Overcoming the Cellular Diversity Gap in Organoid Models: Strategies for Enhanced Physiological Relevance

Organoid technology has revolutionized biomedical research by providing three-dimensional, self-organizing models that mimic human organs.

Overcoming the Cellular Diversity Gap in Organoid Models: Strategies for Enhanced Physiological Relevance

Abstract

Organoid technology has revolutionized biomedical research by providing three-dimensional, self-organizing models that mimic human organs. However, a significant limitation hindering their full translational potential is their often limited cellular diversity, typically lacking key components like immune cells, vasculature, and nerves. This article addresses this critical challenge by exploring the foundational causes of this limitation, detailing advanced methodological solutions such as co-culture systems and organ-on-chip technologies, providing troubleshooting and optimization strategies for improved reproducibility, and validating these enhanced models against traditional systems. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cutting-edge approaches to build more physiologically complete organoids, thereby advancing their application in disease modeling, drug discovery, and personalized medicine.

The Cellular Diversity Problem: Why Basic Organoids Fall Short

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is the absence of vasculature a critical limitation in organoid technology? Organs such as the kidney, brain, and heart are highly vascularized in the body. The lack of vasculature in organoids prevents adequate nutrient and oxygen diffusion, leading to the formation of a necrotic core in larger organoids and failing to recapitulate essential physiological interactions, such as waste filtration in kidney glomeruli [1].

What are the primary methods for vascularizing organoids? The main strategies include in vivo engraftment into immunodeficient host models, co-culturing organoids with endothelial cells (ECs) or mesodermal progenitor cells (MPCs), and using genetic engineering to direct cells within the organoid toward an endothelial fate [1] [2].

How can I incorporate immune cells into my organoid model? The most common technique is to establish a co-culture system where organoids are cultured with specific immune cells, which can be either immortalized cell lines or autologous immune cells derived from patients [1].

My patient-derived tissue sample cannot be processed immediately. What is the best way to preserve it for organoid generation? For short-term delays (≤6-10 hours), wash the tissue with an antibiotic solution and store it at 4°C in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with antibiotics. For longer delays (>14 hours), cryopreservation is recommended. Wash the tissue and cryopreserve it in a freezing medium (e.g., 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium). Note that a 20-30% variability in live-cell viability can be expected between these two methods [3].

What are the advantages of using Mesodermal Progenitor Cells (MPCs) to create complex organoids? MPCs can differentiate into multiple cell lineages, including endothelial cells (forming vascular networks) and smooth muscle cells (providing vessel support). They can also give rise to Iba1+ immune cells, such as microglia-like cells in neural organoids, thereby providing vasculature and stromal components simultaneously [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Organoid Growth and Central Necrosis

- Potential Cause: Inadequate vascularization, leading to insufficient nutrient and oxygen delivery to the organoid's core.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Mesodermal Progenitor Cells (MPCs): Mix MPCs with your organoid-forming cells in a 1:1 ratio. Culture the aggregates under pro-angiogenic conditions (e.g., 2% O₂) to promote an evenly distributed vascular network [2].

- Co-culture with Endothelial Cells: Directly co-culture your organoids with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or similar endothelial cells to initiate vessel formation [1].

- Consider In Vivo Engraftment: For ultimate maturation and vascularization, engraft organoids into an immunodeficient mouse model (e.g., NSG mice) at sites like the kidney capsule or cranial window, which allows host vasculature to invade the organoid [1].

Problem: Failure to Model Immune-Mediated Diseases or Drug Responses

- Potential Cause: The organoid model lacks resident or circulating immune cells, making it unsuitable for studying inflammation, infection, or immunotherapy.

- Solution:

- Establish an Immune Co-culture System: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or specific immune cell subtypes (e.g., T cells) from the same patient. Introduce these cells into the organoid culture medium to create an epithelial-immune co-culture [1].

- Utilize MPC-Based Models: When generating organoids with MPCs, monitor for the development of Iba1+ macrophage/microglia-like cells that can infiltrate the tissue, providing a native immune component [2].

Problem: Low Viability or Organoid Formation Efficiency from Patient Tissue

- Potential Cause: Delays in processing or improper handling of the surgically resected patient tissue.

- Solution:

- Minimize Processing Time: Transfer samples to cold, antibiotic-supplemented medium immediately after collection and process as quickly as possible [3].

- Choose the Right Preservation Method: Adhere to the guidelines for short-term refrigerated storage versus cryopreservation based on your expected processing delay to maximize cell viability [3].

- Use a ROCK Inhibitor: When thawing or passaging cryopreserved organoids, include a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) in the culture medium for the first few days to reduce anoikis and improve cell survival [4].

Experimental Protocols

This protocol describes how to create vascularized tumor or neural organoids by incorporating mesodermal progenitor cells.

1. Materials

- Cell Sources: hiPSCs, human tumor cell line (e.g., MDA-MB-435s), or neural spheroids.

- Induction Medium: For MPC induction from hiPSCs: use a medium containing the GSK3β-inhibitor Chir99021 and BMP4.

- Culture Vessels: Suspension culture plates (e.g., low-adhesion 6-well plates).

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM): Matrigel or similar ECM hydrogel.

- Hypoxia Chamber: For culture at 2% O₂.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Differentiation of Mesodermal Progenitor Cells (MPCs) from hiPSCs

- Culture hiPSCs in a standard maintenance medium.

- To induce MPCs, switch to an induction medium supplemented with Chir99021 and BMP4.

- Culture for 3 days. Monitor for the loss of pluripotency markers and the appearance of Brachyury+ cells (approximately 80% by day 2).

Part B: Formation of Vascularized Organoids

- For Tumor Organoids: Mix induced MPCs with GFP-labelled tumor cells in a 1:1 ratio.

- For Neural Organoids: Generate Sox1+ neural spheres and Brachyury+ MPC spheres separately, then bring them into co-culture to allow fusion.

- Culture the resulting aggregates in suspension.

- To promote uniform vascular network distribution, transfer the cultures to a hypoxic environment (2% O₂) for several days.

- Maintain the organoids in suspension culture on a rocking plate for long-term studies (up to 280 days).

3. Validation and Analysis

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for CD31 (PECAM-1) to confirm endothelial network formation and α-Smooth Muscle Actin (αSMA) to identify pericytes/smooth muscle cells in the vessel wall.

- Electron Microscopy: Use TEM to confirm the ultrastructure of formed vessels, including lumen formation, endothelial cell-cell junctions, and basement membrane.

Table 1: Comparison of Strategies to Address Missing Cell Types in Organoids

| Strategy | Methodology | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Engraftment [1] | Transplantation of organoids into immunodeficient mice (e.g., kidney capsule, cranial window). | Provides a natural, functional host vasculature; leads to enhanced organoid maturation. | Technically challenging; introduces host variables; less suitable for high-throughput screening. |

| Co-culture with MPCs [2] | Incorporation of mesodermal progenitor cells into the organoid during formation. | Generates a complex, hierarchically organized human vascular network; can also yield microglia-like cells. | Requires additional differentiation step for MPCs; network organization may require hypoxia. |

| Co-culture with Specific Immune Cells [1] | Introduction of immortalized or patient-derived immune cells into the organoid culture. | Enables study of specific epithelial-immune interactions (e.g., in cancer or infection). | Lack of standardized protocol; may not fully recapitulate the native immune niche. |

| Genetic Engineering [1] | Gene editing (e.g., CRISPR) to manipulate cells within organoids to adopt an endothelial fate. | Endothelial cells are intrinsic and autologous to the organoid. | Can be inefficient; requires sophisticated technical expertise. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Complex Organoid Generation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Matrigel [4] | An undefined extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogel that provides a 3D scaffold for organoid growth and self-organization. | Used as the core scaffold for embedding organoids in "dome" cultures. |

| Chir99021 [2] | A GSK3β inhibitor that activates Wnt signaling, crucial for inducing mesodermal progenitor cells (MPCs) from pluripotent stem cells. | Key component in MPC induction medium. |

| BMP4 [2] | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4, a growth factor that favors lateral plate mesodermal fate, guiding MPCs toward vascular lineages. | Used in combination with Chir99021 for MPC induction. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) [4] | Improves cell survival after dissociation and thawing by inhibiting apoptosis (anoikis). | Added to culture medium for the first 2-3 days after thawing or passaging organoids. |

| Noggin [3] | A BMP signaling pathway antagonist, often used in intestinal and colon organoid media to promote epithelial growth. | Standard component of many complete organoid culture media. |

| R-spondin Conditioned Medium [3] | Contains R-spondin protein, a potent activator of Wnt signaling, essential for stem cell maintenance in many epithelial organoids. | Used in colon, esophageal, and pancreatic organoid media formulations. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Vascularization via MPCs Workflow

Immune Cell Co-culture Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary limitations of the self-organizing nature of organoids? The self-organization of organoids, while powerful, leads to several key technical challenges for researchers:

- Heterogeneity and Variability: The stochastic nature of self-assembly results in significant batch-to-batch differences in organoid size, cellular composition, and structure, making it difficult to draw consistent conclusions [5] [6].

