Precision Timing in Hox Gene Perturbation: Strategies for Optimizing Therapeutic Control in Development and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize temporal control of Hox gene expression.

Precision Timing in Hox Gene Perturbation: Strategies for Optimizing Therapeutic Control in Development and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize temporal control of Hox gene expression. Hox genes, which are crucial for embryonic patterning and are increasingly implicated in cancer, exhibit a unique regulatory principle known as temporal collinearity—their sequential activation is timed according to their genomic order. We explore the foundational mechanisms of this 'Hox clock,' including the role of 3D chromatin dynamics, epigenetic programming, and signaling gradients. The article subsequently details methodological approaches for targeted perturbation, discusses common challenges and optimization strategies, and outlines robust validation techniques. By synthesizing current research, this guide aims to advance the precise manipulation of Hox expression for therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine and oncology.

Deconstructing the Hox Clock: Principles of Temporal Collinearity and Developmental Timing

What is Temporal Collinearity? Temporal collinearity describes the phenomenon where the order of Hox genes on a chromosome correlates with the sequential timing of their activation during embryonic development. Genes located at the 3' end of the Hox cluster are typically activated first, with gene expression proceeding in a sequential manner towards the 5' end of the cluster [1] [2]. This process is a fundamental mechanism for patterning the anterior-posterior (A-P) body axis in a wide range of animals, from invertebrates to vertebrates [1] [3].

Why is Studying its Mechanism Important? Understanding temporal collinearity is crucial for developmental biology and regenerative medicine. It provides the molecular framework for how complex body plans are built. Furthermore, this knowledge is directly applicable to targeted stem cell therapy and the in vitro culture of specific organoids, as it underpins the precise control of cellular identity and positional information during differentiation [1]. Disruptions in this finely tuned process can lead to developmental disorders and may contribute to diseases like cancer.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

A. Verifying and Detecting Temporal Collinearity

FAQ: A recent study challenged the existence of vertebrate Hox temporal collinearity. How do I confirm it in my model system? A conflict in the literature was highlighted by a 2019 review, which noted that a study by Kondo et al. questioned the existence of temporal collinearity in Xenopus laevis based on normalized RNA-seq data [1]. To reliably confirm temporal collinearity, consider these factors:

- Focus on Initial Expression: Temporal collinearity is most clearly observed during very early developmental stages (gastrula-neurula-tailbud) when the body plan is first established [1].

- Use Tissue-Specific Analysis: The initial, temporally collinear expression of Hox genes often occurs in specific tissues like the non-organizer mesoderm (NOM) or presomitic mesoderm. Using techniques like in situ hybridization to visualize expression in these tissues can prevent the masking of weak, early expression phases that might occur in whole-embryo RNA-seq analyses [1].

- Examine Multiple Species: Evidence for temporal collinearity is robust and has been demonstrated in numerous vertebrates, including mouse, chicken, catshark, and lamprey, as well as in invertebrates like the annelid Capitella sp. I [1] [2].

Problem: My data on the sequence of Hox gene activation is inconclusive.

- Possible Cause 1: Analysis of incorrect developmental time windows. Complex Hox expression profiles at later stages can obscure the initial, collinear activation sequence.

- Solution: Concentrate your analysis on the earliest stages of Hox expression, from their initial activation in the nascent mesoderm [1].

- Possible Cause 2: Sensitivity limitations of your detection method.

- Solution: Employ highly sensitive in situ hybridization protocols. This method is particularly effective as it can detect low-level initial expression in small cell populations within the early embryo, which might be missed by other techniques [1].

B. Experimental Challenges in Mechanism and Control

FAQ: What is the functional importance of temporal collinearity? The leading hypothesis is the Time-Space Translation (TST) Hypothesis. This concept proposes that the temporal sequence of Hox gene expression (temporal collinearity) lays the foundation for the spatial pattern of Hox gene expression along the anterior-posterior axis (spatial collinearity) [1]. Essentially, the ordered timing of gene activation is directly translated into an ordered spatial map of positional identity in the embryo.

Problem: I need to control the timing of specific gene expression in a synthetic system.

- Possible Cause: Lack of a mechanistic understanding of sequential gene activation.

- Solution: Investigate and utilize mechanisms that enable sequential gene activation. A "promoter relay mechanism" has been described in bacteria, where the act of transcribing one gene alters the local DNA topology (e.g., supercoiling), thereby activating a downstream promoter [4]. While not directly demonstrated in Hox clusters, this illustrates a potential physical mechanism for sequential gene activation based on genomic position. For direct temporal control in generative models, methods like TempoControl demonstrate that guiding cross-attention mechanisms can align the appearance of visual concepts with a temporal control signal, offering a computational analogy for temporal guidance [5].

FAQ: How is Hox gene expression regulated to achieve this precise timing? Hox clusters are regulated by opposing signaling gradients (e.g., Retinoic Acid (RA), FGFs, WNTs) and their embedded cis-regulatory elements [3]. Retinoic Acid Response Elements (RAREs) are particularly important; they are enhancers that provide regulatory inputs, both locally and over long distances, to coordinately regulate multiple genes within a Hox cluster [3]. The table below summarizes key signaling pathways and their components involved in this regulation.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways Regulating Hox Gene Expression

| Signaling Pathway | Key Components/Molecules | Postulated Role in Temporal Collinearity |

|---|---|---|

| Retinoic Acid (RA) Signaling | Retinoic Acid, RAREs, RA Receptors | A primary morphogen; direct transcriptional regulator of Hox genes via RAREs [3]. |

| Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Signaling | FGF ligands, FGF receptors | Establishes opposing gradients; often works alongside WNT signaling [3]. |

| WNT Signaling | WNT ligands, Frizzled receptors, β-catenin | Establishes opposing gradients; critical for reducing expression variability and ensuring robustness, as seen in C. elegans [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Temporal Collinearity Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hox Cluster BAC Clones | Provides the full genomic context for studying long-range regulatory mechanisms. | Essential for analyzing the function of enhancers like RAREs that act over large distances [3]. |

| RARE Reporter Constructs | To visualize and quantify the activity of Retinoic Acid Response Elements. | Crucial for dissecting the role of RA signaling in the coordinated activation of Hox genes [3]. |

| Specific Hox Gene Probes | For detecting mRNA transcripts via in situ hybridization. | Allows for precise spatiotemporal mapping of gene expression in early embryos [1] [2]. |

| Morpholinos / CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | For targeted knockdown or knockout of specific Hox genes or regulatory elements. | Used to test the functional necessity of specific genes or enhancers in the collinearity process. |

| Antibodies for Hox Proteins | For protein-level detection and localization. | Can reveal discrepancies between mRNA expression and functional protein presence. |

Key Experimental Protocols

A. Protocol: Mapping the Initial Hox Expression Sequence

Objective: To accurately determine the temporal sequence of Hox gene activation during early embryogenesis.

- Sample Collection: Collect embryos at very early developmental stages (gastrula to early neurula stages). The exact timing must be determined for your model organism.

- Tissue Preservation: Fix embryos immediately to preserve RNA integrity.

- Sensitive Detection:

- Method A (Spatially Resolved): Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization for a panel of Hox genes (representing anterior, central, and posterior paralog groups). This allows for the identification of the specific tissue (e.g., NOM, presomitic mesoderm) where expression initiates [1].

- Method B (Quantitative): Use microdissection or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate the specific tissues of interest, followed by RT-qPCR or RNA-seq. This provides quantitative data on expression levels.

- Temporal Ordering: Compare the earliest time point and tissue location where each Hox gene is detected. A collinear sequence will show 3' genes expressed before 5' genes in the same tissue domain.

B. Protocol: Testing the Function of a putative RARE

Objective: To verify if a suspected DNA sequence acts as a Retinoic Acid Response Element.

- Cloning: Clone the putative RARE sequence upstream of a minimal promoter driving a reporter gene (e.g., LacZ, GFP).

- Transgenesis: Introduce the reporter construct into your model system (e.g., create transgenic mice, or use electroporation in chick embryos).

- Stimulation/Inhibition: Expose embryos to Retinoic Acid or to RA receptor antagonists.

