Signaling Dynamics in Gastrulation: Integrating Mechanics, Pathways, and Models for Developmental Biology and Drug Discovery

Gastrulation is a pivotal developmental stage where a uniform cell sheet transforms into the structured embryonic germ layers, a process long thought to be directed solely by biochemical signals.

Signaling Dynamics in Gastrulation: Integrating Mechanics, Pathways, and Models for Developmental Biology and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Gastrulation is a pivotal developmental stage where a uniform cell sheet transforms into the structured embryonic germ layers, a process long thought to be directed solely by biochemical signals. This article synthesizes recent breakthroughs revealing that mechanical forces and the precise temporal dynamics of signaling pathways are equally critical. We explore foundational principles, highlighting the interplay between pathways like Nodal, BMP, and PCP. We detail cutting-edge methodologies, from Brillouin microscopy mapping mechanical properties in real-time to optogenetic tools and deep learning models like EmbryoNet for high-throughput phenotyping. The content addresses challenges in modeling human development and validates findings across model organisms. This integrated view of signaling dynamics offers profound implications for understanding congenital disorders and advancing regenerative medicine strategies.

Core Principles: How Signaling Dynamics and Mechanical Forces Orchestrate Germ Layer Formation

Gastrulation represents a pivotal developmental event wherein a uniform sheet of embryonic cells undergoes large-scale morphogenetic reorganization to form the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—and establish the fundamental body plan. This process is governed by an intricate interplay between biochemical signaling pathways and physical mechanical forces. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to delineate the signaling dynamics, including the roles of BMP, WNT, and Nodal pathways, and the emerging understanding of how tissue geometry, tension, and mechanical competence integrate with molecular cues to direct gastrulation. We provide a detailed analysis of experimental models, quantitative data, and methodologies that are advancing our understanding of these fundamental developmental mechanisms, with implications for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

Gastrulation is the critical developmental process during which a single-layered embryo transforms into a multilayered structure called the gastrula, possessing the three germ layers that will give rise to all fetal tissues [1]. In humans, this process commences around week three of development and is marked by the appearance of the primitive streak, a groove at the caudal end of the epiblast layer that establishes the cranial-caudal axis [1]. The initiation and progression of gastrulation are directed by a conserved set of signaling pathways, including TGF-β (encompassing BMP and Nodal), WNT, and others, which create patterning gradients across the embryo [1].

Historically, research has focused on these biochemical signals. However, emerging evidence underscores that mechanical forces are equally critical; gastrulation proceeds only when cells are both chemically prepared and physically primed [2]. This whitepaper explores the dynamics of these signals and forces, providing a technical guide for researchers dissecting the fundamental mechanisms of human development.

Core Signaling Pathways and Their Dynamics

The coordination of gastrulation relies on the precise spatiotemporal activity of several key signaling pathways. The table below summarizes the primary functions and known inhibitors of these pathways.

Table 1: Core Signaling Pathways in Gastrulation

| Signaling Pathway | Primary Role in Gastrulation | Key Inhibitors/Regulators |

|---|---|---|

| BMP | Initiates symmetry breaking; specifies extraembryonic mesoderm (ExM) and other cell fates [2] [3]. | BMP inhibitors (e.g., from hypoblast) help confine activity [1]. |

| WNT | Induces primitive streak formation; regulates convergence and extension movements [1] [4]. | Dkk-1, Crescent [1]. |

| Nodal | Promotes mesendodermal fate; works with WNT to induce streak formation [1] [3]. | Antagonists released by the hypoblast [1]. |

| TGF-β (Vg1) | Induces primitive streak formation; acts on Nodal to continue chemical cascade [1]. | Not specified in search results. |

| Non-canonical WNT (PCP) | Regulates directed cell migration and polarity during convergent extension [4]. | Not specified in search results. |

The Interplay of BMP, WNT, and Nodal Signaling

The formation of the primitive streak is initiated by a system of signaling pathways that work to both positively and negatively regulate downstream expression. The combination of TGF-β, WNT, Nodal, and BMPs is instrumental in this process [1]. WNT and TGF-β signaling appear to be primary inducers, with factors like Vg1 (a TGF-β member) shown to induce streak formation, partly by acting on Nodal [1]. Furthermore, WNT activation is crucial, as evidenced by the fact that Wnt antagonists like Dkk-1 and Crescent can prevent streak formation [1]. BMP signaling also plays a regulatory role, with its concentration typically lower near the streak and higher in the surrounding embryo, creating a gradient that guides cell differentiation [1].

Recent research using human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) confirms that the modulation of BMP, WNT, and Nodal signaling can rapidly (within 4-5 days) and efficiently (≈90%) induce the differentiation of both naive and primed hESCs into extraembryonic mesoderm-like cells (ExMs) [3]. This specification predominantly proceeds through intermediates exhibiting a primitive streak-like gene expression pattern, delineating the regulatory roles of WNT and Nodal signaling [3].

Signaling in Model Organisms

Studies in model organisms like Drosophila and zebrafish have been instrumental in elucidating the conserved mechanisms of gastrulation signaling.

- Drosophila: Gastrulation is triggered by a gradient of the morphogen Spätzle, which peaks at the ventral midline and leads to the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor Dorsal [5]. Different thresholds of nuclear Dorsal concentration activate distinct target genes; high concentrations activate mesoderm-specific genes like twist and snail [5]. The connection between gene expression and morphogenesis is exemplified by mesoderm invagination, which is driven by apical constriction activated by secreted ligands and GPCR signaling [5].

- Zebrafish: Gastrulation involves large-scale morphogenetic processes like epiboly, internalization, and convergent extension [4]. The non-canonical Wnt/Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) pathway is a major regulator of these polarized cell movements, controlling processes like directed cell migration and the narrowing/extension of the body axis [4]. This pathway, which includes proteins like Frizzled, Dishevelled, and Prickle, regulates the cytoskeleton to orchestrate collective cell behavior [4].

The Role of Mechanical Forces in Gastrulation

A paradigm shift in gastrulation research is the recognition that biochemical signals alone are insufficient; physical forces are a necessary and integral component.

Mechanical Competence and Symmetry Breaking

Research using optogenetic tools to activate BMP4 in human embryonic stem cells revealed that chemical cues alone could not fully initiate gastrulation. In unconfined, low-tension environments, BMP4 activation gave rise to extra-embryonic cell types but failed to generate the mesoderm and endoderm layers that form the body's organs [2]. However, when the same BMP4 signal was activated in confined cell colonies or in tension-inducing hydrogels, the missing germ layers began to form [2]. This demonstrates that mechanical tension is a prerequisite for symmetry breaking and germ layer formation.

Further experiments revealed the molecular mechanism behind this phenomenon: the mechanosensory protein YAP1 acts as a molecular brake on gastrulation. Nuclear YAP1 prevents transformation until mechanical tension releases this brake, thereby fine-tuning the downstream biochemical signaling pathways mediated by WNT and Nodal [2]. This interdependence defines a state of mechanical competence that cells must achieve to progress through developmental milestones [2].

Cellular Mechanisms of Force Generation

At the cellular level, force generation is driven by the actomyosin cytoskeleton.

- Apical Constriction: In Drosophila, mesoderm invagination is driven by apical constriction, where cells contract their apical surfaces using actin and nonmuscle myosin 2 (myosin 2) [5]. This changes cell shape from columnar to wedge-shaped, promoting inward tissue curvature [5].

- Actomyosin Networks: The assembly of multicellular actomyosin networks allows force to propagate across hundreds of cells, enabling coordinated tissue sculpting. Such networks are conserved and also operate during gastrulation and neural tube closure in vertebrates [5].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Advances in stem cell biology and bioengineering have provided powerful models to study human gastrulation, circumventing the ethical and technical challenges of working with human embryos.

hESC-Based Models of Extraembryonic Mesoderm Specification

An efficient culture system has been established to differentiate hESCs into expandable ExM-like cells (ExMs). The protocol below details the methodology.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for ExM Specification from hESCs

| Step | Parameter | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Preparation | Cell Line | AIC-N human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) [3]. |

| Surface Coating | Matrigel-coated dishes [3]. | |

| 2. Culture Medium | Base Medium | FH-N2B27 (modified N2B27 medium containing FGF4 and heparin) [3]. |

| Key Additives | CHIR99021 (CHIR, a GSK3 inhibitor) and BMP4 [3]. | |

| 3. Process | Differentiation Duration | 4 days [3]. |

| Efficiency | ~90% conversion to ExM-like cells [3]. | |

| 4. Validation | Markers (Upregulated) | GATA6, SNAIL, VIM, KDR, FLT1, HAND1, PDGFRA [3]. |

| Markers (Downregulated) | POU5F1 (OCT4), NANOG, SOX2 [3]. | |

| Analysis Methods | Immunofluorescence, Flow Cytometry, Bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq [3]. |

Optogenetic Control and Synthetic Embryo Models

To dissect the interplay between biochemical signals and mechanical forces, an optogenetic tool was developed to activate developmental genes with spatiotemporal precision [2].