- Limited Maturity: Most organoids model a fetal or early developmental stage rather than a mature adult organ. They often lack key cell types, such as immune cells, vascular cells, and nerves, which limits their physiological relevance [5] [7] [6].

- Necrotic Core Formation: Without a functional vascular network, nutrients and oxygen cannot diffuse into the center of larger organoids. This leads to hypoxia and cell death in the core, limiting the organoid's lifespan and size [5] [7] [6].

FAQ 2: Why is Standard Matrigel a problem for advanced organoid research? Matrigel, the ubiquitous matrix derived from mouse sarcomas, presents major hurdles for reproducible and clinically relevant science:

- Batch-to-Batch Variability: Its complex and undefined composition varies from lot to lot, introducing an uncontrollable variable that compromises experimental reproducibility [8] [9].

- Animal-Derived Origin: Being derived from mouse tumors, it contains xenogenic components and growth factors that limit the translational potential of findings for human therapies and can trigger unwanted immune responses in co-culture models [8] [9].

- Limited Control: Its natural composition makes it difficult to engineer or tune specific biochemical and mechanical properties to guide organoid development in a precise manner [10].

FAQ 3: How can limited cellular diversity in organoid models be addressed? Strategies to enhance cellular diversity focus on engineering the microenvironment and incorporating missing components:

- Co-culture Systems: Introducing other cell types, such as endothelial cells to form vasculature or immune cells, can help recapitulate a more complex tissue environment [6].

- Engineered Matrices: Using defined, synthetic, or human-derived hydrogels allows for the precise incorporation of adhesion motifs and growth factors to guide the differentiation and organization of multiple cell types [8] [10].

- Assembloids: Fusing organoids of different regional identities (e.g., cortical and thalamic) can model complex cell-cell interactions and circuit formation that are absent in single organoids [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Heterogeneity and Poor Reproducibility in Organoid Cultures

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Solution and Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in organoid size and shape between batches. | Stochastic self-assembly; manual cell seeding and handling. | Automate processes. Use robotic liquid handling systems for consistent cell seeding, media changes, and differentiation protocols [5]. |

| Inconsistent cellular composition and differentiation outcomes. | Uncontrolled initial conditions (cell number, matrix concentration). | Standardize protocols. Precisely control the initial stem cell number and ECM-to-cell ratio. Use validated, assay-ready organoid models where available [6]. |

| Batch-to-batch differences despite identical protocols. | Variability in critical reagents, especially Matrigel. | Implement quality control. Use single-cell RNA sequencing to validate cellular composition. Transition to defined, animal-free hydrogels to eliminate Matrigel variability [6] [8]. |

Issue 2: Limited Organoid Growth and Necrotic Core Formation

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Solution and Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Cell death in the organoid center after reaching a certain size. | Lack of vascularization; limited nutrient and oxygen diffusion. | Improve nutrient access. Culture organoids in bioreactors with agitation or use the slice culture method to increase surface area and permeability [5] [7]. |

| Organoids fail to grow beyond a small diameter. | Hypoxia and metabolic waste accumulation. | Promote vascularization. Co-culture with endothelial cells to encourage rudimentary vessel formation [6]. |

| Inability to deliver substances to the organoid interior. | Absence of a perfusable vascular network. | Integrate with Organ-Chips. Use microfluidic devices to fluidically link organoids, providing perfusion and mechanical cues that can enhance maturation and function [5] [6]. |

Issue 3: Incomplete Maturity and Functionality

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Solution and Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Organoids exhibit fetal, not adult, characteristics. | Missing physiological cues from the native microenvironment. | Provide external stimulation. Apply relevant mechanical forces (e.g., stretch, flow), electrical stimulation, or co-culture with supporting mesenchymal cells [5]. |

| Absence of key functional responses (e.g., electrical activity, secretion). | Lack of specific mature cell types or neuronal innervation. | Extend culture time and use patterning factors. Optimize protocols for long-term culture and incorporate small molecules to promote specific regional identities and advanced maturation [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Reproducibility

Protocol 1: Establishing a Defined, Animal-Free Culture System for Vascular Organoids

This protocol replaces murine Matrigel with a human-derived, defined matrix system, enhancing translational potential and reproducibility [8].

1. Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit)

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Vitronectin XF | A recombinant human protein coating for 2D iPSC culture; supports feeder-free, xeno-free expansion and maintains pluripotency. |

| Fibrinogen | A human plasma protein; forms the structural basis of the 3D hydrogel when combined with thrombin. |

| Thrombin | An enzyme that catalyzes the polymerization of fibrinogen to form a fibrin hydrogel. |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | Basal medium for organoid culture. |

| Essential Growth Factors | Including EGF, FGF, and BMP for directing vascular differentiation. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

- 2D hiPSC Culture and Maintenance:

- Culture human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) on Vitronectin-coated plates in defined mTeSR or equivalent medium.

- Passage cells upon reaching 70–80% confluency using a gentle enzyme-free method.

- Quality Control: Verify pluripotency by immunostaining for markers like Nanog and OCT3/4 [8].

- Differentiation Initiation and 3D Embedding:

- Begin directed differentiation toward mesoderm by changing to a specific differentiation medium.

- On day 13, harvest the differentiating cell aggregates.

- Prepare Fibrin Gel: Mix cells with a solution of fibrinogen and thrombin to initiate polymerization. Plate the mixture in droplets and incubate to form a solid gel.

- Overlay the gel with vascular differentiation medium.

- Culture and Maturation:

- Culture the vascular organoids for 18-21 days, with medium changes every 2-3 days.

- Functional Validation: Analyze sprouting behavior under a brightfield microscope. Confirm endothelial (CD31) and mural cell (PDGFRβ) identity via flow cytometry and whole-mount immunostaining [8].

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Patient-Derived Colorectal Organoids

A standardized guide for generating organoids from colorectal tissues, addressing common pitfalls from sample collection to culture [3].

1. Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit)

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | Transport and wash medium; preserves tissue integrity. |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Antibiotic supplement to prevent microbial contamination. |

| L-WRN Conditioned Medium | Source of Wnt3a, R-spondin, and Noggin; critical for intestinal stem cell growth. |

| Matrigel (or Alternative) | Basement membrane extract for 3D support (transition to defined hydrogels is recommended). |

| DMSO | Cryoprotectant for freezing cells and tissues. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow & Troubleshooting

- Tissue Procurement and Processing:

- Action: Collect human colorectal tissue samples (normal, polyp, or tumor) and immediately place them in cold Advanced DMEM/F12 with antibiotics.

- Critical Step/Troubleshooting: Process samples within 6-10 hours. If delayed, use one of two methods:

- Short-term storage (<14h): Wash tissue with antibiotics and store at 4°C in DMEM/F12 with antibiotics.

- Long-term storage (>14h): Cryopreserve tissue in a freezing medium (e.g., 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in L-WRN medium).

- Data: A 20–30% variability in live-cell viability is observed between these preservation methods. Cryopreservation is preferred for long delays [3].

- Crypt Isolation and Seeding:

- Action: Mechanically and enzymatically dissociate the tissue to isolate crypts. Mix the crypt suspension with Matrigel or an alternative hydrogel and plate as droplets.

- Troubleshooting: Low organoid formation efficiency is often due to poor initial cell viability. Adhere strictly to the recommended processing timelines and use high-growth factor concentration media for tumor samples.

- Long-Term Culture and Analysis:

- Action: Culture in IntestiCult or similar organoid growth medium. Passage organoids when they become large and dense.