- Analysis: Monitor reporter gene expression. An active RARE will show induced reporter expression in response to RA and suppressed expression when RA signaling is inhibited [3].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

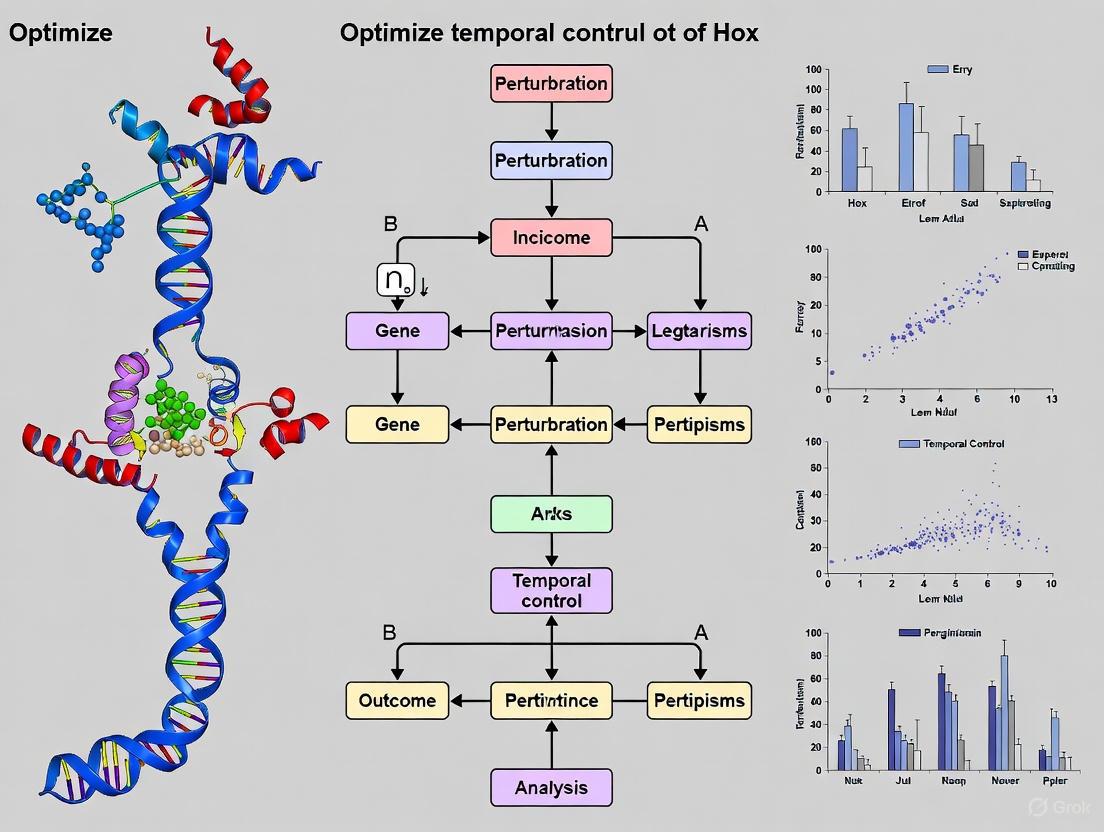

Figure 1: Regulatory Network Controlling Hox Temporal Collinearity. Opposing signaling gradients (RA, FGF, WNT) act through specific enhancers (e.g., RAREs) to coordinately activate Hox genes in a temporally collinear sequence, which in turn patterns the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis [1] [3].

Figure 2: The Time-Space Translation Mechanism. The sequential, temporal activation of Hox genes from the 3' to the 5' end of the cluster is translated into spatially ordered domains along the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo, a process known as the Time-Space Translation (TST) hypothesis [1].

Gene expression is precisely controlled through multiple, interconnected regulatory layers. For researchers investigating key developmental and disease genes, such as the Hox family, understanding and experimentally manipulating these layers—transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and epigenetic—is paramount. This guide provides a focused, troubleshooting-oriented resource for scientists aiming to perturb these control mechanisms, with an emphasis on achieving precise temporal control. Mastering these controls is essential for optimizing experiments in functional genomics, disease modeling, and therapeutic development.

Transcriptional Control: Initiating Gene Expression

FAQ: What are the core components of transcriptional initiation, and why do my reporter assays sometimes fail?

Answer: Transcriptional initiation relies on the dynamic interaction of cis-regulatory elements (e.g., promoters, enhancers) and trans-acting factors (e.g., transcription factors, co-activators). A common point of failure in reporter assays is the omission of critical distal enhancers or insulators, which can be located megabases away from the core promoter [3]. Furthermore, the intrinsic dynamics of transcription challenge the classical model of stable enhancer-promoter looping; emerging evidence suggests that rapid, transient interactions and liquid-liquid phase separations are key to activation [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Transcriptional Control

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution / Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Signal in Reporter Assays | Missing distal enhancer elements; incorrect promoter context; epigenetic silencing of vector. | Clone larger genomic fragments suspected to contain enhancers; use bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) for reporter constructs; check chromatin status of integration site [3]. |

| High Background/Non-Specific Signal | Promoter lacks necessary insulator elements; transcription factor (TF) binding promiscuity. | Flank the reporter with insulator sequences like CTCF binding sites; perform motif analysis to confirm specificity of TF binding sites [7]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Dynamic, stochastic nature of transcription; variable TF nuclear concentrations. | Increase the number of biological replicates; use single-cell imaging or sequencing approaches to capture heterogeneity; ensure consistent cell culture conditions [3]. |

| Failure to Recapitulate Endogenous Expression | Lack of 3D chromatin context in plasmid-based assays. | Utilize genomic integration techniques (e.g., CRISPR-mediated knock-in) instead of transient transfection to place the reporter in its native chromatin environment [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Mapping Transcription Factor Binding Sites In Vivo (ChIP-seq)

Purpose: To identify the genome-wide binding sites of a transcription factor under specific experimental conditions [7].

- Crosslinking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to crosslink proteins to DNA.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and sonicate chromatin to fragment DNA to an average size of 200-500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with a specific, validated antibody against your target transcription factor. Use Protein A/G beads to capture the antibody-bound complexes.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the protein-DNA complexes and reverse the crosslinks by heating.

- DNA Purification: Purify the DNA, which now represents the genomic regions bound by the TF.

- Library Prep and Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the purified DNA and subject it to high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Map sequenced reads to the reference genome and call peaks of enrichment compared to a control (e.g., Input DNA).

Key Research Reagents: Transcriptional Control

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-grade Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of specific TFs or histone modifications. | Critical for success; validate specificity using knockout/knockdown controls [7]. |

| Reporter Plasmids (GFP/Luciferase) | Quantifying promoter/enhancer activity. | pTRIPdeltaU3-EF1α-GFP is a lentiviral vector for consistent expression [8]. |

| Protein Binding Microarray (PBM) | High-throughput in vitro determination of TF binding motifs. | Uses all permutations of a 10-mer sequence to define binding specificity [7]. |

| CRISPR Activation/Inhibition | Targeted upregulation or repression of gene expression. | dCas9 fused to transcriptional effector domains (e.g., VPR, KRAB) [9]. |

Figure 1: Core Transcriptional Machinery. This diagram illustrates the fundamental components, including enhancer-promoter looping and transcription factor recruitment, that initiate gene transcription.

Post-Transcriptional Control: Regulating RNA Fate and Function

FAQ: Why is there often a poor correlation between my mRNA measurements and protein abundance?

Answer: This common discrepancy is primarily due to extensive post-transcriptional regulation [8]. Key mechanisms include:

- mRNA Stability: Cis-acting elements in the mRNA, particularly in the 3' Untranslated Region (3'-UTR) such as AU-Rich Elements (AREs), dictate half-life. AREs are often destabilizing and are bound by specific RNA-binding proteins (e.g., ARE-BPs) [8].

- Translational Efficiency: The same 3'-UTR elements can directly inhibit or enhance the recruitment of the ribosome. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are major regulators that typically bind to 3'-UTRs to repress translation and/or trigger mRNA decay [8].

- Subcellular Localization: The transport of mRNA to specific locations within the cytoplasm can control where and when a protein is synthesized.

Troubleshooting Guide: Post-Transcriptional Control

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution / Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA Level Does Not Match Protein Level | Active regulation of translation or mRNA stability by the 3'-UTR. | Clone the gene's 3'-UTR downstream of a reporter (e.g., GFP) and measure its effect on protein output using the FunREG method [8]. |

| Variable Protein Expression in Different Cell Types | Cell-type-specific expression of trans-regulatory factors (e.g., miRNAs, ARE-BPs). | Use the FunREG system to compare the post-transcriptional activity of a 3'-UTR across different cell lines or primary cells [8]. |

| Unintended Off-Targets in miRNA/siRNA Experiments | Partial complementarity to non-target mRNAs. | Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., TargetScan) to predict off-targets; employ stringent controls including rescue experiments with modified target sites. |

Experimental Protocol: FunREG - Quantifying Post-Transcriptional Regulation

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the post-transcriptional regulatory activity mediated by a 3'-UTR or miRNA in a physiologically relevant and comparable manner [8].

- Vector Construction: Clone the 3'-UTR of interest into a lentiviral vector (e.g., pTRIPdeltaU3-EF1α-GFP) downstream of the GFP reporter gene.

