puncture the ampulla with a fine needle to release the COCs into the medium.

In Vitro Fertilization

- Transfer 100-200 µL of the capacitated sperm suspension (containing ~1-5 x 10⁶ sperm/mL) into a 100-200 µL drop of fertilization medium (e.g., HTF with BSA) under mineral oil.

- Wash the collected COCs briefly and transfer 20-30 oocytes into the fertilization drop containing sperm.

- Co-incubate gametes for 4-6 hours at 37°C under 5% CO₂ [7].

Post-Fertilization Procedures and Embryo Culture

Embryo Washing and Culture

- After co-incubation, wash the presumptive zygotes thoroughly through several drops of pre-equilibrated KSOM or other embryo culture medium to remove adherent sperm and cumulus cells.

- Transfer 20-25 zygotes into a 50-100 µL drop of fresh KSOM medium under mineral oil.

- Culture embryos at 37°C under 5% CO₂, assessing development daily. Under optimal conditions, embryos should progress to the 2-cell stage by 24 hours post-fertilization and to the blastocyst stage by days 3.5-4.5 [7].

Embryo Transfer or Cryopreservation

- For embryo transfer, surgically transfer 10-15 two-cell embryos (at E0.5) into the oviducts of a pseudo-pregnant 0.5 days post-coitum (dpc) recipient female, or transfer blastocysts (at E3.5) into the uterus of a 2.5 dpc recipient [7].

- For cryopreservation, cryopreserve 2-cell, morula, or blastocyst-stage embryos using controlled-rate freezing or vitrification protocols for long-term storage [7].

Table 2: IVF Project Timeline and Key Milestones (Adapted from MART Core Protocol)

| Timeline | Activity | Key Steps and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Time depends on colony size | Breeding and Mouse Preparation | Breed to obtain 5-10 male and 20-30 female donors (5-6 weeks old). |

| Day 1-3 | Hormone Priming of Donors | Inject PMS (Day 1) and hCG (Day 3). |

| Day 4 | Check Mating Plugs & Sperm Prep | Confirm superovulation; Collect and capacitate sperm. |

| Day 5 | Oocyte Collection & IVF | Harvest oocytes; Perform in vitro fertilization (4-6 hr co-incubation). |

| Day 6 | Embryo Check and Culture | Confirm 2-cell embryos; Continue culture to morula/blastocyst if needed. |

| Day 7 Onwards | Embryo Transfer or Cryopreservation | Transfer to pseudo-pregnant recipients or cryopreserve for future use. |

Experimental Data and Workflow Visualization

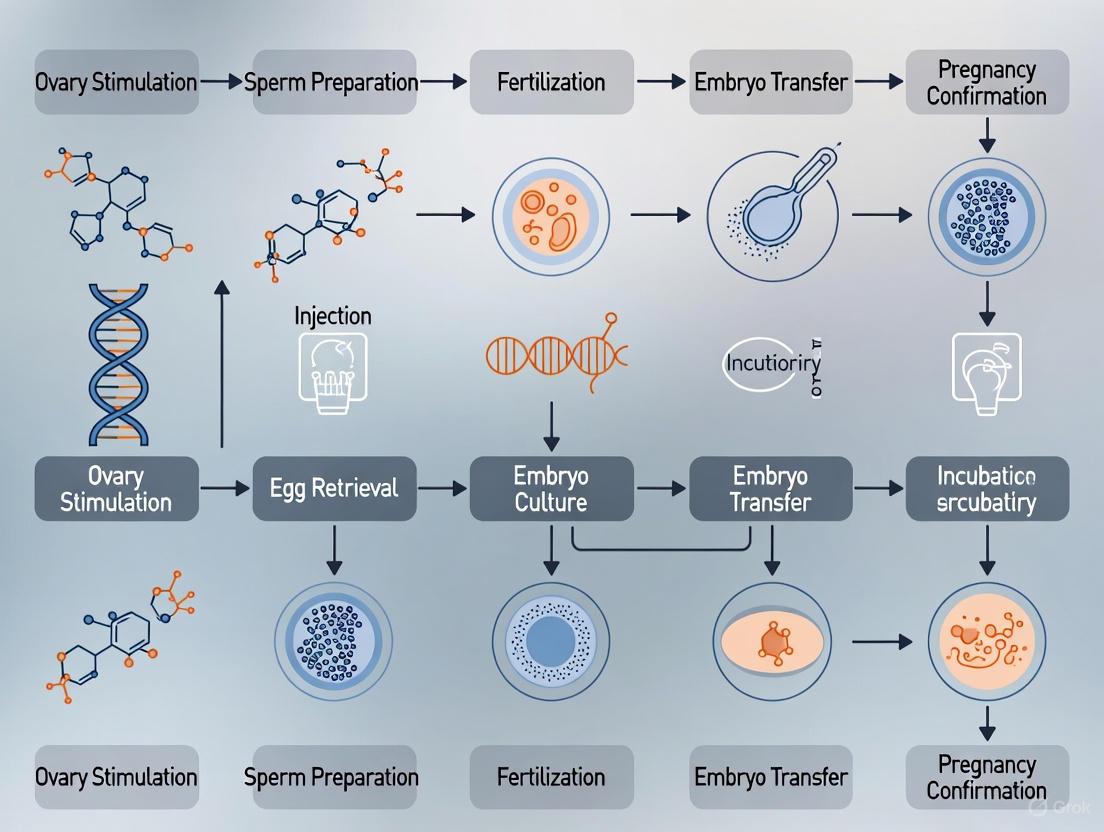

IVF and Rederivation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for generating pathogen-free mice via IVF rederivation, a critical process for importing or safeguarding valuable genetic lines.

Diagram 1: IVF Rederivation Workflow for Pathogen-Free Mice

mRNA Therapy for Male Infertility

The diagram below outlines the innovative mechanism of using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to deliver mRNA for treating non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) in a mouse model, a groundbreaking therapeutic approach.

Diagram 2: mRNA Therapy Mechanism for Male Infertility

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mouse Reproductive Biology and IVF

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin (PMS/PMSG) | Hormonal priming for superovulation in donor females. | Analogous to FSH; stimulates follicular development. [2] [7] |

| Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) | Triggers final oocyte maturation and ovulation. | Analogous to LH; administered after PMS. [2] [7] |

| HTF (Human Tubal Fluid) Medium | Standard medium for in vitro fertilization and sperm capacitation. | Often supplemented with BSA (4 mg/mL). [7] |

| KSOM Medium | Serum-free, optimized medium for post-fertilization embryo culture. | Supports development from zygote to blastocyst. [7] |

| M2/FHM Medium | HEPES-buffered holding media for oocyte collection and manipulations outside a CO₂ incubator. | Maintains physiological pH outside the incubator. [7] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery vehicle for mRNA-based therapies to restore gene function. | Used to deliver Pdha2 mRNA to testis in NOA model. [1] |

| Clidox-S | Chlorine dioxide disinfectant for sterilizing tissues and equipment in germ-free isolators. | Used at 1:3:1 dilution, activated for 15 min before use. [5] |

| Fertilin Peptide | Synthetic peptide that mimics sperm-binding molecule; accelerates embryo development. | Used at 100 μM concentration to improve blastocyst formation rates. [2] |

Mouse models continue to be pivotal in unraveling the complexities of mammalian reproductive biology and accelerating the development of novel therapeutics. The refined IVF protocols, quantitative data, and visual workflows presented in this article provide a robust resource for researchers engaged in both fundamental reproductive science and translational drug development. As the field progresses, the integration of advanced technologies—such as humanized models for target validation, mRNA-based therapies for genetic infertility, and optimized protocols for generating specialized animal models—will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of reproductive mechanisms and enhance our ability to address reproductive challenges in human health.

The estrous cycle represents a series of physiologically recurring changes induced by reproductive hormones in most female mammals, crucial for timed reproduction and fertilization success [8]. In laboratory mice, a profound understanding of this cycle is indispensable for reproductive research, particularly in the generation of timed embryo donors for in vitro fertilization (IVF) studies. The mouse is polyestrous, experiencing cycles every 4-5 days throughout the year without seasonal influence, making it a consistent model for research [9]. The cycle is divided into four distinct stages—proestrus, estrus, metestrus, and diestrus—each characterized by specific hormonal, ovarian, and vaginal cytological changes [9] [8]. Mastery of these stages allows researchers to precisely time experimental interventions, ensuring optimal oocyte yield and quality for procedures such as superovulation and IVF, which are foundational for preserving genetically engineered models and biomedical discovery [5] [10].