- Protocol: Human embryonic stem cells are engineered to express a light-sensitive switch that permanently turns on BMP4 upon exposure to a specific wavelength of light [2].

- Application: Researchers can shine light on specific regions of confined cell colonies to test how tissue geometry and mechanical stress influence developmental outcomes. This system revealed that gastrulation requires mechanical tension in concert with BMP4 signaling [2].

- Mathematical Modeling: A "digital twin" of a developing embryo, built using actual measurements of mechanical tension, can simulate how biochemical signals and physical forces interact to self-organize. These simulations closely match experimental observations [2].

Engineered Models of Peri-Gastrulation

The field has seen a rapid expansion of engineered models that replicate specific stages of development:

- Pre-gastrulation models (e.g., Blastoids): Replicate blastocyst formation and implantation [6].

- Gastrulation models (e.g., 2D micropatterned systems, 3D gastruloids): Provide insights into germ layer formation and tissue organization [6].

- Post-gastrulation models (e.g., Somitoids): Mimic early somitogenesis and axial elongation [6].

These systems are enhanced by engineering technologies like micropatterned substrates, microfluidic systems, and synthetic biology tools, which allow for precise control over the cellular microenvironment [6].

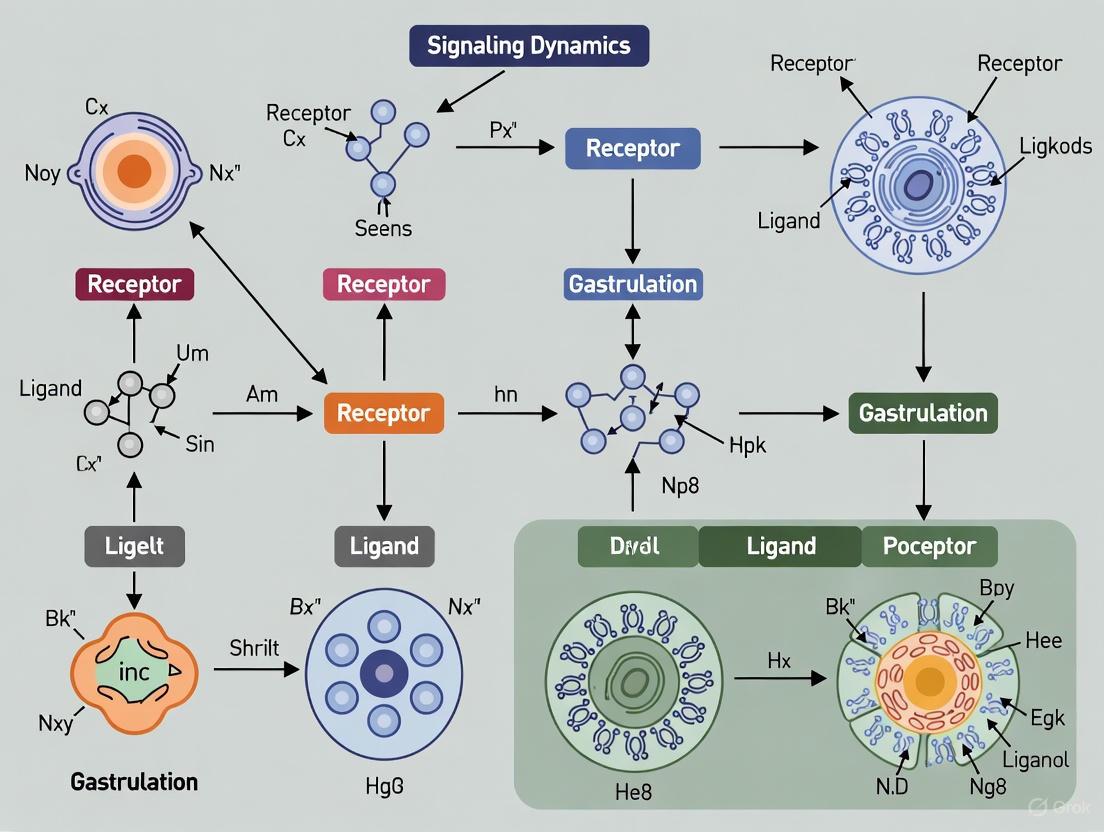

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

BMP/WNT/Nodal Signaling in Gastrulation

Diagram Title: Signaling and Mechanical Control of Gastrulation

Experimental Workflow for ExM Specification

Diagram Title: Workflow for Directing ExM from hPSCs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles key reagents and their applications for investigating signaling dynamics in gastrulation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gastrulation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use in Gastrulation Research |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3 inhibitor; activates WNT signaling. | Used with BMP4 to efficiently differentiate hESCs into ExM cells [3]. |

| BMP4 | Morphogen; key signaling protein. | Induces symmetry breaking and specifies cell fates like ExM [3] [2]. |

| FGF4 & Heparin | Growth factor and co-factor; supports cell growth. | Component of the base FH-N2B27 medium for ExM differentiation [3]. |

| Optogenetic BMP4 Switch | Light-activated genetic switch for BMP4. | Precisely controls timing and location of BMP4 signaling to study force interplay [2]. |

| Micropatterned Substrates | Engineered surfaces to control cell geometry. | Controls colony shape and internal mechanical stresses in 2D gastruloid models [2] [6]. |

| Tension-Inducing Hydrogels | Synthetic extracellular matrices. | Provides mechanical confinement to study the role of tension in germ layer specification [2]. |

| AIC-N hESCs | Naive human embryonic stem cell line. | Cell line used for efficient ExM differentiation studies [3]. |

| 2,2,2',4'-Tetrachloroacetophenone | 2,2,2',4'-Tetrachloroacetophenone | High Purity | High-purity 2,2,2',4'-Tetrachloroacetophenone for research. A key synthon & photoinitiator. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-hexan-3-yloxycarbonylbenzoic acid | 2-hexan-3-yloxycarbonylbenzoic Acid | High-Purity Reagent | 2-hexan-3-yloxycarbonylbenzoic acid is a key reagent for organic synthesis and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The process of gastrulation is no longer viewed as a simple cascade of biochemical signals but as an integrated system where biochemical gradients and physical forces are inextricably linked. Core signaling pathways—BMP, WNT, and Nodal—provide the instructional code, but the physical context of the cells, their mechanical tension, and tissue geometry provide the necessary permissive conditions for execution. The emergence of sophisticated models, from hESC differentiation systems to optogenetically controlled synthetic embryos, is providing unprecedented insight into these dynamics. This deeper understanding not only illuminates the fundamental principles of human development but also paves the way for advances in regenerative medicine by providing controlled methods to specify cell fates and engineer tissues.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the Nodal, BMP/WNT, and Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) signaling pathways, focusing on their integrated roles during gastrulation. These evolutionarily conserved pathways form a critical signaling network that governs embryonic patterning, germ layer specification, and tissue morphogenesis. We examine the molecular mechanisms, pathway crosstalk, and dynamic signaling behaviors that coordinate these processes, with particular emphasis on quantitative signaling parameters and experimental approaches relevant to in vitro model systems. Additionally, we present a curated toolkit of research reagents and visualization resources to facilitate further investigation into the role of signaling dynamics in gastrulation research.

Gastrulation represents a pivotal phase in embryonic development where a homogeneous population of pluripotent epiblast cells self-organizes into the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—that form the entire embryo. Decades of research in model organisms and human stem cell models have revealed that a precisely orchestrated signaling cascade involving Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), WNT, and NODAL pathways is indispensable for initiating gastrulation [7]. These pathways activate specific genetic programs that dictate cellular fate decisions through precise spatiotemporal dynamics rather than stable signaling gradients [7]. The planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway, while often associated with later morphogenetic events, also contributes to the coordinated cellular movements and polarity establishment during this critical developmental window. Understanding the integrated dynamics of these pathways provides crucial insights into the fundamental principles of embryonic patterning and offers valuable paradigms for directed differentiation of stem cells for regenerative medicine applications.

