Overcoming Embryonic Lethality in Hox Research: New Models and Methods for Limb Development Studies

This article addresses the central challenge of embryonic lethality in Hox gene research, which has historically limited the study of their essential functions in vertebrate limb development.

Overcoming Embryonic Lethality in Hox Research: New Models and Methods for Limb Development Studies

Abstract

This article addresses the central challenge of embryonic lethality in Hox gene research, which has historically limited the study of their essential functions in vertebrate limb development. We synthesize recent methodological advances—including conditional knockout systems, paralogous gene compensation, and alternative model organisms—that enable researchers to bypass early lethality and investigate Hox-specific limb patterning roles. For our target audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we provide a comprehensive framework covering foundational principles, practical applications, troubleshooting strategies, and cross-species validation techniques. By integrating cutting-edge findings from 2024-2025 studies, this resource aims to accelerate discovery in developmental biology and inform therapeutic approaches for congenital limb disorders.

Decoding Hox Gene Lethality: Why Essential Limb Genes Cause Embryonic Death

FAQs: Resolving the Core Paradox

Q1: What is the fundamental Hox specificity paradox? The paradox stems from the observation that Hox proteins, which are master regulators of embryonic patterning, possess highly similar DNA-binding homeodomains, yet they are able to regulate distinct sets of target genes to specify dramatically different anatomical structures along the body axis and in the limbs [1]. In vitro, most Hox proteins bind to similar high-affinity DNA sequences, which does not explain the specificity observed in vivo [1].

Q2: How is this paradox resolved for limb specification? Research indicates that Hox proteins achieve specificity in limb development by binding to clusters of low-affinity binding sites in genomic enhancer regions, rather than to the classic, isolated high-affinity sites [1]. These clusters are necessary for robust gene activation under physiological conditions. Furthermore, collaboration with protein cofactors like Pbx/Meis (TALE family) increases the stability and specificity of DNA binding [2].

Q3: How does the mechanism of Hox action in limb initiation differ from that in axial patterning? The key difference lies in the regulatory logic and the nature of the "Hox code."

| Feature | Axial Patterning | Limb Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Logic | Combinatorial & Overlapping [3] [4] | Modular & Sub-functionalized [5] [6] |

| Paralog Function | Extensive redundancy; loss of single genes often has subtle effects [3] [7]. | Higher specificity; loss of paralog groups can lead to the absence of entire limb segments [3] [6]. |

| Patterning Outcome | Anterior homeotic transformations (e.g., a vertebra assumes the identity of a more anterior one) [3] [4]. | Loss of structures (e.g., no zeugopod forms) or homeotic transformations between limb elements [6]. |

Q4: What are the primary technical challenges causing embryonic lethality in Hox research, and how can they be overcome? The high degree of functional redundancy among Hox paralogs necessitates the creation of complex multi-gene knockout models, which often result in embryonic lethality before limb phenotypes can be studied [3] [7]. The table below outlines major challenges and potential solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Embryonic Lethality in Hox Limb Development Research

| Challenge | Impact on Research | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Redundancy | Single-gene knockouts may show no phenotype, masking critical function [7]. | Generate conditional compound mutants (e.g., targeting all members of a paralog group like Hox10 or Hox11) using limb-specific Cre drivers [3] [6]. |

| Early Axial Defects | Constitutive knockout of critical Hox genes disrupts essential body plan formation, causing death before limb bud stage [4]. | Employ temporal and spatial control of gene deletion (e.g., using inducible Cre systems like Cre-ERT2) to inactivate genes after the critical axial patterning window [8]. |

| Pleiotropy | A Hox gene may function in multiple tissues (e.g., skeleton, muscle, tendon), complicating phenotype interpretation [3]. | Use tissue-specific promoters (e.g., Prx1-Cre for limb mesenchyme) to restrict gene deletion to the tissue of interest [3]. |

Technical Guides: Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Analyzing Hox Gene Function in Early Limb Initiation

Objective: To determine the requirement of a specific Hox gene (or paralog group) in the earliest stages of limb bud formation.

Background: Hox genes are upstream regulators of the key limb initiation gene Fgf10. For example, Tbx5 (upstream of Fgf10) is directly induced by Hox genes at the forelimb level [5].

Methodology:

- Model System: Mouse embryo (Mus musculus).

- Genetic Strategy: Cross a limb mesenchyme-specific Cre driver line (e.g., Prx1-Cre) with mice carrying floxed alleles of the target Hox gene(s). For redundancy, target multiple members of a paralog group (e.g., Hoxa9, Hoxb9, Hoxc9, Hoxd9).

- Experimental Timeline:

- E8.0-E8.5: Analyze mutant embryos for defects in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) within the somatopleure, a key early step in limb bud formation. Stain for basement membrane markers (laminin) and apical F-actin to assess epithelial integrity [5].

- E9.0-E9.5: Assess the expression of key limb initiation markers via in situ hybridization or immunofluorescence.

- Key Marker: Fgf10 expression in the lateral plate mesoderm. A failure to initiate or maintain Fgf10 expression indicates a breakdown in the limb initiation cascade [5].

- Upstream Markers: Tbx5 (forelimb) and Pitx1/Tbx4 (hindlimb) [5].

- Downstream Markers: Fgf8 in the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), which is induced by FGF10 signaling [5].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Compare the size and cellularity of the early limb bud in mutants versus controls. A severe failure in initiation will result in a truncated or absent limb bud.

Protocol: Dissecting the Hox-Shh Genetic Hierarchy in Limb Patterning

Objective: To establish the epistatic relationship between Hox genes and Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling in patterning the limb's anterior-posterior axis.

Background: Hox genes are critical for initiating and restricting Shh expression in the limb bud's Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA). For instance, Hox9 proteins promote posterior expression of Hand2, which inhibits the Shh repressor Gli3, thereby allowing Shh expression to initiate [3].

Methodology:

- Model System: Chick embryo (Gallus gallus) for precise gain/loss-of-function studies.

- Genetic Manipulations:

- Gain-of-Function: Electroporate expression constructs (e.g., Hoxd11, Hoxd13) into the anterior limb bud mesenchyme.

- Loss-of-Function: Use siRNA or CRISPR/Cas9 to knock down/out specific Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa9, Hoxb9, Hoxc9, Hoxd9) in the posterior limb bud.

- Key Readouts:

- Primary Marker: Analyze Shh expression via in situ hybridization. Ectopic anterior Shh leads to mirror-image digit patterns (e.g., 4-3-2-2-3-4). Loss of Shh results in a severe truncation of distal elements [3] [6].

- Intermediate Markers: Analyze expression of Hand2 (positive regulator) and Gli3 (repressor).

- Expected Outcomes:

- Hox Loss-of-Function: Loss of posterior Hox genes should lead to downregulation of Hand2, failure to repress Gli3, and consequent loss of Shh expression.

- Hox Gain-of-Function: Ectopic expression of "posterior" Hox genes in the anterior limb should induce Shh, resulting in double-posterior limbs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Hox Limb Development Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Floxed Hox Alleles | Enable tissue-specific, conditional knockout of Hox genes to bypass embryonic lethality. | Available from repositories like Jackson Laboratory. Essential for studying paralog groups (e.g., floxed Hoxa11, Hoxd11) [3] [6]. |

| Limb-Specific Cre Drivers | Restrict genetic recombination to limb mesenchyme, isolating Hox function in limbs. | Prx1-Cre (early limb bud mesenchyme); Msx2-Cre (distal limb and AER). |

| Inducible Cre Systems | Provide temporal control over gene deletion, allowing researchers to bypass early axial defects. | Cre-ERT2 (activated by tamoxifen). Administer tamoxifen at E9.0 to delete after limb bud initiation [8]. |

| Hox Expression Plasmids | For gain-of-function studies in model systems like chick. | RCAS vectors for chick electroporation (e.g., RCAS-Hoxd11) [6]. |

| In Situ Hybridization Probes | Detect spatial expression patterns of Hox genes and their targets. | Critical for markers like Fgf10, Shh, Tbx5, Hox genes themselves [5] [6]. |

| Low-Affinity Enhancer Reporters | Study the novel paradigm of Hox binding to clustered, low-affinity sites. | Clone identified enhancer sequences (e.g., from shavenbaby) upstream of a reporter gene (GFP/LacZ) to validate Hox regulation [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms of embryonic lethality in Hox gene research? Embryonic lethality in Hox research primarily stems from severe axial patterning defects and the failure of essential organ systems. Complete knockout of crucial Hox paralog groups can lead to a catastrophic loss of positional information, resulting in the absence of entire limb segments or major skeletal elements, which is incompatible with life. Furthermore, as Hox genes are often expressed in multiple systems, defects frequently co-occur in the gastro-intestinal tract, heart, central nervous system, and genito-urinary tract, causing multi-system organ failure [9] [3].