Table 1: Stages of the Murine Estrous Cycle

| Stage | Duration (Hours) | Key Hormonal Features | Vaginal Cytology | Behavioral/Sexual Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proestrus | ~12 | Follicles grow, estrogen rises | Nucleated epithelial cells | Not sexually receptive |

| Estrus | ~12 | Estrogen peak, pre-ovulatory LH surge | Cornified (squamous) epithelial cells | Sexually receptive ("in heat") |

| Metestrus | ~21 | Corpus luteum begins to form | Leukocytes appear with nucleated and cornified cells | Not receptive |

| Diestrus | ~57 | Progesterone from corpus luteum dominates | Predominantly leukocytes | Not receptive |

Hormonal Control of the Estrous Cycle

The estrous cycle is governed by an exquisitely sensitive feedback system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) Axis, which coordinates the timing of ovarian events with the preparation of the reproductive tract to maximize the chances of successful fertilization and pregnancy [9] [11].

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) Axis

The hypothalamus secretes Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile manner, which in turn stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete the gonadotropins Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH) [11]. These gonadotropins act directly on the ovaries. FSH is primarily responsible for the recruitment and development of a cohort of ovarian follicles, while LH stimulates theca cells to produce androgens, which are subsequently aromatized into estrogens by granulosa cells—a process known as the two-cell, two-gonadotropin hypothesis of estrogen synthesis [12]. The ovarian hormones, estradiol and progesterone, then complete the feedback loop by exerting both negative and positive feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary to regulate GnRH, FSH, and LH secretion [12] [9].

Figure 1: The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) Axis. This diagram illustrates the core hormonal feedback loops that regulate the estrous cycle. GnRH from the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary to release FSH and LH, which act on the ovary. Ovarian hormones (estradiol, progesterone) complete the loop via feedback. CL = Corpus Luteum.

Hormonal Dynamics During the Follicular and Luteal Phases

The cycle can be broadly divided into two phases: the follicular phase (encompassing proestrus and estrus) and the luteal phase (metestrus and diestrus) [12] [9].

During the follicular phase, the decline of progesterone from the previous cycle's corpus luteum allows FSH to rise, recruiting a group of follicles [12]. One follicle becomes "dominant" and secretes increasing amounts of estradiol. This rising estradiol exerts negative feedback on FSH (preventing other follicles from maturing) and, upon reaching a sustained threshold (>200 pg/mL for ~50 hours), triggers a positive feedback surge of LH [12]. This LH surge is the definitive signal that induces ovulation, which occurs approximately 10-12 hours later in mice [9].

Following ovulation, the luteal phase begins. The ruptured follicle transforms into the corpus luteum, a temporary endocrine structure that secretes large quantities of progesterone [12] [11]. Progesterone's primary role is to prepare the uterine lining for implantation. If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum undergoes luteolysis, progesterone levels fall, and the cycle begins anew with a rise in FSH [12] [8].

Table 2: Key Hormone Production Rates During the Mouse Estrous Cycle

| Sex Steroid | Early Follicular (µg/24h) | Preovulatory (µg/24h) | Mid-Luteal (µg/24h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 36 | 380 | 250 |

| Progesterone (mg/24h) | 1 | 4 | 25 |

| Testosterone | 144 | 171 | 126 |

The Principle of Superovulation

Superovulation is a controlled hormonal technique used to override the natural limits of the estrous cycle, inducing the maturation and ovulation of a significantly larger number of oocytes than occurs spontaneously [13] [14]. This is critical for maximizing embryo yield in IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies, especially when working with valuable or genetically modified donor strains [5].

The physiological basis for superovulation lies in mimicking and amplifying the natural hormonal sequence of the follicular phase. In a natural cycle, rising FSH recruits a cohort of follicles, but only one is selected to become dominant and ovulate, while the others undergo atresia [12]. Superovulation involves the exogenous administration of equine-derived Gonadotropins, which have high FSH-like activity, to stimulate the synchronous development of a larger cohort of follicles [14]. This is followed by an injection of human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG), which acts as a potent analog of LH, to trigger the final maturation and ovulation of all the recruited follicles simultaneously [13] [14]. The timing of this protocol is precisely coordinated with the donor's estrous cycle to achieve the highest quality and quantity of oocytes.

Detailed Superovulation and IVF Protocol for Timed Embryo Donor Mice

This protocol integrates established methodologies from leading reproductive laboratories to ensure high efficiency and reproducibility [13] [14] [10]. Adherence to precise timing is paramount.

Reagent and Material Preparation

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Essential Reagents for Superovulation and IVF

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Hormones for Superovulation | Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin (PMSG), Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) | PMSG (eCG) mimics FSH for multi-follicular growth; hCG mimics the LH surge to trigger ovulation. |

| Fertilization Media | Human Tubal Fluid (HTF), CARD MEDIUM, Modified RVF (mRVF) | Provides energy sources and ionic composition mimicking the oviductal environment to support sperm capacitation, fertilization, and early zygote formation. |

| Sperm Handling Media | FERTIUP | A pre-incubation medium designed to support sperm capacitation and maintain motility before introduction to oocytes. |

| Embryo Culture Media | KSOM-AA, M16 | Complex media supporting preimplantation embryo development from zygote to blastocyst stage. |

| General Supplies | Embryo-tested mineral oil, 35/60mm culture dishes, pulled glass pipettes, CO2 incubator | Oil overlays prevent evaporation; specific dishes and tools allow for precise handling of gametes and embryos. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Figure 2: Superovulation and IVF Workflow. A visual guide to the critical path and timing for generating timed embryo donors.

Day 1: Initiation of Follicular Growth

- Select 3- to 4-week-old female mice (immature donors have a higher superovulation response) [10].

- Administer an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 5 IU of PMSG between 2:00 PM and 6:00 PM [13]. This timing helps align ovulation with the natural circadian rhythm.

Day 3: Triggering Ovulation

- Precisely 48 hours after the PMSG injection, administer an IP injection of 5 IU of hCG [13] [14].

- Prepare all necessary fertilization media dishes (e.g., sperm dish with FERTIUP, fertilization dish with CARD MEDIUM or HTF+, washing dishes with mHTF) and equilibrate them in a CO2 incubator at least 30 minutes before use [13].

Day 4: In Vitro Fertilization (13-17 hours post-hCG)

- Oocyte Collection: Sacrifice donor females 13-17 hours after hCG injection [14] [15]. Rapidly dissect the oviducts and place them in the fertilization dish under oil. Using fine forceps, tear the swollen ampulla to release the cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs). Transfer the COCs to the equilibrated fertilization drop. Critical Note: The interval from euthanasia to oocyte collection must be minimized (optimally <3 minutes) to prevent zona pellucida hardening and maintain high fertilization rates [15].

- Sperm Preparation:

- For Fresh Sperm: Sacrifice a proven male, remove the cauda epididymides and vasa deferentia, and release sperm into a pre-equilibrated drop of FERTIUP. Incubate for 30-60 minutes for capacitation [13] [14].

- For Frozen/Thawed Sperm: Rapidly thaw a frozen straw or vial in a 37°C water bath. For straws, expel contents directly into a FERTIUP drop. For vials, the sperm suspension can be washed or transferred directly to FERTIUP. Incubate for 30 minutes [13] [14].

- Insemination: Using a wide-bore pipette tip to avoid damaging sperm, add a 3-10 µL aliquot of the motile sperm suspension to the fertilization drop containing the COCs [13] [14]. The final motile sperm concentration should be approximately 1-2.5 x 10^6/mL [14].

- Co-incubation and Washing: Place the fertilization dish back in the incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 4-6 hours. Subsequently, wash the oocytes through several drops of fresh medium (e.g., mHTF or KSOM-AA) to remove adherent sperm and cellular debris [14].