Pathway Mechanisms and Molecular Components

Nodal Signaling Pathway

The Nodal signaling pathway is a specialized branch of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily that plays central roles in early embryonic patterning, including mesoderm specification, anterior-posterior axis patterning, and left-right axis determination [8]. Nodal signaling utilizes core TGF-β receptors and Smad-dependent signaling components but possesses several distinctive characteristics. The pathway requires EGF-CFC family co-receptors (Cripto and Cryptic) for effective signaling complex formation [8]. Following ligand binding to type I and type II receptor heterodimers, phosphorylated R-Smads form trimeric complexes with Smad4 that translocate to the nucleus. These complexes specifically cooperate with FoxH1 or Mixer transcription factors to regulate spatial and temporal expression of Nodal-dependent target genes [8]. The pathway is subject to unique negative regulation by Lefty proteins, which inhibit Nodal signaling through direct interaction with both the ligand and EGF-CFC co-receptors [8].

BMP and WNT Signaling Pathways

The BMP and WNT pathways function as interconnected regulators of cell fate decisions during gastrulation and organogenesis. BMP signaling, another TGF-β family pathway, exhibits concentration-dependent effects on cell fate specification, with lower levels promoting intermediate mesoderm formation and higher levels favoring lateral plate mesoderm development [9]. The canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway regulates target gene expression through a sophisticated protein degradation mechanism. In the absence of WNT ligands, β-catenin is phosphorylated by a multiprotein destruction complex comprising Axin, APC, GSK3β, and CK1α, marking it for proteasomal degradation [10]. WNT ligand binding to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors disrupts this destruction complex, allowing β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation where it associates with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes [10]. Non-canonical WNT pathways, including the Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca²⺠pathways, function independently of β-catenin to modulate cell polarity, migration, and calcium signaling [10].

Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) Signaling

The Planar Cell Polarity pathway coordinates the polarization of cells within the epithelial plane, enabling uniform orientation of cellular structures and directional movements. Core PCP components include Frizzled (Fz), Flamingo (Fmi), Van Gogh (Vang), Prickle (Pk), and Dishevelled (Dsh) [11]. These proteins undergo asymmetric subcellular localization, forming distinct molecular complexes on opposite sides of cells [12]. The system employs intercellular feedback loops where Fmi homodimers bridge opposing complexes in adjacent cells, communicating polarity information across the tissue [12]. Recent research demonstrates that PCP signaling can polarize cells autonomously without intercellular communication, though tissue-wide coordination is lost under these conditions [12]. This pathway ensures properly oriented cell divisions, asymmetric cellular morphology, and directional cell migration—processes essential for neural tube closure, inner ear hair cell orientation, and other morphogenetic events [11].

Table 1: Core Components of Key Signaling Pathways in Gastrulation

| Pathway | Key Components | Regulators | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodal | Nodal, Type I/II TGF-β receptors, Smad2/3, Smad4, FoxH1 | Cripto, Cryptic, Lefty | Mesoderm specification, anterior-posterior patterning, left-right axis determination |

| BMP | BMP ligands, BMP receptors, Smad1/5/8, Smad4 | Noggin, Chordin | Germ layer patterning, intermediate mesoderm specification at low levels |

| Canonical WNT | Wnt ligands, Frizzled, LRP5/6, Dvl, β-catenin, GSK3β, APC, Axin, TCF/LEF | DKK1, IWP2 | Primitive streak formation, mesoderm induction, posterior patterning |

| Non-canonical WNT | Wnt ligands, Frizzled, ROR2, Dvl, RAC, RHOA, JNK, PLC | - | Cell polarity, migration, calcium signaling |

| PCP | Frizzled, Flamingo, Van Gogh, Prickle, Dishevelled, Diego | Ft, Ds, Fj | Tissue-scale cell alignment, directional cell movements, oriented cell divisions |

Quantitative Signaling Dynamics in Gastrulation

Signaling Dynamics and Thresholds

Quantitative analysis of signaling pathway dynamics reveals distinct temporal behaviors during gastrulation. BMP signaling initiates first, becoming restricted to colony edges within 12 hours in micropatterned human gastruloid systems [7]. This initial BMP activation triggers sequential waves of WNT and NODAL signaling activity that propagate toward the colony center at constant rates [7]. Mathematical modeling of these dynamics suggests they are inconsistent with reaction-diffusion-based Turing systems, indicating the absence of stable WNT/NODAL signaling gradients [7]. Instead, the final signaling state is homogeneous, with spatial differences arising primarily from boundary effects. The duration rather than the concentration of WNT and NODAL signaling appears critical for mesoderm differentiation, while BMP signaling duration controls extra-embryonic cell differentiation [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Signaling Pathway Manipulation in Stem Cell Differentiation

| Signaling Pathway | Modulator | Concentration/Type | Effect on Differentiation | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WNT | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) | 3-8 μM | Induces TBXT+/MIXL1+ mesoderm progenitors | Intermediate mesoderm differentiation [9] |

| BMP | BMP4 | 4-100 ng/mL | Low concentrations (4 ng/mL) with WNT promote OSR1+/GATA3+/PAX2+ intermediate mesoderm | Optimized IM differentiation protocol [9] |

| Nodal/Activin | Activin A | 100 ng/mL | Induces primitive streak and mesendoderm | Conventional differentiation protocol [9] |

| Nodal Inhibition | SB-431542 (ALK4/5/7 inhibitor) | Not specified | Blocks Activin/Nodal/TGFβ signaling | Primitive streak induction studies [13] |

| WNT Inhibition | DKK1 | Not specified | Inhibits canonical WNT signaling | Primitive streak induction studies [13] |

Pathway Crosstalk and Combinatorial Signaling

Extensive crosstalk occurs between the Nodal, BMP, and WNT pathways, forming an integrated signaling network that collectively orchestrates cell fate decisions. Studies in embryonic stem cells demonstrate that Activin/Nodal and WNT signaling are required for primitive streak induction, while BMP signaling exerts a posteriorizing effect on this population [13]. All three pathways regulate the induction of Flk1+ mesoderm, but their requirements shift during subsequent specification events [13]. The combinatorial interpretation of BMP and WNT signaling specifically controls the decision between primitive streak and extraembryonic fates [14]. This interplay extends to PCP signaling, which intersects with WNT pathways through shared components like Frizzled and Dishevelled, creating a complex regulatory network that coordinates tissue patterning with cellular polarization [10] [11].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Gastruloid Models and Micropatterned Systems

Micropatterned in vitro models of human gastrulation provide a robust platform for quantifying signaling dynamics and their relationship to cell fate patterning. In these systems, human pluripotent stem cells are confined to circular micropatterns and treated with BMP4 to initiate self-organized differentiation [7]. This approach generates radial patterns of germ layer organization: an outer ring of CDX2+ extra-embryonic cells, followed by concentric rings of SOX17+ endoderm, BRACHYURY+ mesoderm, and a central region of NANOG+/SOX2+ pluripotent cells [7]. The reproducibility and geometric uniformity of these systems enable precise quantification of signaling dynamics using live-cell imaging of pathway reporters, mathematical modeling, and systematic perturbation studies. This experimental paradigm has demonstrated that self-organized patterning can occur in the absence of stable signaling gradients, highlighting the importance of dynamic signal interpretation in cell fate decisions [7].

Directed Differentiation Protocols

Optimized differentiation protocols for generating specific progenitor populations provide valuable insights into pathway requirements at distinct developmental stages. For intermediate mesoderm differentiation, a highly efficient two-step protocol has been established: treatment of human pluripotent stem cells with 3 μM CHIR99021 for 48 hours induces TBXT+/MIXL1+ mesoderm progenitors, followed by treatment with 3 μM CHIR99021 and 4 ng/mL BMP4 for an additional 48 hours to generate OSR1+/GATA3+/PAX2+ intermediate mesoderm cells [9]. This protocol emphasizes the importance of suppressing high Nodal signaling during the mesoderm step and employing low BMP4 concentrations for specific IM induction, contrasting with conventional approaches that use higher BMP4 concentrations (100 ng/mL) [9]. Stage-specific pathway requirements have also been delineated for hematopoietic specification, where WNT signaling is essential for commitment to the primitive erythroid lineage but not required for definitive hematopoietic lineages [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Gastrulation Signaling Pathways

| Reagent | Type | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Small molecule inhibitor | GSK3β inhibitor that activates WNT signaling | Induces mesoderm progenitors at 3-8 μM [9] |

| BMP4 | Recombinant protein | BMP pathway ligand; patterns mesoderm | Promotes IM fate at low concentrations (4 ng/mL) [9] |

| Activin A | Recombinant protein | Nodal pathway surrogate; induces mesendoderm | Primitive streak induction at 100 ng/mL [9] |

| IWP2 | Small molecule inhibitor | Inhibits WNT ligand secretion | Blocks WNT signaling in perturbation studies [7] |

| SB-431542 | Small molecule inhibitor | Inhibits Activin/Nodal/TGFβ signaling (ALK4/5/7 inhibitor) | Blocks Nodal signaling in primitive streak studies [13] |

| DKK1 | Recombinant protein | Canonical WNT signaling inhibitor | Blocks WNT signaling in primitive streak induction [13] |

| BMPR-Fc fusion proteins | Recombinant receptor | Sequesters BMP ligands to inhibit signaling | BMP pathway inhibition studies [13] |

| NODAL −/− cells | Genetically modified cells | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of NODAL | Studying Nodal-independent differentiation [7] |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Nodal Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: Nodal Signaling Mechanism

