Spatial Multiomics: Mastering ISH and Immunohistochemistry Co-Localization for Precision Biomarker Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) co-localization studies, a cornerstone of spatial biology.

Spatial Multiomics: Mastering ISH and Immunohistochemistry Co-Localization for Precision Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) co-localization studies, a cornerstone of spatial biology. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodological workflows, critical optimization strategies, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current techniques—from automated protease-free assays to super-resolution expansion microscopy—this resource empowers scientists to precisely visualize nucleic acids and proteins within their morphological context, thereby accelerating biomarker development, therapeutic efficacy assessments, and mechanistic action studies in oncology and beyond.

The Spatial Biology Landscape: Core Principles of ISH and IHC Co-Localization

The spatial relationship between RNA, DNA, and proteins within the cellular architecture provides critical insights into gene regulation, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development. Co-localization studies aim to precisely determine where these biomolecules interact within their morphological context, revealing functional relationships that are obscured in bulk analyses. This field has gained significant momentum with advancements in spatial biology technologies and computational frameworks that enable researchers to move beyond simple pairwise interactions to complex multi-molecular relationships. The integration of in situ hybridization (ISH) with immunohistochemistry (IHC) has emerged as a powerful approach for visualizing multiple molecular species within intact tissues and cells, preserving the architectural context essential for understanding biological complexity. This guide compares the leading methodological approaches for studying these interactions, evaluating their technical capabilities, applications, and limitations to inform research and drug development efforts.

Methodological Approaches for Co-Localization Analysis

Researchers have developed several sophisticated methods to tackle the challenges of visualizing and quantifying RNA-DNA-protein interactions. The table below compares three advanced approaches for co-localization studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Co-Localization Methodological Approaches

| Method | Core Principle | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential IHC & Image Registration [1] | Sequential staining of adjacent tissue sections with image alignment | Cellular scale (a few cells) | Biomarker colocalization in FFPE tissue, protein-protein interaction studies | Medium |

| RNA Fluorescence Three-Hybrid (rF3H) [2] | Anchoring RNA to specific subcellular structures to detect recruited proteins | Subcellular | RNA-protein interaction dynamics in living cells, characterization of RBPs | High |

| Interaction Triad Analysis [3] | Computational filtering of pairwise interaction data (RNA-DNA, protein-DNA, RNA-protein) | Genomic locus level | Identification of functional RNA-protein-DNA complexes, chromatin regulation studies | Very High (computational) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Combined ISH and IHC on Archival Tissues

This protocol enables simultaneous detection of RNA and protein within the same tissue section, allowing precise compartmentalization of signals between tumor epithelia and stroma [4].

- Tissue Preparation: Cut 3 µm sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks. Deparaffinize in xylene and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series.

- Antigen Retrieval & Permeabilization: Incubate sections with 15 μg/mL Proteinase K at 37°C for 10 minutes. Optimal concentration and time should be determined by titration.

- In Situ Hybridization:

- Pre-hybridize with ISH buffer for 30 minutes.

- Hybridize with DIG-labeled miR probes (e.g., miR-204-5p) at 53°C for 2 hours.

- Perform stringent washes with SSC buffer at the corresponding hybridization temperature.

- Immunohistochemistry:

- Block with 2% sheep serum and 1% BSA.

- Incubate with primary antibody against epithelial markers (e.g., pan-cytokeratin) followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Dual Detection:

- Detect miR signals using alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-DIG antibody with NBT/BCIP chromogen (purple/black precipitate).

- Detect protein signals using DAB chromogen (brown precipitate).

- Quantification: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ or Aperio ImageScope) to quantify miR expression specifically within the stromal compartment defined by the absence of pan-cytokeratin staining.

RNA Fluorescence Three-Hybrid (rF3H) Method

This live-cell method detects RNA-protein interactions by visualizing protein recruitment to artificially anchored RNAs [2].

- Plasmid Design:

- Construct an RNA trap plasmid (e.g., pMCP-EGFP-LacI) encoding a fusion protein with an RNA-binding module (e.g., MS2 coat protein), a fluorescent protein (e.g., EGFP), and a localization signal (e.g., LacI for lacO genomic sites).

- Engineer the RNA of interest (ROI) to include recognition sequences (e.g., MS2 stem-loops).

- Tag the putative RNA-binding protein (RBP) with a fluorescent marker (e.g., mCherry).

- Cell Culture & Transfection:

- Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., BHK cells with genomic lacO integration or HeLa cells).

- Co-transfect the three plasmids (RNA trap, ROI, RBP) in a mass ratio of 1:1:1 using lipid-based transfection reagents.

- Live-Cell Imaging & Analysis:

- Image cells 24-48 hours post-transfection using confocal microscopy.

- Detect co-localization by the enrichment of the RBP-mCherry signal at the specific subcellular structures where the RNA trap-EGFP is anchored.

- Quantify fluorescence intensity at these anchored structures compared to the nucleoplasm.

Interaction Triad Analysis

This computational approach integrates heterogeneous omics datasets to identify functional three-component interactions [3].

- Data Collection:

- RNA-DNA contacts (RD-contacts): From all-to-all methods like RADICL-seq or GRID-seq.

- Protein-DNA contacts (PD-contacts): From ChIP-seq experiments (e.g., from ENCODE, ReMap).

- RNA-protein contacts (PR-contacts): From RIP-seq, fRIP-seq, or eCLIP experiments.

- Data Processing:

- Process ChIP-seq data with MACS2 peak caller (q-value < 0.05).

- Map RNA-protein immunoprecipitation data to the genome using HISAT2 and call peaks using Piranha.

- Triad Construction:

- Intersect the three pairwise interaction datasets.

- Define a triad when an RNA (R), a protein (P), and a DNA locus (D) are connected by significant R-D, P-D, and R-P interactions.

- Statistical Validation:

- Assess significance by comparing against background models of random pairwise interactions.

- Filter triads further using functional annotations (e.g., ChromHMM chromatin states).

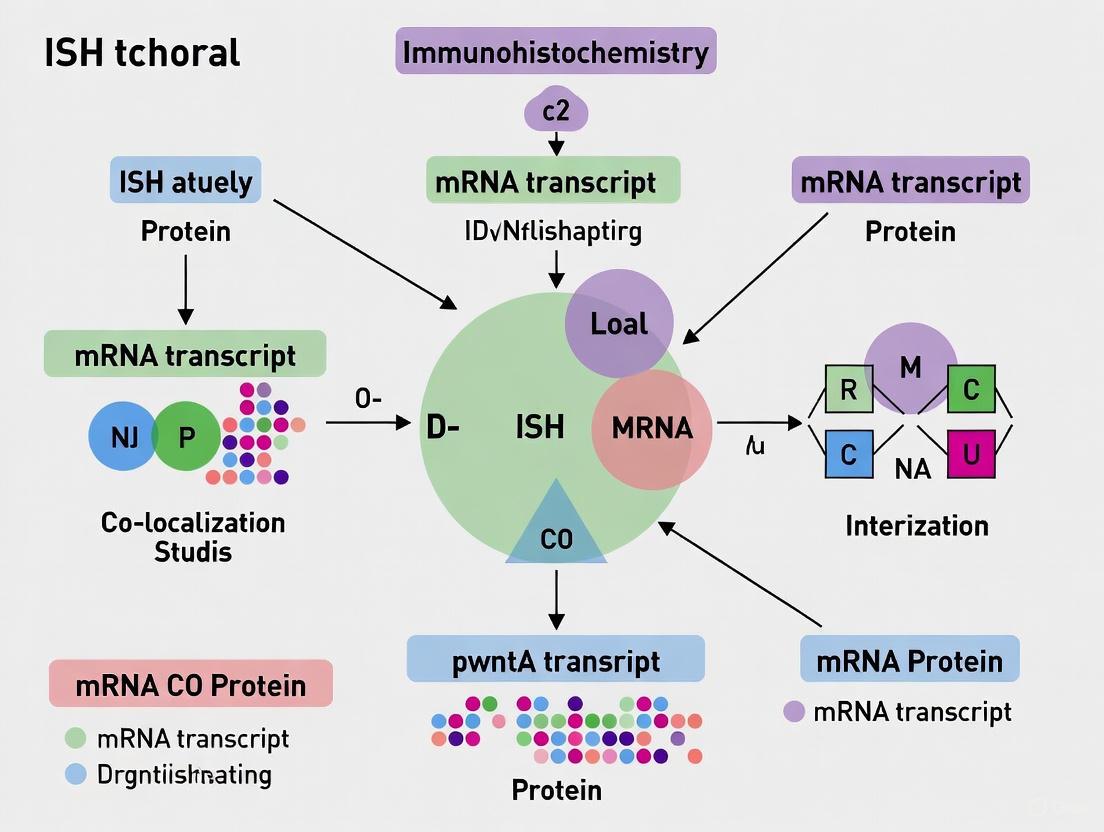

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful co-localization experiments require carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for implementing these methodologies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Co-Localization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissues | Preserves tissue morphology and biomolecule integrity for archival studies | Combined ISH-IHC on patient cohorts [4] |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes | Enhanced sensitivity and specificity for RNA detection in ISH | Detection of microRNAs (e.g., miR-204) in tumor stroma [4] |

