Validating Mutant Alleles: Integrating Sanger Sequencing and NGS for Robust Discovery and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating mutant alleles discovered through Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS).

Validating Mutant Alleles: Integrating Sanger Sequencing and NGS for Robust Discovery and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating mutant alleles discovered through Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). It covers the foundational principles of both Sanger and NGS technologies, detailing their respective strengths in discovery and confirmation. The content explores established and emerging methodological workflows for validation, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and delivers a critical comparative analysis of accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness. By synthesizing current best practices and future trends, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design rigorous, reliable validation strategies that enhance data integrity in both research and clinical diagnostics.

The Pillars of Precision: Understanding Sanger and NGS Technologies for Mutant Allele Analysis

FAQ: What are the fundamental differences in chemistry between Sanger (Chain Termination) and Next-Generation Sequencing (Massively Parallel Sequencing)?

The core difference lies in the scale and approach. Sanger sequencing is based on the chain termination method using dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs), performed on a single DNA fragment per reaction. In contrast, Massively Parallel Sequencing (MGS), or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), uses technologies like sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) to simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments immobilized on a flow cell [1] [2] [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Sequencing Chemistries

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing (Chain Termination) | Massively Parallel Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Chemistry Principle | Dideoxy chain termination with capillary electrophoresis [3] | Sequencing-by-synthesis, pyrosequencing, or ligation [1] [2] [3] |

| Throughput | Low (single reaction per capillary) [1] | Ultra-high (millions to billions of parallel reactions) [1] [2] |

| Read Length | Long (up to ~1000 bases) | Short to moderate (50-400 bases, with some technologies longer) [2] [3] |

| Typical Application | Targeted sequencing of single genes or few amplicons; gold standard for validation [4] [5] | Whole genomes, exomes, transcriptomes, targeted panels; discovery applications [1] |

| Data Output | Kilobases per run | Gigabases to Terabases per run [1] |

| Key Technical Step | In vitro chain termination and electrophoretic separation | In situ clonal amplification (e.g., bridge PCR, emulsion PCR) and parallelized sequencing [2] [3] |

Validation of Mutant Alleles: Sanger vs. NGS

FAQ: Is Sanger sequencing still necessary for validating mutant alleles identified by NGS?

For high-quality NGS variant calls, recent large-scale studies suggest that Sanger confirmation may be redundant. A 2021 study validating 1109 variants from 825 clinical exomes reported a 100% concordance for high-quality single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) detected by NGS, concluding that Sanger sequencing is more useful as a general quality control than as a mandatory verification step for such variants [4]. This demonstrates the high analytical sensitivity and specificity of modern NGS workflows.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of NGS for Mutant Allele Detection

| Study Focus | Sample & Variant Size | Key Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Exome Validation [4] | 1109 variants in 825 exomes | Concordance with Sanger | 100% for high-quality SNVs and indels |

| Detection of Simple & Complex Mutations [5] | 119 changes in 20 samples | Analytical Sensitivity & Specificity | 100% concordance with known Sanger data |

| Somatic Mutation Validation [6] | 27 selected variations in cervical cancer | Sanger Validation Rate | ~60% (highlighting need for careful NGS parameter setting) |

NGS Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ: My NGS run yielded low or no data. What are the common causes?

Failures in NGS often originate from the library preparation stage. Below is a guide to diagnosing common issues [7].

Problem Category 1: Low Library Yield

- Failure Signals: Low final concentration, faint or broad peaks on electropherogram, high adapter-dimer peaks.

- Root Causes:

- Poor Input Quality: Degraded DNA/RNA or contaminants (phenol, salts) inhibit enzymes [7].

- Fragmentation Issues: Over- or under-shearing produces fragments outside the optimal size range [7].

- Adapter Ligation Inefficiency: Caused by suboptimal adapter-to-insert molar ratio, inactive ligase, or poor reaction conditions [7].

- Corrective Actions:

- Re-purify input DNA/RNA and use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of UV absorbance alone.

- Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, enzyme concentration).

- Titrate adapter:insert ratio and ensure fresh ligation reagents are used [7].

Problem Category 2: High Duplicate Read Rate & Low Complexity

- Failure Signals: Abnormally high proportion of PCR duplicates, flat coverage.

- Root Causes:

- Over-amplification: Too many PCR cycles during library amplification [7].

- Insufficient Input DNA: Starting with too little DNA reduces library complexity from the outset.

- Corrective Actions:

- Reduce the number of amplification cycles.

- Increase the amount of input DNA within the recommended range for your protocol.

Problem Category 3: Instrument-Specific Errors

- Failure Signals: Chip initialization failures, connectivity errors, low bead loading (for semiconductor sequencing).

- Root Causes & Actions:

- Chip Check Failures: Ensure the chip is properly seated and the clamp is closed. If the error persists, replace the chip [8].

- Low Bead Count: Confirm that control beads were added during template preparation. This can also indicate problems with library or template quality [8].

- Server Connectivity Issues: Restart the instrument and server. Check ethernet connections [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Validating NGS-Indentified Mutant Alleles by Sanger Sequencing

This protocol is used to confirm putative variants from NGS analysis, a critical step in research and diagnostic settings [4] [6].

Step 1: Variant Review and Selection

- Visualize putative variants from NGS data using a genome browser (e.g., Integrative Genomics Viewer) [4].

- Prioritize variants based on quality metrics (e.g., read depth ≥20x, variant fraction ≥20%) and potential biological significance [4].

Step 2: PCR Primer Design

- Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST.

- Design primers to flank the variation, generating an amplicon of 250-400 bp.

- Check primers for specificity and to ensure they do not bind to common SNPs or repetitive regions [4] [6].

Step 3: PCR Amplification

- Set up 50 µL PCR reactions using 50 ng of genomic DNA, reaction buffer, dNTPs, primers, and a high-fidelity DNA polymerase.

- Use touch-down or standard PCR cycling conditions with an annealing temperature optimized for the primers [5] [6].

Step 4: Amplicon Purification

- Verify successful amplification via agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Purify PCR products using a commercial purification kit (e.g., QIAquick) to remove primers, dNTPs, and enzymes [6].

Step 5: Sanger Sequencing and Analysis

- Quantify the purified PCR product.

- Perform Sanger sequencing reactions using the same primers as for PCR.

- Analyze the resulting chromatograms using sequence analysis software to confirm or refute the presence of the NGS-identified variant [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for NGS Validation Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of target regions for both NGS library prep and Sanger validation PCR. | Reduces PCR-introduced errors during amplicon generation for sequencing [5]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Converts genomic DNA into a library of fragments with platform-specific adapters. | Preparing samples for whole-exome or targeted gene panel sequencing on platforms like Illumina [1]. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | Size selection and purification of DNA fragments; clean-up of PCR products. | Removing primer dimers after library amplification or purifying Sanger sequencing templates [7]. |

| Fluorometric Quantification Kit (Qubit) | Accurate quantification of DNA concentration using fluorescent dyes specific to DNA. | Measuring input DNA for NGS library prep and quantifying final library yield, more accurate than UV absorbance [7]. |

| Sanger Sequencing Kit | Provides the dideoxy chain-termination reagents for cycle sequencing. | Generating sequence traces for confirmatory analysis of NGS-identified variants [6]. |

Core Metrics for Sequencing Success

In the context of validating mutant alleles, understanding key performance metrics is fundamental to designing robust experiments and accurately interpreting results. The table below defines the core metrics that influence the capability and reliability of both Sanger and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methods.

| Metric | Definition | Importance in Mutant Allele Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | The number of consecutive nucleotides (bases) produced from a single DNA fragment during a sequencing run. [9] [10] | Longer reads are beneficial for spanning repetitive genomic regions and for the de novo assembly of novel sequences or large structural variants. [10] |

| Sequencing Depth (Read Depth) | The average number of times a specific nucleotide in the genome is read during sequencing (e.g., 100x depth). [11] [12] | Higher depth increases confidence in base calls and is critical for detecting low-frequency variants (e.g., somatic mutations or heteroplasmic alleles); it directly impacts the limit of detection. [13] [12] [14] |

| Throughput | The total amount of sequence data generated by a sequencing instrument in a single run, often measured in gigabases (Gb) or terabases (Tb). [13] [10] | High-throughput platforms (NGS) enable the parallel sequencing of millions of fragments, making it feasible to screen hundreds of samples or genes cost-effectively. [13] |

Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS: A Quantitative Comparison for Validation

Choosing the appropriate sequencing technology depends on the scale and objective of your validation project. The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS.

