Post-Hybridization Wash Stringency Optimization: A Complete Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing post-hybridization wash stringency for in situ hybridization (ISH) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques.

Post-Hybridization Wash Stringency Optimization: A Complete Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing post-hybridization wash stringency for in situ hybridization (ISH) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details how precise control of temperature and salt concentration is critical for achieving high signal-to-noise ratios, accurate genotyping, and reliable detection of nucleic acid targets. The content explores methodological parameters, troubleshooting strategies, and validation approaches to enhance assay specificity and sensitivity in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Understanding Stringency: The Scientific Foundation of Post-Hybridization Washes

Core Principles FAQ

What is stringency in nucleic acid hybridization?

Stringency refers to the specificity of binding between a probe and its target nucleic acid sequence. High stringency conditions ensure that only perfectly complementary sequences form stable hybrids, while low stringency conditions allow some mismatched sequences to bind [1]. The balance between affinity (yield) and specificity is a central principle; conditions that favor tighter binding often correlate with increased off-target binding, making specificity a greater concern than sensitivity in many modern applications [2].

How do temperature and salt concentration affect stringency?

Temperature and salt concentration are the two primary factors controlling stringency. Their relationship is inverse [2] [1]:

- To increase stringency: Raise the temperature and lower the salt concentration. Higher temperatures disrupt hydrogen bonds in mismatched hybrids, while lower salt concentrations reduce hybrid stability by failing to shield the negative charges on the phosphate backbones of nucleic acids, increasing electrostatic repulsion [1].

- To decrease stringency: Lower the temperature and raise the salt concentration. This stabilizes duplexes, including those with mismatches [1].

What is the role of chaotropic salts in hybridization?

Chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine HCl, guanidine thiocyanate) play a dual role in sample preparation for hybridization assays. They destabilize hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces, leading to protein denaturation (including nucleases), and they disrupt the hydration shells of nucleic acids, facilitating their binding to silica matrices in purification columns [3]. It is crucial to wash them away thoroughly before hybridization, as residual salts can impede elution and lead to poor purity measurements (low A260/230 ratios) [3].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Probable Cause | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| High background noise | Incomplete removal of non-specifically bound probe during washes [4] [5]. | Increase stringency of post-hybridization washes (raise temperature, use low-salt buffer like 0.1X SSC) [5] [1]. For DNA probes, ensure formaldehyde is not used in washes [4]. |

| Low or no signal | Hybridization conditions too stringent: Excessively high temperature or low salt during hybridization [2] [5].Inadequate target accessibility: Insufficient digestion of proteins masking the target [4] [5]. | Re-optimize hybridization conditions (lower temperature, increase salt). Optimize Proteinase K or pepsin digestion concentration and time via titration [4] [5]. |

| Unexpected cross-hybridization | Probe binding to repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu, LINE elements) [5].Wash stringency too low to dissociate partially matched sequences [2]. | Add blocking DNA (e.g., COT-1 DNA) during hybridization [5]. Implement more stringent washes (raise temperature, lower salt concentration) [2] [1]. |

| Poor sample purity affecting hybridization | Residual salts or proteins from inefficient nucleic acid purification [6] [3]. | Add an extra ethanol wash step during purification. Ensure lysis is complete and use high-quality, fresh ethanol for wash buffers [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Post-Hybridization Stringency Wash Optimization

This protocol provides a methodology for determining the optimal post-hybridization wash conditions to maximize signal-to-noise ratio, a key aspect of thesis research on stringency optimization.

Materials and Reagents

- Hybridized samples (e.g., on membrane or slides).

- Sodium Saline Citrate (SSC) Buffer (20X stock): 3 M NaCl, 0.3 M trisodium citrate, pH 7.0.

- Water bath or heat block, temperature-adjustable (range 25°C to 80°C).

- Stringent Wash Buffer I: 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS.

- Stringent Wash Buffer II: 0.1X SSC, 0.1% SDS.

- Detection system appropriate for your probe label (e.g., streptavidin-HRP for biotin).

Procedure

- Pre-wash: Following hybridization, perform a brief rinse at room temperature with ~50 mL of SSC buffer to remove the hybridization solution.

- Primary Wash: Wash the samples with 50-100 mL of Stringent Wash Buffer I for 15 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Stringency Wash Titration: Divide the samples into several identical batches.

- Prepare multiple containers with Stringent Wash Buffer II.

- Incubate each sample batch in a separate container for 15 minutes, but vary the temperature of the wash across a defined range (e.g., 50°C, 55°C, 60°C, 65°C).

- Final Rinse: Briefly rinse all samples in a low-salt buffer at room temperature.

- Detection: Proceed with the standard detection protocol for your system.

Data Analysis

- Quantify the specific signal and background noise for each wash temperature.

- Calculate the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for each condition.

- Plot the SNR against the wash temperature. The temperature that yields the highest SNR is the optimal stringency for that specific probe-target pair.

Quantitative Data for Stringency Optimization

The following table summarizes key parameters and their quantitative effects based on experimental data from the literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Assay Parameters on Performance

| Parameter | Typical Range or Value | Effect on Assay | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Hybridization Wash Temperature | 55°C - 80°C [5] [1] | Critical for disrupting mismatched hybrids; higher temperatures increase specificity. | [5] [1] |

| Post-Hybridization Wash Salt (SSC) | 0.1X - 2X [5] [1] | Lower concentration (e.g., 0.1X) increases stringency by reducing duplex stability. | [5] [1] |

| Proteinase K Digestion (for ISH) | 1-5 µg/mL, 10 min @ RT [4] | Essential for target accessibility; requires titration to balance signal and morphology. | [4] |

| MP ddPCR Assay Performance (4-plex) | LoB: 0-16.29 copies/mLLoD (Allele Frequency): ≤ 0.38%R²: ≥ 0.98 [7] | Demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity achievable with optimized, standardized protocols. | [7] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hybridization Assays

| Reagent | Function / Principle | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (Guanidine HCl/thiocyanate) | Denature proteins, disrupt water structure to promote nucleic acid binding to silica [3]. | Cell lysis and nucleic acid purification prior to hybridization [3]. |

| Biotin-labeled Probes | Serve as affinity reagents; captured by streptavidin-coated beads or detected with streptavidin-enzyme conjugates [2] [5]. | Hybridization capture experiments like CHART, ChIRP; Chromogenic In Situ Hybridization (CISH) [2] [5]. |

| Digoxigenin-labeled Probes | Non-radioactive immune tag; detected with high-affinity anti-digoxigenin antibodies. Avoids background from endogenous biotin [4]. | Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH), CISH [4]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes | Sugar-modified nucleotides that increase duplex stability and thermal affinity, enhancing specificity, though requiring careful optimization [2] [7]. | Increasing probe specificity, especially for short sequences in techniques like ISH and multiplex dPCR [2] [7]. |

| Formamide | Denaturant that lowers the effective melting temperature (Tm) of nucleic acid hybrids, allowing high-stringency hybridization at lower temperatures to preserve morphology [4]. | In Situ Hybridization (ISH) buffers [4]. |

| Mediator Probes (MP) & Universal Reporters (UR) | Label-free MPs bind target; a separate, standardized UR generates fluorescence upon MP cleavage. Enables highly specific, optimization-free multiplexing [7]. | Multiplex digital PCR for detecting cancer-associated point mutations in liquid biopsies [7]. |

