Strategies for Reducing Batch-to-Batch Variability in Organoid Differentiation: A Guide for Reproducible Research

This article addresses the critical challenge of batch-to-batch variability in organoid cultures, a major hurdle in academic and industrial applications.

Strategies for Reducing Batch-to-Batch Variability in Organoid Differentiation: A Guide for Reproducible Research

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of batch-to-batch variability in organoid cultures, a major hurdle in academic and industrial applications. It provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational sources of variability, methodological best practices for standardization, advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and robust validation strategies. By synthesizing current research and emerging technologies, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance the reproducibility, reliability, and translational relevance of organoid models in disease modeling, drug screening, and personalized medicine.

Understanding the Root Causes of Organoid Variability

What are the intrinsic and extrinsic factors contributing to batch-to-batch variability in organoid differentiation?

Batch-to-batch variability in organoid differentiation arises from a complex interplay of intrinsic (cell-inherent) and extrinsic (environmental) factors. Understanding these sources is the first step toward mitigating their effects.

Intrinsic Factors are inherent to the stem cells themselves. A primary concern is genomic instability. Research has shown that the reprogramming process itself, particularly when using proto-oncogenes like c-Myc, can induce DNA replication stress, leading to copy number variations (CNVs) such as deletions and amplifications [1]. Furthermore, stem cells exhibit transcriptional stochasticity, where random fluctuations in gene expression can lead to significant heterogeneity within a population, influencing cell fate decisions [2].

Extrinsic Factors are related to the cell culture environment and protocols. The physical dynamics of the culture system, such as fluid flow shear stress (fFSS) in rotating bioreactors, can disrupt cellular integrity and morphogenesis, leading to dramatic variations in organoid architecture [3]. Other critical extrinsic factors include the oxygen pressure (which is often much higher than physiological levels in standard culture), the composition and rigidity of the culture substrate, and the homeostasis of the culture medium, which constantly changes due to cellular metabolism [4].

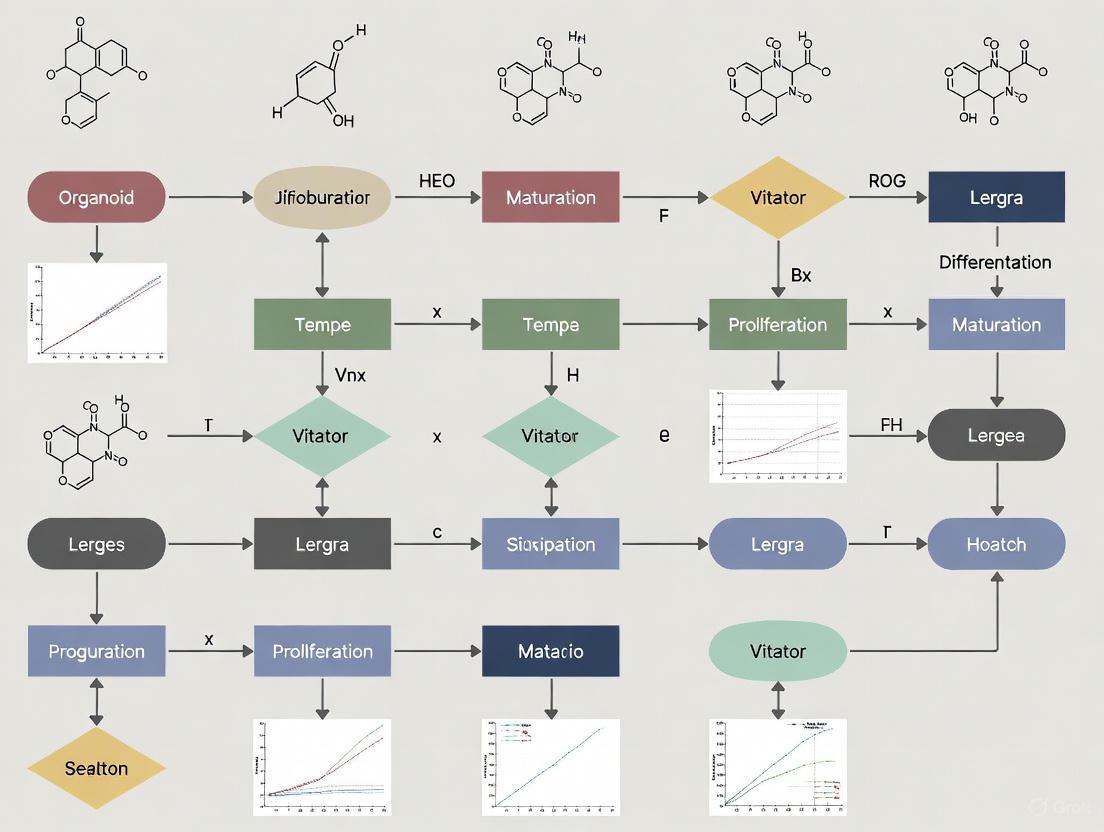

The diagram below illustrates how these intrinsic and extrinsic factors converge to influence stem cell fate and, consequently, organoid reproducibility.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ: Our brain organoids show high structural variability between batches. What is the most likely cause and how can we address it?

Answer: High structural variability is frequently driven by uncontrolled extrinsic factors during critical morphogenesis phases. A 2025 study identified fluid flow shear stress (fFSS) as a major disruptor of organoid architecture [3].

- Likely Cause: Uncontrolled fluid dynamics in your culture system, especially during the neuronal induction phase, generating variable fFSS that disrupts consistent cellular integrity and morphogenesis.

- Recommended Solution: Implement a vertically rotating chamber designed to minimize fFSS during the critical differentiation window. This approach, coupled with an extended cell aggregation phase to minimize organoid fusions, has been shown to significantly improve the reproducibility of brain organoid morphology and transcriptional signatures [3].

FAQ: Our iPSC lines accumulate genetic abnormalities over long-term culture, affecting downstream differentiation. How can we manage this intrinsic instability?

Answer: Genetic instability is a well-documented intrinsic challenge in pluripotent stem cells. The reprogramming process can introduce mutations, and extended passaging can select for aberrant clones [1] [4].

- Likely Cause: Oncogene-induced DNA replication stress from factors like c-Myc used in reprogramming, combined with selective pressure in culture that allows genetically abnormal cells to outcompete normal ones [1].

- Recommended Solution:

- Start with High-Quality Cells: Use fully characterized, high-quality stem cell banks to ensure your starting population has minimal genetic abnormalities [5].

- Regular Quality Control: Implement frequent genomic monitoring (e.g., karyotyping, CGH arrays) to detect CNVs early [1].

- Optimize Culture Conditions: Avoid conditions that impose high selective pressure. Using defined media and ROCK inhibitors can improve clonal survival without favoring mutated cells [4].

FAQ: How does oxygen tension act as an extrinsic factor to influence stem cell fate and differentiation stochasticity?

Answer: Oxygen is a potent signaling molecule that regulates metabolic pathways and transcription factors. Physiological stem cell niches, like the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche, are hypoxic [2]. Culturing under atmospheric oxygen (21%) is non-physiological and creates oxidative stress.

- Impact on Hematopoiesis: Computational models of HSC differentiation show that oxygen activates ROS production, which in turn inhibits quiescence and promotes growth and differentiation pathways. This shifts the balance of cell fates within a population [2].

- Recommendation: For protocols aimed at maintaining stemness or mimicking in vivo niches, consider reducing oxygen tension in incubators to more physiological levels (e.g., 1-5% O₂) to reduce replication stress and improve differentiation fidelity [4] [2].

