Troubleshooting High Background in In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Guide for Clear Signals

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and resolve high background fluorescence and nonspecific staining in in situ hybridization (ISH) assays.

Troubleshooting High Background in In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Guide for Clear Signals

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose and resolve high background fluorescence and nonspecific staining in in situ hybridization (ISH) assays. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, it details common error sources from sample preparation to detection, offers step-by-step optimization protocols for both CISH and FISH, and explores the integration of automated platforms and AI-powered analysis to enhance assay robustness and reproducibility in biomedical research.

Understanding ISH Background: Defining the Problem and Its Common Sources

High Background? Differentiating Signal from Noise in CISH and FISH

What is High Background?

In both Chromogenic and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (CISH and FISH), "high background" refers to unwanted, non-specific signal that obscures the true, target-specific hybridization signal. This noise complicates analysis and can lead to erroneous interpretation of experimental results [1].

In CISH, this typically manifests as a diffuse, general staining across the tissue section, making it difficult to distinguish the specific precipitate formed by enzymes like Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [2]. In FISH, high background appears as a haze or speckling of fluorescence across the sample, including on non-target cells or mineral particles, which can mask the true fluorescent signals from your probe [1] [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Causes and Solutions

The table below summarizes the frequent causes of high background in CISH and FISH experiments and the recommended corrective actions.

| Problem Area | Common Causes of High Background | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Under-fixation or over-fixation; incorrect section thickness; delayed fixation [2] [1] [4]. | Use freshly prepared fixatives; adhere to recommended fixation times; aim for 3-4μm thick FFPE sections [1] [5] [4]. |

| Pre-treatment | Insufficient or over-digestion with protease (e.g., pepsin, Proteinase K) [2] [6]. | Titrate enzyme concentration and time. A typical start is 1-5 μg/mL Proteinase K for 10 min at room temperature [6]. |

| Probe Hybridization | Denaturation temperature/time incorrect; probe concentration too high; probe drying on slide [2] [1] [4]. | Ensure denaturation at 95±5°C for 5-10 min; prevent reagent evaporation during incubation [2] [1]. |

| Washing Stringency | Inadequate stringent wash; use of incorrect wash buffers or temperature [2] [1]. | For CISH, use 1X SSC at 75-80°C. Optimize wash stringency by adjusting pH, temperature, and salt concentration [2] [1] [6]. |

| Detection | Endogenous biotin activity; enzyme-substrate mismatch; reaction development too long [2] [6]. | Block endogenous biotin; ensure conjugate matches substrate (e.g., HRP with DAB); stop chromogenic reaction once signal appears [2] [6]. |

Specialized Protocol: EDTA-FISH for Mineral-Rich Samples

Environmental samples like sediments are prone to high background due to non-specific probe adsorption to mineral particles. The EDTA-FISH protocol effectively counters this [3].

- Background: Standard FISH buffers use 0.9 M NaCl, which does not prevent probe adsorption to mineral grains.

- Solution: Replace 0.9 M NaCl in the hybridization buffer with 250 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). The EDTA chelates divalent cations that facilitate probe binding to mineral surfaces, drastically reducing background without compromising specific cell-bound signals [3].

- Key Consideration: This buffer change slightly alters hybridization stringency, so the optimal formamide concentration must be re-established probe-by-probe [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key Optimizations

Protocol 1: Optimizing Proteinase K Digestion for Tissue Permeabilization

Proteinase K digestion is a critical pre-treatment step. Insufficient digestion masks targets, while over-digestion damages morphology and increases background [6].

- Prepare a titration series: Test a range of Proteinase K concentrations (e.g., 1, 2, 5, 10 µg/mL) on consecutive tissue sections while keeping time and temperature constant (e.g., 10 minutes at room temperature) [6].

- Run the ISH assay: Perform the entire ISH protocol with your probe of choice on the titrated sections.

- Evaluate results: The optimal concentration produces the highest specific hybridization signal with the least disruption of tissue or cellular morphology [6].

Protocol 2: Performing a Stringent Wash for CISH

An improper stringent wash is a primary cause of high DAB background in CISH [2].

- After hybridization, rinse slides briefly at room temperature with SSC buffer.

- Immerse slides in pre-warmed SSC buffer for 5 minutes. The critical parameter is maintaining a temperature between 75-80°C.

- If processing multiple slides, increase the temperature by approximately 1°C per slide, but do not exceed 80°C. Temperatures higher than this can eliminate the specific CISH signal [2].

- After the wash, rinse the slides with the appropriate buffer (e.g., TBST). Avoid using water or PBS without detergent, as this can increase background [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: My probe contains repetitive sequences (like Alu elements), which is causing high background. What can I do? A: You can block probe binding to these repetitive sequences by adding unlabeled COT-1 DNA to the hybridization mixture [2].

Q: Why should I avoid a dark hematoxylin counterstain in CISH? A: A dark counterstain can mask the positive signal, especially with brown DAB or dark blue NBT/BCIP precipitates. Use a light counterstain (e.g., 5 seconds to 1 minute in Mayer's hematoxylin) for better contrast [2].

Q: For FFPE tissue FISH, what is the key to optimizing denaturation conditions? A: Follow the probe manufacturer's protocol precisely. Using a temperature that is too low prevents probe binding, while a temperature that is too high increases non-specific binding. The duration is also critical; prolonged denaturation can unmask non-specific binding sites [1].

Q: I am using biotin-labeled probes and getting high background. What are my options? A: Endogenous biotin is a common cause. You can either:

- Block endogenous biotin by adding excess avidin or streptavidin prior to probe hybridization.

- Switch labels and use digoxigenin-labeled probes, as digoxigenin is not endogenously produced in mammalian tissues, offering higher specificity [6].

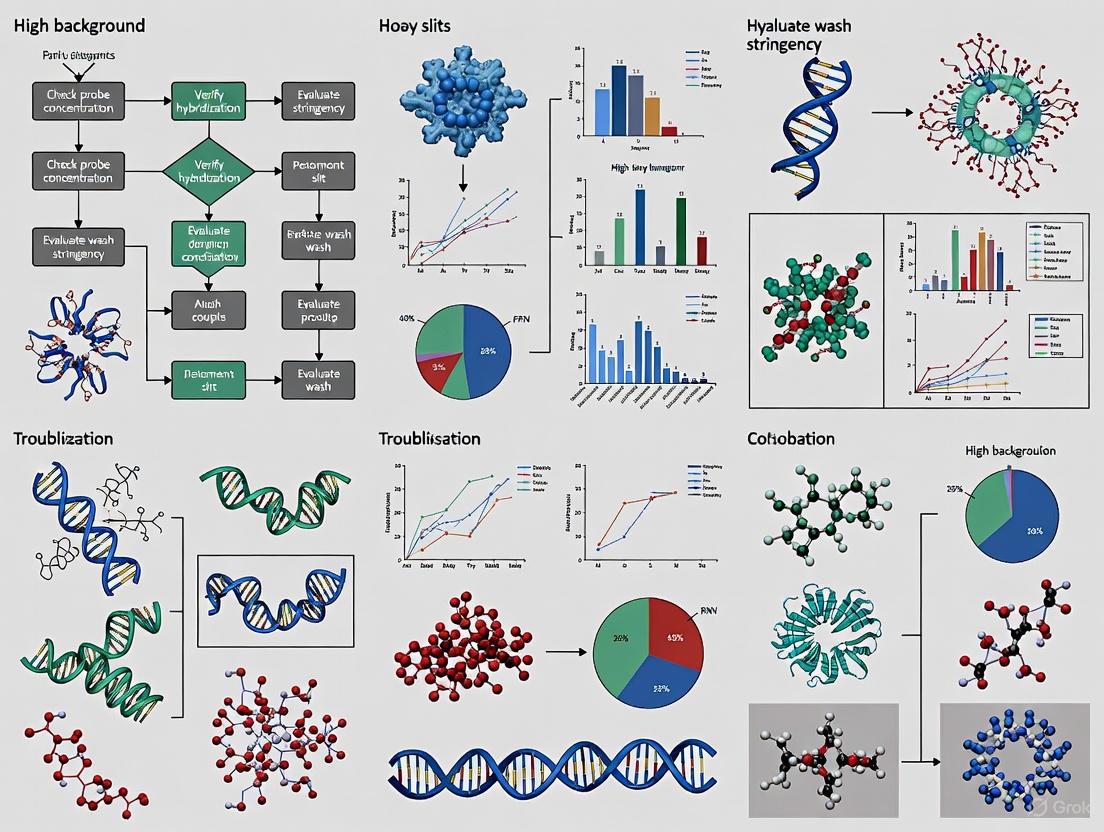

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the parallel pathways that lead to either specific signal or non-specific background noise in a typical CISH/FISH assay, highlighting key control points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and materials for troubleshooting and optimizing your CISH and FISH assays.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Charged Slides | Provides superior section adhesion, preventing section lifting which can cause uneven staining and high background [4]. |