- Lentiviral Production: Generate lentiviral particles containing the reporter construct.

- Cell Transduction: Transduce target cells (e.g., cancer vs. normal) with a consistent, low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) to ensure single-copy integration and avoid position effects.

- Quantification (6-7 days post-transduction):

- Protein Output: Analyze cells by Flow Cytometry (FCM) to measure the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of GFP.

- mRNA Level: Extract total RNA and perform RT-qPCR to quantify GFP mRNA levels from the same transduced cell population.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the translational efficiency or mRNA stability effect by normalizing the GFP protein level (MFI) to the GFP mRNA level. Compare this ratio between different 3'-UTRs or across different cell types.

Key Research Reagents: Post-Transcriptional Control

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Reporter Vectors | Stable delivery of 3'-UTR reporters for comparative studies. | pTRIPdeltaU3-EF1α-GFP allows study in hard-to-transfect primary cells [8]. |

| miRNA Mimics & Inhibitors | Functionally enhance or block specific miRNA activity. | Controls: scrambled miRNA mimics/inhibitors. |

| siRNA against Reporter Gene | Validates specificity of post-transcriptional effects by targeting the reporter mRNA itself [8]. | e.g., anti-eGFP siRNA. |

| Flow Cytometer | Precise quantification of fluorescent reporter protein (e.g., GFP) at single-cell level. | Essential for FunREG and similar assays [8]. |

Epigenetic Control: Programming Heritable Gene Expression States

FAQ: What regulates the regulators? How are epigenetic patterns initially established?

Answer: While epigenetic marks like DNA methylation are famously maintained through cell divisions, the origin of novel patterns is a paradigm-shifting area. Traditionally, pre-existing epigenetic marks were thought to guide new modifications. However, recent research shows that genetic sequences themselves can directly instruct epigenetic patterning [10]. In plants, specific DNA sequences serve as docking sites for proteins (e.g., RIMs/REM transcription factors) that recruit DNA methylation machinery, establishing new methylation patterns during development [10]. This reveals a direct genetic code for epigenetic state.

Troubleshooting Guide: Epigenetic Control

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution / Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Gene Silencing After DNA Methylation | Incomplete or heterogeneous DNA methylation; active demethylation. | Use bisulfite sequencing to assess methylation at single-base-pair resolution; check expression of TET dioxygenases which catalyze active demethylation [11]. |

| Unstable Differentiation State | Failure to establish or maintain repressive histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3) at key loci. | Perform ChIP-seq for H3K27me3; inhibit EZH2 (the methyltransferase) to test functional requirement [11]. |

| Failed Phenocopy of Disease Mutations | Mutations affect chromatin modifiers (e.g., DNMT3A, TET2) leading to genome-wide epigenetic drift. | Profile genome-wide DNA methylation (e.g., Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing) in your model compared to primary tissue [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing DNA Methylation by Bisulfite Sequencing

Purpose: To create a base-resolution map of DNA methylation (5-methylcytosine) in a genomic region of interest.

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from your sample.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite. This chemical reaction deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which are read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain as cytosines.

- PCR Amplification: Design PCR primers specific for the bisulfite-converted DNA of your target region and amplify it.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Clone the PCR product and Sanger sequence multiple clones, or perform next-generation sequencing. Map the C-to-T conversions to determine the methylation status of each cytosine.

Key Research Reagents: Epigenetic Control

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors | Chemically induce global DNA hypomethylation. | 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) - FDA approved for MDS [11]. |

| Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitors | Probe the function of specific histone marks. | EZH2 inhibitors (e.g., GSK126) to reduce H3K27me3 [11]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Prepares DNA for methylation analysis by converting unmethylated C to U. | Critical for BS-seq and methylation-specific PCR. |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Increase global histone acetylation, generally promoting gene expression. | Trichostatin A, Vorinostat; used to test if a gene is silenced by low acetylation [11]. |

Integrated Workflow for Perturbing Hox Gene Regulation

The following diagram and table provide a consolidated experimental strategy for perturbing Hox gene expression, integrating the three regulatory layers.

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Hox Gene Perturbation. This diagram outlines a logical strategy for targeting different regulatory layers and measuring the cascading effects on Hox gene expression and function.

| Experimental Model / System | Key Readout / Parameter | Quantitative Result | Relevance to Control Layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPM1-mutant AML [12] | HOX A/B cluster gene expression | Pathognomonic upregulation (several-fold increase) | Transcriptional & Epigenetic |

| FunREG in Liver Cancer [8] | Translation efficiency via 3'-UTR | 3-fold increase in HepG2 vs. normal hepatocytes | Post-Transcriptional |

| FunREG in Liver Cancer [8] | mRNA stability via 3'-UTR | >2-fold increase in HepG2 vs. normal hepatocytes | Post-Transcriptional |

| CRISPR/Cas9 in Parhyale [9] | Homeotic transformations | Specific transformations upon Ubx, Antp, Scr knockout | Transcriptional (TF function) |

| BMP/anti-BMP in Xenopus [13] | Hox spatial collinearity | Anterior-to-posterior sequence of Hox zones induced | Transcriptional & Signaling |

Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Gene Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function / Application in Hox Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | Menin-MLL interaction inhibitors | Suppress HOX expression in NPM1mut and MLLr AML by disrupting chromatin-based transcription [12]. |

| Chemical Inhibitors | HDAC inhibitors (e.g., Trichostatin A) | Increase histone acetylation to test if Hox genes are poised in a repressed state [11]. |

| CRISPR Tools | Somatic CRISPR mutagenesis [9] | Rapidly determine Hox gene function in vivo in emerging model organisms (e.g., Parhyale). |

| Reporter Systems | Lentiviral 3'-UTR reporters (FunREG) [8] | Quantify post-transcriptional regulation of Hox genes or their targets in different cell states. |

| Live-Cell Reporting | GFP reporter plasmids [14] | Monitor real-time promoter activity dynamics of Hox genes or their regulators with high temporal resolution. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My Hi-C data on Hox clusters is noisy and compartment calls are inconsistent. How can I improve data quality?

- Problem: High background noise in chromatin conformation data.

- Solution: Ensure high sequencing depth (>500 million reads per sample for mammalian genomes). Use biological replicates (n≥3) and stringent statistical filters (e.g., Fit-Hi-C for significant contact calls). Validate compartment transitions with orthogonal methods like Dam-ID for nuclear lamina association [15] or ATAC-seq for accessibility [16].

- Thesis Context: High-quality data is crucial for detecting the subtle, dynamic compartment switches (A-to-B or B-to-A) that underlie temporal Hox collinearity, a core focus of temporal control research.

FAQ: I've knocked out a chromatin regulator, but I don't see the expected Hox gene derepression or compartment change. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Expected phenotypic changes are not observed after genetic perturbation.

- Solution: Consider functional redundancy. Some regulators, like SMCHD1, maintain heterochromatin extensively; their loss may be buffered by other mechanisms [15]. Verify knockout efficiency at protein level and confirm the target's relevance in your cell model (e.g., SMCHD1 binds Lamin B1 in myoblasts but not all factors regulate Hox in all cells [15]). Use multiple complementary assays (e.g., RNA-seq, Hi-C, ChIP) to fully characterize the phenotype.

FAQ: How can I identify conserved regulatory elements near Hox genes when sequence alignment fails?

- Problem: Difficulty finding orthologous enhancers in distantly related species due to sequence divergence.

- Solution: Move beyond alignment-dependent methods. Employ synteny-based algorithms like Interspecies Point Projection (IPP), which uses flanking alignable regions (anchor points) to project genomic coordinates across species, identifying "indirectly conserved" elements [17]. This can increase the identification of conserved enhancers by more than fivefold [17].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping 3D Chromatin Architecture with Hi-C

- Application: Capturing genome-wide compartmentalization (A/B) and TAD structures at Hox loci [16] [18].

- Workflow:

- Crosslink cells with formaldehyde to fix protein-DNA interactions.

- Digest chromatin with a restriction enzyme (e.g., MboI or DpnII).

- Fill ends and mark with biotinylated nucleotides.

- Ligate crosslinked DNA fragments to create chimeric junctions.

- Reverse crosslinks, purify DNA, and shear it.

- Pull down biotinylated ligation products for sequencing library preparation.

- Key Controls: Include an untreated control and process in parallel to assess background ligation. Use replicate experiments to ensure robustness.

Protocol 2: Profiling Protein-Genome Interactions with Dam-ID

- Application: Mapping the genomic binding of nuclear lamina components (Lamin B1) and chromatin-associated proteins (SMCHD1) to define heterochromatin domains [15].

- Workflow:

- Express a protein of interest fused to DNA Adenine Methyltransferase (Dam) in cells.

