Single-Cell vs Bulk RNA Sequencing in Developmental Biology: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a detailed comparison of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and bulk RNA sequencing for developmental biology studies.

Single-Cell vs Bulk RNA Sequencing in Developmental Biology: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and bulk RNA sequencing for developmental biology studies. It covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and specific applications in embryonic and tissue development. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content addresses key technical challenges, offers optimization strategies, and delivers a practical framework for selecting the appropriate methodology. By synthesizing current research and technological advancements, this guide serves as a critical resource for designing robust developmental studies and interpreting complex transcriptomic data.

Core Principles: Why Cellular Resolution Revolutionized Developmental Biology

The journey to understand gene expression has been revolutionized by sequencing technologies, moving from a broad, population-level view to the precise examination of individual cells. Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) provides a composite gene expression profile from a population of cells, offering a macroscopic view of transcriptional activity. In contrast, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dissects this population to reveal the transcriptome of each individual cell, uncovering heterogeneity masked by averaged signals [1] [2]. This fundamental difference in resolution frames every subsequent choice between these technologies, from experimental design to biological interpretation. As research increasingly focuses on complex tissues and dynamic processes like development and disease progression, understanding the capabilities, applications, and limitations of each approach becomes essential for designing effective studies and generating meaningful biological insights.

Bulk RNA-seq analyzes the collective RNA from thousands to millions of cells simultaneously, producing an averaged gene expression profile for the entire sample [1] [3]. This approach is analogous to hearing the blended sound of a full orchestra—you perceive the overall musical piece but cannot distinguish individual instruments. The technology works by extracting total RNA from a tissue sample or cell culture, converting it to complementary DNA (cDNA), and sequencing it to quantify expression levels across all genes in the genome [1] [4].

Single-cell RNA-seq operates at a fundamentally different resolution, enabling researchers to measure gene expression in individual cells [1] [2]. Rather than analyzing a homogenized mixture, scRNA-seq first dissociates tissues into single-cell suspensions, isolates individual cells into separate reaction chambers (typically using microfluidic devices), barcodes each cell's RNA to track its origin, and then sequences the pooled libraries [1] [4]. This process is like giving each orchestra member an individual microphone—suddenly, you can identify exactly which instrument is playing each note and how their contributions blend to create the symphony.

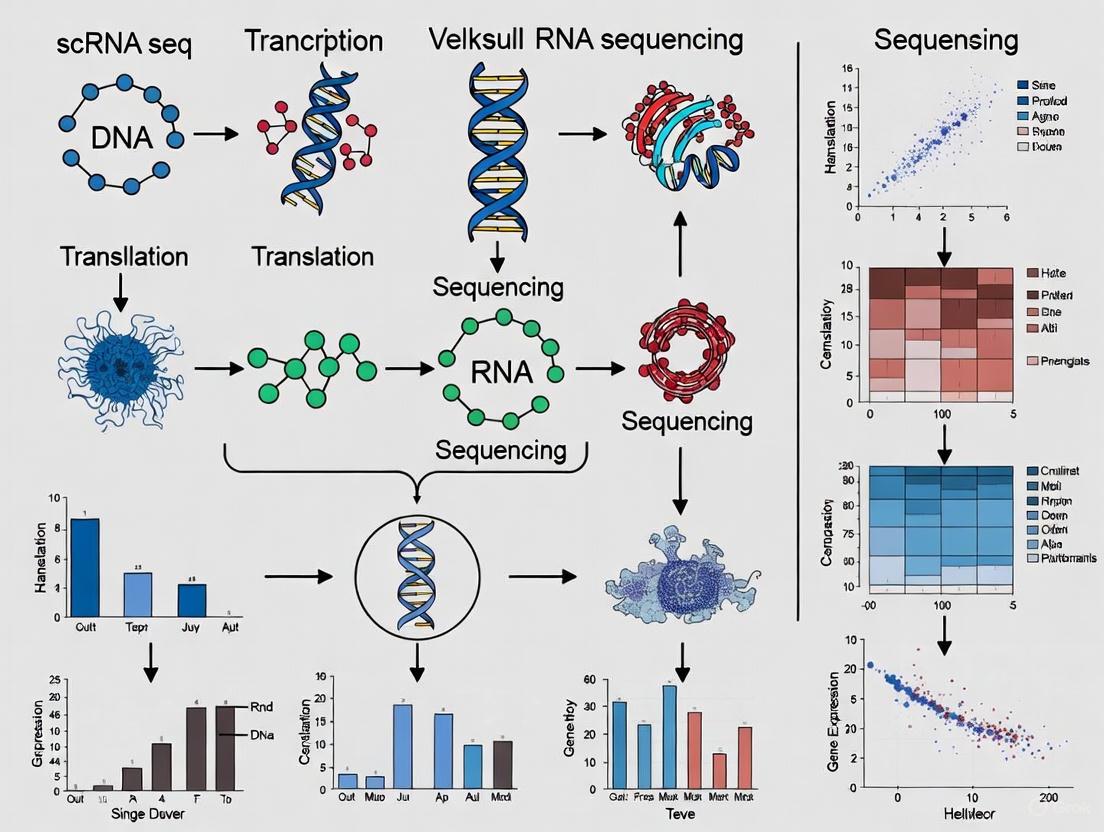

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow differences between these two approaches:

Quantitative Comparison: Technical Specifications and Performance

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing involves balancing multiple factors including resolution, cost, data complexity, and application suitability. The table below summarizes the key differences based on current technological capabilities:

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [1] | Individual cell level [1] |

| Cost per sample | Lower (~$300 per sample) [3] | Higher (~$500-$2000 per sample) [3] |

| Data complexity | Lower, more straightforward analysis [1] [3] | Higher, requires specialized computational methods [1] [3] |

| Cell heterogeneity detection | Limited, masks cellular diversity [1] [2] | High, reveals cellular subpopulations [1] [2] |

| Sample input requirement | Higher, typically micrograms of RNA [3] | Lower, single cells or nanograms of RNA [3] |

| Rare cell type detection | Limited, masked by abundant populations [3] | Possible, can identify rare populations [3] |

| Gene detection sensitivity | Higher, detects more genes per sample [3] | Lower due to transcript dropout [3] |

| Splicing analysis | More comprehensive [3] | Limited with standard methods [3] |

| Technical noise | Lower, averaged across cells [4] | Higher, includes amplification artifacts [4] |

| Experimental workflow | Simpler, established protocols [1] | More complex, requires single-cell suspension [1] |

Beyond these fundamental differences, scRNA-seq introduces unique technical considerations. The "transcriptome size" - the total number of mRNA molecules per cell - varies significantly across cell types and can impact data normalization and interpretation [5]. New computational methods like ReDeconv specifically address this challenge by incorporating transcriptome size into scRNA-seq normalization, improving accuracy in both single-cell analysis and bulk data deconvolution [5].

Experimental Design: Methodologies and Protocols

Bulk RNA-seq Experimental Protocol

Standard bulk RNA-seq follows a relatively straightforward workflow optimized for population-level analysis [1]:

Sample Collection and Homogenization: Tissue samples or cell pellets are collected and immediately stabilized using RNA preservation reagents. Samples are homogenized using mechanical disruption to lyse cells and release RNA.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Total RNA is extracted using column-based or magnetic bead-based methods. RNA quality is assessed using bioanalyzer systems to ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.0 for optimal sequencing results.

Library Preparation: Following poly-A selection or ribosomal RNA depletion, RNA is reverse transcribed into cDNA. Adapters containing sample-specific barcodes are ligated to enable multiplexed sequencing. Library concentration and quality are validated using quantitative PCR and fragment analyzers.

Sequencing and Data Analysis: Libraries are sequenced on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq to a depth of 20-50 million reads per sample. Data analysis includes quality control, alignment to reference genomes, and differential expression analysis using tools like DESeq2 or edgeR.