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Length | Long; typically 800-1000 base pairs. [9] | Varies by platform; short-read (e.g., Illumina: 50-300 bp), long-read (e.g., PacBio: 15,000-20,000 bp). [10] |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | Not applicable in the same way as NGS; a single fragment is sequenced per reaction. [13] | Highly scalable; can range from tens to thousands of reads per base to detect low-frequency variants. [13] [12] |

| Throughput | Low; sequences one DNA fragment at a time. [13] | Massively parallel; sequences millions of fragments simultaneously per run. [13] |

| Key Strengths | - "Gold standard" accuracy (~99.99%). [9]- Simple data analysis. [10]- Cost-effective for interrogating a small number of targets (e.g., <20). [13] | - High sensitivity for low-frequency variants (detection limit down to ~1% vs. 15-20% for Sanger). [13] [10]- High discovery power to identify novel variants. [13]- Cost-effective for screening many targets or samples. [13] |

| Common Applications in Validation | - Validating DNA sequences, including those identified by NGS. [9] [15]- Sequencing a short region in a limited number of samples. [13] [10] | - Discovery screening for novel or rare variants across hundreds to thousands of genes. [13]- Detecting low-abundance mutations, such as in cancer or measurable residual disease (MRD). [12] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Performance Metrics

How does sequencing depth affect the detection of low-frequency mutant alleles?

Sequencing depth is the most critical factor determining the lower limit of variant detection. The limit of detection for NGS is directly related to the depth of sequencing performed. [12] For example, to confidently identify a variant present in only 1% of cells (Variant Allele Frequency, VAF = 1%), a significantly higher sequencing depth is required compared to detecting a variant present in 50% of cells. [12] A higher depth provides more statistical power to distinguish a true low-frequency variant from background sequencing errors. [11] [14] In contrast, Sanger sequencing, which produces a composite chromatogram, has a much higher limit of detection, typically around 15-20%, making it unsuitable for finding low-frequency variants. [13] [10]

My Sanger sequencing chromatogram shows mixed/overlapping peaks after a clear start. What is the cause?

A chromatogram that starts with high-quality data but then becomes mixed, showing two or more peaks at each position, typically indicates the presence of multiple DNA templates in the reaction. [16] Common causes include:

- Colony contamination: Accidentally picking more than one bacterial colony when preparing plasmid DNA for sequencing. [16]

- Multiple priming sites: The sequencing primer is binding to more than one location on the template DNA. [16]

- Incomplete PCR purification: Residual primers or salt from the PCR amplification reaction can cause spurious priming events. [16] Solution: Ensure you are sequencing a single, pure DNA template. Re-streak bacterial colonies to isolate a single clone, check your primer for specificity, and thoroughly clean up PCR products before sequencing. [16]

My sequencing data terminates abruptly. How can I resolve this issue?

Early termination in sequencing reads can occur in both Sanger and NGS workflows for different reasons.

- In Sanger sequencing: Good quality data that comes to a hard stop is often a sign of secondary structure (e.g., hairpins) in the DNA template that the polymerase cannot pass through. [16] Long stretches of Gs or Cs can cause similar issues.

- Solution: Use an alternate sequencing chemistry designed for "difficult templates," or design a new primer that sits on or just after the problematic region to sequence through it. [16]

- In NGS: A sudden drop in coverage in a specific region can be due to high GC or AT content, repeat sequences, or other genomic complexities that make library preparation or sequencing inefficient. [15] [17] Solution: Consider using library preparation methods optimized for high-GC regions and ensure you have sufficient overall sequencing depth to compensate for regions with naturally lower coverage. [17]

Experimental Protocol: Validating NGS-Identified Mutants with Sanger Sequencing

This protocol details the steps to confirm variants discovered through NGS using the Sanger method, a common practice in research and diagnostics. [15]

Primer Design

- Design primers that flank the variant of interest using a tool like Primer3. [15]

- Amplicon size should be appropriate for Sanger sequencing (typically 500-1000 bp). [9]

- Critical Check: Use tools like Primer-BLAST to check for primer specificity across the genome. Always check that the primer sequences themselves do not contain known single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as this can cause allelic dropout (ADO) and failure to amplify one allele. [15]

PCR Amplification and Purification

- Perform a standard PCR reaction using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase to minimize amplification errors. [15]

- Purify the PCR product to remove excess salts, dNTPs, and primers. This step is crucial for obtaining a high-quality Sanger sequence. [16] This can be done using enzymatic cleanup (e.g., Exonuclease I and Alkaline Phosphatase) or column-based purification kits. [15]

Sanger Sequencing Reaction and Analysis

- The purified PCR product is sequenced using a cycle sequencing reaction with fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs). [9]

- The reaction products are capillary electrophoresis to generate the chromatogram. [9]

- Analyze the chromatogram trace file (.ab1) by visually inspecting the position of the variant. The base call at the specific position should clearly correspond to the mutant allele identified by NGS. [15] [18]

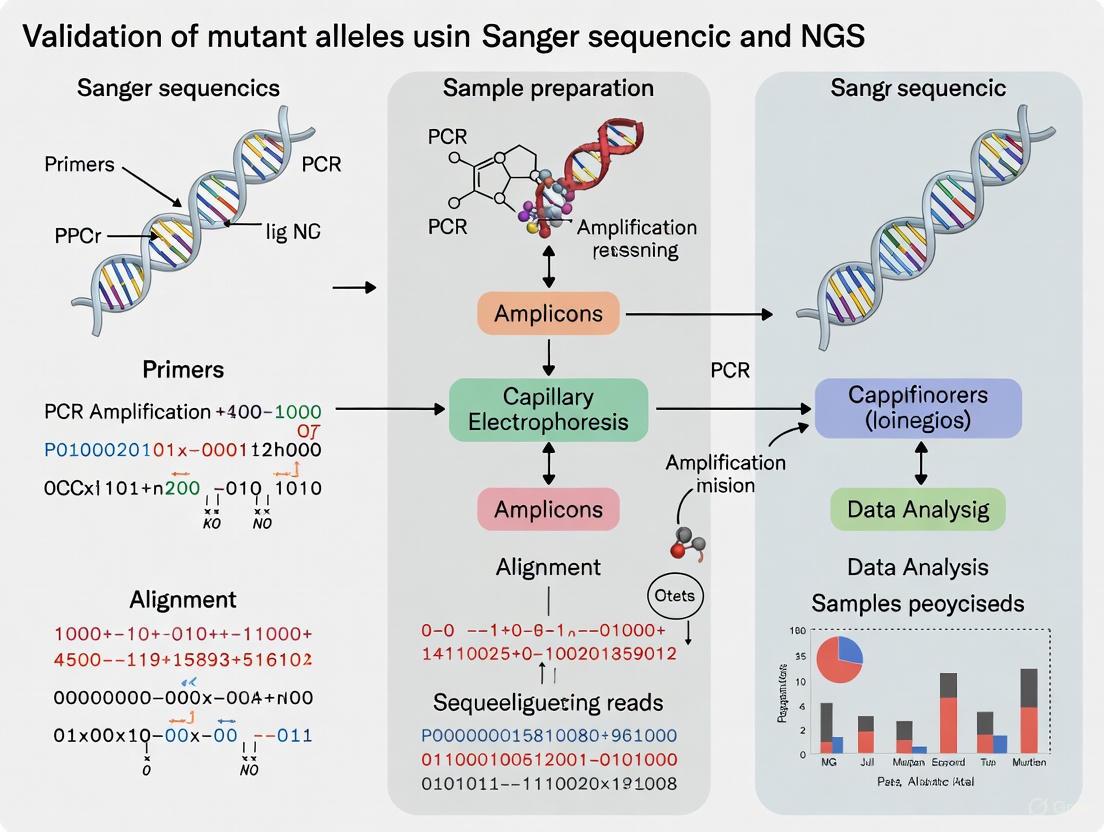

Workflow Diagram: From NGS Discovery to Sanger Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for validating a mutant allele discovered via NGS, incorporating key decision points and troubleshooting steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and materials used in sequencing workflows for mutant allele validation, along with their critical functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Used for PCR amplification prior to Sanger sequencing. Its high accuracy reduces the introduction of errors during amplification, ensuring the sequence represents the original template. [15] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences ligated to each DNA fragment in an NGS library before amplification. UMIs allow bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates and sequencing errors, improving the accuracy of variant calling, especially for low-frequency alleles. [12] |

| Sanger Sequencing Primers | Oligonucleotides designed to be complementary to the region flanking the variant of interest. They provide the starting point for the dideoxy chain-termination sequencing reaction. [9] [15] |

| Fluorescent ddNTPs | Dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, ddTTP), each labeled with a distinct fluorescent dye. They are incorporated by DNA polymerase during Sanger sequencing, terminating strand elongation and generating fragments of different lengths that are detected by capillary electrophoresis. [9] |

| Targeted Gene Panels (NGS) | A pre-designed set of probes used to capture and sequence a specific subset of genes of interest from a complex genome. This focuses sequencing power on relevant regions, allowing for higher depth and more cost-effective screening compared to whole-genome sequencing. [15] |