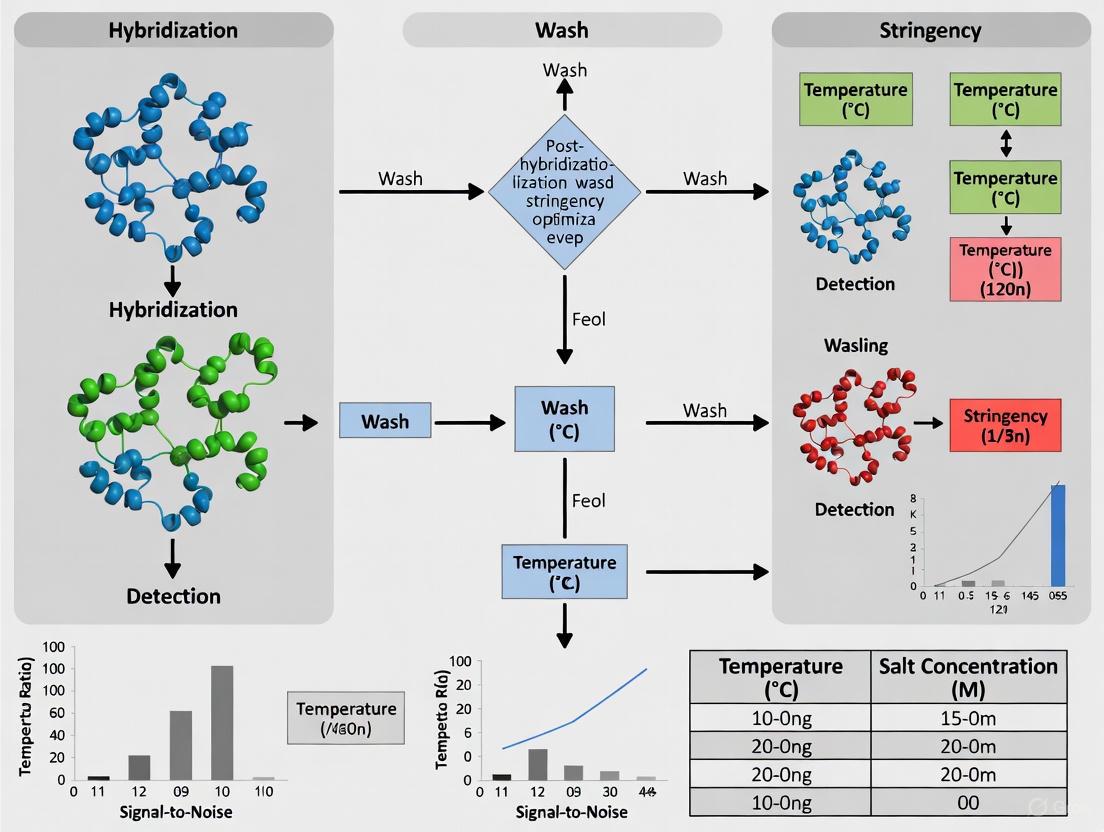

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Core hybridization workflow and stringency control.

Diagram 2: How stringency washes discriminate hybrids.

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My hybridization experiment has low signal-to-noise ratio. Which parameter should I adjust first? Start by optimizing the stringency of your post-hybridization washes. Low signal-to-noise ratio is often caused by non-specific binding or off-target probe retention. Increase the stringency gradually by:

- * Raising the temperature* of your wash buffers within the stability limits of your hybrid.

- Increasing the formamide concentration in your hybridization buffer, as it is a common chemical denaturant used to control stringency [8].

- Lowering the salt concentration in your wash buffers, as reduced cation concentration destabilizes non-specific bonds [9]. Systematically testing a range for each parameter while holding the others constant will help you identify the optimal conditions.

FAQ 2: How can I reduce non-specific background signal in my FISH-based assay? Non-specific background can be introduced by off-target binding of probes. This issue can be tissue- and probe-specific [8].

- Pre-screen readout probes: Test your readout probes against your sample type to identify those that bind non-specifically and exclude them from your panel [8].

- Optimize encoding probe hybridization: The efficiency and specificity of probe assembly depend on the denaturing conditions during hybridization, which are a combination of temperature and chemical denaturants like formamide [8]. Screen a range of formamide concentrations to find the optimal balance for your specific probes.

- Use high-quality reagents: Ensure buffers are fresh and properly prepared, as reagent "aging" during long experiments can decrease performance and increase background [8].

FAQ 3: What is the most critical factor for ensuring reproducible hybridization results? Rigorous calibration and maintenance of your temperature control systems is paramount. Temperature directly influences hybridization kinetics and stringency.

- Calibrate regularly: Use and maintain calibrated equipment to ensure the set temperature matches the actual temperature in your sample tube or bath.

- Ensure consistent heating: Inadequate temperature control during steps like initial denaturation or hybridization will lead to significant variability in hybrid formation and stability.

- Account for temperature in protocols: Remember that the electrode slope in pH measurements is temperature-dependent; inaccurate temperature data will lead to inaccurate pH control, which is another key parameter [10].

The following table summarizes the general effects of changing key parameters on hybrid stability and experimental stringency. Use this as a guide for systematic optimization.

| Parameter | Effect on Hybrid Stability | Effect on Stringency | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Increase | Decreases [8] [11] | Increases | A higher temperature promotes dissociation of mismatched hybrids. Screen a range of ± 5°C from the predicted Tm [11]. |

| Salt Concentration Increase | Increases [9] | Decreases | Higher cation (e.g., Naâº) concentration stabilizes the hybrid by shielding the negative phosphate backbone charges. For binding to a column, a concentration between 50-150 mM NaCl is often used [9]. |

| pH Deviation from Neutral | Variable, can decrease | Variable | Alkaline or acidic conditions can disrupt hydrogen bonding. The specific effect depends on the nucleotide composition and the buffer system used. |

| Chemical Denaturants (e.g., Formamide) | Decreases [8] | Increases | Adding formamide allows for a reduction in the hybridization temperature, which can be useful for protecting tissue samples. The effect on single-molecule signal brightness can be weak across an optimal range [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Formamide Stringency Screening

This protocol is designed to systematically determine the optimal formamide concentration for hybridization, based on methodologies used in multiplexed RNA FISH optimization [8].

1. Objective To identify the formamide concentration that maximizes specific signal (brightness of single-molecule spots) while minimizing background in a single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) experiment.

2. Materials

- Fixed cell or tissue sample.

- Encoding probe set targeting your RNA of interest.

- Fluorescently labeled readout probes.

- Hybridization buffer (without formamide).

- Formamide (molecular biology grade).

- Wash buffers of varying stringency (e.g., with different SSC concentrations).

- Fluorescence microscope.

3. Procedure

- Step 1 - Preparation: Prepare a series of hybridization buffers containing formamide at concentrations varying in 5% increments (e.g., 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%).

- Step 2 - Hybridization: Apply your encoding probe set to identical sample sections, each using one of the formamide buffers. Hybridize at a fixed temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a fixed duration (e.g., 24 hours) [8].

- Step 3 - Washes: Perform post-hybridization washes with appropriate stringency buffers.

- Step 4 - Readout: Hybridize with fluorescent readout probes.

- Step 5 - Imaging and Analysis: Image all samples under identical conditions. Quantify the average brightness of single-molecule fluorescent spots and the background signal intensity for each condition.

4. Data Analysis Plot the average single-molecule signal brightness and the background intensity against the formamide concentration. The optimal condition is the one that provides a high signal intensity with a low background, typically appearing as a plateau in the signal-to-noise ratio.

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for optimizing hybrid stability parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for experiments investigating hybrid stability.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Encoding Probes | Unlabeled DNA probes that bind to the cellular RNA. They contain a targeting region and a barcode region for readout [8]. |

| Fluorescent Readout Probes | Short, fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides that bind to the barcode region of the encoding probes assembled on the RNA, allowing detection [8]. |

| Formamide | A chemical denaturant used in hybridization buffers to control stringency, allowing for lower hybridization temperatures [8]. |

| SSC Buffer (Saline-Sodium Citrate) | A common buffer used in hybridization and washes. Its concentration directly controls ionic strength (salt concentration), which is a key parameter for stringency. |

| pH Buffer Solutions | To maintain a stable and specific pH during hybridization and washing steps, which is critical for reproducible hybrid stability. |

| Blocking Oligos | Unlabeled oligonucleotides used to mask repetitive sequences in the genome, reducing non-specific binding of probes [12]. |

| PMMB-317 | PMMB-317|Irreversible Dual Tubulin/EGFR Inhibitor |

| Chroman-3-amine | Chroman-3-amine|Pharmaceutical Research Building Block |

Troubleshooting Guides

Low or No Hybridization Signal

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or no signal | Low probe density or improper surface immobilization [13] | Optimize probe immobilization conditions (ionic strength, interfacial electrostatic potential) [13]. |

| Excessive steric hindrance from high probe density [13] | Dilute the probe layer to reduce density and improve target access [13] [14]. | |

| Inefficient denaturation of target or probe | Ensure denaturation is performed at 95±5°C for 5-10 minutes with the sample cover-slipped to prevent evaporation [5]. | |

| Inadequate permeabilization of sample | Optimize permeabilization conditions (concentration, time, temperature) using agents like Triton X-100 or proteinase K [15]. |

High Background or Non-Specific Signal

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background staining | Inadequate post-hybridization stringency washing [5] | Perform stringent washes with SSC buffer at 75-80°C for 5 minutes [5]. |

| Non-specific binding from probe repetitive sequences | Add COT-1 DNA during hybridization to block repetitive sequences [5]. | |

| Sample drying during protocol steps | Ensure slides and samples remain humidified throughout the entire procedure [5]. | |

| Electrostatic cross-talk between charged DNA molecules [14] | For DNA probes, optimize ionic strength during hybridization; use ~100 mM Na+ concentration [14]. |

Issues with Hybridization Efficiency and Kinetics

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low hybridization efficiency | Excessively high surface probe density [13] | Control probe density during immobilization. High densities can reduce efficiency to ~10% [13]. |

| Slow hybridization kinetics | Steric and electrostatic barriers on solid support [13] [14] | Use strategic templated immobilization to dilute PNA/DNA probe layer and reduce electrostatic repulsion [14]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does surface probe density directly impact hybridization?