- Troubleshooting: To avoid necrotic cores, do not let organoids grow too large before passaging [11]. For functional analysis like drug screening, consider generating "apical-out" organoids for direct access to the luminal surface [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Organoid Preservation Methods for Colorectal Tissues [3]

| Preservation Method | Processing Delay | Estimated Cell Viability Impact | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refrigerated Storage (4°C) | ≤ 6-10 hours | Lower impact (baseline) | Same-day or next-morning processing in the same lab. |

| Cryopreservation | > 14 hours | 20-30% reduction in viability | Long-term storage or when transport to a remote lab is required. |

Table 2: Functional Characterization of Animal-Free Vascular Organoids vs. Matrigel Controls [8]

| Characterization Metric | Matrigel-Based Organoids | Vitronectin/Fibrin-Based Organoids | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Marker (OCT4) Expression | Baseline (High in iPSCs, downregulated during differentiation) | No significant difference | Vitronectin supports normal exit from pluripotency. |

| Mesoderm Marker (TWIST) Expression | Baseline | No significant difference | Normal developmental progression. |

| Surface Area (by Brightfield) | Baseline | No significant difference | Similar growth and size characteristics. |

| Endothelial Cell Content (CD31+ by FACS) | Baseline | No significant difference | Successful differentiation of endothelial lineage. |

| Mural Cell Content (PDGFRβ+ by FACS) | Baseline | No significant difference | Successful differentiation of supportive mural cells. |

The Diversity Gap in Organoid Research: Quantifying the Problem

The limited genetic diversity in biomedical research, often called the "diversity gap," presents a significant challenge for accurately modeling human diseases and predicting drug responses. The table below summarizes the quantitative evidence of this disparity and its documented impact on research outcomes.

Table 1: Evidence and Impact of Limited Diversity in Biomedical Models

| Aspect of Diversity Gap | Quantitative Evidence | Impact on Research & Healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Ancestry in Genomic Studies [12] | Most Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) are predominantly based on European ancestry populations. | Impedes the development of accurate Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) for underrepresented populations, exacerbating health disparities. |

| Sex-Based Differences [12] | Significant disparities exist in disease susceptibility, treatment efficacy, and drug toxicity between sexes. | Drug metabolism, immune response, and disease prevalence data become skewed without sex-stratified analyses. |

| Drug Trial Failure Rate [6] | The clinical trial failure rate exceeds 85%, partly due to safety and efficacy concerns not predicted by non-diverse models. | High costs and slow progress in drug development; released drugs may have unforeseen, population-specific adverse effects. |

Scientific Foundations: How Limited Diversity Skews Biological Data

Limited diversity in model systems introduces bias at multiple biological levels, compromising the translational value of research.

- Disease Modeling Fidelity: Organoids derived from a narrow genetic background fail to capture the full spectrum of disease manifestations. For instance, certain monogenic disorders like cystic fibrosis and Alagille syndrome have been modeled using patient-derived organoids, revealing how different mutations lead to variable clinical outcomes [13]. Restricting models to a single haplotype overlooks this critical variability.

- Drug Response Prediction: Genetic ancestry and biological sex are critical factors influencing drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity [12]. A drug screened on organoids from a limited genetic background may show efficacy but could be ineffective or harmful in a genetically distinct population. Integrating donor-specific organoids from diverse backgrounds into early drug discovery can help identify these population-specific drug responses [12] [6].

- Cellular Complexity and Maturity: The diversity challenge is not only inter-donor but also intra-organoid. Many organoid models, particularly those derived from Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs), often exhibit a fetal phenotype that is inappropriate for studying adult-onset diseases [6]. Furthermore, the common lack of key tissue-specific cell types, such as immune cells, vasculature, and nerves, creates an oversimplified system that does not fully recapitulate the tissue microenvironment [13] [6].

Researcher's Toolkit: Protocols for Enhancing Diversity in Organoid Models

A. Establishing a Diverse Organoid Biobank

Creating a biobank from healthy and diseased donors with varying genetic backgrounds is a fundamental step [12] [6]. The workflow for establishing such a biobank from colorectal tissues, which can be adapted for other organs, is detailed below.

Protocol: Generating Patient-Derived Colorectal Organoids [3]

Tissue Procurement and Initial Processing:

- Collect human colorectal tissue samples (cancerous, pre-cancerous polyps, or normal) from surgical resections or colonoscopies under IRB-approved protocols and informed consent.

- Critical Step: Transfer samples in cold Advanced DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with antibiotics to preserve tissue integrity. Process immediately or preserve using validated methods.

- For short-term delays (≤6-10 hours): Wash tissue with antibiotic solution and store at 4°C in DMEM/F12 medium with antibiotics.

- For longer delays (>14 hours): Cryopreserve tissue using a freezing medium (e.g., 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium).

Crypt Isolation and Culture Initiation:

- Mechanically and enzymatically digest the tissue to isolate crypts or single cells.

- Centrifuge to pellet the cells/crypts and resuspend in a cold, liquid extracellular matrix (ECM) like Matrigel.

- Plate the cell-ECM suspension as small domes in a pre-warmed culture plate. Incubate at 37°C for 10-15 minutes to allow the ECM to solidify.

- Overlay the gel domes with pre-warmed complete organoid culture medium.

Culture Maintenance:

- Passage organoids every 1-2 weeks by mechanically and enzymatically breaking down the structures. Re-embed the fragments in fresh ECM for continued expansion.

B. Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Diverse Organoid Culture

| Reagent Category | Example Components | Function in Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Base Medium | Advanced DMEM/F12 | Provides essential nutrients and salts for cell survival and growth. |

| Niche Factors | EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor), R-spondin 1, Noggin | Mimics the in vivo stem cell niche; critical for stem cell maintenance and proliferation. EGF promotes growth, R-spondin amplifies Wnt signaling, and Noggin (a BMP inhibitor) prevents differentiation. |

| Supplements | B-27, N-Acetylcysteine, Nicotinamide, A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) | Provides antioxidants, supports cell health, and inhibits differentiation pathways to enable long-term expansion. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Matrigel, Cell Basement Membrane (e.g., ATCC ACS-3035) | Provides a 3D scaffold that mimics the native basement membrane, crucial for proper cell polarization and structure formation. |

| Conditioned Media | Wnt3A-conditioned medium, R-spondin1-conditioned medium | Supplies essential proteins that are difficult to purify or produce recombinantly, crucial for sustaining certain organoid types. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Question: Our organoid yields from patient tissues are low and variable. How can we improve reliability?

- Answer: Low yield is often a processing issue. Adhere strictly to these critical steps:

- Minimize Processing Delay: The time from surgery to culture initiation drastically impacts viability. Process tissues immediately or use a reliable preservation method [3].

- Choose the Right Preservation: For delays under 10 hours, refrigerated storage in antibiotic-supplemented medium is suitable. For longer delays, cryopreservation is superior, though a 20-30% drop in viability should be expected [3].

- Optimize Digestion: Titrate enzyme concentration and digestion time to avoid under- or over-digestion, which can kill stem cells.

Question: How can we make our organoid models more physiologically relevant for studying drug delivery and immune interaction?

- Answer: Standard organoids often lack key physiological features. To enhance relevance:

- Induce Apical-Out Polarity: Modify protocols to generate "apical-out" organoids, which expose the luminal surface. This allows direct access for studying drug permeability, host-microbiome interactions, and immune cell co-cultures [3].

- Incorporate Fluidic Flow: Integrate organoids with Organ-Chips (microfluidic devices). This provides dynamic fluid flow and mechanical cues, enhancing cellular differentiation, creating well-polarized architectures, and enabling co-culture with immune cells or microbes [6].

- Attempt Vascularization: Co-culture organoids with endothelial cells to encourage blood vessel formation. This can alleviate nutrient diffusion problems, increase organoid size limits, and provide a more realistic model for studying drug delivery [6].

Question: Our organoids show high batch-to-batch variability, affecting experimental reproducibility. What solutions are available?

- Answer: Variability is a major challenge. Implement these strategies:

- Standardize and Automate: Use liquid handling robots for consistent media preparation and organoid passaging. This reduces human error and operational variability [6].

- Use Defined Reagents: Where possible, transition from undefined components (like conditioned media) to recombinant proteins to improve batch consistency.

- Leverage AI and Assay-Ready Models: New solutions combine automation with AI to standardize protocols and remove human bias from cell culture decisions. Alternatively, source validated, "assay-ready" organoid models from commercial suppliers to ensure a consistent starting point for experiments [6].

