Overcoming Specificity Challenges in Hox Dominant-Negative Experiments: A Strategic Guide for Genetic Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals tackling specificity issues in Hox dominant-negative experiments.

Overcoming Specificity Challenges in Hox Dominant-Negative Experiments: A Strategic Guide for Genetic Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals tackling specificity issues in Hox dominant-negative experiments. We explore the foundational principles of dominant-negative mechanisms, detailing how mutant polypeptides disrupt wild-type protein function in multimeric complexes. The content covers advanced methodological approaches including base editing technology for precise mutation installation and the design of context-appropriate functional assays. A major focus is dedicated to systematic troubleshooting strategies for optimizing experimental specificity and validation techniques to distinguish true dominant-negative effects from other molecular mechanisms. By integrating structural biology insights with practical experimental guidance, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy and reliability of dominant-negative research in Hox genes and related developmental systems.

Understanding Dominant-Negative Mechanisms: From Basic Concepts to Hox Protein Complexes

In genetic research, particularly in the study of transcription factors like Hox genes, accurately distinguishing between mutation types is crucial for experimental validity. While loss-of-function (LOF) mutations simply reduce or eliminate protein activity, dominant-negative (DN) mutations present a more complex mechanistic picture. DN mutations produce a mutant protein that not only loses its own function but also actively interferes with the activity of the wild-type protein from the unaffected allele [1]. This interference can exacerbate the haploinsufficiency state in autosomal dominant diseases, leading to more severe phenotypic outcomes [1].

Understanding this distinction is particularly critical in Hox gene research, where genes direct the formation of many body structures during early embryonic development and disruptions can lead to significant developmental defects and disease [2]. This guide provides essential troubleshooting frameworks for researchers navigating the technical challenges of DN mutation studies in Hox and related genetic research.

Core Concepts: Distinguishing Mutation Mechanisms

What defines a dominant-negative mutation at the molecular level?

A dominant-negative mutation occurs when a mutant subunit disrupts the function of a wild-type subunit within a multimeric protein complex. The key distinction from simple LOF lies in this interference mechanism – the mutant protein actively disrupts the normal protein, rather than merely being non-functional [1].

Several well-characterized molecular mechanisms can produce dominant-negative effects:

- Formation of inactive complexes: Mutant proteins form heterodimers with their wild-type counterparts, rendering the entire complex dysfunctional [1]. This is commonly observed in collagen disorders like Osteogenesis Imperfecta [1].

- Altered protein trafficking: Mutant proteins can cause entrapment of wild-type proteins in cellular compartments like the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), preventing their trafficking to functional destinations [1].

- Competitive binding inhibition: Mutant proteins compete with wild-type proteins for binding to shared substrates or ligands [1], as seen in Von Willebrand disease [1].

- Protein destabilization: Mutant proteins can reduce the stability of wild-type proteins, leading to their premature degradation, as observed with certain p53 tumor suppressor mutants [1].

How do the structural impacts of DN mutations differ from LOF and GOF mutations?

DN mutations exhibit distinct structural signatures that differentiate them from other mutation types. While LOF mutations tend to be highly destabilizing to protein structure, DN mutations typically have milder structural effects but are highly enriched at protein interfaces where subunits interact [3]. This allows the mutant protein to maintain sufficient structural integrity to co-assemble with wild-type subunits while disrupting normal function.

Table 1: Structural and Functional Characteristics of Different Mutation Types

| Feature | Loss-of-Function (LOF) | Dominant-Negative (DN) | Gain-of-Function (GOF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Reduced or absent protein function | Mutant protein interferes with wild-type function | New or enhanced protein function |

| Typical Inheritance | Recessive | Dominant | Dominant |

| Impact on Protein Structure | Often highly destabilizing | Milder effects; enriched at interfaces | Variable; may create new interaction surfaces |

| Variant Clustering in 3D Space | Spread throughout structure | Clustered at functional interfaces | Often clustered in regulatory regions |

| Computational Prediction Accuracy | Relatively high | Currently limited | Currently limited |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Experimental Challenges in DN Research

How can I validate the specificity of my dominant-negative constructs?

Problem: Non-specific effects of DN constructs complicate interpretation of experimental results, particularly in Hox research where functional redundancy between paralogs may exist [2].

Solutions:

- Employ orthogonal validation methods: Combine multiple approaches to confirm specificity, including rescue experiments with wild-type protein and targeted mutation of specific functional domains.

- Utilize structural guidance: DN mutations cluster at protein interfaces [3]. Focus mutagenesis efforts on these regions rather than creating global destabilization.

- Control for functional redundancy: In Hox genes, where paralogs can substitute for each other [2], test whether overexpression of other paralogs can compensate for DN effects.

Case Example: In Hox research, DN forms are often generated by deleting the DNA-binding domain [4]. To validate specificity:

- Co-express with wild-type Hox proteins and assess rescue of function

- Test effects on related paralogs to rule out cross-interference

- Use multiple, distinct DN constructs targeting different functional domains

How can I confirm a suspected dominant-negative mechanism?

Problem: It can be challenging to distinguish true DN effects from other mechanisms like haploinsufficiency or gain-of-function, particularly for novel variants.

Experimental Framework:

- Dimerization assays: Directly test whether mutant subunits associate with wild-type partners using co-immunoprecipitation, FRET, or similar techniques.

- Functional complementation: Express mutant and wild-type proteins together and assess whether the mutant inhibits wild-type function beyond simple dilution effects.

- Structural analysis: Use protein stability predictors (like FoldX) to characterize energetic impacts; DN mutations typically show milder destabilization (lower |ΔΔG|) than LOF mutations [3].

- Cellular localization: Determine if mutants alter wild-type protein trafficking, particularly ER retention, which is a common DN mechanism for secretory proteins [1].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues in DN Studies

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected severe phenotype | Non-specific DN effects | Validate construct specificity; use multiple DN targets; include rigorous controls |

| Inconsistent results across assays | Variable expression levels | Standardize expression systems; use inducible systems; quantify protein levels |

| Inability to distinguish DN from LOF | Overly destabilizing mutations | Focus mutations on interface residues; use milder mutations; assess structural impact with predictors |

| Cell viability issues | Excessive interference with essential functions | Use inducible expression systems; titrate expression levels; consider hypomorphic alleles |

How can I optimize experimental design for studying DN mutations?

Problem: Suboptimal experimental design can lead to misinterpretation of DN effects and false conclusions.

Best Practices:

- Expression system selection: Choose expression levels that approximate physiological conditions. Overexpression can create artificial effects, while insufficient expression may miss true DN interactions.

- Proper controls: Always include:

- Wild-type only controls

- Mutant only controls

- Co-expression conditions at different ratios

- Empty vector controls

- Quantitative measurements: Use quantitative assays that can detect partial function and intermediate states rather than binary readouts.

- Structural context: Consider full biological assemblies rather than isolated subunits, as intermolecular interactions significantly impact observed stability perturbations [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for DN Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Dominant-Negative Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in DN Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Yeast episomal plasmids (YEp) for overexpression [5] | Enable high-level expression of DN constructs; compensate for unstable mutant proteins |

| Reporter Systems | FUS1-lacZ, FUS1-HIS3 in yeast [5] | Provide sensitive detection of pathway activation/inhibition for functional assays |

| Stability Predictors | FoldX [3] [6] | Calculate ΔΔG values to predict structural impacts and distinguish DN from LOF mutations |

| Specificity Controls | Dominant-negative forms with targeted domain deletions [4] | Validate that observed effects are specific to intended molecular interactions |

| Validation Tools | Co-immunoprecipitation assays, protein complementation assays | Directly test physical interactions between mutant and wild-type subunits |