Q2: Why do limb defects often co-occur with other systemic issues in Hox mutants? Hox genes are master regulators of body patterning along the anterior-posterior axis, and their expression domains are not confined to the limb buds. A single Hox gene is often active in several developing tissue types. Therefore, an error in a Hox signaling cascade can manifest simultaneously in different organ systems that share a dependence on that gene's function for their correct patterning. This is why syndromes like Holt-Oram (TBX5 mutation) involve both forelimb abnormalities and cardiac defects [9].

Q3: How can I investigate a Hox gene with suspected functional redundancy? Due to significant functional redundancy among Hox paralogs, the effect of inactivating a single gene is often subtle or hidden by functioning genes in the same paralogous group. To uncover their function, you must create compound mutants that knock out multiple genes within the same paralogous group. For example, loss of a single Hox11 paralog may have little effect, whereas loss of the entire Hox11 paralogous group results in severe zeugopod (forearm/leg) mis-patterning [3] [7].

Q4: What controls the precise timing of Hox gene activation, and what happens if it's disrupted? The sequential activation of Hox genes, known as temporal collinearity, is a key mechanism. Genes at the 3' end of the cluster are expressed earlier and more anteriorly than 5' genes. This process is regulated by chromatin structure and epigenetic modifiers. Disruption of this timing is lethal. For instance, loss of maternal SMCHD1, an epigenetic regulator, leads to precocious Hox gene activation in the post-implantation embryo, causing severe posterior homeotic transformations of the axial skeleton [10] [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Embryonic Lethality

| Problem Area | Specific Challenge | Potential Solution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial Patterning | Complete knockout causes early lethality before limb phenotype analysis. | Use conditional knockout models (e.g., Prrx1-Cre for limb bud mesenchyme) to delete the gene of interest specifically in limb tissues. | Verify Cre activity with a reporter line (e.g., Rosa26-tdTomato). Ensure the deletion occurs at the correct developmental stage (e.g., E9.5-10.5 in mice) [12] [3]. |

| Functional Redundancy | No observable phenotype in single-gene knockout. | Generate compound paralogous mutants (e.g., Hoxa11-/-;Hoxd11-/-). | Breeding can be complex and time-consuming. Phenotypes may be more severe than expected, potentially still leading to lethality [3] [7]. |

| Epigenetic Regulation | Disrupted Hox gene expression timing (precocious activation). | Investigate maternal effect genes and Polycomb group proteins. Analyze histone marks (H3K27me3, H2AK119ub) at Hox loci in mutants. | The pre-implantation chromatin state is critical. Maternal-effect mutations (e.g., in SMCHD1) can cause patterning defects in genetically wild-type embryos [11]. |

| Tissue Integration | Limb elements form but fail to integrate into a functional musculoskeletal unit. | Analyze the development of muscle, tendon, and bone connections. Use muscle-less limb models (e.g., Pax3 mutants) to dissect autonomous vs. non-autonomous patterning. | Early patterning may be normal, but later integration requires tissue-tissue communication. Examine tendon primordia and muscle connective tissue [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Assessing Hox Gene Expression via Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) in Mouse Limb Buds

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to analyze gene expression in developing mouse embryos [12].

- Tissue Collection: Dissect mouse embryos at the desired stage (e.g., E10.5-E12.5 for limb patterning) in cold, sterile PBS. Remove amniotic membranes carefully.

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for several hours to overnight at 4°C.

- Probe Synthesis: Transcribe digoxygenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNA probes from cDNA clones of the target Hox gene (e.g., Hoxd13). Use sense probes as negative controls.

- Hybridization: Rehydrate fixed embryos and pre-hybridize in a suitable buffer. Incubate with the DIG-labeled probe overnight at 65-70°C.

- Washing and Detection: Perform stringent washes to remove unbound probe. Incubate with an anti-DIG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. Develop the color reaction using NBT/BCIP.

- Imaging: Image the stained embryos using a stereomicroscope to document the spatial expression pattern of the Hox gene.

Protocol 2: Primary Limb Bud Cell Culture for Molecular Analysis

This protocol allows for in vitro manipulation and analysis of limb bud cells [12].

- Dissection: Isolate E11.5 mouse embryos. Using fine scissors and forceps under a stereoscopic microscope, dissect the limb bud tissue and place it in sterile PBS.

- Digestion: Digest the pooled limb bud tissue with 0.25% trypsin for 5 minutes at 37°C to create a single-cell suspension.

- Culture Establishment: Centrifuge the cell suspension, resuspend the pellet in complete medium (e.g., low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin), and seed the cells in culture dishes.

- Experimental Application: Culture cells at 37°C with 5% CO2. Once adhered, cells can be treated with signaling molecules (e.g., Retinoic Acid, FGFs) or transfected with siRNAs/expression vectors for functional studies. Cells can be harvested for downstream qPCR or immunoblotting analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function / Application in Hox Limb Development Research |

|---|---|

| Cre-lox System (e.g., Prrx1-Cre) | Enables tissue-specific gene knockout in limb bud mesenchyme, allowing researchers to bypass embryonic lethality caused by systemic gene deletion [12]. |

| Fluoxed-Hnrnpk Mice | A conditional mouse model used to study the role of the essential chromatin regulator hnRNPK in limb bud development, revealing its role in 3D chromatin architecture [12]. |

| Digoxygenin (DIG)-labeled RNA Probes | Used for Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization to precisely visualize the spatial and temporal expression patterns of Hox genes and other patterning signals (e.g., Shh, Fgf8) in the embryo [12]. |

| Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) | Key signaling molecules; FGF10 from mesenchyme and FGF8 from the Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) maintain a positive feedback loop essential for limb bud outgrowth. Used in gain-of-function experiments [9] [13]. |

| Anti-hnRNPK Antibody | Used in immunoblotting to confirm the successful ablation of the hnRNPK protein in knockout models, validating the molecular phenotype [12]. |

| T-Box Gene Constructs (e.g., Tbx5) | Used in mis-expression experiments in chick embryos to demonstrate the role of Tbx5 in initiating forelimb identity and outgrowth, linking it to human syndromes like Holt-Oram [9]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

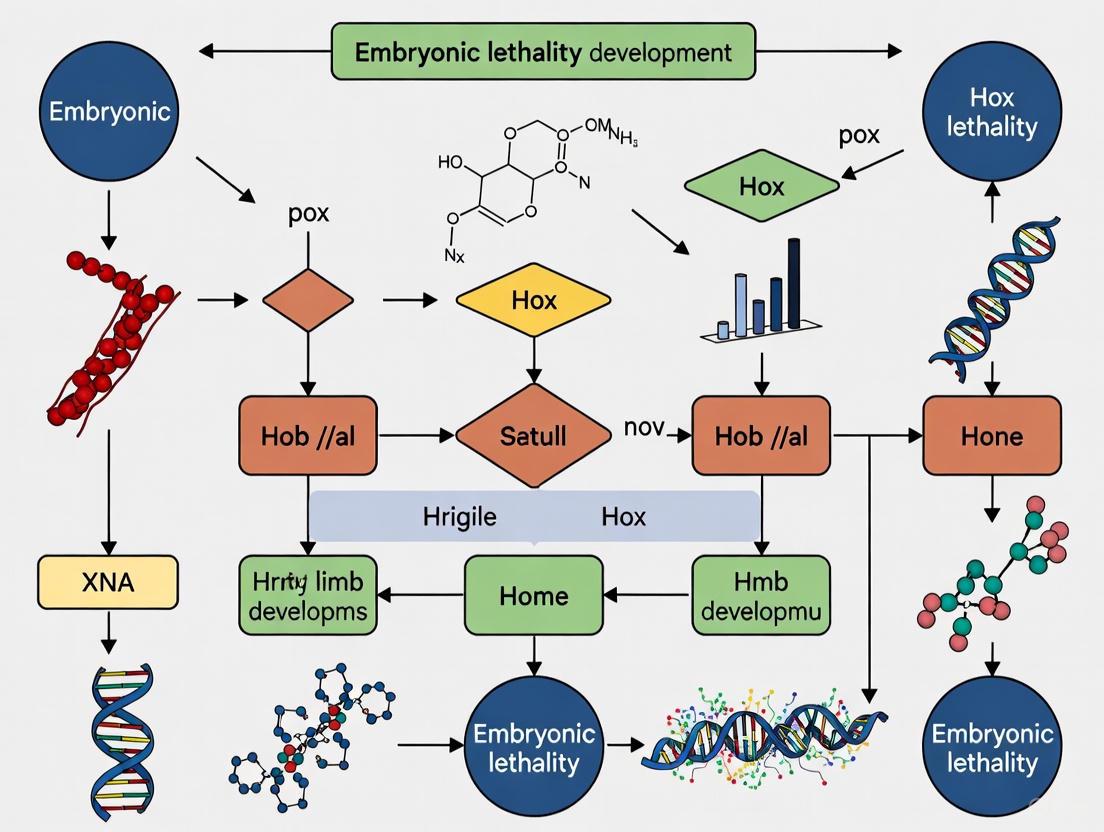

Figure 1: Hox-Tbx-FGF Signaling Axis in Limb Initiation. This pathway illustrates the core genetic interactions that initiate limb bud outgrowth, a process whose failure can lead to severe deformities like limblessness.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating Hox Lethality. A logical decision tree for troubleshooting the root causes of embryonic lethality in Hox gene research.