NGS as a Discovery Powerhouse for Novel and Rare Variants

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genetic research by enabling the simultaneous analysis of millions of DNA fragments, dramatically accelerating the discovery of novel and rare variants associated with disease [19]. Despite these technological advances, the question of how and when to validate NGS findings using Sanger sequencing remains central to rigorous scientific practice. This technical support center addresses this critical interface, providing researchers with troubleshooting guidance, validation protocols, and strategic frameworks to ensure the highest data quality while optimizing resource allocation in their discovery pipelines.

Foundational Concepts: NGS Accuracy and Validation Rationale

How accurate is NGS, and why is validation still discussed?

NGS demonstrates exceptionally high accuracy, with studies reporting validation rates of 99.965% against Sanger sequencing [20]. This performance exceeds many accepted medical tests that don't require orthogonal confirmation. Research examining over 5,800 NGS-derived variants found only 19 were not initially validated by Sanger data, and 17 of these were confirmed as true positives upon re-testing with optimized primers [20].

The persistence of validation discussions stems from several factors:

- Clinical reporting standards: Traditional guidelines often mandated orthogonal confirmation for clinical reporting [21]

- Variant-specific concerns: Certain variant types and genomic regions remain challenging

- Quality parameter thresholds: Establishing laboratory-specific quality thresholds determines which variants require confirmation [21]

What is the current consensus on Sanger validation of NGS variants?

The field is shifting toward a risk-based approach rather than universal validation. Recent research indicates that "high-quality" NGS variants defined by specific thresholds may not require routine Sanger confirmation [21] [20]. One large-scale study concluded that "validation of NGS-derived variants using Sanger sequencing has limited utility, and best practice standards should not include routine orthogonal Sanger validation of NGS variants" [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common NGS Challenges and Solutions

Library Preparation Issues

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input/Quality | Low starting yield; smear in electropherogram; low library complexity | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants; inaccurate quantification; shearing bias | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) instead of UV; assess sample quality via 260/230 and 260/280 ratios [7] |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks | Over-/under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer [7] |

| Amplification & PCR | Overamplification artifacts; bias; high duplicate rate | Too many PCR cycles; inefficient polymerase; primer exhaustion | Reduce PCR cycles; use high-fidelity polymerases; optimize primer design and annealing conditions [7] |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incomplete removal of small fragments; sample loss; carryover of salts | Wrong bead ratio; bead over-drying; inefficient washing; pipetting error | Optimize bead:sample ratios; avoid over-drying beads; implement pipette calibration [7] |

Data Quality and Variant Validation Challenges

How can I identify which NGS variants truly require Sanger validation?

Research indicates that implementing quality thresholds can drastically reduce validation workload. A study of 1,756 WGS variants established that caller-agnostic thresholds (DP ≥ 15, AF ≥ 0.25) reduced variants requiring validation to 4.8% of the initial set, while caller-dependent thresholds (QUAL ≥ 100) reduced this further to 1.2% [21].

Systematic validation decision workflow:

This workflow reflects evidence that variants meeting these quality thresholds demonstrated 100% concordance with Sanger sequencing in validation studies [21].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Robust Variant Detection

Protocol 1: Establishing Laboratory-Specific Quality Thresholds

Purpose: To determine optimal quality score thresholds that distinguish high-quality variants requiring no orthogonal validation from lower-quality variants needing Sanger confirmation.

Materials:

- NGS data from 30-50 samples with mean coverage ≥30x

- Orthogonal validation capability (Sanger sequencing)

- Bioinformatics pipeline for variant calling

Methodology:

- Call variants using your standard bioinformatics pipeline

- Annotate each variant with key parameters: DP, AF, QUAL, FILTER status

- Perform Sanger sequencing on all variants regardless of quality

- Analyze concordance between NGS and Sanger results

- Generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for each quality metric

- Determine optimal thresholds that provide 100% sensitivity for true positives

- Validate thresholds on an independent sample set

Expected Outcomes: Laboratory-specific quality thresholds that minimize unnecessary Sanger validation while maintaining >99.9% concordance for high-quality variants [21].

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting Library Preparation Failures

Purpose: To systematically diagnose and resolve common NGS library preparation problems.

Materials:

- BioAnalyzer or TapeStation

- Fluorometric quantitation system (Qubit)

- PCR purification beads

- Fresh preparation of all buffers and enzymes

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Low Library Yield Diagnosis:

- Compare Qubit and BioAnalyzer quantification values

- Check 260/230 and 260/280 ratios on nanodrop

- Examine electropherogram for adapter dimer peaks (~70-90bp)

- Verify fragmentation size distribution

- Corrective Actions:

- Re-purify input DNA if contaminants detected

- Optimize adapter:insert molar ratios (typically 1:5 to 1:10)

- Adjust bead purification ratios (typically 0.8x-1.8x)

- Verify enzyme activity and buffer conditions [7]

Advanced Applications: Rare Variants and Structural Detection

How does NGS facilitate rare variant discovery?

NGS enables rare variant analysis through several strategic approaches:

- Gene-level association tests: Overcome power limitations by aggregating rare variants within functional units [22]

- Burden tests: Compare whether rare variants in a gene are associated with traits by analyzing the total number of rare variants [22]

- Sequence kernel association tests (SKAT): Detect associations without assuming all variants have the same effect direction [22]

What specialized approaches detect structural variants?

Long-read sequencing technologies address NGS limitations in detecting structural variants (SVs):

Performance Comparison of Long-Read Technologies:

| Feature | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore (ONT) |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 10–25 kb | Up to >1 Mb |

| Accuracy | >99.9% | ~98–99.5% |

| Strengths | Exceptional accuracy, clinical applications | Ultra-long reads, portability, real-time analysis |

| SV Detection F1 Score | >95% | 85–90% |

Long-read sequencing increases diagnostic yield by 10–15% in rare disease populations after extensive short-read sequencing fails to provide diagnoses [23]. These technologies particularly excel at resolving complex SVs in repetitive regions that are inaccessible to short-read technologies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I always validate NGS variants by Sanger before publication?

Not necessarily. The 2025 study on WGS variants recommends that high-quality variants meeting specific thresholds do not require validation [21]. For clinical reporting, each laboratory should establish a confirmatory testing policy based on their validated quality thresholds [21]. Research publications should clearly state validation practices and quality metrics.

What are the most critical parameters for defining "high-quality" variants?

Caller-agnostic parameters:

Caller-specific parameters:

How does NGS performance compare with standard techniques clinically?

In non-small cell lung cancer, NGS demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy compared to standard techniques:

Diagnostic Performance in Advanced NSCLC:

| Mutation Type | Tissue Sensitivity | Tissue Specificity | Liquid Biopsy Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 93% | 97% | 80% |

| ALK rearrangements | 99% | 98% | Limited |

| BRAF V600E | - | - | 80% |

| KRAS G12C | - | - | 80% |

Liquid biopsy NGS had significantly shorter turnaround time (8.18 vs. 19.75 days; p < 0.001) compared to standard tissue testing [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function in NGS Workflow | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SureSelect/SureSelect ICGC System | Solution-hybridization exome capture | Target enrichment for WES; ensure adequate input DNA [20] |

| TruSeq systems (V1/V2) | Library preparation | Compatible with Illumina platforms; follow manufacturer's cycling recommendations [20] |

| Qubit fluorometric system | Nucleic acid quantification | More accurate than UV spectrophotometry for library quantification [7] |

| AMPure XP beads | Library purification and size selection | Optimize bead:sample ratio for target fragment retention [7] |

| HaplotypeCaller (GATK) | Variant calling | Generate QUAL scores for variant filtering; version-dependent parameters [21] |

| DeepVariant | Variant calling | Alternative caller for verification; performs well on challenging variants [21] |

The powerful synergy between NGS discovery and strategic validation enables researchers to maximize both efficiency and accuracy in variant detection. By implementing evidence-based quality thresholds, establishing laboratory-specific validation protocols, and leveraging appropriate technologies for different variant types, research and clinical laboratories can harness the full potential of NGS as a discovery powerhouse for novel and rare variants while maintaining rigorous standards of verification.