| Digoxigenin (DIG)-Labeled Probes | Non-radioactive label for nucleic acid detection | ISH with anti-DIG antibodies and colorimetric detection [5] [4] |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme for antigen retrieval and tissue permeabilization | Unmasking target epitopes and RNA in FFPE sections [5] [4] |

| Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) Buffer | Controls stringency of hybridization through ion concentration | Post-hybridization washes to remove non-specific probe binding [5] [4] |

| MS2 Stem-Loop System | RNA tagging and trapping in live cells | rF3H method for visualizing RNA-protein interactions [2] |

| NBT/BCIP Substrate | Chromogenic substrate for alkaline phosphatase | Colorimetric detection (purple/black) of RNA in ISH [4] |

| DAB Substrate | Chromogenic substrate for horseradish peroxidase | Colorimetric detection (brown) of proteins in IHC [4] |

| Image Analysis Software (ImageJ, Aperio) | Digital quantification of signal intensity and localization | Objective measurement of expression in specific tissue compartments [4] |

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

Understanding the capabilities and limitations of each method is crucial for experimental design. The table below summarizes key performance metrics based on published data.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Co-Localization Methods

| Performance Metric | Sequential IHC & Registration | Combined ISH-IHC | rF3H Method | Interaction Triads |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registration Accuracy | Cellular scale (a few cells) [1] | Cellular/subcellular [4] | Subcellular [2] | Locus level [3] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited by serial sections | 2-3 targets simultaneously [4] | Multiple targets with different colors [2] | Genome-wide [3] |

| Throughput | Medium | Medium | Medium to High | Very High |

| Tissue Context Preservation | High (archival tissues) [1] | High (archival tissues) [4] | Limited (cell cultures) | Computational inference |

| Live-Cell Capability | No | No | Yes [2] | No |

| Noise Reduction Efficiency | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Significant vs pairwise data [3] |

The methodological landscape for co-localization studies has expanded significantly, offering researchers multiple pathways to investigate RNA-DNA-protein interactions within morphological context. Combined ISH-IHC provides a robust, accessible approach for archival tissues with direct clinical relevance. The rF3H method enables dynamic studies of RNA-protein interactions in living cells with high specificity. Interaction triad analysis offers a powerful computational framework for extracting functional insights from noisy genome-wide datasets. The choice of method depends critically on the research question, required resolution, tissue availability, and technical capabilities. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will further illuminate the spatial organization of molecular interactions, advancing both basic research and drug development efforts.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stands as a cornerstone technique in life science research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the precise detection and localization of specific antigens within tissue samples. By leveraging highly specific antibody-epitope interactions, IHC allows researchers and pathologists to visualize the distribution and abundance of proteins in their proper histological context, providing invaluable insights into cellular function, disease mechanisms, and treatment responses [6] [7]. The technique has evolved significantly since its inception, with modern IHC offering both chromogenic and fluorescent detection capabilities to address diverse research needs [6] [8]. This guide explores the fundamental principles and procedural workflow of IHC, with particular emphasis on its application in co-localization studies alongside in situ hybridization (ISH) for comprehensive spatial biology analysis. Understanding the complete IHC workflow—from sample preparation through antibody selection to final detection—is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data that advances our understanding of complex biological systems in both health and disease.

Fundamental Principles of IHC

Historical Development and Core Principles

The conceptual foundation of IHC traces back to pioneering work in immunology and histology, with critical developments emerging throughout the 20th century. The technique fundamentally combines anatomical, immunological, and biochemical approaches to image discrete components in tissues using appropriately labeled antibodies that bind specifically to their target antigens in situ [9]. The earliest breakthroughs came with the identification of antibody-antigen interactions, for which Paul Ehrlich received the Nobel Prize in 1908 [6]. However, it was Albert H. Coons and colleagues in the 1940s who developed the first fluorescently conjugated antibody system closely resembling contemporary methods, using fluorescein-labeled anti-pneumococcal antibodies to detect bacteria within macrophages [6] [7]. Reflecting on his work, Coons noted the aesthetic appeal of fluorescent antibodies, describing how they "shine in the dark, a brilliant greenish-yellow glow" like "pebbles in the moonlight" that "weave a pattern in the forest which leads the weary children home" [6].

The core principle of IHC involves specific binding of antibodies tagged with labels to target antigens within tissues, enabling visualization of the localization and distribution of specific antigens [7]. This binding occurs between the paratope of an antibody and a specific epitope on the target antigen, creating a stable complex that can be visualized through various detection methods. The technique can be performed using either direct or indirect methods, with the indirect approach employing secondary antibodies that bind to the primary antibody to provide signal amplification [7] [10]. IHC is particularly valued for its ability to provide spatial context that other protein detection methods like western blot or ELISA cannot offer, as it preserves the architectural relationships between cells and tissues while enabling specific protein detection [6].

Comparison with Other Protein Detection Techniques

When selecting appropriate protein detection methodologies, researchers must consider the unique advantages and limitations of each technique. The table below provides a comparative analysis of IHC against other common protein detection methods:

Table 1: Comparison of IHC with Other Protein Detection Techniques

| Parameter | IHC/ICC | Western Blot | ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Fixed cells on coverslip (ICC) or fixed tissue sections (IHC) | Lysed cells, denatured protein | Lysed cells or tissue, biological fluids |

| Protein State | In situ, but fixed | Denatured | Native, unfixed |

| Multiplex Capability | Easily up to 4 targets; more possible with advanced methods | Possible with fluorescent multiplexing or sequential blotting | Typically requires bead-based immunoassays |

| High Throughput | Yes | Rarely | Commonly |

| Sensitivity | Medium | High | High |

| Specificity | Medium | High | High, particularly sandwich ELISA |

| Subcellular Localization | Highly suitable | Limited to subcellular fractionation | Limited to subcellular fractionation |

| Expression in Mixed Cell Populations | Highly suitable | Limited to cell sorting | Limited to cell sorting |

This comparative analysis highlights IHC's unique strength in providing spatial context for protein localization, which is particularly valuable for understanding protein function in heterogeneous tissues and investigating co-localization patterns with other biomarkers [6].

The Complete IHC Workflow

Sample Preparation and Fixation

The initial steps of sample preparation and fixation are critical for preserving tissue architecture and antigen integrity, ultimately determining the success of any IHC experiment. Proper fixation stabilizes cells and tissues to prevent degradation during processing while maintaining morphological detail essential for accurate interpretation [7]. The choice of fixing solution depends on sample type, target antigen, and downstream applications, with no universal fixative suitable for all situations [6]. Formaldehyde-based fixatives are most commonly used due to their strong tissue penetration and low background, creating methylene cross-links between proteins or between proteins and nucleic acids [6]. However, overfixation with formaldehyde can mask target epitopes through excessive cross-linking, necessitating optimization of fixation conditions including duration, temperature, and pH [6].