- Allow the fusion protein to methylate adenines in its genomic vicinity.

- Extract genomic DNA and digest with methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme DpnI.

- Sequence the digested fragments to map methylation sites, which reflect protein localization.

- Key Controls: Always express Dam enzyme alone as a control to identify background methylation patterns. Normalize all data to this Dam-only profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Essential materials for investigating 3D chromatin dynamics in Hox gene regulation.

| REAGENT | FUNCTION & APPLICATION |

|---|---|

| HIRA Knock-out (KO) Cells [16] | To study the role of H3.3 deposition in defining early replication zones and A-compartment integrity independently of transcription. |

| SMCHD1 Knock-out (KO) Cells [15] | To investigate the role of this SMC protein in anchoring heterochromatin to the nuclear lamina and maintaining B-compartments. |

| Anti-H3K27me3 Antibody [18] | Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to mark and isolate facultative heterochromatin and inactive Hox genes. |

| Anti-H3K4me3 Antibody [18] | ChIP reagent to mark and isolate transcriptionally active chromatin and active Hox gene promoters. |

| Anti-Lamin B1 Antibody [15] | For immunofluorescence and Dam-ID to label the nuclear lamina and identify lamina-associated domains (LADs). |

| pBABEDam Plasmid System [15] | For generating Dam and Dam-fusion constructs to perform Dam-ID mapping of protein-genome interactions. |

| Tn5 Transposase (for ATAC-seq) [16] [17] | To assess genome-wide chromatin accessibility and identify open, potentially active regulatory elements. |

Visualizing the Compartment Transition and Key Experiments

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Hox Gene Activation Process illustrates the transition from an inactive, single-compartment state to an active, bimodal 3D organization, which is memorized in specific spatial domains [18].

Diagram 2: Multi-Assay Investigation Workflow outlines the core process for determining how a genetic perturbation affects 3D chromatin organization and gene expression [16] [15].

Key Signaling Pathways and Their Roles in Axial Patterning

The formation of the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis in vertebrates is orchestrated by the coordinated activity of several key signaling pathways. The table below summarizes the primary functions and interactions of these pathways.

| Signaling Pathway | Primary Role in Axial Patterning | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| BMP/anti-BMP | Mediates a timing mechanism (Time-Space Translation) that converts Hox temporal collinearity into spatial collinearity [19]. | Anti-BMP signals from the organizer fix sequential Hox values; inhibited by FGF, Wnt, and RA in posterior placode induction [20]. |

| FGF | Maintains caudal progenitor state; prevents premature specification and EMT of neural crest cells; inhibits posterior lateral line placode induction [21] [20]. | Forms an oppositional gradient with RA; its decline is required for neural crest specification; crosstalk with Wnt and Notch [21] [22]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and emigration of neural crest cells; required for posterior lateral line placode induction [21] [20]. | Opposes FGF signaling; inhibits FGF, Wnt, and Bmp signaling in placode induction [21] [20]. |

| Wnt | Key posteriorizing signal; influences NMP fate decisions and Hox gene expression; inhibits posterior lateral line placode induction [22] [20]. | Crosstalk with FGF and Notch signaling; part of the core NMP regulatory network [22]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents used to manipulate these signaling pathways in experimental models.

| Reagent / Tool | Target Pathway | Primary Function | Example Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SU5402 | FGF | FGFR1 inhibitor; blocks FGF/MAPK signaling [21]. | To caudalize neural tube and induce premature neural crest cell EMT [21]. |

| Noggin | BMP | BMP antagonist; source of anti-BMP signal [19]. | To study Time-Space Translation by blocking BMP timer at specific Hox values [19]. |

| CHIR99021 (CHIR) | Wnt | GSK-3 inhibitor; Wnt pathway agonist [22]. | Used with FGF2 to induce NMP-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells [22]. |

| Dorsomorphin | BMP | Small molecule BMP inhibitor [20]. | To inhibit BMP signaling during posterior lateral line placode induction studies [20]. |

| DEAB (Diethylaminobenzaldehyde) | RA | Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor; blocks RA synthesis [20]. | To inhibit RA synthesis and study its requirement in placode induction [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: The anterior-posterior pattern of Hox gene expression in my model is disrupted. The temporal-to-spatial conversion seems faulty. What could be the core mechanism involved?

A: The core mechanism for converting a temporal Hox sequence into a spatial A-P pattern is BMP-anti-BMP mediated Time-Space Translation (TST) [19].

- Underlying Principle: A BMP-dependent timer (manifesting as Hox temporal collinearity) operates in the non-organizer mesoderm. As cells move during convergence-extension, they come within range of anti-BMP signals (e.g., Noggin) emitted by the organizer. This interaction "fixes" their Hox identity at a specific value, creating a spatially collinear pattern [19].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify the BMP signaling gradient: Check the activity range of BMP and its antagonists in your system. Ectopic application of an anti-BMP source (like Noggin) at different stages should truncate the axis at sequentially more posterior positions [19].

- Check morphogenetic movements: Disruptions in convergence-extension movements can prevent cells from reaching the anti-BMP signaling zone at the correct time, desynchronizing the TST mechanism.

Q2: My neural crest cells are emigrating from the neural tube prematurely. Which pathways should I investigate?

A: This is a classic phenotype of disrupted FGF and Retinoic Acid (RA) opposition [21].

- Root Cause: Caudal FGF signaling actively prevents premature specification of neural crest cells and their subsequent epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Rostral RA signaling promotes EMT. An imbalance, such as reduced FGF or elevated RA signaling, can lead to premature emigration [21].

- Solution:

- Monitor the FGF gradient: Use markers like FGF8 to ensure its signaling is high enough caudally to repress neural crest specifiers like Snail2.

- Inhibit FGF signaling pharmacologically: Application of the FGFR1 inhibitor SU5402 can be used as a positive control, as it is known to induce premature neural crest cell EMT [21].

- Check downstream effectors: FGF and RA control EMT in part by modulating the BMP and Wnt signaling pathways. Examine the expression of key players in these cascades [21].

Q3: I am differentiating human pluripotent stem cells toward neuromesodermal progenitors (NMPs), but the efficiency is low. What are the critical signaling pathways for induction?

A: The standard protocol for NMP induction relies on simultaneous activation of Wnt and FGF signaling [22].

- Protocol Core: Treat cells with a Wnt agonist (like CHIR99021) and recombinant FGF2 for several days. This co-activation drives the expression of key NMP markers like Sox2, T (Brachyury), and Tbx6 [22].

- Optimization Tips:

- Confirm reagent activity: Ensure your small molecule agonists and growth factors are fresh and active.

- Investigate Notch signaling: Recent evidence indicates that Notch signaling is also crucial for the induction of NMPs from hPSCs. Notch attenuation during induction impairs the activation of pro-mesodermal transcription factors and HOX genes. Ensure your culture system supports Notch signaling [22].

- Monitor HOX gene activation: Robust HOX gene activation in a 3'-to-5' collinear fashion is a key indicator of high-quality NMP induction and subsequent posterior axial elongation [22].

Q4: The posterior lateral line placode (pLLp) in my zebrafish model fails to induce. What signaling environment is required?

A: pLLp induction has a unique signaling requirement compared to other placodes: it needs Retinoic Acid and the inhibition of Fgf, Wnt, and Bmp signaling [20].

- Required Condition: RA is strictly required for pLLp specification. Its function, in part, is to inhibit the activities of Fgf, Wnt, and Bmp, which all act to suppress pLLp formation. The boundaries of the pLLp are also limited by Wnt and Bmp activities [20].

- Action Plan:

- Validate RA signaling: Check for the presence and distribution of RA. Inhibition of RA synthesis (e.g., with DEAB) should prevent pLLp induction [20].

- Inhibit multiple pathways: Ensure that Fgf, Wnt, and Bmp signaling are sufficiently low in the region of pLLp induction. Ectopic activation of any of these three pathways can inhibit placode formation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental biological significance of the Hox-PBX interaction?

The Hox-PBX interaction is a crucial partnership in developmental biology and disease. Homeoprotein products of the Hox gene family are transcription factors that pattern animal embryos through transcriptional regulation of target genes. However, many Hox proteins have intrinsically weak DNA-binding activity on their own and require cofactors for stable interactions with DNA [23]. The PBX1A protein was identified as a putative HOX cofactor that participates in cooperative DNA binding with specific Hox proteins like HOXA1 and HOXD4 [23]. This interaction is mediated through a conserved YPWMK pentapeptide motif found N-terminal to the homeodomain of many Hox proteins [23]. The biological significance extends beyond development, as the disruption of this interaction is now recognized as a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment [24] [25].