Sanger Sequencing as the Gold Standard for Targeted Confirmation

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genetic discovery, enabling the simultaneous analysis of hundreds to thousands of genes. However, in both clinical and research settings, the verification of critical genetic variants, such as suspected mutant alleles, remains paramount. Within this framework, Sanger sequencing continues to be employed as the trusted gold standard for orthogonal validation of NGS-derived variants prior to reporting. This guide provides targeted technical support, offering detailed troubleshooting and best practices to ensure that your Sanger confirmation data is of the highest quality, thereby solidifying the reliability of your genetic findings.

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Foundational Principles

1. Why is Sanger sequencing still considered the gold standard for validating NGS variants?

Sanger sequencing is regarded as a gold standard due to its high accuracy (over 99%) and the straightforward interpretability of its output data [25]. It provides long reads (500-1000 base pairs) from a single, specific amplicon, making it ideal for confirming individual variants identified by broader, more complex NGS tests [26]. This orthogonal method uses a completely different chemistry and workflow than NGS, providing an independent check that minimizes the risk of systematic errors.

2. Is it always necessary to validate NGS variants with Sanger sequencing?

Emerging evidence from large-scale studies suggests that for high-quality NGS variants, Sanger confirmation may be redundant. One systematic evaluation of over 5,800 NGS variants found a validation rate of 99.965%, concluding that routine Sanger validation has limited utility [20]. Another study of 1,109 variants from 825 clinical exomes showed 100% concordance for high-quality single-nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions, suggesting labs can establish their own quality thresholds to discontinue universal Sanger confirmation [27].

3. What are the key limitations of Sanger sequencing compared to NGS?

The primary limitation is throughput. Sanger sequencing is designed to interrogate one DNA fragment per reaction, whereas NGS is massively parallel, sequencing millions of fragments simultaneously [13]. This makes Sanger cost-effective for a low number of targets (~20 or fewer) but impractical for sequencing large numbers of genes or samples. Sanger also has a higher limit of detection (~15-20%), making it less sensitive for identifying low-frequency variants in heterogeneous samples compared to deep sequencing with NGS [13] [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

The table below summarizes frequent problems, their causes, and solutions.

| Problem | Identifying Characteristics | Possible Causes & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Failed Reaction [16] | Sequence data contains mostly N's; messy trace with no discernable peaks. | - Cause: Low template concentration, poor quality DNA, or contaminants.- Solution: Precisely quantify DNA (e.g., with a NanoDrop); ensure A260/A280 ratio is ~1.8; clean up DNA to remove salts and primers. |

| High Background Noise [16] [28] | Discernable peaks with significant background noise along the baseline; low quality scores. | - Cause: Low signal intensity from poor amplification, often due to low template concentration or inefficient primer binding.- Solution: Optimize template concentration; check primer design and binding efficiency. |

| Sequence Degradation/ Early Termination [16] [28] | High-quality sequence starts strongly but stops prematurely or becomes messy. Signal intensity drops sharply. | - Cause: Secondary structures (e.g., hairpins) or long homopolymer stretches that the polymerase cannot pass through. Too much template DNA can also cause this.- Solution: Use an alternate sequencing chemistry designed for "difficult templates"; redesign primer to sequence from the opposite strand; optimize template concentration. |

| Mixed Sequence (Double Peaks) [16] [29] | The sequence trace becomes mixed, showing two or more peaks at the same position starting from a certain point or from the beginning. | - Cause: Multiple templates in the reaction (e.g., colony contamination, multiple priming sites, or insufficient PCR cleanup leaving residual primers).- Solution: Ensure a single colony is picked; verify primer specificity to a single site; perform thorough PCR cleanup. |

| Dye Blobs [16] [28] | Large, broad peaks (typically C, G, or T) that can obscure base calling, often seen around 70 base pairs. | - Cause: Incomplete removal of unincorporated dye terminators during cleanup, or contaminants in the DNA sample.- Solution: Ensure proper cleanup procedure (e.g., ensure sample is dispensed onto the center of spin columns, vortex thoroughly with BigDye XTerminator reagent). |

| Poor Data After a Mononucleotide Repeat [16] | Sequence trace becomes mixed and unreadable after a stretch of a single base (e.g., AAAAA). | - Cause: DNA polymerase slippage on the homopolymer stretch.- Solution: Design a new primer that binds just after the problematic region to sequence through it. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation and Submission for Sanger Sequencing

This protocol ensures the generation of high-quality template DNA for reliable sequencing results [29] [26].

- Amplicon Generation: Perform PCR using primers designed with online tools (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST, Primer3). The amplicon size should be appropriate for your sequencing instrument (typically up to 800-1000 bp).

- Verify Amplicon Purity: Analyze the PCR product by gel or capillary electrophoresis. A single, sharp band must be present. If multiple bands are seen, gel purification of the specific band of interest is required.

- Purify the Amplicon: Use a commercial bead-based or column-based PCR purification kit to remove excess salts, dNTPs, enzymes, and primers from the PCR reaction. This step is critical for a clean sequencing reaction.

- Quantify Accurately: Precisely measure the concentration of the purified DNA. Using a instrument like a NanoDrop is recommended for low-volume quantification. Ensure the A260 reading is between 0.1 and 0.8 for accuracy; dilute the sample if necessary [29].

- Submit with Correct Concentrations: Submit the DNA and primer at the recommended concentrations. General guidelines for template quantity per reaction are provided in the table below [28].

Table: Recommended Template Quantities for Sanger Sequencing

| DNA Template Type | Quantity per Reaction (non-BDX cleanup) | Quantity per Reaction (with BigDye XTerminator cleanup) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Product: 100–500 bp | 3–10 ng | 1–10 ng |

| PCR Product: 500–1000 bp | 5–20 ng | 2–20 ng |

| Plasmid DNA | 150–300 ng | 50–300 ng |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) | 0.5–1.0 μg | 0.2–1.0 μg |

Protocol 2: Validation of NGS-Derived Variants

This protocol outlines the steps for using Sanger sequencing to confirm a variant identified via NGS [27].

- Variant Review from NGS: Identify the variant (SNV or indel) and its genomic coordinates from your NGS analysis pipeline. Ensure it meets high-quality thresholds (e.g., PASS filter, depth ≥20x, variant fraction ≥20%).

- Primer Design: Design primers to amplify a 400-700 bp region surrounding the variant of interest.

- Follow best practices: primers should be 18-24 bases, have a Tm of 50-60°C, and GC content of 45-55% [30].

- Check for specificity using tools like UCSC In-Silico PCR.

- Check for common SNPs in the primer-binding site using a tool like SNPcheck to avoid allele-specific amplification failure.

- Wet-Lab Validation: Perform PCR and Sanger sequencing as outlined in Protocol 1, sequencing in both the forward and reverse directions for bidirectional confirmation.