Day 5: Assessment and Embryo Culture

- The following morning (approximately 24 hours post-insemination), examine the oocytes under a microscope. Successfully fertilized oocytes will have cleaved to the 2-cell stage [14].

- Transfer the 2-cell embryos to a fresh culture dish with KSOM-AA medium for further development to the blastocyst stage, or surgically transfer them into 0.5 days post coitum (dpc) pseudopregnant recipient females to generate live offspring [13] [14] [5].

Critical Factors for Protocol Success

- Strain Background: The C57BL/6 strain, the most common genetic background for engineered models, is known for lower and more variable superovulation and IVF efficiency compared to outbred or hybrid strains [10]. The use of optimized media like CARD MEDIUM or HTF+ (HTF supplemented with extra Calcium and Glutathione) can significantly improve fertilization rates in these difficult strains [13] [10].

- Sperm Source and Quality: Frozen-thawed sperm often exhibits reduced motility and fertility compared to fresh sperm. Protocols for frozen sperm may require modifications, such as omitting the pre-incubation capacitation step or using cumulus-denuded oocytes to facilitate fertilization [14].

- Predictability and Efficiency: Integrating IVF into the production pipeline for germ-free mice via cesarean section allows for precise control over the donor's delivery date, greatly enhancing experimental reproducibility and efficiency compared to reliance on natural mating [5].

The generation of a "Timed Donor" in mouse embryology research refers to the precise synchronization of donor embryo developmental stage with the experimental requirements of the host system. This precision is paramount because embryonic development proceeds along a highly orchestrated timeline, and even minor discrepancies in developmental age can compromise experimental outcomes. The core principle hinges on isochronic transplantation, where the developmental stage of donor cells or embryos must be meticulously matched with that of the host to ensure functional integration and accurate research data [16]. The failure to achieve this synchrony, known as heterochronic injection, reliably results in the failure of chimera formation, underscoring that matching developmental age is a non-negotiable prerequisite for successful engraftment [16]. This document outlines the standardized protocols and application notes for establishing precisely timed embryo donor mice, a critical foundation for research in developmental biology, genetic engineering, and regenerative medicine.

Mouse Embryo Developmental Staging: A Reference Timeline

A precise understanding of the murine embryo developmental sequence is the first step in defining the timed donor. The following table summarizes the key morphological stages and their corresponding temporal landmarks post-fertilization.

Table 1: Standard Timeline of Preimplantation Mouse Embryo Development In Vivo

| Day Post-Coitum | Developmental Stage | Key Morphological Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 (E0.5) | Fertilization (Zygote) | Formation of male and female pronuclei [17] [18]. |

| 1.5 (E1.5) | 2-Cell Embryo | First cleavage division [17]. |

| 2.0 (E2.0) | 4-Cell Embryo | Second cleavage division [17]. |

| 2.5 (E2.5) | 8-Cell Embryo | Third cleavage division; onset of compaction [17]. |

| 3.5 (E3.5) | Morula | A compact ball of 16+ cells; cell boundaries become indistinct [18]. |

| 4.5 (E4.5) | Blastocyst | Formation of fluid-filled blastocoel cavity, inner cell mass (ICM), and trophectoderm (TE) [18] [19]. |

This timeline serves as the primary reference for coordinating donor embryo production with host recipient preparation. Deviations from this expected schedule, such as a delay in compaction or blastulation, can indicate reduced embryonic viability and disqualify an embryo from being used as a reliable timed donor.

Protocols for Generating Timed Donor Embryos

Protocol 1: Setting Up Timed Pregnancies

This protocol describes the procedure for mating mice to obtain embryos at a precisely known gestational age [20] [21].

Objective: To generate a cohort of female mice with a known mating time (Day 0.5) for the harvest of aged-matched embryos. Materials:

- Proven adult stud male mice (e.g., C57BL/6, Swiss Webster), 3-4 months old, individually housed.

- Virgin female mice, 8-15 weeks old.

- Standard rodent cages and bedding.

Methodology:

- Pre-conditioning of Males: House stud males individually for 1-2 weeks prior to mating to maximize sperm count and fertility [21].

- Estrous Cycle Synchronization (Optional but Recommended): Group-house female mice (4-10 per cage) for 10-14 days to synchronize their estrous cycles via the Lee-Boot effect. For enhanced synchronization, introduce soiled bedding from a male's cage into the females' cage 48-72 hours before mating to induce the Whitten effect [21].

- Visual Estrous Staging: In the late afternoon prior to mating, select females that are in proestrus or estrus. Indicators include a swollen, pink, and moist vaginal opening [21].

- Timed Mating: In the evening, place 1-2 selected females into a single-housed male's cage.

- Plug Check: Check females for the presence of a vaginal plug early the next morning. The plug is a viscous substance from the male ejaculate that fills the vagina [21].

- Designation of Gestational Day: The morning a vaginal plug is identified is designated as Gestational Day 0.5 (E0.5) or 0.5 days post-coitum (dpc) [21].

Application Notes:

- A vaginal plug confirms copulation but not necessarily pregnancy. Using females in estrus increases the pregnancy-to-plug incidence to 80-90% [21].

- Strains with superior reproductive performance, such as outbred Swiss Webster mice, are preferred for generating large embryo yields. Inbred strains like C57BL/6 are used when genetic uniformity is required but have smaller litter sizes [20].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) and Embryo Culture

For experiments requiring genetic manipulation or precise control over fertilization, IVF is employed.

Objective: To generate embryos in vitro and culture them to specific developmental stages for use as timed donors. Materials:

- Hormones: Pregnant Mare's Serum Gonadotropin (PMSG), Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG).

- M2 and KSOM embryo culture media.

- Mineral oil for embryo culture overlay.

- CO₂ incubator maintained at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Methodology:

- Superovulation: Administer an intraperitoneal injection of 7.15 IU PMSG to donor female mice, followed by 5 IU hCG 48 hours later [22].

- Oocyte and Sperm Collection: 13-14 hours post-hCG, euthanize females and collect oocytes from the oviductal ampullae. Collect sperm from the cauda epididymis of a stud male [22].

- In Vitro Fertilization: Co-incubate oocytes and capacitated sperm in fertilization medium (e.g., HTF) for 4-6 hours [17] [22].

- Embryo Culture:

- Day 0/1: Approximately 16-18 hours post-insemination, assess fertilization by identifying zygotes with two pronuclei (2PN). Wash and transfer to fresh culture medium [18].

- Days 1-3 (Cleavage Stages): Culture embryos, checking for division to 2-cell, 4-cell, and 8-cell stages. Transfer to sequential medium optimized for later stages if culturing to blastocyst [18].

- Days 4-5 (Morula to Blastocyst): Culture embryos until the morula compact and form blastocysts [18].

Application Notes:

- Supplementing culture medium with oviductal extracellular vesicles (EVs) from specific estrous stages (estrus, metestrus, diestrus) can significantly improve blastocyst yield and quality by better mimicking the in vivo environment [23].

- Only about 50% of fertilized embryos typically develop to the blastocyst stage under standard in vitro conditions [19].

Advanced Assessment and Manipulation of Timed Donors

Non-Invasive Metabolic Assessment

Raman spectroscopy offers a non-invasive method to assess the developmental potential of timed donor embryos by analyzing their metabolic profile.

Principle: This technique quantifies dynamic changes in glucose consumption from the culture medium and maps intracellular distributions of biomolecules like lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids within the embryo [22].

Key Findings:

- Glucose metabolism is stable from E0.5 to E3.5 but increases significantly around the morula-to-blastocyst transition (E4.5), peaking during blastocyst formation [22].

- Embryos that successfully form blastocysts ("encapsulated group") demonstrate a higher glucose metabolic ratio compared to those that arrest ("unencapsulated group") as early as E1.5 [22].

- Raman imaging reveals a high concentration of lipid droplets in the cytoplasm of 1-cell and 2-cell embryos, which are progressively consumed during subsequent development [22].

Application: This metabolic phenotyping can be integrated into the timed donor pipeline to non-invasively select the most viable embryos for transfer or experimental use, thereby increasing experimental efficiency.