Functional Redundancy and Compensation Within Hox Paralogous Groups

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Hox Gene Redundancy

Q1: Why don't single Hox gene knockouts always show a developmental phenotype? A common explanation is functional redundancy within paralogous groups. When genes share overlapping functions, the loss of one can be compensated for by its paralogs, masking potential anomalies in single mutants. This compensation can occur via other Hox genes expressing similar proteins that fulfill the missing function [14].

Q2: How can I experimentally test if two Hox genes are functionally redundant? The most direct method is to generate compound mutant mice, where multiple genes from the same paralog group are inactivated. If the double or triple mutants show more severe, or even lethal, phenotypes compared to single mutants, it provides strong evidence for functional redundancy [14]. An alternative, more precise approach is a paralogous gene swap, where the coding sequence of one Hox gene is replaced by that of its paralog. The functional outcome of this swap can then be rigorously assessed [15].

Q3: A compound mutant of my Hox genes of interest is embryonically lethal. How can I study their function in later developmental stages, like limb patterning? Embryonic lethality is a major challenge. Strategies to overcome it include using tissue-specific or inducible Cre-loxP systems to delete the genes in a spatially and temporally controlled manner, thus bypassing early essential functions. Another approach is to perform detailed analyses of the embryonic phenotype prior to the lethal stage to identify the primary defects causing lethality [14].

Q4: What is the difference between complete and incomplete functional redundancy? Complete redundancy implies that paralogous genes can fully substitute for each other's functions, so single mutants show no phenotype. Incomplete redundancy means the overlap is partial; paralogs share some functions, but each has also acquired unique, non-overlapping roles. This is often revealed by more severe phenotypes in compound mutants and can be confirmed by fitness assays in competitive environments [15].

Q5: If two Hox proteins are highly similar in sequence, does that guarantee they are functionally redundant? Not necessarily. While sequence similarity often suggests functional overlap, even minor differences can be critical. Proteins can diverge in their interactions with specific co-factors, their precise DNA-binding preferences, or their expression patterns. Functional equivalence must be validated through rigorous in vivo experiments, as sequence analysis alone can be misleading [15] [16].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Interpreting Negative Data from Single-Gene Knockouts

- Problem: A Hox gene knockout shows no obvious phenotype, but you suspect it has an important function masked by redundancy.

- Solution: Generate higher-order mutants. The guiding principle is that mutating multiple genes within a paralogous group is often required to reveal their collective function [14].

- Recommended Experiment: Cross single mutant lines to create double or triple mutants. For example, while

Hoxb5single mutants are viable,Hoxa5;Hoxb5compound mutants display aggravated lung phenotypes and neonatal lethality, uncovering roles forHoxb5that were hidden byHoxa5compensation [14].

Challenge 2: Demonstrating Direct Functional Equivalence

- Problem: You want to prove that two Hox paralogs can biochemically replace one another, not just that their functions overlap.

- Solution: Perform a paralogous gene replacement (knock-in) experiment.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Gene Targeting: Use CRISPR/Cas9 or traditional homologous recombination in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells to replace the coding region of Gene A (e.g.,

Hoxa1) with the coding region of its paralog, Gene B (e.g.,Hoxb1). Ensure the endogenous regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) of Gene A are left intact so the swapped gene is expressed in the correct spatiotemporal pattern [15]. - Phenotypic Analysis: Thoroughly characterize the resulting "swap" mice (

Hoxa1^(B1/B1)) for developmental defects. Initial assessment may involve standard laboratory phenotyping (histology, molecular markers). - Fitness Assessment (Critical Step): House the swap mice and controls in semi-natural enclosures (Organismal Performance Assays). This competitive environment imposes ecological pressures and provides a sensitive measure of Darwinian fitness (reproductive success). A deficiency in offspring output from swap mice, as seen in the

Hoxa1B1model, reveals functional differences that are invisible in standard lab conditions [15].

- Gene Targeting: Use CRISPR/Cas9 or traditional homologous recombination in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells to replace the coding region of Gene A (e.g.,

Challenge 3: Overcoming Embryonic Lethality in Compound Mutants

- Problem: The compound mutant dies in utero before the developmental stage you wish to study (e.g., limb formation).

- Solution: Implement conditional mutagenesis.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Generate Floxed Alleles: Create mutant mouse lines where the Hox genes of interest are flanked by

loxPsites (Hoxa5^(fl/fl),Hoxb5^(fl/fl)). - Select a Tissue-Specific Cre Driver: Choose a Cre recombinase line that expresses in your tissue of interest at the desired time. For limb development, a

Prx1-Credriver can target the early limb bud mesenchyme [9]. - Cross Breeding: Cross the compound floxed allele mouse with the Cre driver line to generate progeny that lack the Hox genes specifically in the limb tissue, thereby circumventing early embryonic lethality.

- Generate Floxed Alleles: Create mutant mouse lines where the Hox genes of interest are flanked by

Quantitative Data on Hox Paralog Redundancy

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from research on Hox paralog redundancy.

Table 1: Phenotypic Severity in Hox5 Paralog Mutants during Lung Development [14]

| Genotype | Viability | Key Lung Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|

Hoxa5⁻/⁻ |

High neonatal mortality | Tracheal and lung dysmorphogenesis, goblet cell metaplasia, emphysema-like air space enlargement in survivors |

Hoxb5⁻/⁻ |

Viable | No overt lung phenotype reported in single mutants |

Hoxa5⁻/⁻;Hoxb5⁻/⁻ |

Neonatal lethal | Aggravated lung phenotype: severe defects in branching morphogenesis, goblet cell specification, and postnatal air space structure |

Table 2: Fitness Consequences of Hoxa1-Hoxb1 Paralog Swapping in Competitive Environments [15]

| Genotype | Laboratory Cage Phenotype | Relative Fitness in Semi-Natural Enclosures | Offspring Production vs. Controls |

|---|---|---|---|

Hoxa1^(B1/B1) (HoxB1 protein from Hoxa1 locus) |

No discernible embryonic or physiological phenotype | Reduced | Homozygous founders produced ~78% as many offspring; a 22% deficiency of heterozygous offspring was also observed. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol for Analyzing Compound Mutants

This workflow is fundamental for uncovering redundant functions.

Pathway Diagram: Regulatory Mechanisms of Hox Gene Expression

Hox gene regulation is a multi-layered process crucial for their function and redundancy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Hox Redundancy and Compensation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Mutant Mice | To reveal shared functions by removing genetic backup. | Hoxa5;Hoxb5 mutants revealed partial redundancy in lung morphogenesis [14]. |

| Paralog Gene-Swap Alleles | To test if paralog proteins are functionally interchangeable in vivo. | Hoxa1^(B1/B1) allele showed incomplete redundancy via fitness assays [15]. |

| Conditional (Floxed) Alleles | To bypass embryonic lethality and study gene function in specific tissues/times. | Using Prx1-Cre to delete floxed Hox genes specifically in the limb bud [9]. |

| Organismal Performance Assay (OPA) | A semi-natural enclosure to measure Darwinian fitness and detect subtle deficits. | Revealed a ~22% reproductive deficiency in Hoxa1^(B1/B1) mice [15]. |

| Histone Modification ChIP | To map epigenetic landscapes at Hox loci (e.g., H3K27ac for enhancers, H3K27me3 for repression). | Identifying active enhancers within Hox clusters that respond to signaling cues [17] [10]. |

A central challenge in developmental biology is that disrupting key regulatory genes, such as the Hox genes, often leads to embryonic lethality, halting research before their full functions can be understood. These genes provide positional information along the body axes, orchestrating the formation of limbs and other structures. When these processes fail, development cannot proceed. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers navigating these complexities, offering troubleshooting advice for experiments aimed at uncovering the spatiotemporal dynamics of gene expression from embryonic development through to adult maintenance.

FAQs: Addressing Core Research Challenges

Q1: What experimental strategies can bypass embryonic lethality to study Hox gene function in limb development? The most effective strategy is to use conditional and inducible knockout models (e.g., Cre-lox systems) that allow gene deletion in specific tissues or at specific time points, thus avoiding global embryonic lethality. Furthermore, advanced spatial transcriptomics can be applied to wild-type embryos to map the precise expression domains of Hox genes and their targets without any genetic perturbation, providing a foundational atlas of their roles [18] [19].