Alternative fixatives include glutaraldehyde, which provides stronger cross-linking but penetrates tissue more slowly and can produce high autofluorescence, and precipitative fixatives like methanol and ethanol, which cause protein precipitation by changing dielectric points but preserve morphology less effectively than formaldehyde [6]. Researchers can employ either perfusion fixation, where fixative is injected through the vascular system of an intact organism, or immersion fixation, where dissected tissue is placed directly into fixative [6]. Following fixation, tissues are typically embedded in paraffin or optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and sectioned into thin slices (usually 4-5μm) using a microtome or cryostat, then mounted onto slides, preferably charged or APES-coated slides for IHC to ensure proper adhesion during subsequent processing steps [10].

Antigen Retrieval and Tissue Blocking

For formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, antigen retrieval represents a crucial step to reverse the cross-links formed during fixation that can mask target epitopes and prevent antibody binding [7]. This process typically involves heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER), where slides are heated in a buffer solution (commonly citrate or EDTA-based at varying pH levels) using a microwave, pressure cooker, or water bath [10]. The specific retrieval conditions must be optimized for each primary antibody and tissue type, as insufficient retrieval results in weak staining while excessive retrieval can damage tissue morphology or create non-specific background [10]. Following antigen retrieval, tissues are blocked to prevent non-specific antibody binding. This involves incubating sections with protein-based blocking solutions (such as normal serum, BSA, or commercial blocking reagents) to occupy hydrophobic and charged sites that might otherwise interact non-specifically with antibodies [6] [9]. Additionally, for peroxidase-based detection systems, endogenous peroxidase activity must be quenched using hydrogen peroxide solutions, while endogenous phosphatase activity should be blocked when using alkaline phosphatase-based detection [10].

Antibody Incubation and Detection Systems

The core of IHC involves sequential antibody applications to specifically label target antigens. The process begins with incubation of the primary antibody, which specifically recognizes the target antigen [10]. Researchers must carefully select primary antibodies validated for IHC applications and optimize their concentrations through titration to balance specific signal against background staining [9]. Both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies can be effective for IHC, with monoclonal antibodies offering higher specificity to a single epitope but potentially greater risk of epitope burial, while polyclonal antibodies recognize multiple epitopes, providing increased sensitivity but potentially more cross-reactivity [9].

Following primary antibody incubation, detection typically employs indirect methods using enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies that recognize the host species of the primary antibody [7] [10]. Modern detection systems often utilize polymer-based technologies where multiple enzyme molecules are conjugated to a polymer backbone that binds to the primary antibody, providing significant signal amplification compared to traditional avidin-biotin complex (ABC) or streptavidin-biotin methods [10]. The enzymes most commonly used are horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AP), each with distinct substrate options that produce different colored precipitates at the antigen site [10] [11]. The visualization step then employs chromogenic or fluorescent substrates that produce insoluble precipitates or fluorescence at the antigen location, enabling visualization under light or fluorescence microscopy, respectively [6] [10].

Counterstaining, Mounting, and Visualization

The final steps in IHC processing involve counterstaining to provide morphological context, mounting for preservation, and visualization through microscopy. Counterstaining uses dyes such as hematoxylin (for chromogenic detection) or nuclear stains like DAPI (for fluorescent detection) to highlight tissue architecture and cellular components that are not specifically labeled by the primary antibody [6] [10]. For chromogenic IHC, hematoxylin provides a blue nuclear stain that contrasts with brown (DAB) or red (AP-based) chromogen signals, allowing pathologists to assess the relationship between antigen expression and tissue morphology [10]. Following counterstaining, sections are dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, and mounted under coverslips using permanent mounting media for chromogenic detection or aqueous media for fluorescent detection [9]. Visualization then occurs using brightfield microscopy for chromogenic detection or fluorescence microscopy with appropriate filter sets for fluorescent detection, with digital imaging often employed for documentation and analysis [6] [8].

Figure 1: Comprehensive IHC Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential steps in the immunohistochemistry process, from initial sample preparation through final visualization.

Detection Methods: Chromogenic vs. Fluorescent

Chromogenic Detection

Chromogenic detection represents the most widely used IHC detection method, particularly in clinical settings, due to its convenience, reliability, and compatibility with standard brightfield microscopy [12] [8]. This method utilizes enzyme-conjugated antibodies (typically HRP or AP) that generate colored precipitates at the antigen site when incubated with appropriate substrates [6] [10]. The most common chromogen is 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB), which produces a brown precipitate when reacted with HRP and is preferred for most applications due to its permanent nature and strong staining intensity [10]. For tissues with inherent brown pigmentation (such as melanin), or for multiplexing applications, alternative chromogens including red (Vector Red, Fast Red), blue (Vector Blue), or purple substrates are available [8] [11]. Chromogenic IHC offers several advantages, including permanent slides that do not fade over time, compatibility with routine histology infrastructure, and the ability to easily visualize tissue morphology alongside specific staining [12] [8]. However, limitations include potential diffusion of the reaction product away from the antigen site, difficulty in multiplexing beyond 2-3 targets due to color overlap, and quantification challenges [8].

Fluorescent Detection

Immunofluorescence (IF) detection utilizes fluorophore-conjugated antibodies that are directly visualized using fluorescence microscopy [6]. This method has grown in popularity due to advances in fluorescence microscopy and the increasing availability and flexibility of fluorophores [6] [8]. Fluorescent detection can be performed using either direct methods (with fluorophore-conjugated primary antibodies) or, more commonly, indirect methods (with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies) [9]. The key advantage of fluorescent detection lies in its capability for multiplexing, as multiple targets can be visualized simultaneously using fluorophores with non-overlapping emission spectra [6] [8]. Modern imaging systems can distinguish between 4-7 targets on the same tissue section, enabling sophisticated co-localization studies [8]. Additionally, fluorescent detection generally offers better resolution for subcellular localization and is more amenable to quantification than chromogenic methods [8]. Limitations include potential photobleaching, tissue autofluorescence, requirement for specialized microscopy equipment, and the inability to visualize underlying tissue morphology without additional counterstains [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Chromogenic and Fluorescent Detection Methods

| Parameter | Chromogenic Detection | Fluorescent Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopy Requirements | Standard brightfield microscope | Fluorescence microscope with specific filter sets |

| Permanence | Permanent, fade-resistant | Subject to photobleaching over time |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited (typically 2-3 targets) | High (4+ targets with spectral separation) |

| Spatial Resolution | Good | Excellent for subcellular localization |

| Tissue Morphology | Easily visualized with counterstain | Obscured without brightfield counterstain |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative, challenging | More amenable to quantification |

| Primary Applications | Diagnostic pathology, single targets | Multiplexing, co-localization studies, research |

| Cost Considerations | Lower equipment costs | Higher equipment and reagent costs |

Substrate Selection Considerations

Choosing appropriate substrates represents a critical decision point in IHC experimental design, with several technical factors influencing optimal selection [11]. For HRP-based systems, DAB provides the highest sensitivity and produces a sharp, dense precipitate ideal for intracellular targets or highly delineated locations [11]. Alternative HRP substrates are available in various colors including purple, red, blue, and green for multiplexing applications [11]. For AP-based systems, Vector Red, Vector Blue, and BCIP/NBT are common choices, with AP substrates generally producing more diffuse and translucent precipitates that allow better visualization of underlying tissue structure [11]. Sensitivity requirements should guide substrate selection, with different formulations of the same substrate offering varying detection thresholds; for example, ImmPACT substrates provide maximum sensitivity compared to standard formulations [11]. Researchers should also consider compatibility with visualization methods (brightfield, darkfield, electron microscopy), heat resistance for protocols requiring heating steps, and color contrast with both the tissue specimen and any counterstains [11].

Figure 2: Detection Method Decision Framework. This diagram outlines key considerations when selecting between chromogenic and fluorescent detection methods for IHC applications.

IHC in Co-localization Studies with ISH

Complementary Techniques for Spatial Biology

The integration of IHC with in situ hybridization (ISH) represents a powerful approach for co-localization studies, enabling researchers to simultaneously investigate protein expression and nucleic acid distribution within the spatial context of tissues [12]. While IHC detects protein antigens using antibody-epitope interactions, ISH identifies specific DNA or RNA sequences through complementary nucleic acid probes [12]. This combination provides comprehensive molecular profiling within morphological context, particularly valuable for understanding gene expression patterns, viral infection detection, and characterizing genetic alterations alongside protein expression [12]. For cancer research specifically, IHC-ISH co-localization can identify tumor cells with specific genetic abnormalities while characterizing their protein expression profiles, enabling more precise tumor classification and insights into tumor heterogeneity [12] [13]. Studies have demonstrated high concordance between IHC and ISH for certain markers, with one investigation reporting 91.3% agreement (κ-coefficient: 0.848) between TTF-1 protein detection by IHC and TTF-1 mRNA detection by ISH in non-small cell lung carcinoma [13].