Optimized Experimental Workflows

The following workflow integrates mitigation strategies for both intrinsic and extrinsic variables to enhance reproducibility in organoid generation.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Variability

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Reducing Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Vertically Rotating Chamber | Controls fluid dynamics to minimize fluid flow shear stress (fFSS) | Critical for improving morphological reproducibility during brain organoid induction [3]. |

| Defined, Serum-Free Media | Replaces ill-defined additives (e.g., serum) with precise formulations | Eliminates batch-to-batch variability from serum and supports standardized, xeno-free conditions [4] [5]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (e.g., ROCKi) | Inhibits Rho-associated kinase | Increases survival of dissociated hPSCs, reducing selective pressure and clonal artifacts [4]. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors | Provides precise concentrations of signaling molecules (e.g., EGF, Noggin, R-Spondin) | Ensures consistent activation of key differentiation and self-renewal pathways [4] [6]. |

| Synthetic Matrices | Provides a defined, reproducible substitute for animal-derived matrices (e.g., Matrigel) | Reduces variability in substrate composition and stiffness, improving control over cell fate [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide to Common Variability Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High structural heterogeneity in organoids | Uncontrolled fluid flow shear stress (fFSS) [3]. | Adopt a vertically rotating bioreactor system during critical morphogenetic phases. |

| Emergence of genetic abnormalities | Oncogene-induced replication stress (e.g., from c-Myc); selective pressure in culture [1]. | Use integration-free reprogramming; monitor karyotype regularly; use low-passage cells. |

| Low differentiation efficiency | Ill-defined media components; non-physiological oxygen tension [4] [2]. | Switch to defined media supplements; culture under low oxygen (physoxic) conditions. |

| Poor cell survival after passaging | Mechanical and apoptotic stress on dissociated cells [4]. | Supplement culture medium with a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) for 24-48 hours post-passage. |

| Inconsistent organoid yield | Variable starting cell quality and aggregate size [5]. | Begin with fully characterized hPSCs; use controlled aggregation methods (e.g., microplates) [6]. |

Organoid technology has emerged as a transformative tool in biomedical research, enabling the in vitro modeling of human organs with remarkable physiological relevance. A critical factor influencing the success and reproducibility of these models is the choice of starting material. Organoids are primarily derived from two sources: Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs), which include embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and Adult Stem Cells (AdSCs), also known as tissue-specific stem cells [7]. Each starting material possesses inherent characteristics that significantly impact the variability, application, and challenges of the resulting organoid cultures. Understanding these differences is paramount for researchers aiming to reduce batch-to-batch variability and improve the reliability of their experiments in disease modeling, drug screening, and developmental biology.

Comparative Analysis: PSC-derived vs. AdSC-derived Organoids

The table below summarizes the core differences between these two organoid types, which are a primary source of variability.

| Characteristic | PSC-Derived Organoids | Adult Stem Cell (AdSC)-Derived Organoids |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Source | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) or induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [7] | Tissue-specific stem cells (e.g., Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells) [8] [7] |

| Developmental Process Modeled | Organogenesis and early embryonic development [8] [7] | Adult tissue homeostasis, regeneration, and repair [8] [7] |

| Cellular Complexity | High; can contain multiple germ layers and cell types, including epithelial, mesenchymal, and endothelial components [9] [7] | Lower; typically limited to the epithelial cell lineages of the organ of origin [8] [9] |

| Inherent Variability Drivers | Stochastic differentiation, complex morphogenesis, protocol multi-step complexity [8] [10] | Donor-to-donor genetic heterogeneity, tissue sampling site differences [8] [6] |

| Typical Maturity State | Fetal-like; often lack full adult functionality [10] [7] | More mature; closer to adult tissue phenotype [7] |

| Primary Research Applications | Studying human development, genetic disorders (e.g., microcephaly), and neurodevelopmental diseases [11] [10] [7] | Modeling adult diseases (e.g., cancer, cystic fibrosis), infectious diseases, and personalized drug screening [8] [12] [7] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are my PSC-derived organoids so heterogeneous in size and structure, even within the same batch?

A1: This is a common challenge rooted in the biology of PSC differentiation. The process involves stochastic differentiation and poorly controlled morphogenesis during self-assembly [10]. The complex, multi-step protocols required to guide PSCs through developmental pathways are inherently sensitive to minor fluctuations. To mitigate this:

- Standardize Cell Numbers: Precisely control the initial cell number and aggregation step (e.g., using microwell plates) to generate uniform embryoid bodies [10].

- Optimize Agitation: Use oscillating bioreactors to ensure consistent nutrient and morphogen distribution, reducing central necrosis and improving uniformity [10].

- Engineered Matrices: Transition from variable, natural matrices like Matrigel to more defined, synthetic hydrogels to provide a consistent physical and biochemical microenvironment [10].

Q2: Our lab works with patient-derived intestinal organoids (AdSCs). How can we manage the high genetic variability between samples from different donors?

A2: Donor-to-donor genetic heterogeneity is a fundamental feature of AdSC-derived organoids, not a flaw, as it mirrors human population diversity [8]. The goal is not to eliminate this variability but to control and account for it experimentally.

- Increase Sample Size: Use organoid biobanks with multiple donor lines to ensure findings are not unique to a single genetic background [12].

- Isogenic Controls: For genetic studies, use CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to create genetically corrected (or mutated) lines from a patient-derived organoid, providing the perfect internal control [13] [7].

- Rigorous Stratification: Document and stratify your samples based on critical clinical parameters such as patient age, disease stage, tumor location (e.g., proximal vs. distal colon), and genetic makeup before pooling data [6].

Q3: What are the main engineering strategies to reduce variability in both PSC and AdSC-derived organoid systems?

A3: Engineering approaches are key to standardizing organoid culture.

- Automation: Implementing robotic liquid handling systems for initial stem cell allocation, media changes, and drug testing minimizes manual handling errors and improves reproducibility [14] [10].

- Organoid-on-Chip Technologies: Microfluidic chips allow for precise control over the microenvironment, including dynamic flow of nutrients and drugs, mechanical forces, and cell-cell interactions, leading to more consistent and mature organoids [13] [10].

- Advanced Monitoring: Utilize high-content imaging, multi-electrode arrays, and integrated biosensors for continuous, minimally invasive functional monitoring, providing richer and more objective data sets than endpoint assays alone [10].

Key Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Variability

Protocol 1: Standardized Initiation of Colonic AdSC-Derived Organoids

This protocol, adapted from current methodologies, emphasizes steps critical for reducing initial variability in one of the most common AdSC-derived organoid systems [6].

Goal: To establish reproducible patient-derived colorectal organoid cultures from tissue biopsies.

Critical Materials:

- Cold Advanced DMEM/F12: For tissue transport and washing.

- Antibiotic Solution: e.g., Penicillin-Streptomycin, to prevent microbial contamination.

- Digestion Enzyme: Collagenase or Dispase to dissociate tissue and isolate crypts.

- Basement Membrane Matrix: Matrigel or similar ECM substitute.

- Intestinal Organoid Growth Medium: Must be supplemented with essential niche factors: EGF (promotes proliferation), Noggin (BMP antagonist), and R-spondin 1 (Wnt pathway agonist) [8] [6] [15].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Tissue Procurement & Transport: Process samples immediately post-collection. Place tissue in cold medium with antibiotics. Critical Step: Minimize transit time. If processing is delayed beyond 6-10 hours, cryopreservation is recommended to maintain cell viability [6].

- Tissue Dissociation: Wash tissue thoroughly with antibiotic solution. Mechanically mince and enzymatically digest the tissue to release intact crypt structures.

- Crypt Isolation: Filter the digestate through a strainer (e.g., 100μm) to remove large debris. Centrifuge to pellet the crypts.

- Embedding in Matrix: Resuspend the crypt pellet in a defined, chilled basement membrane matrix. Plate small droplets of the matrix-cell suspension and allow them to polymerize.

- Culture Initiation: Overlay the polymerized droplets with pre-warmed complete intestinal organoid growth medium. Change the medium every 2-3 days.

- Passaging: Once organoids are large and convoluted (typically every 7-14 days), dissociate them mechanically or enzymatically and re-embed fragments in fresh matrix for continued expansion.

Protocol 2: Directed Differentiation of PSC-Derived Cerebral Organoids

This protocol outlines the key stages for generating brain organoids, highlighting points where variability is often introduced.

Goal: To generate cortical organoids from human PSCs with reduced batch-to-batch heterogeneity.

Critical Materials:

- Human PSCs: High-quality, karyotypically normal iPSC or ESC line.

- Neural Induction Medium: Typically a defined medium lacking FGF2 and TGFβ, often containing SMAD inhibitors (e.g., Dorsomorphin, SB431542) to direct neural fate [7].

- Matrigel: Provides a 3D scaffold for morphogenesis.

- Differentiation Medium: Contains growth factors like BDNF, GDNF, and TGF-β to promote neuronal survival, maturation, and cortical patterning [7].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: Harvest PSCs and aggregate them in low-attachment U-bottom plates to form uniform EBs in medium containing BMP4 and other morphogens. Critical Step: Use controlled cell numbers per well (e.g., 3,000-9,000 cells) to generate EBs of consistent size [7].