Probe density is a critical controlling factor. At low densities, hybridization can be highly efficient with kinetics that follow Langmuir-like models. In contrast, at high densities, hybridization efficiency can drop dramatically to around 10%, and the kinetics of target capture become significantly slower due to steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion [13].

What are the key differences between solution-phase and surface hybridization?

Surface-immobilized probes operate under different constraints than solution-phase reactions. Thermodynamic equilibrium may not be reached in a practical time, and hybridization can be kinetically or sterically inaccessible for some sequences or surface densities, which is not a concern in solution [13].

How can I optimize my protocol for better RNA FISH performance (like MERFISH)?

Performance depends on multiple protocol choices. Key optimizations include:

- Probe Design: Signal brightness depends on target region length, with 20-50 nt being typical. Efficiency plateaus for sufficiently long regions, so optimize for cost and specificity [8].

- Hybridization Buffer: Modifications to encoding probe hybridization and buffer composition can substantially enhance the probe assembly rate and signal brightness [8].

- Reagent Stability: Reagents can "age" during multi-day experiments. Use methods to ameliorate this effect for consistent performance [8].

Can I use the same stringency wash conditions for all my experiments?

No, stringent wash conditions must be optimized for your specific probe and sample. While 75-80°C in SSC buffer is a common starting point [5], the ideal temperature and salt concentration depend on the probe's melting temperature (Tm) and the level of non-specific binding. Always validate for each new assay.

Impact of Probe Density on Hybridization Efficiency and Kinetics

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research on DNA films [13].

| Probe Density Regime | Hybridization Efficiency | Kinetics Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Low Density | Up to ~100% of probes can be hybridized | Follows Langmuir-like kinetics |

| High Density | Drops to ~10% | Significantly slower than low-density regime |

Effect of Ionic Strength on Hybridization

This table summarizes the influence of salt concentration, a key parameter in your wash stringency, on the hybridization process [14].

| Parameter | Effect of Low Ionic Strength | Effect of High Ionic Strength | Optimal Range (for PNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate | Subject to electrostatic barrier (DNA probes) [14] | Monotonic decrease [14] | --- |

| Hybridization Signal | Suboptimal due to repulsion [14] | Suboptimal due to other factors [14] | ~100 mM Na+ [14] |

Experimental Protocols

Controlled Immobilization of DNA Probes for Density Studies

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating DNA films with controlled probe density, as used in foundational studies [13].

Key Materials:

- Oligonucleotides: Thiol-modified DNA oligonucleotides (e.g., C6-SH) for covalent attachment to gold surfaces.

- Solid Support: Cleaned gold substrate (e.g., for SPR spectroscopy).

- Solution: KHâ‚‚POâ‚„ (1 M) or other salts to control ionic strength during immobilization.

- Backfiller: Mercaptohexanol (1 mM solution) to create a well-defined mixed monolayer.

Detailed Procedure:

- Surface Cleaning: Clean the gold substrate with a piranha solution (7:3 Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„:Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). CAUTION: Piranha solution is extremely corrosive and must be handled with care.

- Probe Immobilization: Immobilize thiol-modified ssDNA or dsDNA onto the gold surface by exposure for a controlled duration (e.g., >10 hours).

- Density Control: Vary the probe density by using different immobilization strategies:

- Solution Ionic Strength: Immobilize in buffers of different salt concentrations.

- Electrostatic Potential: Apply an interfacial electrostatic field to assist in DNA adsorption.

- DNA Conformation: Compare immobilization of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) versus duplex DNA (dsDNA). Under the same conditions (1 M KH₂PO₄), ssDNA-C6-SH achieves a higher density (~11 × 10¹² molecules/cm²) than dsDNA-C6-SH (~2.8 × 10¹² molecules/cm²) [13].

- Backfilling: Treat the DNA film with a 1 mM mercaptohexanol solution for 1-2 hours to passivate unoccupied gold sites.

- Denaturation (for dsDNA films): If duplex DNA was immobilized, denature the film by rinsing with hot water (e.g., 80°C) to remove the non-tethered strand, creating an ssDNA probe surface.

Optimized Hybridization and Stringency Wash Protocol for CISH/FISH

This protocol provides detailed steps for reliable hybridization and washing, critical for your thesis context [5].

Key Materials:

- Pretreatment Buffer: For heat-induced epitope retrieval.

- Digestion Solution: Pepsin, optimized for your tissue type (typically 3-10 minutes at 37°C).

- Hybridization Buffer: Contains formamide, SSC, etc.

- Wash Buffers: PBST (PBS with 0.025% Tween 20), SSC buffer (for stringent wash).

Detailed Procedure:

- Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval: Heat slides in pretreatment buffer for 15 minutes once the buffer reaches 98°C.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Treat slides with pepsin at 37°C for 3-10 minutes. Over-digestion weakens signal; under-digestion decreases signal.

- Denaturation: Denature target and probe simultaneously on a hot plate at 95±5°C for 5-10 minutes. Ensure slides are cover-slipped and in a humidified environment.

- Hybridization: Apply probe and hybridize at 37°C for 16 hours (overnight) in a sealed, humidified chamber.

- Post-Hybridization Washes:

- Remove coverslips by soaking in PBST.

- Wash slides in PBST, then incubate with pre-warmed TBS wash buffer at 37±2°C for 15 minutes.

- Stringent Wash (Critical for Specificity):

- Rinse slides briefly with SSC buffer at room temperature.

- Immerse slides for 5 minutes in SSC buffer at 75°C. Increase the temperature by 1°C per slide when processing more than 2 slides, but do not exceed 80°C.

- After the stringent wash, rinse slides with TBST.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Mercaptohexanol | Used as a backfilling agent with thiol-modified DNA on gold surfaces. Creates a well-defined mixed monolayer that reduces non-specific adsorption and can help control probe spacing and orientation [13]. |

| COT-1 DNA | Used to block non-specific hybridization of probes to repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu, LINE elements) in the genome, thereby reducing background staining [5]. |

| Formamide | A chemical denaturant used in hybridization buffers to lower the effective melting temperature (Tm) of nucleic acid duplexes, allowing hybridization to be performed at milder, more controlled temperatures [8]. |

| PNA (Peptide Nucleic Acid) Probes | Synthetic probes with a neutral peptide backbone. They lack the negative charge of DNA, which can reduce electrostatic repulsion with target DNA and improve hybridization kinetics and affinity, especially under low ionic strength conditions [14]. |

The optimization of post-hybridization wash stringency is fundamentally governed by the relationship between two key thermodynamic principles: the melting temperature (Tm) and Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG). The Tm of a nucleic acid duplex is the temperature at which half of the molecules are in a single-stranded state and half are in a double-stranded state [16]. Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) represents the amount of "useful" energy available to do work at constant temperature and pressure, and its negative value (ΔG < 0) indicates a spontaneous process [17]. In the context of hybridization experiments, a thorough understanding of how these two parameters interrelate and respond to experimental conditions is crucial for achieving specific binding while minimizing non-specific background.

Fundamental Principles & Mathematical Relationships

The Definition of Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG)

In thermodynamic terms, the Gibbs Free Energy is defined as ( G = H - TS ), where H is enthalpy, T is temperature, and S is entropy [17]. The change in Gibbs Free Energy for a process, such as DNA hybridization, is given by: [ \Delta G = \Delta H - T \Delta S ] A negative ΔG signifies a spontaneous process, while a positive value indicates non-spontaneity [17]. For nucleic acid hybridization, a negative ΔG reflects a favorable reaction where the duplex is stable.

The Relationship Between ΔG and Tm

The Tm is directly related to the thermodynamic parameters of the system. At the melting temperature, the system is at equilibrium between the double-stranded and single-stranded states, meaning ( \Delta G = 0 ). This allows for the derivation of the relationship: [ T_m = \frac{\Delta H}{\Delta S - R \ln(C)} ] where R is the gas constant and C is the concentration [18]. This equation demonstrates that Tm is not an intrinsic constant but depends on the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) changes of hybridization, as well as experimental conditions like oligo concentration.