Experimental Design for IHC-ISH Co-localization

Designing effective IHC-ISH co-localization studies requires careful consideration of several experimental parameters. Researchers must determine whether to perform the techniques sequentially on the same section or on serial sections, with each approach offering distinct advantages [12]. Sequential staining on the same section preserves perfect spatial registration but requires optimization to prevent interference between detection systems, while serial sections maintain protocol integrity but introduce registration challenges during analysis [12]. The order of staining represents another critical consideration, with ISH typically performed before IHC when detecting RNA targets to prevent degradation, while DNA targets may be more stable to subsequent IHC processing [12]. Control experiments are essential to validate specificity and prevent false positives, including omission of primary antibody or probe, use of sense or scrambled probes for ISH, and validation with known positive and negative samples [12] [13]. For detection method selection, chromogenic IHC paired with chromogenic ISH allows simultaneous brightfield visualization but limits multiplexing capacity, while fluorescent detection of both enables higher multiplexing but may complicate morphological assessment [8]. Hybrid approaches using chromogenic for one method and fluorescent for the other can provide balanced solutions for specific research questions [8].

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Recent technological advances have significantly expanded the capabilities of IHC-ISH co-localization studies, particularly through multiplexing approaches and computational integration. Modern multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) panels now enable simultaneous detection of 5-10 protein markers alongside RNA or DNA targets, providing unprecedented resolution of cellular phenotypes and functional states within tissue architecture [14]. These advanced applications have been facilitated by improvements in probe design, signal amplification systems, and imaging technologies including spectral imaging and confocal microscopy [8] [14]. Computational approaches for image analysis have similarly evolved, with co-registration algorithms enabling precise alignment of IHC and ISH images at the single-cell level, as demonstrated in recent studies where the average cell-cell distance between H&E and mIF images was 3.1 microns, below the average nucleus size of 7.6 microns [14]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning further enhances these applications, with deep learning models now capable of classifying cell types on H&E images with 86%-89% overall accuracy when trained using mIF-defined cell types as ground truth [14]. These developments open new possibilities for spatial biomarker discovery and comprehensive tissue analysis in both research and clinical contexts.

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful IHC experiments require careful selection of reagents and research solutions optimized for specific applications. The table below outlines key components of the IHC toolkit with their respective functions and selection considerations:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for IHC Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Formalin, Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Ethanol, Methanol | Preserve tissue architecture and antigen integrity; formaldehyde-based fixatives most common for cross-linking |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0), EDTA/TRIS-EDTA (pH 8.0-9.0) | Reverse formaldehyde cross-linking; pH and buffer choice depend on target antigen |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, BSA, Commercial protein blocks | Reduce non-specific antibody binding; should match host species of secondary antibody |

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal vs. polyclonal; concentrate vs. ready-to-use (RTU) | Recognize specific target antigens; require validation for IHC applications |

| Detection Systems | HRP-based, AP-based, polymer systems, avidin-biotin | Signal amplification and visualization; polymer systems offer enhanced sensitivity |

| Chromogenic Substrates | DAB (brown), Vector Red, Vector Blue, BCIP/NBT (blue) | Enzyme substrates producing insoluble colored precipitates |

| Fluorophores | Alexa Fluor series, FITC, TRITC, Cy dyes | Fluorescent labels for detection; selection based on microscope filter availability |

| Counterstains | Hematoxylin, DAPI, Methyl Green | Provide morphological context; nuclear staining for orientation |

| Mounting Media | Aqueous (fluorescence), Permanent (chromogenic) | Preserve staining and enable visualization |

When selecting antibodies for IHC, researchers must consider whether the antibody has been validated for IHC applications, its specificity for the target epitope, and the host species, particularly for multiplexing experiments where primary antibodies from different species are required to prevent cross-reactivity [9]. The format of antibodies—concentrated versus ready-to-use (RTU)—represents another consideration, with concentrates offering flexibility and lower initial costs but requiring validation of working dilutions, while RTU formats provide consistency and save preparation time [10]. For detection systems, polymer-based technologies generally offer enhanced sensitivity compared to traditional avidin-biotin systems, with multiple enzyme molecules conjugated to antibody-binding polymers providing significant signal amplification [10]. Recent advances in reagent development include increased sensitivity substrates allowing higher primary antibody dilutions, expanded color options for multiplexing, and improved fluorophores with brighter signals and enhanced photostability [11].

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common IHC Challenges and Solutions

Even with optimized protocols, IHC experiments can present various challenges that require systematic troubleshooting. Common issues include non-specific background staining, weak or absent specific signal, high background fluorescence, and poor tissue morphology [7] [10]. Non-specific background staining often results from inadequate blocking, improper antibody concentrations, or incomplete washing, and can be addressed by optimizing blocking conditions, titrating antibodies, and ensuring thorough washing between steps [10]. Weak specific signal may indicate insufficient antigen retrieval, primary antibody concentration too low, or detection system limitations, potentially resolved by optimizing retrieval conditions, increasing primary antibody concentration, or switching to more sensitive detection systems [10]. For fluorescent detection, high background can stem from tissue autofluorescence, which can be reduced using autofluorescence quenching reagents, or from overamplification, addressed by reducing antibody concentrations or detection incubation times [8]. Proper controls are essential for effective troubleshooting, including positive control tissues known to express the target antigen, negative controls omitting the primary antibody, and internal positive controls within the test tissue when available [7] [10].

Quality Assurance in IHC

Implementing robust quality control measures is essential for generating reliable, reproducible IHC data, particularly in research settings and especially when integrating IHC with ISH for co-localization studies [7]. Quality assurance begins with proper tissue handling and fixation, using standardized fixation conditions (fixative type, pH, temperature, duration) to minimize variability [10]. Validation of each primary antibody for its intended application represents another critical component, following established guidelines for antibody validation including demonstration of specificity through appropriate controls [9]. Routine monitoring of equipment performance, including microscopes, stainers, and water baths, ensures consistent results [10]. For quantitative or semi-quantitative IHC, implementation of standardized scoring systems helps minimize inter-observer variability, with digital pathology approaches and artificial intelligence algorithms increasingly used to provide more objective assessment [7] [15] [14]. Documentation of all protocol details and quality control results enables traceability and facilitates troubleshooting when issues arise [10]. For IHC-ISH co-localization studies, additional quality measures include validation of co-registration accuracy and controls for potential interference between the two techniques [13] [14].

Future Perspectives in IHC Technology

The field of IHC continues to evolve with emerging technologies and methodologies enhancing its capabilities for research and clinical applications. Several key trends are shaping the future of IHC and its integration with spatial biology approaches. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence represent perhaps the most transformative development, with whole-slide imaging enabling automated analysis and AI algorithms providing objective, quantitative assessment of staining patterns [7] [15]. These technologies facilitate high-throughput analysis and discovery of novel morphological patterns beyond human perception, with studies demonstrating AI models capable of classifying cell types on H&E images with 86%-89% accuracy when trained using multiplex immunofluorescence as ground truth [14]. Multiplexing capabilities continue to expand, with new methodologies enabling simultaneous detection of numerous protein markers alongside DNA and RNA targets, providing comprehensive molecular profiling within tissue architecture [8] [14]. These advances include cyclic immunofluorescence approaches that overcome spectral limitations through sequential staining and imaging, potentially enabling dozens of targets to be visualized on the same section [14]. Integration with other omics technologies represents another frontier, with spatial transcriptomics and proteomics approaches complementing IHC data to provide comprehensive understanding of tissue organization and function [14]. Finally, standardization and automation continue to improve reproducibility, with automated stainers, standardized reagents, and quantitative analysis pipelines increasing consistency across experiments and laboratories [7] [10]. These developments collectively promise to enhance the precision, throughput, and informational yield of IHC and its applications in co-localization studies with ISH.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that enables the precise localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within fixed tissues and cells, providing crucial temporal and spatial information about gene expression and genetic loci [16]. As life science research increasingly focuses on spatial context, ISH has become indispensable for visualizing the distribution of genes or transcripts directly in their native morphological environment [17]. This capability is particularly valuable in co-localization studies with immunohistochemistry (IHC), where researchers can correlate nucleic acid localization with protein expression patterns within the same sample [18]. The technique's power lies in its ability to bypass the need for nucleic acid extraction and purification, instead preserving the architectural context of the tissue while obtaining specific localization data [16]. As technology advances, ISH continues to evolve with improvements in precision, speed, and adaptability, making it an increasingly powerful tool for researchers and clinicians investigating gene expression patterns, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development [17].