Q2: How can I confirm that a limb phenotype results from a patterning defect rather than a growth defect? A patterning defect alters the identity of structures (e.g., a homeotic transformation where one limb element resembles another), while a growth defect simply changes the size. To distinguish them:

- Molecular Analysis: Perform in-situ hybridization for key marker genes. Patterning defects show altered spatial expression of genes like Tbx5 (forelimb) or Tbx4/Pitx1 (hindlimb) and Hox genes themselves [9] [19].

- Morphological Analysis: Compare the skeletal pattern to established fate maps. The loss of an entire segment (e.g., zeugopod) indicates a patterning failure, as seen when specific Hox paralog groups are lost [3].

Q3: What are the best practices for validating spatial transcriptomics data? Spatial transcriptomics generates vast datasets that require rigorous validation.

- Orthogonal Validation: Use in-situ hybridization (ISH) or immunohistochemistry (IHC) on consecutive tissue sections to confirm the expression patterns of key genes identified in your analysis [20].

- Data Integration: Correlate spatial data with single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from the same tissue. Deconvoluting spatial spots using scRNA-seq clusters allows for higher-resolution, spatially aware cell state annotation [20] [18].

- Leverage Public Resources: Utilize open-access interactive viewers provided with published spatial atlases to compare your findings with established datasets [20].

Q4: How does the function of Hox genes differ between embryonic limb patterning and adult tissue maintenance? In the embryo, Hox genes act as master regulators of patterning, defining the identity of limb segments (stylopod, zeugopod, autopod) in a non-overlapping manner. Their expression is high and spatially restricted [3]. In adult tissues, their role is less defined but often shifts to maintaining tissue homeostasis and regulating regeneration. Misexpression in adults is frequently linked to pathologies like cancer, suggesting a role in controlling cell proliferation and identity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Investigating Redundant Hox Gene Functions

Problem: No limb phenotype is observed in a single Hox gene knockout, despite known importance in limb development.

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Redundancy | Other members of the same paralog group compensate for the lost gene's function. | Generate compound mutants targeting all members of a paralogous group (e.g., Hoxa11, Hoxc11, Hoxd11) [3]. |

| Insufficient Analysis | The phenotype may be subtle, affecting pattern rather than presence/absence. | Perform detailed skeletal staining and molecular profiling (e.g., RNA-seq) on limb buds to identify subtle patterning shifts. |

| Incorrect Model | The gene's primary function is in a different tissue (e.g., connective tissue) that secondarily affects the skeleton. | Analyze Hox expression in non-skeletal tissues like muscle connective tissue and tendons, which are known to pattern the entire musculoskeletal system [3]. |

Guide: Resolving Inconsistent Spatial Transcriptomics Results

Problem: Spatial transcriptomics data shows unexpected or noisy gene expression patterns.

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Capture Efficiency | Poor tissue preservation or protocol optimization leads to sparse data. | - Optimize tissue fixation and permeabilization times.- Use fresh-frozen tissues embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound. |

| Incorrect Region of Interest (ROI) Annotation | Tissue structures are misidentified, leading to incorrect biological interpretation. | - Collaborate with a developmental histologist for accurate anatomical annotation.- Use established markers from public atlases to define ROIs [20]. |

| Cell Type contamination | A single spot captures RNA from multiple cell types, blurring distinct signals. | - Deconvolute spatial data with a paired scRNA-seq reference to infer the proportion of cell types within each spot [20] [18]. |

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Hox-Driven Limb Patterning Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the simplified genetic hierarchy governing limb positioning and patterning, integrating instructions from Hox genes.

Spatiotemporal Transcriptomics Workflow

This workflow outlines the key steps for creating a high-resolution map of gene expression in a developing embryo, a method crucial for studying embryonic lethality without perturbation.

Data Presentation: Hox Gene Function in Limb Development

Hox Gene Paralogs and Limb Patterning Phenotypes

Table 1: Key Hox paralog groups and their documented roles in limb segmentation, based on loss-of-function studies in model organisms.

| Hox Paralog Group | Principal Limb Segment Role | Phenotype of Combined Loss-of-Function | Human Syndrome Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox 9 | Anterior-Posterior Patterning Initiation | Failure to initiate Sonic hedgehog (Shh) expression; loss of AP polarity [3] | Not specified in results |

| Hox 10 | Stylopod (e.g., Humerus/Femur) | Severe mis-patterning of the proximal stylopod segment [3] | Not specified in results |

| Hox 11 | Zeugopod (e.g., Radius/Ulna) | Severe mis-patterning of the medial zeugopod segment [3] | Not specified in results |

| Hox 13 | Autopod (Hand/Foot) | Complete loss of distal autopod skeletal elements [3] | Not specified in results |

| Hox 5 | Forelimb Positioning & Identity | Altered Tbx5 expression; forelimb identity defects [19] | Holt-Oram Syndrome (TBX5 mutations) [9] |

Quantitative Output of Spatial Transcriptomics Studies

Table 2: Representative data output metrics from recent spatiotemporal transcriptomic studies of embryonic development, highlighting the scale of data generated.

| Parameter | Mouse Embryo (Slide-seq) [18] | Developing Human Heart [20] |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Stage | Embryonic day (E) 8.5 - 9.5 | Post-conceptional weeks (PCW) 5.5 - 14 |

| Spatial Technology | Slide-seq | 10x Genomics Visium / ISS |

| Total Spots / Cells | 533,116 beads | 69,114 tissue spots; 76,991 single cells |

| Median Metrics per Spot/Cell | 1,798 transcripts; 1,224 genes | Not specified |

| Key Output | 3D virtual embryo reconstruction (sc3D) | 72 fine-grained cell states mapped to niches |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and tools for investigating Hox gene function and spatiotemporal expression dynamics.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Conditional Knockout Mice (Cre-lox) | Enables tissue-specific or time-specific gene deletion. | Circumventing embryonic lethality to study Hox function in limb mesenchyme [3]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Suppresses the function of a specific Hox gene and its paralogs by sequestering co-factors [19]. | Rapidly testing Hox gene requirement in specific embryonic fields (e.g., chick electroporation). |

| Spatial Transcriptomics (10x Visium, Slide-seq) | Provides genome-wide expression data within native tissue context. | Mapping the precise spatial niches of Hox gene expression and their downstream targets [20] [18]. |

| sc3D Visualization Software | Reconstructs and explores 3D "virtual embryos" from 2D spatial data. | Quantifying gene expression gradients along embryonic axes and analyzing mutant phenotypes [18]. |

| Tbx5/LacZ Reporter Line | Visualizes the extent and location of the forelimb field. | Assessing if Hox gene manipulations shift the limb field anteriorly or posteriorly [19]. |

Bypassing Lethality: Advanced Genetic and Model System Approaches

Conditional and Inducible Knockout Systems for Tissue-Specific Hox Analysis

In the study of Hox genes, which are crucial developmental regulators for limb and skeletal patterning, a significant challenge is embryonic lethality. Constitutive knockout of many essential Hox genes often results in non-viable embryos, preventing researchers from studying their functions in later developmental stages or in specific tissues like the limb bud [21] [22]. Conditional and inducible knockout systems provide a powerful solution to this problem by enabling spatial and temporal control over gene inactivation [21] [23]. This allows for the analysis of gene function in specific tissues, such as the limb, at desired time points, thereby circumventing early embryonic death and facilitating detailed functional studies [22]. This technical support center is designed to guide researchers in effectively utilizing these systems to advance Hox gene research.

Core System Components

The most common and effective systems for conditional gene knockout in rodent models rely on site-specific recombinases and drug-inducible elements [21].

Recombinase Systems

Recombinase systems enable stable induction or suppression of gene expression in a particular developmental stage or specific cell type [21].

- Cre-loxP System: This is the most commonly utilized system [24]. The Cre recombinase enzyme recognizes specific 34-bp DNA sequences called loxP sites and catalyzes recombination between them [21] [23]. The most common usage is Cre-mediated excision of loxP-flanked ("floxed") portions of a gene, leading to a conditional knock-out [21].

- Other Recombinase Systems:

Inducible Systems

Inducible systems provide temporal control over when gene recombination occurs.

- Tetracycline (Tet)-Responsive Systems: These are the most common drug-inducible systems in rodent models. There are both tet-ON and tet-OFF systems, so that administration of tetracycline or its derivatives to animals can be used to either activate or repress gene expression, respectively [21].