Q2: Which HOX proteins interact with PBX, and what determines this specificity?

The interaction specificity follows a general paralog-group pattern, though recent research reveals greater complexity. Initially, researchers observed that three Abdominal-B class HOX proteins failed to cooperate with PBX1A, and the interacting domain was mapped to the YPWMK pentapeptide motif, which is absent from the Abdominal-B class [23]. However, a 2018 systematic analysis demonstrated that the vast majority of human HOX proteins use diverse TALE-binding sites, and the usage mode of these sites is highly context-specific [26]. The previously characterized YPWMK motif becomes dispensable in the presence of MEIS cofactors for all except the two most anterior paralog groups [26]. Researchers have also identified additional paralog-specific TALE-binding sites that are used in a highly context-dependent manner [26].

Q3: Why is the Hox-PBX interface considered "druggable," and what evidence supports this?

The Hox-PBX interface is considered druggable because multiple research groups have successfully designed molecules that disrupt this interaction with functional consequences in disease models. Evidence includes:

- Peptide-based disruption: A synthetic peptide, HXP4, was designed to disrupt HOX-PBX interaction, leading to growth inhibition of leukemic cells. At 60μM, HXP4 was cytotoxic, while lower doses (6μM) had a cytostatic effect [24].

- Small molecule inhibitors: Researchers designed small molecule compounds capable of docking to the interface between PBX1 and its cognate DNA target sequence. The lead compound T417 suppressed self-renewal and proliferation of cancer cells expressing high PBX1 levels and re-sensitized platinum-resistant ovarian tumors to carboplatin [27].

- Cancer vulnerability: Cancer cells with elevated PBX1 signaling are particularly vulnerable to PBX1 withdrawal, making this interaction a promising therapeutic target [27].

Q4: What are the key technical challenges in studying Hox-PBX interactions?

The main technical challenges include:

- Context-dependent interactions: HOX proteins use diverse and context-dependent motifs to interact with TALE class cofactors, making results highly dependent on experimental conditions [26].

- Complex formation: HOX and PBX often form larger complexes with other cofactors like MEIS, which significantly influences their interaction mode and DNA binding specificity [26] [25].

- Compensation mechanisms: The high level of functional redundancy between HOX genes can mask phenotypic effects when individual interactions are disrupted [25].

- Detection limitations: Some interaction interfaces may require specific post-translational modifications or cellular compartments that are difficult to replicate in vitro [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Disruption of Hox-PBX Dimerization: Experimental Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Hox-PBX Disruption Strategies

| Approach | Mechanism | Evidence | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HXP4 Peptide | Disrupts HOX-PBX protein interaction | Cytostatic at 6μM, cytotoxic at 60μM in leukemic cells [24] | High specificity, well-defined mechanism | Poor pharmacokinetics, cellular delivery challenges |

| T417 Small Molecule | Docks at PBX1-DNA interface, preventing complex formation | Suppressed cancer cell self-renewal, re-sensitized resistant tumors [27] | Favorable toxicity profile, oral bioavailability | Potential off-target effects at high concentrations |

| HXR9 Peptide | Targets HOX-PBX dimer interface | Effective in prostate, breast, renal, ovarian, lung cancer, melanoma [25] | Broad efficacy across cancer types | Similar peptide limitations as HXP4 |

Experimental Workflow for Targeting Hox-PBX Interactions

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 2: Hox-PBX Research Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent interaction results | Context-dependent binding motifs [26] | Include MEIS in assays; Test multiple cellular contexts | Characterize all TALE cofactors present in your system |

| Poor inhibitor efficacy | Incorrect paralog targeting; Compensation mechanisms | Validate specific Hox paralogs expressed; Use combination approaches | Perform comprehensive Hox expression profiling first |

| Cellular toxicity issues | Off-target effects; Excessive potency | Titrate inhibitor concentration; Use controlled delivery systems | Implement dose-response curves with appropriate controls |

| Variable transcriptional outcomes | Presence of different HOX cofactors [25] | Map complete interactome; Consider tissue-specific partners | Analyze protein complexes by co-IP before functional assays |

| Resistance to disruption | Alternative dimerization interfaces | Target multiple interaction surfaces; Use combination therapy | Understand paralog-specific binding mechanisms [26] |

Hox-PBX Interaction Detection and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hox-PBX Interaction Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Disruptors | HXP4 peptide, T417 small molecule, HXR9 | Experimental disruption of Hox-PBX dimers | Select based on delivery method (peptide vs. small molecule) needs [27] [24] |

| Detection Assays | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) | Validate direct binding and compound engagement | EMSA for in vitro DNA binding, CETSA for cellular target engagement [27] |

| Live-Cell Imaging | Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) | Visualize protein interactions in live cells | Reveals distinctive intracellular patterns for interactions [28] |

| Expression Vectors | Full-length HOX/PBX constructs, Mutated versions (e.g., YPWMK mutants) | Functional studies and mechanism investigation | YPWMK mutation abolishes cooperative interaction with PBX1A [23] |

| Validation Tools | Co-immunoprecipitation antibodies, PBX1-DNA interface probes | Confirm specific interaction disruption | Critical for verifying on-target effects of inhibitors |

Intervention Toolkit: Methodologies for Targeted Hox Perturbation and Pathway Modulation

FAQs: Core Concepts and Workflow Design

Q1: How do chromatin-targeting approaches fit into research on the temporal control of Hox gene expression? Hox genes are master regulators of anterior-posterior patterning, and their sequential, collinear expression is a fundamental concept in developmental biology [29]. Chromatin-targeting approaches allow researchers to directly modify the epigenetic landscape at these gene loci. By rewriting specific epigenetic marks—such as DNA methylation or histone modifications—you can perturb the "open" or "closed" state of chromatin to investigate the causal mechanisms that control the precise timing of Hox gene activation during development [30] [31]. This provides a direct experimental tool to move beyond correlation and test hypotheses on how sequential opening is achieved.

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between enzymatic and sonication-based chromatin fragmentation in ChIP? The choice between these two methods for shearing chromatin is a critical early decision that impacts your entire experimental workflow and outcomes.

- Enzymatic Fragmentation (e.g., with Micrococcal Nuclease, MNase): This enzyme preferentially digests the linker DNA between nucleosomes. It is highly reproducible and efficient but can introduce a bias towards nucleosome-bound regions, potentially under-representing areas with fewer nucleosomes [32].

- Sonication (Mechanical Shearing): This method uses physical energy to randomly break chromatin into smaller pieces. It provides more randomized fragments but requires dedicated, optimized equipment and carries a risk of over-sonication, which can damage chromatin and denature antibody epitopes [33] [32].

Q3: My ChIP yields low signal at my target Hox gene region. What are the primary factors I should investigate? Low enrichment is a common challenge. A systematic troubleshooting approach is recommended, focusing on these key areas [33] [34]:

- Chromatin Fragmentation & Quality: Run an agarose gel to confirm your chromatin is properly fragmented to the ideal size of 200-750 base pairs. Under-fragmentation leads to high background, while over-fragmentation (especially to mono-nucleosome length) can diminish signal for amplicons >150 bp [33].

- Antibody Specificity and Affinity: This is often the culprit. Ensure your antibody is validated for ChIP and specifically recognizes your target epitope (e.g., a specific histone methylation mark) without cross-reactivity [32].

- Crosslinking Efficiency: Both under- and over-crosslinking can prevent efficient immunoprecipitation. Optimize formaldehyde crosslinking time, typically between 10-30 minutes [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Failed Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

| Problem Description | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low chromatin concentration [33] | Insufficient starting cells/tissue; Incomplete cell lysis. | Accurately count cells before cross-linking; Visualize nuclei under a microscope after lysis to confirm complete disruption [33] [34]. |

| Chromatin under-fragmented [33] | Over-crosslinking; Insufficient sonication/MNase. | Shorten crosslinking time; Conduct a sonication time-course or MNase concentration gradient [33]. |

| Chromatin over-fragmented [33] | Excessive sonication; Too much MNase. | Use minimal sonication cycles needed; Optimize MNase concentration to avoid mono-nucleosome predominance [33]. |

| High background noise [34] | Non-specific antibody binding; Insufficient washing. | Include a pre-clearing step; Block beads with BSA/salmon sperm DNA; Increase wash stringency or number [34]. |

| No enrichment at positive control locus [32] | Poor antibody performance; Epitope masked. | Include a positive control antibody (e.g., for H3K4me3); Use oligo/polyclonal antibodies for better epitope recognition [32]. |

Problem: Optimizing for Hox Gene-Specific Challenges

| Problem Description | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Detecting signal in precise anatomical regions [29] | HOX codes are highly region-specific; bulk analysis dilutes signal. | Use micro-dissection or single-cell/spatial transcriptomics approaches to isolate region-specific cell populations [29]. |

| Resolving temporal sequence of opening | Standard ChIP provides a single snapshot. | Design a time-course experiment; synchronize cells or use developmental model systems like gastruloids to track changes [35]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol: Optimization of Chromatin Fragmentation by Sonication

This protocol is essential for achieving the ideal chromatin fragment size for high-resolution ChIP, which is critical for probing dense gene clusters like Hox [33].