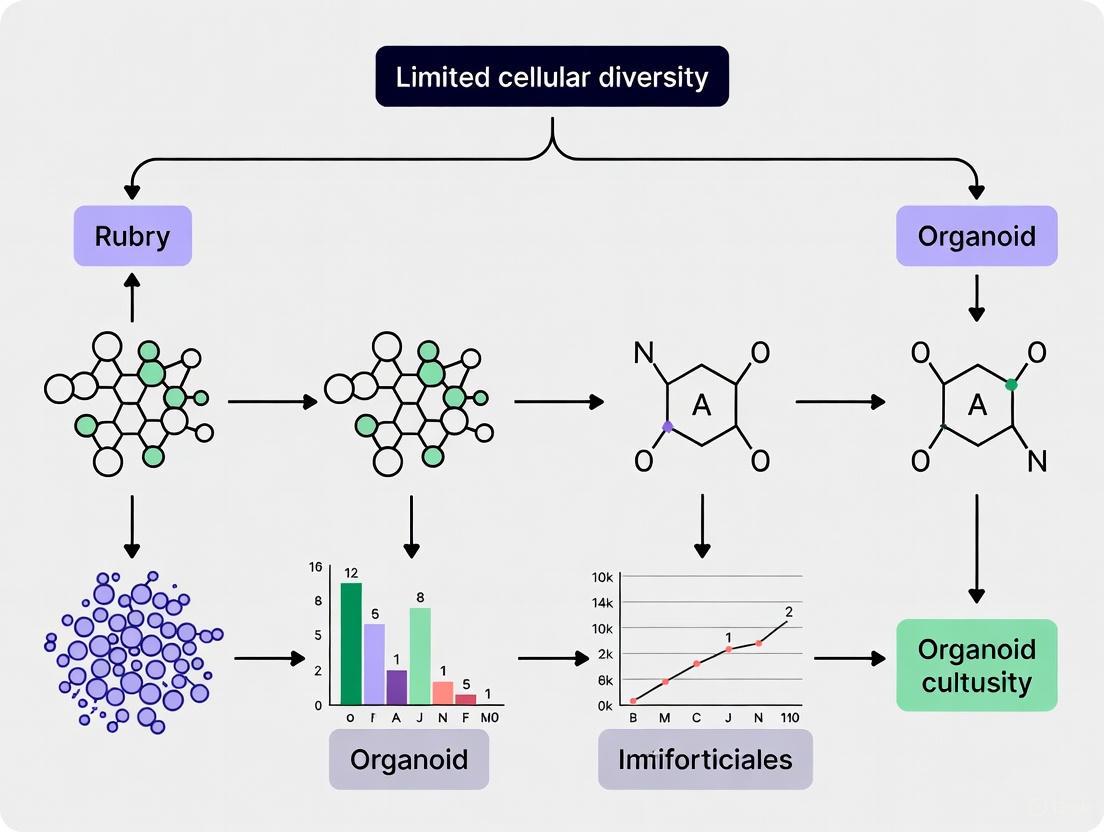

The following diagram summarizes the strategic approach to overcoming the diversity challenge in organoid research, from biobanking to advanced functional models.

A significant bottleneck in organoid research is the pervasive tendency for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived organoids to arrest at a fetal or early postnatal stage of development. Even after extended culture periods, these models often lack the cellular complexity, structural organization, and functional maturity characteristic of adult human organs. This "fetal phenotype" limitation severely constrains their utility in modeling adult-onset diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders and many metabolic conditions, and reduces the predictive accuracy of drug screening campaigns [5] [14]. This technical support article delineates the core challenges and provides targeted troubleshooting guidance to help researchers advance organoid maturation.

The fundamental hurdle lies in the inadequacy of the standard in vitro environment to replicate the intricate cues of in vivo development. While organoids can initiate self-organization, the spontaneous and stochastic nature of this process often fails to progress fully without engineered intervention. Key missing elements include functional vascular networks for nutrient exchange, integrated immune cells, appropriate biomechanical forces, and sustained hormonal signaling [5]. Consequently, organoids frequently exhibit hypoxia-driven central necrosis, an underdeveloped extracellular matrix, and an immature transcriptomic profile that more closely resembles a fetal, rather than an adult, organ [14]. The following sections provide a structured framework to diagnose and address these specific issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My brain organoids develop a necrotic core after long-term culture. How can I improve their health and longevity?

- Problem: The formation of a necrotic core is a classic sign of insufficient nutrient and oxygen diffusion, a direct result of lacking a perfusable vascular network. This hypoxia not only causes cell death but also disrupts normal developmental gradients and limits organoid size [5] [14].

- Solutions:

- Co-culture with Endothelial Cells: Introduce human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or iPSC-derived endothelial cells during organoid formation. These cells can self-assemble into tube-like structures, enhancing nutrient delivery [14] [15].

- Induce Vascularization Genetically: Genetically engineer your iPSC line to overexpress pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF-A to encourage the formation of host-derived vasculature [16].

- Use Bioreactors: Culturing organoids in spinning bioreactors can improve medium circulation around the tissue, reducing diffusion barriers and promoting more uniform growth [16] [14].

- In Vivo Transplantation: Transplanting organoids into a mouse brain can facilitate vascularization by the host, leading to enhanced maturation and survival [15].

FAQ 2: How can I assess whether my organoids have reached a mature state?

- Problem: The field lacks universally standardized maturity metrics, leading to fragmented assessments and difficulties in cross-study comparisons [14].

- Solutions: Implement a multimodal assessment framework that goes beyond simple morphological inspection.

- Structural Analysis: Use immunofluorescence for deep-layer (TBR1, CTIP2) and upper-layer (SATB2) neuronal markers in brain organoids to confirm cortical layering. Electron microscopy can validate ultrastructural features like mature synapses with pre- (SYB2) and post-synaptic (PSD-95) densities [14].

- Functional Assays: Employ multi-electrode arrays (MEAs) to record synchronized neuronal network activity, such as gamma-band oscillations, which are a hallmark of mature circuits. Patch-clamp electrophysiology can detail the electrophysiological properties of individual neurons [14].

- Molecular Profiling: Conduct single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to compare the transcriptomic profile of your organoids against public databases of human fetal and adult brain tissue. This can quantitatively reveal the developmental stage of your model [14].

FAQ 3: How can I reduce the high heterogeneity and variability between organoid batches?

- Problem: The self-organizing nature of organoids introduces inherent variability in size, cellular composition, and structure, which can compromise experimental reproducibility [5].

- Solutions:

- Standardize Initial Conditions: Precisely control the initial cell number and aggregation method. Using microwell arrays or microfluidic devices can generate uniformly sized embryoid bodies, the starting point for organoids [5] [15].

- Incorporate Bioengineering Tools: Utilize organoids-on-chips platforms. These microfluidic devices provide precise control over the microenvironment, including the spatiotemporal delivery of morphogens, which guides more consistent patterning [5].

- Automate Culture Processes: Implement robotic liquid handling systems for tasks like media changes and passaging. This minimizes manual handling errors and increases protocol consistency [5].

FAQ 4: What strategies can I use to introduce missing cell types, like microglia or vascular cells?

- Problem: Many standard organoid protocols generate models that lack critical non-epithelial or non-neuronal cell populations, such as the immune and vascular systems, limiting their physiological relevance [5] [15].

- Solutions:

- Assembloid Approach: Differentiate iPSCs separately into different organoid types (e.g., cortical organoids and microglia organoids) and then fuse them together to create a more complex "assembloid." This is effective for modeling interactions between brain regions and between neurons and microglia [15].

- Co-culture from the Start: Add pre-differentiated microglia or endothelial cells at the beginning of the organoid formation process, allowing them to integrate during self-organization. For example, co-culturing brain organoids with induced vascular organoids can lead to the formation of a functional blood-brain barrier [15].

Key Maturity Assessment Metrics

To systematically evaluate the success of maturation protocols, researchers should quantify a combination of structural, functional, and molecular parameters. The table below summarizes key benchmarks for brain organoids, which can be adapted for other organ types.

Table 1: Multidimensional Assessment of Brain Organoid Maturity

| Assessment Dimension | Key Metrics & Markers | Technical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Architecture | Cortical layering (SATB2, TBR1); Synaptic density (PSD-95, SYB2); Myelination (MBP) | Immunofluorescence (IF), Immunohistochemistry (IHC), Confocal Microscopy, Electron Microscopy [14] |

| Cellular Diversity | Presence of astrocytes (GFAP, S100β); Oligodendrocytes (O4, MBP); Microglia (IBA1) | IF, IHC, Flow Cytometry, scRNA-seq [14] |

| Functional Maturation | Synchronized network bursts; Gamma-band oscillations; Postsynaptic currents | Multi-electrode Arrays (MEA), Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology, Calcium Imaging [14] |

| Molecular & Metabolic Profile | Transcriptomic similarity to adult human tissue; Metabolic activity | scRNA-seq, RNA Sequencing, Metabolic Flux Assays [14] |

Experimental Protocols to Enhance Maturation

Protocol 1: Generating a Vascularized Brain Organoid via Co-culture

This protocol outlines the steps for fusing a brain organoid with a vascular organoid to create a vascularized assembloid.