| Pepsin or Proteinase K | Enzymes for antigen retrieval. Concentration and time must be titrated for each tissue type; crucial for balancing signal and background [2] [6]. |

| Formamide | Component of hybridization buffer. Allows hybridization to occur at lower temperatures, helping to preserve tissue morphology [6] [5]. |

| SSC Buffer (Saline-Sodium Citrate) | Standard buffer for stringent washes. Using it at the correct temperature (75-80°C) is vital for removing non-specifically bound probe [2]. |

| COT-1 DNA | Unlabeled DNA used to block repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu, LINE) in the genome, reducing non-specific probe binding and background [2]. |

| EDTA (for EDTA-FISH) | A chelating agent that, when used at high concentration (e.g., 250 mM) in place of NaCl in the hybridization buffer, reduces probe adsorption to mineral particles in environmental samples [3]. |

| Tween 20 | A detergent added to wash buffers (e.g., PBST). Its omission can lead to elevated background staining [2]. |

| Histomount Mounting Medium | A specific mounting medium recommended for chromogenic sections to preserve the signal and clarity when applying coverslips [2]. |

What are the primary probe-related causes of high background?

Probe-related issues are a frequent source of high background staining in ISH experiments. The table below summarizes the key culprits and their solutions.

Table 1: Probe-Related Causes and Solutions for High Background

| Culprit | Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Repetitive Sequences | Probes containing Alu or LINE elements cause non-specific binding [2] | Add COT-1 DNA during hybridization to block repetitive sequences [2] |

| Probe Concentration | Too concentrated probe increases non-specific hybridization [7] | Titrate probe to find optimal concentration; avoid excessive amounts [7] |

| Probe Specificity | Poorly designed probes with low specificity for target [4] | Carefully select probes with high sensitivity and specificity for your target [4] |

| Probe Labeling Issues | Improperly labeled or degraded probes [7] | Use fresh, properly validated probes with appropriate labeling techniques [7] |

How do sample preparation errors contribute to background issues?

Improper sample preparation can significantly increase background staining by creating conditions favorable for non-specific probe binding.

Table 2: Sample Preparation-Related Causes and Solutions

| Culprit | Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Permeabilization | Insufficient access to target nucleic acids [7] | Optimize proteinase K concentration (3-10 min at 37°C for most tissues); avoid over-digestion [2] |

| Improper Fixation | Over-fixation causes excessive protein cross-linking [2] | Standardize fixation conditions (type, pH, temperature, time) across all samples [4] |

| Section Drying | Tissue drying during processing causes non-specific binding [2] | Ensure sections remain hydrated throughout the entire protocol [2] |

| Incomplete Dewaxing | Residual paraffin prevents proper reagent penetration [4] | Ensure complete paraffin removal during dewaxing steps [4] |

Which hybridization and washing conditions most commonly cause high background?

Suboptimal hybridization and washing conditions represent the most frequent technical causes of high background in ISH experiments.

Critical Hybridization Factors:

- Stringency Washes: Insufficient stringent washing is a major cause of high background [2]. Use SSC buffer at 75-80°C for 5 minutes, increasing temperature by 1°C per additional slide (maximum 80°C) [2].

- Evaporation Control: Drying of probe or reagents during hybridization causes heavy, non-specific staining at edges [4]. Use proper humidified chambers and ensure adequate hydration throughout incubation [2].

- Temperature Consistency: Hybridization should be conducted at precisely 37°C [2]. Temperature fluctuations dramatically impact specificity.

What detection system problems lead to excessive background?

The detection phase introduces multiple potential sources of background, particularly when using enzymatic detection methods.

Table 3: Detection System Causes and Solutions for High Background

| Culprit | Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-Development | Excessive chromogen incubation produces nonspecific precipitation [2] | Monitor development microscopically; stop reaction immediately when background appears [2] |

| Endogenous Enzyme Activity | Unblocked peroxidase or phosphatase activity [7] | Include enzymatic blocking steps during prehybridization [7] |

| Conjugate Mismatch | Mismatched probe label and detection system [2] | Ensure conjugates match probes (biotin with anti-biotin) and enzymes match substrates (HRP with DAB) [2] |

| Antibody Concentration | Too high antibody concentration in detection system [8] | Titrate detection antibodies to optimal concentration [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Background Reduction

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Specific Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| COT-1 DNA | Blocks repetitive sequences in probes [2] | Essential when probes contain Alu or LINE elements [2] |

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins surrounding target nucleic acids [7] | Optimal concentration critical; 3-10 min at 37°C for most tissues [2] |

| SSC Buffer | Provides proper stringency in post-hybridization washes [2] | Use at 75-80°C for 5 minutes for effective background reduction [2] |

| PBST with Tween-20 | Washes with detergent minimize hydrophobic interactions [2] | Critical: Using PBS without Tween-20 or distilled water increases background [2] |

| Enzyme Blocking Reagents | Quenches endogenous enzyme activity [7] | Essential when using enzymatic detection systems [7] |

| Formamide | Increases stringency in hybridization buffer [7] | Reduces non-specific hybridization; concentration must be optimized [7] |

FAQs on Sample Preparation for In Situ Hybridization

1. How does fixation time affect my ISH results? Both under-fixation and over-fixation can severely compromise your ISH results. Under-fixation fails to preserve cellular structure and nucleic acids adequately, leading to degradation and high background staining. Over-fixation, particularly with formalin, causes excessive cross-linking of proteins and nucleic acids, which can mask your target sequences and reduce probe accessibility, also resulting in poor signal and elevated background [9]. Adhere strictly to recommended fixation times.

2. What is the most common cause of high background staining? Insufficient washing during the post-hybridization steps is a frequent culprit for high background [2]. However, other factors include too high a probe concentration, inadequate digestion during pre-treatment, insufficient blocking, or letting tissue sections dry out during the procedure [8] [10]. A systematic approach to troubleshooting is needed to identify the specific cause.

3. Why is my staining weak or absent even though my probe is valid? Weak or absent staining can result from several preparation issues. These include RNA degradation due to delayed fixation or RNase contamination [4], over-digestion with proteases like proteinase K which damages tissue morphology [10], or insufficient antigen retrieval which leaves target sequences masked [11] [12]. Ensure proper tissue handling and optimize pre-treatment steps.

4. How can I reduce background in fluorescent ISH (FISH) assays? To reduce background in FISH, ensure the use of freshly prepared fixative and wash buffers [9]. Optimize the stringency of your post-hybridization washes by carefully controlling temperature and salt concentration [10] [2]. Also, for FFPE tissues, use thin sections (3-4μm) to avoid issues with probe penetration, and consider using a hypotonic solution during the fixation of blood smears [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: High Background in ISH

The following table outlines common problems related to sample preparation that lead to high background, along with their specific solutions.

| Problem | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Staining | Over-fixation or under-fixation [9] | Standardize fixation conditions; for formalin, use 10% NBF and adhere closely to recommended fixation times [4] [9]. |

| Insufficient proteinase K digestion [10] | Perform a titration experiment to determine the optimal concentration and time for your specific tissue type and fixation [10]. | |

| Tissue sections drying out [8] | Use a humidified chamber during all incubation steps and never allow slides to dry out [8] [2]. | |

| Inadequate post-hybridization washes [2] | Use standardized, stringent washes (e.g., with SSC buffer at 75–80°C) to remove unbound probe [10] [2]. | |

| Uneven or Patchy Staining | Incomplete removal of paraffin [4] | Follow a rigorous deparaffinization protocol with fresh xylene and ethanol series [10]. |

| Inconsistent reagent coverage [8] | Ensure reagents fully cover the tissue section and use a humidified chamber to prevent evaporation [8] [4]. | |

| Poor section adhesion [4] | Use charged slides and avoid protein-based adhesives that can block the slide surface [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Sample Preparation

Protocol 1: Standard Fixation and Pre-treatment for FFPE Tissues

This methodology is critical for preserving nucleic acid integrity and ensuring optimal probe access [10] [9].

- Fixation: Immerse tissue promptly in a sufficient volume of 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF). Fixation time should be standardized and consistent; 24 hours is a common starting point, but optimal duration may vary by tissue type [9] [12].

- Processing & Embedding: Process fixed tissues through a graded series of ethanol for dehydration, followed by xylene (as a clearing agent), and finally infiltrate and embed in paraffin wax [12].