- Cre-ER Tamoxifen-Inducible System: This is a very successful strategy based on a fusion between Cre and a mutant version of the estrogen-receptor binding domain (Cre-ER). In the uninduced state, Cre-ER remains sequestered in the cytoplasm. When the ligand 4-hydroxytamoxifen is added, Cre-ER enters the nucleus and catalyzes Cre-mediated recombination [21].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow of these core components in a conditional knockout experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key reagents and materials essential for conducting conditional and inducible knockout experiments in the context of Hox research.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Application in Hox Research |

|---|---|---|

| Floxed Allele Mouse Model | Carries the target gene (e.g., a Hox gene) with critical exons flanked by loxP sites. The gene functions normally until Cre is introduced [23]. | A floxed Hoxa13 allele allows study of its role in autopod (limb bud) development without early embryonic lethality [3] [25]. |

| Tissue-Specific Cre Driver Mouse | Expresses Cre recombinase under the control of a tissue-specific promoter. Restricts gene knockout to a defined cell type or tissue [21] [22]. | Prrx1-Cre drives expression in limb bud mesenchyme, enabling targeted Hox gene deletion specifically in the developing limb [12]. |

| Inducible Cre System (e.g., Cre-ER) | Allows temporal control of recombination. The Cre-ER fusion protein only enters the nucleus to catalyze recombination upon tamoxifen administration [21]. | Used to inactivate a Hox gene at a specific stage of limb bud development (e.g., E11.5) to dissect its role in early patterning vs. later differentiation [21]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Genome editing technology used to generate floxed alleles or other genetic modifications. Can be used to insert loxP sites flanking genomic regions of interest [26]. | Enables rapid creation of novel conditional alleles for Hox genes or their regulatory elements in mouse embryonic stem cells or embryos [26]. |

| 4-Hydroxytamoxifen | The ligand used to induce nuclear translocation of Cre-ER, providing precise temporal control over the onset of gene knockout [21]. | Administered to pregnant dams at a specific embryonic day to activate Cre and delete the floxed Hox gene in the embryos at a precise time point [12]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Addressing Common Challenges

Q1: My floxed mouse model shows a phenotype even before crossing to a Cre driver. What could be wrong? A1: This can occur if the insertion of the loxP sites inadvertently disrupts the gene's function, promoter, or regulatory elements—a phenomenon known as a "neomorphic allele." To troubleshoot:

- Verify Floxed Allele Integrity: Use Southern blotting and long-range PCR to confirm that the loxP sites are correctly inserted and that no unintended mutations were introduced during the targeting process [23].

- Check for Splicing Disruption: Ensure that the loxP sites, often placed in introns, do not interfere with mRNA splicing. Perform RT-PCR to analyze transcript variants from the floxed allele [22].

- Confirm Protein Expression: Use immunoblotting to check if a functional protein is still produced from the floxed allele before Cre recombination [12].

Q2: I see mosaic or incomplete gene deletion in my target tissue after using an inducible Cre system. How can I improve efficiency? A2: Mosaicism is a common challenge with inducible systems and can be addressed by optimizing the induction protocol.

- Optimize Tamoxifen Dose and Timing: The efficiency of Cre-ER induction is highly dependent on the concentration and bioavailability of tamoxifen. Perform a dose-response curve and vary the timing of administration to find the optimal window for your specific tissue [21].

- Use a Sensitive Reporter Allele: Cross your mice to a fluorescent reporter strain (e.g., Rosa26-tdTomato). This allows you to visually map the precise pattern and efficiency of Cre activity within the target tissue and identify the optimal induction window [12].

- Consider Cre Driver Strength: The promoter driving the Cre-ER can also affect efficiency. A stronger or more specific promoter might be necessary for robust, uniform recombination [22].

Q3: I observe an unexpected phenotype in a non-target tissue. What are the potential causes? A3: Ectopic or "leaky" Cre expression is a frequent cause of off-target effects.

- Characterize Cre Expression Pattern: The Cre driver line may have uncharacterized or low-level expression in tissues other than your target. Perform rigorous histology or RNA in situ hybridization to validate the true expression pattern of your specific Cre line [22].

- Check for Germline Recombination: If the phenotype is observed in all offspring, it might be due to Cre activity in the germline of one of the parents, leading to a constitutive knockout. Breed your mice carefully to ensure that the knockout is only generated in the experimental animals [23].

- Rule Up Secondary Effects: In complex systems like limb development, knocking out a gene in one tissue can have non-autonomous effects on neighboring tissues. Use additional assays to confirm that the phenotype is cell-autonomous [3].

Q4: The gene I am studying is essential for cell viability. How can I create a conditional knockout without losing my cell population? A4: This requires careful control over the timing and analysis.

- Use a Tightly Controlled Inducible System: Systems like Cre-ER provide the best temporal control. You can activate knockout in a synchronized manner and analyze the cells shortly after induction to capture primary effects before cell death [26].

- Analyze Early Time Points: Focus your initial phenotypic analysis on early time points immediately following gene deletion to identify the primary consequences of gene loss before secondary compensatory mechanisms or cell death occur [12].

- Employ ex vivo Cultures: Isolate and culture primary cells (e.g., limb bud mesenchymal cells) from your conditional model. This allows for precise pharmacological control and high-efficiency induction of knockout in a defined environment [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Limb Bud-Specific Hox Gene Knockout

This protocol outlines the methodology for generating and analyzing a limb bud-specific conditional knockout of a Hox gene, based on established techniques [12].

Generation of the Conditional Mouse Model

Step 1: Create the Floxed Hox Allele

- Strategy: Using CRISPR/Cas9 or ESC-based homologous recombination, insert loxP sites into introns flanking one or more critical exons of the target Hox gene (e.g., exons 4-7 of Hnrnpk as shown in one study) [12] [23] [26]. A puromycin drug resistance cassette, itself flanked by FRT sites, is often included for selection and later removed with Flp recombinase.

- Validation: Perform extensive molecular characterization on targeted ES cell clones using Southern blotting and PCR to confirm correct targeting and single-copy integration of the loxP sites [23].

Step 2: Select the Cre Driver

- For limb bud-specific deletion, use a Cre driver line expressed in limb mesenchyme, such as Prrx1-Cre [12].

Step 3: Breed Mice to Generate Experimental Animals

- Cross mice homozygous for the floxed Hox allele with mice heterozygous for the Prrx1-Cre transgene.

- Genotyping: Use PCR on genomic DNA from tail or embryo biopsies to identify embryos with the following genotype: Hoxflox/flox; Prrx1-Cre+/–. These are the conditional knockouts (CKO). Control littermates (e.g., Hoxflox/flox or Hoxflox/+; Prrx1-Cre+/–) should be used for comparison [12].

Phenotypic Analysis of Limb Defects

Step 1: Morphological Analysis

- Harvest embryos at various stages (e.g., E11.5, E13.5, E15.5). Document gross limb morphology under a dissection microscope. CKO embryos may exhibit severe deformities such as truncated or absent limbs [12].

Step 2: Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH)

- Purpose: To analyze the expression of key genes involved in the three limb axes.

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% PFA.

- Probes: Use digoxygenin-labeled antisense RNA probes for genes like:

- Procedure: Follow standard WISH protocols, including hybridization, washing, and colorimetric detection [12].

Step 3: Primary Limb Bud Cell Culture

- Isolation: Dissect limb buds from E11.5 embryos. Remove amniotic membranes and digest tissue with 0.25% trypsin to create a single-cell suspension [12].

- Culture: Seed cells in complete medium (e.g., low-glucose DMEM with 10% FBS) [12].

- Downstream Analysis: Use these cells for qPCR, immunoblotting, or chromatin conformation assays to investigate molecular mechanisms.

Molecular Mechanism Investigation

Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Extract total RNA from control and CKO limb buds or cultured cells using TRIZOL reagent.

- Synthesize cDNA and perform qPCR with primers for Hox target genes and limb patterning genes (e.g., Shh, Fgf10, Bmp2). Use Actb or Gapdh as an internal control for normalization [12].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and 3D Genome Architecture:

- As studies show Hox proteins and associated factors like hnRNPK can regulate 3D chromatin structure, this can be a key assay [12].

- Crosslink proteins and DNA from limb bud cells. Sonicate chromatin and immunoprecipitate using antibodies against proteins of interest (e.g., CTCF, H3K27ac).

- Analyze enrichment at specific genomic regions (e.g., TAD boundaries, enhancer-promoter regions) via qPCR or sequencing.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in this protocol.

