Temporal Dynamics of HoxA and HoxD Gene Expression in Limb Development: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Clinical Implications

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the temporal dynamics of HoxA and HoxD gene expression during vertebrate limb development.

Temporal Dynamics of HoxA and HoxD Gene Expression in Limb Development: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the temporal dynamics of HoxA and HoxD gene expression during vertebrate limb development. We explore the foundational principles of Hox temporal collinearity and its critical role in proximal-distal patterning, examining how sequential gene activation dictates limb segment identity from stylopod to autopod. The review details methodological approaches for analyzing Hox expression patterns and chromatin architecture, addresses challenges in manipulating these complex regulatory networks, and presents comparative analyses across species that reveal both conserved mechanisms and evolutionary adaptations. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comprehensive analysis highlights how understanding Hox gene temporal regulation provides insights into congenital limb malformations and potential regenerative medicine strategies, bridging fundamental developmental biology with clinical applications.

Unraveling Hox Temporal Collinearity: The Clockwork of Limb Pattern Formation

Temporal collinearity, the sequential activation of Hox genes from the 3' to the 5' end of their clusters in the order of their chromosomal arrangement, represents a fundamental principle in developmental biology. This phenomenon establishes a crucial temporal framework that translates into spatial organization along the anterior-posterior axis during embryogenesis. Within the context of limb development, the precise implementation of this mechanism for Hoxa and Hoxd genes directs the formation of morphological distinctness and positional identity. This technical review examines the molecular underpinnings of temporal collinearity, synthesizing current evidence from genetic, epigenetic, and chromatin architectural studies. We provide detailed experimental protocols for investigating this phenomenon, summarize quantitative data in structured formats, and visualize key regulatory networks. Understanding these principles provides critical insights for developmental biology research and offers potential pathways for therapeutic intervention in congenital disorders and regenerative medicine applications.

The Hox gene family, comprising 39 genes in mammals organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD), encodes transcription factors that orchestrate anterior-posterior (A-P) patterning during embryonic development [1]. These genes exhibit two remarkable organizational principles: spatial collinearity, where their expression domains along the A-P axis correspond to their physical order within the clusters, and temporal collinearity, where their sequential activation in time follows their 3' to 5' genomic arrangement [2] [3]. This precise spatiotemporal regulation ensures that specific anatomical structures develop at correct positions along the body axes.

The concept of temporal collinearity was first established through observations that Hox genes located at the 3' end of clusters are activated earlier in development than those located more 5' [3]. While initially characterized during axial patterning, this principle extends to other developmental contexts, including limb development, where Hoxa and Hoxd genes are sequentially activated in distinct phases to pattern the proximal-distal axis [4]. The mechanistic basis of temporal collinearity involves complex interplay between transcription factors, chromatin modifications, non-coding RNAs, and higher-order chromatin architecture [5] [6].

Despite some debate regarding its universality, substantial evidence from multiple vertebrate models supports the existence and functional significance of temporal collinearity [2] [1]. In Xenopus, chicken, and mouse embryos, comprehensive studies using in situ hybridization have demonstrated nearly sequential temporally collinear expression patterns, generating nested "Russian Doll" expression patterns that expand from a common initiation point [1]. The conservation of this mechanism across vertebrates underscores its fundamental importance in embryonic patterning.

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Temporal Collinearity

Chromatin Architecture and Loop Extrusion

Recent research has elucidated how dynamic changes in chromatin structure facilitate the sequential activation of Hox genes. The process involves directional loop extrusion mediated by cohesin complexes moving along the chromatin fiber until encountering CTCF proteins bound at specific orientation-specific sites [6].

In mouse embryonic stem cell-derived stembryos, the Hox timer initiates with Wnt-dependent transcription of the CTCF-free anterior part of the cluster, triggering asymmetric loading of cohesin complexes over this domain [6]. This is followed by stepwise transcriptional activation of genes in the CTCF-rich region after a 3'-to-5' progression in loop extrusion. The HoxD cluster contains nine conserved CTCF-binding sites (CBSs), with anterior CBSs (CBS1, CBS2, CBS4, CBS5) oriented opposite to posterior CBSs (CBS6, CBS7, CBS8, CBS9) [6]. This organization creates checkpoints that control the pace of temporal activation.

The sequential insulation by conserved CTCF sites underlies the Hox timer, with successively more posterior CTCF sites acting as transient insulators [6]. This generates progressive time delays in the activation of more posterior-located genes due to long-range contacts with flanking topological associating domains (TADs). Mutant studies confirm that evolutionarily conserved, regularly spaced intergenic CTCF sites control both the precision and pace of this temporal mechanism [6].

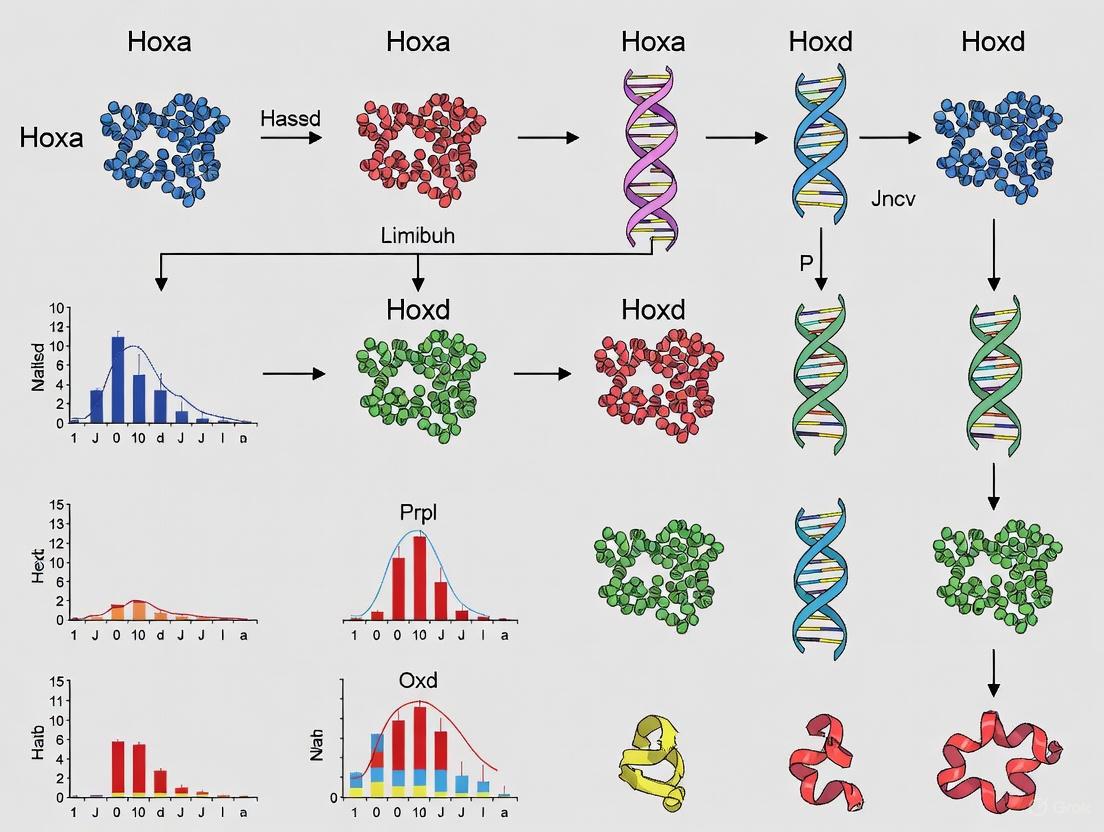

Figure 1: CTCF-Guided Loop Extrusion Mechanism. The cohesin complex (red) loads at the 3' end of the Hox cluster and extrudes chromatin until encountering directionally-oriented CTCF binding sites (blue). This creates sequential time delays in gene activation, with 3' genes activated early and 5' genes activated later through long-range contacts with flanking topological associating domains (green).

Epigenetic Regulation and Non-Coding RNAs

Epigenetic mechanisms play a crucial role in establishing and maintaining the sequential activation pattern of Hox genes. The short isoform (p52) of the transcriptional co-activator Psip1 (PC4 and SF2 interacting protein) specifically regulates expression of the lncRNA Hottip, located at the 5' end of the Hoxa locus [5]. Hottip expression is required for activation of the 5' Hoxa genes (Hoxa13 and Hoxa10/11) and for retaining the Mll1 histone methyltransferase complex at the 5' end of Hoxa [5].