- Sectioning: Cut thin sections (3–5 μm) using a microtome and mount on charged slides to ensure adhesion. Dry slides thoroughly [4] [9].

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration:

- Xylene: 2 x 3 min

- Xylene:1:1 with 100% ethanol: 3 min

- 100% ethanol: 2 x 3 min

- 95% ethanol: 3 min

- 70% ethanol: 3 min

- 50% ethanol: 3 min [10]

- Permeabilization/Antigen Retrieval: Digest with 20 μg/mL proteinase K in pre-warmed 50 mM Tris buffer for 10–20 minutes at 37°C. Note: Concentration and time must be optimized for each tissue and fixation condition via titration [10].

Protocol 2: Proteinase K Titration Experiment

This experiment is essential for optimizing the permeabilization step, which is a common source of both high background and weak signal [10].

- Objective: To determine the optimal proteinase K concentration that maximizes signal while preserving tissue morphology.

- Method:

- Prepare a series of proteinase K solutions in 50 mM Tris buffer (e.g., 0, 5, 10, 20, 40 μg/mL).

- Apply each concentration to consecutive tissue sections and incubate at 37°C for a fixed time (e.g., 15 minutes).

- Stop the reaction by rinsing slides 5x in distilled water.

- Proceed with the remainder of your ISH protocol uniformly for all slides.

- Evaluation: Examine slides under a microscope. The optimal condition will show strong specific staining with minimal background and well-preserved tissue structure. Insufficient digestion yields weak signal; over-digestion results in poor morphology and high background [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used in ISH sample preparation and their critical functions.

| Reagent | Function in Sample Preparation |

|---|---|

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue architecture and nucleic acids by forming methylene bridges between proteins [12]. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme that digests proteins surrounding the target nucleic acids, thereby unmasking the targets and allowing probe access [10]. |

| Formamide | A denaturing agent used in hybridization buffers. It lowers the effective melting temperature of the probe, allowing for specific hybridization at manageable temperatures [10] [13]. |

| Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) Buffer | A salt buffer used in hybridization and stringent washes. The salt concentration (stringency) and temperature of SSC washes are critical for removing non-specifically bound probe to reduce background [10] [2]. |

| Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled Probes | Hapten-labeled nucleic acid probes. After hybridization, they are detected with an anti-DIG antibody conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., alkaline phosphatase) for colorimetric or fluorescent detection [10]. |

Workflow: Impact of Sample Preparation on ISH Results

This diagram illustrates the cause-and-effect relationship between sample preparation steps and experimental outcomes.

Proactive Practices for Robust ISH

To ensure consistent success with your ISH experiments, integrate these core principles into your standard workflow:

- Standardize and Control: Use consistent fixation conditions (type, pH, time, temperature) across all samples. Always include known positive and negative control tissues in every run to validate your protocol and results [4] [2].

- Prevent RNase Contamination: Use RNase-free reagents, gloves, and sterile techniques during all procedures involving RNA detection. Degraded RNA is a primary cause of signal failure [10] [4].

- Optimize Systematically: Critical steps like protease digestion and hybridization stringency require empirical optimization for each new tissue type, fixation protocol, and probe. Use titration experiments rather than relying on generic protocols [10] [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the primary causes of high background signal in my ISH experiment?

High background, or non-specific signal, can stem from various probe-related and procedural issues. Key causes include:

- Probe Design: Probes containing repetitive sequences (like Alu or LINE elements) can bind non-specifically, elevating background. This can be mitigated by adding blocking DNA like COT-1 during hybridization [2].

- Insufficient Washes: Inadequate stringency during post-hybridization washes is a common cause of high background. Washes must be performed at the correct temperature and pH to remove weakly bound, non-specific probes [2] [14] [5].

- Sample Over-fixation: Over-fixation with formalin can create excessive cross-linking, which masks target sequences and leads to non-specific probe binding and higher background [14].

- Probe or Reagent Drying: Allowing the probe or other reagents to dry onto the slide, particularly at the edges, causes heavy, non-specific staining [4].

- Incorrect Wash Buffers: Using distilled water or PBS without detergent (e.g., Tween 20) for washing steps can result in elevated background. The correct buffers, such as PBST, are essential [2].

Q: How can I improve the specificity and labeling efficiency of my probes?

Improving specificity and efficiency involves optimizing probe design, labeling methods, and using appropriate tags.

- Evaluate Labeling Efficiency: For precise quantification of how well your binders (e.g., antibodies, nanobodies) label the target, use a reference tag strategy. A molecular construct with a reference tag fused to your target protein allows you to correlate signals and calculate absolute labeling efficiency at the single-molecule level [15].

- Choose Conjugation Methods Carefully: The method used to conjugate dyes or other labels to your primary antibodies significantly impacts efficiency. For instance, enzymatic site-specific conjugation (e.g., transglutaminase vs. GlyCLICK) can lead to stark differences in labeling efficiency for the same antibody [15].

- Combine Tags and Binders: To boost overall labeling efficiency, consider concatenating multiple tags (e.g., GFP and ALFA-tag) on your target and using a combination of binders specific to each tag [15].

- Select the Right Probe Type: DNA probes are generally easy to prepare and work with, while single-stranded RNA probes can form more stable hybrids and achieve high label incorporation, which can enhance specificity [5].

Q: My negative controls are showing a signal. What does this indicate and how can I fix it?

Signal in negative controls points to non-specific binding or background staining.

- Confirm Probe Specificity: Ensure your negative control uses a verified non-specific probe. Signal with this probe indicates a fundamental issue with probe specificity or assay conditions [4].

- Optimize Hybridization Stringency: The hybridization temperature and buffer composition are critical. Temperature that is too low prevents specific binding, while temperature that is too high can promote non-specific binding. Typically, a range between 55°C and 62°C is used, and formamide in the buffer helps maintain morphology at lower temperatures [5].

- Check for Probe Contamination: Always use high-quality, purified DNA free of contaminants to synthesize probes. Change solutions frequently and use dedicated equipment to avoid cross-contamination [5].

- Verify Enzyme Activity: If using enzymatic detection, confirm that the enzyme conjugate is active by mixing a drop of conjugate with a drop of substrate. A color change should occur within minutes [2].

Q: What are the best practices for handling and storing probes to maintain their performance?

Proper handling and storage are crucial for preserving probe integrity and performance.

- Prevent Degradation: Protect probes from light exposure, especially fluorescently labeled ones, to prevent photobleaching [14].

- Ensure Purity: After probe synthesis, purify the probe to remove unincorporated nucleotides. Verify the yield, dye incorporation, and fragment length (e.g., a smear of 100-250 bp for DNA probes) to ensure quality [5].

- Use Fresh Buffers: Always use freshly prepared wash and fixation solutions. Degraded or contaminated buffers can fail to remove non-specifically bound probes and introduce background fluorescence [14].

- Store Appropriately: For some fixatives like Carnoy's solution, store at -20°C and discard after use to maintain effectiveness [14].

Quantitative Data on Labeling Efficiency

The table below summarizes absolute labeling efficiencies for various nanobodies and conjugation strategies, as determined by a single-protein level quantification method [15].

Table 1: Quantified Labeling Efficiencies of Common Binders

| Target Tag | Binder (Clone) | Labeling Efficiency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFP | Nanobody (1H1) | ~50% | — |

| GFP | Nanobody (1H1 + 1B2) | 62% ± 5% | Combination of two clones targeting different epitopes |

| GFP + ALFA-tag | Nanobody (1H1+1B2) + ALFA-tag Nanobody | 76% ± 8% | Combined tags and binders on a single construct |

| mEOS2 | Nanobody (1E8) | <10% | — |

| CD80 | Antibody (Transglutaminase conjugation) | Varies | Efficiency is antibody-dependent |

| CD80 | Antibody (GlyCLICK conjugation) | ~7x lower | Stark difference for this specific antibody |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Absolute Labeling Efficiency at the Single-Protein Level

This protocol enables precise measurement of binder labeling efficiency in a cellular context, crucial for quantitative interpretation of super-resolution data [15].

- Molecular Construct Design: Design a construct where your protein of interest (POI) is fused to a reference tag (e.g., ALFA-tag) at one terminus (N- or C-). The tag for which you want to test labeling efficiency (the target tag) is fused to the other terminus.

- Cell Transfection: Transiently transfect your cells with the constructed plasmid.

- Labeling: Label the sample with binders for both the reference tag and the target tag. These binders are conjugated to DNA strands for subsequent Exchange-PAINT imaging.