Key Factors Influencing Tm and ΔG

The following factors critically influence both Tm and the free energy of hybridization, directly impacting wash stringency optimization [16]:

- Salt Concentration: Monovalent cations (e.g., Naâº) stabilize duplexes. Increasing salt concentration increases Tm.

- Divalent Cations: Magnesium ions (Mg²âº) have a more profound effect on stability than monovalent ions. The concentration of free Mg²⺠must be carefully considered.

- Oligonucleotide Concentration: Tm increases with higher oligo concentrations.

- Mismatches: Base pair mismatches decrease duplex stability and Tm, with the effect depending on the mismatch type and sequence context.

- Probe Length and GC Content: Longer probes and higher GC content generally increase Tm.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: During post-hybridization washes, I consistently get high background. How can thermodynamic principles help me solve this?

- Explanation: High background indicates non-specific binding of your probe. This occurs when the wash stringency is too low to destabilize imperfectly matched duplexes.

- Solution Based on Tm/ΔG: Increase the stringency of your washes. Since ΔG becomes less favorable (less negative) at higher temperatures, you can increase the wash temperature. Alternatively, you can decrease the salt concentration in your wash buffer (e.g., use a lower concentration of SSC). Both actions reduce the Tm of non-specific hybrids, causing them to denature and wash away, while the perfectly matched target-probe duplex (with a higher Tm) remains bound [19] [16] [20].

FAQ 2: My signal is too weak after washing, even with a validated probe. What should I troubleshoot?

- Explanation: Weak signal suggests that the specific target-probe duplex is also being destabilized during washes, meaning the stringency is too high.

- Solution Based on Tm/ΔG: Decrease the wash stringency. Lower the wash temperature and/or increase the salt concentration in your wash buffer. This will stabilize the duplexes by making ΔG more favorable, preventing the specific hybrids from melting off [19] [4]. Also, verify your probe concentration, as lower than optimal concentrations can lead to a weaker signal due to a lower observed Tm [16].

FAQ 3: How does a single base pair mismatch (like a SNP) affect my experiment, and how can I adjust for it?

- Explanation: A single mismatch destabilizes the duplex, making ΔG less negative and lowering its Tm compared to a perfectly matched duplex.

- Solution Based on Tm/ΔG: You can exploit this difference for discrimination. To preferentially detect the perfectly matched sequence, increase stringency (higher temperature, lower salt) until the Tm of the mismatched duplex is exceeded and it denatures. For PCR assays, placing the mismatch near the 5' end of a probe or primer minimizes its destabilizing effect on the 3' end, which is critical for extension [16]. Using shorter probes can also enhance mismatch discrimination [16].

Troubleshooting Guide Table

The table below summarizes common issues and their thermodynamic solutions.

| Problem | Root Cause | Thermodynamic Solution | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background | Wash stringency too low; non-specific hybrids remain. | Increase wash temperature [19] [20] or decrease salt concentration (e.g., use 0.1x SSC instead of 2x SSC) [19] [20]. | Non-specific hybrids melt, reducing background. |

| Weak Specific Signal | Wash stringency too high; specific hybrids are melting. | Decrease wash temperature [4] or increase salt concentration [19]. | Specific hybrids remain stable, preserving signal. |

| Poor Mismatch Discrimination | Stringency not optimized to differentiate between perfect and mismatched duplexes. | Fine-tune wash temperature and salt to a point between the Tm of the perfect and mismatched duplex. | Only the perfect-match hybrid remains bound. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Runs | Variation in buffer ion concentration or temperature. | Precisely control temperature (±1°C) [19] and accurately prepare SSC buffer concentrates. | Highly reproducible hybridization and wash results. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Determining Tm via UV Melting Curve

Principle: The hyperchromic effect describes the increase in UV absorbance at 260 nm as double-stranded DNA melts into single strands [18].

Materials:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a temperature-controlled cuvette holder.

- DNA oligonucleotide and its perfect complement.

- Appropriate hybridization buffer (e.g., containing defined Na⺠or Mg²⺠concentrations).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mix equimolar amounts of complementary oligonucleotides in buffer. Denature at 95°C for 2 minutes and cool slowly to room temperature to allow duplex formation [18].

- Data Collection: Place the sample in the spectrophotometer. Increase the temperature gradually (e.g., 1-2°C per minute) while monitoring absorbance at 260 nm.

- Analysis: Plot absorbance versus temperature. The Tm is determined as the midpoint of the transition curve between the double-stranded and single-stranded plateaus (see diagram below) [18].

Workflow Diagram: From Experiment to Tm Calculation

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table 1: Effect of Salt Concentration on Tm and Implied ΔG Adjusting salt concentration is a primary method for stringency control. The data below illustrates its powerful effect [16].

| Sodium Ion (Naâº) Concentration | Approximate Effect on Tm | Thermodynamic Impact on ΔG |

|---|---|---|

| 20-30 mM | Baseline Tm | Baseline ΔG |

| 50 mM (Common in SSC buffers) | +0 to +2 °C | ΔG becomes more negative (more favorable) |

| 1 M | ~ +20 °C | ΔG becomes significantly more negative |

Table 2: Standard Post-Hybridization Wash Conditions These common conditions from FISH protocols can serve as a starting point for optimization [19].

| Wash Step | Buffer Composition | Temperature | Duration | Stringency Level & Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Wash | 0.4x SSC | 72 ± 1 °C | 2 min | High Stringency: Removes non-specific binding. |

| Secondary Wash | 2x SSC / 0.05% Tween | Room Temperature | 30 sec | Low Stringency: Removes residual buffer and stabilizes sample. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hybridization & Wash Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Role in Controlling Tm / ΔG |

|---|---|---|

| SSC Buffer (Saline-Sodium Citrate) | Provides monovalent cations (Naâº) during hybridization and washes [19] [20]. | Na⺠neutralizes the negative charge on DNA backbones. Higher [SSC] stabilizes duplexes (increases Tm, makes ΔG more negative) [19] [16]. |

| Formamide | Added to hybridization buffer to lower the effective melting temperature of probes [20] [4]. | Destabilizes hydrogen bonding between base pairs. Allows hybridization to occur at lower, morphologically safer temperatures (lowers Tm, makes ΔG less favorable) [4]. |

| TWEEN 20 (Detergent) | Non-ionic detergent added to wash buffers [19]. | Reduces background staining by minimizing hydrophobic interactions and enhances reagent spreading. Does not directly affect Tm/ΔG of nucleic acid duplexes. |

| DNA Oligonucleotide Probes | The molecular tool designed to bind a specific nucleic acid target. | Their sequence (length, GC content) defines the intrinsic ΔH and ΔS of hybridization, setting the baseline Tm [18] [16]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) | Synthetic nucleic acid analogues incorporated into probes [16]. | Enhance binding affinity to the target. Increase Tm and make ΔG more negative, allowing the use of shorter, more specific probes [16]. |

| PAESe | PAESe|Phenylaminoethyl Selenide|Research Compound | PAESe is a selenium-based antioxidant for research on doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N-Iodoacetyltyramine | N-Iodoacetyltyramine|Sulfhydryl-Reactive Labeling Reagent | N-Iodoacetyltyramine is a bioconjugation reagent for site-specific labeling of cysteine thiols and ¹²⁵I radiolabeling. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Concepts: Solvation Energy

Emerging research highlights that classical models may not fully account for the role of water. The formation of a DNA duplex releases water molecules that were solvating the single strands. This process has a associated solvation free energy (ΔGS), which recent studies suggest can be large and unfavorable (positive) for DNA hybridization [21]. This means energy must be expended to desolvate the interacting surfaces. This advanced framework modifies the classical equilibrium equation to: [ \Delta G^\circ = -RT \ln(K) - [AB]{eq} \Delta GS ] where [AB] is the concentration of the duplex. This implies the equilibrium constant K is not truly constant but can vary with product concentration when ΔGS is significant [21]. While this may not change immediate protocol decisions, it provides a deeper theoretical foundation for understanding hybridization behavior under different conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why are spacer molecules necessary in microarray design? Spacer molecules are crucial because they position the probe sequence away from the solid substrate. This distance reduces steric hindrance and minimizes unfavorable electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged DNA backbone and the often negatively charged surface, which can dramatically reduce hybridization efficiency and signal intensity [22] [23].

What is the optimal length for a spacer? Research indicates that an optimal spacer length is about 45–60 atoms, which corresponds to approximately 8–10 nucleotides [22]. One study found that hybridization signal increased linearly with poly(A) spacer length up to 18-24 nucleotides for certain targets [22].