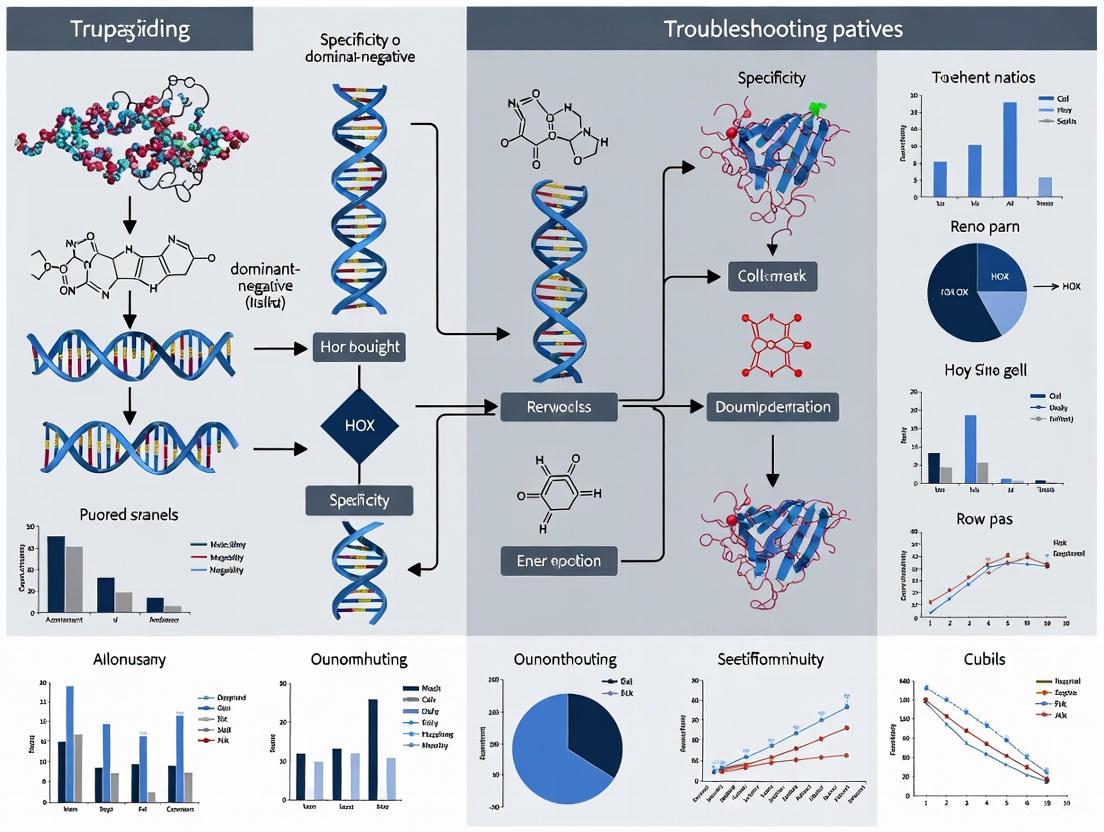

Visualizing Dominant-Negative Mechanisms and Experimental Approaches

Molecular Mechanisms of Dominant-Negative Interference

Experimental Workflow for DN Mutation Analysis

Emerging Frontiers and Clinical Implications

The challenges in studying DN mutations extend beyond basic research into therapeutic development. Current computational variant effect predictors show limited accuracy for DN and GOF mutations compared to LOF variants [3] [6]. This has significant implications for clinical variant interpretation, as many pathogenic DN mutations may be misclassified or overlooked in diagnostic pipelines.

However, new approaches show promise. Integration of protein structural data with phenotypic information can improve mechanism prediction [6]. Specifically, combining metrics like variant clustering in 3D space (EDC) and predicted energetic impact (ΔΔG) generates mLOF scores that better distinguish molecular mechanisms [6].

In Hox research specifically, these principles are critical. When generating DN forms of Hoxa4, Hoxa5, Hoxa6, and Hoxa7 by deleting DNA-binding domains [4], researchers must include careful controls to validate specificity, as the high similarity between Hox paralogs [2] creates potential for cross-interference and misinterpretation. The therapeutic implications are significant – conditions driven by DN mechanisms may require different approaches (e.g., allele-specific inhibition) compared to simple LOF disorders (e.g., gene replacement) [6].

In molecular biology, a dominant-negative (DN) effect occurs when a mutant, non-functional subunit of a protein complex not only loses its own function but also actively disrupts the activity of the wild-type subunits within the same multimeric structure [3]. Unlike simple loss-of-function mutations, DN mechanisms involve the mutant subunit "poisoning" the entire complex, often leading to more severe pathological consequences. This technical resource center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers investigating these complex molecular phenomena, with particular emphasis on applications in Hox gene research and therapeutic development.

Core Mechanisms: How Mutant Subunits Disrupt Complex Function

Structural Principles of Dominant-Negative Interference

The molecular basis of dominant-negative poisoning revolves around several key mechanisms that mutant subunits exploit to disrupt normal protein complex function:

Interference at Protein Interfaces: DN mutations are highly enriched at critical protein-protein interaction interfaces, allowing mutant subunits to incorporate into complexes while preventing proper functional conformations [3]. These mutations typically have milder effects on individual protein stability compared to loss-of-function mutations, as the mutant protein must remain stable enough to co-assemble with wild-type partners [3].

Poisoning of Multimeric Assemblies: In homomeric complexes (composed of multiple identical subunits), a single mutant subunit can disrupt the function of the entire oligomeric structure. The mutant subunit occupies a position that would normally be filled by a functional subunit, creating a structurally defective complex [3].

Sequestration of Wild-Type Partners: Mutant subunits may irreversibly bind to and sequester essential binding partners, cofactors, or substrates, rendering them unavailable to functional complexes in the cell.

Distinctive Features Compared to Other Mutation Types

The table below summarizes key differences between dominant-negative mutations and other pathogenic mutation types:

| Feature | Dominant-Negative (DN) | Loss-of-Function (LOF) | Gain-of-Function (GOF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Effect | Disrupts function of wild-type partners | Reduces or eliminates protein function | Confers new or enhanced activity |

| Protein Stability | Usually mildly destabilizing | Often highly destabilizing | Variable effects on stability |

| Structural Impact | Enriched at protein interfaces | Distributed throughout structure | Often clustered in 3D space |

| Inheritance Pattern | Typically autosomal dominant | Autosomal recessive or dominant | Typically autosomal dominant |

| Therapeutic Strategy | Subunit displacement or selective degradation | Gene replacement or function restoration | Targeted inhibition or modulation |

Diagram Title: Mutant Subunit Poisoning of Protein Complexes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What distinguishes a dominant-negative mutation from a simple loss-of-function mutation?

A dominant-negative mutation not only eliminates the function of the mutant protein but also actively disrupts the activity of co-expressed wild-type proteins within the same multimeric complex [3]. In contrast, a simple loss-of-function mutation only affects the protein product encoded by the mutant allele. The key distinction lies in this "poisoning" effect, where the mutant subunit interferes with functional complexes, typically resulting in more severe phenotypic consequences than haploinsufficiency.

Q2: Why are dominant-negative mutations particularly problematic in homomeric protein complexes?

Homomeric complexes (composed of multiple identical subunits) are especially vulnerable to dominant-negative effects because a single mutant subunit can incorporate into the multimeric structure and disrupt its function [3]. The mutant subunit occupies a position that would normally be filled by a functional wild-type subunit, creating a structurally compromised complex. This poisoning effect explains why these mutations often follow autosomal dominant inheritance patterns despite the presence of a wild-type allele.

Q3: How can I experimentally distinguish between dominant-negative and haploinsufficiency mechanisms?

To distinguish these mechanisms, consider the following experimental approaches:

- Express the mutant protein in cells containing endogenous wild-type protein and measure whether it disrupts function beyond simple reduction.

- Test whether the mutant subunit incorporates into protein complexes using co-immunoprecipitation.

- Determine if the mutant protein exerts a more severe effect than complete knockout or knockdown of one allele.

- Analyze whether the mutant protein shows preferential accumulation at protein interfaces, a hallmark of DN mutations [3].

Q4: What structural characteristics make a mutation likely to act through a dominant-negative mechanism?