Table 1: Quantitative Data from a Limb Bud Conditional Knockout Study

This table summarizes example findings from a study where Hnrnpk was conditionally ablated in the mouse limb bud, illustrating potential outcomes for a Hox gene study [12].

| Analysis Method | Parameter Measured | Control Embryos | Conditional Knockout (CKO) Embryos | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Forelimb Phenotype | Normal development | Limbless | Hnrnpk is essential for initiation/outgrowth of forelimbs. |

| Morphology | Hindlimb Phenotype | Normal development | Severe deformities | Hindlimb development is highly disrupted but not entirely blocked. |

| qPCR | Shh Transcript Level | Normal expression | Decreased | Disruption of the anterior-posterior (A/P) signaling axis. |

| qPCR | Fgf10 Transcript Level | Normal expression | Decreased | Disruption of the proximal-distal (P/D) signaling axis. |

| Chromatin Analysis | TAD Boundary Strength | Intact CTCF binding | Weakened binding, loose TADs | Protein is required for maintaining 3D chromatin architecture. |

Table 2: Comparison of Conditional Knockout Model Generation Technologies

| Technology | Typical Timeline | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC/Homologous Recombination | ~46 weeks [23] | Gold standard for complex alleles; allows extensive pre-validation via Southern blotting; high fidelity for inserting large sequences like loxP sites [23]. | Time-consuming; labor-intensive; requires expertise in ESC culture [23] [26]. | Projects requiring high-complexity conditional alleles and where timeline is flexible. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 in Zygotes | ~24 weeks (constitutive) [23] | Faster; simpler; avoids ESC culture; highly efficient for generating deletions [23] [26]. | Higher risk of off-target effects; less efficient for precise, large insertions (loxP sites) compared to deletions [23]. | Rapid generation of constitutive knockouts or simpler conditional models. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 in mESCs | Varies | Simplicity and high efficiency; combines the precision of CRISPR with the validation advantages of ESCs; suitable for sequential or simultaneous loxP insertion [26]. | Still requires ESC culture and blastocyst injection. | A modern hybrid approach for efficient conditional knockout generation in cells. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Editing Efficiency

Problem: Your CRISPR-Cas9 system is not efficiently editing the target site.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Relevant Organism |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal gRNA design | Verify gRNA targets a unique genomic sequence with optimal length. Use online design tools with prediction algorithms. [27] | All organisms |

| Inefficient delivery method | Optimize delivery for specific cell types: electroporation, lipofection, or viral vectors. [27] | All organisms |

| Inadequate Cas9/gRNA expression | Confirm promoter suitability for your cell type. Use codon-optimized Cas9 and verify quality of DNA/mRNA. [27] | All organisms |

Guide 2: Managing Off-Target Effects

Problem: Unintended mutations at sites with sequence similarity to your gRNA.

| Strategy | Implementation | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-specificity gRNA design | Use tools to predict and minimize off-target sites. [27] | Critical for long-term studies |

| High-fidelity Cas9 variants | Employ engineered Cas9 enzymes with reduced off-target cleavage. [27] | May reduce on-target efficiency |

| Computational specificity check | Perform Axolotl Genome Blast to ensure gRNA sequences have a single hit to the intended locus. [28] | Essential for non-model organisms |

Guide 3: Overcoming Phenotypic Challenges like Embryonic Lethality

Problem: Mutations cause embryonic lethality, precluding study of gene function in later development (e.g., limb formation).

| Strategy | Application Example | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Use of conditional/inducible systems | Not detailed in search results, but recommended best practice. | Controls timing of mutation |

| Study of paralogous genes | In zebrafish, study of hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters revealed functional redundancy. [29] |

Can circumvent lethality |

| Alternative model organisms | Use axolotls or zebrafish for regeneration studies; they can bypass early lethality seen in mice. [28] [29] | Enables analysis of later processes |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the critical steps for ensuring I am targeting the correct gene in a non-model organism like the axolotl?

A: The process is methodical and relies heavily on bioinformatics:

- Retrieve and Verify Sequence: Data mine transcriptomes to find the target gene's complete Open Reading Frame (ORF). [28]

- Confirm Annotation: Use NCBI BLASTx to verify the sequence is the correct ortholog. Look for a very low E-value (<1E-20), high query coverage (>80%), and high identity (>75%). [28]

- Map the Locus: Compare the ORF against the organism's genome (e.g., the axolotl genome browser at Sal-Site) to identify exons, introns, and functional motifs. [28]

Q2: How can I screen for successfully edited animals (Crispants) when working with a long-generation organism?

A: For organisms like the axolotl, which can take 9 months to reach adulthood, a robust screening protocol is essential. [28]

- Molecular Analysis: Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR on the target region. Analyze the PCR products for indels (insertions/deletions) caused by CRISPR. This allows you to identify animals carrying mutations before they reach adulthood. [28]

- Phenotypic Screening: In parallel, rear the animals and look for the intended phenotypic consequences of the gene edit. [28]

Q3: My Hox gene mutation did not yield an expected limb phenotype. What could explain this?

A: Several factors could be at play, which is a key challenge in Hox limb development research:

- Functional Redundancy: Related genes may compensate for the loss of a single Hox gene. In zebrafish, deletions of individual

hoxaa,hoxab, orhoxdaclusters showed mild effects, but the triple mutant revealed severe pectoral fin shortening, demonstrating powerful redundancy. [29] - Latent Potential: The genetic program for more complex limb structures may be present but silent. One study found that simple genetic perturbations in zebrafish could activate a latent, limb-like patterning ability in fins, requiring Hox11 function. [30]

- Alternative Isoforms: The mutation may not affect all protein isoforms or truncated versions that retain some function. [28]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 | High-purity recombinant Cas9 protein for complex formation with gRNA. [28] | Direct injection into axolotl or zebrafish embryos. [28] |

| crRNA & tracrRNA | Two-part guide RNA system; the crRNA provides target specificity, tracrRNA supports Cas9 binding. [28] | Flexible gRNA design for various targets. |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity PCR enzyme for accurate amplification of target loci for genotyping. [28] | Verifying mutations and screening Crispants. |

| MMR with Ficoll & PenStrep | Injection and rearing solutions for embryos. Ficoll aids in needle delivery, antibiotics prevent infection. [28] | Maintaining embryo health post-injection in aquatic species. |

Experimental Protocol: Targeted Hox Gene Knockout in Zebrafish

This protocol outlines the key steps for investigating Hox gene function in limb (pectoral fin) development, providing a framework to study genes where murine knockouts are embryonically lethal. [29]

1. Bioinformatic Guide RNA (gRNA) Design

- Identify Target Exon: Focus on a 5' exon or an exon encoding an essential protein domain to maximize the chance of a complete loss-of-function. [31]

- Design gRNAs: Use software like Benchling with default parameters (guide length: 20, PAM: NGG) to identify all possible target sites. [28]

- Check Specificity: Rank gRNAs based on on-target scores and screen the top candidates using the organism's genome database (e.g., Axolotl Genome Blast for axolotl) to select guides with a single, unique hit to the intended locus. [28]

2. CRISPR Complex Formation

- Resuspend crRNA and tracrRNA to 100 µM in nuclease-free buffer. [28]

- Prepare Complex: Mix 2 µl of each RNA, heat at 95°C for 5 minutes, and cool to room temperature to anneal. [28]

- Add Cas9 Protein: Add 7 µl of UltraPure water and 1.2 µl of Cas9 protein (10 µg/µl). Mix gently, incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes, and store on ice for same-day injection. [28]

3. Microinjection into One-Cell Embryos

- Needle Preparation: Use a micropipette puller and borosilicate capillary tubing to create injection needles. [28]

- Embryo Preparation: Collect freshly laid one-cell embryos and align them on an agarose ramp. [28]

- Injection: Using a microinjector and micromanipulator, deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 solution directly into the cell yolk or cytoplasm. [28]

4. Screening and Validation (Key for Long-Generation Organisms)

- Raise Injected Embryos: A subset of embryos can be raised to adulthood to establish germline transmission (F0 founders). [28]

- Genotype F1 Offspring: Cross F0 founders with wild-type animals. Extract genomic DNA from F1 progeny, PCR-amplify the target locus, and sequence the products to identify and confirm heritable indels. [28]

5. Phenotypic Analysis

- Morphology: Compare the skeletal structures of mutant and wild-type adult animals. In zebrafish Hox cluster mutants, this reveals severe shortening of the pectoral fin and defects in the endoskeletal disc. [29]

- Molecular Cartilage Staining: Use Alcian Blue or similar stains on larvae to visualize cartilage development and malformations. [29] [32]

- Gene Expression: Use whole-mount in situ hybridization on mutant embryos to analyze expression changes in key patterning genes (e.g.,

shha), which may be downregulated upon Hox gene loss. [29]

This guide details a specific molecular rescue strategy where overexpression of the KAT6B gene compensates for the loss of the KAT6A gene, preventing embryonic lethality in mouse models. This approach provides a proof-of-concept for overcoming genetic defects in developmental pathways, offering a valuable template for researchers investigating similar strategies in other contexts, including Hox limb development.

A pivotal 2025 study demonstrated that a 4-fold overexpression of the Kat6b gene was sufficient to completely rescue all developmental defects, including embryonic lethality, in Kat6a null mice [33] [34]. The rescued mice exhibited normal vitality and a standard lifespan [35]. KAT6A and KAT6B are histone acetyltransferases (HATs) with identical protein domain structures that function as mutually exclusive catalytic subunits within a multi-protein complex [33] [36]. While their loss-of-function leads to distinct and severe phenotypic consequences, this evidence shows that at non-physiological expression levels, KAT6B can assume the essential functions of KAT6A [33].