- Data Analysis: Manually inspect the chromatogram in the region of the variant using a viewer like SnapGene or FinchTV. Confirm the presence of the expected base change in the sequencing trace. For heterozygous variants, look for two overlapping peaks at the variant position.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Sanger Sequencing Validation

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BigDye Terminator Kit [28] | The core chemistry for cycle sequencing. Contains fluorescently labeled ddNTPs, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer. | Store properly, protect from light, and check expiration dates. Includes control DNA (pGEM) for troubleshooting. |

| PCR Purification Kit [29] [26] | Removes unwanted components from PCR reactions (primers, enzymes, salts) to provide a clean template. | Bead-based or column-based. Critical for reducing background noise and failed reactions. |

| Hi-Di Formamide [28] | Used to resuspend the sequencing reaction product before capillary electrophoresis. Facilitates sample denaturation. | A standard component of the injection process. |

| BigDye XTerminator Kit [28] | Purification kit for removing unincorporated dye terminators and salts from sequencing reactions via a bead-based method. | Helps eliminate "dye blobs" and reduces salt artifacts. Vortexing is a critical step for success. |

| pGEM Control DNA & Primer [28] | Provided in the BigDye kit. Used as a positive control to determine if a failed reaction is due to template/primers or other issues. | Essential for systematic troubleshooting of failed runs. |

The Critical Role of Orthogonal Validation in Clinical and Research Settings

Orthogonal validation, the practice of confirming genetic variants using a method fundamentally different from the initial discovery technique, is a cornerstone of reliable clinical and research genomics. In the context of next-generation sequencing (NGS), this most often involves confirming variants with Sanger sequencing, the established gold standard for accuracy [31]. Despite the high throughput of NGS, the technique is not error-free; factors such as sequencing artifacts, alignment challenges in complex genomic regions, and bioinformatic filtering limitations can introduce false positives and false negatives [15] [31]. Orthogonal validation acts as a critical quality control step to ensure the accuracy of variants before they are reported, used in patient diagnosis, or inform therapeutic decisions, thereby upholding the highest standards of data integrity and patient safety [32].

The Necessity of Validation: Quantitative Evidence

The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies that have systematically evaluated the concordance between NGS and Sanger sequencing, providing a quantitative basis for validation practices.

| Study Focus / Panel Type | Cohort / Variant Size | Key Concordance Finding | Notes and Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [21] | 1,756 variants from 1,150 patients | 99.72% (5 discrepancies) | Sanger validation is crucial for variants with low-quality scores. |

| Exome Sequencing (ClinSeq Cohort) [20] | ~5,800 NGS-derived variants | >99.9% (19 initial discrepancies, 17 resolved for NGS) | A single Sanger round may incorrectly refute a true NGS variant. |

| Targeted Gene Panels (Illumina MiSeq/Haloplex) [15] | 945 variants from 218 patients | >99% (3 discrepancies, all resolved in favor of NGS) | Allelic dropout during Sanger sequencing can cause discrepancies. |

| Machine Learning for Sanger Bypass [33] | Model trained on GIAB benchmarks | 99.9% precision and 98% specificity achieved | ML models can reliably identify high-confidence SNVs, reducing confirmatory testing needs. |

These studies demonstrate that while the vast majority of high-quality NGS variants are confirmed, a small but critical number of discrepancies exist. Furthermore, evidence suggests that not all discrepancies are due to NGS errors, highlighting that Sanger sequencing, while a gold standard, is not itself infallible [15] [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Sanger Validation of NGS-Detected Variants

This is a common workflow for confirming variants identified through targeted NGS panels or whole exome/genome sequencing [15] [31].

1. Variant Identification and Selection:

- Perform NGS using your established platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq) and bioinformatic pipeline (e.g., BWA-MEM for alignment, GATK HaplotypeCaller for variant calling) [15].

- Filter variants based on quality metrics. Variants for validation are often selected according to criteria such as:

2. Primer Design:

- Design oligonucleotide primers that flank the target variant using tools like Primer3 [15].

- Critical Step: Check primer sequences against a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) database to ensure no common variants interfere with primer binding, which can cause allelic dropout [15].

- Verify amplicon specificity using a tool like Primer-BLAST [15]. A typical amplicon size is 500-800 base pairs [20].

3. PCR Amplification and Purification:

- Set up a 25 µL PCR reaction using approximately 100 ng of genomic DNA, standard PCR buffers, dNTPs, and a robust DNA polymerase (e.g., FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase) [15].

- Purify the PCR products to remove excess primers and dNTPs using an enzymatic cleanup mixture (e.g., Exonuclease I and Alkaline Phosphatase) [15].

4. Sanger Sequencing and Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Perform the sequencing reaction using a chain-termination kit (e.g., BigDye Terminator v1.1 or v3.1) [20] [21].

- Purify the sequencing reactions to remove unincorporated dyes.

- Run the products on a capillary electrophoresis sequencer (e.g., ABI 3500Dx or 3730xl Genetic Analyzer) [15] [33].

5. Data Analysis:

- Analyze the resulting chromatograms using software such as GeneStudio Pro, Sequencher, or UGENE [33].

- Manually inspect the chromatogram for the variant position, assessing peak clarity, shape, and the absence of artifacts to confirm the NGS call [34] [20].

Protocol 2: Orthogonal NGS for High-Throughput Confirmation

For large-scale studies where Sanger validation of thousands of variants is impractical, an orthogonal NGS approach can be used [35].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Extract genomic DNA from patient samples (e.g., from whole blood).

2. Orthogonal Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare two independent NGS libraries for each sample using fundamentally different technologies:

- Sequence the libraries on different platforms with distinct chemistries (e.g., Illumina NextSeq with reversible terminators and Ion Proton with semiconductor sequencing) [35].

3. Data Integration and Analysis:

- Analyze data from each platform independently using their respective optimized bioinformatic pipelines.

- Use a custom algorithm or combinatorial tool to integrate variant calls from both platforms.

- Classify variants based on whether they are called by one or both platforms. Variants identified by both orthogonal methods have a significantly higher positive predictive value (PPV) and can be reported without Sanger confirmation, while those on only one platform are flagged for further review [35].

Orthogonal NGS Confirmation Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our lab is moving to whole genome sequencing (WGS). Are the standard quality thresholds for validating NGS variants still applicable?

A: WGS data, often with a lower mean coverage (~30-40x) than targeted panels, requires specific consideration. A 2025 study on WGS data suggests that while previously published thresholds (e.g., QUAL ≥ 100, DP ≥ 20, AF ≥ 0.2) work with 100% sensitivity (all false positives filtered out), their precision is low. For WGS, the study recommends:

- Caller-agnostic thresholds: DP ≥ 15 and AF ≥ 0.25 to achieve high precision while maintaining sensitivity [21].

- Caller-specific threshold: Using a QUAL ≥ 100 (for GATK HaplotypeCaller) alone can drastically reduce the need for Sanger validation, filtering out ~98% of variants into a "high-quality" bin [21]. Each laboratory should validate thresholds for their specific WGS pipeline.

Q2: I am getting a discrepancy between NGS and Sanger sequencing, where the NGS data shows a heterozygous variant but Sanger appears homozygous wild-type. What is the most likely cause?

A: This is a classic symptom of Allelic Dropout (ADO) during the Sanger sequencing process. This occurs when one allele fails to amplify in the initial PCR step, often due to:

- A private SNP in the primer-binding site: A genetic variant present in your sample (but not in the reference genome) prevents one of the primers from annealing correctly [15].

- Solution: Redesign your PCR primers, shifting them further away from the variant location, and re-run the Sanger validation. Always check primers against SNP databases during the design phase [15].

Q3: When looking at my Sanger chromatogram, what are the key indicators of a high-quality, reliable result?

A: A high-quality chromatogram will have:

- Low and flat baseline between peaks, indicating minimal background noise [34].

- Sharp, single, and symmetrical peaks for each base call [34].

- Even spacing between consecutive peaks, which reflects uniform DNA fragment migration [34]. Be wary of broad or overlapping peaks (compressions), double peaks (potential heterozygosity or polymerase stuttering), and "dye blobs" (large, misshapen peaks caused by unincorporated dye) [34].

Q4: Is orthogonal validation still necessary for all NGS variants, given the improving technology?

A: The field is evolving. Best practices are shifting from blanket Sanger validation for all variants to a more nuanced, risk-based approach.

- For high-quality variants: Recent guidelines suggest that "high-quality" NGS variants meeting strict, lab-validated thresholds for depth, allele frequency, and quality scores may not require Sanger confirmation [20] [21].

- For borderline or clinically critical variants: Orthogonal validation remains essential for variants with low-quality scores, those in difficult-to-sequence regions (e.g., high GC-content, homopolymers), and those with major clinical implications [15] [32].

- Emerging approaches: Machine learning models are now being trained to automatically classify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) as high or low-confidence, significantly reducing the burden of orthogonal confirmation while maintaining >99.9% precision [33].