Single-Cell RNA-seq Experimental Protocol

scRNA-seq requires more specialized procedures to preserve single-cell resolution [1] [4]:

Single-Cell Suspension Preparation: Tissues are dissociated using enzymatic (collagenase, trypsin) or mechanical methods optimized for specific tissue types. Cell viability is critical and typically maintained above 80% using cold-active proteases and rapid processing.

Cell Partitioning and Barcoding: Single-cell suspensions are loaded into microfluidic devices (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium system) where individual cells are partitioned into nanoliter-scale droplets (GEMs) with barcoded beads. Each bead contains oligonucleotides with unique cell barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and poly-T sequences for mRNA capture.

Reverse Transcription and Library Construction: Within each droplet, cells are lysed and mRNA is captured by the barcoded oligos. Reverse transcription occurs in isolation, tagging each cDNA molecule with its cell-of-origin barcode. After breaking droplets, cDNA is amplified and sequencing libraries are constructed.

Sequencing and Computational Analysis: Libraries are sequenced to greater depth (typically 50,000-100,000 reads per cell). Data processing involves cell calling, demultiplexing using barcode information, UMI counting, and normalization. Downstream analysis includes clustering, cell type identification, and trajectory inference using tools like Seurat or Scanpy.

The following diagram illustrates the core single-cell partitioning and barcoding process that enables cellular resolution:

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Applications of Bulk RNA Sequencing

Bulk RNA-seq remains the preferred choice for several research scenarios [1] [3]:

Differential Gene Expression Analysis: Identifying genes that are upregulated or downregulated between different conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy, treated vs. control) across entire tissues or populations.

Biomarker Discovery: Detecting molecular signatures for disease diagnosis, prognosis, or patient stratification. For example, bulk RNA-seq of cancer samples has identified gene expression signatures predictive of treatment response and survival outcomes [3].

Large-Scale Cohort Studies: Profiling transcriptomes across hundreds or thousands of samples in biobank projects where cost considerations make scRNA-seq prohibitive.

Pathway and Network Analysis: Studying how sets of genes change collectively under various biological conditions, providing systems-level insights.

Novel Transcript Characterization: Discovering and annotating isoforms, non-coding RNAs, alternative splicing events, and gene fusions, with applications in cancer research where fusion genes can drive oncogenesis [4].

Applications of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

scRNA-seq enables applications that are impossible with bulk approaches [1] [6]:

Cellular Atlas Construction: Systematically cataloging all cell types and states within complex tissues, as demonstrated by the Human Cell Atlas project [2].

Rare Cell Population Identification: Discovering and characterizing rare cell types that may have crucial biological functions, such as cancer stem cells in tumors or rare immune cell subsets [3].

Developmental Trajectory Reconstruction: Mapping lineage relationships and differentiation pathways by ordering cells along pseudotemporal trajectories, revealing how progenitor cells give rise to specialized descendants [1] [2].

Tumor Heterogeneity Characterization: Resolving diverse cell populations within cancers, including cancer cell subtypes, immune infiltrates, and stromal components, providing insights into therapy resistance mechanisms [4].

Drug Discovery and Development: Informing target identification through improved disease understanding, identifying cell types most sensitive to perturbations, and providing insights into drug mechanisms of action [6]. scRNA-seq can profile drug responses at single-cell resolution, revealing how different cell subpopulations within tumors respond to therapies [7].

The integration of both approaches is increasingly powerful. For instance, a 2024 study on B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) leveraged both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq to identify developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to asparaginase chemotherapy [1]. Similarly, computational frameworks like scDEAL can transfer drug response knowledge from large-scale bulk databases to predict single-cell drug sensitivity, bridging the two technologies [7].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of RNA sequencing technologies requires specific reagents and platforms optimized for each approach:

| Item | Function | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA integrity post-collection | RNAlater, TRIzol | RPMI + FBS, Cold-active protease inhibitors |

| Cell Dissociation Kits | Tissue dissociation into single cells | Not typically required | Enzymatic mixes (collagenase/trypsin), GentleMACS dissociator |

| Viability Stains | Assess cell health and membrane integrity | Trypan blue | Propidium iodide, DAPI, Calcein AM |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality RNA | Column-based (RNeasy), Magnetic beads | Same, but with DNase treatment |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries | Illumina TruSeq, NEBNext Ultra II | 10X Genomics Chromium, SMART-seq kits |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer, Fragment Analyzer | Bioanalyzer, Cell Counter (Countess) |

| Sequencing Platforms | Generate sequence data | Illumina NovaSeq, NextSeq | Illumina NovaSeq, HiSeq with high depth |

| Cell Partitioning Systems | Isolate individual cells | Not applicable | 10X Genomics Chromium, Fluidigm C1 |

| Barcoded Beads | Label cell-of-origin for transcripts | Not applicable | 10X Gel Beads, Drop-seq beads |

| Single-Cell Multiome Kits | Simultaneously profile multiple molecular layers | Not applicable | 10X Multiome (ATAC + Gene Exp.) |

Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing represent complementary rather than competing approaches for transcriptome analysis. Bulk RNA-seq provides an economical, robust method for assessing overall transcriptional changes in homogeneous populations or when studying systemic responses. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the cellular heterogeneity, rare populations, and dynamic transitions that underlie these population-level observations, albeit at higher cost and computational complexity [1] [8].

The choice between technologies depends fundamentally on the research question. Bulk sequencing remains ideal for differential expression analysis in well-defined systems, large-scale cohort studies, and when working with limited budgets. Single-cell approaches are essential for characterizing heterogeneous tissues, discovering novel cell types, reconstructing developmental trajectories, and understanding cellular responses to perturbations in complex systems [3].

Looking forward, the integration of both approaches through computational methods, along with emerging spatial transcriptomics technologies, promises a more complete understanding of biological systems across scales. As both technologies continue to evolve—with costs decreasing and methodologies improving—their synergistic application will further accelerate discoveries in basic biology, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development.

For decades, bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) has been a fundamental tool in molecular biology, providing valuable insights into the average gene expression profile of entire tissue samples or cell populations [1] [4]. This method works by extracting RNA from a heterogeneous mixture of cells, processing it into a sequencing library, and generating a composite readout that represents the mean expression levels for each gene across all cells in the sample [1]. While this approach has proven invaluable for identifying differentially expressed genes between conditions and discovering biomarkers, it operates under a significant constraint: the complete loss of cellular resolution [2] [9].

The critical limitation of bulk RNA-seq becomes apparent when studying complex tissues—such as tumors, brain structures, or developing organs—where cellular heterogeneity is the rule rather than the exception [2] [4]. By providing only a "virtual average" of gene expression across diverse cell types, bulk RNA-seq fundamentally masks the cellular origins of transcriptional signals [2]. This averaging effect obscures rare but biologically important cell populations, blends distinct cellular states, and conceals the true complexity of transcriptional regulation that occurs at the single-cell level [9] [10]. As the field advances toward more precise analytical approaches, understanding this limitation becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals designing transcriptomic studies.

Quantitative Comparison: Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

The technological differences between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing translate directly into distinct analytical capabilities. The table below summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics that highlight the resolution gap between these approaches.

Table 1: Technical and Analytical Comparison of Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-Seq

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [1] | Single-cell [1] |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Masked [2] [11] | Revealed [2] [9] |

| Rare Cell Detection | Limited (>1% frequency) [12] | Excellent (<0.1% frequency) [12] |

| Required RNA Input | High (micrograms) [4] | Low (picograms per cell) [9] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [1] [11] | Higher [1] |

| Data Complexity | Moderate [1] | High-dimensional [1] [9] |

| Ideal Applications | Differential expression, biomarker discovery [1] | Cell atlas construction, heterogeneity studies, developmental trajectories [1] [12] |

Table 2: Sensitivity Comparison in Complex Tissue Analysis

| Analysis Type | Gene Detection Rate | Rare Cell Population Detection | Identification of Novel Subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-Seq | Comprehensive for abundant transcripts [4] | Poor (signals diluted) [2] | Not possible [2] |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Variable (3-20% mRNA recovery per cell) [9] | Excellent (theoretical limit: 1 in 10,000 cells) [12] | High (unbiased approach) [2] [10] |

The fundamental difference in data output can be visualized as a contrast between averaged and resolved transcriptional profiles:

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies Revealing Hidden Heterogeneity

Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Tissue Analysis

A compelling 2024 study integrated both bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing to investigate macrophage heterogeneity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovial tissue [13]. Researchers began with bulk RNA-seq analysis of 213 RA samples and 63 healthy controls, which identified general inflammatory pathways but failed to resolve specific macrophage subpopulations driving disease progression [13].