- Sequential Imaging: Perform a two-target Exchange-PAINT super-resolution experiment to independently resolve the locations of the reference and target binders with single-molecule sensitivity.

- Data Analysis:

- Cluster Identification: Apply a cluster algorithm to identify individual molecules from clouds of localizations.

- Cross Nearest Neighbor Distance (NND): Calculate the cross NND from each reference signal to its nearest target binder.

- Simulation and Fitting: Simulate reference and target molecules at the same experimental density for a range of possible labeling efficiencies. Find the most likely labeling efficiency by performing a least-squares minimization fit between the experimental and simulated NND histograms. Labeling efficiency is calculated as NRef+Target / (NRef + N_Ref+Target).

Protocol 2: Reducing High Background in FISH Assays

A step-by-step guide to troubleshoot and minimize background fluorescence [2] [4] [14].

Sample Preparation and Fixation:

- Use thin tissue sections (3-4 μm for FFPE) to ensure proper probe penetration [14] [5].

- Fix tissues promptly with freshly prepared formalin or paraformaldehyde. Avoid over-fixation (do not exceed 24 hours) or under-fixation, as both can increase background [14].

- For blood smears, use a hypotonic solution (e.g., potassium chloride) during fixation to reduce background [14].

Pretreatment and Permeabilization:

- Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval by heating sections in pretreatment buffer at 98°C for 15-30 minutes, depending on tissue type [2] [14].

- Digest with pepsin at 37°C for 3-10 minutes. Optimize this time for your specific tissue, as over-digestion can damage the sample and under-digestion can decrease signal [2].

- Ensure slides do not dry out at any point during pretreatment [2].

Denaturation and Hybridization:

Stringent Washes:

- After hybridization, rinse slides briefly at room temperature with SSC buffer.

- Perform a stringent wash by immersing slides in SSC buffer at 75°C for 5 minutes. Increase the temperature by 1°C per slide if washing more than 2 slides, but do not exceed 80°C [2].

- Rinse with TBST or PBST afterward. Do not use water or plain PBS, as this can cause background [2].

Detection and Counterstaining:

- Incubate with the enzyme conjugate (e.g., HRP) at 37°C for 30 minutes, then rinse with PBS.

- Develop the signal with a chromogenic substrate (e.g., DAB). Monitor the reaction under a microscope at 2-minute intervals and stop the reaction by rinsing with distilled water as soon as background begins to appear [2].

- Apply a light counterstain (e.g., Mayer's hematoxylin for 5-60 seconds) to avoid masking the specific signal [2].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Workflow for Quantifying Labeling Efficiency

Probe Design and Specificity Considerations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for ISH Troubleshooting

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| COT-1 DNA | Blocks binding to repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu, LINE) to reduce background [2]. | Must be added during the hybridization step. |

| Charged Slides | Provides strong adhesion for tissue sections, preventing lift-off and uneven staining [4]. | Avoid protein-based adhesives on charged slides. |

| Formamide | Component of hybridization buffer; allows for lower hybridization temperatures, preserving tissue morphology [5]. | Typical concentration in buffer is 50%. |

| PNGase F & Transglutaminase | Enzymes for site-specific, Fc-targeted conjugation of DNA to primary antibodies [15]. | Labeling efficiency is highly dependent on the antibody and conjugation strategy. |

| Pepsin / Trypsin | Proteases for tissue digestion; unmask target nucleic acids by breaking cross-links from fixation [2] [5]. | Digestion time (3-10 min at 37°C) must be optimized for each tissue type. |

| Stringent Wash Buffer (SSC) | Removes non-specifically bound probes after hybridization. Critical for reducing background [2]. | Temperature must be tightly controlled (75-80°C). |

| Tween 20 (in PBST) | Detergent added to wash buffers; prevents non-specific hydrophobic interactions that cause background [2]. | Concentration of 0.025% is typical. |

| Histomount Mounting Medium | A non-aqueous, permanent mounting medium that preserves the stained section for imaging [2]. | Apply to wet sections, avoiding bubbles. |

What are the primary causes of high background in my in situ hybridization experiment?

High background staining in ISH experiments is frequently caused by two main categories of endogenous biomolecules: those that cause autofluorescence and those that interact with detection systems. The table below summarizes their sources and impacts.

Table 1: Primary Endogenous Causes of High Background in ISH

| Cause | Source | Impact on ISH |

|---|---|---|

| Autofluorescence | Flavoproteins, reduced pyridine nucleotides (NADH, NADPH), lipofuscin, and tryptophan in central nervous system (CNS) tissues and other sample types [16]. | Emits broad-spectrum light that masks specific fluorescent signals, leading to a low signal-to-noise ratio and unreliable imaging [17] [16]. |

| Endogenous Biotin | Naturally occurring in various tissues (e.g., liver, kidney, brain); a essential coenzyme for carboxylases [6]. | Binds to avidin- or streptavidin-based detection systems, causing non-specific chromogenic or fluorescent staining that is not related to probe hybridization [6]. |

How can I minimize or correct for cellular autofluorescence?

Autofluorescence, characterized by broad excitation and emission spectra, is a significant challenge, especially in metabolically active tissues like the brain [16]. The following strategies can help manage it.

A. Technical and Image Processing Corrections

- Time-Gated Microscopy with Lanthanide Probes: This advanced method uses luminescent lanthanide chelates (e.g., europium complexes), which have long luminescence lifetimes (up to milliseconds). A time-gated camera acquires images after the short-lived autofluorescence (nanosecond range) has completely decayed, resulting in a background-free image [16].

- Digital Image Subtraction: A method using the ratio of autofluorescence between multiple color images to perform pixel-by-pixel subtraction in digital images. This can enhance specific signals, making previously indistinguishable signals clearly visible [17].

B. Optimized Sample Handling and Reagents

- Use of Alternative Labels: Employing digoxigenin-labeled probes instead of biotin can circumvent issues related to endogenous biotin. Digoxigenin is a plant-derived molecule not found in mammalian tissues, ensuring detection is highly specific to the probe [6].

- Pre-hybridization with Random Oligonucleotides: For techniques like in situ Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR), adding random oligonucleotides during pre-hybridization and hybridization steps can reduce non-specific background signals by blocking non-specific binding sites, improving the signal-to-noise ratio by 3 to 90 times [18].

- Optimized Fixation and Permeabilization: Avoid over-fixation, which can increase autofluorescence. Similarly, over-digestion with permeabilization agents like proteinase K can damage tissue morphology and increase background. Perform a titration to find the optimal concentration [2] [6].

Table 2: Methods for Correcting Autofluorescence in ISH

| Method | Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Gated Microscopy | Exploits the long lifetime of lanthanide luminescence to exclude short-lived autofluorescence [16]. | High-precision, background-free imaging of low-abundance targets in highly autofluorescent tissues (e.g., brain and spinal cord). |

| Digital Image Subtraction | Computationally removes autofluorescence based on its spectral characteristics in digital images [17]. | Improving signal visibility in samples with uniform, predictable autofluorescence. |

| Probe Design & Blocking | Uses non-biotin labels and blocking agents to prevent non-specific signal at its source [18] [6]. | All ISH applications, particularly those using signal amplification or working with tissues rich in endogenous biotin. |

Diagram 1: A workflow for troubleshooting and correcting autofluorescence in ISH experiments.

How do I prevent non-specific staining from endogenous biotin?

Endogenous biotin is a common pitfall in ISH and IHC. The key is to block its activity before the detection step.

- Blocking with Avidin/Streptavidin and Biotin: Perform sequential blocking by first applying an avidin or streptavidin solution to bind all available endogenous biotin, followed by a biotin solution to block the remaining binding sites on the avidin/streptavidin. This ensures the detection reagents added later have nothing to bind to except the probe-associated biotin [6].

- Switch to Digoxigenin-Labeled Probes: The most effective strategy is to avoid biotin altogether. Using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes with anti-digoxigenin antibodies for detection completely eliminates the problem of endogenous biotin, as the antibodies are highly specific to the digoxigenin hapten [6].

Diagram 2: Two primary strategies to overcome non-specific staining from endogenous biotin.

What are the best general practices to minimize all types of background?

A robust ISH protocol with careful attention to detail is the first line of defense against high background.

- Optimized Hybridization and Washes: Ensure hybridization temperature and wash stringency are correct. High background can occur if the stringent wash step is inadequate. For example, using a 1X SSC buffer at 75-80°C is often recommended [2]. Parameters like temperature, salt, and detergent concentration should be adjusted to remove non-specific interactions [10] [7].