Modern Variant Validation Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials required for the orthogonal validation workflows described.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase (Robust) | PCR amplification of target regions from genomic DNA prior to Sanger sequencing. | FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase Kit [15] |

| Exonuclease I / Alkaline Phosphatase | Enzymatic cleanup of PCR products to degrade excess primers and dNTPs that would interfere with the Sanger sequencing reaction. | ExoStar Cleanup Mix [15] |

| Cycle Sequencing Kit | Contains fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) and DNA polymerase for the chain-termination sequencing reaction. | BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit [20] [21] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis Sequencer | Instrument for separating sequencing fragments by size and detecting fluorescent signals to generate the chromatogram. | Applied Biosystems 3500xL or 3730xl Genetic Analyzer [15] [33] |

| Hybridization-Based Capture Kit | For target enrichment in orthogonal NGS workflows; uses biotinylated probes to capture genomic regions of interest. | Agilent SureSelect Clinical Research Exome (CRE) [35] |

| Amplification-Based Capture Kit | For orthogonal target enrichment; uses a multiplex PCR approach to amplify target regions. | Ion AmpliSeq Exome Kit [35] |

| Primer Design Software | Critical for designing specific primers for Sanger validation that avoid known SNPs. | Primer3 [15], Primer3Plus [33] |

From Data to Validation: Implementing Robust Workflows for Mutant Allele Confirmation

Establishing a Best-Practice NGS-to-Sanger Validation Pipeline

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic analysis in research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the simultaneous detection of millions of variants. However, the establishment of a robust validation pipeline remains crucial for ensuring data accuracy, particularly for variant confirmation. Sanger sequencing, often termed the "gold standard" for DNA sequencing, continues to play a vital role in orthogonal validation of NGS-derived variants, especially in contexts where definitive proof is required for clinical decision-making or publication [36] [37]. This technical resource center provides comprehensive guidance for establishing an efficient NGS-to-Sanger validation workflow, complete with troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions to address common experimental challenges.

The necessity for Sanger validation stems from various potential sources of error in NGS workflows, including those introduced during library preparation, sequencing, or bioinformatic analysis [38]. Factors such as low read depth, sequencing errors in GC-rich regions, and alignment difficulties can generate false positive or false negative results [38]. While recent evidence suggests that high-quality NGS variants demonstrate exceptionally high validation rates (exceeding 99.9%), confirmation remains particularly important for variants with borderline quality metrics or those with significant clinical implications [20] [21].

Establishing Validation Guidelines: When is Sanger Confirmation Necessary?

Quality Thresholds for High-Confidence NGS Variants

Recent large-scale studies have established that variants meeting specific quality thresholds may not require routine Sanger validation, potentially saving significant time and resources. The following table summarizes evidence-based quality metrics for identifying high-confidence NGS variants:

Table 1: Evidence-Based Quality Thresholds for NGS Variant Validation

| Study | Sequencing Type | Sample Size | Concordance Rate | Recommended Quality Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClinSeq Study [20] | Exome Sequencing | 5,800+ variants | 99.965% | MPG score ≥10 |

| WGS Validation [21] | Whole Genome Sequencing | 1,756 variants | 99.72% | FILTER=PASS, QUAL≥100, DP≥15, AF≥0.25 |

| Multi-Center Analysis [38] | Targeted Gene Panels | 945 variants | >99% | Depth≥30×, Phred Q≥30, Allele Balance>0.2 |

Based on this accumulated evidence, a practical validation pipeline can be established that prioritizes Sanger confirmation for variants failing to meet these quality thresholds, while potentially exempting high-quality variants from additional validation.

Decision Framework for Sanger Validation

The following workflow diagram provides a visual guide for determining when Sanger validation is necessary based on variant characteristics and quality metrics:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful Sanger validation requires careful selection of laboratory reagents and materials. The following table outlines key components for establishing a reliable validation workflow:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for NGS-to-Sanger Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications & Quality Controls |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Primers [30] [38] | Amplification of target regions for Sanger sequencing | 18-24 bases; Tm 50-60°C; GC content 45-55%; Check for SNPs in binding sites |

| DNA Polymerase [38] | PCR amplification of target regions | High-fidelity enzymes; validated for genomic DNA |

| BigDye Terminators [20] [38] | Fluorescent dideoxy terminator sequencing | Kit version 1.1 or 3.1; proper storage conditions |

| Purification Systems [30] [7] | Cleanup of PCR products and sequencing reactions | Ethanol precipitation, column-based, or bead-based systems |

| Size Selection Beads [7] | Removal of primer dimers and nonspecific products | SPRl, AMPure, or similar; fresh ethanol washes |

| Capillary Electrophoresis Polymers [36] | Matrix for fragment separation in sequencers | Performance-optimized polymers for sequence resolution |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Failed or Poor-Quality Sanger Sequencing

Problem: Sequencing reactions produce poor-quality chromatograms or fail entirely.

Solutions:

- Primer Design Issues: Verify primers are 18-24 bases with 45-55% GC content and melting temperature of 56-60°C [30] [39]. Avoid primers with secondary structures or self-complementarity.

- Template Contamination: Check for contaminants by assessing 260/230 ratios (<1.6 suggests organic contaminants) and ensure elution buffers do not contain EDTA [30].

- Template Quality: Assess DNA purity via spectrophotometry (260/280 ratio ~1.8) and quantify using fluorometric methods rather than UV absorbance alone [39] [7].

- Difficult Templates: For GC-rich regions or templates with secondary structures, use specialized protocols or additives (e.g., DMSO, betaine) to improve sequencing through problematic regions [30] [39].

Discrepancies Between NGS and Sanger Results

Problem: Variants identified by NGS are not confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Solutions:

- Investigate Allelic Dropout (ADO): ADO during PCR amplification can cause false negatives in Sanger sequencing, particularly if polymorphisms occur in primer-binding sites [38]. Redesign primers to bind to alternative regions.

- Verify NGS Quality Metrics: Check that the NGS variant meets established quality thresholds (depth, quality scores, allele frequency) before pursuing validation [21].

- Review Sanger Experimental Conditions: Optimize PCR conditions and consider repeating Sanger sequencing with newly designed primers before concluding the NGS result is a false positive [20] [38].

Low NGS Library Yield

Problem: Inadequate library quantity for sequencing, potentially affecting variant calling.

Solutions:

- Input DNA Quality: Re-purify input DNA if contaminants are suspected (residual phenol, salts, EDTA) and verify purity ratios (260/230 > 1.8, 260/280 ~1.8) [7].

- Quantification Accuracy: Use fluorometric quantification (Qubit, PicoGreen) rather than UV spectrophotometry alone, as the latter may overestimate usable DNA [7].

- Adapter Ligation Efficiency: Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratios and ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions (temperature, buffer) [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is Sanger validation still necessary for all NGS-derived variants in clinical diagnostics?

A: Not necessarily. Recent evidence demonstrates that NGS variants meeting established quality thresholds (e.g., depth ≥15×, allele frequency ≥0.25, quality score ≥100) show >99.9% concordance with Sanger sequencing [20] [21]. Many laboratories are implementing policies that exempt high-quality variants from mandatory Sanger confirmation, particularly for research applications. Clinical applications may maintain stricter requirements, especially for variants with significant medical implications.

Q2: What are the most critical factors in designing primers for Sanger validation?

A: Optimal primer characteristics include: length of 18-24 bases, melting temperature between 56-60°C, GC content of 45-55%, and a G or C base at the 3' end [30] [39]. Crucially, primers should be designed to avoid known polymorphisms in binding sites and should be tested for specificity using tools like Primer-BLAST [38].

Q3: How can I troubleshoot a specific variant that fails Sanger validation despite good NGS quality metrics?

A: First, repeat the Sanger sequencing with newly designed primers to exclude allelic dropout due to polymorphisms in primer binding sites [38]. Second, verify that the variant does not reside in a region with technical challenges (high GC content, repetitive elements). Third, if possible, confirm using an alternative method such as a different NGS approach or digital PCR [21].

Q4: What are the key differences between Sanger sequencing and NGS that justify using both methods?

A: Sanger sequencing provides long, contiguous reads (500-1000 bp) with very high per-base accuracy (Q50, or 99.999%) but limited throughput [36]. NGS generates millions of shorter reads (50-300 bp) with slightly lower per-read accuracy, but achieves high overall accuracy through deep coverage [36]. The combination leverages NGS's comprehensive screening capability with Sanger's precision for specific variant confirmation.

Q5: What specific quality metrics should I examine for NGS variants prior to Sanger validation?