How does probe distance from the surface affect wash stringency? The stringency required for accurate results is directly influenced by the probe's distance from the surface. Probes closer to the surface are influenced by additional surface-related stringency. Research has shown that probes near the surface required a 4x SSC wash buffer, while those placed further away required a much lower ionic strength buffer (0.35x SSC) to achieve accurate genotyping, indicating different local environments [22].

Can I use any nucleotide sequence as a spacer? No, the spacer sequence should be carefully selected to avoid complementarity with the target sequence. In silico screening using tools like BLASTN for short, nearly exact matches is recommended to identify sequences that will not hybridize to the target and potentially create a hairpin structure [22].

What are the consequences of insufficient spacer length? Short spacer lengths can lead to significantly reduced hybridization signals. This is due to steric hindrance preventing target access and strong electrostatic effects from the surface that can reduce the local melting temperature (Tm) of the probe-target duplex by tens of degrees Celsius [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or No Hybridization Signal

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient spacer length | Review probe design specifications. Compare signal intensity against probes with validated longer spacers. | Redesign probes to include a spacer of 45-60 atoms (approx. 8-10 nucleotides) between the surface and the recognition sequence [22] [23]. |

| High probe density | Analyze surface probe density if possible. High densities can lead to steric and electrostatic crowding. | Optimize the probe immobilization protocol to achieve a moderate surface density that maximizes the signal-to-background ratio [23]. |

| Spacer sequence hybridization | Perform in silico analysis (BLAST) of the spacer sequence against the target genome. | Select a neutral spacer sequence with no significant complementarity to the intended target to prevent non-specific binding [22]. |

Problem: High Background Signal

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific adsorption | Check for non-specific binding on control spots. Ensure buffers contain detergents. | Include TWEEN 20 detergent in wash buffers to decrease background staining and enhance reagent spreading [19]. |

| Sub-optimal stringency washes | Evaluate if background is uniform or spot-specific. Experiment with different wash stringencies. | Optimize post-hybridization wash stringency by adjusting SSC concentration and temperature. Probes farther from the surface may require lower SSC concentration (e.g., 0.35x) [22]. |

| Surface contaminants | Inspect slides for debris. Review cleaning protocols for solution jars and equipment. | Periodically wash solution jars and use filtered pipette tips to reduce background issues from expelled debris [19]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Specificity Across Probes

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable spacer placement | Check if all probes are designed with a consistent spacer strategy. | Standardize spacer length and attachment chemistry for all probes on the array to ensure uniform hybridization behavior [22]. |

| Ignoring surface-induced stringency | Analyze if specificity issues correlate with probe design. | Account for the additional stringency imposed by the surface, especially for probes tethered shorter. Adjust global wash conditions or redesign affected probes with longer spacers [22]. |

Table 1: Impact of Spacer Length on Hybridization Performance Data derived from systematic studies on spacer molecules [22].

| Spacer Length (Atoms) | Approximate Length (Nucleotides) | Relative Signal Intensity | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~15-20 | ~3-4 | Low | Significant steric and electrostatic hindrance; very low signal. |

| ~45 | ~8 | Medium-High | Good signal; often considered a minimum effective length. |

| ~60 | ~10 | High | Optimal range for maximum hybridization yield and signal. |

| >60 | >10 | Saturated | No significant further improvement in signal intensity. |

Table 2: Relationship Between Probe Distance and Wash Stringency Experimental data showing how spacer length alters effective stringency requirements [22].

| Probe Distance from Surface | Optimal Wash Buffer (SSC) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Close (Short Spacer) | 4x SSC (Higher Salt) | Higher ionic strength is needed to shield strong negative surface potentials that destabilize duplexes. |

| Far (Long Spacer) | 0.35x SSC (Lower Salt) | Surface effects are minimized; standard lower ionic strength washes effectively remove non-specific binding. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Multi-Parametric Optimization of Spacer Length and Stringency

This protocol is based on a study that systematically varied spacer length, probe length, and wash stringency to optimize microarray performance [22].

1. Probe Design and Array Fabrication:

- Design Probes: Design 60-mer oligonucleotide probes targeting your genes of interest. Incorporate a spacer (linker) at the 5' end to position the probe sequence at a defined distance from the surface.

- Vary Spacer Length: Create probe sets with three distinct spacer lengths, effectively placing the gene-specific sequence in discrete steps along the oligonucleotide (e.g., proximal, medium, and distal from the surface upon immobilization).

- Fabricate Arrays: Synthesize and spot the probes onto your chosen microarray substrate (e.g., commercially available 8x15k custom arrays).

2. Hybridization and Multi-Stringency Wash:

- Hybridize: Hybridize the labeled target sample to the array according to standard protocols for your system.

- Multi-Stringency Wash: Use a custom-built multi-stringency array washer (MSAW) or manually partition the array to apply six different stringency wash conditions to identical sub-arrays. Vary the ionic strength of the SSC buffer (e.g., from 0.1x to 4x SSC) while keeping other factors like temperature and time constant.

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Scan Array: Scan the microarray using a standard laser scanner to obtain fluorescence signal intensities for each spot.

- Analyze Signal and Specificity: For each probe and wash condition, quantify the specific hybridization signal and non-specific background.

- Plot Dissociation Curves: If possible, generate dissociation curves by monitoring signal loss across the different stringency washes.

- Correlate with Thermodynamics: Perform linear regression between the experimental hybridization data and calculated thermodynamic parameters (Tm and ΔG) to understand how spacer length and wash condition affect correlation with theory.

Experimental Workflow for Spacer Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Probe Spacer Optimization Compilation of critical materials from referenced protocols [22] [19] [23].

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Spacer Phosphoramidites (e.g., Hexa-ethyloxy-glycol) | Chemical building blocks used during oligonucleotide synthesis to create a defined, non-nucleotide spacer between the probe and the surface [24]. | Length (number of atoms) and hydrophobicity are key parameters. Inertness is critical to avoid non-specific binding. |

| SSC Buffer (Saline Sodium Citrate) | The primary buffer used for controlling stringency in post-hybridization washes. Ionic strength (SSC concentration) is a major determinant of stringency [22] [19]. | Concentration (e.g., 0.1x to 4x) and pH must be precisely prepared and controlled for reproducible results. |

| TWEEN 20 | A non-ionic detergent added to wash buffers to reduce non-specific hydrophobic interactions and lower background staining [19]. | Typical concentration is 0.05%. Enhances the spreading of wash reagents. |

| 5' Amino-Linker Modifier | A chemical modification (e.g., 5'-Amino-Modifier C6) added to the oligonucleotide to allow for covalent tethering to surface-activated slides [24]. | Ensures probes are stably and uniformly immobilized, which is the foundation for consistent spacer function. |

| Formamide | A denaturing agent used in hybridization buffers to lower the effective melting temperature (Tm) of the probe-target duplex, allowing hybridization to be performed at a manageable temperature [20]. | Allows for lower temperature hybridization, which can help preserve sample integrity. |

| Azo fuchsine | Azo fuchsine, CAS:3567-66-6, MF:C16H11N3Na2O7S2, MW:467.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Eboracin | Eboracin, CAS:57310-23-3, MF:C14H13NO5, MW:275.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Impact of Spacer Molecules on Hybridization

Practical Implementation: Stringency Optimization Protocols for Diverse Applications

SSC Buffer FAQs and Troubleshooting

What is SSC buffer and what is its role in post-hybridization washes?

Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer is a standard solution used in nucleic acid hybridization techniques such as Southern blotting, Northern blotting, and in situ hybridization (ISH) [25]. Its primary role in post-hybridization washes is to control stringency, which determines the specificity of the hybridization [26] [25]. The buffer provides positively charged sodium ions that counteract the repulsive negative forces between the DNA backbones of the probe and its target [26]. This action is crucial for removing non-specific interactions and ensuring that only perfectly matched probe-target hybrids remain [26].

How do SSC concentration and temperature affect wash stringency?

The stringency of a post-hybridization wash is determined by the combined effect of SSC concentration and temperature. Adjusting these parameters allows researchers to fine-tune the required level of specificity for their experiment.

Key Relationships:

- SSC Concentration: Lower SSC concentrations provide higher stringency by reducing the ionic strength, which disrupts non-specific bonds [26].

- Temperature: Higher wash temperatures provide higher stringency by destabilizing imperfectly matched hybrids [26].