Artificially inducing Hottip expression is sufficient to activate 5' Hoxa genes, and Hottip RNA itself binds to the 5' end of Hoxa, demonstrating a direct role for this lncRNA molecule in maintaining active expression of posterior Hox genes in cis [5]. Engineering premature transcription termination of Hottip confirms that the RNA molecule itself, not just its transcription, is required for this regulatory function [5].

Histone modification patterns also correlate with sequential gene activation. Sequential posttranslational modifications of histones—from transcriptionally silent-specific to active-specific forms—accompany the sequential gene activation [4]. Changes in higher-order chromatin organization, including chromatin de-condensation and looping out of chromosome territories, further contribute to the sequential activation process [4].

Signaling Pathways and Transcriptional Regulation

The initial activation of the temporal sequence depends on external signaling cues, particularly Wnt signaling, which triggers the onset of collinear expression [6]. Following Wnt activation, the process involves transcriptional initiation at the anterior part of the cluster with concomitant loading of cohesin complexes enriched on transcribed DNA segments [6].

BMP/anti-BMP signaling interactions play a crucial role in translating temporal collinearity into spatial patterns. In Xenopus, temporally collinear Hox sequences start in ventrolateral, BMP-rich non-organizer mesoderm (NOM) and are converted to dorsal spatial patterns after mesodermal convergence-extension movements by anti-BMP signals from the Speman organizer [2]. This mechanism is conserved across vertebrate species, with similar observations in chicken and zebrafish [2].

Hox proteins themselves participate in regulatory circuits that maintain expression patterns. Studies in limb development reveal that HOX proteins establish and/or maintain the spatial domains of Hox gene family expression through self-regulatory mechanisms [4]. The functionally dominant HOX proteins contribute to generating the spatial parameters of Hox expression in a given tissue, establishing the ultimate HOX code that determines morphological outcomes [4].

Temporal Collinearity in Limb Development

Limb development represents a particularly insightful model for understanding the implementation of temporal collinearity in patterning specific structures. During limb development, genes from HoxA and HoxD clusters are activated in a sequential manner following their order within the cluster, leading to expression domains that are colinear both in space and time [4].

Hoxd gene expression occurs in two independent phases controlled by distinct cis-regulatory elements [4]. The initial phase (phase one) is controlled by the 3' early limb control region (ELCR), which regulates the sequential timing of gene activation following temporal collinearity principles [4]. During this phase, a 5' regulatory region (POST) exerts a repressive effect to spatially restrict 5'Hoxd expression to the posterior mesenchyme of early limb buds [4].

The second phase (phase two) occurs exclusively in the presumptive digit-forming region and is mechanistically unlinked to the first expression phase [4]. This phase occurs in a reverse colinear manner, with the most 5' transcription unit (Hoxd13) expressed most strongly throughout the entire presumptive digit territory, while Hoxd12 to Hoxd9 are transcribed with progressively lower efficiency [4]. This bimodal regulatory implementation demonstrates how temporal collinearity principles can be adapted to create complex morphological structures.

Figure 2: Biphasic Hox Regulation in Limb Development. During limb development, Hox genes are regulated in two distinct phases. Phase 1 follows classical temporal collinearity with 3' to 5' activation for proximal-distal patterning. Phase 2 exhibits reverse collinearity for digit patterning, with strongest expression of 5' genes.

Experimental Analysis of Temporal Collinearity

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Investigating temporal collinearity requires sophisticated approaches that capture both the dynamic nature of gene expression and the spatial context of developing tissues. The following experimental protocols represent state-of-the-art methodologies in the field.

Spatiotemporal Transcriptomic Profiling in Stembryos:

- Culture Conditions: Generate gastruloids from aggregated mouse embryonic stem (mES) cells cultivated in vitro for several days [6].

- Wnt Activation: Apply a pulse of the Wnt agonist Chiron 48 hours after aggregation (between 48h-72h) to trigger differentiation into posterior elongating body axis structures [6].

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect samples at precise intervals (e.g., 12-hour increments from 72h to 168h) for parallel analysis of chromatin states and transcriptomes [6].

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation: Perform ChIP-seq for H3K27ac to track active enhancer dynamics and RNA Pol II binding to monitor transcriptional activity across the Hox clusters [6].

- Cohesin Complex Mapping: Conduct RAD21 and NIPBL ChIP-seq to profile cohesin loading and distribution across the locus during activation [6].

Functional Validation of lncRNA Mechanisms:

- Genetic Manipulation: Employ both knockout and knockdown approaches to perturb lncRNA Hottip expression [5].

- Premature Transcription Termination: Engineer premature termination of Hottip transcription to distinguish between the function of the transcription process versus the RNA molecule itself [5].

- Artificial Induction:

- RNA Localization: Perform RNA immunoprecipitation to confirm direct binding of Hottip RNA to the 5' end of the Hoxa cluster [5].

Spatial Transcriptomics in Developing Tissues:

- Tissue Preparation: Collect and embed developing tissues (e.g., limb buds) in optimal cutting temperature compound and cryosection at appropriate thickness [8].

- Spatial Barcoding: Process sections using 10× Genomics Visium spatial transcriptomics platform to capture location-specific transcriptomes [8].

- In Situ Sequencing: Perform targeted in situ sequencing (ISS) for 150 selected transcripts to validate spatial expression patterns with cellular resolution [8].

- Data Integration: Deconvolve spatial transcriptomics data with single-cell RNA sequencing datasets to map cell states to specific tissue locations [8].

Quantitative Data Analysis

Table 1: Temporal Sequence of Hox Gene Activation in Stembryos

| Time Point (hours) | Activated Hox Genes | Associated Chromatin Events | Regulatory Domain Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 72h | Hoxd1, Hoxd3, Hoxd4 | Initial H3K27ac peaks in anterior cluster | No T-DOM activity detected |

| 84h | Hoxd1-Hoxd4 expansion | Acetylation spreads to Hoxd4-Hoxd8 segment | Early T-DOM activation begins |

| 96h | Hoxd8, Hoxd9 (low) | Progressive acetylation throughout central cluster | Strong sub-TAD1 acetylation |

| 108h | Hoxd8, Hoxd9 (increased) | Continued 3'-5' spreading | T-DOM enhancers fully active |

| 132h | Hoxd10, Hoxd11 | Acetylation reaches posterior genes | Sustained T-DOM activity |

| 144h | Hoxd13 | Full cluster acetylation | Maintenance of long-range contacts |

Data derived from timecourse analysis of H3K27ac ChIP-seq and transcriptome profiling in mouse stembryos [6].

Table 2: Hox Gene Expression Response to Ectopic Hoxa-5 Activation

| Time Post-Induction | Endogenous Hox Response | Affected Genomic Regions | Magnitude of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 hours | No significant change | N/A | Baseline |

| 4-8 hours | Initial upregulation | Upstream and downstream genes in same cluster | 2-3 fold increase |

| 8-12 hours | Peak response | Genes from other Hox clusters | 4-8 fold increase |

| 12-24 hours | Transient decline | All affected genes | Return toward baseline |

| >24 hours | Stabilization | Established new expression domains | Sustained 1.5-2 fold change |

Data from inducible Hoxa-5 expression in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells showing coordinated trans-activation of other Hox genes with an 8-hour delay between peak transgene expression and endogenous response [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Temporal Collinearity

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) | Stembryo formation for in vitro Hox timer studies [6] | Maintain pluripotency; optimize differentiation protocols |

| F9 embryonal carcinoma cells | Hox gene induction studies [7] | Responsive to retinoid signaling; express endogenous Hox genes | |

| Genetic Tools | Inducible promoter systems (Tet-On) | Controlled Hox gene expression [7] | Optimize induction timing and concentration to mimic endogenous expression |

| CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Targeted deletion of CTCF sites or lncRNA genes [5] [6] | Verify complete knockout and assess off-target effects | |

| Antibodies | Anti-H3K27ac | Chromatin state analysis during Hox activation [6] | Validate specificity for active enhancers and promoters |

| Anti-RAD21/NIPBL | Cohesin complex mapping [6] | Optimize for ChIP-seq applications | |

| Anti-RNA Pol II | Transcription activation monitoring [6] | Distinguish between initiating and elongating forms | |

| Detection Reagents | In situ hybridization probes | Spatiotemporal expression patterning [1] [3] | Design against specific Hox genes; optimize for tissue penetration |

| Spatial barcoding oligonucleotides | Visium spatial transcriptomics [8] | Maintain RNA quality during tissue processing | |

| Signaling Modulators | Wnt agonists (Chiron) | Initiate Hox timer in stembryos [6] | Optimize concentration and pulse duration |

| BMP/Noggin reagents | Manipulate BMP/anti-BMP signaling [2] [1] | Determine stage-specific effects on Hox patterning |

Discussion and Research Implications

The principle of temporal collinearity represents a remarkable example of how genomic organization is leveraged to create developmental timing mechanisms. The sequential activation of Hox genes from 3' to 5' provides a temporal framework that is translated into spatial patterning through the action of signaling gradients and chromatin architecture [2] [6] [1]. The conservation of this mechanism across vertebrate species underscores its fundamental importance in embryonic development.