- Workflow Diagram:

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Generate Brain Organoids: Differentiate your iPSC line into region-specific (e.g., cortical) brain organoids using a established protocol, typically involving neural induction with dual SMAD inhibition [15].

- Generate Vascular Organoids: In parallel, differentiate a separate batch of iPSCs into vascular organoids using a medium supplemented with VEGF (50-100 ng/mL) and BMP4 (25-50 ng/mL) to promote endothelial and perivascular cell fates [15].

- Fusion (Assemblation): At a predetermined stage (e.g., day 30-40), manually transfer one brain organoid and one vascular organoid into a single well of a low-adhesion 96-well plate. Allow them to contact each other and fuse over 24-48 hours in a minimal medium.

- Maturation Culture: Transfer the fused assembloid to a spinning bioreactor or an orbital shaker for long-term culture (≥60 days) to enhance nutrient exchange and support further maturation. Supplement the medium with factors that support both neural and vascular cell types.

- Validation: Confirm vascular network integration and functionality via immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (endothelial cells) and PDGFRβ (pericytes), and assess barrier properties with dextran permeability assays [14] [15].

Protocol 2: Active Bioengineering Acceleration Using Electrical Stimulation

Applying extrinsic physical cues can mimic in vivo activity and drive functional maturation.

- Workflow Diagram:

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Preparation: Generate brain organoids using your standard protocol and pre-culture them to a baseline stage of neural competency (e.g., day 60).

- Setup: For stimulation, consider embedding organoids in a conductive hydrogel (e.g., containing graphene or polypyrrole) to enhance charge delivery. Place the organoid-hydrogel construct onto a multi-electrode array (MEA) plate.

- Stimulation Regimen: Apply a chronic, low-intensity electrical stimulation protocol. A sample regimen is a biphasic pulse at 100 Hz for 2 hours per day over a period of 2-4 weeks. The specific parameters (frequency, duration, amplitude) should be optimized for your system [14].

- Real-time Monitoring: Use the same MEA system to periodically record electrophysiological activity throughout the stimulation period. Look for progressive increases in spike rate, burst frequency, and network synchronization complexity.

- Endpoint Analysis: After the stimulation period, fix the organoids for immunohistochemical analysis of synaptic markers (e.g., PSD-95) and glial maturation (e.g., GFAP), or process them for transcriptomic analysis [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Maturation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix (Matrigel) | Provides a 3D scaffold mimicking the basal membrane; contains laminins, collagen, and growth factors. | Standard embedding matrix for supporting organoid growth and structure [16] [4]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves cell survival after passaging and thawing by inhibiting apoptosis. | Add to medium for 24-48 hours after thawing cryopreserved organoids or after enzymatic dissociation [4]. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors (VEGF, BDNF) | Directs cell fate and maturation. VEGF promotes vascularization; BDNF supports neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity. | VEGF is used in vascular organoid protocols. BDNF can be added in later stages of neural culture to enhance maturation [14] [15]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (e.g., A83-01) | A TGF-β receptor inhibitor that supports the growth of epithelial stem cells by preventing differentiation. | Common component in many culture media for gastrointestinal, hepatic, and pancreatic organoids [4]. |

| Multi-Electrode Arrays (MEAs) | Non-invasive platforms for long-term, electrophysiological monitoring of functional neural network activity. | Used to record spontaneous and evoked electrical activity from brain organoids to quantify functional maturity [14]. |

Engineering Complexity: Advanced Techniques to Build Better Organoids

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How can we improve the success rate of co-culturing tumor organoids with immune cells? The success of co-culture models depends on carefully replicating the natural stem cell niche. This involves using an optimized extracellular matrix (ECM), such as Matrigel, and a serum-free medium supplemented with essential growth factors. The specific combination and concentration of these factors—including EGF, Noggin, R-spondin-1, and Wnt3a—vary depending on the tumor type being cultured [17] [3]. Furthermore, the cellular components must be prepared correctly. For immune cells, a common approach involves using peripheral blood lymphocytes or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients [17]. For Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs), they can be isolated from tissue like colorectal liver metastases and are sometimes immortalized using lentiviral constructs encoding hTERT and BMI1 to extend their lifespan and improve experimental reproducibility [18].

2. What are the common signs of contamination in co-culture systems, and how can they be addressed? Contamination can manifest as sudden turbidity in the culture medium, unexpected pH shifts, or altered cell growth patterns [19]. Bacterial contamination often leads to rapid cell death and visible turbidity, while fungal contamination appears as filaments or spores under the microscope [19]. Mycoplasma contamination is more insidious, as cultures may appear normal while cell metabolism and gene expression are disrupted [19]. To address this, dispose of compromised cultures immediately and decontaminate equipment and workspaces thoroughly [19]. Prevention strategies include maintaining a strict cleaning schedule for incubators and biosafety cabinets, using dedicated reagent aliquots, and conducting routine mycoplasma testing [19].

3. Why is there little passage of liquid factors through the filter in a horizontal co-culture system? Insufficient passage of liquid factors through a filter in a co-culture plate can often be traced to two main issues. First, if the culture volume is too low, the area of the filter contacting the culture solution is reduced, significantly diminishing the co-culture effect [20]. Second, air can remain trapped in the pores of the filter, blocking the passage of factors. To resolve this, ensure the filter is properly pre-processed by washing with pure water and PBS after a one-minute treatment with 100% ethanol, and that it is sufficiently degassed before use [20].

4. What critical roles do tumor organoid-immune cell co-culture models play in advancing cancer diagnosis and treatment? These co-culture models serve as a powerful platform for personalized drug screening and the study of immunotherapy. They can be used to enrich tumor-reactive T cells from a patient's blood and assess their cytotoxic efficacy against the patient's own tumor organoids [17]. This provides a method to evaluate tumor cell sensitivity to T cell attack on an individual level, offering a theoretical basis for developing more effective immunotherapies and personalizing treatment plans [17].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Poor or Uncontrolled Cellular Organization in Co-culture

- Potential Cause: Lack of a proper foundational matrix that supports spontaneous cellular reorganization.

- Solution: Use an optimized ECM. Co-cultures of colon cancer organoids and CAFs embedded in a defined ECM can spontaneously form superstructures where collagen IV from CAFs creates a basement membrane, supporting the cancer cells in forming glandular structures that mimic in vivo histology [18].

Problem 2: Low Cell Viability in Co-culture

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal culture medium that does not support all cell types present.

- Solution: Adapt established organoid media to also support the growth of other cells, such as CAFs. Testing medium conditions with a cell viability assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo 3D) can help identify the most suitable formulation [18].

Problem 3: Loss of Key Microenvironment Features in Long-Term Culture

- Potential Cause: Rapid loss of non-epithelial cells (like CAFs and immune cells) from traditional organoid cultures, leading to a loss of the mesenchymal phenotype and associated immunosuppressive signals.

- Solution: Employ robust, long-term co-culture systems. One study demonstrated that co-culturing colon cancer organoids with immortalized CAFs maintained a gene expression signature associated with aggressive, immunosuppressive cancer subtypes (like CMS4) and produced high levels of immunosuppressive factors such as TGFβ1, VEGFA, and lactate [18].

Problem 4: Low Success Rate in Establishing Patient-Derived Organoids

- Potential Cause: Delays in tissue processing or improper handling after collection, which reduce cell viability.

- Solution: Process tissue samples promptly. If same-day processing is not possible, use interim cold storage (6-10 hours with antibiotics in media at 4°C) or cryopreservation in an appropriate freezing medium (e.g., containing 10% FBS, 10% DMSO, and 50% L-WRN conditioned medium). Note that a 20-30% variability in live-cell viability can be expected between these two preservation methods [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents and their functions in establishing co-culture systems.