- Prepare Cross-linked Nuclei: From 100–150 mg of tissue or 1x10⁷–2x10⁷ cells, prepare nuclei as per standard protocols.

- Sonication Time-Course: Resuspend the nuclear pellet in 1 ml of ChIP Sonication Nuclear Lysis Buffer. Subject the sample to sonication (e.g., using a Branson Digital Sonifier 250). Remove 50 µl aliquots after different durations (e.g., after each 1-2 minutes of cumulative sonication).

- Reverse Cross-links and Purify DNA: For each aliquot:

- Clarify by centrifugation at 21,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C.

- Transfer supernatant to a new tube. Add 100 µl nuclease-free water, 6 µl 5 M NaCl, and 2 µl RNase A. Incubate at 37°C for 30 min.

- Add 2 µl Proteinase K and incubate at 65°C for 2 hours [33].

- Analyze DNA Fragment Size: Run 20 µl of each sample on a 1% agarose gel with a 100 bp DNA marker.

- Determine Optimal Conditions: The ideal condition generates a DNA smear where approximately 90% of fragments are <1 kb for cells fixed for 10 minutes. For tissue fixed for 10 minutes, aim for ~60% of fragments <1 kb [33]. Avoid over-sonication, characterized by >80% of fragments being shorter than 500 bp.

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps and decision points in this optimization process.

Protocol: Optimization of Enzymatic Chromatin Fragmentation

For researchers preferring enzymatic digestion, this protocol details how to titrate Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) to achieve ideal fragmentation [33].

- Prepare Nuclei: Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 125 mg of tissue or 2x10⁷ cells (equivalent to 5 IPs).

- Set Up Reactions: Transfer 100 µl of nuclei prep into five 1.5 ml tubes.

- Dilute Enzyme: Dilute stock MNase 1:10 in 1X Buffer B + DTT.

- Titrate Enzyme: Add 0 µl, 2.5 µl, 5 µl, 7.5 µl, or 10 µl of the diluted MNase to the five tubes. Mix and incubate 20 min at 37°C with frequent mixing.

- Stop Reaction & Lyse Nuclei: Stop with 10 µl of 0.5 M EDTA. Pellet nuclei, resuspend in 200 µl of 1X ChIP buffer + PIC, and lyse by brief sonication or Dounce homogenization.

- Analyze DNA: Clarify lysates, reverse cross-links on 50 µl of sample as in the sonication protocol, and analyze DNA on a 1% agarose gel.

- Calculate Stock Volume: The volume of diluted MNase that produces 150-900 bp fragments is equivalent to 10 times the volume of MNase stock needed for one IP. For example, if 5 µl of diluted MNase worked best, use 0.5 µl of stock MNase per IP [33].

The decision flow for choosing and optimizing the fragmentation method is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials and reagents crucial for successful chromatin analysis experiments, based on the cited troubleshooting guides and protocols.

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) [33] | Enzymatic digestion of chromatin for ChIP. | Highly sensitive to enzyme-to-cell ratio; requires careful titration for each cell/tissue type [33]. |

| Formaldehyde [32] | Reversible crosslinking of protein-DNA complexes. | Crosslinking time (10-30 min) is critical; over-crosslinking impedes fragmentation [34]. |

| Protein A / G Beads [34] | Capture of antibody-target complexes. | Ensure compatibility with your antibody's host species; use magnetic beads to reduce non-specific binding [34]. |

| ChIP-Grade Antibodies [32] | Specific immunoprecipitation of target protein or histone mark. | Must be validated for ChIP; check for cross-reactivity with similar epitopes (e.g., different methylation states) [32]. |

| Protease Inhibitors [32] | Prevent degradation of proteins and complexes during lysis. | Essential for maintaining complex integrity; add fresh to lysis buffers [32]. |

| Dounce Homogenizer [33] | Mechanical disaggregation of tissues and lysis of nuclei. | Strongly recommended for brain tissue; improves lysis efficiency for many tissues [33]. |

| Mesp2 Reporter Cell Line [35] | Live imaging of anterior-posterior patterning in model systems like gastruloids. | Enables study of morphogenesis and gene expression coupling in a scalable system [35]. |

HOX genes are a family of transcription factors that play critical roles in embryonic development and are profoundly dysregulated in a wide range of cancers [25]. A key aspect of their oncogenic function is their interaction with the PBX cofactor; this dimerization enhances DNA binding specificity and is essential for the transcriptional regulation of target genes that drive proliferation, block apoptosis, and promote metastasis [36] [25]. The synthetic peptide HXR9 is a competitive inhibitor designed to disrupt the HOX/PBX interaction, thereby inducing apoptosis in malignant cells [37] [36]. This technical support center provides a comprehensive resource for researchers utilizing HXR9 in their experimental workflows, offering detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs to ensure robust and reproducible results.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

1. What is the molecular mechanism of action of HXR9? HXR9 mimics the highly conserved hexapeptide region (YPWM) of HOX proteins that is required for binding to the PBX cofactor [36] [25]. By acting as a competitive antagonist, HXR9 blocks the formation of the HOX/PBX heterodimer. This disruption prevents the transcriptional complex from activating pro-oncogenic target genes, leading to the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells that are dependent on these HOX/PBX dimers for survival [36].

2. In which cancer cell types has HXR9 demonstrated efficacy? HXR9 has shown selective cytotoxicity in a variety of cancer cell lines, while demonstrating less effect on normal cells. Proven efficacy has been observed in:

- Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) and potentially malignant oral lesion (PMOL) cells [37].

- Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) cells (e.g., KYSE70, KYSE150, KYSE450) [36].

- Other solid and haematological malignancies, including prostate, breast, renal, ovarian, and lung cancer, melanoma, myeloma, and acute myeloid leukaemia [25].

3. What is the critical control peptide for HXR9 experiments?

The standard control peptide is CXR9. This peptide differs from HXR9 by a single amino acid substitution (proline for alanine: WYPAMKKHH), which ablates its ability to bind PBX while retaining the cell-penetrating arginine tail (RRRRRRRRR) [37] [36]. The use of CXR9 is essential for controlling for non-specific effects caused by the delivery of a cationic peptide into cells.

4. How does HXR9 treatment link to apoptotic pathways? Treatment with HXR9 leads to a cascade of molecular events culminating in apoptosis. Key observed outcomes include:

- Transcriptional Alteration: RNA-seq analyses in ESCC cells indicate that HXR9 treatment alters the transcription of genes involved in JAK-STAT signaling and apoptosis [36].

- c-Fos Upregulation: In some OSCC and PMOL cells, HXR9 treatment increases the expression of c-Fos mRNA and protein, which can have pro-apoptotic functions in certain contexts [37].

- Caspase-3 Activation: Western blot analysis in ESCC cells has confirmed the cleavage and activation of caspase-3, a key executioner protease in the apoptotic pathway, following HXR9 treatment [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Low or Inconsistent Cell Death in Sensitive Cell Lines

- Potential Cause: Instability or degradation of the HXR9 peptide stock solution.

- Solution:

- Preparation: Dissolve the lyophilized peptide in sterile ddH₂O to a high concentration (e.g., 20 mmol/L) as a stock [36]. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting the stock.

- Storage: Store aliquots at -20°C or -80°C. Peptides are susceptible to hydrolysis and proteolysis; for long-term storage, consider lyophilization [38].

- Handling: Use siliconized low-retention tubes to prevent nonspecific adsorption of the peptide to vial walls, which can significantly reduce the effective concentration [38].

- Potential Cause: Sub-optimal dosing or treatment duration.

- Solution:

- Perform a dose-response curve for each new cell line. Typical working concentrations in the literature range from 10 to 160 μmol/L, with treatment times from 2 hours to 24 hours [37] [36].

- Always include the CXR9 control peptide at the same concentrations to confirm that observed effects are specific to HOX/PBX disruption.

Problem 2: High Background Toxicity in Normal Cells or with Control Peptide

- Potential Cause: Non-specific effects from the poly-arginine (R9) cell-penetrating motif.

- Solution:

- Titrate the peptide to find the lowest effective dose that kills cancer cells while sparing normal cells. Normal oral keratinocytes (iNOKs) have been shown to be insensitive to HXR9 at concentrations toxic to OSCC cells [37].