- Neural Induction: After 5-7 days, transfer EBs to neural induction medium. This step specifies the ectodermal lineage.

- Matrix Embedding: Around day 10-12, embed the neuroepithelial-containing EBs in droplets of Matrigel to provide support for complex 3D structure formation.

- Extended Suspension Culture: Transfer the embedded organoids to a spinning bioreactor or orbital shaker. Culture for several weeks to months, refreshing differentiation medium regularly. The dynamic culture improves nutrient/waste exchange and promotes healthier growth [10] [7].

- Patterning and Maturation: The medium can be supplemented with specific patterning factors (e.g., retinoic acid, FGF8) to guide regional identity (e.g., forebrain, midbrain). Long-term culture (3-6+ months) is required for the development of mature neuronal networks and layered structures.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in organoid culture, highlighting their role in controlling variability.

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Role in Reducing Variability |

|---|---|

| R-spondin 1 | Activates Wnt signaling, a master regulator for maintaining stemness in AdSC-derived organoids (e.g., gut, liver). Using recombinant protein from a consistent supplier reduces batch effects [8] [15]. |

| Noggin | Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) pathway antagonist. Essential for preventing spontaneous differentiation and promoting epithelial growth in intestinal and other organoid systems [8] [15]. |

| Defined Synthetic Hydrogels | Alternative to biologically derived Matrigel. Offers a chemically defined matrix with controllable stiffness and composition, drastically improving reproducibility [10]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables creation of isogenic control lines. This is the gold standard for controlling for genetic background when studying the functional impact of a specific mutation [13] [7]. |

| Microfluidic "Organ-on-Chip" Devices | Provides precise control over the microenvironment (shear stress, oxygen tension, compound gradients). Improves organoid maturation and function while enabling highly reproducible assay conditions [13] [10]. |

Visualizing Variability and Workflows

This diagram illustrates the primary sources of variability that arise from the two different starting paths of organoid generation.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Reproducible Organoid Culture

This flowchart outlines a generalized, controlled workflow for generating both PSC and AdSC-derived organoids, integrating key mitigation strategies.

The reproducibility of organoid differentiation research is fundamentally challenged by the use of ill-defined, animal-derived extracellular matrices (ECMs), with Matrigel being the most prominent example. As a basement membrane extract derived from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma, Matrigel possesses a complex and variable composition of structural proteins (primarily laminin, collagen IV, entactin, and perlecan), growth factors, and other bioactive molecules [16]. This inherent variability directly conflicts with the needs of robust scientific inquiry and reproducible therapeutic development, driving the urgent need for defined, animal-free alternatives.

FAQ: Understanding the Core Problem

Q1: What are the specific components of Matrigel that contribute to its batch-to-batch variability? Matrigel's variability stems from its biological origin and complex composition. Key variable components include:

- Structural Proteins: Laminin (~60%), Collagen IV (~30%), Entactin (~8%), and Perlecan (2-3%) [16]. The exact ratios and isoforms of these proteins can fluctuate.

- Growth Factors: Contains variable amounts of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), and other tumor-derived factors [16].

- Enzymes: Includes matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which can differentially influence cell behavior [16].

Q2: How does ECM variability experimentally impact organoid differentiation and growth? Variability in Matrigel directly translates to inconsistent experimental outcomes:

- Differentiation Efficiency: Fluctuations in growth factor concentrations can alter stem cell differentiation trajectories, leading to inconsistent organoid formation and maturation [16].

- Growth Metrics: Studies report significant yield variations; for instance, gastrointestinal organoids showed up to a fivefold increase in yield when a consistent integrin-activating signal (scTS2/16) was provided in a defined matrix [17].

- Morphological Phenotypes: Changes in mechanical properties (stiffness, porosity) can affect organoid architecture, such as crypt-villus formation in intestinal organoids [18].

Q3: What are the primary ethical and translational concerns associated with animal-derived reagents?

- Xenogenic Contamination: The mouse tumor origin introduces non-human antigens that can trigger immune responses, making Matrigel-derived organoids unsuitable for clinical transplantation [17] [19].

- Ethical Sourcing: Production involves the propagation of tumors in mice, raising concerns under the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) principle for animal welfare [20] [21].

- Clinical Translation: The undefined nature and animal origin prevent the use of Matrigel in manufacturing therapies for human patients, creating a significant translational barrier [19] [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating Variability in Your Research

Problem: Inconsistent Organoid Differentiation Yields

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Batch-to-Batch Variability of Matrigel | - Record lot numbers for all experiments.- Perform a pilot differentiation assay with a new lot.- Quantify key markers (e.g., Ki67 for proliferation) across batches. | - Transition to a defined synthetic hydrogel (e.g., PEG, fibrin) [19] [16].- If Matrigel is essential, pre-test and reserve a large batch for a single project. |

| Inconsistent Integrin-Mediated Signaling | - Use flow cytometry to analyze β1 integrin expression in organoid cells.- Test adhesion to specific ECM ligands (e.g., Laminin-111, Collagen I). | - Supplement culture medium with an integrin activator like single-chain scTS2/16 (1-10 µg/mL) to standardize pro-adhesive signals [17]. |

| Suboptimal Matrix Stiffness | - Use rheometry to characterize hydrogel mechanical properties.- Correlate organoid morphology with measured stiffness. | - Use a tunable synthetic matrix (e.g., PEG, PIC) and optimize the stiffness to match the native tissue (e.g., ~0.5-2 kPa for intestinal epithelium) [18] [16]. |

Problem: Poor Reproducibility of Drug Screening Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Defined ECM Sequesters Drugs | - Run a standard curve of a fluorescently tagged drug to measure its binding/partitioning within the matrix. | - Switch to an animal-free hydrogel with a defined, low-protein-binding composition, such as certain PEG or peptide hydrogels [20]. |

| Lack of Human-Relevant Cell-ECM Context | - Validate that key human-relevant receptors (e.g., specific integrin pairs) are engaged and functional. | - Use a human-derived recombinant matrix (e.g., recombinant Laminin-521, Fibrin) to create a more physiologically accurate context [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents that facilitate the transition to more reproducible organoid cultures.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Defined Organoid Culture

| Reagent | Function & Utility | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| scTS2/16 (single-chain antibody) | Allosterically activates β1 integrins, potentiating integrin-ECM signaling and supporting growth in defined matrices like Collagen I [17]. | Added to organoid medium (1-10 µg/mL) to boost yield in Matrigel and enable growth in Collagen I hydrogels [17]. |

| Vitronectin (Recombinant Human) | A defined, xeno-free substrate for 2D culture and expansion of hiPSCs, maintaining pluripotency for subsequent differentiation [19]. | Used as a coating for hiPSC culture before 3D organoid differentiation, supporting high-quality vascular organoid generation [19]. |

| Fibrin Hydrogel | A clinically relevant, animal-free hydrogel formed from fibrinogen and thrombin; supports angiogenesis and cell sprouting [19]. | Used as a 3D matrix for hiPSC-derived blood vessel organoid culture, promoting vascular network formation comparable to Matrigel [19]. |

| Functionalized PEG Hydrogels | Synthetic, tunable hydrogels that can be modified with adhesion peptides (e.g., RGD, GFOGER) and designed to be protease-degradable [16]. | Used for assembling intestinal, lung, and kidney organoids; stiffness and biochemical cues can be precisely controlled [16]. |

| PeptiMatrix | A synthetic peptide hydrogel; screening identified it as supporting good metabolic competence in HepaRG liver cells under perfusion [20]. | A potential candidate for xenobiotic metabolism studies in liver-organ-on-chip models [20]. |

Standardized Protocols for Enhanced Reproducibility

This protocol replaces Matrigel with a defined, animal-free system.

Workflow:

Key Materials:

- hiPSCs (e.g., clone UKKi032-C)

- Recombinant Human Vitronectin XF (for 2D coating)

- Fibrinogen (from human plasma, lyophilized powder)

- Thrombin (from human plasma)

- Vascular Organoid Differentiation Media [19]

Detailed Steps:

- hiPSC Maintenance (Days -5 to 0): Culture and expand hiPSCs on Vitronectin-coated plates in essential 8 medium. Passage cells every 5-6 days upon reaching 80-90% confluency using EDTA.