When the same tissues were analyzed using scRNA-seq, researchers profiled 26,923 individual cells and identified previously obscured macrophage subsets, including a distinct Stat1+ macrophage population that expressed unique inflammatory signatures [13]. The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

- Tissue Processing: Synovial tissues were dissociated into single-cell suspensions using enzymatic digestion (collagenase IV/DNase I) [13]

- Cell Viability Assessment: Viable cell count and quality control to ensure >90% viability [13]

- Single-Cell Partitioning: Cells were loaded onto a Chromium X series instrument (10x Genomics) for droplet-based partitioning [13]

- Library Preparation: GEM (Gel Bead-in-emulsion) generation with cell barcoding and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [13]

- Sequencing: Illumina-based sequencing to a depth of 50,000 reads per cell [13]

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Cell clustering, differential expression, and trajectory analysis using Seurat (v5.0.1) and Monocle3 [13]

This scRNA-seq approach revealed that Stat1+ macrophages were enriched in inflammatory pathways and represented a key driver of RA pathology—a finding completely masked in the bulk analysis [13]. Functional validation confirmed that STAT1 activation modulated autophagy and ferroptosis pathways, suggesting new therapeutic targets for RA [13].

Cancer Stem Cell and Tumor Heterogeneity Studies

In oncology, bulk RNA-seq has historically provided averaged expression profiles that obscure critical rare cell populations. Studies comparing bulk and single-cell approaches in tumors have demonstrated that bulk sequencing consistently underestimates heterogeneity and misses biologically significant rare populations [4].

For example, scRNA-seq applications in glioblastoma, colorectal cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma have revealed:

- Rare stem-like cells with treatment-resistant properties that comprise <1% of tumor mass [4]

- Partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (p-EMT) programs associated with metastasis [4]

- Distinct cancer cell states that develop drug resistance after targeted therapy [4]

The experimental workflow for such tumor heterogeneity studies typically involves:

Table 3: Key Methodological Steps in Tumor Heterogeneity Analysis

| Step | Description | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Generate viable single-cell suspension from tumor tissue [1] | Maintain cell viability, minimize stress responses [1] |

| Cell Partitioning | Isolate individual cells using microfluidic devices [1] [4] | Optimize cell concentration to minimize doublets [2] |

| mRNA Capture & Barcoding | Lysed cells release mRNA captured with cell-specific barcodes [4] | Use UMIs to correct for amplification bias [9] |

| Library Preparation | Amplify cDNA and prepare sequencing libraries [1] | Maintain representation of low-abundance transcripts [9] |

| Bioinformatic Analysis | Cluster cells, identify subpopulations, reconstruct trajectories [13] | Address technical noise, batch effects [9] [13] |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Heterogeneity Studies

Comprehensive scRNA-seq Workflow for Detecting Cellular Heterogeneity

The following diagram outlines the standardized workflow for single-cell RNA sequencing experiments designed to uncover cellular heterogeneity:

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium [1] [4], BD Rhapsody [14], Fluidigm C1 [2] | Partition thousands of single cells with barcoding capabilities |

| Cell Barcoding Reagents | Gel Beads with cell barcodes & UMIs [4] | Label individual cell's RNA for multiplexing and quantification |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Optimized enzymes with high efficiency [9] | Convert minute RNA amounts to stable cDNA with low bias |

| Amplification Reagents | Template-switching oligonucleotides [9] | Amplify cDNA while maintaining representation |

| Cell Viability Assays | Fluorescent viability dyes [1] | Distribute live cells for high-quality RNA recovery |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Kits | Tissue-specific collagenase blends [1] | Dissociate tissues into single cells with minimal RNA degradation |

The critical limitation of bulk RNA-seq in masking cellular heterogeneity has profound implications across biomedical research and therapeutic development. While bulk approaches remain valuable for population-level differential expression analysis in homogeneous samples or when budget constraints predominate [1] [11], their inability to resolve cellular diversity makes them insufficient for characterizing complex biological systems [2] [4].

The advent of robust single-cell RNA sequencing technologies has fundamentally transformed our investigative capabilities, enabling researchers to identify novel cell types, trace developmental trajectories, characterize tumor microenvironments, and uncover rare cell populations that drive disease progression [13] [12] [4]. For drug development professionals, these advances translate into improved target identification, better patient stratification strategies, and enhanced understanding of therapeutic mechanisms of action and resistance [15].

As the field continues to evolve, the strategic integration of both approaches—using bulk RNA-seq for initial screening and scRNA-seq for deep resolution of heterogeneity—represents the most powerful paradigm for comprehensive transcriptomic analysis in developmental studies and disease research [1] [13].

How scRNA-Seq Reveals Rare Cell Populations and Lineage Trajectories

For decades, developmental biology relied on bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq), which averages gene expression across entire tissue samples. While valuable for identifying major expression shifts, this approach obscures a fundamental biological truth: cellular heterogeneity. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the field by providing a high-resolution lens to observe the individual cells that constitute developing tissues, uncovering rare cell populations and mapping lineage trajectories that were previously invisible.

The Resolution Revolution: scRNA-seq vs. Bulk RNA-seq

At its core, the difference between these techniques is one of resolution. Bulk RNA-seq processes RNA from a population of cells, yielding a population-average gene expression profile [1] [3]. In contrast, scRNA-seq isolates individual cells, captures their RNA, and uses cellular barcodes to trace each transcript back to its cell of origin [1] [4]. This fundamental difference in approach dictates their respective applications and findings.

Table 1: Core Technical Differences Between Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [1] [16] | Individual cell level [1] [3] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited; masks differences [1] [3] | High; reveals distinct subpopulations [2] [16] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited; signals are diluted [17] [3] | Possible; can identify very rare cells [17] [18] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [3] | Higher [3] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; more straightforward analysis [1] [3] | Higher; requires specialized computational tools [3] |

| Ideal Application | Differential expression in homogeneous samples, biomarker discovery [1] | Deconstructing heterogeneous tissues, identifying novel cell types, lineage tracing [1] [2] |

The limitation of bulk sequencing becomes critical when studying development. As noted in one review, "analysis of pooled populations of progenitor cells does not enable distinction of the signals that drive a progenitor down a particular differentiation pathway; for instance, the signals that determine whether a nephron progenitor cell becomes a podocyte or a proximal tubule cell" [2]. scRNA-seq makes these critical early fate decisions visible.

Pinpointing the Needle in the Haystack: Identifying Rare Cell Populations

Rare cell types, such as stem cells, transitional progenitors, or drug-resistant clones, often play disproportionately important roles in development and disease. Their low abundance means their transcriptional signatures are diluted to undetectable levels in bulk analyses [17]. scRNA-seq excels at finding these needles in the cellular haystack.

Case Study: Uncovering Tumor-Initiating Cells

A compelling example comes from cancer research. A 2025 study of triple-negative breast cancer used a STAT-signaling reporter system to enrich for tumor-initiating cells (TICs), a rare population associated with therapy resistance and recurrence. Subsequent scRNA-seq revealed a distinct IFN/STAT1-associated transcriptional state in these TICs. Notably, most of these identified genes were absent from previously published TIC signatures derived using bulk RNA-seq, demonstrating scRNA-seq's unique power to uncover molecular drivers hidden in rare populations [18].