- Ensure the control peptide CXR9 is used in every experiment. High toxicity with CXR9 indicates non-specific, sequence-independent effects.

Problem 3: Difficulty in Reproducing Apoptosis Assay Results

- Potential Cause: Variability in cell confluence and health at the time of treatment.

- Solution:

- Maintain cells in the logarithmic growth phase and do not allow cultures to exceed 70-80% confluence before treatment [37].

- Use consistent cell seeding densities and passage numbers across experiments.

- Utilize multiple complementary assays to confirm apoptosis (e.g., Annexin-V/PI flow cytometry alongside caspase-3 western blotting) [36].

Problem 4: Inefficient HOX/PBX Disruption Despite HXR9 Treatment

- Potential Cause: Inefficient cellular uptake of the peptide.

- Solution:

- The R9 tag is generally efficient, but ensure the peptide is properly dissolved and not aggregated.

- Verify disruption functionally (e.g., via Co-Immunoprecipitation) and phenotypically (e.g., apoptosis assay) to confirm successful target engagement [36].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Protocol: HXR9 Treatment for Viability and Apoptosis Assays

This workflow outlines the standard procedure for treating cells with HXR9 to assess its biological effects.

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Plating: Plate cells at an appropriate density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well for a 96-well CCK-8 assay [36] or 1 × 10⁶ cells/well for a 6-well apoptosis assay [36]) in their standard growth medium.

- Incubation: Allow cells to adhere and resume logarithmic growth for 12-24 hours.

- Peptide Preparation: Thaw HXR9 and CXR9 stock solutions (e.g., 20 mmol/L in ddH₂O) on ice. Dilute to the desired working concentrations in pre-warmed serum-free or complete medium. Note: Prepare fresh dilutions for each experiment.

- Treatment: Remove the old medium from the plated cells and replace it with the medium containing HXR9, CXR9, or vehicle control.

- Incubation with Peptide: Incubate cells for the required time. Typical treatment durations are:

- Harvesting and Analysis: Proceed with your chosen downstream analysis.

Downstream Analysis: Apoptosis Measurement via Flow Cytometry

This protocol follows the "Harvest Cells" step in the core workflow.

Materials:

- Annexin V Binding Buffer

- Annexin V-FITC antibody

- Propidium Iodide (PI) solution

- Flow cytometer

Procedure:

- After HXR9 treatment, collect both suspended and adherent cells (using EDTA-free trypsin to avoid false-positive PI staining) [36].

- Wash cells once with cold PBS.

- Resuspend the cell pellet (1 × 10⁵ cells) in 100 μL of Annexin V Binding Buffer.

- Add 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL of PI to the cell suspension.

- Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Add an additional 400 μL of Annexin V Binding Buffer and analyze by flow cytometry within 1 hour.

- Gating Strategy:

- Viable cells: Annexin V⁻/PI⁻

- Early apoptotic cells: Annexin V⁺/PI⁻

- Late apoptotic cells: Annexin V⁺/PI⁺

- Necrotic cells: Annexin V⁻/PI⁺

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from published studies using HXR9.

Table 1: Efficacy of HXR9 in Different Cancer Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Cancer Type | Assay | Reported EC₅₀ / Effect | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D35 | Potentially Malignant Oral Lesion (PMOL) | LDH Cytotoxicity | ~12.5 μM | [37] |

| B16 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) | LDH Cytotoxicity | ~25 μM | [37] |

| B56 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) | LDH Cytotoxicity | 151 μM | [37] |

| KYSE450 | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) | CCK-8 Viability | ~60 μM (approx. 50% inhibition) | [36] |

| Immortalized Normal Oral Keratinocytes (iNOK) | Normal | LDH Cytotoxicity | Insensitive up to 100 μM | [37] |

Table 2: Key Molecular and Apoptotic Markers Altered by HXR9 Treatment

| Marker | Observed Change Post-HXR9 | Experimental Method | Interpretation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOX/PBX Dimer | Decreased | Co-Immunoprecipitation | Successful target engagement | [36] |

| c-Fos mRNA | Increased | qRT-PCR | Early transcriptional response to stress | [37] |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 | Increased | Western Blot | Activation of executioner apoptosis pathway | [36] |

| Annexin V+ Cells | Increased | Flow Cytometry | Induction of phosphatidylserine externalization (apoptosis) | [37] [36] |

| Colony Formation | Decreased | Colony Formation Assay | Inhibition of long-term clonogenic survival | [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for HXR9 Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HXR9 Peptide | Active inhibitory peptide. Sequence: W-Y-P-W-M-K-K-H-H-(R)₉ | The conserved tryptophan (W) in the hexapeptide is essential for PBX binding. >90% purity (D-isomer) recommended [37]. |

| CXR9 Peptide | Negative control peptide. Sequence: W-Y-P-A-M-K-K-H-H-(R)₉ | Single amino acid change (W→A) ablates PBX binding. Crucial for controlling for non-specific effects [37] [36]. |

| Cell Penetrating Motif (R9) | Nine arginine residues facilitating cellular uptake. | Present in both HXR9 and CXR9. Can cause toxicity at high concentrations, necessitating proper controls [36]. |

| Annexin V-FITC / PI Kit | For detecting phosphatidylserine exposure and membrane integrity to quantify apoptosis. | Use EDTA-free trypsin during cell harvesting to prevent artifactual PI staining [36]. |

| CCK-8 Reagent | For measuring cell viability and proliferation. | More sensitive and safer than MTT. Incubate for 1-4 hours before reading absorbance at 450 nm [36]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Added to lysis buffers for Western Blot/Co-IP to prevent protein degradation. | IDPs and peptides are highly sensitive to proteolysis [39] [38]. |

| Siliconized Tubes | Low-retention microtubes. | Minimizes loss of peptide and proteins due to adsorption to plastic surfaces [38]. |

Molecular Mechanism Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core molecular mechanism of HXR9 action.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This guide addresses common challenges in studying enhancer-promoter (E-P) interactions, specifically within the context of optimizing temporal control for Hox gene expression perturbations.

FAQ 1: Why do my enhancer perturbations fail to produce the expected changes in target gene expression, especially at long-range distances?

- Problem: A manipulated enhancer does not affect the expected target promoter.

- Solution:

- Confirm Enhancer-Promoter Specificity: Many developmental enhancers (approximately 61%) bypass their immediate neighboring genes to interact with more distal promoters [40]. Use high-resolution Capture Hi-C in your specific cell type to validate the physical interaction between your enhancer and the intended promoter.

- Check for Bypassed Genes: Identify if any genes are located between your enhancer and its intended target. Promoters of these "skipped" genes are often inactive and marked by high CpG methylation (e.g., ~80% average methylation at TSSs in forebrain) [40]. Assay the DNA methylation status of intervening promoters to understand the regulatory landscape.

- Assess Protein Regulator Dependency: Long-range E-P interactions (>50 kb) are highly sensitive to the depletion of cohesin (e.g., RAD21) and mediator complex components (e.g., MED14) [41]. Verify the integrity of these complexes in your experimental system. Short-range interactions may be unaffected or even upregulated upon cohesin loss.

FAQ 2: How can I resolve inconsistent temporal gene activation when studying dynamic processes like Hox gene collinearity?

- Problem: Gene activation does not follow the precise spatiotemporal pattern required for proper development.

- Solution:

- Understand the Regulatory Mode: Recognize that the mode of E-P communication can change during development. In early specification phases (e.g., in Drosophila myogenic/neurogenic cells), E-P topologies are often permissive (pre-formed and uncoupled from activity), while later, during terminal differentiation, they become instructive (proximity is coupled with activation) [42]. Design your perturbations with the correct developmental stage in mind.

- Investigate the Biophysical Model: For Hox genes, consider the biophysical model, which posits that physical forces pull the cluster from a repressive chromosome territory to a transcription factory in a step-wise manner, driven by morphogen gradients [43]. Perturbations affecting nuclear architecture or force-generating molecules could disrupt this process.

- Profile Chromatin Accessibility: Temporal control is often mediated by hormone-induced transcription factors (e.g., E93 in Drosophila) that regulate chromatin accessibility. Profile open chromatin (e.g., with FAIRE-seq or ATAC-seq) across your time course to identify dynamically opening and closing enhancers [44].

FAQ 3: What could cause the loss of E-P interactions after a differentiation signal or cell state transition?

- Problem: Previously stable E-P interactions disappear as cells change state.

- Solution:

- Profile 3D Genome Reorganization: Major cell state transitions (e.g., pluripotency exit) involve dramatic 3D genome reorganization. In mouse ES cells transitioning to a formative state, inter-chromosomal contacts increase, and new multiway hubs form, reconfiguring E-P interactions [45]. Use single-cell Hi-C to determine if your E-P pair is being incorporated into a new chromatin hub.