Core ISH Methodologies: A Technical Comparison

The fundamental principle of ISH involves using a labeled, target-specific nucleic acid probe that hybridizes with complementary sequences within a biological sample [16]. While this core concept remains consistent across methodologies, implementation varies significantly based on detection method and application requirements. Modern ISH platforms primarily utilize two detection approaches: fluorescence (FISH) and chromogenic (CISH), each with distinct advantages and ideal applications [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Core ISH Methodologies

| Technique | Instrument/Visualization Method | Primary Advantage | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CISH | Bright-field microscopy | Ability to view signal and tissue morphology simultaneously | Molecular pathology diagnostics |

| DNA-FISH | Fluorescence microscopy | Multiplexible: visualize multiple targets in the same sample | Gene presence, copy number, and location; mutation analysis |

| RNA-FISH | Fluorescence microscopy, HCS, and flow cytometry | Multiplexible: visualize multiple targets in the same sample | Gene expression, RNA temporal and spatial localization |

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) enables researchers to assay multiple targets simultaneously and visualize co-localization within a single specimen [16]. Using spectrally distinct fluorophore labels for each hybridization probe, this approach provides the power to resolve several genetic elements or multiple gene expression patterns in a single specimen with multicolor visual display [16]. RNA-FISH using branched DNA signal amplification, such as in Invitrogen ViewRNA and PrimeFlow assays, represents a particularly advanced implementation that employs specialized signal amplification for detection, resulting in greater specificity, lower background, and higher signal-to-noise ratios [16].

Chromogenic ISH (CISH), in contrast, utilizes enzyme-based detection methods that produce a permanent, precipitating colorimetric signal visible under standard bright-field microscopy [16]. This characteristic makes CISH especially valuable for diagnostic pathology applications where simultaneous assessment of tissue morphology and genetic alterations is required, and where archival tissue samples may need to be stored long-term without signal degradation [16].

The Complete ISH Workflow: From Probe Design to Detection

Probe Design and Selection

Selecting the appropriate probe is a critical factor determining ISH experimental success [5]. RNA probes, particularly antisense RNA probes, have become a preferred approach due to their high sensitivity and specificity for target RNA sequences [5]. These probes are commonly generated by in vitro transcription from a DNA template and designed to hybridize specifically to target RNA sequences within tissue samples [5]. Optimal RNA probes should be 250–1,500 bases in length, with probes of approximately 800 bases long typically exhibiting the highest sensitivity and specificity [5]. For DNA probes, which provide high sensitivity but don't hybridize as strongly to target mRNA molecules compared to RNA probes, formaldehyde should be avoided in post-hybridization washes [5].

Probe specificity is paramount for successful ISH experiments [5]. If the exact nucleotide sequence of the target mRNA or DNA is known, a precise complementary probe can be designed. However, if more than 5% of base pairs are not complementary, the probe will only loosely hybridize to the target sequence, making it more likely to be washed away during processing and potentially not correctly detected [5]. Transcription templates should allow for transcription of both probe (antisense strand) and negative control (sense strand) RNAs, typically achieved by cloning into a vector with opposable promoters [5].

Figure 1: Core ISH Experimental Workflow. The process begins with sample preparation and probe design, proceeds through hybridization and washing steps, and culminates in signal detection and analysis.

Sample Preparation and Storage

Proper storage of tissue samples is critical for preserving nucleic acid integrity and ensuring reliable ISH results [5]. To prevent RNA degradation, tissue samples must be handled with care and stored under conditions that inhibit RNase activity [5]. Common approaches include flash-freeting samples in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection or fixing them in formalin followed by paraffin embedding (FFPE) [5]. FFPE tissues are particularly valuable for ISH as they can be stored for long periods without significant loss of RNA integrity [5]. For slide storage, best practices recommend against storing slides dry at room temperature; instead, storage in 100% ethanol at -20°C, or in a plastic box covered in saran wrap at -20°C or -80°C preserves slides for several years [5].

The preparation and sectioning of tissue samples are essential steps in the ISH protocol [5]. Proper fixation using agents such as paraformaldehyde or formalin preserves tissue structure and nucleic acid integrity, making targets accessible for probe hybridization [5]. After fixation, tissues are typically embedded in paraffin to facilitate thin sectioning with a microtome, producing tissue sections that can be mounted on slides for ISH analysis [5]. A critical consideration throughout sample preparation is preventing RNase contamination, as this enzyme quickly destroys RNA in cells or the RNA probe itself [5]. Users must employ sterile techniques, gloves, and RNase-free solutions to prevent contamination [5].

Hybridization and Stringency Washes

The hybridization process represents the core of the ISH technique, where the probe anneals to its complementary target sequence within the tissue [5]. For paraffin-embedded sections, slides must first be deparaffinized and rehydrated through a series of washes including xylene, ethanol gradients, and finally cold tap water [5]. From this point onward, slides cannot dry as this will cause non-specific antibody binding and high background staining [5].

Antigen retrieval is typically performed by digesting with proteinase K (e.g., 20 µg/mL in pre-warmed 50 mM Tris for 10–20 minutes at 37°C) [5]. Incubation time and proteinase K concentration require optimization for different tissue types, fixation lengths, and tissue sizes [5]. Insufficient digestion reduces hybridization signal, while over-digestion results in poor tissue morphology, making localization of hybridization signal difficult [5].

Hybridization itself involves applying a hybridization solution containing the probe to the tissue section and incubating in a humidified chamber at optimized temperatures (typically between 55–65°C) [5]. During this step, the probe hybridizes to its corresponding target mRNA or cellular DNA [5]. The optimal hybridization temperature depends on the probe sequence and tissue type, and should be optimized for each experimental system [5].

Table 2: Hybridization Solution Components

| Reagent | Final Concentration | Volume per mL of Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | 50% | 500 µL |

| Salts | 5x | 250 µL |

| Denhardt's solution | 5x | 50 µL |

| Dextran sulfate | 10% | 100 µL |

| Heparin | 20 U/mL | 10 µL |

| SDS | 0.1% | 1 µL |

Signal Detection and Imaging

Following hybridization, stringency washes remove non-specifically bound probes to enhance signal-to-noise ratio [5]. Solution parameters such as temperature, salt concentration, and detergent concentration can be manipulated to remove non-specific interactions while preserving specific hybridization [5]. Wash stringency should be optimized based on probe characteristics: for very short probes (0.5–3 kb) or complex probes, washing temperature should be lower (up to 45°C) with lower stringency (1–2x SSC), while for single-locus or large probes, temperature should be around 65°C with high stringency (below 0.5x SSC) [5].

For chromogenic detection systems using digoxigenin-labeled probes, slides are typically blocked with appropriate buffer (e.g., MABT + 2% BSA, milk, or serum) for 1–2 hours at room temperature before applying anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase or horseradish peroxidase [5]. After antibody incubation and washing, colorimetric substrates are added to generate precipitating signals at the site of probe hybridization [5].

Fluorescence detection involves similar principles but uses fluorophore-conjugated antibodies or directly labeled probes, followed by visualization with fluorescence microscopy equipped with appropriate filter sets [16]. Multiplexed FISH experiments require careful selection of spectrally distinct fluorophores and specialized imaging systems capable of distinguishing between multiple fluorescence signals [16].