In the context of limb development research, understanding temporal collinearity provides crucial insights into how proximal-distal patterning is established. The biphasic regulation of Hoxd genes—with an initial temporally collinear phase for proximal-distal patterning followed by a reverse collinear phase for digit specification—demonstrates the versatility of this regulatory logic [4]. The perturbation of these patterns leads to dramatic homeotic transformations, illustrating their functional significance [4].

Recent advances in chromatin conformation capture technologies and single-cell spatial transcriptomics have revolutionized our ability to study these processes with unprecedented resolution [6] [8]. The integration of these multi-modal datasets will continue to reveal new layers of regulation and provide deeper insights into how temporal sequences of gene activation are established and maintained.

From a translational perspective, understanding Hox temporal collinearity has important implications for regenerative medicine and stem cell engineering [9]. Recapitulating proper Hox activation sequences may be essential for generating properly patterned tissues from stem cells. Furthermore, given the importance of Hox genes in certain cancers, manipulating these regulatory networks may offer novel therapeutic approaches [9]. The continued investigation of temporal collinearity will undoubtedly yield both fundamental insights and practical applications across developmental biology and regenerative medicine.

The development of the tetrapod limb is a fundamental process in evolutionary and developmental biology, orchestrated by precise spatiotemporal gene expression patterns. Central to this process is the HoxD gene cluster, which is regulated via a distinctive bimodal mechanism comprising early and late transcriptional waves. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes current research to elucidate the core principles of this two-phase model, its underlying regulatory architectures—including the critical roles of topologically associating domains (TADs) and enhancer-gene looping—and the experimental methodologies used for its investigation. Framed within the broader context of temporal dynamics in Hoxa and Hoxd gene expression during limb morphogenesis, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a structured overview of quantitative data, key reagents, and visualized regulatory circuits essential for understanding this complex genetic system.

The HoxD cluster is paramount for the proper growth and patterning of tetrapod limbs. Its transcriptional regulation during limb development is characterized by two successive waves, each controlling the formation of distinct limb segments [10] [11]. This bimodal regulatory strategy is not an isolated phenomenon; it is observed in parallel at the HoxA cluster, revealing a shared evolutionary and developmental logic for patterning the appendicular skeleton [12].

- Early Phase: This initial wave of

Hoxdgene expression is activated in a collinear fashion, starting withHoxd1and progressing toward the 5' end of the cluster (e.g.,Hoxd13). It is essential for the patterning and outgrowth of the proximal limb structures, namely the stylopodium (e.g., humerus) and zeugopodium (e.g., radius and ulna) [13] [14]. This phase also establishes the limb's anterior-posterior polarity by inducing the expression ofsonic hedgehog(Shh) in the posterior-distal cells [13]. - Late Phase: A subsequent wave of activation specifically involves the 5'

Hoxdgenes (fromHoxd10toHoxd13) alongsideHoxa13. This phase is crucial for the morphogenesis of the most distal limb structures, the autopodium, which includes the wrist/ankle and digits [11] [14]. The expression in digits follows a "quantitative collinearity" or "reverse collinearity," where the most 5' gene,Hoxd13, is expressed at the highest level and in the most anterior digit (e.g., the thumb) [13].

The transition between these two phases, and the resulting domain of low Hoxd expression between them, is genetically delineated by a shift in the engagement of the cluster with two opposing regulatory landscapes, and it gives rise to the future wrist and ankle articulations [15].

Core Regulatory Architecture and Signaling Pathways

Distinct Regulatory Landscapes and Chromatin Topology

The two transcriptional waves are governed by separate sets of enhancers located within two large, flanking regulatory landscapes that correspond to distinct Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) [15] [12].

Table 1: Core Regulatory Landscapes Controlling HoxD Bimodal Expression

| Regulatory Domain | Genomic Position | Phase Controlled | Key Enhancer Elements | Key Target Genes | Primary Limb Structures Formed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telomeric Domain (T-DOM) | 3' of the HoxD cluster | Early | Multiple enhancers within the T-DOM [15] | Hoxd1 to Hoxd11 [15] |

Stylopodium, Zeugopodium [13] |

| Centromeric Domain (C-DOM) | 5' of the HoxD cluster | Late | Global Control Region (GCR), Prox [16] [13] | Hoxd10 to Hoxd13 [15] |

Autopodium (Digits) [13] |

The gene Hoxd9 to Hoxd11, located in the central part of the cluster, are particularly remarkable as they can switch their interactions. They initially engage with the T-DOM during the early phase and later with the C-DOM during the late phase [15]. This switch is partly facilitated by HOX13 proteins themselves, which can inhibit T-DOM activity while reinforcing the function of enhancers within the C-DOM [15].

A key feature of the late phase regulation is the formation of a chromatin loop that brings the distant enhancers, particularly the GCR, into physical proximity with the 5' Hoxd gene promoters. This looping event, detected via chromosome conformation capture techniques, is specifically observed in the posterior distal limb mesenchyme where the late phase expression is strongest [16]. Furthermore, this region exhibits a more "open" chromatin state compared to the anterior limb, characterized by a loss of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 (catalyzed by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2) and a general decompaction of chromatin structure [16].

Figure 1: Regulatory Architecture of the Two-Phase HoxD Model. The early phase is driven by the telomeric domain (T-DOM), while the late phase is controlled by the centromeric domain (C-DOM) via chromatin looping. Key features include a switch in central Hoxd gene allegiance and positive feedback from HOX13 proteins.

Quantitative Collinearity and Digit Patterning

During the late phase in the autopod, the genes Hoxd10 to Hoxd13 are expressed with overlapping profiles but at quantitatively different levels, a phenomenon termed "quantitative collinearity" [13]. The expression level is inversely correlated with the gene's distance from the 5' end of the cluster: Hoxd13 is the most highly expressed, followed by progressively lower levels of Hoxd12, Hoxd11, and Hoxd10 [13].

This dosage gradient has profound morphological consequences. The most anterior digit (e.g., the thumb) forms from a region where the concentration of the SHH morphogen is lowest. In this region, only Hoxd13 is expressed at a detectable level, while the other posterior Hoxd genes are silenced. This unique, low-dose Hox environment is essential for giving the thumb its distinct morphology ("thumbness"). Ectopic expression of other posterior Hoxd genes in this anterior domain leads to a transformation of the thumb into a more posterior-like digit [13].

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

The two-phase model is supported by extensive genetic and molecular evidence, primarily from engineered mouse models and comparative studies in other vertebrates.

Key Genetic Manipulations and Phenotypes

Systematic chromosomal rearrangements, such as deletions, duplications, and inversions, have been instrumental in mapping the regulatory landscapes.

Table 2: Quantitative Hoxd Gene Expression in E12.5 Mouse Digit Cells (Wild-Type)

| Hoxd Gene | Relative Position in Cluster | Relative mRNA Steady-State Level | Expression in Presumptive Digit I (Thumb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxd13 | Most 5' | High | Yes |

| Hoxd12 | ↑ | Intermediate | No |

| Hoxd11 | ↑ | Intermediate | No |

| Hoxd10 | Most 3' of the late-phase genes | Low | No |

For instance, when Hoxd12 was experimentally repositioned to the location normally occupied by Hoxd13, it was expressed at a similarly high level and its transcript domain expanded into the presumptive thumb territory, where it is normally silent [13]. This demonstrates that a gene's expression level and spatial domain during the late phase are determined more by its relative position within the cluster than by the specific identity of its promoter.

Large inversions that relocate the digit-specific enhancers (GCR and Prox) away from the HoxD cluster result in a severe loss of Hoxd gene expression in the autopod and consequent digit agenesis [13]. Conversely, a mutant mouse strain lacking a large part of the T-DOM showed that the early phase regulation is essential for proximal limb development, and its absence can lead to morphological differences between fore- and hindlimbs [15].

Cross-Species Conservation and Divergence

The bimodal regulatory strategy is highly conserved among tetrapods. However, important modifications in its implementation contribute to morphological diversity [15]. A comparison between mouse and chicken limbs revealed that although the global mechanism is conserved, the duration of T-DOM regulation is significantly shortened in chicken hindlimb buds, correlating with a reduction in Hoxd gene expression and distinct zeugopod morphology [15].