General Experimental Workflow for Rare Cell Analysis

The process for identifying rare cells typically involves the following steps, which can be adapted for various tissues and research questions [17]:

- Tissue Dissociation & Single-Cell Suspension: The starting tissue is dissociated using enzymatic or mechanical methods to create a viable single-cell suspension. This step is critical, as it must preserve cell integrity and minimize stress-induced transcriptional changes [1] [17].

- Cell Viability QC & Optional Enrichment: Cell concentration and viability are assessed. For pre-defined rare populations, Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) using specific cell surface markers or fluorescent reporters can be used for enrichment prior to sequencing [17].

- Single-Cell Partitioning & Barcoding: Using platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium, single cells are partitioned into nanoliter-scale droplets (GEMs) along with barcoded beads. Each bead contains oligonucleotides with a unique cell barcode (to tag all RNAs from one cell) and a unique molecular identifier (UMI) to quantify individual transcripts [1] [4].

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Within the droplets, cells are lysed, mRNA is barcoded, and sequencing libraries are constructed. These are then pooled for high-throughput sequencing [1].

- Bioinformatic Clustering & Rare Population Identification: Sequenced reads are demultiplexed using the cell barcodes. Dimensionality reduction and clustering algorithms (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy) group cells based on similar gene expression profiles. Rare populations appear as distinct, small clusters that can be characterized by their unique marker genes [17] [2].

Reconstructing Developmental Pathways: Lineage Tracing with scRNA-seq

Beyond identifying static cell types, scRNA-seq can be coupled with lineage tracing to reconstruct the dynamic history of cell fate decisions, answering the fundamental question: "How does a single progenitor cell give rise to diverse, differentiated progeny?"

The Emergence of Single-Cell Lineage Tracing (SCLT)

Traditional lineage tracing uses fluorescent proteins to mark progenitor cells and their descendants. However, its resolution is limited. Single-cell lineage tracing (SCLT) combines the principles of lineage tracing with the power of scRNA-seq to map lineage connectivity at single-cell resolution, making it "the best tool for exploring the heterogeneity of cellular differentiation" [19].

Methodologies for SCLT

Several innovative methods have been developed to record lineage information within a cell's genome or transcriptome.

Table 2: Key Single-Cell Lineage Tracing (SCLT) Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism | Key Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Barcodes [19] | A library of viral vectors with random DNA "barcodes" is used to transduce progenitor cells. Each integration event provides a heritable, unique clonal marker. | Enables simultaneous tracking of thousands of clones, great for studying hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) dynamics. | Tracking HSC-derived clones in transplantation studies to understand clonal dynamics. |

| CRISPR Barcoding [19] | A CRISPR/Cas9 system introduces cumulative insertions/deletions (InDels) into a defined genomic "barcode" locus over cell divisions. The mutation pattern serves as a mitotic history record. | Creates a high diversity of lineage marks; mutations accumulate irreversibly over time. | Reconstructing developmental lineage trees in model organisms. |

| Base Editors [19] | Engineered base editors introduce point mutations at a high rate into a synthetic barcoding sequence, recording cell division events. | Allows for recording of many more mitotic divisions, enabling construction of high-resolution cell phylogenetic trees. | Quantifying the number of actively dividing parental cells and their division patterns during development. |

| Natural Barcodes [19] | Utilizes spontaneously acquired somatic mutations in the nuclear or mitochondrial genome that accumulate during development and aging. | Non-invasive and can be applied to human samples without genetic manipulation. | Retrospective lineage tracing in human tissues to understand clonal relationships. |

Visualizing a Combined SCLT and scRNA-seq Workflow

The following diagram illustrates how these methodologies are integrated with scRNA-seq to capture both cell state (the transcriptome) and cell history (the lineage barcode) simultaneously.

In this workflow, a heritable lineage marker (e.g., a DNA barcode) is introduced into progenitor cells. As these cells divide and differentiate, the marker is passed on to all progeny. When the tissue is harvested and subjected to scRNA-seq, both the transcriptome and the lineage barcode are sequenced. Bioinformatic analysis then reconstructs a lineage tree, where each branch point represents a fate decision, and each leaf (terminal cell) is annotated with its complete transcriptional profile. This reveals not only which cells are related but also the transcriptional programs that define each branch point in the lineage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Successful scRNA-seq and lineage tracing experiments rely on a suite of specialized tools and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq and Lineage Tracing

| Item / Technology | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | A microfluidics platform that partitions single cells into barcoded droplets (GEMs) for high-throughput scRNA-seq library preparation [1] [4]. | Standardized, scalable workflow for profiling gene expression in thousands of cells from complex tissues. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Cell Lines | Genetically engineered cells where a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) is expressed under the control of a cell-type-specific promoter or responsive element [17] [18]. | Visually identifying and isolating specific cell populations (e.g., STAT-responsive TICs) via FACS prior to scRNA-seq. |

| Cre-loxP System | A site-specific recombination system allowing for inducible, permanent genetic labeling of a cell and its descendants [19]. | Used in multicolor labeling (Brainbow) and polylox barcoding for fate mapping in model organisms. |

| Lentiviral Barcode Libraries | A diverse pool of lentiviral vectors, each containing a unique random DNA sequence, used to "barcode" progenitor cells [18] [19]. | Clonal tracking in transplantation assays, such as studying the output of individual hematopoietic stem cells. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 & Base Editors | Genome editing tools used to create evolving, cumulative mutations in a synthetic genomic barcode locus [19]. | Recording mitotic history with high information capacity to build detailed lineage trees during embryonic development. |

| Cell Ranger / Seurat | Standard bioinformatics software packages for processing, analyzing, and visualizing scRNA-seq data, including clustering and differential expression [4]. | Transforming raw sequencing data into interpretable clusters and marker genes to identify cell types and states. |

The transition from bulk RNA-seq to scRNA-seq represents a paradigm shift in developmental biology and oncology. By moving from a population-average view to a single-cell perspective, researchers can now identify rare but critical cell populations, such as therapy-resistant tumor-initiating cells, and reconstruct the precise lineage trajectories that guide development. While bulk RNA-seq remains a valuable tool for hypothesis generation and large-scale differential expression studies in homogeneous samples, scRNA-seq provides the indispensable resolution needed to deconstruct complex tissues and dynamic processes. The ongoing integration of scRNA-seq with other single-cell modalities and spatial technologies promises to further deepen our understanding of biological systems in health and disease.

The study of the transcriptome has been fundamentally reshaped by two pivotal technological approaches: bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Bulk RNA-seq, a long-standing cornerstone of genomics, provides a population-averaged gene expression profile from a tissue sample composed of numerous cells [4] [20]. In contrast, single-cell RNA sequencing represents a revolutionary advancement that enables researchers to investigate gene expression at the resolution of individual cells, uncovering the cellular heterogeneity that bulk methods inevitably mask [1] [10]. This guide objectively traces the key historical milestones in the evolution of these technologies, comparing their performance, applications, and experimental requirements to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Historical Context and Technological Evolution

The journey into transcriptomics began with bulk sequencing approaches. Following the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies emerged as powerful tools for studying genomic traits and gene expression [20]. For over a decade, bulk RNA-seq served as the primary method for analyzing RNA extracted from populations of cells, revealing differences between sample conditions and providing averaged gene expression readouts [21] [20].

The conceptual and technical shift toward single-cell analysis began approximately two decades ago, pioneered by Norman Iscove who used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for exponential amplification of single-cell cDNAs [10]. James Eberwine subsequently advanced this field by developing a method to amplify cDNAs using T7 RNA polymerase-based transcription in vitro [10]. These early innovations laid the groundwork for what would become a transformative technology in genomics.

The invention and mass production of high-density DNA microarray chips represented another critical milestone, enabling gene expression analysis with unprecedented precision at the individual cell level [10]. This technological progress revealed significant differences in the transcriptomes of genetically identical cells, highlighting the remarkable complexity of cellular behavior and the limitations of population-level analyses that average data across cell populations [10].