Dominant-negative mutations frequently share these structural characteristics:

- Location at critical protein-protein interaction interfaces [3]

- Relatively mild effects on individual protein stability (allowing mutant subunit to incorporate into complexes)

- Clustering in three-dimensional space within the protein structure

- Preservation of binding domains with disruption of functional domains

- In enzymatic complexes, mutations often affect active sites while preserving complex assembly

Troubleshooting Guide for Dominant-Negative Experiments

Problem: Inconsistent Dominant-Negative Effects Across Experimental Replicates

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Expression Levels | Quantify mutant and wild-type protein expression by Western blot; measure mRNA levels by qRT-PCR | Use inducible expression systems; optimize transfection protocols; include expression controls |

| Incomplete Complex Assembly | Perform co-immunoprecipitation assays; analyze complex formation by size-exclusion chromatography | Adjust expression ratios; verify proper folding conditions; check for required co-factors |

| Cellular Compensatory Mechanisms | Monitor related pathway components; perform time-course experiments | Use acute induction systems; inhibit compensatory pathways; employ multiple cell models |

Problem: Difficulty Detecting Incorporation of Mutant Subunits into Complexes

Systematic Troubleshooting Steps:

Verify Protein-Protein Interactions

- Perform co-immunoprecipitation under non-denaturing conditions

- Use proximity ligation assays (PLA) to visualize complex formation in situ

- Employ crosslinking strategies to stabilize transient interactions

Optimize Detection Methods

- Use differentially tagged constructs (e.g., HA-tagged mutant, FLAG-tagged wild-type)

- Implement FRET or BRET assays to monitor real-time interactions

- Consider structural techniques like cryo-EM for detailed complex visualization

Control for Expression Artifacts

- Titrate expression levels to approximate physiological conditions

- Include proper negative controls (non-interacting mutants)

- Verify that tags do not interfere with complex assembly or function

Experimental Protocols for Dominant-Negative Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Dominant-Negative Effects in Cellular Models

Materials and Reagents:

- Expression vectors for wild-type and mutant proteins

- Appropriate cell line model

- Transfection reagents

- Antibodies for immunodetection

- Functional assay reagents specific to your protein complex

Methodology:

Transfection Optimization

- Co-transfect cells with constant wild-type cDNA and increasing concentrations of mutant cDNA

- Maintain total DNA constant using empty vector

- Include controls: wild-type alone, mutant alone, and empty vector

Expression Validation

- Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection

- Verify protein expression by Western blotting

- Quantify expression ratios using densitometry or quantitative fluorescence

Functional Assessment

- Perform activity assays specific to your protein complex

- Measure complex assembly by co-immunoprecipitation or native PAGE

- Analyze subcellular localization by immunofluorescence

Data Analysis

- Plot functional output against mutant:wild-type expression ratio

- Compare to theoretical curves for simple competition vs. active poisoning

- Perform statistical analysis across multiple replicates

Protocol 2: Structural Mapping of Dominant-Negative Mutations

Objective: Identify and characterize potential dominant-negative mutation sites in protein complexes.

Workflow:

Diagram Title: Workflow for Identifying Dominant-Negative Mutations

Method Details:

Structural Data Collection

- Obtain high-resolution structures of target complexes from Protein Data Bank

- Identify subunit interfaces using computational tools (PDB-PISA, ProtCAD)

- Map conserved residues and critical interaction motifs

Mutation Analysis

- Compile known pathogenic mutations from databases (ClinVar, HGMD)

- Analyze three-dimensional clustering using spatial statistics

- Calculate predicted stability effects using FoldX or similar tools [3]

Functional Hotspot Identification

- Identify residues critical for function but not stability

- Map allosteric networks connecting mutation sites to active centers

- Prioritize candidate residues for experimental testing

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | Inducible promoters (Tet-On), viral vectors (lentivirus, AAV) | Controlled expression of mutant and wild-type subunits at physiological ratios |

| Tagging Technologies | HA, FLAG, GFP, luciferase tags, split-protein systems | Detection, purification, and visualization of complex assembly and localization |

| Stability Assays | Cycloheximide chase, thermal shift assays, proteasome inhibitors | Measuring half-life and degradation kinetics of mutant vs. wild-type proteins |

| Interaction Mapping | Co-immunoprecipitation reagents, crosslinkers, nanobodies | Detecting and quantifying protein-protein interactions in complexes |

| Functional Assays | Pathway-specific reporters, enzymatic activity kits, FRET biosensors | Measuring functional output of protein complexes in cellular contexts |

Case Study: EZH2 Dominant-Negative Mutations in Weaver Syndrome

Recent research on EZH2 mutations in Weaver syndrome provides an excellent example of dominant-negative mechanisms in a chromatin-regulatory complex. Unlike early truncating mutations that would cause simple haploinsufficiency, Weaver syndrome-associated EZH2 variants are predominantly missense mutations that produce full-length protein products capable of incorporating into the PRC2 complex [7].

These mutant subunits dominant-negatively impair PRC2-mediated H3K27 methylation despite being expressed at low levels, explaining the overgrowth phenotype characteristic of this disorder [7]. This case highlights how DN mutations can cause selective eviction of associated complexes (cPRC1) and specific derepression of growth control genes, providing a mechanistic basis for the tissue-specific manifestations of the syndrome.

Understanding dominant-negative mechanisms requires moving beyond simple loss-of-function concepts to appreciate how mutant subunits actively disrupt multiprotein complexes. The troubleshooting strategies and experimental approaches outlined here provide a framework for investigating these complex molecular phenomena. As structural biology and computational prediction methods advance, our ability to identify potential DN mutations and design targeted therapeutic interventions continues to improve, offering new opportunities for addressing these challenging pathological mechanisms in disease contexts.

Structural Characteristics of Dominant-Negative vs. Loss-of-Function Variants

FAQs

1. What is the fundamental mechanistic difference between a Loss-of-Function (LOF) and a Dominant-Negative (DN) mutation?

A Loss-of-Function mutation results in a reduction or complete absence of the protein's biological activity, often due to its destabilization or degradation. In contrast, a Dominant-Negative mutation produces a protein that is expressed and stable but interferes with the function of the wild-type protein. The DN mutant protein retains the ability to interact with the same partners as the wild type (e.g., by forming complexes) but blocks a critical step like catalysis or proper assembly, thereby "poisoning" the entire complex [8]. Essentially, a LOF variant leads to a non-functional product, while a DN variant actively antagonizes the normal product.

2. During Hox gene research, my experimental results are inconclusive. How can I determine if a variant is acting via a LOF or DN mechanism?

You can follow this diagnostic experimental protocol to clarify the mechanism:

- Co-expression Assay: Co-express the wild-type (WT) Hox gene and the candidate variant in a cell system. Measure the output of the pathway or complex function.

- Compare to Controls: Compare this functional output to cells expressing only the WT gene and cells expressing only the variant.

- Interpretation: If the co-expression result shows activity that is significantly lower (e.g., <75% in some systems) than the WT-alone control, it suggests a DN effect, as the mutant is actively interfering with the WT function [9]. A simple LOF variant in a heterozygous scenario would typically result in approximately 50% of normal function. Furthermore, if the variant's phenotype is more severe than a known knockout (null) allele, it is a strong indicator of a DN mechanism, as the mutant protein may be disrupting paralog compensation or titrating shared interactors [8].

3. From a structural standpoint, where in a protein are DN mutations most likely to be located?

DN mutations are highly enriched at protein-protein interfaces [3] [10]. This is because their mechanism often requires the mutant subunit to retain the ability to bind to the wild-type subunit (or other partners in a complex) but disrupt a subsequent function. For example, a DN mutation might occur at a site critical for catalytic activity while leaving the structural interface for oligomerization intact, allowing a dysfunctional subunit to incorporate into a multi-protein complex and inactivate it [11] [8].

4. My variant is predicted to be benign by computational predictors, yet my functional data suggests it is pathogenic. Could it be a DN mutation?

Yes. Numerous computational variant effect predictors (VEPs), even those based on sequence conservation, have been shown to underperform on non-LOF mutations, including DN and Gain-of-Function (GOF) variants [3] [10]. These predictors are often trained to identify mutations that severely disrupt protein structure, whereas DN mutations tend to have much milder effects on overall protein stability [3]. Therefore, heavy reliance on these computational scores can cause true pathogenic DN mutations to be missed. Your functional data is paramount.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Inconsistent Phenotypes in Hox Dominant-Negative Experiments

Issue: You are observing variable or weak phenotypic penetrance when expressing a putative Hox DN construct in your model system.

Solution: Follow this structured troubleshooting workflow to identify and resolve the issue.

Step 1: Verify Reagent Integrity and Expression

- Action: Carefully check all reagents. Ensure your DNA construct is sequence-verified. Confirm that the mutant protein is being expressed at the expected molecular weight and at stable levels using Western blotting. Improper storage of materials or use of expired reagents can lead to degraded performance [12].

- Rationale: A DN effect requires the mutant protein to be expressed and stable [8]. Low expression or protein degradation will diminish the DN effect.