Advanced ISH Technologies and Performance Comparison

Recent technological advances have significantly enhanced ISH capabilities, particularly through automation, multiplexing, and improved detection efficiency [17]. By 2025, adoption of ISH is expected to accelerate, driven by technological innovations like multiplexing and automation that enable simultaneous detection of multiple targets, reducing analysis time and increasing data richness [17].

The Xenium In Situ platform, commercialized by 10x Genomics, represents a cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics technology capable of mapping hundreds of genes in situ at subcellular resolution [19]. Independent evaluations of this platform demonstrate its high detection efficiency, which matches that of established ISH-based technologies like MERSCOPE and Molecular Cartography [19]. For Xenium, detection efficiency was found to be between 1.2 and 1.5 times higher than that of scRNA-seq (Chromium v2), depending on the metric and region analyzed [19]. When compared to sequencing-based spatial methods like Visium, Xenium was significantly more sensitive at the tissue level, detecting a median of 12.8 times more reads for the same anatomical region [19].

Figure 2: Evolution of ISH Multiplexing Capabilities. ISH technologies have progressed from single-plex detection to highly multiplexed systems capable of simultaneously visualizing hundreds of targets.

Specificity is another crucial performance parameter for evaluating ISH technologies [19]. Negative co-expression purity (NCP) quantifies the percentage of non-co-expressed genes in reference single-cell datasets that do not appear to be co-expressed in SRT datasets [19]. Most modern SRT technologies present high specificity (NCP > 0.8), with Xenium showing slightly lower specificity than some other commercial platforms but consistently higher than CosMx, which presented the lowest values [19].

Advanced ISH platforms also provide three-dimensional and subcellular resolution [19]. Xenium's 3D coordinates enable detection of potential mixed-source signals from cells overlapping strongly in the z-dimension, found in approximately 1.8% of total cells [19]. Segmentation-free analysis approaches can identify subcellular mRNA clusters classified as nuclear, cytoplasmic, or extracellular, revealing subtle yet distinct expression variations between nuclear and cytoplasmic clusters linked to the same cell population [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for ISH Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ISH Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Synthesis | Generate labeled nucleic acid probes for target detection | RNA probes (250-1500 bases), DIG-labeled probes, fluorescent probes [5] |

| Tissue Preservation | Maintain nucleic acid integrity and tissue morphology | Formalin, paraformaldehyde, FFPE protocols, flash-freezing [5] |

| Hybridization Buffers | Create optimal conditions for specific probe-target annealing | Formamide, salts (SSC), Denhardt's solution, dextran sulfate [5] |

| Detection Systems | Visualize hybridized probes | Anti-DIG antibodies, fluorophore conjugates, enzyme substrates [5] |

| Stringency Wash Solutions | Remove non-specifically bound probes | SSC buffers with varying concentrations, temperature control [5] |

| Mounting Media | Preserve samples for microscopy | Aqueous mounting for fluorescence, permanent mounting for brightfield [16] |

Integration with IHC and Multiomic Approaches

The combination of ISH with immunohistochemistry (IHC) creates a powerful multiomic approach for correlating nucleic acid localization with protein expression within the same tissue section [18] [20]. This integration is particularly valuable for studying complex biological processes where spatial relationships between different molecular types provide critical insights [20]. For example, in Alzheimer's disease research, a multiomic approach integrating IHC with mass spectrometry imaging has been used to decipher three-dimensional biomolecular distribution, revealing co-localization patterns between pathological protein aggregates and region-specific lipid dysregulation [20].

In inflammation research, multiplex IHC (MP-IHC) enables quantification of immune cells to assess tissue inflammation [18]. Colocalization analysis in these experiments defines colocalized cells as those co-stained for nuclear markers (e.g., DAPI) and specific immune cell markers (e.g., CD4, CD8, CD20, CD68) [18]. Advanced computational methods like object-based colocalization analysis (OBCA) have been developed to improve accuracy and efficiency in quantifying these colocalized immune cells in tissue sections [18]. Both semi-automated and automated OBCA techniques demonstrate sufficient reliability across diverse cell morphologies and significantly reduce analysis time compared to manual counting, making them particularly valuable as sample sizes increase [18].

When designing integrated ISH-IHC experiments, careful consideration must be given to protocol optimization to preserve both nucleic acid integrity and antigenicity [18] [20]. Experimental conditions must be balanced to avoid compromising either detection method, often requiring validation of antibody compatibility with ISH hybridization conditions and potential adjustments to fixation, permeabilization, or retrieval steps [18].

In situ hybridization remains a cornerstone technique for spatial molecular analysis, with continuous technological advancements expanding its applications and capabilities [17]. The ongoing development of more sensitive, multiplexed, and automated ISH platforms will further establish its role in both basic research and clinical diagnostics [17] [19]. As these technologies evolve, they are likely to become more accessible and integrated into routine workflows, supporting advances in precision medicine and personalized therapies [17].

The current trajectory of ISH innovation focuses on several key areas: enhanced multiplexing capacity through improved probe design and detection chemistries, computational methods for data analysis and image processing, integration with complementary spatial omics technologies, and miniaturization/automation for higher throughput and reproducibility [17] [19]. These developments will continue to push the boundaries of what can be visualized and quantified within intact tissues and cells, providing researchers with increasingly powerful tools to understand spatial gene expression patterns in health and disease [17].

Why Integrate IHC and ISH? Advantages over Western Blot and ELISA for Spatial Multiomics

In the quest to understand complex biological systems, traditional analytical techniques like Western blot and ELISA have provided invaluable, but incomplete, molecular pictures. These conventional methods require tissue homogenization, which irrevocably destroys the spatial context of molecular events—information that is particularly critical in architecturally complex tissues like the brain or tumor microenvironments [21]. The integration of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and In Situ Hybridization (ISH) represents a paradigm shift, enabling researchers to perform spatial multiomics by visualizing both protein and RNA targets within their native tissue architecture. This co-localization approach preserves the crucial "where" that is lost in bulk analysis techniques, offering unprecedented insights into cellular function, heterogeneity, and intercellular communication [21] [22]. This guide objectively compares this integrated spatial approach against established biochemical methods, providing the experimental data and protocols essential for researchers and drug development professionals to advance their investigative capabilities.

Fundamental Differences: Spatial Techniques vs. Bulk Assays

Core Principles and Outputs

IHC uses antibody-epitope interactions to detect and localize proteins directly in tissue sections, providing visual data on protein distribution, abundance, and subcellular localization in a semi-quantitative manner [6]. Similarly, ISH employs nucleic acid probes that hybridize to specific DNA or RNA sequences, allowing precise microscopic localization of genetic material within preserved cells and tissues [12]. Both techniques maintain the structural integrity of samples.

In contrast, Western blot separates denatured proteins by molecular weight via gel electrophoresis before detection with specific antibodies, providing information on protein size and relative abundance in a homogenized sample [23]. ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) detects and quantifies soluble antigens or antibodies in complex mixtures using antigen-antibody binding in microplate wells, offering high sensitivity for quantification but no spatial information [23].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these techniques:

| Feature | IHC | ISH | Western Blot | ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Proteins (antigens) | RNA/DNA (nucleic acids) | Proteins | Proteins, antibodies, hormones |

| Spatial Context | Preserved (cellular/subcellular) | Preserved (cellular/subcellular) | Lost | Lost |

| Sample Processing | Fixed tissue sections [6] | Fixed cells/tissue preparations [12] | Lysed and denatured cells [23] | Lysed cells or biological fluids [23] |

| Protein State | In situ, fixed [6] | N/A | Denatured [23] | Native, unfixed [23] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate (typically up to 4 targets) [6] | Moderate (e.g., 4-plex with ViewRNA) [21] | Low (fluorescent multiplexing possible) | Low (typically single-plex) [6] |

| Throughput | Medium | Medium | Low | High [23] |

| Key Output | Protein localization & semi-quantification | Nucleic acid localization & expression | Protein size & relative abundance | Absolute protein quantification [23] |

Comparative Advantages of IHC-ISH Integration for Spatial Multiomics

Preservation of Spatial Architecture

The most significant advantage of integrating IHC and ISH is the ability to correlate gene expression data (via ISH) with protein localization data (via IHC) within the exact same tissue section. This reveals cell-to-cell heterogeneity and intricate molecular relationships within functional tissue units, such as neuronal circuits or tumor nests, which are completely obliterated in Western blot and ELISA workflows [21] [22]. For instance, a brain mapping study successfully preserved both GFAP (protein) and Gad2 (mRNA) signals in hippocampal regions, revealing intricate neuronal patterns that would be impossible to reconstruct from bulk analyses [21].