In 2013, single-cell RNA sequencing was named "Method of the Year" by Nature Methods, signaling its arrival as a transformative technology [20]. The subsequent development of commercial integrated platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium system triggered rapid adoption of this revolutionized technology in translational and clinical research [4]. This system's core innovation lies in its ability to generate hundreds of thousands of single cell microdroplets (GEMs) on a microfluidics chip, with each GEM containing a single cell, reverse transcription mixes, and a gel bead conjugated with millions of oligo sequences featuring cell-specific barcodes [4].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in RNA Sequencing

| Year/Period | Milestone | Technological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ~2000-2005 | Early single-cell cDNA amplification [10] | Foundation for single-cell analysis using PCR-based methods |

| 2005-2008 | Bulk RNA-seq optimization [20] | Established robust protocols for population-averaged transcriptomics |

| 2013 | scRNA-seq named "Method of the Year" [20] | Recognition of scRNA-seq as a transformative technology |

| 2017-Present | Commercial integrated platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics) [4] | Made scRNA-seq accessible and reproducible for broader research communities |

| 2019-Present | Spatial transcriptomics emergence [4] | Added spatial context to single-cell resolution data |

Technical and Experimental Comparisons

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The experimental workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrate fundamental differences in both philosophy and execution. In bulk RNA-seq, the biological sample is digested to extract total RNA or enriched mRNA, which is then converted to cDNA and processed into a sequencing-ready library [1]. This approach results in a average gene expression profile for the entire sample, analogous to obtaining the average color of a forest without seeing individual trees [1].

In contrast, scRNA-seq requires the generation of viable single cell suspensions from whole samples through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation [1]. This is followed by cell partitioning, where single cells are isolated into individual micro-reaction vessels. In the 10x Genomics platform, this occurs within Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) on a microfluidic chip [1] [4]. Within each GEM, cell lysis occurs, allowing RNA to be captured and barcoded with cell-specific barcodes that ensure analytes from each cell can be traced back to their origin [1]. This barcoding strategy is a cornerstone of modern scRNA-seq, enabling the multiplexing of thousands of cells in a single experiment.

Performance and Capability Comparison

The differing methodologies of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing translate into distinct performance characteristics and experimental capabilities, which determine their appropriate applications in research and drug development.

Table 2: Technical Performance Comparison of Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

| Parameter | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Experimental Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [1] [3] | Individual cell level [1] [3] | scRNA-seq reveals cellular heterogeneity and rare cell types |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited [3] | High [3] | Bulk masks rare populations; scRNA-seq identifies them |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited [3] | Possible [3] | scRNA-seq can identify rare stem cells or circulating tumor cells |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample [3] | Lower per cell [3] | Bulk detects more genes per sample; scRNA-seq has sparser data |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300/sample) [3] | Higher (~$500-$2000/sample) [3] | Bulk more suitable for large cohort studies |

| Data Complexity | Lower, more straightforward [1] [3] | Higher, requires specialized analysis [1] [3] | scRNA-seq demands advanced computational resources and expertise |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher [3] | Lower [3] | scRNA-seq can work with limited material (e.g., 10 pg total RNA) |

| Splicing Analysis | More comprehensive [3] | Limited [3] | Bulk better for detecting alternative splicing events |

Applications and Experimental Outcomes

Distinct yet Complementary Biological Applications

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing is primarily determined by the research question, with each technology excelling in distinct application domains.

Bulk RNA-seq applications include:

- Differential gene expression analysis: Comparing gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions (disease vs. healthy, treated vs. control) to identify upregulated or downregulated genes [1]

- Biomarker discovery: Identifying RNA-based biomarkers and molecular signatures for disease diagnosis, prognosis, or stratification [1] [4]

- Tissue or population-level transcriptomics: Obtaining global expression profiles from whole tissues, organs, or bulk-sorted cell populations, particularly useful for large cohort studies or biobank projects [1]

- Gene fusion detection: Discovering novel gene fusions, with recent computational advances like DEEPEST algorithm minimizing false positives and improving detection sensitivity [4]

Single-cell RNA-seq applications include:

- Characterizing heterogeneous cell populations: Identifying novel cell types, cell states, and rare cell types within complex tissues [1] [4]

- Reconstructing developmental hierarchies: Tracing cellular differentiation pathways and lineage relationships during development or disease progression [1]

- Dissecting tumor heterogeneity: Revealing diverse transcriptional programs within tumors that provide plasticity to adapt to various environments and promote treatment resistance [4]

- Analyzing tumor microenvironment: Characterizing the diversity of immune and stromal cell populations within tumors and their roles in cancer progression and therapy resistance [4] [22]

Case Study: Integrated Analysis in Lung Adenocarcinoma

A 2025 study on lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) exemplifies the powerful synergy between bulk and single-cell approaches [22]. Researchers first used scRNA-seq to identify seven distinct cell clusters within tumor samples, with epithelial cell cluster 1 (Epi_C1) showing the highest stemness potential based on CytoTRACE analysis [22]. They then leveraged bulk RNA-seq data from TCGA to construct a prognostic tumor stem cell marker signature (TSCMS) model incorporating 49 tumor stemness-related genes [22]. This integrated approach demonstrated that high-risk patients exhibited lower immune scores, increased tumor purity, and significant differences in chemotherapy sensitivity, while also identifying TAF10 as a potential therapeutic target linked to stemness and poor prognosis [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of RNA sequencing experiments requires careful selection of reagents and materials optimized for each methodology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Bulk RNA-seq Specifics | Single-Cell RNA-seq Specifics |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Extract high-quality RNA from samples | Focus on yield and purity; RIN >6 acceptable [20] | Critical for viable single cells; emphasis on preventing degradation |

| Poly(T) Oligos | Enrich for polyadenylated RNA | Standard mRNA enrichment [20] | Coated on gel beads for cell-specific barcoding [4] |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA | Optional depending on study goals [20] | Often used to improve detection of non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| Cell Barcoding Beads | Tag molecules with cell-specific barcodes | Not required | Gel Beads with unique 10x barcodes essential for partitioning [1] |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare sequencing-ready libraries | Standard NGS library preparation | Specialized kits with UMIs for unique transcript counting |

| Microfluidic Chips | Partition individual cells | Not used | Essential for single-cell isolation in platforms like 10x Chromium [1] |

| Viability Stains | Assess cell integrity and viability | Less critical | Critical for ensuring high-quality single cell suspensions |

Data Analysis and Computational Considerations

The data analysis workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing differ significantly in complexity and methodology. Bulk RNA-seq analysis typically involves quality control of raw data, read alignment using tools like STAR or TopHat, transcriptome reconstruction, and expression quantification [21]. The resulting data matrix is relatively straightforward, with genes as rows and samples as columns.

In contrast, scRNA-seq data analysis presents unique computational challenges due to the high dimensionality, technical noise, and sparsity of the data [21] [3]. The initial data matrix contains genes as rows and thousands of individual cells as columns. Analysis requires specialized pipelines for:

- Quality control: Filtering cells with high mitochondrial content or few detected genes [21] [22]

- Normalization and batch effect correction: Addressing technical variability between cells and experiments [13]

- Dimensionality reduction: Using PCA, UMAP, or t-SNE to visualize cell populations in two dimensions [22] [13]

- Cell clustering and marker identification: Defining cell populations based on transcriptional similarity [22]

- Trajectory inference: Reconstructing developmental pathways using tools like Monocle3 [13]

The high computational resources and specialized expertise required for scRNA-seq analysis represent a significant consideration for research planning [1] [3].

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The evolution of transcriptomics continues with the emergence of spatial transcriptomics, which preserves the spatial context of RNA expression within tissues [4] [10]. This technology represents a natural progression from bulk sequencing (which loses cellular resolution) to single-cell sequencing (which loses spatial context) to spatial methods that provide both single-cell resolution and spatial information [10].