The table below summarizes standard post-hybridization wash conditions from a hematology FISH protocol:

| Probe Type | First Wash | Second Wash | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Probes [26] | 0.4x SSC at 72°C ± 1°C for 2 mins | 2x SSC / 0.05% Tween at room temperature for 30 sec | Balance specificity with signal retention |

| Enumeration Probes [26] | 0.25x SSC at 72°C ± 1°C for 2 mins | 2x SSC / 0.05% Tween at room temperature for 30 sec | Achieve higher stringency for repetitive targets |

What are the consequences of incorrect stringency?

Using incorrect wash stringency is a common source of experimental problems in hybridization assays.

- High Background/Non-specific Signals: Caused by low stringency washes (e.g., temperature below 71°C or SSC concentration higher than 0.4x) [27] [26]. This results in failure to wash away weakly bound or non-specifically bound probes.

- Weak or Lost Signal: Caused by excessively high stringency washes (e.g., temperature above 73°C or SSC concentration lower than 0.4x) [27] [26]. Overly stringent conditions can denature even the specific probe-target hybrids.

How is SSC buffer typically formulated?

SSC buffer is commonly prepared as a 20X concentrated stock solution for convenient dilution to working concentrations. The standard formulation is consistent across major suppliers.

Table: Standard 20X SSC Buffer Formulation

| Component | Concentration | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | 3.0 M [25] [28] | Provides sodium ions (Na+) to shield negative phosphate backbone charges |

| Sodium Citrate (C6H5Na3O7) | 0.3 M [25] [28] | Acts as a buffering agent, maintaining pH at 7.0 [25] [28] |

What other factors influence wash effectiveness?

- Detergents: Adding a small amount of detergent, such as 0.05% Tween 20, to the wash buffer helps reduce background staining and improves reagent spreading [26].

- pH: The pH of the SSC buffer affects the availability of positive ions. Deviations from the standard pH of 7.0 can alter stringency and lead to unexpected results [26].

- Equipment Calibration: Regular calibration of water baths and hybridizers is critical. Temperature discrepancies in equipment can lead to unintentional variations in stringency [26].

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Post-Hybridization Washes

The following workflow details a standard method for post-hybridization stringency washes, adaptable for both chromogenic and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) protocols [27] [26] [29].

Workflow for Post-Hybridization Washes

Key Materials & Reagents:

- SSC Buffer (20X Stock): 3.0 M NaCl, 0.3 M Sodium Citrate, pH 7.0 [25] [28].

- Detergent: Tween-20 [27] [26].

- Lab Equipment: Coplin jars or staining dishes, water bath or hybridization oven calibrated to maintain 72°C ± 1°C [27] [26].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Coverslip Removal: Gently remove the coverslips from the slides after the overnight hybridization [27].

- First Stringency Wash: Perform the first wash in a pre-warmed, low-SSC concentration buffer. The exact formulation depends on the probe type, as shown in the diagram above. Use a water bath or hybridization oven to ensure precise temperature control, as stringency is highly temperature-sensitive [27] [26].

- Second Stringency Wash: Perform a brief wash at room temperature with a higher SSC concentration and a detergent like Tween 20. This step helps to remove residual reagents and further reduce background without risking the specific signal [26].

- Proceed to Detection: After the final wash, slides can be moved to the next stage of the protocol, such as antibody incubation for signal detection [27] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Hybridization and Wash Protocols

| Reagent | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SSC Buffer (20X) [25] [28] | Controls stringency during hybridization and washes; ions stabilize nucleic acid hybrids. | Used in post-hybridization washes for FISH and ISH [26] [29]. |

| Formamide [27] [29] | A denaturing agent used in hybridization buffers to lower the melting temperature (Tm) of DNA. | Allows hybridization to occur at lower, less damaging temperatures (e.g., 37-45°C) [27]. |

| Blocking Reagents (e.g., BSA, Casein, Heparin) [27] [29] | Bind to non-specific sites on the tissue or membrane to prevent probe attachment and reduce background. | Included in pre-hybridization and hybridization buffers [27]. |

| Detergents (Tween-20, SDS) [27] [26] | Surfactants that help permeabilize samples, aid in washing efficiency, and reduce background staining. | Added to wash buffers (e.g., 2x SSC/0.05% Tween) [26]. |

| Proteinase K [27] | An enzyme that digests proteins and increases tissue permeability, allowing better probe penetration. | Used for sample pre-treatment before hybridization [27]. |

| 4-Iodobutanal | 4-Iodobutanal (77406-93-0)|RUO|Supplier |

Core Concepts: The Role of Post-Hybridization Washes

What is the primary function of a post-hybridization wash?

Post-hybridization washing is a critical step designed to remove non-specific interactions between the probe and non-target regions of the genome. This process enhances probe specificity by eliminating improperly bound probes, thereby reducing background noise and improving the signal-to-noise ratio in your final results [19].

How do stringency factors influence wash efficiency?

Stringency conditions determine how rigorously non-specifically bound probes are removed. The table below summarizes the key factors affecting stringency and their optimal settings for FISH protocols:

Table 1: Key Stringency Factors and Their Effects in Post-Hybridization Washes

| Factor | Effect on Stringency | Low Stringency Example | High Stringency Example | Optimal Condition for FISH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSC Concentration | Higher salt = lower stringency; Lower salt = higher stringency | >0.4xSSC [19] | <0.4xSSC [19] | 0.4xSSC or 0.25xSSC [19] |

| Temperature | Higher temperature = higher stringency | <71°C [19] | >73°C [19] | 72±1°C [19] |

| pH | Deviation from optimal reduces effectiveness | pH differs from 7.0 [19] | pH differs from 7.0 [19] | pH 7.0 [19] |

| Detergent | Reduces background staining | N/A | N/A | 0.05% TWEEN 20 [19] |

The buffers used in post-hybridization washing are typically SSC-based, providing positively charged sodium ions that counteract the repulsive negative force between the DNA backbones of both the probe and target. Appropriate balance of these factors is essential for optimal results [19].

How does the choice of probe type affect wash conditions?

Different probe types form hybrids with varying stability, which directly influences how they respond to wash stringency:

Table 2: Probe Types and Their Hybridization Properties

| Probe Type | Hybrid Stability | Key Considerations | Recommended Wash Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Probes (Riboprobes) | RNA-RNA hybrids are most stable [4] | Uniform size, high incorporation of label [4] | Standard stringency washes [4] |

| DNA Probes | RNA-DNA hybrids are moderately stable [4] | Do not bind as tightly to targets; avoid formaldehyde in washes [4] [30] | Modified wash conditions without formaldehyde [4] |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | DNA-DNA hybrids are least stable [4] | Chemically synthesized to high specific activity [4] | Temperature and salt concentration optimization [4] |

| LNA Probes | Enhanced stability [4] | Locked Nucleic Acid technology enhances efficiency [4] | May tolerate higher stringency conditions [4] |

Technology-Specific Troubleshooting Guides

FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) Troubleshooting

What are common FISH issues and their solutions?

Table 3: FISH Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or No Signal | Inadequate denaturation, insufficient probe concentration, poor permeabilization [15] | Check probe design and labeling efficiency; optimize denaturation and hybridization conditions; increase probe concentration or hybridization time; ensure adequate permeabilization [15] |

| High Background | Insufficient washing, low stringency, cross-reactivity [15] | Optimize wash conditions (temperature, salt concentration, duration); increase stringency of washes; check for probe cross-reactivity [4] [15] |

| Weak or Faded Signal | Fluorophore degradation, over-fixed samples, inadequate detection [15] | Use fresh fluorophore or signal amplification; optimize mounting medium with antifade reagents; minimize light exposure; avoid over-fixation [15] |

| Uneven or Patchy Signal | Uneven probe distribution, air bubbles, uneven drying [15] | Ensure uniform probe distribution during hybridization; avoid air bubbles during mounting; verify sample preparation consistency [15] |

| Morphological Distortion | Over-fixation, over-permeabilization, harsh handling [15] | Optimize fixation and permeabilization conditions; use gentler cell/tissue dissociation methods; ensure proper sample handling and storage [15] |

What are the optimized post-hybridization wash conditions for hematology FISH?

For most FISH applications in hematology, the following wash conditions have been optimized:

- Standard Probes: 0.4xSSC for 2 minutes at 72±1°C, followed by 2xSSC/0.05% Tween for 30 seconds at room temperature [19]

- Enumeration Probes: 0.25xSSC for 2 minutes at 72±1°C, followed by 2xSSC/0.05% Tween for 30 seconds at room temperature [19]

The inclusion of TWEEN 20 detergent is particularly important as it decreases background staining and enhances the spreading of reagents in wash buffers [19].

Microarray Hybridization Troubleshooting

What are frequent microarray hybridization problems and solutions?