Notably, the regulatory potential for the late phase appears to be an ancient feature. The bimodal chromatin architecture is also present in fish embryos such as zebrafish [12]. However, when the orthologous fish DNA sequences of the digit enhancer (GCR) were introduced into transgenic mice, they drove reporter gene expression in the proximal limb but failed to robustly activate transcription in the distal digit-forming region [12]. This supports an evolutionary scenario wherein the autopod (digits) arose as a tetrapod novelty through the genetic retrofitting of pre-existing regulatory landscapes, co-opting them for a new function in distal limb development [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Studying HoxD Regulation

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Engineered Mouse Strains | To study gene function and regulation in vivo via loss-of-function, deletion, duplication, or inversion alleles. | TAMERE (Targeted Meiotic Recombination) for creating custom deletions/duplications [13]; Hoxd cluster mutant alleles [15]. |

| Immortalized Cell Lines | Provide a scalable in vitro system for biochemical and molecular analyses from specific limb regions. | Mesenchymal cells derived from anterior vs. posterior distal E10.5 mouse limb buds [16]. |

| Antibodies for Chromatin Analysis | Used in Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to map histone modifications and protein binding. | H3K27me3 (for PRC2-repressed chromatin) [16]; Ring1B (for PRC1-repressed chromatin) [16]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | To map gene expression profiles within the anatomical context of intact tissue sections. | 10x Visium assay on embryonic limb sections [17]. |

| Chromatin Conformation Capture | To identify physical, long-range interactions between enhancers and promoters. | 4C (Circular Chromosome Conformation Capture) and Hi-C [12]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Chromatin Analysis from Limb Tissue

The following protocol, adapted from methods used to establish anterior-posterior differences in chromatin topology [16], provides a robust workflow for analyzing histone modifications in specific limb regions.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation from Embryonic Limb Tissue. The protocol outlines key steps from tissue collection through chromatin analysis, highlighting adaptations for low cell numbers from micro-dissected limb regions.

Procedure:

- Tissue Dissection: Collect limb buds from mouse embryos at the desired stage (e.g., E10.5 for late phase analysis). For anterior-posterior comparisons, carefully dissect the distal anterior third and distal posterior third of the limb buds separately. A large number of embryos (e.g., 50-70) may be required to obtain sufficient cell numbers for ChIP [16].

- Cell Dissociation and Cross-linking: Dissociate the pooled tissue into single cells using enzymatic treatment (e.g., trypsin). For crosslinked ChIP (xChIP), fix cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to crosslink proteins to DNA. Quench the crosslinking reaction with glycine. For native ChIP (nChIP), which is suitable for many histone modifications, this step can be omitted [16].

- Chromatin Fragmentation:

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear the fragmented chromatin. Incubate an aliquot of chromatin (10-50 μg) with a target-specific antibody (e.g., 3-5 μg of H3K27me3 antibody) that has been pre-bound to Protein A or G magnetic beads. Incubate for several hours at 4°C. Include a control with a non-specific IgG [16].

- DNA Purification and Analysis: After extensive washing to remove non-specifically bound chromatin, reverse the crosslinks (for xChIP) and purify the immunoprecipitated DNA. Analyze the enriched DNA by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers designed for regions of interest (e.g., within the

HoxDcluster, control regions). For unbiased genome-wide analysis, the purified DNA can be amplified and used for high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) [16].

The two-phase model of HoxD expression provides a powerful paradigm for understanding how complex transcriptional regulation of a gene cluster can orchestrate the development of a intricate organ system. The mechanistic shift from a T-DOM-driven to a C-DOM-driven regulation, mediated by a change in chromatin topology and looping, elegantly explains the patterning of evolutionarily distinct limb segments.

Future research in this field will likely focus on further elucidating the dynamics of the regulatory switch at the single-cell level, leveraging cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics and live-imaging techniques [17]. Furthermore, integrating the Hox-driven patterning with the Turing-type reaction-diffusion systems that specify the final digit cartilage condensations represents a key frontier [14]. Finally, a deeper comparative analysis across a wider range of vertebrate species, enabled by emerging model organisms and genomes, will continue to reveal how variations in this conserved bimodal toolkit have generated the breathtaking diversity of tetrapod limbs adapted for running, flying, swimming, and grasping [15] [18].

The precise spatiotemporal expression of Hox genes is fundamental for embryonic development, particularly in limb formation. This in-depth technical guide explores the dynamic reorganization of chromatin architecture underlying the regulation of Hoxa and Hoxd genes. We examine the transition from an initial single chromatin compartment in pluripotent cells to a bimodal organizational structure during differentiation, a process critical for implementing temporal collinearity in developing limbs. This review synthesizes current molecular understanding with detailed experimental methodologies, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols and analytical frameworks for investigating chromatin dynamics in developmental contexts and therapeutic applications.

Hox genes, encoding evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, are paramount for anterior-posterior (A-P) patterning in bilaterian animals. In vertebrates, the Hox gene family is organized into four clusters (HoxA-D), with the precise temporal and spatial expression of genes within these clusters governed by the principle of collinearity—where gene order within the cluster corresponds to their sequence of activation along the A-P axis [19] [20]. This review focuses on the chromatin architecture dynamics of Hoxa and Hoxd clusters during limb development, where their regulation exhibits unique features, including quantitative collinearity [16].

A profound structural transition in the 3D organization of Hox clusters accompanies their sequential activation. Initially, in embryonic stem (ES) cells or early embryonic cells, Hox clusters reside in a single chromatin compartment characterized by bivalent chromatin marks (both repressive H3K27me3 and activating H3K4me3 histone modifications) [21] [19]. Upon differentiation and transcriptional activation, this uniform structure resolves into a bimodal architecture with two spatially distinct compartments: one containing active genes marked by H3K4me3 and another harboring inactive genes decorated with H3K27me3 [21] [22]. This compartmentalization is thought to reinforce transcriptional states by preventing interference between active and inactive regulatory domains [21].

The Transition from Single Compartment to Bimodal Organization

Initial State: The Single Compartment in Pluripotent Cells

In the pre-activation state, such as in ES cells or early embryonic cells, Hox clusters exhibit a uniform 3D organization. The entire cluster, encompassing all genes, is configured as a single chromatin compartment [21]. This state is defined by a bivalent chromatin signature, where histone marks associated with both repression (H3K27me3, catalyzed by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 - PRC2) and activation (H3K4me3, catalyzed by Trithorax group proteins) co-exist [19]. This bivalency is thought to maintain genes in a "poised" state, ready for rapid activation or stable repression upon lineage commitment [19].

Dynamic Shift: Bimodal Compartmentalization upon Activation

Transcriptional activation triggers a fundamental restructuring of the Hox cluster. The single compartment splits into two distinct, spatially segregated compartments in a process termed bi-modal 3D organization [21] [22].

- Active Compartment: This domain contains transcriptionally active Hox genes, marked by high levels of H3K4me3 and associated with an open, accessible chromatin state.

- Inactive Compartment: This domain contains silent Hox genes, marked by repressive H3K27me3 and characterized by a more compacted chromatin structure.

This transition occurs gene by gene, with individual Hox genes autonomously switching from the inactive to the active compartment as they are transcriptionally activated, in a sequence that follows their genomic order (temporal collinearity) [21]. Importantly, these local 3D dynamics occur within a stable framework of constitutive interactions defined by the surrounding Topologically Associating Domains (TADs), indicating that the regulatory process is largely intrinsic to the cluster [21] [23].

Table 1: Key Features of Chromatin Compartments During Hox Cluster Activation

| Feature | Single Compartment (Initial State) | Bimodal Organization (Activated State) |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Stage | Pluripotent cells (ES cells, early embryo) | Differentiating cells (e.g., in developing limbs) |

| 3D Structure | Single, unified chromatin compartment | Two spatially segregated compartments |

| Histone Modifications | Bivalent domains (H3K27me3 + H3K4me3) | Resolved: Active comp. (H3K4me3), Inactive comp. (H3K27me3) |

| Gene Activity | All genes silent but "poised" | Sequential gene activation following genomic order |

| Regulatory Stability | Plastic state, primed for differentiation | Memory of transcriptional state, reduced interference |

Limb Development: A Paradigm for Bimodal Regulation

In the developing limb bud, the Hoxd cluster undergoes a specialized form of bimodal regulation driven by long-range enhancers. A "regulatory landscape" switch occurs, where the cluster alternates its interactions between two flanking TADs [20] [23]. The early phase of Hoxd expression is controlled by enhancers located in a telomeric gene desert (posterior TAD), while the later, distal limb phase (including digit development) is governed by enhancers in a centromeric gene desert (anterior TAD), such as the Global Control Region (GCR) [16] [20].