Other emerging trends include:

- Multi-omics integration: Combining scRNA-seq with other single-cell modalities like chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq) and protein profiling (CITE-seq) [3] [13]

- Machine learning applications: Leveraging deep learning for data denoising, dimensionality reduction, and trajectory inference [23]

- Cost reduction initiatives: Development of more affordable scRNA-seq platforms and reagents to increase accessibility [1] [3]

- Targeted scRNA-seq approaches: Focusing sequencing resources on predefined gene sets for superior sensitivity and quantitative accuracy in translational settings [15]

The revolution from bulk to single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our approach to studying transcriptomes. Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for population-level studies, differential expression analysis in homogeneous samples, and large cohort studies where cellular heterogeneity is not the primary focus [1] [3] [23]. In contrast, scRNA-seq provides unprecedented resolution for dissecting cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell populations, reconstructing developmental trajectories, and understanding complex tissue microenvironments [1] [4] [10].

The most impactful modern research often integrates both technologies, using their complementary strengths to generate comprehensive biological insights [22] [13]. As the field continues to evolve with spatial transcriptomics and multi-omics integration, this methodological synergy will likely drive the next wave of discoveries in basic research and therapeutic development.

For researchers planning transcriptomics studies, the decision between bulk and single-cell approaches should be guided by specific research questions, budget constraints, available expertise, and the biological complexity of the system under investigation.

In developmental biology, understanding the precise transcriptional programs that guide cell fate decisions is paramount. For over a decade, bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) has been the conventional approach for studying gene expression, providing a population-averaged view of the transcriptome across thousands to millions of cells [1] [20]. This method yields a composite gene expression profile that represents the collective RNA from all cells in a sample, much like viewing a forest from a distance without distinguishing individual trees. In contrast, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a revolutionary technology that enables researchers to measure gene expression at the resolution of individual cells, revealing the unique transcriptional identity of each cellular unit within a complex biological system [1] [4]. This fundamental difference in resolution—averaged expression versus cell-specific transcriptomes—has profound implications for how we study developmental processes, tumor heterogeneity, and cellular responses to therapeutic interventions [24] [4].

The distinction between these approaches extends beyond technical methodology to their very philosophical underpinnings. Bulk RNA-seq operates on the principle of collective measurement, where the signal represents the mean expression across all cells, potentially masking critical cell-to-cell variations. scRNA-seq, however, embraces cellular heterogeneity as a fundamental biological reality, recognizing that individual cells within a population may exist in distinct states, perform different functions, and respond uniquely to environmental cues [25]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these technologies, with a specific focus on their applications in developmental studies research, to help scientists select the appropriate tool for their specific research questions.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Bulk RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

The bulk RNA-seq workflow begins with tissue collection or cell culture, followed by RNA extraction from the entire sample population [1] [20]. Key steps include:

- Sample Lysis and RNA Extraction: The biological sample is digested to extract total RNA, which may include enrichment for mRNA via poly(A) selection or depletion of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to improve sequencing efficiency [1].

- Library Preparation: Extracted RNA is converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) through reverse transcription. The cDNA undergoes fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification to create a sequencing-ready library. Library preparation strategies vary depending on the RNA species of interest—mRNA-only libraries typically use poly(T) enrichment, while whole transcriptome approaches employ rRNA depletion to capture non-coding RNAs and other RNA species [20] [4].

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Libraries are sequenced using next-generation sequencing platforms, followed by alignment to a reference genome and quantification of gene expression levels. The final output represents the average expression level for each gene across all cells in the original sample [1] [21].

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

scRNA-seq introduces several critical steps to preserve and analyze cell-specific information [1] [26]:

- Single-Cell Suspension Preparation: Tissues are dissociated into viable single-cell suspensions using enzymatic or mechanical methods, with careful optimization to minimize stress-induced transcriptional artifacts and preserve cell viability [26].

- Single-Cell Isolation and Barcoding: Individual cells are partitioned into nanoliter-scale reactions using microfluidic devices (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) or plate-based systems. Each cell is lysed, and the released mRNA transcripts are tagged with cell-specific barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during reverse transcription. These barcodes enable bioinformatic tracing of each transcript back to its cell of origin, while UMIs facilitate accurate transcript quantification by correcting for amplification bias [1] [4].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Barcoded cDNA from all cells is pooled into a single library for efficient sequencing, despite originating from thousands of individual cells [25].

- Bioinformatic Processing and Analysis: Sequencing data undergoes demultiplexing (assigning reads to individual cells based on barcodes), quality control, normalization, and downstream analysis such as clustering, trajectory inference, and differential expression analysis at the single-cell level [24].

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between these two approaches:

Comparative Analysis of Output Data

Nature of Transcriptome Information

The fundamental output differences between these technologies create distinct advantages and limitations for each approach:

Bulk RNA-seq Output Characteristics:

- Averaged Expression Signals: Gene expression measurements represent the mean across all cells in the sample, weighted by abundance and expression level of each cell type [1] [20].

- Population-Level Insights: Well-suited for identifying consensus expression patterns that characterize a tissue or condition [1].

- Masked Heterogeneity: Cellular subpopulations and rare cell types (<5-10% of total population) typically fail to detectably influence the averaged profile [4].

- Higher Depth per Gene: Sequencing depth is distributed across the transcriptome without need for cell barcoding, often enabling better detection of lowly-expressed genes within the population context [1].

scRNA-seq Output Characteristics:

- Cell-Specific Resolution: Each measurement is associated with a specific cell via barcoding, preserving individual transcriptomic identities [1] [4].

- Heterogeneity Mapping: Enables identification of distinct cell types, states, and continuous transitions within populations [24] [25].

- Rare Cell Detection: Can identify and characterize cell populations representing as little as 0.1-1% of the total sample [4] [25].

- Sparse Data: Each individual cell captures only 10-50% of its transcriptome due to limited RNA capture efficiency, creating data sparsity that requires specialized statistical approaches [24].

Quantitative Comparison of Output Data

The table below summarizes key differences in the data output and analytical capabilities:

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Individual cells |

| Heterogeneity Analysis | Indirect inference | Direct measurement |

| Rare Cell Detection | Limited (>5% abundance) | Excellent (0.1-1% abundance) |

| Transcriptome Coverage | ~40-70% of transcriptome per sample | ~10-50% of transcriptome per cell |

| Data Structure | Dense matrix (genes × samples) | Sparse matrix (genes × cells) |

| Key Deliverables | Differential expression, Pathway analysis | Cell clustering, Trajectory inference, Rare population identification |

| Ideal Applications | Biomarker discovery, Condition comparisons, Transcriptome annotation | Cell atlas construction, Developmental tracing, Tumor heterogeneity, Drug response mechanisms |

Experimental Evidence from Comparative Studies

Recent investigations have directly compared outputs from both technologies when applied to the same biological systems. A 2025 study of human pancreatic islets from the same donors demonstrated that while both scRNA-seq and single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) identified the same major cell types, they revealed significant differences in predicted cell type proportions [27]. This highlights how the choice of method can influence biological interpretations, particularly when studying complex tissues with nuanced cellular distributions.

In cancer research, integrated approaches have proven particularly powerful. A 2024 study on B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) leveraged both technologies to identify developmental states driving chemotherapy resistance [1]. While bulk RNA-seq provided a global view of treatment-induced expression changes, scRNA-seq pinpointed rare resistant subpopulations that would have been masked in bulk averages. Similarly, in ovarian cancer, researchers combined scRNA-seq analysis of platinum-resistant cancer cells with bulk RNA-seq data from larger cohorts to develop a machine learning model that accurately predicted patient response to platinum-based chemotherapy [28].

Applications in Developmental Studies

Developmental biology represents a particularly compelling application for scRNA-seq, as it fundamentally involves understanding how a relatively homogeneous population of progenitor cells differentiates into diverse, specialized cell types.