BMP/WNT/PCP Signaling Network

Diagram Title: BMP-WNT-PCP Signaling Cascade

Planar Cell Polarity Mechanism

Diagram Title: PCP Asymmetric Complex Formation

Gastruloid Differentiation Protocol

Diagram Title: Intermediate Mesoderm Differentiation Workflow

The Nodal, BMP/WNT, and PCP signaling pathways constitute an integrated regulatory network that coordinates cell fate specification and tissue patterning during gastrulation through dynamic signaling behaviors rather than static concentration gradients. The quantitative parameters, experimental models, and research reagents outlined in this technical guide provide a foundation for investigating the sophisticated signaling dynamics that govern embryonic development. Future research directions include elucidating the molecular mechanisms of pathway crosstalk at higher resolution, developing more sophisticated mathematical models that predict signaling outcomes across diverse cellular contexts, and applying these insights to improve the efficiency and fidelity of stem cell differentiation for regenerative medicine applications. The continued integration of experimental and computational approaches will be essential for unraveling the complex signaling dynamics that orchestrate gastrulation and embryonic patterning.

Gastrulation is a fundamental milestone in early embryogenesis, responsible for transforming a simple sheet of cells into a complex, multi-layered structure with defined body axes. While the genetic and biochemical signals governing this process have been extensively studied, the crucial role of mechanical forces has only recently been fully appreciated. The emerging paradigm in developmental biology recognizes that mechanical forces and tissue mechanics are not merely passive outcomes but active regulators that coordinate cell behaviors across thousands of cells to drive robust and reproducible morphogenesis [15]. This mechanobiological perspective reveals that gastrulation represents an intricate dance between biochemical signaling and physical forces, where mechanochemical feedback loops ensure precise spatial and temporal coordination of cell fate specification and tissue remodeling [15] [16].

The framework of gastrulation must account for how short-range and long-range signaling integrates cell behaviors at the tissue and organism scale. Mechanical stresses generated by cellular activities create local and global feedback, coordinating cell behaviors through mechanosensitive signaling pathways [15]. Within this context, the interplay between tissue mechanics and classic morphogen signaling pathways such as BMP4, WNT, and Nodal creates a sophisticated regulatory system that guides symmetry breaking and germ layer formation [2] [16]. Understanding these mechanochemical principles provides not only fundamental biological insights but also practical applications for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

Core Mechanical Processes Driving Gastrulation

Key Cell Behaviors and Their Mechanical Basis

Gastrulation is driven by active forces arising from energy-consuming molecular motor activity and filament polymerization. These molecular-scale activities manifest in specific cell behaviors that collectively drive large-scale tissue transformations [15].

Table 1: Mechanical Cell Behaviors in Gastrulation

| Cell Behavior | Mechanical Function | Molecular Mechanisms | Representative Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercalation | Tissue elongation through convergent extension; generates tissue flows | Junctional actin-myosin cables; super-cellular myosin structures | Chick epiblast; Drosophila gastrulation |

| Internalization/EMT | Cell ingression through primitive streak; tissue internalization | Myosin II-driven apical constriction; complete EMT | Amniote mesendoderm precursors; Drosophila ventral furrow |

| Cell Division | Stress relief; tissue fluidity; oriented divisions relieve anisotropic stress | Division orientation along convergence axis | Avian embryos; frog and fish models |

| Apical Constriction | Tissue folding and invagination | Medial-apical actomyosin accumulation | Drosophila ventral furrow formation |

Intercalation and Convergent Extension

Intercalation involves neighboring cells exchanging positions, driving tissue elongation through a process called convergent extension [15]. In chick embryos, epithelial epiblast cells intercalate by shortening and remodeling cell-cell junctions through junctional actin-myosin cables [15]. The mechanical signature of this process includes the formation of super-cellular myosin cables spanning 2-8 cell junctions that orient perpendicular to the elongating streak, creating aligned junctional contractions [15]. When myosin phosphorylation is inhibited, these intercalation-associated tissue flows and streak formation are blocked, demonstrating the essential mechanical nature of this process [15].

Internalization and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

Internalization processes allow mesoderm and endoderm precursors to move from the surface to the interior of the developing embryo. In amniotes, this involves a complete epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), where cells individually ingress through the primitive streak [15]. The mechanical driver of this process is myosin II-driven apical constriction, where apical cell surface areas shrink before ingression, eventually leading to full EMT and migration beneath the epiblast [15]. Similar processes occur in Drosophila gastrulation, where ventral cells accumulate medial-apical actomyosin, causing apical constriction, tissue folding, and invagination of the mesoderm [17].

Material Properties and Their Dynamics

The material properties of embryonic tissues play a crucial role in gastrulation, undergoing dynamic changes that facilitate specific morphogenetic events. Recent advances in Brillouin microscopy have enabled the characterization and spatial mapping of the dynamics of cell material properties during Drosophila gastrulation in three dimensions and with high temporal resolution [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Measurements of Material Properties During Gastrulation

| Measurement Parameter | Technical Approach | Key Findings | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Modulus | Line-scan Brillouin microscopy (LSBM) | Transient increase in Brillouin shift within sub-apical compartment of mesodermal cells during ventral furrow formation | Identifies rapid, spatially varying changes in material properties correlated with cell fate |

| Brillouin Shift Dynamics | GHz-frequency mechanical probing | Differential dynamics between mesodermal and ectodermal cells; peaks at initiation of invagination | Reveals fate-specific mechanical signatures; suggests microtubule involvement |

| Microtubule Contribution | Colcemid disruption experiments | Reduced Brillouin shift during ventral furrow formation after microtubule disruption | Identifies microtubules as potential mechano-effectors |

These studies reveal that blastoderm cells undergo rapid and spatially varying changes in their material properties that differ according to cell fate and behavior [17]. Specifically, mesodermal cells display a transient increase in Brillouin shift (a proxy for longitudinal modulus) within their sub-apical compartment during ventral furrow formation, coinciding with the reorganization of sub-apical microtubules [17]. This mechanical transition is functionally important, as physical models confirm that a dynamic sub-apical increase in longitudinal modulus is essential for proper fold formation [17].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Optogenetic Control of Morphogen Signaling

The recently developed optogenetic tools for controlling morphogen signaling represent a breakthrough in dissecting the interplay between biochemical and mechanical signals. This approach enables precise spatial and temporal activation of developmental genes, allowing researchers to test how tissue geometry and mechanical stress influence developmental outcomes [2] [16].

Experimental Protocol: Light-Inducible BMP4 Signaling in hESCs

Cell Line Engineering: Insert the human BMP4 coding sequence downstream of a loxP-flanked stop cassette in a piggyBac vector, enabling controlled gene expression via light-induced loxP recombination [16].

Light Sensitivity Induction: Treat cells with DOX (doxycycline) to confer light sensitivity by inducing the expression of the Cre recombinase fused to the light-inducible Cry2/CIB1 system [16].

Spatiotemporal Activation: Expose cells to specific wavelengths of blue light (450-490 nm) to activate BMP4 signaling in precise patterns and locations [16].

Mechanical Context Manipulation: Apply the optogenetic stimulation in different mechanical environments:

- Low-tension environments: Unconfined cell cultures

- High-tension environments: Cells confined on micropatterns or embedded in tension-inducing hydrogels [2]

Outcome Assessment: Analyze the resulting patterns of cell differentiation, specifically the emergence of mesoderm and endoderm lineages, which require both BMP4 signaling and mechanical tension [2].