- Prevent Sample Drying: Ensure that tissue sections do not dry out at any point during the ISH protocol, as drying causes massive non-specific probe binding and high background staining [2] [4]. Use a humidified chamber during all incubation steps.

- Use the Correct Wash Buffers: Always use wash buffers containing detergent (e.g., PBST - PBS with 0.025% Tween 20). Washing with PBS without Tween 20 or distilled water can lead to elevated background [2].

- Validate Reagent Activity and Specificity: Confirm that your enzyme conjugates (e.g., HRP, AP) are active by testing them with their substrate [2]. Also, check probe specificity to ensure it is not binding to repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu elements), which can be blocked with COT-1 DNA during hybridization [2].

- Control Counterstaining: A dark hematoxylin counterstain can mask a positive signal, particularly with DAB or NBT/BCIP chromogens. Use a light counterstain (e.g., 5 seconds to 1 minute) to ensure the ISH signal remains visible [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Troubleshooting Background in ISH

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Background Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin (DIG)-Labeled Probes | A non-radioactive label for nucleic acid probes, detected with anti-DIG antibodies [10] [6]. | Avoids endogenous biotin issues; highly specific for low-background detection [6]. |

| Lanthanide Chelates (e.g., Europium) | Luminescent labels for probes used with time-gated microscopy [16]. | Enables background-free imaging by bypassing short-lived autofluorescence [16]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme for digesting proteins and permeabilizing the sample for probe access [10] [6]. | Concentration must be optimized; over-digestion damages tissue, under-digestion reduces signal [2] [6]. |

| COT-1 DNA | Unlabeled DNA rich in repetitive sequences [2]. | Added during hybridization to block non-specific binding of probes to repetitive genomic sequences, reducing background [2]. |

| Avidin/Biotin Blocking Solutions | Sequential solutions of avidin (or streptavidin) and free biotin [6]. | Essential for blocking endogenous biotin when using biotinylated probes. |

| Random Oligonucleotides | Short, non-specific DNA sequences [18]. | Used in HCR and other ISH methods to block non-specific binding sites during pre-hybridization, drastically reducing background [18]. |

| Charged Slides (e.g., Superfrost Plus) | Microscope slides with a charged surface to enhance tissue adhesion [19]. | Prevents tissue loss during stringent washes and avoids pooling of reagents under lifting sections, which causes uneven staining [4]. |

Best Practices in ISH: A Methodological Framework for Clean Results

Optimal Sample Fixation and Preparation Protocols for DNA and RNA Preservation

FAQs on Fixation and Preservation

1. What is the most critical factor for successful DNA/RNA preservation in tissue samples? Optimal and consistent fixation is paramount. Both under-fixation and over-fixation can compromise nucleic acid integrity and accessibility, leading to high background or weak signals in subsequent experiments like ISH. Use a known, standardized fixative (e.g., 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin) and adhere strictly to recommended fixation times and temperatures to ensure proper tissue preservation without excessive cross-linking [14] [4].

2. How can I prevent RNA degradation during sample collection? RNA is highly susceptible to degradation by ubiquitous RNases. To prevent this:

- Stabilize Immediately: Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen or immerse them in RNA stabilization reagents (e.g., RNAlater) immediately after collection [20] [21].

- Work Quickly: Minimize the time between sample collection and stabilization or fixation [4] [20].

- Use an RNase-free environment: Designate a clean workspace, use RNase-free consumables, and wear gloves to prevent introduction of external RNases [20] [21].

3. My ISH experiments show high background staining. What are the most common causes? High background in ISH is frequently caused by:

- Insufficient Stringency Washes: Inadequate washing fails to remove non-specifically bound probes [2] [14] [22].

- Probe-Related Issues: Probes with repetitive sequences can cause background; this can be blocked by adding COT-1 DNA during hybridization [2] [22].

- Over-digestion during Pretreatment: Excessive protease or pepsin treatment can damage tissue and increase non-specific binding [2] [22].

- Sample Drying: Allowing slides to dry at any point during the hybridization or detection process can cause heavy, non-specific background staining [2] [4].

4. Are some tissues more challenging for nucleic acid preservation and isolation? Yes, tissues high in endogenous nucleases (e.g., pancreas) or lipid content (e.g., brain, adipose tissue) are particularly challenging. For these tissues, more rigorous isolation methods, such as phenol-based extraction (e.g., TRIzol), are recommended over standard column-based kits to ensure high-quality yields [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: High Background in In Situ Hybridization

High background signal can obscure results and lead to erroneous conclusions. The following table outlines common causes and their specific solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation & Fixation | Under-fixation [14] | Use freshly prepared fixative and adhere strictly to recommended fixation times [14]. |

| Over-fixation [14] | Avoid excessive cross-linking by standardizing fixation conditions; may require extended retrieval for FFPE [14] [23]. | |

| Pretreatment | Insufficient pre-treatment [14] | Ensure adequate heat-induced epitope retrieval and enzymatic digestion to unmask target sequences [2] [14]. |

| Over-digestion [2] [22] | Optimize protease/pepsin digestion time and temperature (e.g., 3-10 min at 37°C for many tissues) [2]. | |

| Hybridization & Probes | Probes with repetitive sequences [2] | Add blocking DNA (e.g., COT-1 DNA) to the hybridization mix to prevent non-specific binding [2]. |

| Incorrect denaturation [14] | Ensure denaturation is performed at 95 ± 5°C for 5-10 minutes; avoid temperatures that are too high or times that are too long [2] [14]. | |

| Washing | Low stringency wash [2] [14] | Perform stringent washes with appropriate buffer (e.g., SSC) at the correct temperature (75-80°C) and duration [2] [14]. |

| Incorrect wash buffer [2] | Always use buffers containing detergent (e.g., PBST) as specified; washing with water or PBS alone can cause high background [2]. | |

| Detection & Staining | Reaction over-development [2] | Monitor the development of the chromogenic signal under a microscope and stop the reaction by rinsing in water as soon as background appears [2]. |

| Excessive counterstaining [2] | Use a light counterstain (e.g., Mayer’s hematoxylin for 5-60 seconds) to avoid masking the specific signal [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Preservation

Protocol 1: Standardized Fixation for Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissues

This protocol is critical for preserving morphology and nucleic acids for techniques like ISH and FISH.

Key Materials:

- Fresh 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) [23]

- Positively Charged Microscope Slides (e.g., Superfrost Plus) [4] [23]

- Tissue Processing and Embedding System

Methodology:

- Immersion Fixation: Immediately upon dissection, immerse tissue in a sufficient volume of 10% NBF (typically 10:1 fixative-to-tissue ratio) [2] [23].

- Fixation Time: Fix at room temperature for 24-48 hours. Prolonged fixation can lead to excessive cross-linking, while short fixation risks under-preservation [14] [4].

- Processing: After fixation, dehydrate the tissue through a graded series of alcohols, clear with xylene, and infiltrate with paraffin using a standard histological processor.

- Embedding and Sectioning: Embed tissue in paraffin blocks and section at a thickness of 3-4 μm [14]. Float sections on a warm water bath and mount on positively charged slides.

- Slide Storage: Dry slides thoroughly, preferably overnight, at 37°C or on a slide warmer. Store at room temperature or 4°C until use.

Protocol 2: RNA Preservation from Challenging Tissues for Downstream Analysis

This protocol is optimized for tissues high in RNases or lipids.

Key Materials:

- TRIzol Reagent [24] [21] or a dedicated kit like the PureLink RNA Mini Kit [21]

- Liquid Nitrogen

- RNaseZap Decontamination Solution [21]

- RNase-free tubes and tips

Methodology:

- Stabilization:

- Option A (Flash-freezing): For solid tissues, rapidly dissect into small pieces (<0.5 cm) and immediately submerge in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C until processing [20] [21].

- Option B (Stabilization Solution): For easier handling, place small tissue pieces directly into 5-10 volumes of RNAlater, store overnight at 4°C, then remove and store at -80°C [24] [21].

- Homogenization: Under a designated RNase-free fume hood, homogenize the frozen or stabilized tissue in TRIzol reagent using a thoroughly cleaned rotor-stator homogenizer. Ensure all equipment is treated with RNaseZap [21].

- RNA Isolation: Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the TRIzol or column-based isolation method. This typically involves phase separation with chloroform, RNA precipitation with isopropanol, and washing with ethanol [24] [21].

- DNase Treatment: To remove genomic DNA contamination, perform an on-column DNase digestion step if using a kit [21].

- RNA Storage: Elute or resuspend the purified RNA in RNase-free water or TE buffer. Aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw cycles and store at -80°C for long-term preservation [20] [21].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and procedures in the sample preparation workflow, highlighting how choices impact downstream outcomes like background signal.