Comprehensive Molecular Profiling

Combining IHC and ISH moves beyond single-modality analysis to true spatial multiomics. While Western blot and ELISA provide data on proteins only, integrated IHC-ISH can answer simultaneous questions: Is the mRNA transcript present in a cell (ISH)? Is the corresponding protein also present and where is it localized (IHC)? Are there discrepancies that suggest post-transcriptional regulation? This is invaluable for understanding disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses [21] [24].

Enhanced Validation in Translational Research

IHC and ISH serve as complementary validation tools in spatial biology. In HER-2 breast cancer testing, a combination of IHC for protein overexpression and FISH (a form of ISH) for gene amplification is standard clinical practice. Studies show high concordance rates (84.72% overall, with 100% for IHC 0/1+ and 83.33% for IHC 3+ groups), validating the necessity of both techniques for accurate patient stratification [25]. This cross-validation is more direct and spatially informed than using ELISA to screen and Western blot to confirm, which lacks topological context.

Direct Visualization in Diagnostic Pathology

For diagnostic applications, IHC and ISH provide visually interpretable results within the histopathological context that pathologists are trained to evaluate. The stained slides can be directly correlated with tissue morphology, enabling precise diagnosis and prognosis [12]. Western blot and ELISA, while quantitative, generate data (bands or absorbance values) divorced from tissue structure, requiring inference about cellular origin.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these techniques in the context of spatial information and molecular profiling depth:

Performance and Concordance Data

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate correlations and discrepancies between these methods, underscoring the need for technique selection based on specific research questions.

| Comparison | Key Finding | Implication for Spatial Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Western Blot vs. IHC (p185neu in breast cancer) [26] | 83.1% concordance when considering intermediate and high expressors as positive; rose to 89.1% when only high expressors were considered positive. | IHC provides critical spatial distribution data that Western blot cannot, but semi-quantitative IHC scoring may not capture the full dynamic range of protein abundance. |

| ELISA vs. IHC (p185neu in breast cancer) [26] | 78.9% concordance for combined positive groups; rose to 93.3% when only high expressors were considered positive. | ELISA's quantitative strength is clear, but it fails to identify rare positive cells or heterogeneous expression patterns within a tissue sample. |

| IHC vs. FISH (HER-2 in breast cancer) [25] | 84.72% total concordance; 100% for IHC 0/1+, 18.18% for IHC 2+, and 83.33% for IHC 3+. | Highlights the clinical necessity of combining protein (IHC) and gene (FISH) analysis, especially for equivocal IHC 2+ cases, to guide targeted therapy. |

Technical Protocols for IHC and ISH Integration

Successfully integrating IHC and ISH in the same tissue section requires overcoming significant technical challenges, as optimal conditions for each technique often conflict [21].

Critical Protocol Modifications

The standard protocol conflict is a key hurdle: protease treatments essential for ISH can destroy antibody epitopes for IHC, and RNases introduced during IHC can degrade RNA targets [21]. The following workflow outlines the modified protocol to overcome these challenges:

1. Tissue Preparation: Both formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) and cryopreserved tissues can be used. FFPE samples offer lower RNase activity, while cryopreserved tissues typically provide higher RNA integrity [21].

2. RNase Inhibition: Before IHC labeling, tissues must be pretreated with robust RNase inhibitors (e.g., RNaseOUT) to protect RNA integrity during subsequent antibody incubations [21].

3. Antibody Crosslinking: Following IHC labeling but prior to ISH steps, antibodies must be crosslinked to the tissue using a suitable crosslinker. Standard formaldehyde fixation is insufficient to withstand the harsh protease treatments required for ISH protocols [21].

Detection and Imaging

- RNA Detection: Branched DNA (bDNA) ISH probes (e.g., ViewRNA) enable highly sensitive detection, often at the single-molecule level, preserving spatial context. Fluorescence kits allow simultaneous visualization of up to four RNA targets [21].

- Protein Detection: Directly labeled antibodies or antibodies labeled in-house with kits (e.g., ReadyLabel) provide spectral flexibility. Careful panel design is crucial to minimize spectral overlap and autofluorescence [21].

- Imaging Platforms: Versatile systems ranging from widefield microscopes to specialized spectral imaging instruments (e.g., EVOS S1000) capable of resolving up to nine fluorophores simultaneously are employed. Mounting media (e.g., ProLong RapidSet) prevent photobleaching and ensure signal stability [21].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key reagents and instruments critical for successful implementation of integrated IHC-ISH spatial multiomics studies.

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA targets from degradation during IHC steps. | RNaseOUT recombinant ribonuclease inhibitor [21] |

| ISH Detection Kit | Enables sensitive, multiplexed RNA detection via bDNA signal amplification. | ViewRNA Tissue Assay Kits (fluorescence or colorimetric) [21] |

| Antibody Labeling Kit | Allows flexible conjugation of fluorophores to antibodies for multiplex IHC. | ReadyLabel Antibody Labeling Kits [21] |

| Spectral Imaging System | Simultaneously resolves multiple fluorescence signals for high-plex analysis. | EVOS S1000 Spatial Imaging System [21] |

| Automated IHC Stainer | Provides standardized, high-throughput processing for complex workflows. | ONCORE Pro X Automated IHC Stainer [27] |

| Mounting Medium | Preserves fluorescence and colorimetric signals for long-term archiving. | ProLong RapidSet Mountant [21] |

The integration of IHC and ISH establishes a powerful framework for spatial multiomics, offering a transformative advantage over traditional bulk analysis techniques like Western blot and ELISA. While Western blot and ELISA remain valuable for specific applications requiring high-throughput quantification or protein size characterization, their fundamental limitation is the loss of all spatial information. The IHC-ISH synergy directly addresses this by enabling the co-localization of multiple molecular types within an intact tissue architecture. This capability is proving indispensable for unraveling cellular heterogeneity, understanding the complex biology of the tumor microenvironment, mapping neural circuits, and advancing translational research and diagnostic precision. As the field of spatial biology continues to evolve, the combined use of IHC and ISH will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technique for comprehensively understanding the spatial organization of biological systems.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and In Situ Hybridization (ISH) represent cornerstone techniques in modern investigative pathology, enabling the precise visualization of biomolecules within their native tissue context. IHC uses antibody-epitope interactions to selectively label and visualize proteins in tissue samples, providing data on protein distribution, subcellular localization, and abundance in a semi-quantitative manner [6]. ISH, conversely, detects specific nucleic acid sequences (DNA or RNA) within preserved tissue sections, allowing researchers to visualize gene expression, gene amplification, and chromosomal alterations [28] [29]. The power of these techniques is magnified when they are combined in co-localization studies, which enable researchers to correlate genomic alterations with their functional protein products within the same cellular or tissue compartment. This integrated approach is indispensable for biomarker validation, therapeutic development, and elucidating complex molecular mechanisms in disease pathogenesis, ultimately fueling the advancement of precision medicine [30].

Technical Comparison of Core Methodologies

Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Principles and Detection Systems

The fundamental IHC workflow involves preparing tissue sections (typically formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded, or FFPE), performing antigen retrieval to unmask epitopes, incubating with a primary antibody specific to the target protein, and then detecting the bound antibody using a visualization system [6] [31]. The choice of detection system significantly impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing capability of an IHC assay.