- Initiate Differentiation (Days 0-13): Follow established 2D differentiation protocols to direct hiPSCs toward a mesodermal lineage. This typically involves switching to media containing BMP4, CHIR99021 (a GSK-3β inhibitor), and VEGF.

- Prepare Fibrin Hydrogel (Day 13): a. Dissolve fibrinogen in cell culture-grade PBS to a final concentration of 5 mg/mL. b. Prepare a thrombin solution at 2 U/mL in 40 mM CaCl₂ solution. c. Combine the fibrinogen and thrombin solutions at a 1:1 ratio in a pre-warmed culture plate and mix gently. d. Allow the mixture to polymerize for 30-60 minutes at 37°C to form a gel.

- 3D Organoid Culture (Days 13-21): a. After initial differentiation, harvest the cell aggregates and resuspend them in the fibrinogen solution before mixing with thrombin, or seed them directly on top of the pre-polymerized fibrin gel. b. Culture the embedded aggregates in vascular organoid differentiation media, changing the media every 2-3 days.

- Analysis (Day 21+): Harvest organoids for analysis. Fix and immunostain for endothelial marker CD31 (PECAM-1) and mural cell marker PDGFrβ to confirm the formation of vascular networks.

This protocol uses a defined integrin activator to improve the performance of a simple, clinically relevant matrix.

Workflow:

Key Materials:

- Primary human intestinal organoids

- Collagen I Hydrogel (e.g., rat tail or recombinant human source)

- Purified scTS2/16 protein (single-chain variable fragment)

- Standard organoid growth medium (containing EGF, R-spondin, Noggin, etc.)

Detailed Steps:

- Organoid Maintenance: Expand human gastrointestinal organoids (e.g., colon, ileum) using standard methods in Matrigel domes with complete growth medium.

- Preparation for Assay: Passage organoids by mechanically breaking them into small fragments and harvesting.

- Collagen I Hydrogel Preparation: On ice, mix Collagen I solution with neutralization solution and PBS according to the manufacturer's instructions to achieve a final concentration of 2-4 mg/mL.

- Experimental Setup: a. Test Condition: Supplement the standard organoid growth medium with 1-10 µg/mL of scTS2/16. b. Control Condition: Use standard organoid growth medium without supplementation.

- 3D Embedding and Culture: a. Mix the organoid fragments with the neutralized Collagen I solution. b. Pipet the mixture into a pre-warmed culture plate and allow it to gel for 20-30 minutes at 37°C. b. Overlay the polymerized gel with the corresponding media (with or without scTS2/16).

- Analysis: After 5-7 days, quantify organoid growth and viability. A cellular ATP assay can be used, which demonstrated a six- to sevenfold increase in yield for gastrointestinal organoids grown in Collagen I with scTS2/16 compared to untreated controls [17].

Quantitative Comparison of ECM Performance

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Matrigel and Alternative Matrices

| Matrix / Material | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance in Organoid Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Matrigel | Mouse sarcoma-derived, complex, undefined, high batch variability. | Considered the "gold standard" but yields variable results. Baseline for comparison. |

| Collagen I + scTS2/16 | Defined protein, clinically relevant, activated by integrin antibody. | 6-7x increase in yield of GI organoids vs. Collagen I alone [17]. |

| Fibrin Hydrogel | Human-derived, defined, animal-free, pro-angiogenic. | Supports vascular organoid differentiation and endothelial sprouting comparable to Matrigel [19]. |

| Vitronectin (2D Coating) | Recombinant human, xeno-free, defined. | Supports hiPSC pluripotency and subsequent differentiation with no significant differences from Matrigel [19]. |

| Functionalized PEG | Synthetic, highly tunable, chemically defined. | Supports assembly of intestinal, renal, and lung organoids; performance is equivalent or superior to Matrigel in specific contexts [16]. |

| PeptiMatrix | Synthetic peptide hydrogel, defined. | Supports HepaRG cell proliferation and shows promising metabolic competence in MPS [20]. |

The Consequences of Variability for Disease Modeling and High-Throughput Screening

Organoid technology has emerged as a transformative tool in biomedical research, enabling the creation of three-dimensional, self-organizing structures that recapitulate key aspects of human organ development, physiology, and disease. Unlike traditional two-dimensional cell cultures, organoids preserve tissue architecture and cellular heterogeneity, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and personalized medicine. However, the full potential of organoids is constrained by significant challenges related to variability, which profoundly impacts experimental reproducibility, data interpretation, and translational applications. This technical support center addresses the critical issue of batch-to-batch variability in organoid differentiation research, providing troubleshooting guidance and practical solutions to enhance experimental robustness for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of batch-to-batch variability in organoid cultures? Batch-to-batch variability in organoid systems arises from multiple sources, including:

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Inconsistencies: Matrigel, the most commonly used ECM, exhibits significant batch-to-batch variation in its mechanical and biochemical properties due to its tumor-derived nature [10] [22].

- Reagent Quality: Variations in growth factor concentrations, purity, and activity between different lots of essential signaling molecules like Wnt, R-spondin, and Noggin [8] [23].

- Stem Cell Source Differences: Genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity in both pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and tissue-derived stem cells (TSCs) across different donors and passages [8] [7].

- Protocol Implementation: Manual processing steps, including cell seeding density, passaging techniques, and differentiation timing, introduce operator-dependent variability [10] [23].

- Environmental Factors: Subtle fluctuations in temperature, CO₂ levels, and medium pH during culture and differentiation processes [23].

2. How does variability impact high-throughput screening (HTS) outcomes? Variability in organoid systems significantly compromises HTS reliability through:

- Reduced Statistical Power: Increased inter-batch variation necessitates larger sample sizes to achieve statistical significance, escalating costs and time [24].

- False Positives/Negatives: Uncontrolled variability can obscure genuine biological signals or create artificial hits in drug screens [24] [25].

- Irreproducible Results: Inconsistent organoid differentiation states between batches lead to poor reproducibility of screening outcomes across laboratories [24] [23].

- Impaired Data Interpretation: Heterogeneity in organoid size, cellular composition, and maturation state complicates the interpretation of dose-response relationships and mechanism of action studies [10] [24].

3. What strategies can minimize variability in organoid differentiation?

- Standardization and Automation: Implementing robotic liquid handling systems for consistent media changes, cell passaging, and drug administration [10] [23].

- Defined Culture Components: Transitioning to synthetic hydrogels with controlled mechanical properties and composition to replace variable Matrigel [10] [22].

- Quality Control Measures: Establishing rigorous batch testing of critical reagents and regular karyotyping to monitor genetic stability [8] [23].

- Process Documentation: Maintaining detailed records of passage numbers, differentiation timelines, and reagent lot numbers for better traceability [23].

4. How can I assess and quantify variability in my organoid models?

- Morphological Analysis: High-content imaging to quantify organoid size, shape, and budding patterns across batches [10] [26].

- Molecular Characterization: Regular transcriptomic (RNA-seq) and proteomic profiling to monitor differentiation efficiency and cellular composition [8] [7].

- Functional Assays: Benchmarking organoid responses to reference compounds with known effects to assess pharmacological consistency [24] [25].

- Statistical Methods: Implementing analysis of variance (ANOVA) to partition variability sources and identify major contributors [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Differentiation Outcomes Between Batches

Symptoms: Variable proportions of target cell types, differing morphological patterns, inconsistent functional responses to stimuli.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent ECM lots | Transition to synthetic hydrogels; pre-test Matrigel lots; standardize polymerization protocols | Measure organoid formation efficiency; assess structural integrity |

| Variable growth factor activity | Implement quality control checks for new reagent lots; use recombinant proteins instead of conditioned media | Perform dose-response assays with reference compounds |

| Stem cell passage number drift | Establish strict passage number limits; maintain comprehensive cell lineage tracking | Regular flow cytometry for stem cell markers; karyotyping |

| Uncontrolled differentiation timing | Standardize induction protocols with precise timing; use inducible genetic systems | Immunofluorescence for stage-specific markers at fixed time points |

Problem: High Well-to-Well Variability in High-Throughput Screening

Symptoms: High coefficient of variation in assay readouts, poor Z-factor values, inconsistent dose-response curves.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent organoid seeding | Use automated dispensing systems; optimize cell concentration per well | Microscopic examination of distribution immediately after seeding |

| Edge effects in multi-well plates | Use specialized plates designed to minimize evaporation; include edge well controls | Compare central vs. edge well performance in control treatments |

| Variable organoid size and maturity | Implement size-based sorting before screening; standardize differentiation duration | Image analysis to quantify size distribution before assay |

| Inadequate assay normalization | Include multiple internal controls; use viability assays normalized to cell number | Calculate Z-factor using positive and negative controls |

Experimental Protocols for Variability Assessment

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of Batch-to-Batch Variability

Purpose: To systematically quantify and document sources of variability in organoid differentiation.