Diagram: Impact of Sample Preparation on ISH/FISH Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents referenced in the protocols and troubleshooting guides.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) | Standard fixative for FFPE tissues; preserves morphology and nucleic acids. | Always use freshly prepared; standardize fixation time to avoid under/over-fixation [14] [23]. |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Stabilizes and protects cellular RNA in unfrozen tissues prior to homogenization. | Tissue must be dissected into small pieces (<0.5 cm) for rapid penetration [24] [21]. |

| TRIzol Reagent | Monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for effective lysis and isolation of total RNA. | Ideal for challenging tissues (high in fat, RNases); requires careful handling [24] [21]. |

| Positively Charged Slides (e.g., Superfrost Plus) | Provides superior adhesion for tissue sections, preventing tissue loss during processing. | Critical for multi-step ISH protocols to avoid losing samples [4] [23]. |

| COT-1 DNA | Used to block non-specific hybridization of repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu, LINE) in probes. | Reduces high background staining in ISH/FISH [2]. |

| Protease / Pepsin | Enzyme for digesting proteins surrounding target nucleic acids, improving probe accessibility. | Concentration and time must be optimized; over-digestion damages tissue [2] [22]. |

| Stringent Wash Buffer (e.g., SSC with Tween 20) | Removes unbound and weakly bound probes after hybridization to reduce background. | Temperature (75-80°C), salt concentration, and duration are critical for stringency [2] [14]. |

FAQ: DNA vs. RNA Probes - Core Differences and Selection Criteria

What are the fundamental differences between DNA and RNA probes?

DNA and RNA probes, while both used to detect nucleic acid sequences, have distinct biochemical properties and are synthesized differently. DNA probes are typically labeled fragments of DNA, either single or double-stranded, that are complementary to a specific target sequence. RNA probes are stretches of single-stranded RNA used for the same purpose, but they are almost exclusively generated through a method called in vitro transcription [25].

The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

| Feature | DNA Probes | RNA Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Deoxyribonucleic Acid | Ribonucleic Acid |

| Common Synthesis Methods | Nick Translation, PCR, Random Priming [25] | In vitro Transcription [25] |

| Thermal Stability | High | Generally lower; more susceptible to degradation [25] |

| Hybridization Efficiency | Good | Superior; RNA-DNA hybrids are more stable than DNA-DNA hybrids [26] |

| Typical Use Cases | Detecting DNA targets (e.g., gene loci on chromosomes), FISH [2] | Detecting RNA targets, sensitive applications requiring strong signal [25] [26] |

How do I choose between a DNA probe and an RNA probe for my experiment?

Your choice should be guided by your experimental goal, the target molecule, and the required sensitivity.

- For Detecting DNA Targets (e.g., gene loci, chromosomal rearrangements): DNA probes are often the preferred and more robust choice [2].

- For Detecting RNA Targets (e.g., mRNA localization, gene expression): RNA probes are generally superior due to their higher hybridization efficiency, which can lead to a stronger signal [2]. They are particularly useful for sensitive detection of low-abundance transcripts.

- For Enrichment in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Recent studies show a performance trade-off. RNA probes demonstrate superior enrichment efficiency, yielding higher mapping rates and sequencing depth. However, DNA probes are more effective at reducing artifacts caused by nuclear mitochondrial DNA segments (NUMTs), leading to fewer false positives in mutation detection [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving High Background in ISH

High background fluorescence or staining is a common challenge that can obscure results and lead to erroneous conclusions. The following FAQs address its primary causes and solutions.

Why is my background staining so high, and how can I reduce it?

High background can stem from multiple aspects of your ISH procedure. The diagram below outlines the primary troubleshooting workflow and the key parameters to check.

Probe-Related Causes and Fixes

- Cause: Probes with Repetitive Sequences. If your probe contains a lot of repetitive sequences like Alu or LINE elements, it can bind non-specifically across the genome, elevating background staining [2].

- Fix: Add unlabeled blocking DNA, such as COT-1 DNA, during the hybridization step to competitively inhibit probe binding to these repetitive regions [2].

- Cause: Suboptimal Probe Concentration or Denaturation.

- Fix: Precisely follow the manufacturer's protocol for probe volume. Verify and optimize the denaturation temperature and time for your specific sample type (e.g., FFPE tissue requires careful optimization) [14].

Washing and Stringency Causes and Fixes

- Cause: Inadequate Stringent Washes. The stringent wash is critical for removing probes that are weakly or non-specifically bound to imperfectly matched sequences [2] [22].

- Fix: Ensure the stringent wash is performed at the correct temperature (commonly 75–80°C for CISH) and with the proper salt concentration (e.g., SSC buffer) [2]. Increase the stringency incrementally if background persists, but avoid conditions so harsh that they remove your specific signal.

- Cause: Poor Quality Wash Buffers. Degraded or contaminated buffers can fail to remove unbound probes effectively [14].

- Fix: Always use freshly prepared wash buffers [14].

Sample Preparation and Detection Causes and Fixes

- Cause: Improper Fixation. Both under-fixation and over-fixation can lead to high background. Under-fixation fails to preserve cellular structure, leading to non-specific probe binding. Over-fixation causes excessive cross-linking, which can trap probes and mask targets, also increasing background [14].

- Fix: Adhere strictly to recommended fixation times and use freshly prepared fixative solutions [14].

- Cause: Dark Counterstaining. A very dark counterstain, such as over-staining with hematoxylin, can mask the specific signal and make background particulate matter more prominent [2].

- Fix: Use a light counterstain (e.g., 5 seconds to 1 minute in Mayer's hematoxylin) to enhance contrast without obscuring your result [2].

- Cause: Worn Microscope Filters. Damaged or degraded optical filters on your fluorescence microscope can produce a mottled appearance and weaken the specific signal, making background noise more apparent [14].

- Fix: Inspect filters for damage and replace them according to the manufacturer's guidelines, typically every 2-4 years [14].

My positive control works, but my experimental sample has a weak or absent signal. What should I do?

A weak or absent signal despite a working control points to issues with the target accessibility or the probe hybridization in your specific sample.

- Cause: Inadequate Digestion / Permeabilization. Proteins surrounding the target nucleic acid can prevent the probe from reaching its target [22].

- Fix: Optimize the enzyme (e.g., pepsin, proteinase K) digestion time and temperature for your tissue type. Between 3-10 minutes at 37°C is a common starting point, but this must be optimized, as over-digestion can damage morphology and under-digestion will block probe access [2] [27].

- Cause: Target Degradation. If the time between obtaining the tissue and fixing it is too long, the RNA or DNA target can degrade, leading to a false negative [2].

- Fix: Minimize the time from sample collection to fixation. Ensure the tissue specimen is an appropriate size for the volume of fixative to ensure rapid and complete penetration [2].

- Cause: Suboptimal Hybridization Conditions. The hybridization temperature, time, or buffer may not be correct for your probe-sample combination [22].

- Fix: Verify that the hybridization temperature is optimized for your probe's sequence and sample type. Ensure the hybridization is performed in a humidified chamber to prevent the slide from drying out, which can cause high, non-specific background [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: RNA-ISH with High-Sensitivity Probes

The following protocol provides a generalized workflow for detecting RNA targets using advanced RNA probes, such as those utilizing signal amplification technologies [25].

Principle: Labeled RNA probes are hybridized to specific RNA targets in fixed cells or tissues. The probes are designed with non-hybridizing, enzyme-labeled regions (e.g., biotin or digoxigenin). After hybridization, chromogenic development is used to visualize the precise spatial localization of the target RNA [25].

Solutions and Reagents

| Stage | Essential Reagents |

|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Coating solution, fresh fixative (e.g., formaldehyde, paraformaldehyde), wash buffers [22] [14]. |

| Pretreatment | Protease (e.g., pepsin, proteinase K), hydrochloric acid, blocking buffer (e.g., to block endogenous alkaline phosphatase or biotin) [2] [22]. |

| Hybridization | Target-specific RNA probes (e.g., AMPIVIEW), hybridization buffer, coverslips [25] [22]. |

| Post-Hybridization Washes | Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer, PBST (PBS with Tween 20) [2]. |

| Detection | Enzyme conjugate (e.g., HRP- or AP- conjugated anti-biotin or anti-digoxigenin), chromogenic substrate (e.g., DAB for HRP, NBT/BCIP for AP), Mayer's Hematoxylin for counterstaining, aqueous mounting medium [2]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation and Fixation:

- Prepare tissue sections (3-4μm thick for FFPE) or cells on positively charged slides to ensure adhesion [14].