Step 2: Titrate Expression Levels

- Action: Systemically vary the ratio of your DN construct to the WT construct (e.g., 1:1, 1:2, 2:1). A true DN effect should show a dose-dependent response, where increasing the amount of DN DNA leads to a stronger inhibitory phenotype [8].

- Rationale: The strength of a DN effect is highly dependent on the relative expression levels of the mutant and wild-type proteins. Finding the optimal stoichiometry is critical.

Step 3: Check for Functional Clustering

- Action: Map your mutation and other known DN mutations onto the three-dimensional protein structure of the Hox protein or its complex. DN mutations often cluster in 3D space at critical functional sites, such as DNA-binding domains or interfaces with co-factors like TALE proteins (e.g., Pbx/Meis) [3] [10].

- Rationale: If your mutation is isolated from known functional clusters, it might not be targeting the key mechanism. Structural clustering can validate the biological plausibility of your DN variant.

Step 4: Rule Out Off-Target Effects

- Action: Include additional controls. Compare your phenotype to that achieved by RNAi or CRISPR knockout of the same Hox gene. As noted in the FAQs, a DN phenotype can sometimes be more severe than a knockout [8]. Also, perform rescue experiments by overexpressing the wild-type Hox gene or a potential titrated binding partner to see if the DN phenotype can be ameliorated.

- Rationale: This helps confirm that the observed effect is specific to the intended target pathway and not due to other experimental artifacts.

Logical Workflow for Troubleshooting Specificity

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for diagnosing specificity issues in Hox DN experiments.

Data Presentation

Quantitative Structural & Functional Differences

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of Dominant-Negative (DN), Loss-of-Function (LOF), and Gain-of-Function (GOF) variants.

| Characteristic | Dominant-Negative (DN) | Loss-of-Function (LOF) | Gain-of-Function (GOF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Mutant subunit "poisons" complexes by incorporating but not functioning [8] | Reduced or absent protein activity (e.g., instability, degradation) [3] | New or enhanced activity (e.g., constitutive activation) [3] |

| Typical Inheritance | Autosomal Dominant [3] | Autosomal Recessive or Dominant (Haploinsufficiency) [3] | Autosomal Dominant [3] |

| Effect on Protein Stability | Mildly destabilizing or neutral [3] | Strongly destabilizing [3] | Variable (can be stabilising or destabilising) |

| Predicted ΔΔG (FoldX) | Milder effects | ~3.89 kcal mol⁻¹ (full structure) [3] | Milder effects |

| Key Structural Location | Highly enriched at protein interfaces [3] [10] | Often buried, affecting folding core | Often at regulatory or active sites |

| Performance of Computational Predictors | Underperform - many are missed [3] [10] | Better identified | Underperform - many are missed [3] [10] |

Table 2: Example outcomes from a DN experimental analysis, as seen in SCN5A (NaV1.5) channel studies [9].

| Variant Class | Number Tested | Number with DN Effect | % with DN Effect | Key Experimental Readout (Peak Current vs. WT-alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe LOF | 35 | 32 | 91% | < 75% |

| Partial LOF | 15 | 6 | 40% | < 75% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for investigating dominant-negative mechanisms.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Baculovirus Expression System | For co-expressing multiple subunits of a protein complex in insect cells. | Used to produce the Gαi1β1γ2 heterotrimer for structural studies of DN mutants [11]. |

| Automated Patch Clamp System | High-throughput functional characterization of ion channel variants. | Employed to assess peak sodium currents in SCN5A DN variants [9]. |

| Structure Prediction Software (e.g., AlphaFold2) | Generating high-quality protein structural models for mutation mapping. | Provides structures for stability prediction with tools like ESM-IF and for visualizing mutation clusters [13]. |

| Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Reagents | Validating physical interactions between wild-type and mutant proteins. | Essential to confirm that a DN mutant retains the ability to bind to the wild-type subunit [8]. |

| Codon Optimization Tool | Improving gene expression levels in heterologous systems. | Critical for ensuring equal and high expression of both WT and DN constructs for stoichiometric experiments [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: Key Methodology for DN Validation

Protocol: Functional Co-expression Assay for Dominant-Negative Effects (Adapted from [9] [8])

1. Objective: To determine if a missense variant interferes with the function of the wild-type protein in a heterologous expression system.

2. Materials:

- Expression vector containing the wild-type cDNA.

- Expression vector containing the candidate variant cDNA.

- Heterologous cell line (e.g., HEK293T).

- Transfection reagent.

- Equipment for functional assay (e.g., patch clamp rig for ion channels, reporter assay for transcription factors).

3. Procedure:

- Day 1: Plate cells appropriately for your functional readout and transfection.

- Day 2: Transfect the cells in multiple groups:

- Group A (WT): Transfect with vector containing only the wild-type gene.

- Group B (Variant): Transfect with vector containing only the variant gene.

- Group C (Co-expression): Transfect with a 1:1 DNA mass ratio of WT and variant vectors.

- Group D (Control): Transfect with an empty vector.

- Day 3-4: Perform the functional assay (e.g., measure ion current, luciferase activity, or protein complex activity).

4. Data Analysis:

- Normalize the functional output of each group to the WT control (Group A).

- A signature of a strong DN effect is observed when the co-expression group (Group C) shows significantly less activity than the WT group, and often less than 50% (see Table 2). This indicates the variant is not just non-functional but is actively suppressing the function of the wild-type protein.

Mechanism of Dominant-Negative Action

The diagram below illustrates how a dominant-negative mutant subunit disrupts the function of a protein complex, compared to healthy and simple loss-of-function states.

What is the core challenge of working with Hox proteins? The central challenge, often termed the "transcription factor specificity paradox," is that Hox proteins possess highly similar DNA-binding homeodomains in vitro, yet they execute distinct and specific functions in vivo [14]. This paradox raises a fundamental troubleshooting question: how do nearly identical transcription factors regulate unique sets of target genes to specify different segment identities along the anterior-posterior axis?

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Achieving Specificity

Why does my dominant-negative Hox construct cause non-specific or off-target effects? This is frequently due to the disruption of shared interaction networks. Hox proteins often achieve specificity by partnering with cofactors, primarily the TALE (Three Amino Acid Loop Extension) homeodomain proteins like Pbx and Meis [14]. A dominant-negative construct that lacks specificity may be indiscriminately interfering with these essential cofactors for multiple Hox proteins.

- Root Cause: Many dominant-negative approaches involve overexpressing the homeodomain alone, which can compete for DNA binding sites but fails to recapitulate the precise cofactor interactions required for specificity.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the design of your dominant-negative construct. Ensure it is tailored to disrupt the function of a specific Hox paralog group by including domains known to interact with specific cofactors.

How can I address the problem of redundancy in my Hox loss-of-function experiments? Genetic redundancy is a major hurdle in vertebrate Hox research. Unlike in Drosophila, where mutating a single Hox gene can cause a clear homeotic transformation, vertebrate Hox genes are organized into 13 paralog groups across four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD) [15]. Genes within a paralog group often have overlapping functions and expression patterns.

- Problem: Knocking out a single Hox gene (e.g., Hoxa3) may yield no phenotype because its paralogs (e.g., Hoxd3) compensate for its loss [15].

- Solution: You must generate paralogous group knockouts. To observe the true function of the third Hox gene, for example, you need to simultaneously knock out Hoxa3, Hoxb3, and Hoxd3 [15]. The table below summarizes the phenotypic outcomes from paralogous knockout studies in mice.

Table 1: Phenotypic Outcomes of Selected Hox Paralogous Knockouts in Mice

| Paralog Group Targeted | Vertebral Element Affected | Observed Phenotype | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 | First Thoracic Vertebra (T1) | Incomplete rib formation [15] | Partial transformation towards a cervical-like identity [15] |

| Hox6 | First Thoracic Vertebra (T1) | Complete transformation to a copy of the seventh cervical vertebra (C7) [15] | Full homeotic transformation; loss of thoracic identity [15] |

| Hox10 & Hox11 | Sacral Vertebrae | Disruption of sacral-pelvic articulation [15] | Combined expression required to specify sacral morphology [15] |

FAQ: Experimental Pitfalls

My ChIP-seq experiment shows weak Hox binding. What could be wrong? Hox transcription factors can bind DNA with low affinity to achieve high specificity, a trade-off that can make their binding difficult to capture [14]. Furthermore, the binding and pioneering activity of some Hox proteins can be dependent on pre-bound TALE cofactors [14].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Cofactor Expression: Check that your cellular system expresses necessary TALE cofactors like Pbx and Meis.