Materials:

- Organoid cultures from at least three different batches

- Quality-controlled ECM components

- Standardized growth media with documented lot numbers

- High-content imaging system

- RNA extraction and qPCR reagents

- Multiplex immunofluorescence staining reagents

Procedure:

- Parallel Differentiation: Initiate organoid differentiation from the same stem cell source across three separate batches, spaced one week apart.

- Sample Collection: At defined differentiation timepoints (e.g., days 7, 14, 21), collect organoids for analysis.

- Morphometric Analysis: Acquire bright-field images of 30-50 organoids per batch. Quantify size (area, diameter), circularity, and budding patterns using image analysis software.

- Molecular Characterization: Extract RNA and perform qPCR for lineage-specific markers. Perform immunofluorescence for 2-3 key protein markers.

- Data Analysis: Calculate coefficients of variation for each parameter across batches. Use ANOVA to partition variance components.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol generates quantitative metrics of batch-to-batch variability and identifies which differentiation parameters show the greatest inconsistency.

Protocol 2: Validation of Organoid Assays for High-Throughput Screening

Purpose: To establish the robustness of organoid-based assays before implementing large-scale screens.

Materials:

- Minimum 3 batches of mature organoids

- Reference compounds with known effects (both positive and negative controls)

- Automated liquid handling system

- Appropriate assay reagents (viability, functional readouts)

- Multi-well plates optimized for 3D cultures

Procedure:

- Plate Validation: Test different plate types for organoid attachment, medium evaporation, and edge effects using non-treated organoids.

- DMSO Tolerance: Determine maximum DMSO concentration that doesn't affect organoid viability (typically <0.5%).

- Assay Window Determination: Treat organoids with positive and negative control compounds in 8 replicates across 3 separate batches.

- Z-factor Calculation: Calculate Z-factor using the formula: 1 - [(3σc+ + 3σc-)/|μc+ - μc-|], where σ=standard deviation and μ=mean of positive (c+) and negative (c-) controls.

- Inter-batch Concordance: Compare IC₅₀ values for reference compounds across batches.

Acceptance Criteria: Z-factor >0.5, coefficient of variation <20%, and less than 2-fold variation in IC₅₀ values between batches.

Signaling Pathways in Organoid Differentiation and Variability

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways governing organoid differentiation and how their perturbation contributes to variability:

Key Signaling Pathways in Organoid Differentiation and Variability

Research Reagent Solutions for Variability Reduction

The following table details essential materials and their functions in minimizing variability in organoid research:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Organoid Culture | Variability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defined Matrices | Synthetic PEG-based hydrogels, GelMA | Replace biologically variable Matrigel; provide controlled mechanical and biochemical cues | Consistent polymer composition; tunable stiffness; defined degradation profiles |

| Recombinant Growth Factors | Wnt3a, R-spondin 1, Noggin, EGF | Direct stem cell fate decisions and maintain progenitor populations | Manufacturer quality controls; activity-based dosing; absence of contaminating proteins |

| Chemically Defined Media | STEMCELL technologies IntestiCult, mTeSR | Provide consistent nutrient and signaling molecule composition | Lot-to-lot consistency; absence of animal-derived components; optimized formulations |

| Quality Control Kits | Mycoplasma detection, pluripotency verification, viability assays | Monitor culture health and stem cell quality | Standardized thresholds for acceptance; regular testing schedule |

| Automation Systems | Robotic liquid handlers, automated passaging systems | Reduce operator-dependent variability in routine culture procedures | Programming consistency; regular calibration; minimal technical variation |

Quantitative Data on Screening Variability

The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics relevant to variability assessment in organoid-based screening:

| Variability Parameter | Acceptable Range | Problematic Range | Impact on HTS | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organoid Size CV | <15% | >25% | Altered compound penetration; variable response | Image analysis of diameter distribution |

| Differentiation Marker CV | <20% | >35% | Inconsistent target expression; variable pharmacology | Flow cytometry or qPCR for lineage markers |

| Viability Assay Z-factor | >0.5 | <0.3 | Inability to distinguish hits from noise | Positive/Negative control comparison |

| IC₅₀ Fold Variation | <2-fold | >3-fold | Unreliable potency rankings | Dose-response curves across batches |

| Edge Effect CV | <15% | >25% | Position-dependent artifacts | Center vs. edge well comparison |

Workflow for Variability Mitigation in Organoid Screening

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow to identify and address variability sources in organoid-based screening:

Systematic Workflow for Variability Mitigation

Standardized Protocols and Advanced Engineering Solutions

Implementing cGMP-Grade and Xeno-Free Reagents for Enhanced Consistency

What are cGMP-grade reagents and why are they critical for organoid research?

cGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practice) refers to regulations enforced by the FDA that provide systems for proper design, monitoring, and control of manufacturing processes and facilities [27]. For reagents, cGMP compliance means they are produced under stringent quality controls that assure identity, strength, quality, and purity. In organoid research, this translates to reduced batch-to-batch variability and enhanced experimental consistency [28]. The "C" in cGMP stands for "current," requiring manufacturers to use technologies and systems that are up-to-date to prevent contamination, mix-ups, and errors [27].

How do xeno-free reagents differ from standard research-grade reagents?

Xeno-free reagents are manufactured without any animal-derived components, eliminating the risk of contamination from animal pathogens and reducing variability caused by undefined serum components [28]. Standard research-grade reagents often contain animal sera, proteins, or other components that introduce undefined variables and increase lot-to-lot variation. The shift to xeno-free formulations is particularly important for clinical applications where reproducibility and safety are paramount [29].

What regulatory standards apply to cGMP reagents?

cGMP regulations for drugs are covered in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations, particularly parts 210, 211, and 600 for biological products [30]. Importantly, not all cGMP standards are equal - some suppliers manufacture under medical device cGMP standards, which are suitable for viral vector manufacturing but not for direct human administration, while pharmaceutical cGMP guidelines are more prescriptive and suitable for therapies administered to humans [31]. Regulatory bodies require that cGMP manufacturing assures proper design, monitoring, and control of manufacturing processes and facilities [27].

Essential Reagent Selection and Validation

Research Reagent Solutions Table

Table 1: Key cGMP-Grade Reagents for Organoid Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Organoid Differentiation | cGMP Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors | HumanKine FGF-2, BMP-4, Activin A [28] | Guide pluripotent stem cell differentiation toward specific lineages | Native human post-translational modifications, animal component-free (ACF) production, biological activity testing |

| Cell Culture Media | Human Essential 8, MEM-alpha with CTS KnockOut SR [29] | Support stem cell expansion and maintenance | Certificate of analysis for human pathogens, sterility testing, endotoxin levels |

| Extracellular Matrices | rhLaminin-521, human collagen types I/III [29] | Provide 3D scaffolding for organoid self-organization | Testing for human pathogens, composition verification, purity assessment |

| Reprogramming Factors | CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit [29] | Generate patient-specific iPSCs | Testing for contaminants, sterility verification, potency validation |

| Dissociation Reagents | TrypLE Express [29] | Gentle cell dissociation for passaging | Xeno-free formulation, proteolytic activity standardization |

| Antibodies | CoraLite conjugated antibodies for characterization [28] | Organoid characterization and quality control | Validation in organoid models, specificity confirmation, lot-to-lot consistency |

What documentation should I require for cGMP reagent validation?

When implementing cGMP-grade reagents, you should obtain and review the following documentation:

- Certificate of Analysis (CoA): Provides batch-specific quality control data including identity, purity, potency, and safety testing results [29] [28]

- Traceability Documentation: Complete records of manufacturing conditions, equipment, and personnel training for each batch [31]

- Pathogen Testing Results: Verification that reagents are free from human pathogens, particularly critical for reagents of animal or human origin [29]

- Sterility and Endotoxin Testing: Evidence that reagents meet specified limits for microbial contamination and endotoxin levels [29]

How do I qualify a new supplier for cGMP xeno-free reagents?