- Fix samples promptly with an appropriate fixative. For many RNA targets, fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15-30 minutes is effective. Critical: Avoid over-fixation, as it can mask the target sequence [14].

Pretreatment and Permeabilization:

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate FFPE sections if needed.

- Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) by heating in an appropriate buffer (e.g., citrate-based) at 98°C for 15 minutes [2].

- Treat with protease (e.g., pepsin at 37°C for 3-10 minutes) to digest proteins surrounding the RNA and increase probe accessibility. Tip: Optimize this time for your specific tissue; over-digestion degrades morphology, under-digestion reduces signal [2].

- Apply a blocking agent to inhibit non-specific binding from endogenous enzymes or proteins [22].

Hybridization:

- Prepare the probe by diluting it in the appropriate hybridization buffer. For some probes, denaturation at 85°C for 5 minutes is required before use [2].

- Apply the diluted probe to the sample and cover with a coverslip. Ensure no air bubbles are trapped.

- Incubate the slides in a humidified hybridization chamber at 37°C for the recommended time, typically 16 hours (overnight) [2].

Post-Hybridization Washes and Stringency Control:

- Remove coverslips by soaking slides in a wash buffer (e.g., PBST).

- Perform a stringent wash to remove weakly bound probes. A common method is to immerse slides in SSC buffer (e.g., 1X SSC) at 75-80°C for 5 minutes [2].

- Rinse slides with TBST or PBST. Critical: Do not use water or PBS without detergent at this stage, as it can increase background [2].

Signal Detection and Chromogenic Development:

- Incubate slides with the enzyme conjugate (e.g., HRP-anti-biotin) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with PBS.

- Apply the chromogenic substrate (e.g., DAB for HRP) and monitor the development of the colored precipitate under a microscope. Stop the reaction by rinsing with distilled water the moment background staining begins to appear [2].

- Apply a light counterstain (e.g., Mayer's hematoxylin for 5-60 seconds) to visualize tissue architecture [2].

- Mount the slides with an aqueous mounting medium and proceed to imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nick Translation DNA Labeling Kit [25] | Enzymatic incorporation of labeled nucleotides (Fluorophore, Biotin, Digoxigenin) into DNA probes. | Generating labeled DNA probes for use in FISH, CISH, and Southern blotting. |

| Custom RNA Probes (e.g., AMPIVIEW) [25] | Provide high-sensitivity, target-specific probes with built-in signal amplification technology. | Sensitive detection of RNA or DNA targets in cells and tissue while preserving morphology. |

| Cytocell LPS 100 Tissue Pretreatment Kit [14] | Standardized heat and enzyme treatment for FFPE tissue sections. | Optimizing sample pretreatment to maximize target accessibility and minimize background in FISH. |

| CO-T-1 DNA [2] | Unlabeled DNA that blocks repetitive genomic sequences. | Reducing non-specific background staining caused by probe binding to repetitive elements. |

| Mayer's Hematoxylin [2] | A light, nuclear counterstain. | Providing contrast by staining cell nuclei without masking the specific chromogenic signal. |

| DAB (3,3'-Diaminobenzidine) [2] | Chromogenic substrate for Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). | Producing an insoluble brown precipitate at the site of probe hybridization. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting High Background in ISH

Why is my ISH background staining too high, and how can I reduce it?

High background is a common challenge that can obscure your specific signal. The causes and solutions are multifaceted:

- Inadequate Stringent Washing: Insufficient washing after hybridization is a primary cause. For optimal results, perform a post-hybridization wash with SSC buffer (e.g., 1X SSC) at a temperature between 75–80°C for 5 minutes [2].

- Probe-Related Issues: Probes containing repetitive sequences (like Alu or LINE elements) can bind non-specifically. This can be mitigated by adding blocking agents such as COT-1 DNA to your hybridization mixture [2].

- Incorrect Wash Buffer: Using PBS or distilled water without detergent during washing steps can elevate background. Always use the recommended buffers containing a mild detergent like Tween 20 (e.g., PBST) to minimize non-specific interactions [8] [2].

- Over-development with Chromogen: Allowing the chromogen reaction (e.g., DAB) to proceed for too long leads to diffuse background stain. Monitor the reaction under a microscope and stop it by rinsing with distilled water as soon as specific signal appears and before background develops [8] [2].

What causes weak or absent ISH staining?

A weak or absent signal can result from problems at various stages of your protocol:

- Suboptimal Enzyme Pretreatment (Digestion): Enzyme digestion is critical for unmasking targets. Both over-digestion and under-digestion with enzymes like pepsin can weaken or eliminate the signal. The optimal digestion time (e.g., 3–10 minutes at 37°C for pepsin) must be determined for your specific tissue and fixation conditions [2].

- Ineffective Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER): HIER is often necessary to expose nucleic acid targets. Using the wrong buffer or insufficient heating can cause failure. Ensure the retrieval buffer reaches and maintains the correct temperature (e.g., 98°C) for the full duration [2] [28].

- Poor Fixation or Tissue Handling: A long delay between tissue collection and fixation, or using an inadequate volume of fixative, degrades the target and leads to poor results. Ensure immediate and standardized fixation protocols are followed [4].

- Inactive Reagents: Always confirm that your enzyme conjugates (e.g., HRP) are active by testing them with their substrate in a small tube. A color change should occur within a few minutes [2].

Quantitative Data for Pre-treatment Optimization

Table 1: Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) Buffer Comparison

| Buffer Composition | Typical pH Range | Common Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Citrate [29] [28] | 6.0 | A very popular, general-purpose buffer. Suitable for a wide range of antigens. |

| Tris-EDTA [29] [28] | 9.0 | Often provides excellent antigen recovery, particularly for more challenging targets. |

| EDTA [29] [28] | 8.0 | Known for strong retrieval efficacy, but may cause more tissue damage compared to citrate. |

Table 2: Enzyme Digestion Conditions for Antigen Retrieval

| Enzyme | Typical Concentration | Incubation Conditions | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pepsin [2] | Not Specified | 3-10 minutes at 37°C | Conditions are tissue-dependent. Over-digestion eliminates signal; under-digestion decreases signal. |

| General Proteases | Varies | Varies by specific enzyme | Can risk tissue damage or non-specific staining; concentration and time require empirical optimization [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Pre-treatment Methods

Protocol 1: Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) Using a Pressure Cooker

This method is efficient and widely used for consistent results [28].

Materials:

- Domestic stainless steel pressure cooker and hot plate

- Antigen retrieval buffer (e.g., Citrate pH 6.0, Tris-EDTA pH 9.0)

- Metal slide rack

Method:

- Add antigen retrieval buffer to the pressure cooker and begin heating on a full-power hot plate.

- While the buffer is heating, deparaffinize and rehydrate your tissue sections using standard histological methods.

- Once the buffer is boiling, transfer the slides from tap water into the pressure cooker.

- Secure the lid as per the manufacturer's instructions. Once full pressure is reached, start the timer and process the slides for 3 minutes [28].

- After 3 minutes, turn off the hotplate. Place the pressure cooker in a sink, activate the pressure release valve, and run cold water over the cooker to depressurize and cool it.

- Open the lid and run cold water into the cooker for 10 minutes to cool the slides completely.

- Proceed with your ISH or IHC staining protocol.

Protocol 2: Enzymatic Antigen Retrieval

Enzymatic methods can be effective but require careful optimization to avoid tissue damage [2] [28].

Materials:

- Enzyme solution (e.g., Pepsin)

- Humidified incubation chamber at 37°C

Method:

- Following deparaffinization and rehydration, rinse the slides with the recommended buffer.

- Pipette the pre-warmed enzyme solution onto the tissue section, ensuring complete coverage.

- Incubate the slides in a humidified chamber at 37°C. The incubation time must be optimized for your system. A starting range of 3-10 minutes is recommended for pepsin [2].

- After incubation, thoroughly rinse the slides with distilled water or an appropriate buffer to stop the enzymatic reaction.

- Continue with the subsequent steps of your staining protocol.