The Critical Protocol of Isochronic Cell Injection

The requirement for developmental timing is most rigorously demonstrated in chimera generation experiments.

Objective: To functionally test the developmental competence of donor cells by injecting them into host embryos. Materials:

- Timed donor embryos (e.g., at E3.5 blastocyst stage).

- Donor cells (e.g., Embryonic Stem Cells - ESCs, or Neural Crest Cells - NCCs).

- Microinjection setup.

Methodology and Evidence:

- Isochronic Injection (Matched): Inject pluripotent ESCs into a host blastocyst (E3.5). This results in robust chimera formation with donor cell contribution to all tissues [16].

- Heterochronic Injection (Mismatched):

Conclusion: Successful chimera formation is exclusively dependent on isochronic injection. Donor cells must be developmentally matched to the host embryo's stage to integrate functionally into the developmental program [16]. This principle directly defines the "Timed Donor"—its value is relative to the specific developmental context of the host system.

Diagram: Developmental Match is Crucial for Chimera Formation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Timed Donor Embryo Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PMSG & hCG | Hormonal regimen for superovulation in mice to obtain a large, synchronized cohort of oocytes [22]. | Typically administered 48 hours apart (e.g., 7.15 IU PMSG, then 5 IU hCG) [22]. |

| KSOM / mHTF Media | Sequential culture media designed to support the changing metabolic needs of the preimplantation mouse embryo from zygote to blastocyst [18] [22]. | |

| Oviductal Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) | Supplement to in vitro culture media to improve embryonic development by providing maternal cues; efficacy is stage-dependent (estrus, metestrus, diestrus) [23]. | Isolated from oviductal fluid; contain cargo (proteins, miRNAs) that support embryo development [23]. |

| Proven Stud Males | Reliable mating partners for setting up timed pregnancies. Strains like Swiss Webster (outbred) or C57BL/6J (inbred) are commonly used [20] [21]. | Isolated housing for 1-2 weeks prior to mating improves success rates [21]. |

| CD-1 or Swiss Webster Foster Females | Pseudopregnant recipient females for embryo transfer following IVF or genetic manipulation. | Vasectomized males are used to induce pseudopregnancy in these females. |

The "Timed Donor" is not merely a chronological concept but a biological standard defined by rigorous developmental synchrony. From the initial setup of timed matings to the final validation of developmental competence through metabolic profiling or functional chimera assays, every step must be calibrated against the intrinsic clock of embryonic development. The protocols and assessment tools outlined here provide a framework for achieving this critical precision, ensuring that donor embryos serve as reliable and reproducible tools in advanced biomedical research. Adherence to these principles of developmental staging is fundamental to the generation of robust, interpretable, and impactful scientific data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Equipment and Reagents

Successful mouse in vitro fertilization (IVF) relies on specialized equipment and rigorously tested reagents to ensure consistent and reproducible results for colony management and timed embryo production.

Core Equipment Essentials

Table 1: Essential Equipment for Mouse IVF Protocols

| Equipment Category | Specific Instrument | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Control | Humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂) [24] | Maintains physiological conditions for gamete co-incubation and embryo culture. |

| Microscopy | Stereomicroscope [24] | Macroscopic procedures: dissecting oviducts, collecting oocytes, and handling embryos. |

| Inverted microscope [24] | Detailed assessment of oocytes, sperm motility, and fertilization status (pronuclei observation). | |

| Sample Handling | Micropipettes & specific pipette tips (e.g., for insemination) [24] | Precise handling and transfer of small fluid volumes, sperm, and embryos. |

| Procedure Consumables | Plastic dishes (e.g., 35mm x 10mm) [24] | Preparation of sperm, fertilization, and embryo washing drops under paraffin oil. |

| Glass capillaries [24] | Gentle handling and transfer of embryos between culture drops. | |

| Surgical Tools | Fine scissors, watchmaker's forceps (#5), micro-spring scissors, dissecting needle [24] | Surgical dissection of reproductive tissues and collection of oocytes and sperm. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Media for Mouse IVF

| Reagent/Media | Function | Examples & Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| Hormones for Superovulation | Stimulate follicle development and trigger ovulation in female donors. | PMSG (Pregnant Mare's Serum Gonadotropin), hCG (human Chorionic Gonadotropin) [25] [24]. |

| Sperm Preincubation Medium | Supports sperm capacitation, a prerequisite for fertilization. | FERTIUP PM (CARD) [24]; c-TYH medium (contains methyl-β-cyclodextrin for cholesterol efflux) [26]. |

| Fertilization Medium | The environment where sperm and oocytes are co-incubated for IVF. | CARD MEDIUM [24]; modified RVF (mRVF) with elevated calcium and glutathione [26]; HTF (Human Tubal Fluid) [26]. |

| Embryo Culture/Washing Medium | Supports development of fertilized embryos to transferable stages. | mHTF [24]; KSOM (Potassium Simplex Optimized Medium) [27]. |

| Cryopreservation Reagents | Protects sperm during freezing and thawing for archiving and recovery. | Cryoprotective Agent (CPA) with raffinose and skim milk, supplemented with L-glutamine (CARD) or monothioglycerol (JAX) [26] [28]. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocols

The mouse IVF process is a multi-stage procedure requiring precise coordination. The following workflow outlines the key steps from preparation to embryo transfer.

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for mouse in vitro fertilization (IVF), detailing the sequential steps from donor preparation to embryo transfer.

Detailed Protocol: Superovulation of Donor Females

Superovulation increases the yield of oocytes for fertilization [25].

- Hormone Preparation: Reconstitute PMSG and hCG in sterile saline (e.g., 37.5 IU/mL) [24]. Aliquot and store frozen at -20°C.

- PMSG Injection: Administer an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of PMSG (e.g., 5.0 IU) to 3-5 week-old young female mice during the light cycle, typically between 2:00 PM and 6:00 PM [25] [24]. This stimulates follicular development.

- hCG Injection: Administer an IP injection of hCG (e.g., 5.0 IU) 48 hours after the PMSG injection [25] [24]. This triggers ovulation. Oocytes will be ready for collection 15-17 hours post-hCG.

The quality of sperm directly correlates with fertilization success [25].

- Collection: Sacrifice a mature male mouse (3-6 months old). Isolate the cauda epididymides, minimizing contact with fat and blood. Place the tissue in a drop of pre-equilibrated preincubation medium under mineral oil [24].

- Release Sperm: Puncture the epididymal ducts with fine scissors or a needle and gently squeeze to release the sperm mass [24].

- Capacitation: Transfer the sperm clots into the preincubation drop (e.g., FERTIUP PM or c-TYH). Incubate for 60 minutes in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂ to allow for capacitation. Sperm with high fertility will show vigorous, vortex-like movement [24].

Detailed Protocol: Oocyte Collection and In Vitro Fertilization

- Oocyte Collection: Sacrifice superovulated females 15-17 hours post-hCG. Rapidly dissect and remove the oviducts (ampullae). Using forceps and a needle, tear open the ampulla under oil in a fertilization dish to release the cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) into the CARD MEDIUM or mRVF drop [24]. The entire process from sacrifice to COC release should be completed as quickly as possible (within 30 seconds per mouse) [24].

- Insemination: After capacitation, add approximately 3 µL of the sperm suspension to the fertilization drop containing the COCs [24]. Co-incubate the gametes for 3-6 hours in the incubator.

Post-IVF Embryo Handling and Culture

- Washing and Assessment: After 3-6 hours of co-incubation, wash the oocytes several times in fresh washing medium (e.g., mHTF) to remove excess sperm and debris [24].

- Fertilization Check: At around 6 hours post-insemination, observe the oocytes for pronuclei. A fertilized oocyte will have two pronuclei (male and female), while an unfertilized oocyte has none, and a parthenogenetic oocyte has only one [24]. Remove unfertilized and parthenogenetic oocytes.

- Embryo Culture: Culture the presumed fertilized oocytes overnight. Successful fertilization is confirmed by the formation of 2-cell embryos the next day [25] [24]. These 2-cell embryos can then be surgically transferred to pseudo-pregnant recipient females or cultured further to the blastocyst stage in media like KSOM for experimental analysis [27].