- Consider Cross-linking Conditions: Optimize your cross-linking protocol, as Hox-cofactor-DNA interactions can be transient.

- Leverage New Technologies: Methods like single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) are being developed to more confidently link genotypes to gene expression and protein binding in their endogenous context [16].

Why do I get different Hox mutation phenotypes in different tissues? Hox proteins can employ different cofactors and mechanisms to achieve specificity depending on the tissue context. For example, the network of cofactors and targets for the Hox protein Ultrabithorax (Ubx) differs significantly between the mesoderm and the ectoderm in Drosophila [14].

- Recommendation: Always validate findings in multiple relevant tissues or cell types. A mechanism elucidated in one tissue may not directly apply to another.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Hox Protein Interactions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration for Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| TALE Cofactor Antibodies (e.g., α-Pbx, α-Meis) | For Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) to validate Hox-protein interactions. | Confirm antibody specificity for the intended cofactor to avoid off-target pulldowns. |

| Paralog-Specific Hox Antibodies | For ChIP-seq and immunohistochemistry to map binding and expression. | Crucial to distinguish between highly similar Hox paralogs; requires rigorous validation. |

| CRISPR gRNAs for Paralogous Knockouts | For generating complete loss-of-function in redundant Hox genes. | Must target all active paralogs within a group (e.g., Hoxa5, Hoxb5, Hoxc5) [15]. |

| SDR-seq (Single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing) | To simultaneously profile genomic loci and gene expression in single cells [16]. | Links precise genetic variants (e.g., a Hox mutation) to downstream transcriptional changes. |

| Dominant-Negative Constructs (Engineered) | To disrupt the function of a specific Hox paralog group. | Must include domains for DNA binding and specific cofactor interaction to ensure precision. |

Visualization of Hox Interaction Mechanisms

Hox-TALE Interaction Logic

Paralogous Knockout Workflow

Hox Code Patterning Logic

FAQs: Troubleshooting Dominant-Negative and Hox Specificity Experiments

Q1: My Hox protein mutagenesis experiment is yielding inconsistent phenotypic results. What could be the cause? Inconsistent phenotypes in Hox experiments often stem from overlooking low-affinity DNA binding sites. Hox proteins achieve specificity by binding to clusters of low-affinity sites in enhancer regions, not the traditionally sought high-affinity sites [17]. Mutations designed based on high-affinity consensus sequences may not accurately reflect the native regulatory mechanisms. Ensure your experimental design, such as reporter gene assays, uses sufficiently long enhancer fragments that contain these clustered, low-affinity sites to capture biologically relevant function.

Q2: How can I confirm if a observed phenotypic effect is due to a genuine dominant-negative mechanism? A classic test for a dominant-negative (DN) effect involves two key conditions [18]. First, the phenotype in a heterozygote (A/a) must be more severe than in a heterozygote for a simple loss-of-function allele (A/-). Second, overexpression of the putative DN mutant (a) should worsen the phenotype in the heterozygote. For Hox proteins, which often function with cofactors, this can be complicated. Ensure you also test for potential interference with cofactor binding or collaboration, as DN effects can extend beyond simple homodimer poisoning [19].

Q3: Why are my computational predictions failing to identify pathogenic non-LOF variants in my gene of interest? Most current variant effect predictors (VEPs) are biased towards identifying loss-of-function (LOF) mutations, which are typically highly destabilizing to protein structure. In contrast, dominant-negative (DN) and gain-of-function (GOF) mutations often have milder structural effects and are frequently located at protein-protein interaction interfaces [3]. These non-LOF variants are systematically missed by predictors that rely heavily on conservation or stability metrics. For genes suspected of harboring DN variants, use structure-based methods that specifically look for clustering of variants at interfaces or employ the recently developed mLOF likelihood score [6].

Q4: What molecular evidence can I look for to support a dominant-negative mechanism for a Hox variant? For a Hox variant, evidence for a DN mechanism could include:

- Biochemical Evidence: The mutant Hox protein retains the ability to form homodimers or heterodimers with cofactors (like Extradenticle/Pbx) but produces a complex that has reduced or altered DNA-binding affinity [19].

- Functional Evidence: Co-expression of the mutant Hox protein with the wild-type protein in a cell-based assay (e.g., a transcriptional reporter assay) leads to a significant reduction in activity compared to expression of the wild-type protein alone [18] [9].

- Structural Evidence: The variant is mapped to a protein-protein interaction domain or interface in a structural model, rather than being buried deep in the protein core, which is more typical of LOF variants [3].

Quantitative Data on Dominant-Negative Mechanisms

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on the prevalence and characteristics of dominant-negative mechanisms in genetic disorders.

| Metric | Value | Context and Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype Prevalence | 48% of phenotypes in dominant genes | Accounted for by combined DN and GOF mechanisms [6] | ||

| Intragenic Heterogeneity | 43% of dominant genes | Genes harbor both LOF and non-LOF mechanisms for different phenotypes [6] | ||

| Structural Destabilization ( | ΔΔG | ) | Milder effects | DN/GOF mutations have significantly milder effects on protein structure than recessive LOF mutations [3] |

| VEP Performance | Underperforms on non-LOF | Nearly all computational variant effect predictors perform worse on DN and GOF mutations [3] | ||

| SCN5A LoF Variants with DN Effect | 32 out of 35 (91%) | Most missense loss-of-function variants in the SCN5A gene exert a dominant-negative effect [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Identification

Protocol: Predicting Molecular Mechanism from Protein Structure

This protocol uses the missense Loss-of-Function (mLOF) likelihood score to predict whether a set of variants in a gene acts via LOF or non-LOF (DN/GOF) mechanisms [6].

1. Input Data Collection:

- Collect a set of known pathogenic missense variants for your gene of interest from clinical databases like ClinVar.

- Obtain or generate a high-quality protein structure for the wild-type protein (e.g., from PDB or via AlphaFold2 prediction).

2. Structural Feature Calculation:

- Energetic Impact (ΔΔGrank): Use a protein stability predictor like FoldX to calculate the change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) for each variant. Normalize these values into a rank-based metric (ΔΔGrank) to enable cross-protein comparisons [6].

- Variant Clustering (EDC): Calculate the Extent of Disease Clustering (EDC) metric. This quantifies how spatially clustered the missense variants are within the three-dimensional protein structure. Non-LOF variants tend to cluster at functional sites, while LOF variants are more dispersed [6] [3].

3. mLOF Score Calculation:

- Input the calculated EDC and ΔΔGrank values into the empirical distribution-based model.

- The model computes an mLOF score, which represents the likelihood that the variant set acts via a LOF mechanism. A score below the optimal threshold of 0.508 suggests a non-LOF mechanism (i.e., DN or GOF) [6].

4. Mechanism Prioritization:

- For genes with multiple phenotypes, combine the mLOF score with phenotype semantic similarity analysis to prioritize dominant-negative mechanisms [6].

- Access the method via the provided Google Colab notebook: https://github.com/badonyi/mechanism-prediction.

Protocol: Functional Validation of a Dominant-Negative Effect via Electrophysiology

This protocol outlines a heterologous co-expression assay, as used for SCN5A channels, to test for dominant-negative effects [9].

1. Plasmid Constructs:

- Prepare expression plasmids for the wild-type (WT) cDNA.

- Clone the missense variant of interest into the same expression vector.

2. Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Use a standard heterologous expression system like HEK293T cells.

- Perform transfections with three conditions:

- WT alone: Transfect with plasmid containing the WT gene.

- Variant alone: Transfect with plasmid containing the mutant gene.

- Heterozygous condition: Co-transfect with a 1:1 ratio of WT and mutant plasmid to mimic the heterozygous state in a patient.

3. Functional Assay (Automated Patch Clamp):

- 48-72 hours post-transfection, perform automated patch clamp analysis.

- Measure the peak sodium current (INa) for each of the three transfection conditions.

4. Data Analysis:

- Normalize the peak current values to the WT-alone condition.