This methodology revealed that BMP4 signaling alone is insufficient to drive complete gastrulation - mechanical tension is equally essential. The combination of optogenetic control with mechanical manipulation demonstrated that YAP1 nuclear localization acts as a mechanical sensor, fine-tuning downstream biochemical signaling pathways mediated by WNT and Nodal [2].

Brillouin Microscopy for Material Property Mapping

Brillouin microscopy provides a non-invasive method for measuring material properties in living embryonic tissues with high spatial and temporal resolution. This technique exploits the inelastic interaction between light and biological matter, where the energy shift of scattered photons (Brillouin shift) correlates with the material's longitudinal modulus [17].

Experimental Protocol: Line-Scan Brillouin Microscopy (LSBM) for Gastrulation Studies

Sample Preparation: Mount live Drosophila embryos expressing appropriate fluorescent markers for cell fate identification in appropriate imaging chambers [17].

Instrument Setup: Configure the line-scan Brillouin microscope with:

- Laser source at 532 nm wavelength

- Scanning system for line illumination

- Tandem Fabry-Pérot interferometer for spectral analysis

- CCD camera for signal detection [17]

Data Acquisition:

- Perform sequential line scans across the region of interest

- Acquire data at multiple z-planes to generate 3D maps

- Maintain time intervals of 2-5 minutes between full volume acquisitions to capture dynamics [17]

Brillouin Shift Calculation:

- Process raw spectra to extract Brillouin shift values

- Convert shift values to longitudinal modulus using appropriate calibration (requires refractive index and mass density measurements) [17]

Spatiotemporal Analysis:

- Register Brillouin maps with fluorescence images to correlate mechanical properties with cell fate

- Track temporal evolution of mechanical properties in specific cell populations (mesodermal vs. ectodermal) [17]

Perturbation Experiments:

- Apply cytoskeletal drugs (e.g., Colcemid for microtubule disruption)

- Compare Brillouin shift dynamics in control vs. perturbed conditions [17]

This approach has revealed that mesodermal cells undergo a transient increase in longitudinal modulus during ventral furrow formation, while ectodermal cells display different mechanical dynamics, demonstrating fate-specific mechanical signatures [17].

Integrated Mechanochemical Signaling Pathways

The coordination of gastrulation emerges from the sophisticated interplay between mechanical forces and biochemical signaling pathways. Research across model systems has revealed conserved principles of mechanochemical integration that ensure robust patterning and morphogenesis.

The diagram above illustrates the core mechanochemical signaling network governing gastrulation. Mechanical forces, including tissue tension and geometric confinement, activate the YAP/TAZ mechanosensory system, which enables and fine-tunes the response to morphogen signaling including BMP4, WNT, and Nodal [2] [16]. These pathways collectively regulate cell fate specification, driving behaviors such as intercalation and EMT that generate further mechanical forces, creating a reinforcing feedback loop that ensures robust pattern formation [15] [2] [16].

This mechanochemical integration operates across multiple scales, from molecular mechanisms within individual cells to tissue-scale force generation and patterning. The presence of mechanical competence - where cells must be physically primed as well as chemically prepared - adds a crucial layer of regulation that ensures gastrulation proceeds with proper timing and spatial coordination [2].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mechanobiology Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optogenetic Systems | Light-inducible BMP4; Cry2/CIB1-Cre system | Spatiotemporal control of gene expression; tests biochemical-mechanical interplay | Human embryonic stem cells; synthetic embryo models [2] [16] |

| Mechanical Manipulation | Micropatterned substrates; tunable hydrogels; confinement devices | Controls tissue geometry and mechanical stress; tests force-response relationships | 2D gastruloids; embryonic explants [2] [16] |

| Live Imaging Reporters | Actin markers (Utrophin-GFP); Myosin reporters (Myosin-II-RLC-GFP); YAP localization biosensors | Visualizes cytoskeletal dynamics and mechanosensitive protein localization | Drosophila, chick, mouse embryos; live imaging [15] [17] |

| Cytoskeletal Drugs | Colcemid (microtubule disruption); Blebbistatin (myosin inhibition); Latrunculin (actin disruption) | Tests specific cytoskeletal contributions to mechanical properties | Drosophila embryos; tissue explants [17] |

| Mechanosensory Inhibitors | YAP/TAZ pathway inhibitors; ROCK inhibitors | Disrupts mechanotransduction pathways; tests mechanical signaling necessity | Human pluripotent stem cell models [2] [16] |

| Antibodies for Mechanobiology | Phospho-SMAD1/5; BRA/T; GATA6; SOX17; Phospho-myosin | Detects activation of biochemical and mechanical signaling pathways | Immunostaining across model systems [16] |

| Tetrabutylammonium diphenylphosphinate | Tetrabutylammonium diphenylphosphinate, CAS:208337-00-2, MF:C28H46NO2P, MW:459.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Diisopropyl chloromalonate | Diisopropyl Chloromalonate | High Purity | RUO Supplier | Diisopropyl chloromalonate: A versatile chloromalonate ester for organic synthesis & peptide mimicry. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

This toolkit enables researchers to probe both the generation and sensing of mechanical forces, providing comprehensive approaches to dissect the mechanobiology of gastrulation. The combination of optogenetic control with mechanical manipulation and advanced imaging represents particularly powerful emerging methodology [2] [16] [17].

The mechanobiology perspective reveals gastrulation as a process orchestrated by the intimate interplay between physical forces and biochemical signals. Mechanical competence - where tissues must achieve specific physical states to respond to morphogenetic cues - emerges as a fundamental principle ensuring the robust spatial and temporal progression of development [2]. The integration of YAP/TAZ-mediated mechanosensation with classic morphogen pathways creates a sophisticated regulatory system that translates tissue-scale forces into precise cellular responses [2] [16].

Future research directions will likely focus on identifying the potential existence of a mechanical organizer - a force-based counterpart to classical signaling centers that shape the early embryo [2]. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated synthetic embryo models and advanced mechanical measurement techniques will continue to bridge scales from molecular mechanisms to embryo-scale morphogenesis. These advances will not only deepen our understanding of human development but also provide novel approaches to regenerative medicine and fertility treatments by revealing the fundamental rules governing how mechanical forces guide the emergence of form in early embryogenesis [2].

The transformation of a homogeneous cell population into diverse, specialized lineages is a cornerstone of development and disease. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to elucidate how cells interpret extracellular signals not just from their identity, but from their dynamic patterns—their intensity, rhythm, and duration. We explore the core principle that signaling dynamics are a critical mechanism for dictating cell fate decisions, with a specific focus on the paradigm of gastrulation. By integrating quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual guides, this document provides researchers and drug developers with a technical framework for analyzing and manipulating these dynamic systems to control cellular outcomes.

Classical views of cell signaling often portrayed pathways as simple on-off switches in response to stimuli. However, the advent of single-cell live imaging and quantitative analysis has revealed a far more complex reality: signaling pathways exhibit a rich repertoire of dynamic behaviors, including oscillations, pulses, and sustained activation [18]. This temporal dimension is not mere biological noise; it is a fundamental feature of how cells process information and make reliable fate decisions amidst molecular stochasticity.

The concept of cell fate can be understood through the theoretical framework of Waddington's epigenetic landscape, modernized as a dynamical system of attractor states [18] [19]. In this model, distinct cell fates—such as survival, apoptosis, or differentiation—represent stable attractors. Signaling dynamics act as guiding forces, pushing cells from one basin of attraction to another, thereby determining the final developmental trajectory [18]. This review details how these principles operate during gastrulation, a pivotal developmental event, and provides the toolkit for their experimental dissection.

Molecular Mechanisms: Decoding Dynamics into Destiny

Several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways have been characterized as prime examples of dynamic information encoders. Their temporal patterns are decoded by the cell's molecular machinery to activate specific transcriptional programs.

NF-κB Oscillations and Immune Cell Fate

The NF-κB pathway is a paradigm for understanding how oscillatory dynamics control gene expression. In the canonical pathway, stimuli such as TNFα lead to the degradation of the inhibitor IκB, allowing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus. A key negative feedback loop, wherein NF-κB induces the transcription of IκBα, drives the oscillatory, nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of the transcription factor with a period of approximately 1.5 hours [18] [20].