Quantitative Data and Protocol Comparisons

Cryopreservation Methodologies

Cryopreservation is a key component of managing genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) resources, with sperm cryopreservation now often preferred for its efficiency [28].

Table 3: Comparison of Mouse Sperm Cryopreservation Protocols

| Parameter | CARD (Nakagata) Protocol | JAX (Ostermeier) Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cryoprotectant Agent (CPA) | L-glutamine [26] [28] | Monothioglycerol (MTG) [26] [28] |

| Sperm Source | Cauda epididymis [28] | Vas deferens and cauda epididymis [28] |

| Preincubation Medium | c-TYH (with methyl-β-cyclodextrin) [26] | HTF or commercial RVF medium [26] |

| Fertilization Medium | HTF with elevated calcium & glutathione [26] | HTF or RVF [26] |

| Typical Scale | 18-20 straws from 2 males [28] | ~25 straws from 2 males [28] |

Quality Control Benchmarks

Rigorous quality control is essential for a reliable cryopreservation and IVF program [25] [28].

Table 4: Standard Quality Control Metrics in Mouse IVF and Cryopreservation

| Process | QC Metric | Passing Standard | Consequence of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm Cryopreservation | Fertilization Rate via IVF | ≥20% 2-cell embryos [25] | Core may repeat at 50% cost [25] |

| Embryo Cryopreservation | Post-thaw Viability Rate | >60% embryo survival [25] | N/A |

| In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) | Pup Birth Rate | Highly variable (10-60+ pups); no pups indicates failure [25] | Core may repeat at 50% cost if more sperm is available [25] |

Advanced culture techniques continue to be explored to further improve embryo development in vitro. A 2025 study demonstrated that supplementing culture media with oviductal extracellular vesicles (EVs) from specific stages of the estrous cycle (estrus, metestrus, diestrus) significantly improved blastocyst yield and hatching rates in mouse IVF embryos [23].

Step-by-Step IVF Protocol for Generating Precisely Timed Embryos

Superovulation is a fundamental technique in reproductive biology and transgenic science, used to artificially induce the release of a large number of oocytes from female mice at a predictable time. This process is a critical first step for in vitro fertilization (IVF), zygote collection for pronuclear injection, and embryo cryopreservation, enabling the efficient generation and preservation of genetically engineered mouse models. The core of the superovulation protocol involves the sequential administration of two gonadotropin hormones: pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG), which mimics follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to stimulate the growth of multiple follicles, and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which mimics luteinizing hormone (LH) to induce final oocyte maturation and ovulation. The precise timing of these injections is paramount to maximizing oocyte yield and quality for subsequent experimental procedures. This application note details established hormonal schedules and provides essential optimization data to frame this technique within the context of a timed IVF protocol for embryo donor mice.

Experimental Protocol: Standard Superovulation Procedure

The following protocol outlines the standard methodology for superovulating mice, as utilized by leading research institutions [29] [30] [31].

Reagents and Materials

- PMSG: Lyophilized powder, reconstituted in sterile PBS or saline.

- hCG: Lyophilized powder, reconstituted in sterile PBS or saline.

- Female Mice: Typically 3-5 weeks old, depending on strain.

- Stud Male Mice: 8 weeks or older, proven breeders.

- 1 ml Syringes and Fine Needles (e.g., 27 G).

- Sterile PBS.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Hormone Preparation: Reconstitute PMSG and hCG according to manufacturer instructions. Aliquot and store frozen at -20°C or -80°C. Before injection, dilute aliquots to a concentration of 50 IU/ml to deliver a 5 IU dose in a 0.1 ml volume [29] [31].

- PMSG Injection: On Day 1, intraperitoneally (IP) inject each female mouse with 5 IU of PMSG (0.1 ml of a 50 IU/ml solution). This is typically performed in the afternoon, between 1:00 PM and 4:00 PM [29] [30].

- hCG Injection: After precisely 42 to 52 hours (typically on Day 3), IP inject each female with 5 IU of hCG (0.1 ml of a 50 IU/ml solution) [30] [13].

- Mating: Immediately following the hCG injection, place each superovulated female into a cage with a single stud male mouse [29].

- Oviduct and Oocyte/Embryo Collection:

- For zygote collection (0.5 days post coitum, dpc), check for a vaginal copulatory plug the next morning (Day 4). Harvest zygotes from the oviducts [29].

- For morula collection (2.5 dpc), harvest embryos from the oviducts or uterus [29].

- For blastocyst collection (3.5 dpc), flush embryos from the uterus [31].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequence and timing of these key steps.

Strain-Specific Optimization of Hormone Schedules

The standard 5 IU PMSG/5 IU hCG protocol does not yield optimal results for all mouse strains. Genetic background significantly influences the superovulation response, necessitating adjustments to hormone dosage and the age or weight of the donor female [32]. The table below summarizes optimized parameters for several commonly used inbred and hybrid strains.

Table 1: Strain-Specific Optimization for Superovulation

| Mouse Strain | Optimal Female Weight | Optimal PMSG Dose | Optimal Protocol Notes | Expected Oocyte Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | 10.5 - 14.4 g [32] | 5 IU [32] | Younger, lighter females within this range respond best. Two doses of 5 IU PMSG one week apart may increase yield [32]. | Good [32] |

| FVB/N | 14.5 - 16.4 g [32] | 5 IU [32] | Best response in this weight range, though oocyte yield can be variable [32]. | Variable [32] |

| BALB/c | ≤ 14.8 g [32] | 5 IU [32] | Best response in younger, lighter females [32]. | Good [32] |

| B6D2F1 | 6.0 - 9.9 g [32] | 5 IU [32] | This hybrid strain responds well at a very young age and low weight [32]. | Excellent [32] |

| B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J | ≤ 13.7 g [32] | 2.5 IU [32] | A lower PMSG dose (2.5 IU) produces more oocytes than the standard 5 IU dose [32]. | Improved with lower dose [32] |

| CD-1 (ICR) | ≥ 23.5 g [32] | 5 IU [32] | Unlike most strains, older, heavier females yield a better superovulation response [32]. | Good [32] |

Integrated Application in an IVF Workflow

Superovulation is the initial and most critical step in a multi-day IVF and embryo culture workflow. The timing of hormone injections dictates the schedule for all subsequent steps, from sperm preparation to embryo transfer. The following diagram integrates the superovulation schedule into a complete, timed IVF protocol, such as the CARD (Center for Animal Resources and Development) method [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful superovulation and subsequent IVF rely on high-quality, specific reagents. The following table lists key materials and their functions in the protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| PMSG (e.g., Sigma G4877) | A gonadotropin with FSH-like activity; stimulates the synchronous development of a large cohort of ovarian follicles [29] [30]. |

| hCG (e.g., Sigma C1063) | A gonadotropin with LH-like activity; triggers final oocyte maturation and ovulation approximately 12-15 hours after administration [29] [30]. |

| FERTIUP Medium | Sperm pre-incubation medium used for sperm capacitation for 30-60 minutes prior to IVF [13]. |

| CARD MEDIUM | Specialized fertilization medium; cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) are incubated here prior to and during insemination [13]. |

| mHTF Medium | Modified Human Tubal Fluid medium; used for washing and culturing embryos after fertilization [13]. |

| Mineral Oil (Embryo-tested) | Used to overlay microdrop cultures of media to prevent evaporation and maintain pH and osmolarity [33] [13]. |

| IBMX (3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine) | A phosphodiesterase inhibitor used in oocyte collection medium to maintain meiotic arrest at the Germinal Vesicle (GV) stage for synchronized in vitro maturation [33]. |

The hormonal superovulation schedule using PMSG and hCG is a well-established but finely tunable technique. The consistent success of this procedure in generating high-quality, developmentally competent oocytes and embryos hinges on three principal factors: the precise timing of hormone injections to mimic the natural estrous cycle, the adaptation of the protocol to the genetic background of the mouse strain, and the integration of this schedule with downstream IVF or embryo collection steps.