Microarray hybridization problems can arise from multiple sources, including printing artifacts, RNA sample quality issues, fluorophore labeling inefficiencies, and suboptimal hybridization conditions [31]. Appropriate controls and detailed image analysis are essential for diagnosing these issues [31].

Key trouble areas include:

- Printing artifacts: Ensure proper printer maintenance and quality control

- RNA sample quality: Verify RNA integrity before proceeding with labeling

- Fluorophore labeling: Optimize labeling efficiency and incorporate appropriate controls

- Hybridization conditions: Standardize temperature, time, and buffer composition

- Post-hybridization washes: Implement stringent wash protocols to reduce background

Tissue Microarray (TMA) In Situ Hybridization Optimization

What are essential tips for successful ISH on Tissue Microarrays?

Proteinase K Digestion: This is a critical step where insufficient digestion diminishes hybridization signal, while over-digestion destroys tissue morphology. Optimal concentration typically ranges from 1-5 µg/mL for 10 minutes at room temperature, but should be titrated for each TMA [4] [30].

Coverslip Selection: Use plastic coverslips or Parafilm instead of glass, as glass can create a vacuum that pulls the small tissue cores off the slide [30].

Hybridization Temperature: Typical hybridization temperatures range between 55°C and 62°C and should be optimized for each tissue microarray analyzed [30].

Reagent Maintenance: Triethanolamine and acetic anhydride should be replenished every 2-3 weeks, and 10% neutral buffered formalin should be changed every 3-4 days [30].

RNase-free Conditions: All reagents and supplies that contact TMA slides must be RNase-free, with glassware for post-hybridization washes reserved exclusively for that purpose [30].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized FISH Post-Hybridization Wash Protocol

Diagram 1: FISH Post-Hybridization Wash Workflow

Comprehensive In Situ Hybridization Workflow

Diagram 2: Comprehensive ISH Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Hybridization Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wash Buffers | SSC-based buffers (0.25xSSC, 0.4xSSC, 2xSSC) [19] | Provide sodium ions to counteract repulsive forces between DNA backbones; concentration determines stringency [19] |

| Detergents | TWEEN 20 (0.05%) [19], Triton X-100 [15] | Reduce background staining and enhance reagent spreading in wash buffers [19] |

| Permeabilization Agents | Proteinase K (1-5 µg/mL) [4], Triton X-100, Tween-20 [15] | Allow probe access to target nucleic acids; requires optimization to balance accessibility and morphology preservation [4] [15] |

| Probe Labels | Fluorescent dyes (Fluorescein, Rhodamine, Cy3, Cy5) [15], Biotin, Digoxigenin [4] | Direct (fluorescent) or indirect (biotin/digoxigenin) detection; digoxigenin preferred for avoiding endogenous biotin [4] |

| Counterstains | DAPI, Propidium Iodide [15] | DNA-binding fluorescent dyes to visualize nuclear and cellular morphology after hybridization [15] |

| Detection Systems | Polymer-based detection, avidin/biotin, anti-digoxigenin antibodies [4] [32] | Polymer-based systems offer enhanced sensitivity over biotin-based systems; specific antibodies for digoxigenin detection [4] [32] |

Advanced Technical FAQs

How can I troubleshoot persistent background issues in FISH?

Beyond standard washing optimization, periodic washing of solution jars and ensuring adequate detergent removal can help reduce background issues. Additionally, using filtered pipette tips can reduce intermittent background problems from debris being expelled onto FISH slides [19].

What are the key validation considerations for tissue array methods?

Tissue array method validation must address tumor heterogeneity concerns. Studies show that using three cores per tumor provides optimal results, with concordance rates between tissue arrays with triplicate cores and full sections exceeding 90-98% for various markers [33]. Core size selection (0.6mm, 1mm, 2mm) also affects reproducibility, with 2mm cores offering easier assessment and lower tissue loss rates during sectioning (approximately 5% vs. 20% for 0.6mm cores) [33].

How does probe design influence hybridization efficiency?

Ideal RNA probes should be between 250-1500 nucleotides, with approximately 800 nucleotides exhibiting the highest sensitivity and specificity [30]. For FISH applications, DNA fragments extracted from bacterial artificial clones (BACs) containing 100-200 Kilobase human genomic sequences are commonly used, providing the appropriate balance of specificity and signal strength [34].

What are the advantages of tissue array methods for high-throughput research?

Tissue array technology enables simultaneous analysis of hundreds or thousands of tissue specimens under identical conditions, dramatically increasing throughput while reducing reagent requirements and costs [33]. When a tissue array block containing 1,000 cores is cut 200 times, as many as 200,000 individual assays can be performed from a single block [33]. This standardization level surpasses what is achievable using standard histopathological techniques.

Core Concepts in Stringency Optimization

What is stringency and why is it critical in hybridization assays?

Stringency refers to the specificity of probe-target binding in molecular hybridization experiments. High stringency conditions ensure that only perfectly complementary nucleic acid sequences form stable hybrids, while mismatched sequences are effectively removed during washing. This is paramount for obtaining accurate and specific results in techniques like FISH, microarray analysis, and hybrid capture sequencing [1].

The stringency of a wash buffer is primarily controlled by two factors: temperature and salt concentration.

- To increase stringency: Raise the temperature and lower the salt concentration. Higher temperatures disrupt the hydrogen bonds holding together mismatched base pairs, while lower salt concentrations reduce hybrid stability by decreasing the shielding of electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged DNA backbones [1].

- To decrease stringency: Lower the temperature and raise the salt concentration. This stabilizes hybrids, allowing even partially matched sequences to remain bound [1].

How do solid surfaces influence stringency requirements?

The solid support to which probes are immobilized introduces additional constraints not present in solution-phase hybridization. Steric hindrance and electrostatic interactions with the surface can significantly alter probe accessibility and stability [22].

- Surface Effects: The negative charge of common glass substrates can create a repulsive environment for nucleic acids, dramatically reducing the local melting temperature (

Tm) of proximal probes [22]. - Spacer Role: Incorporating spacer molecules between the probe and the surface mitigates these effects. Research indicates that spacers of 45-60 atoms (approximately 8-10 nucleotides) are optimal to position the probe away from the surface's electrostatic influence [22].

- Differential Stringency: A single probe can experience different effective stringencies along its length; the segment closest to the surface is subject to higher stringency due to surface effects. This means a single wash condition may not be optimal for the entire probe [22].

Systematic Multi-Parameter Experimentation

A comprehensive multi-parametric study investigated the interplay of probe length, spacer length, and wash stringency using custom microarrays. The key parameters and findings are summarized below [22].

Table: Systematic Parameters for Probe Characterization

| Parameter | Variations Tested | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Length | Seven different lengths | Longer probes generally increase signal but decrease specificity [22]. |

| Spacer Length | Three discrete positions from the surface | Probes near the surface required higher ionic strength (4x SSC) for accurate genotyping, while distal probes required lower ionic strength (0.35x SSC) [22]. |

| Wash Stringency | Six levels of ionic strength | The optimal stringency is dependent on the probe's distance from the surface [22]. |

| G + C Content | ~20% to ~70% | Influences hybridization signal and must be accounted for in probe design and condition optimization [22]. |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Stringency Array Washer (MSAW) Setup

The following methodology enables the simultaneous testing of multiple stringency conditions.

1. Washer Design and Fabrication:

- A Multi-Stringency Array Washer (MSAW) was custom-built to process standard 8x15K Agilent arrays.

- The device consists of a bottom layer for buffer handling, an elastic polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layer defining eight individual wash chambers, and a pressure lid.

- Each chamber can be supplied with a different stringency wash buffer, allowing eight conditions to be tested on a single slide [22].

2. Probe Design and Array Configuration:

- Design probes targeting your genomic regions of interest (e.g., the phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) gene).

- Systematically vary the probe length and the length of the spacer (e.g., poly-A or specific non-hybridizing sequences) that distances the probe from the array surface.

- Spots are printed in a pre-defined layout across the array [22].

3. Hybridization and Multi-Stringency Wash:

- Hybridize the fluorescently labeled sample to the array under standard conditions.

- After hybridization, mount the slide in the MSAW.

- Pump wash buffers of varying ionic strength (e.g., from 0.35x SSC to 4x SSC) through each of the eight chambers simultaneously.

- All washes are typically performed at room temperature unless specified otherwise [22].

4. Data Analysis:

- Scan the array and analyze the hybridization signals, specificity, and dissociation curves for each probe under each stringency condition.

- Use linear regression to correlate experimental data with calculated thermodynamic parameters like

Tmand Gibbs free energy (ΔG) [22].