This switch is physically manifested as a change in chromatin looping. Specifically in the distal posterior limb, the GCR enhancer spatially colocalizes with the 5' end of the HoxD cluster, forming a chromatin loop that brings the enhancer into contact with its target genes like Hoxd13 [16]. This looping event is associated with a loss of PRC2-catalyzed H3K27me3 and a decompaction of chromatin over the HoxD locus in the posterior limb compared to the anterior, facilitating high-level, posterior-restricted gene expression essential for digit patterning [16].

Figure 1: Developmental Transition from Single Compartment to Bimodal Chromatin Architecture. The diagram illustrates the progression from a unified, bivalent chromatin state to a spatially segregated structure with active and inactive compartments during Hox gene activation.

Quantitative Data and Chromatin States

The dynamic changes in chromatin architecture are quantifiable through various genomic and epigenomic approaches. The following tables consolidate key quantitative data relevant to studying Hox chromatin dynamics in limb development.

Table 2: Quantitative Changes in Histone Modifications at Hox Loci During Activation

| Genomic Region | Assay | Change During Activation | Biological Significance | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5' Hoxd genes (e.g., Hoxd13) | ChIP-qPCR / ChIP-chip | Loss of H3K27me3, Gain of H3K4me3 | Chromatin opening for transcription; Posterior-specific expression in limb | E10.5 mouse distal limb [16] |

| Active Hox genes | ChIP-seq | High H3K4me3 to H3K27me3 ratio | Definitive transcriptional activation | Differentiating ES cells, Embryonic tissues [19] |

| Inactive Hox genes | ChIP-seq | High H3K27me3 to H3K4me3 ratio | Stable maintenance of silencing | Differentiating ES cells, Embryonic tissues [19] |

| Entire Hox cluster (initial state) | ChIP-seq | Bivalent domains (both marks) | Poised state for lineage commitment | Embryonic Stem (ES) Cells [19] |

Table 3: Key Structural and Temporal Parameters in Hox Cluster Reorganization

| Parameter | Description | Approximate Value / Timing | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Hox Transcription | Start of sequential activation in mouse embryo | ~Embryonic day 7 (E7.0) | Main body axis [21] |

| Activation of Last Hox Genes | Hox group 13 genes transcription detected | ~E9.0 (2 days after onset) | Main body axis [21] |

| Late Phase Hoxd Activation | Onset in distal limb bud for digit morphogenesis | E10.5 | Limb development [16] |

| GCR - HoxD Distance | Genomic distance between enhancer and target | ~180 kb | Mouse HoxD locus [16] |

| TAD Size | Size of topological domains flanking Hox clusters | ~100s of kilobases | Mouse limb buds [20] [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Chromatin Dynamics

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments used to characterize the 3D architecture and epigenetic state of Hox gene loci.

Circular Chromosome Conformation Capture (4C-seq)

4C-seq is a powerful technique to identify all genomic regions that physically interact with a specific "viewpoint" fragment of interest, making it ideal for studying enhancer-promoter contacts and compartmentalization.

Detailed Workflow:

- Cross-linking: Treat cells or fresh-frozen tissue (e.g., dissected mouse limb buds) with 2% formaldehyde to covalently crosslink DNA and associated proteins, preserving spatial chromatin interactions. Quench with glycine.

- Lysis and Digestion: Lyse cells and digest the crosslinked chromatin with a primary restriction enzyme (e.g., DpnII, a frequent cutter with 4-bp recognition site). This fragments the genome while maintaining crosslinked complexes.

- Proximity Ligation: Dilute the digested chromatin and perform intra-molecular ligation under conditions that favor ligation between crosslinked fragments. This creates chimeric DNA molecules from genomically distant but spatially proximal loci.

- Reverse Cross-linking: Purify the DNA and reverse the crosslinks by proteinase K treatment and heating.

- Secondary Digestion: Digest the ligated DNA with a second restriction enzyme (e.g., Csp6I, a 4-bp cutter) to reduce the complexity of the 4C template.

- Second Ligation: Perform a second round of intra-molecular ligation to create small, circular DNA molecules suitable for PCR amplification.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the 4C template using inverse PCR primers designed against the specific "viewpoint" of interest (e.g., within the Hoxd13 promoter or the GCR enhancer).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the PCR products and sequence using high-throughput platforms (e.g., Illumina).

- Data Analysis: Map sequencing reads back to the reference genome. Interaction frequency is quantified as the number of reads originating from each genomic region interacting with the viewpoint. Data is typically visualized as interaction profiles across chromosomes.

Key Applications:

- Identifying long-range contacts between Hox genes and regulatory elements like the GCR [16].

- Defining the boundaries of active and inactive chromatin compartments at Hox clusters [21] [22].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for Histone Modifications

ChIP allows for the mapping of specific histone modifications and associated proteins to genomic regions.

Detailed Workflow (Native ChIP for H3K27me3):

- Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) Digestion: Isolate nuclei from cells or tissue. Digest chromatin with MNase to yield primarily mononucleosomes, preserving histone-DNA interactions natively.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the solubilized nucleosomes with an antibody specific to the histone mark of interest (e.g., anti-H3K27me3). Use Protein A/G magnetic beads to capture the antibody-nucleosome complexes.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound material. Elute the immunoprecipitated chromatin complexes.

- DNA Purification: Reverse cross-links (if formaldehyde was used post-MNase) and purify the associated DNA.

- Analysis:

- ChIP-qPCR: Quantify the enrichment of specific genomic regions (e.g., Hox gene promoters) relative to a control (input DNA) using quantitative PCR with specific primers.

- ChIP-seq: Prepare a sequencing library from the purified DNA. After high-throughput sequencing, map reads to the genome to generate genome-wide maps of histone modification enrichment.

Key Applications:

- Demonstrating the loss of H3K27me3 over the 5' HoxD region in the distal posterior limb versus anterior limb [16].

- Tracking the resolution of bivalent chromatin and the progressive transition from H3K27me3 to H3K4me3 during Hox gene activation [21] [19].

Figure 2: 4C-Seq Experimental Workflow. Key steps for identifying chromatin interactions from a specific viewpoint, crucial for mapping enhancer-promoter contacts in Hox regulation.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Architecture Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function/Description | Example Application in Hox Research |

|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3-specific Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of nucleosomes containing repressive histone mark. | Mapping Polycomb-mediated silencing over Hox clusters via ChIP [16] [19]. |

| H3K4me3-specific Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of nucleosomes containing active histone mark. | Identifying actively transcribed regions of Hox clusters via ChIP [19]. |

| DpnII Restriction Enzyme | Frequent cutter (GATC) for initial digestion in 3C/4C protocols. | Fragmenting crosslinked chromatin for proximity ligation in 4C-seq [21]. |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Efficient capture of antibody-bound complexes. | Immunoprecipitation step in ChIP and RNA-DNA pull-down assays [16]. |

| Viewpoint-specific PCR Primers | Amplification of ligation products from a specific genomic locus in 4C. | Probing interactions from Hoxd13 promoter or GCR enhancer [16] [22]. |

| Immortomouse-derived Cell Lines | Conditionally immortalized cells (e.g., expressing tsA58 T-antigen). | Generating proliferative mesenchymal cells from anterior/posterior limb buds [16]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics (10x Visium) | Genome-wide RNA sequencing with spatial context in tissue sections. | Mapping Hox expression patterns and cellular heterogeneity in human embryonic limbs [17]. |

| Custom Tiling Microarray / Sequencing | High-resolution platform for hybridizing ChIP or 4C products. | Genome-wide mapping of histone modifications or chromatin interactions [16]. |

The transition from a single chromatin compartment to a bimodal organization represents a fundamental principle in the regulation of Hoxa and Hoxd genes during limb development. This dynamic architectural reprogramming, governed by epigenetic mechanisms and long-range enhancer contacts, provides a robust structural framework for implementing the precise spatiotemporal gene expression patterns required for morphogenesis. The experimental frameworks and technical resources detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers to further dissect these mechanisms.

Future challenges in the field include uncovering the precise "timer" that controls the sequential gene switching within the cluster and elucidating how the chromatin state is faithfully memorized and maintained through cell divisions. Furthermore, integrating single-cell resolution analyses of chromatin architecture with spatial transcriptomic data, as exemplified by recent human embryonic limb atlases [17], will be crucial for understanding cell fate decisions in complex tissues. A deeper mechanistic understanding of these processes will not only illuminate basic principles of developmental biology but also inform therapeutic strategies for congenital limb malformations and other diseases rooted in errors of genomic regulation.