Key Quantitative Rescue Outcomes

The table below summarizes the core phenotypic rescues achieved through Kat6b overexpression in Kat6a-null mice:

| Rescue Outcome | Description in Kat6a-/- Model | Rescue in Kat6a-/- Tg(Kat6b) Model |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Lethality | Lethality at E14.5-E18.5; absent at Mendelian ratios at E18.5 [33] | Complete rescue of lethality; mice born at expected Mendelian ratios with normal lifespan [33] [34] |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | Absence of transplantable HSCs [33] | Rescued absence of HSCs [33] [34] |

| Histone Acetylation | Reduced H3K9 and H3K23 acetylation [33] | Restored acetylation levels at H3K9 and H3K23 [33] |

| Gene Expression | Critical gene expression anomalies [33] | Reversal of gene expression defects [33] |

| Developmental Defects | Anterior homeotic transformation, cleft palate, cardiac defects [33] | Rescue of all previously described defects [33] [34] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key stages of the rescue experiment, from model generation to validation:

Generation of theKat6bOverexpression Model

- Transgene Construction: A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone (RP23-360F23) containing the entire Kat6b coding sequence, plus 21 kb of 5' and 42 kb of 3' flanking sequences, was used to ensure genomic context and regulatory fidelity [33].

- Mouse Model Generation: This BAC was used to create transgenic Tg(Kat6b) mice on an FVB x BALB/c hybrid background, as the overexpression was not viable on inbred backgrounds [33].

- Copy Number & Expression Validation: The founders had seven copies of the pBACe3.6 construct integrated, resulting in a stable 4-fold increase in Kat6b mRNA levels over endogenous levels, as confirmed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) [33].

Genetic Crosses and Genotyping

- Crossing Scheme: Tg(Kat6b) heterozygous mice were crossed with mice heterozygous for a Kat6a null allele (lacking exons 5–9) [33].

- Genotyping: Offspring were genotyped via standard PCR protocols to identify the desired Kat6a-/- Tg(Kat6b) genotype.

- Mendelian Ratio Tracking: Embryos and fetuses were collected at critical developmental stages (E9.5, E14.5, E18.5) and genotyped to confirm the presence of Kat6a-/- Tg(Kat6b) individuals at expected Mendelian ratios, the first indicator of rescued lethality [33].

Key Validation Experiments

- Viability and Lifespan Assessment: Rescued Kat6a-/- Tg(Kat6b) mice were monitored from birth to adulthood to confirm normal growth, vitality, and lifespan [33] [34].

- Histone Acetylation Analysis:

- Methodology: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed using antibodies specific for acetylated Histone H3 Lysine 9 (H3K9ac) and Histone H3 Lysine 23 (H3K23ac).

- Outcome: The assay confirmed that Kat6b overexpression restored acetylation levels at these specific histone residues in Kat6a-null tissues [33].

- Gene Expression Analysis:

- Methodology: Transcriptomic analysis (e.g., RNA-seq) was used to compare gene expression profiles.

- Outcome: The analysis showed that Kat6b overexpression reversed critical gene expression anomalies found in Kat6a mutants, indicating a restoration of the transcriptional program [33].

- Functional Rescue of Hematopoiesis:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does KAT6B overexpression rescue KAT6A loss at a molecular level? KAT6A and KAT6B are paralogs with identical protein domain structures and are mutually exclusive catalytic subunits of the same multi-protein complex (including BRPF1, ING5, etc.) [33] [36]. They share identical histone acetylation targets, primarily H3K9 and H3K23 [33]. The rescue occurs because increasing KAT6B protein levels allows it to occupy the KAT6A/B-complex and acetylate the critical genomic targets normally regulated by KAT6A, despite inherent differences in their amino acid sequence and target gene specificity at endogenous levels [33].

Q2: What are the critical thresholds for successful rescue? The study identified a 4-fold overexpression of Kat6b mRNA as the critical threshold [33]. This level was sufficient to restore normal development and lifespan. Lower levels of expression were not tested in this paradigm, and the viability of the rescue was dependent on genetic background, highlighting that thresholds may be context-specific [33].

Q3: What are the primary risks or pitfalls of this approach? The most significant risk is the potential for gain-of-function effects. Independent research shows that Kat6b overexpression in mice can lead to adverse phenotypes, including aggression, anxiety, and spontaneous epilepsy [38]. This underscores the need for precise control over expression levels and thorough phenotypic screening. Furthermore, the success in one genetic background (FVB x BALB/c) but not inbred backgrounds indicates that modifier genes can significantly influence the outcome [33].

Q4: How does this inform research on Hox genes and limb development? While the primary study focused on overall embryonic development and hematopoiesis, KAT6A is a known regulator of anterior-posterior patterning and homeotic transformations [33] [36]. The rescue of "anterior homeotic transformation" in Kat6a mutants [33] directly demonstrates that this strategy can correct patterning defects governed by Hox and other transcription factors. This provides a strong rationale for applying paralog overexpression to rescue similar defects in Hox-mediated limb development.

Molecular Mechanism of Rescue

The diagram below illustrates how KAT6B overexpression compensates for KAT6A loss at the molecular complex level:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experiment | Key Details / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BAC Clone RP23-360F23 | Source of the Kat6b transgene for microinjection. | Contains ~63 kb of genomic context (21 kb 5', 42 kb 3'). Essential for physiological expression patterns [33]. |

| Kat6a Knockout Mouse Model | Model of embryonic lethality to be rescued. | Null allele lacking exons 5-9. Confirm genotype via PCR of the deleted region [33]. |

| FVB x BALB/c Hybrid Background | Genetic background for the transgenic line. | Critical: Kat6b overexpression was not viable on inbred backgrounds [33]. |

| H3K9ac & H3K23ac Antibodies | Validate molecular rescue via ChIP-qPCR or Western Blot. | Confirms restoration of primary enzymatic function [33]. |

| qPCR Assays for Kat6b | Quantify transgene expression levels. | Confirm the 4-fold mRNA overexpression threshold is achieved [33]. |

| HSC Transplantation Assay | Functional test for rescued hematopoiesis. | Gold-standard functional assay to prove HSCs are not just present but functional [33] [37]. |

This technical guide is based on a peer-reviewed study published in Nature Communications in 2025. The protocols and data have been synthesized for clarity and application in a research setting. Researchers are advised to consult the original literature for the most granular methodological details [33].

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide: Navigating Embryonic Lethality in Hox Limb Research

FAQ: Why is embryonic lethality a major challenge in studying Hox gene function in limb development?

Embryonic lethality occurs because Hox genes are master regulators of body plan formation. Deleting critical Hox clusters often disrupts the development of essential organs or axial patterning long before limb formation begins, preventing the study of their specific role in limbs. For example, in zebrafish, hoxba;hoxbb double homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal by approximately 5 days post-fertilization (dpf), complicating analysis [39] [40].

FAQ: How can I study limb defects if the mutant embryos die before limb buds form?

The key is to use functional redundancy to your advantage. Research in zebrafish shows that while single Hox cluster mutants may have mild phenotypes, double mutants can reveal the essential functions hidden by redundancy. For instance, a single allele from either the hoxba or hoxbb cluster is sufficient for pectoral fin formation. Severe phenotypes like a complete absence of fins only manifest in hoxba;hoxbb double homozygous mutants [39] [40].

Troubleshooting Guide: My compound Hox mutant shows no phenotype. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Incomplete penetrance due to residual redundancy.

- Solution: Consider that functional redundancy may exist not just within a cluster, but between different Hox clusters (e.g., HoxA and HoxD). You may need to generate higher-order mutants. Penetrance can also be low; the absence of pectoral fins in

hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5blocus deletion mutants was observed with low penetrance [39] [40]. - Problem: The analysis is focused on later stages, missing early molecular defects.

- Solution: Analyze earlier developmental stages. In

hoxba;hoxbbmutants, the expression of the early limb markertbx5ais nearly undetectable in the pectoral fin field at 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf), which is the root cause of the subsequent fin absence [39].

Troubleshooting Guide: How can I confirm the specific Hox genes responsible for the limb positioning phenotype?

- Solution 1: Conduct frameshift mutation experiments. Test individual candidate genes. Frameshift mutations in

hoxb4a,hoxb5a, andhoxb5bdid not fully recapitulate the cluster deletion phenotype, indicating complex regulation [39]. - Solution 2: Generate genomic locus deletion mutants. Delete specific genomic loci containing key genes. Deletion mutants for the

hoxb4a,hoxb5a, andhoxb5bloci resulted in the absence of pectoral fins, confirming their pivotal role [39].