- A dominant-negative effect is confirmed if the peak current in the heterozygous co-expression condition is significantly reduced to below 75% of the WT-alone current [9]. This indicates that the mutant protein is actively impairing the function of the WT protein beyond a simple 50% reduction expected from haploinsufficiency.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram Title: Hox Regulation and DN Interference

Diagram Title: DN Mechanism Identification Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The table below lists essential materials and tools for investigating dominant-negative mechanisms in genetic disorders.

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Consideration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX Software | Predicts change in protein stability (ΔΔG) upon mutation. Used to calculate energetic impact for mLOF score [6] [3]. | Distinguishes LOF (high | ΔΔG | ) from non-LOF (low | ΔΔG | ) variants. |

| mLOF Score Colab Notebook | Computes likelihood of LOF mechanism from variant structural data [6]. | Optimal threshold: 0.508. Score <0.508 suggests non-LOF (DN/GOF). | ||||

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of wild-type protein structures for structural analysis and stability calculations [3]. | Use biological assembly files, not just monomers, to capture interface effects. | ||||

| Heterologous Expression System (e.g., HEK293T cells) | Cellular system for co-expressing wild-type and mutant proteins to test for DN effects [9]. | Allows controlled 1:1 expression ratio to mimic heterozygosity. | ||||

| Automated Patch Clamp System | High-throughput functional characterization of ion channel activity for electrophysiology studies [9]. | Critical for quantifying the functional deficit in "heterozygous" conditions. | ||||

| Reporter Gene Assay Vectors | Measure transcriptional output of enhancers regulated by transcription factors like Hox proteins [17]. | Must include native, long-range enhancers with clusters of low-affinity binding sites. |

Advanced Techniques for Installing and Testing Hox Dominant-Negative Mutations

Base Editing Approaches for Precise Dominant-Negative Mutation Installation

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance for researchers employing base editing technologies to install dominant-negative (DN) mutations, with a specific focus on Hox gene research. The content addresses common experimental hurdles, offering detailed protocols and solutions to enhance editing precision and efficiency, framed within the broader context of troubleshooting specificity in DN mutation studies.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Addressing Specificity and Precision

Q1: What are the primary factors causing bystander edits in base editing experiments, and how can they be minimized?

Bystander edits occur when multiple editable bases (adenines or cytosines) are present within the base editor's activity window, leading to unintended nucleotide conversions alongside the desired edit. The width of this editing window is a major factor; broader windows increase bystander risk [20]. To minimize this:

- Select a more precise base editor: Utilize newly engineered editors with narrower activity windows. For example, the ABE-NW1 variant, which incorporates the TadA-NW1 deaminase, exhibits a consistently narrow editing window of 4 nucleotides (protospacer positions 4-7), a significant reduction from the 10-nucleotide window of ABE8e [20].

- Optimize gRNA positioning: Design your single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to position the target adenine within the optimal, narrow window of the chosen base editor, ensuring that other editable bases fall outside this window [20] [21].

Q2: How can I verify the successful installation of a DN mutation without confounding bystander effects?

Accurate genotyping is critical. Use high-fidelity methods such as targeted amplicon high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to analyze the edited population [20] [22]. This method reveals the exact sequence of each read, allowing you to distinguish between clones with only the desired DN mutation and those with additional, unwanted bystander edits. This is a standard practice in base editor scanning experiments to identify specific functional mutations [22].

Q3: Our delivery system lacks efficiency in target cells. What strategies can improve in vivo delivery for DN mutation installation?

The choice of delivery vector is crucial. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors are widely used for in vivo gene therapy applications due to their low immunogenicity and long-term expression.

- Use optimized AAV serotypes: Select AAV capsids with high tropism for your target cells. For example, the capsid-modified AAV-Sia6e vector has demonstrated high infection efficiency in cochlear cells, which could inform similar strategies for other cell types [23].

- Overcome packaging limits: For large base editor constructs, use compact editors (e.g., SaCas9-based ABE8e) or split-intron systems that can be packaged into a single AAV vector, which is a key consideration for clinical application [23].

Q4: What controls are essential to confirm that an observed phenotype is due to the specific DN mutation and not off-target editing?

A comprehensive control strategy is required:

- Measure off-target activity: Use genome-wide methods like GUIDE-seq or computational predictions to identify potential off-target sites, and sequence these sites in your edited samples to confirm the absence of edits [24]. Newer editors like ABE-NW1 have been shown to possess significantly reduced Cas9-dependent and -independent off-target activity compared to ABE8e [20].

- Include a control editor: Perform parallel experiments with a catalytically dead base editor (dBE) or a non-targeting sgRNA to account for potential effects of viral transduction and editor expression.

- Rescue phenotype: If possible, re-express the wild-type protein in the edited cells to see if it rescues the DN-induced phenotype, confirming a direct link.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Installing a DN Mutation using an ABE System

This protocol details the steps for introducing an A•T to G•C mutation to create a DN allele in a Hox gene.

gRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design sgRNAs that position the target adenine within the optimal editing window (e.g., positions 4-7 for ABE-NW1) of your target Hox gene [20].

- Clone the sgRNA sequence into the appropriate plasmid backbone containing the ABE expression system (e.g., ABE8e or ABE-NW1).

Delivery into Target Cells:

- For in vitro studies: Transfect the ABE and sgRNA plasmids into your target cell line (e.g., HEK293T, K562) using a high-efficiency transfection reagent.

- For in vivo studies: Package the ABE and sgRNA constructs into an AAV vector with a suitable serotype. Purify the virus and determine the titer. Administer the AAV to your animal model via the appropriate route (e.g., local injection, systemic delivery) [23].

Harvesting and Genotyping:

- Allow 48-72 hours for editing to occur post-transfection/delivery.

- Extract genomic DNA from the cells or tissue.

- Amplify the target region by PCR and subject the product to Sanger sequencing or HTS to assess editing efficiency and specificity.

Phenotypic Validation:

- Isolate clonal populations by single-cell sorting or dilution cloning.

- Validate the DN mutation in single clones and perform functional assays (e.g., transcriptional reporter assays, differentiation assays) to confirm the dominant-negative phenotype.

Protocol 2: Base Editor Scanning to Identify DN Mutation Effects

This methodology, adapted from studies on DNMT3A, can be used to systematically profile the functional consequences of mutations in a Hox gene [22].

Reporter Cell Line Generation:

- Generate a stable cell line containing a fluorescent reporter (e.g., citrine) whose expression is directly or indirectly regulated by the activity of the Hox protein of interest.

sgRNA Library Transduction:

- Transduce the reporter cell line with a lentiviral library containing a pool of sgRNAs tiling the entire coding sequence of the Hox gene, coupled with a base editor (e.g., BE3 or ABE).

Cell Sorting and Analysis:

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to separate cell populations based on the reporter signal (e.g., high vs. low fluorescence), which corresponds to different levels of Hox protein activity.

- Isolate genomic DNA from the sorted populations and amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences.

- Sequence the amplicons via HTS and compare the abundance of each sgRNA in the different sorted populations to identify mutations that lead to a DN phenotype (e.g., reduced reporter activity).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Adenine Base Editor (ABE) Variants

Table comparing key characteristics of different ABE variants, relevant for selecting the right tool for precise DN mutation installation.

| ABE Variant | Editing Window (Protospacer Positions) | Key Feature | Best Use Case for DN Studies | Bystander Editing Ratio (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABE8e [20] | 3 - 12 (10 bp) | Very high activity | When high efficiency is critical and bystander risk is low | Up to 20.3x higher at flanking adenines vs. ABE-NW1 [20] |

| ABE7.10 [24] | ~5 bp | Canonical, well-established | General purpose editing with a moderate window | Higher than ABE-NW1 [20] [24] |

| ABE-NW1 [20] | 4 - 7 (4 bp) | Narrowest window; reduced off-targets | Precise installation of DN mutations in sequences with multiple adenines | Reference variant for low bystander editing [20] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A list of key reagents, their functions, and considerations for setting up base editing experiments for DN mutation research.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | Catalyzes the A•T to G•C conversion at the target site. | Select for narrow editing window (e.g., ABE-NW1) and high specificity. Available as plasmid or packaged virus [20]. |

| Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Directs the base editor complex to the specific genomic locus. | Design to position target base in the optimal window; check for potential off-target sites [21]. |

| Delivery Vector | Introduces the base editing machinery into the target cells. | In vitro: Transfection reagents. In vivo: AAV vectors (e.g., AAV-Sia6e for cochlear cells) [23]. |

| Genotyping Platform | Confirms the presence and purity of the desired edit. | Sanger sequencing for initial check; Targeted HTS for quantifying efficiency and bystander edits [20] [22]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter System | Enables functional screening for DN phenotypes via base editor scanning. | Used to sort cells based on activity of the targeted protein (e.g., DNMT3A reporter) [22]. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: ABE-NW1 Precise Base Editing Workflow

Diagram 2: Dominant-Negative Mechanism & Specificity Challenge

Designing Functional Assays That Reflect Biological Environment

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Addressing Lack of Specificity in Hox Dominant-Negative Experiments

Problem: The dominant-negative Hox protein produces unexpected phenotypic changes or no phenotypic effect, suggesting potential off-target interactions or lack of specific activity.