As detailed in the protocols and data above, a one-size-fits-all approach is suboptimal. Researchers must empirically determine the best combination of female age/weight and hormone dose for their specific mouse strain to maximize oocyte yield and minimize the number of animals used, in accordance with the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) [32]. When optimized and seamlessly integrated into a comprehensive IVF workflow—from sperm preparation to embryo culture and transfer—the superovulation protocol becomes a powerful and reproducible tool for the efficient production of timed embryos, ensuring the success of advanced research in genetics, development, and drug discovery.

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for sperm collection and preparation, framed within the context of In vitro fertilization (IVF) protocol for timed embryo donor mice research. The procedures outlined are critical for generating genetically engineered mouse models and for reproductive toxicology studies. Standardized and efficient sperm handling techniques directly impact key research metrics, including fertilization rates, embryo quality, and the overall success of transgenic mouse line propagation. The following sections provide a comprehensive guide to the core methodologies for collecting and processing both fresh and frozen sperm samples, complete with quantitative comparisons and detailed workflows.

Sperm Collection Techniques

The method of sperm collection is chosen based on the experimental design, the desired genetic outcome, and the availability of donor males.

Masturbation and Ejaculate Collection

This is the standard method for obtaining sperm from larger animal models. For murine models, this is less common but can be adapted.

- Key Protocol Steps:

- Abstinence Period: Observe a period of abstinence (no ejaculation) for at least two days but not more than five days before collection to optimize sperm quantity and quality [34].

- Collection Container: Collect semen in a sterile, non-toxic plastic specimen cup provided by the laboratory. Commercial condoms are not acceptable as they are toxic to sperm [34].

- Handling and Transport: Wash and dry hands prior to collection. Do not use lubricants unless specifically directed by a protocol. If collected at home, minimize transit time and transport the sample at room or body temperature [34].

Surgical Sperm Retrieval

For mice, sperm is typically collected post-sacrifice from the epididymides. In azoospermic (no sperm in ejaculate) research models, surgical retrieval is necessary.

Epididymal Sperm Collection (for Mice):

- Euthanize the donor male mouse following approved animal welfare protocols.

- Excise the cauda epididymides (the tail of the epididymis) and place them in a pre-warmed culture medium.

- Puncture or mince the epididymal tissue with fine needles or a scalpel blade to allow sperm to swim out into the medium [35].

- Assess the sperm number and motility under a microscope. If insufficient, the IVF process may be cancelled [35].

Microdissection Testicular Sperm Extraction (Micro-TESE): This is a sophisticated surgical technique used in azoospermic models where sperm production is impaired. It is the gold standard for sperm retrieval in cases of non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) [36].

- The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with the aid of an operating surgical microscope.

- A midline incision is made in the testis to expose the parenchyma.

- The seminiferous tubules are examined; more dilated, opaque tubules are selected for extraction as they are more likely to contain sperm [36].

- The retrieved tissue is processed by the embryology lab. Technicians extract sperm cells from the tubules using fine needles or glass slides, sometimes employing enzymatic digestion with collagenase to facilitate extraction [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Sperm Retrieval Techniques in a Research Context

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Sperm Retrieval Rate (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masturbation/Ejaculate | Non-surgical collection from capable subjects | Non-invasive; high yield from fertile males | Not applicable to murine models or azoospermic subjects | N/A |

| Epididymal Collection | Standard murine IVF; obstructive azoospermia | High yield of mature, motile sperm from mice | Requires euthanasia of the donor male [35] | Dependent on male fertility |

| Micro-TESE | Non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) models | Highest retrieval rate for NOA; minimal tissue removal [36] | Requires specialized microsurgical expertise and longer operating time [37] | 40-60% [36] |

| Testicular Sperm Aspiration (TESA) | Obstructive azoospermia models | Simple, cost-effective needle aspiration [37] | Lower retrieval rate compared to Micro-TESE; may not provide enough tissue [37] | Lower than Micro-TESE |

Sperm Collection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting an appropriate sperm collection method based on the research model and objectives.

Sperm Preparation and Processing Techniques

Sperm preparation techniques are designed to select a population of motile, morphologically normal, and viable spermatozoa while removing seminal plasma, dead sperm, and other contaminants.

Standard Preparation Methods

Swim-Up Technique: This method leverages the innate motility of healthy sperm. The sperm sample is placed under a layer of culture medium. Motile sperm swim up into the medium, which is then collected.

- Mix the sperm sample with a washing medium volume-to-volume (v/v) and centrifuge (e.g., 320g for 10 minutes) [38].

- Discard the supernatant and gently layer culture medium over the pellet.

- Incubate the tube at a 45-degree angle for 30-60 minutes in a CO₂ incubator.

- Carefully harvest the top medium layer, which is now enriched with motile sperm [38].

Density Gradient Centrifugation (DGC): This technique uses a colloidal silica gradient to separate sperm based on their buoyancy and motility. Mature, morphologically normal sperm with intact DNA penetrate further into the gradient.

Advanced Sperm Sorting

- Microfluidic Sperm Sorting: This technology uses microfluidic chips to isolate progressive motile sperm directly from the ejaculate based on their swimming ability and hydrodynamic properties. A study comparing it to the swim-up technique found significantly higher sperm concentration, progressive motility levels, and fertilization rates in the microfluidic group [39].

Preparation Technique Outcomes

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Sperm Preparation Techniques

| Technique | Sperm Concentration Recovery | Progressive Motility Recovery | Fertilization Rate | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swim-Up | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Good for normozoospermic samples; common standard [38] |

| Density Gradient Centrifugation | Higher than Swim-Up | Higher than Swim-Up | Comparable to Swim-Up | Effective for samples with debris and dead sperm [38] |

| Microfluidic Sorting | Significantly Higher [39] | Significantly Higher [39] | Significantly Higher [39] | Emerging technology for superior motile sperm selection |

Cryopreservation of Sperm

Sperm cryopreservation, or sperm banking, is a fundamental technique for preserving valuable genetic material from transgenic mouse lines for future IVF cycles or distribution.

Cryopreservation Protocols

Conventional Slow Freezing:

- The sperm sample is mixed with a cryoprotectant solution (e.g., containing glycerol) to protect the cells from ice crystal formation [40] [36].

- The mixture is loaded into straws or vials.

- Using a programmable freezer, the sample is cooled at a controlled, slow rate (e.g., -10°C/min) [36].

- The frozen samples are plunged into liquid nitrogen for long-term storage at -196°C [40].

Vitrification: This method uses ultrarapid cooling to transform cellular water into a glass-like state without forming ice crystals.

- Sperm are suspended in a higher concentration of cryoprotectants.

- A very small volume of the sample is directly plunged into liquid nitrogen, achieving extremely high cooling rates [36].

- While promising, the World Health Organization still considers sperm vitrification an experimental technique [36].

Pre-freeze Processing: A Critical Factor

Research indicates that the timing of sperm preparation relative to freezing significantly impacts post-thaw quality.

- Freezing BEFORE Swim-up (Recommended): Cryopreserving the whole ejaculate prior to sperm selection leads to higher total and progressive motility, total motile sperm count, and viability rates after thawing. The seminal plasma has a protective role during the freezing process, containing antioxidants that prevent reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced damage [38].

- Freezing AFTER Swim-up: Performing sperm selection prior to freezing reaches critical values, especially when subfertile patients or models are considered, leading to poorer post-thaw outcomes [38].

Fresh vs. Frozen Sperm in ART

The choice between using fresh or frozen sperm involves a trade-off between sperm quality and logistical flexibility.