Hox Gene Positioning and Its Impact on Activation Timing

Hox genes, which encode a family of critical transcription factors, are master regulators of embryonic development in bilaterian animals. Their unique mode of collinear regulation—whereby the order of genes along the chromosome corresponds to their temporal and spatial expression during development—represents a fundamental paradigm in developmental biology [24] [25]. In the context of limb development, this relationship is paramount for translating genomic organization into precise morphological structures. The temporal dynamics of Hoxa and Hoxd gene expression are not merely correlated with their genomic positioning; emerging evidence suggests this relationship is causal, governed by sophisticated chromatin architecture and long-range regulatory interactions [15] [21] [25]. This whitepaper synthesizes current mechanistic understanding of how Hox gene positioning dictates activation timing, with specific focus on implications for patterning the vertebrate limb.

Table: Core Concepts in Hox Gene Temporal Regulation

| Concept | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Collinearity | The correspondence between gene order on the chromosome and expression patterns [25]. | Ensures coordinated patterning of the anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes. |

| Temporal Collinearity | Sequential activation of Hox genes in time, following their genomic order (3' before 5') [21]. | Couples axial elongation with patterning; the "Hox clock." |

| Spatial Collinearity | Sequential domains of Hox gene expression in space along the body axis [21]. | Provides a combinatorial code for regional identity. |

| Bimodal Regulation | Control of a gene cluster by two separate regulatory landscapes [15]. | Enables distinct transcriptional programs in different contexts (e.g., limb segments). |

Genomic Organization and the Principle of Collinearity

The Hox Gene Clusters

In vertebrates, Hox genes are organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) located on different chromosomes, a result of two rounds of whole-genome duplication from a single ancestral cluster [26] [25]. Each cluster contains up to 13 paralogous groups, and members of the same group share sequence similarity and often overlapping functions [26]. The genes within each cluster are all transcribed in the same 5' to 3' direction, and this conserved genomic organization is critical for their coordinated regulation [27].

The Phenomenon of Collinear Expression

The most striking feature of Hox gene biology is collinearity. During early embryogenesis, Hox genes are activated in a strict temporal sequence from the 3' end to the 5' end of each cluster [21] [25]. This "Hox clock" begins around embryonic day 7 (E7) in the posterior primitive streak of mouse embryos and unfolds over approximately two days, with Hox13 genes being the last to activate around E9 [21]. This temporal sequence is directly translated into spatial expression domains along the anterior-posterior axis, where 3' genes are expressed more anteriorly and 5' genes are restricted to posterior regions [21]. This spatiotemporal collinearity establishes a combinatorial Hox code that assigns unique positional identities to cells along the developing axes [27] [28].

Mechanistic Basis of Timing Control by Gene Positioning

Chromatin Dynamics and the Stepwise Transition Model

In embryonic stem cells, prior to activation, Hox clusters are maintained in a transcriptionally silent, bivalent chromatin state, characterized by the simultaneous presence of both repressive (H3K27me3) and activating (H3K4me3) histone marks [21] [25]. The sequential activation of genes is associated with a stepwise resolution of this bivalency. As each gene is activated in sequence, it undergoes a physical transition from a repressive Polycomb-associated chromatin compartment to an active one [21].

This transition is accompanied by a dramatic reorganization of the 3D chromatin architecture. Initially, the entire silent cluster is compacted into a single 3D compartment. Upon activation, a bimodal organization emerges: active genes, marked by H3K4me3, cluster together in one nuclear compartment, while inactive genes, marked by H3K27me3, are sequestered in a separate, repressive compartment [21]. This dynamic restructuring is intrinsic to the cluster and is thought to prevent premature activation of 5' genes while allowing the sequential, ordered deployment of the genetic code [21].

Diagram: The stepwise transition of Hox clusters from a single silent compartment to a bimodal active/inactive architecture. This structural change underlies temporal collinearity.

Bimodal Long-Range Regulation in the Limb

In the developing limb, the regulatory logic of the HoxA and HoxD clusters is particularly complex, involving a bimodal switch between two opposing topological associating domains (TADs) [15]. A TAD is a self-interacting genomic region where sequences within a TAD physically interact with each other more frequently than with sequences outside it.

- The Telomeric Domain (T-DOM): This TAD contains enhancers that drive the early phase of Hoxd gene expression in the presumptive stylopod (e.g., humerus) and zeugopod (e.g., radius/ulna) [15] [29].

- The Centromeric Domain (C-DOM): This TAD contains a different set of enhancers that control the later phase of Hoxd gene expression in the developing autopod (hand/foot) [15] [29].

Genes located at the 5' end of the HoxD cluster (like Hoxd13) interact primarily with the C-DOM. In contrast, genes located more centrally in the cluster (like Hoxd9, Hoxd10, Hoxd11) are targeted successively by both T-DOM and then C-DOM enhancers [15] [29]. The shift from T-DOM to C-DOM regulation is facilitated by HOX13 proteins themselves, which reinforce C-DOM activity while inhibiting T-DOM, locking the cell into a distal transcriptional program [15]. This bimodal system creates a zone of low Hoxd expression where both regulatory domains are silent, which subsequently forms the wrist and ankle joints [15].

Quantitative and Combinatorial Expression in Limb Patterning

The Hox Code for Limb Segments

The functional outcome of the complex regulation of Hox genes in the limb is a precise combinatorial code that specifies the identity of each limb segment along the proximal-distal axis. Genetic loss-of-function studies have demonstrated that different paralog groups are essential for the formation of different segments, revealing a striking specificity [26].

Table: Functional Roles of Hox Paralog Groups in Mouse Limb Patterning

| Paralog Group | Key Genes | Limb Segment Role | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox9 | Hoxa9, Hoxb9, Hoxc9, Hoxd9 | Initiation of AP Patterning | Failure to initiate Shh expression, disrupting anterior-posterior patterning [26]. |

| Hox10 | Hoxa10, Hoxc10 | Stylopod (Humerus/Femur) | Severe mis-patterning of the stylopod [26]. |

| Hox11 | Hoxa11, Hoxd11 | Zeugopod (Radius/Ulna, Tibia/Fibula) | Severe mis-patterning of the zeugopod [26]. |

| Hox13 | Hoxa13, Hoxd13 | Autopod (Hand/Foot) | Complete loss of autopod skeletal elements [26]. |

Single-Cell Heterogeneity and Transcriptional Dynamics

While large-scale expression studies suggest broad, homogeneous domains of Hox expression, single-cell transcriptomics and RNA-FISH have revealed a surprising degree of cellular heterogeneity. In the developing autopod, cells display a vast array of combinatorial expression of the five key Hoxd genes (Hoxd9 to Hoxd13), with some cells expressing only one gene and others expressing multiple genes in different ratios [29].

For instance, in E12.5 mouse limb buds, only a minority of cells in the autopod express Hoxd11 and/or Hoxd13. Among these positive cells, the largest fraction (53%) expresses Hoxd13 alone, while only 38% are double-positive for Hoxd11 and Hoxd13 [29]. This heterogeneity exists despite all these genes being under the control of the same set of global enhancers in the C-DOM, suggesting a stochastic or competitive element at the single-cell level. This combinatorial diversity at the cellular level may underpin the fine-grained patterning required to form complex skeletal structures like the digits [29].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols for Investigating Hox Regulation

Understanding the spatiotemporal control of Hox genes relies on a suite of sophisticated molecular and cellular techniques.

Chromatin Conformation Capture (3C and derivatives): This family of techniques (including 4C, Hi-C) is used to map the 3D architecture of genomes. It involves cross-linking chromatin, digesting it with restriction enzymes, and ligating DNA fragments that are in close physical proximity. High-throughput sequencing of these ligation products allows for the identification of long-range interactions, such as those between Hox gene promoters and their distal enhancers in the T-DOM and C-DOM [21]. This protocol was crucial in identifying the bimodal regulatory landscape of the HoxD cluster [15].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This method involves isolating single cells, reverse-transcribing their RNA into cDNA, and sequencing it. This allows for the quantification of gene expression levels from individual cells within a tissue, revealing the heterogeneity that is masked in bulk RNA-seq experiments. Applied to the limb bud, it has uncovered the diverse combinatorial codes of Hox gene expression in different mesenchymal progenitors [17] [29].