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Co-culture System |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Matrigel, Collagen I, Collagen IV | Provides a 3D structural scaffold for cell growth and organization; Collagen IV is specifically produced by CAFs to form a basement membrane [17] [18]. |

| Essential Growth Factors | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin-1, Wnt3a, FGF | Creates a stem cell niche that supports the self-renewal and expansion of organoids and other cells; specific combinations are required for different tumor types [17] [3]. |

| Cell Culture Media | Advanced DMEM/F12, CAF Medium, Organoid Medium | Serves as the base nutrient medium; specialized formulations (e.g., serum-free CAF medium) are needed to support different cell populations in co-culture [3] [18]. |

| Cell Isolation Enzymes | Liberase TH | Digests tumor tissue for the isolation of primary cells, such as Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) [18]. |

| Cryopreservation Medium | FBS, DMSO, L-WRN Conditioned Medium | Preserves tissue samples or established cell lines for long-term storage and future use, maintaining cell viability [3]. |

Experimental Workflow for Establishing a Co-culture Model

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in creating a co-culture system that integrates tumor organoids, fibroblasts, and immune cells.

Key Protocols and Methodologies

1. Protocol for Establishing Patient-Derived Organoids from Colorectal Tissue [3]

- Tissue Procurement: Collect human colorectal tissue samples under sterile conditions immediately after colonoscopy or surgical resection. Transport in cold Advanced DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with antibiotics.

- Processing: Mechanically dissociate and enzymatically digest the tumor sample to obtain a cell suspension.

- 3D Culture: Seed the cell suspension onto a biomimetic scaffold like Matrigel. Use a growth factor-reduced medium supplemented with a specific cocktail of factors (e.g., EGF, Noggin, R-spondin-1) to minimize clone selection and support organoid growth.

- Cryopreservation: For long-term storage, cryopreserve tissue or organoids using a freezing medium such as 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium.

2. Protocol for Isolating and Immortalizing Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) [18]

- Isolation: Cut colorectal liver metastasis tissue into small pieces and digest using Liberase TH for 30 minutes at 37°C. Plate the cell suspension in a dish; after 30 minutes, wash away non-adherent cells. The adherent cells are CAFs, which are then cultured in a specialized CAF medium.

- Immortalization: To extend lifespan, immortalize low-passage primary CAFs (P1-P3) by transducing them with lentiviral constructs encoding hTERT and BMI1. Culture the transduced CAFs on a thin collagen coat.

3. Functional Assay: Assessing Immunosuppressive Capacity of Co-cultures [18]

- Conditioned Media Collection: Collect media from established co-cultures of tumor organoids and CAFs.

- T Cell Proliferation Assay: Use this conditioned media in a T cell proliferation assay. A potent inhibition of T cell proliferation indicates that the co-culture system is successfully recapitulating an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, a hallmark of aggressive cancer subtypes like CMS4 colon cancer.

Signaling Pathways in the Co-culture Microenvironment

The diagram below outlines the key signaling interactions between tumor cells, CAFs, and immune cells in a co-culture system.

Organoids, which are self-organizing three-dimensional (3D) cellular models derived from pluripotent stem cells, have become an invaluable tool for studying human development and disease. However, their utility is tempered by inherent limitations, including limited cellular diversity, lack of high-fidelity cell types, and limited maturation, which can restrict their reliability for modeling complex biological systems [7]. A key challenge is that traditional organoids form stochastic structures without external guidance and often fail to capture the dynamic interactions between different cell lineages and tissue regions that are crucial for physiological function [21] [22].

Assembloid technology has emerged as a transformative approach to bridge this gap. Assembloids are defined as self-organizing 3D systems formed by integrating multiple organoids or combining organoids with specialized cell types [22] [23]. This innovative platform enables researchers to model inter-tissue communication and inter-organ communication with greater physiological relevance, thereby addressing the critical limitation of cellular diversity in traditional organoid cultures. By recapitulating interactions between distinct tissue domains, assembloids provide deeper insights into tissue function and open new avenues for studying human development, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development [24] [22].

Fundamental Concepts: Assembly Strategies and System Design

Categorization of Assembloid Approaches

The design of assembloid models can be systematically categorized into four primary assembly strategies, each engineered to replicate specific biological phenomena with high fidelity [23]:

- Multi-region assembloids: Combine organoids representing different brain regions or tissue compartments to study long-range interactions, such as thalamocortical pathways or forebrain interneuron migration [22] [25].

- Multi-lineage assembloids: Integrate cell types derived from different germ layers to model interactions between distinct lineages, such as neural crest cell migration or interactions between epithelial and mesenchymal components [22] [23].

- Multi-gradient assembloids: Incorporate spatial concentration gradients of signaling molecules to guide patterning and cell fate specification, mimicking developmental processes [23].

- Multi-layer assembloids: Stack or arrange different tissue layers to replicate the complex architecture of stratified organs or interfaces, such as the vascular-neural barrier [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful assembloid generation relies on a core set of research reagents and engineered materials. The table below details key components and their functions in assembloid protocols.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Assembloid Generation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Protocol Context |

|---|---|---|

| Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs) | Foundational starting cell population for generating all organoid components; enables patient-specific disease modeling. | Used across all protocols; requires confirmation of chromosomal stability before organoid generation [21]. |

| Small Molecules & Growth Factors | Guide regional-specific differentiation by activating or inhibiting key developmental signaling pathways. | Wnt activators, Smad inhibitors, Retinoic Acid (RA), Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) agonists for patterning spinal motor neurons [21]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Components | Provide 3D structural support and biochemical cues that promote cell survival, polarization, and self-organization. | Matrigel or other hydrogel systems; functionalized with Sulfo-SANPAH for covalent binding to device surfaces [21]. |

| Surface Modification Reagents | Create geometrically defined adhesion patterns to guide tissue morphogenesis and prevent nonspecific adhesion. | Pluronic-127 (hydrophilic barrier), Sulfo-SANPAH (heterobifunctional crosslinker) [21]. |

| Functional Assessment Tools | Enable real-time monitoring and quantification of functional integration and circuit activity. | Genetically encoded calcium indicators, microelectrode arrays, optogenetic actuators [21] [26]. |

Technical Guide: Protocols, Methodologies, and Troubleshooting

Detailed Protocol: Generating Human Motor Assembloids-on-a-Chip

This protocol leverages geometric engineering to create spatially patterned human motor assembloids, which model the neuromuscular junction [21].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Generation of Motor Neuron Spheroids (hMNS):

- Differentiate hiPSCs using a guided protocol with sequential addition of specific signaling molecules [21].

- Days 1-5: Treat with a Wnt activator and dual Smad inhibitors to induce neuroepithelial clusters. Confirm emergence of PAX6+, PAX7+, NESTIN+, and NEUROD1+ progenitor cells.

- Days 5-10: Add RA and SHH agonists while decreasing Wnt signaling to confer ventral identity. Verify generation of OLIG2+/NKX6.1+ motor neuron progenitors (MNPs) via immunofluorescence and qPCR. These MNPs can be passaged and cryopreserved at this stage.

- Days 16+: Enhance maturation with γ-secretase inhibitors and neurotrophic factors for at least 8 days. By day 24, confirm presence of mature motor neuron markers (ISL1, HB9, ChAT) and electrophysiological activity.

- Harvest MNP colonies and transfer to ultra-low attachment plates to form spheroids (target diameter: 250 ± 50 μm).

Device Fabrication and Surface Patterning:

- Fabricate a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) device featuring micro-patterns with semicircular endpoints to mimic natural muscle anchoring points [21].

- Critical Surface Modification:

- Treat the middle region of the device with Pluronic-127 to create a hydrophilic barrier that prevents nonspecific cell adhesion.

- Functionalize the semicircular anchoring points with the heterobifunctional crosslinker Sulfo-SANPAH. Upon UV photolysis, Sulfo-SANPAH covalently binds to the PDMS surface and subsequently links to ECM proteins in the culture, creating stable adhesion sites.

Generation of Anisotropic Skeletal Muscle Organoids (hSkM) and Assembly:

- Seed a cell-laden biomatrix (e.g., primary myoblasts or hiPSC-derived myogenic progenitors) into the pre-treated PDMS device.

- The middle tissue will progressively detach from the Pluronic-treated region and contract toward the functionalized anchoring points. Within 14 days, this process forms aligned myobundles along the anchoring axis.

- Place 3-4 pre-formed hMNS evenly distributed within the hSkM-containing device to promote integration.

Maturation and Functional Validation:

- Culture the assembloids for 3-5 weeks to allow for robust neuromuscular junction formation.