- Functional Decoding: These oscillations are not just a byproduct of feedback; they are functional. Different genes are activated at different phases of the oscillation. Some responsive genes are rapidly induced by the first nuclear translocation peak, while others require repeated cycles or sustained activity for activation, enabling a single pathway to orchestrate a complex inflammatory response [18] [20]. The specific dynamic is shaped by the interplay of different IκB isoforms (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε), with IκBα knockout cells showing persistent, non-oscillatory NF-κB activation [20].

p53 Pulsatile Dynamics in DNA Damage Response

In response to DNA damage, the tumor suppressor p53 exhibits pulsatile dynamics. The number, amplitude, and duration of these pulses are not uniform; they vary with the type and intensity of the stressor [18]. This allows p53 to function as a dynamic decoder: different pulse patterns activate distinct sets of target genes that dictate cell fate outcomes, such as transient cell cycle arrest versus irreversible senescence or apoptosis [18].

BMP/WNT/Nodal Dynamics in Gastrulation and ExM Specification

Gastrulation and the specification of extraembryonic mesoderm (ExM) are exquisitely controlled by the dynamic interplay of BMP, WNT, and Nodal signaling. Research using human embryonic stem cell (hESC) models has demonstrated that precise modulation of these pathways can efficiently direct cell fate.

- ExM Specification Protocol: A defined protocol involving the combined treatment of naive hESCs with CHIR99021 (a GSK3 inhibitor that activates WNT signaling) and BMP4 in a specific medium (FH-N2B27) can induce differentiation into expandable ExM-like cells with over 90% efficiency within 4-5 days [3].

- Developmental Trajectory: This specification process proceeds through a primitive streak-like intermediate (PSLI), delineating a clear developmental roadmap [3]. The initial pluripotent state of the hESCs (naive vs. primed) influences the cellular response to these signals, affecting the developmental progression and transcriptional characteristics of the resulting ExM [3].

Table 1: Key Signaling Dynamics and Their Functional Outcomes

| Signaling Pathway | Stimulus/Context | Dynamic Pattern | Decoding Mechanism | Cell Fate Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB | TNFα / Immune Response | Damped oscillations (∼1.5 hr period) | Kinetics of IκB negative feedback; gene-specific activation thresholds | Inflammatory gene expression vs. cell survival [18] [20] |

| p53 | DNA Damage / Genotoxic Stress | Discrete pulses | Pulse number & amplitude; promoter-specific response | Cell cycle arrest vs. senescence vs. apoptosis [18] |

| BMP/WNT/Nodal | Gastrulation / ExM Specification | Sustained, combinatorial activation | Pathway synergy; primitive streak intermediate | Specification of Extraembryonic Mesoderm [3] |

Experimental Approaches: Mapping the Dynamic Landscape

Understanding the link between signaling dynamics and cell fate requires methodologies that capture temporal information at the single-cell level and connect it to functional outcomes.

Live-Cell Imaging and Single-Cell Analysis

The direct observation of signaling dynamics relies on live-cell microscopy of fluorescently tagged proteins (e.g., RelA-NF-κB) [18]. This allows for the quantification of translocation kinetics and oscillatory behavior in real-time. To connect these dynamics to lineage decisions, this imaging is integrated with single-cell transcriptomics. Computational tools like Topographer can then be applied to this data to reconstruct a "quantitative Waddington's landscape," infer transition probabilities between cell states, and identify branching points where fate decisions occur [19].

A Protocol for Perturbing Dynamics to Establish Causality

To move from correlation to causation, researchers must experimentally perturb signaling dynamics. The following methodology, derived from studies on ExM specification, provides a template [3].

- Objective: To test the causal role of BMP and WNT signaling dynamics in ExM specification from naive hESCs.

- Workflow Diagram:

- Key Reagents & Steps:

- Cell Line: Naive hESCs (e.g., AIC-N line) [3].

- Baseline Medium: FH-N2B27 (N2B27 medium supplemented with FGF4 and Heparin) [3].

- Signaling Agonists: CHIR99021 (a GSK3 inhibitor, activating WNT signaling) and BMP4 [3].

- Culture Duration: 4-5 days to achieve ~90% efficiency of ExM differentiation.

- Validation: Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry for ExM markers (GATA6, SNAIL, VIM, KDR, FLT1); scRNA-seq to characterize heterogeneity and confirm trajectory through a primitive streak-like intermediate [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles key reagents and tools essential for research in signaling dynamics and cell fate, as featured in the cited studies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Signaling Dynamics Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in Context |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | GSK3 inhibitor; activates WNT signaling | Directly modulates WNT pathway dynamics to specify ExM from hESCs [3]. |

| BMP4 | Ligand for BMP receptors | Provides the BMP signal component in combination with WNT activation for ExM induction [3]. |

| Fluorescent Protein-Tagged TFs (e.g., RelA-p65) | Live-cell imaging of transcription factor localization | Enables real-time tracking of NF-κB or other TF dynamics in single cells via microscopy [18]. |

| Topographer Algorithm | Computational analysis of scRNA-seq data | Constructs quantitative developmental landscapes and infers fate/transition probabilities from static snapshot data [19]. |

| TNFα | Cytokine; activator of NF-κB pathway | Standard stimulus used to induce and study the oscillatory dynamics of the NF-κB system [20]. |

| 2-Chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone | 2-Chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone | High Purity | High-purity 2-Chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 5-Phenylpenta-2,4-dienal | 5-Phenylpenta-2,4-dienal, CAS:13466-40-5, MF:C11H10O, MW:158.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core logic and dynamic feedback structures of the key pathways discussed.

The evidence is compelling: signaling dynamics are a fundamental and ubiquitous mechanism for controlling cell fate decisions from immune response to embryonic development. The quantitative study of these dynamics, powered by live-cell imaging, single-cell omics, and engineered stem cell models, has moved the field from observation to mechanistic understanding and predictive modeling.

Future research must focus on bridging the remaining gaps. This includes achieving a more comprehensive mechanistic understanding of how dynamic signals are precisely decoded at the level of chromatin and gene regulatory networks [18]. Furthermore, the innovative use of targeted therapies in oncology [21] underscores the translational potential of this field. As our ability to measure and model these complex temporal patterns improves, so too will our capacity to predict cellular behavior and design novel therapeutic interventions that manipulate cell fate in disease contexts such as cancer, degenerative disorders, and regenerative medicine. The journey from signal to fate, once a black box, is now a frontier of quantitative, dynamic, and therapeutic science.

Cell fate commitment during embryonic development is orchestrated by dynamic epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression without altering DNA sequences. This whitepaper examines how coordinated histone modification dynamics serve as central regulators of transcriptional programs governing cell lineage specification. Within the context of gastrulation research, we explore the sophisticated signaling dynamics that direct epigenetic reprogramming, with particular emphasis on zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and the establishment of germ layer identities. Integrating recent multi-omics findings, we present quantitative analyses of histone modification patterns, detailed experimental methodologies for profiling epigenetic dynamics, and essential reagent solutions for investigating chromatin remodeling during cell fate transitions.

The transition from pluripotency to committed cell fates represents a fundamental process in embryonic development, requiring precise spatial and temporal coordination of gene expression programs. Epigenetic regulations, particularly post-translational modifications of histone proteins, play indispensable roles in governing these cell fate decisions by modulating chromatin architecture and accessibility [22]. During gastrulation, embryonic cells undergo profound remodeling of their transcriptional identity, transitioning from the naive epiblast state to definitive germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) through tightly regulated epigenetic mechanisms [23]. These modifications create a chromatin landscape that either permits or restricts transcription factor binding, thereby controlling lineage-specific gene expression.

The signaling dynamics that coordinate gastrulation research provide critical context for understanding epigenetic regulation. Morphogen gradients—including BMP, WNT, FGF, and Nodal signaling pathways—converge on epigenetic modifiers to establish spatially organized gene expression patterns [23]. This interplay between extracellular signaling and intracellular epigenetic machinery enables the precise temporal control of developmental genes, particularly during ZGA when the embryonic genome assumes transcriptional control from maternally-derived factors [22] [24]. The investigation of these processes has been revolutionized by advanced low-input epigenomic profiling technologies that enable comprehensive mapping of histone modification dynamics throughout critical developmental transitions.

Molecular Dynamics of Histone Modifications During Cell Fate Transitions

Histone Modification Reprogramming During Zygotic Genome Activation

ZGA represents a critical developmental milestone characterized by rapid, simultaneous activation of previously silenced chromatin regions. Recent investigations in vertebrate models have revealed distinct regulatory requirements for different gene classes during this process. Table 1 summarizes the differential dependence of gene categories on specific histone modifications during ZGA.