Pre-treatment Optimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical decision-making process for troubleshooting and optimizing pre-treatment methods to reduce high background and improve signal in ISH.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Pre-treatment and Troubleshooting

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Citrate Buffer (pH 6.0) [29] [28] | A common buffer for HIER to break formaldehyde cross-links and unmask epitopes. | A versatile, first-choice buffer for many targets. |

| Tris-EDTA Buffer (pH 9.0) [29] [28] | An alternative alkaline pH retrieval buffer for more challenging targets. | Often effective when citrate fails. |

| Pepsin [2] | A protease enzyme for enzymatic retrieval, digesting proteins masking the target. | Requires careful optimization of time and concentration to avoid tissue damage. |

| SSC Buffer [2] | Saline-sodium citrate buffer used for post-hybridization stringent washes. | Critical for removing non-specifically bound probe; temperature-sensitive. |

| COT-1 DNA [2] | Used to block hybridization to repetitive DNA sequences in the genome. | Reduces non-specific background when using probes containing repetitive elements. |

| Tween 20 [8] [2] | A mild detergent added to wash buffers (e.g., PBST). | Reduces hydrophobic interactions and non-specific binding, lowering background. |

| HRP Conjugate & DAB [8] [2] | Enzyme conjugate and chromogen system for colorimetric detection. | Monitor development microscopically to prevent over-development and high background. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents essential for controlling hybridization precision and managing background noise.

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Controlling Precision & Background |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Agents | Casein, BSA, Denatured Salmon Sperm DNA [30] | Reduces non-specific attachment of the probe to the membrane or tissue, lowering background signal. |

| Helix-Destabilizing Reagents | Formamide [31] | Lowers the effective melting temperature (Tm), allowing for stringent hybridization at lower temperatures that preserve tissue morphology. |

| Stringent Wash Buffers | Saline Sodium Citrate (SSC) [2] [30] | The salt concentration regulates stringency; low salt concentrations increase stringency to wash away imperfectly matched hybrids. |

| Proteases | Pepsin [2] | Digests proteins surrounding the target nucleic acid, increasing probe accessibility and signal strength. |

| Detergents | Tween 20, SDS [2] [30] | Added to wash buffers (e.g., PBST) to reduce electrostatic interactions and lower background staining. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting High Background

1. What are the primary factors that cause high background in my hybridization experiment?

High background is most frequently caused by insufficient stringency during the washing steps or non-specific probe interactions [2] [22] [27]. This can be broken down into several specific causes:

- Inadequate Stringent Washes: The temperature of your stringent wash may be too low, or the salt concentration may be too high, preventing the removal of partially matched probes [2].

- Probe Design: Probes that contain repetitive sequences (like Alu or LINE elements) can bind non-specifically throughout the genome, elevating background [2].

- Sub-optimal Wash Buffers: Using the wrong wash solution, such as distilled water or PBS without a detergent like Tween 20, can lead to elevated background [2].

- Over-digestion during Pretreatment: Excessive protease treatment can degrade tissue morphology and increase non-specific probe binding, contributing to background [22].

2. How do I precisely control stringency to eliminate background without losing my specific signal?

Stringency is controlled by both temperature and salt concentration during hybridization and post-hybridization washes. The relationship is inverse for these two parameters [30]:

- High Stringency: High Temperature and Low Salt concentration. This favors the formation of only perfectly matched hybrids.

- Low Stringency: Low Temperature and High Salt concentration. This allows imperfectly matched hybrids to form.

For a typical stringent wash using SSC buffer, a temperature of 75-80°C is recommended [2]. If you are washing multiple slides, increase the temperature by approximately 1°C per slide, but do not exceed 80°C [2].

3. My specific signal is weak, but the background is high. What steps should I take?

This combination of problems suggests that while your probe is binding, it is doing so non-specifically. Your troubleshooting should focus on improving the specificity of binding.

- Verify Probe and Conjugate Match: Ensure that biotin-labeled probes are used with an anti-biotin conjugate and digoxigenin-labeled probes with an anti-digoxigenin conjugate [2].

- Check Enzyme Substrate Compatibility: Confirm that HRP is used with DAB or AEC, and alkaline phosphatase is used with NBT/BCIP or Fast Red [2].

- Optimize Pretreatment: Both over-digestion and under-digestion with protease can decrease or eliminate the specific signal [2]. A typical range is 3-10 minutes at 37°C, but this must be optimized for your specific tissue type [2].

- Add Blockers for Repetitive Sequences: If your probe contains repetitive sequences, add unlabeled COT-1 DNA to the hybridization mixture to block non-specific binding sites [2].

4. How does the chemical composition of the hybridization buffer influence precision?

The hybridization buffer is not merely a solvent; its components are critical for controlling the kinetics and specificity of the reaction.

- Formamide: This reagent destabilizes DNA duplexes, effectively lowering the melting temperature. This allows you to perform hybridization at a lower temperature (e.g., 37°C), which preserves tissue morphology, while still maintaining high specificity [31].

- Dextran Sulfate: This anionic polymer acts to exclude volume, which locally concentrates the probe and enhances the rate of hybridization [31].

- Monovalent Cations: Provided by salts like NaCl in SSC buffer, cations shield the natural negative repulsion between the phosphate backbones of the probe and target. High salt concentration produces low stringency conditions, while low salt concentration increases stringency [31].

Quantitative Data for Experimental Control

The tables below summarize key quantitative parameters for critical steps in the hybridization workflow.

Table 1: Temperature and Time Parameters for Key Steps [2] [22]

| Experimental Step | Temperature Range | Time Range | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval | 98°C | 15 minutes | Time starts when buffer reaches target temperature. |

| Protease Digestion (Pepsin) | 37°C | 3 - 10 minutes | Must be optimized for specific tissue type to avoid over- or under-digestion. |

| Denaturation | 95 ± 5°C | 5 - 10 minutes | Slides should be cover-slipped and performed in a moist environment. |

| Hybridization | 37°C | 16 hours (overnight) | Optimum for specificity; conducted in a humidified chamber. |

| Stringent Wash | 75 - 80°C | 5 minutes | Using SSC buffer; critical for reducing background. |

| Enzyme Conjugate Incubation | 37°C | 30 minutes | Follow with multiple rinses in PBS buffer. |

Table 2: Parameters for Managing Signal Detection [2]

| Parameter | Recommended Specification | Impact on Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Incubation (DAB) | 5 - 15 minutes at 37°C | Monitor under microscope at 2-minute intervals; stop reaction (rinse in water) the moment background appears. |

| Counterstaining (Hematoxylin) | 5 seconds - 1 minute | A dark counterstain can mask a positive signal; Mayer’s hematoxylin is recommended. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Stringent Wash for Background Reduction

This protocol is critical for removing partially matched probes that cause high background.

Methodology:

- Post-Hybridization Rinse: After hybridization, briefly rinse the slides at room temperature with SSC buffer to remove the bulk of the hybridization solution [2].

- High-Temperature Stringent Wash: Immerse the slides in a fresh container of pre-warmed SSC buffer. Place the container in a water bath or oven set to 75°C for 5 minutes [2].

- Adjust for Multiple Slides: If washing more than two slides simultaneously, increase the temperature by 1°C per slide to compensate for heat dispersion, but do not exceed 80°C [2].

- Final Rinse: After the stringent wash, rinse the slides with a buffer like TBST or PBST. Avoid using water or plain PBS at this stage, as this can contribute to background [2].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting high background in hybridization experiments.

Diagram 2: Relationship between stringency parameters and experimental outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common mistake when setting up a detection system? The most frequent error is a mismatch between the probe label, the conjugate, and the enzyme substrate. For example, using a biotin-labeled probe requires an anti-biotin conjugate, and an HRP-conjugated antibody must be used with DAB or AEC, not with an AP substrate like NBT/BCIP [2].

My negative control shows high background. What does this indicate? High background in a negative control (where the primary antibody or probe is omitted) strongly suggests that the secondary antibody or the detection system itself is binding non-specifically. This can be due to endogenous enzymes, endogenous biotin, or cross-reactivity with tissue components [32] [33] [34].

How can I reduce high background that appears evenly across my tissue section? Start by optimizing your washing steps, particularly the stringency wash. Ensure you are using the correct buffer (e.g., SSC) at the proper temperature (typically 75-80°C) [2]. Also, titrate your primary antibody and probe, as concentrations that are too high are a common cause of uniform background [32] [34].

The background is only high at the edges of the section. What is the cause? This pattern typically indicates that the tissue section dried out at some point during the procedure, which concentrates reagents and leads to edge artifacts. Always ensure slides remain hydrated in a humidified chamber [35] [4].

My chromogen signal is weak, but the background is low. What should I check? Verify the activity of your enzyme conjugate by testing it with its substrate alone; a color change should occur within minutes [2]. Also, check that your detection method is sensitive enough for your target abundance and consider using signal amplification methods like tyramide signal amplification (TSA) for low-abundance targets [2] [36].

Matching Conjugates, Enzymes, and Substrates

A properly matched detection system is fundamental to a successful experiment. The table below outlines the correct combinations to generate a specific signal while minimizing background.

| Probe Label | Conjugate (Binder) | Enzyme | Compatible Substrates | Precipitate Color |