- Validate functional connectivity using a combination of optogenetics, microelectrode array mapping, and calcium imaging [21].

Detailed Protocol: Generating a Human Ascending Somatosensory Assembloid (hASA)

This advanced protocol integrates four distinct regional organoids to model the polysynaptic sensory pathway from the periphery to the brain [26].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Parallel Generation of Four Regional Organoids:

- Human Cortical Organoids (hCO) and Human Diencephalic Organoids (hDiO): Generate using established guided differentiation protocols with small molecules and growth factors [26].

- Human Dorsal Spinal Cord Organoids (hdSpO): Modify ventral spinal cord protocols by excluding ventralizing cues to promote dorsal identity. Confirm presence of HOXB4+ and PHOX2A+ projection neurons via immunostaining and scRNA-seq.

- Human Somatosensory Organoids (hSeO): Develop using a protocol that leverages neural crest differentiation cues. Validate by confirming a substantial population of POU4F1+/SIX1+ sensory neurons and SOX10+/FOXD3+ neural crest cells. Confirm expression of key sensory receptors (P2RX3, TRPV1) and functional responses to their specific agonists (α,β-methyleneATP, capsaicin) via calcium imaging.

Sequential Assembly:

- Fuse the generated organoids in a sequence that reflects the native biological pathway: hSeO → hdSpO → hDiO → hCO.

- This can be achieved by placing the organoids in close proximity in low-attachment wells or using supportive hydrogels to encourage natural migration and axonal projection between regions.

Circuit Validation and Functional Analysis:

- Connectivity Mapping: Use modified rabies virus tracing to demonstrate monosynaptic connectivity from sensory neurons to dorsal spinal cord neurons, and subsequently to thalamic neurons.

- Functional Response: Apply noxious chemical stimuli (e.g., capsaicin) to hSeO while performing multi-region calcium imaging to record coordinated neuronal activity across the entire assembloid.

- Synchrony Assessment: Use extracellular recordings and imaging to detect synchronized oscillatory activity across the four-component circuit. Pathogenic variants (e.g., in SCN9A/NaV1.7) can disrupt this synchrony, providing a readout for circuit-level dysfunction [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Technical Questions

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using assembloids over co-culture systems or single organoids?

- Assembloids provide a modular yet integrated system that recapitulates the spatial organization and functional connectivity between distinct tissue regions or cell lineages. Unlike simple co-cultures, they support complex processes like cell migration, axon pathfinding, and synaptic integration within a 3D environment, offering a more physiologically relevant model for studying inter-cellular communication [22] [23].

Q2: How can I improve the reproducibility and reduce heterogeneity in my assembloid models?

- Incorporating bioengineering tools is key. Using geometrically engineered microdevices with defined surface chemistry, as in the motor assembloid-on-a-chip platform, standardizes tissue morphology and organization [21]. Furthermore, employing automated liquid handling systems for cell seeding, media changes, and differentiation factor addition can significantly minimize batch-to-batch variability [5].

Q3: My assembloids show poor cell viability in the core over time. What can I do?

- This is a common issue due to diffusive limitations. Strategies include:

- Reducing organoid size to ensure adequate oxygen and nutrient perfusion.

- Transitioning to slice culture, where assembloids are sectioned and maintained at an air-liquid interface, greatly improving viability in the internal regions [7] [5].

- Integrating vascularization strategies, either by incorporating endothelial cells during organoid formation or using microfluidic "organ-on-a-chip" platforms to enhance convective transport [5].

- This is a common issue due to diffusive limitations. Strategies include:

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Assembloid Generation and Culture Problems

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution & Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or Failed Fusion | Organoids are not in sufficiently close contact; Mismatched developmental stages; Incorrect regional identity. | - Use low-attachment 96-well plates with V-shaped bottoms to force contact.\n- Carefully synchronize the differentiation timelines of individual organoids.\n- Validate regional identity (e.g., via qPCR/immunostaining for key markers) prior to fusion. |

| Lack of Functional Connectivity | Insufficient maturation time; Absence of necessary trophic support. | - Extend the maturation period post-fusion (can require 8+ weeks for neural circuits).\n- Ensure media contains essential neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF, NT-3). |

| High Necrotic Core Formation | Limited diffusion of oxygen and nutrients into the 3D tissue mass. | - Culture assembloids in smaller sizes (<500 μm ideal).\n- Implement a slice culture methodology.\n- Use bioreactors or orbital shaking for improved medium perfusion. |

| Detachment from Microdevice | Inadequate or failed surface modification. | - Follow the surface pretreatment protocol strictly: ensure Pluronic-127 creates a non-adhesive middle region and Sulfo-SANPAH properly functionalizes the anchoring points [21]. A troubleshooting guide specific to the device is essential. |

| High Batch-to-Batch Variability | Stochastic self-organization; Manual protocol inconsistencies. | - Adopt engineered approaches (e.g., geometric confinement) to guide morphology.\n- Standardize cell seeding numbers and ECM composition.\n- Implement automated systems for reagent dispensing where possible [5]. |

Assembloid technology represents a significant leap forward in our ability to model the complex interactions that underlie human development, physiology, and disease. By providing a platform to integrate multiple cell types and tissue regions in a single, self-organizing system, assembloids directly address the critical challenge of limited cellular diversity in traditional organoid cultures. As demonstrated by their application in modeling intricate systems like the neuromuscular junction and the multi-synaptic sensory pathway, assembloids offer unprecedented insights into emergent properties that arise from inter-tissue communication [21] [26].

The future of assembloid research will likely focus on overcoming current limitations, such as enhancing vascularization to support larger and more mature tissues, improving cellular fidelity to better match in vivo counterparts, and incorporating immune cells and other stromal components to create even more holistic models [7] [5]. Furthermore, the integration of assembloids with advanced functional readouts, such as high-density electrophysiology and multi-omics profiling, will solidify their role as an indispensable platform for accelerating discovery in basic research and therapeutic development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How can I introduce physiologically relevant mechanical forces, such as breathing motions, into my airway organoid culture?

Answer: Integrating mechanical stretch requires a chip design that incorporates flexible membranes and controlled actuation. A specialized airway-on-chip protocol uses a multi-layer microfluidic device with a porous flexible membrane made of PDMS [27]. Applying cyclic vacuum suction to side chambers adjacent to the cell culture chamber mimics breathing motions. This setup can be combined with dynamic fluid flow (0.02-0.1 µL/s) to simulate perfusion [27].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Inconsistent or non-uniform membrane stretching.

- Solution: Ensure the PDMS membrane and device layers are of uniform thickness. Verify the vacuum pressure is stable and evenly distributed across the side chambers. Using a computer-controlled pneumatic system improves reproducibility.

- Problem: Cell death or detachment under flow and stretch conditions.

- Solution: Start with lower flow rates and strain amplitudes (e.g., 5% linear stretch) and gradually increase to physiological levels (e.g., 10%) over several days to allow cells to acclimate [27].

FAQ 2: What is the best way to connect different tissue compartments to model organ interactions while maintaining tissue-specific microenvironments?

Answer: A successful connection requires a recirculating common media circuit that links discrete compartments. A user-friendly approach involves a 3D-printed multi-compartment chip coupled with a tubing-free impeller pump [28]. This design allows separate tissue samples (e.g., lymph node and an injection site) to be housed in individual, accessible compartments while being connected via a shared, recirculating flow.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Rapid degradation of soluble signals or insufficient concentration to elicit a response.

- Solution: Minimize the volume of the common media reservoir to increase the concentration of secreted factors. Use a pump that provides complete media recirculation to allow factors to accumulate [28].

- Problem: Cross-contamination of cells between compartments.

- Solution: Incorporate micro-engineered physical barriers or porous membranes (with pore sizes typically 0.4-8 µm) between compartments to allow molecular crosstalk while containing cells [29] [30].

FAQ 3: My organoid cultures in the chip lack maturity and key functional markers compared to in vivo tissue. What factors should I optimize?

Answer: Limited maturation often stems from an underdeveloped microenvironment. Beyond simple perfusion, you must incorporate organ-specific mechanical cues and complex 3D extracellular matrices (ECM).

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Absence of polarization and mature mucociliary function in airway models.

- Solution: Apply a combination of perfusion, airflow, and cyclic stretch. Studies show this triple stimulation significantly accelerates mucociliary maturation, enhances polarization, and reduces baseline inflammatory secretion compared to static cultures [27].