Lineage Tracing and Developmental Trajectories

scRNA-seq enables reconstruction of developmental hierarchies and lineage relationships by capturing transient intermediate states that are impossible to resolve with bulk approaches [1] [24]. Computational methods like pseudotime analysis order individual cells along differentiation trajectories based on transcriptional similarity, effectively reconstructing the temporal sequence of developmental events from snapshot data [24]. This approach has been successfully applied to model cardiovascular lineage segregation in mice [26], embryonic development [25], and differentiation processes in various tissues [24].

In contrast, bulk RNA-seq of developing tissues typically identifies only the most abundant cell types and may completely miss critical transitional states that are short-lived or numerically rare. While bulk approaches can track gross expression changes across developmental timepoints, they cannot resolve whether these changes represent graded transitions across the population or the emergence of distinct subpopulations.

Cellular Heterogeneity in Developing Systems

The following diagram illustrates how each technology captures cellular heterogeneity during development:

Case Study: Cardiovascular Development

A compelling example comes from cardiac development research, where scRNA-seq has redefined understanding of heart formation. Traditional bulk approaches had identified major transcriptional changes between developmental stages but failed to resolve the precise lineage relationships between different cardiac cell types. scRNA-seq applied to developing mouse hearts revealed previously uncharacterized progenitor populations and delineated the transcriptional programs guiding specialization into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and valve interstitial cells [20]. These findings have profound implications for understanding congenital heart diseases and developing regenerative therapies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate reagents and platforms is crucial for successful RNA-seq experiments. The following table outlines key solutions for implementing each technology:

| Product Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq Library Prep | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, NEBNext Ultra II RNA | Poly(A) enrichment, cDNA synthesis, library construction for population-level sequencing |

| Single-Cell Isolation | 10x Genomics Chromium X, BD Rhapsody, Fluidigm C1 | Microfluidic partitioning of single cells with barcoded beads for high-throughput capture |

| Single-Cell Library Prep | 10x Genomics 3' Gene Expression, SMART-Seq v4 | Cell barcoding, UMI incorporation, cDNA amplification from single cells |

| Sample Preservation | DNA/RNA Shield, RNAlater | Stabilizes RNA in intact tissues or cell suspensions before processing |

| Cell Type Enrichment | MACS Cell Separation, FACS | Isolation of specific cell populations prior to sequencing using surface markers |

| Single-Nuclei RNA-seq | 10x Genomics Nuclei Isolation Kits | Enables sequencing from frozen tissues or difficult-to-dissociate samples |

| Data Analysis Software | Cell Ranger, Seurat, Scanpy, Partek Flow | Processing, normalization, clustering, and visualization of single-cell data |

The choice between bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq should be guided by specific research questions and experimental constraints. Bulk RNA-seq remains the preferred method for hypothesis-generating exploration of expression differences between conditions, identification of biomarker signatures, and studies with limited budgets or sample material that precludes single-cell analysis [1] [20]. Its advantages include lower cost per sample, simpler data analysis, and established analytical frameworks.

scRNA-seq is indispensable when investigating cellular heterogeneity, developmental trajectories, rare cell populations, or complex tissues with diverse cellular composition [24] [4]. Despite higher per-sample costs and greater analytical complexity, its ability to resolve biological complexity at the fundamental unit of life—the individual cell—makes it increasingly essential for developmental biology, cancer research, and immunology [1] [25].

For comprehensive developmental studies, a synergistic approach often yields the deepest insights: using scRNA-seq to map cellular heterogeneity and identify key cell states, followed by bulk RNA-seq to validate findings across larger sample cohorts or experimental conditions. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, becoming more accessible and cost-effective, they will undoubtedly reshape our fundamental understanding of developmental processes and provide new avenues for therapeutic intervention in developmental disorders.

Methodological Deep Dive: Applications in Developmental Systems

The fundamental difference between bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) lies in their resolution. Bulk RNA-seq provides an average gene expression profile across a population of cells, while scRNA-seq reveals the transcriptome of individual cells, capturing cellular heterogeneity that is masked in bulk approaches [1] [4] [16]. This comparison guide will objectively examine the workflows of both technologies, from initial sample preparation to final data generation, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting the appropriate method for their developmental studies.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Cell Isolation

The initial steps of sample preparation mark the first major divergence between the two techniques, with scRNA-seq requiring significantly more complex processing to handle individual cells.

Bulk RNA-seq Workflow: The process begins with the collection of tissue or a cell population. The entire sample is processed to extract total RNA, which could involve enrichment for mRNA or depletion of ribosomal RNA. This pooled RNA is then converted to cDNA and prepared into a sequencing library, ultimately providing a composite gene expression profile for the entire sample [1].

scRNA-seq Workflow: This method requires the generation of a viable single-cell suspension from the starting material through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation. This is followed by critical cell counting and quality control steps to ensure appropriate cell concentration and viability, and to remove cell debris and clumps [1]. The method of single-cell isolation varies by platform:

- Droplet-based technologies (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium, Drop-seq, inDrop) use microfluidic systems to encapsulate individual cells in nanoliter droplets along with barcoded beads [29] [30].

- Plate-based methods (e.g., SMART-seq2, Fluidigm C1) isolate cells into individual wells via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microfluidic chips [29] [30].

- Combinatorial indexing methods perform barcoding in plates without physical cell isolation [31].

Table: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Platforms and Methods

| Platform/Method | Isolation Strategy | Cell Throughput | UMI Usage | Transcript Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Microdroplets | High (thousands) | Yes | 3' or 5' end |

| Drop-seq | Microdroplets | High | Yes | 3' end |

| Smart-seq2 | FACS | Low | No | Full-length |

| Fluidigm C1 | Microfluidic | Medium | No | Full-length |

| SEQ-well | Nanowells | High | Yes | 3' end |

| MARS-seq | FACS | Low | Yes | 3' end |

Library Preparation and Sequencing

The core technological differences become especially apparent during library preparation, where scRNA-seq employs sophisticated barcoding strategies to track individual cells.

Bulk RNA-seq Library Prep: After RNA extraction, the entire pool of RNA is converted to cDNA. Libraries are prepared directly from this material without the need for cell-specific labeling. The resulting data represents the averaged transcript abundance across all input cells [1].

scRNA-seq Library Prep: A critical distinction is the incorporation of cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). In droplet-based systems like 10x Genomics, single cells are partitioned into gel beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) containing barcoded oligos. Each GEM delivers a unique cell barcode to all transcripts from a single cell, and UMIs label individual mRNA molecules to correct for amplification bias [1] [4]. After reverse transcription, barcoded cDNA from all cells is pooled for library preparation and sequencing [1].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow differences between these two approaches:

Data Output and Analytical Approaches

Data Characteristics and Processing

The raw data output from sequencing requires substantially different computational processing pipelines, particularly in the initial stages where scRNA-seq data must be demultiplexed to assign reads to individual cells.

Bulk RNA-seq Data Processing: After sequencing, reads are typically aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using tools like STAR, HISAT, or TopHat2. Gene expression is then quantified as read counts, which are normalized and analyzed for differential expression between conditions [29] [32].

scRNA-seq Data Processing: The analysis begins with demultiplexing—grouping reads by their cell barcodes and collapsing PCR duplicates using UMIs. This generates a gene expression matrix (cells × genes) where each value represents the UMI count for a gene in a cell [29] [31]. Subsequent quality control is more complex, requiring the removal of:

- Empty droplets (barcodes associated with ambient RNA)

- Low-quality cells (with high mitochondrial read percentage)

- Doublets (multiple cells with the same barcode)

- Background RNA from compromised cells [31]

Following QC, data undergoes normalization to address technical variability, then log-transformation to stabilize variance. Dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA and UMAP are applied before clustering cells and identifying marker genes [31].