Spatial Transcriptomics: Techniques like the 10x Visium platform allow for the mapping of gene expression data onto tissue sections. This bridges the gap between single-cell resolution and anatomical context. A recent human embryonic limb cell atlas used this technology to spatially localize distinct mesenchymal populations and map the expression of HOXA and HOXD genes across the developing limb, confirming conservation with model organisms and providing unprecedented spatial resolution [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents and Models for Studying Hox Gene Regulation

| Reagent / Model | Function/Application | Key Insight Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxd11::GFP Reporter Mouse | Labels cells that have activated the Hoxd11 locus with GFP [29]. | Enabled FACS enrichment of Hoxd11-positive cells and revealed heterogeneity in Hoxd11/Hoxd13 co-expression. |

| T-DOM & C-DOM Deletion Mutants | Genetic deletion of entire regulatory landscapes flanking the HoxD cluster [15]. | Demonstrated the distinct and essential roles of each TAD in patterning proximal vs. distal limb segments. |

| Paralogous Group Mutants | Compound mutants lacking multiple genes within a Hox paralog group (e.g., Hoxa11-/-;Hoxd11-/-) [26]. | Revealed functional redundancy among paralogs and the specific requirement of each group for a given limb segment. |

| Anti-H3K27me3 / H3K4me3 Antibodies | Used in ChIP-seq to map repressive and active histone modifications [21]. | Characterized the bivalent state in ES cells and the stepwise resolution into active/inactive compartments during activation. |

Diagram: A multi-modal experimental workflow for dissecting Hox gene regulation, integrating single-cell, spatial, architectural, and genetic data.

Evolutionary and Translational Implications

Regulatory Variation Underlies Morphological Diversity

The bimodal regulatory system governing Hox genes in limbs is globally conserved across tetrapods; however, species-specific modifications contribute to morphological diversity. A comparison between mouse and chicken revealed differences in the activity of specific enhancers and the width of the TAD boundary separating the T-DOM and C-DOM [15]. In chicken hindlimbs, the duration of T-DOM regulation is shortened, correlating with reduced Hoxd gene expression and distinct zeugopod morphology compared to the forelimb [15]. Such variations in the timing and intensity of Hox regulatory activities, rather than changes in the protein-coding sequences themselves, are a major driver of evolutionary adaptation in limb morphology.

Implications for Congenital Limb Malformations

Decades of research in model organisms have established that precise spatiotemporal control of Hox gene expression is critical for normal limb development. A recent human embryonic limb cell atlas has confirmed the conservation of these principles in humans and provides a framework for understanding congenital limb malformations [17]. The atlas revealed a clear anatomical segregation between genes linked to brachydactyly (short digits) and polysyndactyly (extra/fused digits), underscoring how perturbations in the Hox-driven patterning network can lead to specific clinical phenotypes [17]. A deeper mechanistic understanding of how Hox gene positioning controls its timing and expression levels will therefore be essential for elucidating the etiology of these common birth defects and may inform future diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The Role of Bivalent Chromatin Marks in Maintaining Transcriptional Poise

Bivalent chromatin describes a specialized epigenetic state where segments of DNA, bound to histone proteins, contain both activating and repressing epigenetic regulators within the same genomic region [30]. This chromatin configuration is characterized by the simultaneous presence of histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), generally associated with transcriptionally active chromatin, and histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3), a mark of transcriptionally repressed chromatin [31] [32]. These opposing modifications most frequently occur at promoters of transcription factor genes that are expressed at low levels and are particularly abundant in pluripotent embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [32] [30].

The discovery of bivalent domains challenged the previous assumption that H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 were mutually exclusive [31]. While initial studies suggested these marks might coexist on the same histone tail, subsequent research established that they primarily occupy essentially nonoverlapping regions within bivalent domains, with H3K27me3 domains typically flanking H3K4me3 domains [31]. However, nucleosomes bearing both modifications on opposite H3 tails do exist in vivo [31]. This unique epigenetic configuration maintains associated genes in a transcriptionally repressed state, yet poised for rapid activation upon receiving developmental cues, representing a crucial mechanism for maintaining epigenetic plasticity during development [31].

Molecular Composition and Regulation

Key Molecular Components

The bivalent chromatin state is established and maintained through the coordinated action of antagonistic chromatin-modifying complexes:

Trithorax group (TrxG) complexes: These multi-protein complexes catalyze H3K4 trimethylation through SET1A, SET1B, or mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) proteins 1-4 [33]. MLL2 has been proposed as primarily responsible for H3K4 trimethylation at poised promoters [33]. The presence of H3K4me3 prevents permanent silencing by repelling transcription repressors and blocking repressive DNA methylation [31] [30].

Polycomb group (PcG) complexes: These form two primary complex types - Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) which catalyzes H3K27 trimethylation, and PRC1 which binds H3K27me3 and promotes further chromatin compaction through H2A ubiquitination or direct chromatin condensation [33]. The presence of H3K27me3 maintains transcriptional repression while keeping genes poised for activation [30].

The antagonistic relationship between these complexes creates a dynamic equilibrium that allows for rapid transcriptional switching. Recent evidence suggests that PRC2 activity is directly inhibited by H3K4me3 through allosteric regulation [31]. Additionally, ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers like SWI/SNF facilitate the resolution of bivalent states by hydrolyzing ATP to evict PcG proteins from bivalent chromatin [30].

Mutually Antagonistic Relationships

A fundamental characteristic of bivalent chromatin is the mutually antagonistic relationship between its constituent histone modifications and DNA methylation:

H3K4me3 and DNA methylation: These two modifications exhibit reciprocal inhibition [33]. H3K4me3 interferes with the recruitment and activity of DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B, while DNA methylation disrupts the recruitment of H3K4 methyltransferase complexes [33].

Protective function: This antagonism underlines the protective role of bivalent chromatin against irreversible silencing. The presence of H3K4me3 at bivalent promoters maintains DNA in a hypomethylated state, preserving transcriptional competence [31] [33].

Table 1: Key Molecular Components of Bivalent Chromatin

| Component | Type | Primary Function | Effect on Transcription |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Histone Modification | Catalyzed by TrxG proteins; promotes open chromatin | Activating (permissive) |

| H3K27me3 | Histone Modification | Catalyzed by PcG/PRC2; promotes condensed chromatin | Repressive |

| MLL2 (KMT2B) | Enzyme | Primary H3K4 methyltransferase at poised promoters | Establishes activating mark |

| PRC2 Complex | Enzyme Complex | Contains EZH1/2 which catalyze H3K27 methylation | Establishes repressive mark |

| SWI/SNF | Chromatin Remodeler | ATP-dependent eviction of PcG proteins | Facilitates bivalent resolution |

Figure 1: Developmental Transitions of Bivalent Chromatin States. Bivalent domains in ESCs resolve into either active or repressed univalent states during lineage commitment.

Bivalent Chromatin in Embryonic Development and Pluripotency

Role in Embryonic Stem Cells

Bivalent chromatin domains are particularly abundant in embryonic stem cells, where they play a crucial role in maintaining pluripotency while poising developmental genes for future activation [32] [30]. In ESCs, bivalent domains primarily silence developmental genes that would otherwise activate cell differentiation programs, while keeping these genes poised and ready for activation when differentiation signals are received [30]. When ESCs differentiate into specific lineages, the bivalent domains at relevant developmental genes resolve into either active (H3K4me3-only) or repressive (H3K27me3-only) states based on the chosen lineage [32].

Genome-wide studies have revealed that bivalently marked genes in ESCs are frequently transcription factors and important developmental regulators [32]. The resolution of these bivalent states during differentiation follows predictable patterns: genes necessary for the specific lineage become activated through loss of H3K27me3, while genes required for alternative lineages become stably repressed through loss of H3K4me3 [32]. For example, during neural differentiation, the neural regulator Nkx2.2 becomes active, the B-cell factor Pax5 becomes repressed, while Dixdc1 (involved in Wnt signaling) may retain its bivalent state for potential later activation [32].

Beyond Embryonic Stem Cells

While initially characterized in ESCs, bivalent chromatin is not restricted to pluripotent cells. Recent research has identified poised chromatin in various developmental contexts:

Germline cells: Mammalian germ cells maintain poised chromatin at promoters of developmental regulatory genes throughout gametogenesis, from fetal stages through meiosis [33]. This maintenance is hypothesized to prevent DNA methylation at key developmental promoters, maintain germ cell identity, and prepare for totipotency after fertilization [33].

Differentiated cells: Bivalent domains persist in terminally differentiated cell types, though their abundance is significantly reduced compared to ESCs [31] [34]. Embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells contain approximately twice as many bivalent segments as differentiated tissues, while cancer cell lines show the smallest numbers [34].