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Investigation Question | Methodology & Validation Approach | Key Parameters to Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Does the dominant-negative construct disrupt the correct Hox protein complex? | Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by Western Blot to assess interaction with native dimerization partners (e.g., PBC, Meis) [25]. | Presence/absence of partner proteins in the IP complex [25]. |

| 2 | Is the DNA-binding specificity altered? | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) to compare DNA binding of wild-type Hox complex vs. complex with dominant-negative protein [25]. | Shift in DNA probe mobility; specificity via cold竞争 inhibition [25]. |

| 3 | Is there a change in the transcriptional output of key target genes? | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) on known downstream target genes. Compare effects to wild-type and loss-of-function models [26] [27]. | Fold-change in mRNA expression of validated target genes [26]. |

| 4 | Does the phenotypic effect match known Hox loss-of-function transformations? | Morphological analysis (e.g., skeletal staining in vertebrates, cuticle preparation in Drosophila) for homeotic transformations [27] [25]. | Presence of homeotic transformations (e.g., anteriorization of vertebrae) [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Optimizing Assay Systems to Better Mimic Native Hox Environment

Problem: The in vitro or cellular assay system fails to replicate the complexity of the native biological environment where Hox genes function, leading to results that do not translate to whole-organism models.

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Investigation Question | Methodology & Validation Approach | Key Parameters to Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Does the cellular model express the necessary co-factors? | RNA-Seq or RT-qPCR to profile expression of known Hox co-factors (e.g., PBC, Meis) and other Hox paralogs in the cell line used [25]. | Confirmation of expression of essential co-factor transcripts [25]. |

| 2 | Is the chromatin context representative of the native state? | Use a reporter assay with a native, chromatin-embedded promoter versus a minimal promoter to test for specificity [26]. | Transcriptional activity (e.g., luciferase units) from the native promoter construct [26]. |

| 3 | Are we using an adequate number of biological replicates? | Perform a power analysis before the experiment to determine the sample size needed to detect the expected effect size, based on pilot data or published studies [28]. | Statistical power (typically aimed for 80%); within-group variance [28]. |

| 4 | Does the assay account for functional redundancy from Hox paralogs? | Use CRISPR/Cas9 to generate cell lines lacking multiple Hox paralogs (e.g., Hoxa11, Hoxd11) to isolate specific function [27]. | Phenotypic severity (e.g., limb malformation) in single vs. multiple paralog knockout [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the critical positive and negative controls for a Hox dominant-negative functional assay?

Answer: Including the correct controls is fundamental for interpreting the results of a dominant-negative experiment.

Control Experiments Table:

| Control Type | Purpose | Recommended Protocol | Expected Outcome for a Valid Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type Hox Protein | To confirm the assay can detect normal transcriptional activity. | Co-transfect the reporter plasmid with a wild-type Hox protein expression vector [25]. | Strong activation or repression of the reporter gene. |

| Empty Vector / Scrambled Protein | To account for non-specific effects of protein overexpression. | Co-transfect the reporter plasmid with the empty expression vector (or vector for a scrambled peptide). | Baseline level of reporter activity. |

| Validated Loss-of-Function Model | To show the dominant-negative phenotype resembles a known null phenotype. | Compare results to a CRISPR knockout or RNAi knockdown of the endogenous Hox gene [27]. | Dominant-negative phenotype should mimic the loss-of-function phenotype (e.g., homeotic transformation). |

| Specificity Control (Different Hox Protein) | To test for off-target effects on a non-cognate DNA element. | Test the dominant-negative protein on a reporter for a different Hox gene's target. | Minimal to no effect on the non-cognate reporter. |

FAQ 2: How can I validate that my functional assay is "well-established" and reflects the true biological environment?

Answer: The ClinGen Variant Curation Expert Panels (VCEPs) have established that "well-established" functional assays must be analytically sound and reflect the biological environment [29]. The following validation framework is recommended.

Assay Validation Parameters Table:

| Validation Parameter | Key Considerations for Hox Assays | Example Metrics & Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| Robustness & Reproducibility | The assay should produce consistent results across technical and biological replicates [29] [28]. | Intra-assay CV < 15%; Inter-assay CV < 20%; successful replication in an independent lab. |

| Specificity | The assay should measure the specific function of the Hox protein and not be confounded by paralogs or related pathways [25]. | >80% inhibition of target gene expression with dominant-negative; minimal effect on non-target genes. |

| Sensitivity | The assay should detect clinically or biologically relevant changes in function (e.g., loss-of-function vs. gain-of-function) [29]. | Ability to distinguish wild-type from known pathogenic variants (positive controls). |

| Biological Relevance | The assay system should encompass necessary cellular components (co-factors, chromatin) and reflect the in vivo pathophysiology [29]. | Strong correlation (e.g., r > 0.7) between assay results and phenotypic severity in animal models. |

FAQ 3: Our cell-based assay shows a strong effect, but we see no phenotype in our mouse model. What could be wrong?

Answer: This common issue often stems from a failure of the cell-based system to capture the complexity of the whole organism.

Potential Causes and Solutions Table:

| Potential Cause | Investigation Strategy | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Redundancy | Check expression patterns of Hox paralogs in the relevant mouse tissue. Generate double or triple knockout mice to uncover redundancy [27]. | Target multiple Hox paralogs simultaneously (e.g., Hoxa11 and Hoxd11) to observe a phenotype [27]. |

| Insufficient Expression | Confirm dominant-negative protein expression in vivo via Western blot or immunohistochemistry in the target tissue. | Use a stronger or tissue-specific promoter to drive higher expression of the transgene. |

| Compensatory Mechanisms | Perform RNA-Seq on wild-type and transgenic mouse tissue to identify dysregulated pathways or unexpected gene expression changes. | Analyze earlier developmental time points before compensation occurs. |

| Incorrect Biological Replicates | Ensure that each transgenic mouse is an independent biological replicate, not a pseudoreplicate from the same litter or injection [28]. | Increase the number of independent transgenic lines or founders analyzed [28]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for Hox-DNA Binding Specificity

Purpose: To visually confirm and characterize the binding of Hox protein complexes to a specific DNA sequence and test how a dominant-negative protein disrupts this binding [25].

Key Steps:

- Prepare Components: Incubate purified wild-type Hox protein (or complex with co-factors PBC/Meis) with a radiolabeled or fluorescently-labeled DNA probe containing the cognate binding site.

- Set Up Competition Reactions:

- Specific Competition: Add excess unlabeled ("cold") identical probe. The labeled complex should be reduced.

- Non-specific Competition: Add excess unlabeled probe with a mutated sequence. The labeled complex should not be reduced.

- Introduce Dominant-Negative: Include a reaction where the dominant-negative protein is added to the wild-type complex before adding the DNA probe.

- Run Gel: Separate the protein-DNA complexes from the free DNA via non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

- Visualize: Analyze the gel for shifted bands. A successful dominant-negative should disrupt or "supershift" the wild-type complex [25].

Protocol 2: Reporter Gene Assay in a Chromatin Context

Purpose: To measure the transcriptional outcome of Hox protein activity on a target gene promoter in a more native, chromatinized environment.

Key Steps:

- Clone Reporter: Clone a native, genomic promoter region (approximately 1-3 kb upstream of the transcription start site) of a validated Hox target gene into a luciferase reporter vector.

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect this reporter construct into an appropriate cell line (e.g., C2C12 for limb-related Hox genes) along with:

- Wild-type Hox expression vector.