Table 1: Gene-Specific Histone Modification Requirements During Zygotic Genome Activation

| Gene Category | Key Histone Modifications | Dependent Writers/Enzymes | Functional Role in ZGA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Genes | H3K27ac, H3.3S31ph | CBP/P300, BRD4 | Essential for activation; requires enhanced CBP/P300 activity [24] |

| Housekeeping Genes | H3K9ac, H4K16ac, H3K14ac | Non-CBP/P300 HATs | CBP/P300-independent activation [24] |

| Primed Developmental Loci | H3K4me3 (broad domains) | KDM5B (demethylase) | Prevents premature differentiation; removal required for ZGA [22] |

Research in teleost embryos demonstrates that developmental genes and housekeeping genes are distinctly regulated during ZGA. CBP/P300 histone acetyltransferase activity is specifically required for developmental gene activation but dispensable for housekeeping gene expression [24]. This specialization ensures precise temporal control of developmental programs while maintaining cellular homeostasis. The temporal accumulation of H3.3S31ph significantly enhances CBP/P300 activity specifically at ZGA, ensuring proper activation of developmental genes [24].

Histone Modification Dynamics in Mammalian Preimplantation Development

Mouse preimplantation development exhibits sophisticated histone modification dynamics that differ significantly from non-mammalian vertebrates. Table 2 quantifies the dynamics of key histone modifications during early embryonic development.

Table 2: Quantitative Dynamics of Histone Modifications in Mouse Preimplantation Development

| Histone Modification | Oocyte/MII Stage | Zygote Stage | 2-Cell Stage | Blastocyst Stage | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Broad domains [22] | Inheritance of broad domains [22] | Erasure of broad domains [22] | Canonical sharp peaks [22] | Transition required for ZGA and developmental competence [22] |

| H3K27me3 | Present at developmental loci [22] | Global erasure in paternal alleles [22] | Minimal promoter presence [22] | Re-established in lineage-specific patterns [22] | Prevents premature differentiation [22] |

| H3K27ac | Limited enrichment [24] | - | Progressive accumulation [24] | Enhancer-specific patterning [25] | Marks active enhancers and promoters [24] |

A notable feature of mammalian oocytes and zygotes is the presence of noncanonical H3K4me3 existing as broad domains, which are negatively correlated with DNA methylation [22]. These broad domains are inherited after fertilization but are actively removed by the late two-cell stage, a process requiring the activation of zygotic transcription [22]. The removal of these broad domains is essential for ZGA and full developmental potential, as artificial maintenance through knockdown of H3K4me3 demethylases (particularly KDM5B) disrupts lineage differentiation at the blastocyst stage [22].

Chromatin State Remodeling During Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Differentiation

The differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) provides an accessible model for investigating histone modification dynamics during cell fate commitment. During definitive endoderm differentiation, key developmental genes are transcribed before cell division, while chromatin accessibility analyses reveal early inhibition of alternative cell fates [25]. Enhancers are rapidly established and decommissioned between different cell divisions, demonstrating the dynamic nature of the epigenetic landscape during lineage commitment [25].

Histone modification patterns change progressively during this process, with activating marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) increasing at lineage-specific genes while repressive marks (H3K27me3) are deposited at genes associated with alternative fates [25]. The acquisition of these histone modifications occurs in a cell cycle-dependent manner, with early G1 phase representing a particularly permissive state for the initiation of differentiation [25].

Experimental Methodologies for Profiling Histone Modification Dynamics

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents the gold standard method for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications. The protocol involves specific crosslinking, immunoprecipitation, and sequencing steps that must be optimized for different biological contexts.

Table 3: Key Experimental Parameters for Histone Modification Profiling

| Method | Resolution | Sample Input Requirements | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq | 200-500 bp | 10,000-500,000 cells (standard); 100-1,000 cells (low-input) | Genome-wide mapping of histone modifications [26] | Antibody specificity critical; crosslinking optimization required [26] |

| CUT&RUN | ~150 bp | 1,000-50,000 cells | High-resolution mapping with lower background [26] | No crosslinking; requires permeabilization [26] |

| ATAC-seq | Single-nucleotide | 500-50,000 cells | Chromatin accessibility profiling [25] | Requires viable nuclei; sensitive to mitochondrial DNA [25] |

Detailed ChIP-seq Protocol:

- Crosslinking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 8-10 minutes at room temperature to fix protein-DNA interactions.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and fragment chromatin to 200-500 bp using sonication (15-20 cycles of 30-second pulses).

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate fragmented chromatin with specific histone modification antibodies (e.g., anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27ac) overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads sequentially with low-salt, high-salt, and LiCl buffers, then elute chromatin from beads.

- Reverse Crosslinking and Purification: Incubate eluates at 65°C overnight with proteinase K, then purify DNA using silica membrane columns.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using compatible kits and sequence on appropriate platforms (Illumina recommended).

For low-input applications (such as preimplantation embryos), adapted protocols utilizing carrier chromatin or specialized library preparation methods are essential [22]. Recent advances have enabled the application of ChIP-seq to single cells, though this remains technically challenging for histone modifications compared to transcription factors.

Multi-omics Integration Approaches

Comprehensive understanding of epigenetic coordination requires integration of multiple data types. Simultaneous profiling of histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, and transcriptome provides unprecedented insights into the regulatory logic of cell fate commitment. In synchronized hPSC differentiation systems, combined RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and histone modification ChIP-seq (H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K36me3) have revealed coordinated changes occurring between consecutive cell divisions [25].

Experimental workflows for multi-omics profiling typically involve:

- Cell Synchronization: Using chemical inhibitors or FUCCI reporter systems to obtain populations at specific cell cycle stages [25].

- Parallel Sample Processing: Dividing samples for simultaneous DNA, RNA, and chromatin analysis.

- Data Integration: Computational approaches to correlate histone modification patterns with gene expression changes and chromatin accessibility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Histone Modification Dynamics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Functional Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Acetyltransferase Inhibitors | A485, SGC-CBP30 [24] | Inhibition of CBP/P300 activity to investigate H3K27ac function [24] | A485 targets HAT domain; SGC-CBP30 targets bromodomain [24] |

| Histone Demethylase Inhibitors | KDM5B inhibitors [22] | Maintenance of broad H3K4me3 domains to study ZGA regulation [22] | Disrupts transition from noncanonical to canonical H3K4me3 [22] |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization Agents | Nocodazole, RO-3306 [25] | Cell cycle phase-specific analysis of epigenetic dynamics [25] | Nocodazole blocks mitosis; RO-3306 blocks G2/M transition [25] |

| Epigenomic Profiling Kits | Commercial ChIP-seq kits, ATAC-seq kits [26] | Standardized protocols for histone modification mapping [26] | Kit performance varies by application; validation required [26] |

| Pluripotency and Differentiation Media | Defined hPSC media, endoderm differentiation kits [25] | Controlled differentiation for epigenetic studies [25] | Serum-free formulations enhance reproducibility [25] |

| Europium bromide (EuBr3) | Europium bromide (EuBr3), CAS:13759-88-1, MF:Br3Eu, MW:391.68 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Isopropylcyclopentanone | 2-Isopropylcyclopentanone, CAS:14845-55-7, MF:C8H14O, MW:126.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Dynamics and Epigenetic Coordination in Gastrulation

The signaling dynamics that characterize gastrulation intersect with epigenetic regulation through multiple mechanisms. Morphogen signaling pathways directly modify the activity of epigenetic regulators, creating a framework for spatial patterning of the embryo. The following diagram illustrates the integration of signaling pathways with epigenetic modifications during cell fate commitment:

Signaling and Epigenetic Coordination in Gastrulation

Key signaling pathways operational during gastrulation include:

- BMP Signaling: Promotes ventral mesodermal fates and modulates histone acetylation through SMAD effectors.

- WNT/β-catenin Signaling: Regulates brachyury and posterior mesodermal genes through interaction with CBP/P300 HAT complexes.

- FGF Signaling: Supports mesodermal commitment and influences histone methylation patterns.

- Nodal/Activin Signaling: Directs endodermal and mesodermal fates through SMAD2/3-mediated recruitment of epigenetic regulators.