Supplier qualification should include:

- Audit of Manufacturing Facilities: Verify cGMP compliance through facility audits or audit reports [27]

- Review of Quality Management Systems: Assess the supplier's change control procedures, deviation management, and corrective action systems [27]

- Testing of Multiple Lots: Evaluate at least 3-5 lots for consistency in performance and specifications [28]

- Validation in Your System: Test reagents in your specific organoid differentiation protocol to confirm performance claims [28]

Experimental Design and Workflows

cGMP-Compliant Organoid Differentiation Workflow

Diagram 1: cGMP organoid differentiation workflow.

What are the key steps in establishing a cGMP-compliant organoid differentiation protocol?

Based on successful implementation for retinal organoids [29]:

- Patient-Specific Cell Source Establishment: Obtain 3mm skin biopsies and establish fibroblast lines under ISO class 5 cGMP conditions using xeno-free biopsy media (IxMedia) [29]

- iPSC Generation Under cGMP: Use non-integrating Sendai viral vectors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) at MOI of 3 in serum-free media with ROCK inhibitor [29]

- 3D Differentiation Protocol: Employ stepwise cGMP-compliant 3D differentiation rather than 2D systems for better cellular enrichment and tissue organization [29]

- Quality Control Checkpoints: Implement rigorous testing at each stage including pluripotency validation, karyotyping, and differentiation marker assessment [29]

How do I transition from research-grade to cGMP-grade reagents in an existing protocol?

A systematic transition approach includes:

- Component-by-Component Replacement: Substitute one reagent at a time while maintaining others constant to assess impact [28]

- Side-by-Side Testing: Compare organoid differentiation efficiency, maturity markers, and batch consistency between old and new reagents [28]

- Protocol Optimization: Adjust concentrations and timing since cGMP-grade reagents often have higher specific activity [28]

- Documentation Updates: Revise standard operating procedures (SOPs) to reflect new reagent specifications and quality controls [27]

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Inconsistent organoid differentiation between batches

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Variability in growth factor biological activity

- Solution: Use GMP-grade human cell-derived growth factors (HumanKine) with proper post-translational modifications rather than bacterial-derived factors [28]

- Cause: Lot-to-lot matrix variability

- Solution: Implement cGMP-grade defined extracellular matrices with comprehensive CoA review before use [29]

- Cause: Inconsistent cell seeding density

- Solution: Standardize dissociation protocols with cGMP-grade enzymes and automated cell counting [29]

Problem: Low efficiency in iPSC generation for patient-specific organoids

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Reprogramming Factor Quality: Ensure cGMP-grade Sendai viral vectors have been properly stored and are within expiration date [29]

- Optimize Culture Conditions: Use cGMP-grade laminin-521 coatings and Essential 8 media during reprogramming [29]

- Implement Quality Control Early: Validate fibroblast line quality before reprogramming attempt [29]

Problem: Contamination issues despite using cGMP reagents

Investigation and Resolution:

- Review Reagent Certificates: Confirm sterility and endotoxin testing results for all media components [29]

- Audit Handling Procedures: Ensure aseptic technique is maintained even with cGMP reagents [27]

- Verify Equipment Maintenance: Confirm that incubators, biosafety cabinets, and other equipment are properly maintained and calibrated [27]

Quality Control and Validation Methods

What quality control tests are essential for consistent organoid differentiation?

Table 2: Essential Quality Control Measures for Organoid Consistency

| QC Parameter | Testing Method | Acceptance Criteria | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Marker Expression | Immunofluorescence for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG [28] | >90% positive cells | Each iPSC batch |

| Organoid-Specific Markers | CoraLite conjugated antibodies for high-content imaging [28] | Expression pattern matching reference standards | Each differentiation |

| Secreted Biomarkers | AuthentiKine ELISA kits [28] | Within established reference ranges | Periodic validation |

| Genetic Stability | Karyotyping or SNP analysis | Normal euploid karyotype | Every 10 passages |

| Sterility | Microbial culture testing | No microbial growth | Each batch for release |

| Viability and Cell Count | Automated cell counting | >85% viability | At each passage |

How do I establish acceptance criteria for organoid quality?

Developing appropriate acceptance criteria involves:

- Reference Standard Establishment: Create master cell banks and reference organoids with comprehensive characterization [28]

- Historical Data Analysis: Use data from successful differentiations to establish statistical ranges for key parameters [28]

- Functional Correlations: Link molecular markers to functional outcomes where possible (e.g., electrophysiology for neuronal organoids) [29]

- Regulatory Alignment: Ensure criteria meet expectations for intended application (research vs. clinical use) [27]

Regulatory and Commercial Considerations

How does the regulatory landscape impact reagent selection?

The regulatory environment continues to evolve with important considerations:

- FDA Modernization Act 2.0: Allows use of innovative non-animal methods, including organoids, for drug development [32]

- Increasing Scrutiny: Pharmaceutical quality control market is growing at 10.4% CAGR, reflecting heightened focus on quality systems [33]

- Global Harmonization: While cGMP is FDA-focused, similar frameworks exist globally (EU GMP, PIC/S) that may affect international collaborations [30]

What are the cost implications of implementing cGMP-grade reagents?

While cGMP-grade reagents typically have higher upfront costs, they provide significant long-term benefits:

- Reduced Batch Failure: Improved consistency decreases costly experimental repeats [28]

- Regulatory Efficiency: Simplified IND submissions with properly characterized reagents [27]

- Time Savings: Reduced troubleshooting and optimization time with more predictable performance [28]

The organoid market is expected to reach $15.01 billion by 2031, reflecting increased investment and standardization in the field [32]. The laboratory reagents market growth (projected to reach $13.27 billion by 2031) further indicates the expanding availability of quality-controlled reagents [34].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

How are cGMP organoids being used in drug development and personalized medicine?

Advanced applications include:

- Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs): For personalized treatment screening and prediction of individual patient responses [32]

- Disease Modeling: Recapitulation of disease phenotypes like enhanced S-cone phenotype in NR2E3 mutations retinal organoids [29]

- Toxicity Testing: Serving as more human-relevant alternatives to animal testing for safety assessment [32]

What emerging technologies will impact cGMP organoid research?

Future developments focus on addressing current limitations:

- Vascularization: Co-culture with endothelial cells to improve nutrient delivery and organoid maturity [32]

- Organ-on-Chip Integration: Combining organoids with microfluidic systems for improved physiological relevance [32]

- Automation and AI: Addressing reproducibility challenges through standardized production and analysis [32]

- Multi-omic Characterization: Comprehensive profiling to better qualify organoids and their responses [32]

Implementing cGMP-grade and xeno-free reagents represents a critical step toward achieving the reproducibility required for both basic research and clinical applications of organoid technology. As the field continues to mature, these quality foundations will enable more predictive disease modeling and successful translation to therapeutic applications.

Automation and High-Throughput Bioprocesses for Scalable, Uniform Production

FAQs: Troubleshooting Uniform Organoid Production

Q1: Our automated system produces organoids with high heterogeneity in size and structure. What are the primary causes?

Heterogeneity in automated organoid cultures often stems from three main areas:

- Inconsistent Initial Seeding: Variability in the number of cells, cell type proportions, or extracellular matrix distribution at the start of the process is a major contributor [10].

- Stochastic Self-Assembly: The innate, poorly controlled morphogenesis during self-assembly introduces natural variation [10].

- Process Parameter Fluctuations: Inconsistent control over critical process parameters such as temperature, pH, and agitation speed can lead to batch-to-batch differences [35]. Using automated liquid handling systems with uncalibrated or imprecise volume transfers can also directly impact reagent concentrations and subsequent organoid development [36].

Q2: When using automated liquid handlers, what common errors should we monitor for to ensure reagent consistency?

Automated liquid handlers, while essential for throughput, are potential sources of error.

- Tip-Related Issues: Using non-vendor-approved disposable tips can lead to variations in volume delivery due to differences in fit, wettability, or internal residue [36]. For fixed tips, inadequate washing protocols can cause reagent carryover and contamination [36].

- Sequential Dispensing Inaccuracies: When a large volume is aspirated and dispensed sequentially across a plate, the first and last dispenses may transfer different volumes [36].

- Inefficient Mixing: In serial dilution protocols, a failure to achieve homogeneous mixing before the next transfer leads to incorrect reagent concentrations [36].