- Dominant-negative Hox expression vector.

- Empty vector control.

- Measure Activity: After 24-48 hours, lyse the cells and measure luciferase activity. Normalize to a co-transfected control (e.g., Renilla luciferase).

- Interpretation: The dominant-negative should significantly reduce the transcriptional activity driven by the native promoter compared to the wild-type control [26].

Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Hox Protein Complex Formation and Disruption

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for conducting Hox dominant-negative functional assays.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in Hox Assays |

|---|---|

| Hox Expression Plasmids | Mammalian expression vectors for wild-type and dominant-negative (e.g., lacking DNA-binding domain) Hox genes; used for transfection in reporter assays [25]. |

| PBC/Meis Expression Vectors | Vectors expressing essential Hox co-factors; required to reconstitute a functional Hox protein complex in vitro or in cell-based assays [25]. |

| Validated Hox Reporter Cell Lines | Stable cell lines containing luciferase or GFP reporters under the control of authentic Hox target gene promoters (e.g., from limb bud or hindbrain) [26]. |

| Anti-Hox & Co-factor Antibodies | Validated antibodies for Western Blot, Immunohistochemistry, and Co-Immunoprecipitation to confirm protein expression and complex formation [25]. |

| Hox Target Gene qPCR Assays | Pre-validated TaqMan or SYBR Green primer-probe sets for quantitative measurement of endogenous Hox target gene expression [26]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Kits | Tools to generate Hox and co-factor knockout cell lines, essential for testing specificity and functional redundancy [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical parameters to validate for an immunoassay, and what are the recommended thresholds? For any immunoassay, a full validation should investigate key parameters to ensure the results are reliable and reproducible. The table below summarizes the core parameters, their definitions, and common acceptance criteria based on established guidelines [30].

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Recommended Threshold or Investigation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent test results [30]. | Measure via repeatability (within-run) and intermediate precision (between-run, e.g., different days/analysts). Report as Coefficient of Variation (%CV). |

| Trueness | Closeness of agreement between the average value from a large series of results and an accepted reference value [30]. | Assess by measuring % recovery of a known standard or reference material. |

| Limits of Quantification (LOQ) | The highest and lowest concentrations of an analyte that can be reliably measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [30]. | Determine the lowest concentration that can be measured with a %CV ≤ 20% (or a predefined value relevant to the assay's intended use). |

| Dilutional Linearity | Demonstrates that a sample above the measuring range can be diluted to fall within the range and still yield a reliable result [30]. | Dilute a high-concentration sample and demonstrate that measured concentrations are within ±15–20% of the expected value. |

| Parallelism | The relative accuracy from recovery tests on the biological matrix diluted against the calibrators in a substitute matrix [30]. | Dilute a native sample with high analyte concentration and show the results are parallel to the standard curve. |

| Robustness | The ability of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [30]. | Test small changes in critical steps (e.g., incubation times ±5%, temperatures ±2°C). Measured concentrations should not be systematically altered. |

| Selectivity/Specificity | The ability of the method to measure and differentiate the analyte in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present [30]. | Test for interference by spiking potential interfering substances (e.g., related proteins, lipids) and check for cross-reactivity. |

2. How many experimental replicates are sufficient for a robust assay? The number of replicates depends on the required precision and the assay's intended use. For key experiments, a minimum of three independent biological replicates (distinct samples) is standard, each with at least two technical replicates (repeated measurements of the same sample) to account for procedural variability [30]. For high-throughput screening, statistical power analysis can determine the optimal number, but increasing replicates enhances result reliability, especially for assays with higher inherent variability.

3. What types of controls are essential for interpreting dominant-negative experiments in Hox research? Proper controls are critical to confirm that an observed phenotype is due to the specific dominant-negative (DN) mechanism. The table below outlines the essential controls for these experiments.

| Control Type | Purpose in Dominant-Negative Experiments | Expected Result for Valid DN Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type Hox Protein | Baseline for normal protein function. | Shows normal activity or phenotype. |

| Empty Vector/Scramble | Controls for non-specific effects of transfection/transduction. | Shows baseline activity, identical to untreated cells. |

| Loss-of-Function (LOF) Mutant | Controls for simple loss of protein function (haploinsufficiency). | Shows a partial or weak phenotype compared to the DN mutant. |

| Full-Knockout/KD | Represents a complete loss of function. | Phenotype should differ from the DN mutant, which is often more severe. |

| Rescue Control | Confirms specificity by expressing a wild-type protein alongside the DN mutant. | Should partially or fully reverse the DN mutant's phenotype. |

4. My Hox dominant-negative experiment shows no phenotype. What could be wrong? A lack of phenotype could stem from several issues. Troubleshoot using the following steps:

- Verify Protein Expression: First, confirm that your dominant-negative Hox protein is being expressed at the expected levels using Western blot or immunofluorescence.

- Check Mutant Stability: A common issue is that the DN mutant is too destabilizing. DN mutations should not be highly destabilizing, as the mutant protein must be stable enough to co-assemble with the wild-type protein and "poison" the complex [3]. Use a protein stability predictor or check the literature to ensure your mutation is not a severe LOF.

- Confirm Complex Formation: The dominant-negative effect typically requires the mutant subunit to interact with the wild-type partner. Use co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) to verify that your mutant Hox protein still interacts with its wild-type counterpart and/or essential co-factors like TALE proteins [31].

- Review Control Experiments: Ensure your positive controls (e.g., a known effective DN construct) are working and that your assay is sensitive enough to detect the phenotypic change.

5. How can I distinguish a dominant-negative effect from a gain-of-function effect? Distinguishing between these mechanisms requires careful experimental design. The flowchart below outlines the key logical steps for differentiation.

6. What are the key methodological considerations for validating a binding assay for Hox-cofactor complexes? Validating these assays requires a focus on specificity and the cooperative nature of Hox binding [31].

- Use Relevant DNA Motifs: Hox proteins often bind DNA cooperatively with TALE cofactors (e.g., Pbx, Meis). Your assay should use DNA probes containing both the Hox core motif (e.g., TAAT) and the adjacent TALE cofactor binding site [31].

- Include Cofactor Proteins: The binding specificity and affinity can change dramatically in the presence of cofactors. Perform EMSA or SPR assays with Hox proteins alone, cofactors alone, and the Hox-cofactor combination to demonstrate cooperative complex formation.

- Validate with Mutant Controls: Include mutant DNA probes (with scrambled or inactive binding sites) and mutant Hox/cofactor proteins (e.g., with altered DNA-binding domains) to demonstrate binding specificity.

- Determine Apparent Kd: Use techniques like isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to quantify the binding affinity, which will be significantly stronger for the cooperative complex compared to individual components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions for investigating Hox proteins and dominant-negative mechanisms.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Hox/Dominant-Negative Research |

|---|---|

| TALE Cofactor Proteins (Pbx, Meis) | Essential binding partners for many Hox proteins. Used in EMSA, Co-IP, and functional assays to study cooperative DNA binding and complex formation [31]. |

| Plasmids for Wild-Type and Mutant Hox Genes | For expressing Hox proteins in cells. Critical for creating DN mutants (e.g., at protein interfaces [3]) and LOF controls. |

| Antibodies (Anti-Hox, Anti-Tag, Anti-TALE) | Used for detecting protein expression (Western blot), localization (immunofluorescence), and protein interactions (Co-IP). |

| Validated DNA Probes | Double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing the specific Hox-TALE binding sites (e.g., with TAAT core) for use in EMSA or reporter assays [31]. |

| Structure Prediction Software (e.g., FoldX) | Used to model the structural impact of mutations. DN mutations typically have milder effects on protein stability than LOF mutations and are enriched at protein interfaces [3]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Provide a human cell model to study Hox gene function in differentiation and patterning, potentially offering more accurate disease modeling than animal models [32]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Dominant-Negative Hox Mutant

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to confirm the function and mechanism of a putative dominant-negative Hox protein.

1. Objective To confirm that a Hox protein variant acts via a dominant-negative mechanism by inhibiting the function of its wild-type counterpart, and not merely through a loss-of-function.

2. Materials and Reagents

- Expression plasmids for Wild-Type (WT) Hox, Dominant-Negative (DN) Hox mutant, and Loss-of-Function (LOF) Hox mutant.