Table 2: Prevalence of Bivalent Chromatin Across Cell Types

| Cell Type | Relative Abundance of Bivalent Domains | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | High (~2× differentiated cells) | Maintain pluripotency; poise developmental genes |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | High | Re-establish pluripotency network |

| Differentiated Somatic Cells | Moderate | Tissue-specific regulation; maintained plasticity |

| Germline Cells | Moderate to High | Preserve totipotency; prevent DNA methylation |

| Cancer Cell Lines | Low | Loss of developmental regulation |

Bivalent Chromatin and Hox Gene Regulation in Limb Development

Hox Gene Expression During Limb Patterning

Hox genes encode an evolutionarily conserved family of transcription factors that play essential roles in patterning the anterior-posterior (AP) body axis and directing limb development [26] [35]. In tetrapods, the vertebrate limb is organized into three main segments: the proximal stylopod (humerus/femur), the medial zeugopod (radius/ulna or tibia/fibula), and the distal autopod (carpals/tarsals and digits) [26] [36]. The posterior Hox paralog groups (Hox9-13) are particularly important for patterning the limb skeleton along the proximodistal (PD) axis [26].

Hox genes exhibit a remarkable genomic organization and regulatory logic. They are arranged in four clusters (HoxA-D) in mammals, with their order within each cluster reflecting their temporal and spatial expression patterns during development - a phenomenon known as collinearity [21] [37]. During limb development, Hox genes are expressed in two distinct phases [35]. The early phase involves collinear activation similar to trunk patterning, while the later phase displays distinct regulation that may have evolved separately after cluster duplications [35].

3D Chromatin Architecture and Bivalent Regulation

The regulation of Hox genes during limb development involves sophisticated 3D chromatin architecture that incorporates bivalent chromatin states:

Pre-activation state: In embryonic stem cells, before Hox gene activation, entire Hox clusters are organized into single chromatin compartments containing all genes with bivalent chromatin marks [21]. At this stage, Hox genes are transcriptionally silent but epigenetically poised.

Bimodal organization during activation: Transcriptional activation of Hox genes during limb development is associated with a dynamic bi-modal 3D organization, where individual genes switch autonomously from an inactive to an active compartment [21]. This transition occurs within constitutive topological associated domains (TADs) that frame the Hox clusters [21].

Regulatory landscapes: At the HoxD locus, two partially overlapping gene subsets are controlled by enhancers located in distinct TADs - either telomeric (T-DOM) or centromeric (C-DOM) to the cluster [36]. The region from Hoxd1 to Hoxd8 constitutively interacts with T-DOM, while the 5' region including Hoxd13 to Hoxd12 predominantly contacts C-DOM [36].

The step-wise transcriptional activation of Hox genes follows their genomic topology and is associated with resolving the initial bivalent state into either active (H3K4me3-rich) or repressed (H3K27me3-rich) chromatin states [21]. This process creates a spatial organization where active genes cluster together and are physically separated from inactive genes within the 3D nuclear space [21].

Figure 2: 3D Chromatin Organization of Hox Gene Clusters During Limb Development. Hox genes are regulated through interactions with distinct topological domains that correlate with proximal versus distal limb patterning.

Functional Evidence from Limb Patterning

Functional studies have demonstrated the critical role of Hox genes in limb patterning, with different paralog groups controlling specific limb segments:

- Hox10 paralogs: Required for proper stylopod (proximal segment) patterning [26]

- Hox11 paralogs: Essential for zeugopod (medial segment) development [26]

- Hox13 paralogs: Necessary for autopod (distal segment) formation [26]

The functional importance of Hox genes in limb development is further evidenced by the severe limb truncations observed when multiple posterior HoxA and HoxD genes are simultaneously inactivated [26]. Additionally, Hox genes regulate key signaling centers in the developing limb, including the Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA) through control of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) expression [35] [37].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Bivalent Chromatin

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Protocol Overview: ChIP-seq is the primary method for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites [31].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cross-linking: Cells are fixed with formaldehyde to covalently link proteins to DNA

- Chromatin Fragmentation: DNA is sheared by sonication to 200-500 bp fragments

- Immunoprecipitation: Specific antibodies against H3K4me3 or H3K27me3 enrich for chromatin fragments containing these modifications

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Immunoprecipitated DNA is purified, converted to a sequencing library, and analyzed by high-throughput sequencing

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence reads are aligned to reference genome, peaks are called for enriched regions, and bivalent domains are identified as genomic regions with significant enrichment for both marks

Key Considerations: Antibody specificity is critical; controls include input DNA (no immunoprecipitation) and validation with known positive and negative genomic regions [31].

Circular Chromosome Conformation Capture (4C)

Protocol Overview: 4C sequencing identifies long-range chromatin interactions, particularly useful for studying 3D organization of Hox clusters [21].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cross-linking: Cells are fixed with formaldehyde to preserve chromatin interactions

- Restriction Digestion: DNA is digested with a primary restriction enzyme

- Ligation under Dilute Conditions: Promotes intramolecular ligation of cross-linked fragments

- Second Restriction Digestion: Increases resolution using a different restriction enzyme

- Second Ligation: Creates circular DNA molecules for inverse PCR

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplification and sequencing of interaction fragments

- Data Analysis: Identifies genomic regions interacting with a specific "viewpoint" such as a Hox gene promoter

Application: This technique revealed the bimodal compartmentalization of active and repressed Hox genes during embryonic development [21].

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches

Contemporary studies increasingly employ integrated approaches combining:

- RNA-seq: For transcriptional profiling

- Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS): For DNA methylation analysis

- CHi-C (Capture Hi-C): For high-resolution chromatin interaction mapping

- ATAC-seq: For assessing chromatin accessibility

This integrated methodology enables comprehensive characterization of the relationships between bivalent chromatin states, 3D genome architecture, and gene expression patterns during limb development and disease states [34] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bivalent Chromatin

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3 | Immunoprecipitation of bivalent chromatin regions for ChIP-seq |

| Chromatin Assembly Kits | Micrococcal Nuclease, Covaris Shearing Systems | Chromatin fragmentation and preparation for sequencing assays |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel | High-throughput sequencing of immunoprecipitated DNA |

| Bioinformatic Tools | MACS2 (peak calling), HOMER, ChIPseeker | Identification and annotation of bivalent domains from sequencing data |

| Epigenetic Modulators | UNC1999 (EZH2 inhibitor), MM-102 (MLL1 inhibitor) | Functional perturbation of histone modifying enzymes |

| Cell Culture Systems | Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs, hESCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells | Model systems for studying bivalent chromatin dynamics |

| In Vivo Model Systems | Mouse knockout models (Hox cluster mutants), Chick electroporation | Functional validation of bivalent chromatin in development |

Bivalent Chromatin in Disease and Cancer

The proper regulation of bivalent chromatin is crucial for normal development, and its disruption is increasingly implicated in disease states, particularly cancer:

DNA hypermethylation in cancer: Bivalent promoters, while hypomethylated in normal cells, show a strong predisposition to hypermethylation in cancer [31] [34]. Genome-wide studies reveal that bivalent chromatin regions show hypermethylation in various cancers, including lymphoma, leukemia, and medulloblastoma [34].

Counterintuitive expression patterns: Contrary to the conventional understanding that DNA hypermethylation leads to transcriptional silencing, many genes controlled by hypermethylated bivalent promoters in cancer show increased expression levels [34]. This positive correlation between DNA methylation and expression affects numerous developmental genes and transcription factors, including homeobox genes implicated in cancer [34].

Loss of bivalency in cancer: Cancer cell lines show significantly fewer bivalent segments compared to normal cells, with only approximately 28% of frequently bivalent segments (FBSs) maintaining bivalency in cancer versus 87% in normal cells [34]. This suggests a systematic disruption of bivalent chromatin marks during tumorigenesis.

Therapeutic implications: The vulnerability of bivalent domains to aberrant methylation in cancer suggests they may serve as biomarkers for early detection or therapeutic targets [31] [34]. A universal classifier built from chromatin data can identify cancer samples with 92% accuracy (AUC=0.92) based solely on hypermethylation of bivalent chromatin [34].

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The study of bivalent chromatin continues to evolve, with several promising research directions emerging:

Single-cell epigenomics: Current bulk sequencing methods provide population averages, potentially masking cell-to-cell heterogeneity. Single-cell ChIP-seq and multi-omics approaches will reveal how bivalent chromatin states vary within apparently homogeneous cell populations.