A: Key metrics include: depth of coverage (DP ≥15), variant quality score (QUAL ≥100), allele frequency (AF ≥0.25 for heterozygous calls), and FILTER status (PASS) [21]. Additionally, visual inspection of aligned reads using a genome browser can identify alignment issues or strand bias that might indicate false positives.

As NGS technologies continue to mature, the requirements for orthogonal Sanger validation are evolving. The current evidence supports a balanced approach that utilizes quality thresholds to identify high-confidence variants that may not require confirmation, while maintaining Sanger sequencing for borderline cases or clinically impactful findings. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, reagent specifications, and quality thresholds outlined in this technical resource, researchers and clinicians can establish efficient, cost-effective validation pipelines that maintain rigorous standards for variant verification.

Primer Design Strategies for Amplifying and Sequencing Target Mutations

Core Design Parameters for Effective Primers

Adhering to established parameters for primer design is fundamental for successful amplification and sequencing of target mutations. The following table summarizes the key quantitative criteria to guide your primer design process.

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Importance & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 17–25 nucleotides [40], ideally 18–24 bases [41] [39] | Balances specificity (long enough) with binding efficiency (not too long). |

| GC Content | 40%–60% [42], ideally 45%–55% [39] or ~50% [41] [40] | Ensures stable primer-template binding; extremes can cause instability or non-specific binding. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 50–70°C [40], ideally 55–65°C [40] or 56–60°C [39] | Critical for setting the correct annealing temperature; primers in a pair should be within 2°C of each other [42]. |

| GC Clamp | 1-2 G/C bases at the 3' end; avoid >3 G/C in the last 5 bases [42] | Stabilizes binding at the 3' end where polymerase initiation occurs, but too many can promote mispriming. |

| Avoid | Poly-base regions, dinucleotide repeats, self-complementary sequences [41] [42] | Prevents mispriming, slippage, and the formation of secondary structures like hairpins and primer-dimers. |

Workflow for Primer Design and Validation

A systematic approach to primer design, from target definition to in silico validation, ensures the highest chance of experimental success. The workflow below outlines this process.

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Define Your Target Region: Select the exact genomic or cDNA interval you wish to sequence. Obtain the reference sequence from a curated database like NCBI RefSeq or Ensembl using a FASTA format or accession number. Decide on primer flanking boundaries so that the primers bind outside the variant or region of interest [42].

- Use Primer Design Tools: Utilize online tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST, which integrates the design engine of Primer3 with specificity checking via BLAST [42]. In the interface, input your target sequence and set constraints such as:

- Product size range: For Sanger sequencing, ensure your PCR product is at least 200 bp, with 500 bp or more being ideal [39].

- Tm limits and maximum Tm difference (e.g., ≤2°C).

- Organism specificity to limit off-target priming [43] [42].

- Exon/intron constraints if designing for cDNA vs. genomic templates [43].

- Evaluate and Filter Candidate Primers: For each suggested primer pair from the tool, check that their GC% and Tm fall within the optimal design criteria. Screen for secondary structures and primer-dimer formation using thermodynamic tools (e.g., OligoAnalyzer). Prefer primer pairs that show minimal off-target matches in the Primer-BLAST specificity report [42].

- In Silico Validation and Final Selection: Simulate amplicons using in silico PCR tools (e.g., UCSC in silico PCR) to confirm the expected product size and the absence of spurious products. Record the final primer sequences, Tm, GC%, amplicon size, and expected specificity [42].

Troubleshooting Common Primer Design Issues

Why is my sequencing result poor or blank?

- Problem: Insufficient primer binding to the template.

- Solution: Verify that your primer is designed with a Tm of 56–60°C and a GC content of 45–55% [39]. Ensure the primer matches the template exactly, especially in the last 8 bases at the 3' end [40]. Avoid primers that can form hairpin loops or primer-dimers [42] [40].

How do I prevent non-specific amplification or multiple bands?

- Problem: Primer binds to off-target sites.

- Solution: Always use Primer-BLAST to check primer specificity against the target organism's genome [43] [42]. Increase the stringency of the annealing temperature (Ta) by 2–5°C [42]. Avoid placing primers in repetitive or homologous sequence regions [42].

What causes primer-dimer formation and how can I avoid it?

- Problem: Primers anneal to themselves or each other.

- Solution: Redesign primers to avoid complementarity, especially at the 3' ends. Use analysis tools to screen for dimer formation and eliminate primers with strong predicted binding (ΔG values that are too negative) [42]. For highly multiplexed PCR, advanced algorithms like SADDLE can be used to minimize dimer formation across large primer sets [44].

Why is the signal weak or the coverage uneven in my NGS data?

- Problem: Imbalanced primer efficiency or overamplification.

- Solution: For multiplex PCR panels, ensure all primers in the set have closely matched Tm values to ensure uniform amplification [42]. Avoid an excessive number of PCR cycles, which can introduce size bias and increase duplicate rates [7]. Verify the quantity and quality of the input library [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | A free online tool that designs primer pairs and checks their specificity against a selected database to ensure they only amplify the intended target [43] [42]. |

| Betaine | An additive used in Sanger sequencing reactions to lower the Tm and anneal temperature of the primer, helping to sequence through templates with high GC content or secondary structures [40] [39]. |

| DMSO | A stabilizer added to PCR reactions to improve the amplification of GC-rich regions or complex templates by reducing secondary structure formation [42]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes the template-dependent synthesis of DNA during PCR and sequencing; essential for cycle sequencing in Sanger methods [13]. |

| SADDLE Algorithm | A computational framework (Simulated Annealing Design using Dimer Likelihood Estimation) for designing highly multiplexed PCR primer sets that minimize primer-dimer formation [44]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is orthogonal validation with Sanger sequencing still necessary for NGS-identified variants?

While NGS technologies can identify millions of variants simultaneously, validation remains crucial for confirming potentially causative mutations before reporting. Sanger sequencing provides an orthogonal method with exceptionally high accuracy at the single-base level, serving as the "gold standard" for verifying variants detected through NGS pipelines. This is particularly important for clinical reporting and research validation, as NGS platforms can produce false positives due to sequencing artifacts, alignment errors, or amplification biases. Current guidelines recommend that each laboratory establish a confirmatory testing policy for variants, with Sanger sequencing being the most widely accepted method for this purpose [21] [32].

Q2: What are the key quality thresholds for determining which NGS variants require Sanger validation?

Research indicates that establishing quality thresholds can significantly reduce the number of variants requiring validation. Based on recent studies of 1756 WGS variants, the following thresholds effectively separate high-quality variants from those needing confirmation [21]:

Table: Quality Thresholds for NGS Variant Validation

| Parameter Type | Parameter | Recommended Threshold | Precision Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caller-Agnostic | Depth (DP) | ≥15 | 6.0% |

| Caller-Agnostic | Allele Frequency (AF) | ≥0.25 | 6.0% |

| Caller-Dependent | Quality (QUAL) | ≥100 | 1.2% |

Implementing these thresholds can reduce Sanger validation to just 1.2-6.0% of the initial variant set, significantly saving time and resources while maintaining accuracy [21].

Q3: What are the optimal primer design parameters for Sanger sequencing validation?

Proper primer design is critical for successful Sanger sequencing. Follow these evidence-based guidelines [45]:

- Length: 18-30 bases

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 60-64°C (ideal 62°C)

- Tm Difference Between Primers: ≤2°C

- GC Content: 35-65% (ideal 50%)

- Amplicon Length: 70-150 bp for optimal amplification (up to 500 bp possible)

- Avoid: Regions of 4 or more consecutive G residues

- Specificity: Verify uniqueness to target sequence using BLAST analysis

Q4: How do I troubleshoot failed Sanger sequencing reactions?

Failed reactions can result from multiple factors. Consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Check Primer Quality: Ensure primers are properly purified, dissolved, and stored. Verify secondary structures using tools like OligoAnalyzer (ΔG > -9.0 kcal/mol) [45].

- Optimize Template Quality: Assess DNA purity (A260/280 ratio ~1.8-2.0) and quantity. Avoid degraded or inhibitor-contaminated samples.

- Validate Thermal Cycler Conditions: Confirm annealing temperature is set 5°C below primer Tm. Verify extension times are sufficient for amplicon length.

- Review Sequencing Chemistry: Ensure proper BigDye terminator ratios and cycling conditions. Verify capillary electrophoresis injection parameters.