These signaling pathways converge on lineage-specific transcription factors that subsequently recruit epigenetic modifiers to establish appropriate chromatin states. For example, during endoderm differentiation, transcription factors such as EOMES, GATA6, SOX17, and FOXA2 recruit chromatin remodeling complexes to activate endodermal genes while repressing alternative lineages [25]. The p38/MAPK signaling pathway controls Activator protein-1 members that are necessary for inducing endoderm while blocking cell fate shifting toward mesoderm [25].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for investigating histone modification dynamics in cell fate commitment:

Experimental Workflow for Epigenetic Analysis

The coordination of histone modification dynamics represents a fundamental mechanism underpinning cell fate commitment during embryonic development. The integration of signaling pathways with epigenetic regulation creates a robust system for spatial and temporal control of gene expression programs essential for proper embryogenesis. Advances in low-input epigenomic technologies have revealed unprecedented details of these processes, demonstrating distinct regulatory requirements for different gene classes and developmental stages. The continued refinement of experimental approaches—particularly multi-omics integration and single-cell analyses—will further elucidate the complex epigenetic coordination governing cell fate decisions. These insights not only enhance our understanding of normal development but also provide critical frameworks for manipulating cell identities in regenerative medicine and disease modeling.

Advanced Tools and Models: From Live Imaging to Synthetic Embryos for Decoding Gastrulation

Gastrulation is a fundamental process in embryonic development, during which the simple blastula undergoes a complex reorganization to form the three primary germ layers. While the biochemical signaling dynamics that guide cell fate and movement during this process have been extensively studied, a complete understanding requires equal consideration of the physical forces and mechanical properties that enable morphogenesis. The role and importance of mechanical properties of cells and tissues in cellular function, development and disease has widely been acknowledged, however standard techniques currently used to assess them exhibit intrinsic limitations [27]. Techniques such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) and optical tweezers, while valuable, typically require physical contact with samples or are limited to surface measurements, making them unsuitable for probing the dynamic, three-dimensional mechanical changes occurring within intact, living embryos [27] [28].

In recent years, Brillouin microscopy has emerged as a non-destructive, label- and contact-free method that can probe the viscoelastic properties of biological samples with diffraction-limited resolution in 3D [27]. This all-optical technique enables mechanical characterization without disturbing the delicate physiological processes of development, providing a powerful new tool for investigating the role of biomechanics in gastrulation. By integrating mechanical data with information from biochemical signaling pathways, researchers can develop a more holistic understanding of how embryos transform from simple spherical structures into complex organisms with multiple tissue layers and axes.

This technical guide explores the principles, implementations, and applications of Brillouin microscopy specifically within the context of embryonic mechanobiology, detailing how this technology is revolutionizing our ability to map mechanical property dynamics during critical developmental events such as gastrulation.

Technical Foundations of Brillouin Microscopy

Core Physical Principles

Brillouin microscopy is based on the physical phenomenon of Brillouin light scattering (BLS), an inelastic scattering process that occurs when light interacts with thermally-driven acoustic vibrations or phonons within a material [28]. As photons propagate through a medium, a minute fraction undergoes energy exchange with the material's intrinsic density fluctuations. This interaction produces scattered light with a slightly shifted frequency compared to the incident light.

The key measurable parameters in Brillouin spectroscopy are:

- Brillouin shift (νB): The frequency shift between incident and scattered light, typically in the gigahertz (GHz) range for biological materials

- Brillouin linewidth (ΓB): The spectral width of the Brillouin peak, related to the viscous damping of acoustic waves

The Brillouin shift relates to the longitudinal modulus M' of the material through the equation:

[

ν_B = \frac{2n}{λ} \sqrt{\frac{M'}{Ï}}

]

where n is the refractive index, λ is the wavelength of the incident light, and Ï is the mass density [28]. The longitudinal modulus represents the material's resistance to compression under confined conditions and is typically 2-3 orders of magnitude larger than the more commonly referenced Young's modulus [17].

Figure 1: Fundamental principle of Brillouin light scattering. Incident light interacts with thermal acoustic vibrations in the sample, producing elastically scattered Rayleigh light and inelastically scattered Brillouin components (Stokes and Anti-Stokes) with characteristic frequency shifts.

Technical Implementations and Advancements

Brillouin microscopy has evolved through several technological generations, each addressing key limitations in speed, resolution, or phototoxicity:

Confocal Brillouin Microscopy

The earliest implementations were based on confocal scanning approaches, where a single spatial point is measured at a time [27]. While providing valuable mechanical information with diffraction-limited resolution, this method suffers from slow acquisition speeds (typically minutes to hours for a 3D volume) and relatively high illumination dosages that can cause photodamage in living samples [29].

Line-Scan Brillouin Microscopy (LSBM)

To address speed limitations, line-scan Brillouin microscopy was developed, enabling parallel acquisition of hundreds of points simultaneously [29]. This approach reduces acquisition times by approximately two orders of magnitude while simultaneously decreasing phototoxicity through the use of near-infrared (780 nm) illumination instead of the more common 532 nm lasers [29]. LSBM can be implemented in two primary configurations:

- Orthogonal-line (O-LSBM): Illumination and detection axes are separated in a 90° configuration, similar to light-sheet microscopy, minimizing total illumination dosage for volumetric imaging

- Epi-line (E-LSBM): Sample is illuminated by a focused line in a 180° backscattered geometry, mitigating effects of scattering and optical aberrations [29]

Fourier-Transform Brillouin Microscopy (FTBM)

The most recent advancement is Fourier-transform Brillouin microscopy, which enables full-field 2D spectral imaging by exploiting a custom-built imaging Fourier-transform spectrometer and the symmetric properties of the Brillouin spectrum [30]. This approach can acquire up to 40,000 spectra per second, representing an approximately three-orders-of-magnitude improvement in speed compared to standard confocal methods while maintaining high spatial resolution [30].

Table 1: Comparison of Brillouin Microscopy Modalities

| Parameter | Confocal Brillouin | Line-Scan Brillouin (LSBM) | Fourier-Transform Brillouin (FTBM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Method | Single-point scanning | Parallel line acquisition | Full-field 2D imaging |

| Typical Acquisition Time | Minutes to hours for 3D volumes | ~2 minutes for 3D volumes | Up to 40,000 spectra/second |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited | ~1.5 μm laterally | Diffraction-limited |

| Laser Wavelength | Typically 532 nm | 780 nm (reduced phototoxicity) | Configurable |

| Key Advantages | High signal-to-noise | Balanced speed and viability | Extreme speed for 2D imaging |

| Limitations | Slow, potentially phototoxic | Limited to 1D multiplexing | New technology, limited adoption |

Application to Embryonic Development: Mapping Gastrulation Mechanics

Technical Workflow for Live Embryo Imaging

The application of Brillouin microscopy to living embryos requires careful consideration of sample preparation, environmental control, and data processing. The following workflow has been successfully implemented for studying Drosophila, ascidian, and mouse embryogenesis [29]:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for Brillouin microscopy of live embryos, showing key steps from sample preparation through data analysis.

Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Brillouin Microscopy in Developmental Biology

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Narrowband Diode Laser | Excitation source for Brillouin scattering | 780 nm wavelength, 50 kHz linewidth, frequency stabilization [29] |

| High-NA Objectives | Optimal light collection and spatial resolution | NA 0.8, water immersion [29] |

| Virtually Imaged Phase Array (VIPA) | High-resolution spectral analysis of scattered light | Spectral resolution <0.5 GHz [27] |

| Atomic Gas Cell Filter | Suppression of elastically scattered Rayleigh light | ~80 dB background suppression [29] |

| Environmental Chamber | Maintenance of embryo viability during imaging | Temperature, COâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚ control [29] |

| Fluorescent Membrane Markers | Correlation of mechanical properties with cellular structures | Genetically encoded fluorescent proteins [29] |

| GPU-Accelerated Analysis Software | Real-time processing of Brillouin spectra | >1000× speed enhancement vs CPU processing [29] |

Case Study: Mechanical Dynamics During Drosophila Gastrulation

Drosophila melanogaster embryogenesis provides an excellent model for studying the mechanical aspects of gastrulation due to its well-characterized development and genetic tractability. Recent Brillouin microscopy studies have revealed fascinating mechanical dynamics during key morphogenetic events:

Ventral Furrow Formation (VFF)

During VFF, mesodermal cells on the ventral side of the embryo undergo apical constriction, leading to tissue invagination. LSBM imaging has captured a transient increase in Brillouin shift (10-20 MHz) within the mesoderm, peaking at the initiation of invagination [29] [17]. This mechanical stiffening coincides with the reorganization of sub-apical microtubules, and disruption of microtubules with Colcemid reduces the Brillouin shift during VFF, suggesting microtubules contribute to this mechanical transition [17].

Posterior Midgut Invagination (PMI)

Similar to VFF, PMI involves tissue folding but with a circular contractile domain geometry. Brillouin imaging revealed a comparable increase in Brillouin shift during this process, suggesting that mechanical stiffening is a common feature of tissue folding independent of the specific geometry [29].