- Software Parameter Errors: Incorrectly defined variables in the software, such as aspirate/dispense rates, tip immersion depth, or liquid class settings, can significantly impact performance [36].

Q3: What in-process monitoring tools can help detect deviations in organoid quality early in the production cycle?

Implementing non-invasive, in-process monitoring is key to early detection.

- Quantitative Morphological Analysis: Using advanced image-processing and machine learning on time-course microscopic images allows for the quantitative measurement of cell morphological profiles. This can discriminate deviated samples in real-time and predict outcomes like growth rate with high accuracy [37].

- Advanced Analytical Tools: Technologies like high-content imaging, multi-electrode arrays, and integrated biosensors enable dynamic, functional monitoring of organoids in a high-throughput manner [10] [38]. These can provide data on biophysical stability, particle formation, and metabolic activity.

Q4: How can we reduce contamination risks in high-throughput, automated bioreactors?

Contamination control is critical for scalable production.

- Closed and Single-Use Systems (SUS): Implementing closed, single-use bioreactors drastically reduces contamination risks from reusable culture vessels and complex cleaning validation processes [39].

- Validated Filtration: Use validated 0.1–0.2 µm filters for all media and buffer streams to ensure sterility [39].

- Rigorous Environmental Monitoring: In GMP-like environments, strict cleanroom standards with HEPA filtration, proper gowning, and continuous monitoring of air quality and particle loads are essential [39].

- Color-Coded Zones: For manual handling steps (e.g., reagent preparation), implementing a color-coding system for tools and equipment separates processes and minimizes cross-contamination risks [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Organoid Maturity and Function

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Protocol for Verification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited maturation; failure to recapitulate full adult organ function [10] | Lack of key cell types (e.g., immune cells, mesenchymal cells) [10] | Co-culture strategies; incorporate stromal and immune components during the seeding process [10]. | Differentiate organoids with and without co-culture. Analyze for mature cell markers (e.g., functional hepatocytes in liver organoids) via qPCR and immunostaining. |

| Limited survival time & central necrosis [10] | Inadequate vascularization; limited nutrient/O2 diffusion [10] | Engineer vasculature by incorporating endothelial cells; use oscillating cultures to improve nutrient access [10]. | Compare long-term viability (>30 days) of standard vs. vascularized organoids. Measure the necrotic core area via histology. |

| Lack of physiological responses [10] | Absence of key microenvironmental cues (mechanical, electrical) [10] | Integrate organoids-on-chips to apply mechanical force stimulation (e.g., fluid shear stress) or electrical stimulation [10]. | Culture organoids in a microfluidic chip under perfusion. Assess functional output (e.g., albumin secretion for liver, electrical activity for neural organoids). |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Automated Equipment and High-Throughput Screening

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High well-to-well variability in 96-well plate assays [38] | Positional effects on the plate (e.g., edge evaporation) [38]; inaccurate liquid handling [36] | Optimize 96-well plate layout, randomize sample positions, and use internal controls. Calibrate liquid handlers regularly [38]. |

| Poor data reliability in High-Throughput Screening (HTS) [38] | Inefficient mixing in microplates; suboptimal assay conditions [36] | Validate mixing efficiency on the automated platform. Use Design of Experiments (DOE) to systematically optimize assay parameters (e.g., cell density, reagent concentration) [35] [38]. |

| Increased false positives/negatives in screening [36] | Liquid handler over- or under-dispensing critical reagents [36] | Implement a regular calibration and verification program for all liquid handlers using standardized platforms to ensure volume transfer accuracy and precision [36]. |

Experimental Workflow for Quality Control

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for integrating in-process monitoring and troubleshooting into an automated organoid production system.

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Engineered Organoid Culture

| Item | Function in Process | Key Consideration for Scalability |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Matrices [10] [41] | Provides a defined 3D scaffold for stem cell growth and self-organization; replaces variable, natural-derived hydrogels like Matrigel. | Reduces batch-to-batch variability of the extracellular environment, crucial for reproducible, large-scale production [10]. |

| R-Spondin & Wnt Agonists [41] | Critical soluble factors for maintaining stemness and driving the growth of certain organoid types (e.g., intestinal). | Use of recombinant proteins ensures defined, consistent quality. Concentration must be precisely controlled by automated systems [36]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Device [10] | Microfluidic platform providing precise control over the microenvironment (shear stress, gradients). | Enables high-throughput culture and functional maturation of organoids under perfused conditions [10]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler [38] [36] | Performs precise, high-volume tasks: cell seeding, media exchange, feeding, and reagent dispensing. | Regular calibration is mandatory. Using vendor-approved tips prevents volume transfer errors that compromise reproducibility [36]. |

| Microplate Readers with HTS [38] | Allows for high-throughput, non-invasive metabolic and functional assays (e.g., ELISA, FRET) directly in culture plates. | Integrated with robotic systems for fully automated screening and data collection, enabling rapid decision-making [38]. |

The pursuit of reduced batch-to-batch variability stands as a central thesis in modern organoid differentiation research. A primary source of this variability lies in the inconsistent application of morphogens—diffusible signaling molecules that guide cell fate decisions by forming concentration gradients. These gradients, including Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), Wnt, BMPs, FGFs, and Retinoic Acid (RA), activate specific transcription factors in a concentration-dependent manner to establish spatial and temporal identity in progenitor cells [42]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers overcome the most common challenges in achieving precise morphogen control, thereby enhancing the reproducibility and reliability of their differentiation protocols.

Foundational Concepts: How Morphogen Gradients Pattern Tissues

Core Principles of Morphogen-Mediated Patterning

Morphogens are secreted signaling molecules that diffuse from a localized source to form a concentration gradient across a developing tissue. Cells respond to specific threshold concentrations of these morphogens, activating distinct gene regulatory networks that determine their ultimate fate [42]. This process partitions tissues into precise spatial domains, a classic example being the dorso-ventral patterning of the neural tube. Here, SHH secreted from the notochord and floor plate ventralizes the neural tube, while BMP and Wnt signaling from the overlying ectoderm pattern the dorsal side [42]. The mutual repression between transcription factors induced by these opposing gradients, such as Nkx2.2/Nkx6.1 versus Pax3/Pax7, helps sharpen the boundaries between progenitor domains [42].

Visualizing Morphogen Gradient Patterning

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling logic of neural tube patterning by opposing morphogen gradients, a fundamental model for understanding guided differentiation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Excessive Differentiation in Cultures

- Problem: High levels (>20%) of spontaneous differentiation in pluripotent stem cell cultures prior to induced differentiation.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Old Culture Medium: Ensure complete cell culture medium kept at 2-8°C is less than 2 weeks old [43].

- Prolonged Incubator Time: Avoid having the culture plate out of the incubator for more than 15 minutes at a time [43].

- Colony Overgrowth: Passage cultures when the majority of colonies are large and compact with dense centers, before they overgrow [43].

- Improper Aggregate Size: Ensure cell aggregates generated after passaging are evenly sized; decrease colony density by plating fewer aggregates [43].

- Sensitive Cell Lines: For ReLeSR passaging, reduce incubation time if your cell line is particularly sensitive [43].

Inconsistent Morphogen Gradient Formation

- Problem: Poor reproducibility of differentiation outcomes due to gradient variability.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Molecular Noise: Recognize that gradient variability arises from natural noise in morphogen production, transport, and decay [44].

- Precision Limits: Understand that single gradients can yield patterning precision of 1-3 cell diameters in neural tube development, which may be sufficient without requiring simultaneous readout of opposing gradients [44].

- Amplitude Independence: Note that progenitor domain sizes can be more robust than boundary positions, as gradient amplitude changes may not affect interior domain sizes [44].

- Technical Measurement: Avoid overestimating positional error by using direct measurement methods rather than fitting exponential functions to mean gradient data [44].

Organoid Size Control Issues

- Problem: Organoids growing too large, developing necrotic cores.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Size Limit: Actively maintain organoids under 500 μm in diameter, as they lack vascular systems [45].

- Passaging Schedule: Passage organoids every 5-10 days when they reach 100-200 μm in diameter [45].