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Technical Parameters

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-seq | scRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Tissue or cell population | Single-cell suspension |

| Cells Analyzed | Population (millions) | 100 - 80,000 cells |

| Resolution | Average expression | Single-cell level |

| Key Metrics | Read depth (~50M reads/sample) | Cells sequenced, reads/cell, genes/cell |

| Data Structure | Gene expression matrix (samples × genes) | 3D expression matrix (cells × genes × UMIs) |

| Technical Noise | Lower, mainly from extraction and library prep | Higher, includes capture efficiency, amplification bias |

| Data Sparsity | Low | High (excess zeros) |

| Cost per Sample | Lower | Higher (reagents, sequencing, analysis) |

| Cell Type Information | Requires deconvolution | Directly observed |

| Rare Cell Detection | Masked by majority population | Possible with sufficient sequencing depth |

Analytical Output and Biological Insights

The analytical outputs and biological applications of these two methods differ substantially, with each providing unique and often complementary insights.

Bulk RNA-seq Applications:

- Differential gene expression analysis between conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy, treated vs. control) [1]

- Biomarker discovery for diagnosis, prognosis, or stratification [1] [4]

- Transcriptome annotation including novel transcripts, isoforms, and gene fusions [1] [16]

- Pathway and network analysis to understand coordinated gene expression changes [32]

scRNA-seq Applications:

- Cellular heterogeneity characterization and novel cell type identification [1] [4]

- Developmental trajectories and lineage reconstruction [1]

- Tumor microenvironment characterization at single-cell resolution [4] [16]

- Rare cell population detection (e.g., stem cells, circulating tumor cells) [4]

- Gene regulatory network inference in specific cell types [32]

The diagram below illustrates the key stages and decision points in the computational analysis of scRNA-seq data:

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Considerations

Successful implementation of either RNA-seq technology requires careful selection of reagents and consideration of experimental parameters. The following toolkit outlines essential materials and their functions.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for RNA-seq Workflows

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Microfluidic partitioning with barcoded gel beads | High-throughput scRNA-seq |

| SMARTer Ultra Low RNA Kit | cDNA synthesis from low-input RNA | Plate-based scRNA-seq (e.g., Fluidigm C1) |

| UMI Oligos | Unique molecular identifiers for transcript counting | scRNA-seq for quantification accuracy |

| Cell Barcodes | Nucleic acid sequences to label individual cells | Tracking cell origin in scRNA-seq |

| ERCC Spike-in RNA | Synthetic RNA controls for technical variance calibration | Both bulk and scRNA-seq normalization |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep | Library preparation for Illumina sequencing | Both bulk and scRNA-seq |

| Live/Dead Cell Stains | Viability assessment (e.g., Calcein AM/EthD-1) | scRNA-seq sample QC |

| STAR Aligner | Spliced transcript alignment to reference genome | Both bulk and scRNA-seq read mapping |

| Cell Ranger | Processing scRNA-seq data from FASTQ to count matrix | 10x Genomics platform data |

| Seurat | R toolkit for scRNA-seq data analysis | scRNA-seq clustering and visualization |

| UMI-tools | Network-based error correction for UMI deduplication | scRNA-seq data processing |

Practical Considerations for Experimental Design

Sample Quality Requirements: scRNA-seq demands high cell viability (>90%) and effective dissociation into single cells without activation of stress responses, which can significantly alter transcriptional profiles [1] [30]. Bulk RNA-seq is more forgiving of sample quality.

Cost Considerations: While bulk RNA-seq has lower per-sample costs, scRNA-seq provides significantly more biological information per experiment. Recent technological advances like the 10x Genomics GEM-X Flex assay are reducing the cost barrier for single-cell studies [1].

Technical Replication: Bulk RNA-seq typically requires multiple biological replicates for statistical power. In scRNA-seq, thousands of "mini-replicates" (individual cells) are captured in a single run, though technical replication across runs remains important for batch effect control [1] [31].

Cell Type Sensitivity: scRNA-seq can detect rare cell populations comprising as little as 0.1% of a sample, while such populations would be masked in bulk sequencing [1] [4]. However, some cell types (e.g., neutrophils) remain challenging for scRNA-seq due to low RNA content and high RNase levels [33].

Bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq offer complementary approaches to transcriptome analysis with fundamentally different workflows from sample preparation through data generation. Bulk RNA-seq remains a cost-effective method for population-level differential expression studies, while scRNA-seq provides unprecedented resolution for deconstructing cellular heterogeneity, developmental trajectories, and complex tissue environments. The choice between these technologies should be guided by research questions, budget constraints, and sample availability, with increasing opportunities to leverage both approaches in tandem for comprehensive biological insights. As evidenced by studies like Huang et al.'s 2024 investigation of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, integrating both bulk and single-cell approaches can powerfully synergize to reveal novel biological mechanisms and therapeutic targets [1].

Understanding cellular heterogeneity is a fundamental challenge in biological research. While conventional bulk analysis methods provide an average readout from a population of cells, they inevitably mask the unique characteristics of individual cells [34]. The same cell line or tissue can present different genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes during cell division and differentiation [34]. This is particularly critical when studying complex systems like a developing embryo, brain tissue, or a tumor microenvironment, where intricate structures consist of numerous, spatially separated cell types [34]. The isolation of distinct cell types is, therefore, an essential precursor to deeper analysis, enabling breakthroughs in diagnostics, biotechnology, and biomedical applications.

The choice of isolation technique directly influences the success of downstream applications, most notably single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). scRNA-seq has revolutionized genomic research by allowing scientists to profile gene expression profiles of individual cells, dissecting heterogeneity that is completely inaccessible to bulk RNA-seq [1] [20] [4]. This high-resolution view is indispensable for discovering rare cell types, characterizing novel cell states, and reconstructing developmental lineages [1]. The transition from a bulk-level "view of a forest" to a single-cell "view of every tree" begins with the effective and efficient isolation of single cells, making the mastery of these techniques a cornerstone of modern developmental studies [1].

Technical Comparison of Single-Cell Isolation Techniques

The performance of cell isolation technology is typically characterized by key parameters: throughput (how many cells can be isolated in a certain time), purity (the fraction of target cells collected after separation), and recovery (the fraction of initially available target cells obtained) [34]. The following sections and tables provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of four major isolation methods.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

Experimental Protocol: A cell suspension is prepared, and target cells are labeled with fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that recognize specific surface markers. The suspension is hydrodynamically focused into a stream of single cells that passes through a laser beam. Fluorescence detectors identify cells based on their light scatter and fluorescence characteristics. Immediately after detection, the stream is vibrated to break into droplets. Droplets containing a cell of interest are electrically charged and deflected into collection tubes using an electrostatic field [34] [35] [36].

Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS)

Experimental Protocol: Target cells are labeled with superparamagnetic beads conjugated to specific antibodies, enzymes, or lectins. The cell suspension is then placed in a strong external magnetic field, typically by passing it through a column placed within a magnet. Cells bound to magnetic beads are retained within the column, while unlabeled cells are washed through. After removing the column from the magnetic field, the retained target cells are eluted in a buffer solution [34] [35]. The technique can be used in positive selection (isolating labeled cells) or negative selection (depleting labeled cells to isolate the unlabeled population) [34].

Microfluidics

Experimental Protocol: Microfluidic techniques for cell isolation are diverse. For cell-affinity chromatography, channels in a microfluidic chip are modified with specific antibodies. As the dissociated cell sample flows through these channels, cells expressing the target surface antigens bind and are immobilized. Non-target cells are washed away, and the bound cells are later released for analysis [35] [36]. Alternatively, label-free methods exploit intrinsic physical properties of cells—such as size, density, deformability, and electrical polarizability—to sort cells using mechanisms like deterministic lateral displacement (DLD) or dielectrophoresis [35]. A prominent application is in droplet-based scRNA-seq platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium), where a microfluidic "chip" partitions single cells into nanoliter-scale droplets (GEMs) along with barcoding beads and reagents [1] [4].