Table 3: Comparison of Fresh vs. Frozen Sperm Use in ART Cycles

| Parameter | Fresh Sperm | Frozen Sperm |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Quality | Generally higher quality metrics (motility, viability) [36] | Some quality loss due to cryodamage; vitrification improves outcomes [36] |

| Logistical Flexibility | Requires perfect timing with oocyte retrieval | Decouples sperm retrieval from IVF cycle; available as backup [40] [36] |

| Fertilization Rate | Traditionally higher | Comparable rates in many studies [41] [36] |

| Pregnancy/Live Birth Rate | Slightly higher in some studies | Comparable to fresh in many cases, especially with donor sperm [41] [36] |

| Application in Mouse Research | Used when a male is euthanized for immediate IVF [35] | Essential for preserving and distributing valuable genetic lines [35] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sperm Collection and Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cryoprotectant Agents | Protect sperm from ice crystal damage during freezing/thawing by replacing intracellular water. | Glycerol, Ethylene Glycol, sucrose, trehalose [40] [36] |

| Holding/Culture Media | Provide a physiological environment for sperm during collection, processing, and incubation. | Human Tubal Fluid (HTF), Flushing Medium, IVF Medium [38] |

| Density Gradient Medium | Form a density barrier for centrifugation-based selection of motile, morphologically normal sperm. | Colloidal Silica Suspensions |

| Hypoosmotic Swelling Test (HOS) Solution | Assess sperm membrane integrity and viability; viable sperm with intact membranes exhibit tail swelling. | Solution of sodium citrate and fructose [38] |

| Enzymatic Digestion Agents | Facilitate the extraction of sperm from dense testicular tissue in surgical retrievals. | Collagenase [36] |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Provides ultra-low temperature environment (-196°C) for long-term cryostorage of sperm samples. | N/A [40] |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The following diagram summarizes the complete integrated workflow for sperm collection, processing, cryopreservation, and use in IVF, contextualized for research settings.

Oocyte Collection and Cumulus Complex Isolation from Donor Females

The isolation of high-quality cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) from donor females is a critical foundational step in mouse in vitro fertilization (IVF) research. This procedure enables the generation of timed embryos for studying development, genetic modification, and colony management. Efficiency in oocyte collection and the subsequent removal of cumulus cells are paramount for achieving high fertilization and blastocyst formation rates. This application note details a standardized, reliable protocol for oocyte collection and COC isolation, incorporating both established methods and emerging technologies to enhance reproducibility and success in a research setting.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential reagents and materials required for the successful execution of oocyte collection and cumulus complex isolation.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Oocyte Collection and Cumulus Complex Isolation

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin (PMSG) | Hormonal priming to stimulate follicle growth and superovulation [42] [14]. | Typically 5-10 IU administered via intraperitoneal injection [42] [13]. |

| Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) | Triggers final oocyte maturation and ovulation [42] [14]. | 5-10 IU injected 46-52 hours after PMSG [42] [13]. |

| Hyaluronidase | Enzyme that digests hyaluronic acid matrix, loosening cumulus cells for removal [42] [43]. | Concentration and exposure time must be optimized (e.g., 30-120 seconds) [43]. |

| Handling Media (e.g., M2, HTF-HEPES) | Maintains pH and osmotic balance during oocyte collection and manipulation outside the incubator [42] [14]. | Used for dissecting oviducts and collecting COCs. |

| Fertilization/Culture Media (e.g., CARD, HTF, KSOM-AA) | Supports sperm capacitation, fertilization, and subsequent embryo development [13] [14]. | Pre-equilibrated in a CO₂ incubator prior to use. |

| Mineral Oil (Embryo-tested) | Overlays culture media drops to prevent evaporation and osmolarity shifts [13] [14]. | Light mineral oil, pre-gassed. |

| Wide-Bore Pipettes/Tips | For handling COCs and denuded oocytes without causing mechanical damage to the zona pellucida [13] [14]. | Essential for manual pipetting steps. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The overall process from preparing donor mice to obtaining isolated oocytes ready for IVF is a multi-day procedure. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages and their temporal relationships.

Superovulation of Donor Females

The process begins with the hormonal stimulation of prepubertal or young adult female mice (typically 4-6 weeks old) to maximize oocyte yield [42] [35].

- Day 1: Administer an intraperitoneal injection of 5-10 IU of PMSG to stimulate follicular development [42] [13] [14].

- Day 3: Approximately 46-52 hours after the PMSG injection, administer an intraperitoneal injection of 5-10 IU of hCG to trigger final oocyte maturation and ovulation [42] [13]. Oocyte collection is performed 13-17 hours post-hCG injection [14].

Oocyte Collection and Cumulus-Oocyte Complex (COC) Isolation

The following protocol details the steps for collecting COCs after the administration of hCG.

- Sacrifice and Dissection: At 13-17 hours post-hCG injection, euthanize the donor females according to approved institutional protocols [13]. Quickly dissect to expose the reproductive tract. Remove the oviducts, trimming away excess fat and connective tissue.

- COC Release: Place the oviducts into a dish containing pre-equilibrated handling medium (e.g., M2 or HTF-HEPES) under oil. Using fine forceps (#5), carefully tear open the swollen ampulla of the oviduct to release the dense, cloud-like cumulus mass containing the oocytes [13] [14].

- COC Harvesting: Using a wide-bore pipette tip to prevent damage, transfer the cumulus masses from multiple females into a pre-equilibrated fertilization dish (e.g., containing CARD medium or HTF) [13]. Incubate the collected COCs for 30-60 minutes before proceeding with cumulus removal [13].

Cumulus Cell Removal

Cumulus removal (CR) is essential for assessing oocyte maturity prior to Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) and for preventing genetic contamination in subsequent preimplantation genetic testing [43] [44]. The following methods are commonly employed.

Table 2: Methods for Cumulus Cell Removal

| Method | Protocol | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic + Mechanical | Incubate COCs in a hyaluronidase solution (concentration and time as per manufacturer's guidelines, typically 30-120 sec) to dissolve the hyaluronic acid matrix. Subsequently, pipet the COCs gently with a wide-bore pipette to dislodge the loosened cumulus cells [42] [43]. Wash oocytes thoroughly to remove enzyme and cellular debris. | Standard and widely used. Requires careful timing to avoid oocyte exposure to the enzyme. |

| Mechanical Pipetting | Repeatedly aspirate and dispense the COCs using a narrow-bore pipette (manually or via a robotic system) in a medium without enzyme [44]. The shear force physically strips away the cumulus cells. | Avoids potential chemical stress from enzymes. Requires skill to prevent oocyte loss or damage. |

| Advanced Platforms (Vibration/Robotic) | Vibration-Induced Flow (VIF): Uses an open-surface microfluidic chip with micropillars. Applied vibration creates a flow that selectively removes smaller cumulus cells, leaving oocytes in the loading chamber. Achieves ~99% cell removal efficiency without enzymes [43].Robotic Systems: Employ machine vision to assess oocyte maturity and adaptive control to position COCs accurately during aspiration, achieving high success (98%) and low discard rates [44]. | Promising for standardization and reduced manual labor. Requires specialized equipment. |

Quality Assessment and Troubleshooting

Post-collection assessment is critical for ensuring only high-quality oocytes are used for IVF.

- Oocyte Morphology: Exclude oocytes with very poor morphology, such as dark cytoplasm or fragmented structure [42].

- Embryo Source Quality: If the mice produce fewer than 10 embryos or if the fertilization rate in a group is below 40%, the entire batch may be deemed non-representative due to potential issues with hormone injection or media, and should be excluded from experimental data [42].

- Quantitative Assessment: The use of improved YOLOv5s networks has been demonstrated to quantitatively assess the completeness of cumulus cell removal, ensuring minimal contamination [44].

The reliable collection of oocytes and isolation of cumulus complexes is a technically demanding but essential skill for mouse IVF research. Adherence to a standardized protocol for superovulation, dissection, and cumulus removal, as detailed herein, ensures the consistent yield of high-quality oocytes. The integration of emerging automated technologies for cumulus removal holds significant promise for enhancing reproducibility, throughput, and success rates in generating timed embryos for downstream applications.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) is a cornerstone technique in reproductive biology and genetic engineering, particularly in the creation of genetically modified mouse models for research. The stages of insemination and oocyte co-incubation are critical, as the conditions during these phases directly impact fertilization success, embryonic development, and the viability of resulting embryos. This application note provides a detailed protocol and data analysis for these stages, contextualized within a broader thesis on IVF protocols for timed embryo donor mice. It is designed to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in optimizing laboratory procedures.

Impact of Co-incubation Time on IVF Outcomes

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials provides a direct comparison of outcomes between brief (1-6 hours) and long (16-24 hours) gamete co-incubation times [45]. The data below summarize the combined odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for key reproductive outcomes, favoring brief co-incubation when the OR is greater than 1.