- Nutrient Diffusion: Recognize that in larger organoids, core cells are deprived of sufficient oxygen and nutrients due to limited diffusion, leading to central cell death [45].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Morphogen and Patterning Questions

Q: What are the key morphogens involved in neural tube patterning, and how do they interact? A: The primary morphogens include SHH (ventralizing), BMP/Wnt (dorsalizing), FGFs, and Retinoic Acid (caudalizing). These form opposing gradients that establish discrete progenitor domains through concentration-dependent activation of transcription factors and mutual repression between downstream targets [42].

Q: How precise are natural morphogen gradients in developing tissues? A: Studies in mouse neural tubes show gradient precision of approximately 1-3 cell diameters for central progenitor domain boundaries. Single gradients can achieve this precision without requiring simultaneous readout of opposing gradients, contrary to some previous estimates [44].

Q: Can the same morphogen elicit different responses at different developmental stages? A: Yes, morphogens are repurposed across time and space. For example, SHH from the floor plate induces ventral neural fates early on, while later secretion from the Zone of Polarizing Activity in the limb instructs digit patterning. The outcome depends on the basal gene expression program in receiving cells [42].

Protocol Optimization Questions

Q: How can I improve the reproducibility of my differentiation protocols? A: Focus on controlling key parameters: (1) Use high-quality pluripotent stem cells with >90% expression of pluripotency markers [46], (2) Standardize initial confluence to >95% at differentiation onset [46], (3) Use fresh medium supplements less than 2 weeks old [43], (4) Precisely time morphogen exposure windows, and (5) Consider implementing engineering approaches like bio-printing or bioreactors for more uniform culture conditions [47].

Q: What is the optimal size for organoids in differentiation experiments? A: Organoids should ideally be maintained under 500 μm in diameter to prevent necrotic core formation due to limited oxygen and nutrient diffusion. Most organoids are ready for passaging when they reach 100-200 μm in diameter [45].

Q: How many passages can organoids typically undergo? A: This depends on the source cell type, but most organoids can be passaged up to 10 times (>6 months) in vitro. Culture medium formulation also plays a role, with conditioned media often supporting longer-term expansion than fully defined synthetic media [45].

Quantitative Morphogen Parameters Table

Table 1: Key Parameters for Morphogen Gradient Control in Differentiation Protocols

| Morphogen | Primary Role in Patterning | Typical Concentration Range | Critical Timing Windows | Key Target Transcription Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) | Ventralization of neural tube | Varies by system; concentration gradients critical | Early neural specification; sustained for ventral fates | Nkx2.2, Nkx6.1, Olig2 [42] |

| BMP/Wnt | Dorsalization of neural tube | Gradient amplitude and decay length critical | Concurrent with SHH for dorsoventral axis | Pax3, Pax7, Pax6 [42] |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Caudalization, hindbrain and spinal cord identity | Caudal-to-rostral gradient | 5th gestational week in human development; refines HOX expression | Hox genes [42] |

| FGFs | Anterior patterning, midbrain-hindbrain boundary | Spatial separation critical | Early anterior patterning (FGF8, FGF17) | Otx2, Gbx2 [42] |

| Wnt Inhibitors (e.g., DKK1) | Anterior neural ridge specification | Maintain low Wnt signaling | Early forebrain specification | FoxG1 [42] |

Experimental Workflow for Controlled Differentiation

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for a differentiation protocol with emphasis on critical control points to minimize batch-to-batch variability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Controlled Differentiation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Differentiation | Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | mTeSR Plus, mTeSR1, Advanced DMEM/F12 | Foundation for culture medium; maintains pluripotency or supports differentiation | Keep at 2-8°C and use within 2 weeks for optimal performance [43] |

| Passaging Reagents | ReLeSR, Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | Dissociates cells while maintaining viability; critical for uniform aggregate formation | Adjust incubation time (1-2 minutes) based on cell line sensitivity [43] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Corning Matrigel, Vitronectin XF | Provides structural support and biochemical signals for cell attachment and differentiation | Ensure correct plate type: non-tissue culture-treated for Vitronectin XF; tissue culture-treated for Matrigel [43] |

| Morphogen Supplements | Recombinant SHH, BMPs, Wnts, FGFs, RA | Directs cell fate decisions through concentration-dependent activation of gene programs | Use fresh aliquots; precise timing and concentration critical for reproducible patterning [42] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), CHIR99021 (Wnt activator) | Enhances cell survival after passaging; modulates key signaling pathways | Y-27632 recommended at 10 μM when plating single cells to improve viability [46] |

| Characterization Tools | Cardiac Troponin T (cTNT) antibodies, OCT3/4, TRA-1-60 | Validates differentiation efficiency and pluripotency status | Assess pluripotency markers (>90% expression) before differentiation initiation [46] |

Advanced Techniques: Engineering More Reproducible Systems

Assembloid and Co-Culture Approaches

To overcome limitations of single-region organoids, researchers have developed "assembloid" techniques that combine organoids from different brain regions. This approach simulates more complex neurodevelopmental processes and reveals subtle pathological changes in neurological disorders. Examples include cortical-striatal assembloids to model circuit formation and systems that integrate brain organoids with intestinal organoids to study the brain-gut axis [47].

Microfluidic and Engineering Solutions

The integration of microfluidic technology ("organ-on-chip") brings significant advantages for controlling the cellular microenvironment, promoting vascular network formation, and enabling real-time dynamic monitoring of cells [47]. These systems allow for precise control of flow, gradient formation, and shear stress to better mimic in vivo conditions. When combined with biosensors and real-time readouts, these platforms enable continuous monitoring of differentiation progression and drug responses, improving both throughput and data quality [13].

Protocol Standardization Methods

Emerging methods focus on bypassing problematic intermediate stages to improve reproducibility. For example, the "Hi-Q brain organoid" culture method bypasses the traditional embryoid body stage, directly inducing iPSCs to differentiate into neurospheres with precisely controlled size using custom uncoated microplates. This approach eliminates size inconsistencies and differentiation abnormalities, enabling generation of hundreds of high-quality organoids per batch with minimal activation of cellular stress pathways [47].

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center addresses common challenges in bioreactor-based organoid culture, with a specific focus on strategies to minimize batch-to-batch variability for more reproducible research and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is controlling shear stress critical in organoid bioreactors? Shear stress, the frictional force exerted by fluid flow, is a major environmental determinant in bioreactors. While some shear stress is inevitable and can even promote differentiation, excessive stress causes cell damage and death, compromising organoid integrity and yield [23]. For sensitive cells like Caulobacter crescentus, shear stress exceeding 2 Pascal (Pa) can disrupt cellular attachment and shape, discouraging surface colonization [48]. Precise control is therefore essential to balance positive differentiation cues against destructive forces.

2. Our organoid batches show high variability. What are the primary sources? Batch-to-batch variation is a central challenge in organoid technology [49]. Key sources of this variation include:

- Genetic Heterogeneity: Patient-derived samples have inherent genetic diversity [8].

- Protocol Inconsistencies: Variations in cell culture protocols between labs and even between operators lead to differences in organoid structure and function [49].

- Starting Material Differences: The source of stem cells (iPSCs vs. adult stem cells) and their handling can significantly impact outcomes [23].

- Uncontrolled Microenvironment: Fluctuations in bioreactor parameters like shear stress, nutrient delivery, and dissolved gasses directly impact growth and differentiation [23].

3. What are the advantages of microbioreactor arrays? Microbioreactor arrays offer several key advantages for controlling the cellular microenvironment [50]:

- Enhanced Control: They enable precise regulation of mass transport and flow shear due to well-defined geometry and short transport distances.

- High-Throughput Screening: The miniaturized format allows for parallel experimentation, facilitating multi-parametric analysis.

- Fast Transients: Small volumes allow for rapid changes in medium composition, enabling the creation of precise spatial and temporal concentration gradients.

- Imaging Compatibility: Most systems are optically transparent, allowing for real-time, online monitoring of the culture.

4. How can I quickly detect contamination in my bioreactor? Early contamination detection is key to saving resources. Common indicators include [51]:

- Unexpected Growth Patterns: Growth occurring earlier than expected, with changes in culture density, color, or smell.

- Medium Color Change: For cell culture medium containing phenol red, a color change from pink to yellow indicates acid formation from microbial metabolism.

- Increased Turbidity: A visible increase in the cloudiness of the culture medium.

- Poor Cell Performance: For cell cultures, suboptimal growth may be the only clue for contaminants like mycoplasma or viruses.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Organoid Differentiation Across Batches

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|