Table 1: Phenotypic Penetrance in Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Penetrance | Key Molecular Marker (tbx5a) |

|---|---|---|---|

hoxba-/- |

Morphological abnormalities | 100% | Reduced expression [39] |

hoxba-/-; hoxbb+/- |

Fins present | 100% | Not specified |

hoxba+/-; hoxbb-/- |

Fins present | 100% | Not specified |

hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- |

Complete absence | 100% (15/15 embryos) | Failed induction in LPM [39] |

hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b locus deletion |

Absence of pectoral fins | Low penetrance | Not specified [39] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Limb Development Studies

| Research Reagent | Type/Model | Critical Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) |

Model Organism | Ideal for genetic manipulation and in vivo analysis of embryonic development [39] [40]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Gene Editing Tool | Used to generate targeted hox cluster deletions and frameshift mutations [39] [40]. |

hoxba; hoxbb double mutant |

Genetic Model | Reveals functional redundancy and is essential for studying pectoral fin positioning [39]. |

tbx5a probe/antibody |

Molecular Marker | Key indicator for the induction of the pectoral fin field in the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) [39]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Signaling Molecule | Used to test the competence of the LPM to induce fin bud formation; response is lost in hoxba;hoxbb mutants [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Hox Cluster Compound Mutants in Zebrafish

This protocol outlines the steps for creating and validating double cluster mutants to overcome functional redundancy, based on methods from [39] [40].

- Design of gRNAs: Design multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) flanking the entire genomic region of the target hox clusters (e.g.,

hoxbaandhoxbb). - Microinjection: Co-inject Cas9 protein and the pool of gRNAs into single-cell zebrafish embryos.

- Founder (F0) Generation: Raise the injected embryos to adulthood. These are mosaic founders.

- Outcrossing and Identification: Outcross F0 fish to wild-type fish. Screen the F1 offspring for large deletions via PCR and DNA sequencing.

- Establishing Mutant Lines: Raise F1 fish carrying the deletion and outcross them to establish stable heterozygous lines.

- Generating Double Mutants: Cross single heterozygous mutants for different clusters (e.g.,

hoxba+/-andhoxbb+/-) to generate double heterozygous offspring. - Incrossing for Homozygotes: Incross the double heterozygotes (

hoxba+/-; hoxbb+/-). According to Mendelian genetics, 6.25% (1/16) of the progeny are expected to be double homozygous mutants. Genotype embryos at appropriate stages for analysis.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Early Limb Bud Induction viaIn SituHybridization

This protocol details how to visualize the failure of fin bud induction in mutants before lethality [39].

- Sample Collection: Collect wild-type and mutant embryos at key stages (e.g., 24-30 hpf for zebrafish pectoral fin induction).

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C.

- Probe Synthesis: Generate labeled antisense RNA probes for key marker genes like

tbx5a. - In Situ Hybridization: Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization following standard protocols to detect

tbx5amRNA. - Imaging and Analysis: Image the stained embryos. In

hoxba;hoxbbmutants, thetbx5asignal in the lateral plate mesoderm will be significantly reduced or absent compared to wild-type, confirming a failure of fin field specification [39].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

Solving Experimental Challenges: From Penetrance Issues to Phenotype Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions: Technical Troubleshooting

Q1: Our zebrafish Hox cluster mutants show variable or incomplete penetrance of pectoral fin defects. What is the likely genetic explanation and how can we address this? A1: Incomplete penetrance in your mutants is likely due to functional redundancy between Hox clusters. Research demonstrates that while single hoxba or hoxbb cluster mutants show only mild fin abnormalities, double homozygous mutants (hoxba;hoxbb) exhibit complete absence of pectoral fins, but with a penetrance of approximately 5.9% (15/252 embryos), consistent with Mendelian expectations [41] [39]. This occurs because an allele from either the hoxba OR hoxbb cluster is sufficient for normal pectoral fin formation [40]. To address this, implement complementation testing through systematic genetic crosses to identify redundant gene functions.

Q2: What molecular marker should we use to confirm the earliest defects in pectoral fin formation in Hox cluster mutants? A2: Monitor tbx5a expression via in situ hybridization at 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf). In hoxba;hoxbb double mutants, tbx5a expression is nearly undetectable in the lateral plate mesoderm, indicating failure of fin bud initiation before morphological signs appear [41] [42]. This marker provides the earliest molecular readout of pectoral fin specification defects in your mutants.

Q3: Which specific Hox genes are most critical for pectoral fin positioning, and will frameshift mutations in these genes recapitulate the cluster deletion phenotype? A3: The pivotal genes are hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b within the hoxba and hoxbb clusters [41] [39]. However, frameshift mutations in individual genes may not fully recapitulate the complete absence of pectoral fins seen in cluster deletions [40]. Deletion mutants targeting these specific genomic loci show absence of pectoral fins but with low penetrance, suggesting cooperative function among these genes [42].

Q4: Why might our Hox cluster mutant embryos be dying before we can analyze pectoral fin development? A4: Hoxba;hoxbb double homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal around 5 dpf [41] [40]. To work with these mutants, prioritize analysis of earlier developmental stages (24-48 hpf) focusing on molecular markers like tbx5a rather than waiting for morphological fin development. Consider conditional knockout strategies or mosaic analysis to bypass early lethality issues.

Quantitative Phenotype Data from Key Studies

Table 1: Penetrance of Pectoral Fin Defects in Zebrafish Hox Mutants

| Genotype | Phenotype | Penetrance | Molecular Defect | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba⁻⁄⁻; hoxbb⁻⁄⁻ | Complete absence of pectoral fins | 5.9% (15/252) | Absent tbx5a expression | [41] [39] |

| hoxba⁻⁄⁻ OR hoxbb⁻⁄⁻ | Mild fin abnormalities | Variable | Reduced tbx5a expression | [41] |

| hoxba⁻⁄⁻; hoxbb⁺⁄⁻ OR hoxba⁺⁄⁻; hoxbb⁻⁄⁻ | Normal pectoral fins | 100% | Normal tbx5a expression | [41] [40] |

| hoxb4a/hoxb5a/hoxb5b deletion mutants | Absence of pectoral fins | Low penetrance | Not specified | [41] |

Table 2: Key Molecular Markers for Analyzing Hox Mutant Phenotypes

| Marker | Expression Timing | Expression Domain | Function in Fin Development | Utility in Mutants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tbx5a | 30 hpf | Pectoral fin field, lateral plate mesoderm | Master regulator of fin bud initiation | Earliest indicator of fin specification defects [41] [40] |

| shha | 48 hpf | Posterior fin bud | Regulation of cell proliferation in developing fins | Indicator of later fin growth defects [29] |

| Fgf10 | Early bud stage | Prospective fin mesoderm | Initiation of fin bud outgrowth | Marker of bud initiation competence [5] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Generating Hox Cluster Deletion Mutants Using CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol is adapted from established methods for deleting entire Hox clusters in zebrafish [41] [43]:

Design guide RNAs (gRNAs): Target flanking regions of the cluster to be deleted. For example, for the hoxbb cluster (25.5 kb), design one gRNA before the initiation codon of the 5'-most gene (hoxb8b) and another after the stop codon of the 3'-most gene (hoxb1b) [43].

Synthesize gRNAs and Cas9 mRNA using in vitro transcription kits.

Microinjection: Co-inject both gRNAs and Cas9 mRNA into single-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

Genotype F0 embryos at 48 hpf using PCR with dual lateral primers that flank the entire cluster. Successful deletion is confirmed when a large fragment cannot be amplified.

Screen for off-target effects using online prediction tools and sequence potential off-target sites.

Establish stable lines by outcrossing F0 founders and identifying germline transmission.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Early Fin Bud Specification Defects

Collect embryos from intercrosses of heterozygous cluster mutants at appropriate stages (24-48 hpf).

Fix embryos in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight.

Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization for tbx5a using standard protocols.

Genotype individual stained embryos by PCR after imaging to correlate phenotype with genotype.

Analyze expression patterns specifically in the lateral plate mesoderm where pectoral fin precursors reside.

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Hox Limb Development Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specification | Experimental Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 system | gRNAs targeting cluster flanking regions | Generation of large cluster deletions | Delete entire hoxba/hoxbb clusters (25.5 kb) [43] |

| tbx5a probe | antisense RNA probe | In situ hybridization marker | Detect earliest fin specification defects [41] |

| shha probe | antisense RNA probe | In situ hybridization marker | Analyze later fin growth defects [29] |

| Transgenic reporter lines | myl7:EGFP, kdrl:mCherry | Live imaging of heart development | Assess cardiac defects in Hox mutants [43] |

| Retinoic acid pathway modulators | Chemical inhibitors/activators | Test competence for fin initiation | Evaluate RA response in Hox mutants [41] |

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Embryonic lethality prevents analysis of later developmental stages.