- Inspect Electroherogram: Poor signal may indicate low template concentration, while multiple peaks may suggest primer dimer formation or contamination.

Q5: When should Sanger sequencing not be used for NGS validation?

Sanger sequencing has limitations in certain scenarios [46]:

- Low Variant Allele Frequency (VAF): Sanger detection sensitivity is limited to approximately 10-20% VAF, making it unsuitable for validating low-frequency somatic mutations in heterogeneous tumor samples.

- Large-Scale Validation: When dealing with hundreds of variants, Sanger sequencing becomes impractical due to throughput limitations and cost.

- Complex Structural Variants: Large insertions, deletions, or rearrangements may be challenging to validate with Sanger sequencing alone.

- Routine Clinical NGS: For well-validated NGS pipelines with established quality metrics, some laboratories are moving toward eliminating orthogonal validation for high-quality variants.

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Sequence Quality in Sanger Validation

Symptoms: Low signal-to-noise ratio, high background, unreadable sequences.

Solution Protocol:

Template Quality Control

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accuracy

- Verify DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis

- Perform PCR optimization with template dilution series (1-100 ng)

Primer Re-design and Validation

- Re-design primers following optimal parameters above

- Include positive control primers for known working amplicons

- Verify primer specificity using in silico PCR tools

Sequencing Reaction Optimization

- Prepare fresh BigDye terminator mixtures

- Optimize primer concentration (0.5-3.2 μM range)

- Test different thermal cycling conditions:

- 96°C for 1 minute (initial denaturation)

- 25-30 cycles of: 96°C for 10s, 50°C for 5s, 60°C for 4 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

Purification Improvement

- Implement ethanol/sodium acetate precipitation for cleaner results

- Consider alternative purification methods (column-based, magnetic beads)

- Ensure complete removal of unincorporated dyes

Issue: Discordant Results Between NGS and Sanger Sequencing

Symptoms: Variant detected by NGS but not confirmed by Sanger, or vice versa.

Solution Protocol:

Verify NGS Variant Quality Metrics

- Check variant allele frequency (VAF) in NGS data

- Review read alignment around variant position for artifacts

- Confirm strand bias metrics are within acceptable ranges

- Verify quality scores (Q≥20 for bases, QUAL≥100 for variants)

Investigate Technical Artifacts

- Check for homopolymer regions near variant that may cause alignment issues

- Verify amplicon design doesn't overlap problematic genomic regions

- Confirm primer binding sites don't contain polymorphisms

Experimental Verification

- Repeat Sanger sequencing with independent PCR amplification

- Design alternative primers targeting the same variant

- Consider bidirectional sequencing for confirmation

- Validate with alternative method (e.g., pyrosequencing, digital PCR) if available

Biological Explanation Assessment

- Evaluate potential sample mix-up or contamination

- Consider tumor heterogeneity affecting variant detection

- Assess clonal evolution between sample collection times

Issue: Primer Design Challenges for Difficult Genomic Regions

Symptoms: Repeated primer failure in GC-rich, repetitive, or complex genomic regions.

Solution Protocol:

Advanced Primer Design Strategies

- Incorporate locked nucleic acids (LNAs) for GC-rich regions

- Use touchdown PCR protocols with graduated annealing temperatures

- Design primers spanning exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification

- Consider long-range PCR with internal sequencing primers

Alternative Amplification Approaches

- Implement PCR additives:

- DMSO (1-10%)

- Betaine (0.5-2M)

- Formamide (1-5%)

- GC-rich specific buffers

- Optimize magnesium concentration (1.5-4.0 mM range)

- Test different polymerase enzymes with higher processivity

- Implement PCR additives:

Template Modification

- Use genome-wide amplification for limited template

- Implement nested PCR approaches for low-complexity regions

- Consider fragmentation and subcloning for extremely problematic regions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Sanger Validation Workflow

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Enzymes | High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Phusion, Q5) | PCR amplification with proofreading activity; reduces amplification errors |

| Sequencing Chemistry | BigDye Terminator v3.1 | Chain-termination sequencing with fluorescent ddNTPs; standard for capillary electrophoresis |

| Purification Methods | Ethanol precipitation, column purification, magnetic beads | Remove unincorporated dyes, salts, and primers before sequencing |

| Capillary Arrays | POP-7 polymer, 50cm arrays | Matrix for fragment separation by size in automated sequencers |

| Quality Control Tools | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, Qubit fluorometer | Assess DNA quality, quantity, and fragment size distribution |

| Primer Design Software | Primer3, OligoAnalyzer, NCBI Primer-BLAST | In silico primer design, validation, and specificity checking |

| Sequence Analysis Tools | Sequencing Analysis Software, 4Peaks, Geneious | Base calling, sequence alignment, and variant identification |

Workflow Integration Diagrams

Advanced Integration Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Validation for Large Variant Sets

For studies involving numerous variants, implement this efficient workflow:

Multiplex Primer Design

- Design primers with similar Tm (60±2°C)

- Incorporate unique tags for sample multiplexing

- Verify no cross-homology between multiplexed assays

96-Well Plate Setup

- Standardize reaction volumes and concentrations

- Implement robotic liquid handling for reproducibility

- Include controls in each plate (positive, negative, no-template)

Capillary Electrophoresis Optimization

- Utilize 96-capillary instruments for high throughput

- Implement rapid run protocols (1-2 hours)

- Use polymer formulations allowing rapid separation

Automated Data Analysis

- Implement batch processing of sequence files

- Use quality score thresholds for automatic pass/fail

- Generate consolidated reports for all validated variants

Protocol: Low-Frequency Variant Validation

For variants with VAF below Sanger's detection limit:

Enrichment Strategies

- Implement peptide nucleic acid (PNA) clamping

- Use co-amplification at lower denaturation temperature PCR (COLD-PCR)

- Consider digital PCR for absolute quantification

Sensitivity Enhancement

- Increase input DNA amount (up to 100ng)

- Optimize PCR cycles (30-35 cycles maximum)

- Implement nested PCR approaches

Alternative Validation Methods

- Pyrosequencing for quantitative results

- MassARRAY for multiplexed validation

- ddPCR for precise allele frequency determination

The Sanger-NGS Validation Paradigm: Is Orthogonal Confirmation Always Necessary?

The Evolving Standard of Care

A significant shift is occurring in molecular diagnostics regarding the need to validate next-generation sequencing (NGS) findings with Sanger sequencing. While traditionally considered the "gold standard," Sanger sequencing adds considerable time and cost to clinical reporting [47]. Emerging evidence from large-scale studies suggests that for high-quality NGS variants, orthogonal Sanger confirmation may have limited utility [20].

Quantitative Evidence from Large-Scale Studies

Recent studies involving thousands of variants demonstrate exceptionally high concordance between NGS and Sanger sequencing:

Table 1: Concordance Rates Between NGS and Sanger Sequencing in Major Studies

| Study Scope | Sample Size | Number of Variants | Concordance Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Exomes [47] | 825 exomes | 1,109 variants | 100% | All high-quality SNVs and indels were confirmed; Sanger useful for quality control but not essential for verification |

| ClinSeq Cohort [20] | 684 exomes | ~5,800 variants | 99.965% | Single-round Sanger sequencing more likely to incorrectly refute true positive NGS variants than identify false positives |

| Whole Genome Sequencing [21] | 1,150 WGS | 1,756 variants | 99.72% | Caller-agnostic thresholds (DP≥15, AF≥0.25) effectively identified variants needing validation |

Decision Framework for Sanger Validation

Laboratories can establish quality thresholds to determine when Sanger validation is necessary:

NGS Validation Protocol: Establishing Laboratory Confidence

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

For reliable NGS validation, follow this detailed experimental workflow:

DNA Isolation and Sample Enrichment

- Extract genomic DNA from appropriate sources (peripheral blood, saliva, or tissue) using standard extraction systems [5]

- Amplify coding regions and at least 20 bp of flanking intronic sequence using custom-designed primers

- Use PCR conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 10 cycles of step-down annealing, then 25 cycles with annealing at 55°C [5]

- Visualize PCR products on 2% agarose gel and purify using appropriate purification systems

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Pool enriched amplicons in equimolar amounts after quantitation in triplicate

- Perform end-repair and concatenation of pooled samples

- Shear concatenated sample to 150-180 bp fragments

- Ligate sequencing adaptors with unique barcodes for sample multiplexing

- Quantify final library and perform emulsion PCR for template amplification