Table 1: Comparison of Common IHC Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Principle | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Method [31] | Primary antibody directly conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., HRP) or fluorophore. | Simple, rapid protocol; minimal non-specific binding. | Low sensitivity; not practical to conjugate every primary antibody. |

| Indirect Method (Secondary Antibody) [31] | Unconjugated primary antibody is detected by an enzyme- or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody. | Enhanced sensitivity due to signal amplification; versatile as one secondary antibody can be used for many primaries from the same species. | Potential for non-specific binding from secondary antibody. |

| Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) [31] | Biotinylated secondary antibody binds a pre-formed complex of Avidin and Biotin-conjugated enzyme (HRP). | High sensitivity due to significant enzyme deposition. | Endogenous biotin in tissues can cause high background. |

| Labeled Streptavidin-Biotin (LSAB) [31] | Biotinylated secondary antibody is detected by enzyme-conjugated Streptavidin. | Reduced non-specific binding compared to ABC due to Streptavidin's neutral charge. | Still susceptible to issues from endogenous biotin. |

| Polymer-Based Method [31] | Secondary antibody and enzyme (HRP/AP) are co-conjugated to a dextran polymer backbone. | High sensitivity; no endogenous biotin interference; faster protocols. | Large polymer size can cause steric hindrance for some epitopes. |

Two enzymes are most commonly used in chromogenic IHC detection: Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). HRP, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, catalyzes the oxidation of substrates like 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) to produce a brown, insoluble precipitate [29]. AP reacts with substrates like Fast Red or Fast Blue to yield red or blue colored products, respectively [31]. The choice of enzyme and substrate is critical for single-plex and multiplexing experiments.

In Situ Hybridization (ISH): Principles and Modalities

ISH involves the hybridization of a labeled complementary DNA or RNA probe to a specific nucleic acid sequence within a tissue section. The two primary modalities are:

- Fluorescence ISH (FISH): Uses fluorescently labeled probes for detection under a fluorescence microscope. It is highly quantitative and allows for multiplexing with multiple colored probes [28].

- Chromogenic ISH (CISH): Uses enzyme-conjugated probes (similar to IHC) that are visualized with a chromogenic substrate, producing a permanent stain viewable with a standard brightfield microscope [29].

While FISH is often considered the gold standard for its precision in gene amplification assessment (e.g., HER2 in breast cancer), it is more costly, requires a fluorescent microscope, and the signal can fade over time. CISH, while less quantitative, is more easily integrated into a standard pathology workflow and provides better morphological context [28].

Experimental Design and Protocols for Co-Localization Studies

Workflow for Sequential IHC and ISH Multiplexing

A robust protocol for performing IHC and ISH on a single slide to co-localize protein and nucleic acid targets is outlined below. This workflow is based on established methods from the literature and can be implemented on automated staining platforms like the Roche DISCOVERY ULTRA [29].

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Tissue Preparation: Cut 4-5 µm sections from FFPE tissue blocks and mount on charged slides. Dry slides thoroughly to prevent tissue detachment.

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: Bake slides at 60°C for 30-60 minutes. Deparaffinize in xylene (or substitute) and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series to distilled water.

- Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) using an appropriate buffer (e.g., citrate, EDTA, TRIS-EDTA at pH 6.0 or 9.0) in a pressure cooker or decloaking chamber. The specific buffer and conditions must be optimized for the primary antibody [6] [31].

- Protein Blocking: Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H₂O₂. Block non-specific protein binding sites with an appropriate protein block (e.g., normal serum, casein, or commercial protein blocks) for 10-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply optimized dilution of the primary antibody in antibody diluent. Incubate according to validated conditions (typically 30-90 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C).

- Polymer-Based Detection: Use a polymer-based HRP or AP detection system according to the manufacturer's instructions. Incubate with the polymer for 20-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Chromogen Development for IHC: Develop the signal using a chromogen such as DAB (brown) for HRP, or Fast Red (red) for AP. Do not apply a nuclear counterstain at this stage.

- ISH Target Retrieval and Denaturation: Depending on the ISH system, a second round of target retrieval and denaturation may be required. For DNA FISH/CISH, this step is critical to denature the DNA and make it accessible for the probe.

- Probe Hybridization: Apply the labeled nucleic acid probe to the tissue section. Coverslip and seal with rubber cement. Incubate in a pre-heated humidified hybridizer or thermal cycler according to the probe's specifications (often overnight at 37°C-45°C).

- Stringency Washes: The following day, remove the coverslip and perform stringency washes (e.g., in 2x SSC or a proprietary wash buffer at a specific temperature) to remove any unbound or loosely bound probe.

- ISH Signal Detection: If using a chromogenic ISH probe (CISH), detect the signal with an appropriate enzyme-conjugated antibody (e.g., anti-FITC-HRP) and a contrasting chromogen (e.g., Fast Blue or Vector Blue if DAB was used for IHC). For FISH, simply apply a DAPI counterstain and a non-fading mounting medium.

- Counterstain and Coverslip: Apply a light nuclear counterstain (e.g., Hematoxylin) if not already applied during the ISH step. Dehydrate through graded ethanols, clear in xylene, and mount with a permanent mounting medium.

Key Considerations for Experimental Design

- Order of Staining: The sequence of IHC and ISH can be reversed. Performing IHC first is often preferred as the harsh denaturation conditions for ISH (especially for DNA) can destroy many protein epitopes.

- Chromogen Selection: Choose chromogens with distinct, non-overlapping colors and that are stable throughout the entire procedure. Translucent chromogens are ideal for co-localization studies as they allow visualization of overlapping signals [29].

- Controls: Include critical controls for both IHC (positive tissue, negative/isotype control) and ISH (positive tissue, negative control probe, and for FISH, a probe for a centromere or another known non-amplified gene). A control slide with IHC or ISH alone is essential to confirm that the first stain does not interfere with or get altered by the second staining procedure.

Comparative Performance Data in Research and Diagnostics

The application of IHC and ISH, particularly in a co-localization context, provides critical data for biomarker validation and clinical diagnostics. The following table summarizes quantitative performance data from published studies, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each technique and their integrated use.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of IHC, ISH, and Integrated Methods in Biomarker Analysis

| Application / Biomarker | Technique | Key Performance Metric | Result / Finding | Implication for Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2 Testing in Breast Cancer [28] | IHC (Manual Scoring) | Semi-quantitative scoring (0 to 3+) | Prone to interobserver variability [28] | Subjectivity can affect treatment decisions. |

| IHC (AI-Assisted Scoring) | Overall Accuracy vs. Pathologist | 91% ± 0.01 [28] | Reduces subjectivity; improves standardization. | |

| FISH | Quantitative (HER2 gene copy number) | Higher precision than IHC [28] | Gold standard for gene amplification; more resource-intensive. | |

| AI predicting FISH from IHC | Specificity | 0.96 ± 0.03 (Internal), 0.93 ± 0.01 (External) [28] | Potential to reduce need for reflex FISH testing. | |

| Predictive Biomarker Identification (e.g., EGFR in NSCLC) [30] | IHC / Molecular (DNA) | Predictive Power (Interaction Test) | P < 0.001 for treatment-biomarker interaction [30] | Requires data from a randomized clinical trial to establish predictive utility. |

| Prognostic Biomarker Identification (e.g., STK11 in NSCLC) [30] | IHC / Molecular | Prognostic Power (Main Effect Test) | Association with poorer overall survival [30] | Can be identified in properly conducted retrospective studies. |

| Multiplexed Co-localization [29] | IHC/ISH Combination | Information Gain | Enables protein co-localization and spatial relationship analysis in single sample [29] | Generates unique data not possible from serial sections. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of IHC and ISH co-localization studies relies on a suite of high-quality reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for IHC-ISH Co-localization Studies

| Category | Item | Function / Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Preparation | Formalin, Paraffin | Standard fixation and embedding for morphology preservation. | Over-fixation can mask epitopes; requires antigen retrieval [6]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers (Citrate, EDTA) | Unmask epitopes cross-linked by formalin fixation. | pH and buffer choice must be optimized for each antibody [31]. | |

| Detection Reagents | Primary Antibodies (Monoclonal, Polyclonal) | Bind specifically to the protein target of interest. | Monoclonals offer specificity; polyclonals can be more sensitive for some fixed targets [31]. |

| Polymer-Based Detection Kits (HRP/AP) | Signal amplification and visualization. | Offer high sensitivity and avoid endogenous biotin issues [31]. | |

| Chromogens (DAB, Fast Red, Fast Blue) | Enzyme substrates that produce colored precipitate at target site. | Choose for contrast, stability, and compatibility with automated stainers [29]. | |