The workflow for this experimental setup is as follows:

Troubleshooting FAQ: Post-Hybridization Washes

Q1: My assay has high background staining. How can I reduce it?

- Cause: Inadequate stringency washing is a common cause of high background, as it fails to remove non-specifically bound probes [5].

- Solution: Ensure you are using the correct, pre-warmed stringent wash buffer. For FISH/CISH protocols, a wash with 0.4x SSC at 72°C ±1°C for 2 minutes, followed by a room temperature wash with 2x SSC/0.05% Tween for 30 seconds is often optimal [19]. Increase the temperature of the stringent wash by 1°C per slide if processing multiple slides, but do not exceed 80°C [5].

- Additional Checks:

- Include TWEEN 20 in your wash buffers to decrease background and enhance reagent spreading [19].

- Periodically clean wash solution jars and use filtered pipette tips to prevent debris from contributing to background [19].

- Verify that your probes do not contain repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu or LINE elements), which can cause elevated background. If they do, add COT-1 DNA during hybridization to block non-specific binding [5].

Q2: I am getting weak or no specific signal. What should I investigate?

- Cause: This can be due to several factors, including excessive stringency, poor probe accessibility, or reagent issues.

- Solution:

- Check Stringency: Overly harsh conditions (too high temperature or too low salt) can denature specific hybrids. Systemically reduce the wash temperature and/or increase the SSC concentration based on multi-stringency data [1] [5].

- Optimize Digestion: For tissue samples, enzyme pretreatment (e.g., pepsin digestion) is crucial. Over-digestion can eliminate signal, while under-digestion can decrease it. Optimize the digestion time (e.g., 3-10 minutes at 37°C for most tissues) for your specific sample type [5].

- Verify Reagent Activity: Confirm that enzyme conjugates (e.g., HRP) are active by mixing a drop of conjugate with a drop of substrate; a color change should occur within minutes [5].

Q3: How can I detect only perfectly matched hybrids and eliminate signals from mismatched sequences?

- Answer: To maximize specificity and detect only perfect matches, you must use high stringency conditions. This is achieved by:

- Raising the wash temperature: This disrupts the weaker hydrogen bonding in mismatched duplexes.

- Lowering the salt (SSC) concentration: This reduces the stabilization of imperfect hybrids by decreasing the shielding of electrostatic repulsion [1].

- Example: A wash buffer with 0.1x SSC at 65°C would be of higher stringency than a buffer with 2x SSC at 45°C.

Q4: Why do my probes with different designs perform inconsistently under the same wash conditions?

- Cause: Probes are affected differently by the solid surface. A probe's distance from the surface, its length, and its G+C content all influence its effective

Tmand thus its optimal wash stringency [22]. - Solution: Do not rely on a single, universal wash condition. Use a systematic multi-parameter approach during assay development to characterize each probe design. A probe placed near the surface will require a higher ionic strength wash (e.g., 4x SSC) for accurate results, while an identical probe placed further away will require a lower ionic strength (e.g., 0.35x SSC) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Reagents for Multi-Stringency Hybridization Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| SSC Buffer (Saline-Sodium Citrate) | The foundational component of stringency wash buffers; ionic strength (concentration) is a primary determinant of stringency. | Used across all cited protocols, with concentrations varied from 0.35X to 4X SSC for optimal washing [22] [19] [5]. |

| TWEEN 20 Detergent | A non-ionic surfactant added to wash buffers to reduce background staining and ensure even spreading of reagents. | Recommended in FISH protocols added to 2x SSC (e.g., 0.05% concentration) for the final wash step [19]. |

| Spacer Molecules | Molecular linkers (e.g., poly-A, specific synthetic sequences) that distance the probe from the solid surface to mitigate adverse surface effects. | Poly-A spacers or other 45-60 atom linkers were used to position probes away from the surface, dramatically improving hybridization yield [22]. |

| COT-1 DNA | Unlabeled genomic DNA rich in repetitive sequences; used as a blocking agent to prevent non-specific binding of probes to repetitive elements in the target. | Recommended for addition during hybridization to reduce high background caused by probe binding to repetitive sequences like Alu or LINE elements [5]. |

| Multi-Stringency Array Washer (MSAW) | A custom-fabricated device that allows simultaneous application of different stringency wash buffers to sub-arrays on a single slide. | Enabled the systematic study of six stringencies across eight sub-arrays, revealing the interaction between spacer length and required SSC concentration [22]. |

Advanced Workflow: Streamlined Hybrid Capture

Recent innovations have led to simplified workflows that bypass traditional bead-based capture and post-hybridization PCR. The "Trinity" workflow, for example, reduces turnaround time by over 50% while improving data quality. The key innovation is a streptavidin-functionalized flow cell, which allows the direct loading of the hybridization product onto the sequencer [35].

Table: Comparison of Traditional vs. Simplified Hybrid Capture Workflows

| Parameter | Traditional Workflow | Simplified "Trinity" Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Core Steps | Bead-based capture, multiple temperature-controlled washes, post-hybridization PCR [35]. | Direct loading of hybridization product onto a streptavidin flow cell; on-flow cell circularization and amplification [35]. |

| Total Time | 12 - 24 hours [35]. | As fast as 5 hours [35]. |

| Key Wash Steps | Multiple precise washes with different SSC buffers and temperatures [35]. | Wash steps are integrated and simplified on the flow cell surface. |

| Impact on Data | PCR amplification can reduce library complexity and introduce duplicates; potential for indel calling errors [35]. | PCR-free option available; reduces duplicates, improves library complexity and indel calling accuracy (e.g., 89% reduction in indel false positives) [35]. |

The logical progression from traditional to modern approaches is summarized below:

FAQs on Formamide Use and Troubleshooting

1. Why is formamide used in hybridization buffers? Formamide is a chemical solvent that denatures DNA by disrupting hydrogen bonds between base pairs. This action lowers the melting temperature ((T_m)) of nucleic acid duplexes, allowing hybridization to occur at lower temperatures (typically 37–45°C instead of 80–100°C). The key benefit is better preservation of cellular and tissue morphology, as lower incubation temperatures reduce heat-induced damage [36] [37] [38].

2. What are the main challenges when using formamide? Despite its benefits, formamide presents several challenges. It is a known hazardous chemical (teratogen) requiring careful handling [39]. Traditional protocols using formamide can be time-consuming, often requiring overnight hybridization for sufficient signal intensity in techniques like Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) [36]. Furthermore, the high temperatures used in standard denaturation steps can still cause deterioration of tissue texture and morphology in some delicate samples [40].

3. Are there safer and faster alternatives to formamide? Yes, researchers have developed effective alternatives. Some newer hybridization buffers substitute formamide with less hazardous solvents, enabling faster hybridization times—reducing the process from overnight to just one hour (the IQFISH method)—while eliminating the need for blocking repetitive sequences [36]. Another proven alternative is using 8 M urea in the hybridization buffer, which has been shown to improve tissue preservation, reduce non-specific background staining, and offer a safer working environment [40].

4. How does formamide affect post-hybridization wash stringency? Post-hybridization washes are critical for removing non-specifically bound probes and are a key focus of stringency optimization research. While formamide is primarily used in the hybridization buffer, the stringency of subsequent washes depends on temperature, salt concentration (SSC), and pH [19]. For example, a common stringent wash involves 0.4x SSC at 72±1°C for 2 minutes, followed by a non-stringent wash with 2x SSC/0.05% Tween at room temperature for 30 seconds [19]. The inclusion of a detergent like TWEEN 20 helps decrease background staining [19].

5. How can high background staining be resolved? High background can often be traced to the post-hybridization wash steps [5]. Ensure that stringent washes are performed correctly using SSC buffer at the recommended temperature (e.g., 75-80°C) [5]. The use of detergents like TWEEN 20 in wash buffers can reduce background [19]. Additionally, if probes contain repetitive sequences, background can be elevated; this can be mitigated by adding COT-1 DNA during hybridization to block these sequences [5]. Always use the recommended wash buffers, as rinsing with water or PBS without detergent can also lead to high background [5].

Experimental Protocols for Stringency Optimization

Protocol 1: Standard FISH with Formamide and Post-Hybridization Washes

This protocol is adapted from common cytogenetic FISH procedures [19] [5].

- Sample Pretreatment: Fix cells or tissue sections according to standard methods (e.g., Carnoy's fixative for cells, paraffin-embedding for tissues). Deparaffinize if needed, followed by antigen retrieval using heat (e.g., 98°C for 15 minutes). Digest with pepsin (e.g., 3-10 minutes at 37°C) to expose target nucleic acids [5].