- Problem: Poor structural organization and viability.

- Solution: Use natural hydrogels (e.g., Collagen, Matrigel) as ECM supports to provide essential biochemical cues [29] [31]. Optimize the channel geometry and flow rate using computational fluid dynamics models to ensure uniform nutrient and oxygen delivery [29].

FAQ 4: My microfluidic device is made from PDMS, but I'm concerned about small hydrophobic molecules being absorbed from the culture medium. What are my alternatives?

Answer: This is a known limitation of PDMS. Several strategies exist:

- Surface Coating: Treat PDMS surfaces with inert coatings like Parylene C to create a barrier that prevents absorption [28].

- Alternative Materials: Use thermoplastic polymers like PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) or COP (cyclic olefin polymer), which are less absorptive and suitable for mass production [32].

- Advanced 3D Printing: Fabricate chips from PEGDA (poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate) resins, which are biocompatible and do not suffer from the small molecule absorption issue [28].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Establishing a Biomimetic Airway-on-Chip with Perfusion and Mechanical Stretch

This protocol details the creation of an airway epithelium model that incorporates dynamic flow and breathing motions to accelerate maturation [27].

1. Chip Fabrication and Preparation:

- Materials: PDMS elastomer kit, vacuum-compatible membrane (e.g., flexible PDMS membrane), photo or soft lithography equipment for microfabrication [27].

- Procedure:

- Fabricate a multi-layer microfluidic device featuring a central cell culture channel, a porous flexible membrane, and two adjacent vacuum channels.

- Sterilize the assembled chip via autoclaving or UV irradiation.

- Coat the central membrane with a solution of human Collagen IV (e.g., 25 µg/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C to promote cell adhesion.

2. Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Materials: Primary human bronchial epithelial cells, differentiation media (e.g., PneumaCult-ALI medium).

- Procedure:

- Seed cells at a high density (e.g., 1-3 x 10^6 cells/cm²) onto the coated membrane.

- Allow cells to adhere under static conditions for 12-24 hours.

- Initiate perfusion of culture media at a low flow rate (0.02 µL/s) in the apical channel to create an air-liquid interface (ALI), removing the apical medium after 24-48 hours.

- Once confluent, apply cyclic mechanical stretch (10% linear strain, 0.15 Hz frequency) to simulate breathing using a computer-controlled vacuum system.

- Culture under these dynamic conditions for 3-4 weeks, with media changes every 2-3 days.

3. Functional Readouts for Maturation:

- Mucociliary Clearance: Track the movement of fluorescent beads placed on the epithelial surface.

- Cilia Beat Frequency: Measure using high-speed video microscopy.

- Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER): Monitor regularly with microelectrodes to confirm barrier integrity.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1), ciliated cells (β-tubulin), and goblet cells (MUC5AC).

Workflow Diagram: Establishing a Biomimetic Airway-on-Chip

Protocol: Connecting Lymph Node and Injection Site in a Multi-Compartment Platform

This protocol enables the study of systemic immune responses, such as acute reactions to vaccination, by fluidically linking different tissue types [28].

1. Platform Assembly:

- Materials: 3D printer (DLP type), MiiCraft Clear resin or custom PEGDA resin, Parylene C coater, DC motor, magnets, PLA filament for pump housing.

- Procedure:

- 3D Print the Chip and Pump: Fabricate the multi-compartment device and removable mesh supports using a DLP 3D printer with a biocompatible resin (e.g., PEGDA or ITX-PEGDA).

- Apply Parylene C Coating: Deposit a ~1 µm film of Parylene C onto all printed parts via gas-phase deposition to enhance biocompatibility.

- Assemble Impeller Pump: Construct the tubing-free magnetic impeller pump. The pump sits in a reservoir on the chip and is driven by an external motor with a rotating magnet.

2. Tissue Preparation and Loading:

- Materials: Murine lymph nodes, mock tissue (e.g., collagen gel), complete cell culture media.

- Procedure:

- Prepare fresh lymph node slices (200-300 µm thick) using a vibratome.

- Load each tissue sample into its respective 3D-printed mesh support within the device compartment.

- Place the impeller bar into the common media reservoir and assemble the chip.

3. System Operation and Analysis:

- Procedure:

- Place the assembled chip onto the external pump platform and start the motor to initiate recirculating flow.

- "Vaccinate" by introducing antigen into the upstream injection site compartment.

- Run the experiment for the desired duration (e.g., 24 hours).

- For analysis, simply remove the mesh supports containing the tissues for imaging, flow cytometry, or RNA sequencing.

Workflow Diagram: Multi-Compartment Lymph Node Chip Assembly

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Biomaterials for Organ-on-Chip Fabrication

| Biomaterial | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Challenges | Ideal Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS [33] [31] | Transparent, gas-permeable, easy to fabricate, low cytotoxicity. | Absorbs small hydrophobic molecules, can be difficult to sterilize for reuse. | General-purpose OoC, barrier models (e.g., gut, lung), models requiring optical clarity. |

| PEGDA [28] | Biocompatible, tunable mechanical properties, does not absorb small molecules. | Requires 3D printing expertise, may require surface coating for optimal cell adhesion. | Customizable, complex 3D architectures, multi-compartment chips. |

| Collagen [31] | Superior biocompatibility, enzymatic biodegradability, native cell-adhesion sites. | Lacks mechanical strength when hydrated, batch-to-batch variation. | Hydrogel matrices for 3D cell culture, Gut-on-a-Chip, Bone-on-a-Chip. |

| PMMA/COP [32] | High optical clarity, rigid, low absorption of small molecules, suitable for mass production. | Not gas-permeable, less flexible than PDMS, requires hot embossing/injection molding. | High-throughput screening chips, commercial-scale production. |

Table 2: Parameters for Simulating Physiological Mechanical Forces in OoCs

| Organ System | Mechanical Force | Typical In Vivo Value | Engineered OoC Parameters | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung/ Airway [27] | Cyclic Stretch (Breathing) | 10-15% linear strain | 5-10% linear strain, 0.15-0.3 Hz | Accelerated mucociliary maturation, reduced inflammatory signaling, proper polarization. |

| Vasculature [29] [32] | Fluid Shear Stress (Blood Flow) | 1-30 dyn/cm² | 0.5-20 dyn/cm² (controlled via channel geometry & flow rate) | Enhanced endothelial cell alignment, barrier function, and differentiation. |

| Intestine [29] | Peristalsis-like Motion & Flow | Rhythmic contractions | Cyclic deformation (e.g., 10-15%, 0.1-0.2 Hz) combined with flow | Improved villi formation, enhanced barrier integrity, and cell differentiation. |

| General (via Compression) [29] | Mechanical Compression | Varies by tissue (e.g., bone, cartilage) | Applied static or cyclic pressure via actuation | Mimics tissues that respond to compression loads. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for OoC Integration

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | The most common elastomer for soft lithography of microfluidic chips; transparent, gas-permeable, and flexible [33] [31]. | Used to fabricate the flexible membranes and main body of the breathing lung chip [27]. |

| PEGDA Resin (Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate) | A photopolymer resin for 3D printing custom, complex chip architectures with high biocompatibility [28]. | Used to create the multi-compartment chip and impeller for the lymph node-on-chip platform [28]. |

| Parylene C | A chemically inert, biocompatible polymer deposited as a thin, conformal coating via vapor phase. Prevents small molecule absorption and improves biocompatibility of 3D-printed parts [28]. | Used to coat 3D-printed PEGDA chips to ensure cell viability and prevent compound absorption during immune response studies [28]. |

| Natural Hydrogels (Collagen, Matrigel) | Provide a 3D extracellular matrix (ECM) environment that supports cell embedding, organoid growth, and complex tissue morphogenesis [29] [31]. | Collagen IV used to coat the airway chip membrane for cell adhesion. Collagen I used as a scaffold for 3D tissue models [27]. |

| Microfluidic Impeller Pump | Provides recirculating fluid flow without complex external tubing, enabling easy-to-use multi-tissue connectivity [28]. | The magnetic impeller pump drives common media circulation between the lymph node and injection site compartments [28]. |

| Porous Membranes | Create tissue-tissue interfaces (e.g., between epithelium and endothelium) to study barrier function, absorption, and trans-cellular transport [29]. | A porous PDMS membrane in the lung chip separates alveolar epithelial cells from microvascular endothelial cells [29]. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in Vascularized Organoid Generation

FAQ 1: Why is vascularization critical for advanced organoid models?