- Monitor Key Regulators: The structural reorganization during state transitions can be regulated by enzymes like DNMT3A/B and TET1 [45]. Check the expression and activity of these regulators.

FAQ 4: My reporter assay shows activity, but I cannot detect the E-P loop with standard 3C methods. What might be wrong?

- Problem: A functional enhancer does not show a strong looping interaction in population-based assays.

- Solution:

- Consider Transient or Multiway Interactions: The interaction might be transient or occur within a multiway hub that is diluted in population averages [45]. Employ single-cell or high-resolution methods (e.g., Capture-C) to detect these complex, dynamic interactions.

- Verify Bait Efficiency: In capture-based methods, ensure your baits (oligos) are efficiently targeting the enhancer and promoter regions. Check the capture efficiency statistics from your sequencing data [42].

Table 1: Modes of Enhancer-Promoter Communication

| Mode | Description | Relationship to Activity | Developmental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructive | E-P proximity is established concurrently with gene activation. | Coupled | Terminal tissue differentiation [42] |

| Permissive | Pre-formed E-P loops exist before gene activation. | Uncoupled | Cell-fate specification [42] |

| Anticorrelated | E-P proximity decreases during activation. | Anti-correlated | Specific inducible contexts [42] |

Table 2: Protein Regulators and Their Distance-Dependent Effects on E-P Communication

| Regulator Class | Example Protein | Effect on Long-Range E-P Genes (>50 kb) | Effect on Short-Range E-P Genes (<10 kb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesin | RAD21 | Significant downregulation [41] | Upregulated or insensitive [41] |

| Mediator Complex | MED14 | Significant downregulation [41] | Largely insensitive [41] |

| Transcription Factors | LDB1 | Significant downregulation [41] | Less sensitive [41] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Capture-C for High-Resolution E-P Interaction Mapping

This protocol is used to generate high-resolution contact maps for hundreds of pre-characterized enhancers and promoters [42] [40].

- Nuclei Isolation and Fixation: Isolate nuclei from your tissue or sorted cell population of interest. Use crosslinking (e.g., with formaldehyde) to fix chromatin interactions.

- Chromatin Digestion and Proximity Ligation: Digest crosslinked chromatin with a 4-cutter restriction enzyme (e.g., DpnII). Perform proximity ligation to join crosslinked DNA fragments.

- Bait Capture (Hybridization): Design biotinylated RNA probes (e.g., using Agilent SureSelect) targeting your regions of interest (enhancers/promoters). Use these probes to capture the ligation products from the whole-genome library.

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Sequence the captured fragments. Process the data using a specialized pipeline like CHiCAGO to identify high-confidence, significant interactions [42].

Protocol 2: Validating E-P Loop Functionality with Enhancer Knock-Outs

This protocol validates the functional relevance of an identified E-P interaction [40].

- CRISPR/Cas9 Design: Design guide RNAs (gRNAs) to flank and excise the enhancer region of interest.

- Generation of Knock-Out Model: Inject gRNAs and Cas9 into mouse zygotes to generate founder lines, or create knock-outs in your cell model.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Molecular: Assess the expression of the putative target gene(s) via RNA-seq or qPCR. Confirm the loss of the E-P interaction using 3C-qPCR or Capture-C.

- Functional/Morphological: Analyze for developmental defects consistent with the loss of the target gene's function.

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Enhancer-Promoter Communication Workflow

Biophysical Model of Hox Collinearity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for E-P Interaction Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Capture-C / Hi-C | Maps genome-wide 3D chromatin interactions. | Identifying tissue-specific E-P loops [42] [40]. |

| FAIRE-seq / ATAC-seq | Identifies regions of open, accessible chromatin. | Profiling temporal changes in enhancer activity [44]. |

| RAD21 Degron Cell Line | Enables rapid, inducible degradation of the cohesin subunit RAD21. | Testing the dependency of long-range E-P interactions on cohesin [41]. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems | Allows for targeted activation (CRISPRa) or inhibition (CRISPRi) of enhancers. | Functionally validating enhancer activity and target genes [41]. |

| Biophysical Model Reagents | Targets for disrupting force generation (property N or P-molecules). | Experimentally testing the Hox collinearity model [43]. |

| Reporter Gene Constructs (e.g., GFP) | Visualizes the spatiotemporal activity pattern of an enhancer. | Testing enhancer function in transgenic models [46]. |

The precise temporal control of Hox gene expression is fundamental to embryonic development and axial patterning. Research has established that Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs), Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs), and Retinoic Acid (RA) serve as key morphogen signals that regulate the sequential activation of Hox genes in a collinear fashion. These signaling pathways function as biological switches that determine the anatomical identity of cells along the anterior-posterior axis. The integration of these signals occurs through complex regulatory networks involving chromatin modifications, dynamic enhancer-promoter interactions, and transcriptional cascades. Understanding how to experimentally manipulate these pathways with temporal precision provides researchers with powerful tools to investigate the fundamental mechanisms of developmental patterning and offers potential therapeutic approaches for congenital disorders.

Pathway Diagrams and Regulatory Logic

Core Signaling Pathways and Their Interactions

Experimental Workflow for Temporal Manipulation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Reagents for Temporal Control of Signaling Pathways

| Reagent Category | Specific Compounds | Concentration Range | Temporal Application | Primary Effect on Hox Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP Modulators | BMP4 (agonist) | 4-64 ng/mL [47] | Late phase (5' Hox genes) | Promotes proximal/posterior Hox genes (Hox10-13) [47] |

| Noggin (antagonist) | Varies by system | Early phase inhibition | Expands anterior Hox domains [48] | |

| FGF Modulators | FGF2/FGF4 (agonists) | Titration dependent [47] | Middle phase (central Hox genes) | Boosts endogenous Fgf genes; specifies middle Hox domains (Hox6-9) [47] |

| SU5402 (antagonist) | 25-100 µM [48] | Early phase inhibition | Impairs posterior Hox expression; affects differentiation speed [47] | |

| RA Modulators | Retinoic Acid (agonist) | 0.1-1 µM [49] | Early phase (3' Hox genes) | Directly regulates Hox1-5 via RAREs; anterior specification [3] |

| BMS493 (antagonist) | Varies by system | Late phase inhibition | Prevents anteriorization; permits posterior Hox expression | |

| Pathway Integrators | Chir99021 (Wnt agonist) | 1 µM [47] | Context-dependent | Synergizes with BMP/FGF for mesoderm patterning [47] |

| XAV939 (Wnt inhibitor) | Varies by system | Maintenance phase | Stabilizes anterior Hox domains |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Problems and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Signaling Pathway Experiments

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solution Approaches | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure of posterior Hox activation | Insufficient BMP signaling | Titrate BMP4 (8-64 ng/mL); check for endogenous BMP antagonists [47] | Monitor Hand1 expression; assess SMAD1/5 phosphorylation [47] |

| Insufficient anterior Hox specification | Excessive BMP or FGF signaling | Add BMP antagonists (Noggin); use SU5402 to inhibit FGF signaling [48] | Analyze Hox1-Hox5 expression via qPCR; check RA signaling activity [49] |

| Disrupted temporal collinearity | Improper timing of pathway modulation | Establish precise temporal application windows; use pulsatile treatment | Single-cell RNA-seq across time course; chromatin accessibility assays [50] |

| Lack of spatial restriction | Poor community effects or signaling boundaries | Implement micropatterned cultures; adjust cell density [47] | Spatial transcriptomics; in situ hybridization [29] |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Variable differentiation efficiency | Standardize starting cell population (e.g., EpiSC in FAX medium) [47] | Pre-check pluripotency markers; ensure consistent culture conditions |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is temporal application sequence critical for proper Hox gene activation?

A: Temporal sequence is essential because Hox genes exhibit collinearity - their activation follows a strict 3' to 5' order within clusters that corresponds to anterior-to-posterior patterning [49]. Research shows that successive Hox gene activation is associated with directional transitions in chromatin status [50]. Applying RA early mimics natural development where 3' Hox genes are activated first, while BMP later promotes 5' Hox expression [47] [49]. Disrupting this sequence produces conflicting signals that fail to establish proper axial identity.

Q: How can I confirm that my pathway modulators are working at the intended timepoints?

A: Implement rapid downstream signaling readouts 2-4 hours after treatment application. For BMP pathway, monitor phospho-SMAD1/5/8 levels via Western blot or immunostaining [51]. For FGF pathway, assess phospho-ERK levels [52]. For RA pathway, examine direct targets like RARB or Cyp26a1 expression [3]. These rapid responses confirm pathway engagement before assessing later Hox expression changes.

Q: What experimental system best recapitulates endogenous Hox temporal regulation?