Table 1: Outcomes of Brief vs. Long Gamete Co-incubation [45]

| Outcome Measure | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implantation Rate | 1.97 | 1.52 – 2.57 | Significant |

| Ongoing Pregnancy Rate | 2.18 | 1.44 – 3.29 | Significant |

| Top-Quality Embryo Rate | 1.17 | 1.02 – 1.35 | Significant |

| Live-Birth Rate | 1.09 | 0.72 – 1.65 | Not Significant |

| Clinical Pregnancy Rate | 1.36 | 0.99 – 1.87 | Not Significant |

| Miscarriage Rate | 1.32 | 0.55 – 3.18 | Not Significant |

| Polyspermy Rate | 0.80 | 0.48 – 1.33 | Not Significant |

| Normal Fertilization Rate | 0.89 | 0.80 – 0.99 | Significant (Lower) |

Genetic and Developmental Outcomes of IVF in Mice

Recent research in mouse models highlights the importance of protocol optimization. The data below summarize key findings on genetic integrity and the impact of a modified warming protocol (MWP) for vitrified oocytes.

Table 2: Genetic and Developmental Outcomes in Mouse and Donor Oocyte IVF

| Parameter | Finding | Notes and Context |

|---|---|---|

| New Single-Nucleotide Variants | ≈30% increase in IVF-conceived pups [4] | Compared to natural conception; mutations are spread across the genome and are largely neutral [4]. |

| Absolute Risk of Harmful Mutation | ≈1 additional harmful change per 50 IVF mice [4] | Risk considered "almost negligible" due to genome size [4]. |

| Usable Blastocyst Formation (MWP) | 51.4% [46] | MWP group performed similarly to fresh oocytes (48.5%) and better than conventional warming (35.4%) [46]. |

| Ongoing Pregnancy/Live Birth (MWP) | 66.7% [46] | MWP group showed a significant improvement over the conventional warming protocol (50.4%) [46]. |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Mouse IVF and Co-incubation

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for a mouse IVF procedure, from superovulation to embryo culture.

Detailed Protocol: Insemination and Co-incubation for Mouse IVF

This protocol synthesizes methodologies from established sources [13] [14].

I. Pre-insemination Preparation

- Fertilization Dish Preparation: On the afternoon prior to IVF, prepare the fertilization dish. For every 4-6 superovulated females, place a central 200 µL drop of pre-equilibrated fertilization medium (e.g., CARD medium or HTF) in a culture dish. Cover the drop with pre-gassed, embryo-tested light mineral oil and place the dish in the incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂) at least 10 minutes before the first oocyte collection [13].

- Sperm Preparation:

- Fresh Sperm: Sacrifice a male mouse. Dissect out the cauda epididymides and vasa deferentia, removing excess fat. Place them in a 1 mL drop of sperm preincubation medium (e.g., FERTIUP or HTF) under oil. Mince the tissue with a needle to release sperm and incubate the dish for 30-60 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for capacitation [13] [14].

- Frozen/Sperm: Thaw a cryovial in a 37°C water bath. For some protocols, the thawed sperm can be expelled directly into a pre-warmed drop of FERTIUP and incubated for 30 minutes before use [13]. Alternatively, the sperm can be washed via centrifugation (735g for 4 minutes) and resuspended in HTF before insemination [14]. Assess sperm motility and concentration.

II. Oocyte Collection and Insemination

- Collect cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) from superovulated females approximately 13 hours post-hCG injection. Place the torn ampullae in the oil of the fertilization dish and release the COCs directly into the pre-equilibrated fertilization medium drop. Return the dish to the incubator for 30-60 minutes [13].

- Insemination: After capacitation, add a 3-10 µL aliquot of the motile sperm suspension to the fertilization dish containing the COCs. Use wide-bore pipette tips to avoid damaging gametes. The final motile sperm concentration in the drop should be between 1x10⁶ to 2.5x10⁶ sperm/mL [13] [14].

III. Co-incubation and Post-Incubation Handling

- Co-incubation: Incubate the gametes together for 3-6 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [45] [14]. The brief co-incubation duration helps reduce exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by sperm, which can damage oocytes and impair embryo development [45].

- Washing and Culture: After the co-incubation period, wash the oocytes through several drops (e.g., 3-5 drops) of fresh medium (e.g., HTF or mHTF) to remove excess sperm and cellular debris [13] [14].

- Transfer the washed oocytes to a culture dish with pre-equilibrated KSOM-AA medium for overnight culture.

- Fertilization Check: The following morning, assess oocytes for successful fertilization, indicated by the formation of two-cell embryos.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Mouse IVF

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| PMSG (Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin) | Hormone for superovulation; stimulates follicular development. | - |

| hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) | Hormone to trigger ovulation; administered after PMSG. | - |

| Fertilization Medium (e.g., HTF, CARD) | Supports the process of fertilization during co-incubation. | CARD MEDIUM (Cosmo Bio, Cat# KYD-003-EX) [13] |

| Sperm Preincubation Medium (e.g., FERTIUP) | Medium used for sperm capacitation before insemination. | FERTIUP (Cosmo Bio, Cat# KYD-002-EX) [13] |

| Culture Medium (KSOM-AA) | Optimized medium for supporting embryonic development post-fertilization. | - |

| Mineral Oil (Embryo-Tested) | Light, sterile oil to overlay culture drops, preventing evaporation and pH shifts. | Sigma (Cat# M8410, M5310) [13] [14] |

| Wide-Bore Pipette Tips | For handling delicate oocytes and embryos without causing shear stress. | Rainin (HR-250W, 1000W) [14] |

This application note provides a detailed protocol for the post-fertilization culture of mouse embryos, specifically from the zygote stage to the 2-cell embryo stage, for use in timed embryo donor research. The period immediately following in vitro fertilization (IVF) is critical, as the embryonic genome begins to activate, and environmental stressors can significantly impact developmental potential. This document outlines standardized methodologies to maximize embryo viability and ensure reproducible results for research and drug development applications. The protocols are framed within the context of generating precisely timed embryos for transfer into pseudopregnant recipient females, a cornerstone technique in reproductive biology and genetic engineering.

Key Developmental Parameters & Culture Media Composition

Successful culture requires careful monitoring of specific morphokinetic parameters and the use of defined media sequences. The table below summarizes the key benchmarks for successful development during this critical window.

Table 1: Key Developmental Parameters from Zygote to 2-Cell Embryo

| Developmental Stage | Approximate Time Post-Insemination | Key Morphological Landmarks | Culture Medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zygote | 6 hours | Presence of two pronuclei (male and female) [24] | CARD MEDIUM or specialized fertilization medium [24] |

| Cleavage to 2-Cell | 24-48 hours [47] | Division into two distinct, symmetrical blastomeres [48] | mHTF or Potassium Simplex Optimized Medium [24] [49] |

| Exclusion of Parthenogenetic Oocytes | 6 hours post-insemination | Identification and removal of oocytes with only one pronucleus [24] | mHTF [24] |

The composition of the culture medium is a critical variable. Different media can selectively influence embryo development. For instance, studies have shown that culture media can affect the developmental speed of male and female embryos, potentially leading to a skewed sex ratio at birth, underscoring the medium's biochemical impact on the embryo [50].

Table 2: Common Culture Media and Their Applications

| Media Name | Primary Function | Key Components/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CARD MEDIUM | Fertilization and initial pre-incubation | Used for insemination and initial culture post-IVF; preparation varies for fresh, frozen, or transported sperm [24] |

| mHTF | Washing and post-fertilization culture | Used for washing oocytes post-insemination and subsequent culture of embryos [24] |

| Potassium Simplex Optimized Medium | In vitro culture to blastocyst stage | Used for culturing 1-celled and 2-celled embryos to blastocysts [49] |

| Sage Media | Commercial culture medium | Associated with faster male embryo development and a higher likelihood of male live births compared to G-TL media [50] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Post-IVF Processing and Identification of Fertilized Zygotes

This protocol begins immediately after the insemination period.

Materials:

- Fertilization dish with oocytes in CARD MEDIUM (from the IVF procedure) [24]

- Prepared washing dish with 4 drops of 80μL mHTF, covered with liquid paraffin [24]

- Pipette tips for handling oocytes/embryos

- Humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂ in air) [24]

Methodology: